Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2Cs (PP2Cs) are members of the serine/threonine phosphatase family that play pivotal roles in regulating plant development and responses to environmental stresses. However, comprehensive genome-wide studies of the PP2C gene family in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) have not yet been conducted. In the present study, 78 VvPP2C genes were identified and classified into 12 clades based on their phylogenetic relationships. Analysis of physicochemical properties and gene/protein architectures revealed that the members within each clade shared conserved structural features. Synteny analysis demonstrated that both tandem and segmental duplications substantially contributed to the expansion of the VvPP2C gene family. Tissue-specific transcriptional profiles and cis-element analyses indicated the potential involvement of these genes in grape development and stress responses. Moreover, expression analysis identified VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 as the most abscisic acid (ABA)-responsive genes, with expression patterns highly correlated with grape berry development. Functional validation in transgenic tomato lines demonstrated that the overexpression of either gene markedly delayed fruit ripening. Collectively, this study provides new insights into the evolutionary diversification and regulatory functions of the PP2C gene family in grape and identifies VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 as key candidates for elucidating ABA-mediated ripening mechanisms in non-climacteric fruits.

1. Introduction

Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) is a metal-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase belonging to the protein phosphatase M (PPM) family. It serves as a key regulator of diverse cellular processes, including environmental stress responses [1], hormonal signaling [2], and development [3]. PP2Cs possess a conserved catalytic core of approximately 300 amino acids containing 11 invariant motifs essential for phosphatase activity [1]. Although this catalytic domain is typically located at the C-terminus, certain isoforms exhibit N-terminal positioning [4]. Structural analyses have indicated that the flexible surface loops within the catalytic core mediate specific protein–protein interactions, conferring functional diversity among PP2C members [5]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the PP2C family comprises more than 80 members that are phylogenetically grouped into 12 clades (A–K) [6,7]. Notably, clade A PP2Cs (PP2CAs) function as central negative regulators of abscisic acid (ABA) signaling [6,8]. The core ABA signaling module is highly conserved: upon hormone binding, PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors undergo conformational changes that inhibit PP2CA activity [9,10]. This inhibition releases SnRK2 kinases from repression, allowing their phosphorylation and activation, often mediated by upstream Raf-like kinases [11]. Activated SnRK2s subsequently phosphorylate downstream targets, such as ABF transcription factors and SLAC1 ion channels, thereby initiating ABA-dependent physiological responses [12].

As one of the most widely cultivated fruit crops globally, grape (Vitis vinifera L.) holds high economic value and a long history of domestication [13,14]. However, maintaining an optimal balance between fruit quality, nutritional development, and reduced postharvest perishability remains a major challenge [15,16,17]. More than 30% of harvested fruits, including grapes, are lost annually due to postharvest spoilage [18]. Such losses not only cause economic waste but also exacerbate nutritional insecurity, particularly in regions where fruits are primary dietary sources of vitamins, antioxidants, and fiber [18,19]. Enhancing postharvest durability through molecular breeding (e.g., gene editing and epigenome engineering) has become a key strategy for developing cultivars that satisfy both agronomic and consumer demands under changing climatic conditions. Fruit ripening is controlled by a complex regulatory network that integrates hormonal signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, and epigenetic modification [20,21,22]. In climacteric fruits such as tomato [23] and apple [24], ethylene (ETH) is the principal regulator of ripening, whereas in non-climacteric fruits such as grape [25] and strawberry [26], ABA serves as the dominant hormonal signal. In climacteric fruits, ETH promotes autocatalytic biosynthesis through ACC synthase and ACC oxidase (ACS/ACO) and activates major transcription factors, including RIN (MADS-box), NOR (NAC), and ERFs [24,27]. Conversely, non-climacteric fruit ripening is largely governed by ABA, whereas the molecular mechanisms and signaling components underlying ABA-mediated regulation remain less well defined than those of ethylene. This knowledge gap limits the precise genetic manipulation of ripening grapes and restricts the development of varieties with improved storage potential and desirable sensory traits.

Extensive research has established PP2Cs as critical regulators of stress and immune signaling, fine-tuning adaptive responses through interactions with SnRK2 kinases, transcription factors, and ion channels [28]. For instance, in Triticum aestivum, TaPP2C158 dephosphorylates TaSnRK1.1, thereby suppressing the drought tolerance [29]. In Arabidopsis, the calcium sensor SCaBP8 inactivates PP2C.D6 and PP2C.D7 to activate the SOS1 Na+/H+ exchanger under salt stress [30]. Similarly, AP2C1 negatively regulates immune responses by suppressing ethylene biosynthesis and defense-related gene expression during pathogen attacks [31]. Recent studies have revealed the involvement of PP2Cs in fruit ripening, particularly in tomatoes. Silencing SlPP2C1 accelerates ripening, elevates ABA accumulation, and enhances ABA sensitivity, whereas it also results in defects in flower development [32]. Similarly, SlPP2C2 dephosphorylates the transcriptional repressor SlZAT5, stabilizing its inhibitory function on ripening-related genes and delaying ethylene-mediated ripening [33]. Another phosphatase, SlPP2C3, suppresses ripening by interacting with ABA receptors and SlSnRK2.8, whereas its downregulation promotes earlier ripening and increases fruit glossiness through altered cuticular metabolism [34]. Despite these advances in tomato, the functions and regulatory mechanisms of PP2Cs in grape berry ripening remain largely unknown.

Given the pivotal role of ABA in non-climacteric fruit ripening and the established involvement of PP2Cs in ABA-mediated signaling, PP2C proteins are key modulators of grape berry ripening. Although the PP2C gene families have been comprehensively characterized in several species, including A. thaliana [30], cucumber (Cucumis sativus) [35], strawberries (Fragaria vesca and Fragaria ananassa) [36], peanut (Arachis hypogaea) [37], wheat (Triticum aestivum) [38], and soybean (Glycine max) [39], a systematic genome-wide analysis in grape remains unavailable. In this study, we identified 78 VvPP2C genes from the grapevine genome and systematically analyzed their physicochemical properties, gene structures, chromosomal distributions, evolutionary relationships, and expression profiles across multiple tissues. Furthermore, we investigated the expression dynamics of VvPP2CAs during berry development and under exogenous ABA treatment. Functional characterization of transgenic tomato lines further elucidated the roles of VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 in regulating fruit ripening. These findings provide new insights into the molecular functions of VvPP2Cs and facilitate future molecular breeding efforts aimed at improving fruit quality and postharvest performance.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of VvPP2Cs

To identify PP2C genes in the grapevine genome (PN_T2T), a BLASTP search was performed using Arabidopsis PP2C protein sequences as queries. The initial screening yielded 634 candidate proteins. Subsequent validation using the NCBI-CDD database confirmed the presence of complete PP2C domains in 78 proteins, which were designated VvPP2C1 to VvPP2C78 according to their chromosomal positions and linear order (Figure S1). Analysis of physicochemical properties revealed substantial variation among the encoded proteins: protein lengths ranged from 92 (VvPP2C31) to 1083 (VvPP2C49) amino acids; molecular weights (MW) varied from 9.77 kDa (VvPP2C31) to 120.06 kDa (VvPP2C49); and predicted isoelectric points (pI) ranged from 4.31 (VvPP2C54) to 9.40 (VvPP2C32). All VvPP2C proteins were predicted to localize to intracellular compartments, primarily the nucleus, chloroplasts, cytoplasm, and plasma membrane, although several were also predicted to reside in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of VvPP2Cs.

2.2. Phylogenetic Classification and Syntenic Relationships of VvPP2Cs

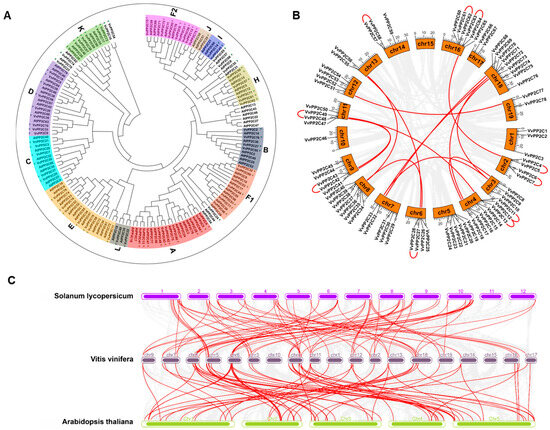

The evolutionary relationships among the 78 VvPP2C proteins were analyzed using a Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree approach (Figure 1A). Following the classification scheme established for Arabidopsis, in which the PP2C genes were grouped into 13 clades [30], the VvPP2C genes were assigned to 12 clades, as no homologs corresponding to Arabidopsis clade G were identified in the grapevine genome. Eight VvPP2Cs (VvPP2C10/23/24/35/54/65/66/74) could not be assigned to any known clade. Clade A contained the largest number of members (11), whereas clade I contained only one. The VvPP2C genes were unevenly distributed across the 18 chromosomes (Figure 1B). Chromosome 18 harbored the greatest number (9), whereas chromosome 15 lacked VvPP2C genes entirely. The expansion of the VvPP2C family was further investigated by examining gene duplication events. Among all VvPP2C genes, 19 (24.35%) underwent 10 tandem duplication events, and 28 (35.89%) formed 14 segmental duplication pairs (Figure 1B; Table S1). These results indicated that both tandem and segmental duplications contributed substantially to the expansion of the VvPP2C family. Synteny analysis revealed 71 and 81 orthologous gene pairs between V. vinifera and A. thaliana and between V. vinifera and S. lycopersicum, respectively, implying that grapevine shares a closer evolutionary relationship with tomato than with Arabidopsis (Figure 1C; Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny and genomic duplications of PP2Cs. (A) Phylogenetic relationships between PP2C proteins from Vitis vinifera and Arabidopsis, illustrated as a phylogenetic tree. Grape proteins are represented by purple circles, and Arabidopsis proteins by green triangles. (B) Chromosomal distribution and duplication events of VvPP2Cs. Red lines indicate genes derived from segmental or tandem duplications. (C) Synteny analysis of VvPP2Cs compared with PP2Cs in Arabidopsis and Solanum lycopersicum. Orthologous gene pairs are connected by red lines.

2.3. Analysis of Protein/Gene Structures of VvPP2Cs

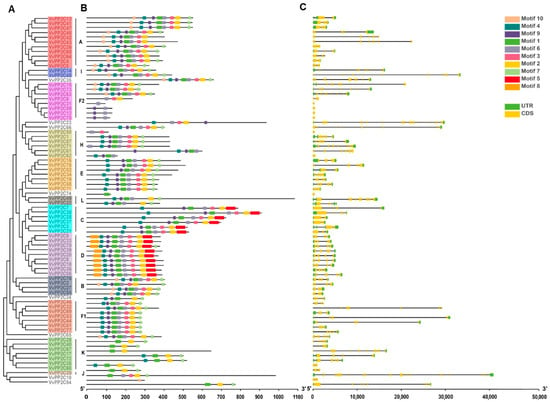

To evaluate the structural variation and evolutionary relationships among VvPP2C genes, motif analysis was performed using MEME, and the gene structures were examined using GSDS 2.0. An unrooted phylogenetic tree constructed from protein sequences supported the clade classification previously established (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). Ten conserved motifs, ranging from 15 to 49 amino acids in length, were identified (Figure 2B and Figure S2). The members within each clade exhibited largely consistent motif compositions and arrangements. Motif 2 was universally present across all clades, whereas Motifs 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9 were broadly distributed across clades A–I. In contrast, Motif 5 was specific to clades C and D, and Motif 8 was unique to clade D.

Figure 2.

Phylogeny, conserved motifs, and exon-intron organization of VvPP2Cs. (A) Evolutionary relationships among VvPP2C proteins, as depicted in a phylogenetic tree. (B) Conserved motifs identified in the VvPP2C family. Ten distinct motifs are shown as colored boxes, with blue, red, and green representing motifs 1–10. (C) Exon-intron structures of VvPP2C genes. CDSs are represented by yellow boxes, UTRs by green boxes, and introns by black lines connecting them.

The exon–intron architectures of the 78 VvPP2C genes were also analyzed, revealing exon counts ranging from 1 to 26. VvPP2C26 contained the highest number of exons (26), whereas VvPP2C12/31/50/59/62/74/75 contained only one. Most members of clades B to E possessed both 5′- and 3′-UTRs, whereas these regions were detected in only a few genes belonging to clades A, F1, F2, H, I, J, and K (Figure 2C). Such variations in gene architecture suggest potential functional divergence among VvPP2C members.

2.4. Analysis of Promoters of VvPP2Cs

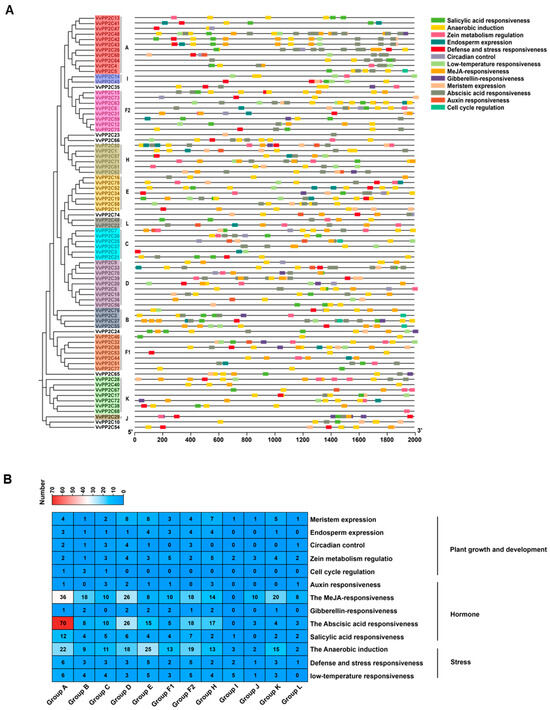

To explore the transcriptional regulation and potential biological roles of VvPP2C genes, the promoter regions were analyzed using PlantCARE. Five categories of cis-acting elements were identified, including five hormone-responsive elements, five stress-related elements, and three development-associated elements. Among these, ABA-responsive elements were the most prevalent (Figure 3A). The composition and abundance of cis-elements varied markedly among clades. Clade D harbored the highest number of development-related elements, Clade E was enriched in the stress-responsive elements, and Clade A contained the greatest proportion of hormone-responsive elements (Figure 3B). These differences in cis-element distribution exhibited functional diversification among VvPP2C clades, enabling them to mediate responses to hormonal, environmental, and developmental cues.

Figure 3.

Composition and distribution of promoter cis-elements in VvPP2Cs. (A) Chromosomal locations of different cis-elements in VvPP2C promoters. Different colors indicate distinct types of cis-elements. (B) Heatmap showing the abundance of each cis-element type across promoters. The red and blue squares represent higher and lower counts, respectively.

2.5. Tissue-Specific Expression Profiles of VvPP2Cs

To further elucidate the potential functions of VvPP2C genes, their expression patterns were examined across 21 grapevine organs and tissues at various developmental stages using data from the BAR database (Figure 4). Overall, the VvPP2C genes were constitutively expressed in nearly all examined tissues, although their expression levels varied substantially among tissues and developmental stages. These genes were grouped into five distinct expression clusters (Groups I–V). The genes in Groups I and II showed the highest expression across all tissues, whereas those in Groups III and IV exhibited consistently low transcript levels. The expression of Group IV genes was particularly elevated in the roots and fruits relative to that in other tissues. Further analysis revealed divergent expression profiles among VvPP2C clades and even among members within the same clade. For instance, in Group A involving 11 genes (VvPP2C4/5/13/26/41/42/43/47/48/60/64), VvPP2C13/26/41 exhibited markedly higher expression across multiple tissues than other members.

Figure 4.

Tissue-specific expression profiles of VvPP2Cs. The heatmap was generated based on an in silico analysis of tissue-specific expression data retrieved from the BAR database. Expression values were log2-transformed and normalized, followed by hierarchical clustering. Differences in expression levels are indicated by a color gradient ranging from blue (low expression) to red (high expression).

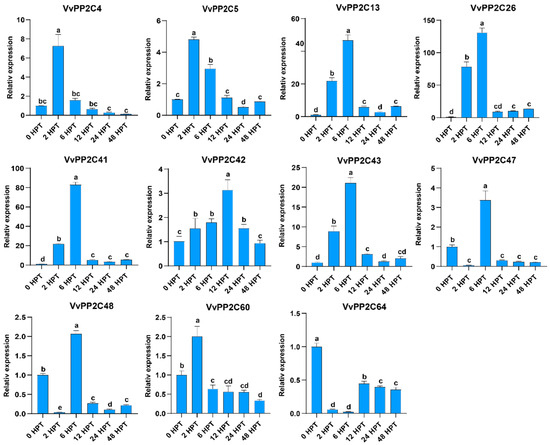

2.6. Expression Changes in Vvpp2cas in Grape Berries in Response to Exogenous ABA

In model plants, clade A PP2Cs are recognized as key regulators of the ABA signaling pathway [40]. To investigate the responsiveness of grape VvPP2CAs to exogenous ABA, the expression patterns were analyzed following ABA treatment (Figure 5). Grape berries at the E–L 39 stage were treated with exogenous ABA and maintained at 23 °C. The expression levels of VvPP2CAs were examined at six subsequent time points. Most VvPP2CAs were transiently upregulated by ABA, with expression peaking at either 2 or 6 h post-treatment (HPT), followed by a gradual decline. This rapid induction-repression trend was particularly evident for VvPP2C4/5/13/26/41/42/43/60. In particular, VvPP2C13/26/41 exhibited a sharp expression decrease after 6 HPT. In contrast, VvPP2C47/48 also exhibited transient induction at 6 HPT but lacked consistent expression dynamics. In contrast, VvPP2C64 exhibited a steady decrease in expression throughout the treatment period, without a distinct peak. Notably, VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 displayed the most prominent transcriptional alterations in response to ABA, highlighting their potential roles as pivotal regulators within the ABA-mediated signaling network.

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of VvPP2CAs in response to exogenous ABA treatment. Error bars represent SD (n = 3). Significant differences at p < 0.05, as assessed using Duncan’s multiple range test, are denoted by different lowercase letters.

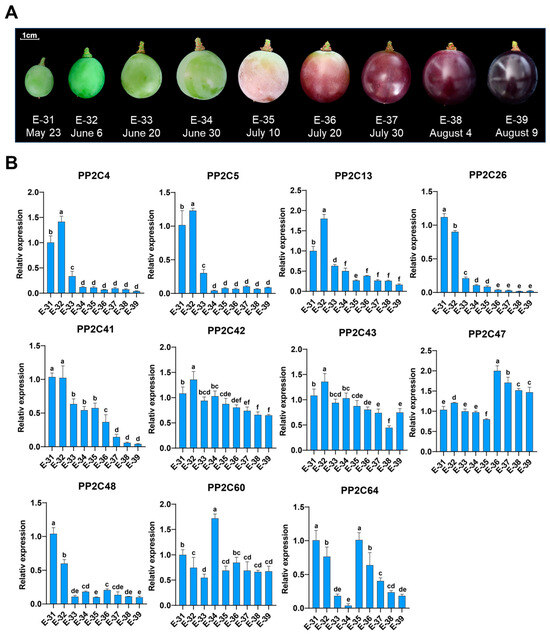

2.7. Expression Profiles of VvPP2CAs During Grape Berry Development

Given the enrichment of hormone- and development-related cis-elements in VvPP2CA promoters and their sensitivity to exogenous ABA, we further examined the expression profiles of these genes during grape berry development, with total soluble solids (TSS) serving as a physiological indicator of maturation (Figure 6A and Figure S3A). Transcript levels of most VvPP2CAs changed dynamically across development stages. VvPP2C4/5/13/26/41/48 were significantly downregulated, while VvPP2C47 was upregulated. In contrast, VvPP2C42/43/60/64 exhibited fluctuating expression without a clear trend. Notably, the downregulation of VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 was the most pronounced (Figure 6B). Pearson correlation analysis further revealed their expression levels were significantly and inversely correlated with TSS (for VvPP2C26, r = −0.879, p < 0.01; for VvPP2C41, r = −0.965, p < 0.01) (Figure S3B), underscoring a close association between these genes and the progression of grape berry ripening.

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of VvPP2CAs during grape berry development. (A) Phenotypes of ‘Kyoho’ berries at different developmental stages. Sample names and collection dates are indicated below. Scale bar = 1 cm; (B) Expression patterns of VvPP2CAs during grape berry development. Error bars represent SD (n = 3). Significant differences at p < 0.05, as assessed using Duncan’s multiple range test, are denoted by different lowercase letters.

2.8. VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 Acts as a Negative Regulator of Fruit Ripening

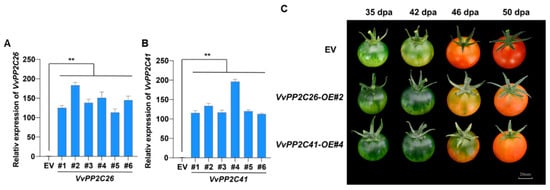

Given the pronounced ABA responsiveness and developmental expression changes in VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41, these genes were hypothesized to function as negative regulators of fruit ripening. To validate their roles, overexpression (OE) lines of VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 were generated in tomato via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, along with empty vector (EV) controls. qPCR verification confirmed the successful overexpression of target genes in six independent transgenic lines for each construct (Figure 7A). The lines VvPP2C26-OE#2 and VvPP2C41-OE#4 exhibiting the highest expression levels were selected for phenotypic assessment. Both VvPP2C26-OE#2 and VvPP2C41-OE#4 fruits displayed a marked delay in ripening compared with EV controls (Figure 7B). These results demonstrate that VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 function as negative regulators of fruit ripening, likely by modulating ABA-mediated signaling pathways.

Figure 7.

Overexpression of VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 delays fruit ripening in tomato. (A,B) Relative expression levels of VvPP2C26 (A) and VvPP2C41 (B) in transgenic OE lines and EV controls. Error bars represent SD (n = 3). Asterisks denote significant differences (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). (C) Representative phenotypes of EV control and transgenic tomato fruits at different developmental stages. DPA, days post-anthesis. Scale bar = 20 mm.

3. Discussion

The PP2C family of protein phosphatases plays a central role in coordinating plant developmental processes and adaptive responses to environmental stresses [8,41]. Although the genome-wide analyses of the PP2C gene family have been performed in several plant species, including A. thaliana [30], cucumber (C. sativus) [35], Strawberries (F. vesca and F. ananassa) [36], peanut (A. hypogaea) [37], Wheat (T. aestivum) [38], and soybean (G. max) [39], a comprehensive investigation in grapevine had not been conducted prior to the present study. A total of 78 VvPP2C genes were identified through a genome-wide screening and systematically analyzed for their physicochemical characteristics, gene structures, chromosomal distributions, and expression dynamics during fruit development and in response to ABA treatment. In particular, VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 were examined in depth to elucidate their potential functions in grape berry development and ripening. These results establish a foundation for future functional characterization of the VvPP2C gene family in grape.

The PP2C family exhibits considerable evolutionary diversity and a long history of adaptation in land plants, with its functional divergence likely reflecting environmental adaptability [42]. In this study, 78 VvPP2C genes were identified and classified into 12 clades based on phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment (Figure S1; Table S1). Comparative genomic investigation revealed that the VvPP2C family in grapes was smaller than those in A. thaliana [28], A. hypogaea [37], and T. aestivum (Table S4). This difference may reflect the influence of genome size and pseudogenization events during evolution. Grapevine with a genome size of approximately 500 Mbp contained fewer PP2C genes than A. thaliana (~135 Mbp) (Table S4), likely due to the higher proportion of noncoding DNA in eukaryotic genomes [43]. Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed the classification of VvPP2Cs into 12 clades corresponding to the 13 clades defined in Arabidopsis, with no homologs identified for clade G and eight unclassified VvPP2Cs (Figure 1A). These observations highlight the influence of species-specific evolution on PP2C gene architecture [44]. Clade A of VvPP2Cs displayed greater heterogeneity than clade I (Figure 1A,B), suggesting an earlier evolutionary origin and longer time span for gene duplication and structural diversification [45]. Both tandem and segmental duplication events were major drivers of VvPP2C family expansion, accounting for 24.35% and 35.89% of the genes, respectively (Figure 1B; Tables S1 and S2). These duplication events likely contributed to the adaptive evolution of grapevine PP2Cs. Moreover, synteny analysis demonstrated more orthologous gene pairs between grapevine and tomato than between grape and Arabidopsis (Figure 1C; Table S3), implying a closer evolutionary relationship between these two fruit crops [46]. This highlights the value of our study in providing a direct comparator for deciphering gene family evolution in fleshy fruits, as opposed to the more distant reference of Arabidopsis.

Structural analyses revealed that the conserved motifs of VvPP2Cs could provide valuable insights into their evolutionary conservation and functional specialization [47]. The composition and exon-intron structures of VvPP2Cs were largely conserved within clades but diverged across them (Figure 2 and Figure S2). Motif 2 was universally present, whereas Motifs 5 and 8 were specific to clades C and D, respectively. The members of clades B to E typically contained both 5′- and 3′-UTRs, which were less common in other clades. Given that proteins with similar structures in Arabidopsis often exhibit analogous regulatory functions [48], these conserved structural characteristics suggest that VvPP2C members within the same clade may possess comparable biological roles. Promoter cis-element analysis revealed a clade-specific distribution of hormonal, stress-responsive, and development-associated elements (Figure 3). Strikingly, the promoter landscape of grapevine VvPP2CAs showed a distinct enrichment profile compared to their well-characterized Arabidopsis counterparts. While both are rich in ABA-responsive elements, the grapevine promoters harbored a more diverse array of elements linked to light, circadian control, and fruit development, suggesting their regulation may be integrated with a broader set of environmental and developmental cues specific to a perennial vine undergoing seasonal growth and fruit production. Tissue-specific expression profiling can provide essential predictions for the functional differentiation of gene families [49]. Expression analysis revealed that VvPP2Cs were constitutively expressed in nearly all examined tissues, whereas their transcript levels varied considerably, forming five distinct expression clusters (Figure 4). Such ubiquitous yet differential expression implies that VvPP2Cs play diverse but fundamental roles in grape growth and development. Notably, even within a single clade, such as clade A, certain members (VvPP2C13/26/41) exhibited markedly higher expression levels, suggesting functional divergence following gene duplication events.

The roles of PP2C genes in regulating stress and hormonal signaling have been well established in model plants [50,51,52]. PP2Cs modulate the ABA signaling and physiological adaptation by interacting with key proteins such as SnRK2s, ABA receptors, transcription factors, and ion channels [53,54,55]. Recent studies have highlighted their participation in fruit development [32,33,34], where climacteric and non-climacteric fruits are governed by distinct hormonal regulators, including ETH and ABA. In Arabidopsis, clade A PP2Cs function as central negative regulators of ABA signaling [56]. In the absence of ABA, PP2CAs (e.g., ABI1, ABI2, and HAB1) dephosphorylate key serine residues within the activation loops of SnRK2 kinases, thereby suppressing their activities [8]. Upon ABA binding, PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors interact with and inhibit PP2CAs, consequently releasing SnRK2s to transduce ABA signals [57]. Li et al. identified an “ABA–FaPYR1–FaPP2C–FaSnRK2” signaling module as a core regulatory mechanism controlling strawberry ripening and proposed a model for ABA-mediated regulation of non-climacteric fruit ripening [58]. Guided by these findings, we analyzed the expression patterns of clade VvPP2CAs during grape berry development and under exogenous ABA treatment (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure S3). VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 exhibited the most prominent upregulation in response to ABA, and their expression levels were strongly positively correlated with fruit ripening progression. To further validate their functional roles, transgenic tomato lines overexpressing VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 were generated. Both the VvPP2C26-OE and VvPP2C41-OE lines displayed a significant delay in fruit ripening (Figure 7), indicating that these genes act as negative regulators of fruit ripening through ABA-mediated signaling pathways.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Six-year-old ‘Kyoho’ grapevines were cultivated in the open-field experimental vineyard of the Shandong Academy of Grape in Tai’an, China (34.41° N, 112.46° E). Grape berries were collected at key developmental stages according to the E-L system [59], including young fruit (E-31, May 23), green fruit (E-32, June 6; E-33, June 20; E-34, June 30), veraison (E-35, July 10; E-36, July 20), and mature stages (E-37, July 30; E-38, August 4; E-39, August 9). Samples were obtained from three independent vines at each stage. Two bunches of uniform, disease-free grape berries of consistent size were harvested from the middle portion of each vine. Grape berries of uniform size were harvested from the middle portion of each cluster and pooled. At the E-39 stage, fruits exhibiting consistent growth and free from mechanical injury, pest infestation, or disease symptoms were selected from three independent vines. The grape berries were immersed in a 1 mM ABA solution for 15 min and subsequently incubated in a controlled environment at 23 °C under constant humidity. Samples were collected at 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 HPT, with three biological replicates per time point, using the 0 HPT samples as controls. Immediately after sampling, the berry flesh (pulp) was separated from the seeds and skin, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until subsequent analyses.

4.2. Identification of VvPP2Cs

The protein sequences of Arabidopsis PP2Cs were retrieved from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/browse/gene_family, accessed on 17 March 2025) [60] and used as reference queries to search the Vitis vinifera PN_T2T genome [61] within the Winberige database (http://www.winberige.cc/ftp.html, accessed on 17 March 2025) using BLASTP v2.12.0+. Sequences with significant similarity (E-value < 1 × 10−10) were retained for further evaluation [62]. The presence of conserved PP2C domains was confirmed using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi, accessed on 17 March 2025). The predicted VvPP2C proteins were analyzed for biochemical parameters, including MW and pI, using ExPASy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 18 March 2025). Subcellular localization was predicted using WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 18 March 2025) [63].

4.3. Phylogenetic and Synteny Analyses

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW implemented in MEGA version 12. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the NJ method with 1000 bootstrap replicates [64]. Gene duplication patterns within the VvPP2C family were analyzed using MCScanX [65]. Chromosomal locations were retrieved from the Winberige database, and collinearity and duplication relationships were visualized using TBtools v2.0 software [66].

4.4. Analysis of Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs

The exon–intron structures of VvPP2C genes were determined and visualized using GSDS (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/, accessed on 10 April 2025) [67]. Conserved motifs were identified using the MEME suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme, accessed on 10 April 2025) [68]. Integrating motif composition and gene structure information, a comprehensive visualization was generated using TBtools v2.0 [66].

4.5. Promoter Analysis

Promoter sequences extending 2000 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon for each VvPP2C gene were extracted using TBtools v2.0. Putative cis-acting regulatory elements were identified using the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 18 April 2025) [69]. The detected elements were classified according to their function, and their distributions were visualized using TBtools v2.0 [66].

4.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Profile Analysis

The expression profiles of VvPP2C genes across 21 grapevine tissues were obtained from the BAR database (https://bar.utoronto.ca/efp_grape/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi, accessed on 10 May 2025), which provides genome-wide expression data for major grape organs and tissues, including roots, stems, leaves, buds, flowers, fruits, seedlings, and pollen [70]. The Vitis vinifera v2.1 genome was used here [71]. The expression levels (FPKM values) were quality checked and log2-transformed for normalization. Heatmaps were generated using TBtools v2.0 to visualize the expression patterns of VvPP2C genes across tissues.

4.7. qRT-PCR Validation

The primers used for qRT-PCR were designed using SnapGene v1.1.3 software (Table S5). Total RNA was extracted from the frozen powder of grape berry flesh using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions, which included steps for cell lysis, homogenate processing, and purification. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR amplification was performed using a LightCycler 480 System (Roche Diagnostics, Shanghai, China; headquartered in Basel, Switzerland) and TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara). VvUBI was used as an internal reference [69]. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [72].

4.8. Vector Construction and Plant Transformation

The CDS of VvPP2C26 (Vitvi009987) and VvPP2C41 (Vitvi015923) was amplified from cDNA synthesized from ‘Kyoho’ grapevine leaves and validated by sequencing. The verified CDS fragments were ligated into the plant expression vector pBWA(V)HS using the ABclonal MultiF Seamless Assembly Mix (ABclonal Technology, Wuhan, China). The EV and recombinant constructs pBWA(V)HS–VvPP2C26 and pBWA(V)HS–VvPP2C41 were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 using the freeze–thaw transformation method. Tomato (S. lycopersicum cv. Ailsa Craig) plants were subsequently generated through A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation with 35S::VvPP2C26 and 35S::VvPP2C41 constructs [73]. The corresponding primer sequences are presented in Table S5.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a total of 78 PP2C genes were identified and classified into 12 distinct clades in grapevine. Gene duplication events, including both segmental and tandem types, played a major role in the expansion of the VvPP2C gene family. Analyses of cis-regulatory elements and tissue-specific expression patterns suggested the potential involvement of VvPP2Cs in grape berries growth and stress adaptation. Clade A members (VvPP2CAs) exhibited marked differential expression during fruit development and in response to ABA treatment. Functional characterization further demonstrated that the overexpression of VvPP2C26 and VvPP2C41 in tomato significantly delayed fruit ripening. Collectively, these findings provide new insights into the biological functions of PP2C genes in grape and underscore their potential application in the genetic modulation of fruit ripening traits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14243827/s1, Figure S1: Conserved domains analysis of VvPP2Cs; Figure S2: Sequence logos of 10 conserved motifs detected in the VvPP2C proteins; Figure S3: Correlation analysis between VvPP2CA gene expression and total soluble solids content in grape berry development; Table S1: The duplication pairs of VvPP2C genes in grapevine; Table S2: The duplication pairs of VvPP2C genes in grape and Arabidopsis thaliana; Table S3: The duplication pairs of VvPP2C genes in grape and tomato; Table S4: The numbers and genome size of PP2C homologous genes found in indicated species; Table S5: Sequence of primers used for expression analysis, F for the former primer, R for the rear primer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., K.L. (Kaidi Li) and K.L. (Kai Liu); methodology, K.L. (Kaidi Li) and K.L. (Kai Liu); validation, K.L. (Kai Liu) and K.W.; formal analysis, K.L. (Kaidi Li), Y.P. and X.Z.; investigation, K.L. (Kaidi Li) and K.L. (Kai Liu); resources, K.L. (Kai Liu) and X.L.; data curation, K.L. (Kaidi Li) and K.L. (Kai Liu); writing—original draft preparation, K.L. (Kaidi Li); writing—review and editing, K.L. (Kai Liu) and B.L.; visualization, K.L. (Kaidi Li) and K.L. (Kai Liu); supervision, X.L. and B.L.; project administration, B.L.; funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2024QC095), Science and Technology Innovation Program of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. CXGC2025C15), and China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-29-16).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Caixia Zhang (Research Institute of Pomology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Xingcheng) for providing the Tomato (S. lycopersicum cv. Ailsa Craig) seeds.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schweighofer, A.; Hirt, H.; Meskiene, I. Plant PP2C phosphatases: Emerging functions in stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskara, G.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Verslues, P.E. Unique drought resistance functions of the highly ABA-induced clade A protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskara, G.B.; Wong, M.M.; Verslues, P.E. The flip side of phospho-signalling: Regulation of protein dephosphorylation and the protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 2913–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcher, K.; Ng, L.M.; Zhou, X.E.; Soon, F.F.; Xu, Y.; Suino-Powell, K.M.; Park, S.Y.; Weiner, J.J.; Fujii, H.; Chinnusamy, V.; et al. A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signalling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 2009, 462, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon, F.F.; Ng, L.M.; Zhou, X.E.; West, G.M.; Kovach, A.; Tan, M.H.; Suino-Powell, K.M.; He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chalmers, M.J.; et al. Molecular mimicry regulates ABA signaling by SnRK2 kinases and PP2C phosphatases. Science 2012, 335, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, N.; Zhang, F.; Yu, R.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.W.; Wei, N. SAUR17 and SAUR50 Differentially Regulate PP2C-D1 during Apical Hook Development and Cotyledon Opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3792–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.L. Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) function in higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 38, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, H.; Qamer, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A. The multifaceted roles of PP2C phosphatases in plant growth, signaling, and responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Liu, M.; Yan, Y.; Guo, X.; Cao, X.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, H.; et al. The U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase PUB35 negatively regulates ABA signaling through AFP1-mediated degradation of ABI5. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3277–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Mao, J.; Tan, S.; Xiang, C. The ABI3-ERF1 module mediates ABA-auxin crosstalk to regulate lateral root emergence. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Liu, X.D.; Waseem, M.; Guang-Qian, Y.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Jahan, M.S.; Fang, X.W. ABA activated SnRK2 kinases: An emerging role in plant growth and physiology. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2071024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrich, R.; Geiger, D. Biology of SLAC1-type anion channels-from nutrient uptake to stomatal closure. New Phytol. 2017, 216, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Zheng, W.; Yin, H.; Mei, J.; Liu, X.; Abe-Kanoh, N.; Rhaman, M.S.; Qin, G.; Ye, W. Layered stomatal immunity contributes to resistance of Vitis riparia against downy mildew Plasmopara viticola. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 7, eraf491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Ayhan, D.H.; Rhaman, M.S.; Yan, M.; Jiang, J.; Wang, D.; Zheng, W.; Mei, J.; Ji, W.; et al. Super pangenome of Vitis empowers identification of downy mildew resistance genes for grapevine improvement. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, D.; Wang, B.; Khan, I.; Ni, Y. Ethylene Control Technologies in Extending Postharvest Shelf Life of Climacteric Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7308–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Liu, C.; Wei, Y.; Cha, G.; Shi, X.; Ren, X.; Ding, Y. The transcription factors AdNAC3 and AdMYB19 regulate kiwifruit ripening through brassinosteroid and ethylene signaling networks. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cassan-Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Bouzayen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, P. Calcium-dependent protein kinase PpCDPK29-mediated Ca2+-ROS signal and PpHSFA2a phosphorylation regulate postharvest chilling tolerance of peach fruit. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1938–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Mohanty, A.K.; DeEll, J.R.; Carter, K.; Lenz, R.; Misra, M. Advances in antimicrobial techniques to reduce postharvest loss of fresh fruit by microbial reduction. npj Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Zhang, J.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Han, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gao, A.; Wang, Y.; et al. Preserving fruit freshness with amyloid-like protein coatings. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Fu, Z.; Cui, X.; Yao, J.; Shi, Y.; Deng, W.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y. Tomato ripening regulator SlSAD8 disturbs nuclear gene transcription and chloroplast-associated protein degradation. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 2230–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, K.; Lai, Y.; et al. Light regulates tomato fruit metabolome via SlDML2-mediated global DNA demethylation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Yang, Y.Y.; Wu, C.J.; Kuang, J.F.; Chen, J.Y.; Lu, W.J.; Shan, W. MaMADS1-MaNAC083 transcriptional regulatory cascade regulates ethylene biosynthesis during banana fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.; Cao, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. The 14-3-3 Protein SlTFT1 Accelerates Tomato Fruit Ripening by Binding and Stabilising YFT1 in the Ethylene Signalling Pathway. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4872–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Yue, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, L.; Guan, Q.; You, C.; An, J.; et al. Autosuppression of MdNAC18.1 endowed by a 61-bp promoter fragment duplication delays maturity date in apple. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Zhang, H.X.; Tang, X.S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.H.; Li, B.; Xie, Z.S. Abscisic Acid Induces DNA Methylation Alteration in Genes Related to Berry Ripening and Stress Response in Grape (Vitis vinifera L). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15027–15039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.J.; Shi, Y.N.; Xiao, Y.N.; Jia, H.R.; Yang, X.F.; Dai, Z.R.; Sun, Y.F.; Shou, J.H.; Jiang, G.H.; Grierson, D.; et al. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 mediates repression of strawberry receptacle ripening via auxin-ABA interplay. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 2638–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Jin, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yin, S.; Zhao, J.; Lin, S.; et al. Comparative genomic analyses reveal different genetic basis of two types of fruit in Maloideae. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S.R.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Finkelstein, R.R.; Abrams, S.R. Abscisic acid: Emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Gao, L.; Hu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Reynolds, M.P.; Zhang, X.; Jia, J.; Mao, X.; et al. DIW1 encoding a clade I PP2C phosphatase negatively regulates drought tolerance by de-phosphorylating TaSnRK1.1 in wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1918–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Y. SALT OVERLY SENSITIVE 1 is inhibited by clade D Protein phosphatase 2C D6 and D7 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, J.; Huang, K.; Guo, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Tsuda, K.; et al. Suppression of ETI by PTI priming to balance plant growth and defense through an MPK3/MPK6-WRKYs-PP2Cs module. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, L.; Kai, W.; Liang, B.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Zhai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Suppressing Type 2C Protein Phosphatases Alters Fruit Ripening and the Stress Response in Tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yin, Z.; Pan, Y.; Mao, W.; Peng, L.; Guo, X.; Li, B.; Leng, P. SlPP2C2 interacts with FZY/SAUR and regulates tomato development via signaling crosstalk of ABA and auxin. Plant J. 2024, 119, 1073–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Leng, P. Tomato protein phosphatase 2C influences the onset of fruit ripening and fruit glossiness. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2403–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, S.; Li, X.; Lyu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wan, Z.; Yu, J. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the cucumber PP2C gene family. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lu, S.; Liu, T.; Nai, G.; Ren, J.; Gou, H.; Chen, B.; Mao, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Abiotic Stress Response Analysis of PP2C Gene Family in Woodland and Pineapple Strawberries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Luo, L.; Wan, Y.; Liu, F. Genome-wide characterization of the PP2C gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and the identification of candidate genes involved in salinity-stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1093913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Han, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; He, G. Wheat PP2C-a10 regulates seed germination and drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ali, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Xie, L. Identification, Evolutionary and Expression Analysis of PYL-PP2C-SnRK2s Gene Families in Soybean. Plants 2020, 9, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Szostkiewicz, I.; Korte, A.; Moes, D.; Yang, Y.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 2009, 324, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.J.; Chen, K.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Y. Osmotic signaling releases PP2C-mediated inhibition of Arabidopsis SnRK2s via the receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1. Embo J. 2024, 43, 6076–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, R.; Kudoh, F.; Ito, S.; Tani, I.; Janairo, J.I.B.; Omichinski, J.G.; Sakaguchi, K. Metal-dependent Ser/Thr protein phosphatase PPM family: Evolution, structures, diseases and inhibitors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 215, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faure, G.; Saito, M.; Wilkinson, M.E.; Quinones-Olvera, N.; Xu, P.; Flam-Shepherd, D.; Kim, S.; Reddy, N.; Zhu, S.; Evgeniou, L.; et al. TIGR-Tas: A family of modular RNA-guided DNA-targeting systems in prokaryotes and their viruses. Science 2025, 388, eadv9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Ying, T.; Zou, C.; Zhao, J. Genome-wide systematic characterization of PHT gene family and its member involved in phosphate uptake in Orychophragmus violaceus. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Sharma, P.; Mishra, D.; Dey, S.; Malviya, R.; Gayen, D. Genome-wide identification of the fibrillin gene family in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and its response to drought stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, P.; Miao, W.; Xiong, J. Genome-Wide Identification of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Ciliated Eukaryotes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, B.; Qi, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, C.; Meng, X. Genome-wide Identification and Expression Analysis of RcMYB Genes in Rhodiola crenulata. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 831611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinke, D.W. Genome-wide identification of EMBRYO-DEFECTIVE (EMB) genes required for growth and development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Saha, B.; Jaiswal, S.; Angadi, U.B.; Rai, A.; Iquebal, M.A. Genome-wide identification and characterization of tissue-specific non-coding RNAs in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1079221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B.; Munemasa, S.; Wang, C.; Nguyen, D.; Yong, T.; Yang, P.G.; Poretsky, E.; Belknap, T.F.; Waadt, R.; Alemán, F.; et al. Calcium specificity signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis guard cells. Elife 2015, 4, e03599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, D.; Wang, C.; He, J.; Liao, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gong, Z. A plasma membrane receptor kinase, GHR1, mediates abscisic acid-and hydrogen peroxide-regulated stomatal movement in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Mei, J.; Zheng, W.; Guo, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Ye, W.; et al. Grapevine phyllosphere pan-metagenomics reveals pan-microbiome structure, diversity, and functional roles in downy mildew resistance. Microbiome 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jossier, M.; Bouly, J.P.; Meimoun, P.; Arjmand, A.; Lessard, P.; Hawley, S.; Grahame Hardie, D.; Thomas, M. SnRK1 (SNF1-related kinase 1) has a central role in sugar and ABA signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2009, 59, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Qi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. The clade F PP2C phosphatase ZmPP84 negatively regulates drought tolerance by repressing stomatal closure in maize. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1728–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longkumer, T.; Chen, C.Y.; Biancucci, M.; Bhaskara, G.B.; Verslues, P.E. Spatial differences in stoichiometry of EGR phosphatase and Microtubule-associated Stress Protein 1 control root meristem activity during drought stress. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. Pepper SnRK2.6-activated MEKK protein CaMEKK23 is directly and indirectly modulated by clade A PP2Cs in response to drought stress. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Xie, S.; et al. Initiation and amplification of SnRK2 activation in abscisic acid signaling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mou, W.; Xia, R.; Li, L.; Zawora, C.; Ying, T.; Mao, L.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Z. Integrated analysis of high-throughput sequencing data shows abscisic acid-responsive genes and miRNAs in strawberry receptacle fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, K.; Xue, X.; Deloire, A.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. Effects of Vine Water Status on Malate Metabolism and γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Pathway-Related Amino Acids in Marselan (Vitis vinifera L.) Grape Berries. Foods 2023, 12, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Berardini, T.Z.; Chen, G.; Crist, D.; Doyle, A.; Huala, E.; Knee, E.; Lambrecht, M.; Miller, N.; Mueller, L.A.; et al. TAIR: A resource for integrated Arabidopsis data. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2002, 2, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Leng, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, N.; et al. The complete reference genome for grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) genetics and breeding. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, K.; Yuan, G.; He, S.; Cong, P.; Zhang, C. Genome-wide identification and characterization of AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE (AIL) family genes in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Genomics 2022, 114, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Higgins, D.G. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2002, 2, 2.3.1–2.3.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.Y.; Zhu, Q.H.; Chen, X.; Luo, J.C. GSDS: A gene structure display server. Yi Chuan 2007, 29, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Han, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, B. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the LRX gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) and functional characterization of VvLRX7 in plant salt response. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillon, O.; Aury, J.M.; Noel, B.; Policriti, A.; Clepet, C.; Casagrande, A.; Choisne, N.; Aubourg, S.; Vitulo, N.; Jubin, C.; et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 2007, 449, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, A.; Yan, J.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, G.; Cong, P.; Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, C. MdAIL5 overexpression promotes apple adventitious shoot regeneration by regulating hormone signaling and activating the expression of shoot development-related genes. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Chen, S.; Sang, K.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Considine, M.; Yu, J.; Xia, X. Warm temperature activates the TCP15-HDA4 module to suppress shoot branching through promoting auxin biosynthesis and signaling in tomato. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 2082–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).