Abstract

Climate change and the resulting abiotic stresses that emerge due to anthropogenic activities are the main causes of agricultural losses worldwide. Abiotic stresses such as water scarcity, extreme temperatures, high irradiance, saline soils, nutrient deprivation and heavy metal contamination compromise the development and productivity of crops on a global scale. In this scenario, understanding the response of C4 plants to different abiotic stresses is of utmost importance, as they constitute major pillars of the global economy. To further our understanding of the response of C4 monocots, Setaria viridis and Setaria italica have gradually emerged as powerful model species for elucidating the physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of plant adaptation to abiotic stresses. This review integrates recent findings on the morphophysiological, transcriptomic, and metabolic responses of S. viridis and S. italica to drought, elevated heat and light, saline soils, nutrient deficiencies and heavy metal contamination. Comparative analyses highlight conserved and divergent stress-response pathways between the domesticated S. italica and its wild progenitor S. viridis. Together, these findings reinforce Setaria as a versatile C4 model for unraveling mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance and highlight its potential as a genetic resource for developing climate-resilient cereal and bioenergy crops.

1. Introduction

Climate change represents one of the most significant threats to the current global socioeconomic model, impacting various sectors, with a particular emphasis on agriculture. The increasing atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide ([CO2]) has been directly associated with the rise in global average temperature, leading to a higher frequency and intensity of extreme climate events [1]. Given the continuous population growth and the resulting increase in demand for food, biofuels, and other agricultural products, implementing strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change on agriculture is crucial for global food security and socioeconomic stability [2,3]. Agriculture, in particular, is highly vulnerable to climate variability, facing critical challenges such as rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns leading to droughts and floods, and an increasing frequency of extreme weather events projected for the coming decades [4].

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the global average temperature increased by 1.1 °C between the late nineteenth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, with projections indicating an additional rise of 2.0 °C by the end of the 21st century [5]. Among the primary abiotic stresses affecting agricultural productivity, extreme temperatures and water deficit stand out, accounting for annual crop yield losses ranging from 51% to 82% worldwide [6]. Water availability is widely recognized as one of the most critical limiting factors for agricultural productivity, with projections indicating that, over the next five decades, water stress alone will restrict productivity on more than 50% of the planet’s arable land [7].

Due to the necessity to maintain crop productivity in a changing climate scenario, one of the most central themes in plant biology is the unveiling of plant adaptation against oxidative stress in response to abiotic factors. Hence, adaptive responses and molecular mechanisms underlying plant-environment interactions can provide crucial tools for the development of management strategies and genetic improvement in agricultural crops [8]. Plants face various abiotic stresses, such as drought, light, temperature, heavy metals, hypoxia or anoxia, nutrient deficiency or toxicity, UV light stress, and pesticides, which negatively impact normal plant growth and development [9]. and promote the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, ultimately reducing growth and yield [10]. Furthermore, photosynthetic machinery is also severely affected (Sharma et al., 2019), in which the chemical reactions mediated by photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII), as well as the biosynthesis of chlorophyll undergo several changes [11].

Stress events mainly limit plant photosynthesis by reducing the CO2 assimilation via the Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) pathway [11], triggering the production of a large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant organelles such as plastids, peroxisomes, and mitochondria. ROS act as crucial signaling compounds in key cellular mechanisms that affect overall plant growth and development [12]. ROS molecules, such as H2O2, singlet oxygen, hydroxyl (OH−) and superoxide radical (O2−) [12], are produced in excess under stress conditions. To mitigate ROS, plants have antioxidant enzymes, which include detoxifying enzymes such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) [13]. Plants have developed other protective mechanisms, such as photorespiration, antioxidant systems, and alternative and cyclic electron flow to prevent photosynthetic losses [14].

C4 plants have a specific photosynthetic apparatus, which is particularly responsive to abiotic stress. They use distinct physiological and biochemical mechanisms to deal with abiotic stressors, but their sophisticated photosynthetic system also has limitations. Abiotic stresses affect the photosynthetic mechanism by reducing stomatal conductance, causing oxidative stress and decreasing the activity of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RUBISCO) [15]. Ref. [16] noticed they maintain greater photosynthetic efficiency despite moderate heat and water limitation due to their CO2-concentrating mechanism but show rapid decreases in assimilation when temperature or drought exceed their optimal thresholds. Under drought stress, C4 species respond with increased root-to-shoot ratio, osmolyte accumulation, and antioxidant defenses, although mesophyll-bundle sheath coordination frequently limits carbon fixation earlier than in many C3 species [17]. Heat stress tolerance has been connected to species-specific strategies for sustaining Rubisco activase function at high temperatures, emphasizing the significance of isoform variety in C4 grasses [18]. In response to salinity, chloroplasts emerge as primary targets, and tolerance is dependent on ion homeostasis, proteome changes, and the ability to mitigate oxidative damage [19]. These findings show that the resilience of C4 plants to abiotic stress needs to be deeply explored as a potential tool for plant breeding.

In this context, Setaria viridis and Setaria italica—also known as green foxtail and foxtail millet—appear as model plants for Panicoid grasses [20,21], especially because of the phylogenetic and metabolic proximity to species of economic interest of the Panicoideae family. In the case of S. viridis, it has a small diploid genome with a telomere-to-telomere chromosomal assembly of 395.1 Mb [22], as well as a short size (30 cm, on average), rapid life cycle (6 weeks, seed to seed), and large seed production, which made it a suitable model system for other C4 monocots [22,23]. For S. italica, the most recent genome assembly of the Yugu1 variety reports a total genome size of 405.7 Mb, which is similar to its wild counterpart. However, the size and life cycle differ greatly from S. viridis, since S. italica plants can reach up to 215 cm of height and have a generation time of 8–15 weeks from planting to seed maturity, depending on the accession [24]. Since its proposal as a model plant, the development of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing protocols contributed to its successful establishment as a model system [25,26,27].

It is widely considered that S. italica was domesticated in China from its wild ancestor S. viridis between 9000 and 6000 years before present time [28]. Following its domestication, S. italica became a widespread and staple crop in Chinese history, being referred to as one of the “Five Grains”, which were essential crops accounting for the majority of plant fossils in archaeological sites in China [29]. Currently, it is mostly cultivated in China and some parts of India, as well as in the USA, Japan, Indonesia, Australia, and other countries [30]. Its long history of cultivation in different countries resulted in a vast diversity of genetically and morphologically distinct landraces and cultivars, which have been employed by researchers to study the genetic basis of different plant traits [31]. In contrast to S. italica, which is a cultivated crop, S. viridis is a globally distributed invasive weed, that disturbs several plantations by competing for resources and hindering the growth of cereal crops [32]. In recent years, however, since its proposal as a model system for other C4 grasses, a myriad of studies have used it to study root development [33], response to abiotic stresses [34], biomass accumulation [35], among other traits. Though distinct in many aspects, both Setaria species share multiple similarities in their response to abiotic stresses, which resulted in the parallel emergence and adoption of both as model species for such studies.

Although plants have been extensively investigated for their physiological and molecular responses to abiotic stresses, a central question remains unclear: how do C4 plants respond to such stressors? In particular, the responses of Setaria species under conditions such as drought, heat, and salinity are still not fully understood. Recent studies suggest that Setaria exhibits species- and genotype-specific adaptations, including adjustments in photosynthetic efficiency, osmolyte accumulation, antioxidant activity, and gene expression related to stress tolerance [36,37,38]. In this review, we challenge ourselves to provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge on the physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms by which Setaria spp. associated with abiotic stresses, highlighting potential pathways for crop improvement and climate-resilient agriculture.

2. Drought Stress

Drought is probably the most well-studied abiotic stress in plants. And rightfully so, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, drought is responsible for 34% of the global losses in crop and livestock production [39]. Droughts are severely detrimental, since the high temperatures and reduced water availability compromise the plant metabolism, impair growth and reduce the quality and yield of crops [40] (Figure 1). For now, we will focus on the water deficit component of drought, seeing as high temperatures will be discussed in a further section.

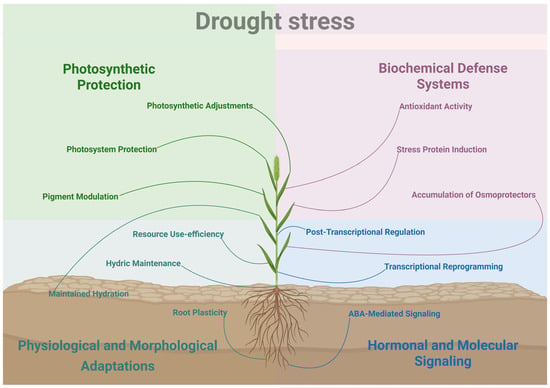

Figure 1.

Overview of multi-level drought stress responses in Setaria spp. Water preservation is achieved via morpho-physiological adaptations such as stomatal closure, leaf rolling, altered root architecture and improved water use efficiency. Photoinhibitory damage is mitigated by increased non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) and adjustments to the photosynthetic machinery. Biochemical defense systems to protect organelles and cellular structures involve the accumulation of osmoprotectants and osmolytes such as proline, and the activation of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, CAT, POD). Finally, molecular responses are orchestrated by ABA signaling and transcription factor activation (e.g., NAC, DREB, MYB), leading to the regulation of protective genes (e.g., LEA, HSPs, Aquaporins).

The lack of water compromises the development of all plants, including monocots, and members of the Setaria genus are no exception. Prolonged exposure to conditions of water deficit stunts the overall growth of S. italica and S. viridis, as shown by the reduced shoot length [41], decreased dry weight of the shoots [34,42], and impaired emergence of leaves and tillers [43]. Another effect of the water deficit is a premature emergence of panicles, which indicates an early transition into the reproductive phase [33]. Moreover, the yield is also compromised by drought stress, since reductions in the number of panicles and in the weight of individual panicles and grains have been observed [41,44].

Even though most studies focus on the effects of drought in the leaves and shoots, it is of the utmost importance to evaluate it in roots, since they are the first structure to perceive the reduced water availability. In foxtail millet, withholding the watering for 8 days resulted in an increase in the total root length and surface area, which may be a strategy to maximize the water absorption [38]. In multiple accessions of S. viridis, on the other hand, considerable reductions in the root system have been described due to a suppression in the postemergence growth of crown roots [33]. In contrast to S. viridis, S. italica exhibited an ability to maintain the growth of a small number of crown roots during water stress. This difference likely originated during the domestication process of S. italica, since the arrest in crown root emergence seems to be a conserved response to drought among other Poaceae species, such as sorghum, maize and switchgrass [33].

Considering that the decrease in water absorption compromises the accumulation of water in the tissues, the severity of the water deficit is often evaluated by measuring the decrease in relative water content (RWC) of leaves. This approach has been effectively applied in studies with S. italica [38,42] as well as S. viridis [33]. Another metric used to measure plant water status is the leaf water potential (LWP), which has also been applied in foxtail millet [45] and green foxtail [34]. The two parameters have been used to differentiate between drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive genotypes in both species [34,41,46], indicating that they are well-suited for this type of screening.

To cope with the decreased water availability and reduce the water losses by transpiration, grasses often go through a process of leaf rolling [47,48]. In S. italica, leaf rolling and a reduction in the exposed leaf area have been reported in different cultivars, such as Yugu1, Jigu39, Jingu21, and Longgu16 [38,42,49]. In S. viridis, a reduction in the exposed leaf area has been observed after air-drying treatment [50], but not after a milder water deficit promoted by 7 h of polyethylene glycol (PEG) exposure [46]. Another visual sign of drought stress in species of Poaceae is the loss of pigmentation and turgor in the leaves, which have been described in S. italica [42,49] and S. viridis [43]. Additionally, drought-sensitive varieties often exhibit earlier leaf rolling, withering and bleaching, when compared to drought-tolerant ones after exposure to water deficit [41,45].

One other consequence of the water deficit is a decrease in photosynthetic activity. Since plants reduce stomatal aperture even under mild water-limiting conditions, photosynthesis is limited due to the decreased CO2 diffusion from the atmosphere to the carboxylation site [51]. Consequently, gas exchange measurements are often used to indirectly monitor the photosynthetic activity of stressed plants. In S. viridis and S. italica, the CO2 assimilation (A), transpiration (E) and stomatal conductance (gs) have been shown to decrease proportionally to the level of water deficit [42,52]. Gas exchange measurements, therefore, can be a powerful tool for the identification of drought-tolerant [42,52] accessions, as demonstrated in S. italica by [41]. In drought-sensitive accessions of green foxtail, such as Ast-1, the water deficit results in a more marked decrease in A, E and gs, when compared to drought-tolerant ones, such as A10.1 [34]. On the other hand, [52] found that Ast-1 showed a higher resistance to dehydration than A10.1 by maintaining higher levels of A during longer periods of water deficit, contrasting with previous observations [34,46]. The Water Use Efficiency (WUE), which is a ratio between CO2 A and E, can also be used to monitor the drought tolerance of plants, since it represents how much inorganic carbon is being assimilated for each water molecule lost by transpiration. By using an interspecific S. viridis × S. italica recombinant inbred line (RIL), [53] devised a modeling approach to predict the relationships between WUE and plant size, demonstrating that WUE exhibits high heritability. The study also illustrated that WUE is responsive to soil water availability, which was previously described. In C4 monocots, especially in drought-tolerant cultivars, WUE may increase under water-limiting conditions, as demonstrated in S. viridis and S. italica [45,52]. Another reason for the decrease in photosynthetic activity during drought is the degradation of pigments and other components of the electron transport chain in the thylakoid membrane.

The process of chlorophyll degradation was previously characterized in Setaria viridis [34,46] and Setaria italica [38,54]. In drought-sensitive cultivars of foxtail millet, this degradation occurs more intensively than in drought-tolerant cultivars, indicating a greater susceptibility of the photosynthetic apparatus to water deficit [49]. This is also observed in green foxtail, in which this degradation occurs concomitantly with higher repression in chlorophyll synthase gene expression [34], an enzyme involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis. In both species, a preferential degradation of chlorophyll a (Chl a) relative to chlorophyll b (Chl b) has been observed under water-limited conditions [46,55]. During drought stress, Chl a is preferentially degraded compared to Chl b due to its central role in the reaction centers of photosystems I and II, where it directly participates in the conversion of light energy into chemical energy. This functional position exposes Chl a to excess excitation energy and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are enhanced by the reduction of CO2 assimilation caused by stomatal closure under water deficit conditions [56].

The degradation of components of the electron transport chain and the diminished CO2 uptake during drought reduce the available pool of oxidized electron acceptors (quinones and plastoquinones). Environmental stress also accelerates the photoinhibition of Photosystem II (PSII) [57]. Therefore, during drought, the non-photochemical dissipation of the chlorophyll excitation energy is increased, mainly in the form of heat and fluorescence, which can be monitored through the measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics. In S. viridis and S. italica, it is well documented that the limited water availability leads to a reduction in the maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), as well as the effective photochemical efficiency (ΦPSII) [43,45,46]. It is worth mentioning that even though C4 plants exhibit a higher WUE than C3 plants and are generally considered more photosynthetically efficient, they often present lower Fv/Fm values [57]. In S. italica and S. viridis, this phenomenon is frequently accompanied by an increased non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), which represents the thermal dissipation of the excess energy, as well as a decrease in the coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP), which represents the proportion of open PSII reaction centers [42,50]. More specifically, in S. viridis, an exposure of 3 to 10 days also resulted in a decrease in electron transport quantum yield (ΦEo) and efficiency (ΨEo) [43]. The multiple chlorophyll fluorescence parameters can also be used to differentiate between drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive accessions and cultivars, as demonstrated in S. italica [45] and S. viridis [46].

Reductions in photochemical efficiency are often also attributed to photoinhibition due to damage caused by the increased amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during drought stress. There are several strategies to indirectly measure the oxidative damage, such as the quantification of the malondialdehyde (MDA) content, which is generated by ROS-induced lipid peroxidation. The increase in MDA content is well documented in several species and green foxtail, and foxtail millet are no exceptions [34,38,42,58]. Another strategy to evaluate the oxidative damage during drought stress, which has been effectively applied in leaves of S. viridis and S. italica, is the measurement of electrolyte leakage. The relative electrolyte leakage can be used to infer the severity of oxidative stress, because it is a consequence of the oxidative damage in cell membranes. Under distinct water deficit conditions, increased levels of electrolyte leakage have been observed in leaves of S. viridis and S. italica [38,45,46,50]. In roots, however, a reduction in electrolyte leakage levels was observed after 6 and 10 days of exposure to PEG-8000 (7.5%) [43].

To respond to the rising levels of ROS during water deficit, plants often increase the synthesis of ROS-scavenging enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), lipoxygenase (LOX), among others. In S. italica (Yugu1), exposure to drought conditions induced the expression of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in seedlings [38]. In mature plants of the same cultivar, increased SOD and POD activities were detected, as well as an up-regulation of LOX1 and LOX5 [55], involved in stomatal closure, activation of antioxidant enzymes, and osmoprotectant synthesis, LOX1 and LOX5 help mitigate the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and limit cellular damage under drought stress. Additionally, LOX1/LOX5-derived oxylipins contribute to jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis, regulating the expression of drought-responsive genes and enhancing plant survival and physiological maintenance [59,60]. Compared to Yugu1, the POD activity of the drought-sensitive S. italica variety AN04 was much lower [58]. In the tolerant S. italica M79 genotype, drought resulted in the up-regulation of 63 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in redox regulation, such as genes encoding SOD, LOX, APX, GPx and POD [45]. This same genotype also exhibited increased CAT activity in relation to its parental genotypes. Similar results have been observed in the drought-tolerant Zha-1, A10.1 and Ula-1 accessions of S. viridis, which exhibited higher CAT expression and catalase activity after 7–10 days of water withholding when compared to drought-sensitive accessions [34]. Moreover, Amoah et al. (2023) proposed “drought hardening” as an efficient strategy to mitigate future drought stress [61]. Acclimated S. italica showed higher drought tolerance during subsequent stresses compared to non-acclimated plants. “Hardened” plants displayed enhanced antioxidant defenses and elevated anthocyanin and polyphenol content, resulting in more effective ROS scavenging and increased photosynthetic efficiency, total biomass, tissue water content and photosynthetic pigment content.

Another plant response to drought-induced oxidative stress is to increase the synthesis and accumulation of osmolytes and antioxidant metabolites. Among the metabolites that accumulate during water deficit, proline is probably the most well-studied. It is an osmoregulator, shielding cell molecules, organelles and membranes from the damage caused by ROS, but it also acts as a storage of carbon and nitrogen in stressed plants [62]. In S. italica and S. viridis, different methods to promote water deficit have been shown to induce the accumulation of proline in leaves [34,54]. The up-regulation by water stress has also been reported for genes of the proline biosynthesis pathway, such as pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (P5CR) and delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase 2 (P5CS2) [34,42,46]. In roots, there is less information available, but 6 and 10 days of exposure to PEG-8000 (7.5%) promoted only a slight induction in the expression of P5CS2 in S. viridis, with no significant alteration in the proline content [43]. Along with proline, other metabolites that play a role in osmoregulation have been reported to accumulate during drought in foxtail millet and green foxtail [42]. Cultivars of both species that are more tolerant to drought have been shown to contain a higher content of soluble proteins and soluble sugars, which can help with osmoregulation [34,41,49]. Increased levels of glycinebetaine and gliadin have also been reported in S. italica under conditions of water deficit [44,54]. Glycinebetaine acts as an osmoprotectant, contributing to the stabilization of proteins and membranes, maintenance of enzymatic activity, and reduction in oxidative damage during dehydration stress. In contrast, gliadin is a storage protein whose accumulation may be altered under drought conditions, potentially affecting the protein composition and quality of the grains [44,54]. In the roots of S. italica (Yugu1), [38] reported greater alterations in the protein abundance during drought stress when compared to leaves of the same plants. Conversely, after rewatering, the protein abundance of leaves is mainly associated with photosynthetic activity, while the protein abundance of roots seems to be primarily related to the regulation of secondary metabolism.

Plants possess several mechanisms for transducing the stimulus of a water deficit into physiological and molecular responses. Phytohormones are one of the main components of drought signal transduction and, among them, abscisic acid (ABA) plays a major role in the regulation of signaling during desiccation. The ABA content has been shown to increase under water deficit conditions in S. italica [42]. In S. viridis, drought-sensitive accessions exhibited the highest ABA levels during drought, as well as the highest up-regulation of zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), which are involved in the biosynthesis of ABA [34]. The activation of ABA-responsive genes depends on a signaling cascade composed of three major components: ABA receptors of the PYR/PYL/RCAR family, 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs) and Snf1-related protein kinases 2 (SnRK2s) [63]. Recently, [64] characterized the ABA pathway signaling components in S. viridis and S. italica and found a high conservation in all three families. Besides one PP2C gene that was duplicated in S. viridis, all other genes exhibited a 1 to 1 orthology relationship between the two species. The main differences between the orthologues were due to the shorter 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the S. italica copies. Studies with both species report that PYL genes are downregulated by the water deficit [64,65], while PP2C genes have been reported as being upregulated [65,66] or downregulated [34], depending on the experimental conditions. The expression pattern of SnRK2 genes seems to show great variability in response to drought, but is mostly upregulated [34,64,65]. The ABA signaling cascade culminates in the activation by SnRK2 of several transcription factors, which in turn regulate the expression of multiple other genes involved in the drought response. In S. italica, the promoters of water deficit-induced DEGs are enriched with ABA-responsive elements (ABREs), which are binding sites for the ABF (ABA-responsive element binding factors) family of transcription factors [66]. The ABF family is also induced by drought stress in plants and S. italica is no exception [42]. Previous reports have also shown that promoters of ABA signaling components of S. viridis contain ABREs [65], which may indicate a positive feedback regulation of ABA response.

Besides ABFs, there are other transcription factor families that play a major role in the regulation of gene expression in response to drought. Among them, the MYB, NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2), DREB/CBF (Dehydration-responsive element binding/C-repeat binding factor), WRKY, bZIP, HD-ZIP and HSF (Heat Shock Factors) families stand out as the more well-known. Different RNA-seq projects with S. italica have demonstrated that transcription factors from the aforementioned families are differentially expressed by the water deficit [45,66,67]. Within these transcription factor families, reliable drought marker genes have been identified for S. viridis, such as NAC6 and DREB1C, both of which are up-regulated by PEG and air-drying-induced water deficit and seem to aid in the adaptation of the plant to drought [43,50]. It is worth mentioning that drought-marker genes which are repressed by water deficit have also been identified. One example is WRKY1, which negatively regulates drought response by repressing the expression of MYB2 and DREB1A, as well as inhibiting the ABA-mediated stomatal closure [68]. In S. viridis, WRKY1 is repressed after 7 h of PEG-8000 exposure in the drought-tolerant A10.1 accession but is induced in the sensitive Ast-1 accession [46]. Besides the previously mentioned transcription factor families, transcriptomic studies have also identified DEGs from other less discussed families, such as bHLH, DOF, C2H2 and ERF [49,67]. Recently, [69] conducted a characterization of the MADS-Box family of transcription factors in foxtail millet and green foxtail, which is not often associated with drought response. Nonetheless, a considerably large number of cis-elements associated with dehydration response were found in the promoters of SiMADS-Box genes. Moreover, overexpression of SiMADS51 in Arabidopsis resulted in a lower drought stress tolerance, as evidenced by the impaired germination, shorter roots, reduced fresh weight and lower survival rate under water deficit conditions. In rice, overexpression of SiMADS51 also resulted in a lower survival rate after drought stress, along with reduced POD and SOD activity [69]. The authors propose that SiMADS51 may act as a negative regulator of the drought stress response, inhibiting the expression of stress-related genes involved in stress response (DREB2A, MYB2), ABA biosynthesis (NCED1, NCED3), ABA signaling (PP2C06, PP2C49) and proline synthesis (P5CS1).

Although transcription factors are often the focus of studies about gene expression regulation, a growing field is the regulation by non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and micro RNAs (miRNAs). Though scarce in the literature, some studies have tried to characterize this regulation in species of the Setaria genus exposed to water deficit. A study by [66] identified differentially expressed siRNAs and lncRNAs in foxtail millet seedlings treated with PEG-6000 for 7 h. Few lncRNAs were identified as regulated by the water stress, but the clusters of siRNAs of 21 nt and 24 nt were enriched in specific gene-rich regions of the genome, which suggests a role in transcription regulation during drought response. A more recent study with S. viridis performed small RNA deep sequencing to identify differentially expressed miRNAs and their targets in response to water deficit conditions [52]. Among the identified miRNAs, some of them targeted transcription factors from the MADS-Box, MYB, and NAC families. Curiously, several novel miRNAs targeted genes involved in cell wall synthesis and remodeling, especially during the early responses to drought, which may be an initial adaptive mechanism to water deprivation.

During drought stress, ncRNAs and transcription factors regulate gene activation and repression, shaping the plant’s transcriptional response. RT-qPCR is commonly used to assess these expression changes, requiring stable reference genes for accurate normalization. In S. italica, RNA POL II and EF-1α were identified as reliable reference genes under drought, with APRT also showing stable expression [70]. In S. viridis, suitable reference genes include SDH, KIN, and SUI1 [71]. Additionally, [50] recommended using TPI + GAPDH during the vegetative stage and Cullin + Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 during the reproductive stage for normalization in drought experiments.

There are multiple classes of genes that are regulated in response to the drought stimulus. In general, photosynthetic components are down-regulated during water stress, as seen in S. viridis in a study by [34], in which multiple photosynthesis-related genes were repressed, especially in the drought-sensitive Ast-1 accession. The list of repressed genes included photosystem 1 (PS1), ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit (RbcS), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), among others. Similar results have been observed in S. italica, since water deficit resulted in the downregulation of photosystem II, photosystem I, and cytochrome b6/f complex-related genes [49]. Furthermore, RNA-seq experiments with foxtail millet have shown that the downregulation of photosynthesis-related genes during water deficit is often accompanied by a repression of carbohydrate metabolism genes [49,66].

There is also a myriad of classes of genes that are normally up-regulated and several of them show great promise for biotechnological applications. Heat-shock proteins are one example, since they act as molecular chaperones, ensuring correct folding of other proteins and have been shown to be up-regulated by water deficit in both foxtail millet [41,66] and green foxtail [43]. Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins are another notable example, due to their role in protecting cellular components from water-stress-induced damage, assisting with protein folding and acting as molecular chaperones for other proteins [72]. Among them, the group II of LEA proteins, which are known as dehydrins, are of particular interest, since their overexpression has been shown to confer tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses [73]. In RNA-seq data of S. italica, up-regulation of several LEA proteins and dehydrins has been recorded following water deficit [45,66], while in S. viridis SvDHN1 and SvLEA have been shown to be induced by PEG in water stress conditions [43,50]. Another group of proteins with significant biotechnological potential is the membrane water channels, also known as aquaporins. In S. italica, aquaporin genes are often up-regulated by drought stress as a mechanism to increase water uptake and transport [45,66]. Furthermore, in a study by [34], drought-sensitive accessions of S. viridis exhibited the lowest expression of aquaporins PIP-1, PIP1-2 and PIP2-1 genes when compared to drought-tolerant accessions.

The fact that S. italica is a species domesticated from its wild relative S. viridis allows for the use of interspecific recombinant inbred lines (RILs) to study different aspects of the drought response. As mentioned previously, [53] applied this strategy to identify Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) associated with water use efficiency. By doing so, their results showed that alleles from both parental species contribute to the WUE, indicating that neither is fully optimized. This approach has also been applied by Qie et al. (2014) [74] to study the genetic basis of drought tolerance, using a RIL population generated from a cross between the S. italica cultivar Yugu1 and the S. viridis W53 accession. Their results identified 18 QTLs, 8 of which were alleles from S. viridis that contributed to drought tolerance. A S. viridis × S. italica RIL population has also been used to investigate in grass species the response of the crown roots to water loss [33]. Through QTL mapping, the authors showed that the responses of crown roots to water deficit are regulated by a small number of specific loci. These loci were probably selected during the domestication process of S. italica and likely contribute to the higher tolerance to desiccation of its crown root system when compared to S. viridis. This approach based on the comparison of wild and domesticated cultivars has been applied to great success, as shown in a recent study by [75], which analyzed the SiUBC39 gene. Their results indicated that the SiUBC39 gene was strongly subjected to selection during the domestication of S. italica and, by evaluating CRISPR knockout lines, they were able to obtain phenotypes similar to S. viridis (reduced plant height and grain weight). Moreover, the mutant plants exhibited a superior performance under drought stress, highlighting the potential of such comparative approaches for the discovery of new targets for genetic improvement [75].

3. Extreme Temperatures

Anthropogenic climate change has increased the frequency of extreme temperature events, such as heat and cold waves, leading to significant losses in agricultural productivity and threatening global food security [76]. Temperatures outside the optimal range disrupt cellular homeostasis, impairing plant growth, development, and metabolism [77] (Figure 2). Among temperature extremes, heat stress has received greater scientific attention than cold stress, and studies on chilling in Setaria species remain limited, despite its potential impact on agronomically important crops. Under cold stress, S. viridis exhibits repression of SvPYL and induction of SvSnRK2 and SvPP2C, alongside marked reductions in photosynthetic efficiency and changes in stomatal conductance [65]. Furthermore, [78] reported extensive transcriptomic reprogramming (7911 DEGs), activation of osmoprotective pathways, cellular remodeling and signaling, repression of core biological processes, and the prominence of key regulators such as CBF-L, TINY1/2, AP2/ERF, MYB, and BBX under cold stress [78]. Another recent study demonstrated how S. viridis accessions A10.1 and Ast-1 under gradual or sudden cold stress suffer significant reductions in gas exchange rates and total biomass, as well as damage to the photosynthetic machinery [79]. S. viridis is also known for its high thermal plasticity, with optimal performance between 29/19 °C and 35/25 °C, and reduced growth under extreme temperatures, reinforcing its physiological and morphological adaptability [80].

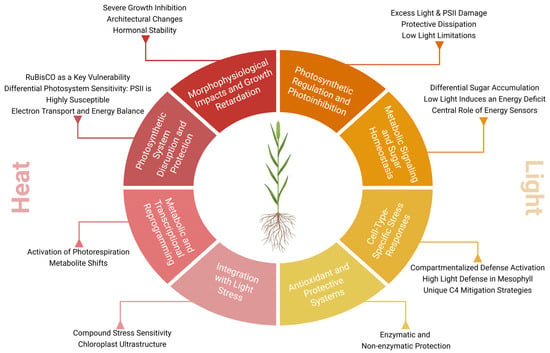

Figure 2.

Integrated responses to elevated temperature and irradiance in Setaria spp. Heat and light stress usually co-occur and thus elicit similar responses such as photoprotection mechanisms, antioxidant enzymes and metabolic shifts. Heat stress results in reduced stomatal conductance and increased photorespiration and cyclic electron flow. Excessive light intensity directly modulates sugar-signaling pathways (e.g., SnRK1, HXK), carbon allocation and ROS-scavenging.

Conversely, high temperatures are an increasingly critical threat, compromising essential functions such as photosynthesis, membrane integrity, protein stability, and hormonal balance. A detailed understanding of the morphophysiological, chemical, and molecular responses of plants to heat stress is fundamental for developing biotechnological strategies that enhance thermal productivity [81]. The identification of metabolic pathways and key genes involved in heat adaptation is crucial for the development of cultivars that are more resilient to extreme climatic conditions [82].

Plants of S. viridis subjected to 42 °C/32 °C (day/night) showed a 50% reduction in dry biomass of roots and shoots, with no change in the root/shoot ratio. The typical phenotype includes pronounced dwarfism and atrophy, though hormonal analyses indicated that the levels of salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and phenylacetic acid (PAA), an auxin analogue, remained unchanged under these conditions [83].

A comparison between plants under control conditions and those exposed to high temperatures revealed a reduction in dry weight during the flowering and grain-filling stages. This reduction is attributed to factors such as decreased height, reduced leaf area, and shortened growth period. Elevated temperatures directly impact leaf area, with significant reductions compromising the photosynthetic rate and, consequently, productivity. The strong correlation between reduced leaf area and leaf narrowing reflects an adaptive defense strategy against photo-oxidative damage. This mechanism is also observed in other important crops, such as maize [84], rice [85], and sorghum [86].

RuBisCO, the primary enzyme responsible for CO2 fixation in plants, has its activation limited under high-temperature conditions, compromising the balance of its inactivation [87]. This enzyme exhibits complex activities with variable kinetics in response to temperature, catalyzing the first steps in the photosynthetic and photorespiratory pathways, with reaction rates determined by carboxylase and oxygenase activities, which increase with rising temperature [88]. When CO2 fixation is inhibited at high temperatures, thylakoid energization is affected, as evidenced by changes in electrochromic absorption, non-photochemical quenching, and light scattering, indicating that the energy that would be used in the Calvin cycle is not absorbed [89]. The reduced RuBisCO activation at high temperatures is associated with its thermolability [90]. Hence, the reduction in RuBisCO levels is identified as a key factor determining the negative impacts of heat stress on photosynthesis [15]. However, plants possess certain plasticity to adjust photosynthesis to optimal growth temperatures, which includes changes in the ideal temperature for photosynthesis in response to seasonal variations, consequently enhancing the efficiency of the process under the new thermal conditions [91]. In S. viridis, RuBisCO exhibits kinetic responses to elevated temperatures that are comparable to those observed in C3 plant species, suggesting the evolutionary conservation of the enzyme’s kinetic parameters across species with different photosynthetic types [92] and its function.

ATP synthesis under moderate heat stress primarily occurs due to RuBisCO activation and photorespiration [18]. Moderate heat significantly affects the reactions of the cytochrome complex and PSI, which is more susceptible to damage than PSII under heat stress, while PSII and the stroma undergo oxidation, indicating a redox imbalance in the different compartments of the photosynthetic electron transport system [93]. The ability of plants to maintain optimal rates of CO2 assimilation and leaf gas exchange is directly proportional to their heat tolerance. Stomatal conductance and transpiration rate are closely related to leaf temperature, with the maintenance of net CO2 assimilation rates acting as a reliable indicator of the plant’s ability to tolerate high temperatures [94]. Temperatures above the ideal levels affect stomatal conductance, intracellular CO2 concentration, and leaf water status. Stomatal closure alters intracellular CO2 concentration under heat stress conditions, triggering the inhibition of net photosynthesis [95]. Furthermore, temperature changes directly influence the vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which modifies the plant’s hydraulic conductance and water supply to the leaves [96,97]. Chlorophyll biosynthesis in plastids is significantly compromised under heat stress, resulting in the degradation of chlorophyll molecules [98]. At elevated temperatures (35–45 °C), there is induction of cyclic electron transport and leakage from thylakoid membranes, compromising the integrity of the photosynthetic machinery [99]. Moreover, transcripts of key photorespiratory enzymes, including PGLP1, GOX, GGT1, SGAT, HPR, GDC subunits, pMDH2, Fd-GOGAT, and GS2, were markedly reduced. However, the proteins SGAT, SHMT, and HPR showed increased accumulation. This imbalance led to a decrease in serine and accumulation of glycerate, whose conversion to 3-PGA may be impaired due to the absence of GLYK protein. Additionally, glutamate and 2-oxoglutarate, both involved in ammonium assimilation, were significantly reduced [83]. Mild heat stresses have less detrimental impacts, whereas severe temperatures can cause irreversible damage. Nevertheless, cyclic electron flow at high temperatures maintains the energy gradient across the thylakoid membrane, preserving ATP homeostasis and preventing significant structural damage [100]. This energetic stability is crucial, as it allows photosystem I (PSI) and II (PSII), the CO2 reduction pathways, photosynthetic pigments, and electron transport systems to function effectively, ensuring the overall integrity of the photosynthetic machinery.

Together, photosystem I (PSI) and II (PSII), the CO2 reduction pathways, photosynthetic pigments, and electron transport systems are essential components of the photosynthetic machinery. Any deficiency in these elements results in a global inhibition of photosynthesis [101]. The photosynthetic apparatus acts as an environmental stress sensor, responding to cellular energy imbalances associated with modifications in the redox state. Among the responses to heat stress, photosynthesis is one of the most sensitive processes, with PSII being the first point of inhibition compared to other cellular structures [94]. This heightened susceptibility is mainly due to two factors: (i) the increased fluidity of thylakoid membranes, which displaces the light-harvesting complex, and (ii) PSII’s reliance on the dynamic integrity of electron flow.

PSII is especially susceptible to heat stress due to two main factors: (i) increased fluidity of thylakoid membranes, which displaces the light-harvesting complex, and (ii) PSII’s dependence on the dynamic integrity of electron flow. High temperatures may causecan lead to the dissociation of the water-oxidizing complex, displacement of the light-harvesting complex, and destabilization of the PSII reaction center [102].

Heat also induces the dissociation of ions such as Cl−, Mn2+, and Ca2+ from the PSII pigment-protein complex, as well as the release of extrinsic polypeptides from thylakoid membranes, further compromising the structure and functionality of PSII [103]. Among the intrinsic proteins of PSII, the D1 protein is particularly sensitive, being cleaved by the FtsH protease, which migrates from the stroma to the grana for degradation [104,105]. The diffusion of photodamaged D1 proteins is hindered by the loss of membrane integrity at extreme temperatures, reducing repair efficiency. Genetic studies suggest that manipulating the saturation levels of fatty acids in thylakoid lipids may increase resilience by initiating more efficient repair processes [106]. Under heat stress, transcripts of LHC II and PS II were downregulated, accompanied by significant reductions in the psbO, psbP, and psbQ proteins. In the Cytochrome b6f complex, all transcripts were markedly reduced, along with decreased levels of the PETA and PETC proteins [83]. In contrast, PSI exhibits greater thermal stability compared to PSII. Under high temperatures, the cyclic electron flow around PSI is intensified, contributing to the maintenance of the proton gradient in the thylakoids and promoting ATP production as a defensive mechanism [107]. Thus, PSI serves as a central element in protecting photosynthetic machinery from heat stress-induced damage.

LHC I and PS I subunits also showed reduced transcript levels, although with minimal changes at the protein level. In ATP synthase, transcript levels uniformly decreased, while ATPB, ATPC, ATPF, and ATPX proteins were significantly reduced. The NDH complex and PGR5, both associated with cyclic electron flow, exhibited strong reductions in both transcript and protein levels. This coordinated downregulation suggests a shared regulatory mechanism. Nevertheless, the electron transport capacity was maintained [83].

Exposure of S. viridis to high temperatures and light intensities results in significant reductions in net CO2 assimilation rates, with high light intensity inducing pronounced photoinhibition in the leaves [108]. During a 4 h treatment at 40 °C, leaf temperature increased from 31 °C to 37 °C [109]. This thermal increase directly impacted photosynthetic parameters, including PSII operating efficiency, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and electron transport rate, as assessed by gas exchange measurements and chlorophyll fluorescence [110]. Additionally, differential regulation of genes associated with metabolic pathways related to photosynthesis was observed, along with structural changes in chloroplasts.

Under heat stress, a reduction in the expression of several genes was noted, while the levels of SGAT [111], SHMT [112], and HPR [113] were increased. These genes are upregulated to support the photorespiratory cycle. SGAT facilitates the conversion of serine and glyoxylate to glycine, SHMT recycles glycine into serine while providing one-carbon units for metabolism, and HPR reduces hydroxypyruvate to glycolate [108,113,114,115,116]. Together, they help maintain carbon metabolism, prevent accumulation of toxic intermediates, and protect cells from oxidative damage, acting as a key adaptive response to heat stress. Metabolically, there was a decrease in serine and an increase in glycerate, which requires conversion to 3-PGA. However, the absence of detectable GLYK protein raises uncertainty regarding the relationship between glycerate accumulation and its metabolism. Other metabolites, such as glutamate and 2-oxoglutarate, also showed reduced levels in heat-stressed plants [86].

Plants of S. viridis under high temperatures exhibited a strong reduction in leaf starch accumulation, while sucrose, glucose, fructose, and various osmoprotective sugars accumulated intensely. Transcripts associated with starch biosynthesis (APL1, APS1, SS, and SBE) were downregulated. In the sucrose pathway, protein levels of cFBA, cPGI, cPGM, UGP2, and SPP were upregulated. Conversely, genes involved in the raffinose pathway were strongly induced, consistent with the pronounced accumulation of raffinose and galactinol, showing differential distribution between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells [83].

4. Light Stress

Light is a critical environmental signal that modulates photosynthesis, carbon assimilation, and overall plant growth. However, fluctuations in light intensity constitute significant abiotic stress, impacting a plant’s primary metabolism by disrupting various physiological, biochemical, and molecular processes [117] (Figure 2). Light stress occurs when the absorption of light energy exceeds the capacity for its use in photosynthesis. This over-excitation at the photosystems leads to photoinhibition, a process characterized by the functional failure of PSII reaction centers and a decline in photochemical efficiency [118,119]. A key mechanism of damage involves the highly oxidizing potential within PSII, which damages core proteins like D1. When the rate of D1 degradation surpasses its repair, PSII centers become inactivated [120].

A consequence of excess light is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage both PSI and PSII, reduce mitochondrial activity, and force plants to dissipate excess energy as heat or fluorescence [15,121]. This negatively affects key photosynthetic parameters, including the maximum quantum efficiency of PSII, electron transport rate, and the chlorophyll/carotenoid ratio [122]. To mitigate the excessive ROS generation, plants employ antioxidant enzymes, protective compounds and repair mechanisms [123,124]. Specific protective compounds include plastoquinone-9, which acts as an antioxidant to reduce PSII photoinhibition [125], and secondary metabolites like anthocyanins [126]. Conversely, low light stress also impairs photosynthesis, primarily by reducing stomatal conductance and disrupting the photosynthetic mechanism. This leads to a dramatic increase in intercellular CO2 concentration and a decline in the net photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, and water-use efficiency [127,128,129].

Ref. [130] evaluated the changes in carbon metabolism and in the transcriptome of S. viridis leaves acclimatized to high (1000 µmol m−2 s−1), medium (500 µmol m−2 s−1) and low light intensity (50 µmol m−2 s−1). Under low light conditions, photosynthetic efficiency is substantially impaired, leading to reduced growth, lower turgor, and diminished photosynthetic capacity. This is coupled with a significant reduction in key signaling sugars, namely glucose, sucrose, and trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P), which are crucial for downstream metabolic regulation. Conversely, under high light intensity, the photosynthetic machinery remains robust despite a marked accumulation of sugars. The induction of sugar accumulation under high light does not suppress photosynthesis. In fact, it suggests that S. viridis employs protective and compensatory mechanisms to mitigate any potential photoinhibitory effects. While low light primarily triggers a decline in the energetic and metabolic status of the plant, high light intensity drives a reallocation of carbon resources that may facilitate enhanced stress resilience. The expression of sugar signaling components is closely intertwined with light-mediated gene regulation in S. viridis. Low light caused a pronounced down-regulation of anabolic gene expression and an up-regulation of genes involved in catabolic processes, suggesting a metabolic shift toward energy conservation [130]. Central to this response is the modulation of hexokinase (HXK) and the sucrose non-fermenting 1 (Snf1)-related protein kinase, SnRK1. Under low light, the depletion of sugars results in the activation of SnRK1 targets in an attempt to reestablish energy homeostasis. In contrast, the sugar accumulation resulting from high light intensity represses SnRK1 signaling pathways, suggesting sugar availability may buffer the regulatory impact on energy-sensing mechanisms. Moreover, the differential expression of HXK under varying light conditions underscores the role of glucose sensing in fine-tuning metabolic processes based on light intensity [130].

While light intensity is a major determinant of photosynthetic performance and sugar metabolism, its impact is further modulated by interactions with other abiotic stresses, such as heat. Ref. [108] investigated how S. viridis responded to a four-hour period of high light and temperature. Their findings indicate that both stresses result in comparable reductions in photosynthetic efficiency. Transcriptomic analysis revealed key differences in differentially expressed genes between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells. Under high light, differentially expressed ROS-scavenging genes and HSPs were upregulated in mesophyll cells, while the bundle sheath-specific DEGs were downregulated. Curiously, the inverse was observed for ROS-scavenging genes under high temperature, while HSPs were upregulated in both cell types. The differential responses observed in mesophyll versus bundle sheath cells warrant further investigation to understand how cellular compartmentalization contributes to the overall resilience of C4 photosynthetic systems.

Comparative studies in S. italica, the domesticated foxtail millet, provide additional insight into how light stress influences photosynthesis and yield determinants. A field study conducted during the grain-filling stage demonstrated that increased shading leads to a marked reduction in net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, effective quantum yield of PSII, and electron transport rate [131]. Conversely, intercellular CO2 concentration increased, reflecting a shift in the balance between CO2 supply and assimilation. Additionally, low light intensity changed the double-peak diurnal variation in photosynthesis to a single-peak curve, signifying altered light absorption and energy conversion processes [131]. These changes not only diminished the available assimilates for grain filling but also directly impacted yield by reducing fresh grain mass per panicle [131]. The sensitive response of S. italica to low light thus parallels the metabolic constraints observed in S. viridis, although the outcomes are more directly measurable in terms of agricultural productivity.

5. Salt Stress

Saline soils are characterized by the presence of water-soluble salts, with most studies on salinity stress focusing on sodium chloride (NaCl) due to its non-nutritional nature for plants [132]. Salt stress in plants can be split into two major components: osmotic stress, resulting from decreased soil osmotic potential, and ionic stress, caused by the excessive uptake of Na+ and Cl− ions [133] (Figure 3). Soil salinization arises from natural processes, such as mineral weathering, or anthropogenic activities, with agricultural irrigation being the largest perpetrator [132]. Given the increasing challenges imposed by climate change on agriculture, and the rising need for artificial irrigation, soil salinization is becoming increasingly important and demands more studies to find sustainable alternatives when facing this problem.

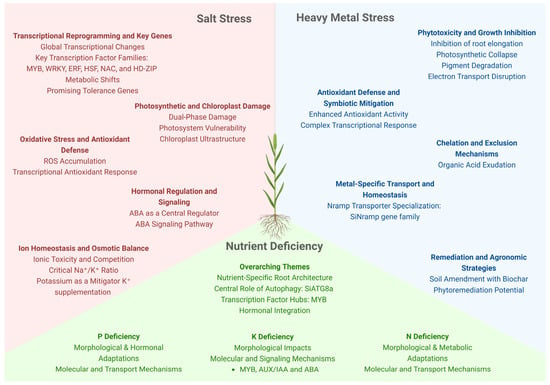

Figure 3.

Setaria spp. stress responses to salinity, nutrient deficiency, and heavy metal toxicity. Under saline soils, ion homeostasis is central; Na+ is excluded through the roots or sequestered into the vacuole, while K+ uptake is prioritized. Several TF families (MYB, NAC, WRKY, bZIP) respond to salt stress and modulate the molecular defenses against it. Root architectural changes are key under nutrient starvation: while low nitrogen reduces root growth, phosphorus deficiency promotes lateral root proliferation and enhanced foraging. Autophagy pathways (e.g., SiATG8a) are depled under nitrogen or phosphorus scarcity, and soluble proteins act as nutritional reserves. Moreover, integrated hormonal and transcriptional regulation are critical for N, P and K deficiencies. Heavy metal stress is mitigated by ion chelation and compartmentalization/exclusion via metal transporters (e.g., Nramp). Remediation strategies such as soil amendment with biochar and phytoremediation strategies show promise in contaminated soils.

Part of the ionic stress imposed by soil salinity is due to competition for ionic channels. Na+ competes with essential cations, such as Ca2+, K+ and NH4+, while Cl− competes with anions like NO3−, potentially resulting in a nutritional deficit [132]. Ionic toxicity further inhibits photosynthesis, as evidenced by reductions in carbon assimilation and photosystem II (PSII) activity [134,135]. Evidently, as salinity increases, so do its adverse effects on germination, morphology and biomass accumulation.

Recently, several studies have explored the effects of salinity on Setaria species, ranging from its morphophysiological effects to the molecular mechanisms underlying salt stress. Seed germination, a pivotal stage in a plant’s life cycle, is particularly vulnerable to salt stress. Salinity commonly reduces germination rates, primarily through the modulation of ABA and ethylene levels, both of which regulate seed dormancy [136,137]. The negative effects of increased salinity on the germination rates of S. viridis and S. italica have also been explored. In S. viridis, elevated salinity delays germination, with higher NaCl concentrations significantly reducing germination rates. However, low salt concentrations appear to have minimal impact on seed germination [138,139]. Moreover, the effects of salinity on the germination of S. italica seeds are comparable to those in S. viridis. Recent studies have shown that a degree of variation in tolerance to salt exists among accessions [140,141]. Han et al. (2022) evaluated 104 S. italica accessions under 170 mM NaCl and reported a reduction in the germination rates, as well as in plumule and radicle length, underscoring the importance of genetic diversity in salt tolerance. Ref. [139] also demonstrated that seedlings of the A10.1 accession 9 days after sowing (DAS) suffered a large reduction in foliar area when grown in media containing 90 mM NaCl.

Salinity further impairs post-germination growth by reducing water uptake, inducing stomatal closure, and inhibiting carbon assimilation [133,142]. Recent studies on S. viridis revealed that salt stress significantly diminishes biomass accumulation [139,143]. Ref. [143] investigated the long-term effects of salinity on three S. viridis accessions, A10.1, ME034V, and Ast-1, and observed varying degrees of tolerance, with Ast-1 consistently presenting itself as the most sensitive of the three. While all accessions exhibited reduced total dry weight, Ast-1 showed a drastic decrease in shoot-to-root ratio, unlike A10.1 and ME034V, where this ratio increased [143]. Ref. [138] further reported substantial reductions in root and coleoptile length when seedlings were grown on media supplemented with 50 mM NaCl, with more severe effects at 100 mM.

In addition to reductions in biomass, salt stress induces distinct morphological changes, such as lesions on the primary and crown roots, as well as yellowing and swelling of the roots. Root emergence also seems to be impacted, as the final number and length of the crown roots are often reduced [143]. Aerial tissues are also affected, with symptoms such as leaf curling, burnt margins, and chlorosis [143]. Moderate salt stress causes flattening of the epidermal cells, while severe stress results in increased leaf thickness and intercellular spaces [144]. Severe stress may completely halt growth and cause leaf necrosis [143]. Ref. [139] further observed complete plant mortality within five days of irrigating S. viridis with solutions exceeding 25.8 dS/m salinity.

Similarly to drought, high soil salinity induces water stress by reducing soil osmotic potential [142]. In addition, the absorbed Na+ and Cl− ions increase sap osmotic pressure, affecting water availability within leaf tissues [132]. This reduction in tissue water content leads to stomatal closure, a hallmark response to water stress in plants [11]. Stomatal closure in S. viridis under salt stress is associated with reduced CO2 assimilation rates [139,145]. Ref. [145] noticed that S. viridis exposed to 100 mM NaCl failed to recover from the stress under elevated CO2 conditions, highlighting the severe osmotic impact on carbon assimilation.

Given its detrimental effects on water balance and carbon assimilation, salinity also impairs photosynthesis. Abiotic stresses typically reduce photosynthetic efficiency by disrupting gas exchange, pigment biosynthesis, and the electron transport chain [11]. Chlorophyll fluorescence, a key indicator of photosynthetic performance [146], shows significant declines in PSII activity under salt stress. For instance, S. viridis exhibits reductions in photosynthetic rate (A) ranging from 30% (96 h under 100 mM NaCl) to 60% (200 mM NaCl) [65]. Similarly, declines in ϕPSII, Fv/Fm, and Fm are often accompanied by increases in initial fluorescence (Fo) and NPQ under salt stress [139,145].

Ref. [145] have also investigated the electron transport chain dynamics of S. viridis under salt stress, and provided evidence of photoinhibitory damage in PSII, even at low salt concentrations (50 mM NaCl). Under more severe and prolonged stress, a higher proportion of oxidized PSI reaction centers (P700) was reported, along with increased amounts of active P700. This finding suggests a possible mechanism to cope with adverse environmental conditions by maintaining PSI activity [145]. However, this photoinhibitory damage led to a notable reduction in the electron transport chain conductance, reflecting an overall decline in photosynthetic efficiency under high salinity stress [145].

In addition to structural damage, salt stress exacerbates the production of ROS, which are a common byproduct of abiotic stresses, including salinity [11]. In a separate study, [147] demonstrated that moderate salt stress (50 mM NaCl) promoted ROS accumulation in S. viridis due to the reduction in molecular oxygen within the chloroplasts.

Salt stress also induces significant alterations to chloroplast ultrastructure in S. viridis. Ref. [145] reported that even moderate salt stress led to deformation of bundle sheath cells, where chloroplasts became compressed and elongated due to the expansion of vacuoles. Moreover, the appearance of blank spaces within bundle sheath cells suggested intracellular salt deposition. Inside the chloroplasts, salt stress caused starch grains to increase in size and number while simultaneously reducing the number of thylakoid membranes [145]. Ref. [144] further documented a reduction in chloroplast numbers under severe salt stress conditions, emphasizing the profound structural impact of salinity on chloroplasts.

Abiotic stress, such as salt stress, threatens plant survival by disrupting cellular homeostasis, and to counter these adverse conditions, plants use multiple defense mechanisms, including phytohormone regulation [148]. Phytohormones, particularly ABA, play a central role in coordinating stress responses, including the activation of stress-responsive genes and the regulation of stomatal guard cells to maintain water balance [65,148]. Despite its importance, studies investigating the roles of phytohormones in S. viridis and S. italica under salt stress remain scarce, representing a significant gap in current knowledge.

Ref. [65] explored ABA signaling pathways in S. viridis under various stress conditions, including salinity. Their findings revealed that ABA levels increased in leaves of the accessions A10.1 and Ast-1 following salt stress treatments. Notably, Ast-1 plants exhibited a two-fold increase in ABA levels compared to A10.1 under high salinity. Interestingly, exogenous ABA treatments highlighted differences in sensitivity between the accessions: while carbon assimilation in A10.1 plants was affected by a 100 µM ABA dose, Ast-1 plants required a 200 µM dose for a similar response [65]. These observations led the authors to suggest that A10.1 plants are more sensitive to ABA signaling, which may explain their distinct physiological responses to salt stress.

In addition to phytohormone signaling, plants utilize active mechanisms to mitigate salt stress. Ion homeostasis plays a critical role in this process, as ion channels help expel Na+ and Cl- back into the soil or sequester them into vacuoles to prevent cytoplasmic toxicity, while some species better adapted to saline environments have more specialized mechanisms, such as salt glands on their leaves [132,149]. In S. viridis, [145] demonstrated that vacuole expansion under salt stress can alter chloroplast structure, further underlining the importance of ion compartmentalization in stress responses.

One well-studied mechanism for salt tolerance in S. viridis involves the selective uptake and accumulation of Na+ and K+ by the roots [143,144]. Maintaining a proper Na+/K+ balance is crucial for cellular function and survival under salinity, as K+ is vital for osmotic regulation and proper nutritional homeostasis [150]. Ref. [143] investigated the potential of potassium supplementation to alleviate salt stress in S. viridis. Their results showed that plants treated with 5 mM KCl exhibited improved biomass accumulation and healthier root morphology when exposed to 150 mM NaCl, particularly in accessions A10.1 and ME034V [143].

Complementing these findings, [144] reported that potassium supply mitigates the effects of salinity on photochemical performance. KCl supplementation reduced chlorophyll fluorescence peaks in both untreated and salt-stressed plants. Notably, the performance index derived from chlorophyll fluorescence analysis improved significantly with KCl application [144]. However, KCl had limited effects on antioxidant enzyme activity, except for catalase, which showed increased activity in plants treated with 9 mM KCl. Additionally, electrolyte leakage—a marker of membrane damage associated with oxidative stress—declined following KCl supplementation [144]. These findings suggest that potassium improves stress resilience by stabilizing membrane integrity. Nevertheless, potassium supplementation failed to mitigate the adverse effects of severe salt stress on plant physiology and morphology [144] ), suggesting that potassium-mediated stress tolerance may be most effective under moderate salinity conditions. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underpinning K+ homeostasis and its interplay with other stress mitigation strategies in S. viridis.

Beneath the morphophysiological responses to salt stress are numerous, complex molecular pathways activated in response to salinity. Changes in the transcriptional landscape triggered by abiotic stress often represent adaptive responses, with promising potential for biotechnological applications [67]. So far, most molecular studies have focused on S. italica and revealed that diverse gene families are responsive to salt stress. Ref. [58] investigated the role of lipoxygenases (LOX) in salt stress. Lipoxygenase enzymes play a role in the jasmonate (JA) pathways associated with salt stress, and JA is known to enhance salt tolerance in plants [151,152]. The study found SiLOX2, SiLOX6, SiLOX8, and SiLOX9 upregulated under salt stress, with SiLOX10 and SiLOX11 further upregulated in the salt-tolerant cultivar QH2 [58]. Additionally, MADS-box genes were implicated in salt stress response. Ref. [69] reported significant induction of SiMADS01 and SiMADS51 among 10 genes previously associated with drought and salinity. Similarly, TCP transcription factors—targets of miR319, a known regulator of salt stress response [67,153]—were analyzed by [154]. Of the 22 TCP genes studied, SiTCP2, SiTCP3, SiTCP4, SiTCP5, and SiTCP12 were repressed following salt stress.

Non-specific lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) have also been linked to salt stress tolerance. [155] characterized SiLTP in S. italica, demonstrating its induction during early salt stress followed by a decline with prolonged exposure. LTPs are small peptides able to transfer phospholipids between membranes and that have been reported to participate in vegetative and reproductive development, as well as in pathogen defense and abiotic stress response [155]. Interestingly, when tobacco plants overexpress SiLTP, they show higher germination and survival rates, and higher levels of accumulated proline and soluble sugars [155]. Notably, overexpression of SiLTP in S. italica improved root and shoot growth under 100 mM saline conditions, while RNAi knockdown lines displayed greater sensitivity [155].

The ABA signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in both physiological and molecular responses to salt stress [67]. Ref. [66] reported changes in the expression of ABA-responsive SnRKs and PP2Cs in S. viridis following 48 h of salt stress, with PP2Cs being particularly responsive. Notable genes such as SnRK2.1, SnRK2.9, PP2C6, PP2C8, and PP2C7.1 were highly expressed in A10.1 plants. Interestingly, the Ast-1 accession exhibited significant induction of PYL genes, contrasting with their downregulation in A10.1 genotype [65].

Transcriptome analysis provides valuable insights into global transcriptional changes during salt stress. In the study by [145], salinity stress resulted in over 6000 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in S. viridis, enriched for GO terms related to oxidation-reduction processes, carbohydrate metabolism, and hydrolase activity. Numerous transcription factors (TFs), including MYB, WRKY, ERF, HSF, and HD-ZIP, were prominently involved, with 109 TFs being overregulated and 58 repressed. MYB TFs were particularly abundant among DEGs [145].

Ref. [156] analyzed five families of C4 pathway genes in S. italica: carbonic anhydrase (CaH), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK), NADP-dependent malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and the NADP-dependent malic enzyme (NADP-ME). Among the numerous identified genes, only SiαCaH1 and SiPEPC2 were induced in the salt-tolerant cultivar IC-4, while SiMDH8 was induced in the sensitive cultivar IC-41 [156]. Furthermore, overexpression of SiNADP-ME5 in yeast enhanced salt tolerance, despite its lack of induction under salinity in plants [156]. Ref. [145] examined gene expression related to the C4 pathway, photorespiration, and oxidative stress responses in S. viridis compared to the halophyte Spartina alterniflora. Significant upregulation of PEP-CK1 and CAT2 occurred in S. viridis, along with genes encoding peroxidase superfamily protein and flavonol synthase/flavonone 3-hydroxylase. Conversely, genes related to oxidation-reduction processes such as ATLOX2, ACSF, CZSOD2, PORA, FAD8, and GAPB were strongly downregulated. Interestingly, the halophyte was much more stable in its transcript analysis in contrast to S. viridis, emphasizing the susceptibility of S. viridis to salt stress [145].

In a complementary study, [157] explored the transcriptional landscape of two S. italica cultivars (salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive) during seed germination. The tolerant cultivar exhibited 362 DEGs during seed imbibition (IM) and 1520 DEGs during radicle protrusion (RAP), whereas the sensitive cultivar showed 828 DEGs during IM and 3040 DEGs during RAP. Several transcription factors belonging to the ERF, bHLH, MYB, HD-ZIP and bZIP families are also responsive to salt stress [157]. DEGs were associated with ABA and gibberellic acid signaling, auxin and brassinosteroid biosynthesis, primary metabolism, and energy production, underscoring the critical role of metabolic activity during germination under stress. Genes related to photosynthesis, chloroplast development, and cell wall modification were upregulated, suggesting anticipatory autotrophic growth as a stress tolerance strategy [157]. Functional validation of two candidate genes, SiDRM2 and SiKOR1, involved in hormonal regulation and associated with cell wall modification, respectively, revealed opposing effects: SiDRM2 overexpression in Arabidopsis enhanced germination under salinity stress, while SiKOR1 overexpression reduced germination, highlighting their regulatory roles in hormonal signaling and cell wall dynamics [157].

Similarly, [140] examined 104 S. italica accessions under salt stress and compared two representative genotypes: FM6 (tolerant) and FM90 (sensitive). The FM90 accession exhibited more extensive gene repression (1100 DEGs) and induction (800 DEGs) compared to the FM6 accession (345 repressed, 391 induced) [140]. Transcription factors such as AP2/ERF, HSF and WRKY were repressed in the sensitive genotype, while GATA genes were mostly induced. The tolerant cultivar showed significant induction of NAC TFs, which have been associated with stress resilience [140]. GO enrichment analysis revealed significant downregulation of photosynthesis-related genes in the sensitive genotype, suggesting impaired energy metabolism, whereas the tolerant accession maintained stability in photosynthetic pathways and displayed enrichment for ion transport processes [140]. Protein–protein interaction networks highlighted repressed ribosomal proteins as central hubs in the sensitive genotype, which the authors associated with slowing growth as a survival [140]. In contrast sugar metabolism hub genes dominated the tolerant genotype network, suggesting alternative energy production pathways to mitigate stress [140], similar to the observations on autotrophic growth made by [157].

6. Nutrient Deficiency

Plant mineral nutrition is a complex and multifaceted topic. Essential nutrients are classified as macro or micronutrients based on their required quantities and play critical roles in plant physiology [158] (Figure 3). Nutrient deficiencies can lead to drastic outcomes, compromising plant growth and yield. Despite the importance of mineral nutrition, responsesthe response of Setaria species to different types of nutritional stress remains underexplored. Existing studies primarily focus on nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium deficiencies, particularly in S. italica, which is known for its tolerance to low-fertility conditions [159,160].

6.1. Nitrogen Deficiency

Nitrogen (N) is indispensable for plant life, as it forms the basis of proteins, nucleic acids, vitamins, and other essential biomolecules [158]. Plants primarily absorb nitrogen in the form of nitrate, with ammonium as an alternative source [161]. Nitrogen deficiency manifests in diverse ways, including leaf chlorosis, necrosis, growth inhibition, reduced photosynthetic pigment levels, and a decline in amino acids and protein content [158]. In S. viridis and S. italica, nitrogen starvation causes fewer leaves to develop and leaf discoloration due to reduced chlorophyll and carotenoid levels [138,162]. Shoot and root growth are reduced, as well as shoot dry weight [160,162]. Root architecture changes in response to low nitrogen, developing shorter and less numerous lateral and crown roots [160]. Additionally, nitrogen stress compromises reproductive output, leading to pale, thin panicles and reduced seed production in S. viridis [138,163]. The nutritional quality of seeds is also affected, as seen in decreased folate content under nitrogen starvation in S. italica [163].

In addition to the morphological changes, S. italica suffers a significant drop in nitrogen content in both shoots [162] and roots [160]. The decrease in nitrogen content in roots is much sharper than in the shoot, indicating some degree of N mobilization to the shoot in response to low nitrogen [160]. Nitrogen starvation also triggers metabolic shifts: soluble proteins increase in roots while total amino acids decline, whereas both parameters drop in shoots [160,162]. Moreover, enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism are differentially regulated; for example, glutamate synthase (GOGAT) activity increases, whereas glutamine synthetase (GS), nitrate reductase, and nitrite reductase activities are inhibited [162]. These changes indicate how nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) shifts in S. italica under low nitrogen stress. Ref. [160] have reported a threefold increase in NUE in the shoot, while roots displayed a twofold increase, suggesting the N mobilization to the shoot might be a strategy to cope with low nitrogen and supply the photosynthetic demand.

At the molecular level, nitrogen starvation downregulated chloroplast-related genes, including SiPEPC, which is critical for carbon assimilation during photosynthesis [162]. Genes involved in nitrogen transport and assimilation also exhibit dynamic responses. For instance, SiNRT1.11 and SiNRT1.12 are upregulated in shoots, while SiNRT1.1, SiNRT2.1, SiNAR2.1, and SiAMT1.1 are induced in roots, enhancing nitrate and ammonium uptake and mobilization [160].

Comprehensive analyses of the NITRATE TRANSPORTER 1/PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER (NPF) family in S. italica have revealed its critical role in nitrogen transport during stress. Most NPF genes are induced under low nitrogen, particularly in shoots, with expression levels increasing over time [159]. Curiously, both S. italica and S. viridis have tandem duplications of NRT1.1B, unlike other crops, such as rice and sorghum. Moreover, both copies are highly expressed in vegetative tissues [159]. These findings suggest this duplication event might have played a role in the higher tolerance of Setaria species to low fertility. The nitrate-transporting ability of SiNRT1.1 was confirmed by generating transgenic Arabidopsis, complementing the nrt1.1 mutant phenotype. Furthermore, a chlorate sensitivity assay [141] showed that transgenic plants had better nitrate absorption rates than wild type [159]. These results combined provide further evidence for the role of SiNRT1.1 in low nitrogen tolerance.