Advancing Archaeobotanical Methods: Morphometry, Bayesian Analysis and AMS Dating of Rose Prickles from Monteagudo Almunia, Spain (12th Century–Present)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Roses in the Archaeobotanical Register

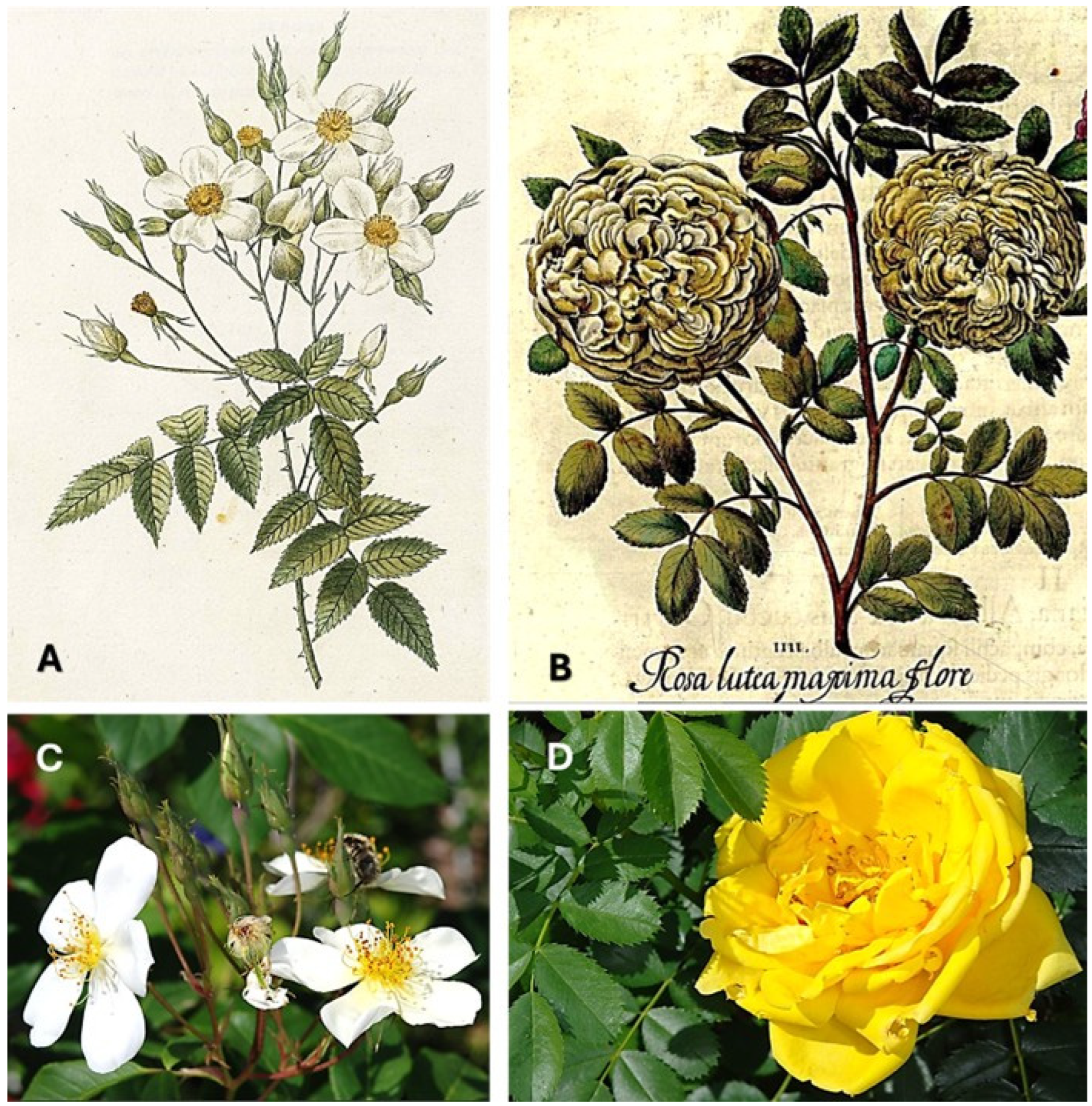

1.2. Background on the Rose Diversity

1.2.1. Rose Diversity and the Role of Hybridization

1.2.2. Roses in Classical Antiquity and Middle Ages of Europe

1.2.3. The Chinese Roses Revolution and Modern Roses

1.2.4. Evidence for Modern Wild and Cultivated Rose Diversity in the Context of Monteagudo (Murcia) and Neighboring Areas

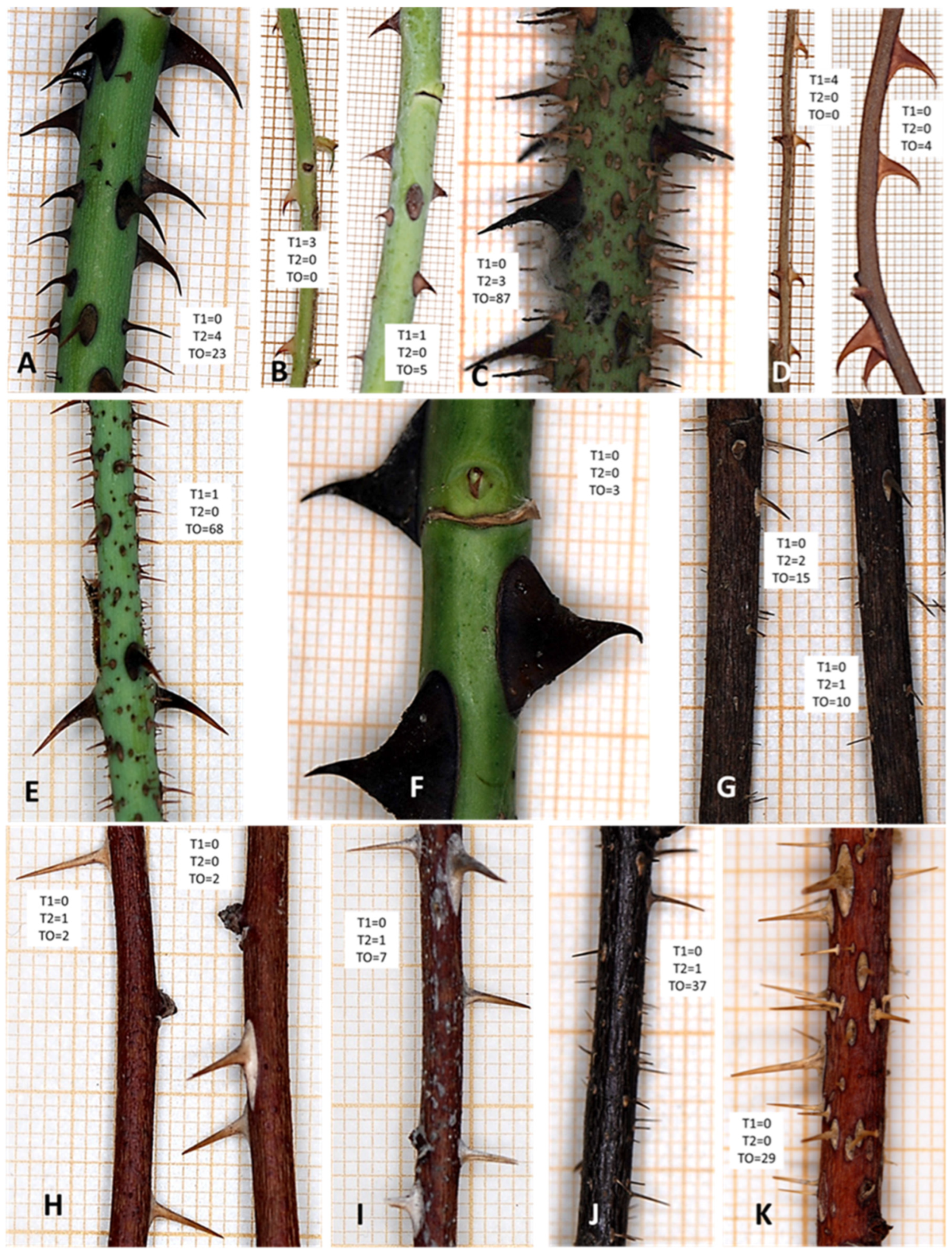

1.3. Rose Prickles Diversity

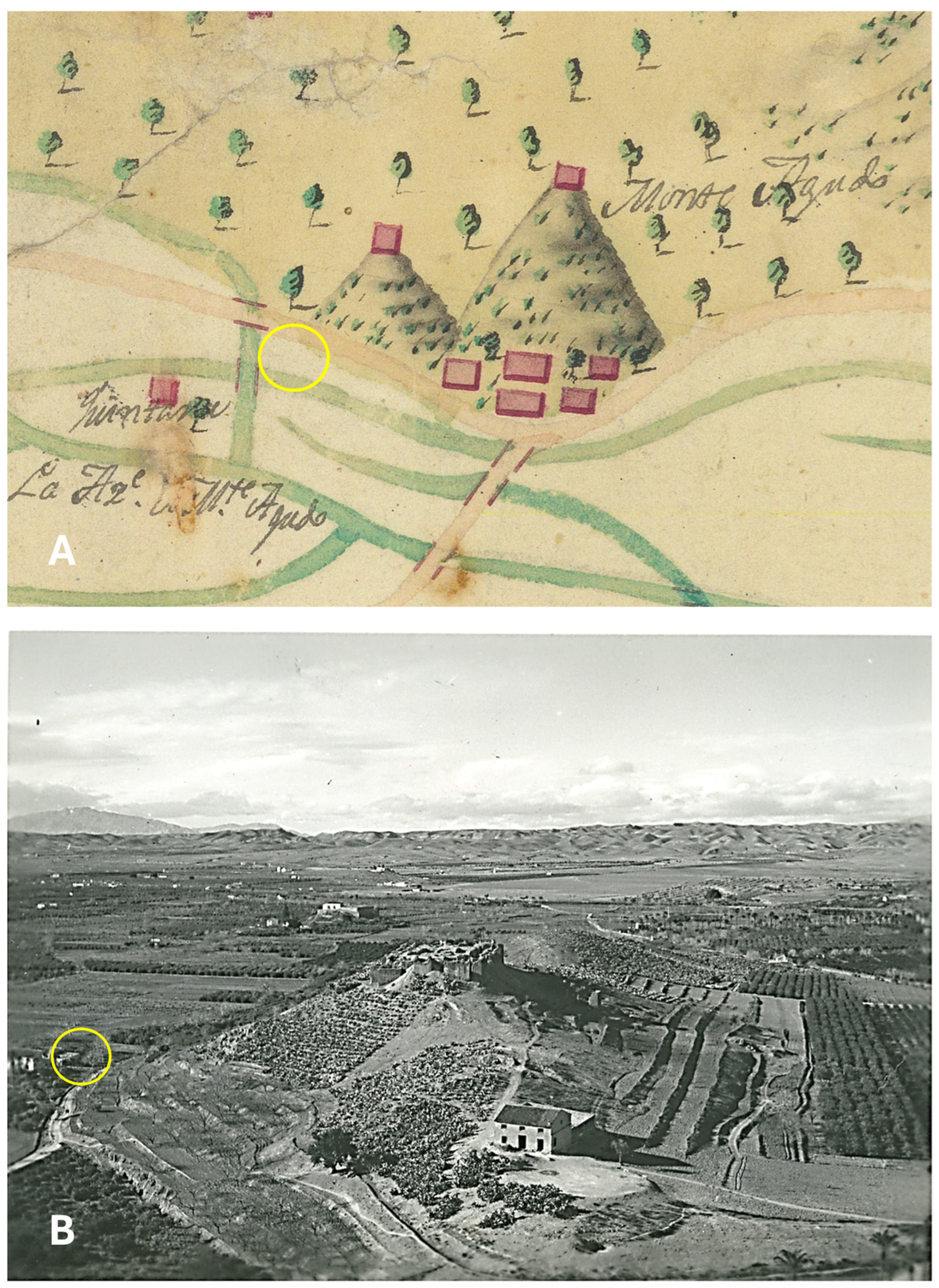

1.4. Background on the Almunia of Montagudo and Its Historical Significance

1.5. Hypothesis and Objectives of the Study

2. Results

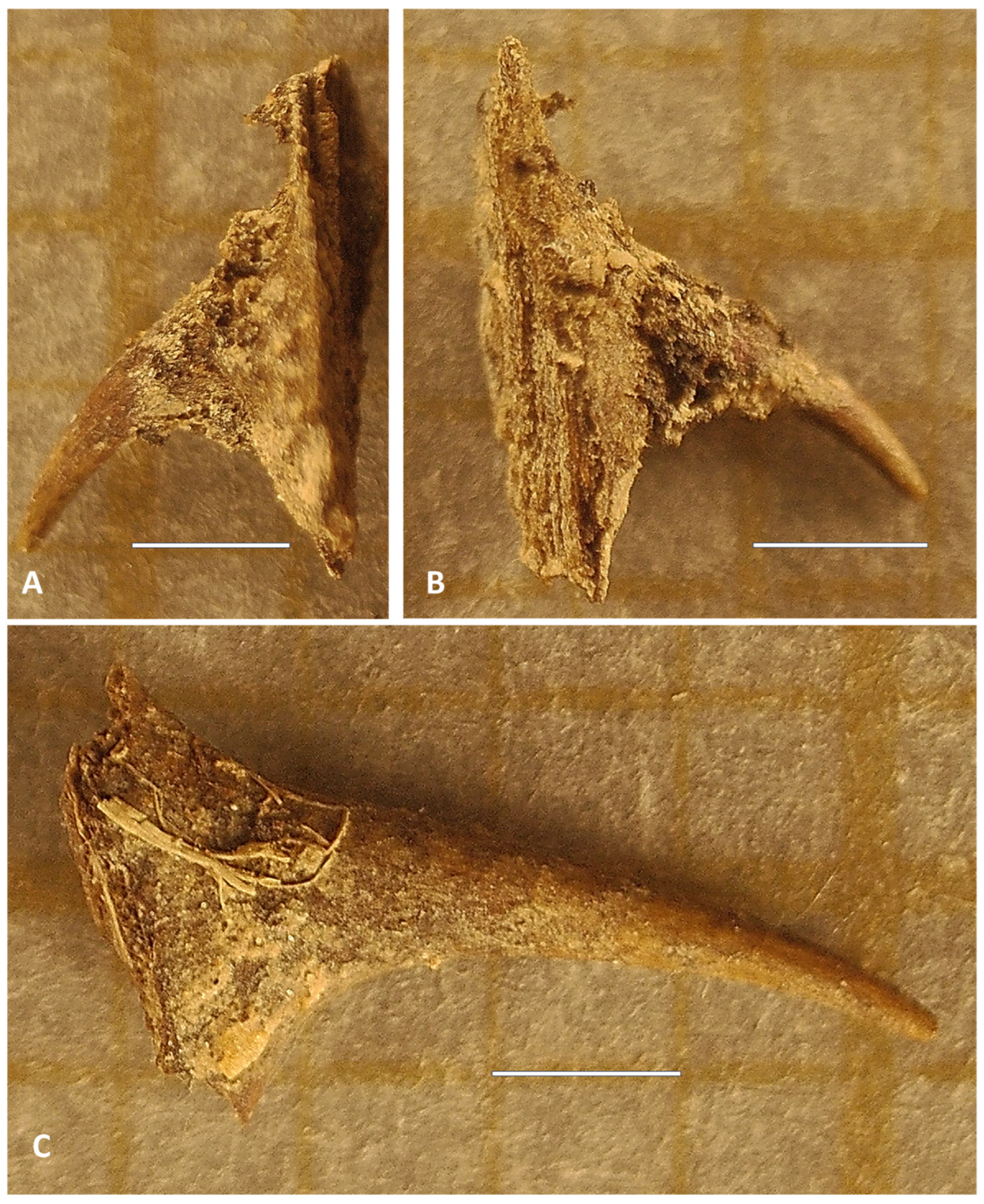

Description of the Findings, Including the Condition and Distribution of the Rose Prickles

3. Discussion

3.1. Interpretation of the Results in the Context of Medieval Garden Practices

3.2. Possible Implications for Understanding the Use and Significance of Roses in Medieval Muslim Gardens

3.3. Limitations of the Study and Potential Avenues for Further Research

4. Materials and Methods

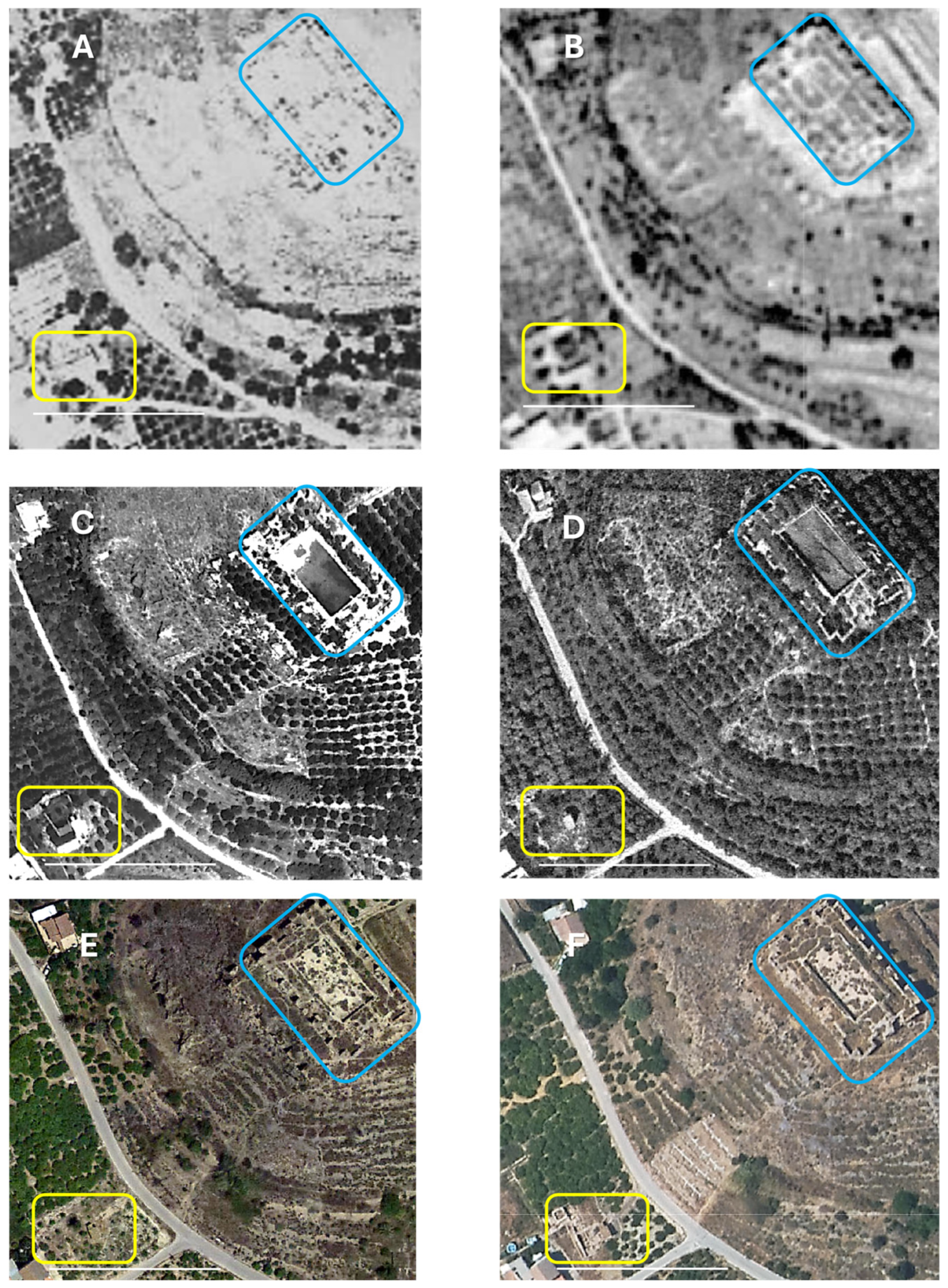

4.1. Description of the Site and Its Location

4.2. Excavation Methods

4.3. Radiocarbon Dating

4.4. Identification Process of the Rose Prickles

4.5. Bayesian Hypothesis Testing: Explanation of the Approach and Its Application

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMS | Accelerator Mass Spectrometry |

| GP | Glandular prickles |

| MRH | Medieval Rose Heritage |

| NGP | Non-glandular prickles |

| UPOV | International Union for The Protection of New Varieties of Plants |

| WIMRH | Western Islamic Medieval Rose Heritage |

References

- Ciarallo, A. Verde Pompeiano; “L’Erma” di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarallo, A. Flora Pompeiana; “L’Erma” di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarallo, A.; Mariotti-Lippi, M. The Garden of ‘Casa dei Casti Amanti’ (Pompeii, Italy). Gard. Hist. 1993, 21, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPVO. Protocol for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability Tests Rosa L. Rose UPOV Species Code: ROSAA. 2009. Available online: https://cpvo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/rosa_2_rev.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- GOV.UK. United Kingdom Plant Breeders Rights Technical Protocol for the Official Examination of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability (DUS) Rose (Rosa L.). 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a809131ed915d74e622f326/dus-protocol-rose.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- UPOV. Rose, UPOV Code: ROSAA, Rosa L., Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability; International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.upov.int/edocs/tgdocs/en/tg011.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Younis, A.; Riaz, A.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Pervez, M.A. Extraction and Identification of Chemical Constituents of the Essential Oil of Rosa Species. Acta Hortic. 2008, 766, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Romero, M.D.; Espín, A.; Trujillo, I.; Torres, A.M.; Millán, T.; Cabrera, A. Cytological and Molecular Characterisation of a Collection of Wild and Cultivated Roses. Floric. Ornam. Biotechnol. 2009, 3, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A.V.; Gladis, T.; Brumme, H. DNA Amounts of Roses (Rosa L.) and Their Use in Attributing Ploidy Levels. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, K.; Kovacheva, N.; Rusanova, M.; Atanassov, I. Flower Phenotype Variation, Essential Oil Variation and Genetic Diversity among Rosa alba L. Accessions Used for Rose Oil Production in Bulgaria. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 161, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawula, C. Rosa gallica L. and Other Gallic Roses: Origin(s) and Role in the Genesis of Cultivated Roses. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Angers, Angers, France, 2023. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04584802v1 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Martin, M.; Piola, F.; Chessel, D.; Jay, M.; Heizmann, P. The Domestication Process of the Modern Rose: Genetic Structure and Allelic Composition of the Rose Complex. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widrlechner, M.P. History and Utilization of Rosa damascena. Econ. Bot. 1981, 35, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, M.; Zamani, Z.; Khalighi, A.; Fatahi, R.; Byrne, D.H. Wide Genetic Diversity of Rosa damascena Mill. Germplasm in Iran as Revealed by RAPD Analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 115, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiei, L.; Naderi, R.; Khalighi, A.; Bushehri, A.A.; Mozaffarian, V.; Esselink, D.; Smulders, M.J.M. In Search of Genetic Diversity in Rosa foetida Hermann in Iran. Acta Hortic. 2009, 836, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beales, P. Roses: An Illustrated Encyclopaedia and Grower’s Handbook of Species Roses, Old Roses and Modern Roses, Shrub Roses and Climbers; Harvill: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.; Rix, M. The Quest for the Rose; BBC Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Akef, W.; Almela, I. Nueva lectura del capítulo 157 del tratado agrícola de Ibn Luyūn. Al-Qanṭara 2021, 42, e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito-Rojo, J.; Casares-Porcel, M. El Jardín Hispanomusulmán: Los Jardines de al-Andalus y su Herencia; Editorial Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Banqueri, J.A. Libro de Agricultura. Su Autor el Doctor Excelente Abu Zacaria Iahia Aben Mohamed ben Ahmed en el Awam Sevillano; Imprenta Real: Madrid, Spain, 1802; Available online: https://archive.org/details/b30457282_0001/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Clément-Mullet, J. Le Livre d’Agriculture d’Ibn al Awam; Albert L. Hérold: Paris, France, 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J.H. Gardening Books and Plant Lists of Moorish Spain. Gard. Hist. 1975, 3, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.H. Plants of Moorish Spain: A Fresh Look. Gard. Hist. 1992, 20, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bermejo, J.E.; García-Sánchez, E. Ibn al-ʽAwwām, Kitāb al-Filāḥa. Libro de agricultura, ed. y trad. Josef Antonio Banqueri, 2 vols., Madrid, 1802 (ed. facsimil); Ministerio de Agricultura: Madrid, Spain, 1988; pp. 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, E.; Carabaza, J.M.; Hernández-Bermejo, J.E. Flora Agrícola y Forestal de al-Andalus; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Navarro, J.; Camarero, I.; Valera, J.; Rivera-Obón, D.J.; Obón, C. Persistence and Heritage from Medieval Bustān Gardens: Roses in Ancient Western Islamic Contexts and Abandoned Rural Gardens of Spain. Heritage 2025, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charco, J.; Alcaraz, F.; Carrillo, F.; Rivera, D. Árboles y Arbustos Autóctonos de la Región de Murcia; Centro de Investigaciones Ambientales del Mediterráneo: Murcia, Spain, 2015; pp. 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.; Guerra, J.; Coy, E.; Hernández, A.; Fernández, S.; Carrillo, A. Flora de Murcia; Diego Marín: Murcia, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz, F. Flora y Vegetación del NE de Murcia; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Chueca, F. Vegetación y Flora de las Regiones Central y Meridional de la Provincia de Murcia; Centro de Edafología y Biología Aplicada del Segura: Murcia, Spain, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Willkomm, M. Supplementum Prodromi Florae Hispanicae sive Enumeratio et Descriptio Omnium Plantarum inde ab anno 1862 Usque ad Annum 1893 in Hispania Detectarum quae Innotuerunt Auctori, Adjectis Locis Novis Specierum jam Notarum; E. Schweizerbart (E. Koch): Stuttgart, Germany, 1893; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Rouy, G. Excursions Botaniques en Espagne en 1881 et 1882, Orihuela, Murcia, Velez-Rubio, Hellín, Madrid, Irún; Typographie et Lithographie Boehm et Fils: Montpellier, France, 1883; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Rouy, G. Excursions Botaniques en Espagne en 1881 et 1882, Orihuela, Murcia, Velez-Rubio, Hellín, Madrid, Irún. Rev. Des Sci. Nat. 1883, 2, 228–256. [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Laliga, L. Estudio Crítico de la Flora Vascular de la Provincia de Alicante: Aspectos Nomenclaturales, Biogeográficos y de Conservación; Ruizia Monografías del Real Jardín Botánico. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Tomo 19: Madrid, Spain, 2007; p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, G.; Serra-Laliga, L.; Pedauyé, H. Flora Silvestre del Término Municipal de Orihuela (Alicante); Ayuntamiento de Orihuela: Orihuela, Spain, 2019; Volume 2, p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Codorníu y Stárico, R. Guía del parque de Ruiz-Hidalgo en Murcia; Imprenta Alemana: Madrid, Spain, 1915; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- García, M. Historia de Las Rosas Verdes de Santomera: Don Antonio Murcia y García. Available online: https://manuelgarciasanchez83.wordpress.com/2018/02/06/historia-de-las-rosas-verdes-de-santomera-don-antonio-murcia-y-garcia/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, M.; Li, R.; Huang, J.; Cheng, W.; Shi, C.; Zhang, W. Morphology, Structure and Development of Glandular Prickles in the Genus Rosa. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Simonneau, F.; Thouroude, T.; Oyant, L.H.S.; Foucher, F. Morphological Studies of Rose Prickles Provide New Insights. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.N.; Jeauffre, J.; Thouroude, T.; Chameau, J.; Simoneau, F.; Hibrand-Saint Oyant, L.; Foucher, F. Genetics and Genomics of Prickle in Roses. In Proceedings of the XXXI International Horticultural Congress (IHC2022): International Symposium on Innovations in Ornamentals: From Breeding to Market, Angers, France, 14–20 August 2022; pp. 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Rawandoozi, Z.J.; Barocco, A.; Rawandoozi, M.Y.; Klein, P.E.; Byrne, D.H.; Riera-Lizarazu, O. Genetic Dissection of Stem and Leaf Rachis Prickles in Diploid Rose Using a Pedigree-Based QTL Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1356750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, W.; Shi, C.; Bao, M.; Zhang, W. Nonglandular Prickle Formation Is Associated with Development and Secondary Metabolism-Related Genes in Rosa multiflora. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Yan, P.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, W.; Feng, H.; Hou, W. PE (Prickly Eggplant) Encoding a Cytokinin-Activating Enzyme Responsible for the Formation of Prickles in Eggplant. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, K.; Majumder, J.; Mahanta, M.; Mitra, M.; Gantait, S. Genetic Diversity Analysis and Molecular Characterization of Tropical Rose (Rosa spp.) Varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 332, 113243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, P.; Gómez-García, D.; Ferrández, J.V.; Bernal, M. Rosas de Aragón y Tierras Vecinas, 2nd ed.; Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología-CSIC: Jaca, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Swarnkar, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Dogra, V.; Kumar, S. Prickle Morphogenesis in Rose Is Coupled with Secondary Metabolite Accumulation and Governed by Canonical MBW Transcriptional Complex. Plant Direct 2021, 5, e00325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiret, J.-L.M. Rosier. In Encyclopédie Méthodique, Botanique; Agasse: Paris, France, 1804; Volume 6, pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, J.; Jiménez-Castillo, P. In Al-Bustān Las Fincas Aristocráticas y la Construcción de los Paisajes Periurbanos de al-Andalus y Sicilia Estudios Preliminares; Navarro-Palazón, J., Ed.; La almunia del Castillejo de Monteagudo (Murcia) y su complejo palatino del llano. Laboratorio de Arqueología Arquitectura de la Ciudad (LAAC), Escuela de Estudios Árabes—CSIC: Granada, Spain, 2022; pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Confederación Hidrográfica del Segura. Básico, Galería de Mapas Base. 2025. Available online: https://www.chsegura.es/portalchsic/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=893ec33b6ba84fc09102663dce94b740&codif=&nombre=Basico (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Nisard, D. Les Agronomes Latins Caton, Varron, Columelle, Palladius; J.-J. Dubochet: Paris, France, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E.; Heffner, E. Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella on Agriculture. Res Rustica V–IX; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock, J. Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. 2024. Available online: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D21 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Desfontaines, R. Flora Atlantica; Desgranges: Paris, France, 1798; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Redouté, P.J.; Thory, C.A. Les Roses; Dufart: Paris, France, 1828; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Besler, B. Hortus Eystettensis; Bessler himself: Eichstätt, Germany, 1613; Volume 1, Available online: https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/records/item/10908-hortus-eystettensis-vol-1 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Matilla, G.; Rivera, D.; Obón, C. In Tell Qara Quzaq—II. Campañas IV–VI (1992–1994); Del Olmo Lete, G., Fenollós, J.-L.M., Pereiro, C.V., Eds.; Estudio Paleoetnobotánico de Tell Qara Qüzáq—II Las Plantas Sinantrópicas. Ausa: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; pp. 403–453. [Google Scholar]

- Stuiver, M.; Reimer, P.J. Extended 14C Data Base and Revised CALIB 3.0 14C Age Calibration Program. Radiocarbon 1993, 35, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuiver, M.; Reimer, P.J.; Reimer, R. CALIB Radiocarbon Calibration. Execute Version 8.2html. Available online: http://calib.org/calib/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Bronk-Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk-Ramsey, C. OxCal 4.4. Available online: https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/oxcal/OxCal.html# (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ríos, S.; Alcaraz, F.; Cano, F. Flora de las Riberas y Zonas Húmedas de la Cuenca del río Segura; Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anthos. Anthos, Sistema de Información Sobre las Plantas de España. 2025. Available online: http://www.anthos.es/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- De Carolis, E.; Lagi, A.; Di Pasquale, G.; D’Auria, A.; Avvisati, C. The Ancient Rose of Pompeii; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, J.; Matilla-Seiquer, G.; Obón, C.; Alcaraz, F.; Rivera, D. Grapevine in the Ancient Upper Euphrates: Horticultural Implications of a Bayesian Morphometric Study of Archaeological Seeds. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, J.; Rivera, D.; Matilla-Séiquer, G.; Rivera-Obón, D.J.; Ocete, C.A.; Ocete, R.; Obón, C. Insights into Medieval Grape Cultivation in Al-Andalus: Morphometric, Domestication, and Multivariate Analysis of Vitis vinifera Seed Types. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Martínez-Rico, M.; Morales, J.; Alcaraz, F.; Valera, J.; Johnson, D.; Obón, C. Bayesian Morphometric Analysis for Archaeological Seed Identification: Phoenix (Arecaceae) Palms from the Canary Islands (Spain). Seeds 2025, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Abellán, J.; Palazón, J.A.; Obón, C.; Alcaraz, F.; Carreño, E.; Johnson, D. Modelling Ancient Areas for Date Palms (Phoenix Species: Arecaceae): Bayesian Analysis of Biological and Cultural Evidence. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 193, 228–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Likely Species | Flower Type | Characteristics | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| R. bicolor Jacq. | Purple & yellow | Roses yellow on the outside and blue (Purple) inside | Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. × centifolia L. | Red | Double red roses | Ibn Baṣṣāl and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. gallica L. | Red | Bright red roses | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī |

| R. pulverulenta M.Bieb. (syn. R. sicula Tratt.) | Red | Magian roses with five petals, red, found in the East and al-Sham | Al-Ṭighnarī and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. × alba L. or a white R. × centifolia | White | Intensely white or camphorated roses with more than a hundred petals | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī, Ibn Baṣṣāl, and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. moschata Herrm. | White | Chinese roses (Ward al-ṣīnī) | Ibn Luyūn, Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. sempervirens L. | White | White orchard rose bush, smaller with narrower leaves and smaller flowers | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī |

| Rosa × alba L. | White | White roses from the land of the Slavs and Persia | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī |

| R. × damascena Herrm. | White & red | Double roses of superior quality, white with red tinges | Abū’l-Jayr Ishbīlī, Ibn Baṣṣāl, Al-Ṭighnarī, and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. canina L., and other species | Wild | Wild mountain roses | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī |

| R. canina L. | Wild | Wild roses (Nisrin), onto which cultivated roses are grafted | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī |

| R. lutea var. persiana Lem. and/or R. foetida Herrm. | Yellow | Yellow roses from Alexandria | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī, Al-Ṭighnarī, and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| R. rapinii Boiss. & Balansa or R. hemisphaerica Herrm. | Yellow | Roses the color of yellow daffodils | Ibn Baṣṣāl and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| Artificial (Ibn al-ʽAwwām) | Blue | Blue roses in various shades | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī, Al-Ṭighnarī, and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| Unknown | Wild | Wild white mountain roses | Al-Ṭighnarī |

| Unknown | Wild | Wild white to red mountain roses, with twenty to thirty petals | Al-Ṭighnarī |

| Unknown | Blue | Dark roses (aswad), the color of violets, from Syria and Lebanon | Abū’l-Jayr al-Ishbīlī, Ibn Baṣṣāl, and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| Unknown | Blue & red | Roses red on the outside and blue inside | Al-Ṭighnarī and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| Unknown | Blue & yellow | Roses with yellow on the inside and blue on the outside, found in Baghdad and Tripoli of al-Sham | Al-Ṭighnarī and Ibn al-ʽAwwām |

| (A) Prior Under Historical and Biogeographical Constraints | (B) Prior Uniform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxa | Prior Probability | p (Taxon Given T1) | p (Taxon Given T2) | Prior Probability | p (Taxon Given T1) | p (Taxon Given T2) |

| R. agrestis Savi | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| R. bicolor Jacq. | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R. canina L. | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| R. foetida Herrm. | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.25 |

| R. gallica L. | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| R. hemisphaerica Herrm. | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| R. lutea var. persiana Lem. | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.44 |

| R. moschata Herrm. | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| R. rubiginosa L. | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| R. sempervirens Savi | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| R. sp. Tea | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R. × alba L. | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| R. × bifera (Poir.) Pers. | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| R. × centifolia L. | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| R. × damascena Herrm. | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Rubus ulmifolius Schott. | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sample Code | Lab. Code | BP Date, Uncertainty | Cal Years BC/AD Date * (1σ Probability Ranges) (Data in % Peak Area) | Cal Years BC/AD Date * (2σ Probability Ranges) (Data in % Peak Area) | Median 2σ Probability (Data in % Peak Area) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UE 22003 | RICH-36708 (015/2019) | 186 ± 26 BP | 1660 AD–1690 AD (12.9%); 1730 AD–1810 AD (37.9%); 1920 AD–1950 AD (17.4%) | 1650 AD–1700 AD (19.6%); 1720 AD–1820 AD (51.1%); 1830 AD–1880 AD (1.0%); 1910 AD–1955 AD (23.8%) | 1720–1820 AD (51.1%) |

| UE 91003 | RICH-36709 (003/2023) | 91 ± 26 BP | 1690 AD–1730 AD (21.8%); 1810 AD–1840 AD (19.8%); 1870 AD–1920 AD (26.5%) | 1690 AD–1730 AD (26.0%); 1800 AD–1930 AD (69.4%) | 1800–1930 AD (69.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera, D.; Navarro, J.; Camarero, I.; Valera, J.; Rivera-Obón, D.-J.; Obón, C. Advancing Archaeobotanical Methods: Morphometry, Bayesian Analysis and AMS Dating of Rose Prickles from Monteagudo Almunia, Spain (12th Century–Present). Plants 2025, 14, 3709. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243709

Rivera D, Navarro J, Camarero I, Valera J, Rivera-Obón D-J, Obón C. Advancing Archaeobotanical Methods: Morphometry, Bayesian Analysis and AMS Dating of Rose Prickles from Monteagudo Almunia, Spain (12th Century–Present). Plants. 2025; 14(24):3709. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243709

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera, Diego, Julio Navarro, Inmaculada Camarero, Javier Valera, Diego-José Rivera-Obón, and Concepción Obón. 2025. "Advancing Archaeobotanical Methods: Morphometry, Bayesian Analysis and AMS Dating of Rose Prickles from Monteagudo Almunia, Spain (12th Century–Present)" Plants 14, no. 24: 3709. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243709

APA StyleRivera, D., Navarro, J., Camarero, I., Valera, J., Rivera-Obón, D.-J., & Obón, C. (2025). Advancing Archaeobotanical Methods: Morphometry, Bayesian Analysis and AMS Dating of Rose Prickles from Monteagudo Almunia, Spain (12th Century–Present). Plants, 14(24), 3709. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243709