Abstract

Piriformospora indica, a broad-spectrum plant growth-promoting fungus, has been successfully applied in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). In this study, through an integrated transcriptomic and biochemical analyses, we investigated the effects of P. indica colonization on blueberry root growth under long-term tap water (EC ≈ 1500 μs/cm) irrigation. Comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed that P. indica colonization greatly influenced the expression of genes involved in RNA biosynthesis, solute transport, response to external stimuli, phytohormone action, carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall organization, and secondary metabolism pathways. Consistently, the fungal colonization significantly improved the nutrient absorption ability, and increased the contents of sucrose, starch, trehalose, total phenolic, total flavonoids, and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), while suppressing the accumulations of jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), and strigolactone (SL) in blueberry roots. Quantitative real-time PCR verification also confirmed the fungal influences on genes associated with these pathways/parameters, such as auxin homoeostasis-associated WAT1, cell wall metabolism-related EXP, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis-related PAL and CHS, carotenoid degradation-related CCD8, transportation-related CNGC, trehalose metabolism-related TPP, and so on. Our study demonstrated that P. indica improved blueberry adaptability to mild salt stress by synergistically regulating cell wall metabolism, secondary metabolism, stress responses, hormone homeostasis, sugar and mineral element transportation, and so on.

1. Introduction

Piriformospora indica (also named Serendipita indica), an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF)-like fungus [1], is capable of colonizing not only the host plants of AMFs but also Brassicaceae family plants, which AMFs cannot colonize [2]. P. indica can be axenically cultured on a many synthetic and semi-synthetic media [3], making its application much easier than AMF. The growth-promoting effects of P. indica have been confirmed in many of its host plants [4], including both herbaceous plants [5,6,7] and woody plants [8,9,10]. P. indica can also enhance the tolerance of host plants to various stresses, including salinity. Evidence reveals that P. indica colonization can enhance the salt tolerance of host plants by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity [11], reducing oxidative damage [12,13,14], adjusting ion homeostasis and transporter-related genes expression [15,16], and improving nutrient uptake [13].

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) has a shallow and hairless root system [10]. Its water and nutrient absorption ability is weak, particularly under stressful environments. To compensate for this disadvantage, blueberry roots usually form symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi [10]. Recently, several endophytic fungi, such as Penicillium chrysogenum, P. brevicompactum [17], and dark septate endophytes [18,19], have been applied in blueberry, exhibiting significant plant growth-promoting and/or stress tolerance-enhancing effects. It is worth noting that the colonization of P. indica in blueberry roots demonstrated multifaceted benefits. The fungal colonization significantly improved maximum shoot length and total shoot biomass [20], greatly promoted the rooting of cuttings and the growth of cutting seedlings [10], and significantly enhanced drought tolerance [21] and Phytophthora cinnamomi resistance in blueberry plants [20].

Blueberry plants are highly sensitive to soil salinity [22]. Under salt stress, the growth and productivity of blueberry plants are greatly reduced [23]. Recently, many families have grown blueberry plants on patios or balconies and in yards, where tap water is often used for irrigation. However, prolonged irrigation with tap water induces a significant rise in soil electrical conductivity (EC), leading to impaired blueberry plant growth. Given the demonstrated role of P. indica in promoting plant growth under salt stress [11,12,13,14,15,16], this study investigated the effects of P. indica colonization on the root growth of ‘Legacy’ blueberry plants under tap water (EC ≈ 1500 μs/cm) irrigation (18 months). To explore the underlying mechanisms, we conducted comparative transcriptomic analysis of P. indica-colonized (PI) and non-colonized control (CK) blueberry roots. Furthermore, we validated the expression of 15 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in significantly enriched pathways—such as phytohormone signaling, solute transport, cell wall metabolism, stress response, and secondary metabolism—using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). We also determined biochemical parameters closely linked to these pathways, including profiling of carotenoid and the contents of sucrose, starch, trehalose, total phenolics, flavonoids, phytohormones, mineral elements, and so on. This study will be helpful in understanding how P. indica promotes blueberry root development under long-term tap water irrigation conditions.

2. Results

2.1. P. indica Colonization Improved the Root Biomass of Blueberry Plants Under Long-Term Tap Water Irrigation

Three months post P. indica inoculation, PCR analysis was conducted to examine its colonization in blueberry roots. Pitef1 fragments were successfully amplified from roots of all the P. indica-inoculated blueberry plants (Figure S1), demonstrating effective colonization by the fungus. The root fresh weight of the PI group was significantly higher than that of the CK group (Table 1), accounting for 1.39-fold (p < 0.05). Although no significant root dry weight difference was identified between CK and PI, the average root dry weight of PI seedlings was approximately 1.24-fold that of CK plants (p > 0.05). Moreover, the root activity of PI accounted for about 1.41-fold that of CK (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Effects of P. indica colonization on the root development of blueberry plants under long-term tap water irrigation. CK: non-colonized controls; PI: P. indica-colonized blueberry plants. Different lowercase letters in the same line represent significant difference between CK and PI groups.

EC measurements showed that substrate EC reached ≈600, 1200, and 1500 μS/cm after 6, 12, and 18 months of tap water irrigation, respectively. Because EC > 1500 μS/cm is known to impair blueberry root development [24], the 18-month treatment imposed mild salt stress on the blueberry plants. Thus, P. indica colonization promoted root growth under this tap water-induced mild salt stress.

2.2. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

Through RNA-seq, we obtained about 42.81 Gb of high-quality clean data from six blueberry root cDNA libraries (three replicates for both CK and PI groups), with each sample yielding over 6.25 Gb high-quality data and genome mapping ratio ranging from 83.89% to 89.54% against the V. corymbosum cv. Draper v1.0 reference genome (Supplementary Table S1). In total, 101,410 genes, including 95,018 known genes and 6392 novel genes, were identified to be expressed in blueberry root. Among them, 3315 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in PI compared to CK, including 2753 down-regulated and 562 up-regulated genes.

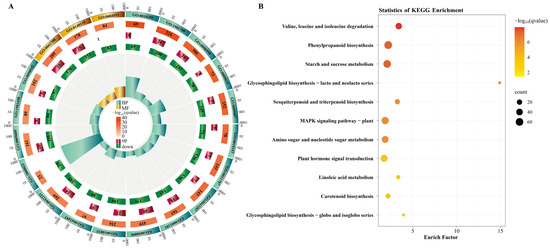

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs showed that they were significantly enriched in 406 biological processes (BPs) terms, 25 cellular components (CCs) terms, and 166 molecular functions (MFs) terms (q < 0.05, Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method) (Supplementary Table S2). Of the top 20 enriched GO terms, several were related to stress responses, including response to stress (GO:0006950, 306 DEGs), response to stimulus (GO:0050896, 419 DEGs), and response to external stimulus (GO:0009605, 161 DEGs) (Figure 1A). This finding suggested that the salt stress responses caused by tap water irrigation in blueberry roots were altered by P. indica colonization.

Figure 1.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs identified between CK and PI blueberry roots. (A) GO enrichment horizontal bar chart for the top 20 enriched terms. Bar colors indicate GO categories: orange for molecular function (MF) and blue for biological process (BP). The numbers in parentheses represent the count of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) annotated to each term. The fill colors of the bars (red or green) reflect the predominant regulation direction of these DEGs: red indicates up-regulation, while green indicates down-regulation. (B) KEGG pathways significantly enriched among DEGs. Larger dots indicate more DEGs.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGGs) enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs between CK and PI were significantly enriched in 11 pathways (q < 0.05, BH method), including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940, 65 DEGs), starch and sucrose metabolism (ko00500, 61 DEGs), MAPK signaling pathway–plant (ko04016, 54 DEGs), plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075, 50 DEGs), amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism (ko00520, 44 DEGs), valine/leucine/isoleucine degradation (ko00280, 37 DEGs), sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis (ko00909, 18 DEGs), carotenoid biosynthesis (ko00906, 16 DEGs), and so on (Figure 1B). These findings indicated that P. indica colonization strongly influenced primary and secondary metabolic and signaling pathways in blueberry roots.

2.3. MapMan Annotation and PageMan Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

Functional annotation of DEGs was further conducted using MapMan v3.6.0. Among the 3315 DEGs, 1443 (43.5%) were classified as ‘unannotated’, while the remaining annotated genes were systematically categorized into 31 level-1 BINs. It is worth noting that most of the annotated DEGs were enriched in enzyme classification (624 DEGs), RNA biosynthesis (365 DEGs), protein modification (200 DEGs), solute transport (193 DEGs), protein homeostasis (160 DEGs), phytohormone action (109 DEGs), and cell wall organization (98 DEGs) BIN pathways (Supplementary Table S3). PageMan (version 3.5.0.) enrichment analysis results showed that these DEGs were significantly enriched in 35 pathways from 11 level-1 BINs, including RNA biosynthesis, solute transport, response to external stimuli, phytohormone actions, carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall organization, multi-process regulation, coenzyme metabolism, protein modification, protein homeostasis, and secondary metabolism (Table 2).

Table 2.

Significantly enriched BIN pathways by the DEGs identified between CK and PI.

Most RNA biosynthesis-related DEGs were transcription factor (TF) genes. Among them, AP2/ERFs (73 DEGs: 6 up-regulated, 67 down-regulated), DREBs (43 DEGs: 3 up-regulated, 40 down-regulated), and WRKYs (41 DEGs: all down-regulated) were the largest top three groups. Additionally, 21 bHLHs, 16 C2H2s, 15 TIFYs (all down-regulated), 9 DOFs (all up-regulated), and 6 PLATZs (all up-regulated) were annotated as RNA biosynthesis-related DEGs (Supplementary Table S4).

Solute transport-related DEGs included 20 P2B-type Ca2+-ATPase genes, 14 phosphate transporter genes, 10 nitrate transporter genes, 7 Ca2+ exchanger genes, 5 K+ transporter genes, 4 AMT family members, 3 MATE family members, 43 ZIP family genes, and so on (Supplementary Table S5). Notably, 43 of the 44 primary active transport-related DEGs and all nine nucleotide sugar transporter (UUAT) genes were down-regulated. In contrast, seven walls are thin 1 (WAT1) gene, two hexose carrier genes (HEX6), two MIP (major intrinsic protein) family transporters, and three cyclic nucleotide-gated channel (CNGC) genes were up-regulated in PI roots. These results suggested that P. indica colonization significantly alters solute transport and nutrient acquisition in blueberry roots.

A total of 91 DEGs (15 up-regulated, 76 down-regulated) were enriched in the external stimuli response category (Supplementary Table S6). Notably, three DEGs encoding the key signaling protein NSP2 (nodulation signaling pathway 2) in the rhizobial symbiosis signaling pathway were up-regulated in PI.

Of the 109 phytohormone action-related DEGs (Supplementary Table S7), 27 were up-regulated and 82 were down-regulated. All ethylene biosynthesis and jasmonic acid (JA) signaling-related DEGs were down-regulated. Five JA conjugation- and degradation-related CYP94Cs genes were down-regulated. However, eight strigolactone-related DEGs, three ABA-related carotenoid cleavage oxygenase 8 (CCD8) genes, and two salicylic acid (SA)-related PR-1 genes were up-regulated in PI.

There were 51 DEGs (4 up-regulated, 47 down-regulated) enriched in the carbohydrate metabolism pathway (Supplementary Table S8). Of them, seven DEGs encoding trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP) were significantly down-regulated in PI.

A total of 98 DEGs (18 up-regulated and 80 down-regulated) were enriched in cell wall organization (Supplementary Table S9). Notably, ten DEGs encoding alpha-class expansin (EXPA) family proteins were all up-regulated in PI.

Among the 48 secondary metabolite biosynthesis-related DEGs, all the 26 terpenoid backbone biosynthesis- and metabolic-related DEGs were down-regulated in PI. However, four DEGs encoding phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), two DEGs encoding chalcone synthase (CHS), and two DEGs encoding 2-hydroxyisoflavone dehydratase (HID) were significantly up-regulated (Supplementary Table S10).

The circadian clock system pathway was significantly enriched by nine DEGs, including seven up-regulated genes encoding time-of-day-dependent transcriptional repressors (PRRs). Of the protein modification-related DEGs, there were 18 genes encoding LRR-XII receptors (15 up-regulated and 3 down-regulated).

2.4. Gene Expression Validation Results of Selected DEGs

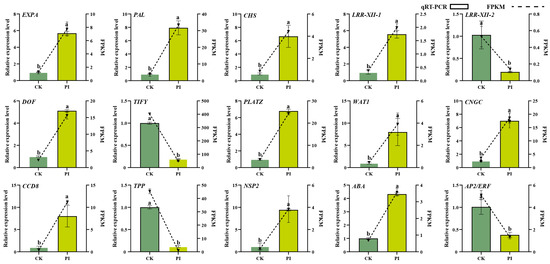

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to validate the expression of fifteen DEGs, including EXPA, PAL, CHS, leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases (LRR-XII-1 and LRR-XII-2), DNA-binding with one finger transcription factor (DOF), TIFY transcription factor family (TIFY), PLATZ transcription factor (PLATZ), WAT1, GNGC, CCD8, trehalose-phosphate phosphatase (TPP), NSP2, abscisic acid biosynthesis enzyme (ABA), and APETALA2/ethylene-responsive factor (AP2/ERF) genes. Results showed that their expression patterns were consistent with the RNA-seq data (Figure 2), indicating the reliability of our transcriptomic data.

Figure 2.

Gene expression validation of 15 selected DEGs. CK: non-colonized control roots; PI: P. indica-colonized blueberry roots. Error bars represent the standard error (SE) of three biological replicates. Different letters (a, b) above the columns indicate significant differences between non-colonized (CK) and P. indica-colonized (PI) groups (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

2.5. Validation of Key Biochemical Parameters Associated with Pathways Significantly Enriched by DEGs

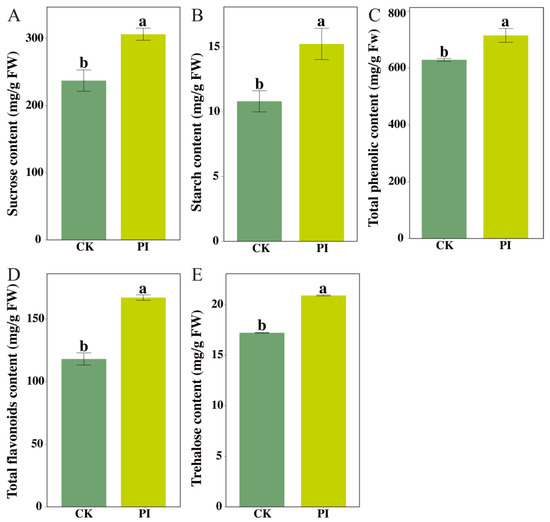

KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the phenylpropanoids biosynthesis pathway (ko00940) and starch and sucrose metabolism pathway (ko00500) were significantly enriched by DEGs. Consistently, PageMan enrichment analysis demonstrated that DEGs were significantly enriched in secondary metabolism (including terpenoid metabolism) and carbohydrate metabolism (particularly trehalose metabolism). To validate these findings, the contents of sucrose, starch, total phenolics, total flavonoids, and trehalose in blueberry roots were measured (Figure 3). P. indica colonization significantly increased sucrose, starch, and total phenolics contents by 29.07%, 40.88%, and 13.63%, respectively. Additionally, the total flavonoids and trehalose contents in PI were also significantly higher than those in CK, being 1.42- and 1.21-fold of it, respectively.

Figure 3.

Influences of P. indica colonization on the accumulations of sucrose (A), starch (B), total phenolic (C), total flavonoids (D), and trehalose (E) in blueberry roots. FW: fresh weight. Different letters (a, b) above the columns indicate significant differences between non-colonized (CK) and P. indica-colonized (PI) groups (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway was significantly enriched by DEGs. Our carotenoid profiling analysis identified a total of 34 carotenoid compounds in blueberry roots, including 5 carotenes and 29 xanthophylls. The total carotene content in PI was approximately 1.23-fold of CK, while its total xanthophylls content accounted for about 97.07% of CK. Seven carotenoid compounds were identified as differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) between CK and PI. Compared to CK, the contents of lycopene, (E/Z)-phytoene, and zeaxanthin in PI significantly increased, while the contents of palmitic acid amaranthin, palmitic acid lutein, zeaxanthin–oleate–palmitate, and palmitic acid β-cryptoxanthin significantly decreased (Supplementary Table S11). Notably, all four down-regulated DAMs belong to xanthophylls.

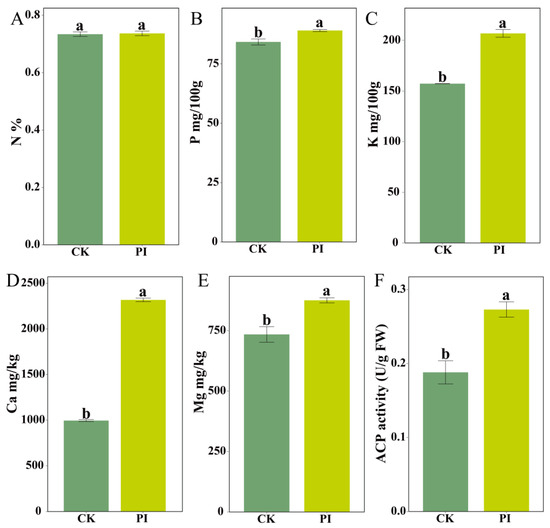

PageMan enrichment analysis showed that the solute transport pathway was significantly enriched by numerous DEGs encoding mineral-element-related transporters. To investigate the effects of P. indica colonization on mineral element homeostasis, we quantified nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg) contents, and acid phosphatase (ACP) activity in blueberry roots. Compared to CK, PI roots exhibited significant increases in K, Ca, P, and Mg contents (p < 0.05), representing approximately 1.32-, 1.13-, 1.06-, 1.19-fold increases, respectively. Moreover, the root ACP activity in PI was 1.46-fold of CK (p < 0.05). These results indicated that P. indica colonization markedly enhanced mineral element acquisition efficiency in blueberry roots (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mineral element contents (A–E) and ACP activity (F) in roots of P. indica-colonized (PI) and non-colonized (CK) blueberry plants. (A–E) Contents for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg), respectively. Different lowercase letters (a, b) above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between CK and PI groups (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

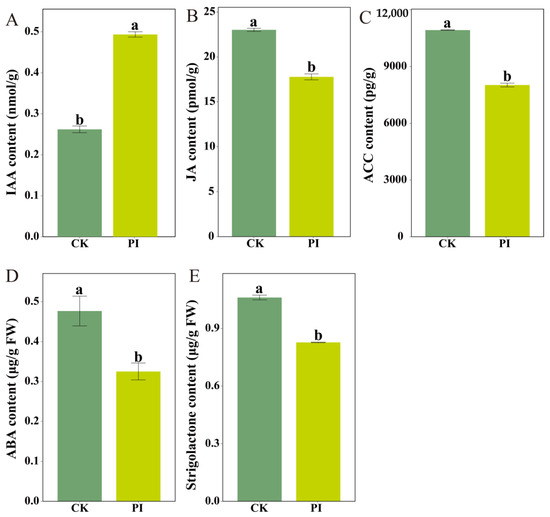

2.6. Determination of Endogenous Phytohormone Contents in CK and PI Blueberry Roots

GO enrichment analysis showed that “jasmonic acid-mediated signaling pathway” term was significantly enriched by DEGs. KEGG enrichment results revealed significant enrichment in the ‘hormone signal transduction’ pathway. PageMan analysis also revealed significant enrichment of JA- and strigolactones (SLs)-related pathways. These findings indicated that P. indica colonization greatly altered phytohormone metabolism in blueberry roots. To verify this, we determined the contents of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), JA, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), abscisic acid (ABA), and SL in CK and PI roots. The IAA content in PI roots was significantly higher than that in CK (p < 0.05), accounting for approximately 1.88-fold of it. Meanwhile, the JA, ACC, ABA, and SL contents were significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in PI roots, accounting for 77.26%, 73.43%, 68.18%, and 54.73% of CK (Figure 5), respectively.

Figure 5.

Influences of P. indica colonization on the accumulations of phytohormones in blueberry roots. (A–E) Contents of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), jasmonic acid, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid content (ACC), abscisic acid content (ABA), and strigolactones (SLs), respectively. FW: fresh weight. Different letters (a, b) indicate significant differences between non-colonized (CK) and P. indica-colonized (PI) groups (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Long-term tap water irrigation can increase soil EC, thereby negatively affecting root system development and plant growth [24]. Our study demonstrated that P. indica colonization significantly improved the root fresh weight and increased the root activity and root dry weight of blueberry plants. These results indicated that fungal colonization promoted blueberry root growth under mild salt stress condition. To further explore the root growth-promoting mechanism of P. indica in blueberry under long-term tap water irrigation, integrated transcriptomic and biochemical analysis was performed. Results revealed that fungal colonization greatly influenced several biological processes in blueberry roots, including symbiotic signaling, RNA biosynthesis, cell wall metabolism, metabolite and mineral element accumulation, stress responses, and sugar transport metabolism.

3.1. P. indica Colonization Modulates the Symbiotic Signaling Pathway and Cell Wall Metabolism in Blueberry Roots

NSP1 and NSP2, members of the GRAS transcription factor family [25], play pivotal roles in symbiotic signaling pathways [26]. NSP2 and bHLH476 function as direct targets of cytokinin signaling and play crucial roles in symbiotic nodulation [27]. Amino acid polymorphisms within the conserved VHIID motif of NSP2 significantly modulate symbiotic signaling and nodule morphogenesis [28]. In Medicago truncatula and Oryza sativa, the nsp1/nsp2 double mutants exhibited significantly reduced colonization rates of AMF [29]. In this study, the significant up-regulation of NSP1 and NSP2 in PI blueberry roots suggested that these genes may act as key regulators at the symbiotic interface, potentially facilitating fungal accommodation through modulation of plant cell wall remodeling or nutrient exchange pathways.

Accumulating evidence indicates that α-expansin plays a pivotal role in plant developmental processes [30], mediating cell wall extension [31,32,33], thereby promoting cell expansion [34,35]. In Arabidopsis, AtEXPA7 and AtEXPA18 are specifically expressed in root hairs, and their overexpression promotes root hair initiation and enhances root growth [36]. AtEXPA17 overexpression enhanced lateral root formation, whereas its knockdown reduced this developmental process [37]. The overexpression of OsEXPA7 in rice not only modulated the expression of OsJAZs in the JA pathway and BZR1/GE in the brassinosteroid signaling pathway [38], but also significantly reduced sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) accumulation in both leaves and roots [39]. OsEXPA17 is specifically expressed in rice root hairs, and its mutation significantly impairs root hair elongation [40]. In our study, the significantly higher expression levels of ten α-expansin genes in PI roots suggested that P. indica promotes root growth and improves root architecture through enhancing the α-expansin-mediated cell wall extension.

3.2. P. indica Colonization Promotes Blueberry Root Development Through Modulating Carotenoid and Phytohormone Metabolism, Improving Secondary Metabolism, and Strengthening Stress Responses

Phytohormones play pivotal roles in regulating root development and plant growth [41,42]. In this study, P. indica colonization significantly increased the IAA content and up-regulated the expression of seven WAT1 genes in blueberry roots. WAT1 is a member of the MtN21 family [43,44], which is primarily associated with amino acid and auxin transport [45]. These results suggested that P. indica colonization may activate auxin transport through up-regulating WAT1 expression, thereby promoting IAA accumulation and ultimately improving the development of blueberry roots.

P. indica colonization significantly decreased the JA and ACC contents in blueberry roots, which was consistent with our previous findings in blueberry cuttings [10]. Moreover, our study found that all ethylene biosynthesis- and JA signaling-related DEGs were down-regulated in PI roots. These suggested that fungal colonization promotes root development by suppressing the biosynthesis of JA and ethylene [11].

Carotenoid-derived metabolites play a pivotal role in mediating signaling crosstalk and facilitating symbiotic association establishment with AMF [46]. The present study revealed that carotenoid degradation-related CCD8 genes were significantly up-regulated in PI roots, suggesting that P. indica colonization exacerbated carotenoid catabolism. Carotenoids serve as precursors for the phytohormones SLs and ABA, both of which are key regulators of root growth and development [47,48]. Our study showed that the SL and ABA contents in PI blueberry roots significantly decreases. In rice, ethylene induces the expression of MHZ5 and the biosynthesis of neoxanthin (a precursor of ABA), which collectively suppress root growth in seedlings [49]. SLs, a class of sesquiterpenoid lactones, act as root-derived chemical signals that modulate both symbiotic and parasitic interactions between AMF and their host plants [50]. SLs induce AM fungal spore germination and hyphal branching [51], while positively modulating root hair elongation/density and suppressing lateral root formation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that P. indica colonization profoundly altered carotenoid metabolism and phytohormone metabolism in blueberry roots.

Our study also found that P. indica colonization significantly increased the contents of total phenolics and flavonoids and greatly influenced the expression of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis/secondary metabolism-related genes. These findings indicated that fungal colonization improved the growth of blueberry under tap water irrigation by mediating the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. Additionally, enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed that genes involved in several stress response terms and responses to external stimulus pathways were significantly enriched, indicating that P. indica colonization influenced stress responses to mild salt damage caused by long-term tap water irrigation.

3.3. P. indica Promotes Blueberry Root Development by Enhancing Mineral Element Absorption and Sugar Transport Metabolism

P. indica enhances the uptake of mineral nutrients and other essential substances in host plants under both optimal and stressful conditions. In this study, P. indica colonization significantly increased concentrations of K, Ca, P, and Mg in blueberry roots, accompanied by substantial modulation of genes associated with solute transporter pathways. CNGCs play pivotal roles in diverse physiological processes in plants [52] and are recognized as critical calcium-permeable channels [53,54,55]. The MtCNGC15a/b/c genes modulate nuclear calcium release and play critical roles in rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbiotic processes in M. truncatula [56]. The CNGC family may regulate root hair tip growth, with CNGC5, CNGC6, CNGC9, and CNGC14 functioning as potential modulators of this process [57,58,59]. Mutations in CNGC5, CNGC6, and CNGC9 resulted in shorter root hairs [58], whereas defects in CNGC14 led to impaired root hair growth [59,60]. Our study revealed that P. indica colonization significantly up-regulated the expression of multiple CNGC genes and increased calcium content in blueberry roots, suggesting that P. indica promotes nutrient uptake through induction of CNGC gene expression, thereby facilitating root system development.

The symbiotic interaction with P. indica enhanced the phosphorus uptake of oilseed rape by increasing phosphatase activity and up-regulating the expression of the phosphate transporter gene BnPht1;4 [61]. This improvement was accompanied by significantly elevated accumulation of multiple essential elements [62]. P. indica colonization significantly enhanced wheat plant biomass and elevated zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) concentrations in both stems and roots, with these micronutrients preferentially accumulating of in roots rather than in stems [47], thereby contributing to improved grain yield. This study demonstrated that P. indica colonization significantly increased both ACP activity and P content in blueberry roots, indicating that fungal colonization promoted the phosphorus absorption ability of blueberry plants.

The hexose transporter HEX6 belongs to the sugar transporter family, which plays a critical role in carbohydrate allocation and stress responses in plants [63]. In this study, P. indica significantly up-regulated the expression of two HEX6 genes, as well as increased sucrose and starch accumulation in blueberry roots. These findings suggest that P. indica colonization may enhance hexose transporter activity through induction of HEX6 expression, thereby promoting carbohydrate storage. Trehalose produced by P. indica activates ABA signaling, forming a positive feedback loop that enhances drought resilience and yield stability in wheat [64]. Notably, the trehalose content in P. indica-colonized blueberry roots was markedly elevated. However, the trehalose metabolism pathway was significantly enriched by seven down-regulated TPP genes. This paradoxical pattern may reflect feedback inhibition triggered by excessive trehalose accumulation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and P. indica Inoculation

Healthy and uniform ‘Legacy’ blueberry plants (with plant height of 50–60 cm) grown in pots (Diameter = 28 cm; Height = 28 cm) filled with growth substrates (EC ≈ 210 μS/cm; pH = 5.0; Pindstrup, Ryomgård, Denmark) were divided into PI group and CK group. Each group consisted of at least 30 blueberry plants. Blueberry plants of the PI group were watered with 200 mL P. indica fermentation solution three times according to Cheng et al. [65], while CK group plants were watered with an equal volume of potato dextrose broth (PDB) as controls. The P. indica strain (DSM11827) used for blueberry inoculation was provided by professor KaiWun-Yeh of Taiwan University and maintained in our laboratory. After inoculation, blueberry plants were grown in a controlled growth chamber with a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C, a relative humidity range of 60–80%, a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark, and a light intensity of 1500 lx. Blueberry plants were irrigated with tap water every three days (pH 8.0, [EC] ≈ 450 μS/cm). To maintain low soil pH, 0.3~0.6 g/kg of finely powdered sulfur (particle size < 0.15 mm) was added to substrates quarterly [66]. By using the electrode method, the EC of substrates was monitored at 6, 12, and 18 months post tap water irrigation.

Three months post P. indica inoculation, genomic DNA was extracted from blueberry roots using a Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and used as the template for PCR amplification of the Pitef1 gene [67].

4.2. Determination of Root Fresh and Dry Weight and Root Activity

At 18 months post P. indica inoculation, root fresh weight and root dry weight of blueberry plants from CK and PI groups were measured. Root fresh weight of blueberry plants was first measured using an electronic balance (HAT-A+100, Huazhi (Fujian) Electronics Technology Co., Ltd., Putian, China). Then, root samples were oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight and weighted. Moreover, using the 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) reduction assay, root activities of CK and PI blueberry plants were measured [68]. For each parameter, six blueberry plants from each group were used.

4.3. Transcriptome Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from roots of CK and PI groups using the Trizol method. After assessing RNA purity, concentration, and integrity using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer/LabChip GX system (Santa Clara, CA, USA), high-quality RNA samples were subjected to RNA-Seq analysis using the Illumina NovaSeq6000 sequencing platform at Beijing Biomarker Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), with three biological replicates per group. Clean reads were aligned to the Vaccinium corymbosum L. genome (cv. Draper v1.0, https://www.vaccinium.org/analysis/49 (accessed on 25 July 2023)) with HISAT2. Mapped reads were then assembled using StringTie v3.0.0 and compared against the existing annotation to identify novel genes. Transcripts encoding peptides shorter than 50 amino acids or containing only a single exon were discarded.

4.4. Identification and Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

Gene expression levels across six samples were first normalized using the FPKM method [69]. DEGs between CK and PI groups were identified using the DESeq2-edgeR algorithm with thresholds of |log2(fold change)| ≥ 2 and p-value < 0.05. Gene ontology (GO) and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using the BMKCloud platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/) (q < 0.05). All transcripts were also functionally annotated using Mercator v4.0, and DEGs were also subjected to PageMan enrichment analysis using MapMan v3.6.0.

4.5. Gene Expression Validation by Using Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Fifteen DEGs involved in significantly enriched pathways were selected and subjected to qRT-PCR verification. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer3 v0.4.0 under default parameters (Supplementary Table S12). The qRT-PCR analysis was conducted according to Zhang et al. [70], with gapdh as the internal reference gene [71]. Relative expression levels of selected genes in CK and PI roots were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with three biological replicates.

4.6. Determination of ACP Activity and Mineral Element Contents in Blueberry Roots

The root ACP activity was determined using a detection kit produced by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Nitrogen content in blueberry roots was analyzed through sulfuric acid digestion coupled with the Kjeldahl method [72]. Phosphorus and potassium contents in blueberry roots were determined using sodium bicarbonate extraction followed by the molybdenum–antimony anti-spectrophotometric method [73], and ammonium acetate extraction coupled with flame photometry [74], respectively. Calcium and magnesium contents in blueberry roots were determined using HNO3-HClO4 digestion coupled with flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry [75]. All these parameters were measured with three biological replicates.

4.7. Measurement of Sucrose, Starch, Total Phenolic, Total Flavonoids, and Phytohormones Contents in Blueberry Roots

Root sucrose and starch contents in blueberry roots were quantified using commercial kits produced by Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The total phenolic and flavonoid contents in blueberry roots were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method [76] and the aluminum chloride colorimetric method [77], respectively. Endogenous contents of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), and strigolactone (SL) in roots were measured using plant-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Tongwei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). All these parameters were analyzed with four biological replicates.

4.8. Root Carotenoids Profiling and Analysis

Carotenoids in roots of CK and PI groups were further analyzed using an AB Sciex QTRAP 6500 LC-MS/MS (Framingham, MA, USA) system. For carotenoids profiling, a YMC C30 column (3 μm, 2.0 mm × 100 mm) was employed. The mobile phase comprised methanol/acetonitrile (1:3, v/v) with 0.01% BHT and 0.1% formic acid (A), and methyl tert-butyl ether with 0.01% BHT (B). The gradient program initiated at 100% A/0% B (v/v) for 3 min, linearly increased to 30% A/70% B (v/v) at 5 min, further raised to 5% A/95% B (v/v) at 9 min, held for 1 min for complete elution, then rapidly reverted to the initial conditions (100% A/0% B) and equilibrated until 11 min. The flow rate was set to 0.8 mL/min with a 2 μL injection volume.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

All data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2021 and are presented as mean ± SD from at least three biological replicates. SPSS 22.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the significance of differences of the measured parameters between CK and PI at the p < 0.05 level (Student’s t-test). For figure drawing, GraphPad Prism 8 was used.

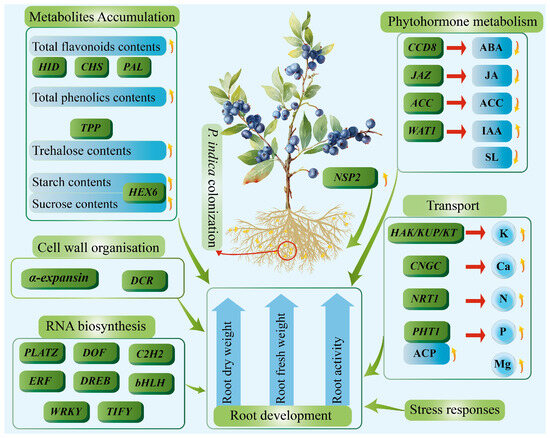

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that P. indica can promote blueberry root development under long-term tap water irrigation, which can cause mild salt stress in blueberry plants. Integrated transcriptomic and biochemical analyses revealed that fungal colonization enhanced blueberry root adaptability to tap water-induced mild salt stress by modulating cell wall metabolism, phytohormone metabolism, metabolites accumulation, stress responses, and nutrient transportation networks (Figure 6). Our study provides a theoretical foundation for the application of P. indica in blueberry cultivation.

Figure 6.

Influences of P. indica on the root development of blueberries under long-term tap water irrigation. P. indica greatly influences primary and secondary metabolites accumulation, cell wall organization, and RNA biosynthesis, and alters the phytohormone metabolism, nutrient transportation, and stress responses, thereby promoting blueberry root development. DEGs are shown in green boxes, and significantly changed biochemical parameters are shown in blue boxes/circles/arrows. Green arrows represent promoting effects on their pointed biological processes. Upward and downward yellow arrows indicate up-regulation and down-regulation, respectively.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14233646/s1, Figure S1: PCR detection results of P. indica colonization in blueberry roots. M: DL2000 DNA marker; P: positive control for the 250 bp Pitef1 amplicon; 1-3: non-inoculated control; 4-6: genomic DNA from P. indica-colonized blueberry roots; Table S1: The quality indicators of the transcriptome sequencing data used in this study; Table S2: GO enrichment analysis of the DEGs between CK and PI roots; Table S3: MapMan functional annotation and classification results of DEGs; Table S4: DEGs enriched in the RNA biosynthesis pathway; Table S5: DEGs enriched in the solute transport pathway; Table S6: DEGs enriched in the external stimuli response pathway; Table S7: DEGs enriched in the phytohormone action pathway; Table S8: DEGs enriched in the carbohydrate metabolism; Table S9: DEGs enriched in the cell wall organization pathway; Table S10: DEGs enriched in the secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathway; Table S11: Carotenoids in roots of P. indica-colonized and non-colonized blueberries; Table S12: Information of the primers used for the expression validation of the 15 selected DEGs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; Methodology, S.G. and P.Q.; Software, S.G. and P.Q.; Validation, S.D. and R.L.; Formal Analysis, S.G. and P.Q.; Investigation, S.G. and P.Q.; Resources, C.C. and Y.Z.; Data Curation, S.D. and R.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.G., P.Q., and C.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.C.; Visualization, S.G. and P.Q.; Supervision, C.C.; Project Administration, C.C.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z. and C.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanxi Key Laboratory of Germplasm Improvement and Utilization in Pomology (PILAB2025B02) and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shanxi Province (202203021211267 and 202403021212072).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| ACP | Acid phosphatase |

| AMF | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus |

| bHLH | Basic helix–loop–helix |

| BP | Biological processes |

| bp | Base pair |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CC | Cellular components |

| CCD8 | Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 8 |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| C2H2 | Cys2-His2 zinc finger |

| CHS | Chalcone synthase |

| CNGC | Cyclic nucleotide-gated channel |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DOF | DNA-binding with one finger |

| DREB | Dehydration-responsive element binding protein |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| ERF | Ethylene response factor |

| EXPA | Alpha-class expansin |

| Gb | Gigabase |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HEX6 | Hexose carrier 6 |

| HID | 2-hydroxyisoflavone dehydratase |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| K | Potassium |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LRR-XII | Leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases |

| MF | Molecular function |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NSP2 | Nodulation signaling pathway 2 |

| P | Phosphorus |

| PAL | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| PI | Piriformospora indica-colonized |

| PLATZ | Plant AT-rich sequence and zinc-binding protein |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| SL | Strigolactone |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| TPP | Trehalose-phosphate phosphatase |

| TTC | Triphenyltetrazolium chloride |

| WAT1 | Wall are thin 1 |

References

- Varma, A.; Savita, V.; Sudha; Sahay, N.; Butehorn, B.; Franken, P. Piriformospora indica, a cultivable plant-growth-promoting root endophyte. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2741–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zou, Y.-N.; Tian, Z.-H.; Wu, Q.-S.; Kuča, K. Effects of beneficial endophytic fungal inoculants on plant growth and nutrient absorption of trifoliate orange seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 277, 109815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.R.; Li, J.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Sun, M.L.; Huang, C.Y.; Wang, H.C. Analysis of growth dynamics in five different media and metabolic phenotypic characteristics of Piriformospora indica. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1301743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, R.A.; Li, D.; Liu, F.; Tian, N.; Sun, X.; Hao, X.; Lai, Z.; Cheng, C. Versatile Piriformospora indica and its potential applications in horticultural crops. Hortic. Plant J. 2020, 6, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druege, U.; Baltruschat, H.; Franken, P. Piriformospora indica promotes adventitious root formation in cuttings. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 112, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mensah, R.A.; Liu, F.; Tian, N.; Qi, Q.; Yeh, K.; Xuhan, X.; Cheng, C.; Lai, Z. Effects of Piriformospora indica on rooting and growth of tissue-cultured banana (Musa acuminata cv. Tianbaojiao) seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, B.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Lu, Z.; Lai, Z.; Cheng, C. Piriformospora indica promotes the growth and enhances the root rot disease resistance of gerbera. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 297, 110946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Wu, Q.-S.; Gao, X.-B. Serendipita indica is a biostimulant that improves tea growth at low P levels by modulating P acquisition and hormone levels. Rhizosphere 2023, 28, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Qu, P.; Wang, D.; Yan, S.; Gong, Q.; Yang, R.; Hu, Y.; Liu, N.; Cheng, C.; Wang, P.; et al. The influence of Piriformospora indica colonization on the root development and growth of Cerasus humilis cuttings. Plants 2024, 13, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, R.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C. Insights into the rooting and growth-promoting effects of endophytic fungus Serendipita indica in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorboori, M.R.; Zhang, H.Y. The role of Serendipita indica (Piriformospora indica) in improving plant resistance to drought and salinity stresses. Biology 2022, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Xing, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, Z.; Cai, H. Symbiotic system establishment between Piriformospora indica and Glycine max and its effects on the antioxidant activity and ion-transporter-related gene expression in soybean under salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeem, M.; Abdul Aziz, M.; Mullath, S.K.; Brini, F.; Rouached, H.; Masmoudi, K. Enhancing growth and salinity stress tolerance of date palm using Piriformospora indica. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1037273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Abdul Aziz, M.; Sabeem, M.; Kutty, M.S.; Sivasankaran, S.K.; Brini, F.; Xiao, T.T.; Blilou, I.; Masmoudi, K. Date palm transcriptome analysis provides new insights on changes in response to high salt stress of colonized roots with the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1400215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Pehlivan, N.; Ghorbani, A.; Wu, C. Effects of Azorhizobium caulinodans and Piriformospora indica co-inoculation on growth and fruit quality of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under salt stress. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.E.; Kim, D.; Ali, S.; Fedoroff, N.V.; Al-Babili, S. The endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica enhances Arabidopsis thaliana growth and modulates Na(+)/K(+) homeostasis under salt stress conditions. Plant Sci. 2017, 263, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, C.; Flores, S.; Reyes, M.; Urrutia, V.; Parra-Palma, C.; Morales-Quintana, L.; Ramos, P. Antarctic fungal inoculation enhances drought tolerance and modulates fruit physiology in blueberry plants. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 42, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Guo, Y.; Gu, L.; Shi, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, L. A novel growth-promoting dark septate endophytic fungus improved drought tolerance in blueberries by modulating phytohormones and non-structural carbohydrates. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.; Wu, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, D.; Gu, L.; Yang, L.; Zhao, W.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Tian, W.; et al. A bZIP transcription factor VabZIP12 from blueberry induced by dark septate endocyte improving the salt tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2022, 315, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzewik, A.; Marasek-Ciolakowska, A.; Orlikowska, T. Protection of highbush blueberry plants against Phytophthora cinnamomi using Serendipita indica. Agronomy. 2020, 10, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qu, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Liu, R.; Cheng, C. Insights into the underlying mechanism of the Piriformospora indica-enhanced drought tolerance in blueberry. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Lu, C.; Hou, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, L.; Li, J. Physiological responses and assessment of salt tolerance of different blueberry cultivars under chloride stress. Agronomy 2025, 15, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L. Na+-preferential ion transporter HKT1;1 mediates salt tolerance in blueberry. Plant Physiol. 2023, 194, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Bryla, D.R.; Vargas, O. Effects of salinity induced by ammonium sulfate fertilizer on root and shoot growth of highbush blueberry. In Acta Horiculturae; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2014; pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Kalo, P.; Gleason, C.; Edwards, A.; Marsh, J.; Mitra, R.M.; Hirsch, S.; Jakab, J.; Sims, S.; Long, S.R.; Rogers, J.; et al. Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science 2005, 308, 1786–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonouni-Farde, C.; Tan, S.; Baudin, M.; Brault, M.; Wen, J.; Mysore, K.S.; Niebel, A.; Frugier, F.; Diet, A. DELLA-mediated gibberellin signalling regulates Nod factor signalling and rhizobial infection. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, F.; Brault-Hernandez, M.; Laffont, C.; Huault, E.; Brault, M.; Plet, J.; Moison, M.; Blanchet, S.; Ichante, J.L.; Chabaud, M.; et al. Two direct targets of cytokinin signaling regulate symbiotic nodulation in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3838–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, S.; Fodor, L.; Domonkos, A.; Ayaydin, F.; Laczi, K.; Rakhely, G.; Kalo, P. Amino acid polymorphisms in the VHIID conserved motif of nodulation signaling pathways 2 distinctly modulate symbiotic signaling and nodule morphogenesis in Medicago truncatula. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 709857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Kohlen, W.; Lillo, A.; Op den Camp, R.; Ivanov, S.; Hartog, M.; Limpens, E.; Jamil, M.; Smaczniak, C.; Kaufmann, K.; et al. Strigolactone biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula and rice requires the symbiotic GRAS-type transcription factors NSP1 and NSP2. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3853–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marowa, P.; Ding, A.; Kong, Y. Expansins: Roles in plant growth and potential applications in crop improvement. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen-Mason, S.; Durachko, D.M.; Cosgrove, D.J. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.J.; Bedinger, P.; Durachko, D.M. Group I allergens of grass pollen as cell wall-loosening agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997, 94, 6559–6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, J.; Cosgrove, D.J. The expansin superfamily. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bashline, L.; Lei, L.; Li, S.; Gu, Y. Cell wall, cytoskeleton, and cell expansion in higher plants. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lantzouni, O.; Bruggink, T.; Benjamins, R.; Lanfermeijer, F.; Denby, K.; Schwechheimer, C.; Bassel, G.W. A molecular signal integration network underpinning Arabidopsis seed germination. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 3703–3712.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.T.; Cosgrove, D.J. Regulation of root hair initiation and expansin gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 3237–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, J. EXPANSINA17 up-regulated by LBD18/ASL20 promotes lateral root formation during the auxin response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yan, P.; Niu, F.; Ma, F.; Hu, J.; He, S.; Cui, J.; Yuan, X.; et al. OsEXPA7 encoding an expansin affects grain size and quality traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2024, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadamba, C.; Kang, K.; Paek, N.C.; Lee, S.I.; Yoo, S.C. Overexpression of rice expansin7 (osexpa7) confers enhanced tolerance to salt stress in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZhiMing, Y.; Bo, K.; XiaoWei, H.; ShaoLei, L.; YouHuang, B.; WoNa, D.; Ming, C.; Hyung-Taeg, C.; Ping, W. Root hair-specific expansins modulate root hair elongation in rice. Plant J. 2011, 66, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Shao, J.; Liu, Y.; Xuan, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, R. Signal communication during microbial modulation of root system architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, J. Brassinosteroids regulate root growth, development, and symbiosis. Mol. Plant. 2016, 9, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranocha, P.; Denance, N.; Vanholme, R.; Freydier, A.; Martinez, Y.; Hoffmann, L.; Kohler, L.; Pouzet, C.; Renou, J.P.; Sundberg, B.; et al. Walls are thin 1 (WAT1), an Arabidopsis homolog of Medicago truncatula NODULIN21, is a tonoplast-localized protein required for secondary wall formation in fibers. Plant J. 2010, 63, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranocha, P.; Dima, O.; Nagy, R.; Felten, J.; Corratge-Faillie, C.; Novak, O.; Morreel, K.; Lacombe, B.; Martinez, Y.; Pfrunder, S.; et al. Arabidopsis WAT1 is a vacuolar auxin transport facilitator required for auxin homoeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, F.; Stahl, M.; Ludewig, U.; Hirner, A.A.; Hammes, U.Z.; Stadler, R.; Harter, K.; Koch, W. Siliques are Red1 from Arabidopsis acts as a bidirectional amino acid transporter that is crucial for the amino acid homeostasis of siliques. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1643–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, V.; Wang, J.Y.; Bonfante, P.; Lanfranco, L.; Al-Babili, S. Apocarotenoids: Old and new mediators of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sakshi; Annapurna, K.; Shrivastava, N.; Varma, A. Symbiotic interplay of Piriformospora indica and Azotobacter chroococcum augments crop productivity and biofortification of Zinc and Iron. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 262, 127075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, D.; Guo, J.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Fu, W.; Miao, Y.; Jia, K.P. Carotenoid-derived bioactive metabolites shape plant root architecture to adapt to the rhizospheric environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.C.; Ma, B.; Collinge, D.P.; Pogson, B.J.; He, S.J.; Xiong, Q.; Duan, K.X.; Chen, H.; Yang, C.; Lu, X.; et al. Ethylene responses in rice roots and coleoptiles are differentially regulated by a carotenoid isomerase-mediated abscisic acid pathway. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1061–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiguchi, K.; Seto, Y.; Yamaguchi, S. Strigolactone biosynthesis, transport and perception. Plant J. 2021, 105, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Matsuzaki, K.; Hayashi, H. Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 2005, 435, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, Z.; Kakar, K.U.; Ullah, R.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Shu, Q.Y.; Ren, X.L. Genome-wide identification, evolution and expression analysis of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Genomics 2019, 111, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saand, M.A.; Xu, Y.P.; Li, W.; Wang, J.P.; Cai, X.Z. Cyclic nucleotide gated channel gene family in tomato: Genome-wide identification and functional analyses in disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Hou, C.; Ren, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, F.; Dahlbeck, D.; Hu, S.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Q.; Li, L.; et al. A calmodulin-gated calcium channel links pathogen patterns to plant immunity. Nature 2019, 572, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.K.; Prajapati, R.; Krishna, D.; Divakaran, K.; Pandey, Y.; Reichelt, M.; Mathew, M.K.; Boland, W.; Mithofer, A.; Vadassery, J. The Ca(2+) Channel CNGC19 regulates Arabidopsis defense against Spodoptera herbivory. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1539–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpentier, M.; Sun, J.; Vaz Martins, T.; Radhakrishnan, G.V.; Findlay, K.; Soumpourou, E.; Thouin, J.; Very, A.A.; Sanders, D.; Morris, R.J.; et al. Nuclear-localized cyclic nucleotide-gated channels mediate symbiotic calcium oscillations. Science 2016, 352, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brost, C.; Studtrucker, T.; Reimann, R.; Denninger, P.; Czekalla, J.; Krebs, M.; Fabry, B.; Schumacher, K.; Grossmann, G.; Dietrich, P. Multiple cyclic nucleotide-gated channels coordinate calcium oscillations and polar growth of root hairs. Plant J. 2019, 99, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Fei, C.F.; Gu, L.L.; Sun, S.J.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.F. Three CNGC family members, CNGC5, CNGC6, and CNGC9, are required for constitutive growth of Arabidopsis root hairs as Ca(2+)-permeable channels. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, Y.; Tian, W.; Dong, M.; Zhu, H.; Luan, S.; Li, L. Arabidopsis CNGC14 mediates calcium influx required for tip growth in root hairs. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, Q.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Zhang, X.; Dong, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Z.; Tian, W.; Zhu, H.; et al. The interaction of CaM7 and CNGC14 regulates root hair growth in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wei, Q.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Oelmüller, R.; Zhang, W. Piriformospora indica enhances phosphorus absorption by stimulating acid phosphatase activities and organic acid accumulation in Brassica napus. Plant Soil. 2018, 432, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.Z.; Wang, T.; Shrivastava, N.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, C.; Yin, Y.; Gao, Q.K.; Lou, B.G. Piriformospora indica promotes growth, seed yield and quality of Brassica napus L. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 199, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.A.; Thomas, M.A. The monosaccharide transporter gene family in Arabidopsis and rice: A history of duplications, adaptive evolution, and functional divergence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007, 24, 2412–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Aftab, M.N.; Aslam, M.S.; Rehman, A.U.; Haq, I.U.; Ali, S.; Usman, M. Trehalose–abscisic acid pathway feedback loops in wheat—Piriformospora indica symbiosis: Mechanisms and drought resilience. Microbe 2025, 9, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, D.; Wang, B.; Liao, B.; Qu, P.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, P. Piriformospora indica colonization promotes the root growth of Dimocarpus longan seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 301, 111137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylavarapu, R.; Hochmuth, G.; Mackowiak, C.; Wright, A.; Silveira, M. Lowering soil pH to optimize nutrient management and crop production. EDIS 2016, 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bütehorn, B.; Rhody, D.; Franken, P. Isolation and characterisation of Pitef1 encoding the translation elongation factor EF-1α of the root endophyte Piriformospora indica. Plant Biol. 2008, 2, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.; Kiyoshi, K.; Kadokura, T.; Suzuki, K.-I.; Nakayama, S. Elucidation of the enzyme involved in 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining activity and the relationship between TTC staining activity and fermentation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 131, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Jin, X.; Lin, H.; He, J.; Chen, Y. Comparative transcriptome sequencing and endogenous phytohormone content of annual grafted branches of Zelkova schneideriana and its dwarf variety Hentiangao. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu, P.; Hao, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, P.; Cheng, C. Characterization and functional analysis of chalcone synthase genes in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakola, L.; Maatta, K.; Pirttila, A.M.; Torronen, R.; Karenlampi, S.; Hohtola, A. Expression of genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in relation to anthocyanin, proanthocyanidin, and flavonol levels during bilberry fruit development. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.L. Kjeldahl Method for Total Nitrogen. Anal. Chem. 1950, 22, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Powlson, D.S. Preventing phosphorus losses during perchloric acid digestion of sodium bicarbonate soil extracts. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2006, 32, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.J.; Huang, W.; Wang, X.J.; Evrard, A.; Schmockel, S.M.; Zafar, Z.U.; Tester, M. A novel protein kinase involved in Na(+) exclusion revealed from positional cloning. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.R.; Gomes Neto, J.A.; Nóbrega, J.A.; Jones, B.T. Determination of macro- and micronutrients in plant leaves by high-resolution continuum source flame atomic absorption spectrometry combining instrumental and sample preparation strategies. Spectrochim. Acta B. 2010, 65, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Dominguez-Lopez, I.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. The chemistry behind the Folin-Ciocalteu method for the estimation of (Poly)phenol content in food: Total phenolic intake in a mediterranean dietary pattern. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17543–17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Yang, M.H.; Wen, H.M.; Chern, J.C. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colometric methods. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2002, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).