Abstract

Background: Dalmatian Zagora has experienced significant depopulation trends over recent decades. The area is very interesting because of its rich biodiversity of species as well as its history of the use of wild foods. Since there is a danger of permanent loss of knowledge on the use of wild edibles, we focused our research on recording traditions local to this area. Methods: We conducted interviews with 180 residents. Results: A record was made of 136 species of wild food plants and 22 species of edible mushrooms gathered in the area. The most frequently collected species are Rubus ulmifolius Schott, Cornus mas L., Portulaca oleracea L., Asparagus acutifolius L., Sonchus spp., Morus spp., Taraxacum spp., Amaranthus retroflexus L., Cichorium intybus L., and Dioscorea communis (L.) Caddick & Wilkin. Conclusions: The list of taxa used is typical for other (sub-)Mediterranean parts of Croatia; however, more fungi species are used. The most important finding of the paper is probably the recording of Legousia speculum-veneris (L.) Chaix, a wild vegetable used in the area.

1. Introduction

The documentation of ethnobotanical knowledge holds significant scientific value, particularly in the present age, marked by rapid social transformations, diminishing plant biodiversity, and the erosion of traditional knowledge of wild plant uses [1].

In the Mediterranean part of Europe, there is a long tradition of using wild plants for nutrition and medicinal treatment. The Mediterranean diet is known worldwide to have many health benefits, and the consumption of wild Mediterranean foods has certainly played a part in this. The frequent collection of wild foods, especially wild green vegetables, can be seen as an important, but often overlooked, part of the Mediterranean diet [2,3]. There are numerous studies showing that the Mediterranean diet, rich in alpha-linolenic acid, is responsible for the prevention and suppression of cardiovascular disease [4,5]. Green vegetables, nuts, seeds, game, and wild seafood are good sources of omega-3 fatty acids, and wild-collected vegetables are particularly rich in antioxidants and alpha-linolenic acid [6,7].

The use of wild foods in southern Europe is unfortunately declining, but the memory of many interesting wild vegetables is still preserved [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. In order to save this intangible cultural heritage from being lost, it is imperative that the last remnants of traditional knowledge and practices are captured, given their worrying decline [1].

Croatia is a Mediterranean country with rich plant biodiversity and a long tradition of using wild food and medicinal plants [14]. The first comprehensive ethnobotanical research in Croatia was carried out between 1962 and 1986 by Josip Bakić and his colleagues from the Institute of Naval Medicine of the Yugoslav Navy in Split [18]. Afterwards, there was a long pause in research on the use of wild plants in the area. This trend has changed, and new research has been carried out to fill this gap. Recent ethnobotanical studies have been carried out mainly in the Croatian coastal parts [12,14,19,20], and only to a lesser extent in the hinterland [21,22,23,24]. In a review article of ethnobotanical research in Croatia, authors Ninčević Runjić et al. [25] observed that rural inland areas remain scarcely investigated and are at the risk of permanent loss of traditional knowledge held by the local elder population. A look at the available literature shows that Dalmatian Zagora has not yet been sufficiently researched and represents a valuable source of traditional knowledge. In Dalmatian Zagora, only two smaller areas—Knin [23] and Poljica [22]—have been explored so far, with a large area remaining uninvestigated. Moreover, there is little data on the traditional use of edible mushrooms in Croatia, and research about it is very sparse [14,21,22,24].

Geographically, three natural borders and one state border define Dalmatian Zagora. The coastal mountain range is the border to the coastal part of Dalmatia, the river Krka is the border to the west, and Vrgorsko polje is to the east. In the north, the border overlaps with the state border of Bosnia and Herzegovina [26]. Large parts of Dalmatian Zagora have been included in the Natura 2000 ecological network.

From a social perspective, Dalmatian Zagora has long been confronted with negative population growth due to depopulation, emigration, and aging of the population [27]. Historical upheavals and foreign invaders have had a strong influence on migration, but also on the customs of the inhabitants. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the Turks conquered most of Dalmatian Zagora. For the next hundred years, this area was the border between the Ottoman and Christian worlds [26]. Emigration processes in Dalmatian Zagora began a long time ago and have intensified in the second half of the 20th century through the process of littoralization and deruralization, meaning that economic activities, populations, and settlements become increasingly concentrated in coastal regions. This trend often involves the abandonment of inland settlements, leading to a migration of both people and resources from the interior towards the coast [28]. The influence of littoralization on Dalmatian Zagora can be seen in the processes of urbanization, deruralization, industrialization, and tertiarization. At the same time, this area has remained ecologically preserved due to the lack of hard industry [29]. All of the above factors, as well as changing dietary habits, have contributed to the decline of traditional knowledge and practices related to wild food gathering and indicate the urgent need to document remaining knowledge. Thus, the aim of the study was to record the use of wild plants and fungi as food and in drinks in Dalmatian Zagora. The findings of this study will contribute to our understanding of the botanical richness within the region and underscore the importance of preserving traditional knowledge before it is lost to time.

2. Results

We recorded 136 species of edible plants used in the area (Table 1). On average, a respondent mentioned 15 species of wild food plants. The most cited edible plant species were Rubus ulmifolius Schott, Cornus mas L., Portulaca oleracea L., Asparagus acutifolius L., Sonchus spp., Morus spp., Taraxacum spp., Amaranthus retroflexus L., Cichorium intybus L., and Dioscorea communis (L.) Caddick & Wilkin.

Table 1.

Wild taxa of fungi and plants consumed in the study area.

We also recorded 22 taxa of edible fungi (Table 1), but only 16 taxa are eaten by more than one informant. On average, 0.8 species of fungi were mentioned per interview (only 30 informants, i.e., 18% of them, mentioned gathering fungi). The most commonly mentioned were Agaricus spp., Boletus edulis, Lactarius section Deliciosi, Macrolepiota, and Cantharellus cibarius. Fungi are gathered mainly in Sinj and Vrlika, with reports from seven informants per settlement out of the total 30 for the whole studied area.

In the entire Dalmatian Zagora, the largest number of taxa in terms of the mean number of species listed per interview was recorded in the Sinj area (25 species), then followed by Zagvozd and Podbablje (22) and Runović and Zmijavci (20). The lowest mean number of species was recorded in Šestanovac, Zadvarje, and Omiš (10), Prgomet (12), and Unešić and Ružić (12). There was a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.51, p = 0.044) between the mean number of species mentioned per interview and the number of inhabitants in each of the 16 studied units (regions). The units in which more than the average numbers of species were mentioned tend to be located east of Split, and those with the lowest knowledge were in the west. The number of cited species exceeded forty in four interviews: two from Sinj (sixty-one and forty-seven species), one from Podbablje (forty-five species), and another from Runovići (forty-four species).

The most collected parts were green parts (47%), followed by fruits (41%), flowers and flowering shoots with leaves (9%), and underground parts (3%).

Mišanca, also called divlje zelje, is the most commonly made wild dish, prepared in all parts of Dalmatian Zagora from different wild vegetables such as Sonchus oleraceus, Taraxacum officinale, Cichorium intybus, Allium ampeloprasum, Chenopodium album, Bunias erucago, Viola tricolor, Rumex sp., Foeniculum vulgare, Allium vineale, Bunias erucago, Silene vulgaris, Papaver rhoeas, and Capsela bursa-pastoris. Vegetables are boiled for a short time, often with the addition of potatoes. At the end, they are seasoned with salt and olive or sunflower oil.

The second most common dishes mentioned by respondents were Dioscorea communis and Asparagus officinalis eaten as a raw salad, or briefly cooked or fried with eggs, and seasoned with olive oil or vinegar. Portulaca oleracea was often mentioned as a favorite single-species salad.

A specialty associated with the Imotski region is the plant grzdulja, grdulja, i.e., Bunias erucago. It is mentioned numerous times by informants and also occurs in the records of the priest Silvestar Kutleša (1876–1943) [30], who wrote down the folk knowledge and customs of the people in the Imotski region. In the book, he mentions the frequent folk use of other wild plants: šurlin (Capsela bursa-pastoris), sparoga (Asparagus officinalis), koprva (Urtica sp.), and bljušt (Dioscorea communis). Grzdulja used to be boiled and seasoned with oil, butter, or lard; today, it is usually cooked with dried meat or as a vegetable pie.

Mushrooms are usually fried and served as a side dish and rarely cooked in stew (goulash or sauce). Apart from the drying of Boletus edulis, there is no tradition of mushroom preservation. The use of mushrooms in villages near Trilj and Sinj is related to their location by the river Cetina, where the agroclimatic conditions are suitable for their growth.

Wild fruits are often mentioned as having versatile uses. They are usually used ripe for immediate consumption or, more rarely, dried. They are also made into jam, liqueur, or compote. One frequently mentioned species is Rubus ulmifolius Schott. Older interviewees, in particular, stated that they ate it as children but also picked it for sale and used the money earned to buy books for school. Celtis australis, Cornus mas, Prunus spinosa, Morus nigra, and M. alba were mostly eaten while herding cattle on the pastures. The importance of the mulberry tree for the population’s diet is demonstrated by the popular saying “Pure i murve”, “polenta and mulberry”, which were eaten together as a poor man’s meal. Aria edulis, Torminalis glaberrima, Sorbus domestica, Pyrus communis subsp. communis, and Malus sylvestris were frequently eaten in the past, but respondents state that they rarely consume them today.

Some of the plants mentioned in the list are only used to flavor traditional alcoholic drinks, mainly travarica, where the >40% rakija contains a mix of several aromatic herbs, most commonly Satureja, Salvia rosmarinus, Laurus nobilis, Foeniculum vulgare, Teucrium sp., etc. Two respondents also mentioned a new trend of making jeger, a homemade Jägermeister-like drink inspired by the famous German liqueur. The difference between travarica and jeger is that the latter is made with plants more typical of the continental part of Croatia, as the people have borrowed the recipe from Germany; it is also sweetened, in contrast to the dry travarica made with aromatic Mediterranean herbs.

3. Discussion

The number and composition of wild foods gathered in the area is similar to other parts of southern Croatia [14,19,21,22]. In the research conducted in Dubrovnik, the usage of 95 wild edible species was documented [14]. On the Adriatic islands, 89 taxa of wild vegetables were identified [19], whereas 55 species were recorded in the Zadar area [21]. Additionally, the number of wild foods in the Krk and Poljica regions was 80 and 76, respectively [22]. The composition of wild foods comprising mainly wild vegetables is typical for the Mediterranean in contrast to Central Europe where the use of fruits and mushrooms dominates [11,31].

Although the most commonly mentioned species are widely known as edible, we found at least the memory of the use of some more unusual food plants.

Legousia speculum-veneris (L.) Chaix was mentioned by several informants as a wild vegetable eaten in the area. The use of this species as food has been reported in the literature only by Paoletti [32] in the Friuli region in NE Italy.

Another interesting species is Arum italicum Mill. Although plants from this genus are occasionally used in southwestern Asia and the Caucasus [33,34,35,36], it is not widely used in Europe nowadays as a food plant due to it incredibly sharp taste when eaten raw or underprocessed, owing to the presence of oxalates. According to Paura and Di Marzio [37], Arum sp. has been utilized as a food source across various regions of Europe, particularly valued for the starch extracted from its tubers, which is used in bread preparation. In Bosnia, the tubers of Arum italicum and A. maculatum continue to be employed in the cooking of boiled meats or focaccia [38]. Albania had a history of consuming Arum italicum during times of scarcity, with its usage evolving over time [39]. Additionally, the leaves are consumed in southeastern Europe after being boiled repeatedly, while in Switzerland Arum leaves are ingested in spring as part of a cleansing regimen [40]. In Italy, Arum italicum and A. maculatum are predominantly recognized for their medicinal properties, finding application in various ailments [41].

One more interesting species is Centaurea solstitialis L., previously mentioned as used only in the Ravni Kotari area near Vrana [21]. In the abovementioned paper, the species was only reported with the local name kravlja gubica (the same as in Zagora, literally “cow’s face”) and it was only a year after the publication of the paper that the authors identified the taxon, which is also eaten in Turkey [42].

It should be noted that over a third of the species in this study were mentioned only by one informant. The researcher is in a difficult position when assessing the use of species mentioned only by a single informant, as this information may be confounded by several factors:

- Relic uses—species once used more frequently, now remembered by one person;

- Rare uses—in cases when the plant was never an important useful species used only, e.g., as famine food;

- Idiosyncratic uses—uses restricted to one person are sometimes developed by them through experimentation or observation of foraging animals, e.g., sheep, goats, or pigs;

- Mistaken identification—when the informant does not remember the species well or supplies a mistaken voucher specimen.

In the case of our study, in most instances, we could assess the reliability of one-informant mentions by comparing local names and uses of plants in the neighboring regions. Some doubts remained concerning two uses not recorded elsewhere in the Balkans: Fumaria officinalis and Erythronium dens-canis. F. officinalis is a relatively toxic medicinal plant, so it was surprising to see it in a wild vegetable mix, and care should be taken with using it. In the case of E. dens-canis, ours is the first record of its consumption in the Balkans. The species has edible, starchy, and delicious underground corms. Only Sturtevant [43] mentions the use of the species in west or central Asia, quoting Gmelin (1747) [44]. He wrote that Tartars collected and dried the bulbs and boiled them with milk or broth [43], but this probably refers to the species sensu lato, now classified as E. sibiricum. The latter was widely eaten in Siberia [45], and E. japonium was consumed by the Ainu in Japan [46]. The American species of Erythronium were an important food item for the ethnic groups that lived in the western part of North America [47].

The presented data show that wild edible mushrooms are gathered by many inhabitants, although the inventory of most frequently used species is not long. By comparing out findings with other data on fungi uses in Europe, we could conclude that the local population is somewhere in the middle of the mycophilia–mycophobia spectrum invented by Wasson [48]. Some species are known by a portion of the population but there are also people who neither know or collect them. The reason for the relatively low interest in mushroom gathering may be the dry climate and the scarcity of wooded areas near settlements.

The relatively large list of wild vegetables and the frequent use of several of them place the local population high on the herbophilia spectrum [31], typically for the Mediterranean part of Europe, where gathering wild vegetables is one of the important though overlooked parts of the Mediterranean diet [2,3,13,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Another use of wild taxa recorded in research area was for preparation of traditional alcoholic beverages, mainly travarica (grape pomace distillate flavored with single or mixed species), that have received limited attention from researchers so far in Croatia [24,55]. What is worth highlighting is that nearly all the plants mentioned are either wild or cultivated locally, and the alcohol is produced locally, showing that traditional alcoholic beverages have a great role in the traditional culture and social life of the studied communities. This particularity related to alcoholic beverages was also recorded in the Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna regions [56,57].

Recently Łuczaj [1] wrote about the urgent need to record the disappearing uses of plants in the world. The large number of uses mentioned only by single individuals in this study illustrates the devolution of human–plant interactions. Here, in Dalmatian Zagora, some uses that were probably widely known by most inhabitants of many villages are now remembered by a single person in one.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

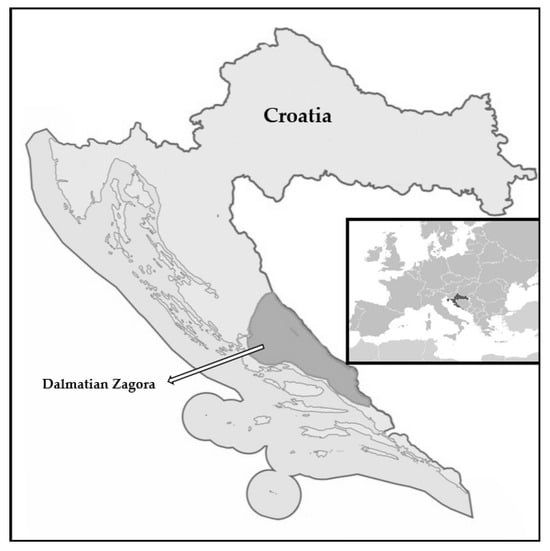

Dalmatian Zagora, while not an officially recognized administrative unit, is a conceptually expansive term delineating a region outlined by Delić [58]. Dalmatian Zagora represents part of the Dalmatian hinterland, and exact boundaries are given by the following authors. The definition by Faričić and Matas [26], corroborated through empirical research by Vukosav [28,59], forms the basis of its geographical extent, encompassing areas beyond the coastal hills of Trtar (738 m), Opor (650 m), Kozjak (780 m), Mosor (1330 m), Omiška Dinara (864 m), Biokovo (1762 m), and Rilić (1155 m). Its northern border aligns with the state border of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the western frontier is traced by the Krka basin, and the eastern border includes Vrgorsko polje and Rastok polje (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The area of Dalmatian Zagora.

Administratively, Dalmatian Zagora spans the territory of two counties: Split-Dalmatia and Šibenik-Knin, comprising 8 cities, 25 municipalities, and 293 settlements [60]. The 2021 Census reported 157.534 inhabitants within Dalmatian Zagora, among which there were 90.282 rural residents [61]. Dalmatian Zagora included a quarter of the population of the two counties in which it is located. At the same time, Dalmatian Zagora covered over 50% of the territory of these two counties. This disparity in population density is a consequence of littoralization and exceptional polarization between the coast and the hinterland [58]. Dalmatian Zagora sustains an average population density of 31 inhabitants/km2, notably lower than the Republic of Croatia’s 76 inhabitants/km2. As a result of numerous historical upheavals, this region witnessed a population decline of 81,011 inhabitants in four decades, signifying a reduction of over a third from its initial population [58].

Climate categorization, according to the Köppen classification, reveals two prevailing types in Dalmatian Zagora: a moderately warm humid climate with hot summers (Cfa) and a moderately warm humid climate with warm summers (Cfb) [62]. The region’s climate exhibits sub-Mediterranean characteristics closer to the coast, gradually transitioning to stronger continental influences farther inland. Vegetation primarily comprises degraded forms of maquis and garrigue [63].

Geographically, Dalmatian Zagora is characterized by limited arable land, with only single larger karst fields. Consequently, developmental opportunities in this region remain constrained, with agricultural pursuits—specifically arable farming and extensive animal husbandry—forming the primary economic activities [64].

4.2. Field Study

In this study, we included the entire Dalmatian Zagora, except the Poljica and Knin area, as it has already been comprehensively studied by Dolina et al. [22] and Varga et al. [23]. Initially, our field research plan aimed for a minimum of 15 interviews per local unit. However, upon visiting the settlements, we encountered challenges in identifying knowledgeable informants, owing to the region’s sparse population density. For this reason, we had to merge certain settlements into one unit, resulting in a total of 16 units instead of 19 (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of the studied units (municipalities).

The population of Dalmatian Zagora is gathered mostly around a few centers that have formed smaller historical regions: Drniš region, Imotski region, Knin region, Omiška (Poljička) Zagora, Sinj (Cetina) region, Vrgorac region, and Zagora (in the narrower sense) [26].

We conducted semi-structured interviews from March 2021 to September 2023. Data were collected mainly using the free listing method. The informants were selected following the snowball method [65] or were encountered during their work in the fields. Interviews were conducted in Croatian. The criterion was to examine only local residents, or those who have lived in the area for most of their lives. When possible, we organized walks with selected key informants to show us precisely which plants they collected. Plants were mostly identified on-site; otherwise, specimens were collected and identified by an experienced botanist (see Acknowledgments) using standard identification keys and iconographies [66,67].

We collected information about the respondents’ age, gender, place of residence, and place of origin. Altogether, 170 interviews were conducted with 195 people (145 interviews with single respondents and 25 interviews with 2 respondents). Among the respondents, 115 were women (59%) and 80 were men. The age of the interviewees ranged from 31 to 95 (average age = 66.38 median = 66).

Interviewees were asked questions about collected wild vegetables, roots, fruits, and mushrooms; their preparation methods; and the plant parts utilized. This study was conducted following the guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics [68] and the American Anthropological Association Code of Ethics [69]. Voucher plant specimens were collected and deposited in the Herbarium Croaticum (ZA) at the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science. Voucher fungi specimens were collected and deposited at the Department of Plant Sciences, Institute for Adriatic Crops and Karst Reclamation. Plant nomenclature adhered to Plants of the World Online [70].

The data matrix was stored in Microsoft Office 365 Excel version 2402. Correlations were calculated using the same program with Pearson’s correlation coefficient [71].

5. Conclusions

The studied region exhibits a rich diversity of edible plants indicating a significant knowledge of wild food resources. The wild plants consumed in the region studied are typical of this part of the Mediterranean and differ most from the Croatian coastal area in the higher consumption of mushrooms. There were some regional differences in the knowledge of edible plants and a moderate positive correlation was observed between the mean number of species mentioned per interview and the number of inhabitants in each region. Traditional dishes like “Mišanca”, made from various wild vegetables, are being prepared throughout the researched area, and specialty dishes containing Bunias erucago are specific only to certain regions within the area. Many plants are used to flavor traditional alcoholic drinks, showing a connection between local flora and cultural practices. The memory of the use of some other unusual food plants was also recorded: Legousia speculum-veneris, Arum italicum, and Centaurea solstitialis. The study was probably the last chance to document the fading tradition of wild food plant usage in this part of Croatia. The results will contribute to the general understanding of ethnobotany of the Mediterranean.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.-D., T.N.R. and Ł.Ł.; methodology, T.N.R., M.J.-D., M.R. and Ł.Ł.; formal analysis, T.N.R. and Ł.Ł.; investigation, T.N.R., M.J.-D. and M.R.; resources, T.N.R.; data curation T.N.R., M.J.-D. and Ł.Ł.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N.R. and Ł.Ł.; writing—review and editing, T.N.R., M.R., M.J.-D. and Ł.Ł.; supervision, Ł.Ł.; project administration, T.N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the European Regional Development Fund by the Operational program Competitiveness and Cohesion 2014–2020 within the project CEKOM 3LJ—Centre of Competence 3LJ KK.01.2.2.03.0017. The publication was supported by the European Union through the “NextGenerationEU” (project INOMED-2I; 09-207/1-23).

Data Availability Statement

The data matrix was deposited in the scientific data repository of Rzeszów University: https://rdb.ur.edu.pl/workflowitems/14/view (accessed on 15 March 2024).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Antun Alegro for his expertise in the determination of plant species and Vedran Šegota for helping in the preparation of herbarium specimens. We are grateful to all the participants in this study, especially Mladenka Puljiz, Anka Pašalić, Šimica Mastelić, Miljenka Runjić, and Željko Tandara, for sharing their knowledge and helping find other local informants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Łuczaj, Ł. Descriptive Ethnobotanical Studies Are Needed for the Rescue Operation of Documenting Traditional Knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Sulaiman, N.; Sõukand, R. Chorta (Wild Greens) in Central Crete: The Bio-Cultural Heritage of a Hidden and Resilient Ingredient of the Mediterranean Diet. Biology 2022, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Morini, G.; Piochi, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Kalle, R.; Haq, S.M.; Devecchi, A.; Franceschini, C.; Zocchi, D.M.; Migliavada, R.; et al. Bitter Is Better: Wild Greens Used in the Blue Zone of Ikaria, Greece. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lorgeril, M.; Renaud, S.; Salen, P.; Monjaud, I.; Mamelle, N.; Martin, J.L.; Guidollet, J.; Touboul, P.; Delaye, J. Mediterranean Alpha-Linolenic Acid-Rich Diet in Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. Lancet 1994, 343, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lorgeril, M.; Salen, P.; Martin, J.L.; Monjaud, I.; Delaye, J.; Mamelle, N. Mediterranean Diet, Traditional Risk Factors, and the Rate of Cardiovascular Complications after Myocardial Infarction: Final Report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation 1999, 99, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesalski, H.K.; Grimm, P. Pocket Atlas of Nutrition, 1st ed.; George Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, M.; Galli, C.; Visioli, F.; Renaud, S.; Simopoulos, A.P.; Spector, A.A. Role of Plant-Derived Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2000, 44, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Della, A.; Elena Giusti, M.; De Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Reyes Gonzales-Tejero, M.; Patricia Sanchez-Rojas, C.; Ramiro-Gutierrez, J.; et al. Wild and Semi-Domesticated Food Plant Consumption in Seven Circum-Mediterranean Areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 59, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirardini, M.P.; Carli, M.; del Vecchio, N.; Rovati, A.; Cova, O.; Valigi, F.; Agnetti, G.; Macconi, M.; Adamo, D.; Traina, M.; et al. The Importance of a Taste. A Comparative Study on Wild Food Plant Consumption in Twenty-One Local Communities in Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonti, M.; Nebel, S.; Rivera, D.; Heinrich, M. Wild Gathered Food Plants in the European Mediterranean: A Comparative Analysis. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild Food Plant Use in 21st Century Europe: The Disappearance of Old Traditions and the Search for New Cuisines Involving Wild Edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; ZovkoKončić, M.; Miličević, T.; Dolina, K.; Pandža, M. Wild Vegetable Mixes Sold in the Markets of Dalmatia (Southern Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscotti, N.; Pieroni, A.; Luczaj, L. The Hidden Mediterranean Diet: Wild Vegetables Traditionally Gathered and Consumed in the Gargano Area, Apulia, SE Italy. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2015, 84, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, K.; Łuczaj, Ł. Wild Food Plants Used on the Dubrovnik Coast (South-Eastern Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2014, 83, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, G.; Scariot, V.; Peira, G.; Lombardi, G. Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review. Land 2023, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V. Wild Food Plants Used in Traditional Vegetable Mixtures in Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 202–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Morales, R. Ethnobotanical Review of Wild Edible Plants in Spain. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 27–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug-Dujakovic, M.; Łuczaj, Ł. The Contribution of Josip Bakic’s Research to the Study of Wild Edible Plants of the Adriatic Coast: A Military Project with Ethnobiological and Anthropological Implications. Slovak Ethnol. 2016, 64, 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. The Ethnobotany and Biogeography of Wild Vegetables in the Adriatic Islands. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Insular Pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical Characteristics of Medicinal Plants Used on the Adriatic Islands. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 623070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Fressel, N.; Perković, S. Wild Food Plants Used in the Villages of the Lake Vrana Nature Park (Northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2013, 82, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, K.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. A Century of Changes in Wild Food Plant Use in Coastal Croatia: The Example of Krk and Poljica. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2016, 85, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, F.; Šolić, I.; Dujaković, M.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Grdiša, M. The First Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of the Knin Area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019, 88, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Hodak, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Marić, M.; Juračak, J. Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Central Lika Region (Continental Croatia)—First Record of Edible Use of Fungus Taphrina Pruni. Plants 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninčević Runjić, T.; Radunić, M.; Čagalj, M.; Runjić, M. Review of Ethnobotanical Research in Croatia. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1384, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faričić, J.; Matas, M. Zagora—Uvodne Napomene i Terminološke Odrednice. In Zagora Između Stočarsko-Ratarske Tradicije te Procesa Litoralizacije i Globalizacije, Zbornik Radova; Ogranak Matice Hrvatske Split: Split, Croatia, 2011; pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nejašmić, I. Posljedice Budućih Demografskih Promjena u Hrvatskoj. Acta Geogr. Croat. 2012, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vukosav, B. Percepcija Prostornog Obuhvata Zagore u Odabranim Kartografskim Izvorima. Kartogr. Geoinf. 2015, 14, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Faričić, J. Zagora—Dobitnik Ili Gubitnik u Litoralizaciji Srednje Dalmacije. In Zagora Između Stočarsko-Ratarske Tradicije te Procesa Litoralizacije i Globalizacije, Zbornik Radova; Ogranak Matice Hrvatske Split: Split, Croatia, 2011; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kutleša, S. Život i Običaji u Imockoj Krajini; Matica Hrvatska, Ogranak Imotski, Hrvatska Akademija Znanosti i Umjetnosti Zavod za Znanstveni i Umjetnički Rad u Splitu: Imotski, Croatia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł. Changes in the Utilization of Wild Green Vegetables in Poland since the 19th Century: A Comparison of Four Ethnobotanical Surveys. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoletti, M.G.; Dreon, A.L.; Lorenzoni, G.G. Pistic, Traditional Food from Western Friuli, N.E. Italy. Econ. Bot. 1995, 49, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Al-Shafie’, J.H.; Elgharabah, W.A.; Kherfan, F.A.; Qarariah, K.H.; Khdair, I.S.; Soos, I.M.; Musleh, A.A.; Isa, B.A.; et al. Traditional Knowledge of Wild Edible Plants Used in Palestine (Northern West Bank): A Comparative Study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Paniagua Zambrana, N.Y.; Ur Rahman, I.; Kikvidze, Z.; Sikharulidze, S.; Kikodze, D.; Tchelidze, D.; Khutsishvili, M.; Batsatsashvili, K. Unity in Diversity—Food Plants and Fungi of Sakartvelo (Republic of Georgia), Caucasus. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R.; Polesny, Z. Food Behavior in Emergency Time: Wild Plant Use for Human Nutrition during the Conflict in Syria. Foods 2022, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, F.; Akar Sahingoz, S. Using Ethnobotanical Plants in Food Preparation: Cuckoo Pint (Arum maculatum L.). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 29, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paura, B.; Di Marzio, P. Making a Virtue of Necessity: The Use of Wild Edible Plant Species (Also Toxic) in Bread Making in Times of Famine According to Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1766). Biology 2022, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakic, J.; Popovic, M. Nekonvencionalni Izvori u Ishrani na Otocima i Priobalju u Toku NOR-A; Pomorska biblioteka; Izdanje Mornaričkog Glasnika: Belgrade, Serbia, 1983; Volume 33, pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Saraçi, A.; Damo, R. A Historical Overview of Ethnobotanical Data in Albania (1800s–1940s). Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couplan, F. Le Régal Végétal. Reconnaître et Cuisiner Les Plantes Comestibles; Sang de la Terre: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pagni, A.M.; Corsi, G. Studi Sulla Flora e Vegetazione Del Monte Pisano (Toscana Nord-Occidentale). 2. Webbia 1979, 33, 471–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenkardeş, İ.; Bulut, G.; Doğan, A.; Tuzlaci, E. An Ethnobotanical Analysis on Wild Edible Plants of the Turkish Asteraceae Taxa. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2019, 84, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, E.L.; Hedrick, U.P. Sturtevant’s Notes on Edible Plants; J.B. Lyon Company: Albany, NY, USA, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Gmelin, J.G. Flora Sibirica Sive Historia Plantarum Sibiriae; Imperial Academy of Sciences: St Petersburg, Russia, 1747; Volume 1. (In Latin) [Google Scholar]

- Ståhlberg, S.; Svanberg, I. Gathering Dog’s Tooth Violet (Erythronium sibiricum) in Siberia. Suom.-Ugr. Seuran Aikakauskirja 2011, 2011, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anetai, M.; Ogawa, H.; Hayashi, T.; Aoyagi, M.; Chida, M.; Muraki, M.; Yasuda, C.; Yabunaka, T.; Akino, S.; Yano, S. Studies on Wild Plants Traditionally Used by the Ainu People (Part I): Contents of Vitamins A, C and E in Edible Plants. Rep. Hokkaido Inst. Public Health 1996, 46, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Moerman, D. Native American Ethnbotany; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin-Pasternak, S. Ethnomycology: Fungi and Mushrooms in Cultural Entanglements. In Ethnobiology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Blanco, E.; Carvalho, A.M.; Lastra, J.J.; San Miguel, E.; Morales, R. Traditional Knowledge of Wild Edible Plants Used in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): A Comparative Study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydoun, S.; Hani, N.; Nasser, H.; Ulian, T.; Arnold-Apostolides, N. Wild Leafy Vegetables: A Potential Source for a Traditional Mediterranean Food from Lebanon. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 991979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hani, N.; Abulaila, K.; Howes, M.J.R.; Mattana, E.; Bacci, S.; Sleem, K.; Sarkis, L.; Eddine, N.S.; Baydoun, S.; Apostolides, N.A.; et al. Gundelia tournefortii L. (Akkoub): A Review of a Valuable Wild Vegetable from Eastern Mediterranean. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platis, D.P.; Papoui, E.; Bantis, F.; Katsiotis, A.; Koukounaras, A.; Mamolos, A.P.; Mattas, K. Underutilized Vegetable Crops in the Mediterranean Region: A Literature Review of Their Requirements and the Ecosystem Services Provided. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Loera, R.D.C.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M.; Marqués, C.D.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J. Wild Vegetables of the Mediterranean Area as Valuable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.; Carocho, M.; Di Gioia, F.; Petropoulos, S.A. The Beneficial Health Effects of Vegetables and Wild Edible Greens: The Case of the Mediterranean Diet and Its Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Plants in Alcoholic Beverages on the Croatian Islands, with Special Reference to Rakija Travarica. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, T.; Signorini, M.A.; Bruschi, P.; Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Alcaraz, F.; Palazón, J.A. Spirits and Liqueurs in European Traditional Medicine: Their History and Ethnobotany in Tuscany and Bologna (Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, T.; Signorini, M.A.; Ongaro, L.; Rivera, D.; Obón de Castro, C.; Bruschi, P. Traditional Alcoholic Beverages and Their Value in the Local Culture of the Alta Valle Del Reno, a Mountain Borderland between Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna (Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delić, D. Demogeografski Procesi i Značajke u Dalmatinskoj Zagori. Master’s Thesis, University of Zagreb Faculty of Science and Mathematics, Zagreb, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vukosav, B. Geografsko Ime “Zagora” i Njegova Pojavnost Na Područjima Dalmatinskoga Zaleđa u Odabranom Novinskom Mediju. Geoadria 2011, 16, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Državni Zavod za Statistiku. Popis Stanovništva, Kućanstava i Stanova 2011. Statistička Izvješća ISSN 1333—1876; Državni Zavod za Statistiku: Zagreb, Croatia, 2011.

- Državni Zavod za Statistiku. Popis Stanovništva, Kućanstava i Stanova 2021. Statistička Izvješća ISSN 1333—1876; Državni Zavod za Statistiku: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021.

- Filipčić, A. Razgraničenje Köppenovih Klimatskih Tipova Cf i Cs u Hrvatskoj. Acta Geogr. Croat. 2000, 35, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst-Bjeliš, B.; Cvitanović, M.; Durbešić, A.; Lozić, S. Promjene Okoliša Središnjeg Dijela Dalmatinske Zagore Od 18. St. In Zagora Između Stočarsko-Ratarske Tradicije te Procesa Litoralizacije i Globalizacije, Zbornik Radova; Ogranak Matice Hrvatske Split: Split, Croatia, 2011; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Matas, M. O Gospodarskim Prilikama Zagore—Jučer, Danas i Sutra. In Gospodarske Mogućnosti Zagore i Oblici Njihova Optimalnog Iskorištavanja, Zbornik Radova; Institut za Jadranske Kulture i Melioraciju Krša: Split, Croatia; Kulturni Sabor Zagore, Podružnica Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Domac, R. Flora Hrvatske: Priručnik za Određivanje Bilja; Školska Knjiga, Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jávorka, S.; Csapody, V. Iconographiae Florae Partis Austro-Orientalis Europae Centralis; Akademiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- International Society of Ethnobiology. ISE Code of Ethics (with 2008 Additions). Available online: https://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- American Anthropological Association Code of Ethics. Available online: https://americananthro.org/about/anthropological-ethics/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Kendall, M.G.; Stuart, A. The Advanced Theory of Statistics. Volume 2: Inference and Relationship; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).