Abstract

The National Park of Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga (PNGSL) is located in Central Italy and covers an area of 143.311 ha across three administrative regions (Abruzzo, Marche, and Lazio). It is the protected area hosting the highest number of vascular plants in both Europe and the Mediterranean basin. The plan of the park recognizes the need to establish a list of plants of conservation interest to prioritize for protection. The aim of this study is to identify plants (vascular and bryophytes) for inclusion on a protection list, taking into account their phytogeographic importance as well as the threat of extinction, and subsequently propose an original categorization (protection classes) suggesting specific conservation actions and measures. We used original criteria to select plants of conservation interest among the 2678 plant taxa listed in the national park. We identified 564 vascular plant species and subspecies (including nine hybrids) and one bryophyte to be included in the proposed protection list. The case study of the PNGSL could be a model for other protected areas.

1. Introduction

Conservation of biodiversity requires careful planning [1,2,3,4], as it is not possible to assist all species under threat, typically due to limited funding and human resources [5]. Priorities must therefore be established by making a list of plants of conservation interest at different levels [1,2,3]. It is critical to select conservation priorities and management strategies that are most effective and proper for the local area.

A consistent list of plants of conservation interest, even at a local level, can be deduced from red lists. The IUCN Categories and Criteria were developed to improve objectivity and transparency in assessing the conservation status of species, and thus to improve consistency and understanding among users [6]. In Italy, the more recently published red lists [7] include policy species (taxa listed in the annexes of the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC and Bern Convention), taxa endemic to Italy [8,9], and a group of taxa of conservation concern (plants occurring in highly threatened habitats (e.g., wetlands and coastal habitats) and/or considered as EX, EW, or CR in the previous Italian red lists [10,11]. The conservation process is strictly linked to the distribution and biogeography of taxa [12]. It is important to simultaneously consider multiple criteria such as rarity, endemicity, and risk of extinction for the purposes of conservation prioritization [13]. Protected areas play a fundamental role in the conservation of plant diversity [14,15,16] by allowing space for the development of appropriate strategies for in situ [17,18] and ex situ protection [19,20], for the preservation of a single species or some selected policy species [21,22,23], and for drafting lists of plants of conservation interest [24,25,26,27]. The Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga National Park (hereafter, PNGSL) is the protected area with the highest number of vascular plants (species and subspecies) in both Europe and the Mediterranean basin [28].

The aim of the national park is to identify a list of plants of conservation interest to be included in the “Beni Ambientali Individui” [Individual Environmental Assets] (hereafter, BAI). The BAI, as defined by art. 16 of the Implementation legislation of the Plan, albeit with improper terminology, are emergencies of any type “recognized by national and international regulations, or identified by studies and research by the Park Authority or other competent subjects (institutional and otherwise)”.

The aim of this study is to select plants to be included in a protection list, as commissioned by the PNGSL. We considered not only the plants under threat included in the red lists or in the regional protection regulations but also plants worthy of note for their phytogeographical interest, which was determined by assessing their endemicity, rarity, disjunction, or range limit. Therefore, we proposed original criteria to select plants and five protection classes with different appropriate levels of knowledge, conservation measures, and actions for protection, management, and monitoring. We have also developed an analogous list of plants by adopting similar criteria and measures for the Abruzzo, Lazio, and Molise National Parks [29].

2. Results

Based on the objective criteria identified (Table 1), 564 vascular plant species and subspecies (including nine hybrids) and one bryophyte were included in the protection classes. For each species and subspecies, the taxonomic group, family, endemicity, protection class, criteria, inclusion in red lists, and relevant regional laws for the protection of flora or international conventions are reported (see File S1).

Table 1.

Criteria for defining the conservation classes of plants of conservation interest. Classes: A—highest conservation interest; B—high conservation interest; C—good conservation interest; D—highest to good conservation interest but with doubtful taxonomic value or belonging to critical groups of Italian flora; E—extinct or not confirmed to the study area.

In total, 21% of the flora of the PNGSL are vascular plants included in the BAI. Among these, 165 taxa belong to the higher protection classes (A and B), and 12 can be considered probably extinct in the study area. This latter number is high mainly due to the destruction of the Campotosto peat bog in the first half of the 19th century, with the creation of the homonym artificial lake. Some of these plants, such as Carex lasiocarpa Ehrh., C. elongata L., Comarum palustre L., Salix rosmarinifolia L., etc., should be considered disappeared from the entire Apennines [9].

Some new populations of taxa included in the higher protection classes (A and B) are monitored every year. Furthermore, newly discovered taxa in the flora of the park, included in the higher protection classes, are usually monitored from the time of their discovery (e.g., Huperzia selago (L.) Bernh. ex Schrank and Mart., Oxytropis ocrensis and Ranunculus lateriflorus DC.).

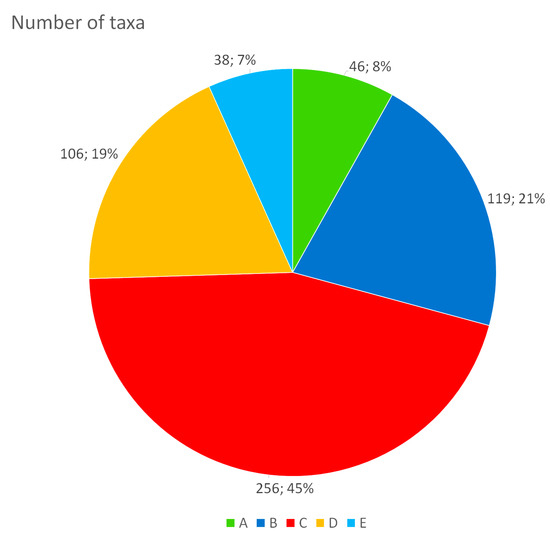

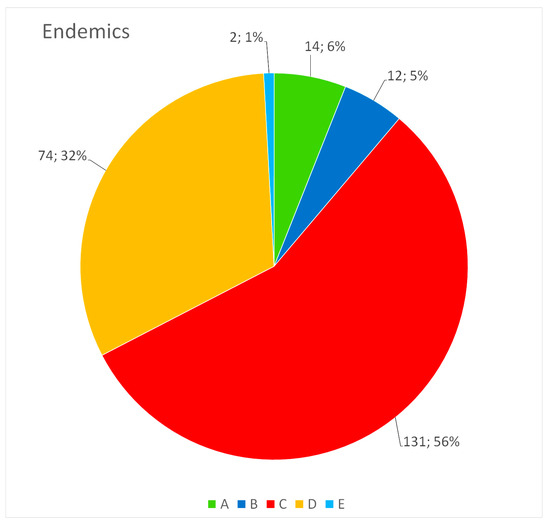

The number of species and subspecies (including bryophytes) for each of the protection classes is as follows (Figure 1): A (46), B (119), C (256), D (106), E (38). Endemic plants are distributed throughout the different classes, as reported in Figure 2. Analyzing the 46 plants included in class A, based on preferential growth habitat, almost all of them live in humid environments (15) and mainly in peat bogs, little lakes, or pools (e.g., Allium permixtum Guss., Carex canescens L. subsp. canescens, C. davalliana Sm., Elatine alsinastrum L., Juncus sp. pl., Ranunculus bariscianus Dunkel, R. giordanoi F.Conti and Bartolucci, R. lateriflorus DC., R. pedrottii Spinosi ex Dunkel, Salix pentandra L. and Vallisneria spiralis L.). Other significant contingents are represented by high-altitude plants, which include species endemic to the Central Apennines such as Adonis distorta Ten., Androsace mathildae Levier, Oxytropis ocrensis F.Conti and Bartolucci, Saxifraga italica D.A.Webb and Soldanella minima Hoppe subsp. samnitica Cristof. and Pignatti. A third contingent is represented by steppe plants such as Adonis vernalis L., Alyssum desertorum Stapf, Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn. subsp. gotlandica (Neuman) B.Nord., including some endemic taxa such as Astragalus aquilanus Anzal., Gonliolimon tataricum (L.) Boiss. subsp. italicum (Tammaro, Pignatti and Frizzi) Buzurović and Stipa aquilana Moraldo. The last group of plants is linked to nemoral environments in the past subjected to excessive forest cutting (Astragalus penduliflorus Lam., Botrychium matricariifolium (A.Braun ex Döll) W.D.J.Koch, Buphthalmum salicifolium L. subsp. salicifolium, Orobanche salviae F.W. Schultz, Struthiopteris spicant (L.) Weiss.).

Figure 1.

Number and percentage (%) of taxa included in each of the protection classes: A—highest conservation interest; B—high conservation interest; C—good conservation interest; D—highest to good conservation interest but with doubtful taxonomic value or belonging to critical groups of Italian flora; E—extinct or not confirmed to the study area.

Figure 2.

Number and percentage (%) of plants endemic to Italy included in each of the protection classes: A—highest conservation interest; B—high conservation interest; C—good conservation interest; D—highest to good conservation interest but with doubtful taxonomic value or belonging to critical groups of Italian flora; E—extinct or not confirmed to the study area.

Examining the plants belonging to the highest protection classes (A and B), it is evident that they live in the most threatened habitats, and therefore, their conservation involves the protection of the habitat in which they grow.

The populations of 32 species and subspecies included in the protection classes A, B, and E were monitored between 2012 and 2023. Some populations of Allium permixtum Guss., Buphthalmum salicifolium L. subsp. salicifolium, Diphasiastrum complanatum (L.) Holub, whose occurrences in the Park’s territory are due to the existence of old herbarium specimens housed in APP, CAME, and FI [30], were not found during field activities. For all the monitored populations, data concerning the species’ localization, population size, and threats and pressures were collected. These data are collected in a specific database that the technicians of the park have at their disposal and can consult when an intervention is proposed that could damage species or habitats within the park’s territory. Upon specific request, and subject to authorization from the Park Authority, even private persons involved in activities within the Park’s territory can request to view this data. Some populations of species particularly at risk due to ongoing pressures have been monitored several times over the years, confirming their good state of conservation thanks also to the specific measures implemented (i.e., Orobanche salviae F.W.Schultz). The information collected during monitoring relates to rare or at-risk species and is therefore particularly sensitive, which is why we do not make it available in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2.

Taxa monitored between 2012 and 2023.

3. Discussion

This study, at first funded by PSR Abruzzo Region (2007–2013—Axis 3—Call for Measure 3.2.3), was carried out as part of the drafting of the management plans of Natura 2000 sites (natural sites in Europe protected under the EU Birds and Habitats Directives) and subsequently updated on behalf of the PNGSL. The Decree of Italian Republic President (DPR 357/07) establishes that, in the case of Natura 2000 sites falling within Protected Areas sensu L. 394/91, the plan of the site, with the appropriate conservation measures pursuant to the Habitat Directive, must be integrated into the Management Plan. Furthermore, the latter must respect the Regulation already drawn up for the Protected Area itself, respectively, by Arts. 11 and 12 of the framework law on protected areas. The Plan of the PNGSL, adopted and approved by the Governing Council Resolution of the National Park n. 35/99 of 21 December 1999 and by the Abruzzo, Marche, and Lazio administrative regions, was published in the “Gazzetta Ufficiale” Part II n. 124 of 22/10/2020. The protection of plant species occurring in the area is among the aims of the Park, in particular, those that are rare and at risk of extinction. The identification of these noteworthy floristic taxa (included in the BAI) and the related habitat, as well as the implementation of appropriate forms of protection, also find application in the Park Plan. Regarding flora, the Plan provides that “all endemic, relict, rare or endangered species included in the National and Regional Red Lists, as well as species of Community Importance (identified by the Habitat Directive) and of International Conventions” should be protected. The need for conservation of these plants is highlighted by the Plan, which “recognizes the need to subject them to maximum protection, even if located in areas that do not coincide with the Reserves”. In fact, the zoning of the Park for the Management Plan was obtained according to more general criteria, which did not consider the specific presence of species of conservation interest [31]. The integration between zoning and art. 16 for the BAI guarantees the optimal protection of species of conservation interest. The Park Regulations also “specify, integrate and, if appropriate, enrich the above list and regulate in detail the methods of protection”, based on the progress of knowledge of the subject.

Any economic activities within the Park, promoted mostly by private individuals, require an evaluation often based on the presence of BAIs. The correct application of the management indications for the plants included in the protection classes as indicated in Table 3, and provided by the Offices of PNGSL, allowed the implementation of an exhaustive and standardized assessment of the impacts derived from activities, works, and events and in general for any type of authorization request received by the Park.

Table 3.

Management indications for the plants included in the protection classes.

For all the monitored populations included in the BAIs, fundamental data were collected to understand, maintain and, where possible, improve the conservation status of the plant species involved. These data, entered into a specific database, are available to Park technicians. A recent case is worth mentioning here. In 2020, the Park Authority received a request for authorization from a company that deals with the distribution of electricity across the national territory for the reconstruction of an overhead power line section, involving the replacement of support elements. The Park Authority Office, responsible for issuing the authorization, consulted, as is now internal practice, the distribution of the BAIs, noting the presence of some populations of Astragalus aquilanus close to the intervention site. The Office requested an in-depth check before starting the work, which revealed the presence of a not known population of Astragalus aquilanus (All. II* of Habitat Directive, included in A class of BAI) exactly in the intervention site. Consequently, suitable measures and modifications to the project have been defined in order to safeguard the population.

The need to propose a list of plants to be protected, such as the BAIs, is closely linked to the fact that there are no European, national, or even local regulations that can be considered satisfactory for the protection of endemic or rare flora of conservation and biogeographical interest.

At the local level, the adoption of a list of species of conservation interest (BAIs) seems to be a good solution, especially for protected areas, which often do not have useful tools for the protection of flora, apart from the few plants included in the Habitats Directive. In Italy, only 115 taxa (104 vascular plants, 10 bryophytes, 1 lichen) are included in Annexes II, IV, and V of the Habitats Directive [32]: a very small number compared to the high floristic richness of Italy, in which 8241 species and subspecies are registered, including 1702 taxa endemic to Italy or narrowly endemic to restricted areas [9]. At the regional level, the use of the list of Abruzzo administrative region is quite inappropriate because the only law is old and does not respond to the current needs that knowledge requires (regional laws n. 45/1979 and 66/1980). We proposed a regional law with a list of vascular plants to protect [33], recently updated but not yet implemented by the regional authorities. At the national level, there is no regulation on this concern. For this reason, extremely rare and threatened species are not adequately protected (i.e., Goniolimon tataricum subsp. italicum, strictly endemic to the L’Aquila basin, which is not protected by any Law or Directive and live outside any protected area). There is a felt need to promote both regional and national lists of plants to be protected which can be updated annually or every two years. It can be conducted through a review, the nomenclature, distribution and belonging classes of the species considered, following the French example (Liste des espèces végétales protégées sur l’ensemble du territoire français métropolitain in Inventaire National du Patrimoin Naturel, 2023) or the Spanish one by the Law 42/2007, of Natural Heritage and Biodiversity.

4. Conclusions

The conservation of plant biodiversity is a central theme and a crucial challenge globally. The main causes of the loss of biodiversity are attributable to the growing consumption of land with consequent reduction and fragmentation of natural habitats, climate change, and, no less importantly, the often devastating impact that invasive alien species have on native species and natural ecosystems. To combat the loss of plant biodiversity, correct, systematic, and conscious planning of conservation strategies is necessary, accompanied by concrete in situ and ex situ protection actions. Unfortunately, international, national, or local laws concerning the protection of native flora in Italy underestimate the plant biodiversity of our territory, making it impossible to concretely safeguard and conserve the rarest and most endangered species. From this perspective, the creation of a list of plants of conservation interest, developed, managed, and updated by a National Park Authority, becomes an essential tool for the knowledge, management, and protection of plant biodiversity at a local level.

5. Materials and Methods

Thanks to the institution of the Apennine Floristic Research Center in 2001, managed by the University of Camerino (UNICAM) and the PNGSL [34], the vascular flora of the Park has been critically studied and continuously updated [35]. Recently, 14 new taxa (species and subspecies) have been recorded for the protected area: Carex strigosa Huds., Ranunculus pedrottii Spinosi ex Dunkel [36], Anthyllis apennina F.Conti and Bartolucci, Taraxacum pudilii Štěpánek and Kirschner [37], Oxytropis ocrensis F.Conti and Bartolucci, Aubrieta deltoidea (L.) DC., Opuntia scheeri F.A.C.Weber, Trachelium caeruleum L. subsp. caeruleum [38], Anacamptis berica Doro [39], Astragalus austriacus Jacq., Festuca bosniaca Kumm. and Sendtn. subsp. bosniaca, Ranunculus lateriflorus DC., Soldanella minima subsp. samnitica Cristof. and Pignatti, Erigeron annuus subsp. strigosus (Muhl. ex Willd.) Wagenitz [40,41]. Furthermore, Pulmonaria officinalis L. subsp. officinalis reported by [42] was not cited by [35] in the recent update of the Park’s flora, while Cytinus hypocistis (L.) L. subsp. hypocistis and Carex microcarpa Bertol. ex Moris should be excluded from the Park [43]. Currently, 2678 taxa (species and subspecies) are known, 233 of which are endemic to Italy. Among these, 114 are endemic to the Central Apennines and 12 are narrow endemics to the PNGSL. All the floristic data (from bibliographic and herbarium sources) concerning vascular plants and bryophytes of the Park were entered into a geodatabase using File Maker Pro software version 19.2.2.234. The geodatabase, continuously updated, includes data for the Abruzzo administrative region and the neighboring areas in Molise, Lazio, and Marche included within PNGSL and Abruzzo, Lazio, and Molise National Park. The locations, coming from herbarium samples or bibliography, of the species reported in the Abruzzo geodatabase, are georeferenced [44].

Starting from the checklist of the Park’s flora, we identify the plants to be included in the protection list based on the following criteria:

- -

- Endemic species to Italy [8,9];

- -

- Exclusive species of one of the administrative regions in which the Park territory falls (species also distributed outside the national borders, but in Italy present in only one administrative region [9]);

- -

- Exclusive species to the Park (species distributed also outside the national borders, but in Italy present only in the Park [28,35]);

- -

- Very rare or rare plants according to the current level of knowledge relating to Central Italy;

- -

- Plants with disjointed populations (species present in the Park with a portion detached from the main distribution range);

- -

- Plants listed in regional laws concerning the protection of the flora (L. R. Abruzzo n. 45 of 11/09/1979, L. R. Abruzzo n. 66 of 20/06/1980; L. R. Marche n. 8 of 10.01.1987; L. R. Lazio n. 61 of 19.09.1974);

- -

- Plants listed in the international regulations (Habitat Directive 92/43 EEC; Convention on the Conservation of Wild Life and Natural Habitats, Bern 1979; Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora CITES, Washington 1973);

- -

- Plants included in the Italian Red List [45,46].

To direct actions and measures more specifically, 5 classes of protection and related criteria were proposed, labeled as A, B, C, D, and E (Table 1). For each class, the desirable level of knowledge, the proposed conservation measures, the actions for their protection and management, and the appropriate monitoring activities were indicated (Table 3). The occurrence of even just one of the established criteria determines a plant’s belonging to the relevant class.

For the most threatened species or those included in classes A or B, we planned and carried out, from 2012 to 2023, field activities with the aim of tracing populations mentioned in the bibliography and monitoring their state of conservation.

During the monitoring of each species’ population, information about the localization, surface area, population size, habitat, main pressures/threats, and conservation measures have been collected. The populations monitored were analyzed according to the specific protocols developed in accordance with what was proposed by the SBI (Italian Botanical Society) and ISPRA (Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale) during the third report under art. 17 of the Habitats Directive [32].

The nomenclature of the plants included in the protection list follows the checklist of native Italian vascular flora [9] and the Italian checklist of bryophytes [47].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants13121675/s1, File S1: list of taxa of conservation interest in alphabetical order.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, F.C., F.B. and D.T.; field investigations, F.C., F.B. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C., F.B. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Abruzzo administrative region (PSR 2007–2013, Asse 3, Misura 3.2.3) budget chapter of PNGSL 11430.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the current study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the technicians of the National Park of Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga, all collaborators of the University of Camerino, who contributed to this work and the ex CTA (Coordinamento Territoriale per l’Ambiente—Forestry Police) and CUFA (Comando unità forestali, ambientali e agroalimentari—ForestryPolice) for helping us during field surveys. Special thanks go to our friends Jamila Da Valle and Giulio Zangari for the linguistic revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, U.; Kenney, S.; Breman, E.; Cossu, T.A. A multicriteria decision making approach to prioritise vascular plants for species-based conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 234, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arponen, A. Prioritizing species for conservation planning. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärtel, M.; Kalamees, R.; Reier, Ü.; Tuvi, E.-L.; Roosaluste, E.; Vellak, A.; Zobel, M. Grouping and prioritization of vascular plant species for conservation: Combining natural rarity and management need. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 123, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younge, A.; Fowkes, S. The Cape Action Plan for the Environment: Overview of an ecoregional planning process. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 112, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. IUCN Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 16. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Orsenigo, S.; Fenu, G.; Gargano, D.; Montagnani, C.; Abeli, T.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Bartolucci, F.; Carta, A.; Castello, M.; et al. Red list of threatened vascular plants in Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 155, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, L.; Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F. An inventory of vascular plants endemic to Italy. Phytotaxa 2014, 168, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bernardo, L.; Bouvet, D.; et al. A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 219–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Manzi, A.; Pedrotti, A. Liste Rosse Regionali Delle Piante d’Italia; Università degli Studi di Camerino—WWF Italia—S.B.I.: Camerino, Italy, 1997; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Manzi, A.; Pedrotti, A. Libro Rosso Delle Piante d’Italia; WWF Italia Ministero dell’Ambiente: Roma, Italy, 1992; p. 637. [Google Scholar]

- Vane-Wright, R.I.; Humphries, C.J.; Williams, P.H. What to protect?—Systematics and the agony of choice. Biol. Conserv. 1991, 55, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricsfalusy, V.V.; Trevisan, N. Prioritizing regionally rare plant species for conservation using herbarium data. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chape, S.; Harrison, J.; Spalding, M.; Lysenko, I. Measuring the extent and effectiveness of protected areas as an indicator for meeting global biodiversity targets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazco, S.J.E.; Bedrij, N.A.; Rojas, J.L.; Keller, H.A.; Ribeiro, B.R.; De Marco, P. Quantifying the role of protected areas for safeguarding the uses of biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 268, 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Darling, E.S.; Venter, O.; Maron, M.; Walston, J.; Possingham, H.P.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Barnes, M.; Brooks, T.M. Bolder science needed now for protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heywood, V.H. Conserving plants within and beyond protected areas—Still problematic and future uncertain. Plant Divers. 2019, 41, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H. In situ conservation of plant species—An unattainable goal? Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 63, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cecco, V.; Di Santo, M.; Di Musciano, M.; Manzi, A.; Di Cecco, M.; Ciaschetti, G.; Marcantonio, G.; Di Martino, L. The Majella National Park: A case study for the conservation of plant biodiversity in the Italian Apennines. Ital. Botanist 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, S.; Bonomi, C.; Bacchetta, G.; Bedini, G.; Borzatti, A.; Boscutti, F.; Carasso, V.; Carta, A.; Casavecchia, S.; Casolo, V.; et al. The RIBES strategy for ex situ conservation: Conventional and modern techniques for seed conservation. Fl. Medit. 2022, 32, 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Di Martino, L. Life Floranet. La Salvaguardia Delle Piante di Interesse Comunitario dell’Appennino Centrale; Poligrafica Mancini: San Giovanni Teatino, Italy, 2021; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Callmander, M.W.; Ghazaly, U.M.; Kamel, M. Conservation status of the Endangered Nubian dragon tree Dracaena ombet in Gebel Elba National Park, Egypt. Oryx 2015, 49, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, R.; Adamo, M.; Cribb, P.J.; Bartolucci, F.; Sarasan, V.; Alessandrelli, C.; Bona, E.; Ciaschetti, G.; Conti, F.; Di Cecco, V.; et al. Combining current knowledge of Cypripedium calceolus with a new analysis of genetic variation in Italian populations to provide guidelines for conservation actions. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoang, S.; Baas, P.; Keβler, P.J.A. Uses and Conservation of Plant Species in a National Park—A Case Study of Ben En, Vietnam. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciani, D.; Geri, F.; Agostini, N.; Gonnelli, V.; Lastrucci, L. Role of a geodatabase to assess the distribution of plants of conservation interest in a large protected area: A case study for a major national park in Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Bhat, J.A.; Negi, V.S.; Satish, K.V.; Siddiqui, S.; Pant, S. Conservation Priority Index of species, communities, and habitats for biodiversity conservation and their management planning: A case study in Gulmarg Wildlife Sanctuary, Kashmir Himalaya. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 995427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca, G.; Cueto, M.; Martínez-Lirola, M.J.; Molero-Mesa, J. Threatened vascular flora of Sierra Nevada (Southern Spain). Biol. Conserv. 1998, 85, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F. The vascular flora of Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga National Park (Central Italy). Phytotaxa 2016, 256, 1–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F. The Vascular Flora of the National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise (Central Italy). An Annotated Checklist; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thiers, B.M. Strengthening Partnerships to Safeguard the Future of Herbaria. Diversity 2024, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catonica, C.; Tinti, D.; De Bonis, L.; Di Santo, D.; Calzolaio, A.; De Paulis, S. Carta della Natura per la zonazione del Piano del Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga. Reticula 2017, 16, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ercole, S.; Fenu, G.; Giacanelli, V.; Pinna, M.S.; Abeli, T.; Aleffi, M.; Bartolucci, F.; Cogoni, D.; Conti, F.; Croce, A.; et al. The species-specific monitoring protocols for plant species of Community interest in Italy. Plant Sociol. 2017, 54, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F. Specie a rischio in Abruzzo. Elenco delle piante di interesse conservazionistico. In La Biodiversità Vegetale in Abruzzo. Tutela e Conservazione del Patrimonio Vegetale Abruzzese; Console, C., Conti, F., Contu, F., Frattaroli, A.R., Pirone, G., Eds.; One Group: l’Aquila, Italy, 2012; pp. 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F.; D’Orazio, G.; Londrillo, I.; Manzi, A.; Scassellati, E.; Tinti, D. Il Centro Ricerche Floristiche dell’Appennino (Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga—Università di Camerino). Inf. Bot. Ital. 2005, 37, 322–323. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Bartolucci, F.; Tinti, D.; Manzi, A. Guida Fotografica Alle Piante del Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti Della Laga. Compendio Della Flora Vascolare; Fast Edit s.r.l.: Acquaviva Picena, Italy, 2019; p. 936. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci, F.; Domina, G.; Argenti, C.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, D.; Barberis, G.; Bertolli, A.; Bolpagni, R.; et al. Notulae to the Italian native vascular flora: 12. Ital. Botanist 2021, 12, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěpánek, J.; Kirschner, J. Taraxacum sect. Erythrocarpa in Europe in the Alps and eastwards: A revision of a precursor group of relicts. Phytotaxa 2022, 536, 7–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Falcinelli, F.; Giacanelli, V.; Santucci, B.; Miglio, M.; Manzi, A.; Bartolucci, F. New floristic data of vascular plants from central Italy. Nat. Hist. Sci. 2023, 10, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, A.; Berardi, D.; Ciaschetti, C. Prime segnalazioni di Anacamptis berica in Abruzzo e in Molise. GIROS Orchid. Spontanee D’Europa 2023, 66, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Cangelmi, G.; Da Valle, J.; De Santis, E.; Giacanelli, V.; Gubellini, L.; Hofmann, N.; Masin, R.R.; Miglio, M.; Palermo, D.; et al. Additions to the vascular flora of Italy. Fl. Medit. 2023, 33, 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Slovák, M.; Melichárková, A.; Štubňová, E.G.; Kučera, J.; Mandáková, T.; Smyčka, J.; Lavergne, S.; Passalacqua, N.G.; Vďačný, P.; Paun, O. Pervasive Introgression During Rapid Diversification of the European Mountain Genus Soldanella (L.) (Primulaceae). Syst. Biol. 2022, 72, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolucci, F.; Ranalli, N.; Bouvet, D.; Cancellieri, L.; Fortini, P.; Gestri, G.; Di Pietro, R.; Lattanzi, E.; Lavezzo, P.; Longo, D.; et al. Contribution to the floristic knowledge of northern sector of Gran Sasso d’Italia (National Park of Gran Sasso and Laga Mountains): Report of the excursion of the “Floristic Group” (S.B.I.) held in 2010. Ital. Botanist 2012, 44, 355–385. [Google Scholar]

- Miguez, M.; Bartolucci, F.; Jiménez-Mejías, P.; Martín-Bravo, S. Re-evaluating the presence of Carex microcarpa (Cyperaceae) in Italy based on herbarium material and DNA barcoding. Plant Biosyst. 2022, 156, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Tinti, D.; Bartolucci, F.; Scassellati, E.; Di Santo, D.; Fanelli, C.; Iocchi, M.; Meister, J.; Pavoni, P.; Torcoletti, S. Banca dati della flora vascolare d’Abruzzo: Lo stato dell’arte. Ann. Bot. (Rome) 2010, 43, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Montagnani, C.; Gargano, D.; Peruzzi, L.; Abeli, T.; Ravera, S.; Cogoni, A.; Fenu, G.; Magrini, S.; Gennai, M.; et al. Lista Rossa Della Flora Italiana. 1. Policy Species e Altre Specie Minacciate; Stamperia Romana: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Orsenigo, S.; Gargano, D.; Montagnani, C.; Peruzzi, L.; Fenu, G.; Abeli, T.; Alessandrini, A.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; et al. Lista Rossa Della Flora Italiana. 2 Endemiti e Altre Specie Minacciate; Stamperia Romana: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aleffi, M.; Tacchi, R.; Poponessi, S. New Checklist of the Bryophytes of Italy. Cryptogam. Bryol. 2020, 41, 147–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).