Abstract

The need for integrating geospatial information (GI) data from various heterogeneous sources has seen increased importance for geographic information system (GIS) interoperability. Using domain ontologies to clarify and integrate the semantics of data is considered as a crucial step for successful semantic integration in the GI domain. Nevertheless, mechanisms are still needed to facilitate semantic mapping between GI ontologies described in different natural languages. This research establishes a formal ontology model for cross-lingual geospatial information ontology mapping. By first extracting semantic primitives from a free-text definition of categories in two GI classification standards with different natural languages, an ontology-driven approach is used, and a formal ontology model is established to formally represent these semantic primitives into semantic statements, in which the spatial-related properties and relations are considered as crucial statements for the representation and identification of the semantics of the GI categories. Then, an algorithm is proposed to compare these semantic statements in a cross-lingual environment. We further design a similarity calculation algorithm based on the proposed formal ontology model to distance the semantic similarities and identify the mapping relationships between categories. In particular, we work with two GI classification standards for Chinese and American topographic maps. The experimental results demonstrate the feasibility and reliability of the proposed model for cross-lingual geospatial information ontology mapping.

1. Introduction

The vision of a “Digital Earth” articulated by US Vice President Al Gore [1,2,3] has contributed significantly to the growth in global geospatial information (GI) on physical and social environments. However, how to query, retrieve, and manipulate those data from heterogeneous sources has challenged the GI community [2,3,4,5]. Thus, an approach to integrating GI data from various heterogeneous sources has found increased importance [6].

A data integration process is not as simple as joining several systems because any effort at information sharing runs into the problem of semantic heterogeneity [7]. Semantic heterogeneity occurs when enabling interoperability across geographic information systems (GIS) [8,9,10,11] because GIS are often designed to address data from highly distributed, multidisciplinary, and cross-lingual data sources with different application demands [12]. Clarifying the semantics of data is therefore a crucial step toward successful data integration [13]. To achieve this, domain ontologies are built as a mediator to exchange information in such a way that the precise meaning of the data (i.e., semantics) is readily retrievable beyond simple keyword matching via knowledge representation languages and reasoning [7,13,14,15]. Thus, ontology engineering has been regarded as an effective means of providing seamless connection between component GIS at the semantic level [8,12,16].

While the GI community widely acknowledges the utility of ontology technologies, two main problems need to be solved for GI ontology engineering and sharing are as follows: (1) traditional ontology research and technologies focusing on terminology and schema cannot answer the question surrounding how to engineer GI ontologies and integrate them with GIS or Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI) [6]; and (2) mechanisms still need to be explored for GI ontology mapping in cross-lingual environments to facilitate semantic integration between GI ontologies described in different natural languages [17,18,19,20].

The reason for the first problem is that GI features and categories are a product of spatial cognition and social convention; thus, the ontology engineering works in GI domains are different from others, in which the location, topology, mereology, and other spatial relations play a major role in the identification and representation of GI semantics [14]. For example, from a feature-driven ontology perspective, the geographic categories “river” and “bank” should be specified into different classes, and normally, the spatial relation “adjacent-to” between these two categories is missing. Moreover, geographic and non-geographic entities are ontologically distinct in a number of ways [21]. To enhance the semantic expressiveness and overcome the issue of semantic heterogeneity during the GI ontology engineering process, the spatial-related characteristics of GI categories must be considered to enrich the spatial-related semantics of the given ontology.

Although a majority of current GI ontologies have been developed in English with English vocabularies, the amount of multilingual content on the Semantic Web and thus the number of vocabularies/ontologies in multiple languages continue to grow [22]. Thus, methods for matching vocabularies across languages have become increasingly more important for promoting the accessibility of the data in multiple languages by end users [23]. As a motivating scenario, if a user wants to query the water level data along the Mekong River (The seventh longest river in the world, covering six different countries—Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and China—and the official languages of each country are different), there are several data providers offering the related GI data via their national GIS in their native natural languages. This situation has generated a substantial challenge to integrating highly heterogeneous GI data across natural language barriers.

The purpose of this study is to establish a formal ontology model for cross-lingual geospatial information ontology mapping. Starting from two GI classification standards with different natural languages—Chinese and English(for the sake of simplicity and clarity, this study was restricted to the “surface water” categories from these two standards)—a set of semantic primitives are extracted from the free-text definition of the categories in the standards by applying Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. Then, an ontology-driven approach is used, and the formal ontology model is established to formally represent these semantic primitives using semantic statements, in which the spatial-related properties and relations are considered as crucial statements for the representation and identification of the semantics of the GI categories. To overcome the natural language barrier, the statements in Chinese are translated into English by using machine translation tools, and the mapping relationships between statements are determined within an English context, which then serve as the basis for the similarity calculation between categories in different GI ontologies. Finally, a similarity calculation algorithm is designed to distance the semantic similarity between GI categories in different ontologies, and the final mapping relationships between pairs of categories are determined based on calculated similarity values. The contributions of the proposed approach include (1) the construction of the spatial-related semantic properties and relations to serve the requirement of the presentation and identification of the spatial characteristics of the GI categories and (2) the algorithms of GI ontology mapping in a cross-lingual environment based on formally represented and comparable semantic statements.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the related works in the literature. Then, the main procedure of our methodology is presented in Section 3. Next, a case study demonstrating the application of our method is shown in Section 4. Finally, conclusions are drawn, and future works are noted.

2. Related Works

2.1. Semantic Interpretation

Knowledge acquisition (KA) is a broad field that encompasses the processes of extracting, creating, and structuring knowledge from heterogeneous resources [24]. Semantic interpretation (SI) for KA is defined as the composition of two sub-processes: the extraction of semantic primitives from the free-text definition in ontologies and semantic enrichment based on the extracted semantic primitives.

The research on semantic primitive extraction builds on a large body of works within the fields of Natural Language Processing (NLP) [25]. NLP and text mining are research fields aimed at exploiting rich knowledge resources with the goal of understanding, extracting and retrieving semantic information from unstructured written text. Knowledge resources that have been used for these purposes include the entire range of terminologies, including lexicons, controlled vocabularies, thesauri, and ontologies [26,27]. Although numerous methods and algorithms have been developed recently (such as symbolic, statistical, and hybrid approaches) [26], a fully automated algorithm for semantic extraction using NLP techniques seems unachievable, and a manual process as an assistant is normally inevitable.

For semantic enrichment, authors in [28,29] proposed a systematic methodology to explore and identify semantic information provided by categories in geographic ontologies, in which the semantic representations of categories are enriched with a set of semantic properties and relations to reveal similarities and heterogeneities between these categories. Authors in [30] presented an axiomatic formalization of a theory of top-level relations (parthood relations, sub-universal relations, and cross-categorical relations) between three categories of geospatial-related entities, namely, individuals, universals, and collections. In addition, they demonstrated how a more exact understanding helps to overcome the semantic heterogeneous problems in the information integration process. In [13], the semantics of a concept in GI ontologies were presented using an extendable and structural definition framework composed of a number of RDF triple statements, and a comparison algorithm was designed to determine the semantic relationships of concepts between different domains. The primary objective of these studies was to extract and represent the semantics of concepts/entities based on structural common vocabularies, which make the semantics of the concepts/entities comparable. However, the structural common vocabularies in these works are determined by domain experts manually; thus, the objectivity and automation of the algorithms (avoiding ad hoc manual procedures and subjective experts’ knowledge) remain quite limited.

2.2. Ontology Mapping

Mapping relationship discovery for ontologies has attracted considerable attention in recent years. Various approaches based on processes to find similarities between different but related ontologies have emerged [31]. With respect to the literature specifically oriented toward geospatial information (GI) ontologies, authors in [32] performed an analysis of the different models of semantic similarity measurement and evaluated these models with respect to the particular requirements of geospatial data. Authors in [7,33] systematically surveyed several of the most recent and often-referenced works on integrating GI and GI ontology mapping by applying comparison criteria, such as logical inference, mapping approaches, degree of automation, and geospatial relativity. In addition, a general conclusion is proposed that, for the ontology mapping task, the use of formal ontologies and, consequently, the use of reasoners should be mandatory.

In recent years, Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) has been proposed for GI ontology mapping in a web environment. Authors in [34,35] devised a mechanism for computing the semantic similarity of the Open Street Map (OSM) geographic classes using volunteered lexical definitions to alleviate the semantic gap between different VGI producers. Another set of studies focused on introducing an artificial neural network approach to simulate the human perception and measure the semantic similarity between spatial entities for the purpose of improving the automaticity of the ontology mapping process [36,37].

All these proposals, combining the use of different models of semantic similarity measurement, have emerged to provide solutions to existing GI ontology mapping problems in English environments. However, the semantic web and ontology engineering have experienced significant advancements in standards and techniques, and increasingly more domain ontologies and localization content in the semantic web are described using native natural languages [23]. There is a pressing need for cross-lingual ontology mapping mechanisms in the GI community that are designed to reconcile semantics of different ontologies in multilingual environments and to improve the accessibility of various GI ontologies across language barriers [38].

Author in [39] groups the existing cross lingual ontology mapping(CLOM) algorithms into following categories: manual processing [40,41,42], corpus-based approach [43], linguistic enrichment [44], indirect alignment composition [45], and translation-based approach [39,46]. Compared to these CLOM approaches, translation-based CLOM is currently a very popular approach that is exercised by several researchers [47,48,49,50], which is enabled by translations achieved through the use of machine translation (MT) tools, bilingual/multilingual thesauri, dictionaries etc. Typically, these approaches rely only on string-based lexical comparisons of entity names and descriptions [51,52,53,54], while the comparisons between semantic interpretation, e.g., model-theoretic semantics of entities are missing.

3. Methodologies

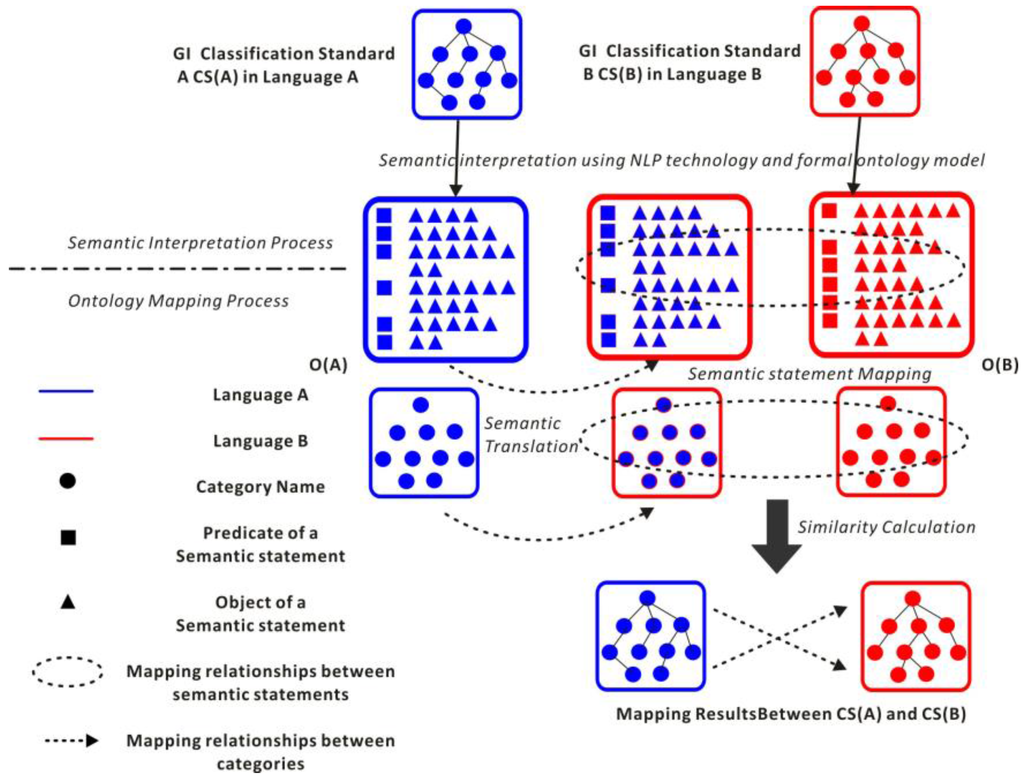

The main procedure for our methodologies is divided into two sub-processes, as shown in Figure 1. In the semantic interpretation process, two GI formal ontologies, namely, OA and OB, are established from the free-text definition of the corresponding classification standards with different natural languages. In the ontology mapping process, all the category names and semantic statements in OA are translated from LA into LB, and the mapping relationships between category names and semantic statements are determined within the same language context, which then serve as the basis for the similarity calculation between categories in different GI ontologies. Finally, a similarity calculation algorithm is designed, and the final mapping results between pairs of categories in different classification standards are determined.

Figure 1.

Main procedure for our methodologies.

3.1. Semantic Interpretation

3.1.1. Semantic Primitive Extraction

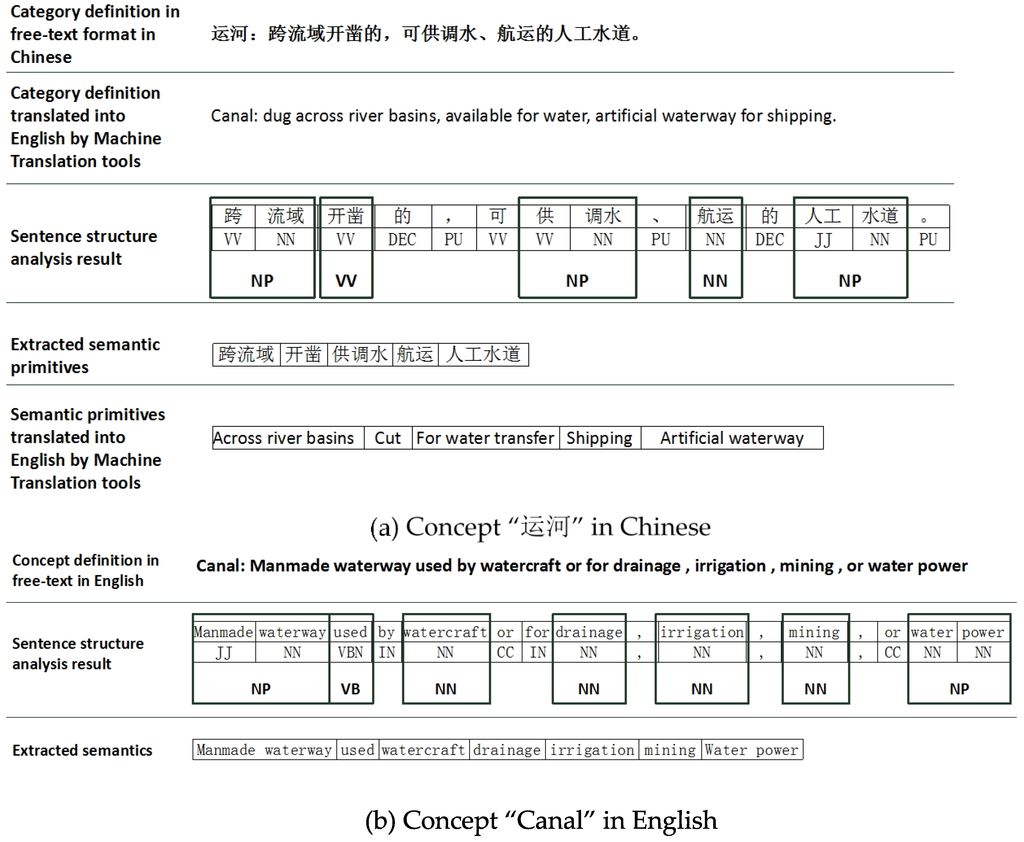

In geospatial information repositories, free-text definitions are often the primary and only available objective descriptions of categories. Semantic primitives are syntactic and lexical patterns in the free-text definition and can be extracted using NLP tools [55]. The fields of studies on NLP have developed methods and algorithms for information retrieval and extraction from free-text knowledge resources. The methodology adopted here for analyzing definitions and extracting semantic primitives was introduced by [56]. In this research, the lexical patterns of nominal phrases and verb phrases are considered as semantic primitives. An example is illustrated in Figure 2, and the main steps of the process are as follows:

- One category definition in free-text format is chosen as the input natural language material;

- Word segmentation is performed to split the whole sentence into individual words;

- Words are categorized and tagged into their parts-of-speech tag sets (see Table 1 and Table 2) and labeled accordingly;

Table 1. Summary of the Penn Treebank Part-of-Speech Tag sets in English.

Table 1. Summary of the Penn Treebank Part-of-Speech Tag sets in English. Table 2. Summary of the Penn Treebank Part-of-Speech Tag sets in Chinese.

Table 2. Summary of the Penn Treebank Part-of-Speech Tag sets in Chinese. - The nominal phrases and verb phrases are chunked, and the sentence structure is analyzed to extract lexical patterns as the semantic primitives.

Figure 2.

Extract the semantic primitives from the free-text definitions by applying NLP tools in Chinese and English.

3.1.2. Construction of the Formal Ontology Model

From Wikipedia an “ontology in information science“ is a formal naming and definition of the types, properties, and interrelationships of the concepts that really or fundamentally exist for a particular domain of discourse. It is thus a practical application of philosophical ontology, with taxonomy. In addition, a domain ontology (or domain-specific ontology) represents concepts that belong to a general domain. Thus, for a formal representation [57,58], the domain ontology (denoted by ODomain), and concepts in the domain could be summarized by Equations (1)–(3).

In Equation (1), S(CDomain) represents the set of concepts in a domain, and the semantics of each concept in the domain are categorized into different groups, namely, S(HC), S(RC), and S(PC); S(HC) represents the set of the hierarchical relations about the taxonomic information in ODomain, S(RC) represents the set of other interrelations between these concepts, and S(PC) represents the set of the semantic properties belong to the concepts in this domain.

In Equation (2), the semantics of a concept in the domain are considered as the composition of terminology of this concept (denoted by TC) and structural definition of this concept (denoted by DC). Unlike the free-text format of definition, DC commonly consists of the semantic properties of the concept (PC), the hierarchical relation (HC) and other interrelations (RC) between this concept and other concepts in the domain. Thus, from Equations (2) and (3), a certain concept in the domain, CDomain can be deduced as a function of TC, RC, HC, and PC in Equation (4)

in which RC, HC, PC are used to represent the semantics of this concept, and belong to S(RC), S(HC), S(PC), respectively.

Considering the situation in the GI domain, we use the word “category” instead of “concept”. Because the semantic characteristics of the GI category are highly correlated in space and time [59], the spatial- and temporal-related semantic properties and relations should be included in the model as crucial vocabularies for the representation and identification of the semantics of the GI categories. Thus, the GI ontology OGI and the semantics of a certain category CGI in OGI can be represented as Equations (5) and (6):

In Equation (5), S(TC) represents the set of the category names in OGI; S(RS), S(RT) represent the set of the spatial-related and temporal-related semantic relations between categories; S(HC)represents the set of hierarchical relations; S(PS), S(PT) represent the set of the spatial-related and temporal-related semantic properties belong to the categories in OGI; and S(RC), S(PC) represent the set of other semantic properties and relations in OGI. And in Equation (6), Vx represents the values of certain semantic properties/relations of CGI; TC, RS, RT, RC, HC, PS, PT, PC are used to represent the semantics of CGI, and belong to S(TC), S(RS), S(RT), S(RC), S(HC), S(PS), S(PT), S(PC), respectively.

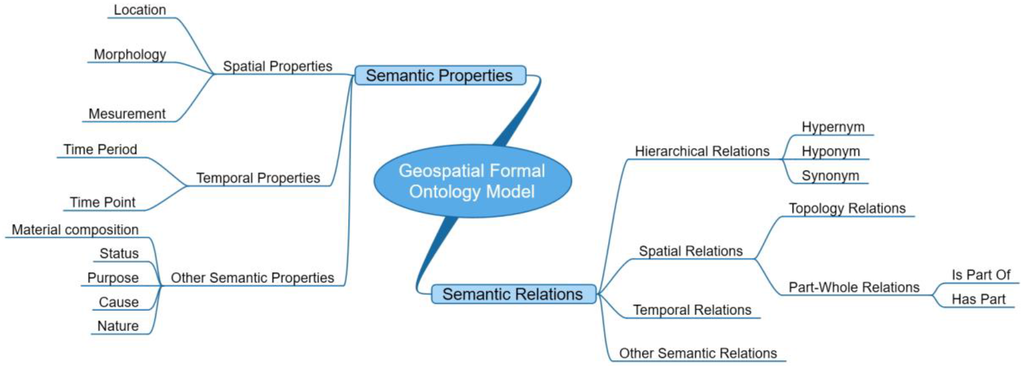

In order to solve the problems of geographic representation, authors in [60] distinguished three main theoretical tools that are required for the purposes of developing an overall formal theory of spatial representation, namely, mereology, location, and topology, these theoretical tools are selected as the basis for defining spatial-related semantics in our formal ontology model. In addition, geographic entities in reality is essentially dynamic, authors in [61] pointed out that a good ontology must be capable of accounting for spatial reality both synchronically (as it exists at a time) and diachronically(as it unfolds through time), thus the “time point” and “time period” properties should be used to describe dynamic characteristics of the geographic entities in our model. Moreover, in order to specify semantic relations and properties used in geographic definitions, authors in [28] analyzed several geographic ontologies and identified patterns which were systematically used to express specific semantic relations and properties, including hierarchical relations, part-whole relations and neighborhood relations, and semantic properties such as purpose, nature, material, size, and so on.

Based on previous researches and our formal ontology model in Equation (5), the semantic property and relation types in our model are subdivided and shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Semantic property and relation groups in the Geospatial Formal Ontology Model.

3.1.3. Transformation from Semantic Primitives to Formal Ontology Model

In order to make the semantic primitives structural and comparable, domain experts are responsible for analyzing these semantic primitives and transforming them into different groups of semantic properties/relations in our geospatial formal ontology model. The famous triple statement Subject-Predicate-Object and the web ontology language (OWL) are selected as the basis for presenting the semantic properties/relations and their values in a machine-readable manner. The Subject represents a CGI in OGI; the Predicate is a certain semantic property or semantic relation type illustrated in Figure 3, in which all of the semantic relations are presented by object property and the Object in these semantic relations is another CGI in OGI or an “owl:class” object type, while most of the semantic properties are presented by object property too, and a few of them are presented by datatype property in OWL syntax, and the Object in these semantic properties is a “rdfs:literal” datatype. The following rules are adopted to handle the formalization process:

- (1)

- The GI category can be represented by a number of semantic relations/properties; however, the number of semantic relations/properties involved should be minimized to avoid redundancy.

- (2)

- Not every GI category must cover all semantic relations/properties in the model. The situation whereby two different categories use the same set of semantic relations/properties to represent their semantics cannot be guaranteed.

- (3)

- The semantic information of a certain category in our model is the combination of different semantic relations-properties and their values. This combination should represent all the semantic information of the category and be able to distinguish the different geospatial categories within and beyond domain ontologies to avoid ambiguity.

- (4)

- The hypernym, hyponym, and synonym relations should be included in the hierarchical relation group. If category A is a hyponym of category B, A must inherent all the semantic properties/relations of B to retain semantic consistency.

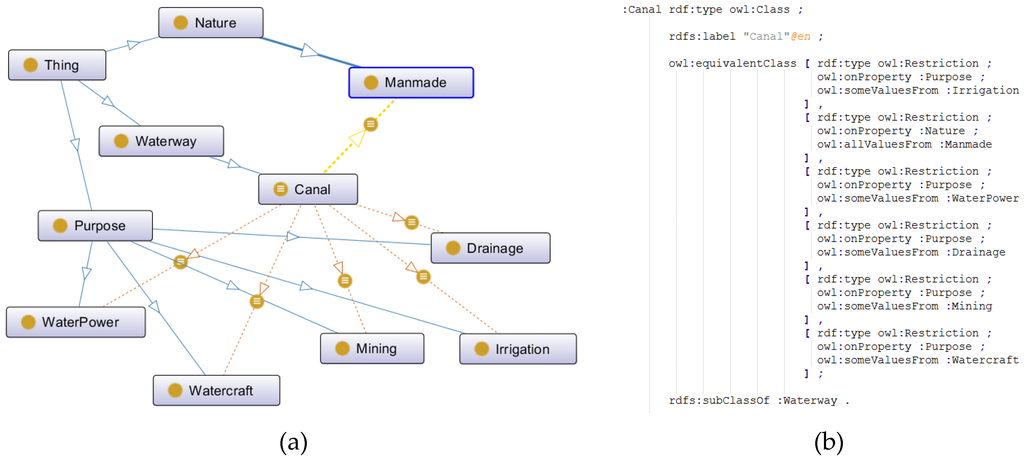

According to the above-mentioned rules, the semantic primitives can be specified into these properties/relations types as structure statements for identification and representation of the GI categories. For example, the free-text definition of the “canal” category in English is “manmade waterway used by watercraft or for drainage, irrigation, mining, or water power”. In addition, the semantic primitives of the “canal” category are extracted by applying NLP tools to the set of phrases including “manmade waterway”, “used”, “watercraft”, ”drainage”, ”irrigation”, ”mining”, and “water power”. Then, transforming these semantic primitives into the proposed formal ontology model, the semantics of the category “canal” can be represented as a set of several semantic statements as follows:

In addition, the representation in OWL format is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Representation of the category “canal” in OWL format: (a) The OntoGraf view in Protégé and (b) the semantic statement presentation in turtle file format.

3.2. Ontology Mapping Algorithms

3.2.1. Semantics Translation

Assume that we have formal ontologies OA, OB presented in different natural languages, namely, language A (LA) and B (LB), respectively. According to the geospatial formal ontology model introduced in Section 3.1.2, the semantics of ontologies OA and OB consist of category name sets S (CNA) and S (CNB) and semantic statement sets S (SSA) and S (SSB), labeled in different natural languages, in which the semantic statement consists of semantic property/relation types (as illustrated in Figure 3 in Section 3.1.2) and their corresponding values. In order to cross the natural language barrier between OA and OB, algorithm 1 illustrates the process of semantics translation between LA and LB:

| Algorithm 1. Semantics Translation. |

| 1: Input: Formal ontologies OA(S(CNA), S(SSA)) in LA |

| 2: Output: Translation candidate result set of the semantics in OA, O’A (S(TC(CNA)), S(TC(SSA-object))) in |

| 3: LB. |

| 4: Symbols: |

| 5: S(TC(CNA))—Translation candidate result set of S(CNA) in LB. |

| 6: S(TC(SSA))—Translation candidate result set of S(SSA) in LB. |

| 7: ssA-object—The Object part of the semantic statement ssA. |

| 8: 1:for each category name cnA in S(CNA), translate cnA in LA into cnA’ in LB by using different Machine Translation (MT) web services (Google Translator API at” http://translate.google.cn/”, Bing Translator API at” http://www.bing.com/translator/?ref=SALL&mkt=zh-CN”, and Baidu Translator API at ”http://fanyi.baidu.com/?aldtype=16047#zh/en/”), collect all of the translation results about cnA, into the translation candidate results TC(cnA), and store all of the category name translation candidate results into the translation candidate set S(TC(CNA)); |

| 9: 2:for each semantic statement ssA in S(SSA), according to the OWL triple statement syntax, it can be subdivided into three part, Subject, Predicate, and Object, translate ssA-object in LA into ssA’-object in LB by using different Machine Translation (MT) web services, collect all of the translation results about ssA-object, into the translation candidate results TC(ssA-object), and store all of the semantic statements translation candidate results into the translation candidate set S(TC(SSA-object)). |

| 10: Take the “运河” category in Chinese as an example, the semantic primitives of the “运河” category are extracted by applying NLP tools to the set of phrases including “跨流域”, “开凿”, “供调水”, ”航运”, ”人工水道”. Then, transforming these semantic primitives into the proposed formal ontology model, the semantics of the category “运河”can be represented as a set of several semantic statements as follows: |

| 11:

|

| 12: And the semantics translation result of C运河 in English is as follows: |

| 13:

|

3.2.2. Semantic Statement Mapping

To determine the mapping relationships between categories in different GI ontologies, the mapping relationships at the semantic statement level should be determined first because the semantic statement presents the most detailed semantic characteristics of the compared categories. Once their relationships are determined, the similarity between categories can be determined quantitatively. Algorithm 2 shows the comparison process for category names and semantic statements between OA and OB. In addition, all the mapping results M(OA, OB) are stored as the basis for the similarity calculation between the concepts in different GI ontologies.

| Algorithm 2. Semantic Statement Mapping. |

| 1: Input: O’A (S(TC(CNA)), S(TC(SSA-object))) in LB, Formal ontologies OB(S(CNB), S(SSB)) in LB |

| 2: Output: Mapping result set M(OA, OB) about category names and semantic statements between 3: OA and OB. |

| 4: Symbols: |

| 5: T(ss)—semantic property/relation types for a certain semantic statement ss. |

| 6: M(OA’, OB)—mapping relationships about category names and semantic statements between OA’ |

| 7: and OB. |

| 8: 1: for each category name cnA in S(CNA), find the translation candidate results of cnA, TC(cnA), |

| 9: 2: for each translation candidate tc(cnA) in TC(cnA), search S(CNB) in OB, find the matched |

| 10: category name cnB in S(CNB) by applying Equation(10), |

| 11: 3: If there is a translation candidate tc(cnA) has the mapping relationship “exact match” |

| 12: with cnB, store the mapping result m(cnA, cnB, ‘exact match’) in M(OA, OB); |

| 13: 4: else If there is a translation candidate tc(cnA) has the mapping relationship |

| 14: “close match” with cnB, store the mapping result m(cnA, cnB, ‘close match’) in M(OA, OB); |

| 15: 5: for each semantic statement ssA in S(SSA), find the translation candidate results of ssA-object, |

| 16: TC(ssA-object), |

| 17: 6: for each translation candidate tc(ssA-object) in TC(ssA-object), search S(SSB-object) in OB, |

| 18: find the matched semantic statement Object, ssB-object in S(SSB) by applying Equation(10), |

| 19: 7: If there is a translation candidate tc(ssA-object) has the mapping relationship “exact |

| 20: match” with ssB-object, and T(ssA) equals T(ssB), store the mapping result m(ssA, ssB, ‘exact |

| 21: match’) in M(OA, OB); |

| 22: 8: else If there is a translation candidate tc(ssA-object) has the mapping relationship “close |

| 23: match” with ssB-object, and T(ssA) equals T(ssB), store the mapping result m(ssA, ssB, ‘close |

| 24: match’) in M(OA, OB). |

| 25:

|

3.2.3. Similarity Calculation

Given two categories, Ca and Cb in the formal ontologies OA and OB, respectively, based on the M(OA, OB), the semantic similarity between Ca and Cb can be calculated using algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3. Similarity Calculation. |

| 1: Input: Categories Ca(CNa, SSa) in OA, Cb(CNb, SSb) in OB and mapping relationship set M(OA, OB) |

| 2: about category names and semantic statements between OA and OB. |

| 3: Output: Semantic similarity value between Ca and Cb, Sim(a, b). |

| 4: Symbols: |

| 5: Cot(SSa)—the number of semantic statements in SSa. |

| 6: Cot(SSb)—the number of semantic statements in SSb. |

| 7: m(CNa, CNb)—mapping relationship between CNa and CNb. |

| 8: m(SSa(i), SSb(j))—mapping relationship between SSa(i) in Ca and SSb(j) in Cb. |

| 9: Pt(SSab)—the sum of the match point value between SSa and SSb. |

| 10: Pt(CNab)—the match point value between CNa and CNb. |

| 11: 1: for each semantic statement SSa(i) in SSa, find the matched semantic statement SSb(j) in SSb |

| 12: based on the mapping relationship set M(OA, OB); |

| 13: If m(SSa(i), SSb(j)) = “exact match”, then the match point value between SSa(i) and SSb(j) is assigned 1; |

| 14: Else if m(SSa(i), SSb(j)) = “close match”, then the match point value between SSa(i) and SSb(j) is |

| 15: assigned 0.5; |

| 16: 2: Record the sum of the match point values between SSa and SSb as Pt(SSab) and the number of |

| 17: matched statements between SSa and SSb as Cot(SSab); |

| 18: 3: find the mapping relationship between CNa and CNb based on M(OA, OB), |

| 19: If m(CNa, CNb) = “exact match”, then the match point value between CNa and CNb is assigned 1; |

| 20: Else if m(CNa, CNb) = “close match”, then the match point value between CNa and CNb is |

| 21: assigned 0.5; |

| 22: 4: Record the match point value between CNa and CNb as Pt(CNab); |

| 23: 5: the similarity of categories Ca and Cb can be calculated using the following equation: |

| 24:

|

| 25: In addition, the mapping relationships between category pairs Ca and Cb, namely, MR(a, b), can |

| 26: be determined using the following equation: |

| 27:

|

4. A Case Study

4.1. Study Material

To illustrate the methodologies, two different classification standards in two corresponding natural languages have been selected for use in the mapping process. CSC is developed based on the national topographic map standards in China (Standards of “Cartographic symbols for national fundamental scale maps” and “Specifications for feature classification and codes of fundamental geographic information”). CSA is developed by the U.S. Geological Survey in America (http://cegis.usgs.gov/ttl/USTopographic.ttl). Both standards are digital literature materials; the category names and their free-text definitions are provided as source information for our experiment. In addition, for the sake of simplicity and clarity, our study was restricted to the “surface water” categories from these two classification standards. Table 3 briefly lists the characteristics of these two selected dataset, with detailed explanations as follows:

- (1)

- Both standards have their own classification system to address the categories of “surface water”. The categories in CSC are organized using a four-level hierarchy with six major categories. By contrast, the categories in CSA are organized by a four-level hierarchy with 81 major categories, which means that the hierarchical structure of CSA does not closely match that of CSC.

- (2)

- The free-text definitions in both standards are used as category definitions.

- (3)

- The number of categories in CSC is 74, and the number of concepts in CSA is 92; thus, the CSA covers more category types than does CSC.

- (4)

- The natural language in CSC is Chinese, whereas the natural language in CSA is English, which means that there is a natural language barrier between these two GI classification standards.

Table 3.

Characteristics of CSC and CSA.

4.2. Results

The well-defined category definitions in both CSC and CSA serve as the basis for our study. The Web Ontology Language (OWL) API is integrated to facilitate the implementation of the proposed algorithm in Eclipse with the JAVA language, and the experiment results are as follows.

4.2.1. Semantic Statement Mappings

The semantic primitives are extracted using the Stanford Natural Language Processing Tools (http://nlp.stanford.edu/software/) and are transformed into the formal ontologies OC and OA with the set of category names and semantic statements by domain experts and encoded by the OWL via Protégé. Using the semantic statement mapping algorithm introduced in Section 3.2.2, the number of mapping relationships between the statements in OC and OA is recorded, and the mapping results for different semantic property/relation types are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Condition of the mapping statements between OC and OA.

The total number of semantic statements in OC is 142, and the total number of such statements in OA is 181. In addition, the total mapping rate of the semantic statements between OC and OA is 28.69%. The details of the mapping relationships between semantic statements in each type can be found in Appendix.

For the semantic statement about the semantic property types, the most matched type is “purpose”. This is because the semantic property type of “purpose” is used to represent the manmade category, which includes “ditch”, “canal”, and “dam”, and the free-text definitions in both the Chinese and American classification standards for these types of categories are very similar. The semantic information about purpose and functionality are considered as the crucial characteristics of the categories. It is easy to understand that the semantic property type “nature” has the highest mapping rate, namely, 100%, because there are only two values for this type of semantic statement, namely, “natural” and “manmade”, in both OC and OA. Considering the semantic property type “location”, there are seven semantic statements in OC, and eight in OA, but the mapping rate of this type is extremely low(only one semantic statement is mapped with mapping rate 7.14%). That’s because the semantic property type “location” is used to describe the region environment where certain geographic category is at, and a lot of the categories in OA are bay-related or glacier-related, such as “glacier”, “ice cap” and “iceberg tongue” with semantic property value of “location”, “mountainous area”, “regions of perennial frost”, and “coast”, respectively, and there are no such categories in OC. For the semantic statement about the relation types, the most matched type is “spatial relation”, which is also the type with the highest mapping rate, indicating that the spatial-related relations play a major role in the identification and representation of GI semantics.

4.2.2. Similarity Calculation and Category Mappings

The similarities between concepts are calculated using the semantic statement mapping relationships and Algorithm 3 proposed in Section 3.2.3. Three typical examples of the mapping results between categories are chosen for further discussion. Table 5 shows the names and free-text definitions of the compared category pairs. In addition, the corresponding semantic statements, calculated similarity values and final mapping relationships between these category pairs are presented in Table 6.

Table 5.

Names and free-text definitions of the compared concept pairs.

Table 6.

Example of categories definitions and similarity calculation.

Example 1: Concept pair of “spillway” in OC and “spillway” in OA

These two concepts are comparable because the mapping relationship between their concept names is “exact match”. Because their concept names and four semantic statements are matched (detailed mapping relationships are illustrated in Table 6, line 1 and 2), the second condition in Equation (9) is used to calculate the final similarity between “spillway” in OC and “spillway” in OA. The similarity value between these two concepts is calculated as 0.78; thus, the mapping relationship between these two concepts is “close match”. This example demonstrates the simplest case for the calculation of the semantic similarity between concepts.

Example 2: Concept pair of “arroyo (dry river)” in OC and “wash” in OA

In this example, the mapping relationship between the concept name of “arroyo (dry river)” and “wash” cannot be determined based on the mapping algorithm in Section 3.2.1. However, the similarity value between these two concepts is higher than the value in example (1). This is because all the semantic statements used to represent the semantic meaning of these two concepts are correspondingly matched (detailed mapping relationships are illustrated in Table 6, line 3 and 4), and all the mapping relationships between them are “exact match”. The first condition in Equation 9 is used to calculate the final similarity between the concepts “arroyo (dry river)” in OC and “wash” in OA. The similarity value between these two concepts is calculated as 1.0; thus, the mapping relationship between these two concepts is “exact match”. This example demonstrates a common situation in the cross-lingual environment in that two concepts have the same semantic meaning while their names are definitely different. Moreover, the utility of applying our methodologies to the complex application of cross-lingual GI ontology integration has been proven.

Example 3: Concept pair of concept 3 “Water System” in OC and concept 3 “Surface water” in OA

At first glance, the semantic statements between the concept “water system” and “surface water” are not matched very well, and the concept names of these two concepts cannot be matched either.

This is because these two concepts are both the top concept in their own taxonomies, and these two concepts are abstract concepts in that they do not represent real-world objects with detailed characteristic entities, for example, rivers, lakes, and oceans. Thus, the definitions of this category in different languages may be very different, even when they are conveying the same meaning. Therefore, the solution for the semantic meaning representation of this type concept is not the same as the solution used in Examples (1) and (2). The sematic meaning of the hyponym-related concepts should be considered to infer the integrated semantic meaning of this abstract concept. After the implicit semantic statements have been inferred out (detailed mapping relationships are illustrated in Table 6, line 5 and 6), the first condition in Equation (9) is used to calculate the final similarity between the concepts “water system” in OC and “surface water” in OA. The similarity value between these two concepts is calculated as 0.92; thus, the mapping relationship between these two concepts is “close match”.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

The presented research focuses on the determination of semantic mapping relationships between categories in different GI ontologies with natural language barriers. The proposed formal ontology model in this study is used to represent and identify the semantic characteristics of the GI categories with OWL-based semantic statements transformed from free-text definitions of two GI classification standards. A new similarity calculation algorithm based on this formal ontology model is presented to distance the semantic similarities and identify the mapping relationships between categories.

In particular, we work with two classification standards of topographic maps in Chinese and American English. The conducted experiment indicates that the proposed approach successfully determines the mapping relationships between categories in different GI ontologies and facilitates ontology integration in a cross-lingual environment. Due to the usages of the multilingual supported NLP tools in our experiment, it is easy to replicate our model to determine the mapping relationships between other GI ontologies, which may be described using other native natural languages, in addition to Chinese. However, this model has only been applied to geospatial information (GI) integration at the category level, and research on GI integration at the data level has not been fulfilled. That will form the basis for future study. In addition, publishing the mapping information in a cross-lingual context as linked data in a semantic web environment should also be considered.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geoinformation, China, under the Special Fund for Surveying, Mapping and Geographical Information Scientific Research in the Public Interest (No. 201412014), and Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (No. 20120141110048).

Author Contributions

This research was mainly performed and prepared by Xi Kuai and Lin Li. Xi Kuai and Lin Li contributed with ideas, conceived and designed the study. Xi Kuai wrote the paper. Heng Luo, Hang Shen and Yu Liu contributed the tools, and analyze the results of the experiment. Zhijun Zhang reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix: Detail of the Mapping Statements between OC and OA

Table A1.

Detail of the Mapping Statements between OC and OA.

| Property Types | Semantic Statements in Oc in Chinese | Translation of Semantic Statements in Oc in English | Semantic Statements in OA in English | Mapping Relations | Semantic Statements in Oc in Chinese | Translation of Semantic Statements in Oc in English | Semantic Statements in OA in English | Mapping Relations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | 水 | water | water | Exact match | 石 | stone | stones | Exact match |

| 水蒸气 | water vapor | vapors | Exact match | 木桩 | wooden stake | wood | Close match | |

| 泥 | mud | mud | Exact match | 草地 | grassland | grassy | Close match | |

| 砖 | brick | brick | Exact match | 砾石 | gravel | gravel | Exact match | |

| 沙 | sand | sand | Exact match | 礁石 | reef | reef | Exact match | |

| 水泥 | cement | concrete | Exact match | |||||

| Nature | 自然的 | natural | natural | Exact match | ||||

| 人造的 | manmade | manmade | Exact match | |||||

| Status | 流动 | flow | flowing | Exact match | 倾泻 | pour | moving outward an downslope | Close match |

| 独立 | stand along | free standing | Exact match | 高潮时被水体淹没,低潮时露出 | submerged at high tide the water, exposed at low tide | alternately covered and left bare by the tide | Exact match | |

| 有水潮浸 | tide water immersion | washed by waves or tides | Close match | 涌出 | emission | issue from the ground | Close match | |

| 干涸 | dried up | dry | Exact match | 洪水泛滥 | flood | subject to flooding | Exact match | |

| Temporality | 长期 | long-term | permanent | Close match | 降水或融雪后短时间内 | within a short time after rainfall or snowmelt | during or after a local rainstorm or heavy snowmelt | Exact match |

| 终年 | all year round | permanent | Exact match | 季节性 | seasonal | occasionally | Close match | |

| Location | 沙地 | sandy | desert | Close match | ||||

| Purpose | 引水 | water diversion | run water | Exact match | 减缓水流流速 | slow water flow rate | restrain current or tide | Close match |

| 输水 | water delivery | conveying water | Exact match | 保护港口 | protection of harbor | protect harbor | Exact match | |

| 贮水 | water storage | contain water | Exact match | 护岸 | bank protection | sustain an embankment | Exact match | |

| 将水位升高或降低,使船能在不同高低水位的水道间通行 | To raise or lower the water level, at different high and low water level so the ship channel traffic | raise and lower vessels as they pass from one level to another. | Exact match | 抬高水位 | raising of water level | raise the level of water | Exact match | |

| 控制流量 | control flow | control the flow of water | Exact match | 通行船只 | passage vessel | route for watercraft | Exact match | |

| 灌溉 | irrigation | irrigation | Exact match | 拦截河流 | blocked rivers | Across the course of a stream | Close match | |

| 调节水流方向 | adjusting to the flow direction | direct current or tide | Exact match | 扬水 | pump up water- | Pump | Exact match | |

| Morphology | 陡坡 | steep slope | a vertical or near vertical descent | Close match | 坝式 | dam type | dam | Exact match |

| 虹吸式 | siphon | siphon | Exact match | |||||

| Cause | 堆积 | accumulation | accumulate | Exact match | ||||

| Relation Types | ||||||||

| Hierarchical Relation | 源头 | source | source | Exact match | 设施 | facilities | facility | Exact match |

| 河床 | riverbed | channel bottom | Exact match | 构筑物 | structure | construction | Exact match | |

| 区域 | regional | region | Exact match | 通道 | channel | path | Exact match | |

| 地带 | zone | zone | Exact match | 水道 | waterways | waterway | Exact match | |

| 设备 | device | device | Exact match | |||||

| Spatial Relation | 地面上 | on the ground | on the surface of the land | Close match | 水体平均大潮高潮面与水体最低低潮面之间 | mean high water springs of water and water between the lowest low water | Between high water and low water marks | Exact match |

| 水体内 | in body of water | in water | Exact match | 沿河流 | along the river | alongside a stream | Exact match | |

| 海域内 | within the sea | in the sea | Exact match | 水陆间 | between land and water | contact between a body of water and the land | Exact match | |

| 水下 | underwater | below the surface of water | Exact match | 洼地内 | in the depressions | surrounded by land | Close match | |

| 跨流域 | across river basins | across the course of a stream | Exact match | 陆地上 | on the land | Covered with the earth | Close match | |

| 跨道路 | cross roads | crossing road or trail | Exact match | 海岸线与干出线之间 | between the coastline and the dry line | Between high water and low water lines | Exact match | |

| 海岸边 | coastal | adjacent to the shore | Exact match | 海岸边 | the coast | offshore | Close match | |

| Is-part-of | 网状水系 | network drainage | network of interlacing channels | Exact match | 水库 | reservoir | dam | Close match |

| 网状水系 | network drainage | a drainage network | Exact match | 河渠 | canal | a river system | Close match | |

| 闸室 | chamber | lock chamber | Exact match | |||||

References

- Gore, A. The digital earth: Understanding our planet in the 21st century. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1999, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craglia, M.; Goodchild, M.F.; Annoni, A.; Camara, G.; Gould, M.; Kuhn, W.; Mark, D.; Masser, I.; Maguire, D.; Liang, S.; et al. Next-generation digital earth: A position paper from the vespucci initiative for the advancement of geographic information science. Int. J. Spat. Data Infrastruct. Res. 2008, 3, 146–167. [Google Scholar]

- Craglia, M.; de Bie, K.; Jackson, D.; Pesaresi, M.; Remetey-Fülöpp, G.; Wang, C.; Annoni, A.; Bian, L.; Campbell, F.; Ehlers, M.; et al. Digital Earth 2020: Towards the vision for the next decade. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2012, 5, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Di, L.; Yang, W.; Yu, G.; Zhao, P. Semantics-based automatic composition of geospatial Web service chains. Comput. Geosci. 2007, 33, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowicz, K.; Hitzler, P. The digital earth as knowledge engine. Semant. Web 2012, 3, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz, K. Observation-driven geo-ontology engineering. Trans. GIS 2012, 16, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccella, A.; Cechich, A.; Gendarmi, D.; Lanubile, F.; Semeraro, G.; Colagrossi, A. Building a global normalized ontology for integrating geographic data sources. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishr, Y. Overcoming the semantic and other barriers to GIS interoperability. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1998, 12, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, R.L. Semantic Interoperability of Distributed Geoservices. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fallahi, G.R.; Frank, A.U.; Mesgari, M.S.; Rajabifard, A. An ontological structure for semantic interoperability of GIS and environmental modeling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2008, 10, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, C.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Schetselaar, E.M.; van der Meer, F.D.; Liu, G.; Wange, X.; Zhang, X. Development of a controlled vocabulary for semantic interoperability of mineral exploration geodata for mining projects. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, W. Geospatial semantics: Why, of what, and how? J. Data Semant. III 2005, 3534, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.-H.; Kuo, C.-L. A semi-automatic lightweight ontology bridging for the semantic integration of cross-domain geospatial information. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.T.; Egenhofer, M.J.; Davis, C.A., Jr.; Borges, K.A.V. Ontologies and knowledge sharing in urban GIS. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2000, 24, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundt, H.; Bishr, Y. Domain ontologies for data sharing–An example from environmental monitoring using field GIS. Comput. Geosci. 2002, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Raskin, R.; Goodchild, M.; Gahegan, M. Geospatial Cyberinfrastructure: Past, present and future. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2010, 34, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoimenov, L.; Stanimirovic, A.; Djordjevic-Kajan, S. Discovering mappings between ontologies in semantic integration process. In Proceedings of the 9th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Visegrád, Hungary, 20–22 April 2006.

- Janowicz, K.; Raubal, M.; Kuhn, W. The semantics of similarity in geographic information retrieval. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2011, 2, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwering, A.; Raubal, M. Spatial relations for semantic similarity measurement. In Perspectives in Conceptual Modeling; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimpour, F. Using Ontologies to Resolve Semantic Heterogeneity for Integrating Spatial Database Schemata; Zurich University: Zurich, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, D.M.; Skupin, A.; Smith, B. Features, objects, and other things: Ontological distinctions in the geographic domain. In Spatial Information Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, C.; Jens, L.; Konrad, H.; Sören, A. Linkedgeodata: A core for a web of spatial open data. Semantic Web 2012, 3, 333–354. [Google Scholar]

- Trojahn, C.; Fu, B.; Zamazal, O.; Ritze, D. State-of-the-Art in Multilingual and Cross-Lingual Ontology Matching; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Hogan, W.R.; Crowley, R.S. Natural Language Processing methods and systems for biomedical ontology learning. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitelaar, P.; Cimiano, P.; Magnini, B. Ontology learning from text: Methods, evaluation and applications. Comput. Linguist. 2006, 32, 569–572. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S.; Klein, E.; Loper, E. Natural Language Processing with Python; O’Reilly Vlg. GmbH & Co.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jurafsky, D.; Martin, J.H. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras, M.; Kokla, M.; Tomai, E. Comparing categories among geographic ontologies. Comput. Geosci. 2005, 31, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, M.; Kokla, M. Theories of Geographic Concepts: Ontological Approaches to Semantic Integration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, T.; Donnelly, M.; Smith, B. A spatio-temporal ontology for geographic information integration. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 765–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.G.; Fu, L.Y.; Ma, X.G.; Fox, P. SEM+: Tool for discovering concept mapping in Earth science related domain. Earth Sci. Inform. 2015, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwering, A. Approaches to semantic similarity measurement for geo-spatial data: A survey. Trans. GIS 2008, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccella, A.; Cechich, A.; Fillottrani, P. Ontology-driven geographic information integration: A survey of current approaches. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatore, A.; Bertolotto, M.; Wilson, D.C. Geographic knowledge extraction and semantic similarity in OpenStreetMap. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2013, 37, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatore, A.; Wilson, D.C.; Bertolotto, M. Computing the semantic similarity of geographic terms using volunteered lexical definitions. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 27, 2099–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Raskin, R.; Goodchild, M.F. Semantic similarity measurement based on knowledge mining: An artificial neural net approach. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 26, 1415–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Z. Research on semantics of entity space similarity measure based on artificial neural networks. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Geoinformatics, Wuhan, China, 19–21 June 2015.

- Laurini, R. Geographic ontologies, gazetteers and multilingualism. Future Internet 2015, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Brennan, R.; O’Sullivan, D. A configurable translation-based cross-lingual ontology mapping system to adjust mapping outcomes. Web Semant. Sci. Serv. Agents World Wide Web 2012, 15, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sini, A.; Sini, M. Mapping AGROVOC and the Chinese Agricultural Thesaurus: Definitions, tools, procedures. New Rev. Hypermedia Multimed. 2006, 12, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Isaac, A.; Schopman, B.; Schlobach, S.; van der Meij, L. Matching multi-lingual subject vocabularies. In Research & Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Meilicke, C.; García-Castrod, R.; Freitas, F.; van Hage, W.R.; Montiel-Ponsoda, E.; de Azevedo, R.R.; Stuckenschmidt, H.; Šváb-Zamazal, O.; Svátek, V.; Tamilin, A.; et al. MultiFarm: A benchmark for multilingual ontology matching. J. Web Semant. 2012, 15, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, G.; Carpuat, M.; Fung, P. Identifying concepts across languages: A First step towards a corpus-based approach to automatic ontology alignment. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on Computational linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, August 2002.

- Pazienza, M.T.; Stellato, A. Linguistically motivated ontology mapping for the semantic web. In Proceedings of the 2nd Italian Semantic Web Workshop, Trento, Italy, 14–16 December 2005; pp. 14–16.

- Jung, J.J.; Håkansson, A.; Hartung, R. Indirect alignment between multilingual ontologies. In Agent and Multi-Agent Systems: Technologies and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 5559, pp. 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Trojahn, C.; Quaresma, P.; Vieira, R. A Framework for multilingual ontology mapping. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Marrakech, Morocco, 28–30 May 2008; pp. 1034–1037.

- Wang, S.; Englebienne, G.; Schlobach, S. Learning concept mappings from instance similarity. In The Semantic Web—ISWC 2008; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Shao, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, L. RiMOM2013 results for OAEI 2013. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Workshop on Ontology Matching, Sydney, Australia, 21 October 2013.

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, Q.; Shi, F.; Li, J.; Tang, J. RiMOM results for OAEI 2009. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Workshop on Ontology Matching, Washington, DC, USA, 25 October 2009.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, Y.; Tang, J. RiMOM results for OAEI 2010. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Ontology Matching, Shanghai, China, 7 November 2010.

- Euzenat, J.; Shvaiko, P. Ontology Matching; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrig, M.; Sure, Y. Ontology mapping–An integrated approach. In The Semantic Web: Research and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kalfoglou, Y.; Schorlemmer, M. Ontology mapping: The state of the art. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2003, 18, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, A.H.; Madhavan, J.; Domingos, P.; Halevy, A. Ontology matching: A machine learning approach. In International Handbooks on Information Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 397–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor, P. Foundations of statistical natural language processing. Nat. Lang. Eng. 1999, 26, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- MacCartney, B. The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group. Available online: http://nlp.stanford.edu/ (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Guarino, N. Formal ontology, conceptual analysis and knowledge representation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 1995, 43, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herre, H. General Formal Ontology (GFO): A foundational ontology for conceptual modelling. In Theory & Applications of Ontology Computer Applications; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 297–345. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.U. Ontology for spatio-temporal databases. In Spatio-Temporal Databases; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 9–77. [Google Scholar]

- Casati, R.; Smith, B.; Varzi, A.C. Ontological tools for geographic representation. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Grenon, P.; Smith, B. SNAP and SPAN: Towards dynamic spatial ontology. Spat. Cognit. Comput. 2004, 4, 69–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).