Abstract

With the development of the Internet of Things (IoT) and smart industry, the demand for high-precision indoor positioning is becoming increasingly urgent. Ultra-ideband (UWB) technology has become a research hotspot due to its centimeter-level ranging accuracy, good penetration, and high multipath resolution. However, in complex environments, it still faces problems such as high cost of anchor node layout, gross errors in observation data, and difficulty in eliminating systematic errors such as electronic time delay. To address the aforementioned problems, this paper proposes a comprehensive UWB indoor positioning scheme. By constructing virtual reference stations to enhance the observation network, the geometric structure is optimized and the dependence on physical anchors is reduced. Combined with a gross error elimination method under short-baseline constraints and a double-difference positioning model including virtual observations, it systematically suppresses systematic errors such as electronic delay. Additionally, a quality control strategy with velocity constraints is introduced to improve trajectory smoothness and reliability. Static experimental results show that the proposed double-difference model can effectively eliminate systematic errors. For example, the positioning deviation in the Xdirection is reduced from approximately 2.88 cm to 0.84 cm, while the positioning accuracy in the Ydirection slightly decreases. Overall, the positioning accuracy is improved. The gross error elimination method achieves an identification efficiency of over 85% and an accuracy of higher than 99%, providing high-quality observation data for subsequent calculations. Dynamic experimental results show that the positioning trajectory after geometric enhancement of virtual reference stations and velocity-constrained quality control is highly consistent with the reference trajectory, with significantly improved trajectory smoothness and reliability. In summary, this study constructs a complete technical chain from data preprocessing to result quality control, effectively improving the accuracy and robustness of UWB positioning in complex indoor environments, and exhibits promising engineering application potential.

1. Introduction

UWB technology uses nanosecond-level pulse signals for distance measurement, featuring extremely high time resolution and good penetration, thus being widely applied in the field of indoor positioning. Compared with conventional wireless positioning technologies, UWB positioning can provide centimeter-level or even higher-precision measurement results and exhibit stronger suppression capability against multipath interference. Existing studies have pointed out that due to its wideband characteristics, UWB signals can reduce errors to sub-centimeter level under line-of-sight (LOS) conditions [1,2]. In addition, UWB pulse signals can effectively penetrate obstacles such as walls and reduce reflection interference using multipath resolution characteristics, thus maintaining high positioning stability and accuracy in complex scenarios [2,3]. These advantages make UWB positioning not only significant in high-precision indoor positioning applications such as industrial manufacturing, warehousing and logistics, and robot navigation but also gradually expanded to diversified scenarios including smart home device linkage [4], positioning in low-speed autonomous driving scenarios [5], navigation in enclosed spaces such as underground parking lots [6], and asset tracking integrated with RFID [7].

However, in actual complex indoor environments, the accuracy of UWB positioning is often affected by various error sources. Among them, systematic errors are one of the key factors limiting accuracy. Typical systematic errors include electronic time delay inside transceivers, antenna phase center offset, clock drift, etc. Electronic time delay error originates from the delay difference between the chip and the antenna. Although this delay is relatively stable for each device, there are slight differences between devices, and each nanosecond of time delay error can lead to a ranging error of approximately 30 cm [8]. In addition, due to the misalignment between the antenna phase center and the geometric center, the equivalent distance error introduced by the antenna when the signal transmission/reception direction or frequency changes cannot be ignored [9]. Environmental factors can also exacerbate errors. For example, indoor temperature fluctuations will affect the propagation speed of UWB signals, leading to additional ranging deviations [10], while humidity changes may alter signal attenuation characteristics, indirectly affecting time-of-flight (TOF) estimation accuracy [10,11]. In complex indoor scenarios, multipath propagation and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions will introduce additional deviations and time-varying noise, and signal interference when multiple tags work simultaneously will further reduce positioning reliability [12]. As analyzed by Su, UWB ranging accuracy is jointly affected by internal factors (such as hardware interference and algorithm errors) and external factors (such as NLOS interference). Among them, internal errors can be corrected through algorithm improvements, but external NLOS errors are difficult to completely eliminate in practice [3,9]. At the same time, the performance limitations of low-cost UWB hardware will also amplify systematic errors, restricting its large-scale application in consumer scenarios [13]. Therefore, to achieve reliable high-precision UWB indoor positioning, it is necessary to conduct in-depth analysis and eliminate the impact of these systematic errors on ranging results.

To address the above issues, scholars at home and abroad have carried out various studies to eliminate or compensate for UWB systematic errors. In terms of error model construction, some studies have referred to GNSS error modeling experience to systematically classify UWB ranging. For example, Zhao proposed a UWB ranging model, expressing the observation value as the geometric distance plus terms such as electronic delays (e_r, e_s) of tags and base stations, and antenna phase center offsets (A_r, A_s) [9]. This model clearly distinguishes systematic errors from multipath and station coordinate errors, laying a foundation for subsequent error elimination. In terms of time delay estimation and calibration methods, researchers have proposed various calibration strategies. A common method is Two-Way Ranging (TWR) calibration, which estimates the time delay deviation between transceivers by calculating the round-trip time difference; there are also methods based on maneuver calibration, which use moving devices to collect data to fit the time delay model [8]. Some studies have also focused on the impact of UWB pulse shaping technology on time delay estimation, reducing inherent system errors by optimizing signal waveforms [14]. For filtering strategies, many works have introduced filtering technologies such as Kalman filtering into UWB positioning systems. For example, Su et al. (2025) designed an error compensation method combining maximum likelihood estimation and adaptive extended Kalman filtering for fast NLOS identification and ranging compensation in workshop scenarios [3]. Zhang et al. (2022) constructed an anchor LOS/NLOS information map and proposed an adaptive extended Kalman filtering algorithm to suppress abnormal deviations caused by random NLOS by adjusting the noise model in real time [15]. In addition, some scholars have used advanced methods such as improved particle filtering [16] and machine learning algorithms [17] to handle nonlinear errors and gross errors. For example, Meissner et al. (2010) regarded multipath reflections as a Ultra-Wideband Virtual Reference Station (UVRS) using known indoor floor plans and estimated positions using Bayesian filtering technology, realizing positioning with only a single physical anchor [18]. Cross-technology integration has also become an important idea for error compensation, such as the integrated positioning method of UWB and LiDAR, which reduces the error accumulation of a single technology through complementary advantages [19].

In recent years, the concept of Virtual Reference Station (VRS) has been introduced into UWB positioning research. Originating from the GNSS field, the basic idea of VRS is to generate localized differential correction signals for positions near users based on a continuously operating reference station network, making users seem to have a virtual station, thereby achieving centimeter-level accuracy [20,21]. In the UWB field, a similar idea is to construct UVRS or virtual observations through networked ranging to enhance the available information for positioning. Some works attempt to create UVRS by combining known environmental information: for example, Meissner used building floor plans and UWB multipath responses to calculate virtual anchor positions, realizing positioning by ranging these UVRS [18]. Some studies have further improved positioning accuracy by optimizing the distribution density and geometric configuration of UVRS [22]. Current research on UWB VRS is still in the exploration stage, mainly focusing on how to fuse multi-anchor data to generate high-quality virtual observations and how to synchronously eliminate systematic errors between anchors. For example, referring to GNSS VRS technology, it is necessary to uniformly calibrate time deviations and hardware deviations between multiple UWB base stations; at the same time, how to use virtual observations to cover wireless blind areas or improve anchor geometric conditions is also an urgent problem to be solved. In addition, the exploration of cross-technology VRS fusion schemes (such as GNSS + UWB + INS) provides a new direction for improving positioning robustness in complex environments [23]. Existing studies have shown that constructing a virtual anchor network can partially increase the number of observations and positioning accuracy, but it also brings challenges to the synchronization of systematic errors and the effectiveness of observations, which require further in-depth research.

Based on current research experience, UWB positioning studies mainly focus on three types of cutting-edge approaches to address the challenges of complex indoor environments. The first is an enhancement method based on sensor fusion: for example, tightly coupling multi-source data such as UWB, IMU, and ultrasonic through factor graph optimization to suppress IMU drift and improve robustness in NLOS environments [24]; or fusing UWB with visual information to achieve centimeter-level accuracy using particle filtering [25]. The second is the introduction of intelligent algorithms, such as efficiently identifying NLOS errors using low-dimensional features and machine learning (KNN, random forests, etc.) [26]. The third focuses on innovations in hardware and underlying technologies, such as proposing a continuous-time framework based on non-uniform B-splines and generating virtual anchors through multi-hypothesis to maintain system observability when anchors are sparse [27,28].

Different from the aforementioned methods, the “Virtual Reference Station” proposed in this paper follows a unique path. Compared with fusion schemes relying on additional physical sensors (such as IMU and cameras), this method aims to improve performance through observation network enhancement and model optimization within a single UWB system, reducing system complexity and cost. In contrast to data-driven intelligent algorithms, this method systematically eliminates hardware systematic errors based on a double-difference model, featuring stronger interpretability and determinism. Furthermore, compared with the “virtual anchor” approach designed to supplement observations, the “Virtual Reference Station” in this paper not only serves as a geometric supplement but, more importantly, acts as a high-precision differential benchmark. By constructing double-difference observations to fundamentally separate common errors, it becomes the core driver for achieving breakthroughs in positioning accuracy.

In summary, although existing studies have proposed various UWB systematic error modeling and correction methods and attempted to eliminate static deviations using differential or virtual observation methods, there are still deficiencies in the existing work. For example, many methods do not systematically consider the problem of cooperative error modeling between multiple anchors but are limited to single-link calibration; there is also a lack of a unified strategy for the construction and effectiveness verification of virtual observations. In addition, as pointed out by Zhao, although methods such as double difference can eliminate time-invariant errors, they often amplify measurement noise and are difficult to identify large-scale gross errors [9]. Therefore, additional baseline constraints or quality control measures are needed to ensure the reliability of positioning results. Moreover, the unreasonable design of UWB baseline length will also affect the error compensation effect, which has not received sufficient attention in existing research [9,29]. At the same time, existing methods are still lacking in multi-environment adaptability and low-cost hardware compatibility, and there is a lack of a standardized visualization evaluation system for positioning results [30]. Overall, challenges in observation construction under virtual reference stations, cooperative elimination of systematic errors, gross error detection, and quality control of positioning results have not been fully resolved.

In view of the above deficiencies, this paper proposes a new idea for ultra-wideband indoor positioning: introducing the VRS concept into the UWB system to realize a new method combining virtual observation construction and cooperative error modeling. Its main innovations are as follows:

(1) Aiming at the core problems of high dependence on anchor nodes and difficulty in eliminating systematic errors in UWB positioning, this study innovatively proposes a “virtual enhanced differential positioning” method. By constructing a UWB virtual reference station grid to optimize observation geometry and enhance model strength, a single-tag UWB double-difference model is established on this basis. This method systematically eliminates major systematic errors such as electronic delay from the functional model, improving positioning accuracy from centimeter-level to millimeter-level, and achieving a fundamental breakthrough in accuracy.

(2) To comprehensively improve the reliability of positioning results, this study constructs a “geometric-kinematic dual constraint” quality control mechanism that runs through data preprocessing and result post-processing. In the data preprocessing stage, using the known geometric relationship formed by virtual reference stations, a short-baseline constraint method is proposed to effectively detect and eliminate gross errors in original ranging. In the result post-processing stage, based on indoor kinematic laws, a velocity constraint method is proposed to screen and eliminate gross errors in dynamic trajectories. This mechanism comprehensively ensures the robustness of positioning results and trajectory smoothness from the data source to the final output.

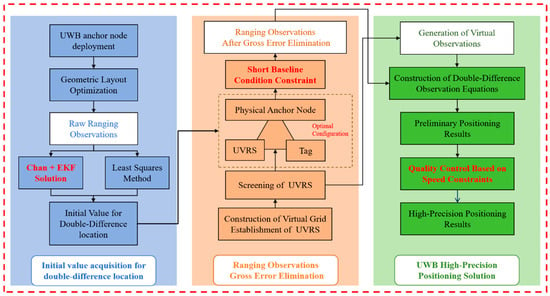

Figure 1 illustrates the overall processing flow and technical chain of the proposed high-precision UWB positioning solution. Aimed at systematically addressing core challenges in complex indoor environments-such as weak observation geometry, heavy gross error interference, and significant systematic errors-the method consists of three main stages:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the overall method framework in this paper.

(1) Data Preparation and Initial Solution Stage: On the basis of an optimized physical anchor node layout, raw ranging observations are acquired. Subsequently, a traditional fusion method combining the Chan algorithm and Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) is adopted to rapidly solve the initial value of the tag position, providing a reliable starting point for the subsequent double-difference positioning model that requires initial values.

(2) Virtual Enhancement and Double-Difference Positioning Solution Stage: This constitutes the core of the method. Firstly, a UWB Virtual Reference Station (UVRS) grid covering the positioning area is constructed to enhance spatial observation geometry. Utilizing the short-baseline conditions formed by virtual stations and physical anchor nodes, real-time detection and elimination of gross errors in ranging observations are implemented. Based on the purified observations and the selected optimal virtual reference stations, virtual observations are generated, and then a UWB double-difference observation equation capable of effectively eliminating systematic errors such as electronic delay is constructed and solved to obtain preliminary positioning results.

(3) Trajectory Post-Processing and Quality Control Stage: For the preliminary positioning results in dynamic scenarios, a posteriori quality control is performed by imposing constraints based on the continuity of motion velocity. Abnormal velocity points in the trajectory are identified and eliminated, ultimately outputting a smooth, reliable, and high-precision positioning trajectory.

This flowchart clearly reveals the complete closed-loop technical path of the proposed method—from observation geometry enhancement, data gross error purification, and systematic error elimination to result quality improvement—reflecting the systematicness and innovativeness of the scheme design.

2. Principle and Error Source Analysis of Ultra-Wideband Indoor Positioning Method

UWB indoor positioning methods can be mainly divided into two categories: Angle of Arrival (AoA)-based and distance measurement-based. AoA-based methods require array antennas, are extremely sensitive to angle measurement errors, and cannot be solved when anchor nodes and tags are collinear, so they are not suitable for high-precision UWB positioning. Distance measurement-based methods are more common, mainly including: estimating distance through signal attenuation models, which are susceptible to environmental interference and have low accuracy; calculating distance by measuring the one-way propagation time of signals, which requires strict clock synchronization between transmitters and receivers and has high implementation costs; positioning by measuring the time difference of signal arrival at different anchor nodes, which only requires clock synchronization between anchor nodes. However, the above methods have their own limitations. Among them, the Two-Way TimeofFlight (TW-ToF) method has become the preferred solution for high-precision ranging due to its no requirement for strict clock synchronization, and it is also the core ranging method adopted in this paper.

2.1. Two-Way TimeofFlight Ranging Method

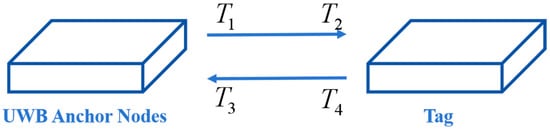

The TW-ToF ranging method specifically involves the anchor node transmitting a pulse response signal to the tag at a certain moment. The tag receives the signal, processes it, and feeds back a signal to the anchor node. The anchor node records the time of receiving the feedback signal, thereby calculating the flight time and further the distance between the anchor node and the tag. The process is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Working principle of TW-ToF.

The distance calculation method between the anchor node and the tag is:

Wherein, is the speed of light; is the time when the anchor node transmits the signal; is the time when the tag receives the signal; is the time when the tag transmits the signal; is the time when the anchor node receives the signal.

2.2. Analysis of Ranging Error Sources Based on TW-ToF

Based on the TW-ToF ranging principle, this paper classifies error sources into the following five categories:

(1) Electronic Component Delay

It refers to the transmission delay of signals between the internal circuit of the device and the antenna. It is mainly determined by hardware characteristics. Although theoretically constant, it actually manifests as a variable systematic error due to clock drift and antenna replacement.

(2) Antenna Phase Center Offset

The offset caused by the misalignment between the electrical center and the physical geometric center of the antenna. This offset value is closely related to the signal frequency and the spatial orientation of the antenna, directly affecting ranging accuracy.

(3) Multipath Error

Caused by multiple propagation paths generated by UWB signals after reflection and diffraction by objects such as walls and furniture. This error occurs randomly in complex indoor environments and is difficult to completely eliminate.

(4) NLOS Error

Generated when the propagation path of UWB signals is completely blocked by obstacles. In this case, the signal cannot propagate in a straight line, leading to a systematic overestimation of the ranging value and a constant positive error.

(5) Noise

Gaussian white noise caused by the device itself and environmental factors in UWB ranging, existing in various links such as tags and anchor nodes, with random characteristics.

(6) Statistical Modeling of Noise

To more accurately describe the ranging error distribution under multipath and NLOS conditions, this paper adopts the Weibull distribution for modeling UWB channel noise. Its probability density function is expressed as:

where denotes the scale parameter and represents the shape parameter. Experimental data fitting indicates that under NLOS conditions, the ranging error exhibits an obvious positive skewed distribution, and its statistical characteristics deviate significantly from the Gaussian distribution-resulting in degraded performance of traditional filtering methods based on the Gaussian assumption.

Traditional positioning algorithms usually combine all the above error terms as an overall noise for processing, or only perform rough control through random models (such as weight determination), failing to fundamentally separate and eliminate the systematic components (especially electronic delay differences and antenna offsets), resulting in insurmountable systematic deviations in positioning results. Therefore, constructing a positioning model that can effectively handle these error sources is the core challenge to achieve high-precision UWB positioning.

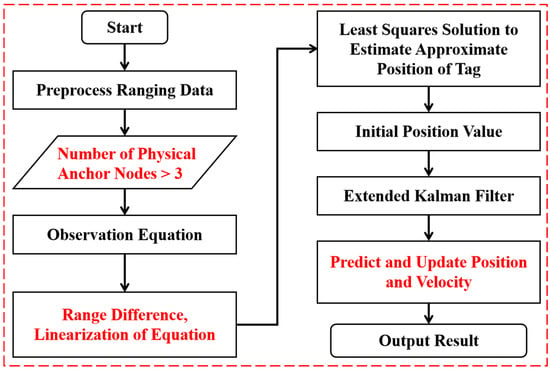

2.3. Basic Indoor Positioning Algorithm and Accuracy Evaluation

After obtaining ranging observations, to stably solve the subsequent double-difference positioning model, it is first necessary to obtain a high-precision initial value of the tag position. On the basis of traditional methods, this paper optimally adopts the least squares method based on Taylor series expansion or the integrated parameter estimation of the TDOA (Time Difference Of Arrival)-based Chan algorithm and Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) [31,32]. Among them, the least squares method has stable solution when given good initial approximate coordinates, but its convergence is severely dependent on the accuracy of the initial value. For this reason, this paper focuses on an improved method combining the Chan algorithm and EKF, which is described in detail below.

2.3.1. Fusion of TDOA-Based Chan Algorithm and EKF

This method uses the advantages of the Chan algorithm (no need to solve initial values and small computational complexity) to provide initial values for the EKF, and then uses the time-series filtering capability of the EKF to improve the smoothness and accuracy of the solution.

The Chan algorithm establishes a system of hyperbolic equations through TDOA observations and directly solves the tag position through two least squares estimations. Assuming the first anchor node as the reference, for the i-th anchor node, there is a TDOA observation value , where is the distance from the tag to the i-th anchor node. The core steps of the algorithm are as follows:

The first least squares assumes that the noise is independent Gaussian white noise. By introducing an intermediate variable, the nonlinear equation is converted into a linear equation for solution, obtaining the initial estimated value of the tag position. The second least squares uses the first estimation result and its constraint relationship with the intermediate variable to construct a linear equation again for weighted least squares estimation, thereby obtaining more accurate tag coordinates. The output of the Chan algorithm is used as the initial state vector of the EKF, and the state equation and observation equation of the system are established. Assuming the target moves at a constant speed, the state vector is taken as .

The output of the Chan algorithm is used as the initial state vector of the EKF , and the state equation and observation equation of the system are established.

Assuming the target moves at a constant speed, the state vector is taken as . The state equation is:

Wherein, is the state transition matrix, is the process noise, and its covariance matrix is .

The observation vector is the distance from the tag to each anchor node . The observation equation is:

Wherein, is the nonlinear distance function, is the observation noise, and its covariance matrix is . The recursive process of the EKF is as follows:

The state prediction equation is:

Perform observation update and calculate the Kalman gain :

Wherein, is the Jacobian matrix of the observation equation at. Then update the state estimation and covariance matrix:

and respectively, represent the predicted value of the state at time based on time and its covariance, and the Kalman gain balances the trust ratio between the predicted value and the new observation value. Through continuous iteration of the “prediction-update” steps, the EKF can effectively use historical observation information to smooth trajectory jumps caused by the independent solution of the Chan algorithm, make reasonable predictions when signals are temporarily lost, and finally output high-precision and smooth initial positioning values. The specific process is illustrated in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3.

Flowchart of Chan + EKF Algorithm for Positioning Solution.

2.3.2. Accuracy Evaluation

Accuracy evaluation is a key link to quantify the performance of positioning algorithms. This paper adopts two main evaluation indicators: Standard Deviation (STD) is used to measure the internal coincidence accuracy (stability) of positioning results, reflecting the dispersion degree of calculated values around their mean; Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is used to evaluate the external coincidence accuracy, reflecting the average deviation degree between calculated values and true values (or reference values). RMSE is the core indicator for evaluating positioning accuracy.

3. A High-Precision Positioning Theory and Method for UWB Virtual Reference Station

To address the three major challenges faced by UWB positioning in complex indoor environments—weak observation geometric structure, significant interference from ranging gross errors, and notable impact of systematic errors—this chapter proposes a systematic positioning method centered on UWB Virtual Reference Stations (UVRS). As illustrated in Figure 1, this method constructs a complete technical chain from data preprocessing, model solution to result post-processing, specifically encompassing the following four key links:

(1) Construction of UWB Virtual Reference Station Grid: By establishing a UVRS grid covering the experimental area, the diversity of spatial observation geometry is enhanced, and the dependence on the layout of physical anchor nodes is reduced.

(2) Gross Error Identification and Elimination Based on Short-Baseline Constraints: Utilizing the known geometric relationship formed by virtual stations and physical anchor nodes, real-time detection and elimination of gross errors in ranging observations are realized, improving data quality from the source.

(3) UWB Double-Difference Positioning Model Based on Virtual Observations: Virtual observations are introduced and a double-difference model is constructed, which effectively eliminates major systematic errors such as electronic delay through two difference operations.

(4) Dynamic Quality Control Based on Velocity Constraints: In dynamic positioning scenarios, the continuity constraint of motion velocity is used for posterior screening of trajectory results to eliminate abnormal points, ensuring the smoothness and reliability of the output trajectory.

Subsequent sections of this chapter will elaborate on the theoretical construction process and implementation details of each of the above links section by section.

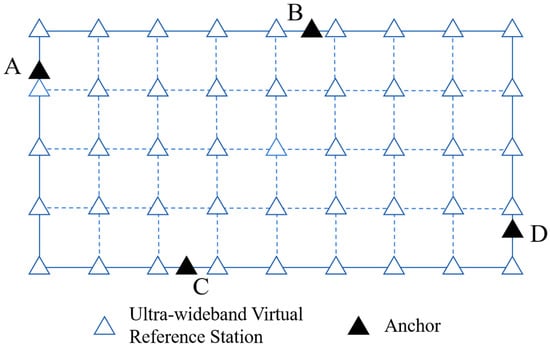

3.1. Construction of UWB Virtual Reference Station Grid

To overcome the limitations of physical anchor nodes in quantity, cost, and layout, this paper introduces the idea of Virtual Reference Station (VRS) in satellite navigation and positioning, and proposes a method to establish a UWB virtual reference station grid. The implementation process of this method is as follows: first, collect the coordinate information of all physical anchor nodes, and take their minimum bounding rectangle in the plane direction as the coverage area of the UVRS grid; then, based on the comprehensive consideration of the accuracy requirements of indoor positioning and computational efficiency, set the grid spacing to 2 m; then, generate a virtual reference station at each grid point, whose plane coordinates are accurately calculated by the starting grid point coordinates combined with row and column indexes and spacing, that is:

Wherein, are the row index and column index of the grid and is the grid spacing. Finally, to simulate the height difference of real anchor nodes and ensure the stability of positioning solution, the elevation of the virtual reference station is set as a random number following a normal distribution , where the mean is the average elevation of physical anchor nodes and the standard deviation is 0.5 m.

On the basis of grid construction, further establish the error model of virtual observations:

Wherein, is the virtual observation value, is the geometric distance from the virtual station to the tag, is the equivalent ephemeris error, which represents the known coordinate error here, is the equipment delay error, is the multipath effect error, and is the random observation noise.

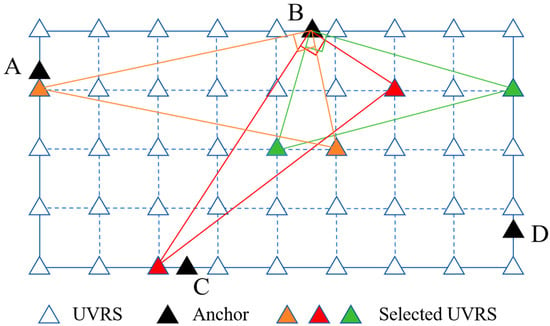

Through this process, a virtual reference station grid system covering the entire experimental area, with complete parameters and error characterization capabilities is finally constructed (the layout of virtual reference stations is shown in Figure 4). Thus, on the premise of not significantly increasing hardware costs, it effectively makes up for the possible layout defects and signal occlusion problems of physical anchor nodes, and provides rich observation geometry and redundant information for subsequent positioning solutions.

Figure 4.

Layout diagram of virtual reference stations. Physical anchor node labels A–D.

3.2. Construction of Gross Error Identification and Elimination Method Based on Short-Baseline Constraint of Virtual Reference Station

The establishment of the UVRS grid not only makes up for the single geometric configuration problem caused by the limited number of physical anchor nodes, but more importantly, provides a rich and controllable spatial constraint benchmark for gross error detection. By dynamically selecting multiple groups of UVRS from the grid to participate in the solution, it can effectively deal with the positioning weakening problem caused by physical anchor node occlusion or uneven distribution in different areas. This paper proposes a gross error detection and elimination method based on short-baseline constraints. Its core idea is to use the high-precision spatial geometric relationship formed by UVRS and physical anchor nodes to construct check conditions to identify abnormal ranging values.

3.2.1. Screening of Virtual Reference Stations Based on Forward Intersection Angle

In the UWB positioning system, the number and layout of physical anchor nodes are often limited, which easily leads to a single observation geometric configuration and insufficient strength. The establishment of the UVRS grid provides rich virtual observation resources to solve this problem. To avoid the computational redundancy and decline in geometric reliability caused by the undifferentiated use of all virtual reference stations, this paper proposes a dynamic UVRS screening mechanism based on forward intersection angle constraints.

As shown in Figure 5, assuming there are several physical anchor nodes in the virtual reference station grid, the system screens multiple virtual reference station combinations with optimal intersection geometry from the grid based on the current tag position and a physical anchor node (such as anchor node B in the figure). Specifically, the tag and physical anchor node are regarded as known points, and the virtual reference station is regarded as a point to be determined. In the spatial triangle formed by the three, the closer the intersection angle is to 90°, the stronger the geometric configuration. The screening target can be expressed as:

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of screening the optimal virtual reference station combination for physical anchor node B. Physical anchor node labels A–D.

Wherein, is the total number of virtual reference stations, and is the intersection angle corresponding to the i-th virtual reference station. In practical applications, the system can dynamically select several virtual reference stations (such as three) with optimal geometry for each physical anchor node to form multiple groups of strong geometric configurations to participate in subsequent processing. On the premise of not excessively increasing the computational load, this method makes full use of the resource advantages of the UVRS grid, effectively enhances the geometric diversity and robustness of the positioning system, and provides a reliable observation foundation for gross error detection and high-precision positioning.

3.2.2. Gross Error Identification Under Short-Baseline Constraint

After selecting the optimal virtual reference station, it forms a spatial triangle together with the physical anchor node and the tag. In this triangle, the baseline distance between the virtual reference station and the physical anchor node can be inversely calculated through their accurate known coordinates. This side length has high precision and can be used as a reliable constraint benchmark.

The other two sides of the triangle are the original ranging observation value from the tag to the physical anchor node and the calculated distance from the tag to the virtual reference station respectively, . Based on the basic triangle principle (the sum of any two sides is greater than the third side, and the difference between two sides is less than the third side), and considering UWB observation noise, the following gross error criteria are constructed:

Wherein, is the nominal ranging accuracy of the UWB device (such as 2 cm), and is an adjustable confidence factor (usually 3). If the above conditions are met, the observation value is considered to have no gross error, retained, and assigned a weight of 1 to participate in subsequent calculations; if not, the observation value is determined to be a gross error, assigned a weight of 0, and removed from the observation dataset of the current epoch.

This method makes full use of the spatial geometric advantages brought by the known coordinates of virtual reference stations, does not require a priori error models or a large amount of historical data, and can directly realize real-time and effective detection of gross errors at the observation level, laying a solid data foundation for subsequent high-precision positioning solutions.

3.3. UWB Double-Difference Positioning Model Based on Virtual Observations

To achieve high-precision differential positioning, it is first necessary to select an appropriate differential benchmark from the virtual reference station grid. This paper adopts the nearest neighbor principle and selects the virtual reference station closest to the approximate position of the tag at the current moment as the differential object. The rationality of this strategy lies in: when the virtual reference station is close to the tag, the spatial electromagnetic environment they are in is more similar, and the impact of common errors such as multipath effect and atmospheric delay is more consistent. This paper combines this strategy with an advanced double-difference positioning model (Zhao et al., 2021) [9], and innovatively applies it to the differential network composed of virtual reference station grids. By constructing double-difference observations, this model can effectively separate common systematic errors, thereby extracting high-precision geometric distance information in complex indoor electromagnetic environments, and significantly improving the reliability and accuracy of positioning solutions.

After determining the differential benchmark, it is necessary to generate virtual observations of the virtual reference station. This observation value is constructed through the following model:

Wherein, is the virtual observation value from the virtual reference station to anchor node b, is the actual ranging observation value from the tag to anchor node b, is the true geometric distance from the virtual reference station to anchor node b, is the true geometric distance from the tag to anchor node b, is the electronic delay difference between the tag and the virtual reference station, and is Gaussian white noise. This model corrects the spatial position difference by introducing a geometric distance correction term , compensates for hardware differences between devices using electronic delay differences , and simulates residual errors through Gaussian noise , thereby constructing high-precision virtual observations.

After obtaining virtual observations, a double-difference observation model is established to eliminate common errors. The double-difference processing is divided into two steps:

First, perform ‘inter-tag’ single difference:

This single-difference operation effectively eliminates the electronic delay error at the anchor node end. Then, a second difference is performed between the common-view anchor nodes to obtain the double-difference observation equation:

After double-difference processing, the electronic delay difference is completely eliminated, errors such as antenna phase center offset are also greatly reduced, and only small residual noise terms remain. To solve the tag coordinates, it is necessary to linearize the double-difference observation equation. Using Taylor series expansion and retaining the first-order term, the linearized equation is obtained:

Wherein, is the design matrix composed of direction cosines, and is the vector of coordinate corrections to be solved. Parameter estimation is performed using the least squares method:

Through iterative calculation, the initial coordinate value is continuously updated until convergence, and finally the high-precision three-dimensional coordinates of the tag are obtained. This double-difference positioning method effectively eliminates the impact of systematic errors and significantly improves positioning accuracy.

3.4. Dynamic Quality Control Based on Velocity Constraint

After obtaining the dynamic positioning results through the double-difference model solution, due to the amplification of observation noise and the influence of residual errors in the environment, there may still be a small number of gross errors in the positioning trajectory. To ensure the reliability of the final results, this paper proposes a post-quality control method for dynamic positioning results based on velocity constraints. The core idea of this method is to use the velocity continuity characteristic of indoor moving targets. In a typical indoor pedestrian movement scenario, the instantaneous velocity does not change drastically in a short time, and there is a reasonable upper limit. Based on this physical constraint, we can identify abnormal positioning results by analyzing the position change between adjacent epochs.

The specific implementation process of quality control is as follows: first, calculate the instantaneous velocity of the current epoch in the plane direction according to the sequence coordinates obtained by the double-difference positioning solution. The velocity calculation formula is:

Wherein, and respectively, represent the instantaneous velocities of the i-th epoch in the and directions, and are the plane coordinates of the i-th epoch, and is the time interval between adjacent epochs. After obtaining the instantaneous velocity, compare it with the preset velocity threshold. The discrimination condition is:

Wherein, is the velocity threshold set according to the movement characteristics of indoor pedestrians. Considering that the normal walking speed is usually within 1.5 m/s, this paper sets as the discrimination standard.

If the combined velocity of the current epoch exceeds this threshold, the positioning result of this epoch is considered to may have gross errors and should be eliminated; otherwise, the positioning result of this epoch is retained. Through this quality control method based on kinematic constraints, gross errors in the dynamic positioning trajectory can be effectively identified and eliminated, thereby improving the reliability of the final positioning results and the smoothness of the trajectory, and providing more reliable positioning data for applications such as indoor navigation and personnel tracking.

4. Experiment and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the high-precision positioning method based on the UWB Virtual Reference Station (UVRS) proposed in this paper, two sets of experiments (static and dynamic) are designed in this chapter. The experiments aim to evaluate the full-process performance from the introduction of virtual reference stations, to gross error detection, and then to double-difference solution and quality control, focusing on analyzing the role of UVRS in enhancing geometric configuration and improving positioning accuracy and reliability.

4.1. Introduction to Experimental Scenario

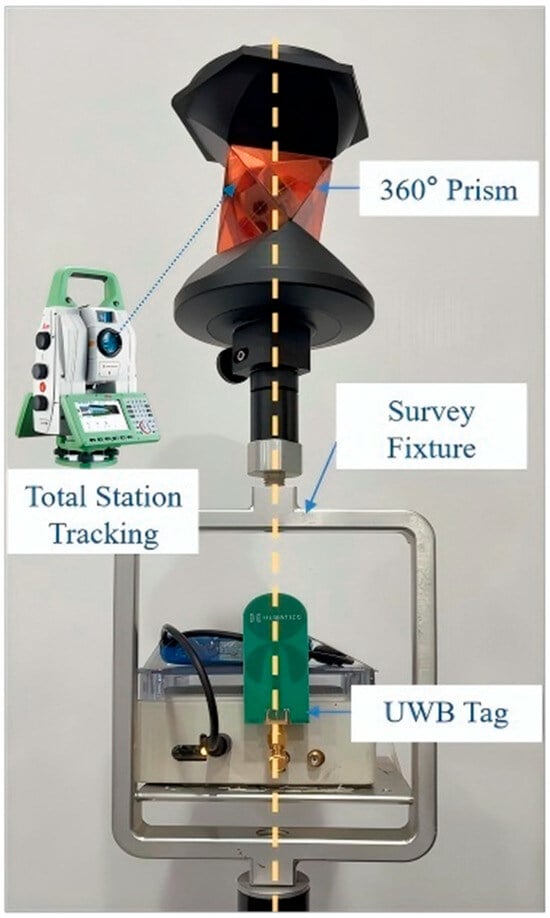

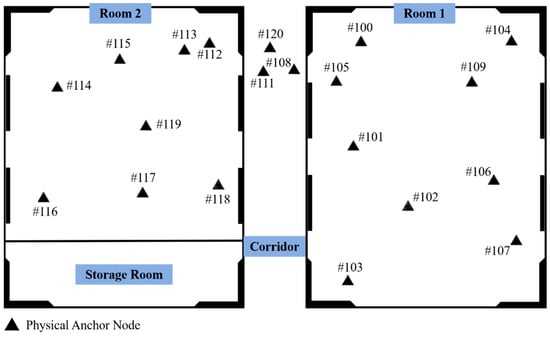

The experiment was conducted in two adjacent rooms with different structures and the connecting corridor of a teaching building. Room 1 features a complex layout with dense office facilities and numerous obstacles, while Room 2 is relatively spacious with few obstacles-forming a sharp contrast to test positioning performance under varying environmental complexities (the specific experimental scenario is shown in Figure 6). To construct a complete test scenario, physical anchor nodes were additionally deployed in the transition corridor area between the rooms. The experiment utilized ultra-wideband equipment (PulsON 410/440) for ranging and a high-precision total station (TS60) to automatically track the prism fixed to the UWB tag, obtaining millimeter-level reference coordinates and trajectories of the tag. Subsequently, the true distance between the anchor nodes and the tag was inversely calculated as the ranging reference benchmark (the core experimental equipment and parameters are shown in Figure 7 and Table 1). The layout of anchor nodes fully considered practical positioning application scenarios, with reasonable networking carried out in the two rooms according to real positioning requirements—slight differences in layout methods were adopted to eliminate interference from unnecessary factors on ranging results. All physical anchor nodes were integrated into a unified local coordinate system, with anchor node #100 as the coordinate origin, the true north direction as the X-axis, the true east direction as the Y-axis, and the zenith direction as the Z-axis (the specific planar layout is shown in Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Experimental Scenario Diagram (1 upper figure and 2 lower figures).

Figure 7.

Measuring Device Diagram.

Table 1.

Instrument and Equipment Parameter Table.

Figure 8.

Plane Layout Diagram of Physical Anchor Nodes. Physical anchor node labels #100 through #120 (used in testing).

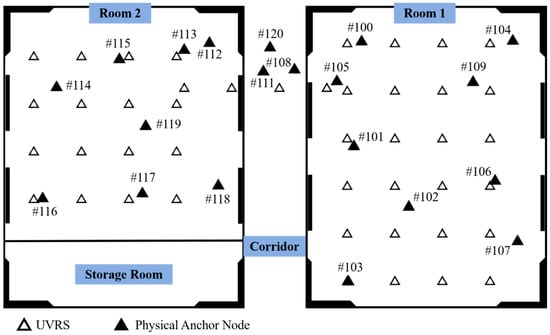

4.2. Generation of UWB Virtual Reference Stations

According to the method described in Section 2.1, a UWB Virtual Reference Station (UVRS) grid is constructed in the entire experimental area encompassing the two rooms and the connecting corridor. Considering the trade-off between positioning accuracy and computational complexity, the grid plane spacing is set to 2 m, and the elevation is configured to follow a normal distribution where the mean equals the average elevation of physical anchor nodes, so as to simulate real height variations and enhance the stability of positioning solutions. The overall layout of the virtual reference stations is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Plane Layout Diagram of Anchor Nodes After Virtual Reference Station Generation. Physical anchor node labels #100 through #120 (used in testing).

It can be seen from Figure 9 that the virtual reference station grid basically completely covers the experimental area, forming an auxiliary observation network without positioning blind areas, and providing a reliable geometric enhancement foundation for subsequent positioning solutions. It should be noted that when performing cross-room positioning solution, the system first dynamically selects the physical anchor nodes participating in the solution according to the approximate position of the tag at the current moment (located in Room 1, Room 2, or the corridor), and then constructs the corresponding virtual reference station based on the selected anchor nodes and generates virtual observations. Therefore, the composition and arrangement of virtual reference stations in different functional areas (such as the interior of the room and the transition area) are dynamic and targeted, and this partitioned layout feature is also reflected in Figure 9.

4.3. Performance Verification Experiment of Gross Error Detection Algorithm

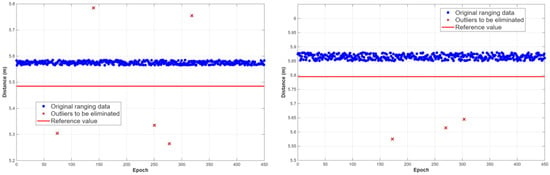

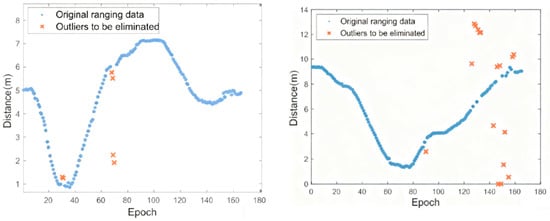

First, a quantitative evaluation of the gross error detection algorithm based on short-baseline constraints proposed in this paper is carried out. Some anchor node ranging data in static and dynamic experiments are selected for analysis, and the results are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. It can be seen that in addition to a normal systematic error with the reference value, the original ranging sequence also has obvious gross errors (gross errors). After processing by the short-baseline constraint algorithm proposed in this paper, these abnormal ranging values are effectively identified and eliminated, and smooth and normal ranging data are retained, which initially proves the effectiveness of the algorithm.

Figure 10.

Ranging Gross Error Elimination Results of Two Anchor Nodes in Static Experiment.

Figure 11.

Ranging Gross Error Elimination Results of Two Anchor Nodes in Dynamic Experiment.

To quantitatively evaluate the algorithm performance, two indicators of identification accuracy (Precision, P) and identification efficiency (Recall, R) are introduced. The data processing results of all experimental anchor nodes are counted, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitative Statistics Table of Gross Error Detection Algorithm Performance.

Statistical analysis indicates that the identification accuracy of the dynamic experiment is 100% for all anchor nodes except Anchor Node 4, demonstrating the high identification accuracy of the algorithm proposed in this chapter with almost no “false elimination” phenomenon. Meanwhile, the identification efficiency of the algorithm is all above 85%, and cases of “misdetection” and “missed detection” are extremely rare. Therefore, the ultra-wideband ranging gross error detection method based on short-baseline constraints can effectively detect outliers in ultra-wideband ranging data, obtain ranging values free of gross errors, significantly improve the quality of ranging data, and provide a reliable foundation for subsequent positioning solutions.

4.4. Analysis of Static Positioning Experiment

In the static experiment, a point in the central area of the room is selected for detailed analysis, and the positioning effects of the following three processing modes are compared and analyzed:

Mode A (Existing Algorithm): Only physical anchor nodes and original ranging values are used, and the solution is obtained through Chan + EKF.

Mode B (UVRS + Gross Error Elimination): After introducing the virtual reference station grid and completing gross error elimination, the solution is obtained through Chan + EKF.

Mode C (Proposed Method (Static)): On the basis of Mode B, the double-difference positioning model proposed in this paper is used for solution.

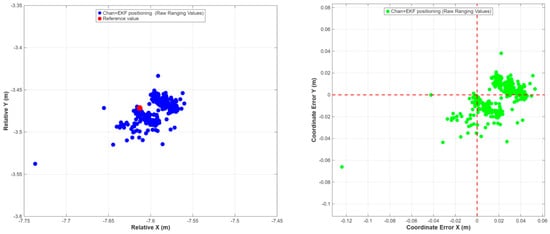

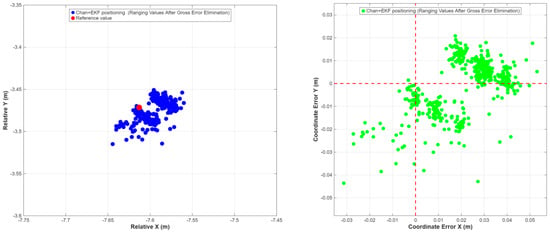

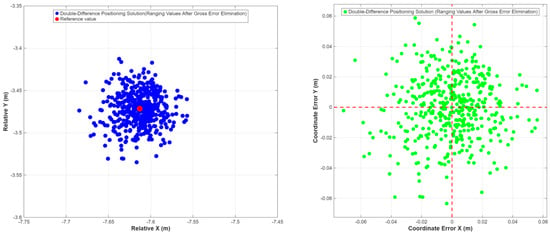

The positioning results and error comparisons of different modes are shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 and Table 3 and Table 4.

Figure 12.

Chan + EKF Positioning Results and Positioning Error Diagram in Static Experiment (Original Ranging Values). Red dash line denote the reference point location.

Figure 13.

Chan+EKF Positioning Results and Positioning Error Diagram in Static Experiment (Ranging Values After Gross Error Elimination). Red dash line denote the reference point location.

Figure 14.

Double−Difference Positioning Solution Results and Positioning Error Diagram in Static Experiment (Ranging Values After Gross Error Elimination). Red dash line denote the reference point location.

Table 3.

STD and RMSE of Double-Difference Positioning Results in Static Experiment (Unit: cm).

Table 4.

Comparison Between Positioning Mean and True Value of Different Processing Methods.

Analysis of the above charts and tables shows that compared with the existing algorithm, the introduction of UVRS and gross error elimination (Mode B) mainly improves the internal coincidence accuracy (STD is reduced by about 10%), but due to the failure to eliminate systematic errors, the systematic deviation between the positioning mean and the true value still exists. After adopting the double-difference model (Mode C, proposed method (static)), although the noise is amplified during the difference process, resulting in a slight increase in STD, the RMSE representing absolute accuracy is improved by more than 30% in the Xdirection, and the deviation between the positioning mean and the true value is reduced from 2.88 cm to 0.84 cm. This fully proves that the double-difference model can effectively identify and eliminate systematic errors in ranging values, and is the key to achieving high-precision static positioning.

4.5. Analysis of Dynamic Positioning Experiment

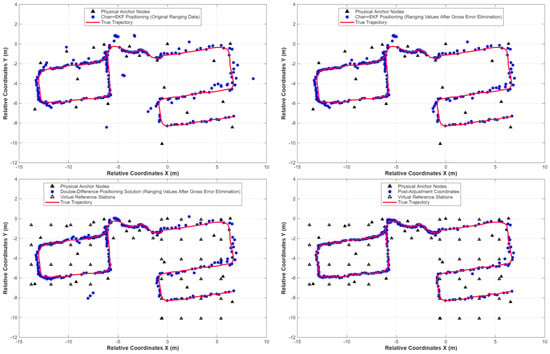

To verify the improvement effect of the proposed ranging data processing algorithm, differential positioning solution method, and quality control based on velocity constraint on dynamic positioning, a cross-room dynamic positioning experiment is carried out in this section, and four progressive experimental schemes are designed:

Scheme 1: Physical anchor nodes only + original ranging values (served as the comparison benchmark).

Scheme 2: Physical anchor nodes + ranging values after gross error elimination.

Scheme 3: On the basis of Scheme 2, introduce virtual reference stations for double-difference solution.

Scheme 4 (Complete Proposed Method (Dynamic)): On the basis of Scheme 3, implement quality control with velocity constraint.

The measurement tool was held by hand and moved at a normal indoor speed along the specified path. Throughout the entire process, the total station performed tracking to indirectly obtain the reference coordinates of the tag. The total length of the dynamic experimental path is approximately 25 m, covering a typical indoor movement trajectory from Room 1 through the corridor to Room 2. During the experiment, the hand-held measurement tool moved at a constant normal walking speed (approximately 0.8–1.2 m/s), with a data collection duration of about 30 s and a sampling frequency of 5 Hz. The reference trajectory was acquired in real time by a high-precision total station (TS60) and used as the true value for accuracy evaluation. The comparison of dynamic positioning trajectories among the four schemes is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Dynamic Experiment Positioning Trajectory Results (Top left: Scheme 1: Original ranging values; Top right: Scheme 2: Ranging values after gross error elimination; Bottom left: Scheme 3: Double-difference positioning after gross error elimination; Bottom right: Scheme 4: Gross error elimination + double-difference positioning + quality control).

According to the analysis of Figure 15:

Scheme 1 (Benchmark): The positioning trajectory has obvious systematic deviation and multiple gross errors, reflecting that the original observations are affected by both gross errors and systematic errors in complex environments, and the positioning results are unreliable.

Scheme 2 (Gross Error Elimination): After gross error detection and elimination, the significant jump points in the trajectory are greatly reduced, and the trajectory smoothness is improved, indicating that data preprocessing effectively improves the quality of observations. However, the systematic deviation still exists, indicating that only eliminating gross errors cannot overcome inherent systematic errors such as hardware delay.

Scheme 3 (Introducing Virtual Stations and Double-Difference Solution): On the basis of clean data, introducing virtual reference stations and performing double-difference processing significantly corrects the systematic deviation of the trajectory, and the overall shape is basically consistent with the reference trajectory, verifying the effectiveness of the double-difference model in eliminating systematic errors in dynamic scenarios. However, due to the amplification of residual random errors during the difference process, there are still a few obvious “jump points” in the solution results.

Scheme 4 (Complete Method (Dynamic)): Implementing velocity-constrained quality control on the basis of double-difference positioning successfully identifies and eliminates residual gross errors in the trajectory. The finally output dynamic trajectory is smoother and more continuous, and highly consistent with the reference trajectory, proving the comprehensive advantages of the full-process method proposed in this paper in improving the reliability and robustness of dynamic positioning.

To further quantify the positioning accuracy of each scheme, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between each trajectory and a specific measurement stop point of the reference trajectory was calculated, and the results are presented in Table 5:

Table 5.

RMSE between Trajectories of Each Scheme and a Specific Measurement Stop Point of the Reference Trajectory in Dynamic Experiment (Unit: cm).

As can be seen from the table, with the gradual introduction of each link, the positioning accuracy is significantly improved. The complete proposed method (Scheme 4) achieves the lowest RMSE, indicating that its trajectory is most consistent with the reference trajectory.

The experimental results show that from “gross error elimination” to “double-difference solution with virtual station enhancement”, and then to “motion-constrained quality control”, each link is progressive and complementary, jointly forming a complete technical chain to ensure the accuracy and reliability of UWB dynamic positioning.

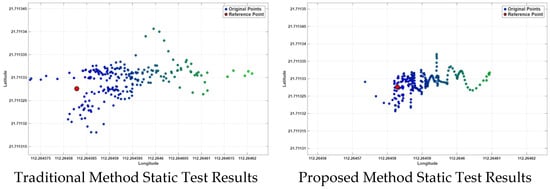

4.6. Verification Experiment in Complex Occlusion Scenarios

To fully verify the effectiveness and robustness of the method proposed in this paper in extremely complex industrial environments, supplementary experiments were conducted in the steam turbine plant of a nuclear power station. This scenario presents the following typical challenges: a complex internal structure filled with large-scale metal equipment, thick concrete walls, and dense pipelines, resulting in a harsh electromagnetic environment; severe non-line-of-sight (NLOS) occlusion and strong multipath reflection in signal propagation paths; limited activity space and irregular layout. This environment imposes extremely high requirements on the anti-interference capability and reliability of the UWB positioning system.

The experimental equipment and methods were consistent with those of the main experiments in this paper. Physical anchor nodes were deployed in key areas of the plant (such as equipment-dense areas, main passages, and corners), and a UWB Virtual Reference Station (UVRS) grid covering the area was constructed in accordance with the method described in Section 3.1 of this paper. A static point was selected for long-term observation, and a dynamic path crossing different obstacle areas was planned for mobile testing. The reference true values were obtained by tracking measurement with a high-precision total station (TS60).

As shown in Figure 16, at a static point near the equipment area, after applying the complete method proposed in this paper, the planar Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the positioning results is 3.8 cm, and the average deviation from the true value is less than 1 cm. Compared with the traditional method using only raw ranging values and Chan + EKF (with an RMSE of approximately 12.5 cm), the accuracy is improved by about 70%, which proves that the double-difference model can still effectively separate errors such as hardware delay in environments where strong multipath and systematic errors coexist.

Figure 16.

Static Test Results in Complex Environments. The blue-to-green color gradient of the points indicates the distance from the reference value, with greener hues representing farther points.

In the dynamic trajectory crossing the core area of the plant, after applying the full-process method proposed in this paper and velocity-constrained quality control, the overall RMSE between the trajectory and the reference true value is 5.1 cm. The trajectory is smooth without unreasonable points passing through fixed equipment or walls. When facing sudden NLOS occlusion (such as bypassing large metal tanks), the positioning results fluctuate briefly but can quickly recover through quality control and virtual station enhancement, demonstrating good robustness and environmental adaptability.

Supplementary experiments in the complex scenario of the nuclear power station indicate that the full-chain method of “geometric enhancement-gross error elimination-double-difference solution-quality control” based on UWB virtual reference stations proposed in this paper is not only applicable to conventional indoor environments but also effective in extreme industrial environments with severe signal occlusion, strong multipath, and complex electromagnetic interference. This method can significantly suppress the impact of systematic errors and gross errors, output stable, reliable positioning results with accuracy significantly superior to traditional methods, and verify the practicality and wide application potential of its technical scheme.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study addresses the core challenges of ltra-ideband (UWB) indoor positioning in complex environments—high dependence on physical anchor nodes, severe gross error interference in ranging observations, and difficulty eliminating systematic errors like electronic delay—by proposing a systematic high-precision positioning solution centered on UWB Virtual Reference Stations (UVRS).

This innovation is reflected in four progressive and complementary links that form a complete technical chain: For the first time, this study innovatively introduces the Virtual Reference Station (VRS) concept from satellite navigation into UWB indoor positioning. By generating a virtual station grid covering the entire area, this approach fundamentally optimizes the spatial observation geometric configuration and reduces reliance on high-cost, inflexibly deployable physical anchor nodes. Meanwhile, this paper proposes a method for real-time gross error identification and elimination based on the short-baseline spatial constraints of virtual stations. This method requires no a priori error models and achieves efficient detection directly using known geometric relationships; experiments show its identification accuracy exceeds 99% and efficiency surpasses 85%, ensuring observation data quality from the source. Furthermore, this study innovatively constructs a UWB double-difference positioning model suitable for single-tag scenarios. By introducing virtual observations and performing two difference operations, this model directly separates major time-invariant systematic errors (e.g., electronic delay differences between tags and anchor nodes) from the functional model, realizing a paradigm shift in error handling from “random model compensation” to “functional model elimination.” For dynamic positioning, this paper proposes a posteriori quality control mechanism based on the continuity of indoor pedestrian movement velocity. This mechanism effectively screens and eliminates abnormal trajectory points caused by residual noise or accidental errors, significantly enhancing the smoothness and reliability of the final output trajectory. To verify this method’s applicability in extreme industrial environments, supplementary tests were conducted in a complex workshop of a nuclear power station—an environment filled with strong multipath and severe Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) occlusion. After applying this complete method, static and dynamic positioning accuracies reached 3.8 cm and 5.1 showing significant improvements over traditional methods with smooth and reliable trajectories. This proves that this scheme can work effectively in complex environments, boasting excellent robustness and engineering practical value.

Through comparisons with representative advanced methods in recent years, this method demonstrates significant comprehensive performance improvements: In terms of positioning accuracy, static experimental results indicate that this double-difference model reduces the systematic deviation of positioning results from centimeter-level (approximately 2.88 cm) to millimeter-level (approximately 0.84 cm). The complete dynamic experimental scheme (Scheme 4) achieves a trajectory Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 3.1 cm, representing a roughly 75% accuracy improvement over the benchmark scheme using only physical anchor nodes. In terms of result reliability, this proposed gross error detection method outperforms most methods relying on statistical tests or machine learning in identification accuracy (>99%). Combined with velocity-constrained quality control, the maximum velocity fluctuation of the final dynamic trajectory is limited to within 0.7 m/s, and its smoothness is significantly superior to comparative methods—proving this method’s ability to output stable and reliable results in complex indoor environments. In terms of method systematicness, unlike most studies focusing on a single error source, this paper provides an end-to-end solution spanning data preprocessing, core solution, and result post-processing. While improving accuracy, this solution comprehensively enhances the robustness and practicality of the positioning system.

In summary, this research not only theoretically proposes and verifies a new framework for UWB virtual reference station differential positioning but also proves its comprehensive advantages in accuracy, reliability, and systematicness through complete experimental analysis—providing a new effective technical approach for high-demand indoor positioning applications.

Looking forward, this research can be further explored in two directions: On the one hand, this study can theoretically analyze and experimentally verify the quantitative relationship between the density and layout of the virtual reference station grid and final positioning accuracy to achieve adaptive optimal configuration. On the other hand, this method can be extended to more complex three-dimensional scenarios (e.g., multi-story buildings and large underground spaces) to test its performance under extreme conditions such as three-dimensional positioning and severe signal occlusion, thereby promoting its wider engineering application.

Author Contributions

Yinzhi Zhao performed validation, visualization, investigation, data curation, and wrote the original draft preparation. Jingui Zou was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review editing. Bing Xie conducted formal analysis, investigation, and data curation. Jingwen Wu contributed to conceptualization and provided supervision. Zhennan Zhou carried out formal analysis and writing—review editing, while Gege Huang participated in writing—review editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by “National Natural Science Foundation of China” (Grant No. 42504046) and “Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China” (Grant No. 2024AFB166).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first and corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support of the Research Center for High Accuracy Location Awareness of School of Geodesy and Geomatics at Wuhan University for their contribution on the materials used for experiments. We also thank the students who participated in the project.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jingwen Wu was employed by the company Jiangxi Copper Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd., Author Zhennan Zhou was employed by the companyChina Energy Engineering Group Anhui Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alarifi, A.; Al-Salman, A.; Alsaleh, M.; Alnafessah, A.; Al-Hadhrami, S.; Al-Ammar, M.A.; Al-Khalifa, H.S. Ultra Wideband Indoor Positioning Technologies: Analysis and Recent Advances. Sensors 2016, 16, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Bi, J.; Jia, H.; Seow, C. Ultra-Wideband Ranging Error Mitigation with Novel Channel Impulse Response Feature Parameters and Two-Step Non-Line-of-Sight Identification. Sensors 2024, 24, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xia, X.; Li, W.; He, L.; Yang, T. NLOS Identification and Error Compensation Method for UWB in Workshop Scene. Sensors 2025, 25, 6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, B.; Yang, L. Phase center offset calibration and multipoint time latency determination for UWB location. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 17536–17550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Zhao, L.B.; Su, C.; Lu, J.L.; Jin, T.; Zhou, Z.Q. Design and Implementation of Area Positioning System Based on UWB. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Harbin, China, 12–15 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Guo, L.X.; Liu, Z.Y.; Gao, S.S. Multipath-assisted ultra-wideband vehicle localization in underground parking environment using ray-tracing. Sensors 2025, 25, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccari, L.; Coruzzolo, A.M.; Lolli, F.; Sellitto, M.A. Indoor positioning systems in logistics: A review. Logistics 2024, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.A.; Cossette, C.C.; Forbes, J.R.; Le Ny, J. Calibration and uncertainty characterization for ultra-wideband two-way-ranging measurements. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.05888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zou, J.; Guo, J.; Huang, G.; Cai, L. A Novel Ultra-Wideband Double Difference Indoor Positioning Method with Additional Baseline Constraint. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.Z.; Mei, Z.Q.; Xu, X.Y.; He, Q.E. Ultra-wideband high accuracy distance measurement based on hybrid compensation of temperature and distance error. Measurement 2023, 206, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.S.; Wang, L.D.; Luo, Y.J.; Cheng, Y.X.; Kou, Z.H.; Xie, Z.W. Iterative maximum-likelihood estimation algorithm for clock offset and skew correction in UWB systems assisted by 5G NR multipath. Measurement 2025, 242, 115823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheem, K.; Kim, M.S. A low-cost foot-placed UWB and IMU fusion-based indoor pedestrian tracking system for IoT applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Yim, J.H. Performance improvement of UWB-sensor positioning using multiple filters. J. Sens. Sci. Technol. 2025, 34, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.N.; Sun, J.C.; Dai, L.Y.; Cai, P.; Kwak, K.S.; Yoo, S.J. A solution to the non-ideal delay line problem in transmitted reference pulse cluster schemes for UWB communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yan, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B. Research on UWB Indoor Positioning Algorithm under the Influence of Human Occlusion and Spatial NLOS. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhao, Z.J.; Shi, Y.Y.; Lu, Y. Implicit unscented particle filter based indoor fusion positioning algorithms for sensor networks. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 94, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.B.; Van Herbruggen, B.; Bröring, A.; Shahid, A.; De Poorter, E. Error mitigation for TDoA UWB indoor localization using unsupervised machine learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, P.; Gigl, T.; Witrisal, K. UWB sequential Monte Carlo positioning using virtual anchors. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, Zürich, Switzerland, 15–17 September 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:2591451 (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Kong, D.; Ni, P.Z.; Hu, W.M.; Song, X. An enhanced-LiDAR-UWB-INS integrated positioning methodology for unmanned ground vehicle in sparse environments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 9404–9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietra, V.; Dabove, P.; Piras, M. Loosely Coupled GNSS and UWB with INS Integration for Indoor/Outdoor Pedestrian Navigation. Sensors 2020, 20, 6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBG Systems. Virtual Reference Station (VRS). SBG Systems Website. Available online: https://www.sbg-systems.com/glossary/virtual-reference-station-vrs/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Luo, H.L.; Zou, D.P.; Li, J.S.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. Visual-inertial navigation assisted by a single UWB anchor with an unknown position. Satell. Navig. 2025, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, P.P.; Xu, T.H.; Nie, W.F.; Cong, Y.Z.; Xing, J.P.; Gao, F. Maximum mixture correntropy criterion-based variational Bayesian adaptive Kalman filter for INS/UWB/GNSS-RTK integrated positioning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Duan, S.; Yang, S.H. Indoor fusion positioning based on "IMU-ultrasonic-UWB" and factor graph optimization method. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12726. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.G.; Zhao, M.; Tang, F.X.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, J.Q.; Kato, N. UVtrack: Multi-modal indoor seamless localization using ultra-wideband communication and vision sensors. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Sun, P. UWB abnormal signal recognition based on machine learning classifier. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2023, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Sun, W.J.; Zhang, G.W.; Yang, K.; Li, S.; Meng, X.; Deng, N.; Tan, C. CT-UIO: Continuous-Time UWB-Inertial-Odometer Localization Using Non-Uniform B-spline with Fewer Anchors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.06287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, M.; Hesch, J. Continuous-time ultra-wideband-inertial fusion. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 3665–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.B.; Ye, S.B.; Lin, B.; Song, C.Y.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, G. Spatiotemporal parallel remote sensing of multiple adjacent concealed human targets. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2025, 73, 4322–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Garrido, J.; Vázquez, F.; Ruz, M.L. UCO DWM1001: A tool for managing and processing the UWB DWM1001-DEV development board. SoftwareX 2024, 26, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. J. Basic Eng. Trans. ASME Ser. D 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, D.; Liu, F.; Wen, Z. UWB positioning algorithm and accuracy evaluation for different indoor scenes. Int. J. Image Data Fusion 2021, 12, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.