Abstract

To address the challenge of obtaining high-spatiotemporal-resolution and high-precision temperature grids for agricultural meteorological monitoring, this research focuses on rice heat stress monitoring with the China Meteorological Administration Land Data Assimilation System (CLDAS) and develops a temperature correction model that synergizes physical mechanisms with a data-driven strategy by introducing a GeoAI framework. Ensemble learning methods (XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest) were utilized to process a comprehensive set of predictors, integrating dynamic surface features derived from FY-4 satellite’s high-frequency observation data. The data comprised surface thermal regime metrics, specifically the daily maximum land surface temperature (LSTmax) and its diurnal range (LSTmax_min), along with vegetation indices including the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and enhanced vegetation index (EVI). Further, topographic attributes derived from a digital elevation model (DEM) were incorporated, such as slope, aspect, the terrain ruggedness index (TRI), and the topographic position index (TPI). The approach uniquely capitalized on the temporal resolution of geostationary data to capture the diurnal land surface dynamics crucial for bias correction. The proposed models not only enhanced temperature data quality but also achieved impressive accuracy. Across China, the root mean square error (RMSE) was reduced to 1.04 °C, mean absolute error (MAE) to 0.53 °C, and accuracy (ACC) to 0.97. Additionally, the most notable improvement was that the RMSE decreased by nearly 50% (from 2.17 °C to 1.11 °C), MAE dropped from 1.48 °C to 0.80 °C, and ACC increased from 0.72 to 0.96 in the southwestern region of China. The corrected rice heat stress data (2020–2023) indicated that significant negative correlations exist between yield loss and various heat stress metrics in the severely affected middle and lower Yangtze River region. The research confirms that embedding geostationary meteorological satellites within a GeoAI framework can effectively enhance the precision of agricultural weather monitoring and related impact assessments.

1. Introduction

High-precision, high-spatiotemporal-resolution near-surface air temperature data are essential for global change research, environmental monitoring, and disaster early warning [1,2,3,4]. Land Data Assimilation Systems (LDASs), which merge real-time observations with model simulations to generate spatially continuous gridded data, have become a primary source for such information [5].

The critical requirement for reliable temperature data is exemplified in agricultural monitoring, particularly under global warming. Due to increasing climate instability, the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events have risen significantly, which has emerged as a major threat to crop production and food security [6,7,8,9,10]. In China, heatwaves concentrated from May to September [11,12,13] overlap with the heading and flowering stages of rice, a crop highly sensitive to temperatures above 35 °C [14,15,16,17]. Even brief exposure to 33.7 °C during flowering can impair pollen viability [18]. Therefore, accurate temperature data is the fundamental to effective heat stress monitoring and mitigation.

The China Meteorological Administration Land Data Assimilation System (CLDAS) provides gridded temperature covering Asia at hourly temporal and 0.0625° spatial resolutions, offering key support for regional agricultural meteorological disaster monitoring [19,20]. CLDAS is recognized for its higher spatiotemporal resolution and has demonstrated competitive performance against other systems such as the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) [21] and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis 5 (ERA5) [22,23,24]. However, CLDAS temperature still exhibits significant systematic biases and random errors, owing to sparse observational stations, complex assimilation algorithms, and land surface heterogeneity [25]. Substantial errors have been documented across various regions. Significant errors were observed in CLDAS daily maximum temperatures for Chongqing with an MAE of 1.14 °C [26]. In Qinling and Daba Mountains of Shaanxi Province, fewer than 30% of the temperature data had an absolute error within 2 °C [27]. Research in Lanzhou and Wuwei demonstrated that errors in daily and hourly temperatures varied systematically with altitude [28]. These errors directly affect the accuracy of rice heat stress monitoring in these regions.

A range of methods have been developed to correct temperature data and improve its quality. While traditional statistical methods, such as linear regression and quantile mapping, are simple and efficient, recent studies have introduced more specialized corrections. Li et al. [26] proposed a quasi-symmetric hybrid sliding training method to correct CLDAS daily maximum temperature, reducing its MAE from 1.14 °C to 0.64 °C. Yang et al. [29] applied a linear correction method to CLDAS temperature data in Guizhou Province, lowering the annual RMSE from 1.55 °C to 1.23 °C. A key limitation of these methods is their dependence on a dense observational network, because the station data is utilized to spatially interpolate or adjust the original grid data.

Machine learning algorithms, such as Random Forest and LightGBM, have also been applied to temperature correction. Li et al. [30] used Random Forest to correct the 2-m temperature data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), significantly improving the regional forecast accuracy. Chen et al. [31] proposed a spatiotemporally independent Random Forest model for correcting ECMWF temperature data in Hainan Island, which maintained an MAE reduction of 0.2–0.3 °C even with sparse station data. Fang et al. [32] employed LightGBM with multiple features to construct a high-resolution (0.05° × 0.05°) grid correction model, achieving accurate hourly temperature forecasts in Hubei Province. These methods effectively capture the relationship between air temperature errors and multi-source land surface features, thereby reducing dependency on station spatial distribution, allowing for more efficient bias correction. However, the application of machine learning in temperature correction remains limited. On the one hand, single machine learning often overfits local noise, leading to poor generalization and unstable results. On the other hand, model performance depends on the quality of the input features. The lack of high-spatiotemporal-resolution dynamic surface information prevents the model from accurately capturing the key physical processes that cause temperature errors.

Geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI) integrates geospatial data analysis with artificial intelligence (AI) to extract information from satellite imagery and location-based data, supporting data-driven decision-making in agricultural meteorology, enhancing the capacity to address specific challenges including temperature data bias and rice heat stress under climate change [33]. While traditional machine learning methods possess strong predictive capabilities, they often lack explicit consideration of physical mechanisms, which limits model interpretability and generalizability in complex meteorological scenarios. This study developed a GeoAI framework for temperature correction of CLDAS data and proposed a dual-path model that combines physical mechanisms with data-driven methods. This design ensures that the correction process is not only data-efficient but also grounded in clear geophysical principles, enhancing interpretability and robustness. The physics-guided approach characterizes land–atmosphere interaction mechanisms. The data-driven approach employs an ensemble of XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest to capture complex non-linear relationships between features and temperature errors.

Within the physics-guided approach, a feature set that integrated both dynamic surface observations and static topographic attributes was designed to explicitly represent the underlying physical processes. The dynamic surface metrics derived from FY-4 satellites included the daily maximum Land Surface Temperature (LSTmax) and the diurnal Land Surface Temperature range (LSTmax_min). LSTmax captured the peak thermal state based on the energy balance coupling with air temperature, while LSTmax_min reflected extreme temperature trends and surface thermal inertia. The model also integrated Vegetation Indices, such as Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), which collectively represent vegetation regulation and moisture feedback mechanisms. For static topographic representation, the model utilized a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to quantify the vertical temperature lapse rate, correcting large-scale systematic biases. It further incorporated local terrain features, e.g., slope, aspect, Topographic Position Index (TPI), and Terrain Ruggedness Index (TRI), to capture fine-scale thermal variations caused by topographic heterogeneity.

Within the data-driven approach, the three ensemble learners were synergistically integrated for complementary advantages. XGBoost was used to capture high-order interaction relationships between temperature errors and multi-source features [34,35,36,37]. LightGBM enabled efficient processing of high-dimensional spatiotemporal data [38,39,40,41]. Random Forest helped reduce the overfitting risk caused by extreme error samples [42,43,44,45]. This ensemble strategy significantly enhanced the model’s generalization and computational stability.

Through the combination of physical guidance and data-driven approaches, the model ultimately generated high-precision temperature grids with spatial continuity, temporal consistency, and physical interpretability. The corrected data were subsequently applied to monitor rice heat stress across China, which allowed for a reliable monitoring model to be established, demonstrating the practical value of the proposed GeoAI framework in enhancing agricultural meteorological services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

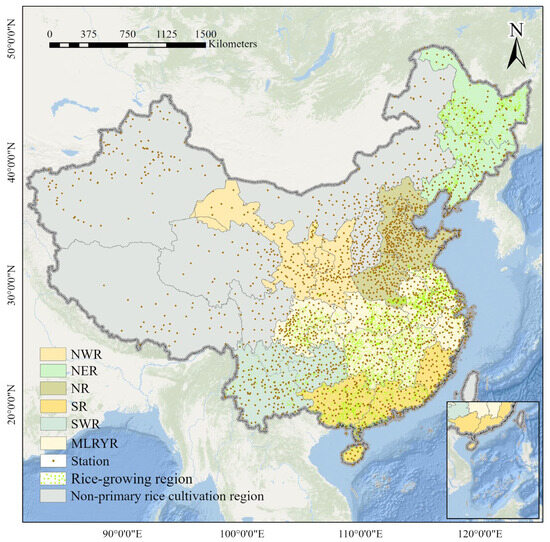

China is the world’s largest rice producer [46]. According to the national rice cultivation regionalization, China is divided into six major rice cultivation zones: the Northeast Region (NER), the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Region (MLRYR), the South Region (SR), the Southwest Region (SWR), the North Region (NR), and the Northwest Region (NWR). In Sichuan, rice cultivation is mainly in the eastern Chengdu Plain and western Sichuan Plateau, known as Sichuan-MLRYR, and Sichuan-SWR, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Major Rice Cultivation Regionalization in China.

2.2. Data

The gridded daily maximum temperature is sourced from the Real-time Product Dataset of CLDAS V2.0 provided by the China Meteorological Administration, with a spatial resolution of 0.0625° × 0.0625°. The data of rice production were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics website, covering the period from 2020 to 2023 (https://data.stats.gov.cn (accessed on 15 October 2023)). FY-4 satellite data, with a spatial resolution of 4 km and a time interval of 15 min, are provided by the China Meteorological Administration. The data primarily includes L1-level observations, as well as derived products such as LST, and Cloud Mask (CLM). DEM data were obtained from GDEMV2 with a spatial resolution of 30 m, sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform at https://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 15 October 2023). The daily maximum temperature from meteorological stations, are downloaded from the China Meteorological Data Service Center (https://data.cma.cn (accessed on 15 October 2023)). These data are provided by 2505 meteorological stations across the country, covering the period from January 2020 to December 2023. The change in rice yield per unit area is calculated by subtracting the rice yield per unit of the previous year from the rice yield per unit of the current year. The heading and flowering stage data of rice were obtained from the National Ecosystem Science Data Center (NESDC), with the official website accessible at (https://nesdc.org.cn/).

2.3. Method

2.3.1. Data Processing

Dynamic surface features were derived from FY-4 satellite multi-band data through a series of preprocessing steps. These included radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, geometric correction, and observation angle correction. To mitigate cloud contamination and enhance data reliability, the Maximum Value Composite (MVC) method was applied [47]. Based on the preprocessed L1-level reflectance data and Land Surface Temperature (LST) products, multiple vegetation indices, including NDVI and EVI, together with surface thermal regime metrics such as LSTmax and LSTmax_min, were subsequently calculated (Table 1). Six key terrain attributes were generated based on DEM. Among these, ASPECT_sin and ASPECT_cos are the sine and cosine transformations of terrain aspect, respectively. All topographic calculations were performed using the GDAL library and ESRI’s spatial analyst tools. Table 1 outlines the calculation methods for key representative features.

Table 1.

Features Calculations.

The FY-4 time series data contains gaps due to cloud cover. We adapted the Self-Attention-based Imputation for Time Series (SAITS) model for gap-filling using PyTorch 2.2.2 as the deep learning framework, with its key hyperparameters configured as follows: 2 network layers (N_layers), a model dimension (D_model) of 128, a feature dimension (D_ffn) of 64, 4 attention heads (N_heads), and a key/value dimension (D_k/D_v) of 32 for each head, paired with a dropout rate of 0.1. This model utilizes a self-attention mechanism to effectively capture complex temporal dependencies and global dynamics in long-term sequences, making it particularly suitable for filling gaps in satellite data. SAITS achieves better performance than leading imputation models across various real-world time series datasets, showing higher accuracy even with substantial missing data (up to 90%) and in high-dimensional settings [48].

2.3.2. Rice Heat Stress Identification

Based on the heat stress thresholds for rice established in previous research [19] (Table 2), the heat stress events were identified and analyzed for each rice-growing pixel. The regional-level metrics for a given year, namely the total number of events and the maximum event duration, were then calculated by summing the occurrences and finding the longest duration across all pixels, respectively.

where Xᵢ represents the value of the i-th pixel; for Equation (1), it denotes the event count, and for Equation (2), it represents the event duration. The variable n is the total number of pixels in the area.

Final HS event occurrences = sum(X1, X2, ……, Xn)

Duration = max(X1, X2, ……, Xn)

Table 2.

Criteria for Grading Rice Heat Stress Events.

2.3.3. Temperature Correction Model

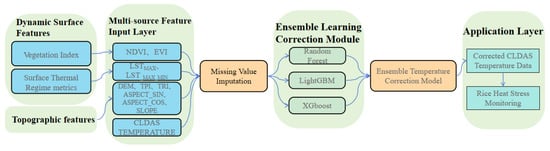

An ensemble learning-based correction model is developed in this study (Figure 2). The model successfully captures complex error distributions by fusing the complementary strengths of XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest (serving as base learners) through a dynamic weighting strategy (Equation (3)). The model uses surface thermal regime metrics (LSTmax, LSTmax_min) and vegetation indices (NDVI, EVI). To reduce the biases in simulations of temperature brought on by terrain heterogeneity, it simultaneously incorporates topographic features (slope, aspect, TRI, and TPI). The output of this model is meteorological station data.

Figure 2.

Structure of Ensemble Model.

The dataset is divided into training and validation sets in a 7:3 ratio. To prevent overfitting, five-fold cross-validation was applied. Hyperparameters for each base learner were optimized via grid search by minimizing RMSE on the validation set (Table 3). The final temperature corrections were produced through a weighted voting fusion method, with weights dynamically determined by each model’s performance on the validation set.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters of the Ensemble Model.

To evaluate the risk of spatial autocorrelation between the training and validation data, we conducted a spatial leakage test using station observations. Randomly sampled station pairs were created, and the spatial distance between each pair was computed using the Haversine formula. A Pearson correlation analysis between station-pair distances and their corresponding error differences yielded a correlation coefficient of 0.045. This negligible correlation indicates that model errors are independent of geographical proximity, confirming the absence of spatial leakage and validating the integrity of the data split as well as the model’s genuine generalization capability.

Statistical indicators including RMSE, MAE, and ACC were employed for model validation and evaluation. To quantify the structural similarity between the corrected temperature grids and the measured data, the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) was adopted for evaluation. Based on human visual perception characteristics, this index quantifies the consistency between two images from three dimensions: luminance, contrast, and structure.

3. Results

3.1. Correction Model Evaluation

3.1.1. Data Imputation

Based on the validation subset of FY-4 satellite data (2020–2023), the SAITS imputation method exhibited stable performance across all years (see Table 4). Specifically, the annual RMSE of imputed results consistently remained within the range of 1.28–1.37 °C. The MAE of the imputation also remained low and stable, with annual averages ranging between 0.92 °C and 1.03 °C. In terms of spatial consistency, the annual mean SSIM of the SAITS-imputed data ranged from 0.85 to 0.89, all falling within the excellent range (0.8–0.9). These results indicate that the imputation method successfully preserves the essential spatiotemporal characteristics of the original gridded data.

Table 4.

Evaluation Metrics of SAITS Imputation for FY-4 Satellite Data (2020–2023).

3.1.2. Model Construction

The corrected CLDAS temperature showed a significant improvement in overall accuracy. As shown in Table 5, the ensemble model outperformed all individual machine learning models across three key evaluation metrics (MAE, RMSE, and ACC). Using only topographic features, the ensemble model achieved an MAE of 0.59 °C, an RMSE of 1.10 °C, and an ACC of 0.97. Compared to the single model with the highest error (Random Forest: MAE 0.69 °C, RMSE 1.20 °C), this represents a reduction of 16.9% in MAE and 8.3% in RMSE. The ensemble’s ACC was also 3.2% higher than the lowest ACC recorded among the single models. When only dynamic surface features were used, the ensemble model’s performance further improved, yielding an MAE of 0.55 °C and an RMSE of 1.05 °C, while maintaining a high ACC of 0.96. These values correspond to an 11.9% reduction in MAE and an 11.2% reduction in RMSE relative to the worst-performing single model under the same input conditions. The best performance was achieved by integrating both topographic and dynamic remote sensing features. In this configuration, the ensemble model attained an MAE of 0.53 °C, an RMSE of 1.04 °C, and an ACC of 0.97. Compared to the maximum MAE (0.69 °C) and RMSE (1.21 °C) from the single models with the same input, the ensemble reduced MAE by 23.2% and RMSE by 14.0%. Its ACC remained 2.1% higher than the lowest ACC among the single models. These results comprehensively confirm that integrating multiple feature types effectively enhances the precision of temperature correction.

Table 5.

Comparison of MAE, RMSE, and ACC for Models with Different Feature Inputs (°C for MAE/RMSE).

3.1.3. Error Analysis

Regional validation confirmed the notable performance of correction models across China’s major rice cultivation zones. The correction model not only significantly reduced temperature errors but also effectively resolved the regional systematic biases present in the original CLDAS data.

Before correction, CLDAS temperature exhibited regional heterogeneity across the rice cultivation zone. The topographically complex SWR showed the most pronounced systematic warm bias, with a mean bias of 0.92 °C and the highest percentage of positive bias stations (66.7%). The NWR also exhibited a moderate warm bias (0.54 °C) with 57.9% of stations showing positive bias. Although the MLRY had a lower mean bias (0.35 °C), over half of its stations (54.4%) still showed positive biases. In contrast, the NR and the NER displayed near-neutral biases (−0.001 °C and −0.04 °C, respectively), indicating better initial agreement between CLDAS and observations in these flat terrain regions.

Following the application of the correction model, all major rice cultivation zones achieved substantial accuracy improvements (Table 6). The most remarkable improvement was observed in the SWR, where the RMSE dropped dramatically from 2.17 °C to 1.11 °C, a decrease of nearly 50% and the ACC increased from 0.94 to 0.97. Similarly, the NWR saw its RMSE decreased from 1.9 °C to 1.3 °C, paired with an ACC rise from 0.91 to 0.98, and in the MLRYR achieved a reduction from 1.62 °C to 1.03 °C, and the ACC increased from 0.88 to 0.98. Even the zones with initially high performance benefited: the NR’s ACC climbed from 0.97 to 0.99, while the NER’s ACC advanced from 0.94 to 0.96. These consistent improvements in both RMSE and ACC across diverse geographical conditions confirm that this model successfully addresses the systematic biases in CLDAS data, providing robust and reliable temperature correction for China’s primary rice cultivation zones and establishing a solid foundation for rice heat stress monitoring.

Table 6.

Evaluation of CLDAS Temperature Correction in China’s Major Rice Cultivation Zones (°C for MAE/RMSE).

3.2. Rice Heat Stress Events

3.2.1. Events Counts

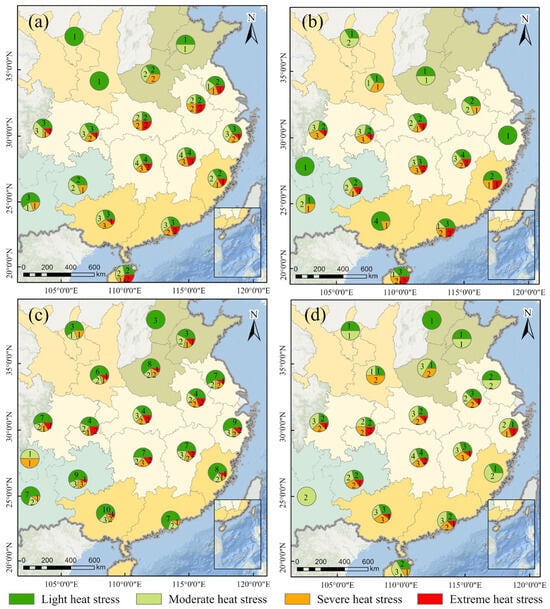

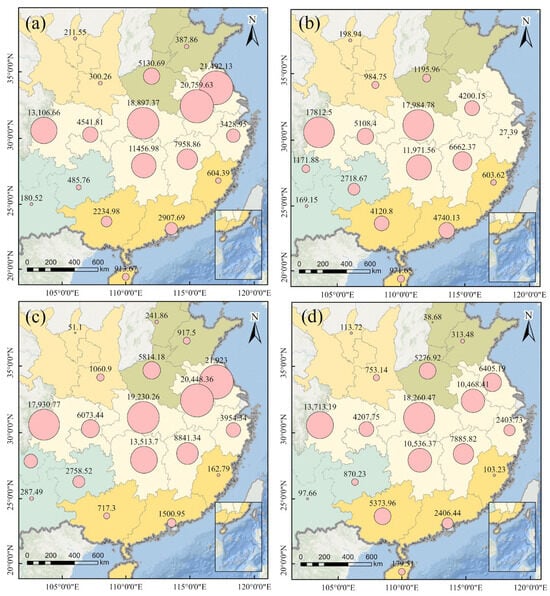

Based on the criteria for grading rice heat stress events and using a pixel-based analysis, occurrences during the heading and flowering stages from 2020 to 2023 in rice-growing regions were identified, and the number of events by province across major rice cultivation zones was summarized (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The number of rice heat stress events by province at the heading and flowering stage of rice-growing region in (a) 2020 (b) 2021 (c) 2022 (d) 2023.

A total of 123 heat stress events were recorded in 2022, making it the year with highest number. The counts of severe and extreme events reached 30 and 23, respectively, far exceeding those in other years. In 2023, 115 events were recorded, with the majority classified as moderate (42) and light (34). The year 2021 experienced the mildest overall intensity, with 96 events in total, including 13 extreme and 22 severe events. In 2020, extreme events were relatively few (only 19), with light (43) and moderate (38) events predominated. Overall, the frequency and severity of heat stress events exhibited significant interannual fluctuations over the four-year period.

Across the rice cultivation zones, the highest number of heat stress events on rice was recorded in MLRYR, with a total of 254 over the past 4 years. In 2022, there were a total of 64 events, including 15 classified as extreme. At the provincial level, the highest total number of heat stress events was 10 occurrences each, recorded in Hunan (2 light, 2 moderate, 3 severe, 2 extreme) and Zhejiang (3 light, 3 moderate, 2 severe, 2 extreme). Except for Jiangsu, all other provinces in the MLRYR experienced two extreme heat stress events. In addition, all provinces in the region except Chongqing experienced two severe events.

The second highest number of heat stress events was observed in SR. Within this region, Guangxi and Guangdong reported the highest four-year totals, with 34 and 31 events, respectively. Both provinces experienced severe events in 2020 and 2021: Guangdong recorded two severe events in each of these years, while Guangxi had three severe events in 2020 and 1 in 2021. Regarding extreme events, Hainan experienced two in 2020 and two more in 2021, but none in 2022 or 2023. Guangdong, which had already recorded two extreme events in 2020, experienced one additional in 2023. Fujian did not experience extreme heat stress events in 2023, though it had one extreme event each in 2020 and 2022. Notably, Guangxi did experience extreme heat stress events during the period (one event in each of 2020, 2022, and 2023), with three severe events in each of 2020 and 2023. These results further confirm that the MLRYR remained the region with the highest frequency of rice heat stress events over the last four years.

3.2.2. Event Duration

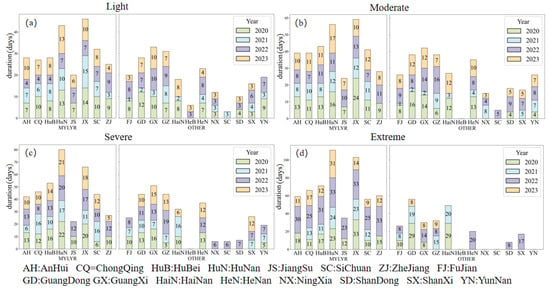

The annual duration of heat stress events by province across major rice cultivation zones is shown in Figure 4. Consistent with the number of heat stress events, the longest duration of the extreme heat stress event occurred in 2022, reaching 33 days. The duration of severe, moderate, and light events was 20, 13 and 10 days, respectively.

Figure 4.

The duration of rice heat stress events by province at the heading and flowering stage of rice-growing region (a) Light (b) Moderate (c) Severe (d) Extreme.

In 2020, the shortest extreme event (8 days) among the four years was recorded in Guangxi, while the longest extreme event that year reached 33 days in Jiangxi. The longest light, moderate, and severe events in 2020 lasted 14 days (Jiangxi, MLRYR), 24 days (Jiangxi, MLRYR), and 22 days (Hunan, MLRYR), respectively. In 2021, the longest heat stress event was an extreme event in Chongqing (MLRYR), lasting 13 days, followed by a severe event in Hunan (MLRYR) at 17 days. For 2023, the longest extreme event reached 31 days in Hunan (MLRYR), while the longest moderate event lasted 17 days (Hunan, MLRYR). Over the four-year period, the longest extreme heat stress events were consistently observed in the MLRYR. In 2022, Jiangxi, Hunan, and Zhejiang (all within the MLRYR) recorded the maximum extreme event duration of 33 days, followed by Hubei (31 days) and Anhui (30 days) in the same region. Other notable prolonged extreme events in the MLRYR included durations of 25 days in Sichuan (2022) and 17 days in Chongqing (2023).

In non-MLRYR regions, the longest extreme heat stress event lasts 29 days, recorded in both Guangdong and Hainan (SR) in 2020. The longest duration reached 21 days in Hunan (MLRYR) in 2023. The longest moderate event (24 days) and light event (14 days) were both observed in Jiangxi (MLRYR) in 2020.

These results confirm that the MLRYR experienced the most protracted extreme heat stress events over the four years, durations substantially longer than those in other regions.

3.2.3. Affected Area

Based on the number of pixels that suffered heat stress events during the heading and flowering stages from 2020 to 2023, the heat-affected rice area was estimated (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Affected area (km2) by province at the heading and flowering stage of rice-growing region in (a) 2020 (b) 2021 (c) 2022 (d) 2023.

In 2020, the heat-affected area varied across regions, with the largest area of 21,492.12 km2 in Jiangsu (MLRYR) and the smallest (180.52 km2) in Yunnan (SWR). In 2021, the distribution of heat-affected areas also varied. Zhejiang (MLRYR) had the smallest affected area (27.38 km2), whereas Hubei (MLRYR) registered the largest, reaching 17,984.77 km2. In 2022, the heat-affected area expanded markedly, with damage concentrated mainly in MLRYR. Jiangsu (MLRYR) experienced the most severe impact, with 21,923.00 km2, followed by Anhui (20,448.36 km2) and Hubei (19,230.25 km2). In 2023, the total heat-affected area decreased compared to 2022, and Hubei (MLRYR) once again became the most impacted region, with 18,260.47 km2 damaged. It is worth noting that although Hainan (SR) had a relatively small heat-affected area, it exhibited a high percentage of heat-affected rice growing area, coupled with high local rice productivity, indicating significant regional vulnerability. Over the four-year period, the MLRYR consistently experienced the largest absolute affected area from rice heat stress.

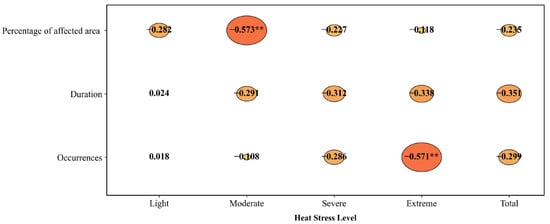

3.2.4. Response of Rice Yield

Figure 6 showed the partial correlation (controlling for rice planting area) between the characteristics of heat stress events and the change in rice yield per unit area. All heat stress metrics showed negative partial correlations with yield change. However, the partial correlation coefficients ranged from −0.57 to −0.28, depending on the severity of heat stress (extreme vs. moderate) and the metric used (event occurrences, duration, and percentage of affected area). Extreme heat stress events demonstrated significant negative correlations with yield change. Specifically, the occurrence of extreme heat stress events was highly correlated with yield change (r = −0.57, p < 0.01, n = 57), indicating that more frequent extreme events directly lead to greater yield losses. For moderate heat stress, yield loss was most strongly associated with the spatial extent of stress. The percentage of affected area showed a highly significant negative correlation with yield change (r = −0.57, p < 0.01, n = 57), indicating that broader spatial extent of moderate heat stress corresponds to more pronounced suppression of rice yield per unit area.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of partial correlation coefficients (r) between change in rice yield per unit area and heat stress event characteristics, by level (**: p <0.01).

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Interpretability

The variable importance analysis was conducted across the base learners (XGBoost, LightGBM and Random Forest), with results summarized in Table 7. These results indicated that the model’s corrections relied on features with clear physical meanings, and that its ensemble strategy effectively integrates distinct mechanisms for correcting physical errors.

Table 7.

The variable importance of Correction Model (%).

The key features were found to possess direct physical significance. The three variables with the highest average importance were the raw CLDAS temperature (36.53%), the target of correction, along with DEM (11.72%) and TPI (9.13%). These correspond to the initial temperature, the elevation effect, and topographic position, respectively, all core factors that govern near-surface air temperature. This result demonstrates that the model’s correction process is grounded in established geophysical principles.

The base learners exhibited complementary correction strategies. Random Forest was heavily reliant on the raw CLDAS temperature (81.11%) and assigned relatively high importance to LST (10.21%). Its correction approach likely focused more on errors related to the raw temperature and surface energy processes. In contrast, XGBoost and LightGBM significantly reduced the weight given to raw data and instead placed greater emphasis on topographic indicators such as DEM and TPI to identify spatially structured errors. They also showed relatively lower dependence on LST (6.83% and 5.61%, respectively). This difference highlights the limitations of any single model in capturing complex error sources. Random Forest was more associated with biases in original data and surface thermal radiation, while the gradient boosting models were more adept at capturing systematic biases driven by topography.

The ensemble framework effectively balanced these physical mechanisms by integrating the strengths of each base learner. It combined Random Forest’s focus on raw temperature bias with the gradient boosting models’ sensitivity to topographically structured errors. This integration reduced the over-reliance on the raw input data seen in Random Forest alone, leading to a more robust correction model. The final ensemble not only achieved higher accuracy but also maintained a clear, physically interpretable structure by addressing error sources from both surface thermal processes and terrain effects.

Furthermore, the model’s foundation in physical mechanisms and its interpretable design support strong generalizability. It is applicable not only to monitor rice heat stress, as validated in this study, but also to assess extreme heat events. With only minor adjustments, the framework can be adapted to monitor meteorological stress in other staple crops such as wheat and maize. This flexibility, together with the model’s interpretability, increases its practical value for agricultural and climate impact assessments across different applications.

4.2. Model Performance

In the research, the integration of topographic features with dynamic surface features (NDVI, EVI, LSTmax, LSTmax_min) notably improved temperature correction accuracy. For Shanxi (NWR), the overall MAE was reduced to approximately 0.9 °C and RMSE to 1.43 °C. Near the Qinling Mountains, MAE was further lowered to 1.02 °C, representing a distinct improvement over the correction for complex terrain reported by Wang [27]. Similarly, in Guizhou, another region with complex topography, the model reduced the RMSE of corrected CLDAS temperature to 0.98 °C, outperforming the 1.23 °C RMSE reported by Yang [29]. These results demonstrate that the proposed model offers better adaptability and accuracy in areas with significant topographic heterogeneity.

However, the corrected CLDAS temperature in the NWR still showed a relatively high RMSE of 1.30 °C compared to other regions. This is closely associated with the region’s complex terrain. As shown in Table 8, there were significant differences in microtopographic relief among China’s major rice-growing regions. The NWR exhibited the most rugged terrain, with a standard deviation of TPI and TRI reaching 197.99 m and 459.23 m, respectively, substantially higher than those of other regions. Because of the CLDAS data’s spatial resolution of 0.0625° (approximately 7 km), elevation differences within a single grid can be hundreds of meters. This resolution is insufficient to capture fine-scale topographic variability, leading to discrepancies between gridded temperature estimates and local conditions, which in turn limits correction accuracy here. This finding is consistent with previous research [28], demonstrating that surface heterogeneity remains a key constraint on improving CLDAS temperature products.

Table 8.

TPI and TRI standard deviation in China’s Major Rice Cultivation Zones (m).

It is noteworthy that even in highly rugged mountainous areas such as the Qinling and Daba Mountains, which share topographic complexity with parts of the NWR, our model still achieved meaningful improvements over the original CLDAS data. In these regions, the proportion of stations with MAE below 2 °C increased significantly from 80% before correction to 93% after applying our ensemble model.

4.3. Effects of Heat Stress on Rice Growth and Yield

Although rice is a thermophilic crop, there are clear temperature thresholds for its growth and development. According to studies, rice growth rates start to decrease when temperatures regularly rise above 32 °C; at or above 35 °C, severe physiological stress (such as excessive transpiration and photosynthetic inhibition) severely impedes development and causes a sharp decline in seed-setting rates during crucial stages like heading and flowering [49,50,51,52]. Additionally, research conducted in China supports a clear association between cumulative high stress and yield loss [53].

A major methodological challenge in evaluating the regional impact of high temperatures lies in separating its influence from other factors. Interannual changes in planting area constitute a crucial confounding variable. While yield per unit area decreases because of heat stress, an expansion in planted area frequently makes up for it at the level of total production, hiding the actual heat-induced harm. The 2020 case of Hunan illustrates this masking effect. Despite numerous recorded heat stress events, a 3.6% expansion in planted area resulted in a 1.05% increase in total yield.

To eliminate the effect of changes in planting area and accurately isolate the direct impact of high-temperature stress on rice production, this study employed partial correlation analysis to control the effect of changes in planting area. The results indicated that various heat stress metrics show stable and significant negative correlations with the yield per unit area. This demonstrates that the heat stress metrics can capture the direct negative impact on rice production, confirming their validity for assessing yield loss.

The correlation analysis presented above confirms that the model’s outputs reliably reflect yield impacts. However, it is important to note that the response of agricultural production to climate is multifaceted. The consequences of heat stress may also be mitigated or exacerbated by other management strategies such irrigation adjustments, cultivar replacement, and phenological adaptation. Furthermore, due to data limitations, the present validation primarily focused on controlling for the compensatory effect of planting area. The multi-year aggregation approach, while ensuring robustness, may also overlook dynamic annual-scale variations. Future research, based on more granular and temporally explicit datasets, could strengthen the validation by incorporating a wider range of adaptive measures and examining interannual variations in model performance, thereby further refining the model’s utility in monitoring climate impacts on agriculture.

5. Conclusions

This research developed an ensemble learning-based correction model integrating XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest to address systematic biases and random errors in CLDAS temperature. Utilizing dynamic surface features from FY-4 satellite products (NDVI, EVI, LSTmax, LSTmax_min) and static topographic features (slope, aspect, TRI, and TPI), the model achieved high-precision corrections, which enabled the monitoring of rice heat stress events in major rice cultivation zones from 2020 to 2023. The principal findings are as follows:

- The ensemble model demonstrated superior performance compared to individual base learners, achieving the lowest RMSE of 1.04 °C, MAE of 0.53 °C, and ACC of 0.97 when integrating both topographic and dynamic surface features. This represents a substantial improvement over single models such as Random Forest (RMSE: 1.21 °C, MAE: 0.66 °C, ACC: 0.95), XGBoost (RMSE: 1.10 °C, MAE: 0.63 °C, ACC: 0.95), and LightGBM (RMSE: 1.07 °C, MAE: 0.65 °C, ACC: 0.96). The progressive enhancement in model performance was evident through feature ablation tests: using only topographic features yielded an RMSE of 1.10 °C, MAE of 0.59 °C, and ACC of 0.97, while the incorporation of dynamic surface features from remote sensing further optimized the metrics to an RMSE of 1.04 °C, MAE of 0.53 °C, and ACC of 0.97.

- The SWR showed the most remarkable improvement, with RMSE decreasing dramatically from 2.17 °C to 1.11 °C, MAE from 1.48 °C to 0.80 °C, and ACC from 0.72 to 0.96. This was followed by the MLRYR, where RMSE dropped from 1.62 °C to 1.03 °C, MAE from 1.00 °C to 0.69 °C, and ACC from 0.88 to 0.98, and the NWR with a reduction from 1.9 °C to 1.3 °C, MAE from 1.24 °C to 0.91 °C, and ACC from 0.91 to 0.98. These substantial improvements were particularly significant given the pronounced systematic warm biases observed in these regions before correction, especially in the topographically complex SWR, which exhibited the highest mean bias (0.92 °C) and positive bias station percentage (66.7%).

- Based on the corrected data for heat stress monitoring, significant spatiotemporal characteristics of rice heat stress events were observed across major China’s rice cultivation zones from 2020 to 2023. Temporally, the year 2022 recorded the highest frequency of heat stress events, with severe and extreme events surging to 30 and 23, respectively. Spatially, the MLRYR is the most severely affected, exhibiting the longest duration of extreme heat stress (up to 33 days in 2022) and the largest affected area. Among provinces in MLRYR, Jiangsu recorded the maximum affected area of 21,923.00 km2 in 2022, which is the highest in China during the study period.

- By analyzing the partial correlation between rice yield change and heat stress characteristics (controlling for the effect of planting area changes), the effectiveness of the corrected data for rice heat stress monitoring was further validated. All heat stress metrics showed negative partial correlations with yield change, with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.57 to −0.28 depending on heat stress severity and metric type. Extreme heat stress event frequency was highly significantly negatively correlated with rice unit area yield change (r = −0.57, p < 0.01, n = 57), indicating that more frequent extreme events directly lead to greater yield losses. For moderate heat stress, the percentage of affected area showed a highly significant negative partial correlation with yield change (r = −0.57, p < 0.01, n = 57), indicating that the broader spatial extent of moderate heat stress corresponds to more pronounced suppression of rice yield per unit area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Han Luo; Methodology, Luo Han and Binyang Yang; Software, Han Luo; Validation, Luo Han and Binyang Yang, Formal Analysis, Luo Han and Binyang Yang; Investigation, Han Luo and Lei He; Resources, Han Luo and Lei He; Data Curation, Han Luo and Binyang Yang; Writing—original draft, Luo Han and Binyang Yang; Writing—review & editing, Yuxia Li and Lei He; Visualization, Binyang Yang; Supervision, Lei He, Dan Tan and Huanping Wu; Project administration, Luo Han Lei He; Funding acquisition, Lei He and Dan Tang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022ZD0119505), the Science and Technology Support Project of Sichuan Province (2024YFFK0414), Chengdu Municipal Regional Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Project (2026-YF11-00042-HZ), Tianfu Granary’Digital Agriculture Sichuan-Chongqing Joint Innovation Key Laboratory-Spark Program Open Research Project (TFSZHH3006), and Fengyun Satellite Application Piot Program (FY-APP-ZX-2023.02).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the National Bureau of Statistics of China for their valuable support throughout the research process. We also extend our special thanks to the Food Security Research and Education Team of Beijing Normal University for providing high-quality rice planting data—including spatial distribution information which laid a critical foundation for the accuracy verification of the rice heat stress monitoring model and the spatial analysis of research results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Su, Q.; Dong, B. Recent decadal changes in heat waves over China: Drivers and mechanisms. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 4215–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhai, P.M.; Zhang, Q. Patterns of regional climate and extreme events changes in China since 1961. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2025, 83, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.X. The influence of human activities on extreme heat exposure events in eastern China. Clim. Change Res. 2025, 21, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Li, B. Changing intensity of hydroclimatic extreme events revealed by GRACE and GRACE-FO. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.X.; Liu, J.J.; Chen, S.H. Applicability evaluation of SMAP, GLDAS and ERA5 soil moisture data in Shanxi Province. J. Agric. Disaster Res. 2025, 15, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Liu, A.G.; Wu, Y.C.; Hu, Y.L.; Zhang, F.F. Temperature Index of High Temperature Harm for Main Crops (GB/T 21985-2008); China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.Z. Heat waves will become the new normal for the Earth in the future. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 41, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, W.Z.; Wang, L.X.; Smith, W.K.; Chang, Q.; Wang, H.; D’odorico, P. Observed increasing water constraint on vegetation growth over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.X.; Wu, Z.F.; Li, M.W.; Gong, Y.F.; Fu, Y.S. Impacts of extreme climate events on autumn phenology in temperate forests of China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 1786–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.; Polo Czá nska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Huo, Z.G.; Wang, P.J.; Wu, D. Occurrence characteristics of early rice heat disaster in Jiangxi Province. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 2020, 31, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L.; Wang, J.H.; Zhang, W.M.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, T.; Pan, Y.Y.; Quan, W.T. Effects of high temperature stress on leaf chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of kiwifruit. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 2021, 32, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Yang, Z.Q.; Wang, L. Refined risk zoning of high temperature and heat damage to greenhouse tomato in southern China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 2021, 32, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.V.V.; Boote, K.J.; Allen, L.H.; Sheehy, J.; Thomas, J. Species, ecotype and cultivar differences in spikelet fertility and harvest index of rice in response to high temperature stress. Field Crops Res. 2006, 95, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.Q.; Yan, N.; Cui, K.H. High temperature damage mechanism of rice spikelet fertility and its cultivation regulation measures. Plant Physiol. J. 2020, 56, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Z.; Yan, H.L.; Liu, K.; Mu, Q.L.; Zhu, K.D.; Zhang, Y.B.; Tian, X.H. Seed setting performance of large panicle rice varieties after high temperature during heading and flowering stage. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2018, 39, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Huang, A.; Yu, L.; Huang, Y.Z.; He, Y.M. Effects of extreme natural high temperature during flowering stage on physiological characteristics of rice anther. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2025, 53, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish, S.V.K.; Craufurd, P.Q.; Wheeler, T.R. High temperature stress and spikelet fertility in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Yao, F.M.; Li, B.B.; Yan, H.; Hou, Y.; Cheng, G.; Boken, V. Research advances in monitoring rice high-temperature heat damage using star-ground optical remote sensing information. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 41, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.J.; Shen, R.P.; Huang, A.Q.; Liang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xie, Z.Y.; Shi, C.X.; Sun, S. Research on integrated drought monitoring model based on MODIS and CLDAS. J. Nanjing Univ. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 16, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.W. Evaluation of Products from CMA Land Data Assimilation System (CLDAS). Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.J.; Shen, R.P.; Shi, C.X.; Xing, Y.J.; Sun, S. Study on rainfall erosivity in China based on CLDAS merged precipitation. Arid Land Geogr. 2022, 45, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.L.; Zhao, Y.L.; Feng, X.J.; Liu, S.M. Applicability analysis of CLDAS temperature and precipitation products in Inner Mongolia. J. Arid Meteorol. 2023, 41, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Deng, B.; Zhou, B.; Sun, R. Application of CLDAS precipitation data in climate evaluation operations in Sichuan Province. Plateau Mt. Meteorol. Res. 2025, 45, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.Q.; Guo, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.Y. Deviation correction method of grid temperature prediction based on CLDAS data. J. Arid Meteorol. 2021, 39, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, F.; Kuang, L. Correction and evaluation of CLDAS air temperature products based on quasi-symmetric hybrid sliding training method. J. Arid Meteorol. 2024, 42, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.P.; Dang, C.Q.; Lou, P.X.; Huang, S.N.; Cai, X.L. Application of CLDAS in test and correction of grid temperature forecast in Shaanxi Province. Meteorol. Mon. 2023, 49, 946–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.X.; Liu, X.W.; Wang, Y.C.; Liu, N.; Zhou, Z.H. Verification and correction of 2 m temperature merging product of CLDAS in Lanzhou and Wuwei, Gansu Province. J. Arid Meteorol. 2024, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Y.; Peng, F.; Yu, F.; Chen, B.L. Applicability evaluation and correction of CLDAS temperature and humidity products in Guizhou. Plateau Meteorol. 2023, 42, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Shi, M.L. Study on EC temperature forecast revision based on random forest. J. Agric. Catastrophol. 2022, 12, 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Ning, Y.K.; Tang, R.N.; Xie, X.F. Tropical temperature correction for numerical forecast in Hainan based on spatiotemporal independence random forest model. Nat. Sci. J. Hainan Univ. 2020, 38, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.B.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, X.L.; Tan, J.H.; Lu, L.B. Gridded temperature forecast correction method based on machine learning. Meteorol. Mon. 2024, 50, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausika, B.B.; van Altena, V. GeoAI in Topographic Mapping: Navigating the Future of Opportunities and Risks. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Li, X.Q.; Yang, Z.; Du, F.H.; Chen, X.M. Comparative analysis of rural water supply risk identification models based on machine learning algorithms. J. China Inst. Water Resour. Hydropower Res. 2025, 23, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.F.; Duan, S.S.; Cao, Y.H.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of grain storage humidity and influencing factors analysis integrating XGBoost and SHAP. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2025, 40, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L. Stepwise Downscaling and Application Research of ERA5-Land Reanalysis Temperature. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.J. Prediction of Heavy Metal Pollution in Water Bodies and Health Risk Assessment Based on Machine Learning. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.M.; Zhou, Q.X.; Cao, P.P.; Wang, J.J. Correction study on 2 m temperature changes during temperature transition processes in Sichuan region. J. Arid Meteorol. 2023, 41, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.C.; Ye, L.F. Research on meteorological data quality control method based on LightGBM. Strait Sci. 2022, 7, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.M.; Huang, W.B.; Li, T.J.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, Y.C. Application of two machine learning models in hourly temperature forecasting in Gansu. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 48, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Ma, F.L.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.K.; Liu, T.; Zhang, L.Y. Correction method of CMA-MESO model temperature prediction based on machine learning. J. Meteorol. Environ. 2025, 41, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.P. Research on Downscaling and Correction Methods of Numerical Temperature Prediction in Mountainous Areas. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.L.; Liu, Y.Y. Hourly prediction of O3 concentration in Changsha City based on random forest model. J. Univ. S. China 2025, 39, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.P. Multi-Scale Monitoring and Early Warning of Wheat Scab Based on Machine Learning. Master’s Thesis, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.N. Research on Short-Term Hourly Temperature Prediction Method in the Three Northeastern Provinces Based on Multi-source Data. Master’s Thesis, Hangzhou Dianzi University, Hangzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.F. Domestic Rice Should Have Adequate Security; Sect. 004; People’s Daily Overseas Edition: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Ma, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; He, L. Validation analysis of drought monitoring based on FY-4 satellite. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.J.; Côté, D.; Liu, Y. SAITS: Self-attention-based imputation for time series. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 219, 119619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, A.M.; Peters, W.; Joetzjer, E.; Lafont, S.; Koren, G.; Ciais, P.; Ramonet, M.; Xu, Y.; Bastos, A.; Botía, S.; et al. Temperature extremes of 2022 reduced carbon uptake by forests in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampe, D.; Zscheischler, J.; Reichstein, M.; O’sullivan, M.; Smith, W.K.; Sitch, S.; Buermann, W. Increasing impact of warm droughts on northern ecosystem productivity over recent decades. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, D.; Wang, R.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, M.; Cai, Y. Effects of temperature fluctuations on the growth cycle of rice. Agriculture 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.L.; Wu, B.W.; Zeng, B.H.; Ouyang, D.M.; Cao, Z.B. Comparative analysis of rice young panicle transcriptome under different high-temperature stress treatments. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2024, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Feng, L.Z.; Ju, H.; Yang, D. Possible impacts of high temperatures on China’s rice yield under climate change. Adv. Earth Sci. 2016, 31, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.