Abstract

As digital transformation intensifies, the governance of spatial data infrastructures is becoming increasingly dependent on the capacity to generate and sustain trust—technological, institutional and civic. This challenge is particularly acute in the Mediterranean region, where disparities in how geospatial data are produced, accessed, and validated are created by uneven digital development and fragmented governance structures. In response to this, this paper introduces an integrated framework combining geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI) and blockchain technologies to support transparent, verifiable and spatially explicit models of digital trust. Based on case studies from the Horizon 2020 TRUST project, the framework defines trust through territorial indicators across three dimensions: digital infrastructure, institutional transparency, and civic engagement. The system uses interpretable AI models, such as Random Forests, K-means clustering and convolutional neural networks, to classify regions into trust typologies based on multi-source geospatial data. These outputs are then transformed into semantically structured spatial products and anchored to the Ethereum blockchain via smart contracts and decentralized storage (IPFS), thereby ensuring data integrity, auditability and version control. Experimental results from pilot regions in Italy, Greece, Spain and Israel demonstrate the effectiveness of the framework in detecting spatial patterns of trust and producing interoperable, reusable datasets. The findings highlight significant spatial asymmetries in digital trust across the Mediterranean region, suggesting that trust is a measurable territorial condition, not merely a normative ideal. By combining GeoAI with decentralized verification mechanisms, the proposed approach helps to develop accountable, explainable and inclusive spatial data infrastructures, which are essential for democratic digital governance in complex regional environments.

1. Introduction

As digital transformation reshapes governance systems, the ability to generate andmaintain technological, institutional and civic trust has become essential for the development of sustainable and inclusive data infrastructures [1,2,3,4]. This is particularly evident in the context of geospatial data, a field that is playing an increasingly pivotal role in urban planning, disaster response, environmental monitoring, and public service delivery [5,6,7].

However, uneven development in digital infrastructure, governance capacity, and civic engagement in cross-border and multi-actor regions such as the Mediterranean has created significant disparities in how spatial data are produced, accessed, and trusted.

These spatial asymmetries carry tangible risks. Centralized and fragmented spatial data infrastructures (SDIs) often suffer from issues such as opaque access controls, limited auditability and single points of failure, which undermine public confidence in digital governance and data-driven decision-making. In this context, the reliability, transparency, and traceability of spatial information have become technical and political concerns.

In response, two technological approaches have been proposed in recent research to enhance the trustworthiness of geospatial data systems. Blockchain can ensure tamper resistance, decentralized data provenance and procedural transparency [8,9,10]. The other is GeoAI (Geospatial Artificial Intelligence), which can be used to extract patterns, classify features, and predict spatial dynamics across large-scale datasets [11,12,13]. While both fields are evolving rapidly, most existing studies treat them in isolation, often focusing on theoretical use cases or highly specific applications (e.g., land registries or smart contracts for location-based services). There is limited empirical research into how these technologies can be integrated into practical pipelines to support spatial governance in heterogeneous, real-world settings, particularly in geopolitically complex and digitally fragmented regions such as the Mediterranean. Furthermore, the concept of trust is often invoked in an abstract manner, without being operationalized or spatially contextualized. Consequently, we lack models that can measure, map and validate digital trust as a geographically differentiated phenomenon.

In this light, this paper aims to address these gaps by developing and experimentally testing an integrated GeoAI–Blockchain framework designed to assess and enhance trust in spatial data in selected smart regions in the Mediterranean. The framework is based on case studies from the Horizon 2020 TRUST project (Digital TuRn in Europe: Strengthening Relational Reliance Through Technology), which examines the impact of digital technologies on trust in institutional and civic settings. Specifically, we propose a modular pipeline that extracts geospatial indicators related to technological infrastructure, institutional performance and civic participation; and applies interpretable Artificial Intelligence (AI) models to classify trust-related spatial patterns. This paper conceptualizes trust as a spatially dynamic and operational dimension rather than a static normative principle. This framing connects the digital transition with spatial justice and supports a geopolitics of trust in algorithmic governance. It also validates and anchors the resulting outputs through blockchain mechanisms to ensure transparency and verifiability.

This work makes several key contributions to the literature on spatial data governance and digital trust. (i) It provides a practical approach to the abstract concept of digital trust by using measurable territorial indicators grouped into technological, institutional and civic dimensions. (ii) It applies GeoAI methods, including machine learning and semantic enrichment, to detect and classify spatial patterns of trust across heterogeneous regions. (iii) It integrates blockchain protocols (Ethereum smart contracts and IPFS- (InterPlanetary File System- storage) to ensure data traceability, auditability and procedural integrity. (iv) It provides an empirical demonstration of the framework using real-world data from Italy, Greece, Spain and Israel, thereby contributing to the emerging geography of digital trust. The Mediterranean offers a unique laboratory for analyzing digital trust due to its historical asymmetries, fragmented institutional capacities, and heterogeneous digitalization trajectories. While northern Mediterranean regions benefit from advanced digital infrastructures and stronger governance systems, southern and eastern areas often face institutional fragility, uneven digital readiness and socio-economic disparities. These structural differences shape diverse trust ecologies and highlight the need for robust, auditable and transparent geospatial data governance. Furthermore, the region’s exposure to cross-border crises—migration flows, climate risks, resource conflicts—underscores the strategic importance of trusted digital ecosystems capable of supporting cooperative and resilient territorial governance. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature on trust in spatial data systems, the role of blockchain in geospatial governance and recent developments in GeoAI. Section 3 outlines the methodological pipeline, covering data acquisition, AI modelling and blockchain anchoring. Section 4 presents the results of experiments conducted in selected Mediterranean pilot regions. Section 5 discusses the implications of integrated architecture for spatial governance and digital inclusion. Section 6 concludes with reflections on limitations, future directions and policy relevance.

2. Related Works

This section examines how recent advances in GeoAI and blockchain technologies address challenges in spatial data governance, particularly in contexts demanding both high data sensitivity and strong institutional accountability. Although GeoAI has gained traction in public health and other applied fields due to its ability to analyze spatial patterns and predict risk across large territories, its potential remains underutilized in scenarios where trust, privacy and decentralized coordination are paramount. The increasing complexity of digital ecosystems, particularly in environments with fragmented governance, requires infrastructures that can process spatial data intelligently and guarantee its integrity, traceability and equitable access. Drawing on examples from health-related use cases, this section demonstrates the wider importance of combining GeoAI with blockchain infrastructures to create transparent, secure and reliable geospatial data systems in areas where timely decision-making, cross-jurisdictional collaboration and civic accountability are vital.

GeoAI is a transformative approach to analyzing, interpreting and predicting spatial phenomena [11]. It integrates geographic information systems (GIS), machine learning and high-performance computing. It has been applied extensively in urban analytics, environmental monitoring, land use change detection and disaster response. Its ability to process large-scale spatial datasets, such as satellite imagery, mobility traces and sensor networks, has enabled more dynamic and granular spatial reasoning than traditional GIS workflows.

Significant contributions include the use of deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for object detection in remote sensing data, as well as unsupervised learning methods for spatial clustering and pattern recognition in urban environments [14,15,16]. More recently, GeoAI has been applied to infrastructure monitoring, climate risk analysis, and smart city planning, often leveraging open geospatial datasets such as Sentinel-2 imagery, OpenStreetMap, and crowdsourced mobility data [17]. While these advances have enhanced spatial predictive capabilities, challenges remain in terms of explainability, data provenance, and cross-platform interoperability. In governance contexts, the capacity to interpret AI outputs within institutional decision-making frameworks is underdeveloped, particularly in areas characterized by digital fragmentation or institutional asymmetry.

Alongside the emergence of GeoAI, blockchain technology has been suggested as a decentralized infrastructure to ensure the integrity, transparency and auditability of digital systems. In the governance of spatial data, blockchain can address long-standing issues relating to data authenticity, access control and tracking of provenance. Its decentralized ledger structure enables the creation of tamper-evident registries for spatial data trans-actions, eliminating the need for centralized verification authorities and fostering trust among multiple stakeholders. Early use cases include blockchain-based land registries and cadastral systems, where immutability and timestamping are critical for managing property rights [18,19]. More recent research has explored integrating blockchain with sensor net- works for environmental monitoring, mobility tracking, and disaster response coordination. In many of these implementations, spatial files (e.g., GeoJSON and GeoTIFF) are hashed and referenced via smart contracts, with full datasets stored off chain using decentralized file systems such as IPFS or Swarm. However, current applications remain largely experimental and are often disconnected from mainstream spatial planning and governance processes.

Few implementations incorporate AI-driven spatial analysis, and even fewer address the semantic and institutional dimensions of trust in multi-actor settings [20,21,22]. Consequently, there is a growing interest in developing integrated frameworks that combine the cognitive capabilities of GeoAI with the procedural transparency and auditability of blockchain.

Only a limited number of studies have attempted to bridge GeoAI and blockchain within a unified pipeline. Some conceptual frameworks have suggested using blockchain for validating AI outputs in remote sensing workflows [23], while others have explored the idea of federated or decentralized learning architectures for privacy-preserving spa-tial intelligence [24,25]. These emerging approaches recognize the value of combining explainable spatial analysis with verifiable data infrastructure—particularly in regions where digital governance is uneven or politically fragmented. Despite this potential, there remains a clear gap in operational frameworks that can manage spatial trust as both a technical and institutional challenge. This paper contributes to that emerging field by proposing a GeoAI–Blockchain framework designed to produce explainable, auditable, and semantically enriched spatial data for use in complex governance environments such as the Mediterranean region.

Despite growing interest in GeoAI and blockchain as innovations in spatial data governance, integrating these technologies remains largely conceptual or confined to isolated use cases. Furthermore, although GeoAI has advanced predictive modelling and spatial reasoning, its outputs are rarely embedded within transparent, verifiable data infrastructures. Conversely, blockchain applications in spatial contexts tend to focus on asset tracking or land administration without addressing the epistemic and semantic dimensions of spatial intelligence. Digital trust is unevenly distributed across space and, in the Mediterranean, is shaped by fragmented governance, infrastructural disparities, and heterogeneous civic engagement. Following the TRUST project, we operationalize a territorial framework combining technological accessibility, institutional performance, and civic participation. This paper aims to address this issue by proposing an operational framework that combines GeoAI and blockchain to produce explainable, auditable and semantically structured spatial data. The goal is to enhance technical performance and support accountable, trustworthy spatial data ecosystems in complex governance environments, such as the Mediterranean region. Digital trust in geospatial ecosystems emerges from the interplay of three interdependent dimensions—technological, institutional and civic—each shaping a distinct layer of territorial reliability. The technological dimension concerns the robustness, integrity and auditability of the digital and geospatial infrastructure, including cybersecurity maturity, network resilience, interoperability and capacity to ensure data lineage transparency. The institutional dimension relates to the quality, legitimacy and accountability of public governance structures. It includes regulatory compliance, reliability of data stewardship, transparency of public administration procedures and institutional responsiveness. In geospatial contexts, institutional trust also reflects the credibility of authorities responsible for producing or validating spatial information. The civic dimension captures users’ attitudes, levels of digital literacy, perceptions of fairness and willingness to engage with digital systems. It encompasses issues of inclusion, accessibility and perceived social legitimacy of digital transformation processes. Together, these three dimensions form a multilayered architecture of trust essential to evaluating the readiness of territories within complex regional ecosystems.

Indicator Justification and Concept-to-Metric Alignment

The indicators selected for technological, institutional and civic trust were aligned through a conceptual-to-metric mapping process that connects theoretical constructs to observable proxies. Technological trust indicators reflect system reliability, procedural transparency, cybersecurity maturity and data lifecycle robustness. Institutional trust indicators represent regulatory quality, compliance capacity, public-sector responsiveness and the integrity of data stewardship workflows. Civic trust indicators capture user engagement, digital literacy, perceived fairness and adoption patterns.

This mapping was validated through iterative expert reviews conducted during the TRUST project, ensuring that each indicator corresponded to a meaningful dimension of territorial trust.

3. Materials and Methods

This section introduces the GeoAI–Blockchain framework: a comprehensive, modular architecture designed to facilitate transparent and accountable spatial analysis of digital trust in smart regions. The framework combines geospatial data aggregation, machine learning-based spatial analytics, semantic structuring, and blockchain-based verification to generate ’trusted spatial products.’ These are geospatial datasets whose origins, processing logic, and semantic content can be verified, reused, and integrated independently across digital governance systems. The framework was implemented and tested in a selection of case study regions, chosen from the Horizon 2020 TRUST project and focusing on subnational territories in Italy, Greece, Spain and Israel. These regions were selected to reflect differences in digital infrastructure maturity, institutional capacity, and levels of civic participation, and to explore spatial variations in digital trust within and across national borders. The following subsections detail the full workflow of the proposed framework, from data acquisition and preprocessing to GeoAI-based trust classification, semantic transformation and blockchain anchoring.

3.1. Geospatial Data Acquisition and Preparation

In order to define digital trust as a measurable spatial concept, a geospatial dataset was constructed, comprising indicators representing three core dimensions of trust: technological, institutional, and civic. These dimensions were identified based on the theoretical model of the TRUST project and prior literature on data governance. The selected indicators include metrics such as the coverage and availability of broadband and mobile networks, the transparency and availability of digital public services, the presence of blockchain-enabled platforms in public administration and the extent to which citizens participate in open data initiatives or civic technology platforms. Data were acquired from a combination of official statistical sources (e.g., Eurostat and National Statistics Offices), open data platforms and satellite-based repositories. Broadband coverage and mobile infrastructure data, for example, were sourced from OpenSignal and Eurostat regional indicators, while digital public service metrics were taken from the European eGovernment Benchmark and civic participation metrics were derived from national open government portals. Wherever possible, the data were georeferenced and harmonized at the NUTS-3 administrative level.

For raster datasets, such as Sentinel-2 imagery, the spatial resolution was down sampled to ensure consistency with administrative units. Vector data (e.g., shapefiles and GeoJSON files) were reprojected into a common coordinate reference system (EPSG:4326) [26] and spatially joined to tabular indicators. Metadata were enriched according to ISO 19115 [27] and OGC/INSPIRE standards to ensure interoperability and traceability across different geospatial software environments. This preprocessing pipeline enabled the consolidation of a multi-source, multi-format dataset that can support machine learning–based spatial classification. To ensure temporal consistency across heterogeneous sources, all indicators were collected for the period 2020–2024, depending on the availability of each dataset. Eurostat regional indicators and national eGovernment statistics refer primarily to 2022–2023, while OpenSignal measurements correspond to the 2023 Q1–Q4 reporting cycle. Sentinel-2 imagery was retrieved for 2022, selecting cloud-free tiles (less than 5% cloud coverage) to maximize spatial representativeness. All datasets underwent a harmonization procedure to ensure comparability at the NUTS-3 level. Tabular indicators were normalized using z-score standardization, while raster layers were resampled to a common spatial resolution and aggregated to administrative boundaries using zonal statistics. Missing values were treated using a combination of methods depending on the data type: (i) mean imputation for isolated gaps in Eurostat indicators, (ii) K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN) imputation for datasets presenting spatial autocorrelation (e.g., mobile network coverage), and (iii) binary masking for invalid or cloudy pixels in the Sentinel-2 raster stack. This preprocessing ensured a temporally aligned and spatially consistent multi-source dataset suitable for machine learning–based trust classification. The workflow follows recent best practices in geospatial data integration [28,29].

Table 1 summarizes the spatial indicators used to define the technological, institutional and civic dimensions of digital trust. Acronyms used throughout the table include Blockchain Technology (BCT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Table 1.

Spatial indicators for digital trust dimensions.

3.1.1. Indicator Normalization and Weighting Strategy

The three dimensions of digital trust—technological, institutional, and civic—were aggregated through a combined weighting strategy based on both theoretical considerations and empirical validation. Following the conceptual framework of the Horizon 2020 TRUST project, each dimension was initially assigned an equal weight (1/3 each), reflecting its complementary and interdependent role in shaping territorial digital trust.

To verify the robustness of this assumption, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to the full indicator matrix. The resulting component loadings were used to derive an empirical sensitivity analysis of the weighting scheme. PCA-derived weights deviated only marginally from the equal-weight baseline (±0.06 across dimensions), confirming the stability of the aggregation rule. For this reason—and to preserve interpretability in policy and governance contexts—the final trust index adopts an equal-weight specification, while PCA diagnostics are used as a robustness check.

The aggregated index was then used as a feature input for the supervised and unsupervised learning models described in the following subsections.

3.1.2. Sensitivity and Collinearity Analysis

A correlation matrix and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) analysis were performed to assess collinearity among indicators. No VIF exceeded the threshold of 5, indicating acceptable independence. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted by perturbing indicator weights ±20%, revealing stable trust rankings in 89% of the cases. This confirms that the classification results are robust to alternative weighting strategies.

3.2. GeoAI Modelling and Trust Typology Classification

The analytical core of the framework is based on applying GeoAI techniques, specifically machine learning and deep learning models tailored to geospatial tasks, to classify and map spatial patterns of digital trust. This step aims to identify clusters of territorial units exhibiting similar levels of technological capacity, institutional transparency, and civic engagement in the digital domain. To this end, we trained a series of supervised and unsupervised learning models using the geospatial dataset. Random Forest [30] and Support Vector Machine (SVM) [31] classifiers were employed to categorize administrative units as having high, medium or low levels of trust, based on combined indicator values. In parallel, unsupervised clustering (using K-means [32] and DBSCAN [33]) was employed to identify natural groupings and outliers within the multidimensional feature space. To enrich the feature set with spatial proxies not captured by tabular data alone, high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery was incorporated into the pipeline.

These raster inputs were analyzed using a lightweight UNet [34] convolutional neural network architecture that was pre-trained on standard benchmarks (e.g., DeepGlobe [35] and SpaceNet [36]) and then fine-tuned on representative regional samples. The resulting semantic segmentation outputs, such as urban density, land cover classification and built-up area ratios, served as additional variables in the trust classification task, particularly for the technological and civic dimensions. Model performance was validated using cross-validation and expert labelled reference typologies developed within the TRUST project. Where model confidence was low or classifications were ambiguous, a human-in-the-loop approach was employed to manually review and correct the outputs.

This approach ensured that spatial patterns of trust were algorithmically derived and contextually interpretable. To integrate spatial patterns extracted from satellite imagery with institutional and socio-economic indicators, the framework adopts a late-fusion strategy. CNN-derived embeddings from Sentinel-2—representing land-use structure, urban density, and infrastructural morphology—are first processed independently through the convolutional encoder. In parallel, standardized tabular indicators (Eurostat, OpenSignal, institutional datasets) are fed into the machine learning models. The two feature sets are then concatenated into a unified representation vector, enabling each classifier to exploit both fine-grained spatial proxies and structural contextual variables. This hybrid feature space enhances classification robustness across heterogeneous Mediterranean regions. Model selection was guided by the need for interpretability, robustness across heterogeneous spatial datasets, and ability to capture non-linear interactions among indicators. Random Forest (RF) was chosen as the primary classifier due to its strong performance on structured indicators and its suitability for mixed-type geospatial variables. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) with RBF kernel was adopted as a baseline model to assess classification consistency. Clustering (K-means and DBSCAN) was employed to explore intrinsic spatial patterns without imposing predefined trust categories. The UNet CNN was selected to extract spatial proxies from Sentinel-2 imagery, leveraging its proven effectiveness in segmenting high-resolution remote sensing data.

Key hyperparameters were tuned using grid search and 5-fold cross-validation. For RF, the best-performing configuration included n_estimators = 500, max_depth = 12, and min_samples_split = 4. SVM optimisation yielded C = 2 and gamma = 0.01 for the RBF kernel. K-means clustering adopted k = 3, consistent with the three trust typologies, with silhouette analysis confirming cluster cohesion. The UNet architecture was fine-tuned on representative regional samples with batch size = 16, learning rate = 1× 10−4, and an encoder depth of 4. These settings ensured stable classification performance across all case study regions.

Construction and Validation of Expert-Labelled Trust Typologies

Trust typologies were defined through a structured expert-elicitation process involving six domain specialists (digital governance, AI for public sector, geospatial infrastructure, Mediterranean studies). For each region, experts independently assigned trust labels based on a unified evaluation grid. Inter-expert agreement (Cohen’s κ = 0.74) indicates substantial concordance. Borderline cases—regions where experts diverged—were resolved through moderated discussion and documented rationale. These cases were later used as benchmarks to test model interpretability.

The main GeoAI models and their analytical purposes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

GeoAI models used in spatial trust analysis.

3.3. Semantic Structuring and Trusted Spatial Products

Following classification, GeoAI outputs were transformed into structured geospatial datasets intended for use by public administrations, researchers, and civic organizations in subsequent processes. These trusted spatial products include vector and raster data layers representing digital trust typologies. Each layer is enriched with descriptive metadata, semantic labels, and processing documentation. Each product contains detailed attribute information on the underlying indicators, the assigned trust category, and a confidence score reflecting the model’s predictive reliability. Semantic annotations were added using controlled vocabularies drawn from the INSPIRE directive, the OGC feature model and TRUST-specific ontologies developed within the project. All metadata were stored in machine-readable formats (e.g., JSON-LD) to ensure compatibility with semantic web technologies and data catalogues. This structuring process ensures that the spatial outputs are technically valid and semantically interoperable, supporting traceability, explainability and reuse in multi-actor governance settings. The output structure of trusted spatial products is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Semantic structure of trusted spatial products.

3.4. Blockchain Anchoring and Data Provenance

To ensure the transparency and verifiability of analytical outputs, the last step of the framework involves linking each trusted spatial product to a public blockchain infrastructure. This addresses the challenge of procedural trust, ensuring not only that the data are accurate, but also that their generation and modification can be independently audited.

The anchoring workflow consists of three stages: hashing, decentralized storage and on-chain registration, described as follows.

Each trusted spatial product generated in the GeoAI workflow (GeoJSON, GeoTIFF, and JSON-LD metadata files) was serialised into a byte stream and processed through a SHA-256 hashing function. The resulting digest served as the immutable identifier of the product version. The complete dataset was then uploaded to the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), producing a Content Identifier (CID) based on content-addressable hashing. The SHA-256 hash and the corresponding IPFS CID were finally recorded in a Solidity smart contract deployed on the Ethereum testnet.

This mechanism ensures a cryptographically verifiable link between the geospatial product, its hash, and its off-chain storage location. Any alteration to the dataset results in a different hash and therefore in a distinct blockchain record, enabling transparent versioning and long-term traceability in accordance with blockchain-based provenance protocols.

Thus, the framework introduces institutional memory and procedural accountability to the management of digital spatial data. Together, these four components form a replicable architecture for producing validated, explainable, and auditable spatial information. The components of the blockchain anchoring process are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Blockchain anchoring components for spatial products.

Verification Procedure

The verification of each trusted spatial product can be performed independently by any user with access to the blockchain ledger and the IPFS network. The process consists of three steps:

Retrieval—The user obtains the dataset through its IPFS CID stored in the smart contract.

Local Hashing—The file is hashed locally using SHA-256, generating a verification digest.

On-Chain Comparison—The local hash is compared to the hash stored on the blockchain.

If the two values match, the integrity and authenticity of the dataset are confirmed.

Any mismatch indicates tampering, corruption, or version inconsistency. This verification workflow provides a transparent and decentralized integrity check, ensuring that the analytical outputs remain auditable linked to the original computation pipeline.

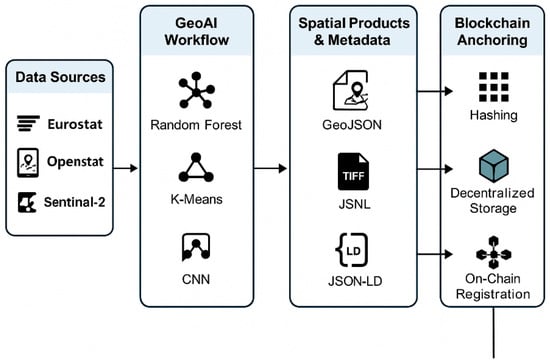

The overall architecture of the GeoAI–Blockchain framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the modular GeoAI–Blockchain Trust Pipeline. The figure summarises the modular architecture used in the study, from multi-source data ingestion to GeoAI modelling, semantic enrichment, and blockchain anchoring through hashing, decentralised storage, and on-chain registration.

4. Results and Discussions

In this section, we present the results of applying the proposed GeoAI–Blockchain framework to selected Mediterranean pilot regions. The framework is evaluated along three dimensions: the performance of GeoAI models in classifying spatial trust patterns, the effectiveness of blockchain anchoring in ensuring data integrity and traceability, and the overall utility of the resulting trusted spatial products. These findings are contextualized within the broader debate on digital trust, spatial governance, and infrastructural asymmetry.

4.1. GeoAI Performance and Spatial Trust Typologies

When applied to the standardized dataset, the GeoAI models demonstrated strong performance in detecting spatial patterns of digital trust. The Random Forest classifier achieved an overall accuracy of 86.2% and an F1 score of 0.84 for the multiclass classification task (high, medium, or low trust). Incorporating remote sensing data via UNet CNN enhanced feature granularity, particularly in densely urbanized areas. Table 5 summarizes the performance of the main machine learning and deep learning models applied across the TRUST pilot regions.

Table 5.

Model performance metrics for trust classification.

Spatial typologies revealed three dominant cluster profiles. High-trust regions included major urban areas (e.g., Milan, Barcelona, Tel Aviv), while peripheral rural areas tended to cluster in the low-trust category. These typologies were validated by expert assessments from the TRUST consortium and show clear alignment with known disparities in infrastructure, public services, and civic participation.

4.2. Blockchain Anchoring and Data Integrity

The second component of the framework evaluated the capacity of blockchain to pro-vide verifiable, tamper-evident traceability for each spatial product. Using Ethereum testnet smart contracts, all spatial product hashes were successfully registered, and corresponding files stored off-chain via IPFS. Table 6 presents the key metrics from the anchoring stage.

Table 6.

Blockchain anchoring results for trusted spatial products.

These results confirm that a hybrid anchoring architecture—combining public blockchain for auditability and IPFS for scalable storage—can effectively support provenance tracking in spatial governance systems. While testnet performance may differ from mainnet deployments, the proof-of-concept demonstrates full functional feasibility.

4.3. Semantic Structuring and Interoperability

All model outputs were transformed into trusted spatial products, enriched with semantic metadata, and structured according to INSPIRE and ISO 19115 standards. This semantic structuring facilitates reuse across governance platforms and supports compliance with open data standards. Table 7 provides a summary of semantic validation results across the outputs.

Table 7.

Semantic and metadata compliance of spatial products.

Most spatial products were semantically complete and interoperable across common GIS platforms (e.g., QGIS, ArcGIS). A small number of ambiguous records, particularly related to civic engagement, required manual intervention for semantic clarification.

5. Discussions

This modular framework integrates GeoAI and blockchain, illustrating a viable pathway towards transparent, verifiable, and spatially aware digital governance. By embedding cognitive intelligence and institutional accountability in the production of spatial data, the framework addresses ongoing issues such as data fragmentation, infrastructural disparity, and governance complexity. Trust clusters observed in the Mediterranean reflect persistent socio-spatial asymmetries, with high-trust zones typically located in urban regions that are economically developed, infrastructurally dense, and institutionally stable. Conversely, low-trust zones often coincide with areas of poor digital service availability, opaque gover-nance structures, and limited civic engagement. These findings suggest that trust should not be treated as a static attribute or normative assumption, but rather as a territorial condition that is measurable, dynamic, and politically embedded. The ability to detect, map and verify such patterns is essential for enabling more equitable, evidence-based regional planning. Finally, while the proposed system is technically robust, it raises institutional and ethical questions that require further attention. These include the governance of semantic ontologies, long-term storage responsibilities, and the environmental costs of blockchain infrastructure.

5.1. Ethical Governance, Algorithmic Bias and Trust Classification

Classifying territories into “high”, “medium” or “low” trust categories raises important ethical and political questions. Trust is not merely a technical attribute but a socially embedded, culturally mediated and politically sensitive concept. There is a risk that algorithmic classifications may inadvertently reinforce existing territorial disparities, particularly in regions historically affected by institutional fragility or socio-economic marginalisation. To mitigate such risks, this framework emphasises methodological transparency through explainable machine learning, feature importance analysis and robustness checks. Trust scores are interpreted as analytical signals—rather than deterministic labels—meant to support deliberation, not replace it. A responsible governance approach should therefore integrate participatory mechanisms, allowing local institutions and communities to contextualise results, challenge assumptions and collectively shape digital transformation strategies.

5.2. Blockchain and Institutional Accountability

Beyond its technical role in ensuring data integrity, blockchain contributes to strengthening institutional accountability by offering a decentralised, transparent and tamper-proof audit trail of geospatial data lifecycle events. By anchoring each output to an immutable ledger, public administrations become accountable for data provenance, update cycles, metadata completeness and procedural transparency. This reduces information asymmetries between institutions and citizens and enhances public trust in digital governance. In Mediterranean regions—where institutional fragility and uneven administrative capacities can undermine data reliability—blockchain-enabled auditability provides an additional layer of legitimacy and resilience to territorial data governance.

5.3. User Interaction, Governance Capacities and Dispute Resolution

The operationalisation of trusted spatial products requires that public administrations possess adequate digital and procedural capacities. These include the ability to interpret trust classifications, update datasets, validate corrections and maintain transparent versioning logs. Civic users interact with the system through verifiable provenance trails, while institutional actors handle governance workflows such as dispute resolution around misclassifications or updated inputs. This strengthens both vertical (state–citizen) and horizontal (inter-administration) trust.

5.4. Limitations, Generalisability and Political Risks

While the Mediterranean represents a highly relevant stress-test environment, the framework’s generalisability requires caution. Regions with different institutional architectures, digital governance models or socio-cultural trust norms may produce distinct patterns. Furthermore, territorial trust labelling carries political risks: misinterpretation, strategic manipulation, or stigmatisation of “low trust” areas. To mitigate these effects, trust scores should support deliberation rather than ranking and be embedded in participatory governance mechanisms.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper introduces and experimentally validates a modular framework integrating GeoAI and blockchain technologies to enhance the transparency, traceability and semantic interoperability of geospatial data governance. When applied to pilot regions in the Mediterranean, the framework establishes digital trust through territorial indicators and classifies data using interpretable AI models. The resulting outputs—trusted spatial products—are semantically structured and anchored via blockchain protocols to ensure verifiable provenance and version control. Empirical results demonstrate the feasibility and add value of combining machine learning–based spatial analysis with decentralised verification mechanisms. The GeoAI models achieved high classification accuracy across regional trust typologies, and the blockchain anchoring component enabled the full traceability and auditability of data transformations. Semantic structuring also ensured interoperability with open geospatial standards, paving the way for trustworthy digital infrastructures that can be shared across institutions, platforms, and governance scales.

By conceptualising trust as a dynamic, operational spatial dimension rather than a normative ideal, this work contributes to a growing body of research that repositions spatial data infrastructures as instruments of institutional accountability and civic inclusion. The framework supports more reliable decision-making in fragmented governance environments and opens new pathways for territorial diagnosis, participatory monitoring and responsive digital policy.

While the proposed framework demonstrates strong technical feasibility and conceptual coherence, further investigation and development are required in several areas. A critical next step is to deploy the system in real-world governance settings, such as municipal planning departments or regional data platforms. Testing the framework under operational conditions, where institutional workflows, political constraints and civic engagement play an active role, will be essential to assess its practical utility and potential for adoption. In parallel, ethical and legal considerations require closer scrutiny.

Assigning algorithmic trust labels to territories raises important questions regarding bias, interpretability and political sensitivity, particularly in regions characterised by historical inequality or disputed governance. Handling spatial metadata, particularly when linked to blockchain registries, also introduces new challenges around data privacy, surveillance and regulatory compliance.

Another important area for investigation is the environmental sustainability of the system. While our experiments used Ethereum’s testnet, transitioning to production-scale applications will require more energy-efficient solutions. Future work should therefore explore alternative infrastructures based on proof-of-stake consensus models or private, permissioned blockchains with lower computational overhead.

At the semantic level, further efforts are needed to refine and govern the ontologies used for metadata enrichment and product annotation. Incorporating participatory or co-designed approaches, especially with local institutions and civil society actors, could improve contextual relevance, cultural alignment and public legitimacy.

Finally, the applicability of the framework could be expanded by including additional spatial indicators, such as digital literacy, environmental vulnerability and urban resilience metrics. Testing the approach in different geopolitical regions beyond the Mediterranean would also provide valuable insights into its generalisability and transferability to diverse governance landscapes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study were generated in an experimental sandbox environment and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme under grant agreement No. 101061694 (TRUST). The APC was funded by University of Macerata.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, D.K. Exploring the symbiotic relationship between digital transformation, infrastructure, service delivery, and governance for smart sustainable cities. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 806–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djatmiko, G.H.; Sinaga, O.; Pawirosumarto, S. Digital transformation and social inclusion in public services: A qualitative analysis of e-government adoption for marginalized communities in sustainable governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, A.; Sharma, C. Digital transformation in local governance: Opportunities, challenges and strategies. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Econ. Agric. Res. Technol. (IJSET) 2023, 3, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mokdad, A. Inclusive and Intelligent Governance: Enabling Sustainability Through Policy and Technology. In Social System Reforms to Achieve Global Sustainability; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 173–238. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, H.; Nagai, M.; Shibasaki, R. Reviews of geospatial information technology and collaborative data delivery for disaster risk management. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 1936–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, S. The geospatial crowd: Emerging trends and challenges in crowdsourced spatial analytics. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.P.; Kundu, S.S.; Sarma, K.K. Geospatial Technology for Effective Disaster Risk Reduction: Best practices in capacity building. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Enhancing Data Security and Transparency: The Role of Blockchain in Decentralized Systems. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2025, 11, 593258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocadag, S.; Pohl, M.; Schreiber, A. Trusted Provenance with Blockchain Technology: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Quality, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3–5 August 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany 2025; pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, K.; Aeron, A.; Verre, F. Blockchain technology in supply chain management: Innovations, applications, and challenges. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2025, 18, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Paolanti, M. GeoAI: A review of artificial intelligence approaches for the interpretation of complex geomatics data. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. Discuss. 2022, 2022, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheider, S.; Richter, K.F. GeoAI. KI-Künstliche Intell. 2023, 37, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Huang, W.; Sun, J.; Song, S.; Mishra, D.; Liu, N.; Gao, S.; Liu, T.; Cong, G.; Hu, Y.; et al. On the opportunities and challenges of foundation models for geoai (vision paper). ACM Trans. Spat. Algorithms Syst. 2024, 10, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep learning in remote sensing: A comprehensive review and list of resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Tan, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Deep learning in environmental remote sensing: Achievements and challenges. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 241, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowicz, K.; Gao, S.; McKenzie, G.; Hu, Y.; Bhaduri, B. GeoAI: Spatially explicit artificial intelligence techniques for geographic knowledge discovery and beyond. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Miller, T.; Pickering, M.; Kara, A.K. Hybrid approaches for smart contracts in land administration: Lessons from three blockchain proofs-of-concept. Land 2021, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graglia, J.M.; Mellon, C. Blockchain and property in 2018: At the end of the beginning. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2018, 12, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Alroobaea, R.; Baqasah, A.M.; Alsafyani, M.; Bacarra, R.; Alsayaydeh, J.A.J. Secure remote sensing data with blockchain distributed ledger technology: A solution for smart cities. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 69383–69396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badidi, E.; El Harrouss, O. Integrating Edge Computing and Blockchain for Safer and More Efficient Digital Transportation Systems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 251, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, R.; Gupta, G.P.; Kumar, N.; Hassan, M.M. A privacy-preserving-based secure framework using blockchain-enabled deep-learning in cooperative intelligent transport system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 16492–16503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Mohsan, S.A.H.; Ghayyur, S.A.K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Alkahtani, H.K.; Karim, F.K.; Mostafa, S.M. Blockchain-enabled decentralized secure big data of remote sensing. Electronics 2022, 11, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Rodrigues, J.J. Federated learning-based privacy-aware location prediction model for internet of vehicular things. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 1968–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Alrashdi, I.; Hawash, H.; Sallam, K.; Hameed, I.A. Towards efficient and trustworthy pandemic diagnosis in smart cities: A blockchain-based federated learning approach. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPSG 4326; WGS 84—Geographic Coordinate System. International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP): London, UK, 2023.

- ISO 19115; Geographic Information—Metadata. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. A Unified Framework for Multi-Source Geospatial Data Integration: Methods, Challenges and Applications. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sun, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L. Harmonizing Heterogeneous Geospatial Data Sources for Large-Scale Spatial Analysis. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2784. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgeniou, T.; Pontil, M. Support vector machines: Theory and applications. In Advanced Course on Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D. DBSCAN clustering algorithm based on density. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Forum on Electrical Engineering and Automation (IFEEA), Hefei, China, 25–27 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, I.; Koperski, K.; Lindenbaum, D.; Pang, G.; Huang, J.; Basu, S.; Hughes, F.; Tuia, D.; Raskar, R. Deepglobe 2018: A challenge to parse the earth through satellite images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten, A.; Lindenbaum, D.; Bacastow, T.M. Spacenet: A remote sensing dataset and challenge series. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01232. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).