Abstract

Geolocating Twitter users from social media data holds significant value in applications such as targeted advertising, disaster response, and social network analysis. However, existing social network-based geolocation methods tend to focus primarily on mention relations while neglecting other critical interactions like retweet relationships. Moreover, effectively integrating diverse social features remains a key challenge, which limits the overall performance of geolocation models. To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel Twitter user geolocation method based on multi-graph feature fusion with a gating mechanism, termed MGFGCN, which fully leverages heterogeneous social network information. Specifically, MGFGCN first constructs separate mention and retweet graphs to capture multi-dimensional user relationships. It then incorporates the Information Gain Ratio (IGR) to select discriminative keywords and generates Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) features, thereby enhancing the semantic representation of user nodes. Furthermore, to exploit complementary information across different graph structures, we propose a Structure-aware Gated Fusion Mechanism (SGFM) that dynamically captures differences and interactions between nodes from each graph, enabling the effective fusion of node representations into a unified representation for subsequent location inference. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing state-of-the-art baselines in the Twitter user geolocation task across two public datasets.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of mobile communication and Internet technologies, Twitter has emerged as a major social platform. Users use it to record and share aspects of their daily lives. Tweets often contain explicit or implicit geographic information. This information has great value in various research and application domains, such as user behavior analysis [1,2], event geolocation [3,4], and targeted advertising [5]. However, according to a study by Luo et al. [6], only about 1% of tweets are geotagged, making geolocation based on explicit data extremely difficult. Furthermore, social media data are typically unstructured, colloquial, and noisy, further increasing the complexity of geolocation inference. Consequently, accurately inferring user locations from tweet content and social relationships has become a key research focus.

User behaviors on social networks, including the content they post and their interactions with others, offer valuable clues for geolocation. Existing geolocation methods can generally be divided into three categories. The first category, text-based methods [7,8], infer user locations by analyzing location-related words and linguistic patterns in tweets. However, these methods overlook the influence of social relationships, resulting in limited precision. The second category, social network-based methods [9,10], rely on the structure of social networks to make inferences but perform poorly for users with few or no social connections. The third category, multi-source-based methods [11,12], combine text with social relationships, effectively overcoming the limitations of the first two methods and showing better performance and adaptability in user geolocation tasks.

Despite the progress made by existing studies, several challenges remain: (1) Limited interaction modeling in graph construction. Most existing studies primarily rely on mention relationships between users while overlooking retweet interactions. As a result, the constructed social graphs fail to fully capture the diversity of user interactions, which in turn limits the capability of user location inference. (2) Suboptimal textual feature representation. Existing TF-IDF-based textual representations tend to introduce a large number of irrelevant or redundant terms, thereby reducing the discriminative power of features and compromising the model’s generalization capability. (3) Ineffective multi-graph feature fusion. Existing fusion strategies rely on simplistic operations like weighted averaging or concatenation, lacking adaptive mechanisms to dynamically balance feature contributions. This leads to either insufficient utilization of complementary information or over-reliance on dominant features, ultimately degrading localization performance.

To overcome the above challenges, we propose a novel Twitter user geolocation method based on gated multi-graph feature fusion. Specifically, we construct mention and retweet graphs to represent different types of social relationships. This aims to capture complementary information embedded in diverse interaction patterns and enhance the expressiveness of social features. Then we combine IGR and TF-IDF techniques to extract geo-discriminative keywords from user tweets. This results in sparse, yet information-rich semantic representations that improve the model’s ability to characterize user geolocation attributes. To effectively integrate the two social graphs, we propose the Structure-aware Gated Fusion Mechanism that jointly considers the original feature matrices of node representations, different feature matrices, and their interaction matrices. This mechanism learns content-aware gating weights to adaptively adjust the contributions of each graph, thereby enhancing the expressiveness and structural discriminability of the fused representation. Finally, the fused node representations are input into a classification module to perform user geolocation inference. Compared with existing methods that rely solely on structured data or a single type of social graph, MGFGCN uniquely integrates multiple types of social relationships with geo-discriminative textual features. By combining these heterogeneous inputs through a structure-aware gated fusion mechanism, MGFGCN captures complex spatial correlations that structured-data-only models cannot represent, substantially improving the accuracy and robustness of user geolocation inference.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We construct separate mention and retweet graphs to take advantage of the complementary information encoded in different social interaction patterns. Modeling multiple social relationships significantly improves the expressiveness of social characteristics and enhances the accuracy of geolocation.

- We propose a node semantic representation method that combines IGR and TF-IDF to extract location-discriminative keywords from tweets, resulting in a sparse but informative feature matrix that better represents user geographic attributes.

- We propose the Structure-aware Gated Fusion Mechanism that integrates raw features, different terms, and interaction terms to generate content-aware gating weights, allowing adaptive adjustment of each graph’s contribution during feature fusion and producing more expressive and discriminative representations.

- We propose a Twitter user geolocation method based on multi-graph feature fusion with a gating mechanism. Extensive experiments on two real-world Twitter datasets demonstrate that the proposed MGFGCN model consistently outperforms existing baselines in geolocation accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on user geolocation. Section 3 presents the definition of the problem and key notation. Section 4 introduces the proposed methodology in detail. Section 5 describes the datasets and reports the experimental results. Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

2. Related Work

According to the data sources utilized for geolocating Twitter users, existing geolocation methods can be classified into three categories: text-based methods, social network-based methods, and multi-source-based methods.

2.1. Text-Based Methods

Tweets refer to textual content posted by users on the Twitter social platform, which may include location-related words or phrases. Additionally, language usage varies across regions, meaning that the vocabulary in tweets may implicitly contain geographical clues. Common text-based user location inference methods can generally be categorized into gazetteer-based methods, machine learning-based methods, and deep learning-based methods.

Gazetteer-based methods [13] attempt to locate users by detecting place names within tweets or user profile metadata. Although simple, these methods often suffer from low accuracy due to the informal and noisy nature of tweet content. In contrast, machine learning-based methods utilize a range of algorithms to analyze text features for location inference. They offer greater flexibility than gazetteer-based methods and encompass various models, including probabilistic language model-based methods, topic model-based methods, and supervised machine learning-based methods [14]. Specifically, probabilistic language model-based methods construct spatial language profiles using geotagged data and estimate user locations by comparing likelihoods between regions [15]. However, their dependence on annotated data and vulnerability to noisy input limit their effectiveness. Topic model-based methods assume that tweets from different regions exhibit distinct thematic structures, which helps address text sparsity issues [16]. Supervised machine learning-based methods leverage bag-of-words features or neural networks to infer user locations from tweet content. To further improve geolocation accuracy, deep learning-based methods [17] have been introduced. These models exploit the representational power of neural networks to automatically extract spatially informative features from tweets. However, their high model complexity often results in longer training times and performance tends to degrade when processing noisy or informal language, ultimately constraining localization precision.

2.2. Social Network-Based Methods

Social network-based user geolocation methods rely primarily on the principle of geographic homophily, which posits that users in spatial proximity are more likely to establish social connections and interact [18]. These methods can be broadly categorized into community detection-based methods, label propagation-based methods, and graph embedding-based methods.

Community detection-based methods identify groups or communities within social networks to reveal latent geographical associations among users. For example, Pang et al. [19] partitioned user networks into distinct communities and used community characteristics (e.g., member size, visited locations) to train location inference models, thus improving the robustness and precision of the inference. Zhou et al. [20] developed a Hierarchical Graph Neural Network (HGNN) that integrates user geographic information with regional clustering effects. This approach strengthens geographical signals through hierarchical graph learning and employs relational mechanisms to connect individual users with communities, improving the accuracy of the inference of unlabeled nodes. Label propagation-based methods utilize the geographic labels of known users and propagate these labels across the social graph to infer the locations of unlabeled users. For example, Jurgens et al. [18] constructed a network of mentions based on user interactions and applied label propagation to efficiently expand location coverage. Rahimi et al. [21] proposed a hybrid method that transforms one-way mentions into undirected social edges, while labeled users rely on label propagation, isolated users are handled using a text-based fallback inference model to improve both coverage and accuracy. Graph embedding-based methods construct social graphs and employ embedding techniques to project users into a shared low-dimensional matrix space, capturing their structural and semantic relationships. These user representations are then used to train geolocation models. For example, Wang et al. [10] integrated social relationships, check-in behavior, and user-location heterogeneous graphs to enhance the quality of user embeddings for more accurate location inference.

Although social network-based methods often achieve higher accuracy than text-based methods, they still face challenges such as handling isolated users and insufficient modeling of social features.

2.3. Multi-Source-Based Methods

Traditional geolocation methods often rely on a single data source, such as user-generated text or social networks. This reliance can limit both the accuracy and the comprehensiveness of location inference [22]. To address this limitation, researchers have proposed multi-source-based methods that integrate user-generated content, social relationships, and other contextual data such as timestamps and geotags to infer user locations more holistically.

In recent years, significant efforts have been made to improve the effectiveness of multi-source information fusion. For example, Zheng et al. [12] proposed the Hybrid Attention User Geolocation (HUG) framework, which employs a hybrid attention mechanism to dynamically assess the relative importance of textual and social information for different users. Tian et al. [23] constructed a heterogeneous graph to integrate multiple data sources to learn user representation, thus improving the accuracy of the geolocation. Some studies have focused specifically on inferring the locations of isolated users in social networks. Gao et al. [24] introduced the Social Relationship Graph Convolutional Neural Network (SRGCN) model, which builds a social graph for isolated users based on topic similarity in textual content and improves location inference through social enhancement. Beyond textual and relational data, user profile information has also been utilized for geolocation. Huang et al. [25] proposed a method that incorporates seven types of characteristics, including tweets, self-descriptions, profile locations, usernames, language settings, time zones, and mention networks, which significantly improved geolocation performance.

In summary, multi-source-based methods overcome the limitations of single-source methods. They offer substantial improvements in the accuracy and robustness of user location inference.

3. Problem Formulation

To enhance the interpretability of our approach, we begin by redefining the user geolocation inference task and outlining the core notations used throughout this paper.

We conceptualize user geolocation as a supervised classification task, where the objective is to assign each user to a geographic region based on both their tweet content and social interaction patterns, such as mentions and retweets. To obtain the region labels, we first apply k-means clustering on users’ actual geographic coordinates, treating the resulting centroids as representative locations. Let L denote the set of all cluster centroids and let represent the centroid assigned to user u. Let U denote the set of all users. Each user is represented as a quadruple, defined as follows:

where denotes the text features extracted from the user’s tweets, represents the user’s mention relations in the social network, represents the user’s retweet relations, and denotes the ground-truth geographic location of user u.

The goal of our model is to minimize the geographic distance between the inferred and true locations of each user, defined as follows:

where denotes a function that computes the geographic distance (e.g., the Haversine distance) between the inferred and true locations. In this formulation, the geolocation task is effectively transformed into identifying the most plausible region from a set of predefined clusters. All relevant notations used in the model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key notations and explanations.

4. Proposed Method

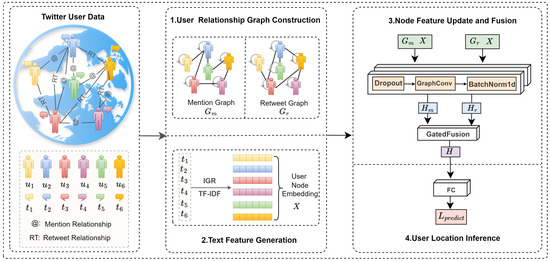

This paper proposes a multi-graph feature fusion with a gating mechanism for Twitter user geolocation. The overall framework consists of four main components: user relationship graph construction, text feature generation, node feature update and fusion, and user location inference. The general architecture of the proposed model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The architecture of the proposed method.

First, to capture diverse types of structural interactions among users, we construct two separate social graphs, i.e., the mention graph and the retweet graph, each reflecting a distinct type of social relationship. In the text feature generation stage, we apply IGR to select geo-discriminative keywords from user tweets and construct sparse yet semantically rich TF-IDF representations. Next, we employ two-layer Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) on each of the two graphs to learn high-level node embeddings that encode both local and global structural semantics. To effectively integrate information from heterogeneous graph structures, we propose the SGFM that adaptively adjusts the contribution of each graph’s features, generating a more unified and expressive user representation. Finally, the fused node feature matrix is passed through a linear layer to generate the final inference of each user’s geographic location. The code is available at https://github.com/Linfei105 (commit a6a7227, accessed on 15 October 2025).

4.1. User Relationship Graph Construction

We construct two types of social graphs based on user interactions extracted from tweets; that is, the mention graph and the retweet graph . Here, V denotes the set of all user nodes, represents the set of mention edges, and represents the set of retweet edges. If one mentions another or both mention the third user, an undirected edge is added to , and the same applies to the retweet graph. To enhance the expressive power of the graph structure, we add self-loops for all nodes in both graphs. The mention and retweet relations are extracted using regular expressions: @(\w+)\s for mentions and RT\s+@(\w+) for retweets.

Furthermore, if a user is mentioned or retweeted by more than other users, that user is considered a celebrity. Since such users typically contribute little to geolocation tasks, we remove all celebrity nodes from the graphs to improve the model’s effectiveness. To further enhance the social network structure, we consider co-mention connections, which capture shared mentions between users, as well as 2-hop neighbor connections for indirect social links. Given that some users may have very few direct (1-hop) neighbors or may even be isolated, incorporating 2-hop connections improves the connectivity of the network, allowing information to propagate more effectively across a broader set of users. To verify the impact of co-mentions, 2-hop, and settings on geolocation performance, we conducted a dedicated ablation study, with detailed results presented in Section 5.7.

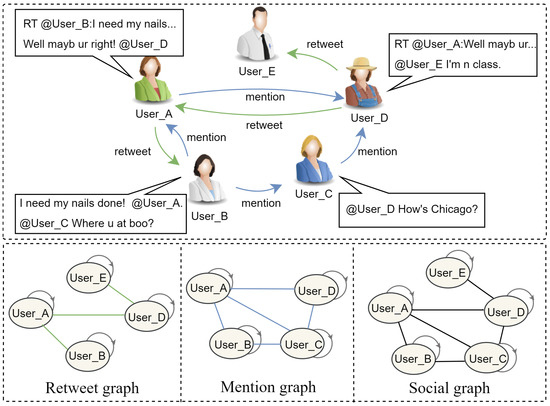

In addition to the two heterogeneous graphs, we construct a merged social relationship graph by combining the mention graph and the retweet graph into a single unified graph without distinguishing edge types. Formally, this social relationship graph is defined as , where the node set V and the edge set represent the union of those from and . This unified graph is used in subsequent ablation studies to evaluate the differences in effectiveness between separately modeling heterogeneous relations and directly merging them. Figure 2 provides an illustrative example.

Figure 2.

An illustrative example of social relationship graph construction. Top panel: Users (User_A–User_E) with sample tweets, mentions (blue arrows), and retweets (green arrows). Here, “RT @User” indicates a retweet, and “@User” indicates a mention. Bottom panels: (left) retweet graph; (middle) mention graph; (right) social graph combining both. A mention relationship exists between User_A and User_C, as both mention User_D.

4.2. Text Feature Generation

In this study, to enhance the discriminative power of text features for geolocation inference, we propose a feature selection and representation method that integrates IGR with TF-IDF. Compared with feature selection methods such as Chi-square [26], Mutual Information [27], or Variance Threshold [28], IGR not only measures the distributional differences of terms across categories but also emphasizes their contribution to the uncertainty of category information, i.e., the ratio of information gain to class entropy. This property enables IGR to more effectively identify terms that are most discriminative for geographic labels, particularly in scenarios with class imbalance or multiple categories, while reducing redundant and noisy features. Building on this, weighting the selected terms with TF-IDF preserves the label-driven discriminative capability while accounting for the global statistical importance of terms, thereby reflecting both their relevance and distinctiveness. The method combines the IGR-based Keyword Selection Mechanism (IKSM) with a TF-IDF-based term weighting strategy, enabling both label-informed feature filtering and corpus-aware term weighting, thereby enhancing the geographic sensitivity of text representations.

Specifically, in the training set, we treat each training user’s aggregated tweets as a single document. Before feature selection using IGR, the documents first undergo systematic preprocessing. This preprocessing procedure encompasses removing special characters and emojis, deleting URL links, eliminating stop words, and reducing the vocabulary to its base forms. On this basis, for a given term , where represents the candidate keyword vocabulary constructed from training user documents , its presence or absence is denoted as a binary feature variable . Y denotes the vector of geographic labels corresponding to training users. The IGR is defined by Equation (3):

where denotes the entropy of the label distribution, measuring the uncertainty of Y, and is defined by Equation (4):

where denotes the number of distinct geographic label categories. represents the probability that the a-th label category occurs in the label vector Y. The conditional entropy measures the uncertainty of Y given the value of the characteristic and is defined by Equation (5):

where each corresponds to a binary feature variable , whose value is 1 if the term appears in a user document and 0 otherwise. The label distributions for both cases are used to compute the conditional entropy. All candidate terms are then ranked in descending order based on their IGR scores, and the top k terms with the highest scores are selected to form the final keyword vocabulary , which is used in the subsequent generation of the TF-IDF matrix.

TF-IDF combines the frequency of the term (TF) and the inverse frequency of the document (IDF) to measure the importance of a term within a document relative to the entire corpus T. It is defined by Equation (6):

where denotes the frequency of term in user document , and is the total number of terms in . denotes the total number of user documents and denotes the number of documents that contain the term . Based on this TF-IDF formulation, we generate a text feature representation for each user. These vectors are organized into a text feature matrix , where N is the total number of users and k is the dimensionality of the feature vector for each user. X serves as the initial representation of the features of the nodes in the graph of social relations and is used as input for subsequent convolution operations. The text feature generation algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Text Feature Generation Algorithm |

|

4.3. Node Feature Update and Fusion

The significant advantages of GCNs in processing graph-structured data are their strong capabilities in feature aggregation and structural information modeling. This study incorporates a multi-layer GCN into the model to enhance both information propagation and contextual awareness among nodes. The multi-layer propagation mechanism enables the model to effectively capture semantic information from distant neighbors. Taking the mention graph as an example, the node feature update process at the h-th GCN layer is defined by Equation (7):

where , with being the symmetrically normalized adjacency matrix of , and is the degree matrix of . is the trainable weight matrix of the h-th layer (where K denotes the output dimension). The activation function is PReLU, which introduces a learnable negative slope to improve nonlinear expressiveness. When , is the initial input node feature matrix.

Regarding the depth of GCN layers, Li et al. [29] showed that stacking too many layers can lead to over-smoothing, where node representations become indistinguishable. To balance expressiveness and distinguishability, we employ a two-layer GCN structure. The final node representation from is computed using Equation (8).

Similarly, using the same input X, the representation of node can be obtained from the retweet graph . and are the outputs of the second-layer GCN, in the form of logits (not probabilities) without applying Softmax. They serve as inputs to the gating mechanism for further integration of information from different social relation graphs, while Softmax is applied only in the final classifier to produce a probability distribution.

Existing multi-graph fusion methods often adopt static strategies, which lack flexibility in capturing the semantic heterogeneity of nodes across different graphs. Although some studies have introduced gating mechanisms to enhance fusion performance, these methods often rely on simple linear weighting. As a result, they fail to effectively capture the semantic divergence and interactions between graphs, thereby limiting their representational power. To address this, we propose the SGFM which dynamically generates fusion weights by incorporating features of semantic difference awareness and interaction awareness. This enables fine-grained modeling of inter-graph semantic relations and improves structural adaptability and robustness. Specifically, the mechanism considers node embeddings from both graphs and constructs difference and interaction features to guide the gating function in perceiving complementary and redundant information. The gating function is defined by Equations (9) and (10):

where and are embeddings of nodes from the mention and retweet graphs, respectively. denotes the absolute difference in elemental terms. is the product in terms of elements. Concatenation Z serves to capture semantic divergence and potential complementarity between node representations under different structural views. and are learnable weight matrices. denotes the sigmoid function to ensure that the gating values are within . G has the same shape as and , which means that the gating is carried out independently for each node and each feature channel, and the multiplication by element with and follows the broadcast rules to align the dimensions. Based on the learned gating weights, the final fused node representation is computed by Equation (11):

This fusion mechanism enables fine-grained modeling of node-level information from both graphs. It adaptively learns differentiated fusion strategies based on the semantic features of each node, thereby improving the robustness and expressiveness of multi-relational graph modeling. For clarity, a tiny tensor shape sketch of is provided in Table A1 of Appendix A. Moreover, to assess the contribution of each component in Z to geolocation prediction within the SGFM, we conducted an ablation study, with detailed results presented in Section 5.6.4.

4.4. User Location Inference

After fusing the node representations from the mention and retweet graphs using the SGFM, the model obtains more discriminative user embeddings. To perform geolocation classification, the fused representation is passed through a fully connected layer, which maps it to a probability distribution over location categories. Inference is computed by Equation (12):

where and are trainable classification weights and bias terms, respectively. denotes the inferred probability distribution in the geographic classes S for each of the users N. To optimize model performance and ensure that the inferences approximate the true labels as closely as possible, we adopt the cross-entropy loss function for supervised training. The loss is defined by Equation (13):

where is the one-hot encoding of the user i’ true label for class c, and is the inferred probability corresponding. The inferred label corresponding to the maximum probability indicates the geolocation class of each user.

5. Experiment

This section presents the evaluation results of MGFGCN from multiple perspectives, structured around the following research questions:

- (RQ1): How does the proposed method perform compared to the baseline methods?

- (RQ2): What is the impact of the number of IGR-selected keywords on geolocation performance?

- (RQ3): How does the embedding dimension affect the geolocation accuracy?

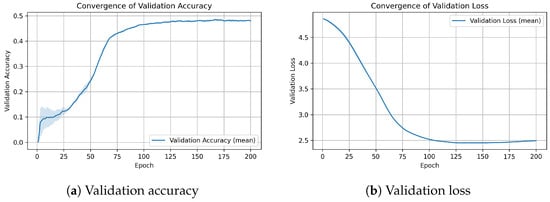

- (RQ4): What are the convergence dynamics of the model during training, and how do validation accuracy and loss reflect its stability and generalization capability?

- (RQ5): What is the effect of different activation functions on the performance of geolocation inference?

- (RQ6): What is the influence of different types of social relationships on geolocation performance?

- (RQ7): How does each component of the MGFGCN architecture contribute to the overall performance?

- (RQ8): What is the contribution of each component of Z within the SGFM to geolocation prediction?

- (RQ9): How do co-mention edges and 2-hop neighbor connections affect geolocation performance, and how robust are the results across different settings?

- (RQ10): In the geolocation prediction task, how does our proposed SGFM compare with other gated fusion mechanisms (BasicGatedFusion and AttnGatedFusion) in terms of performance and computational complexity, and how are its advantages in multi-feature fusion and geographic semantic modeling manifested?

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.1.1. Dataset

To evaluate the performance of our method, we conducted experiments on two real Twitter datasets that are widely used for assessing user geolocation methods: GeoText [30] and Twitter-US [31].

- GeoText is a small dataset that contains 377,616 messages from 9475 users in 48 states in the United States. The documents in this dataset consist of concatenated tweets from individual users (in this paper, “concatenated tweets” refers to the direct combination of original tweets, without using any AI tools or generative models; all data are authentic user posts collected via the Twitter API), with the geographical coordinates of each tweet serving as the location of the user’s ground truth. The dataset is divided into a training set, a validation set, and a testing set, containing 5685, 1895, and 1895 users, respectively.

- Twitter-US is a larger dataset that includes 449,000 users from the United States. Using the publicly available Twitter Spritzer feed and the global search API, a total of 390 million tweets were sent. Following the method of [32], to make comparisons with GeoText, we discarded tweets located outside of North America. Following [30], 10,000 users were reserved for validation and 10,000 users for testing. Table 2 summarizes the number of tweets, users, mention interactions and retweet interactions (with duplicates removed), the sizes of the training, validation, and test sets, as well as the number of cities, providing an intuitive overview of the characteristics of the dataset.

Table 2. Specific information about the dataset used for the experiment.

Table 2. Specific information about the dataset used for the experiment.

5.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

This paper employs three commonly used evaluation metrics to assess the performance of the proposed user geolocation method. The Haversine formula is used to calculate the distance error between the inferred coordinates and the actual coordinates , where is the set of users in the test set. u represents one of the users in , and is the number of users in .

- Acc@161: In the field of social media user geolocation, the 161 mile threshold is widely adopted to ensure fair and consistent comparisons across different methods. It is the percentage of users whose inferred locations fall within a range of 161 miles from their actual locations, relative to the total number of users in the test set. The definition is shown in Equation (14):

- Mean: The mean error is the average of the error distances for all users, as shown in Equation (15):

- Median: The median error is calculated by first sorting the error distances of all users in the test set in ascending order and then selecting the median value from the sorted list as the median error. The definition is shown in Equation (16):

Overall, the proposed method performs better when Acc@161 is larger while the mean and median values are smaller.

5.1.3. Baselines

We compare the proposed model and method with the following baseline methods:

Text-based Methods:

- HierLP [33]: It is a text-based geolocation model that employs a grid-based location representation and performs hierarchical classification using logistic regression (LR).

- MLP4Geo [17]: It is a model that improves inference performance by incorporating dialectal terms and uses a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) for location inference.

- DocSim [34]: It is a document similarity-based method that uses KL divergence to compare topic distributions for location inference.

- LocWords [35]: It is a model that identifies location-indicative words (LIWs) through various strategies to perform geolocation.

- MixNet [36]: It is a geolocation approach that embeds coordinates using a mixture density network and classifies locations based on an MLP.

Social Network-based Methods:

- MADCEL-W [32]: It is a method that integrates user text features as separate nodes into the social network and applies logistic regression for inference.

- GCN-LP [37]: It is a model that uses the adjacency matrix of the user social network as input to a highway GCN for classification.

Multi-source-based Methods:

- GCN [37]: It is a model that combines the bag-of-words (BoW) features of tweets with the information of the social network using the highway GCN.

- SGC4Geo [38]: It is a method that applies a simplified graph convolution model (SGC) to fuse Doc2Vec representations of tweets with the social network structure.

- MetaGeo [39]: It is a meta-learning-based framework that aggregates a large number of small tasks for user geolocation.

- HGNN-TF [20]: It is a hierarchical GNN model that incorporates TF-IDF features from tweets to infer user locations.

- SRGCN [24]: It is a hybrid learning model that integrates text features with social structure. It constructs a social relationship graph based on topic similarity to enhance the representation of isolated users, thereby improving the accuracy of user geolocation inference.

5.1.4. Parameter Setting

During text feature generation, the number of candidate keywords was set to k = 5120 for the GeoText dataset and k = 20,000 for the Twitter-US dataset. The dimensionality of the node embeddings in the social relationship graph was set to 200. In the graph construction process, the threshold for removing celebrity nodes was set to 5 and 15 for GeoText and Twitter-US, respectively. These values were determined based on experiments with thresholds of 2, 5, 15, 30, and 60, by selecting the smallest value that significantly reduced the graph size while maintaining stable model performance. All experiments were conducted on a system equipped with an NVIDIA L20 GPU (48 GB memory), a 20-core Intel Xeon Platinum 8457C CPU, and 100 GB of RAM. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a dropout rate of 0.8, and for 200 epochs.

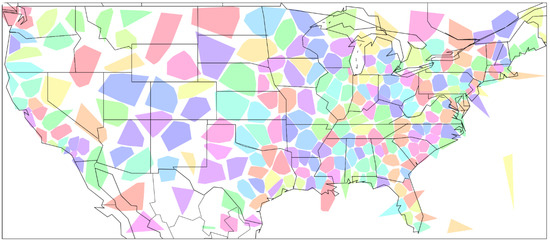

Owing to its high computational efficiency, scalability to large-scale social media data, and the ability to explicitly control the number of clusters for downstream tasks, we employed the k-means algorithm to perform geographical clustering of users. As shown in Table 2, to ensure comparability with prior studies, the number of clusters was set to 129 and 256 for GeoText and Twitter-US, respectively. We further used the minimum convex polygon algorithm to calculate and visualize the boundaries of each cluster, thereby illustrating their geographical distributions. The clustering results of user coordinates in the Twitter-US training set are shown in Figure 3. The k-means clusters exhibit clear regional concentration and correspond closely to underlying geographic boundaries, demonstrating strong spatial coherence while capturing the intrinsic spatial continuity of users’ location data.

Figure 3.

Results of user coordinate partitioning for the Twitter-US training set using k-means. Different colors correspond to distinct user cluster regions, and the boundary of each polygon reflects the geographical distribution range of users within that region.

5.2. Method Performance (RQ1)

Table 3 presents the overall performance of all methods using two datasets. It can be seen from the table that (1) MGFGCN consistently outperforms all baseline methods across various evaluation metrics, demonstrating its strong effectiveness in addressing the user geolocation task. Specifically, on the GeoText dataset, it achieves improvements of 7 km in mean error, 11 km in median error, and 1.2% in Acc@161 over the best-performing baseline. The gains are even more pronounced on the Twitter-US dataset, with reductions of 22 km and 9 km in mean and median error, respectively, and a 2.7% improvement in Acc@161. (2) The results reveal that social network-based methods significantly outperform text-based methods. For example, on the GeoText dataset, the Acc@161 of GCN-LP exceeds that of HierLR by 17%. (3) Experimental results indicate that multi-source-based geolocation methods outperform those relying solely on textual or social information.

Table 3.

Geolocation results on the Twitter datasets. (↑ indicates higher values are better; ↓ indicates lower values are better; – indicates no results reported for the dataset. Best and second-best results are bolded and underlined, respectively).

Building on the above findings, we further analyzed the principles behind these methods and attributed their outstanding performance to the following factors:

- The superior performance of MGFGCN primarily stems from its ability to effectively integrate multiple types of social relationships and textual features while capturing both local and global spatial dependencies. By jointly modeling mention and retweet interactions and emphasizing discriminative textual cues, the model produces more informative and robust user representations, thereby achieving state-of-the-art performance in geolocation prediction.

- The notable advantage of social network-based methods arises from the inherent characteristics of social networks, in which people tend to interact with geographically proximate individuals, and these social ties often correspond to real-world spatial closeness. In contrast, text-based methods are considerably constrained by the subjective and context-dependent nature of language, which leads to ambiguous associations between words and geographic locations. Therefore, social features play an important role in geolocation tasks.

- The strength of multi-source methods lies in their ability to jointly leverage features from multiple modalities, such as text and social networks, to achieve more comprehensive and effective representation learning. Multi-source data provide complementary information from different perspectives, helping to mitigate ambiguity and noise present in individual modalities. Consequently, this leads to improved geolocation accuracy and robustness. These findings underscore the importance of multi-view feature learning for user location inference.

Although MGFGCN demonstrates strong performance in geolocation prediction, it still has certain limitations, such as the need to consider computational efficiency and resource consumption when handling very large-scale networks. In addition, existing social network-based methods have limited accuracy for isolated users or users with cross-region interactions, while multi-source methods may suffer from reduced performance when data are incomplete or modality information is imbalanced. Therefore, practical applications still require careful consideration of computational cost, data dependency, and the robustness of the methods.

Statistical significance test: On the GeoText dataset, we conducted experiments using 10 random seeds (2021–2030) and evaluated the statistical significance of performance differences via independent-sample t-tests. The results indicate that MGFGCN significantly outperforms the strongest baseline across multiple metrics: It achieves an average accuracy of 62.9%, compared to 62.0% for MetaGeo (with fluctuations of at most ±0.3%), and mean and median errors of 520 km and 29 km, respectively, which are significantly lower than HGNN-TF’s 530 km and 40 km. The t-tests yielded p-values < 0.005, confirming that the improvements of the proposed method are not due to random variation but represent stable and statistically significant gains.

Practical significance of performance improvements: In the task of geolocation prediction, the proposed MGFGCN model demonstrates notable practical value on two public datasets. On the GeoText dataset, although Acc@161 improves by only 1.2 percentage points, the mean and median errors decrease by 7 km and 11 km, respectively. This improvement helps enhance the model’s ability to distinguish sub-regions within a city, thereby improving the accuracy of localized service recommendations. On the larger Twitter-US dataset, Acc@161 increases by 2.7 percentage points, while the mean and median errors decrease by 22 km and 9 km, respectively, which partially mitigates cross-region localization errors.

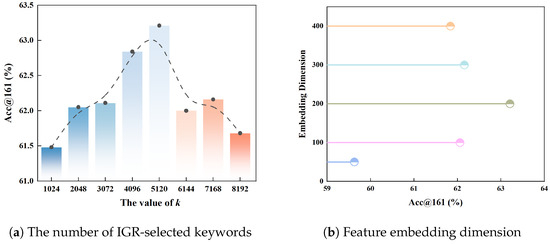

5.3. Effect of the Number of IGR-Selected Keywords (RQ2)

To investigate the effect of the number of IGR-selected keywords k on the performance of the method, we conducted experiments on the GeoText dataset, comparing the Acc@161 metric with different values of k. The results are shown in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

The impact of the number of IGR-selected keywords and the feature embedding dimension on the GeoText dataset.

We observe that as the value of k increases, the performance of the model initially improves, reaching a peak at k = 5120, and then starts to decline. This trend indicates that retaining too few keywords during feature selection may fail to capture sufficient semantic information from the text, resulting in suboptimal performance. As more keywords are retained, the model acquires richer and more discriminative text features, thus improving the classification accuracy. However, when the value of k becomes too large, many irrelevant or low-information-gain words are introduced into the feature space. These “noisy” features not only fail to provide additional discriminative power but also interfere with the learning process, thus affecting performance.

In addition, larger k values significantly increase the dimensionality of the TF-IDF feature matrices, leading to higher computational and memory overhead. Therefore, appropriately controlling the number of selected keywords not only improves model accuracy but also improves resource efficiency. We conducted the same experiment on the Twitter-US dataset and observed that the best performance was achieved when k = 20,000. Therefore, for the GeoText and Twitter-US datasets, we set the k values to 5120 and 20,000, respectively.

5.4. Effect of the Feature Embedding Dimensions (RQ3)

To further explore the impact of the feature embedding dimension on geolocation performance, we performed a sensitivity analysis on the GeoText dataset, with results presented in Figure 4b.

The results show a clear upward trend in Acc@161 as the embedding dimension increases, especially when the dimension is below 200. This suggests that low-dimensional embeddings may lack sufficient expressive capacity to capture complex associations between text and geographic information. As the dimension increases, the model gains stronger representation ability, leading to better localization accuracy. However, when the embedding dimension exceeds 200, performance begins to decline. This may be due to the introduction of redundant or non-informative features in high-dimensional spaces, which act as noise during training and negatively affect the generalization capacity of the model. Moreover, larger embedding sizes also lead to higher computational and storage costs.

We observed consistent results on the Twitter-US dataset, with the best performance achieved when the embedding dimension is set to 200. Therefore, considering both performance and computational efficiency, we set the embedding dimension to 200 as the default for all experiments on both datasets.

5.5. Model Convergence Analysis (RQ4)

To evaluate the convergence characteristics of the model, three independent training runs were conducted using the same data splits and hyperparameter settings, as shown in Figure 5. During each run, the validation loss and accuracy were recorded over successive epochs. Training was carried out for 200 epochs using the Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001) in combination with Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) to improve efficiency and numerical stability. The results from the three runs were averaged, and the standard deviation was calculated to obtain a smoothed convergence trend. Validation loss and accuracy curves were then plotted to analyze the model’s stability and generalization ability.

Figure 5.

Convergence of the model on the validation set of the GeoText dataset. (a) Validation accuracy over 200 training epochs, showing the gradual improvement and stabilization of model performance. (b) Validation loss over 200 training epochs, indicating steady decrease and convergence. The shaded area in (a) represents the standard deviation across multiple runs.

The changes in validation metrics clearly illustrate the model’s convergence process. In the early stages of training, the validation accuracy rapidly increased from approximately 0.1 to 0.4, while the validation loss dropped significantly, indicating that the model was effectively learning key features. As training progressed to around epoch 100, accuracy began to stabilize, ultimately fluctuating around 0.48, suggesting that the model had largely converged. Correspondingly, the validation loss declined more gradually in the later stages and remained at a low level without noticeable increases, indicating the absence of substantial overfitting. Overall, the model exhibited good convergence over 200 epochs: validation accuracy gradually stabilized, and the loss function remained low, demonstrating an efficient training process and a certain degree of generalization capability.

5.6. Ablation Experiments

5.6.1. Effect of Different Activation Functions (RQ5)

We systematically evaluated the impact of different activation functions (PReLU, ReLU, ELU, and GELU) on the task of user geolocation inference (Table 4). The results indicate that while all methods achieve reasonable predictive performance, notable differences emerge in capturing the complex nonlinear relationships inherent in user text and social interactions. It can be seen from the table that PReLU exhibits the best overall performance, slightly outperforming other activation functions across Acc@161, mean error, and median error metrics. Replacing PReLU with ELU (w/ELU) or ReLU (w/ReLU) leads to a modest performance drop, with Acc@161 decreasing by approximately 1–1.5 percentage points and slight increases in both mean and median errors. Using GELU (w/GELU) results in a more pronounced decline, with Acc@161 reduced by around 3% and further increases in mean and median errors.

Table 4.

Ablation results of MGFGCN components on the GeoText dataset.

The above results indicate that the learnable negative slope of PReLU enables the model to adaptively adjust activation responses between nodes, thereby more effectively capturing asymmetries and local feature variations within the heterogeneous social graph. Specifically, PReLU is more sensitive to weak signals and peripheral nodes, allowing the model to exploit sparse or subtle information, whereas ReLU completely zeroes out negative values and thus has limited responsiveness. Compared to GELU, whose smooth nature may cause excessive homogenization of node representations, PReLU preserves local differences, making it easier for the model to distinguish between different geographic regions. Moreover, the learnable negative slope allows the model to flexibly fit complex, multi-level nonlinear dependencies, a capability that fixed-form or overly smooth activation functions lack. These observations suggest that the suitability of activation functions in heterogeneous graph modeling and geolocation inference depends on node characteristics, graph structure, and task objectives. Overall, the adaptive nonlinearity of PReLU not only enhances numerical performance but also achieves a better balance between local feature expression and global information integration, providing more targeted guidance for activation function selection beyond conventional experience or smoothness considerations.

5.6.2. Contribution Analysis of Different Types of Social Relationships Graph (RQ6)

To evaluate the contribution of different types of social relationships to geolocation inference, we performed ablation studies on the GeoText dataset. Specifically, we removed the mention graph and the retweet graph separately and introduced a simple merged relationship graph (MRG) as a comparison. In the MRG setting, the mention and retweet edges are unified into a single untyped social graph for modeling. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

- Removing mention graph (w/o MG): When the mention graph was removed, the Acc@161 decreased by 9.4%, while the mean and median localization errors increased by 206 km and 68 km, respectively. This indicates that mention relationships play a crucial role in geolocation modeling. This result can be attributed to the fact that mention edges often capture closer social interactions and localized communication contexts among users, thereby carrying strong geographical signals. These signals help the model recognize the spatial clustering characteristics of users; consequently, when mention relationships are removed, the model’s localization accuracy declines significantly.

- Removing retweet graph (w/o RTG): When the retweet graph was removed, Acc @ 161 decreased by 2.4%, and the mean and median errors increased by 55 km and 5 km, respectively. This suggests that retweet relationships exhibit weaker geographic consistency, primarily reflecting information diffusion rather than spatial proximity. However, they still provide auxiliary signals that connect users across regions. In cases where direct interactions are lacking, these edges offer useful constraints, so their contribution, though smaller than that of the mention edges, should not be ignored.

- Merged Social Graph (MSG): When the mention and retweet graphs were merged into a single untyped graph, Acc@161 decreased by 0.8%, the mean error increased by 37 km, and the median error increased by 2 km. These results indicate that simple merging dilutes the distinctive structural features of different relationship types, making it difficult for the model to distinguish the heterogeneous information carried by different edges, which reduces the efficiency of information utilization. In contrast, by modeling each relationship type separately and integrating them through SGFM, the model can better capture their complementary characteristics and fully leverage heterogeneous signals, thereby improving localization accuracy.

In summary, the contributions of different types of social relationships to geolocation inference vary significantly: the mention graph is the most critical, the retweet graph provides auxiliary information, and modeling each relationship type separately with a fusion mechanism can fully exploit the advantages of heterogeneous relationships.

5.6.3. Effectiveness of IKSM and SGFM (RQ7)

To evaluate the impact of IKSM and SGFM and to understand the contribution of each component in MGFGCN, we performed a component analysis on the GeoText dataset. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

- Impact of removing IKSM (w/o IKSM): Removing IKSM leads to an increase of 33 km in mean error, 3 km in median error, and a 0.9% decrease in Acc@161. This indicates that IKSM effectively preserves keywords highly relevant to geographic locations, thereby enhancing the discriminative power of textual features. In contrast, relying solely on the TF-IDF feature space is prone to interference from noisy terms, which limits the model’s capacity to accurately capture geolocation-related textual signals. These findings underscore the critical role of IKSM in improving textual feature quality and augmenting the model’s geographic semantic recognition ability.

- Impact of removing SGFM (w/o SGFM): Removing SGFM results in an increase of 38 km in mean error, 4 km in median error, and a 1.1% decrease in Acc@161. This suggests that different types of social relationships contain complementary geographic information and SGFM enables effective fusion of these signals within multi-relational networks, facilitating a more comprehensive modeling of spatial interactions among users. Without this fusion mechanism, the model can only learn geographic dependencies from individual types of social relationships, thereby limiting its ability to capture complex spatial structures.

In summary, IKSM and SGFM serve complementary roles within the model: IKSM enhances the discriminative capacity of textual signals, while SGFM strengthens the comprehensive modeling of heterogeneous social relationships. Their combined effects significantly boost the geolocation inference performance of MGFGCN.

5.6.4. Ablation Study of Each Component of Z Within the SGFM (RQ8)

To evaluate the contribution of each component within Z in SGFM, we conducted ablation experiments on the GeoText dataset. Specifically, we examined the impact of removing the absolute difference term and the element-wise product on the performance of Z. The experimental results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ablation study of each component of Z within the SGFM on the GeoText dataset.

Removing either or led to a performance drop, while removing both simultaneously resulted in a more pronounced degradation. This indicates that the two components provide complementary information in capturing heterogeneous relationships and interaction patterns between user representations. The absolute difference term primarily measures the distance and disparity between user features, helping the model identify significant spatial deviations, whereas the element-wise product emphasizes feature co-occurrence and correlation, enhancing sensitivity to potential interaction patterns. By jointly modeling both components, the model can capture both differential and interactive information, generating a more discriminative fused representation and improving geolocation prediction accuracy.

These findings suggest that a single component alone can only provide partial information and cannot fully represent the spatial semantic characteristics of heterogeneous inputs. Only through the synergistic combination of both components can the model fully leverage the complementary strengths of heterogeneous information, thereby achieving higher localization accuracy.

5.7. Sensitivity Analysis of Co-Mention and 2-Hop Neighbor Mechanism (RQ9)

To evaluate the contribution of co-mention edges and the 2-hop neighbor mechanism to geolocation inference and to verify the robustness of the results with respect to graph construction parameters, we conducted a lightweight sensitivity analysis on the GeoText dataset. In this experiment, we varied the settings of co-mentions, 2-hop, and , with the specific configurations and results presented in Table 6. Since the 2-hop neighbor mechanism is only applied when co-mention is enabled, only the off/off and on/on combinations were considered. The results show that simultaneously disabling co-mentions and the 2-hop mechanism leads to a performance drop, whereas enabling co-mentions combined with the 2-hop mechanism consistently improves performance, indicating that second-order neighbor information provides richer social structure, which benefits geolocation prediction. Although increasing the threshold slightly reduces accuracy, the overall trend remains consistent; coverage is 100% across all configurations. Overall, variations in the parameter of graph construction have a limited impact on model performance, confirming the robustness of the main experimental conclusions.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of co-mention and 2-hop settings on the GeoText dataset.

5.8. Performance and Complexity Comparison of Gated Fusion Mechanisms (RQ10)

Table 7 presents a comparison of the performance and complexity of three gated fusion mechanisms. SGFM outperforms both BasicGatedFusion [40] and AttnGatedFusion [41] across all metrics (Acc@161, mean, and median), demonstrating not only its numerical superiority but also its enhanced ability to capture geographically sensitive features in text. Specifically, SGFM considers both the difference and the product of input features during fusion, enabling the model to better exploit complementary information among features, thereby improving the discriminative power for geographic labels. In contrast, BasicGatedFusion is lightweight but only employs simple linear gating for feature fusion, which limits its ability to leverage feature interactions; AttnGatedFusion introduces dynamic weight adjustment, providing more flexibility, but attention weights may be difficult to learn stably under noisy social text, leading to slightly lower performance.

Table 7.

Comparison of performance and complexity for gated fusion mechanisms on the GeoText dataset.

In terms of model complexity, since the core computations of SGFM still primarily rely on linear transformations, its forward propagation time complexity remains , the same as BasicGatedFusion and AttnGatedFusion. This indicates that SGFM significantly enhances expressive and discriminative capabilities without introducing additional computational overhead.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a multi-graph convolutional network with feature fusion to infer the geographic locations of Twitter users. The proposed method extracts multi-dimensional information from social networks by constructing both a mention graph and a retweet graph, enabling comprehensive modeling of complex user interactions. Meanwhile, by integrating IGR and TF-IDF, the model identifies geo-discriminative keywords from users’ historical tweets, thereby enhancing the semantic expressiveness of user node representations. Based on this, the SGFM is introduced to adaptively fuse features from different social relationship graphs, further improving the model’s ability to capture geographic cues. Notably, spatial patterns in MGFGCN emerge through a multi-step process: textual features are first encoded at the node level to capture location-specific signals, then refined through multi-graph interactions that propagate information across different types of social relationships, and finally integrated via a structure-aware gated fusion mechanism. This design enables the model to effectively capture user-level spatial correlations and encode spatial semantics, addressing the limitations of models that rely solely on structured data or single-graph inputs. Experimental results on two real-world Twitter datasets demonstrate that MGFGCN significantly outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in multiple metrics, including Acc@161, mean, and median, verifying its effectiveness and robustness in the user geolocation task on social media.

Despite its promising performance, the proposed MGFGCN framework has certain limitations. It faces challenges in extracting geographic information from complex texts and inference efficiency, restricting its application in large-scale location inference. Future work will focus on integrating knowledge graphs and optimizing model lightweight design to enhance performance and efficiency. Moreover, although this study focuses on U.S. users and their real tweets, stylistic generalization and cross-domain adaptability remain important considerations. Subsequent research could extend the training data to other regions and styles and enhance the model’s cross-domain generalization to further improve robustness and applicability. In addition, efforts will be made to provide more detailed geospatial visualization outputs, enhancing the spatial interpretability of the results and offering clearer insights into the learned geographic patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Qiongya Wei; methodology, Qiongya Wei and Shuaihui Zhu; software, Qiongya Wei; validation, Aobo Jiao and Qingqing Dong; formal analysis, Qiongya Wei; investigation, Qingqing Dong and Aobo Jiao; resources, Qiongya Wei; writing—original draft preparation, Qiongya Wei; writing—review and editing, Yaqiong Qiao and Qiongya Wei; visualization, Aobo Jiao; supervision, Yaqiong Qiao; project administration, Yaqiong Qiao; funding acquisition, Yaqiong Qiao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 62272163].

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available and was originally provided by Afshin Rahimi et al. It can be accessed via the following Dropbox link: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/vofn0awjcjxhwbc/AABHekl2pmFk2Q3qdVO60JTKa?dl=0 (accessed on 11 March 2024). This dataset was originally created by Afshin Rahimi et al. and published in 2017. The full citation is as follows: Afshin Rahimi, Trevor Cohn, and Timothy Baldwin. 2017. A Neural Model for User Geolocation and Lexical Dialectology. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 209–216, Vancouver, Canada. Association for Computational Linguistics. Please cite the original paper when using this dataset.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Tensor shapes of variables (N: number of users, d: hidden dimension).

Table A1.

Tensor shapes of variables (N: number of users, d: hidden dimension).

| Symbol | Tensor Shape | Description |

|---|---|---|

| User node embeddings obtained from and X | ||

| User node embeddings obtained from and X | ||

| Z | Gating input matrix | |

| G | Gating weights for adaptive fusion of node embeddings | |

| H | Final user node representation |

References

- Gardasevic, S.; Jaiswal, A.; Lamba, M.; Funakoshi, J.; Chu, K.H.; Shah, A.; Sun, Y.; Pokhrel, P.; Washington, P. Public Health Using Social Network Analysis During the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. Information 2024, 15, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lin, H.; Gou, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, M.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Hu, B. A Dynamic and Timely Point-of-Interest Recommendation Based on Spatio-Temporal Influences, Timeliness Feature and Social Relationships. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Su, T.; Zhao, W. Understanding Urban Park-Based Social Interaction in Shanghai During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from Large-Scale Social Media Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.; Keydar, R.; Abend, O. Event-Location Tracking in Narratives: A Case Study on Holocaust Testimonies. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y. Keyword Targeting Optimization in Sponsored Search Advertising: Combining Selection and Matching. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 56, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Qiao, Y.; Li, C.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. An Overview of Microblog User Geolocation Methods. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, U.; Imran, M.; Ofli, F. GeoCoV19: A Dataset of Hundreds of Millions of Multilingual COVID-19 Tweets with Location Information. ACM Sigspatial Spec. 2020, 12, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zola, P.; Cortez, P.; Carpita, M. Twitter User Geolocation Using Web Country Noun Searches. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 120, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, U.; Sheth, P.; Tahir, A.; Alatawi, F.; Bernard, H.R.; Liu, H. Exploring Platform Migration Patterns Between Twitter and Mastodon: A User Behavior Study. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Buffalo, NY, USA, 3–6 June 2024; pp. 738–750. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lu, C.T.; Qu, Y.; Yu, P.S. Collective Geographical Embedding for Geolocating Social Network Users. In Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 23–26 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Ohkuma, T. A Simple Scalable Neural Networks Based Model for Geolocation Prediction in Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Noisy User-generated Text (WNUT), Osaka, Japan, 11 December 2016; pp. 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Jiang, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Young, S.D.; Wang, W. Social Media User Geolocation Via Hybrid Attention. In Proceedings of the Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, S.; Pappa, G.L. Strategies for Combining Twitter Users Geo-Location Methods. GeoInformatica 2017, 22, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, F.; Martins, B. Automated Geocoding of Textual Documents: A Survey of Current Approaches. Trans. GIS 2016, 21, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, F.; Luo, X.; Zhang, F.; Qiao, Y. Microblog User Geolocation by Extracting Local Words Based on Word Clustering and Wrapper Feature Selection. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, W.; Huang, B.; Carley, K.M.; Zhang, Y. RATE: Overcoming Noise and Sparsity of Textual Features in Real-Time Location Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Singapore, 6–10 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Cohn, T.; Baldwin, T. A Neural Model for User Geolocation and Lexical Dialectology. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, D. That is What Friends Are For: Inferring Location in Online Social Media Platforms Based on Social Relationships. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Cambridge, MA, USA, 8–11 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Zhang, Y. Location Prediction: Communities Speak Louder Than Friends. In Proceedings of the Conference on Online Social Networks, Dublin, Ireland, 1–2 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, T.; Zhong, T.; Trajcevski, G. Identifying User Geolocation with Hierarchical Graph Neural Networks and Explainable Fusion. Inf. Fusion 2022, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Vu, D.; Cohn, T.; Baldwin, T. Exploiting Text and Network Context for Geolocation of Social Media Users. In Proceedings of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Denver, CO, USA, 31 May–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Ohkuma, T. Unifying Text, Metadata, and User Network Representations with a Neural Network for Geolocation Prediction. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, M.; Luo, X.; Liu, F.; Qiao, Y. Twitter User Location Inference Based on Representation Learning and Label Propagation. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Xiong, W.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, X.; Yang, K. SRGCN: Social Relationship Graph Convolutional Network-Based Social Network User Geolocation Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Human–Computer Interaction (ICHCI), Guangzhou, China, 2–4 June 2023; pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Carley, K.M. A Hierarchical Location Prediction Neural Network for Twitter User Geolocation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Med. 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Belghazi, M.I.; Baratin, A.; Rajeswar, S.; Ozair, S.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Hjelm, R.D. MINE: Mutual Information Neural Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fida, M.A.F.A.; Ahmad, T.; Ntahobari, M. Variance Threshold As Early Screening to Boruta Feature Selection for Intrusion Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and System (ICTS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 20–21 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Han, Z.; Wu, X.M. Deeper Insights into Graph Convolutional Networks for Semi-Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, J.; O’Connor, B.; Smith, N.A.; Xing, E.P. A Latent Variable Model for Geographic Lexical Variation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Cambridge, MA, USA, 9–11 October 2010; pp. 1277–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Do, T.H.; Nguyen, D.M.; Tsiligianni, E.; Cornelis, B.; Deligiannis, N. Twitter User Geolocation Using Deep Multiview Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; pp. 6304–6308. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Cohn, T.; Baldwin, T. Twitter User Geolocation Using a Unified Text and Network Prediction Model. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; Zong, C., Strube, M., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Beijing, China, 2015; Volume 2: Short Papers, pp. 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, B.; Baldridge, J. Hierarchical Discriminative Classification for Text-Based Geolocation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 336–348. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, S.; Speriosu, M.; Rallapalli, S.; Wing, B.; Baldridge, J. Supervised Text-Based Geolocation Using Language Models on an Adaptive Grid. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 12–14 July 2012; pp. 1500–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Cook, P.; Baldwin, T. Geolocation Prediction in Social Media Data by Finding Location Indicative Words. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Mumbai, India, 8–15 December 2012; pp. 1045–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Baldwin, T.; Cohn, T. Continuous Representation of Location for Geolocation and Lexical Dialectology Using Mixture Density Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Cohn, T.; Baldwin, T. Semi-supervised User Geolocation Via Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Wang, T.; Zhou, F.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y. Interpreting Twitter User Geolocation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Qi, X.; Zhang, K.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhong, T. MetaGeo: A General Framework for Social User Geolocation Identification with Few-Shot Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 8950–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo, J.; Solorio, T.; y Gómez, M.M.; González, F.A. Gated Multimodal Units for Information Fusion. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Gieseke, F.; Oehmcke, S.; Wu, Y.; Barnard, K. Attentional Feature Fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Tucson, AZ, USA, 28 February–4 March 2020; pp. 3559–3568. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).