Abstract

Urban heat exposure, which intensifies with climate change, poses serious threats to public health in rapidly growing cities. Traditional assessments rely on static land surface temperature, often overlooking the role of human mobility in exposure frequency. This study introduces a travel-related heat exposure index (THEI) that combines ride-hailing trajectories and remote sensing data to capture dynamic human–environment thermal interactions. Using Chengdu, China, as a case study, the THEI is combined with local indicators of spatial association to outline high-exposure risk zones (HERZ). XGBoost with SHAP and partial dependence plot (PDP) methods is also applied to identify the nonlinear effects of built environment factors. Results showed the following: (1) distinct spatial clustering of high travel-related heat exposure in central urban districts and transit hubs; (2) city-wide exposure is primarily driven by transportation accessibility and urban form, such as intersection density and floor area ratio; (3) in contrast, HERZ are more strongly associated with demographic and socioeconomic factors, including population density, housing price and road density; and (4) vegetation, measured by the normalized difference vegetation index, demonstrates a consistent negative effect across scales, highlighting its critical role in mitigating thermal risks. These findings emphasize the necessity of incorporating mobility-based exposure metrics and spatial heterogeneity into climate-resilient urban planning, with differentiated strategies tailored for city-wide versus high-risk zones.

1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change, the frequency of extreme heat events has markedly increased, posing serious threats to human health and urban environmental sustainability [1]. As highly concentrated centers of human activity, cities experience intensified microclimatic changes than non-urban areas. The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, a well-documented byproduct of urbanization, leads to persistently elevated land surface and ambient temperatures compared to surrounding rural areas. This effect is mainly exacerbated during summer heatwaves, notably increasing the heat exposure of residents and associated health risks [2]. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, urban heat risks have become a central issue in the discussion on public health in metropolitan areas [3].

Notably, actual exposure of an individual to high-temperature environments is not determined by ambient temperature alone but is influenced by their spatiotemporal activity patterns [4,5]. In recent years, urban governance practices have increasingly emphasized interventions such as optimization of spatial configurations, improvement of green space coverage and construction of urban ventilation corridors to alleviate thermal stress. For example, many European cities have incorporated ‘climate-adaptive design’ into their master plans [6]. Meanwhile, U.S. cities have implemented ‘Cool Cities’ initiatives, using reflective materials and urban greening to minimize heat load [7]. In China, urban adaptation strategies under frameworks, such as ‘carbon peak–carbon neutrality’ and ‘resilient cities’, are transitioning from ecological regulation to behavior-oriented environmental governance.

Against this background, environmental science and epidemiology have gradually introduced the concept of heat exposure to capture the actual degree of thermal contact experienced by individuals. This concept posits that exposure level is jointly determined by ‘hazard intensity × exposure frequency’ [8], a theoretical model based on exposure science and environmental health assessment, and currently widely applied in heat-related health studies [9]. In densely populated and highly mobile urban environments, the spatial convergence of human behavior and thermal risk has become increasingly prominent, prompting the emergence and evolution of urban heat exposure as a multidimensional framework for risk assessment [10,11].

Current studies have generally employed two main approaches to investigating urban heat exposure mechanisms. One approach focuses on thermal characteristics derived from remote sensing, using data such as LST to evaluate the spatial distribution of urban thermal risks [12]. The other incorporates mobility data—including mobile phone location records, public transit smart card data and ride-hailing trajectories—to measure heat exposure pathways and behavioral dimensions of exposure [13,14]. Furthermore, the built environment is increasingly recognized as a crucial intermediary linking the ‘occurrence–transmission–perception’ of heat exposure. Spatial structure, land use mix (LUM) and road density (RD) influence human mobility, indirectly affecting the risk of thermal exposure [15,16]. Building on these research approaches, scholars have developed various heat exposure indices (HEIs) and heat vulnerability indices (HVIs) to identify high-risk populations and guide mitigation efforts. These indices typically adopt a tripartite framework that integrates hazard (e.g., land surface temperature), exposure (e.g., population density) and vulnerability (e.g., age, chronic disease rates) factors [17,18]. These tools, which have been widely applied in cities across the US and Europe [19,20], are valuable for targeting intervention measures. However, they share limitations with broader existing research.

The following limitations remain in the existing literature: (1) A lack of integrated indicators that simultaneously account for ‘thermal intensity’ and ‘behavioural frequency’, which hinders accurate characterization of spatial heterogeneity in dynamic heat exposure. (2) Identification of high-risk heat exposure zones has often relied on temperature thresholds or subjective delineation, with insufficient application of spatial statistical clustering methods. (3) Relationships between the built environment and heat exposure have largely been explored using linear models, failing to determine underlying nonlinear and threshold dynamics [21].

Aiming to bridge these gaps, this study introduces the travel-related heat exposure index (THEI) by using ride-hailing order data as a proxy for dynamic human activity. By integrating normalized travel intensity and surface temperature, THEI serves as a quantifiable indicator of dynamic thermal contact. The index is grounded in a ‘hazard intensity × exposure opportunity’ framework, highlighting the interactive nature of human–environment exposure mechanisms.

Based on the constructed THEI, Local Moran’s I analysis is further applied to identify high-exposure risk zones (HERZs) and uncover their spatial clustering patterns. Leveraging the XGBoost model and the interpretability-enhancing Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and partial dependence plot (PDP) techniques, the nonlinear drivers of THEI are explored, and marginal and threshold effects of built environment factors are outlined.

This study focuses on the central urban districts of Chengdu, one of the largest megacities in China. It synthesizes ride-hailing trajectories from DiDi, MODIS satellite remote sensing data and spatial network/POI data from Gaode Maps across 11,525 urban grids. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Chapter 2 outlines the theoretical foundation and methodological framework, including THEI construction, LISA analysis, the XGBoost model and interpretability techniques. Chapter 3 presents the results, detailing the spatial distribution of THEI in Chengdu, HERZ identification and the driving mechanisms of built environment factors. Chapter 4 provides an in-depth discussion of theoretical implications, practical relevance, limitations and directions for future research. Chapter 5 concludes the study and proposes targeted policy recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of urban residents’ heat exposure during travel and its spatial distribution patterns, this study constructs an integrated framework that combines exposure measurement, spatial clustering analysis, and causal inference. The analysis revolves around the Travel-related Heat Exposure Index (THEI), with the aim of identifying areas with high heat exposure intensity and frequent mobility, and further exploring the nonlinear driving mechanisms of the built environment.

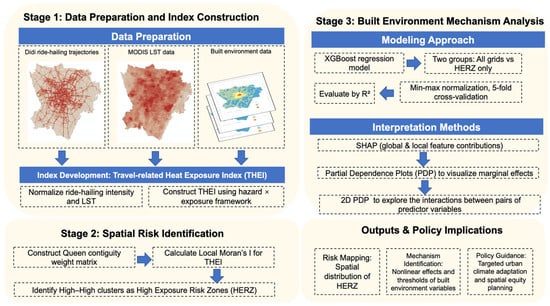

This methodological framework not only emphasizes quantifying the spatial heterogeneity of urban heat exposure but also highlights the interactive mechanisms between human behavior and the environment. The framework also provides theoretical and technical support for urban heat–health governance and spatial equity interventions. As shown in Figure 1, the framework includes the following three key steps:

- (1)

- Construction of the THEI: Based on ride-hailing travel intensity and Land Surface Temperature (LST) data, a composite heat exposure indicator is developed to reflect the interaction between human activity and thermal environments, following the modeling logic of “risk intensity × exposure frequency”.

- (2)

- Spatial Clustering of Exposure Risk: Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) are used to detect High–High clusters of THEI, delineating High-Exposure Risk Zones (HERZ) at the city scale.

- (3)

- Nonlinear Impact Analysis: An XGBoost model is employed to capture the intricate nonlinear relationships between built environment factors and the THEI. Separate models are constructed for both the full sample and the HERZ subset. To enhance the model’s interpretability and identify key variables along with their threshold effects, SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) values and PDP (Partial Dependence Plots) methods are utilized. Additionally, the Two-Dimensional Partial Dependence (2D PDP) approach is introduced to explore the interactions between pairs of predictor variables and their joint influence on the THEI. By incorporating 2D PDP, the analysis provides more nuanced insights into how multiple factors, such as building density, transportation accessibility, and green space, interact to shape heat exposure risk in urban environments.

Figure 1.

Research Technical Roadmap.

2.1. Study Area

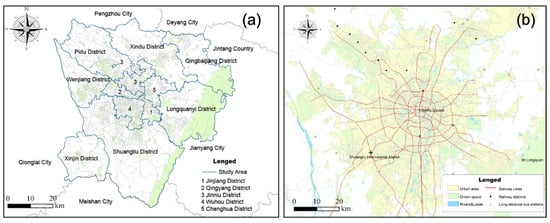

The study area is located in the central urban districts of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (102°54′ E–104°53′ E, 30°05′ N–31°26′ N), on the eastern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and the western margin of the Sichuan Basin. With a population of 21.192 million, Chengdu is one of the most important core cities in western China, serving as the center of both the Chengdu–Chongqing economic circle and the Chengdu metropolitan area.

In recent years, the urban heat island effect in Chengdu has been intensifying due to a combination of enclosed terrain, rapid urban expansion, and increased human activity. The number of high-temperature days in summer has been rising significantly, making urban thermal challenges increasingly prominent and posing serious risks to ecological adaptation and public health.

The study area includes 12 administrative districts: Jinjiang, Qingyang, Jinniu, Wuhou, Chenghua, Longquanyi, Qingbaijiang, Xindu, Wenjiang, Shuangliu, Pidu, and Xinjin, covering a total area of 3639.81 km2 (Figure 2). A grid system consisting of 11,525 cells, each measuring 600 m × 600 m, was created to accurately describe and analyze the spatial distribution of features within the study area [22,23,24]. This resolution was determined based on street block size, the spatial distribution of travel trajectory data, the overall study scale, and references from previous studies. Specifically, the 600 m × 600 m grid size was selected to balance spatial detail and data noise, offering a compromise between finer resolutions (e.g., 250 m or 500 m) that may introduce excessive noise from localized anomalies, and coarser scales (e.g., 1 km) that might obscure fine-grained spatial patterns. This resolution effectively captures urban morphological features, such as street blocks and transit hubs, while reducing the impact of data irregularities, ensuring robust spatial representation across Chengdu’s diverse urban landscape. The ride-hailing data, sourced from DiDi, spans the entire month of July 2021, aggregated to daily averages to reflect typical travel patterns during summer heat events, though it does not include hourly variations due to time and workload constraints. This temporal scope captures peak travel activity and heat exposure trends during the hottest month, aligning with the study’s focus on heat-related risks, though future research will explore hourly dynamics to refine these patterns.

Figure 2.

Study area. (a) shows the scope of the study area; (b) shows the distribution of some spatial elements in the study area.

For the purpose of spatial analysis, all geographic data were standardized based on the China Geodetic Coordinate System 2000 (CGCS2000) and subsequently projected to the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) Zone 48N.

2.2. Construction of the Travel-Related Heat Exposure Index (THEI)

2.2.1. Selection of Travel Intensity Indicator

In characterizing residents’ dynamic heat exposure under high-temperature conditions, selecting high-resolution data that accurately reflects spatiotemporal patterns of human activity is essential. Prior studies often relied on static proxies such as population density or residential layouts, which fail to capture the dynamic heterogeneity of actual activity paths and environmental contact behaviors [25].

In contrast, ride-hailing data offers high frequency, real-time accuracy, and behavior-driven characteristics, making it an increasingly important data source for exploring the coupling between urban mobility and environmental exposure [26,27]. As a demand-responsive transport mode, ride-hailing is an indicator of real spatial trajectories and behavioral responses to external disturbances such as thermal stress [28].

Studies have shown that ride-hailing intensity is significantly associated with high-temperature conditions, and its frequency and timing are sensitive to heat risk. During extreme heat or heatwave events, residents tend to prefer air-conditioned ride-hailing over walking or public transit, reflecting high environmental–behavioral sensitivity [29,30]. Notably, while ride-hailing may reduce exposure during the ride, the act of traveling still involves exposure during waiting, boarding, and walking segments, thus reflecting real exposure frequency and activity distribution. Therefore, ride-hailing order data not only captures daily travel structure but also serves as a valid dynamic proxy for exposure frequency in heat exposure analysis [31].

The data used in this study were obtained from DiDi’s GAIA Open Data Initiative (https://outreach.didichuxing.com/research/opendata/). This platform provides real-world, anonymized ride trajectory data for academic research. We selected ride-hailing orders from July 2021 and used Python 3.14 tools to slice and filter the dataset, obtaining 333,101,321 records within the study area and grid resolution. Each record includes order ID, GPS coordinates, timestamp, direction, administrative unit code, road name, and road classification.

2.2.2. Land Surface Temperature (LST)

Land surface temperature data were derived from the MODIS MOD11A1 product, which is part of NASA’s “Terra” satellite program launched in 2000. This product provides daily LST and various other remote sensing parameters. We computed the average LST for July 2021 and resampled the data to 600 m using bilinear interpolation to match the spatial resolution of the analysis grid. The “Zonal Statistics as Table” tool in GIS was used to extract the mean LST value for each grid cell, which serves as an indicator of the urban heat island effect.

2.2.3. Construction of the Travel-Related Heat Exposure Index

This study introduces the THEI to quantify the intensity of heat exposure experienced by urban residents during travel. The index is constructed as the product of the normalized travel intensity and the normalized LST. The formula is defined as follows:

where Ti represents the travel intensity in grid i, and LSTi denotes the LST in the same grid. This formulation follows the classical modeling logic in exposure science, where exposure is expressed as the product of “hazard intensity × contact frequency” [32,33,34], effectively capturing the spatial distribution of heat exposure across urban areas.

This index reflects a cumulative exposure mechanism, indicating that significant heat risk arises only when both temperature and human activity reach high levels. In other words, neither high temperature alone nor high mobility alone constitutes meaningful exposure—both must coincide to produce risk [9,35]. Compared to metrics that rely solely on temperature or behavioral indicators, THEI offers a more comprehensive and sensitive approach to identifying hotspots of human–environment thermal interaction [36].

Furthermore, this dynamic metric aligns with emerging exposure assessment paradigms that emphasize temporal mobility, spatial context, and behavioral embeddedness [20,37]. It thus provides a solid theoretical and methodological foundation for urban thermal health governance and equitable spatial planning under conditions of climate change.

2.2.4. Identification Method of High-Exposure Risk Zones

To further identify areas with significantly elevated heat exposure and examine their spatial distribution, we introduce LISA to delineate HERZ. This method reveals local spatial dependencies between grid cells and is widely used in research on environmental exposure, health risk, and spatial inequality [9].

Based on THEI values at the grid level, we first construct a spatial weight matrix using Queen contiguity to define neighborhood relationships. Then, we compute Local Moran’s I to assess spatial autocorrelation in THEI values.

Through significance testing (typically using a p-value threshold of 0.05), spatial units are categorized into four types: High–High, Low–Low, High–Low, and Low–High. High–High clusters indicate that both the focal grid and its neighboring grids exhibit high-exposure levels, representing areas of elevated risk and potential vulnerability to thermal hazards [12,38]. These clusters are thus defined as HERZ.

This method identifies not only high-exposure individual units but also whether these units are embedded in broader “heat hotspots”, avoiding the subjectivity and random error associated with simple threshold-based classification [39]. Compared to basic temperature-based definitions, LISA offers a risk identification mechanism supported by both statistical significance and spatial structure, making it particularly suitable for urban contexts characterized by spatial spillover or neighborhood effects.

2.3. Construction of Built Environment Variables

This study constructs a set of built environment indicators to investigate the driving mechanisms behind heat exposure during travel, drawing on the existing literature and data availability. These indicators cover five dimensions: urban form, urban vitality and functional diversity, neighborhood characteristics, public transport infrastructure, and other relevant factors. A total of sixteen variables are selected, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of built environment.

Urban form reflects the physical layout and structural characteristics of the built environment, including floor area ratio (FAR), building density (BD), intersection density (InS), road density (RD), and the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). FAR represents the ratio of total built floor area to land area within each grid and serves as an indicator of development intensity. Building density refers to the percentage of ground surface occupied by building footprints. Intersection and road density measure the complexity of the road network and its accessibility, which in turn influence travel behavior. The NDVI, derived from remote sensing data, captures vegetation coverage and ecological quality, which can help alleviate urban heat through evapotranspiration and shading.

Urban vitality and functional diversity are closely associated with the spatial intensity and diversity of human activity. Based on point of interest (POI) data from Gaode Map’s open platform, this study calculates facility densities across six categories, including shopping, accommodation, and entertainment. Zero inflation in the variables is reduced by retaining only categories with sufficient distribution. The Shannon Diversity Index (SHDI) is also employed to measure land use mix, where higher SHDI values signify greater functional diversity. This, in turn, may influence the frequency and complexity of travel behaviors, ultimately affecting the degree of heat exposure.

Neighborhood characteristics affect both travel demand and behavioral responses to environmental stressors. Considering data availability, this study includes population density (sourced from the WorldPop 2021 dataset), average building age, and housing prices (obtained through web scraping from Anjuke, a real estate platform) as indicators. These variables reflect the socioeconomic status of residents and the stage of urban development, which may modulate travel choices and vulnerability to heat exposure.

The accessibility and coverage of public transportation infrastructure also shape travel behavior and heat exposure pathways. Based on data from Gaode Map, two indicators are selected: the density of bus and subway stations, and the density of transit lines within each grid. Higher accessibility is generally associated with increased travel frequency and modal diversity, which may elevate exposure risk during high-temperature conditions, particularly for modes involving outdoor walking or waiting.

A correlation analysis was conducted using a global model (Appendix A) to address multicollinearity issues in subsequent model computations. The correlation matrix revealed that BD and FAR exhibit a correlation coefficient exceeding 0.7, indicating a high degree of collinearity between the two variables. Multicollinearity emerges under highly correlated independent variables, which can distort regression results by producing unstable parameter estimates, inflated standard errors and difficulties in determining the individual contributions of each variable to the model. In such cases, the predictive power of the model remains intact. However, the interpretability and reliability of the coefficients are compromised, potentially resulting in misleading conclusions regarding the relationships between variables. Aiming to address this problem, this study excluded BD from the analysis. BD is removed because FAR captures a broader aspect of urban development intensity by incorporating the ground coverage (similar to BD), thereby making it a more comprehensive indicator. Retaining FAR whilst removing BD reduces redundancy without substantial loss of information, enhancing the overall stability and validity of the subsequent modeling process.

2.4. XGBoost Modeling of Nonlinear Mechanisms

Aiming to explore the nonlinear relationships between built environment variables and THEI, this study employs the XGBoost algorithm, a machine learning technique developed by Chen and Guestrin. XGBoost is widely adopted in urban and environmental studies due to its capability to model complex nonlinearities [31,32,33], handle multicollinearity amongst predictors and maintain robust performance under imbalanced sample distributions. This algorithm outperforms traditional linear regression and standard random forest models, particularly in capturing threshold effects and high-order interactions amongst variables.

Two models were constructed: a full-sample model covering 11,525 grid cells and a HERZ model based on a subset of 1652 grid cells identified by LISA analysis. Five-fold cross-validation was applied (80% training, 20% validation per fold) to evaluate generalization performance, with training and validation R2 values reported to ensure robustness. All fifteen predictors from Table 1 were normalized prior to training, and models were implemented in the R statistical environment (version 4.2.1) using the xgboost package.

Hyperparameters were tuned using grid search within the cross-validation framework to optimize for generalization while avoiding overfitting. For the full-sample model, designed for a large dataset, conservative parameters were selected: max_depth of 4 to limit tree complexity, eta (learning rate) of 0.05 for gradual updates, subsample of 0.7 to introduce randomness, colsample_bytree of 0.7 for column sampling, and early_stopping_rounds of 20 to halt training if the validation mean squared error (MSE) did not improve. This model achieved an overall R2 of 0.72 (defined as the average R2 across the five validation folds), with average training and validation R2 values of 0.77 and 0.68, respectively.

The HERZ model, which is built on a smaller dataset, required parameters that help maintain learning efficiency and generalization: max_depth of 4, eta of 0.15 for faster convergence, subsample of 0.75, colsample_bytree of 0.75 and early_stopping_rounds of 20. Early stopping was employed to prevent overfitting, because small datasets are highly susceptible to excessive model complexity. This model dynamically halted training when the validation MSE stabilized, ensuring robustness despite the limited sample size (1652 grid cells, with approximately 330 validation samples per fold). The HERZ model also yielded an overall R2 of 0.63 (defined as the average R2 across the five validation folds), with average training and validation R2 values of 0.66 and 0.52, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameters Setting of XGBoost Models.

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was incorporated to enhance interpretability. Based on cooperative game theory, SHAP offers a consistent and locally accurate method for attributing feature contributions, allowing for the analysis of variable importance and the directionality of their effects. Compared to traditional importance measures, SHAP offers higher fidelity in estimating marginal contributions, providing a nuanced understanding of predictor influences

2.5. Partial Dependence Plot (PDP) Analysis of Variable Effects

In order to better visualize and interpret the marginal effects of built environment variables on THEI, this study further adopts the partial dependence plot (PDP) method. PDP evaluates the partial influence of a single independent variable on the predicted value of the dependent variable by simulating changes in that variable while holding all others constant. The resulting curve reflects the functional relationship between the variable of interest and the outcome variable, capturing nonlinear trends, interaction effects, and critical threshold points.

Based on the trained XGBoost models, PDPs are generated for all sixteen explanatory variables in both the full sample and HERZ models. The results reveal a range of nonlinear patterns. For example, building density exhibits an amplifying effect on THEI in high-density areas, suggesting that marginal increases in density under already dense conditions significantly exacerbate heat exposure. Similarly, the NDVI demonstrates a diminishing marginal effect, indicating that its cooling capacity plateaus beyond a certain vegetation coverage level.

For a deeper analysis, this study introduces the Two-Dimensional Partial Dependence (2D PDP) method to explore the interactions between pairs of predictor variables and their combined influence on THEI. The 2D PDP approach reveals higher-order, nonlinear effects that are not captured by one-dimensional PDPs, providing more nuanced insights into how multiple factors, such as building density, transportation accessibility, and green space, interact to shape heat exposure risk. These findings offer actionable insights for urban spatial governance and provide empirical evidence to inform regulatory thresholds and design standards. By identifying sensitive ranges and key turning points in the influence of built environment features, PDP enables more targeted policy interventions that enhance heat resilience and spatial equity.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Travel-Related Heat Exposure Patterns in the Study Area

The spatial distribution of THEI in the study area is revealed by integrating ride-hailing travel intensity with LST to construct the THEI. By comparing exposure levels across different areas, we can visualize the interplay between mobility behaviors and the urban heat island effect.

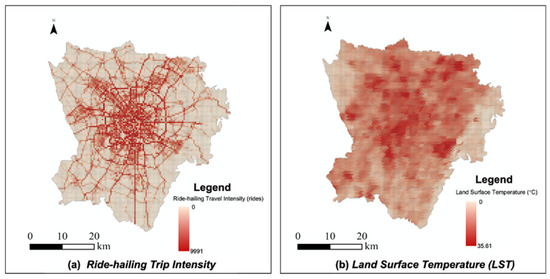

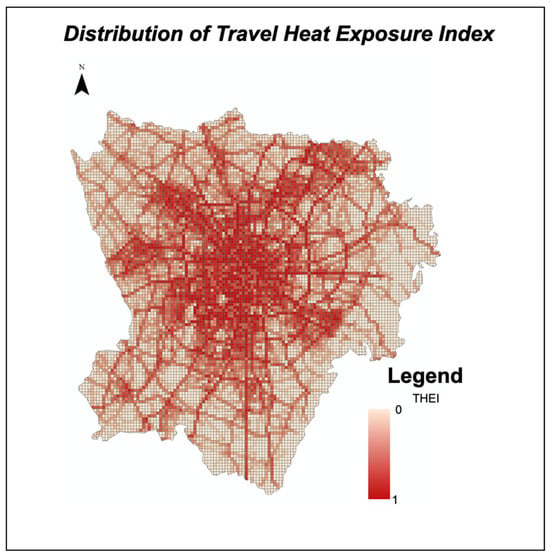

Figure 3 presents the spatial distribution of travel intensity and LST in the study area. Comparison of Figure 3a,b shows that travel intensity and LST values are significantly higher in the urban center, particularly in mixed-use commercial and residential zones, which directly contributes to the formation of high heat exposure risks. Figure 4 illustrates the overall spatial distribution of THEI, clearly indicating that central areas experience high-exposure levels, while peripheral areas are subject to lower exposure, exhibiting notable spatial heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Key Heat-Related Factors. (a) represents Ride-hailing Trip Intensity; (b) represents Land Surface Temperature (LST).

Figure 4.

Distribution of Travel Heat Exposure Index.

A comprehensive analysis of Figure 3 and Figure 4 reveals that high-risk areas for heat exposure are closely associated with travel intensity and surface temperatures. High-traffic zones and commercial hubs emerge as high-risk exposure areas, whereas peripheral areas and those with substantial green coverage demonstrate low exposure, revealing the dual role of geographic environment and transportation activity in determining heat exposure.

Travel intensity, represented by ride-hailing volume, is higher in central urban areas and transportation hubs, particularly in commercial-residential mixed zones (Figure 3a). These zones exhibit both high travel activity and elevated LST (Figure 3b), which leads to significantly increased THEI values. Conversely, urban peripheries and green-covered regions experience lower travel intensity and more moderate temperatures, resulting in notably reduced THEI values.

A clear spatial clustering trend exists between high and low-exposure zones. In high-exposure areas, THEI values are significantly elevated, especially concentrated in the urban core and major transportation hubs (e.g., large commercial districts and transfer stations). These zones feature intense travel activity and, due to high building density, limited green space, and traffic congestion, also exhibit elevated surface temperatures, creating typical “heat island” effects. For example, commercial and residential zones in the city center are areas with high human and vehicular traffic. As ride-hailing intensity increases, the transportation heat load rises, further amplifying heat exposure levels.

Meanwhile, low-exposure zones are mostly located in peripheral urban areas, particularly those with higher greening rates. These areas have lower THEI values, indicating reduced travel-related heat exposure. Such zones often feature extensive green coverage and lower population densities, resulting in less ride-hailing activity and more moderate surface temperatures. By comparing urban core and fringe zones, significant differences in heat exposure levels are evident. Urban areas tend to exhibit higher THEI values, particularly in densely populated and highly built-up regions (e.g., commercial and large residential zones). These areas, benefiting from convenient transportation, also attract intense ride-hailing activity. Moreover, dense building clusters and insufficient green infrastructure contribute to persistently high surface temperatures, intensifying heat exposure, especially during peak hours. In contrast, fringe zones, characterized by lower travel activity and higher vegetation coverage, experience reduced exposure risks and more moderate environmental conditions.

3.2. Spatial Identification of High Heat Exposure Risk Zones

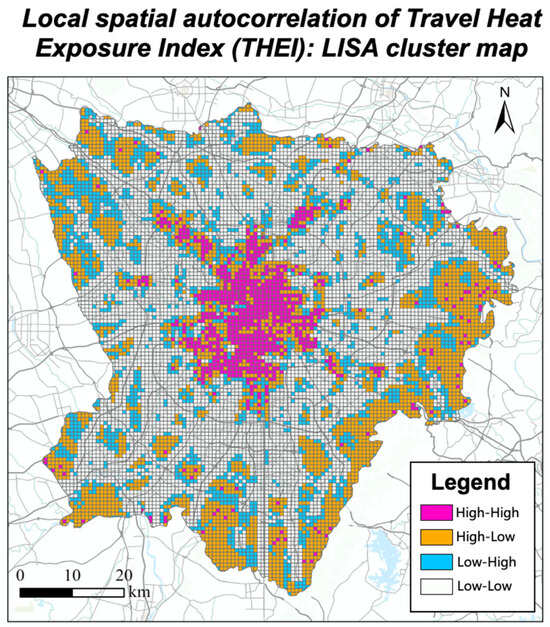

The spatial clustering characteristics of THEI in the study area are identified using the LISA method, resulting in the LISA cluster map (Figure 5). The results classify the study area into four typical spatial association types: High–High, Low–Low, High–Low, and Low–High, representing various relationships between each grid’s THEI value and those of its neighboring units.

Figure 5.

Local Spatial Autocorrelation of Travel Heat Exposure Index (THEI): LISA Cluster Map.

Analysis shows that the study area exhibits a significant positive spatial autocorrelation: areas with high (or low) THEI values tend to be surrounded by similar high (or low) values. The High–High clusters constitute the HERZ identified in this study, mainly concentrated in the urban core and several high-density zones between the second and third ring roads. The HERZ comprises 1635 grids, accounting for approximately 14% of the total study area, though the population ratio exceeds 28%, indicating a disproportionate concentration of heat exposure risk among residents in these zones. The HERZ exhibit the following spatial characteristics and mechanisms:

- (1)

- High–high zones are characterized by both high travel intensity and elevated LST levels, reflecting a combined effect of human activity and urban thermal conditions, embodying a “heat island + activity island” superposition.

- (2)

- These zones are often distributed along main urban roads, high-frequency commuting corridors, and key transportation nodes, demonstrating the strong driving effect of the transportation system on exposure clustering.

- (3)

- Such areas usually have high land use mixing and commercial density, integrating residential, office, and retail functions, which leads to dense human flows and continuous heat emissions.

- (4)

- In contrast, peripheral urban zones are mostly Low–Low clusters, indicating overall lower heat exposure, reduced travel activity, and minimal thermal load.

The identification of HERZ not only reveals the spatial heterogeneity of heat exposure but also provides critical spatial boundaries for subsequent analysis of built environment drivers. This facilitates targeted strategies for urban heat risk intervention and spatial optimization.

3.3. Contribution Analysis of Built Environment Factors to Travel-Related Heat Exposure

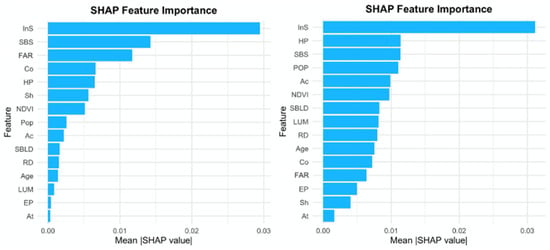

Built environment factors’ influence on travel-related heat exposure is elucidated by employing SHAP to interpret the nonlinear and context-dependent contributions of individual variables. Importance Ranking were used to illustrate factor importance, the direction of influence based on SHAP values, and the interaction between feature magnitude and effect strength, with green and purple representing high and low feature values, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SHAP Importance Ranking, (a) shows SHAP Importance Ranking for the Entire Study Area; (b) shows SHAP Importance Ranking for HERZ.

Across the study area, InS emerged as the most critical factor, demonstrating the highest SHAP values and indicating a substantial increase in exposure due to concentrated traffic flow, anthropogenic heat emissions and disrupted ventilation corridors. Subway and bus station (SBS) distribution also played a key role, reinforcing thermal stress by aggregating pedestrian flows and transit-related activity. The FAR and HP showed moderate to high contributions—FAR intensified heat accumulation in compact urban canyons, whilst HP reflected the socioeconomic centrality of urban cores. Co, Pop and RD provided positive contributions but with weaker effects, indicating that urban form and economic intensity jointly influence exposure patterns. In contrast, the NDVI consistently demonstrated negative associations, highlighting the cooling function of vegetation through evapotranspiration and shading. Other factors, such as land use mix (LUM), shopping point density (Ac) and entertainment point density (EP), demonstrated scattered or weak SHAP values, indicating a limited role at the city-wide scale.

In high-exposure risk zones, the dominant drivers shifted, with human activity intensity indicators becoming more influential relative to spatial morphology. Housing prices (HP), population density (Pop), and road density (RD) emerged as strong contributors, highlighting the concentration of human activity and economic centrality as critical determinants of exposure. Intersection density (InS) remained a consistently important factor, while SBS maintained a moderate contribution. Ration of Floor-area (RFA) showed weaker effects in these zones compared to the overall city scale. Importantly, the NDVI demonstrated stronger negative SHAP values in these areas, suggesting that vegetation provides even greater thermal relief under conditions of intensified human activity and environmental stress.

In contrast, the contributions of localized factors such as shopping and entertainment points were diminished, implying that when demographic and socioeconomic pressures dominate, small-scale infrastructure exerts relatively limited influence. This spatial heterogeneity reveals a structural shift in the mechanisms driving heat exposure: at the city-wide level, exposure is primarily governed by transportation infrastructure and urban morphology, whereas in high-risk zones, activity-related factors take precedence. Such divergence highlights the need for differentiated mitigation strategies: city-scale interventions should prioritize enhancing urban ventilation and moderating built density, while in vulnerable areas, increasing vegetation coverage, regulating road network intensity, and managing socioeconomic centrality are critical to alleviating compounded heat stress.

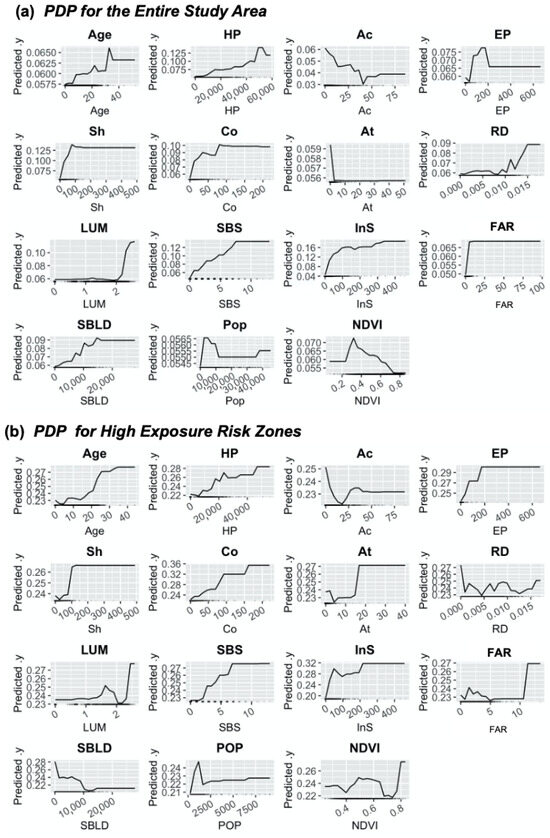

3.4. PDP Analysis of Nonlinear Relationships Between Built Environment and THEI

This study constructs Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) based on XGBoost outputs for all 15 variables, at both the full sample level and the HERZ subsample, to further explore the nonlinear pathways and threshold effects between built environment factors and THEI, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Partial Dependence Plots (PDP). (a) shows PDP for the Entire Study Area; (b) shows PDP for High-Exposure Risk Zones.

In the global model (Figure 7a), several variables exhibit clear nonlinear patterns, indicating complex mechanisms linking the built environment to heat exposure. For example, intersection density (Ins) and subway/bus station density (SBS) both show a rapid increase in THEI at lower ranges before plateauing, suggesting diminishing marginal impacts on exposure once accessibility thresholds are exceeded. Subway and bus line density (SBLD) and population density (Pop) display upward trends with some flattening at higher values, highlighting synergies between urban compaction, human concentration, and heat accumulation. The NDVI curve demonstrates a consistent downward slope, particularly pronounced in the low-to-mid range, underscoring vegetation’s mitigation role through cooling effects, though benefits taper off at higher coverage levels. Socio-demographic variables such as housing prices (HP) and company density (Co) exhibit steady increases, emphasizing the role of economic centrality in elevating exposure, while variables like attraction density (At) and accommodations (Ac) show negative associations, potentially reflecting areas with better connectivity reducing prolonged exposure.

In the HERZ subsample (Figure 7b), response patterns shift significantly. The NDVI exhibits a steeper negative correlation, especially in the mid-range, indicating enhanced cooling efficacy in high-risk zones where heat stress is amplified, aligning with SHAP findings on vegetation’s amplified mitigation potential. PDPs for population density (Pop) and intersection density (Ins) become more pronounced, with sharper upward trajectories and lower thresholds, signaling that demographic intensity and traffic nodes exacerbate exposure risks in vulnerable areas. Meanwhile, traditional morphological indicators such as building density (SBLD) and company density (Co) show downward or flattening trends, suggesting saturation effects where further densification offers limited additional impact. Instead, variables like road density (RD) and land use mix (LUM) display more volatile patterns, pointing to a transition toward activity-driven dynamics, while socioeconomic factors (HP, Age) maintain positive slopes, revealing persistent inequalities linking affluence, aging infrastructure, and heightened vulnerability.

These PDP results jointly demonstrate that the formation mechanisms of travel-related heat exposure vary by spatial scale. At the global level, infrastructure accessibility and urban density dominate as drivers of exposure; in HERZ, demographic intensity, vegetation coverage, and localized activity patterns emerge as key influencers. The findings offer insights into threshold sensitivities, such as the point where additional intersections cease to incrementally raise risks, and underscore the value of targeted greening in high-risk zones to exploit nonlinear cooling benefits. Overall, the results provide strong support for spatially differentiated intervention strategies, prioritizing vegetation enhancement and density management in HERZ to address amplified nonlinear effects.

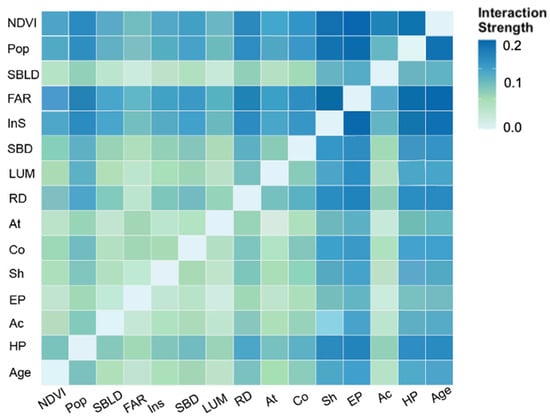

3.5. Interaction Effects of NDVI and Population Density/Floor Area Ratio on THEI

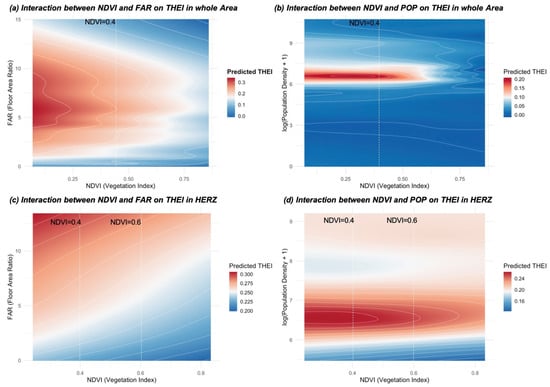

Aiming to determine the interactions between multiple variables that affect THEI, the interaction function is utilized in the iml package to automatically identify the interaction strength amongst features. The interaction strength is visually represented in a heatmap (Feature Interaction Strength Heatmap), where blue blocks indicate strong synergistic interactions, with the maximum strength approaching 0.2, whilst green/white blocks indicate weak interactions, with the minimum value approaching 0.0. Figure 8 shows strong interactions between the NDVI and features such as Pop and RFA. Pop interacts strongly with RAF, InS and other features; RAF exhibits strong interactions with Pop, InS; and InS shows strong interactions with the NDVI, Pop, FAR and BD. Based on these findings, NDVI × Pop and NDVI × FAR were selected for PDP analysis. The two feature combinations were chosen due to the significant positive role of the NDVI in reducing THEI, based on previous analyses (Section 3.4). Investigating the interactions between the NDVI and urban Pop or FAR will help understand the compound effects amongst these variables, providing theoretical support for effective THEI mitigation strategies.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of Feature Interaction Strengths.

Next, we visualized the joint effects of the NDVI and FAR, and NDVI and Pop on THEI predictions by plotting two-dimensional partial dependence plots (2D PDP) for both the full region and the HERZ region. Figure 9 illustrates the interactions between the NDVI and FAR, as well as between the NDVI and Pop, and their impact on THEI. In the full region (Figure 9a), the interaction between the NDVI and FAR indicates that areas with a low NDVI (sparse vegetation) and high FAR (>5) exhibit significantly higher THEI values, presenting a clear risk of high heat exposure. This effect is significantly mitigated in areas where the NDVI > 0.5 (dense vegetation), where THEI remains low regardless of FAR. This suggests that the combination of low vegetation cover and high development intensity exacerbates THEI, while the influence of development intensity is attenuated in areas with denser vegetation, thereby reducing heat exposure risks. Figure 9b explores the interaction between the NDVI and population density (Pop). The results indicate that when population density is moderate (log (Pop + 1) ≈ 6–7), a low NDVI (sparse vegetation) leads to a significant increase in THEI, especially in areas with higher population concentration. In contrast, when population density is either too high (log (Pop + 1) > 8) or too low (log (POP + 1) < 5), the impact of the NDVI becomes weaker. This suggests that the interaction between population density and vegetation is not a simple linear relationship, but rather that the combined effects on THEI are most pronounced within a specific population density range. This finding highlights that moderate population density coupled with low vegetation levels is a key factor in exacerbating heat exposure risks. Figure 9c demonstrates the interaction between the NDVI and FAR in the HERZ sub-region. In this region, when the NDVI is below 0.4, the influence of FAR on THEI is very strong, causing a sharp increase in THEI values. However, once the NDVI exceeds 0.4, even high FAR values result in a rapid decline in THEI. This indicates that the HERZ sub-region is more sensitive to the interaction between vegetation and development intensity, with high development intensity significantly increasing THEI in areas with a low NDVI. This contrasts with the full region analysis, but underscores the stronger influence of vegetation in the HERZ sub-region, revealing regional differences. Finally, Figure 9d examines the interaction between population density and the NDVI on THEI in the HERZ sub-region. When the NDVI is low (<0.6), increasing population density significantly raises THEI, particularly within the population density range of log (POP + 1) ≈ 6–8. In contrast, when the NDVI is high, the impact of population density on THEI diminishes drastically. This result suggests that in the HERZ sub-region, low vegetation and high population density exacerbate heat exposure risks, whereas higher vegetation levels reduce the impact of population density on THEI.

Figure 9.

Two-dimensional partial dependence plots. (a) Shows interaction between NDVI and FAR on THEI in whole area. (b) Shows interaction between NDVI and POP on THEI in whole area. (c) Shows interaction between NDVI and FAR on THEI in HERZ. (d) Shows interaction between NDVI and POP on THEI in HERZ.

Based on the analysis above, we observe that the interactions between features display a hierarchical structure. In the full region, the combination of low vegetation cover and high development intensity significantly exacerbates THEI, while higher vegetation cover reduces the influence of development intensity. In the HERZ sub-region, the effect of vegetation on THEI is more pronounced, especially when NDVI < 0.4, where high development intensity (FAR) sharply increases the heat island effect. This suggests that increasing vegetation in the HERZ sub-region should be a priority for mitigating the urban heat island effect. Moreover, the interaction between population density and vegetation is critical, particularly in areas with medium population density and low vegetation, where the risk of heat island effect is more pronounced. Therefore, future urban planning policies should focus on optimizing population distribution and green space systems, especially in areas with moderate population density and low vegetation, to mitigate the heat island effect and improve urban climate resilience.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications of THEI and Spatial Risk Identification

The introduction of the Travel-related Heat Exposure Index (THEI) represents a significant advancement in urban heat exposure research by integrating dynamic mobility data with thermal metrics. Unlike traditional indices that rely solely on static LST or population density, THEI captures the spatiotemporal interplay of human activity and environmental hazards, offering a more nuanced understanding of exposure risk. The identification of High-Exposure Risk Zones (HERZ) using Local Moran’s I analysis further enhances this framework by pinpointing areas of concentrated thermal and mobility stress, such as commercial centers and transit hubs in Chengdu. This approach aligns with the emerging literature on mobility-based exposure assessment [12,20], providing a robust foundation for spatially targeted interventions.

4.2. Multidimensional Influence Mechanisms of the Built Environment on Travel-Related Heat Exposure

The XGBoost modeling results reveal that built environment factors exert complex, nonlinear influences on travel-related heat exposure across different spatial scales. At the city-wide level, intersection density (Ins), subway and bus station distribution (SBS), and floor area ratio (FAR) emerge as primary drivers, reflecting a morphology-dominated pattern where high accessibility and traffic concentration amplify thermal loads. These findings are consistent with studies on urban form and heat risk [9], emphasizing the structural pathway of “high density–high accessibility–high activity”.

In HERZ, the influence shifts toward activity-driven dynamics. Population density (Pop) and road density (RD) become more prominent, driven by intensified human metabolism and traffic-related emissions. This spatial heterogeneity underscores the need for scale-specific mitigation strategies, a perspective supported by recent urban climate research [9,21].

4.3. Role of NDVI and Green Infrastructure in THEI

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) stands out as a critical mitigating factor across both scales, with its influence amplified in HERZ. The revised PDPs indicate a steeper negative correlation in the mid-range (0.2–0.6), suggesting that green infrastructure provides enhanced cooling benefits where heat stress and human activity are most intense. This nonlinear effect is particularly pronounced when the NDVI interacts with population density (Pop) and land use mix (LUM), as denser activity zones benefit more from vegetation’s shading and evapotranspiration. Unlike the city-wide scale, where the NDVI’s cooling effect plateaus at higher values, HERZ shows positive marginal returns, indicating untapped potential for green interventions.

Further exploration using 2D PDPs reveals synergistic interactions, such as the combined effect of the NDVI and RD, where vegetation offsets heat from traffic emissions more effectively in high-risk areas. This suggests that integrating green spaces with transport planning could optimize thermal relief. Targeted strategies, such as pocket parks or green roofs in mixed-use zones, could leverage these interactions to address the compounded heat risks in HERZ, aligning with sustainable urban design principles [9,12].

4.4. Methodological Innovations and Limitations of This Study

This study advances the understanding of travel-related heat exposure through the integration of mobility data and machine learning, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the reliance on ride-hailing data (from DiDi) as a proxy for travel intensity introduces potential socioeconomic bias. Ride-hailing users typically skew toward younger, tech-savvy, and middle- to high-income individuals, which may underrepresent vulnerable populations such as the elderly, low-income groups, or those relying on walking, cycling, or traditional public transit. These groups could face higher heat exposure risks due to prolonged outdoor activities or limited access to air-conditioned transport. Although ride-hailing trips effectively capture hotspots of urban mobility in high-demand areas like commercial centers and transit hubs, this bias limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader population. Future research could mitigate this by incorporating more inclusive datasets, such as shared bicycle records or public transit smart card data, to examine heat exposure across diverse demographic segments, including variations by age, income, gender, and occupation.

Second, while measures were implemented to enhance the robustness of the XGBoost models—such as five-fold cross-validation, conservative hyperparameter tuning, and variable selection to address multicollinearity—potential overfitting risks persist, particularly in smaller subsets like HERZ. Future studies could incorporate spatial extensions of XGBoost or geospatial weighting to better account for these dependencies.

In summary, these limitations highlight opportunities for refinement. Future work should prioritize inclusive mobility data, advanced spatial modeling, and longitudinal analyses to develop more equitable and robust strategies for mitigating urban heat risks.

4.5. Policy Implications and Future Directions

The findings of this study have important implications for urban planning and policy-making in the context of climate change. The identification of HERZ highlights the need for targeted interventions in high-risk areas, particularly those with high population density and limited green space. Policymakers should prioritize the development of green infrastructure, such as urban parks and tree-lined streets, to mitigate heat exposure in these zones. Additionally, the nonlinear relationship between built environment factors and heat exposure suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective. Instead, adaptive strategies that account for local conditions and the specific needs of vulnerable populations are essential.

The study also underscores the importance of integrating mobility data into urban heat risk assessments. By understanding how travel behaviors contribute to heat exposure, cities can design more resilient transportation systems that reduce thermal stress for residents. For example, improving access to shaded walkways or air-conditioned public transit could help mitigate exposure during heatwaves.

Future research should focus on expanding the temporal and spatial scope of the analysis to include seasonal variations and finer-scale resolutions. Incorporating additional data sources, such as pedestrian counts or wearable sensors, could provide a more comprehensive picture of heat exposure dynamics. Moreover, exploring the socioeconomic dimensions of heat vulnerability, including the impacts on different income groups and age cohorts, will be critical for developing equitable climate adaptation strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on ‘travel-related heat exposure’ by integrating ride-hailing travel data with LST to construct the THEI. High-exposure clusters, which are referred to as HERZ, were identified using spatial autocorrelation analysis. Furthermore, XGBoost nonlinear regression models were employed to analyze the effects of built environment factors across the entire study area and the HERZ subset. Both models demonstrated strong explanatory power, with R2 values of 0.72 and 0.63. Two sets of PDPs were constructed to support the interpretation of nonlinear mechanisms, revealing the marginal effects and structural pathways of the influencing variables. The main conclusions are presented as follows:

- (1)

- At the city-wide scale, intersection density (InS), ratio of floor area (RAF), and the distribution of subway and bus stations (SBS) emerged as the dominant variables influencing travel-related heat exposure. These results reflect the structural pathway of “dense morphology–high accessibility–intensified activity” underlying urban heat exposure. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) consistently showed a significant negative effect, confirming the critical regulatory function of urban green spaces in mitigating thermal risks.

- (2)

- In HERZ areas, the model results reveal substantial differences. Population density (Pop), housing price (HP), and road density (RD) became more influential than traditional morphological factors. This suggests that in high-risk spatial zones, the coupled mechanism of “population concentration–socioeconomic intensity–transportation facilities” becomes the dominant driver of exposure variation.

- (3)

- Across spatial scales, the formation mechanisms of travel-related heat exposure (THEI) exhibited clear divergence. At the city-wide level, transportation accessibility and morphological features such as intersection density and floor area ratio were the primary drivers, emphasizing the role of urban form and infrastructure layout. In contrast, within high-exposure risk zones, indicators of demographic aggregation and economic centrality—particularly population density, housing price, and road density—played a more dominant role, suggesting a shift from morphology-driven to activity-driven thermal dynamics in densely populated urban cores.

- (4)

- The PDP results further reveal the nonlinear characteristics and threshold effects of key variables across different scales. Socioeconomic variables such as housing price (HP) and community age (Age) exhibited greater variability in local models, suggesting that travel-related heat exposure risk is closely associated with spatial inequality.

- (5)

- The improvement of the NDVI plays a crucial role in reducing heat exposure risk at both city-wide and local scales. Therefore, enhancing the NDVI through green infrastructure development in areas with high population concentration and commercial intensity is an effective strategy to alleviate heat exposure in vulnerable urban zones.

In conclusion, this study methodologically proposes an integrated framework for assessing “travel-related heat exposure” by combining travel mobility data with remote sensing. It introduces innovations in metric construction, risk identification, and nonlinear mechanism interpretation. The findings reveal a structural shift in exposure drivers between city-wide and high-risk scales, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding the spatial heterogeneity of urban thermal risks and offering practical references for differentiated strategies in thermal environment planning, green infrastructure deployment, and equitable climate-resilient urban governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yue Zhang; methodology, Yue Zhang and Xiaojiang Xia; software, Yue Zhang and Ling Jian; validation, Yue Zhang and Yang Zhang; formal analysis, Yue Zhang; data curation; writing—original Yue Zhang; writing—review and editing Yang Zhang; supervision, Xiaojiang Xia. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was made possible by the generous financial support from a number of organizations. We gratefully acknowledge the backing from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42501258 and 52408053), as well as the Ministry of Education of China, through its General Research on Humanities and Social Sciences (Grant No. 22YJC760121) and the Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences (Grant No. 22YJC760077). We would also like to thank the Sichuan Provincial Social Science Foundation Commissioned Project for their support of our work on Driving Mechanisms and Implementation Paths for Urban-Rural Industrial Integration in the Western Chengdu Region (Grant No. SCJJ25RKX085). The insights and resources provided by these grants were instrumental in the completion of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are currently in use for ongoing and future research. Consequently, they are not publicly available at this time. Requests for data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Correlation Table of Factor.

Table A1.

Correlation Table of Factor.

| Age | HP | Ac | EP | Sh | Co | At | RD | LUM | SBS | InS | RAF | BD | SBLD | Pop | NDVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.03 | −0.28 |

| HP | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.10 | −0.32 | |

| Ac | 1.00 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.05 | −0.25 | ||

| EP | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.01 | −0.07 | |||

| Sh | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.04 | −0.23 | ||||

| Co | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.04 | −0.23 | |||||

| At | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.02 | −0.11 | ||||||

| RD | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.10 | −0.37 | |||||||

| LUM | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.06 | −0.34 | ||||||||

| SBS | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.05 | −0.28 | |||||||||

| InS | 1.00 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.05 | −0.22 | ||||||||||

| RAF | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.05 | −0.21 | |||||||||||

| BD | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.09 | −0.39 | ||||||||||||

| SBLD | 1.00 | 0.06 | −0.31 | |||||||||||||

| Pop | 1.00 | 0.13 | ||||||||||||||

| NDVI | 1.00 |

References

- Heaviside, C.; Macintyre, H.; Vardoulakis, S. The urban heat island: Implications for health in a changing environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Icaza, L.E.; Neht, A.; Klavins, M.; Morgan, E.A. Coping with the impacts of urban heat islands: A literature-based study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.K.; Richerzhagen, C.; Garnett, S.T. Human mobility intentions in response to heat in urban South East Asia. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 57, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wilhelmi, O.V.; Uejio, C. Assessment of heat exposure in cities: Combining the dynamics of temperature and population. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, M.D.; Teyton, A.; Jankowska, M.M.; Carrasco-Escobar, G.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Barja-Ingaruca, A.; Benmarhnia, T. Is home where the heat is? Comparing residence-based vs. mobility-based heat exposure. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, N.; Lee, J.K.W. Personal assessment of urban heat exposure: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Recent progress on urban overheating and heat island research. Integrated assessment of the energy, environmental, vulnerability and health impact. Synergies with the global climate change. Energy Build. 2020, 207, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Mishra, D.R.; Grundstein, A.; Ramaswamy, L.; Tonekaboni, N.H.; Dowd, J. DTEx: A dynamic urban thermal exposure index based on human mobility patterns. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, N.; Krayenhoff, E.S.; Bechtel, B.; Hondula, D.M.; Paolini, R.; Vanos, J.; Cheung, T.; Chow, W.T.L.; de Dear, R.; Jay, O.; et al. Integrated assessment of urban overheating impacts on human life. Earth Future 2022, 10, e2022EF002682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Mostafavi, A. The emergence of urban heat traps and human mobility in 20 US cities. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Middel, A.; Turner, V.K.; Liu, D.; Mallen, E. Unveiling nonlinear effects of built environment attributes on urban heat resilience using interpretable machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 112, 105657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jang, S.; Kim, K.B. Impact of urban microclimate on walking volume by street type and heat-vulnerable age groups. Urban. Clim. 2023, 47, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chester, M.V.; Middel, A.; Vanos, J.K.; Hernandez-Cortes, D.; Buo, I.; Hondula, D.M. Effectiveness of travel behavior and infrastructure change to mitigate heat exposure. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1129388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, J.; Hondula, D.M.; Vaidyanathan, R. Extreme heat reduces and reshapes urban mobility. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.03978v2. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.03978 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yin, C.; Yan, J.; Yuan, M.; Tian, G.; Wen, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, L. How does built environment affect the urban heat island effect? A systematic framework integrating land use, building form, and road network. Environ. Dev. Sustain 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Khan, A.; Anand, P.; Sen, J. Understanding the synergy between heat waves and the built environment: A three-decade systematic review informing policies for mitigating urban heat island in cities. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Fan, C.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, X. Assessing the impact of land use changes on urban heat risk under different development scenarios: A case study of Guangzhou in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106532. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221067072500407X (accessed on 17 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.E.; O’Neill, M.S.; Gronlund, C.J.; Brines, S.J.; Brown, D.G.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Schwartz, J. Mapping community determinants of heat vulnerability. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakinyo, T.E.; Obe, O.B.; Mills, G.; Adegun, O.B. The impact of hazard indicator selection on urban heat risk assessment: Evidence from Two Sub-Saharan African Cities. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Santamouris, M.; Lu, S. Assessing spatial inequities of thermal environment and blue-green intervention for vulnerable populations in dense urban areas. Urban Clim. 2024, 59, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noland, R.B. Variation in ride-hailing trips in Chengdu, China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 90, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Rong, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Measuring the potential substitution effect of ride-hailing travel on public transport and its influencing factors: A case study of Chengdu. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R.; Lin, Y. Exploring the spatiotemporal associations between ride-hailing demand, visual walkability, and the built environment: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirachini, A. Ride-hailing, travel behaviour and sustainable mobility: An international review. Transportation 2020, 47, 1603–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Thakuriah, P.; Ampountolas, K. Short-term prediction of demand for ride-hailing services: A deep learning approach. J. Big Data Anal. Transp. 2021, 3, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Fan, J. Revealing the influence mechanism of urban built environment on online car-hailing travel. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 3888800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresselassie, M.; Michalek, J.; Nock, D.; Harper, C. Analyzing disparities in app-hailed travel during extreme heat in New York City. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2025, 142, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Z. Quantifying the impact of weather on ride-hailing ridership: Evidence from Haikou, China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 22, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Cui, J.; Lu, Y.; Yang, L. Resilience of ride-hailing services in response to air pollution and its association with built-environment and socioeconomic characteristics. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 120, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Horton, R.M.; Kinney, P.L. Projections of seasonal patterns in temperature-related deaths for Manhattan, New York. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Mostafavi, A. Beyond residence: A mobility-based approach for improved evaluation of human exposure to environmental hazards. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 15511–15522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.E.; Hoffmann, P.; Scheffran, J.; Rühe, S.; Fischereit, J. An agent-based modeling framework for simulating human exposure to environmental stresses in urban areas. Urban. Sci. 2018, 2, 36. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2413-8851/2/2/36 (accessed on 17 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Huang, C.; Lv, Y.-S.; Ma, S.-X.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, E.Y. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure, oxidative potential in dust, and their relationships to oxidative stress in human body: A case study in the indoor environment of Guangzhou, South China. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaninno, N.; Basu, R.; Hosseini, M.; Alhassan, A.; Liu, L.; Sevtsuk, A. A sidewalk-level urban heat risk assessment framework using pedestrian mobility and urban microclimate modeling. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 52, 1071–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Zhou, L.; Park, J.; Baig, F.; Wang, S. Mapping dynamic human sentiments of heat exposure with location-based social media data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 1291–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, W. Dynamic estimation of urban heat exposure for outdoor jogging: Combining individual trajectory and mean radiant temperature. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, P. The Mortality Effects of Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations by Urbanicity in North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Yang, D.; Qie, K.; Wang, J. Analysis of land surface temperature drivers in Beijing’s central urban area across multiple spatial scales: An explainable ensemble learning approach. Energy Build. 2025, 338, 115704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).