The Unseen—An Investigative Analysis of Thematic and Spatial Coverage of News on the Ongoing Refugee Crisis in West Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background & Related Work

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

4. Findings

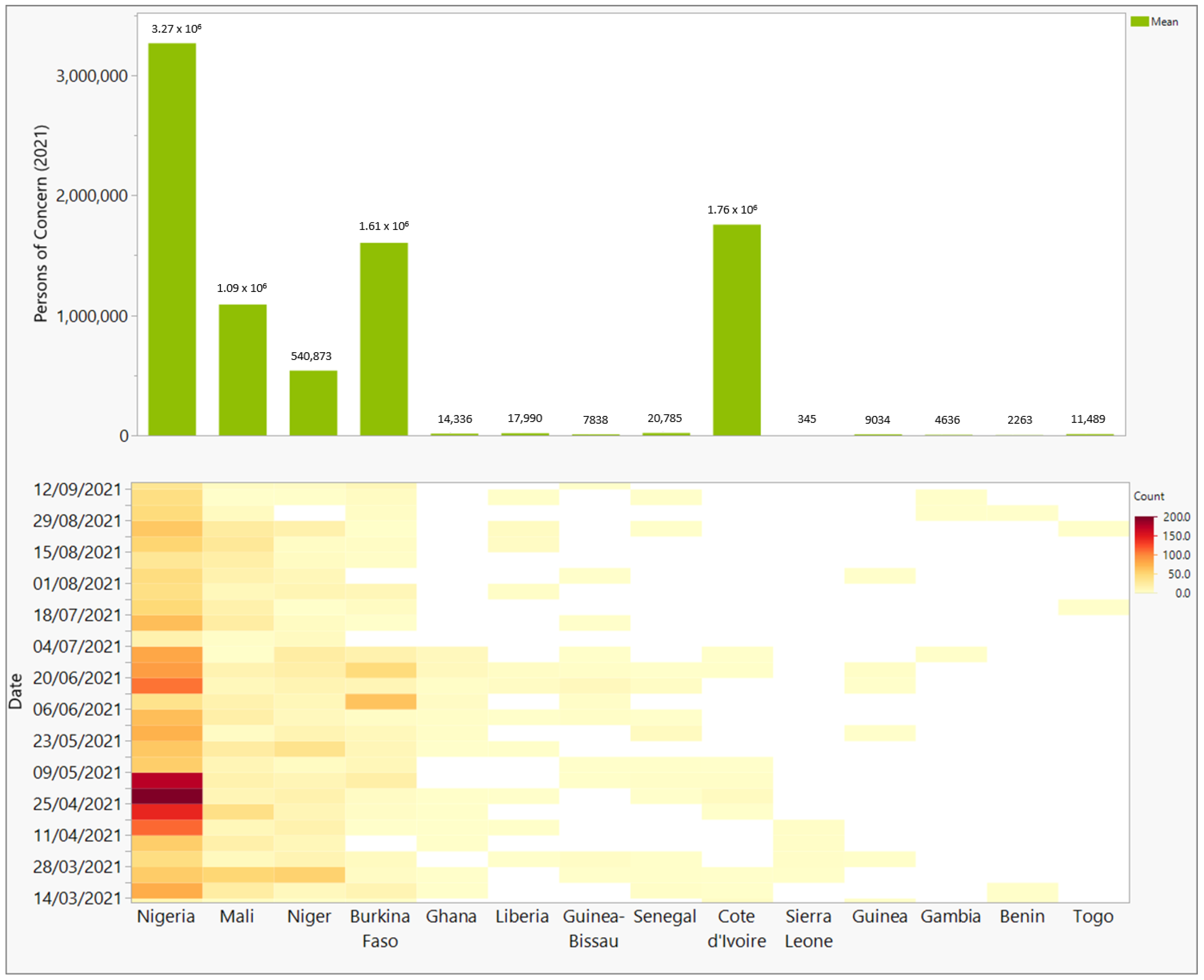

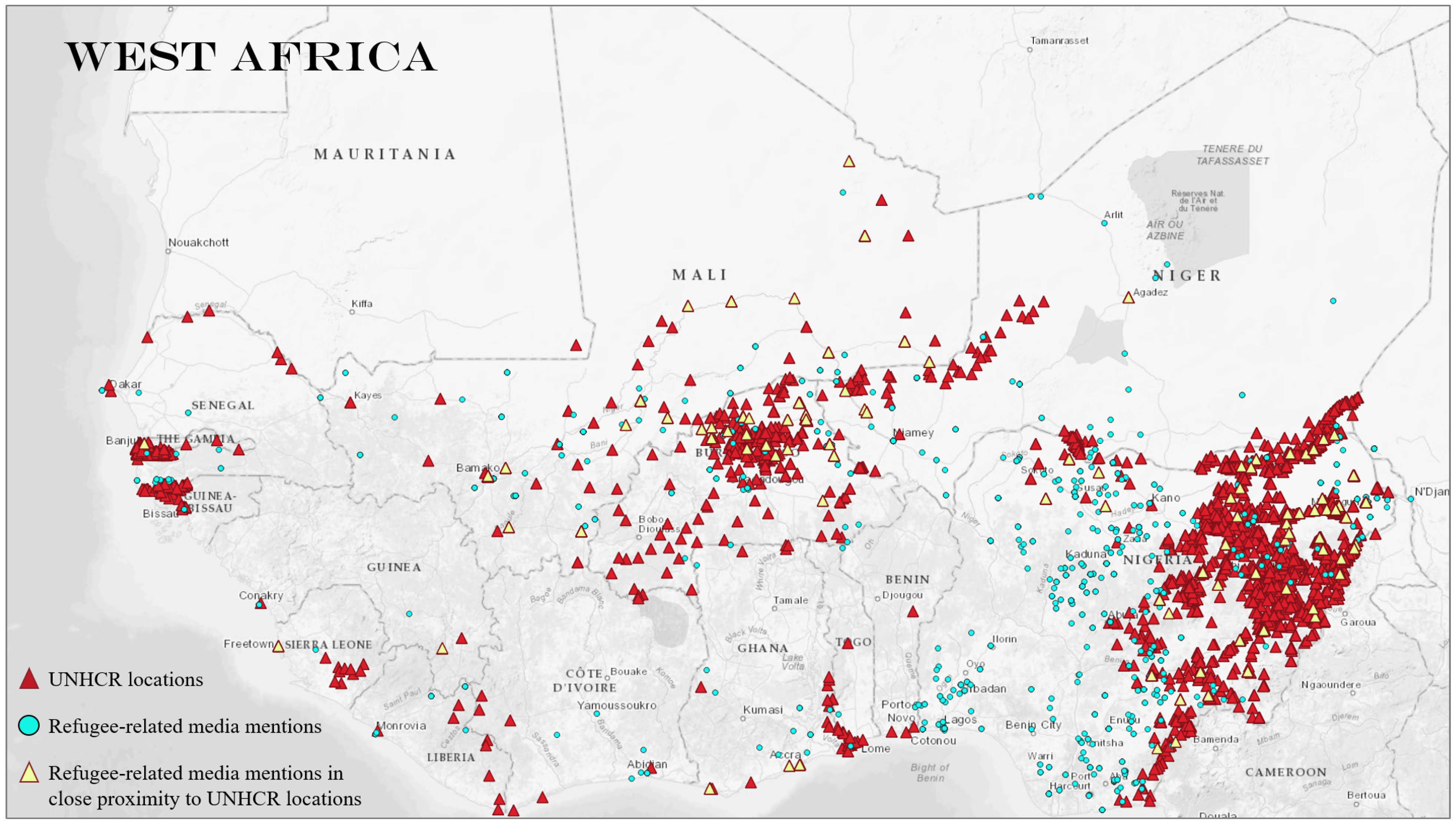

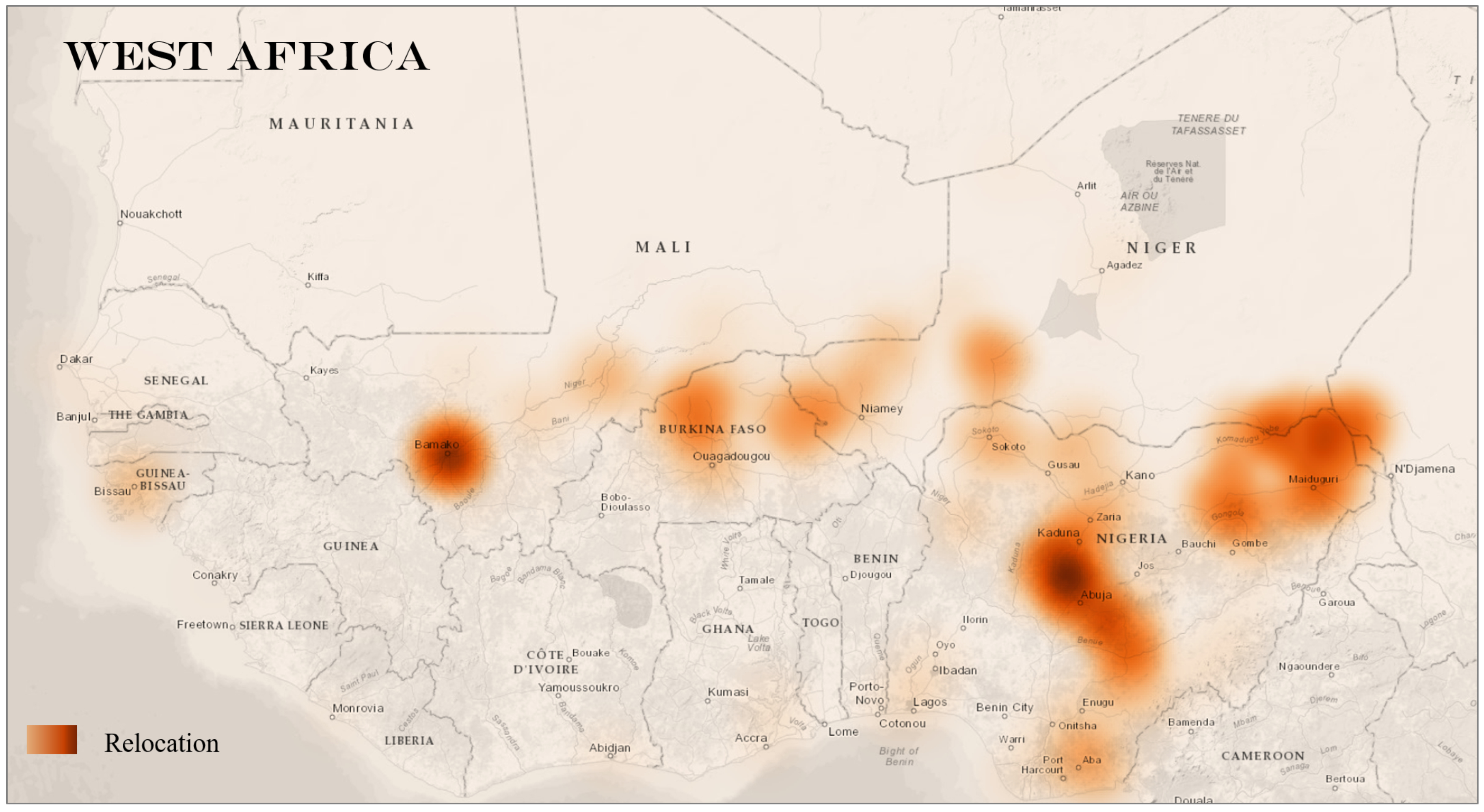

4.1. News Coverage of the Refugee Crisis in West Africa in Spatial Terms

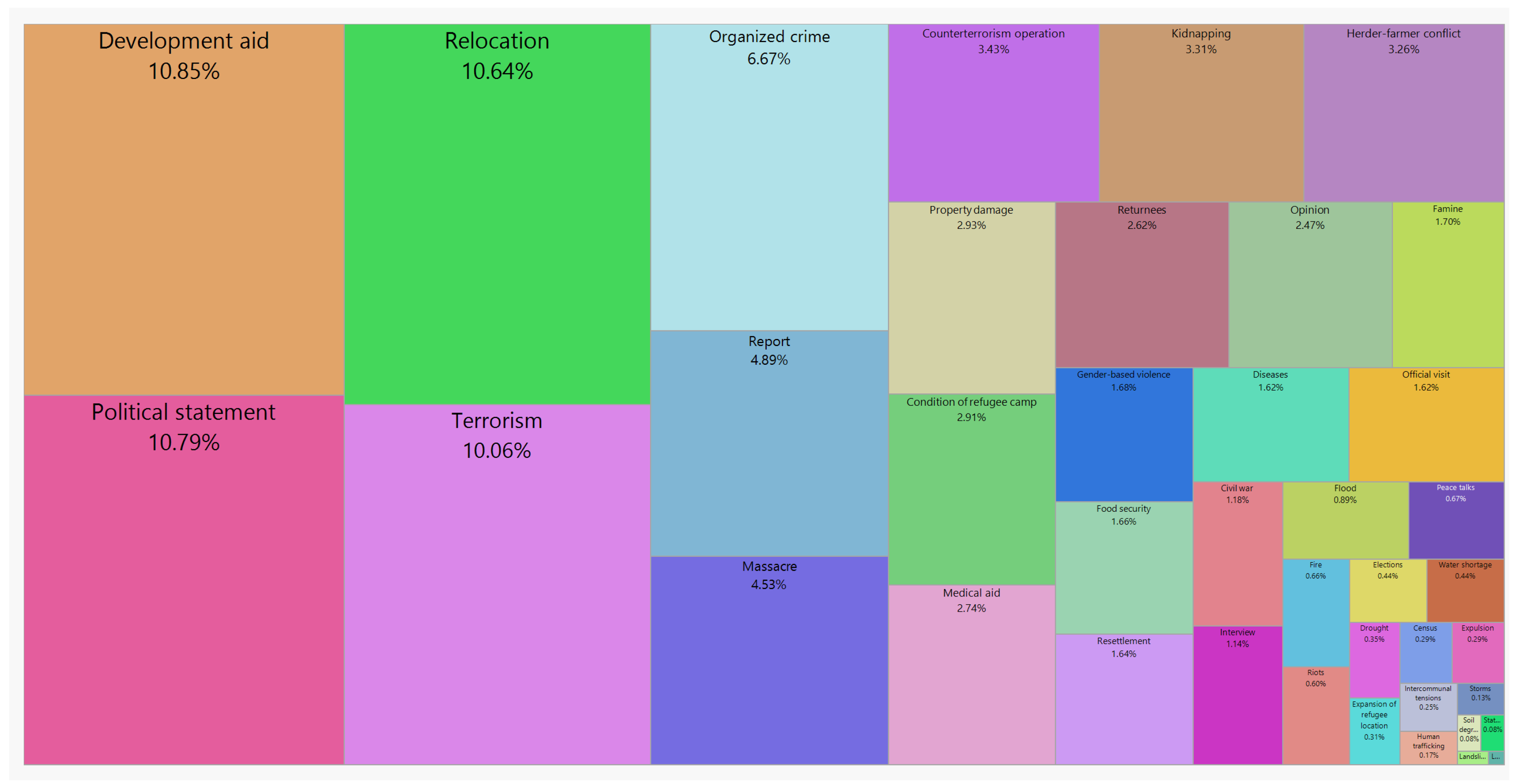

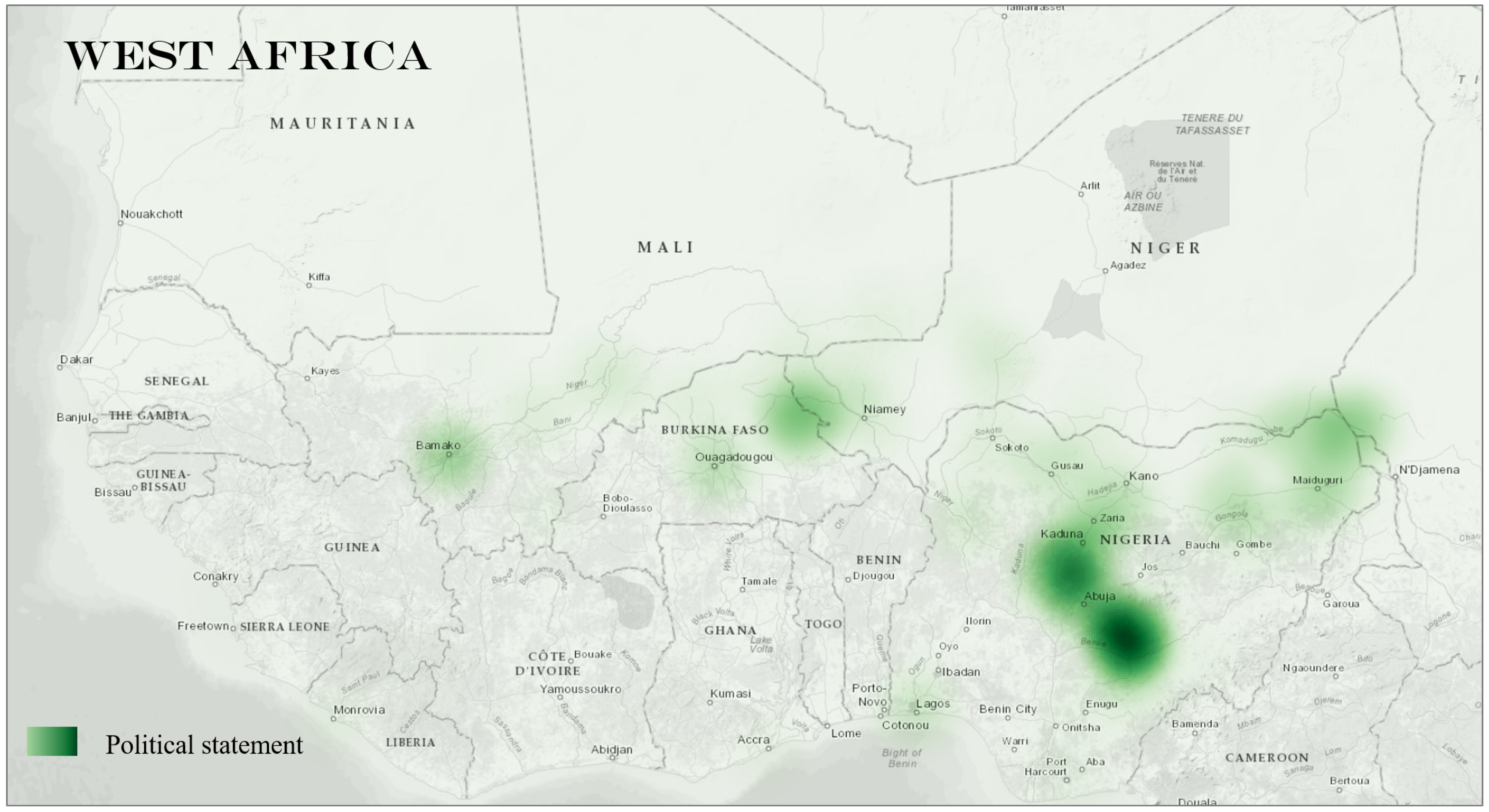

4.2. News Coverage of the Refugee Crisis in West Africa with Respect to Content

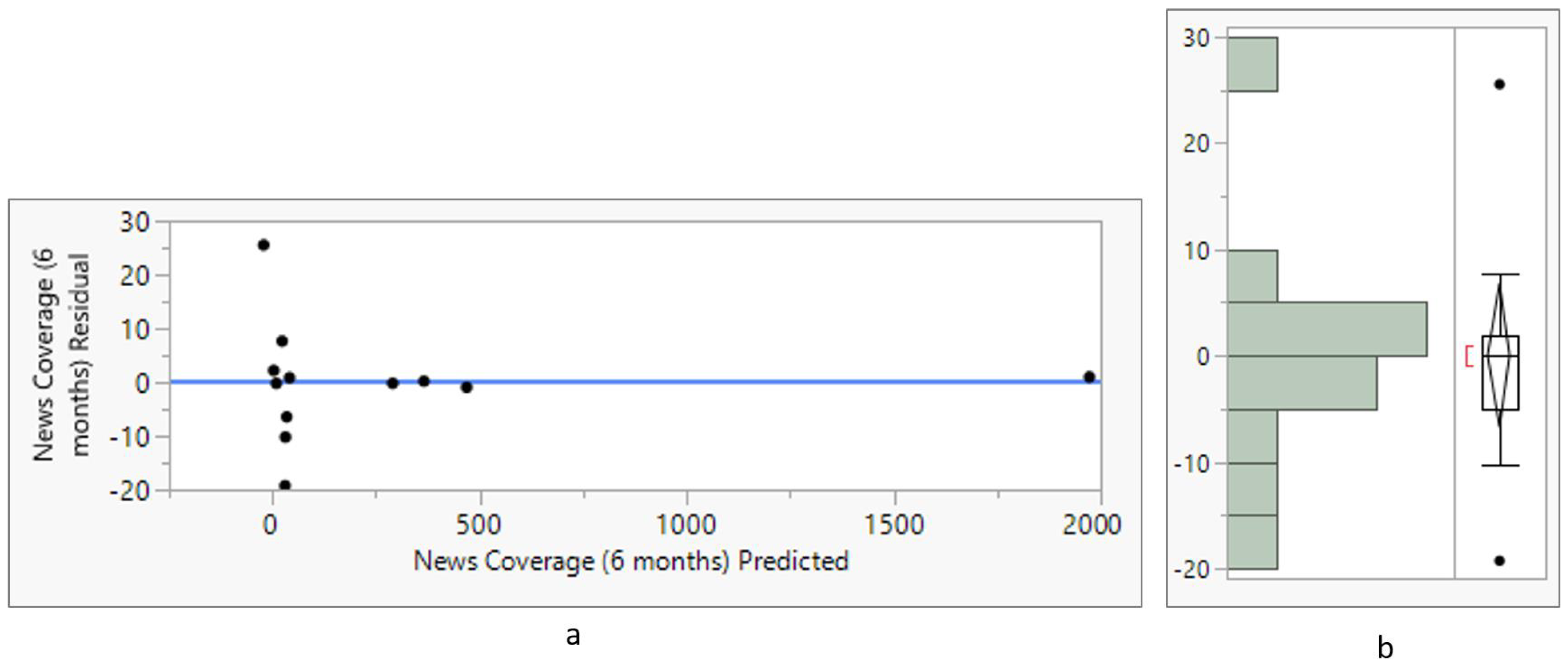

4.3. Systemic Determinants of News Coverage for the Refugee Crisis in West Africa

5. Discussion and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trémolières, M.; Walther, O.; Radil, S. The Geography of Conflict in North and West Africa; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Refugee Council. The World’s Most Neglected Displacement Crises in 2019; NRC: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Refugee Council. The World’s Most Neglected Displacement Crises in 2020; NRC: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Refugee Council. The World’s Most Neglected Displacement Crises in 2021; NRC: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Data. 2022. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Parekh, S. Refugees and the Ethics of Forced Displacement; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, E. Profiling information needs and behaviour of Syrian refugees displaced to Egypt: An exploratory study. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2018, 119, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D.J.; Apollo, J.O. Internal displacement, internal migration, and refugee flows: Connecting the dots. Refug. Surv. Q. 2020, 39, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, M.; Worbis, S.; Sapena, M.; Taubenböck, H. A structural catalogue of the settlement morphology in refugee and IDP camps. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2023, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelizari, P.; Spröhnle, K.; Geiß, C.; Schoepfer, E.; Plank, S.; Taubenböck, H. Multi-sensor feature fusion for very high spatial resolution built-up area extraction in temporary settlements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenböck, H.; Kraff, N.; Wurm, M. The morphology of the Arrival City-A global categorization based on literature surveys and remotely sensed data. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 92, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Covaci, R.N. Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania. Identities 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Covaci, R.N.; Jucu, I.S. Articulating ‘otherness’ within multiethnic rural neighbourhoods: Encounters between Roma and non-Roma in an East-Central European borderland. Identities 2023, 30, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.K.; Glen, C. From empathy to action: Can enhancing host-society children’s empathy promote positive attitudes and prosocial behaviour toward refugees? J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 30, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rîșteiu, N.T.; Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Contesting post-communist economic development: Gold extraction, local community, and rural decline in Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2022, 63, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vãran, C.; Creţan, R. Place and the spatial politics of intergenerational remembrance of the Iron Gates displacements in Romania, 1966–1972. Area 2018, 50, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Zaborowski, R. Media Coverage of the “Refugee Crisis”: A Cross-European Perspective; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, G.R.; Carstensen, N.; Høyen, K. Humanitarian crises: What determines the level of emergency assistance? Media coverage, donor interests and the aid business. Disasters 2003, 27, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.R. News framing and media legitimacy: An exploratory study of the media coverage of the refugee crisis in the European Union. Commun. Soc. 2017, 30, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.D. Systemic determinants of international news coverage: A comparison of 38 countries. J. Commun. 2000, 50, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantti, M. Crisis and disaster coverage. Int. Encycl. J. Stud. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, R.G.; Gordon, A. Foreign news content in Israeli and US newspapers. J. Q. 1974, 51, 639–644. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J.; Ruge, M.H. The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. J. Peace Res. 1965, 2, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupree, J.D. International communication: View from ‘a window on the world’. Gazette (Leiden Netherlands) 1971, 17, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, K.E. Four types of tables. J. Commun. 1977, 27, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, T.J., Jr. Determinants of foreign coverage in US newspapers. In Foreign News and the New World Information Order; The Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1984; pp. 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.Y. Between global and local: The glocalization of online news coverage on the trans-regional crisis of SARS. Asian J. Commun. 2005, 15, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, K.; Van Aelst, P. Did the European migrant crisis change news coverage of immigration? A longitudinal analysis of immigration television news and the actors speaking in it. Mass Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Lynn, N. When the news takes sides: Automated framing analysis of news coverage of the Rohingya crisis by the elite press from three countries. J. Stud. 2020, 21, 1284–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greussing, E.; Boomgaarden, H.G. Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 1749–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.K.; Gower, K.K. How do the news media frame crises? A content analysis of crisis news coverage. Public Relations Rev. 2009, 35, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, A.; Tolley, E. Deciding who’s legitimate: News media framing of immigrants and refugees. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki, L.; Zaborowski, R. Voice and community in the 2015 refugee crisis: A content analysis of news coverage in eight European countries. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2017, 79, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K. Measuring news bias: Russia’s official news agency ITAR-TASS’coverage of the Ukraine crisis. Eur. J. Commun. 2017, 32, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooten, L. Blind spots in human rights coverage: Framing violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar/Burma. Pop. Commun. 2015, 13, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inden, R. Orientalist constructions of India. Mod. Asian Stud. 1986, 20, 401–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, D. The Persian Gulf TV War; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Said, E.W. Orientalism (Reprint with a New Afterword); Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rügger, S.; Bohnet, H. The Ethnicity of Refugees (ER): A new dataset for understanding flight patterns. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2018, 35, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gineste, C.; Savun, B. Introducing POSVAR: A dataset on refugee-related violence. J. Peace Res. 2019, 56, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, K.C. Geo-Refugee: A Refugee Location Dataset; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, K. Camp settlement and communal conflict in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Peace Res. 2019, 56, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, B.Z.; Van Den Hoek, J.; Alix-Garcia, J.; Svevo, G.; Franklin, G.B.; Katz, G. Global Refugee Atlas. 2021. Available online: https://hgis.uw.edu/refugee/index.html (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Ijeoma, E. The Refugee Project. 2015. Available online: https://www.therefugeeproject.org/#/2018 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Leetaru, K.; Schrodt, P.A. Gdelt: Global data on events, location, and tone, 1979–2012. In Proceedings of the ISA Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–6 April 2013; Volume 2, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D. The Worldwide Governance Indicators Project: Answering the Critics; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Volume 4149. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues 1. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR Glossary. 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/564da0ec1.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Partey, S.T.; Zougmore, R.B.; Ramasamy, J. Drought in West Africa; Special Report on Drought 2021—Case Studies; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CAPRECON. Assessment of Trafficking Risks in Internally Displaced Persons Camps in North-East Nigeria; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.E. Moving Stories. International Review of How Media Cover Migration; Ethical Journalism Network: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fengler, S.; Lengauer, M.; Zappe, A.C.E. Reporting on Migrants and Refugees. In A Handbook for Journalism Educators; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht, A.; Esser, F. The push to popularize politics: Understanding the audience-friendly packaging of political news in six media systems since the 1960s. J. Stud. 2016, 17, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GDELT | WARRe | UNHCR | |

| Spatial | Locations mentioned in the news media in the context of the refugee crisis. These locations are extracted using GDELT’s own NLP methods and geocoded | Use GDELT’s format of locations, and manually identify the news articles that have more than one location mentioned, code them with parent/child IDs | contains the official records of locations for refugee-settlements |

| Thematic | NLP methods are used to automatically classify news articles into a class “Refugees” | Manually examine the news articles and identify the various themes reported on in the context of the “Refugees” | none |

| No. | Thematic Class | Thematic Class Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Census | An official count or survey of a population conducted in the refugee camp or host country |

| 2 | Civil war | A violent conflict between organized non-state actors and the state that forces people’s displacement |

| 3 | Condition of refugee camp | Infrastructure of the refugee camp/shelter and inhabitants of the refugee camp |

| 4 | Counterterrorism operation | The practice and strategy that government/militia use to combat or prevent terrorism |

| 5 | Development aid | An aid given by governments/agencies to support the economic, environmental, social, and political development of West African countries in terms of refugees/IDPs. Includes articles that talk about people/organization/stakeholders seeking help for refugees |

| 6 | Diseases | A cause of forced migration that deteriorates the health of people and/or animals, e.g., measles, coronavirus |

| 7 | Drought | Deficiency of precipitation over an extended period of time, resulting in a water shortage as a contributing factor for displacement |

| 8 | Elections | Process in which people vote to choose a person or group of people to hold an official position |

| 9 | Expansion of refugee location | Increasing the size of the refugee camp |

| 10 | Expulsion | The action that a government exerts on the inhabitants to abandon a place |

| 11 | Famine | The extreme scarcity of food that drives individuals to look for another place to settle down |

| 12 | Fire | Burns and/or explosions that lead to the displacement of the inhabitants of the area |

| 13 | Flood | An overflow of a large amount of water beyond its normal limits forcing the settlers to leave the territory |

| 14 | Food security | The state of having reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food |

| 15 | Gender-based violence | Any act of violence perpetrated against a person’s will based on gender norms and unequal power relationships |

| 16 | Herder-farmer conflict | Also called Fulani Herdsmen terrorism, involved disputes over land resources between mostly Muslim Fulani herders and mostly Christian farmers across Nigeria |

| 17 | Human trafficking | The act of transporting or coercing civilians/refugees/IDPs in order to benefit from their work or service |

| 18 | Independence | Freedom to make laws or decisions without being governed or controlled by another country, organization, etc. |

| 19 | Intercommunal tensions | Arguments or encounters between previous residents and new arrivals or vice versa |

| 20 | Interview | A meeting in which someone answers questions related to refugees/IDPs |

| 21 | Insect plague | When insects or parasites invade an area depleting resources and food |

| 22 | Kidnapping | The action of abducting someone and holding them captive |

| 23 | LGBTQ | Refugee news concerning the LGBTQ community |

| 24 | Landslide | A collapse of a mass of earth or rock from a mountain or cliff that causes forced displacement |

| 25 | Massacre | The indiscriminate and brutal slaughter of many people |

| 26 | Medical aid | An aid given by governments or agencies to support the West African countries in terms of health care |

| 27 | Official visit | A formal visit by a country representative at a refugee camp or shelter |

| 28 | Opinion | An article that expresses the opinion of its editors on refugee-related issues. It also includes topics such as religion, law, and use of natural resources (oil, forest) |

| 29 | Organized crime | Any behavior, activity, or event that is punishable by law, e.g., assault, murder, banditry, armed attacks, and non-state armed groups |

| 30 | Peace talks | A conference or series of discussions aimed at ending hostilities in West Africa |

| 31 | Political statement | A newspaper article describing what politicians/agencies have said about refugees in West Africa |

| 32 | Property damage | A damage or destruction of personal property, e.g., camp facilities, public places, NGO infrastructure |

| 33 | Relocation | As a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence or human rights violations a person from a country moves or wants to move to any other one, e.g., from a West African country to Europe, from a West African country to another one in Africa, from a country in Africa to West Africa, asylum seekers |

| 34 | Report | An article that gives information about issues, events, or findings in West Africa in the context of refugees |

| 35 | Resettlement | A human movement that is not connected to force, e.g., drought |

| 36 | Returnees | Refugees/IDPs person who escape from a country and return to their previous place of residence |

| 37 | Riots | A violent public disturbance that leads to the movement of people because of the destruction/insecurity generated |

| 38 | Soil degradation | A change in the state of soil quality that causes a decrease in the ecosystem’s capacity to provide goods and services and drives forced migration |

| 39 | Stateless | A person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law |

| 40 | Storms | A violent disturbance of the atmosphere with strong winds and rain that force people to move from their place of residence. It includes rain storms, thunderstorms and wind storms |

| 41 | Terrorism | The use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims as a cause of forced displacement |

| 42 | Water shortage | The lack of fresh water resources to meet the standard water demand in a city/refugee camp |

| ID | Location | State | Source URL | Date | Parent_ID | Thematic Classes | News_ Duplicate | Loc_ Duplicate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bamako | Mali | http://s.dlr.de/WCPIt | 12 March 2021 | 1 | Development aid/Gender-based violence/ Relocation | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Bamako | Mali | http://s.dlr.de/WCPIt | 12 March 2021 | 1 | Development aid/Gender-based violence/ Relocation | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | Kaduna | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/fy5F6 | 12 March 2021 | 4 | Organized crime/Kidnapping/Property damage/ Development aid | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | http://s.dlr.de/WCPIt | 12 March 2021 | 1 | Development aid/Gender-based violence/ Relocation | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | http://s.dlr.de/WCPIt | 12 March 2021 | 1 | Development aid/Gender-based violence/ Relocation | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | http://s.dlr.de/fiOQk | 12 March 2021 | 10 | Development aid | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | http://s.dlr.de/ELdqe | 12 March 2021 | 11 | Development aid/Condition of refugee camp/ Political statement | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Djibo | Burkina Faso | http://s.dlr.de/GB64v | 12 March 2021 | 12 | Official visit/Returnees/Development aid/ Relocation | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | Birnin Gwari | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/fy5F6 | 12 March 2021 | 4 | Organized crime/Kidnapping/Property damage/ Development aid | 0 | 1 |

| 14 | Abuja | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/88EIg | 12 March 2021 | 14 | Interview | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Abuja | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/X2xOQ | 12 March 2021 | 15 | Interview | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Lake Chad | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/sC640 | 12 March 2021 | 20 | Terrorism | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | Lake Chad | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/jnMKE | 12 March 2021 | 21 | Elections/Opinion | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | Tudun Wada | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/fy5F6 | 12 March 2021 | 4 | Organized crime/Kidnapping/Property damage/ Development aid | 0 | 1 |

| 27 | Birnin Yero | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/fy5F6 | 12 March 2021 | 4 | Organized crime/Kidnapping/Property damage/ Development aid | 0 | 1 |

| 28 | Igabi | Nigeria | http://s.dlr.de/fy5F6 | 12 March 2021 | 4 | Organized crime/Kidnapping/Property damage/ Development aid | 0 | 1 |

| 29 | Koulouba | Mali | http://s.dlr.de/WCPIt | 12 March 2021 | 1 | Development aid/Gender-based violence/ Relocation | 1 | 1 |

| 30 | Sanmatenga | Burkina Faso | http://s.dlr.de/GB64v | 12 March 2021 | 12 | Official visit/Returnees/Development aid/ Relocation | 0 | 1 |

| 32 | Sansani | Niger | http://s.dlr.de/FSzMT | 12 March 2021 | 32 | Kidnapping/Terrorism | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | Souleymane | Mali | http://s.dlr.de/GB64v | 12 March 2021 | 12 | Official visit/Returnees/Development aid/ Relocation | 0 | 1 |

| Country | n | n/Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 1974 | 0.60128 | 60.13 |

| Mali | 468 | 0.14255 | 14.26 |

| Niger | 366 | 0.11148 | 11.15 |

| Burkina Faso | 290 | 0.08833 | 8.83 |

| Ghana | 42 | 0.01279 | 1.28 |

| Liberia | 32 | 0.00975 | 0.97 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 31 | 0.00944 | 0.94 |

| Senegal | 28 | 0.00853 | 0.85 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 21 | 0.00640 | 0.64 |

| Sierra Leone | 11 | 0.00335 | 0.34 |

| Guinea | 9 | 0.00274 | 0.27 |

| Gambia | 5 | 0.00152 | 0.15 |

| Benin | 4 | 0.00122 | 0.12 |

| Togo | 2 | 0.00061 | 0.06 |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Population (2020) | The number of inhabitants of a country in a given year |

| Geographic size (km²) | The total area of land governed by a country |

| Annual GDP ($ - Mil.) | The total market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given year, is known as the annual Gross Domestic Product |

| GDP per Capita ($) | The sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy, plus any product taxes not included in the valuation of output, divided by mid-year population |

| Refugee population | Persons who are outside their country of origin for reasons of feared persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or other circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order, and as a result, require international protection |

| Fulani Population | The number of inhabitants that belong to one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa- the Fula ethnic group. |

| International migrant stock | The total number of international migrants present in a given country at a particular point in time |

| Political stability and the absence of violence/ terrorism | Measures perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically-motivated violence, including terrorism. |

| Control of corruption | Reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. |

| Regulatory quality | Reflects perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. |

| Voice and accountability | Reflects perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. |

| Government effectiveness | Reflects perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. |

| Rule of law | Reflects perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. |

| Covariate | Mean | Standard- Deviation | Correlation- Coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 28,313,158 | 51,982,771 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Geographic size | 364,905.4 | 438,759.7 | 0.59 | 0.0246 |

| Annual GDP ($, Mil.) | 48,791.93 | 111,470.7 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| GDP per Capita ($) | 1180.93 | 619.213 | 0.32 | 0.2682 |

| Refugee population | 33,265.86 | 66,019.87 | 0.37 | 0.1923 |

| Fula population | 2,476,282 | 3,729,209 | 0.87 | 0.0002 |

| Political stability | −0.796 | 0.769 | −0.61 | 0.0199 |

| Control of corruption | −0.564 | 0.424 | −0.36 | 0.1992 |

| Regulatory quality | −0.63 | 0.346 | −0.26 | 0.3717 |

| Persons of Concern | 598,904.8 | 1,025,295 | 0.81 | 0.0009 |

| First Model Run | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of Fit | ||||

| RSquare | 0.99966 | |||

| RSquare Adj | 0.998131 | |||

| Root Mean Square Error | 24.24293 | |||

| Mean of Response | 270.75 | |||

| Observations (or Sum Wgts) | 12 | |||

| Analysis of Variance | ||||

| Source | DF | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Ratio |

| Model | 9 | 3,457,106.8 | 384,123 | 653.582 |

| Error | 2 | 1175.4 | 588 | Prob > F |

| C. Total | 11 | 3,458,282.3 | 0.0015 | |

| Parameter Estimates | ||||

| Term | Estimate | Std Error | t Ratio | Prob > t |

| Intercept | 1274.7912 | 227.0906 | 5.61 | 0.0303 |

| Population | −0.00003256 | 0.000009167 | −3.55 | 0.0709 |

| Geographic size (Sq.Km.) | −0.000021 | 0.00006711 | −0.31 | 0.784 |

| Annual GDP ($,Mil.) | 0.0205875 | 0.004289 | 4.8 | 0.0408 |

| GDP per Capita ($) | −0.749812 | 0.109157 | −6.87 | 0.0205 |

| Refugee population | 0.0007415 | 0.000359 | 2.07 | 0.1749 |

| Index: Political Stability- No violence | −194.5868 | 37.60319 | −5.17 | 0.0354 |

| Index: Control of corruption | −363.6182 | 105.2281 | −3.46 | 0.0745 |

| Index: Regulatory quality | 1014.8891 | 211.6453 | 4.8 | 0.0408 |

| Fula population | 0.000023268 | 0.00007683 | 3.03 | 0.0939 |

| Second Model Run | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of Fit | ||||

| RSquare | 0.999643 | |||

| RSquare Adj | 0.998693 | |||

| Root Mean Square Error | 20.27289 | |||

| Mean of Response | 270.75 | |||

| Observations (or Sum Wgts) | 12 | |||

| Analysis of Variance | ||||

| Source | DF | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Ratio |

| Model | 8 | 3,457,049.3 | 432,131 | 1051.44 |

| Error | 3 | 1233 | 411 | Prob > F |

| C. Total | 11 | 3,458,282.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Parameter Estimates | ||||

| Term | Estimate | Std Error | t Ratio | Prob > t |

| Intercept | 1225.2212 | 136.0482 | 9.01 | 0.0029 |

| Population | −0.00003144 | 0.000007057 | −4.46 | 0.021 |

| Annual GDP ($,Mil.) | 0.0200171 | 0.003246 | 6.17 | 0.0086 |

| GDP per Capita ($) | −0.726707 | 0.067221 | −10.81 | 0.0017 |

| Refugee population | 0.0006636 | 0.000216 | 3.07 | 0.0547 |

| Index: Political Stability- No violence | −188.4586 | 26.84245 | −7.02 | 0.0059 |

| Index: Control of corruption | −339.616 | 60.23026 | −5.64 | 0.011 |

| Index: Regulatory quality | 964.23936 | 114.006 | 8.46 | 0.0035 |

| Fula population | 0.0000226 | 0.000006173 | 3.66 | 0.0352 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senaratne, H.; Mühlbauer, M.; Kiefl, R.; Cárdenas, A.; Prathapan, L.; Riedlinger, T.; Biewer, C.; Taubenböck, H. The Unseen—An Investigative Analysis of Thematic and Spatial Coverage of News on the Ongoing Refugee Crisis in West Africa. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12040175

Senaratne H, Mühlbauer M, Kiefl R, Cárdenas A, Prathapan L, Riedlinger T, Biewer C, Taubenböck H. The Unseen—An Investigative Analysis of Thematic and Spatial Coverage of News on the Ongoing Refugee Crisis in West Africa. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2023; 12(4):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12040175

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenaratne, Hansi, Martin Mühlbauer, Ralph Kiefl, Andrea Cárdenas, Lallu Prathapan, Torsten Riedlinger, Carolin Biewer, and Hannes Taubenböck. 2023. "The Unseen—An Investigative Analysis of Thematic and Spatial Coverage of News on the Ongoing Refugee Crisis in West Africa" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 12, no. 4: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12040175

APA StyleSenaratne, H., Mühlbauer, M., Kiefl, R., Cárdenas, A., Prathapan, L., Riedlinger, T., Biewer, C., & Taubenböck, H. (2023). The Unseen—An Investigative Analysis of Thematic and Spatial Coverage of News on the Ongoing Refugee Crisis in West Africa. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 12(4), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12040175