Abstract

This paper reviews recent developments in the emerging field of resilient robots and the related robots that share common concerns with them, such as self-reconfigurable robots. This paper addresses the identity of the resilient robots by distinguishing the concept of resilience from other similar concepts and summarizes the strategies used by robots to recover their original function. By illustrating some issues of current resilient robots in the design of control systems, physical architecture modules, and physical connection systems, this paper shows several of the possible solutions to facilitate the development of the new and improved robots with higher resilience. The conclusion outlines several directions for the future of this field.

1. Introduction

Biological systems have the ability to recover themselves from severe damage such as lost limbs by creating new compensatory behaviors. Although such properties would be desirable in robotic systems, most robotic systems tend to fail due to material degradation and/or unanticipated disturbances from the world environment. Many applications such as space exploration and rescue tasks in dangerous tasks often require self-recovery abilities and resilient robots are considered as one of the solutions.

The inspiration for the biological systems and the growing demand of recovery abilities is a great motivator for research in the field of resilient robots. Resilient robots are robots that can recover their original function after partial damage. Though the number of robots that are named “resilient robots” is small, we believe that the resilient robot does have its identity and is worth the special attention of the scientific community.

In fact, resilience is the property of each system itself, and any system is resilient, but the major difference is the degree of resilience as per the requirement of the application. For instance, the majority of the existing self-reconfigurable robots have relatively low resilience. This is because the reliable autonomous control for reconfiguration (software) and the associated mechanism design (hardware) are very challenging. These challenges also occur in other robotic systems. Particularly, most robots’ resilience is restricted due to slow technological developments in the areas of hardware prototypes, actuators, and communications, and thus the system may not recover its original function even if it suffers slight failures.

Considering the number of robots described in the literature, so far only a few of them focused on resilience. There are a large number of modular self-reconfigurable robots (MSRR) prototypes. A recent review of the hardware architecture of the MSRRs is referred to [1], and a review of self-reconfiguration algorithms is referred to [2]. However, most of the literature reviews concentrate on self-reconfiguration solutions, and no other publication presents a summary of mechanical design and the control systems from the viewpoint of resilience. An assessment of different solutions would provide developers with an evaluation of the solutions, and thus allow them to learn from the successes as well as the shortfalls from other research teams.

The aim of this paper is to compare and summarize the robotic systems with resilience and related robots to provide a comprehensive reference about existing technical solutions in terms of the design of control systems, physical architecture modules, and physical interfaces, and to facilitate the development of the new and improved robots. Although many robots have resilience, it is reasonable to acknowledge that some robots with a certain of recovery ability (e.g., a robot with a robust controller dealing with motor noise or a robot with backup modules) will not be recovered, as they do not belong to resilient robots. The concept of both resilience and resilient robot will be detailed in Section 2. The scope of this paper is limited to studying the hardware architectures and the associated control systems when physical damages occur; failures of software are excluded from this survey. Nevertheless, this documentation is intended to be a valuable source of information for engineers and scientists working on new solutions for higher resilience of physical systems.

The remaining part of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the distinction of the resilience concept from some other concepts that are closely related to the resilience concept is discussed, which thus gives the identity of the resilient robot. In Section 3, resilient robots, self-reconfigurable robots, and other related robots are reviewed. In Section 4, we present some principles for the design of resilient robots. There is a conclusion with a discussion of future directions in Section 5.

2. The Identity of Resilient Robots

2.1. Resilience and Resilient Robots

Resilience is associated with a system, and it is an ability of a system to recover its function due to partial damage of the system [3]. In different disciplines of systems, the resilience may be defined from different viewpoints. The resilience concept has been widely developed in sociology and ecology, and it is characterized as a property of the social and ecological system, which enables the system to absorb changes and persist [4]. The resilience concept in engineering has emerged only in recent years [5,6,7]. Hollnagel et al. [5] defined resilience as “the ability of an organization (system) to keep, or recover quickly to, a stable state, allowing it to continue operations during and after a major mishap or in the presence of continuous significant stresses.” Zhang and Lin [3] stated, “Hollnagel’s definition lacks a distinction of resilience from robustness” and defined resilience as “the ability of the system on how the system can still function to the desired level when the system suffers from a partial damage”.

The identity of a resilient robot depends on whether there is a unique challenge or problem with the concept of resilience, and thus a resilient robot. There are several concepts that are closely related to the concept of resilience, such as “self-healing”, “fault-tolerance”, “self-repairing”, “sustainability”, “reliability”, “dependability”, “survivability”, and “robustness”.

Self-healing is well known in biology [8]. When a biological cell encounters excessive stresses or stimuli, it may undergo adaptations to shift to a new state of the system to keep its original function (analogous to a robot: the robot changes its software or hardware). When there is no possible adaptive response, or a cell’s adaptive capability is exceeded, cell injuries may develop (analogous to a robot: physical damage occurs). Upon suffering a severe injury, the injured cells may die (analogous to a robot: the robot cannot recover its original function). Upon suffering a mild injury, an injured cell may “recover” to a normal state through a complicated chemical change (analogous to a robot: the robot recovers its original function by changing its physical system). For instance, amino acids can enable muscles to build up, repair, or regenerate. Even though our contemporary technology is not ready to interface with such a complex biological system [9], i.e., regeneratation of an identical part, we believe the recovery always involves reconfiguration and readjustment of some smaller elements in the cell. The concept of the resilient robot is inspired by biological self-healing, from both macro and micro viewpoints. However, it seems that most self-healing robots refer to a chemical reaction, which does not consider the reconfiguration and re-adjustment of robot components. For instance, the self-healing robot in [10] can grow skin back together without a catalyst. The self-repairing robot is more restricted to the repairing of damaged components: that is, to repair the damaged component with external resources. Compared with self-healing and self-repairing, the scope of recovery solutions for resilience is more general.

Fault tolerance is a classic notion in software engineering, and it is defined as the ability to deliver service in the presence of faults [11]. Here, fault refers to errors made at the phase of software development and/or errors in the system input at the phase of software operation [3]. Fault-tolerance also includes component damage. However, the recovery solutions of fault tolerance are usually based on the software development, and a classic approach to fault tolerance is to employ robust controller. Compared with fault tolerance, the solutions generated by a resilient system could change software and/or change hardware, no matter the faults caused by software or hardware.

Sustainability refers to a system’s ability to sustain or to maintain itself. A sustainable robot may have redundant parts which are used to replace the failed parts when failures happen. Survivability is the ability of a system or an object to live or exist, especially in spite of difficult conditions [12]. Long-term physical survivability of most robotic systems today is achieved through durable hardware [13]. Robustness is defined as “an ability that allows a system to maintain its functions against internal and external perturbations or noises” in [14]: that is, how a system is insensitive to noises. Reliability is defined as “the ability of a system or component to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period of time” [15]; that is, how a system is sensitive to random failures. Reliable systems are close to the survival systems, and they are focused on how the system functions subject to the external disturbance; they are in the strategy of prevention (reliability) and absorption during the event (robustness). The definition of dependability is the ability of a system to deliver a service that can justifiably be trusted and to avoid failures [16]. The dependable system or robot refers to the faith in a robot for its fulfillment of functions under a condition from the perspective of the user of the robot. The reliable and robust system can add value to the faith of the user. The resilient robot adds more faith to the user. That is to say, a robot that has reliability, robustness, and resilience is a highly dependable robot.

In conclusion, resilient robots have the following four merits: (1) cost-effectiveness: the reusage of the remaining systems reduces costs by extending system life; (2) repairability: the redundancy may be brought in to deal with the faults caused by an internal/external environment; (3) durability: a component for one function can be trained to achieve another function of another component against the system malfunction; and (4) interconnectability: the ease of replacement of the damaged components.

2.2. The Concept of Resilient Robots

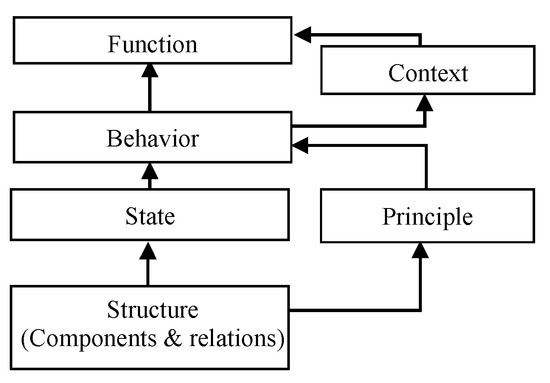

Another interpretation of the concept of resilience for robots lies in how a system’s function is recovered. In this paper, we employ a general system modeling tool named FCBPSS [17] to account for different views of the concept of resilience for a robotic system. The FCBPSS model has been used for the design of general products, and it provides a comprehensive approach to analyze and synthesize a system [18]. The FCBPSS model can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Function-context-behavior-principle-state-structure (FCBPSS) model. The Structure refers to components and connections among the components. The State refers to attributes of a structure. The Principle refers to fundamental laws and effects with which one can develop quantitative relationships among the state variables. The Behavior is represented as a sequence of states and transitions between them, which is governed by the Principle. The Function refers to utilities of a structure owing to its behavior in a context. The Context refers to environments that surround a particular system, which define a specific function of the system.

A key implication of the FCBPSS model with regard to the concept of resilient robots is that the function of a robot can be changed from many sources of means; structure, state, behavior, context, and/or principle, rather than the structure only (which is the case for self-reconfigurable robots). Along this line, we conclude the following strategies for recovery:

- Strategy I:

- Training a remaining system to perform a new behavior, e.g., regeneration of a control system. This strategy refers to the change of a function via behavioral change (i.e., change of the relationship between states). Furthermore, the change of behavior may be due to the change of the principle (e.g., physical effect).

- Strategy II:

- Changing the configuration of a system by re-arranging its components (see self-reconfigurable robot [19]). This strategy refers to the traditional configuration change in self-reconfigurable robots via the change of connectivity among components in a system [19].

- Strategy III:

- Changing the states of components, e.g., changing the length of a bar component; see the so-called adjustable mechanism [20]. This strategy refers to the change of a function via the change of component in itself.

A combination of the above strategies is also possible, which may be called hybrid recovery strategy. It is noted that the above strategies exist to change the function of a system via behavior, state, and/or structure.

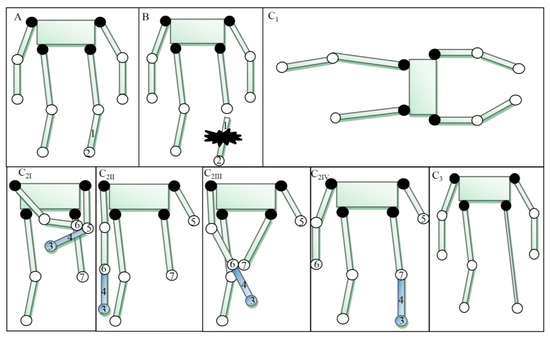

Figure 2 presents an example illustrating the three recovery strategies. Originally, the robot moves by walking (A). After one leg is broken (B), the robot tries to recover its function (i.e., moving) by crawling (C1 via strategy I), or re-arranging the remaining components (C2 via strategy II), or changing the shape of one component (C3 via strategy III).

Figure 2.

Robot recovers to its original function through three strategies, denoted by C1, C2, and C3. (A) The original state of a robot; (B) Part 1 got damaged; (C1) The first recovery strategy: the remaining system is trained to perform a new capability; (C2) The second recovery strategy: the robot rearranges Part 3&4 (dark-colored) to the position of where Part 1&2 used to be by reconfiguring the remaining system. This strategy is as follows: (C2I) Part 6 connects with Part 4; (C2II) Part 4 disconnects with Part 5; (C2III) Part 7 connects with Part 4; (C2IV) Part 4 disconnects with Part 6. (C3) The third recovery strategy: the state of Part 1 changes (i.e., extending Part 1).

2.3. Summary of the Identity of Resilient Robots

In conclusion, the resilient robot has its unique identity. The resilient robot is defined as a robot that is able to recover its original function using its own resources after the system is partially damaged through at least one of the three recovery strategies. The concept of the resilient robot provides a promising method for reducing the loss of robots, and this is very useful for robots in a dangerous environment or a remote environment.

The degree of resilience depends on the degree of recovery of the original function. As seen from Figure 2, if the original function is to move from one place to another place within a certain time (i.e., walking normally), the resilience of the robot in (B) is higher than the robot in (A) as the former one recovers all of the original function, while the latter one recovers partial original function, assuming that walking is faster than crawling. Therefore, a resilient machine which can perform the same function at both a failed state and a new state is called strong resilient machine; otherwise, it is called weak resilient machine [21].

In general, the degree of resilience of robots are affected by: (1) the type of the recovery strategy and the number of the recovery strategies; (2) the performance of the function that can be recovered; (3) the amount of resources needed for the recovery of the function; (4) the amount of time that the damage recovery takes. The next section will give a review and an analysis of the existing work around these factors.

3. Existing Resilient Robots and the Related Robots

3.1. Resilient Robots

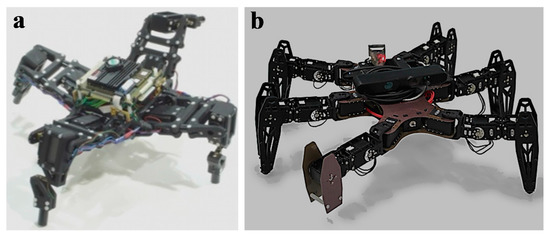

To the best of our knowledge, the black starfish robot designed by Bongard et al. [22] was the first robot to be named resilient robot. It is composed of four identical legs and a main body, as shown in Figure 3a. All joints are actuated by servo-motors. Rotation to different angles can cause the body part to lie flat/downward/upward. The orientation of the main body is measured once the robot performs an action. After one lower limb gets damaged, the robot changes a different behavior to move (Strategy I). Particularly, the robot uses a combination of a self-model method and a learning algorithm to search the behavior, especially; the robot firstly builds an internal simulation of the robot by observing the results of several basic actions (called self-model), and then launches an evolutionary algorithm (EA) in this simulation to find a new controller. Although self-modeling methods increase the computation speed as they transfer some of the learning time to simulation, EA is costly as it requires a high number of tests on real robots even if some of the tests are useless. To increase the speed of operation, this algorithm reduces the number of candidate solutions at the expense of accuracy. Similarly, EA has been applied for damage recovery on a snake robot with a damaged body in [23] and a four-legged robot with a broken leg [24].

Figure 3.

Resilient robots. (a) Four-legged resilient machine [22]; (b) Hexapod resilient robot [32].

There are numerous learning systems for robots to learn the best behavior for damage recovery [25,26]. Most robots learn their behaviors by tuning controllers [27], and some of them can adapt to unexpected situations [24]. The work in [28] used central-pattern-generator-based strategy to find efficient locomotion gaits after failures of several actuators. The work in [29] pre-defined different gait sequences for possible failures. The work in [30] incorporated the reinforcement learning scheme into the free gait generation to choose more stable state after losing one leg. The work in [31] combined reinforcement learning and policy gradient algorithm for motor skills. Although the policy gradient algorithm runs fast, it could easily fall into local optima. Koos et al. [32] tested a T-resilience algorithm on a hexapod robot (Figure 3b), which used Bongard’s self-model method [22] to transfer learning to simulation, and modeled the difference between simulation and reality to avoid unreliable models, and thus increased the computation speed greatly.

In general, learning-based approaches and self-model methods are more efficient for robots that recover their original functions by changing behaviors. If these robots are limited to recovering functions by changing behaviors—that is, they can only deal with a certain type of damage in specified tasks—then the resilience of these robots is still relatively low. Thus, a combination of two or more recovery strategies become necessary. For instance, the work in [33,34] proposed a hybrid evolutionary designer that simultaneously evolves morphology and controller (i.e., integrating Strategy I and II), although there is no failure involved.

3.2. Self-Reconfigurable Robots and Soft Robots

3.2.1. Architecture of Self-Reconfigurable Robots

Self-reconfigurable robots are a class of robots that are composed of many homogeneous or heterogeneous modules that can change the way they are connected on their own, thus changing the overall shape of the robot [19]. Their promise of high versatility and high robustness may bring higher resilience for robots. For instance, they could drop the damaged modules and replace them with other modules when suffering failures. This addresses Strategy II.

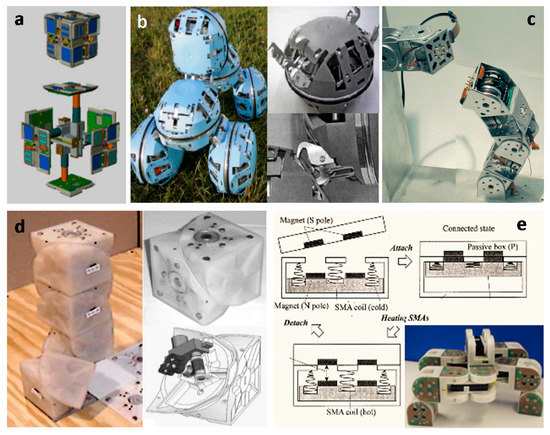

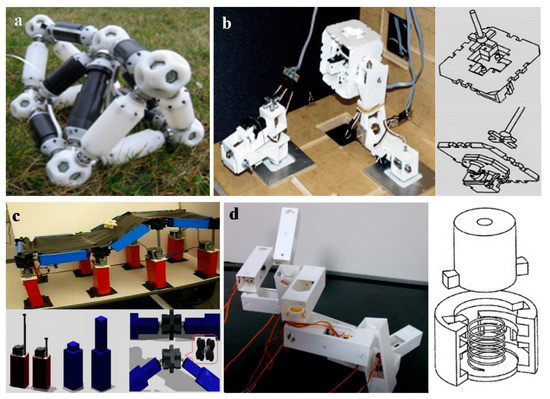

Most self-reconfigurable robots are homogeneous systems, and they are assembled from a single type of module which encapsulates actuator, connection system, sensor, controller, and effector, such as Telecubes robot [35], ATRON robot [2], Polybot robot [36], Molecube robot [13], and MTRAN robot [37], as shown in Figure 4. Heterogeneous robots contain several types of modules with different functionalities, and each module encapsulates the subsystems of structure, actuation, sensing, and connection, etc. Some of the heterogeneous ones are shown in Figure 5. Most heterogeneous self-reconfigurable robots consist of two types of modules: links and joints. Odin robot [38] consists of active links and active joints, see Figure 5a. The active links provide power and structure functionalities and the active joints forward communication and power between neighboring links. ICubes robot [39] uses passive cubes as structure modules and uses a manipulator to move the passive cubes around. The manipulator is composed of rigid links and active joints, see Figure 5b. Morpho robot [40] is a heterogeneous self-deformable modular robot that can change the overall shape of the robot, see Figure 5c. It consists of rigid links and active links. The active links function like a linear joint that can controllably change the length. The rigid links can be expanded or contracted when active links perform actuation. Zhang et al. [41] developed an underactuated self-reconfigurable robot that is composed of active joints, passive links, passive links and adjustable links (see Figure 5d), where the former two types of modules are fundamental modules, and the latter two ones are formed by them through a passive docking system.

Figure 4.

Homogeneous self-reconfigurable robots. (a) Telecubes with a magnetic connection system [35]; (b) ATRON robot and a hook-based connector [2]; (c) Polybot 3G with a peg-and-latch connection system [36]; (d) Molecube and its modules [13]; (e) MTRAN and its magnetic connection system [37].

Figure 5.

Heterogeneous self-reconfigurable robots. (a) Odin robot [38]; (b) ICubes robot and a pin-and-hole based connector [39]; (c) Morpho robot and its three basic types of modules including active links, rigid links, and connectors [40]; (d) An underactuated resilient robot with active joints, passive links, passive links, and adjustable links [41].

3.2.2. Connection System

Everything that crosses a boundary is facilitated by an interface, which is the connection system in a system. The design of the connection system determines the quality of the entire system, especially for self-reconfigurable robots that emphasize connection and disconnection between modules.

Mechanical latching system enables strong connections, which is the common connection system. PolyBot G3 robot [36] and CONRO robot [42] use peg-and-latch connection systems in which a peg male part is inserted into the female part, and then a latch falls to lock the connection, and the connection is released when the shape memory actuators (SMAs) are heated. Crystalline [43] uses rack-and-pinion mechanism to actuate the expansion and contraction of the faces. Each face of the module has a female or male interface. Two out of the four faces have active latches mechanisms, and the other two have passive channels. The module with faces that actively make the connection is called active, and the one that allows itself to be connected is called passive. Similarly, ICubes robot [39] uses a key-and-lock connection mechanism, where the key inserts into a hole and rotates, and then is fixed into the locked position. The detachment action is carried out in reverse order. This design is simple, but it needs high alignment precision requirement for attachment. Another design is to change the peg into a hook, and the robot uses a hook mechanism to achieve connection and disconnection, such as ATRON robot [2] in Figure 4b. However, the hook-based design is more complex and increases the weight. It is noted that Velcro can be viewed as a hook-based connection system. However, it still needs a detachment mechanism, and this will increase the complexity of the system.

The magnet-based connection is another common approach for MSRR, which guarantees convenient attachment. In M-TRAN robot [37], each module’s faces have polarity, and two connected faces have different polarity to connect. Disconnection of two surfaces was achieved by using SMA coils that, when heated, apply a strong pulling force to overcome the strength of the magnets. Another method of disconnecting two permanent magnet connectors, as applied to the SMORES platform [44], is to insert a docking key system into the connected modules’ docking port, holding it in place while rotating its connector to separate the two magnets. This disconnection is much faster than the SMA approach. The locking actions for magnetic connection systems are relatively simple but the connection is not strong, and it may be disconnected by accident. As well, it consumes a relatively large amount of energy and needs an actuation mechanism for detachment, which is usually more complex and increases the weight and energy consumption. Electromagnets are also used as actuation. However, the electromagnets mechanism is usually more complex, and it increases the weight and energy consumption.

The work in [41] designed a key-lock-based passive docking system (see Figure 5d), in which the “key” of the docking system can have two statuses: (1) the “key” has relative motion with the lock, thus forming a passive joint; (2) the “key” can be locked at different positions in the lock, thus forming an adjustable link. Due to the “poka-yoke” design of the docking system, the connection and disconnection are achieved through simple control with less sensory feedback. Another advantage of this docking system is that the reconfiguration (i.e., connections and disconnections) share the same motor with the locomotion, rather than using a separate drive. Thus, the cost of the system is reduced, and the whole system has a relatively low energy consumption.

3.2.3. Reconfiguration Problems

The self-reconfiguration problem includes goal configuration determination, reconfiguration planning, and reconfiguration scheduling. For goal configuration determination, most work uses heuristic method to guide the search. The work in [45] uses a genetic algorithm (GA) to determine the desired configuration to follow a given trajectory with minimum energy. The work in [46] developed a Melt-Grow algorithm where an initial configuration is melted into an intermediate configuration, and a goal configuration is grown out of the intermediate configuration. Similar approaches include agent-based approach [47], cellular automaton generator [48], and embedded graph grammar model [49].

Reconfiguration planning identifies a sequence of moves from an initial configuration to a goal configuration. Examples of the work for lattice-type self-reconfigurable robots can be seen in [46] and [50,51,52]. It is noted that in lattice-type robots, the position of each module’s position is specified by a unique 2D or 3D coordinates, and the configuration space is relatively small. However, the configuration space of the chain-type robot becomes much larger and the search time becomes longer. Only a few studies on chain-type robots are reported in the current literature [53,54,55,56]. Further, the study in [55] proved that finding the optimal reconfiguration planning problem, i.e., finding the least number of reconfiguration steps from a start configuration to a goal configuration is an NP-complete problem, and they gave the lower and the upper bounds for the minimum number of reconfiguration steps for any given reconfiguration problem.

Reconfiguration scheduling is used to realize a successful reconfiguration plan. The study in [56,57] presented local rules to control the module moves. Different configurations correspond to different conditions. However, it is tedious to define the conditions when there are many possible configurations. By assuming that modules know their global coordinates in the configuration, the work in [58] proposed the coordinate attractor methods that move modules by calculating the direction to the goal position. However, their approaches on self-reconfiguration may not be applicable to the architecture that includes passive joints. The work in [59] introduced a GA-based reconfiguration scheduling approach for an underactuated self-reconfigurable robot that is composed of several types of modules. However, this approach requires a high number of trials, which limits the computation speed.

Although self-reconfigurable robots have great potential to become resilient robots, their resilience has been reduced due to the lack of reliable autonomous control for reconfiguration and the associated mechanism design. Particularly, the existing reconfiguration techniques cannot guarantee to provide a solution within a short time as the reconfiguration is an NP-complete problem [55]. As well, most of the existing self-reconfigurable robots consist of all active joints, if one active joint does not work and becomes passive joints, the system needs to make great effort to evolve a controller for damage recovery. Here, the damaged module is completely useless. In this aspect, the underactuated resilient robot in [41] is more resilient as modules can change their roles based on the docking system instead of rendering the module or even the whole system useless. For instance, this robot can deal with two types of common failures, i.e., joints are locked and unlocked, as these two types of failures can be viewed as the adjustable link (for a failure of a locked active joint) and the passive joint (for the failure of the unlocked active joint). However, the computation speed is slow as the connection/disconnection of the docking system requires very high precision.

Thus, to address the self-reconfiguration challenges, a possible solution for hardware improvement is to include various types of modules, and the functions of the modules can be switched, which can be viewed as an increase in the number of resources. Alternatively, the self-reconfiguration processing time can be reduced by using statistical machine learning techniques to automatically develop distributed controllers for this type of robot, such as deep learning technique [60,61]. This is particularly true when a model is difficult to define, or the model requires precise models, such as soft or underactuated systems [62].

3.3. Soft Robots

Soft robots are capable of deforming their bodies in a continuous way [63], which makes them have the potential to be highly resilient, that is, to achieve damage recovery by extending a part (Strategy III) when the system has modular bodies. However, soft robotics is a nascent field; most systems have relied on conventional, rigid electronics, and the accurate modeling and controlling of a soft robot is still difficult, which makes the application of Strategy I, II, and/or III on soft robot quite challenging. A detailed review can be referred to [64]. However, there has recently been much research, such as the highly compliant modular tensegrity robot [65,66] and the first autonomous soft robot Octobot [67] powered by a chemical reaction controlled by microfluidics. A full discussion of the potential of soft robots to become resilient robots is beyond of the scope of this review, but, as this field matures, we expect greater integration with self-reconfigurable robots and soft robots, resulting in a resilient robot with a high degree of resilience. As another alternative, for rigid robots Strategy III can be achieved by changing the length of two links (i.e., the length between their ends). For instance, the work in [41] introduced an adjustable link assembled with two links by a docking system, where the length of the adjustable link varies with the angle between two rigid links by repositioning the docking system.

4. The Principles of Design of Resilient Robots

Two design principles can be drawn from the review of the existing resilient robots and relevant robots.

Principle I: A robot should be designed with function redundancy. Redundancy means that when one physical part or subsystem (say A) does not run out of its full capability; part of A can be trained to fulfill the role or partial role of another physical part or subsystem [21]. Function redundancy means that a system can perform one function with many configurations or states, that is, a robot has more than one configuration to achieve the same function. For instance, for Koo’s hexapod robot [32], the original state and the damaged state have the same function, i.e., walking from one place to another place. In contrast, the damaged resilient machine in Bongard’s work [22] has a relatively low resilience as the recovered function is crawling instead of walking.

Principle II: The structure of a resilient robot should follow modular architecture [20]. In a modular architecture, all components have standard interfaces to interact with each other, and thus the modular system can easily be changed in terms of configuration. A modular architecture can be further viewed as having two types: (1) both components and their interfaces are of standard; and (2) components are not of standard, but their interfaces are. It is noted that most modular self-reconfigurable robots refer to type (1) only. Type (2) of modular systems allow for a change of the function of components. For instance, when faced with joint failure, the underactuated resilient robot in [41] exhibits a higher degree of resilience than the homogeneous self-reconfigurable robots with all active modules because the damaged modules of the former robot change their roles and are reused rather than becoming useless.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

The field of resilient robotics aims to create the science and applications of self-recovery machines by asking the questions: how do we design and control resilient robots, and how do we use these robots? Damaged robots capable of moving and self-reconfigurable robots capable of grasping rely on their function redundancy and modular architecture to adapt their behavior to their environment and task. These basic behaviors open the door to applications in which robots work in unknown or dangerous environments where replacement or repair of a damaged robot is impossible or cost-prohibited. For instance, the robot could rescue lives in an earthquake, where it could change into different configurations if some components were damaged. But how do we get to the point where resilient robots deliver on their full-potential? We need rapid design tools and fabrication recipes for low-cost but strong robots, novel algorithmic approaches to control behavior changing, and self-reconfiguration and/or state changes that account for fast damage recovery requirements, which are a must in an emergent situation.

But how resilient should a resilient robot be in order to meet its true potential? As with many aspects of robotics, this depends on the failures, task and environment. For domains that require strong resilience (for example, a rescue task) or deal with a great amount of uncertainty (for example, in space), resilient robots can bring the capabilities of robots to new levels. For a specified task, a robot has a relatively higher resilience if it addresses all the three recovery strategies and recovers the function to be the same as the original in the shortest time. As well, learning to predict what behavior should be avoided [68], diagnosing failures, and finding the roots of the failures is a good way to increase the resilience of a robot so that it can be applied to many situations in which a robot has to autonomously adapt its behavior. Improved hardware, such as sensors, actuators, and communication will also lead to higher resilience. We expect a comprehensive measurement of robots’ resilience [69] as well as the relationship with other system properties such as reliability and cost, resulting in strong resilient robots that can overcome more failures.

To sum up, the key directions for the future of this growing field are as follows.

- Identifying the classification of robot failures, and developing methods to predict and prevent the failures.

- Investigating the relationships between recovery strategies and failures, as there may be several strategies available at a point of time when a failure occurs, and one needs to find the best one.

- Developing rapid design tools and fabrication recipes for low-cost but strong resilient robots; modules could switch their role when they fail.

- Developing novel algorithmic approaches, such as learning-based approaches to get reliable autonomous control for resilient robots with consideration of hardware compatibility.

- Developing soft computing techniques for morphological soft robots to allow self-assembly, self-reconfiguration, self-reproduction, self-recovery, etc.

- Determining resilience measurement for different robots affected by different failures. A resilience measure approach would include failure identification and function recovery in terms of time and cost.

- Developing a relationship between resilience and other system properties such as reliability and cost. This is important when a resilient robot is tailored for a particular application.

Acknowledgments

The author (Wenjun Zhang) wants to acknowledge a partial financial support to his involvement from NSF of China (No. 51375166) and NSERC Discovery Grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chennareddy, S.; Agrawal, A.; Karuppiah, A. Modular Self-Reconfigurable Robotic Systems: A Survey on Hardware Architectures. J. Robot. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støy, K.; Brandt, D.; Christensen, J.D. Self-Reconfigurable Robots: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.J.; Lin, Y. On the principle of design of resilient systems—Application to enterprise information systems. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2010, 4, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D.D.; Leveson, N. Resilience Engineering Concepts and Precepts; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patternson, E.S.; Woods, D.D.; Cook, R.I.; Render, M.L. Collaborative cross-checking to enhance resilience. Cognit. Technol. Work 2007, 9, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursztein, E.; Goubault-Larrecq, J. A logical framework for evaluating network resilience against fault and attacks. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., Terzopoulos, D., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 4846, pp. 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Cotran, R.S.; Robbins, S.L. Basic Pathology; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, J.D. Mobile Robots: Motor challenges and material solutions. Science 2007, 318, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geekologie (19 September 2013). Available online: http://geekologie.com/2013/09/self-healing-robot-skin-grows-back-toget.php (accessed on 12 March 2014).

- Avižienis, A.; Laprie, J.; Randell, B.; Landwehr, C. Basic Concepts and Taxonomy of Dependable and Secure Computing. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2004, 1, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster Inc. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary; Merriam-Webster: Springfield, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zykov, V.; Mytilinaios, E.; Desnoyer, M.; Lipson, H. Evolved and designed self-reproducing modular robotics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2007, 23, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Biological robustness. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K.; Ajit, S.; Karanki, D.R. Reliability and Safety Engineering; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, R.; Graefe, V. HERMES—An Intelligent Humanoid Robot Designed and Tested for Dependability. In Experimental Robotics VIII; Siciliano, B., Dario, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Geymany, 2003; pp. 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.J.; Lin, Y.; Sinha, N. On the function-behavior-structure model for design. In Proceedings of the 2nd Canadian Design Engineering Network Conference, Kaninaskis, AB, Canada, 18–20 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, W.J. Towards a novel interface design framework: Function-behavior-state paradigm. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2004, 61, 259–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støy, K.; Nagpal, R. Self-repair through scale independent self-reconfiguration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Robots and Systems, Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; pp. 2062–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.H.; Yang, G.S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.J. On the Concept of the Resilient Machine. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Electronics and Application, Beijing, China, 21–23 June 2011; pp. 357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.J.; van Luttervelt, C.A. Toward a resilient manufacturing system. Ann. CIRP 2011, 60, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongard, J.; Zykov, V.; Lipson, H. Resilient machines through continuous self-modeling. Science 2006, 314, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, S.H.; Bentley, P.J. Innately adaptive robotics through embodied evolution. Auton. Robot. 2006, 20, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, D.; Estevez, N.; Lipson, H. Hardware evolution of analog circuits for in-situ robotic fault-recovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE NASA/DoD Conference on Evolvable Hardware, Washington, DC, USA, 29 June–1 July 2005; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Tuong, D.; Peters, J. Model Learning for Robot Control: A Survey. Cognit. Process. 2011, 12, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, J.; Peters, J. Reinforcement learning in robotics: A survey. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1238–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproewitz, A.; Moeckel, R.; Maye, J.; Ijspeert, A. Learning to move in modular robots using central pattern generators and online optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2008, 27, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.J.; Larsen, J.C.; Stoy, K. Fault-tolerant gait learning and morphology optimization of a polymorphic walking robot. Evol. Syst. 2014, 5, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, K.; Tsai, C.S.; Her, I. Alternative gaits for multiped robots with leg failures to retain maneuverability. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2010, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, M.S.; Leblebicioğlu, K. Free gait generation with reinforcement learning for a six-legged robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2008, 56, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Schaal, S. Reinforcement learning of motor skills with policy gradients. Neural Netw. 2008, 21, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koos, S.; Cully, A.; Mouret, J.B. Fast damage recovery in robotics with the T-resilience algorithm. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1700–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faına, A.; Bellas, F.; Lopez-Pena, F.; Duro, R.J. EDHMoR: Evolutionary designer of heterogeneous modular robots. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2013, 26, 2408–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faına, A.; Bellas, F.; Orjales, F.; Souto, D.; Duro, R.J. An evolution friendly modular architecture to produce feasible robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 63, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.W.; Homans, S.B.; Yim, M. Telecubes: Mechanical design of a module for self-reconfigurable robotics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; pp. 4095–4101. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, M.; Shen, W.M.; Salemi, B.; Rus, D.; Moll, M.; Lipson, H. Modular self-reconfigurable robot systems—Challenges and opportunities for the future. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2007, 14, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Yoshida, E.; Kamimura, A.; Kurokawa, H.; Tomita, K.; Kokaji, S. M-TRAN: Self-reconfigurable modular robotic system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2002, 7, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Stoy, K. The Odin Modular Robot: Electronics and Communication. Master’s Thesis, The Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller Institute, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ünsal, C.; Kiliççöte, H.; Khosla, P.K. A modular self-reconfigurable bipartite robotic system: Implementation and motion planning. Auton. Robot. 2001, 10, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Haller, K.; Ingber, D.; Nagpal, R. Morpho: A self-deformable modular robot inspired by cellular structure. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 3571–3578. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.; Gupta, M.M.; Zhang, W.J. Design of a General Resilient Robotic System Based on Axiomatic Design Theory. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Pusan, Korea, 7–11 July 2015; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Castano, A.; Shen, W.M.; Will, P. CONRO: Towards Deployable Robots with Inter-Robots Metamorphic Capabilities. Auton. Robot. 2000, 8, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Vona, M. Crystalline robots: Self-reconfiguration with compressible unit modules. Auton. Robot. 2001, 10, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.; Kwok, N.; Yim, M. Emulating self-reconfigurable robots-design of the SMORES system. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Robots and Systems, Vilamoura, Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 4464–4469. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, C.L.; Qian, Z.Q.; Zhang, D.; Gupta, M.M.; Zhang, W.J. Configuration Synthesis of Underactuated Resilient Robotic Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Besançon, France, 7–11 July 2014; pp. 721–726. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, D.; Vona, M. Self-reconfiguration planning with compressible unit modules. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Detroit, MI, USA, 10–15 May 1999; pp. 2513–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Bojinov, H.; Casal, A.; Hogg, T. Multiagent control of self-reconfigurable robots. Artif. Intell. 2000, 142, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoy, K. Controlling self-reconfiguration using cellular automata and gradients. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 December 2004; pp. 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- McNew, J.M.; Klavins, E. Locally interacting hybrid systems with embedded graph grammars. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; pp. 6080–6087. [Google Scholar]

- Pamecha, A.; Ebert-Uphoff, I.; Chirikjian, G.S. Useful Metrics for Modular Robot Motion Planning. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1997, 13, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkworthy, T.; Ramamoorthy, S. An efficient algorithm for self-reconfiguration planning in a modular robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 5139–5146. [Google Scholar]

- McNew, J.M.; Klavins, E. Non-deterministic reconfiguration of tree formations. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 11–13 June 2008; pp. 690–697. [Google Scholar]

- Casal, A.; Yim, M. Self-Reconfiguration planning for a class of modular robots. In Proceedings of the SPIE Sensor Fusion and Decentralized Control in Robotic Systems II, Boston, MA, USA, 19 September 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.M.; Salemi, B.; Will, P. Hormone-inspired adaptive communication and distributed control for CONRO self-reconfigurable robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2002, 18, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.L. Self-Reconfiguration Planning for Modular Robots. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Computer Science, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Z.; Kotay, K.; Rus, D.; Tomita, K. Cellular automata for decentralized control of self-reconfigurable robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seoul, Korea, 21–26 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard, E.H.; Lund, H.H. Distributed cluster walk for the ATRON self-reconfigurable robot. Intell. Auton. Syst. 2004, 8, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, E.H. Efficient distributed “hormone” graph gradients. In Proceedings of the 19th International joInt Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Edinburgh, UK, 30 July–5 August 2005; pp. 1489–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Towards a Novel Resilient Robotic System. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, S.; Finn, C.; Darrell, T.; Abbeel, P. End-to-end training of deep visuomotor policies. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 17, 1334–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Katyal, K.D.; Staley, E.W.; Johannes, M.S.; Wang, I.J.; Reiter, A.; Burlina, P. In-Hand Robotic Manipulation via Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Deep Learning for Action and Interaction, in Conjunction with Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 9 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, D.; Rahn, C.; Kier, W.; Walker, I. Soft robotics: Biological inspiration, state of the art, and future research. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2008, 5, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caluwaerts, K.; Despraz, J.; Işçen, A.; Sabelhaus, A.P.; Bruce, J.; Schrauwen, B.; SunSpiral, V. Design and control of compliant tensegrity robots through simulation and hardware validation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, J.; Caluwaerts, K.; Iscen, A.; Sabelhaus, A.; SunSpiral, V. Design and evolution of a modular tensegrity robot platform. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 3483–3489. [Google Scholar]

- Wehner, M.; Truby, R.L.; Fitzgerald, D.J.; Mosadegh, B.; Whitesides, G.M.; Lewis, J.A.; Wood, R.J. An integrated design and fabrication strategy for entirely soft, autonomous robots. Nature 2016, 536, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kessel, P. Path to Cyber Resilience: Sense, Resist, React. EY’s 19th Global Information Security Survey 2016–17. Available online: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-global-information-security-survey-2016-pdf/%24FILE/GISS_2016_Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- Saulnier, K.; Saldaña, D.; Prorok, A.; Pappas, G.J.; Kumar, V. Resilient Flocking for Mobile Robot Teams. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).