Abstract

Trimeric intracellular cation channel A (TRIC-A) provides counter-ion support for sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release, yet its physiological role in the intact heart under stress remains poorly defined. Here, we demonstrate that TRIC-A is essential for maintaining balanced SR Ca2+ release, mitochondrial integrity, and cardiac resilience during β-adrenergic stimulation. Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes exhibited Ca2+ transients evoked by electrical stimuli and exaggerated isoproterenol (ISO)-evoked Ca2+ release, consistent with SR Ca2+ overload. These defects were accompanied by selective upregulation of protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) (S2808) and phospholamban (PLB) (S16). Acute ISO challenge induced mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, and Evans Blue Dye uptake, and elevated circulating troponin T in Tric-a−/− hearts, hallmarks of necrosis-like cell death. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake inhibition with Ru360 markedly reduced membrane injury, establishing mitochondrial Ca2+ overload as the proximal trigger of cardiac cell death. With sustained β-adrenergic stimulation by ISO, Tric-a−/− hearts developed extensive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis without exaggerated hypertrophy. Cardiac fibroblasts lacked TRIC-A expression and displayed normal Ca2+ signaling and activation, indicating that fibrosis arises secondarily from cardiomyocyte injury rather than fibroblast-intrinsic abnormalities. These findings identify TRIC-A as a critical regulator of SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling and a key molecular safeguard that protects the heart from catecholamine-induced injury and maladaptive remodeling.

1. Introduction

Cellular Ca2+ handling is fundamental to cardiac excitation–contraction coupling [1,2,3,4,5,6]. During each heartbeat, tightly coordinated Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) activates the contractile machinery, while subsequent reuptake restores SR Ca2+ load for the next cycle [7,8,9,10]. Because Ca2+ efflux from the SR is electrogenic, a complementary counter-ion movement is required to stabilize SR membrane potential and preserve efficient release [11,12]. Trimeric intracellular cation (TRIC) channels, K+-permeable pores embedded in the SR/ER membrane, have emerged as leading candidates for providing this counter-current [13,14,15,16].

Mammals possess two TRIC isoforms: TRIC-B, which is broadly distributed among cell types, and TRIC-A, which is enriched in excitable cells including skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, and the heart [13,17]. Genetic ablation studies have revealed distinct physiological roles for these isoforms [13,18,19]. TRIC-B deletion impairs IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling and causes perinatal respiratory failure due to dysfunctional alveolar epithelial cells, underscoring its essential role in ER Ca2+ homeostasis [18]. In contrast, loss of TRIC-A yields tissue-specific defects linked to RyR-dependent Ca2+ release [15,19,20]. Tric-a-null skeletal muscle exhibits reduced Ca2+ spark frequency, SR Ca2+ overload, and stress-induced contractile alternans [21], whereas in vascular smooth muscle, TRIC-A deficiency impairs Ca2+ spark generation and amplifies IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ transients, leading to hypertension [15]. In the developing heart, combined deletion of Tric-a and Tric-b results in embryonic lethality, highlighting the non-redundant importance of TRIC channels for Ca2+ handling in immature cardiomyocytes [13]. These isoform-specific roles are further reflected in human disease; loss of TRIC-B, either through TRIC-B mutations in humans or Tric-b knockout in mice, causes bone defects resembling osteogenesis imperfecta [22,23,24,25,26]. In parallel, variants in TMEM38A (e.g., TRIC-A) have been reported in patients with muscle disorders, including Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy [27,28,29].

In adult cardiomyocytes, TRIC-A loss suppresses spontaneous Ca2+ sparks but exaggerates global caffeine-evoked release, suggesting an imbalance between local signaling events and overall SR discharge [19,20]. Mechanistically, TRIC-A has been shown to physically associate with RyR2 via its C-terminal domain, increasing RyR2 open probability and fine-tuning local Ca2+ release dynamics [19]. These observations support a model in which TRIC-A serves dual functions: (a) providing counter-ion flux to support robust RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release, and (b) directly modulating RyR2 gating to prevent store-overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR) [19,20]. In the absence of this regulatory influence, cardiomyocytes become prone to spontaneous Ca2+ waves, arrhythmogenic signaling, and subsequent cellular stress [19,30].

Despite its recognized importance in SR Ca2+ regulation, the role of TRIC-A in maintaining cardiac resilience under neurohumoral stress remains poorly defined. β-adrenergic stimulation, a central regulator of the physiological “fight-or-flight” response, enhances RyR2 activity and increases SR Ca2+ turnover to boost cardiac output [31]. However, chronic or excessive β-adrenergic drive destabilizes SR Ca2+ homeostasis, promotes mitochondrial dysfunction, and contributes to cardiomyocyte death, fibrosis, and heart failure [32,33,34]. Whether TRIC-A acts as a molecular safeguard that stabilizes SR Ca2+ release during β-adrenergic stress has not been addressed.

Since the discovery of TRIC channels in 2007 [13], advances in structural biology and molecular modeling have deepened understanding of their functional architecture [35,36,37,38]. Crystal structures published in 2016 confirmed the trimeric organization of the channel and provided evidence of potential interaction interfaces with RyR complexes [14,19,37]. These structural insights, combined with emerging data on SR/ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ crosstalk, underscore how TRIC channel dysfunction may influence metabolic stress responses and contribute to cardiac pathophysiology [39]. Here, we investigate the role of TRIC-A in maintaining cardiomyocyte stability under β-adrenergic stimulation using complementary in vitro and in vivo models of TRIC-A deficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Tric-a−/− mice were generated as previously described and maintained on a C57BL/6J background with wild-type littermates as controls [13,19]. Male mice aged 8–12 weeks were used. Animals were housed under controlled temperature and light–dark cycles with ad libitum access to food and water. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Virginia (Protocol #4410 approved on 28 October 2022). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Kyoto University ((Protocol #2012-10 approved on 28 February 2014)) according to the regulations on the animal experimentation of Kyoto University and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to NIH guidelines.

2.2. In Vivo β-Adrenergic Stimulation

β-adrenergic stimulation was achieved by continuous administration of isoproterenol using subcutaneous osmotic minipumps (ALZET Osmotic Pump Model No. 1003D for acute stimulation or No. 2002 for chronic stimulation, ALZET LLC, Campbell, CA, USA). For chronic stimulation, isoproterenol hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No. 1351005) was dissolved in sterile saline and delivered via an osmotic minipump at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day for 14 days. Control mice received saline-filled minipumps. Minipumps were implanted under isoflurane anesthesia, and animals were monitored daily. For acute stimulation, isoproterenol (60 mg/kg/day) or isoproterenol plus Ru360 (50 nmol/kg/day, Merck, Burlington, MA, USA, Cat. No. 557440) were dissolved in sterile saline and delivered via an osmotic minipump for 1–3 days.

2.3. In Vivo Angiotensin II and Phenylephrine Treatment

To induce hypertrophic remodeling, angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (PE) was administered continuously using subcutaneous osmotic minipumps (ALZET, Model No. 2002) implanted in the dorsal region under isoflurane anesthesia. AngII was delivered at 2 mg/kg/day for 14 days, and PE was delivered at 75 mg/kg/day for 14 days. Control mice received saline-filled pumps. Animals were monitored daily throughout the infusion period.

2.4. Isolation of Ventricular Cardiomyocytes and Cardiac Fibroblasts

Ventricular cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts were isolated using a standard Langendorff perfusion protocol as previously described [19,40,41]. Isolated hearts from adult Tric-a−/− and WT littermate mice were perfused with a Langendorff apparatus at 37 °C. The enzyme digestion step consisted of perfusing Tyrode’s solution containing 0.4 mg/mL collagenase (Type II, ~250 U/mg; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA, Cat. No. LS004176) and 0.1 mg/mL protease (Type XIV, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. P5147) for 18 min. The Tyrode’s solution contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 5.6 glucose, 10 BDM and 1 taurine (pH 7.4). Cardiomyocytes were dissociated from digested ventricles by gentle mechanical dissociation and used within 3 h. Cardiac fibroblasts were also dissociated from ventricles by gentle mechanical dissociation and used within 5 passages. For cardiac fibroblast proliferation assay, cardiac fibroblasts (passages ≤ 5) were plated at an equal density in culture dishes and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with vehicle, isoproterenol (10 µM), or TGF-β (10 ng/mL). Proliferation was quantified by MTT assay (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan, Cat. No. CK04-01).

2.5. Ca2+ Imaging in Cardiomyocytes and Cardiac Fibroblasts

For intracellular Ca2+ cycling measurements, cardiomyocytes were loaded with 10 μM indo-1 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat. No. I1203) for 10 min, followed by 10 min de-esterification. Indo-1 was excited at 340 nm, and emission was collected at 405 nm and 485 nm. Cells were studied in a solution containing (in mM), 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose (pH 7.4), under basal conditions and during stimulation with 100 nM isoproterenol. Cardiomyocytes were paced at 1 Hz using extracellular platinum electrodes. Fluorescence signals were expressed as F405/F485 and analyzed using MetaFlour ver7.7r3 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

For monitoring intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in cardiac fibroblasts (CFs), the isolated and passaged CFs were incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Dojindo, F015-10). Cells were alternately excited at 340 and 380 nm. A CCD camera (ImagEM, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) mounted on the microscope (DMI 4000B, Leica) equipped with a polychromatic illumination system (MetaFluor ver7.7r3) was used to capture fluorescence emission at >510 nm at room temperature. SR store content was assessed by ionomycin and thapsigargin-induced release, and SOCE by re-addition of extracellular Ca2+ after depletion.

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed as previously described. Left ventricular tissue was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through graded ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (~80 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined by transmission electron microscopy (JEM-200X, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Mitochondrial morphology was analyzed from multiple randomly selected fields per heart by investigators blinded to genotype and treatment.

2.7. Serum Troponin T Assay

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, centrifuged, and serum stored at −80 °C. Troponin T concentrations were measured by ECLIA (electrochemiluminescence immunoassay) at SRL, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) using their routine clinical assay (test directory information provided by SRL).

2.8. Evans Blue Dye Uptake

Cardiomyocyte membrane integrity was assessed using Evans blue dye (EBD) uptake. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of Evans blue dye (1% in phosphate-buffered saline, 10 μL/g body weight). Hearts were harvested 24 h after dye injection, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, and frozen. Serial 5–10 μm cryosections from the mid-ventricular region were examined by fluorescence microscopy using identical acquisition settings. EBD-positive cardiomyocytes were identified by intracellular red fluorescence and quantified from multiple non-overlapping fields. All analyses were performed in a blinded manner. For time-course experiments, Evans blue dye uptake was assessed after 1, 3, 7 and 14 days of isoproterenol treatment, as indicated.

2.9. Histology and Fibrosis Quantification

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and Masson trichrome (MT) staining were conducted by KAC (KAC Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) using their standard protocols. Hearts were excised, rinsed briefly in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h. Fixed tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin according to standard histological procedures. Transverse sections were cut at 5 μm thickness from the mid-ventricular level using a rotary microtome and mounted on glass slides. For assessment of myocardial fibrosis, sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome following the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. HT15). Collagen deposition was visualized as blue staining, whereas myocardium appeared red. Whole-section images were acquired using a bright-field microscope (BX53, EVIDENT, Nagano, Japan) equipped with a digital camera under identical acquisition settings for all samples. Fibrotic area was quantified using Fiji (ImageJ, NIH; version 1.54p) software. Collagen-positive (blue) regions were segmented using RGB color thresholding, using a fixed threshold across all images within an experiment.

2.10. Quantitative RT-PCR

For quantitative PCR analysis, total RNA extracted with Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) from CFs were used as templates for cDNA synthesis (ReverTra ACE qPCR-RT kit, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and analyzed using a real-time PCR system (Thermal Cycler Dice TP800, Ver. 3.01, Takara, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cycle threshold (Ct) was determined from the cDNA amplification curve as an index for relative mRNA content in each reaction. PCR specificity was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

2.11. Western Blotting and Immunostaining

For Western blot, protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF (Polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes, and probed with antibodies against Cav1.2 (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel, Cat. No. ACC-003), pRyR2 Ser2808 (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. PA5-36758), pRyR2 Ser2814 (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. PA5-104558), RyR2 (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. MA3-925), IP3R2 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA, Cat. No. sc-7278), NCX1 (homemade), pPLB Ser16 (Badrilla, Leeds, UK, Cat. No. A010-12AP), pPLB Thr17 (Badrilla, Cat. No. A010-13), PLB (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. MA3-922), SERCA2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat. No. ab2861), CSQs (Santa Cruz, Cat. No. sc-390999), JP2 (homemade), TRIC-A (homemade), TRIC-B (homemade), and Actin (Abcam, Cat. No. ab179467). Blots were visualized by chemiluminescence. Abbreviations are defined in the Abbreviations section below.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

The sample size (n) and the statistical tests used for each dataset are reported in the figure legends. Unless otherwise stated, n represents independent biological replicates (individual mice for in vivo experiments; independent cell preparations or isolations for primary cell studies). Data are presented as group means with error bars representing SEM, as indicated in the figure legends.

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for normally distributed data; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. For experiments involving two independent factors (e.g., genotype × treatment), two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc multiple-comparisons test was performed. For experiments involving three independent factors (e.g., genotype × treatment × time), three-way ANOVA was used, followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test where appropriate, as indicated in the figure legends.

Homogeneity of variance was evaluated by visual inspection of residuals and group dispersion, and no gross variance inequality was observed. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.5.0).

No data points were excluded unless predefined technical failure criteria were met (e.g., unsuccessful isolation or inadequate signal quality precluding quantification). Any exclusions and final sample sizes are reported in the corresponding figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. TRIC-A Deficiency Leads to SR Ca2+ Overload and Baseline Hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 and Phospholamban

To define the role of TRIC-A in excitation–contraction coupling, we first assessed Ca2+ handling in ventricular cardiomyocytes under baseline and β-adrenergic stimulation. Cardiomyocytes were isolated from four mouse groups: WT, Tric-a−/−, and mice treated with or without isoproterenol (ISO).

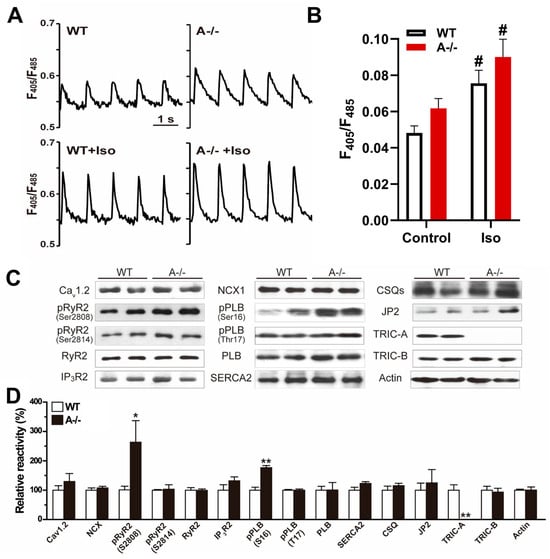

When whole-cell Ca2+ transients were recorded during field stimulation, Tric-a−/− myocytes exhibited significantly larger peak amplitudes compared with WT cells (Figure 1A). ISO enhanced Ca2+ transient amplitude in both genotypes (Figure 1A,B). These findings are consistent with our previous observations and support a model in which loss of TRIC-A diminishes the efficiency of local RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release, causing progressive SR Ca2+ overload. Prior work by Zhou et al. demonstrated that Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes generate fewer spontaneous Ca2+ sparks yet display higher spark amplitude, indicating that SR overload persists despite reduced local release frequency [19]. More recently, we confirmed that while spontaneous sparks are compromised, global caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release is markedly exaggerated in Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes, further indicating excessive SR Ca2+ storage [20,39].

Figure 1.

TRIC-A stabilizes Ca2+ release and limits baseline phosphorylation of RyR2 and phospholamban. (A) Representative Ca2+ transient traces in WT and Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes during electrical stimulation with or without ISO. (B) Quantification of Ca2+ transient amplitude (n = 21). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype (p < 0.05) and treatment (p < 0.001), with no significant interaction. Tukey’s multiple comparisons are indicated (# p < 0.05 Vs. Saline). (C) Immunoblots of Ca2+-handling proteins with actin control. (D) Hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 (S2808) and PLB (S16) in Tric-a−/− hearts (n = 4–8). Student t-test *, ** p < 0.05, 0.01. Original Western Blot images can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Despite substantial differences in Ca2+ handling at the functional level, the expression of major Ca2+-handling proteins, including Cav1.2, NCX, RyR2, SERCA2a, phospholamban (PLB), calsequestrin (CSQ), and junctophilin-2 (JP2), was comparable between WT and Tric-a−/− hearts under baseline condition (Figure 1C). TRIC-B protein abundance was also unchanged, indicating that TRIC isoforms do not compensate for each other at the expression level in adult myocardium.

Because functional alterations were observed in the absence of changes in protein abundance, we next examined phosphorylation states of key Ca2+-regulatory proteins. Using phospho-specific antibodies, we identified a striking increase in RyR2 phosphorylation at serine 2808 (S2808) in Tric-a−/− hearts [42,43], whereas phosphorylation at serine 2814 (S2814), a CaMKII target site, remained unchanged [43,44,45,46]. Parallel analysis revealed a significant elevation in PLB phosphorylation at serine 16 (S16) [47,48,49], the PKA-dependent site, but no detectable change at threonine 17 (T17) [50], the CaMKII-dependent site (Figure 1C,D).

These phosphorylation patterns are consistent with increased basal phosphorylation at PKA-preferred sites in TRIC-A-deficient hearts. Enhanced RyR2-S2808 and PLB-S16 phosphorylation would be expected to promote SR Ca2+ release and accelerate Ca2+ reuptake, respectively, and may represent compensatory adjustments to maintain contractility despite impaired local RyR2 activation in the absence of TRIC-A.

3.2. Acute β-Adrenergic Stimulation Provokes Mitochondrial Injury in TRIC-A Deficient Hearts

The imbalance between local and global Ca2+ release observed in Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes raised the possibility that mitochondria, major Ca2+ buffers and metabolic regulators, may be particularly vulnerable to overload during β-adrenergic stimulation. To evaluate this, we examined cardiac ultrastructure following 24 h of continuous ISO infusion.

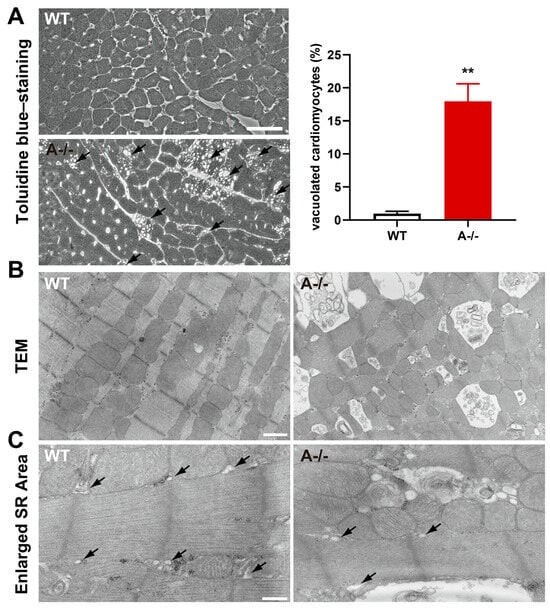

Light microscopy revealed prominent vacuolization in Tric-a−/− hearts, whereas WT myocardium displayed no overt vacuoles (Figure 2A). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that 17.9 ± 2.7% of Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes contained visible vacuoles, indicating a widespread structural response to acute adrenergic stress (Figure 2A). To determine the origin of these vacuoles, we performed transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial abnormalities in ISO-treated Tric-a−/− hearts. (A) Toluidine blue-stained ventricular sections from WT and Tric-a−/− hearts after 24 h ISO treatment, showing vacuolated cardiomyocytes. Arrows indicate vacuole-positive cells (n = 6). Mann–Whitney test ** p < 0.01. (B) Transmission electron micrographs of WT and Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes. Abnormal mitochondria in Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes showing swelling and disrupted cristae. (C) Enlarged cardiomyocyte area. Arrows indicate SR. Scale bars: 50 μm (A), 1 μm (B), and 400 nm (C).

Electron micrographs showed numerous low-density vacuoles dispersed throughout Tric-a−/− cardiomyocytes (Figure 2C). Importantly, the sarcoplasmic reticulum appeared structurally intact in TRIC-A-deficient cells (Figure 2C), consistent with preserved SR membrane organization. In contrast, striking mitochondrial abnormalities were evident in Tric-a−/− hearts (Figure 2B), including swelling, disrupted cristae, and increased electron-lucent regions, hallmarks of mitochondrial permeability transition and Ca2+-induced degeneration.

These observations indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction, rather than SR fragmentation, underlies the vacuolization phenotype in TRIC-A-deficient myocardium. The data support a model in which dysregulated SR Ca2+ release in the absence of TRIC-A directly destabilizes mitochondrial integrity, rendering cardiomyocytes susceptible to acute β-adrenergic stress. Such vulnerability aligns with the known requirement for precise SR–mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling to maintain energetic balance and protect against Ca2+ overload-induced injury.

3.3. Cardiomyocyte Death with Loss of Membrane Integrity Follows Mitochondrial Injury

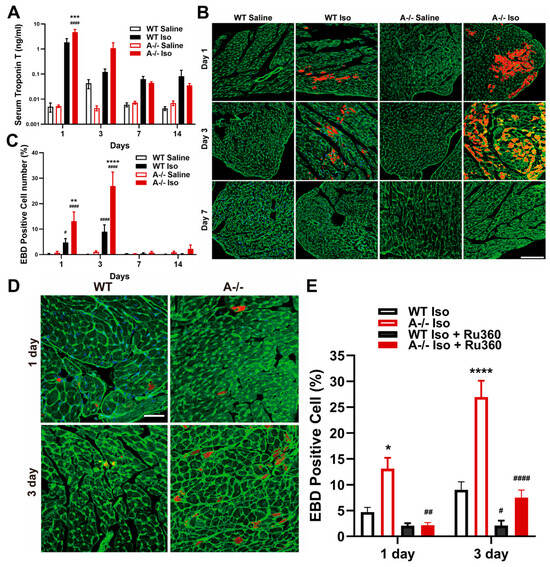

Given the profound mitochondrial abnormalities observed in Tric-a−/− hearts under acute β-adrenergic stimulation, we next asked whether these structural defects were accompanied by cardiomyocyte death. Circulating cardiac troponin T, a sensitive marker released upon sarcolemmal disruption, was markedly elevated in Tric-a−/− mice after 24 h of ISO infusion compared with WT controls (Figure 3A). This systemic increase in troponin T suggests widespread loss of membrane integrity in the absence of TRIC-A.

Figure 3.

Cardiomyocyte injury and ISO-induced cell death with rescue by MCU inhibition. (A) Serum cardiac troponin T levels over time in WT and Tric-a−/− mice after saline or ISO (n = 3–5). Three-way ANOVA showed no main effect of genotype; Post Hoc Tukey’s test indicates a difference at Day 1 **** p < 0.0001 Vs. WT #### p < 0.0001 Vs. Saline. (B) Evans blue dye (EBD)-positive cardiomyocytes over time in WT and Tric-a−/− hearts after saline or ISO. Scale bars = 100 µm. (C) ISO-induced cell death in isolated cardiomyocytes (n = 3). Three-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects and a genotype × treatment × day interaction, all p < 0.0001. (D) Representative images of EBD-stained cardiomyocytes after ISO with or without Ru360, a mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter inhibitor. Scale bars = 500 µm. (E) Quantification of EBD-positive cardiomyocytes showing significant rescue by Ru360 in Tric-a−/− hearts (n = 3). Three-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype, treatment, and day (all p < 0.0001), with significant treatment × genotype (p < 0.001), and day × genotype (p < 0.01) interactions. Symbols indicate Tukey’s multiple comparisons *, **, ***, **** p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 Vs. WT and #, ##, #### p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.0001 Vs. Saline.

To directly evaluate membrane permeability at the cellular level, we used Evans blue dye (EBD), which selectively accumulates in cardiomyocytes with irreversible sarcolemmal damage. Tric-a−/− hearts demonstrated a robust increase in EBD-positive cells as early as day 1 following ISO infusion, with the proportion of injured cardiomyocytes peaking at day 3 before resolving by day 7 (Figure 3B,C). WT hearts displayed only minimal EBD incorporation across all time points, indicating that β-adrenergic stimulation alone is insufficient to provoke comparable membrane damage.

To determine whether mitochondrial Ca2+ overload was a mechanistic driver of this injury, we treated mice with Ru360, a selective inhibitor of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) [51,52,53,54]. Ru360 treatment markedly reduced the number of EBD-positive cardiomyocytes in Tric-a−/− hearts (Figure 3D,E), demonstrating that excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is required for the membrane-disruptive injury phenotype. This rescue effect directly links dysregulated SR–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer to cardiomyocyte death under β-adrenergic stress.

3.4. Sustained β-Adrenergic Stimulation Drives Fibrotic Remodeling in TRIC-A Deficient Hearts

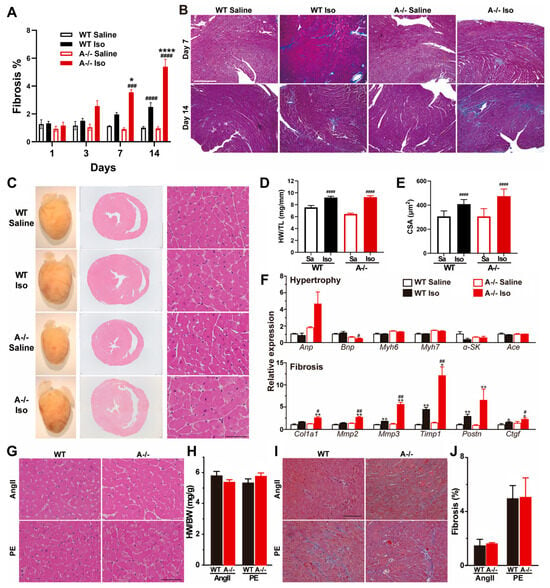

Because cardiomyocyte death often initiates maladaptive tissue remodeling, we next examined whether prolonged β-adrenergic stimulation leads to chronic pathological changes in Tric-a−/− hearts. Histological assessment after 14 days of continuous ISO infusion revealed extensive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis throughout Tric-a−/− ventricles, whereas WT hearts displayed only mild fibrotic deposition (Figure 4A,B). Fibrosis was particularly pronounced within the left ventricular free wall, aligning with regions that exhibited acute injury and membrane disruption in earlier phases of the model.

Figure 4.

ISO-induced fibrosis and remodeling specificity to β-adrenergic stress. (A) Time course of cardiac fibrosis quantified in WT and Tric-a−/− hearts after saline or ISO (n = 3–18). Three-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype (p < 0.01), treatment (p < 0.0001), and day (p < 0.0001), with significant treatment × day (p < 0.0001), treatment × genotype (p < 0.001), and day × genotype (p < 0.05) interactions. (B) Representative Masson’s trichrome-stained ventricular sections after 14 days saline or ISO. (C) Gross heart images and H&E-stained cross-sections after 14 days saline or ISO. (D) Heart weight-to-tibia length ratio (n = 16–19). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype (p < 0.05) and treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as a significant genotype × treatment interaction (p < 0.05). (E) Cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (n = 15–16). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype (p < 0.05) and treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as a significant genotype × treatment interaction (p < 0.05). (F) Relative mRNA expression of hypertrophy markers (upper) and fibrosis markers (lower) in WT and Tric-a−/− hearts with or without ISO (n = 4). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype for all fibrosis markers. (G) Representative HE-stained sections after 14 days angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (PE) treatment. (H) Heart weight-to-body weight ratio after AngII or PE (n = 6). (I), Masson’s trichrome-stained ventricular sections after 14 days AngII or PE. (J) Quantification of fibrotic area after AngII or PE (n = 6–7). Two-way ANOVA found no main effects and no interaction (H,J). Symbols indicate Tukey’s multiple comparisons *, **, **** p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.0001 Vs. WT and #, ##, ###, #### p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 Vs. Saline.

Consistent with these structural findings, Tric-a−/− hearts showed marked transcriptional activation of fibrosis-associated genes, including Col1a1, Mmp3, Timp1, and Ctgf, all of which were significantly upregulated compared with WT (Figure 4F). These molecular signatures confirm a robust profibrotic response downstream of sustained catecholaminergic stress.

Despite the prominent fibrotic remodeling, indices of hypertrophic growth remained largely unchanged between genotypes. Heart weight-to-tibia length ratios, cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area, and classical hypertrophy marker expression were comparable in WT and Tric-a−/− hearts following ISO treatment (Figure 4D–F). We observed that following ISO treatment, Bnp expression appeared to be reduced in Tric-a−/− hearts, whereas Anp expression is increased. The divergent regulation of these canonical hypertrophic markers precludes a definitive conclusion regarding the role of TRIC-A in modulating the cardiac hypertrophic response under β-adrenergic stress.

To determine whether this selective remodeling phenotype was unique to β-adrenergic stimulation, we subjected mice to angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (PE), two established hypertrophic stimuli. Under both conditions, WT and Tric-a−/− hearts developed similar degrees of hypertrophy and fibrosis, with no genotype-dependent differences (Figure 4G–J). These results indicate that TRIC-A deficiency does not globally sensitize the heart to hypertrophic or fibrotic remodeling, but rather exhibits specificity to β-adrenergic pathways.

3.5. Cardiac Fibroblasts Lack TRIC-A Expression and Exhibit Normal Proliferation and Ca2+ Handling

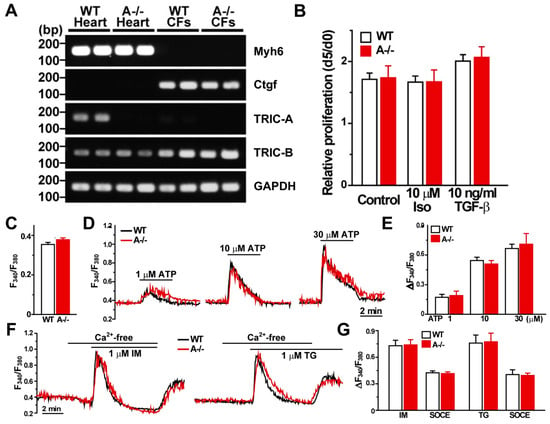

Given the pronounced fibrosis observed in Tric-a−/− hearts following β-adrenergic stimulation, we next examined whether cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) themselves contribute to this exaggerated remodeling response. Type I collagen–positive, α-actinin–negative CFs were isolated and cultured from WT and Tric-a−/− hearts following the protocol described in [41] (Figure 5). As expected, CFs expressed high levels of the fibroblast marker Ctgf, whereas the cardiomyocyte marker Myh6 (Myhc-α) was absent (Figure 5A). RT-PCR confirmed that Tric-a mRNA was undetectable in WT CFs, while Tric-a was readily detected in cardiomyocytes, indicating that fibroblasts do not normally express this channel and are unlikely to be directly impacted by its deletion (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Cardiac fibroblasts lack TRIC-A expression and exhibit normal proliferation and Ca2+ handling. (A) RT-PCR analysis of Myh6 (cardiomyocyte marker), Ctgf (cardiac fibroblast marker), Tric-a, Tric-b, and Gapdh (internal control). Tric-a mRNA was readily detected in cardiomyocytes but was absent in cardiac fibroblasts (CFs), whereas Tric-b was expressed in both populations. (B) Quantification of fibroblast proliferation shows no difference between WT and Tric-a−/− CFs (n = 4). C-G, Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging in CFs isolated from WT and Tric-a−/− mice. (C) Resting cytosolic Ca2+ levels under basal conditions. (D) Representative traces of ATP-induced Ca2+ transients in response to increasing ATP concentrations. (E) Averaged ATP-evoked Ca2+ responses demonstrating comparable purinergic signaling between genotypes (n = 5–6). (F), Representative traces showing ionomycin (IM)- and thapsigargin (TG)-induced Ca2+ release, followed by store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). (G) Quantification of IM- and TG-evoked Ca2+ responses and subsequent SOCE (n = 4–6). Overall, Ca2+ signaling properties, including basal Ca2+ levels, ATP responsiveness, SR store content, and SOCE, were indistinguishable between WT and Tric-a−/− fibroblasts. Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of genotype or treatment and no significant interactions for any measured parameter. Original electrophoresis images can be found in Supplementary Materials.

To assess whether TRIC-A loss alters fibroblast behavior, we first evaluated cell proliferation. Proliferation rates were indistinguishable between WT and Tric-a−/− CFs, and exposure to either 10 μM isoproterenol or 10 ng/mL TGF-β did not modify proliferation in either genotype (Figure 5B).

We next performed Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging to evaluate fibroblast Ca2+ signaling. Baseline cytosolic Ca2+ levels were comparable between WT and Tric-a−/− CFs (Figure 5C). ATP-evoked Ca2+ transients showed similar amplitude and kinetics in both groups (Figure 5D,E), indicating normal purinergic signaling. Ionomycin (IM)- and thapsigargin (TG)-evoked SR Ca2+ release, as well as subsequent store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), were likewise unchanged by TRIC-A deletion (Figure 5F,G). Overall, basal Ca2+ levels, ATP responsiveness, intracellular Ca2+ store content, and SOCE were equivalent between genotypes.

Together, these results demonstrate that cardiac fibroblasts neither express TRIC-A nor exhibit genotype-dependent differences in growth, Ca2+ handling, or profibrotic activation. The absence of intrinsic fibroblast abnormalities strongly supports the conclusion that the exaggerated fibrosis observed in Tric-a−/− hearts is a secondary response to cardiomyocyte injury and necrosis rather than a fibroblast-driven primary defect.

4. Discussion

In this study, we identify TRIC-A as a critical stabilizer of SR Ca2+ release and cardiac stress resilience. Although TRIC-A has long been implicated in counter-ion conductance and RyR2 regulation, its physiological significance in the intact adult heart has remained incompletely understood. Here, we show that loss of TRIC-A disrupts the balance between local and global Ca2+ release, renders mitochondria vulnerable to Ca2+ overload during acute β-adrenergic stimulation, precipitates necrosis-like cardiomyocyte death, and ultimately drives a secondary fibrotic remodeling program. These findings establish TRIC-A as a central gatekeeper that links SR Ca2+ homeostasis to mitochondrial integrity and tissue-level remodeling.

4.1. TRIC-A as a Dual Regulator of SR Ca2+ Release

Our results confirm and extend earlier observations that TRIC-A deficiency alters RyR2-mediated Ca2+ signaling. Tric-a−/− myocytes exhibit reduced spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity but elevated global caffeine-evoked release [20,39], and increased Ca2+ transient amplitude following isoproterenol stimulation, hallmarks of SR Ca2+ overload. These phenomena are consistent with the established concept that TRIC-A provides counter-ion flux necessary to dissipate electrochemical gradients that develop during Ca2+ efflux through RyR2 [13]. In the absence of sufficient counter-current, local release is dampened while overall SR Ca2+ content rises.

At the molecular level, TRIC-A has been shown to interact with RyR2 through its C-terminal tail and enhance RyR2 open probability [19]. In agreement, Tric-a−/− hearts display phosphorylation changes in RyR2 (S2808) and PLB (S16) that are characteristic of compensatory β-adrenergic signaling. These modifications likely reflect attempts to augment RyR2 opening and SERCA activity in the face of impaired local Ca2+ release. Thus, TRIC-A appears to serve dual complementary functions: (1) providing the ionic conditions necessary for efficient SR Ca2+ release, and (2) directly modulating RyR2 gating to tune local Ca2+ signaling.

4.2. β-Adrenergic Stimulation Exposes a Latent Vulnerability in TRIC-A Deficiency

A major finding of this study is that TRIC-A deficiency renders cardiomyocytes highly susceptible to acute β-adrenergic stress. Isoproterenol stimulation, which shifts RyR2 gating and increases SR Ca2+ turnover, precipitated mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, and electron-lucent vacuolization in Tric-a−/− hearts, features classic for Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition. Importantly, SR ultrastructure remained intact, suggesting that mitochondrial destabilization is not secondary to structural collapse of Ca2+ stores but arises directly from dysregulated SR-to-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer.

The fact that Ru360 treatment attenuated EBD uptake in Tric-a−/− hearts firmly implicates mitochondrial Ca2+ overload as the proximate trigger for cardiomyocyte death. These results also highlight that TRIC-A, though localized to the SR, indirectly governs mitochondrial integrity by ensuring appropriately calibrated Ca2+ release during β-adrenergic activation. When this regulation is lost, heightened SR Ca2+ load combined with β-adrenergic augmentation overwhelms mitochondrial buffering capacity, leading to necrotic membrane rupture rather than apoptotic signaling. These data position TRIC-A as a critical stabilizer of Ca2+ flux between the SR and mitochondria, safeguarding cardiomyocyte viability during acute neurohumoral stress.

4.3. Necrosis-Driven Fibrosis as the Dominant Remodeling Pathway

Because cardiomyocyte necrosis is a strong stimulus for fibrotic repair, we examined whether TRIC-A deficiency alters chronic remodeling outcomes. Sustained β-adrenergic stimulation induced extensive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in Tric-a−/− hearts, accompanied by robust upregulation of fibrogenic genes (Col1a1, Mmp3, Timp1, Ctgf). Notably, hypertrophic remodeling was not exaggerated, and Tric-a−/− hearts responded normally to AngII- or PE-induced hypertrophy.

These findings underscore that fibrosis in TRIC-A deficiency is injury-driven rather than hypertrophy-driven. This response is specific to β-adrenergic stress, consistent with the unique ability of catecholamines to destabilize Ca2+ handling when SR regulatory mechanisms fail. Importantly, fibroblasts themselves did not express Tric-a and showed no genotype-dependent differences in growth, Ca2+ signaling, or TGF-β-induced activation. This rules out a fibroblast-intrinsic defect and strengthens the conclusion that fibrosis is a secondary consequence of cardiomyocyte necrosis initiated by mitochondrial Ca2+ overload.

4.4. Implications for Cardiac Physiology and Disease

Our findings provide mechanistic insight into how intracellular ionic countercurrents maintain cardiac resilience during stress. While RyR2 has dominated attention as the central SR Ca2+ release channel, these data highlight the importance of ancillary proteins, such as TRIC-A, that support the electrochemical environment needed for stable release. Loss of TRIC-A reveals an underappreciated vulnerability: RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release becomes uncoupled from its mitochondrial buffering partner, predisposing the heart to catastrophic failure when catecholamine levels rise. The combination of acute cardiomyocyte necrosis and mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent membrane rupture provides a mechanistic basis for the selective fibrotic phenotype, distinguishing β-adrenergic-induced remodeling from classic hypertrophic responses. These insights may have broader implications for conditions characterized by heightened adrenergic drive and mitochondrial dysfunction, including pressure overload, arrhythmogenic disorders, and adrenergic crisis states. They also suggest that modulation of TRIC-A function, or restoration of balanced SR counter-ion flux, could represent a therapeutic strategy to prevent Ca2+ overload-induced myocardial injury.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study establishes TRIC-A as a key regulator of SR–mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling and β-adrenergic stress resilience, several limitations warrant further investigation. First, experiments were performed in male mice. Therefore, future studies will be required to determine whether the observed phenotypes are conserved in females.

Second, our work focuses primarily on global Tric-a knockout mice, which effectively model loss of TRIC-A function but do not distinguish cardiomyocyte-specific versus systemic contributions. While fibroblasts lack Tric-a expression and show no genotype-dependent phenotype, future studies using cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible Tric-a deletion models will be important to definitively establish cell-autonomous roles and to determine whether the susceptibility to adrenergic injury arises during development or in adulthood. Moreover, whether partial TRIC-A loss, akin to human genetic variation or acquired downregulation during heart disease, similarly compromises mitochondrial resilience remains an open question.

Third, we assessed RyR2 and phospholamban phosphorylation primarily under baseline conditions, so β-adrenergic stress–dependent regulation of these phosphorylation endpoints was not directly examined. Future studies should quantify phosphorylation responses to acute ISO stimulation and other β-adrenergic challenges to determine whether TRIC-A deficiency alters stimulus-dependent signaling dynamics.

Fourth, while our results clearly differentiate β-adrenergic-induced fibrosis from AngII- or PE-driven hypertrophy, the molecular basis for this stimulus specificity is not yet understood. Because β-adrenergic signaling uniquely enhances RyR2 activity and accelerates SR Ca2+ turnover, future work should investigate whether TRIC-A’s regulatory influence becomes particularly critical under conditions of heightened Ca2+ flux, arrhythmogenic stress, or catecholamine-driven cardiomyopathies such as Takotsubo syndrome.

Fifth, the translational implications of TRIC-A dysfunction merit further exploration. Human genetic studies have identified variants in the TMEM38A locus [15,28], but the mechanistic significance of these variants remains poorly characterized. Determining whether TMEM38A dysregulation contributes to human cardiomyopathy or stress-induced cardiac injury would provide an important bridge from basic Ca2+-handling biology to clinical application. In parallel, therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating SR counter-ion flux, stabilizing RyR2, or limiting mitochondrial Ca2+ overload may represent new avenues to protect the heart from catecholamine-induced injury.

5. Conclusions

Together, our findings establish TRIC-A as an essential regulator of SR Ca2+ release, mitochondrial integrity, and cardiac stress tolerance. By controlling both the ionic microenvironment and the functional behavior of RyR2, TRIC-A prevents excessive SR Ca2+ loading and protects mitochondria from Ca2+-dependent injury during β-adrenergic activation. Its absence shifts the cardiac injury response toward necrosis and fibrosis, unveiling a critical molecular axis that integrates Ca2+ handling with tissue remodeling. These results advance our understanding of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and identify TRIC-A as a pivotal determinant of cardiac resilience under neurohumoral stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom16020181/s1, Table S1: RT-qPCR primer sequences. Original western blots images and electrophoresis images also in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and H.T.; Methodology, D.Y., K.H.P., X.Z. and M.N.; Investigation, D.Y., X.Z., K.H.P., S.K. and C.Z.; Formal analysis, D.Y., K.H.P. and X.Z.; Resources, J.Z., J.M., M.N. and H.T.; Writing, Review & Editing, D.Y., K.H.P., X.Z., M.N., H.T. and J.M.; Supervision, J.M. and H.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL138570, R01AG071676, R01NS129219, R01HL157215, R01AG072430, and R01EY036243 (to J.M.). This work was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22790209, JP23136506, JP24680041 and JP24659131 (to D.Y.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Virginia (Protocol #4410 approved on 28 October 2022). All experimental procedures were also approved by the Animal Research Committee of Kyoto University (Protocol #2012-10 approved on 28 February 2014) and were performed in compliance with Kyoto University regulations on animal experimentation and relevant institutional guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AngII | Angiotensin II |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BDM | 2,3-Butanedione monoxime |

| CaMKII | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CFs | Cardiac fibroblasts |

| CSQ/CSQs | Calsequestrin |

| EBD | Evans blue dye |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HEPES | 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| IM | Ionomycin |

| ISO | Isoproterenol |

| JP2 | Junctophilin-2 |

| MCU | Mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter |

| MT | Masson trichrome |

| NCX/NCX1 | Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (isoform 1) |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PLB | Phospholamban |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RyR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 |

| SOCE | Store-operated Ca2+ entry |

| SOICR | Store-overload-induced Ca2+ release |

| SR | Sarcoplasmic reticulum |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TG | Thapsigargin |

| TMEM38A | Transmembrane protein 38A |

| TMEM38B | Transmembrane protein 38B |

| TRIC | Trimeric intracellular cation channel |

| TRIC-A | Trimeric intracellular cation channel A (TMEM38A) |

| TRIC-B | Trimeric intracellular cation channel B (TMEM38B) |

| WT | Wild type |

References

- Bers, D.M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 2002, 415, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, B.; Bailey, L.R.J.; Mira Hernandez, J.; Ko, C.Y.; Shen, E.Y.; Bossuyt, J.; Davis, J.M.; Bers, D.M. Excitation-contraction coupling, cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, and transcriptome profiles in two HFpEF murine models: Etiology and sex-dependent differences. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2026, 330, H348–H366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang Bennett, D.S.; Echard, E.J.; Chen, B.; Ciampa, G.; Zhao, W.; Shi, Q.; Yoon, J.Y.; Weiss, R.M.; Grueter, C.E.; et al. Junctophilin-2 Regulates Store-Operated Calcium Entry to Drive Cardiac Fibroblast Activation, Fibrotic Repair, and Angiogenesis After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2025, 152, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, H.; Tan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, L.; Lu, S. Calcium handling remodeling in dilated cardiomyopathy: From molecular mechanisms to targeted therapies. Channels 2025, 19, 2519545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H.; Lyon, A.; Lumens, J.; Schotten, U.; Dobrev, D.; Heijman, J. Cardiomyocyte calcium handling in health and disease: Insights from in vitro and in silico studies. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2020, 157, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiazzi, A.; Jaquenod De Giusti, C.; Valverde, C.A. CaMKII at the crossroads: Calcium dysregulation, and post-translational modifications driving cell death. J. Physiol. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, D.A.; Caldwell, J.L.; Kistamas, K.; Trafford, A.W. Calcium and Excitation-Contraction Coupling in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janicek, R.; Agarwal, H.; Gomez, A.M.; Egger, M.; Ellis-Davies, G.C.R.; Niggli, E. Local recovery of cardiac calcium-induced calcium release interrogated by ultra-effective, two-photon uncaging of calcium. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 3841–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, L.A.; Kanaporis, G.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Oropeza-Almazan, Y.; Banach, K. Excitation-contraction coupling and calcium release in atrial muscle. Pflug. Arch. 2021, 473, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchena, M.; Echebarria, B. Influence of the tubular network on the characteristics of calcium transients in cardiac myocytes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.H.; Stephenson, D.G. Ca2+-movements in muscle modulated by the state of K+-channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes. Pflug. Arch. 1987, 409, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, C.; Zsolnay, V.; Shannon, T.R.; Fill, M.; Gillespie, D. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Cl− concentrations adjust quickly as heart rate changes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2017, 103, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, M.; Ferrante, C.; Feng, J.; Mio, K.; Ogura, T.; Zhang, M.; Lin, P.-H.; Pan, Z.; Komazaki, S.; Kato, K. TRIC channels are essential for Ca2+ handling in intracellular stores. Nature 2007, 448, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuya, G.; Hiraizumi, M.; Maturana, A.D.; Kumazaki, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; Liu, K.; Nakada-Nakura, Y.; Iwata, S.; Tsukada, K.; Komori, T.; et al. Crystal structures of the TRIC trimeric intracellular cation channel orthologues. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, D.; Tabara, Y.; Kita, S.; Hanada, H.; Komazaki, S.; Naitou, D.; Mishima, A.; Nishi, M.; Yamamura, H.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. TRIC-A channels in vascular smooth muscle contribute to blood pressure maintenance. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnay, V.; Fill, M.; Gillespie, D. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Release Uses a Cascading Network of Intra-SR and Channel Countercurrents. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Maturana, A.D. Effects of aging on calcium channels in skeletal muscle. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1558456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, D.; Komazaki, S.; Nakanishi, H.; Mishima, A.; Nishi, M.; Yazawa, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Taguchi, R.; Takeshima, H. Essential role of the TRIC-B channel in Ca2+ handling of alveolar epithelial cells and in perinatal lung maturation. Development 2009, 136, 2355–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Park, K.H.; Yamazaki, D.; Lin, P.H.; Nishi, M.; Ma, Z.; Qiu, L.; Murayama, T.; Zou, X.; Takeshima, H.; et al. TRIC-A Channel Maintains Store Calcium Handling by Interacting with Type 2 Ryanodine Receptor in Cardiac Muscle. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, A.; Lin, P.H.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J. TRIC-A regulates intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiomyocytes. Pflug. Arch. 2021, 473, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yamazaki, D.; Park, K.H.; Komazaki, S.; Tjondrokoesoemo, A.; Nishi, M.; Lin, P.; Hirata, Y.; Brotto, M.; Takeshima, H.; et al. Ca2+ overload and sarcoplasmic reticulum instability in tric-a null skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37370–37376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, W.A.; Ishikawa, M.; Garten, M.; Makareeva, E.N.; Sargent, B.M.; Weis, M.; Barnes, A.M.; Webb, E.A.; Shaw, N.J.; Ala-Kokko, L.; et al. Absence of the ER Cation Channel TMEM38B/TRIC-B Disrupts Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis and Dysregulates Collagen Synthesis in Recessive Osteogenesis Imperfecta. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, F.; Xu, X.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Asan; Wang, J.W.; Song, L.J.; Song, Y.W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, O.; et al. Two novel mutations in TMEM38B result in rare autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 61, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volodarsky, M.; Markus, B.; Cohen, I.; Staretz-Chacham, O.; Flusser, H.; Landau, D.; Shelef, I.; Langer, Y.; Birk, O.S. A deletion mutation in TMEM38B associated with autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinato, E.; Morgan, A.; D’Eustacchio, A.; Pecile, V.; Gortani, G.; Gasparini, P.; Faletra, F. A novel deletion mutation involving TMEM38B in a patient with autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Gene 2014, 545, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, R.; Alazami, A.M.; Alshammari, M.J.; Faqeih, E.; Alhashmi, N.; Mousa, N.; Alsinani, A.; Ansari, S.; Alzahrani, F.; Al-Owain, M.; et al. Study of autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta in Arabia reveals a novel locus defined by TMEM38B mutation. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, M.I.; de Las Heras, J.I.; Czapiewski, R.; Le Thanh, P.; Booth, D.G.; Kelly, D.A.; Webb, S.; Kerr, A.R.W.; Schirmer, E.C. Tissue-Specific Gene Repositioning by Muscle Nuclear Membrane Proteins Enhances Repression of Critical Developmental Genes during Myogenesis. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinke, P.; Kerr, A.R.W.; Czapiewski, R.; de Las Heras, J.I.; Dixon, C.R.; Harris, E.; Kolbel, H.; Muntoni, F.; Schara, U.; Straub, V.; et al. A multistage sequencing strategy pinpoints novel candidate alleles for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and supports gene misregulation as its pathomechanism. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thanh, P.; Meinke, P.; Korfali, N.; Srsen, V.; Robson, M.I.; Wehnert, M.; Schoser, B.; Sewry, C.A.; Schirmer, E.C. Immunohistochemistry on a panel of Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy samples reveals nuclear envelope proteins as inconsistent markers for pathology. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2017, 27, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Xiao, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, R.; Choi, P.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, H.; Chen, S.R. RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death reduce the threshold for store-overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 13062–13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Takahashi, M.; Imagawa, T.; Shigekawa, M.; Takisawa, H.; Nakamura, T. Phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors in rat myocytes during beta-adrenergic stimulation. J. Biochem. 1992, 111, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lucia, C.; Eguchi, A.; Koch, W.J. New Insights in Cardiac beta-Adrenergic Signaling During Heart Failure and Aging. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izem-Meziane, M.; Djerdjouri, B.; Rimbaud, S.; Caffin, F.; Fortin, D.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V.; Joubert, F.; Ventura-Clapier, R. Catecholamine-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening: Protective effect of curcumin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H665–H674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; van den Brink, J.; Bergan-Dahl, A.; Kolstad, T.R.; Norden, E.S.; Hou, Y.; Laasmaa, M.; Aguilar-Sanchez, Y.; Quick, A.P.; Espe, E.K.S.; et al. Prolonged beta-adrenergic stimulation disperses ryanodine receptor clusters in cardiomyocytes and has implications for heart failure. eLife 2022, 11, e77725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Gao, F.; Yuan, Q.; Mao, Y.; Li, D.L.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.H.; Bruni, R.; Kloss, B.; et al. Structural basis for conductance through TRIC cation channels. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, M.; Guo, J.; Ou, X.; Cai, T.; Liu, Z. Pore architecture of TRIC channels and insights into their gating mechanism. Nature 2016, 538, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z. Ion- and water-binding sites inside an occluded hourglass pore of a trimeric intracellular cation (TRIC) channel. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Su, M.; Gao, F.; Xie, W.; Zeng, Y.; Li, D.L.; Liu, X.L.; Zhao, H.; Qin, L.; Li, F.; et al. Structural basis for activity of TRIC counter-ion channels in calcium release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4238–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhou, X.; Park, K.H.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Ko, J.K.; Chen, Y.; Nishi, M.; Yamazaki, D.; Takeshima, H.; et al. TRIC-A Facilitates Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Ca2+ Signaling Crosstalk in Cardiomyocytes. Cells 2025, 14, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Rabinovitch, P.S. Protocol for Isolation of Cardiomyocyte from Adult Mouse and Rat. Bio Protoc. 2022, 12, e4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Huang, Y.; Spencer, C.I.; Foley, A.; Vedantham, V.; Liu, L.; Conway, S.J.; Fu, J.D.; Srivastava, D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature 2012, 485, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, N.D.; Valdivia, H.H.; Niggli, E. PKA phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor modulates SR luminal Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2012, 53, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicek, R.; Camors, E.M.; Potenza, D.M.; Fernandez-Tenorio, M.; Zhao, Y.; Dooge, H.C.; Loaiza, R.; Alvarado, F.J.; Egger, M.; Valdivia, H.H.; et al. Dual ablation of the RyR2-Ser2808 and RyR2-Ser2814 sites increases propensity for pro-arrhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ releases. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 5179–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchinoumi, H.; Yang, Y.; Oda, T.; Li, N.; Alsina, K.M.; Puglisi, J.L.; Chen-Izu, Y.; Cornea, R.L.; Wehrens, X.H.T.; Bers, D.M. CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of RyR2 promotes targetable pathological RyR2 conformational shift. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2016, 98, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, M.; Burgos, J.I.; Ciocci Pardo, A.; Gonzalez Arbelaez, L.; Mosca, S.; Vila Petroff, M. CaMKII-dependent ryanodine receptor phosphorylation mediates sepsis-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 9627–9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, C.A.; Aguero, R.; Wehrens, X.; Vila Petroff, M.; Mattiazzi, A.; Gonano, L.A. RyR2 phosphorylation at serine-2814 increases cardiac tolerance to arrhythmogenic Ca2+ alternans in mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2025, 200, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, A.D.; Jones, L.R. Phosphorylation-induced mobility shift in phospholamban in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Evidence for a protein structure consisting of multiple identical phosphorylatable subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, M.; Kirchberger, M.A.; Katz, A.M. Phosphorylation of a 22,000-dalton component of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 2640–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S.R.; Teng, A.C.T.; Kongmeneck, A.D.; Fang, X.; Phillips, T.A.; Cho, E.E.; Smith, R.A.; Karkut, P.; Makarewich, C.A.; Kekenes-Huskey, P.M.; et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy variant R14del increases phospholamban pentamer stability, blunting dynamic regulation of calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhu, W.Z.; Xiao, B.; Brochet, D.X.; Chen, S.R.; Lakatta, E.G.; Xiao, R.P.; Cheng, H. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors suppresses Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirichok, Y.; Krapivinsky, G.; Clapham, D.E. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 2004, 427, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.L.; Emerson, J.; Clarke, M.J.; Sanadi, D.R. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium ion transport by an oxo-bridged dinuclear ruthenium ammine complex. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 4949–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promila, L.; Sarkar, K.; Guleria, S.; Rakshit, A.; Rathore, M.; Singh, N.C.; Khan, S.; Tomar, M.S.; Ammanathan, V.; Barthwal, M.K.; et al. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulates human fibroblast-like synoviocytes invasion via altering mitochondrial dynamics and dictates rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 234, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Xuan, J.; Chen, T.; Du, Y.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Z.; Wang, J.; Niu, R. Fluoride induces spermatocyte apoptosis by IP3R1/MCU-mediated mitochondrial calcium overload through MAMs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.