Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a major Gram-positive pathogen, and treatment of S. aureus infections is often challenging due to widespread antibiotic resistance. In Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus, D-alanylation of teichoic acids (TA) reduces the net negative charge of the cell envelope and contributes to resistance to diverse antibiotics, particularly cationic antimicrobial peptides. D-alanylation is mediated by the dltABCD operon, which encodes four proteins (DltA, DltB, DltC, and DltD), all of which is essential for the multistep transfer of D-alanine to teichoic acids. Here, we present the first crystal structure of the S. aureus D-alanyl carrier protein DltC and analyze its interaction with DltA using AlphaFold3 and all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. We further show that single substitutions of SaDltA-SaDltC interface residues abolish SaDltC mediated enhancement of SaDltA catalysis. Together, these findings define a catalytically critical S. aureus DltA-DltC interface and provide a structural insight for targeting the D-alanylation pathway as a potential anti-Staphylococcus strategy.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a Gram-positive human pathogen that causes a wide spectrum of diseases, from skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening nosocomial infections [1,2,3]. The global spread of antibiotic-resistant strains—most notably methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA)—has made the development of new therapeutic strategies urgent [4,5]. One of the key cell envelope mechanisms that contributes to virulence and resistance in Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus, is D-alanylation of teichoic acids (Tas) [4,5]. This modification attenuates the negative charge of the cell wall, reducing binding of cationic antimicrobial peptides and decreasing susceptibility to several antibiotic classes [6].

Tas are abundant anionic polymers in the Gram-positive cell wall. In S. aureus, wall teichoic acid (WTA) is covalently linked to peptidoglycan, whereas lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is anchored at the cytoplasmic membrane interface [6]. D-alanine is incorporated into these Tas by the sequential action of four proteins, DltA, B, C, and D, which are encoded by the dltABCD operon [6,7]. Because D-alanylation neutralizes the cell surface charge and modulates antibiotic sensitivity, the Dlt pathway has been considered as an attractive drug target [8,9,10,11,12]. Here, we focus on S. aureus DltC, the D-alanyl carrier protein, and its interaction with SaDltA, the D-alanine-D-analyl carrier protein ligase. Among the four Dlt proteins involved in the D-alanylation process, DltA and DltC operate in the cytosol and initiate the process; DltA activates D-alanine using ATP and subsequently transfers the D-alanine adenylate to the conserved serine residue of DltC (Ser36 in S. aureus DltC), which is post-translationally modified with 4′-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) cofactor, forming DltC-Ppant-D-alanine. DltC is crucial for the transfer of D-alanine to the cell surface with the aid of DltB and DltD, through a not yet fully understood mechanism [3,13,14,15]. Thus, understanding the interaction between DltA and DltC is critical to comprehending the D-alanylation pathway.

Here, we present the crystal structure of SaDltC and analyze its interface with SaDltA with AlphaFold3 modeling and all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. We further show that single-point substitutions of Ser36 in SaDltC—the Ppant attachment site that accepts D-alanine from DltA—as well as of Asp35 and Phe37, residues that lie at the predicted SaDltA-SaDltC interface, abolish the SaDltC-mediated catalytic enhancement of SaDltA activity. Together, these results define a catalytically essential S. aureus DltA-DltC interface and provide structural insight for targeting TA D-alanylation as a potential anti-Staphylococcus strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Cloning and Protein Expression, and Purification

The cDNAs encodes SaDltC (UniProt ID: P0A018) was amplified and expressed as His6-tagged protein using the pET28a expression vector (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). The cDNA that encodes Escherichia coli (E. coli) acyl carrier protein synthase (AcpS, UniProt P24224) was amplified and cloned into the pBAD expression vector (New England Biolabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA, USA), resulting in non-tagged AcpS (for co-expression with wild-type SaDltC). The point mutations were introduced using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). SaDltCWT was co-expressed with AcpS in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to produce Ppant-attached SaDltC. The E. coli cells were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.5, and the protein expression was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG. The bacterial cell culture was further grown at 37 °C for 4 h. The cells were centrifuged at 8000× g and resuspended in purification buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl). After cell lysis by ultrasonication, cell lysate was centrifuged at 20,000× g and bound to an Ni-NTA affinity column. After washing with Buffer A, the bound fractions were eluted with Buffer B (Buffer A supplemented with 300 mM imidazole). The His6-tag was removed by the addition of TEV protease overnight. The non-tagged protein was further purified via size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl. The purified protein was concentrated to 20 mg ml−1. SaDltC mutant proteins were also expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) and purified essentially identically to wild-type SaDltC. The purity of the proteins was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

2.2. Crystallization and Determination of Crystal Structure

Recombinant SaDltCWT protein at a concentration of 20 mg mL−1 in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 200 mM NaCl was used for initial screening of crystallization conditions. A total of 1 µL of protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution consisting of 30% PEG 400, 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate, 0.2 M magnesium chloride, and 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5, at 16 °C. X-ray diffraction data was collected at 100 K using an ADSC Quantum 315r CCD detector system at the BL-7A beamline of Pohang Light Source (Republic of Korea). The SaDltCWT crystal belonged to the monoclinic space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 33.14 Å, b = 63.97 Å, c = 77.14 Å, α = γ = 90.00°, β = 93.95°. The raw data were processed and scaled using HKL-2000 [16]. SaDltCS36A protein crystal was obtained from 14% PEG 8 K, 18% PEG 400, 0.1 M magnesium chloride, and 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5 at 16 °C. A set of X-ray diffraction data was collected at 100 K, also at the BL-7A beamline of Pohang Light Source. The SaDltCS36A crystal belonged to the orthorhombic space group P21212, with unit cell parameters a = 32.73 Å, b = 157.96 Å, c = 27.8 Å, and α = β = γ = 90.00°. The raw data were processed and scaled as described above (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

2.3. Molecular Dynamics

MD simulations of the SaDltA-SaDltC complex were performed with GROMACS 2024.3 [17]. The Alphafold3-predicted SaDltA-SaDltC complex was used as an initial structure [18]. The AMBER99SB-ILDN force field and TIP3P water were employed for protein parameters [19]. Nonbonded interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 1.0 nm cutoff [20]. Newton’s equations of motion were integrated using the leap-frog algorithm with a 2 fs time step, and all hydrogen bonds were constrained using Linear Constraints Solver (LINCS) algorithm [21]. After energy minimization, the system was equilibrated for 1 ns in the NVT ensemble at 300 K using the V-rescale thermostat with backbone position restraints [22], followed by 2 ns NPT equilibration at 300 K and 1 bar using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat [23]. Production MD simulations of 100 ns was then carried out in the NPT ensemble without restraints. Structural analysis including r.m.s.d., Rg, and inter-chain distances were calculated using GROMACS tools. The inter-chain distance was evaluated as the Euclidean distance between the mass-weighted centers of mass of SaDltA and SaDltC using gmx distance after PBD correction.

2.4. Pyrophosphatedetection Assay

The adenylation activity of recombinant SaDltA was assessed using a pyrophosphate detection assay. Reactions were carried out in the presence of 5 μM SaDltA, 5 units ml−1 inorganic pyrophosphatase, 5 mM ATP, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), and 5 mM D-alanine at 37 °C. The reaction was initiated by the adding D-alanine, and 20 μL aliquots were collected at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 10 min. Each aliquot was immediately mixed with 380 μL dye solution containing 0.033% (w/v) malachite green and 1.3% (w/v) ammonium molybdate in 1.0 M HCl and incubated for 90 s. Absorbance at 620 nm was measured using a BioSpectrometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and reactions lacking 5 μM SaDltA served as blanks. Determination of the adenylation activity of SaDltA in the presence of 300 μM WT or D35A, S36A, F37A mutant SaDltC was determined under essentially identical conditions. Initial rates of the enzyme reaction were derived from phosphate accumulation over time.

3. Results

3.1. Crystal Structures of Wild-Type and Ser36Ala Mutant S. aureus DltC

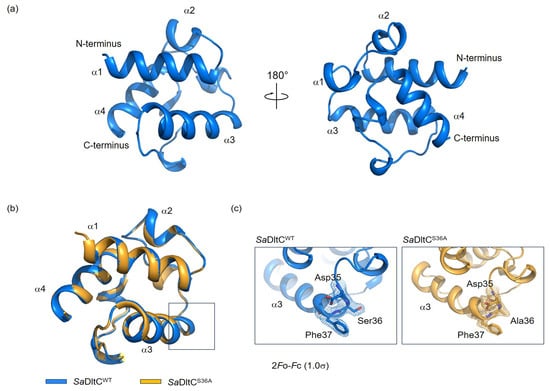

For SaDltC to accept the D-alanine adenylate, Ser36 of SaDltC must be post-translationally modified with a Ppant group by the phosphopantetheinyl transferase AcpS [3]. DltA then transfers the D-alanyl moiety from D-Ala-AMP to the thiol of this Ppant prosthetic group covalently attached to Ser36 of SaDltC, forming a thioester [3]. To understand the structural basis of SaDltC recognition by SaDltA, we determined the crystal structures of the wild-type (SaDltCWT) and non-modifiable Ser36Ala mutant (SaDltCS36A). Both structures were solved by the molecular replacement using B. subtilis DltC [24] as the search model (Table 1). The SaDltCWT contained four DltC molecules in the asymmetric unit (chains A–D), whereas contains SaDltCS36A contains two molecules (chains A and B). Chains within each asymmetric group are essentially identical, with Cα root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values of ~0.14–0.28 Å for SaDltCWT and ~0.24 Å for SaDltCS36A, so unless otherwise noted, we describe chain A for both structures.

The overall structure of SaDltCWT adopts a compact, globular fold consisting of four α-helices: α1 (residues 2–15), α2 (residues 19–22), α3 (residues 38–50), and α4 (residues 67–75) (Figure 1a). Several DltC structures have been elucidated, including the Ppant-loaded form (PDB ID: 4BPH), the apo (non-Ppant modified) form (PDB ID: 4BPG), and the DltB-complexed structures (PDB ID: 8JF2 and 6BUG) [13,24,25]. In all contexts, DltC adopts a highly similar globular fold, with small overall Cα r.m.s.ds between structures, indicating that its compact, globular architecture is strongly conserved during acceptance and handover of D-alanine (Supplementary Table S1). Also, the SaDltCSer36Ala structure was highly similar to SaDltCWT with Cα r.m.s.d. of 0.19 Å, indicating that the mutation does not perturb the global fold of the protein (Figure 1b,c).

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of wild-type Staphylococcus aureus DltC (SaDltCWT) and the Ser36Ala mutant (SaDltCS36A). (a) Overall structure of SaDltCWT in ribbon representations. Two orientations related by a 180° rotation are shown. (b) Superimposition of SaDltCWT (blue) and SaDltCS36A (orange). The structures are globally similar. Boxes indicate Ser36 residues shown in panel c. (c) Close-up views and 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1.0σ around the indicated residues for SaDltCWT (left) and SaDltCS36A (right).

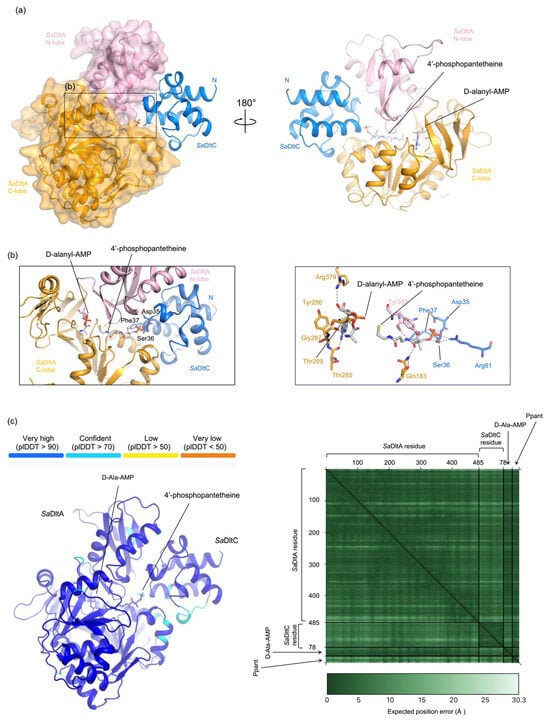

3.2. AF3 Prediction- and MD Simulation-Based Architecture of the SaDltA-SaDltC Interface

Although recent studies have elucidated complex structures of DltC with other Dlt-family proteins, such as DltB and DltD [13,25]—clarifying the architecture of Dlt-mediated D-alanylation and the transfer of D-alanine from the cytosol to TAs—the high-resolution DltA-DltC complex has not been characterized, presumably due to the transient and weak nature of its interaction. SaDltA comprises two structurally distinct lobes, an N-terminal lobe (residues 1–377) and a C-terminal lobe (residues 382–485), linked by a flexible interdomain hinge region (residues 378–381) [26]. Following ATP-dependent adenylation of D-alanine, the C-lobe rotates from the adenylation state to the thiolation state, positioning the D-alanyl-AMP for transfer to DltC [14,15]. We therefore hypothesized that DltC binds DltA in the thiolation state, with the Ppant on Ser36 positioned near the D-alanyl group of D-Ala-AMP.

To test this, we used AlphaFold3 (AF3) to predict the complex structure, using SaDltA, SaDltC, D-alanyl-AMP, and 4′-phosphopantetheine as input. The resulting model revealed SaDltA in a thiolation conformation, similar to thiolation conformation of B. subtilis DltA (PDB ID: 3E7W) [14], with D-alanyl-AMP bound in the active site (Figure 2a). According to PLIP analysis [27], D-Ala-AMP was located in the active site of SaDltA, making extensive hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 2b). Notably, the D-alanyl moiety was positioned adjacent to the thiol group of Ppant, while the phosphate end of the Ppant localizes near Ser36 of SaDltC (Figure 2b). Confidence metrics were high for both proteins (average pLDDT 0.94 for SaDltA; average pLDDT 0.89 for SaDltC) with a low interfacial PAE (~6.0 Å), supporting the reliability of the predicted SaDltA-SaDltC interface (Figure 2c). We also performed an AlphaFold3 prediction of the DltC-DltA complex from B. subtilis, and the predicted overall architecture is similar; the Ppant-accepting serine in B. subtilis DltC (Ser36) adopts a comparable orientation, positioning its side chain toward the phosphopantetheine phosphate head group (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

AF3 model of the SaDltA-SaDltC complex with D-alanyl-AMP and 4′-phosphopantethein. (a) Two orientations (180°) of the AlphaFold3 (AF3) prediction showing SaDltA (orange) and SaDltC (blue). D-alanyl-AMP and 4′-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) are shown as sticks. SaDltA adopts a thiolation conformation similar to that of B. subtilis DltA (PDB ID: 3E7W). (b) Close-up views of the SaDltA-SaDltC AF3 model interface. (c) (Left), per-residue confidence (pLDDT; color scale shown). (Right), predicted aligned error (PAE) heat map.

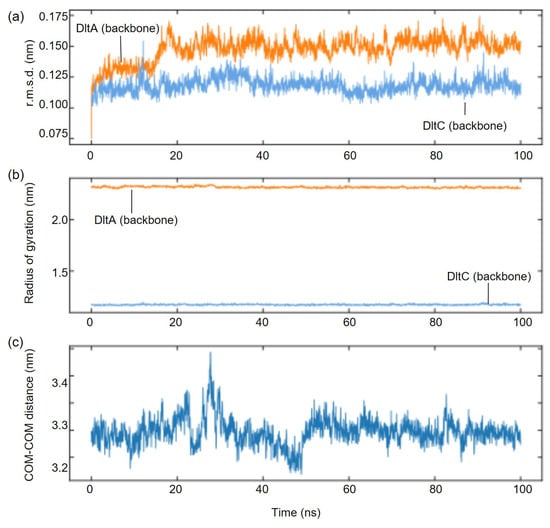

To further assess the interaction between SaDltA and SaDltC, we carried out 100 ns all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using AF3-predicted complex structure as an initial model (Figure 3). Throughout the trajectory, the complex assembly remained stable and compact, without signs of dissociation. Backbone r.m.s.d. values for each SaDltA and SaDltC proteins were stable (SaDltA, ~1.2–1.8 Å; SaDltC, ~0.7–1.1 Å), radii of gyration were also constant (SaDltA, ~23 Å; SaDltC, ~11 Å), and the inter-chain center-of-mass distance fluctuated narrowly around 32~33 Å (Figure 3). Also, the Ser36 of DltA remained stable during the course of MD simulations (Supplementary Figure S2). Collectively, these AF3-predicted structures, as well as the MD simulation data, support the conclusion that (i) SaDltA in the thiolation state engages DltC and (ii) the SaDltC Ser36-centered interface is geometrically compatible with D-alanyl transfer.

Figure 3.

MD analysis for the SaDltA-SaDltC complex. (a) Backbone r.m.s.d of SaDltA (orange) and SaDltC (blue) over a 100 ns trajectory. (b) Radius of gyration (Rg) of backbone atoms for SaDltA (orange) and SaDltC (blue). (c) Center-of-mass (COM-COM) distance between SaDltA and SaDltC as a function of time.

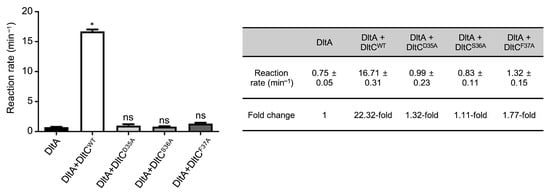

3.3. Mutations of SaDltA-SaDltC Interface Residues Abolish SaDltC-Mediated Enhancement of SaDltA Catalysis

To test the functional relevance of residues highlighted by the AF3 model and MD simulations, we generated alanine substitution mutants at the interface hotspot (Asp35, Ser36, and Phe37) of SaDltC. Adenylation activity of SaDltA was assessed using pyrophosphate detection assays in the presence of WT or mutant SaDltC. SaDltCWT significantly stimulated SaDltA adenylation activity (22.3-fold increase), whereas the Ser36Ala mutant, lacking the serine required for Ppant modification, showed no activation, consistent with a previous report [26] (Figure 4). In addition to the Ser36Ala mutant, mutations of the neighboring residues (Asp35Ala and Phe37Ala) also abolished the significant stimulatory effect, indicating that a SaDltA-SaDltC interaction interface centered around Ser36 of SaDltC is critical for enzymatic function (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SaDltC-dependent activation of SaDltA. Initial reaction rates for SaDltA alone and with SaDltC variants. SaDltCWT strongly stimulates SaDltA, whereas other mutants show no significant enhancement of the activity of SaDltA. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Significant differences were determined by Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (* p < 0.1; ns, not significant).

4. Discussion

S. aureus is a major opportunistic human pathogen that employs diverse immune evasion strategies to cause infections ranging from skin infections to severe, invasive diseases. Further, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), makes S. aureus notorious and complicates its treatment. Current therapeutic options remain limited, underscoring the urgent need for development of new antibacterial strategies [28]. In this context, we studied the structural and functional interplay between two proteins, S. aureus DltA and DltC, components of the Dlt protein family that confer resistance to multiple antibacterials in S. aureus. Dlt proteins catalyze the D-alanylation of teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria, which reduces net charge and thus promotes resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. In this pathway, DltA adenylates the D-alanine to form D-ala-AMP and transfers the D-alanyl moiety to the 4′-phosphopantethein (Ppant) arm attached to Ser36 of SaDltC, the acyl carrier protein. Thus, the DltA-DltC interaction is central to D-alanyl transfer to the cell wall and, consequently, to antimicrobial resistance.

Here, we report two crystal structures of S. aureus DltC (wild-type and Ser36Ala mutant). To our knowledge, these represent the first DltC structure from S. aureus. Both SaDltC crystal structures—wild-type and Ser36Ala mutant—reveal the similar compact globular fold composed of mainly four alpha-helices. DltA is known to transfer D-alanyl-AMP to DltC, initializing subsequent D-alanine transfer from cytosolic space to TAs in the bacterial cell wall. However, this DltA-DltC interaction is thought to be weak, and no high-resolution complex structure has been available. To characterize the weak, transient SaDltA-SaDltC interaction, we combined AF3 structure prediction with all-atom MD simulations. The AF3-predicted model places the Ser36-linked Ppant arm of SaDltC within reach of the D-alanyl group of D-Ala-AMP bound to the catalytic site of SaDltA, consistent with a thiolation-competent configuration. High confidence metrics of the AF3 prediction supported the model’s reliability. To further characterize the interaction, we performed MD simulations and revealed a stable assembly over 100 ns, with SaDltC Ser36 maintaining interactions at the DltA-DltC interface. Mutation of interface residues impaired SaDltA catalytic activity, further validating this binding mode. In the DltB-DltC complex structure, DltC interacts with DltB with an interface that involves not only the Ppant-attached serine residue but also additional structural elements, including the long α3-α4 loop. Similarly, Ser36 together with adjacent structural elements is likely to contribute to DltA-binding surface, providing additional stability and specificity for productive handover during the D-alanylation cycle. Overall, our study specifically shows the overall plausible architecture of the SaDltA-SaDltC interaction, pinpointing Ser36 for the thiolation and D-alanine transfer reaction. Recently, D-Ala-AMP analogs that inhibit DltA enzymatic activity have been shown to re-sensitize methicillin-resistant S. aureus to antibiotics, validating the Dlt pathway as a promising target for novel anti-staphylococcus strategy [29]. In this regard, our structural insight may help to design new classes of antibiotics targeting S. aureus.

5. Conclusions

Our X-ray crystal structures of SaDltCWT and SaDltCS36A revealed that the DltC protein adopts a compact globular fold that is not perturbed by the Ser36Ala mutation, confirming the stability of the core structure. Using an AlphaFold3 prediction and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we provided a model architecture for the transient SaDltA–SaDltC complex. Further, the functional relevance of this predicted interface was validated by in vitro biochemical assays. In conclusion, using combined structural and biochemical approaches, we provide insights for the rational design of new antibacterial agents specifically targeting the dlt operon-mediated cell envelope modification pathway in antibiotic-resistant S. aureus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom16010044/s1, Figure S1: Comparison of AF3 predicted DltA-DltC from S. aureus and B. subtilis. Figure S2: MD analysis for the SaDltC Ser36. Table S1: Structures of DltC homologs.

Author Contributions

I.-G.L. conceptualized and supervised the study. I.-G.L. and H.J. performed the structural and biochemical experiments. C.S. and H.L. conducted the pyrophosphate detection assays. I.-G.L. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00278563; RS-2024-00410675); a Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00399459); and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2025-24534526). This research was also supported by a National Research Council of Science and Technology (NST) grant from the Korean government (MSIT) (No. CAP23013-100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline staff members at the Pohang Light Source, Korea (BL-5C, BL-7A, and BL-11C), for their technical assistance with the X-ray diffraction experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.Y.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, N.; Matos, R.C.; Courtin, P.; Ayala, I.; Akherraz, H.; Simorre, J.-P.; Chapot-Chartier, M.-P.; Leulier, F.; Ravaud, S.; Grangeasse, C. Dltc Acts as an Interaction Hub for Acps, Dlta and Dltb in the Teichoic Acid D-Alanylation Pathway of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13133. [Google Scholar]

- Coupri, D.; Verneuil, N.; Hartke, A.; Liebaut, A.; Lequeux, T.; Pfund, E.; Budin-Verneuil, A. Inhibition of D-Alanylation of Teichoic Acids Overcomes Resistance of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.; Otto, M.; Jack, R.W.; Kalbacher, H.; Jung, G.; Gotz, F. Inactivation of the Dlt Operon in Staphylococcus aureus Confers Sensitivity to Defensins, Protegrins, and Other Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8405–8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, F.C.; Baddiley, J. A Continuum of Anionic Charge: Structures and Functions of D-Alanyl-Teichoic Acids in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 686–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, M.; Glaser, P.; Minutello, A.; Strauch, M.A.; Leopold, K.; Fischer, W. Incorporation of D-Alanine into Lipoteichoic Acid and Wall Teichoic Acid in Bacillus subtilis: Identification of Genes and Regulation (∗). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 15598–15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, M.; Halfmann, A.; Fedtke, I.; Heintz, M.; Peschel, A.; Vollmer, W.; Hakenbeck, R.; Brückner, R. A Functional Dlt Operon, Encoding Proteins Required for Incorporation of D-Alanine in Teichoic Acids in Gram-Positive Bacteria, Confers Resistance to Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5797–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.M.; Sonenshein, A.L. The Dlt Operon Confers Resistance to Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides in Clostridium difficile. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechler, L.; Bonetti, E.-J.; Reichert, S.; Flötenmeyer, M.; Schrenzel, J.; Bertram, R.; François, P.; Götz, F. Daptomycin Tolerance in the Staphylococcus aureus Pita6 Mutant Is Due to Upregulation of the Dlt Operon. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2684–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, M.; Rybtke, M.; Givskov, M.; Høiby, N.; Twetman, S.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. The Dlt Genes Play a Role in Antimicrobial Tolerance of Streptococcus mutans Biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.N.; Bayer, A.S.; Weidenmaier, C.; Grau, T.; Wanner, S.; Stefani, S.; Cafiso, V.; Bertuccio, T.; Yeaman, M.R.; Nast, C.C. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Daptomycin-Resistant Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains: Relative Roles of Mprf and Dlt Operons. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, Z. Structural Insights into the Transporting and Catalyzing Mechanism of Dltb in Lta D-Alanylation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonus, H.; Neumann, P.; Zimmermann, S.; May, J.J.; Marahiel, M.A.; Stubbs, M.T. Crystal Structure of Dlta: Implications for the Reaction Mechanism of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase Adenylation Domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 32484–32491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Luo, Y. Thiolation-Enhanced Substrate Recognition by D-Alanyl Carrier Protein Ligase Dlta from Bacillus cereus. F1000Research 2014, 3, 106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z.; Minor, W. Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 276, pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Gromacs: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with Alphafold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Piana, S.; Palmo, K.; Maragakis, P.; Klepeis, J.L.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E. Improved Side-Chain Torsion Potentials for the Amber Ff99sb Protein Force Field. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2010, 78, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N Log (N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 10089. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.; Fraaije, J.G. Lincs: A Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, S.; Pfennig, S.; Neumann, P.; Yonus, H.; Weininger, U.; Kovermann, M.; Balbach, J.; Stubbs, M.T. High-Resolution Structures of the D-Alanyl Carrier Protein (Dcp) Dltc from Bacillus subtilis Reveal Equivalent Conformations of Apo-and Holo-Forms. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, Z.; Merrikh, C.N.; Lang, K.S.; Lu, P.; Li, X.; Merrikh, H.; Rao, Z.; Xu, W. Crystal Structure of a Membrane-Bound O-Acyltransferase. Nature 2018, 562, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-G.; Song, C.; Yang, S.; Jeon, H.; Park, J.; Yoon, H.-J.; Im, H.; Kang, S.-M.; Eun, H.-J.; Lee, B.-J. Structural and Functional Analysis of the D-Alanyl Carrier Protein Ligase Dlta from Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2022, 78, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salentin, S.; Schreiber, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Adasme, M.F.; Schroeder, M. Plip: Fully Automated Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W443–W447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, P.; Kumar, P.; Mickymaray, S.; Alothaim, A.S.; Somasundaram, J.; Rajan, M. Recent Developments in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Mrsa) Treatment: A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leparfait, D.; Mahé, A.; Feng, X.; Coupri, D.; Le Cavelier, F.; Verneuil, N.; Pfund, E.; Budin-Verneuil, A.; Lequeux, T. Synthesis of New DltA Inhibitors and Their Application as Adjuvant Antibiotics to Re-Sensitize Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2025, 30, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.