Abstract

Recurrent endometrial cancer (EC) has limited therapeutic options beyond platinum-based chemotherapy, highlighting the need to identify exploitable molecular vulnerabilities. Tumors with high genomic instability, including microsatellite instability-high (MSI-h) or copy-number-high (CNH) ECs, rely on the ATR-CHK1 signaling pathway to tolerate replication stress and maintain genome integrity, making this pathway an attractive therapeutic target. However, acquired resistance to ATR and CHK1 inhibitors (ATRi/CHK1i) often develops, and the transcriptomic basis of this resistance in EC remains unknown. Here, we established isogenic ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant cell line models from MSI-h (HEC1A) and CNH (ARK2) EC lineages and performed baseline transcriptomic profiling to characterize stable resistance-associated states. MSI-h-derived resistant clones adopted a unified transcriptional state enriched for epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cytokine signaling, and interferon responses, while ATRi-resistant models showing additional enrichment of developmental and KRAS/Notch-associated pathways. In contrast, CNH-derived resistant clones diverged by inhibitor class, with ATRi resistance preferentially enriching proliferation-associated pathways and CHK1i resistance inducing interferon signaling. Notably, THBS1, EDN1, and TENM2 were consistently upregulated across all resistant models relative to parental lines. Together, these findings demonstrate that acquired resistance to ATRi and CHK1i in EC is shaped by both lineage and inhibitor class and provide a transcriptomic framework that may inform future biomarker development and therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy in developed countries, with rising global incidence and mortality [1,2]. While early-stage EC is often curable with surgery, advanced or recurrent disease has poor outcomes, and five-year survival remains below 20% [1]. Platinum-based chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment, but responses are often limited and rarely durable [3,4]. Targeted therapies such as immune checkpoint blockade for mismatch repair-deficient tumors and HER2-targeted agents for HER2-positive disease have improved outcomes in selected EC subgroups [3,5,6]. However, these treatments apply only to biomarker-defined populations and are often hindered by acquired resistance [3,5,6]. These challenges highlight the need for strategies that target shared biological vulnerabilities in high-risk EC.

Among the molecular subtypes defined by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), microsatellite instability-high (MSI-h) and copy-number-high (CNH) tumors account for a substantial proportion of EC-related deaths [7,8,9]. Despite their distinct genomic features, with mismatch-repair deficiency and inflammatory signaling characterizing the MSI-h subtype [9] and chromosomal instability defining TP53-mutant CNH tumors [10,11,12], both subtypes exhibit high levels of genomic instability and depend on the ATR-CHK1 pathway to maintain genome integrity and survival [13,14,15]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that inhibition of ATR or CHK1 sensitizes EC cells to DNA-damaging agents and promotes mitotic failure, providing a rationale for the clinical evaluation of agents such as the ATR inhibitor (ATRi) camonsertib and the CHK1 inhibitor (CHK1i) prexasertib [16,17,18,19,20].

Despite the therapeutic promise of ATR and CHK1 inhibition, responses are variable and often not durable. Existing mechanistic studies in other cancer types have primarily examined determinants of intrinsic sensitivity rather than acquired resistance, and most have been conducted outside the EC context. For example, CRISPR-based screens in non-EC models have identified genes such as CDC25A [21] and components of the nonsense-mediated decay pathway [22] as modulators of ATRi response in embryonic stem cells or gastric cancer models. In BRCA–wild-type ovarian cancer, reduced CDK1/cyclin B1 activity has been associated with prexasertib resistance [23], while epidermal growth factor receptor pathway has been linked to lower baseline sensitivity to prexasertib in triple-negative breast cancer [24]. However, these studies describe acute or engineered resistance rather than stable resistance that emerges after prolonged drug exposure, and they do not incorporate lineage-specific transcriptional characteristics of MSI-h and CNH EC.

To address these questions, we generated isogenic models of acquired resistance to ATRi camonsertib and CHK1i prexasertib in representative MSI-h and CNH EC cell lines and performed transcriptomic analysis to characterize the adaptive states that emerge after chronic checkpoint kinase inhibition. By comparing resistance patterns across lineages and inhibitor classes, our study provides a systematic framework for understanding the transcriptional features associated with acquired ATRi and CHK1i resistance in EC and lays the groundwork for future mechanistic and translational investigations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drug Preparation

ATRi camonsertib and CHK1i prexasertib were obtained from the Development Therapeutics Program at National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD, USA). All drugs were prepared as separate 10 mM stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; #S-002-M, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) and stored in aliquots at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

EC cell lines were selected to represent the major molecular subtypes defined by TCGA. MSI-h models included AN3CA (#HTB-111, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), HEC1A (#HTB-112, ATCC), MFE296 (#98031101, MilliporeSigma), and Ishikawa (#99040201, MilliporeSigma). CNH-like cell lines included KLE (#CRL-1622, ATCC), MFE280 (#98050131, MilliporeSigma), and ARK1/ARK2 (gifts from Dr. Alessandro D. Santin, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA).

Prexasertib-resistant (PrexR; HEC1A-PrexR1, HEC1A-PrexR2, ARK2-PrexR1, ARK2-PrexR2) and camonsertib-resistant (CamR; HEC1A-CamR1, HEC1A-CamR2, ARK2-CamR1, ARK2-CamR2) lines were generated in-house by culturing parental HEC1A and ARK2 cells with increasing concentrations of prexasertib or camonsertib over 3–6 months. All cell lines described above were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (#11875119, Life Technologies, Frederick, MD, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.01 mg/mL insulin (#I0516, MilliporeSigma), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Resistant cell lines were maintained under continuous selective pressure in the medium containing 1 μM of prexasertib or camonsertib.

All cultures were routinely tested for Mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert Detection Kit (#LT-07-318, Lonza, Portsmouth, NH, USA) and confirmed negative before use in experiments.

2.3. Cell Growth Assay

2000 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with drugs or 0.01% DMSO as control after seeding. After being treated with drugs for 72 h, the cell viability was assessed by the XTT assay (#X6493, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockville, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the absorbances were measured by Synergy™ HTX Multi-Mode Microplate Reader with Gen5™ software (v3.04) (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism v10 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Cell proliferation was assessed using the IncuCyte S5 Live-Cell Analysis System (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). 2000 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight before drug treatment in complete growth medium. Phase-contrast images were acquired every 6 h for 72 h using a 10× objective. Cell confluence was quantified using IncuCyte (v2025C) integrated analysis software and normalized to the initial time point.

2.4. RNA Sequencing Analysis

Resistant cells were cultured in drug-free medium for two weeks prior to RNA extraction to minimize residual transcriptional effects of the selection agents. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (#74104, Qiagen, Frederick, MD, USA) with on-column DNase treatment. Libraries were prepared using the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on a NovaSeq X Plus 10B platform to generate 150 bp paired-end reads (~50 million reads per sample). Reads were quality-trimmed using Cutadapt v3.4 and aligned to the hg38 reference genome using STAR v2.7.9a with GENCODE v38 annotations. Gene expression quantification was performed using STAR/RSEM v1.3.3, followed by quartile normalization and log2 transformation.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using GSEA v4.2.3 with the Hallmark gene set collection. Analyses used gene-set permutation (1000 permutations), and pathways with |normalized enrichment score (NES)| > 1.5, nominal p values < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.25 were considered significant. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 v1.32.0, with significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) defined as those with |log2 fold change| > 1 and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value (padj) < 0.05. Functional enrichment of DEGs was assessed using STRING v12.0 (https://string-db.org/) with Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process terms. Venn diagrams were generated in R (v4.5.1) using the ggVennDiagram package (version 1.5.7).

For heatmap visualization, gene-level RSEM counts were collapsed to unique gene symbols by averaging transcript isoforms, log2(x + 1)—transformed and standardized to row-wise Z-scores. Z-score matrices for selected resistance-associated genes were plotted in R (v4.5.1) using the pheatmap package (v1.0.13).

2.5. TCGA Survival Analysis

Publicly available endometrial cancer datasets were analyzed using cBioPortal (TCGA Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma, PanCancer Atlas, https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=ucec_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018, accessed on 10 January 2026). mRNA expression levels of EDN1, THBS1, and TENM2 were obtained as z-scores relative to diploid samples (RNA Seq V2 RSEM). Patients were stratified into high and low groups using cBioPortal default mRNA expression z-score grouping (relative to diploid samples), and co-expression analyses compared patients with concurrent high EDN1 and THBS1 expression to those with low expression of both genes. Disease-specific survival was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and statistical significance was assessed by log-rank testing.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in at least triplicate. XTT assay data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Correlation between ATRi and CHK1i IC50 values was assessed using two-sided Pearson correlation. For RNA sequencing analyses, DEGs were defined by Benjamini–Hochberg padj < 0.05. For GSEA, pathways with |NES| > 1.5, nominal p < 0.05, and FDR < 0.25 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. EC Cell Lines Display Correlated Sensitivity to ATR and CHK1 Inhibition

To establish a basis for modeling acquired resistance, we first assessed intrinsic sensitivity to ATRi camonsertib and CHK1i prexasertib across a diverse panel of MSI-h and CNH EC cell lines with different genetic background (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of EC cell lines used in this study.

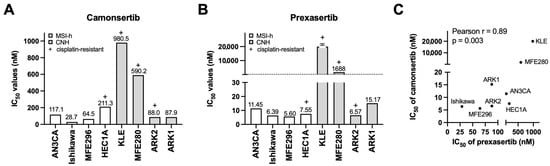

Sensitivity to ATRi varied by approximately 34-fold (Figure 1A), whereas CHK1i showed a >3500-fold dynamic range (Figure 1B). Despite these differences in magnitude, IC50 values for the two inhibitors were strongly correlated (Pearson r = 0.89, p = 0.003; Figure 1C), suggesting shared dependence on the ATR-CHK1 pathway.

Figure 1.

Establishment of the ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant EC cell lines. (A,B) Cell growth was measured by XTT assays. A panel of EC cell lines were treated with the indicated concentrations of ATRi camonsertib (A) and CHK1i prexasertib (B) for 3 days and subjected to XTT assays (n = 3). IC50 values of camonsertib and prexasertib are shown. (C) Correlation between IC50 of camonsertib and prexasertib in tested EC cell lines.

Based on these profiles, HEC1A (MSI-h) and ARK2 (CNH) were selected as parental models for generating resistant derivatives because both showed sensitivity to ATRi and CHK1i, exhibit platinum resistance, and represent clinically relevant high-risk EC subtypes.

3.2. Resistant Lines Exhibit High-Level Resistance and Cross-Resistance Across the ATR-CHK1 Axis

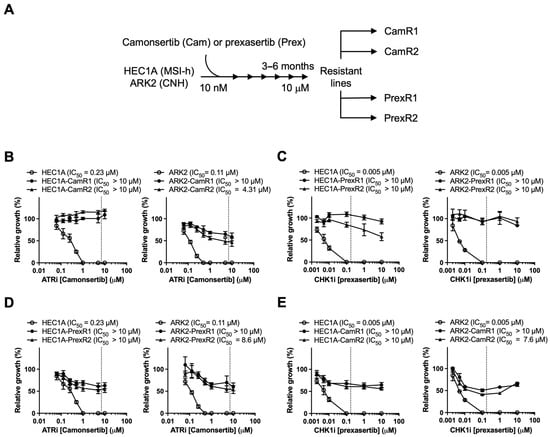

To model acquired resistance, HEC1A and ARK2 cells were exposed to stepwise increases in camonsertib or prexasertib over 3–6 months, generating two independent ATRi-resistant (CamR1, CamR2) and CHK1i-resistant (PrexR1, PrexR2) clones from each lineage (Figure 2A). XTT assays confirmed substantial resistance: CHK1i-resistant clones demonstrated >2000-fold increases in prexasertib IC50 (Figure 2B), and ATRi-resistant lines showed 39–44-fold increases in camonsertib IC50 relative to parental cells (Figure 2C). For both inhibitors, resistant IC50 values exceeded clinically achievable concentrations.

Figure 2.

Establishment of the ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant EC cell lines. (A) Schematic protocol for generating PrexR and CamR derivatives from parental HEC1A (MSI-h) and ARK2 (CNH) cells is shown. (C–E) Cells were treated with camonsertib (B,D) or prexasertib (C,E) at indicated doses for 3 days and subjected to XTT assays (n = 4). Clinically attainable concentrations for prexasertib (0.174 μM) and camonsertib (7 μM) are denoted by the dotted line on each graph.

To assess phenotypic changes associated with resistance, we examined short-term proliferation, morphology, and resistance durability under drug-free conditions. Parental and resistant lines showed comparable baseline growth kinetics and no obvious morphological differences (Figure S1A,B), and resistant clones maintained high-level resistance after 8 weeks of drug withdrawal (Figure S1C), indicating a durable adaptive resistance state.

Cross-resistance analysis showed that PrexR clones were also resistant to ATRi (Figure 2D), and CamR clones displayed comparable resistance to CHK1i (Figure 2E). These findings suggest that prolonged exposure to either inhibitor is associated with reduced responsiveness across the ATR-CHK1 pathway rather than inhibitor-specific resistance alone.

3.3. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Lineage-Associated and Inhibitor-Associated Enrichment Patterns

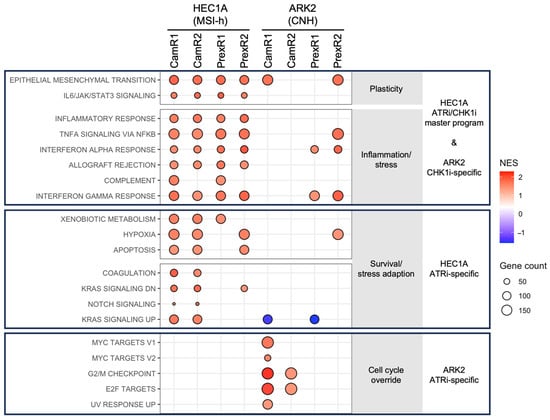

To characterize transcriptional features associated with acquired resistance, RNA sequencing was performed on all resistant clones and corresponding parental lines. GSEA of Hallmark pathways revealed clear lineage- and inhibitor-associated enrichment patterns (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

GSEA reveals lineage- and inhibitor-specific transcriptional features in ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant EC cells. GSEA was performed by comparing each resistant clone (CamR or PrexR) with its matched parental HEC1A or ARK2 line. Pathways meeting |NES| > 1.5, nominal p < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25 are displayed. Each dot represents a significantly enriched Hallmark pathway in a specific clone; dot size reflects the number of leading-edge genes. Red dots indicate the positive NES and blue dots are negative NES. MSI-h–derived HEC1A-resistant clones (top) shared a unified inflammatory-interferon-plasticity transcriptional state, with ATRi-resistant clones (middle) showing additional Notch and KRAS pathway enrichment. In the CNH-derived ARK2 lineage (bottom), ATRi-resistant clones exhibited strong enrichment of proliferation-associated signatures (G2/M checkpoint, E2F, MYC), whereas CHK1i-resistant clones (top) preferentially enriched interferon response pathways. These patterns reveal lineage-defined convergence in MSI-h cells and inhibitor-specific divergence in CNH cells.

Across the MSI-h–derived HEC1A lineage, all resistant clones showed enrichment of pathways related to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), cytokine signaling (IL6/JAK/STAT3, TNFα/NF-κB), and interferon responses (Figure 3 top block and Figure S2A). These consistent associations suggest a shared transcriptional pattern accompanying resistance in this lineage. ATRi-resistant HEC1A clones also showed additional enrichment of Notch, KRAS, and metabolic gene sets (Figure 3 middle block and Figure S2B), indicating further inhibitor-associated transcriptional differences within this background.

In contrast, transcriptional adaptations diverged in the CNH-derived ARK2 lineage. ATRi-resistant ARK2 clones displayed enrichment of proliferation-associated pathways, including G2/M checkpoint, E2F targets, and MYC targets (Figure 3 bottom block and Figure S2C). CHK1i-resistant ARK2 clones, however, did not show this proliferative enrichment and instead were associated with interferon-related pathways (Figure 3 top block and Figure S2D). Together, these observations indicate that MIS-h HEC1A cells develop a convergent transcriptional state under prolonged ATR or CHK1 inhibition, whereas CNH ARK2 cells exhibit inhibitor-associated differences in pathway enrichment.

3.4. Differential Gene Expression Defines Convergent and Inhibitor-Associated Transcriptional Features

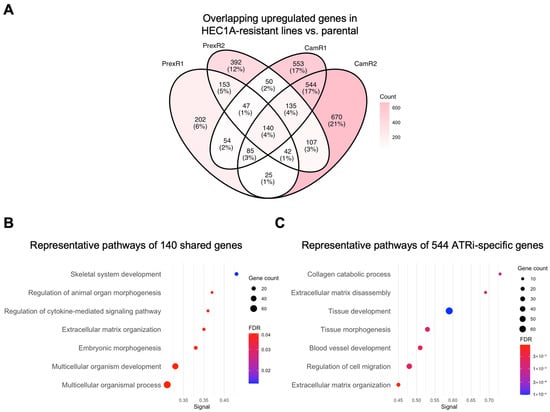

To define the gene-level architecture underlying the adaptive states identified by GSEA, we examined differentially upregulated genes in each resistant clone relative to its parental line and assessed shared and inhibitor-specific signatures using Venn analysis and STRING functional enrichment.

3.4.1. MSI-h Lineage: Shared Resistance Module with Additional ATRi-Associated Remodeling

Differential expression analysis identified 140 genes consistently upregulated across all HEC1A-derived resistant clones. STRING analysis indicated that these shared genes were associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, cytokine signaling, and developmental or morphogenetic processes (Figure 4A,B), consistent with the pathway-level enrichment patterns (Figure 3, top block).

Figure 4.

Gene-level analysis of shared and inhibitor-specific upregulated genes in MSI-h HEC1A-derived ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant clones. (A) Four-way Venn diagram showing the overlap of upregulated DEGs (|log2FC| > 1; padj < 0.05) in HEC1A-CamR1 (Supplementary Table S3), -CamR2 (Supplementary Table S4), -PrexR1 (Supplementary Table S5), -PrexR2 (Supplementary Table S6) compared with parental HEC1A. (B) Representative enriched pathways enriched among the 140 shared genes (Supplementary Table S7), highlighting ECM organization, cytokine-mediated signaling, and multicellular development (Supplementary Table S8) in all HEC1A-derived resistant clones. (C) Representative enriched pathways for the 544 ATRi-specific genes (Supplementary Table S7), including ECM disassembly, collagen catabolism, and tissue morphogenesis (Supplementary Table S9) in ATRi-resistant HEC1A clones. Dot size indicates gene count; color reflects FDR significance.

ATRi-resistant HEC1A clones showed 544 uniquely upregulated genes. These genes were associated with ECM disassembly, collagen catabolism, angiogenesis, and tissue morphogenesis (Figure 4C). These associations suggest that ATRi resistance in HEC1A cells is accompanied by additional transcriptional remodeling beyond the shared resistance module.

CHK1i-resistant HEC1A clones also contained sets of uniquely upregulated genes; however, these gene sets did not yield significant enrichment under the thresholds used for GO enrichment analyses. This may reflect smaller gene set size, greater heterogeneity, or involvement of pathways not well represented in the current annotation databases. Overall, HEC1A-derived resistant clones demonstrated a shared resistance-associated transcriptional pattern, with ATRi resistance showing additional distinct associations.

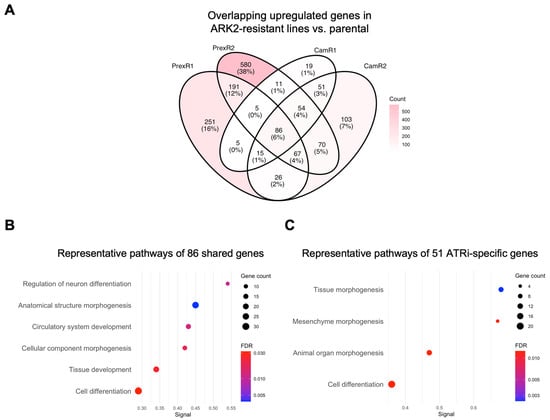

3.4.2. CNH Lineage: Inhibitor-Associated Transcriptional Differences

Across all ARK2-derived resistant clones, 86 genes were consistently upregulated relative to parental ARK2 cells. STRING analysis associated these shared genes with morphogenetic and developmental processes, including anatomical structure formation and vascular development (Figure 5A,B). These features may reflect lineage-intrinsic transcriptional characteristics that persist during resistance acquisition.

Figure 5.

Gene-level analysis reveals shared and inhibitor-specific adaptive modules in CNH ARK2-derived ATRi- or CHK1i-resistant clones. (A) Four-way Venn diagram showing the overlap of upregulated DEGs (|log2FC| > 1; padj < 0.05) in ARK2-CamR1 (Supplementary Table S10), -CamR2 (Supplementary Table S11), -PrexR1 (Supplementary Table S12), -PrexR2 (Supplementary Table S13) compared with parental ARK2. (B) Representative enriched pathways of shared 86 DEGs (Supplementary Table S14) defines a proliferative-morphogenetic core pathways (Supplementary Table S15) in all ARK2-derived-resistant clones. (C) Representative enriched pathways of 51 CamR-only upregulated DEGs (Supplementary Table S14) demonstrates a transcription factor-driven developmental remodeling module (Supplementary Table S16) in ATRi-resistant ARK2 clones. Dot size reflects gene count; dot color indicates FDR.

Inhibitor-associated differences were also observed. ATRi-resistant ARK2 clones showed 51 uniquely upregulated genes that were associated with developmental and morphogenetic processes, including mesenchyme morphogenesis and organ development (Figure 5C). CHK1i-specific DEGs did not show significant pathway-level enrichment, consistent with the more limited gene-level convergence observed under CHK1i in this background.

Together, CNH ARK2-derived resistant clines displayed inhibitor-associated transcriptional differences, with ATRi resistance associated with broader developmental gene expression changes and CHK1i resistance associated primarily with interferon-related pathway enrichment.

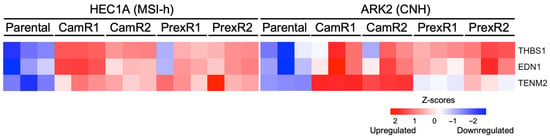

3.4.3. Consistency Analysis Identifies a Small Set of Genes Altered Across All Resistant Clones

To identify transcriptomic features shared across ATRi and CHK1i resistance, we analyzed genes that were consistently upregulated in all eight resistant clones. Only three genes, encoding teneurin-2 (TENM2), thrombospondin-1 (THBS1), and endothelin-1 (EDN1), were uniformly increased across both lineages and inhibitor types. These genes define a minimal lineage-independent resistance signature linked to ECM remodeling (TENM2, THBS1 [25,26]) and pro-survival or proliferative signaling (EDN1 [27,28]). Collectively, this signature suggests that resistant cells may adopt an adhesive and survival-oriented transcriptional state that supports continued proliferation under chronic replication stress (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Shared pan-resistant genes across all CHK1i- and ATRi-resistant MSI-h and CNH clones. Heatmap showing TENM2, THBS1, and EDN1 genes consistently upregulated across all resistant clones compared to parental HEC1A and ARK2 cell lines.

3.4.4. Association of Resistance-Associated Genes with Disease-Specific Survival

To explore the potential clinical relevance of the resistance-associated genes identified in our in vitro findings, we analyzed the TCGA EC cohort. Notably, high expression of EDN1 and THBS1, either individually or in combination, was significantly associated with shorter disease-specific survival (Figure S3). These findings establish a clinical association between components of the in vitro-defined resistance signature and adverse patient outcomes, supporting the relevance of these transcriptional features to aggressive disease biology.

4. Discussion

Cell cycle checkpoint inhibition is a promising therapeutic strategy for genomically unstable EC, particularly in MSI-h and CNH tumors [29,30]. While ATRi camonsertib and CHK1i prexasertib have demonstrated clinical activity in subsets of patients with advanced ovarian cancer or EC, responses are often transient [16,17,18,20], highlighting the need to understand how acquired resistance emerges. Notably, our analysis suggests that acquired resistance to ATRi or CHK1i arises independently of baseline cisplatin sensitivity. This observation is consistent with clinical reports showing activity of ATR-CHK1 pathway inhibitors in heavily pretreated, platinum-resistant patients [16,17,18,20], indicating that the selective pressures underlying resistance to cell cycle checkpoint inhibition are distinct from those driving platinum resistance. Our study systematically examines how acquired resistance to ATRi and CHK1i evolves across different EC lineages.

Within this framework, a key finding is that MSI-h HEC1A-derived–resistant clones converge on a similar adaptive transcriptional state under both ATR and CHK1 inhibition. This shared state integrates inflammatory, interferon, EMT, and ECM-remodeling pathways, features associated with cellular plasticity and therapeutic resistance across solid tumors [31,32]. Given the intrinsically inflammatory signaling environment of MSI-h EC [9], these tumors may be predisposed to adopt such adaptive programs under cell cycle checkpoint inhibition. While ATRi resistance introduces additional developmental and KRAS/Notch-related remodeling, the overarching resistance feature remains conserved within this lineage.

In contrast to the convergent behavior observed in MSI-h HEC1A models, CNH ARK2-derived–resistant clones exhibit inhibitor-specific transcriptional adaptations. ATRi resistance is characterized by enrichment of proliferation-linked programs, whereas CHK1i resistance preferentially activates interferon-related pathways. Such divergence has not been widely reported in other TP53-mutant cancers treated with cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors, where CHK1i resistance has often been attributed to alterations in cell cycle checkpoints and CDK regulation [23], and ATRi resistance has been linked to specific modulators such as CDC25A or nonsense-mediated decay factors [21,22]. Our findings suggest that ATR and CHK1 inhibition impose distinct selective pressures in CNH EC despite a shared replication stress background. Notably, this divergence persists even in the context of cross-resistance, indicating that similar resistance phenotypes can arise through multiple, non-overlapping evolutionary trajectories.

Despite these lineage- and inhibitor-specific differences, only three genes, THBS1, EDN1 and TENM2, were consistently upregulated across all resistant models. THBS1 and TENM2 have been implicated in ECM organization and invasion [25,26], while EDN1 is linked to proliferative and treatment-resistant phenotypes in multiple malignancies [27,28]. Although this three-gene set has not previously been associated with resistance to cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors, its consistent induction across EC lineages and inhibitor classes suggests the existence of a minimal, lineage-independent pan-resistance module that warrants further investigation.

From a hypothesis-generating perspective, our findings also suggest potential directions for subtype-specific therapeutic strategies. In MSI-h EC, adaptive states enriched for inflammatory and EMT-related programs raise the possibility that targeting JAK/STAT or NF-κB pathway inhibition may enhance the durability of cell cycle checkpoint inhibition [33]. In CNH EC, ATRi-associated proliferation and MYC/E2F enrichment point to CDK- or MYC-directed agents as rational combinational partners [34,35], whereas the interferon-associated signature in CHK1i resistance raises questions about whether innate immune pathways contribute directly to adaptation. Collectively, these lineage-associated transcriptional signatures provide a framework for biomarker development. In particular, EDN1 and THBS1 may represent candidate markers of emerging resistance, potentially amenable to longitudinal monitoring through tumor biopsies or circulating RNA-based assays.

Several considerations should be acknowledged when interpreting these findings. First, this study relied on in vitro isogenic models, which capture cell-intrinsic transcriptional adaptations but do not account for tumor microenvironmental influences. In addition, lineage-associated observations were derived from representative MSI-h HEC1A and CNH ARK2 models and may vary across additional EC backgrounds. Importantly, these descriptive transcriptomic data require future proteomic validation to bridge the functional gap between mRNA signatures and protein expression within a multi-omics framework [36]. Our findings should also be considered hypothesis-generating and the identified resistance-associated drivers, such as EDN1 and THBS1 will require validation using CRISPR-based or pharmacologic approaches. While the current lack of public transcriptomic datasets from ATRi- or CHK1i-treated EC patients precludes direct clinical validation, our findings establish a foundational framework that can be tested as these targeted agents continue to advance in clinical development.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study identifies lineage- and inhibitor-specific transcriptomic characteristics that accompany acquired ATRi and CHK1i resistance in EC. MSI-h HEC1A-derived–resistant cells exhibit a convergent inflammatory and EMT-associated pattern, whereas CNH ARK2-derived–resistant EC clones show inhibitor-specific adaptive profiles. These findings provide a molecular framework for understanding resistance-associated transcriptional states and may guide future efforts to define biomarkers or lineage-informed treatment approaches for advanced EC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom16010169/s1, Table S1: GSEA of baseline ATRi- or CHK1i-resistant clones versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S2: GSEA of baseline ATRi- or CHK1i-resistant clones versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S3: DEGs of baseline HEC1A-CamR1 versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S4: DEGs of baseline HEC1A-CamR2 versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S5: DEGs of baseline HEC1A-PrexR1 versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S6: DEGs of baseline HEC1A-PrexR2 versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S7: Overlapping upregulated genes in HEC1A-CamR and HEC1A-PrexR clones versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S8: STRING pathway analysis of 140 overlapping upregulated genes in HEC1A-CamR and HEC1A-PrexR clones versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S9: STRING pathway analysis of 544 unique upregulated genes in HEC1A-CamR clones versus parental HEC1A cells. Table S10: DEGs of baseline ARK2-CamR1 versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S11: DEGs of baseline ARK2-CamR2 versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S12: DEGs of baseline ARK2-PrexR1 versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S13: DEGs of baseline ARK2-PrexR2 versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S14: Overlapping upregulated genes in ARK2-CamR and ARK2-PrexR clones versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S15: STRING pathway analysis of 86 overlapping upregulated genes in ARK2-CamR and ARK2-PrexR clones versus parental ARK2 cells. Table S16: STRING pathway analysis of 51 unique upregulated genes in ARK2-CamR clones versus parental ARK2 cells. Figure S1. Phenotypic characterization and durability of ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant EC cells. Figure S2. Classical GSEA enrichment plots for selected Hallmark pathways in ATRi- and CHK1i-resistant EC cells. Figure S3. Association of resistance-associated genes with disease-specific survival in TCGA endometrial cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-T.H., and J.-M.L.; methodology, T.-T.H.; software, T.-T.H.; formal analysis, T.-T.H.; investigation, T.-T.H.; resources, J.-M.L.; data curation, T.-T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.-T.H., and J.-M.L.; visualization, T.-T.H.; supervision, J.-M.L.; project administration, J.-M.L.; funding acquisition, J.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant ZIA BC011525 awarded to J.-M.L.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank T. Bao, Y. Zhao, J. Shetty at the Sequencing Facility, National Cancer Institute at Frederick for performing RNA sequencing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATR | Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related kinase |

| ATRi | ATR inhibitor |

| CamR | Camonsertib-resistant |

| CHK1 | Cell cycle checkpoint kinase 1 |

| CHK1i | Cell cycle checkpoint kinase 1 inhibitor |

| CNH | Copy-number-high |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| EC | Endometrial cancer |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EDN1 | Endothelin-1 |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GDF15 | Growth/differentiation factor 15 |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 |

| JAK | Janus kinases |

| MSI-h | Microsatellite instability-high |

| NES | Normalized enrichment score |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| padj | Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value |

| PrexR | Prexasertib-resistant |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of tanscription 3 |

| TENM2 | Teneurin-2 |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2025; American Cancer Society, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2025/2025-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- MacKay, H.J.; Freixinos, V.R.; Fleming, G.F. Therapeutic Targets and Opportunities in Endometrial Cancer: Update on Endocrine Therapy and Nonimmunotherapy Targeted Options. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2020, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Jing, Y.; Tang, L.; Lin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; et al. Biomarkers and immunotherapy in endometrial cancer: Mechanisms and clinical applications. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1684549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaknin, A.; Gilbert, L.; Tinker, A.V.; Brown, J.; Mathews, C.; Press, J.; Sabatier, R.; O’Malley, D.M.; Samouelian, V.; Boni, V.; et al. Safety and antitumor activity of dostarlimab in patients with advanced or recurrent DNA mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (dMMR/MSI-H) or proficient/stable (MMRp/MSS) endometrial cancer: Interim results from GARNET-a phase I, single-arm study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhouk, A.; McConechy, M.K.; Leung, S.; Yang, W.; Lum, A.; Senz, J.; Boyd, N.; Pike, J.; Anglesio, M.; Kwon, J.S.; et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, T.; Nout, R.A.; McAlpine, J.N.; McConechy, M.K.; Britton, H.; Hussein, Y.R.; Gonzalez, C.; Ganesan, R.; Steele, J.C.; Harrison, B.T.; et al. Molecular Classification of Grade 3 Endometrioid Endometrial Cancers Identifies Distinct Prognostic Subgroups. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Kandoth, C.; Schultz, N.; Cherniack, A.D.; Akbani, R.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Robertson, A.G.; Pashtan, I.; Shen, R.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden-Amissah, R.E.M.; Annibali, D.; Tuyaerts, S.; Amant, F. Endometrial Cancer Molecular Characterization: The Key to Identifying High-Risk Patients and Defining Guidelines for Clinical Decision-Making? Cancers 2021, 13, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffone, A.; Travaglino, A.; Mascolo, M.; Carotenuto, C.; Guida, M.; Mollo, A.; Insabato, L.; Zullo, F. Histopathological characterization of ProMisE molecular groups of endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 157, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglino, A.; Raffone, A.; Stradella, C.; Esposito, R.; Moretta, P.; Gallo, C.; Orlandi, G.; Insabato, L.; Zullo, F. Impact of endometrial carcinoma histotype on the prognostic value of the TCGA molecular subgroups. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ran, X.; Leung, W.; Kawale, A.; Saxena, S.; Ouyang, J.; Patel, P.S.; Dong, Y.; Yin, T.; Shu, J.; et al. ATR inhibition induces synthetic lethality in mismatch repair-deficient cells and augments immunotherapy. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundle, S.; Bradbury, A.; Drew, Y.; Curtin, N.J. Targeting the ATR-CHK1 Axis in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2017, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Huang, T.T.; Horibata, S.; Lee, J.M. Cell cycle checkpoints and beyond: Exploiting the ATR/CHK1/WEE1 pathway for the treatment of PARP inhibitor-resistant cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Nair, J.; Zimmer, A.; Lipkowitz, S.; Annunziata, C.M.; Merino, M.J.; Swisher, E.M.; Harrell, M.I.; Trepel, J.B.; Lee, M.J.; et al. Prexasertib, a cell cycle checkpoint kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor, in BRCA wild-type recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer: A first-in-class proof-of-concept phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Huang, T.T.; Nair, J.R.; An, D.; Zurcher, G.; Lampert, E.J.; McCoy, A.; Cimino-Mathews, A.; Swisher, E.M.; Radke, M.R.; et al. BLM overexpression as a predictive biomarker for CHK1 inhibitor response in PARP inhibitor-resistant BRCA-mutant ovarian cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadd7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, E.; Huang, T.T.; Nair, J.R.; Zurcher, G.; McCoy, A.; Nousome, D.; Radke, M.R.; Swisher, E.M.; Lipkowitz, S.; Ibanez, K.; et al. The CHK1 inhibitor prexasertib in BRCA wild-type platinum-resistant recurrent high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: A phase 2 trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; MacLaughlan, S.; Matei, D.; Song, M.; Brubaker, L.; Rimmel, B.; Eskander, R.N.; Kyi, C.; Williams, H.; Duska, L.; et al. 744P A phase II study of ACR-368 in patients with ovarian (OvCa) or endometrial carcinoma (EnCa) and prospective validation of OncoSignature patient selection (NCT05548296). Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S564–S565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Fontana, E.; Lee, E.K.; Spigel, D.R.; Hojgaard, M.; Lheureux, S.; Mettu, N.B.; Carneiro, B.A.; Carter, L.; Plummer, R.; et al. Camonsertib in DNA damage response-deficient advanced solid tumors: Phase 1 trial results. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Mayor-Ruiz, C.; Lafarga, V.; Murga, M.; Vega-Sendino, M.; Ortega, S.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O. A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen Identifies CDC25A as a Determinant of Sensitivity to ATR Inhibitors. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, P.C.; Chen, H.; Doruk, Y.U.; Williamson, T.; Polacco, B.; McNeal, A.S.; Shenoy, T.; Kale, N.; Carnevale, J.; Stevenson, E.; et al. Resistance to ATR Inhibitors Is Mediated by Loss of the Nonsense-Mediated Decay Factor UPF2. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3950–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.; Huang, T.T.; Murai, J.; Haynes, B.; Steeg, P.S.; Pommier, Y.; Lee, J.M. Resistance to the CHK1 inhibitor prexasertib involves functionally distinct CHK1 activities in BRCA wild-type ovarian cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5520–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.J.; Wright, G.; Bryant, H.; Wiggins, L.A.; Schuler, M.; Gassman, N.R. EGFR signaling promotes resistance to CHK1 inhibitor prexasertib in triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2020, 3, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Nguyen, C.T.; Morita, K.I.; Miki, Y.; Kayamori, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sakamoto, K. THBS1 is induced by TGFB1 in the cancer stroma and promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, S.; Mahadik, P.; Shetty, O.; Sen, S. ECM stiffness-tuned exosomes drive breast cancer motility through thrombospondin-1. Biomaterials 2021, 279, 121185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocci, P.; Cianfrocca, R.; Sestito, R.; Rosano, L.; Di Castro, V.; Blandino, G.; Bagnato, A. Endothelin-1 axis fosters YAP-induced chemotherapy escape in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 492, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, L.; Cianfrocca, R.; Tocci, P.; Spinella, F.; Di Castro, V.; Caprara, V.; Semprucci, E.; Ferrandina, G.; Natali, P.G.; Bagnato, A. Endothelin A receptor/beta-arrestin signaling to the Wnt pathway renders ovarian cancer cells resistant to chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7453–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, N.J.; Bailey, M.L.; Hieter, P. Synthetic lethality and cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorecki, L.; Andrs, M.; Korabecny, J. Clinical Candidates Targeting the ATR-CHK1-WEE1 Axis in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbian, S. Cancer cell plasticity and therapeutic resistance: Mechanisms, crosstalk, and translational perspectives. Hereditas 2025, 162, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscetti, M.; Leibold, J.; Bott, M.J.; Fennell, M.; Kulick, A.; Salgado, N.R.; Chen, C.C.; Ho, Y.J.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Feucht, J.; et al. NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity contributes to tumor control by a cytostatic drug combination. Science 2018, 362, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipumuro, E.; Marco, E.; Christensen, C.L.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Zhang, T.; Hatheway, C.M.; Abraham, B.J.; Sharma, B.; Yeung, C.; Altabef, A.; et al. CDK7 inhibition suppresses super-enhancer-linked oncogenic transcription in MYCN-driven cancer. Cell 2014, 159, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahauad-Fernandez, W.D.; Yang, Y.C.; Lai, I.; Park, J.; Yao, L.; Evans, J.W.; Atibalentja, D.F.; Chen, X.; Kanakaveti, V.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Targeting the MYC oncogene with a selective bi-steric mTORC1 inhibitor elicits tumor regression in MYC-driven cancers. Cell Chem. Biol. 2025, 32, 994–1012.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, M.; D’Angelo, A.; De Logu, F.; Nassini, R.; Generali, D.; Roviello, G. Navigating Cancer Complexity: Integrative Multi-Omics Methodologies for Clinical Insights. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2025, 19, 11795549251384582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.