Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are endogenous, non-coding RNAs, which are derived from host genes that are present in several species and can be involved in the progression of various diseases. circRNAs’ leading role is to act as RNA sponges. In recent years, the other roles of circRNAs have been discovered, such as regulating transcription and translation, regulating host genes, and even being translated into proteins. As some tumor cells are no longer radiosensitive, tumor radioresistance has since become a challenge in treating tumors. In recent years, circRNAs are differentially expressed in tumor cells and can be used as biological markers of tumors. In addition, circRNAs can regulate the radiosensitivity of tumors. Here, we list the mechanisms of circRNAs in glioma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer; further, these studies also provide new ideas for the purposes of eliminating radioresistance in tumors.

1. Introduction

CircRNAs were first discovered, in 1976, in RNA viruses [1]. With the development of high-throughput RNA sequencing and bioinformatics tools, scientists have discovered that circRNAs are commonly found in humans and many other animals [2,3], including fungi, protozoa, plants, worms, fish, insects, and mammals [4]. CircRNAs are derived from host genes and are found primarily in the cytoplasm [5]. Similar to linear mRNAs, circRNAs are derived from linear precursor mRNAs (i.e., pre-mRNAs), which are transcribed by RNA polymerase II [6]—relying on canonical splicing machinery—including splice signal sites and spliceosomes [7]. Due to the lack of 5’ end cap or 3’ poly(A) tail, circRNAs are covalently closed endogenous biomolecules that fall into non-coding RNA (ncRNA) molecules [8]. The unique structure of circRNAs allow for a longer half-life and a more excellent resistance to RNase R than linear RNAs [9], making it a potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target [10].

For a long time, circRNAs were considered to be “non-coding” RNA with regulatory effects [11]. After the discovery of translatable circRNAs, attention again focused on this particular structure [12]. Increasingly, studies have identified additional functions for circRNAs, including acting as miRNA sponges [13] or protein scaffolds [2], as well as being translated into peptides [14]. Scientists have found that these RNAs have tissue-specific, cell-specific, and developmental stage-specific expression patterns [15]; further, circRNAs are also conserved across species.

Radiotherapy is one of the main methods of oncology treatment and is defined as the application of radiation to kill tumor cells or control their proliferation in clinical cancer treatment [16]. Through direct and indirect mechanisms, X-rays penetrate the tumor tissue and induce cytotoxic damage to proliferating cells [17]. The radiobiological phenomena are summarized as the “4Rs of radiotherapy”, i.e., repair, redistribution/recombination, repopulation, and reoxygenation, which are together the basis of fractionated radiotherapy [18]. These four phenomena are often extended by a fifth ‘R’, namely, intrinsic radioresistance, which is defined as radiation-induced initial DNA damage [19].

2. Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms of CircRNAs

2.1. Biogenesis of CircRNAs

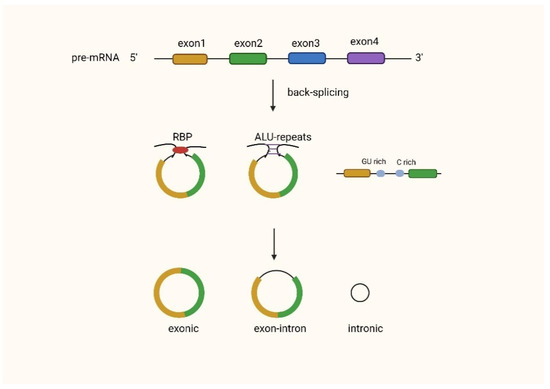

CircRNAs can be the main product generated from the host gene [15], for instance, the human cytochrome P450 gene, the rat androgen-binding protein (ABP) gene [20], the human dystrophin gene [21], and the human inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (INK4/ARF)-associated non-coding RNA [22]. CircRNAs can be classified as exonic circRNAs (ecircRNAs), intronic circRNAs (ciRNAs), or exon–intron circular RNAs (EIciRNAs). Most circRNAs are ecircRNAs, accounting for over 80% of known circRNAs [23], and they are mainly located in the cytoplasm [24,25], while EIcircRNAs and ciRNAs are usually found in the nucleus [26]. Exon-derived circRNAs are produced by a specific type of splicing known as post-snap [6]. Splice sites with specifically canonical splice sites accomplish post splicing [20,27]. In this type of splicing, the 5’ splice donor attacks the upstream 3’ splice site. This results in a 3’−5’phosphodiester bond that generates a circular RNA molecule [28]. There are also circRNAs that are formed by intron pairing, which are formed by the bringing of the splice donor site and the upstream splice acceptor site into proximity in order to form a loop via reverse complementary sequences, such as ALU repeats [29]. In the RNA-binding protein (RBP)-mediated model, the specific trans-activator RBP binds specifically to each flanking intron, forming a bridge that brings the splice donor and acceptor sites close enough to form a loop [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biogenesis of circRNAs.

2.2. Functions of CircRNAs

2.2.1. MiRNA Sponges

Acting as miRNA sponges is the most reported function of circRNAs [31]. The initial observation that some circRNAs have many miRNA binding sites led to speculation that these molecules may act as miRNA sponges [32]. MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that bind to target mRNAs and typically induce mRNA degradation or translational repression [33,34]. Many circRNAs have been found to bind miRNAs extensively, reducing their effectiveness, and thus upregulating the expression of their target mRNAs [35,36].

2.2.2. CircRNAs Regulate Transcription and Translation

CircRNAs can directly bind to their parental mRNAs, thereby affecting protein translation [6]. Competition for the RNA-binding protein HuR by circRNAs and their cognate mRNAs has also been reported to affect protein expression [37]. In addition, circRNAs can influence ribosome function and affect protein synthesis [38]. For example, inter-exon retained intronic circRNAs (exon–intron circRNAs and EIciRNAs) can bind to U1 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins via RNA–RNA interactions between snRNAs and EIciRNAs, and then interact with Pol II at the parental gene promoter in order to enhance their expression [26]. Similarly, cyclic intron RNA (ciRNAs) formed by detached unbranched lassoes can accumulate at their synthesis sites and increase the expression of the parental gene by regulating the prolonged Pol II activity [39].

2.2.3. CircRNAs Interact with Proteins

CircRNA–protein interactions are another vital function of circRNAs. RBP is a class of proteins associated with RNA metabolism. These proteins are involved in forming ribonucleoprotein complexes by mediating the maturation, translocation, localization, and translation of RNA [40]. It has been reported that RNA–protein interactions influence protein expression and function and regulate the synthesis and degradation of circRNAs [41]. Some CircRNAs have binding sites for proteins and can effectively act as protein sponges [42,43]. CircRNAs can also act as protein decoys, cooperating with target proteins at appropriate locations in the cell in order to alter the conventional physiological functions of the protein. In addition, circRNAs can act as scaffolds to facilitate contact between two or more proteins, promote co-localization of enzymes and their substrates, or facilitate nuclear translocation, thereby influencing the cell cycle [44]. It has also been suggested that circRNAs may recruit specific proteins to certain locations in the cell, although the exact mechanisms are still not understood [45].

2.2.4. Translation of CircRNAs into Proteins

CircRNAs were initially thought to be untranslatable. However, later studies have shown that circRNAs can be translated both in vitro and in vivo [46]. Studies of circRNA encoding proteins have shown that internal nuclear protein entry sites (IRES) and open reading frames (ORFs) are essential components of circRNA protein translation [47,48]. Due to the lack of 5’-cap and 3’-tail, circRNAs can only adopt a cap-independent approach [49]. The microproteins encoded by circRNAs are relatively short, ranging from 146–344 amino acids in length. Almost all circRNA-encoded proteins are found in metabolically active cells such as cancer cells or myogenic cells [50]. The translated proteins may also have some function in these cells, although the physiological processes of most of these proteins have not yet been determined [51].

2.2.5. Exosomal CircRNAs

Exosomes are 40–200 nm diameter structures with lipid bilayer membranes, and almost all cell types can secrete them [52,53]. Exosomes can contain various substances such as proteins, lipids, DNA, and RNA [54]. When released and transferred to recipient cells, they can participate in intercellular communication [55,56]. The presence of large and stable circRNAs in exosomes, and their assistance in the clearance of circRNAs, provides evidence for the degradation of circRNAs [57,58]. Researchers have recently found that extra circRNAs may be transported to immune cells as tumor antigens, activating anti-tumor immunity, or binding to miRNAs and proteins, thereby modulating immune cell activity. In addition, when exocircRNAs are transported from tumor cells to immune cells, they contribute to the release of miRNAs into immune cells, silencing relevant target genes as a result [59].

3. Research Progress of CircRNAs Related to Tumor Radioresistance

When tumor cells are genetically or phenotypically affected by radiation exposure, or protected from treatment by the tumor microenvironment, cancer cells begin to acquire resistance to radiation, resulting in a diminished effect of radiotherapy [60]. Many previous studies have been focused on enhancing sensitivity to radiotherapy, such as targeting DNA damage and repair, modulating growth factors, affecting tumor stem cells, and generating reactive oxygen species [61]. Here, we list dozens of reports on the role of circRNAs in tumor radioresistance (Table 1). According to these studies, circRNAs can regulate autophagy, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and function as exosomal circRNAs (Figure 2). By understanding the impact of circRNAs on tumor radioresistance, new therapeutic insights into tumors may be gained.

Table 1.

Alterations of circRNAs in radiotherapy resistance.

Figure 2.

The mechanism of circRNA in tumor radioresistance.

3.1. Glioma

Glioma originates from glial cells (precursors) and is one of the most common malignant tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) [89]. It has an incidence of about 5–10/100,000 in the population and has been increasing yearly in recent years [90,91]. The 5-year survival rate for the most common of gliomas, glioblastoma, is only about 5% [92]. Treatment of gliomas is primarily surgical resection, with radiation therapy routinely administered after surgery due to the tumors’ aggressive growth [93,94]. Most gliomas are insensitive to radiotherapy [95], and increasing the dose of X-rays can cause irreversible damage to normal glial cells [96]. Therefore, we need to gain insight into the molecular radiobiological mechanisms of glioma resistance to radiation, which is essential to improve the sensitivity of glioma radiotherapy and to reduce the damage to normal brain tissue.

Zhao et al. [62] found that circ-0008344 was highly expressed in radioresistant tissues and therefore hypothesized that circ-0008344 was associated with radioresistance in glioma. Downregulation of the circ-0008344 gene enhanced apoptosis, DNA damage, and the enhanced radiosensitivity of glioma. miR-433-3p could stimulate radiosensitivity of glioma cells; further, via target gene analysis of circ-0008344 and miR-433-3p, the results showed that circ-0008344 contains a binding site for miR-433-3p and exerts a sponge effect on miR-433-3p in glioma cells. In addition, RNF2 was identified as a downstream gene of miR-433-3p. Thus circ-0008344 was shown to increase RNF2 expression by acting as a miR-433-3p sponge. RNF2 overexpression rescued circ-0008344 downregulation of radiosensitivity to glioma cells. In a study by Zhu et al., downregulation of circ-VCAN inhibited proliferation, the migration and invasion of glioma cells, and enhanced apoptosis. Furthermore, circ-VCAN was negatively correlated with miR-1183 expression and circ-VCAN negatively regulated miR-1183 via direct binding. This implies that circ-VCAN accelerated proliferation, migration and invasion, and also inhibited the apoptosis of irradiated glioma cells via regulating miR-1183 [63].

CircRNAs can also influence tumor radioresistance by affecting glycolysis [64]. Glycolysis is a process that converts glucose to pyruvate and then to lactate, which provides cellular energy and participates in macromolecular biosynthesis [97]. Tumor cells, and even various normal cells, tend to exhibit a high rate of glycolysis, also called the “Wartburg effect,” regardless of oxygen availability [98]. The glycolytic process is usually accompanied by glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP production, which is an essential determinant of cellular drug resistance [97]. Guan et al. showed that circ-PITX1 expression was upregulated in glioma tissues and cells compared to normal tissues. Further, the lack of circ-PITX1 inhibited glioma cell viability, glycolysis, the ability to form radiation-resistant clones in vitro, and tumor growth in vivo—suggesting that circ-PITX1 is a positive regulator of glioma development. The expression of miR-329-3p was decreased in glioma samples compared to the control, and miR-329-3p expression was negatively correlated with circ-PITX1 in glioma samples, suggesting that the oncogenic effect of circ-PITX1 was achieved by sponging miR-329-3p. In the study of Guan et al., NEK2 was shown to be a direct target of miR-329-3p. A previous study also found that NEK2 was expressed and enriched in glioma. Further, miR-128 targeted to regulate apoptosis in glioma cells [99]. By introducing both the overexpression vector circ-PITX1 and the glycolysis inhibitor 2-DG into glioma cells, it was demonstrated that circ-PITX1 overexpression promoted the glycolytic process and radiation resistance, but 2-DG counteracted this promotion. It was shown that circ-PITX1 knockdown inhibited glycolysis and made glioma cells sensitive to radiation treatment.

In addition to affecting the radioresistance of gliomas, circRNAs can also influence the proliferation and invasion of gliomas through tumor-associated signaling pathways. Aberrantly expressed, circRNAs play an important role in glioma proliferation, cell cycle, invasion, and metastasis via regulating complementary miRNAs or targeting mRNA that are related to tumor-associated signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [100]. For example, the silencing of circ-ZNF292 inhibits glioma proliferation and cell cycle progression via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [101]. Circ-0014359 and circ-NT5E promote glioma progression via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway via miR-153 and miR-422a, respectively [102,103]. Therefore, understanding the cancer-related pathways regulated by circRNAs will also provide new therapeutic ideas for radiotherapy resistance in glioma.

3.2. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is an epithelial malignancy whose occurrence may be linked to viral, environmental, and genetic factors [104,105]. Nasopharyngeal cancer is endemic in Asian and North African populations. Most patients in China are found in southern regions, such as Guangdong and Guangxi [106]. Nasopharyngeal cancer has a high degree of malignancy, a high incidence of metastasis, early metastasis, and no obvious specific symptoms in the early stages. Most patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma do not seek treatment until the middle or late stages; further, this type of cancer has a low 5-year survival rate [107]. Although radiotherapy can improve the 5-year survival rate of patients with nasopharyngeal cancer, some patients may experience local recurrence and distant metastases after receiving radiotherapy due to the limitations of radioresistance [108].

In a study by Chen et al. [65], circRNA-000543 was highly expressed in radiation-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and radiation-resistant cell lines. Further studies found that circRNA-000543 downregulation promoted the sensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to radiotherapy. In addition, miR-9 expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues was negatively correlated with circRNA-000543 levels. They also confirmed that PDGFRB is a target of miR-9 in NPC. miR-9 is an important therapeutic target for cancer due to its involvement in angiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and metastasis. In this study, PDFGRB knockdown reversed miR-9 inhibitor-mediated irradiation resistance. Imatinib, a PDFGRB inhibitor used for CML treatment, sensitized radiation-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to irradiation. Pearson analysis showed that miR-9 levels were negatively correlated with circRNA-000543 and PDFGRB expression, while PDFGRB levels were positively correlated with circRNA-000543 expression. Therefore, circRNA-000543 knockdown could sensitize nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to radiation by targeting the miR-9/ PDGFRB axis.

In addition to circRNA-000543, circ-CCNB1 has also been shown to be associated with EMT [109]. Circ-CCNB1 inhibits migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by promoting binding between NF90 and TJP1 mRNA, stabilizing TJP1 mRNA, and enhancing tight junctions between tumor cells. TJP1 is a key regulator of tight junction assembly and inhibits migration and invasion by coordinating the assembly or dynamics of the cortical cytoskeleton to regulate the function [110]. By revealing the mechanism by which circ-CCNB1 regulates the migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it may provide a potential marker and target for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

3.3. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) includes squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma. It accounts for about 80% or more of all primary lung cancer cases [111,112,113]. Most patients are diagnosed with advanced tumors and have a 5-year survival rate of less than 20% [114]. Radiotherapy is currently the primary method of non-surgical treatment for NSCLC. Radiotherapy damages the DNA of tumor cells and causes cell death [115]. However, the effectiveness of radiotherapy is limited during therapy due to the tumors’ acquired radioresistance, resulting in a poor prognosis [116,117].

Zhang et al. [68] demonstrated by luciferase reporter gene assay, RIP assay, and qRT-PCR that circ-0001287 sponges miR-21 and negatively regulates its expression. MiR-21 is considered an oncogene in many cancers, enhances cell proliferation, metastasis, and radiation resistance, and inhibits apoptosis in NSCLC cells [118,119]. MiR-21 is one of the most critical regulators of PTEN expression [120,121]. The PI3K signaling pathway is one of the most critical pathways in tumor biology, regulating cell cycle progression, survival, migration, invasion, and tumor cell metabolism. PTEN is its primary negative regulator, which it achieves via dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2. PTEN also acts as a protein phosphatase regulating chromosome stability, DNA repair, and apoptosis [122,123]. Circ-0001287 sponge miR-21, in turn, upregulates PTEN expression and inhibits NSCLC cell proliferation, metastasis, and radiation resistance.

Kim et al. [69] also validated the mode of action of one of the circRNA–miRNA–mRNA networks in the progression of NSCLC. They explored the role of circ-0086720 in NSCLC cells after radiotherapy and found that downregulation of circ-0086720 gene enhanced radiosensitivity, further impaired cell survival, and induced apoptosis. It was also demonstrated that miR-375, a target of circ-008672, was reduced in expression in radiation-resistant NSCLC tissues. Further analysis revealed that the word of SPIN1 in NSCLC cells decreased after circ-0086720 knockdown, while the reintroduction of miR-375 inhibitor increased the expression of SPIN1.

Immune escape in NSCLC cells has also been associated with circRNAs. PD1 is a negative costimulatory receptor that plays a crucial role in suppressing T cell activation in vitro and in vivo [124]. For example, circIGF2BP3 alleviates the inhibitory effect of miR-328-3p and miR-3173-5p on PKP3 expression, which is achieved by acting as a miRNA sponge. Additionally, PKP3 stabilizes PD-L1 in an otub1-dependent manner. The circIGF2BP3/PKP3 axis is ultimately involved in the immune escape of NSCLC cells by upregulating PD-L1 expression [125]. Increased expression of circ-USP7 reduced the efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy through the exosomal circUSP7/miR-934/SHP2 axis [126]. These studies suggest that circRNAs may not only be used as tumor markers, but may also influence the critical factors that are present in treating patients with NSCLC.

3.4. Colon Cancer and Colorectal Cancer

Both colon and colorectal cancers are the most common digestive system malignancies and pose a heavy burden on human health worldwide [127]. Unhealthy dietary patterns and genetic factors are considered to be risk factors for the development of colon cancer and colorectal cancer [128]. Further, because early symptoms are not obvious, most patients are already at an advanced stage at diagnosis [129]. Radiotherapy is one of the main options for treating colorectal cancer—alone or in combination with surgery and chemotherapy [130,131]. Unfortunately, the resistance of cancer cells to radiation still limits the effectiveness of radiotherapy. Several factors—for example, dysregulated radiosensitivity-related gene expression—are known to affect cellar radiosensitivity [132]. There is growing evidence that circRNAs play an increasingly important role in regulating radiation response [133].

Gao et al. [72] showed that circ-0055625 expression was significantly upregulated in colon cancer tissues and that down-regulation of the circ-0055625 gene inhibited cell proliferation, migration, and invasive ability. MSI1 has been shown to have a role in the development of colon cancer [134]. MSI1 expression was significantly upregulated in colon cancer tissues and cells and increased in colon cancer cells following radiotherapy. In addition, MSI1 overexpression attenuated the effect of circ-0055625’s deletion on colon cancer tumor development and radiosensitivity. This evidence suggests that downregulation of the circ-0055625 gene inhibits colon carcinogenesis’ development and increases the sensitivity of colon cancer to IR by regulating MSI1. Further, miR-338-3p, a tumor suppressor, promotes radiosensitivity in colon cancer. The data showed circ-0055625 was associated with miR-338-3p and miR-338-3p binding to MSI1. Furthermore, the results explain that deletion of circ_0055625 down-regulates MSI1 expression by binding to miR-338-3p. In another study on colon cancer [73], knockdown of circ-CCDC66 also improved the radiosensitivity of colon cells by upregulating miR-338-3p expression, providing a potential therapeutic target for patients with radioresistant colon cancer.

The transmission of circRNA is usually achieved via exosomes [135]. Exosomal information of circRNA is involved in the development of carcinogenesis and radioresistance in humans [75,136]. Circ-0067835 can be transmitted via exosomes, and upregulation of circ-0067835 is associated with CRC development and radioresistance. Wang et al. demonstrated that circ-0067835 directly targets miR-296-45p and that by upregulating miR-296-5p, knockdown of circ-0067835 inhibited CRC development and enhanced cellular radiosensitivity in vitro. The data first show that miR-296-5p directly targets IFG1R, a transmembrane receptor belonging to the tyrosine kinase family [137,138]. In addition to circ-0067835, circ_MFN2 is also a circRNA upregulated in CRC [76]. Circ-MFN2 can promote proliferation, metastasis, and radiation resistance in CRC by regulating the miR-574-3p/IGF1R axis, suggesting that circ-MFN2 may be an oncogene in CRC.

Some cancer-related signaling pathways can be regulated by circRNA-encoded proteins, which is unexpected. Further, circPPP1R12A is expressed at an increased rate in colon cancer. But it is not circPPP1R12A that actually promotes the growth and metastasis of colon cancer cells, but circPPP1R12A-73aa, a short peptide chain encoded by circPPP1R12A. PPPP1R12A is primarily involved in the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway, which regulates cell adhesion, motility, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [139].

3.5. Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the world and the sixth most common cause of cancer death [140]. Current treatment for esophageal cancer includes surgery, radiotherapy, as well as chemotherapy and their combinations [141]. However, due to the aggressive nature of esophageal cancer and the lack of early diagnostic markers, patients’ prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of only about 20% [142]. Radiotherapy plays a crucial role in treating esophageal cancer, and resistance to radiotherapy is thought to be a significant cause of treatment failure and local tumor recurrence [143]. Therefore, it is essential to explore the molecular mechanisms of radiotherapy resistance in order to improve the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer.

High expression of circRNA-100367 was associated with the radiosensitivity of ESCC. Silencing circRNA-100367 reduced proliferation and migration of KYSE-150R cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in vivo. In addition, miR-217/Wnt3 was shown to be a downstream target of circRNA-100367 regulating radiosensitivity of ESCC. Wnt3, a member of the Wnt family, has been shown to promote the stabilization of β-catenin and regulate the radiosensitivity of cancer cells [144]. By silencing Wnt3, Liu et al. altered the phenotype of KYSE-150R cells and inhibited colony formation and migration of KYSE-150R cells, suggesting that Wnt3 could inhibit the radiosensitivity of ESCC cells.

In the study by He et al. [82], overexpression of circ-VRK1 effectively attenuated ESCC proliferation, migration, and EMT processes. Based on RIP and luciferase reporter gene assays, miR-624-3p interacted with circVRK1. Further analysis revealed that circ-VRK1 enhanced the expression of PTEN, a suppressor of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, through the sponge uptake of miR-624-3p [145,146]. Western blotting showed that circ-VRK1 overexpression increased PTEN levels and decreased p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR levels. The results suggest that circ-VRK1 inhibits the progression and radiation resistance of ESCC by upregulating PTEN to reduce PI3K/AKT signaling pathway activity.

CircRNA can also regulate the progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in many other ways. Miyagi et al. (101) demonstrated that circ-PUM1, a nuclear genomic-derived circRNA localized to mitochondria, responds to induction of HIF1α protein levels and increases with the accumulation of HIF1α in CoCl2-treated cells. Further, circ-PUM1 may act as a scaffolding protein for mitochondrial complex III assembly and regulates mitochondrial oxidation through the interaction with UQCRC2 phosphorylation. In addition, circ-PUM1 may promote tumor growth by inhibiting focal degeneration in ESCC cells. This suggests that knocking down certain circRNAs may reduce radioresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

3.6. Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is second only to lung cancer in men, with a high prevalence of 13.5% [127]. Radiation therapy has made exciting breakthroughs in prostate cancer metastasis and post-operative repair [147]. An in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of radioresistance in prostate cancer may help to treat recurrent prostate cancer and interrupt its metastasis [148].

Circ-CCNB2 is overexpressed in irradiation-resistant PCa tissues and cells [85]. Knockdown of circ-CCNB2 suppressed colony formation and metastasis, and also promoted apoptosis in irradiation-resistant PCa cells. Autophagy is a cellular process that regulates cell signaling and maintains endocytosis [149], and the regulation of autophagy is closely related to the radiosensitivity of cancer cells [150]. Cai et al. found a facilitatory effect of autophagy after detecting the associated proteins in radiation-resistant PCa tissues and cells, suggesting that autophagy may induce the formation of radiation resistance in PCa. They then found that the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA restored the pro-tumor effects of circ-CCNB2 overexpression on irradiation-resistant PCa cells, demonstrating the role of circ-CCNB2 in regulating the radiosensitivity of PCa, and which was attributed to autophagy. Furthermore, they determined that circ-CCNB2 regulates radiosensitivity by targeting miR-30b-5p. KIF18A, a downstream target of miR-30b-5p, is an oncogene that promotes the growth and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells [151,152]. Thus, KIF18A can abrogate the inhibitory effects of miR-30b-5p on cell growth, metastasis and autophagy, suggesting that KIF18A also plays a pro-tumor role in irradiation-tolerant PCa cells. Furthermore, miR-30b-5p targeting KIF18A promoted PCa radiosensitivity by blocking autophagy. Taken together, circ-CCNB2 can bind to miR-30b-5p to affect KIF18A expression and regulate PCa radiosensitivity.

3.7. Materials and Methods Used in CircRNA Studies

In these studies, samples were obtained from patients. All mediums contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and all cells were incubated at 37 °C with a 5% CO2 incubator. Then, cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen).

After the isolation of total RNA from tissues and cells by TRIzolTM Reagent (Invitrogen), cDNA was synthesized using cDNA Synthesis SuperMix. Quantitative analysis was carried out using SYBR Green on Real-Time PCR System in order to detect the circRNA expression. After transfection and treatment with X-ray irradiation was conducted for respective 0 min, 1 min, 2 min, and 4 min (0 Gy, 2 Gy, 4 Gy and 8 Gy), count; further, the colonies were counted under a microscope. Flow cytometry was performed to measure the cell cycle distribution and apoptosis of cells. Western blot was conducted for protein expression analysis. Construction of the luciferase plasmids was implemented by cloning the wild-type (WT) and mutant-type (MUT) sequences of circRNA into the vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), after which the relative luciferase activity was measured using the dual-luciferase reporter system (Promega).

4. Conclusions

In the study of human cancer, the interactions between different RNAs are quite complex [153].

One circRNA can suppress the expression levels of different miRNAs and thus affect the expression and function of mRNAs. For example, in addition to regulating tumor resistance by sponging miR-329-3p [64], circPITX1 can also regulate ERBB4 expression by sponging miR-1304, thus promoting glioma progression [154]. In addition, circPITX1 promotes glioblastoma evolution by regulating MAP3K2 as a competitive endogenous RNA through the uptake of miR-379-5p [155].

A circRNA can act in different tumors. Knockdown of circ-0086720 enhances the radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells [69]. At the same time, circ-0086720 is highly expressed in radiation-resistant esophageal cancer cells [156], suggesting that circ_0086720 may play an important role in the radiation resistance of esophageal cancer. Circ-PVT1 has been reported as a proliferative factor in many cancers, such as gastric [157], colorectal [158], and esophageal [159] cancers. In gastric cancer (GC), circ-PVT1 downregulation impaired chemotherapy resistance to paclitaxel [160]. In lung adenocarcinoma, circ-PVT1 overexpression is involved in chemoresistance through the miR-145-5p/ABCC1 axis [161].

In conclusion, circRNAs can affect the proliferation, migration, and invasion of irradiated tumor cells and inhibit apoptosis through multiple pathways. It provides a new idea to attenuate the radioresistance of tumor cells.

5. Discussion and Prospects

Radiation therapy developed rapidly following Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays, Becquerel’s discovery of natural radioactivity, and Curie’s discovery of radium. Currently, radiotherapy is one of the main methods of treating cancer [17]. However, tumor radioresistance remains a crucial barrier to treatment outcomes.

Biomarkers can be used to aid cancer diagnosis, determine prognosis, and monitor progression. In general, biomarkers should have good sensitivity, specificity, and stability [162]. Further, circRNAs are expressed explicitly in tissues while being structurally stable [6]. In addition, circRNAs are enriched in human body fluids such as saliva [163] and blood, making them easy to detect, and these characteristics make circRNAs ideal as biomarkers. Most of the circRNAs we mentioned are highly expressed in tumor cells and are also associated with radioresistance of tumors, which means that circRNAs can be used not only as diagnostic biomarkers, but also as biomarkers for determining prognosis.

CircRNAs hold promise as therapeutic targets through circRNA loss-of-function therapy or circRNA gain-of-function therapy. Antisense technologies can be used to inhibit or degrade oncogenic circRNAs selectively. For example, complementary single-stranded DNA antisense oligonucleotides can be designed and annealed to a unique sequence in the targeted circRNA. Targeted cleavage of its site by intracellular RNaseH enzymes or RNA interference (RNAi) methods to induce cleavage of circRNAs [164], techniques that target circRNAs for disruption has been used to treat diseases other than tumors [165]. However, the challenges of delivering circRNAs to cells are a major clinical implementation obstacle [166]. These seem to explain why most studies have targeted up-regulated circRNAs rather than down-regulated circRNAs.

In particular, the articles we have summarized, circRNAs generally act as miRNA sponges [13]. Although the role of circRNAs as miRNA sponges is well established, other potential functions of circRNAs in radiation therapy require further investigation [14]. For circRNAs, studying the process of a group of significantly differentiated circRNAs or individual circRNAs and examining their potential targets could reveal more about the role of circRNAs in cancer progression. Furthermore, most reports on the part of circRNAs in tumor resistance to radiotherapy have been limited to a small number of cancers. In recent years, ferroptosis has been proposed and could also be used as a new way of thinking about treatment. Although research on circRNAs modulating tumor radiotherapy resistance is still in its infancy, we believe circRNAs can provide fresh ideas for tumor radiotherapy.

Author Contributions

C.Z. and Y.G. conceived, wrote, and revised this manuscript; F.L. and T.W. collected materials; S.H., J.G., J.W. as well as Q.Z. collected materials and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [the National Natural Science Foundation of China] grant number [81872557] and [science and technology projects in Guangzhou] grant number [202201011800].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81872557). Additionally, funding was also provided by science and technology projects in Guangzhou (grant no. 202201011800).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Sanger, H.L.; Klotz, G.; Riesner, D.; Gross, H.J.; Kleinschmidt, A.K. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3852–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.L. The expanding regulatory mechanisms and cellular functions of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, L.; Salzman, J. Detecting circular RNAs: Bioinformatic and experimental challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzman, J.; Gawad, C.; Wang, P.L.; Lacayo, N.; Brown, P.O. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, J.M.; Cho, K.R.; Fearon, E.R.; Kern, S.E.; Ruppert, J.M.; Oliner, J.D.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Scrambled exons. Cell 1991, 64, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwal-Fluss, R.; Meyer, M.; Pamudurti, N.R.; Ivanov, A.; Bartok, O.; Hanan, M.; Evantal, N.; Memczak, S.; Rajewsky, N.; Kadener, S. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, S.; Jost, I.; Rossbach, O.; Schneider, T.; Schreiner, S.; Hung, L.H.; Bindereif, A. Exon circularization requires canonical splice signals. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, K.; Egan, E. Non-coding RNA: More uses for genomic junk. Nature 2017, 543, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeck, W.R.; Sharpless, N.E. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Gao, Y.; Dong, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, X.; Yin, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, K.; et al. CircRNA inhibits DNA damage repair by interacting with host gene. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S.; Jens, M.; Elefsinioti, A.; Torti, F.; Krueger, J.; Rybak, A.; Maier, L.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Gregersen, L.H.; Munschauer, M.; et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013, 495, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perriman, R.; Ares, M., Jr. Circular mRNA can direct translation of extremely long repeating-sequence proteins in vivo. RNA 1998, 4, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.S.; Ai, Y.; Wilusz, J.E. Biogenesis and Functions of Circular RNAs Come into Focus. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patop, I.L.; Wüst, S.; Kadener, S. Past, present, and future of circRNAs. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghotra, V.P.; Geldof, A.A.; Danen, E.H. Targeted radiosensitization in prostate cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mu, X.; He, H.; Zhang, X.D. Cancer Radiosensitizers. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, E.B.; Formenti, S.C. Is tumor (R)ejection by the immune system the “5th R” of radiobiology? Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e28133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.G.; McMillan, T.J.; Peacock, J.H. The 5Rs of radiobiology. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1989, 56, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaphiropoulos, P.G. Exon skipping and circular RNA formation in transcripts of the human cytochrome P-450 2C18 gene in epidermis and of the rat androgen binding protein gene in testis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997, 17, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surono, A.; Takeshima, Y.; Wibawa, T.; Ikezawa, M.; Nonaka, I.; Matsuo, M. Circular dystrophin RNAs consisting of exons that were skipped by alternative splicing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burd, C.E.; Jeck, W.R.; Liu, Y.; Sanoff, H.K.; Wang, Z.; Sharpless, N.E. Expression of linear and novel circular forms of an INK4/ARF-associated non-coding RNA correlates with atherosclerosis risk. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiou, M. Circular RNAs as Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1134, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeck, W.R.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Wang, K.; Slevin, M.K.; Burd, C.E.; Liu, J.; Marzluff, W.F.; Sharpless, N.E. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 2013, 19, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.O.; Chen, T.; Xiang, J.F.; Yin, Q.F.; Xing, Y.H.; Zhu, S.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.L. Circular intronic long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Bao, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, M.; Wang, X.; Zhong, G.; Yu, B.; Hu, W.; Dai, L.; et al. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, B.; Swain, A.; Nicolis, S.; Hacker, A.; Walter, M.; Koopman, P.; Goodfellow, P.; Lovell-Badge, R. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell 1993, 73, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.L.; Bao, Y.; Yee, M.C.; Barrett, S.P.; Hogan, G.J.; Olsen, M.N.; Dinneny, J.R.; Brown, P.O.; Salzman, J. Circular RNA is expressed across the eukaryotic tree of life. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmayr-Heyda, A.; Reiner, A.T.; Auer, K.; Sukhbaatar, N.; Aust, S.; Bachleitner-Hofmann, T.; Mesteri, I.; Grunt, T.W.; Zeillinger, R.; Pils, D. Correlation of circular RNA abundance with proliferation—exemplified with colorectal and ovarian cancer, idiopathic lung fibrosis, and normal human tissues. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, S.J.; Pillman, K.A.; Toubia, J.; Conn, V.M.; Salmanidis, M.; Phillips, C.A.; Roslan, S.; Schreiber, A.W.; Gregory, P.A.; Goodall, G.J. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell 2015, 160, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, C.; Sun, R.; Yang, D.; Liu, Q. Circular Noncoding RNA NR3C1 Acts as a miR-382-5p Sponge to Protect RPE Functions via Regulating PTEN/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Qin, C.; Li, D.; Zhao, W.; Nie, L.; Cao, J.; Guo, J.; Zhong, T.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; et al. A Novel Long Noncoding RNA, lncR-125b, Promotes the Differentiation of Goat Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells by Sponging miR-125b. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, K.T.; Okolicsanyi, R.K.; Haupt, L.M.; Griffiths, L.R. A combinatorial in silico approach for microRNA-target identification: Order out of chaos. Biochimie 2021, 187, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.P.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 2005, 120, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018, 173, 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Panda, A.C.; Munk, R.; Grammatikakis, I.; Dudekula, D.B.; De, S.; Kim, J.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Martindale, J.L.; et al. Identification of HuR target circular RNAs uncovers suppression of PABPN1 translation by CircPABPN1. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, L.M.; Stahringer, A.; Sass, K.; Pichler, G.; Kulak, N.A.; Wilfert, W.; Kohlmaier, A.; Herbst, A.; Northoff, B.H.; Nicolaou, A.; et al. Circular non-coding RNA ANRIL modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, E.G.; Manley, J.L. RNA-binding proteins in neurodegeneration: Mechanisms in aggregate. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.G.; Awan, F.M.; Du, W.W.; Zeng, Y.; Lyu, J.; Wu, D.; Gupta, S.; Yang, W.; Yang, B.B. The Circular RNA Interacts with STAT3, Increasing Its Nuclear Translocation and Wound Repair by Modulating Dnmt3a and miR-17 Function. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2062–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Du, W.W.; Wu, N.; Yang, W.; Awan, F.M.; Fang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. A circular RNA promotes tumorigenesis by inducing c-myc nuclear translocation. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armakola, M.; Higgins, M.J.; Figley, M.D.; Barmada, S.J.; Scarborough, E.A.; Diaz, Z.; Fang, X.; Shorter, J.; Krogan, N.J.; Finkbeiner, S.; et al. Inhibition of RNA lariat debranching enzyme suppresses TDP-43 toxicity in ALS disease models. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Du, W.W.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Awan, F.M.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Q.; Yee, A.; et al. A Circular RNA Binds To and Activates AKT Phosphorylation and Nuclear Localization Reducing Apoptosis and Enhancing Cardiac Repair. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3842–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhao, G.; Yan, X.; Lv, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Du, Z.; et al. A novel FLI1 exonic circular RNA promotes metastasis in breast cancer by coordinately regulating TET1 and DNMT1. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, N.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishihara, M.; Nakano, Y.; Shibata, A.; Maruyama, H.; Shuto, S.; Matsuda, A.; Yoshida, M.; Ito, Y.; et al. Rolling Circle Translation of Circular RNA in Living Human Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Meng, N.; He, Y.; Lu, R.; Yan, G.R. ncRNA-Encoded Peptides or Proteins and Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, N.; Yang, X.; Luo, J.; Yan, S.; Xiao, F.; Chen, W.; Gao, X.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, H.; et al. A novel protein encoded by the circular form of the SHPRH gene suppresses glioma tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Timoteo, G.; Dattilo, D.; Centrón-Broco, A.; Colantoni, A.; Guarnacci, M.; Rossi, F.; Incarnato, D.; Oliviero, S.; Fatica, A.; Morlando, M.; et al. Modulation of circRNA Metabolism by m(6)A Modification. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft, R.A.; Kowalski, P.S.; Anderson, D.G. Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, M.; Yan, S.; Sun, C.; Xiao, F.; Huang, N.; Yang, X.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, H.; et al. Novel Role of FBXW7 Circular RNA in Repressing Glioma Tumorigenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; El Andaloussi, S.; Wood, M.J. Exosomes and microvesicles: Extracellular vesicles for genetic information transfer and gene therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, R125–R134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.; Im, H.; Castro, C.M.; Breakefield, X.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. New Technologies for Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1917–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaj, L.; Lessard, R.; Dai, L.; Cho, Y.J.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J. Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetta, C.; Ghigo, E.; Silengo, L.; Deregibus, M.C.; Camussi, G. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Endocrine 2013, 44, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; Wu, P.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; et al. Exosomal circRNAs: Biogenesis, effect and application in human diseases. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Bao, C.; Li, S.; Guo, W.; Zhao, J.; Chen, D.; Gu, J.; He, X.; Huang, S. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: A promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, P.; Peng, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Liu, H.; Bi, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Circular RNA IARS (circ-IARS) secreted by pancreatic cancer cells and located within exosomes regulates endothelial monolayer permeability to promote tumor metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, P.; Fan, L.; Wu, M. The Potential Role of circRNA in Tumor Immunity Regulation and Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meads, M.B.; Gatenby, R.A.; Dalton, W.S. Environment-mediated drug resistance: A major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaue, D.; McBride, W.H. Opportunities and challenges of radiotherapy for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L.; Zhao, X.; Ding, J. Knockdown of circ_0008344 contributes to radiosensitization in glioma via miR-433-3p/RNF2 axis. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Mao, X.; Zhao, H. The circ_VCAN with radioresistance contributes to the carcinogenesis of glioma by regulating microRNA-1183. Medicine 2020, 99, e19171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Cao, Z.; Du, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, T. Circular RNA circPITX1 knockdown inhibits glycolysis to enhance radiosensitivity of glioma cells by miR-329-3p/NEK2 axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Guan, Z. CircRNA_000543 knockdown sensitizes nasopharyngeal carcinoma to irradiation by targeting miR-9/platelet-derived growth factor receptor B axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 512, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, M.; Huang, L. High Expression of hsa_circRNA_001387 in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma and the Effect on Efficacy of Radiotherapy. Onco. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 3965–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, M.; Hong, J.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y. Upregulation of circRNA_0000285 serves as a prognostic biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma and is involved in radiosensitivity. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 6495–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.C.; Li, Y.; Feng, X.Z.; Li, D.B. Circular RNA circ_0001287 inhibits the proliferation, metastasis, and radiosensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging microRNA miR-21 and up-regulating phosphatase and tensin homolog expression. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Su, Z.; Sheng, H.; Li, K.; Yang, B.; Li, S. Circ_0086720 knockdown strengthens the radiosensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer via mediating the miR-375/SPIN1 axis. Neoplasma 2021, 68, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Deng, S.; Lv, Z.; He, Y.; Hou, B.; Zhu, G. Silencing circPVT1 enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer by sponging microRNA-1208. Cancer Biomark. 2021, 31, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Chen, W.; Kuang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, L.; Yu, B.; Jin, X.; et al. CircZNF208 enhances the sensitivity to X-rays instead of carbon-ions through the miR-7-5p /SNCA signal axis in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2021, 84, 110012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Han, C.; Wang, L.; Ding, B.; Tian, H.; Zhou, C.; Ju, Y.; Peng, A.; et al. Circ_0055625 knockdown inhibits tumorigenesis and improves radiosensitivity by regulating miR-338-3p/MSI1 axis in colon cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Peng, X.; Lu, X.; Wei, Q.; Chen, M.; Liu, L. Inhibition of hsa_circ_0001313 (circCCDC66) induction enhances the radio-sensitivity of colon cancer cells via tumor suppressor miR-338-3p: Effects of cicr_0001313 on colon cancer radio-sensitivity. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Gu, X. Circ_0007031 Serves as a Sponge of miR-760 to Regulate the Growth and Chemoradiotherapy Resistance of Colorectal Cancer via Regulating DCP1A. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8465–8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Circ_0067835 Knockdown Enhances the Radiosensitivity of Colorectal Cancer by miR-296-5p/IGF1R Axis. Onco. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Peng, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, T. Circ-MFN2 Positively Regulates the Proliferation, Metastasis, and Radioresistance of Colorectal Cancer by Regulating the miR-574-3p/IGF1R Signaling Axis. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 671337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, J.; Lin, L. Circ-ACAP2 facilitates the progression of colorectal cancer through mediating miR-143-3p/FZD4 axis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Jin, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, P.; Chen, W.; Li, Q. CircRNA CBL.11 suppresses cell proliferation by sponging miR-6778-5p in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zou, X.; Hao, T. Exosomal circ_IFT80 Enhances Tumorigenesis and Suppresses Radiosensitivity in Colorectal Cancer by Regulating miR-296-5p/MSI1 Axis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 1929–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, H.; Li, P.; Zhao, W.; Yang, X.; Xing, X.; Li, S.; Li, J. Circular RNA PRKCI silencing represses esophageal cancer progression and elevates cell radiosensitivity through regulating the miR-186-5p/PARP9 axis. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, R.; Lin, Y. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0000554 promotes progression and elevates radioresistance through the miR-485-5p/fermitin family members 1 axis in esophageal cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2021, 32, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Mingyan, E.; Wang, C.; Liu, G.; Shi, M.; Liu, S. CircVRK1 regulates tumor progression and radioresistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating miR-624-3p/PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, X.; Wen, L.; You, C.; Jin, X.; Liu, J. Hsa_circ_0014879 regulates the radiosensitivity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through miR-519-3p/CDC25A axis. Anticancer Drugs 2022, 33, e349–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhi, Y.; Ma, C.; Shen, Q.; Sun, F.; Cai, C. Circ_0062020 Knockdown Strengthens the Radiosensitivity of Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 11701–11712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S. Knockdown of Circ_CCNB2 Sensitizes Prostate Cancer to Radiation Through Repressing Autophagy by the miR-30b-5p/KIF18A Axis. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2020, 37, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Zhang, P.; Ren, W.; Yang, F.; Du, C. Circ-ZNF609 Accelerates the Radioresistance of Prostate Cancer Cells by Promoting the Glycolytic Metabolism Through miR-501-3p/HK2 Axis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 7487–7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Dong, W.; Luo, G.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, F. Silencing of hsa_circ_0009035 Suppresses Cervical Cancer Progression and Enhances Radiosensitivity through MicroRNA 889-3p-Dependent Regulation of HOXB7. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 41, e0063120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhong, R.; Deng, C.; Zhou, Z. Circle RNA circABCB10 Modulates PFN2 to Promote Breast Cancer Progression, as Well as Aggravate Radioresistance Through Facilitating Glycolytic Metabolism Via miR-223-3p. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2021, 36, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenting, K.; Verhaak, R.; Ter Laan, M.; Wesseling, P.; Leenders, W. Glioma: Experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A.; Burford, A.; Carvalho, D.; Izquierdo, E.; Fazal-Salom, J.; Taylor, K.R.; Bjerke, L.; Clarke, M.; Vinci, M.; Nandhabalan, M.; et al. Integrated Molecular Meta-Analysis of 1,000 Pediatric High-Grade and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 520–537.e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.K.; Hansen, S.; Laursen, R.J.; Kosteljanetz, M.; Schultz, H.; Nørgård, B.M.; Guldberg, R.; Gradel, K.O. Epidemiology of glioma: Clinical characteristics, symptoms, and predictors of glioma patients grade I-IV in the the Danish Neuro-Oncology Registry. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 135, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Bauchet, L.; Davis, F.G.; Deltour, I.; Fisher, J.L.; Langer, C.E.; Pekmezci, M.; Schwartzbaum, J.A.; Turner, M.C.; Walsh, K.M.; et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: A “state of the science” review. Neuro. Oncol. 2014, 16, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, V.M.; Phan, K.; Rovin, R.A. Comparison of operative outcomes of eloquent glioma resection performed under awake versus general anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 169, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.P.; Liew, B.S.; Idris, Z.; Rosman, A.K. Fluorescence-Guided versus Conventional Surgical Resection of High Grade Glioma: A Single-Centre, 7-Year, Comparative Effectiveness Study. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, N.; Yagi, K.; Ding, G.R.; Miyakoshi, J. Radiosensitization by overexpression of the nonphosphorylation form of IkappaB-alpha in human glioma cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2002, 43, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miyauchi, J.T.; Tsirka, S.E. Advances in immunotherapeutic research for glioma therapy. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy-Kanniappan, S.; Geschwind, J.F. Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and prospects. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, T.; Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.S. The Warburg effect as an adaptation of cancer cells to rapid fluctuations in energy demand. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhi, F.; Peng, Y.; Yang, C.C. MiR-128 promotes the apoptosis of glioma cells via binding to NEK2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 8781–8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, B.; Shu, C.; Ma, Q.; Wang, J. Functions and clinical significance of circular RNAs in glioma. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Qiu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, L.; Yang, W.; Gu, C.; Li, G.; Zhu, Y. Silencing of cZNF292 circular RNA suppresses human glioma tube formation via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63449–63455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Jia, R.; Pan, Y.; Liang, H. CircNT5E Acts as a Sponge of miR-422a to Promote Glioblastoma Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4812–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, J. CircRNA hsa-circ-0014359 promotes glioma progression by regulating miR-153/PI3K signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 510, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, J.P.; Yip, K.; Bratman, S.V.; Ito, E.; Liu, F.F. Nasopharyngeal Cancer: Molecular Landscape. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3346–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Luo, W.; Li, J.; Duan, L.; Zhu, Y.S.; Luo, D.X. The role of long non-coding RNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: As systemic review. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 16075–16083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C.W.; Hui, E.P.; Lo, K.W.; Lam, W.K.J.; Johnson, D.; Li, L.; Tao, Q.; Chan, K.C.A.; To, K.F.; King, A.D.; et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawira, A.; Oosting, S.F.; Chen, T.W.; Delos Santos, K.A.; Saluja, R.; Wang, L.; Siu, L.L.; Chan, K.K.W.; Hansen, A.R. Systemic therapies for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic review. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.N.; Xiao, T.; Yi, H.M.; Zheng, Z.; Qu, J.Q.; Huang, W.; Ye, X.; Yi, H.; Lu, S.S.; Li, X.H.; et al. Retraction: MiR-125b Increases Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Radioresistance By Targeting A20/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Tan, F.; Liu, L.; Hou, X.; Fan, C.; Tang, L.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Q.; et al. Circular RNA circCCNB1 inhibits the migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through binding and stabilizing TJP1 mRNA. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, J.; Roghi, C.S.; Hurtz, M.; Knäuper, V.; Edwards, D.R.; Poghosyan, Z. ADAM15 mediates upregulation of Claudin-1 expression in breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.P.; Chuang, H.C.; Lee, M.C.; Tsou, H.H.; Lee, L.W.; Li, J.P.; Tan, T.H. GLK/MAP4K3 overexpression associates with recurrence risk for non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41748–41757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Karedath, T.; Andrews, S.S.; Al-Azwani, I.K.; Mohamoud, Y.A.; Querleu, D.; Rafii, A.; Malek, J.A. Altered expression pattern of circular RNAs in primary and metastatic sites of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 36366–36381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howington, J.A.; Blum, M.G.; Chang, A.C.; Balekian, A.A.; Murthy, S.C. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013, 143, e278S–e313S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Tang, C.; Cong, H.; Wang, X.; Shen, X.; Ju, S. Diminished LINC00173 expression induced miR-182-5p accumulation promotes cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis inhibition via AGER/NF-κB pathway in non-small-cell lung cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 4248–4262. [Google Scholar]

- Willers, H.; Azzoli, C.G.; Santivasi, W.L.; Xia, F. Basic mechanisms of therapeutic resistance to radiation and chemotherapy in lung cancer. Cancer J. 2013, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, N.; Santana-Davila, R.; Molina, J.R. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péchoux, C.L.; Mercier, O.; Belemsagha, D.; Bouaita, R.; Besse, B.; Fadel, E. Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. EJC Suppl. 2013, 11, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, F.; Shen, T.; Luo, Q.; Ding, Z.; Qian, L.; Huang, J. Plasma miR-145, miR-20a, miR-21 and miR-223 as novel biomarkers for screening early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Hou, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Lu, C. Extracellular vesicles secreted by hypoxia pre-challenged mesenchymal stem cells promote non-small cell lung cancer cell growth and mobility as well as macrophage M2 polarization via miR-21-5p delivery. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, M.; Wang, K.; Zang, X.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.; Cui, L.; Pan, L.; et al. MiR-21 and MiR-155 promote non-small cell lung cancer progression by downregulating SOCS1, SOCS6, and PTEN. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 84508–84519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.F.; Wu, Z.P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.S.; Hamidi, S.; Navab, R. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) regulates cellular proliferation, invasion, migration, and apoptosis by targeting PTEN, RECK and Bcl-2 in lung squamous carcinoma, Gejiu City, China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkountakos, A.; Sartori, G.; Falcone, I.; Piro, G.; Ciuffreda, L.; Carbone, C.; Tortora, G.; Scarpa, A.; Bria, E.; Milella, M.; et al. PTEN in Lung Cancer: Dealing with the Problem, Building on New Knowledge and Turning the Game Around. Cancers 2019, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Cai, Z.; Roberts, T.M. The Mechanisms Underlying PTEN Loss in Human Tumors Suggest Potential Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokosuka, T.; Takamatsu, M.; Kobayashi-Imanishi, W.; Hashimoto-Tane, A.; Azuma, M.; Saito, T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; She, Y.; Wu, K.; Gu, S.; Li, L.; Dong, C.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y. N(6)-methyladenosine-modified circIGF2BP3 inhibits CD8(+) T-cell responses to facilitate tumor immune evasion by promoting the deubiquitination of PD-L1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Zhu, S.Q.; Pei, X.; Qiu, B.Q.; Xiong, D.; Long, X.; Lin, K.; Lu, F.; Xu, J.J.; Wu, Y.B. Cancer cell-derived exosomal circUSP7 induces CD8(+) T cell dysfunction and anti-PD1 resistance by regulating the miR-934/SHP2 axis in NSCLC. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, L.A.; Bray, F.; Siegel, R.L.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelt, A.L.; Pløen, J.; Harling, H.; Jensen, F.S.; Jensen, L.H.; Jørgensen, J.C.; Lindebjerg, J.; Rafaelsen, S.R.; Jakobsen, A. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: A prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; He, L.; Liu, F. Effect of colorectal resection combined with intraoperative radiofrequency ablation in treating colorectal cancer with liver metastasis and analysis of its prognosis. J. Buon 2020, 25, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.K.; Poortmans, P.; Chalmers, A.J.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Hall, E.; Huddart, R.A.; Lievens, Y.; Sebag-Montefiore, D.; Coles, C.E. Practice-changing radiation therapy trials for the treatment of cancer: Where are we 150 years after the birth of Marie Curie? Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugase, T.; Takahashi, T.; Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Hiramatsu, K.; Ohkawara, T.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Makino, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; et al. SOCS1 Gene Therapy Improves Radiosensitivity and Enhances Irradiation-Induced DNA Damage in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6975–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Gong, W.; Wang, J.; Ji, K.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; He, N.; Du, L.; Liu, Q. Identification of Circular RNAs Altered in Mouse Jejuna After Radiation. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Peng, X.; Yan, D.; Tang, H.; Huang, F.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Z. Msi-1 is a predictor of survival and a novel therapeutic target in colon cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tintut, Y.; Demer, L.L. Exosomes: Nanosized cellular messages. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kang, H.; Gao, M.; Jin, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, D.; Li, M.; Xiao, L. Exosome-transmitted circ_MMP2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by upregulating MMP2. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1365–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, A.; Zhou, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor induces immunosuppression in lung cancer by upregulating B7-H4 expression through the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2020, 485, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, T.B.; Tomblin, J.K. Insulin/Insulin-like growth factors in cancer: New roles for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, tumor resistance mechanisms, and new blocking strategies. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, B.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, W.; Wu, C.; et al. A novel protein encoded by a circular RNA circPPP1R12A promotes tumor pathogenesis and metastasis of colon cancer via Hippo-YAP signaling. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domper Arnal, M.J.; Ferrández Arenas, Á.; Lanas Arbeloa, Á. Esophageal cancer: Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 7933–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Nakajima, M. Treatments for esophageal cancer: A review. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013, 61, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrely, V.; Launay, V.; Najah, H.; Smith, D.; Collet, D.; Gronnier, C. Prognostic factors in esophageal cancer treated with curative intent. Dig Liver Dis. 2018, 50, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Zhang, E.; He, R.; Wang, X. Newly developed strategies for improving sensitivity to radiation by targeting signal pathways in cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ginther, C.; Kim, J.; Mosher, N.; Chung, S.; Slamon, D.; Vadgama, J.V. Expression of Wnt3 activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway and promotes EMT-like phenotype in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagni, C.; Almeida, L.O.; Balan, T.; Martins, M.T.; Rosselli-Murai, L.K.; Papagerakis, P.; Castilho, R.M.; Squarize, C.H. PTEN Mediates Activation of Core Clock Protein BMAL1 and Accumulation of Epidermal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 9, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, N.; Lin, Y.; Travis, G.; Simpson, A.M.; Nassif, N.T.; McGowan, E.M. PTEN/PTENP1: ‘Regulating the regulator of RTK-dependent PI3K/Akt signalling’, new targets for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, S.C.; D’Amico, A.V. Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Graham, P.H.; Hao, J.; Bucci, J.; Cozzi, P.J.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. Emerging roles of radioresistance in prostate cancer metastasis and radiation therapy. Cancer Metastasis. Rev. 2014, 33, 469–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita, T.L.; Petras, K.G.; Wafford, Q.E.; Berendsen, M.A.; Kruser, T.J. Radiotherapy for cranial and brain metastases from prostate cancer: A systematic review. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 133, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Jiang, F.; Yang, C.; Yan, Q.; Guo, W.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, G. Role of autophagy in regulating the radiosensitivity of tumor cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhong, D. High kinesin family member 18A expression correlates with poor prognosis in primary lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac. Cancer 2019, 10, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.T.; Zhong, F.K. Kinesin Family Member 18A (KIF18A) Contributes to the Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 6383685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhi, H.; Wang, P.; Gao, Y.; Guo, M.; Yue, M.; Wang, Y.; Shen, W.; et al. Inferences of individual drug responses across diverse cancer types using a novel competing endogenous RNA network. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 12, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Xie, P.; Wang, P.; Liu, M.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y. Circular RNA circ_0074026 indicates unfavorable prognosis for patients with glioma and facilitates oncogenesis of tumor cells by targeting miR-1304 to modulate ERBB4 expression. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 4688–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wang, M.; Qiang, J.; Guo, S. Circular RNA circ-PITX1 promotes the progression of glioblastoma by acting as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate miR-379-5p/MAP3K2 axis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 863, 172643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Li, Y.; Ming, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, Z.; Qiu, L.; Wang, T. Comprehensive circular RNA expression profile in radiation-treated HeLa cells and analysis of radioresistance-related circRNAs. Peer J. 2018, 6, e5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Bao, C.; He, J.; Chen, B.; Lyu, D.; Zheng, B.; Xu, Y.; Long, Z.; et al. Circular RNA profile identifies circPVT1 as a proliferative factor and prognostic marker in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017, 388, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, M.; Xiang, B.; Zhao, K.; Qin, B. Circular RNA PVT1 promotes metastasis via miR-145 sponging in CRC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 512, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Chen, Z.; Mo, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, P. Potential Role of circPVT1 as a proliferative factor and treatment target in esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Du, W.Z. Circular RNA circ-PVT1 contributes to paclitaxel resistance of gastric cancer cells through the regulation of ZEB1 expression by sponging miR-124-3p. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20193045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Xu, R. CircPVT1 contributes to chemotherapy resistance of lung adenocarcinoma through miR-145-5p/ABCC1 axis. Biomed. Pharm. 2020, 124, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, N.L.; Hayes, D.F. Cancer biomarkers. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari Ghods, F. Circular RNA in Saliva. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1087, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottesen, E.W.; Luo, D.; Seo, J.; Singh, N.N.; Singh, R.N. Human Survival Motor Neuron genes generate a vast repertoire of circular RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 2884–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S.T.; Baker, B.F.; Crooke, R.M.; Liang, X.H. Antisense technology: An overview and prospectus. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.T.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Yang, B.B. Targeting circular RNAs as a therapeutic approach: Current strategies and challenges. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).