Abstract

In this work, we present a new set of transition probabilities for experimentally classified spectral lines in the Os VI spectrum. To do this, two independent computational approaches based on the pseudo-relativistic Hartree–Fock, including core polarization effects (HFR+CPOL) and fully relativistic Multiconfiguration Dirac–Hartree–Fock (MCDHF) methods, were used, with the detailed comparison of the results obtained with these two approaches allowing us to estimate the quality of the calculated radiative parameters. These atomic data, corresponding to 367 lines of five-times ionized osmium between 438.720 and 1486.275 Å, are expected to be useful for the analysis of the spectra emitted by fusion plasmas in which osmium could appear as a result of transmutation by the neutron bombardment of tungsten used as component of the reactor wall, such as the ITER divertor.

1. Introduction

It is now well established that tungsten (W) will be widely used in nuclear fusion reactors as a plasma-facing material due to its high melting point, low sputtering yield, and resistance to neutron irradiation. In particular, tungsten will be a key material for the divertor of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), the component designed to manage heat and particle flux from the plasma [1,2,3]. During nuclear fusion operations, the divertor will endure some of the harshest conditions in the reactor. Thus, under neutron bombardment, tungsten will undergo nuclear transmutation, forming other elements, including osmium [4].

As a transmutation product of tungsten, osmium atoms will also be sprayed into the plasma, altering its composition. Monitoring osmium’s spectroscopic signals will help in understanding the dynamics of plasma–wall interactions, which are crucial for predicting material erosion and plasma contamination. The high ionization potential of neutral osmium (8.4 eV) means its ionic species may survive in high-temperature plasmas, providing diagnostic data about plasma conditions. Spectral lines of Os ions will therefore be particularly useful for identifying impurity influx from plasma-facing components, and the corresponding radiative decay rates will also be used to calculate essential plasma properties, such as electron temperature and density. These properties are actually mainly estimated by measuring intensity ratios between spectral lines emitted by the plasma (see, e.g., [5]). Since these intensities are proportional to the transition probabilities, these latter parameters are of paramount importance for plasma diagnostics.

The main goal of the present work is to make a new contribution to this field by determining the transition probabilities for spectral lines of five-times ionized osmium (Os VI), which is characterized by a moderately complex atomic structure with 71 electrons giving 5d3 4F3/2 as the ground level. Spectroscopic studies have already been carried out previously for this ion. Indeed, nearly 30 years ago, Raassen et al. [6] classified 290 lines belonging to the 5d3–5d26p transition array in the 435–765 Å region and 87 lines belonging to the 5d26s–5d26p transition array in the 940–1510 Å region from the analysis of spectrograms made by means of the 3.0 m and 10.6 m normal incidence spectrographs installed at that time in Antigonish (Canada) and Meudon (France). This resulted in the determination of all levels (19) in the 5d3 ground configuration, 14 levels (out of 16 possible) in the 5d26s configuration, and all levels (45) in the 5d26p configuration. The analysis was guided by predicted energy level values and transition probabilities calculated by means of a complete set of orthogonal operators. Calculated energy values, LS-compositions, and gA-values, obtained from the fitted parameters using a rather limited configuration interaction, model were also reported. More recently, Azarov [7] critically reviewed the data available on the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations in the Lu I isoelectronic sequence, including Os VI, by means of calculations with orthogonal operators. This study allowed for the determination of two new levels in the 5d26s configuration of Os VI, namely (3P)2P1/2 and (3P)4P5/2.

If the electronic structure of the first three configurations of Os VI is now well known, the same cannot be said for the radiative parameters, which have only been calculated by means of the pseudo-relativistic Hartree–Fock method (HFR) including the configuration interaction in a very limited way [6]. This motivated the present work, the objective of which is to provide a new set of reliable transition probabilities for experimentally observed spectral lines of Os VI. To do this, two independent methods were used, namely the pseudo-relativistic Hartree–Fock approach including core polarization corrections (HFR+CPOL) and the fully relativistic Multiconfiguration Dirac–Hartree–Fock approach (MCDHF), with the cross-comparison of the results obtained with these two methods allowing us to estimate the accuracy of the new calculated radiative data.

2. Computational Approaches

2.1. Pseudo-Relativistic Hartree–Fock Method with Core Polarization Corrections

The first method used for computing the radiative rates in Os VI was the pseudo-relativistic Hartree–Fock (HFR) method, originally introduced by Cowan [8], modified for taking core polarization effects into account, giving rise to the so-called HFR+CPOL method, as described, e.g., in [9,10,11].

The physical model was chosen as consisting of three valence electrons surrounding an Os IX-type ionic core with 68 electrons. This led us to consider the valence–valence interactions by explicitly introducing the following configurations into the calculations: 5d3 + 5d26s + 5d27s + 5d6s2 + 5d26d + 5d6p2 + 5d6d2 + 5d5f2 + 5d6f2 + 5d6s6d + 5d6p5f + 5d6p6f + 5d5f6f + 6s26d + 6s6p2 + 6p26d + 6s6d2 + 6d3 + 6s5f2 + 6d5f2 + 6s6f2 + 6d6f2 for the even parity, and 5d26p + 5d27p + 5d25f + 5d26f + 5d6s6p + 5d6s5f + 5d6s6f + 5d6p6d + 5d6d5f + 5d6d6f + 6s26p + 6s25f + 6s26f + 6p25f + 6p26f + 6p3 + 6p6d2 + 6d25f + 6d26f + 6p5f2 + 6p6f2 + 5f26f + 5f6f2 for the odd parity. This list of configurations is similar to the one considered for our recent HFR+CPOL calculations of radiative parameters in the isoelectronic ion Re V [12], to which the 5d27s and 5d27p configurations were added. Core–valence interactions were then estimated using a core polarization potential and a correction to the electric dipole operator, as described in [9,10,11], with a dipole polarizability αd = 1.50 a03 and a cut-off radius rc = 1.12 a0, the former parameter being found by extrapolating the αd-values published by Fraga et al. [13] for the first ions of the erbium isoelectronic sequence, i.e., Tm II, Yb III, Lu IV, and Hf V, while the latter parameter corresponds to the mean radius of the outermost orbital of the Os IX ionic core (5p), as obtained in the HFR calculations.

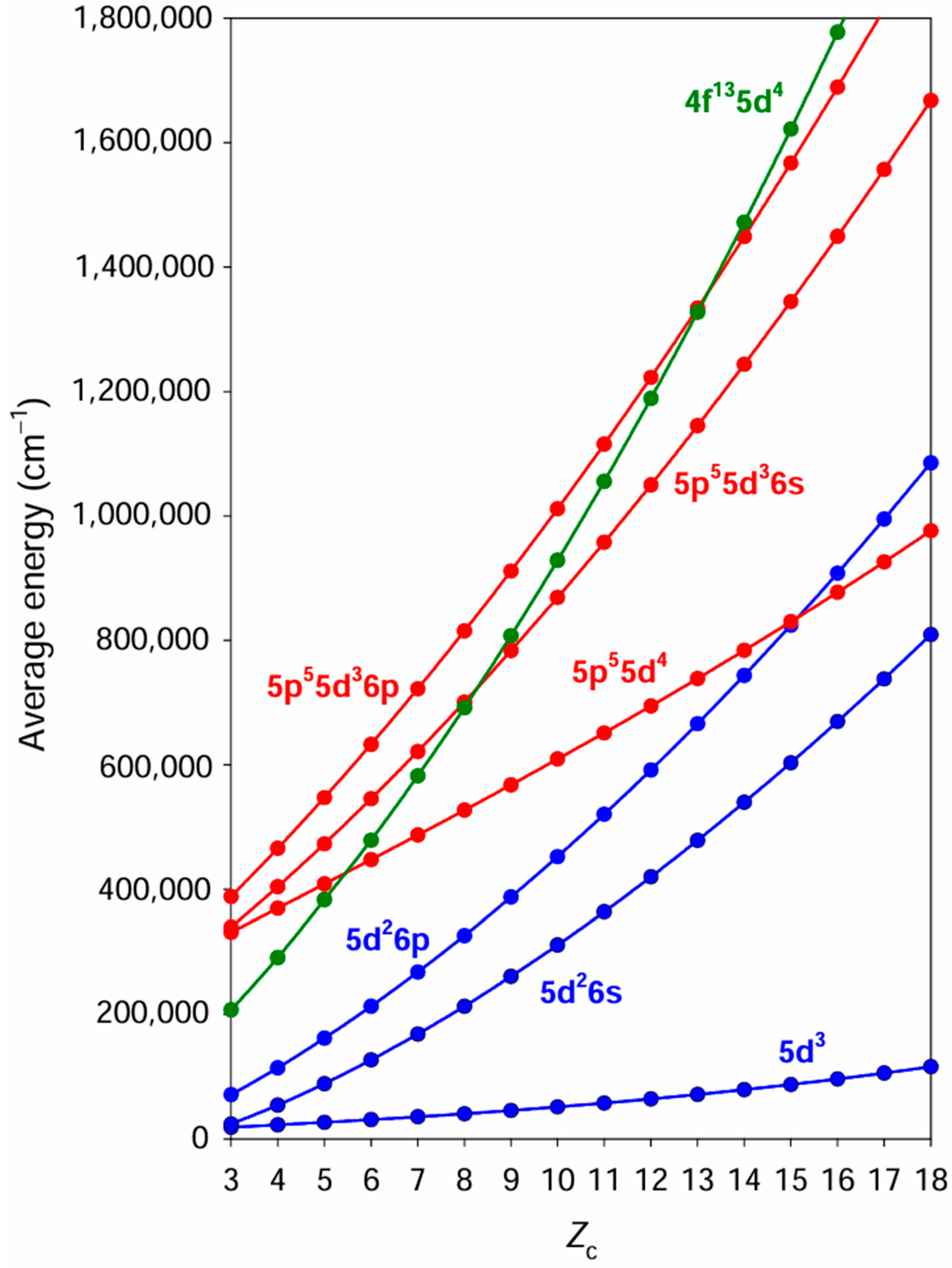

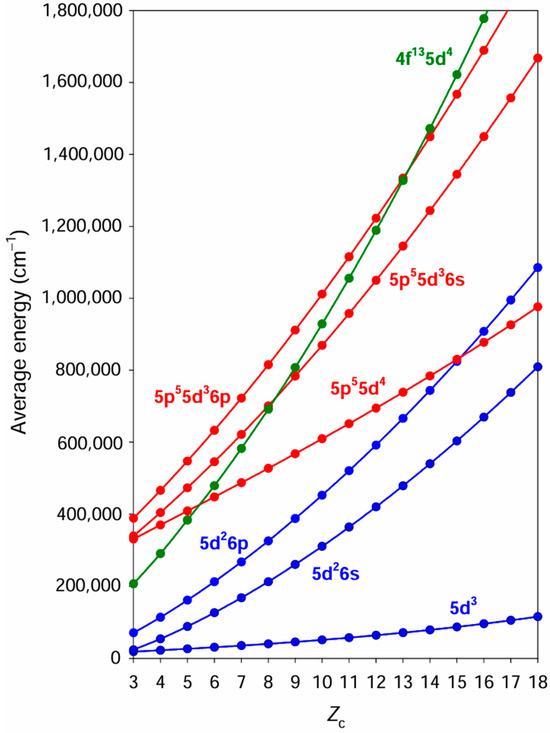

It should be noted that this HFR+CPOL approach is valid if core-excited configurations do not overlap the configurations of interest. It was verified that this is actually the case for the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations in Os VI. Indeed, a simple calculation of average energies for some configurations with an electron excitation from the 4f and 5p core orbitals showed that such configurations were located well above the 5d3, 5d26s and 5d26p configurations in Os VI. This is illustrated in Figure 1 where the average energies of the 5p55d4, 5p55d36s, 5p55d36p, and 4f135d4 core-excited configurations are compared with those corresponding to the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations along the Lu isoelectronic sequence from Ta III to Ra XVIII. When looking at this figure, it is clear that the lowest configurations with open 5p and 4f orbitals are several hundred thousand cm−1 above the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations in Os VI (Zc = 6). Their interactions with the latter can therefore be estimated by means of the CPOL effects introduced in the HFR method. It is also interesting to note that this is no longer the case for higher ionization stages in the isoelectronic sequence since the 5p55d4 and 5d36p configurations cross each other around At XV (Zc = 15). For neighboring and higher charged ions, it would then be necessary to explicitly introduce the 5p55d4 configuration in the calculations rather than estimating its influence on the 5d3–5d26p and 5d26s–5d26p transitions by means of CPOL corrections.

Figure 1.

Average energies obtained with the HFR+CPOL method for 5d3, 5d26s, 5d26p, 5p55d4, 5p55d36s, 5p55d36p, and 4f135d4 configurations in Lu-like ions from Ta III (Zc = 3) to Ra XVIII (Zc = 18). Zc = Z − N + 1, where Z is the atomic number and N is the total number of electrons in the ion.

The HFR+CPOL calculations were then refined using a well-known least-squares fitting procedure of the computed energy levels to the experimental values available in the literature. More precisely, the experimental energy levels belonging to the 5d3 and 5d26s even configurations and the 5d26p odd configuration published by Raassen et al. [6] were used to optimize the radial parameters corresponding to the average energies (Eav), the Slater integrals (Fk, Gk, Rk), the spin orbit parameters (ζnl), and the effective interaction parameters α and β characterizing these three configurations. This led to average deviations between calculated and experimental energies of 46 cm−1 and 150 cm−1 for the even and odd parities, respectively. These deviations are slightly higher than those obtained in the fits made by Raaseen et al. [6] (i.e., 11 and 107 cm−1) and Azarov [7] (14 and 95 cm−1) for the same configurations, but it should be noted that our calculations include a much larger number of interacting configurations, which often leads to slightly more complicated adjustment procedures because of the more numerous mixtures in the eigenvector compositions. A detailed comparison between the HFR+CPOL levels and the available experimental values reported in [6,7] is given in Table 1, in which the first two LS-components obtained in our calculations for each level are also listed. These eigenvector compositions are in excellent agreement with those published in [7].

Table 1.

Comparison of the energy levels computed in the present work using the HFR+CPOL and MCDHF methods with the available experimental values for the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations of Os VI. All values are given in cm−1.

2.2. Fully Relativistic Multiconfiguration Dirac–Hartree–Fock Method

The second computational approach used in the present work was the fully relativistic Multiconfiguration Dirac–Hartree–Fock (MCDHF) method, as described in [14,15] and implemented in the latest version of the General Relativistic Atomic Structure Package, namely GRASP2018 [16].

We started our calculations by considering the 5d3 and 5d26s even and the 5d26p odd parity configurations as the multireference (MR) with all the orbitals optimized on the 5d3 4F3/2 ground state, in a first step, and then optimizing separately only the 5d and 6s orbitals on all the levels of the MR even configurations (5d3 + 5d26s), and only the 5d and 6p orbitals on all the levels of the MR odd configuration 5d26p. Thereafter, correlation orbitals were introduced and optimized layer by layer on all the levels of the MR in two steps in valence–valence (VV) expansions of the atomic state functions (ASFs), where all single and double (SD) excitations were allowed from the 5d, 6s, and 6p spectroscopic orbitals to the following orbital active sets (ASs), where the set of nmax stands for the maximum value of the orbital principal quantum number for each azimuthal quantum number l: {7s,6p,6d,5f} and {6s,7p,6d,5f} for the even and odd parities, respectively, in a first step (VV1 model), and {8s,7p,7d,6f} and {7s,8p,7d,6f} for the even and odd parities, respectively, in a second step (VV2 model). Finally, core–valence (CV) and core–core (CC) correlations were considered in a relativistic configuration interaction (RCI) calculation using the orbitals optimized previously. Here, the ASF expansions were further extended by adding SD excitations from the 4f core orbital of the MR configurations to the AS of the last step of the orbital optimizations. This gave rise to 515,057 and 900,402 configuration state functions (CSFs) in the even and odd parities, respectively.

The final MCDHF energy levels are compared to the available experimental values in Table 1, where it can be seen that a satisfactory agreement has been reached, the average deviation being equal to 8% for the whole set of energy levels belonging to the 5d3, 5d26s, and 5d26p configurations, with a lower value for even parity levels (4%) compared to the value obtained for odd parity levels (10%). It would be necessary to extend the orbital active sets to see if a better agreement between the MCDHF and experimental levels could be obtained, but as the main purpose of the MCDHF calculations was to verify the overall consistency of the HFR+CPOL radiative parameters, we preferred not to run more extended (and time-consuming) MCDHF calculations in the present work.

3. Radiative Decay Rates

Transition probabilities (gA in 1010 s−1) obtained in the present work with the HFR+CPOL and MCDHF methods are reported in Table 2. They are given for the lines experimentally identified by Raassen et al. [6] in the Os VI spectrum between 438.720 and 1486.275 Å. In this table, the transitions are classified by the numerical values of the lower and upper energy levels, with the spectroscopic designations of these levels given in Table 1. Transition probabilities published in [6] are also given for comparison in Table 2.

Table 2.

Transition probabilities for experimentally observed lines in the Os VI emission spectrum.

A first observation that can be made when looking at this table is that our HFR+CPOL transition probabilities are in good agreement with the results previously published by Raassen et al. [6], with a mean ratio gAHFR+CPOL/gARaassen equal to 0.95 ± 0.21 (where the number after ± represents the standard deviation from the mean), which is quite comparable to the ratio we get when comparing our HFR calculations with and without core polarization corrections, i.e., gAHFR+CPOL/gAHFR = 0.98 ± 0.10. It should be noted, however, that our new HFR+CPOL results were obtained on the basis of a more extensive configuration interaction model than the one considered in [6].

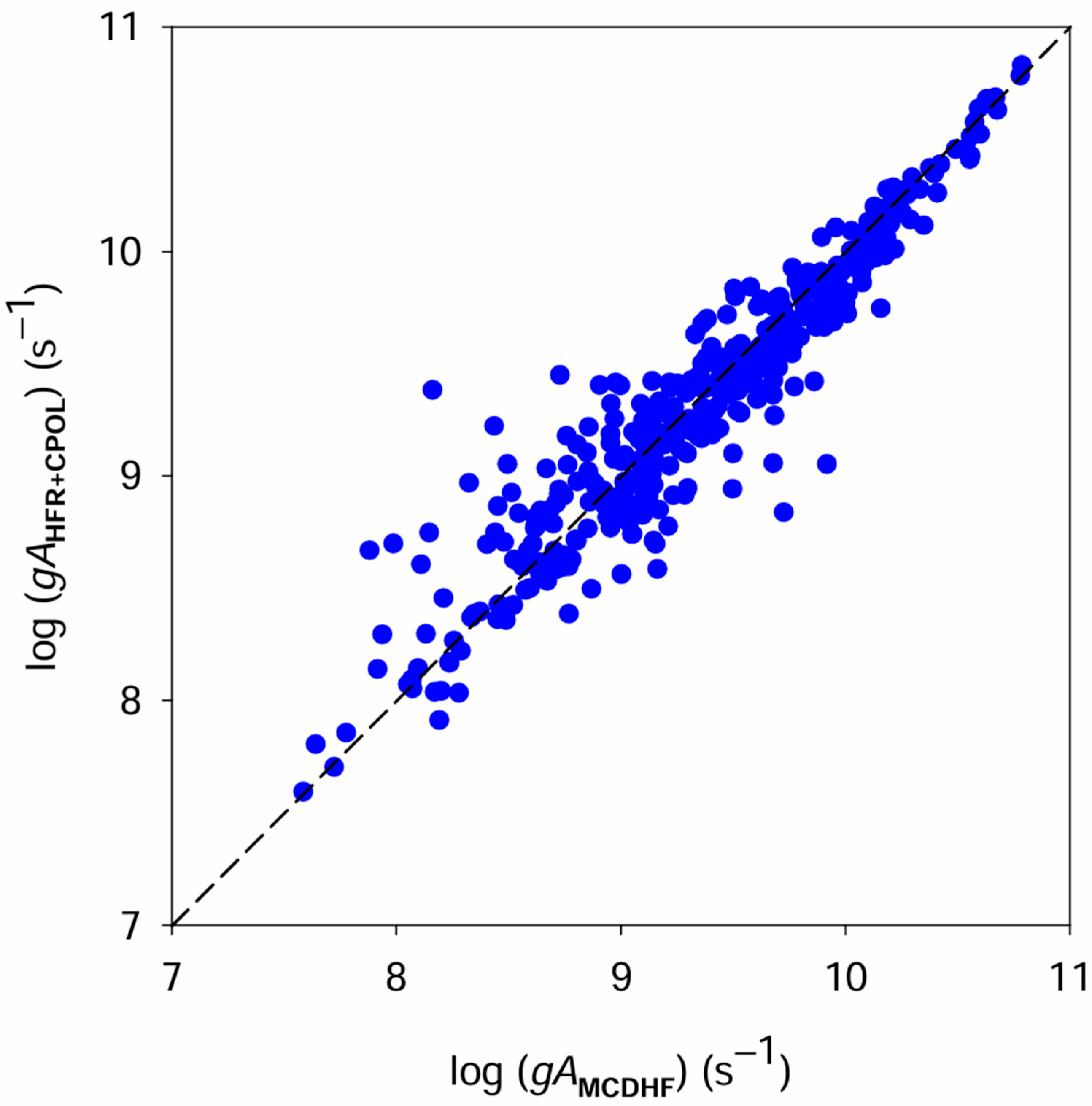

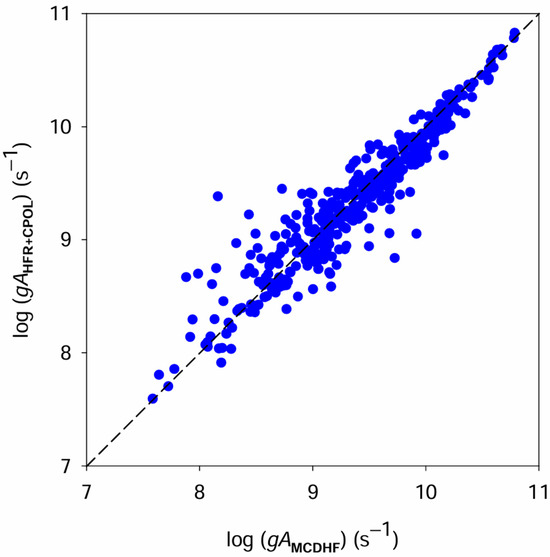

It is also interesting to note that the agreement between the HFR+CPOL and MCDHF results obtained in the present work is generally good, the mean ratio between both sets of data, gAHFR+CPOL/gAMCDHF, being equal to 1.08 ± 0.42, if we exclude the two transitions at 526.999 and 555.333 Å for which the gA-values differ from each other by one or two orders of magnitude. This means that the majority of our gA-values calculated using the two methods agree within a few tens of percent. Such a comparison is shown in Figure 2 where transition probabilities obtained using the HFR+CPOL approach are plotted against those deduced from MCDHF calculations.

Figure 2.

Comparison between transition probabilities (gA) obtained using the HFR+CPOL method and those deduced from MCDHF calculations for all Os VI lines considered in the present work (blue dots).

The quality of the transition probabilities obtained in our work can also be estimated from parameters such as the cancellation factor (CF) and the uncertainty parameter (dT) for HFR+CPOL and MCDHF calculations, respectively. As a reminder, the former parameter is defined by [8]:

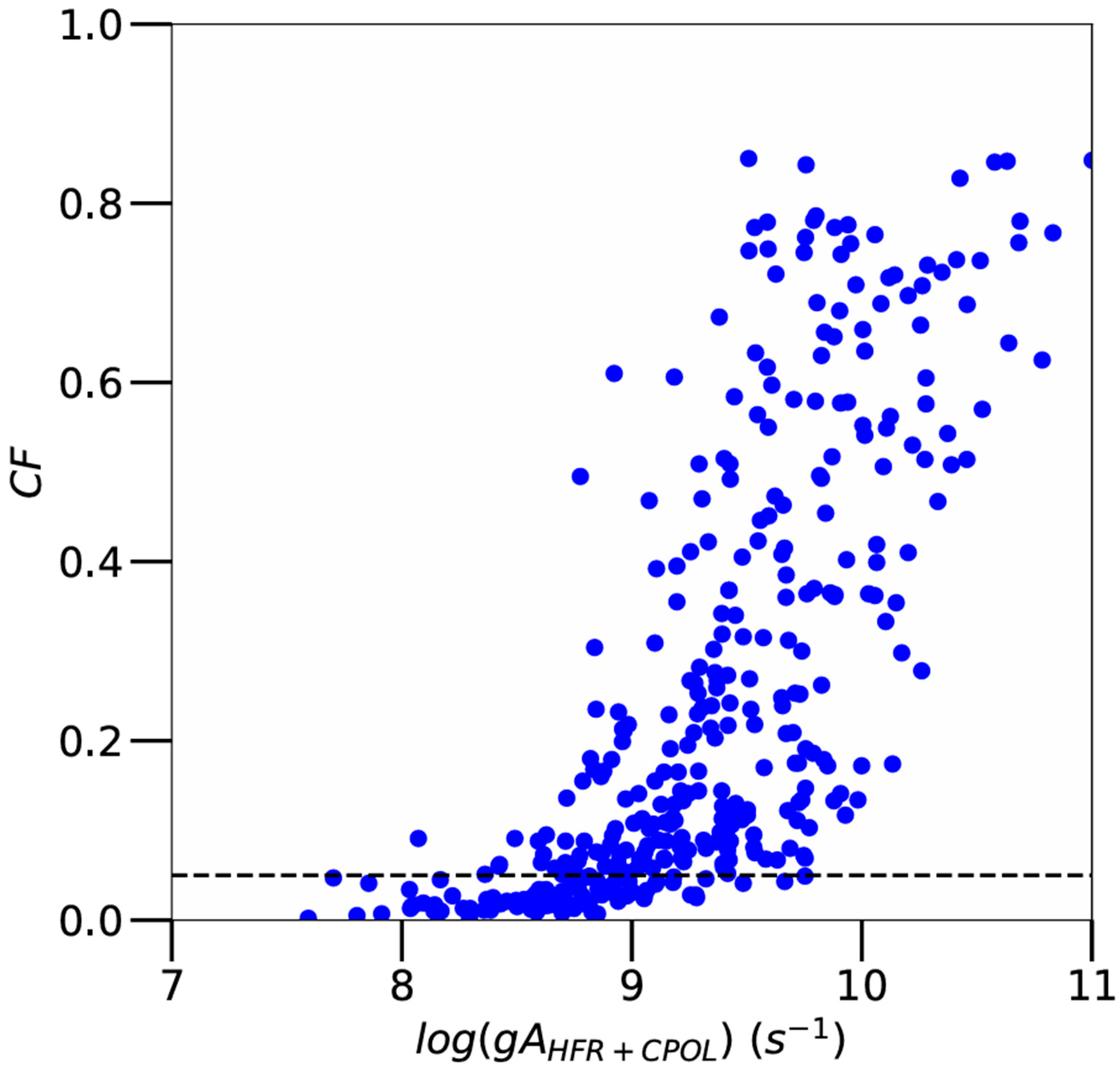

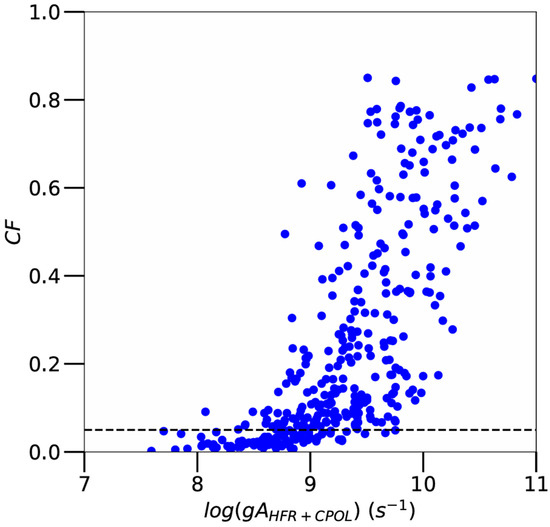

where P(1) is the dipole operator for the transition between two atomic states|γJ> and |γ’J’> developed in terms of pure basis states |βJ> and|β’J’>, with yγβJ and y γ’β’J’ as mixing coefficients, respectively. According to Cowan [8], very small values of this parameter (typically CF < 0.05) may be expected to show significant errors in the computed line strengths. In our work, it was verified that the CF-values were larger than 0.05 for most of the lines listed in Table 2, the only exceptions occurring for 91 transitions (among 367) generally characterized by rather weak gA-values (typically smaller than 109 s−1). This is illustrated in Figure 3, where the CF parameter is plotted as a function of HFR+CPOL transition probabilities for all Os VI lines considered in the present work.

Figure 3.

Cancellation factors (CF) as a function of gA-values obtained using the HFR+CPOL method for all Os VI transitions considered in the present work (blue dots). The dotted line corresponds to CF = 0.05.

As for the dT parameter, it is expressed by [17]:

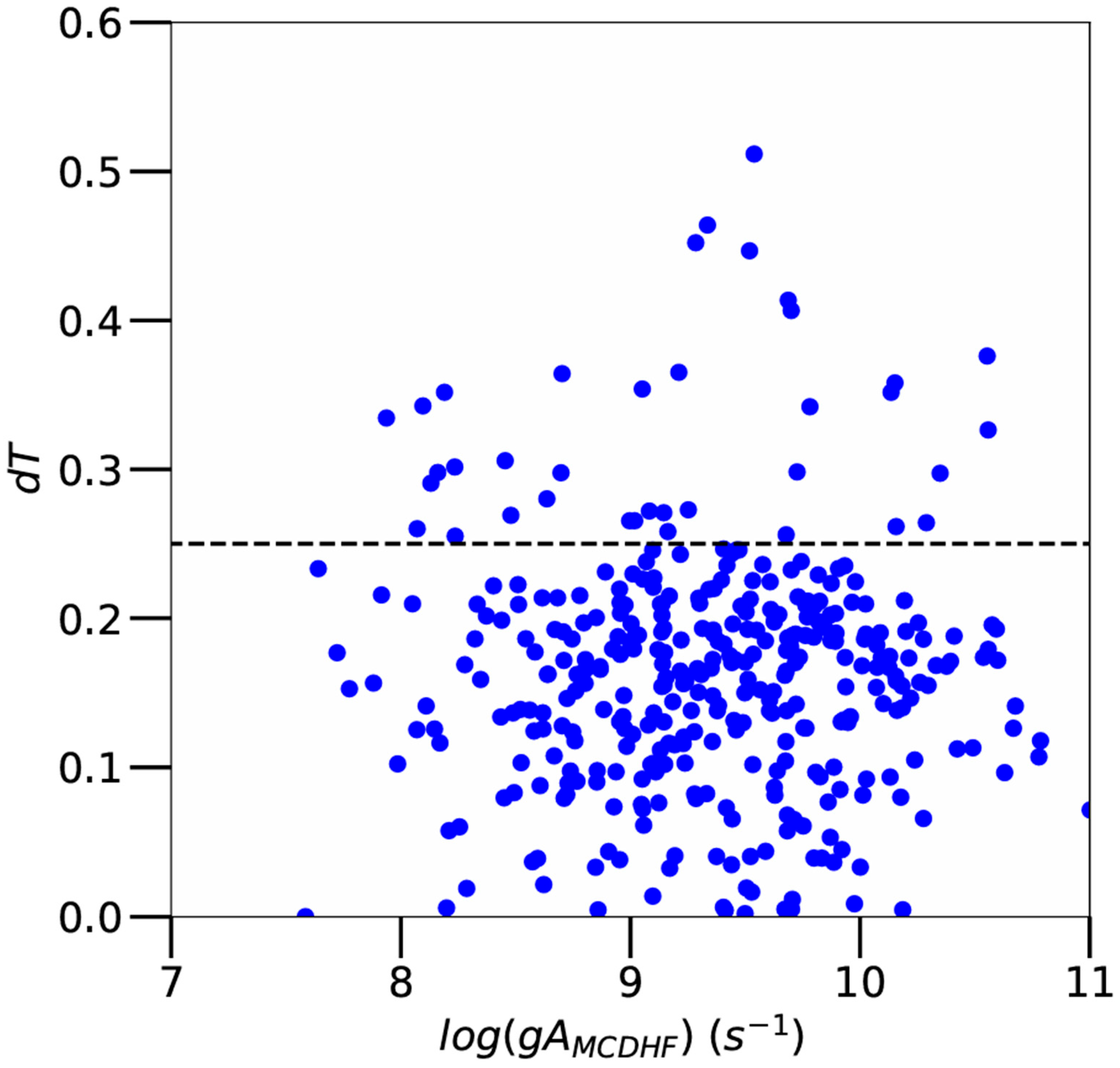

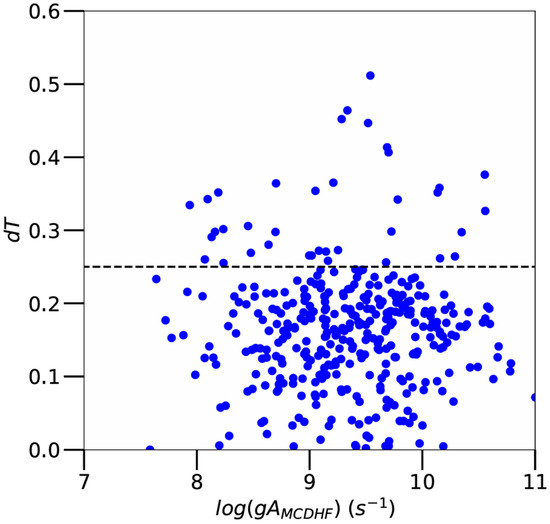

where AB and AC are transition probabilities in Babushkin (length) and Coulomb (velocity) gauges, the electric dipole transition moment having the same value in both formalisms for exact solutions of the Dirac equation [18]. The dT parameter thus provides a statistical estimate of the uncertainty of MCDHF transition rates for approximate solutions for which the transition moment differs from one gauge to another. For transitions listed in Table 2, the average value of dT was found to be equal to 0.17 ± 0.06, which means that the uncertainties affecting most or our MCDHF gA-values do not exceed 25%. The few exceptions for which the dT parameter was found to be greater than 25% concern only 42 transitions out of the 367 listed in Table 2. This is illustrated in Figure 4, where dT is plotted as a function of gAMCDHF.

Figure 4.

Uncertainty parameter (dT) as a function of gA-values obtained using the MCDHF method for all Os VI transitions considered in the present work (blue dots). The dotted line corresponds to dT = 0.25.

Finally, it should be noted that, if we set aside the transitions listed in Table 2, for which both CF < 0.05 (in the HFR+CPOL calculations) and dT > 0.25 (in the MCDHF calculations), there remain 250 transitions whose differences between the gA-values obtained using the two methods do not exceed 30%, the mean relative deviation ΔgA/<gA> (where ΔgA = |gAHFR+CPOL − gAMCDHF| and <gA> = (gAHFR+CPOL + gAMCDHF)/2) being equal to 0.29. Consequently, at least for these 250 lines, the uncertainty on the HFR+CPOL and MCDHF transition probabilities obtained in our work can be estimated at most 30%, the gA-values of other transitions can be affected by slightly larger uncertainties up to a factor of two. However, given the much better agreement obtained between the HFR+CPOL energy levels and the experimental values, we can assume that the gAHFR+CPOL-values are of better quality overall than the MCDHF results.

4. Conclusions

New transition probabilities for experimentally observed lines in the Os VI spectrum are reported in the present work. They were obtained using two different computational approaches based on the pseudo-relativistic Hartree–Fock method including core polarization corrections (HFR+CPOL) and the fully relativistic Multiconfiguration Dirac–Hartree–Fock method (MCDHF). Based on the detailed comparison showing a good agreement between the two sets of results (within a few tens of percent for most transitions), it can be concluded that the gAHFR+CPOL-values reported in this paper for Os VI lines can be considered to be of fairly good quality for their application in plasma diagnostics. These new atomic data will thus be useful for the analysis of the spectra emitted by fusion plasmas produced in Tokamaks such as ITER.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and P.Q.; methodology, M.B., P.P. and P.Q.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B., P.P. and P.Q.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B.; resources, M.B. and P.Q.; data curation, M.B. and P.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Q.; writing—review and editing, M.B., P.P. and P.Q.; visualization, P.Q.; supervision, P.Q.; project administration, P.Q.; funding acquisition, P.P. and P.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by F.R.S.-FNRS—EOS grant number O.0004.22.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

P.P. and P.Q. are, respectively, Research Associate and Research Director of the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research F.R.S.-FNRS. This project received funding from the FWO and F.R.S.-FNRS under the Excellence of Science (EOS) program (number O.0004.22). Part of the atomic calculations were made with computational resources provided by the Consortium des Equipements de Calcul Intensif (CECI), funded by the F.R.S.-FNRS under grant no. 2.5020.11 and by the Walloon Region of Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pitts, R.A.; Carpentier, S.; Escourbiac, F.; Hirai, T.; Komarov, V.; Lisgo, S.; Kukushkin, A.S.; Merola, M.; Sashala Naik, A.; Mitteau, R.; et al. A full tungsten divertor for ITER: Physics issues and design status. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 438, S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Panayotis, S.; Barabash, V.; Amzallag, C.; Escourbiac, F.; Durocher, A.; Merola, M.; Linke, J.; Loewenhoff, T.; Pintsuk, G.; et al. Use of tungsten material for the ITER divertor. Nucl. Mat. En. 2016, 9, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, R.A.; Bonnin, X.; Escourbiaca, F.; Frerichs, H.; Gunn, J.P.; Hirai, T.; Kukushkin, A.S.; Kaveeva, E.; Miller, M.A.; Moulton, D.; et al. Physics basis for the first ITER tungsten divertor. Nucl. Mat. En. 2019, 20, 100696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.R.; Sublet, J.C. Neutron-induced transmutation effects in W and W-alloys in a fusion environment. Nucl. Fusion 2011, 51, 043005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, H.-J. Introduction to Plasma Spectroscopy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raassen, A.J.J.; Azarov, V.I.; Uylings, P.H.M.; Joshi, Y.N.; Tchang-Brillet, L.; Ryabtsev, A.N. Analysis of the spectrum of five times ionized osmium (Os VI). Phys. Scr. 1996, 54, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarov, V.I. Parametric study of the 5d3, 5d26s and 5d26p configurations in the Lu I isoelectronic sequence (Ta III–Hg X) using orthogonal operators. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 2018, 119, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.D. The Theory of Atomic Structure and Spectra; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Quinet, P.; Palmeri, P.; Biémont, E.; McCurdy, M.M.; Rieger, G.; Pinnington, E.H.; Wickliffe, M.E.; Lawler, J.E. Experimental and theoretical lifetimes, branching fractions and oscillator strengths in Lu II. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1999, 307, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinet, P.; Palmeri, P.; Biémont, E.; Li, Z.S.; Zhang, Z.G.; Svanberg, S. Radiative lifetime measurements and transition probability calculations in lanthanide ions. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 344, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinet, P. Overview of recent advances performed in the study of atomic structures and radiative processes for the lowest ionization stages of heavy elements. Can. J. Phys. 2017, 95, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, M.; Gamrath, S.; Quinet, P. Radiative decay rates for electric dipole transitions in doubly-, trebly- and quadruply-charged rhenium ions(Re III–V) of interest to nuclear fusion research and astrophysical spectra analyses. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 2024, 157, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, S.; Karwowski, J.; Saxena, K.M.S. Handbook of Atomic Data; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, I.P. Relativistic Quantum Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Froese Fischer, C.; Godefroid, M.R.; Brage, T.; Jönsson, P.; Gaigalas, G. Advanced multiconfiguration methods for complex atoms: I. Energies and wave functions. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2016, 49, 182004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese Fischer, C.; Gaigalas, G.; Jönsson, P. GRASP2018—A Fortran 95 version of the General Relativistic Atomic Structure Package. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2019, 237, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, J.; Godefroid, M.R.; Hartman, H. Validation and implementation of uncertainty estimates of calculated transition Rates. Atoms 2014, 2, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, I.P. Gauge invariance and relativistic radiative transitions. J. Phys. B 1974, 7, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).