Abstract

We investigate the impact of the vortex state of ultralight dark matter (ULDM) on the dynamical friction acting on moving globular clusters. Comparing this force with that for the solitonic ground state, it is shown that the internal structure and rotation of the ULDM core strongly affect the orbital decay of globular clusters. In particular, co-directional rotation in a vortex state can lead to significant suppression of dynamic friction at certain distances where globular clusters and ULDM velocities match. Applying these findings to the Fornax dwarf galaxy, it is found that the Fornax timing problem is naturally alleviated.

1. Introduction

The dynamics of satellite galaxies and their internal stellar systems provide a powerful probe of the fundamental properties of dark matter and its interaction with baryonic matter. In particular, the orbital evolution of massive substructures, including globular clusters within dark-matter-dominated systems, offers a sensitive test of gravitational dynamics on galactic and subgalactic scales. One of the most intriguing and well-studied examples in this context is the Fornax dwarf spheroidal galaxy [1], a satellite of the Milky Way that hosts several globular clusters at relatively large galactocentric distances which have existed for more than 10 Gyr.

Within the standard cold dark matter (CDM) paradigm, globular clusters orbiting inside a massive dark matter halo are expected to experience substantial dynamical friction due to gravitational interactions with background dark matter particles and baryons. This frictional force should lead to orbital decay, causing the clusters to spiral toward the galactic center on timescales that, for some of the observed globular clusters in Fornax, are significantly shorter than the age of the Universe. This apparent contradiction between theoretical predictions and observations is commonly referred to as the Fornax timing problem [2,3,4].

The persistence of this discrepancy has motivated extensive exploration of alternative explanations, including modifications of the dark matter model itself. In this regard, ultralight dark matter (ULDM) has emerged as a particularly compelling candidate [5,6,7,8,9]. ULDM consists of extremely light bosonic particles whose de Broglie wavelength is comparable to galactic scales, leading to pronounced wave-like behavior on astrophysical distances. Due to the extremely large de Broglie wavelength, of the order of kiloparsecs, ULDM models naturally suppress the formation of small-scale structures, in contrast to CDM scenarios, which tend to overpredict the abundance of dwarf galaxies and the amount of dark matter in galactic centers.

These wave effects can suppress dynamical friction and modify the orbital evolution of massive objects embedded in ULDM halos. In our previous work [10], we investigated the Fornax timing problem within the ULDM scenario by assuming a spherically symmetric ground-state configuration of a Bose–Einstein condensate soliton. By incorporating a damping term in the generalized Gross–Pitaevskii equation, we analyzed the time evolution of globular cluster orbits and demonstrated that the solitonic structure of the ULDM halo can substantially affect their dynamical evolution. Analytical formulas for the dynamical friction force were used to contrast the infall times and dynamical evolution of globular clusters in the presence and absence of the damping term.

In the present paper, we extend the analysis of the dynamical friction force acting on a moving massive object, such as a globular cluster, by considering a rotating vortex state of ultralight dark matter. We study how the internal rotation and angular momentum of the ultralight dark matter core influence the dynamical friction force [11,12,13,14,15,16] exerted on globular clusters. In particular, we focus on determining the characteristic timescales over which the velocities and orbits of globular clusters undergo significant changes, and we assess the implications of vortex-induced effects for the long-term stability of globular cluster systems in dwarf galaxies such as Fornax.

2. Ground and Vortex States of ULDM Soliton

Ultralight dark matter can be accurately described as a complex classical field forming a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) on galactic scales [7]. Owing to the extremely small mass of ULDM particles, their de Broglie wavelength is comparable to galactic scales, leading to macroscopic quantum coherence and wave-like behavior of dark matter halos. In this regime, the collective dynamics of the ULDM field cannot be captured by a particle description and must instead be treated in view of large occupation number by using a classical field approach. The dynamical evolution of the self-gravitating and self-interacting BEC field , together with its self-consistent gravitational potential , is governed by the coupled Gross–Pitaevskii–Poisson (GPP) system of equations [7,17],

where m is the mass of the ULDM particle, N is the total number of bosons, ℏ is the Planck constant, and G is the gravitational constant. The nonlinear coupling characterizes the short-range self-interaction between ULDM particles, with being the s-wave scattering length.

Repulsive self-interaction of dark matter particles corresponds to , while describes the attractive case. The last term in Equation (1) represents the gravitational interaction mediated by the potential , which is sourced by the mass density of the condensate via Equation (2) and is responsible for the formation of localized solitonic cores. Approximate analytical, variational, and numerical solutions of the GPP equations have been extensively studied in the literature, revealing the existence of stable solitonic ground states and excited configurations [18,19].

In the present paper, we restrict our attention to the regime of weak repulsive self-interaction between ULDM bosons and adopt a Gaussian variational ansatz [20] for the density profile of the spherically symmetric soliton ground state,

where is the central density and R characterizes the spatial extent of the solitonic core. To describe rotating configurations of the condensate, we consider a toroidal rotated vortex state aligned along the z-axis, whose density profile is given by

where is the cylindrical radial coordinate and denotes the coherence length, which sets the characteristic size of the vortex core; see [18] for details. For the Fornax dwarf spheroidal galaxy, we adopt the fiducial parameters and , consistent with observational constraints. The coherence length is determined by the balance between the kinetic and interaction energies of the condensate and can be expressed as

highlighting the sensitivity of coherence length to both the particle mass and the strength of self-interaction.

Considering a more accurate model of the Fornax galaxy, we have to take into account the baryonic matter with density , which produces the gravitational potential . In dwarf galaxies, the baryonic density can be modeled by the Plummer sphere [21], which reads

and is characterized by the total baryon mass and the Plummer radius b. For Fornax, these parameters are and pc [22,23]. Measuring mass in the units of total DM mass and distance in the units of DM size R, we obtain and . The gravitational potential and the rotation curve can be easily obtained in this case,

For the analytically determined Gaussian density of ultralight dark matter (3), the gravitational potential (solution of the Poisson equation) is given by

where denotes the error function. One can derive the rotation curve for the orbiting objects in the spherically symmetric soliton state of ULDM [24] and the baryonic matter,

In the case of ULDM in the form of a rotating vortex soliton, the gravitational potential at a distance from the centre of the galaxy in the plane is given by

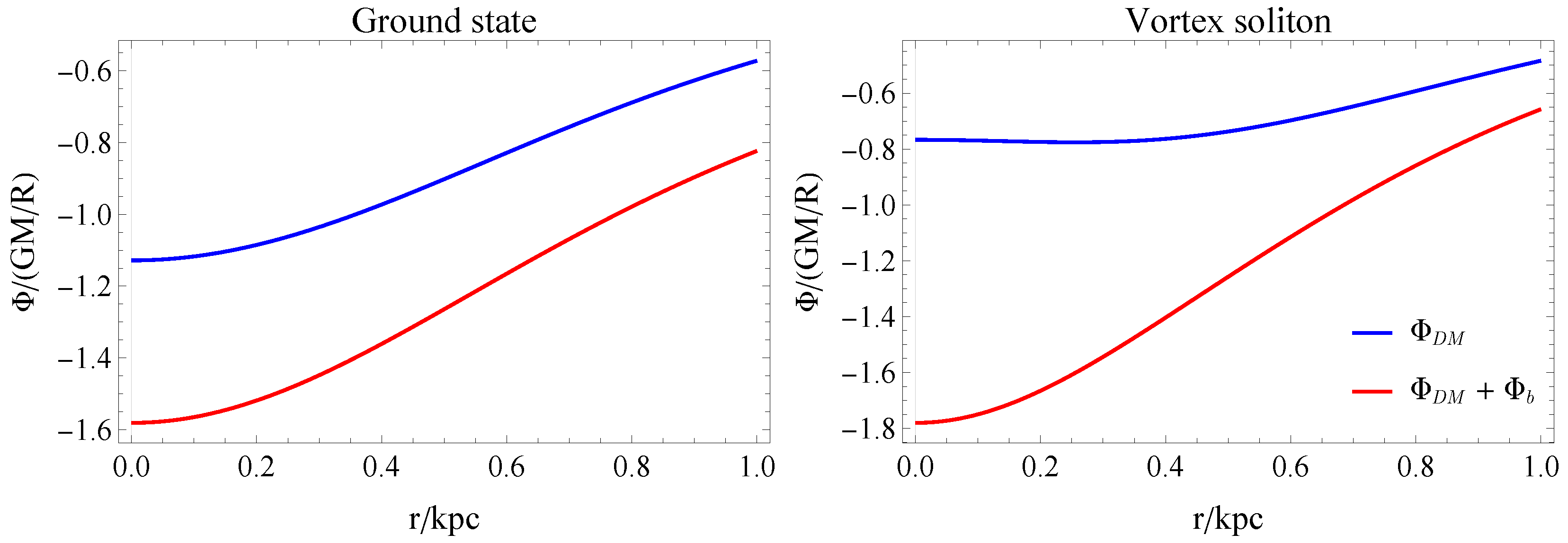

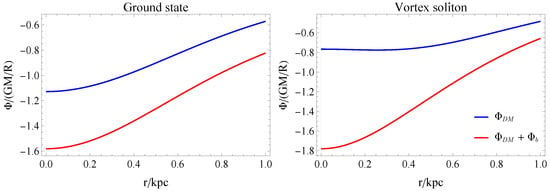

For the vortex soliton case, the vanishing of the DM density in the center of the soliton creates a local maximum at the origin, and thus for the vortex soliton in some region . This implies that no stable rotation curves exist in the region . To ensure the existence of stable rotation curves, it is necessary to take into account the baryonic matter contribution. We present the gravitational potential for the ground and vortex soliton states with and without the contribution of the baryonic matter in Figure 1. It should be noted that the minimum of the potential is shifted from to , when the baryonic contribution is added. After taking the baryon matter contribution, the rotation curve becomes well defined,

where should be taken numerically.

Figure 1.

The gravitational potential with and without baryonic matter in ground (left) and vortex (right) cases. We take for the vortex state.

The vortex solution is described by a wave function whose angular dependence is given by (), i.e., it carries quantized angular momentum, which gives rise to a nonzero particle current,

This current defines the velocity field of ULDM particles circulating around the vortex axis,

In physical units, the corresponding velocity distribution reads

demonstrating that the rotational motion is most pronounced near the vortex core and decreases with radial distance.

Number s defining the angular dependence of the wave function is the so-called topological charge, which determines the angular momentum of the ULDM state. The state with describes the spherically symmetric ULDM soliton ground state, while the state with the wave function and describes the toroidal ULDM soliton rotating around the center of the galaxy. States with higher topological charge are unstable [18,25].

By minimizing the total energy of the solitonic configuration, one obtains the corresponding mass–radius relation for the ULDM condensate [20],

where is the total mass of the soliton DM and the numerical coefficients are given by , , and . The plus sign corresponds to repulsive or vanishing self-interaction (), while the minus sign applies to the attractive case (). In the following, we focus exclusively on the regime. Note the presence of explicit dependence on the Planck constant, which explicitly demonstrates the quantum-mechanical nature of this relation.

Substituting the observationally inferred parameters for the Fornax dwarf galaxy, namely, its radius R and the total DM mass [26], into Equation (16), one obtains the mass–radius relation between the ULDM particle mass m and the scattering length , given by

In the non-interacting limit , this expression yields the characteristic ULDM particle mass . For larger particle masses, nonzero repulsive self-interaction becomes necessary. For smaller values of dark matter particle masses, it follows from Equation (16) that the repulsion between dark matter particles should be replaced by attractive interaction.

Relation (17) allows us to uniquely express the coupling of self-interaction () between dark matter particles in terms of their mass and consider the characteristic time only as a function of the DM particles’ mass and the state of dark matter (ground or vortex).

3. Characteristic Time of the Velocity Change

Having established the theoretical framework for dynamical friction in ultralight dark matter and outlined the method for estimating the characteristic timescale of orbital evolution, we now proceed to a quantitative analysis. In this section, we present numerical results for the dynamical friction acting on globular clusters in both the solitonic ground state and the rotating vortex configuration of the ULDM halo. We focus on how the characteristic timescale depends on the cluster mass, its orbital radius, and the relative orientation between the cluster motion and the ULDM flow, and discuss the implications of these results for the Fornax timing problem.

To perform a qualitative analysis of the impact of dynamical friction on the motion of a globular cluster, it is sufficient to approximate the globular cluster as a point-like object and neglect corrections associated with its finite spatial extent and internal structure [27,28]. This approximation is well justified as long as the characteristic size of the cluster is much smaller than the typical length scales over which the dark matter density and velocity field vary. In this regime, the dominant contribution to dynamical friction arises from the bulk gravitational interaction between the moving cluster and the surrounding dark matter background. In particular, when the Plummer radius is smaller than about of the radius of its orbit, the dynamical friction force is essentially indistinguishable from that of a point-like object.

For a point-like probe moving with a constant velocity along a circular orbit, the dynamical friction force in an ultralight dark matter medium was calculated in [29,30]. In the framework of linear response theory, the backreaction of the medium on the moving object leads to the formation of a gravitational wake, which in turn exerts a drag force opposing the motion of the probe.

A convenient way to characterize the cumulative effect of this force, which we adopt in our study here, is through the characteristic timescale over which the probe experiences a substantial change in its velocity [31],

where denotes the velocity of the probe moving in the plane , M is the mass of the probe, is the tangential component of the dynamical friction force acting on the probe in ULDM environment, and is dynamical friction force acting on probe in the baryonic matter environment.

The explicit expression for the dynamical friction force acting on probe in ULDM environment at its position reads [32]

where is the dark matter density evaluated at the location of the probe. The denominator encodes the dispersion relation of density perturbations in ULDM, with the first term corresponding to the effective pressure of the condensate, while the second term arises from the quantum pressure associated with the wave nature of the ultralight dark matter. The square of adiabatic sound speed is defined as derivative of pressure of ULDM with respect to density. The adiabatic sound speed is given by

and depends on both the local dark matter density and the strength of the self-interaction. This parameter plays a crucial role in determining the efficiency of wake formation and, consequently, the magnitude of the dynamical friction force.

For a test particle of mass M (star or a globular cluster of the corresponding mass), moving with a constant orbital velocity v along a circular trajectory of radius r inside a ultralight dark matter soliton core, the tangential component of the dynamical friction force can be written in a compact analytic form. The friction force (19) acting opposite to the direction of motion can be conveniently presented in the form

where the dimensionless factor encodes the full dependence of the dynamical friction force on the kinematic and microscopic properties of the system. In particular, it accounts for the relative velocity between the star and the dark matter background, as well as for the wave-like response of the superfluid medium. Following the results obtained in Refs. [29,30,32], the dimensionless friction force can be represented as a double sum over angular momentum quantum numbers,

where ℓ and play the role of azimuthal and magnetic quantum numbers, respectively. This decomposition reflects the fact that the gravitational wake generated by the moving perturber can be expanded in spherical harmonics, in close analogy with the classic treatment of dynamical friction in a gaseous medium. Indeed, the derivation of this expression closely parallels the logic of Ostriker’s formula for a massive object moving through a homogeneous fluid [16], but with important modifications arising from the quantum and superfluid nature of ultralight dark matter.

The coefficients entering the above sum are purely numerical and are given by

where denotes the Euler gamma function. These coefficients weight the contribution of individual angular modes to the total friction force and ensure the convergence of the multipole expansion.

The functions appearing in Equation (22) have the form

where and are the spherical Bessel functions of the first and second kind, respectively, while denotes the spherical Hankel function of the first kind. The Heaviside step function ensures the correct treatment of states with different magnetic quantum numbers.

The auxiliary functions are defined as

and depend on the dimensionless parameter ,

which characterizes the ratio between the macroscopic orbital scale and the microscopic quantum scale associated with the ULDM field.

A key quantity controlling the behavior of the dynamical friction force is the Mach number,

where v denotes the magnitude of the relative velocity between the probe () and the local ULDM flow . Note that the absolute value of the dynamic friction force depends only on the modulus of the relative velocity of the test particle relative to dark matter; see more details in [31]. Hence, for the vortex ULDM soliton state, there are two possibilities of the direction of probe motion with respect to ULDM: counter-rotating with the relative velocity and corotating probe motion when .

Since, according to the results in Figure 1, the baryonic matter produces a significant correction to the dark matter gravitational potential, it is necessary to include in the dynamical friction force the contribution due to the baryonic matter. For a probe moving with velocity in the homogeneous baryonic matter with density , this contribution is given by the Chandrasekhar dynamical friction force [11],

Here, is the velocity dispersion of the background particles (assumed to follow a Maxwellian distribution), which is taken to be km/s [33]. To avoid unphysical results at small distances, we follow [34] and use the regularized Coulomb logarithm,

We use in Equation (28) the globular cluster velocity , because we assume that the averaged velocity of the baryonic matter is zero.

Note that since the acceleration due to the dynamical force is proportional to the probe mass M, one would expect the effect of mass segregation, i.e., the tendency of more massive objects to lose kinetic energy through dynamical friction and gradually sink toward the galactic center, while less massive objects remaining at larger distances [35].

Further, since the dynamical friction force scales with the square of the mass of the moving object, its impact on globular clusters is expected to be significantly stronger than in the case of individual stars because GCs are much more massive than stars. As a result, globular clusters serve as particularly sensitive probes of dynamical friction effects in dark matter halos. Observationally, the survival of globular clusters at their present-day distances implies that the corresponding characteristic timescale must be of order , comparable to or exceeding the age of the Universe.

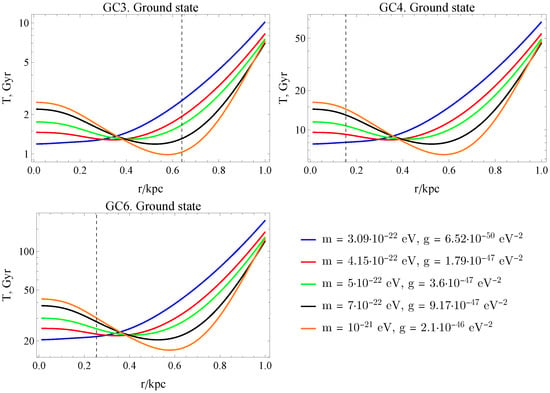

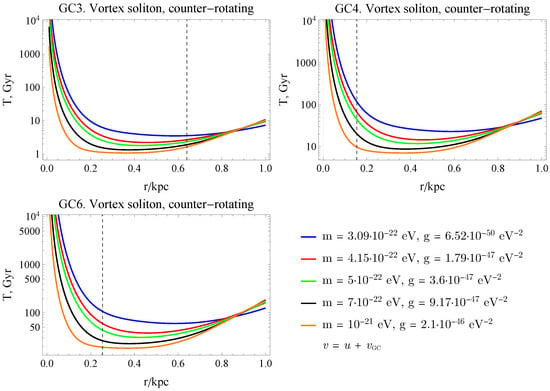

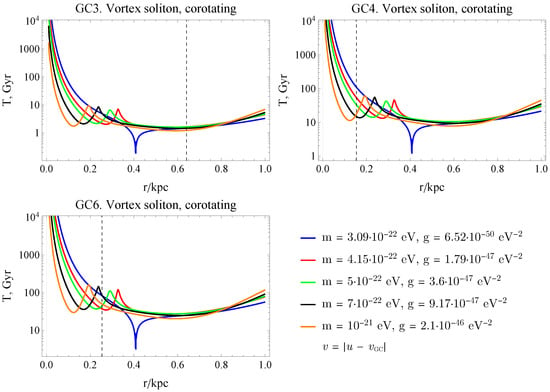

Using Equation (18), we computed the characteristic timescales for three globular clusters, specified by their masses and current projected distances from the galactic center: GC3 (, kpc), GC4 (, kpc), and GC6 (, kpc). The analysis was carried out for both the solitonic ground state and the rotating vortex configurations of the ULDM halo, assuming that the clusters are located in the equatorial plane . The calculations were performed using the numerical and analytical techniques developed in [36].

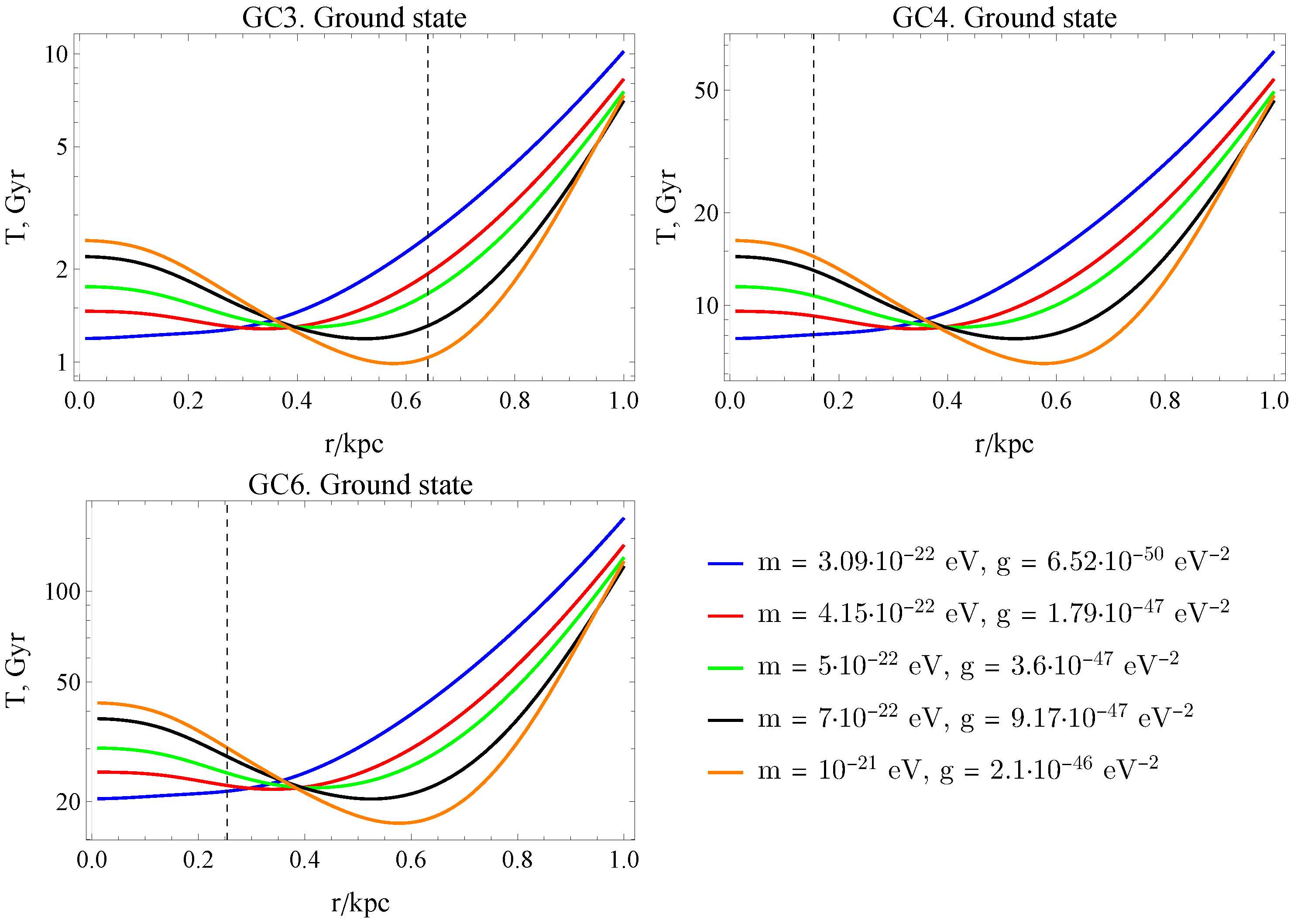

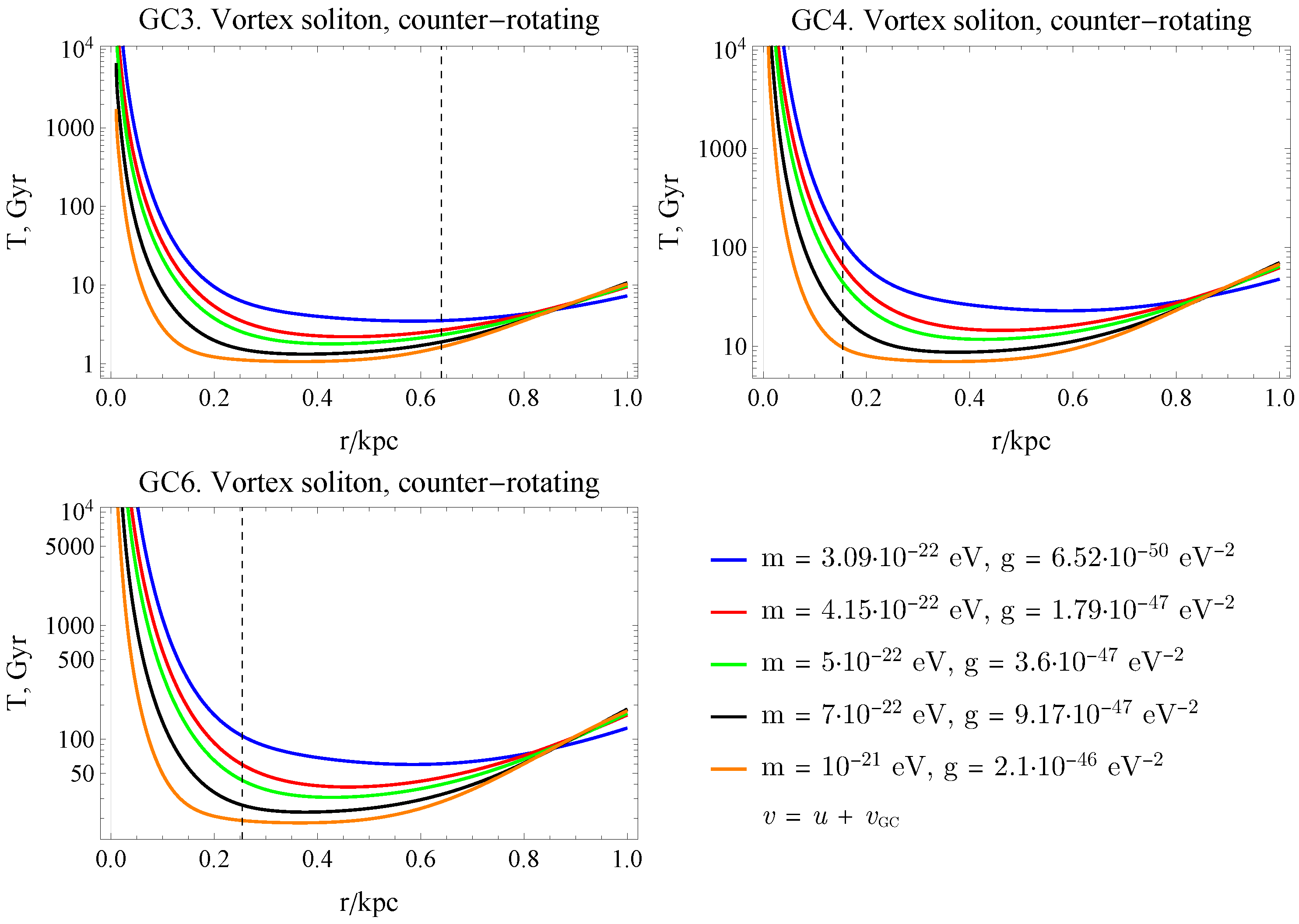

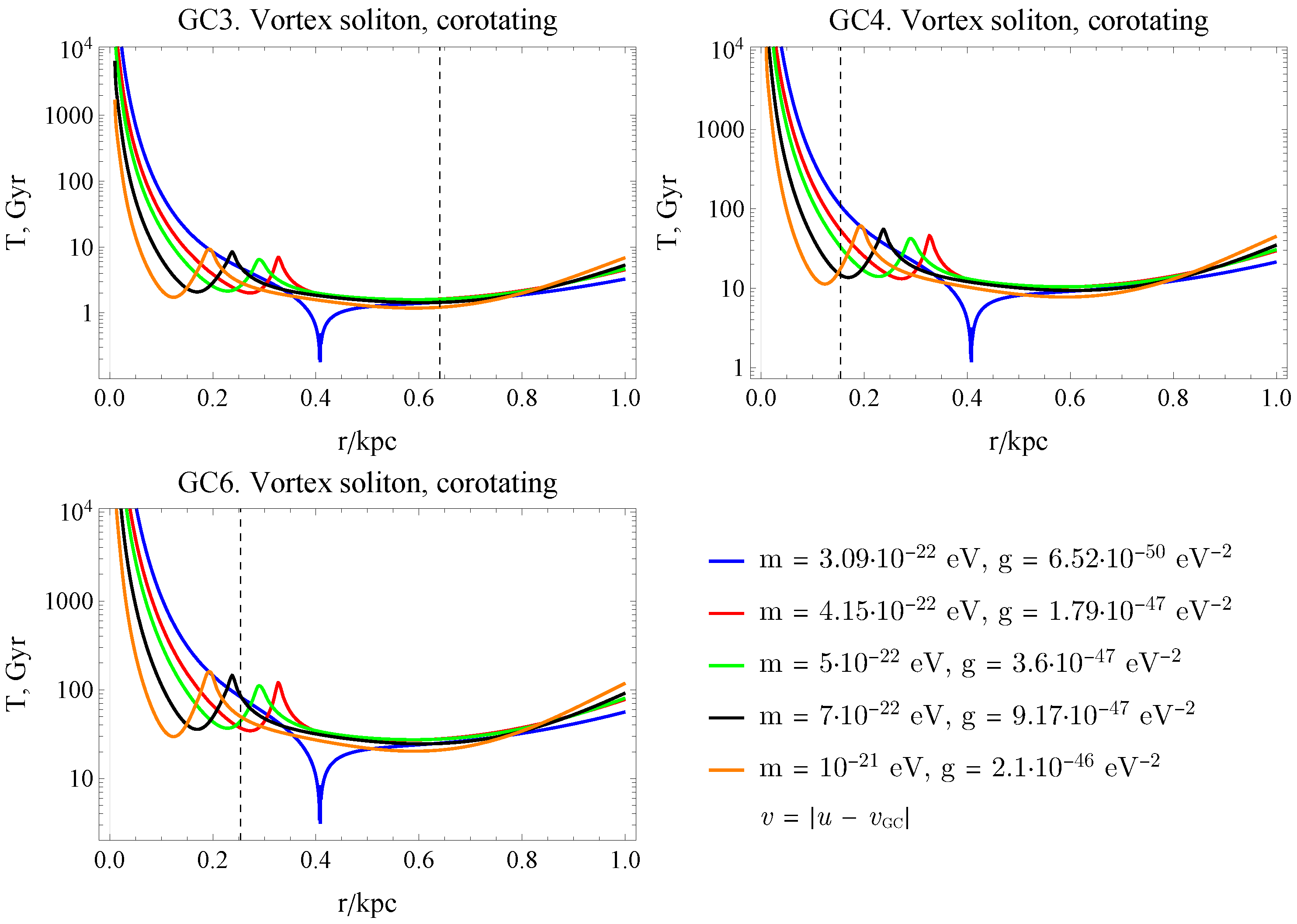

The resulting characteristic times of the velocity substantial change are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. A pronounced modification of the globular cluster dynamics is observed in the presence of a vortex state, particularly in the case of co-directional rotation of the cluster and the ULDM flow, where peaks are clearly seen in Figure 4.

Figure 2.

The characteristic time when GC changes notably its velocity for the spherically symmetric soliton ground state of ULDM at a few values of bosonic particle mass m with the corresponding value of g as a function of its position r from the galactic center. The dotted vertical line shows the current position of a globular cluster.

Figure 3.

The characteristic time when GC changes notably its velocity for the soliton vortex state of ULDM and a few values of bosonic particle mass m with the corresponding value of g as a function of its position r from the galactic center. The direction of rotation of the BEC and the GC is opposite, and the dotted vertical line shows the current position of a globular cluster.

Figure 4.

The characteristic time when GC changes notably its velocity for the soliton vortex state of ULDM and a few values of bosonic particle mass m with the corresponding value of g as a function of its position r from the galactic center. The direction of rotation of the BEC and the GC coincides and the dotted vertical line shows the current position of a globular cluster.

Analyzing the obtained graphical dependencies, one can see that for both the spherically symmetric stationary soliton model and the vortex soliton model, the characteristic time for a significant change in velocity is of the order of 10 Gyr for globular clusters GC4 and GC6.

The GC3 case requires special consideration. For a soliton in the ground state, one can observe a decreasing behavior of the characteristic timescale at distances smaller than 1 kpc and up to the present-day position of GC3. At small distances from the galactic center, the characteristic timescale is only of a few Gyr. In the case of a vortex state of the soliton, a very significant increase in the characteristic timescale at small galactocentric distances is observed. This is related to the sharp decrease in the ULDM density inside the vortex soliton, which has a toroidal structure. In the case of corotation between GC3 and the vortex soliton, notable peaks in the characteristic timescale appear at radii where the relative velocity between the ULDM and GC3 vanishes.

Finally, we would like to add that qualitatively, the effect of a rotating structure in ULDM is similar to the standard core stalling picture in cold DM [37,38,39,40]. As in the case of a cold DM, the dynamical friction force arising in the case of corotation is weakened. This agrees with the classical consideration of dynamical friction by Chandrasekhar [11].

4. Conclusions

We have investigated the impact of a rotating vortex state of ultralight dark matter on the dynamical friction acting on globular clusters moving inside an ultralight dark matter core. By directly comparing the resulting dynamical friction force with that obtained for the non-rotating solitonic ground state, we have demonstrated that the internal structure and quantum state of the ULDM core play a crucial role in determining the orbital evolution of massive substructures. Our analysis shows that the wave nature of ULDM, combined with coherent rotation in the vortex configuration, can substantially modify the effective drag force experienced by globular clusters.

One of key results of this work is the finding that co-directional rotation between the vortex flow of the ULDM halo and the orbital motion of a globular cluster leads to a pronounced suppression of dynamical friction at some distances, leading to the appearance of the peaks in the characteristic time. This effect arises from the reduction in the relative velocity between the cluster and the surrounding dark matter medium, which directly weakens the gravitational wake responsible for dynamical friction.

An inspection of the resulting curves shows that, for both the spherically symmetric stationary soliton and the vortex soliton models, the characteristic timescale associated with a substantial change in velocity gives infall times exceeding the age of Universe for the globular clusters GC4 and GC6 at the current position.

The situation is qualitatively different for GC3 and therefore requires separate discussion. In the case of a soliton in the ground state, the characteristic timescale decreases at galactocentric distances below 1 kpc, remaining reduced up to the present-day location of GC3. In the inner regions of the galaxy, this timescale is only a few Gyrs.

For a vortex soliton, by contrast, the characteristic timescale exhibits a pronounced growth at small galactocentric radii. This behavior can be attributed to the strong suppression of the ULDM density in the inner region of the vortex soliton, which has a toroidal density profile. When GC3 corotates with the vortex soliton, distinct peaks in the characteristic time emerge at radii where the relative velocity between the ULDM background and GC3 approaches zero.

More broadly, these findings highlight the importance of going beyond the ground-state description of ultralight dark matter halos and considering rotating configurations when modeling the dynamics of satellite galaxies and their internal stellar systems. The sensitivity of dynamical friction to the internal velocity structure of ULDM halos suggests that globular cluster dynamics can serve as an indirect probe of the quantum state and coherence properties of dark matter. Future observational constraints on globular cluster orbits, combined with improved modeling of ULDM halo configurations, may therefore provide a novel avenue for testing ultralight dark matter scenarios and distinguishing them from conventional cold dark matter models.

The obtained results for the characteristic time of globular clusters indicate the importance of further research on the evolution of globular clusters from a starting point to their current position.

For a vortex soliton state of DM, an interesting question for further investigation is the consideration of a stellar bar embedded in ULDM halo of the galaxy, because the torque force is significantly different from that in a standard cold dark matter halo [41]. Such consideration can place important constraints on the mass of ULDM particles forming the halo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision and original draft preparation, E.G. and V.G.; numerical computation, A.Z.; formal analysis, O.B. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, T.G. and K.K.; validation and visualization, O.B. and O.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

K.K. acknowledges funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2123 Quantum Frontiers—390837967. The work of E.G., V.G., T.G. and A.Z. was partially supported by the project ‘Search for dark matter and particles beyond the Standard Model’ of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine 25BF051-01. The work of O.T. was partially supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (project No. 0124U001660).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pace, A.B.; Walker, M.G.; Koposov, S.E.; Caldwell, N.; Mateo, M.; Olszewski, E.W.; Bailey Iii, J.I.; Wang, M.Y. Spectroscopic confirmation of the sixth globular cluster in the Fornax dwarf spheroidal galaxy. Astrophys. J. 2021, 923, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Lin, D.; Richer, H. Globular clusters in the Fornax dwarf spheroidal galaxy. Astrophys. J. 2000, 531, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, N.; Navarro, J.; Santos-Santos, I.; Benitez-Llambay, A.; Frenk, C. Cusp or core? Revisiting the globular cluster timing problem in Fornax. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2020, 491, 3336–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, N.; Blas, D.; Blum, K.; Kim, H. Assessing the Fornax globular cluster timing problem in different models of dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 043021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D.J.E. Axion Cosmology. Phys. Rept. 2016, 643, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W. Brief History of Ultra-light Scalar Dark Matter Models. EPJ Web Conf. 2018, 168, 06005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.G.M. Ultra-light dark matter. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2021, 29, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, T.; Ureña López, L.A.; Lee, J.W. Short review of the main achievements of the scalar field, fuzzy, ultralight, wave, BEC dark matter model. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2024, 11, 1347518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schive, H.Y. Fuzzy dark matter simulations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbar, E.V.; Barabash, O.V.; Gorkavenko, V.M.; Korshynska, K.; Momot, A.I.; Zaporozhchenko, A.O. Damping of dynamical friction force in self-interacting ultralight dark matter and Fornax timing problem. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.06123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, S. Dynamical friction. Astrophys. J. 1943, 97, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, H.; Hoyle, F. On the Mechanism of Accretion by Stars. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 1944, 104, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokuchaev, V. Emission of Magnetoacoustic Waves in the Motion of Stars in Cosmic Space. Sov. Astron. 1964, 8, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman, M.; Spiegel, E. Galactic Wakes. Astrophys. J. 1971, 165, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rephaeli, Y.; Salpeter, E. Flow past a massive object and the gravitational drag. Astrophys. J. 1980, 240, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostriker, E.C. Dynamical friction in gaseous medium. Astrophys. J. 1999, 513, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmet, X. (Ed.) Quantum Aspects of Black Holes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaieva, Y.O.; Olashyn, A.O.; Kuriatnikov, Y.I.; Vilchynskii, S.I.; Yakimenko, A.I. Stable vortex in Bose-Einstein condensate dark matter. Low Temp. Phys. 2021, 47, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshynska, K.; Bidasyuk, Y.M.; Gorbar, E.V.; Jia, J.; Yakimenko, A.I. Dynamical galactic effects induced by solitonic vortex structure in bosonic dark matter. Eur. Phys. J. C 2023, 83, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavanis, P.H. Mass-radius relation of Newtonian self-gravitating Bose-Einstein condensates with short-range interactions: I. Analytical results. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 043531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, H.C. On the problem of distribution in globular star clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1911, 71, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellari, M.; Bacon, R.; Bureau, M.; Damen, M.; Davies, R.L.; De Zeeuw, P.T.; Emsellem, E.; Falcón-Barroso, J.; Krajnovic, D.; Kuntschner, H.; et al. The SAURON project—IV. The mass-to-light ratio, the virial mass estimator and the Fundamental Plane of elliptical and lenticular galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 366, 1126–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, K.; del Pino, A.; Łokas, E.L.; Valluri, M. Schwarzschild dynamical model of the Fornax dwarf spheroidal galaxy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 482, 5241–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavanis, P.H. Mass-radius relation of self-gravitating Bose-Einstein condensates with a central black hole. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2019, 134, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, A.S.; Levkov, D.G.; Panin, A.G.; Pushnaya, E.K.; Tkachev, I.I. Instability of rotating Bose stars. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 023504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardel, J.R.; Gebhardt, K. The dark matter density profile of the Fornax dwarf. Astrophys. J. 2012, 746, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorkavenko, V.M.; Yakimenko, A.I.; Zaporozhchenko, A.O.; Gorbar, E.V. Dynamical friction in ultralight dark matter: Plummer sphere perspective. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 075039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabash, O.V.; Gorkavenko, T.V.; Gorkavenko, V.M.; Teslyk, O.M.; Yakovenko, N.S.; Zaporozhchenko, A.O.; Gorbar, E.V. Analytic calculation of dynamical friction for Plummer sphere in ultralight dark matter. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.06448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjacques, V.; Nusser, A.; Buehler, R. Analytic Solution to the Dynamical Friction Acting on Circularly Moving Perturbers. Astrophys. J. 2022, 928, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, R.; Desjacques, V. Dynamical friction in fuzzy dark matter: Circular orbits. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 023516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Ostriker, J.P.; Tremaine, S.; Witten, E. Ultralight scalars as cosmological dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 043541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezhiani, L.; Cintia, G.; De Luca, V.; Khoury, J. Dynamical friction in dark matter superfluids: The evolution of black hole binaries. JCAP 2024, 06, 024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.G.; Mateo, M.; Olszewski, E.W.; Gnedin, O.Y.; Wang, X.; Sen, B.; Woodroofe, M. Velocity Dispersion Profiles of Seven Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2007, 667, L53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, N.; Danieli, S.; Blum, K. Dynamical Friction in Globular Cluster-rich Ultra-diffuse Galaxies: The Case of NGC5846-UDG1. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 932, L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binney, J.; Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gorkavenko, V.M.; Barabash, O.V.; Gorkavenko, T.V.; Teslyk, O.M.; Zaporozhchenko, A.O.; Jia, J.; Yakimenko, A.I.; Gorbar, E.V. Dynamical friction in rotating ultralight dark matter galactic cores. Class. Quant. Grav. 2024, 41, 235013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, J.A.; Gualandris, A.; Read, J.I. A semi-analytic dynamical friction model that reproduces core stalling. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 454, 3778–3791, Erratum in Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 2337–2338. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stw1151.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Stone, N.C. Density wakes driving dynamical friction in cored potentials. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 515, 407–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, U.; van den Bosch, F.C. A Self-consistent, Time-dependent Treatment of Dynamical Friction: New Insights Regarding Core Stalling and Dynamical Buoyancy. Astrophys. J. 2021, 912, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cintio, P.; Marcos, B. A disturbance in the force: How force fluctuations hinder dynamical friction and induce core stalling. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 700, A230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.D. Evolution of barred galaxies by dynamical friction. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1985, 213, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.