Abstract

We present a comprehensive study of variable stars in the young open cluster NGC 663, combining ground-based 50BiN photometry, space-based TESS time-series observations, and astrometric measurements from Gaia DR3. A total of 60 variable candidates were identified, and 46 of them appear consistent with B-type variables according to their effective temperatures and spectral classifications. Cross-matching with the VSX catalog shows that variability of 31 objects has been reported previously, while 29 have no prior entries. Using Gaia astrometry, we estimated membership probabilities and found that 40 of the B-type variables are likely associated with the cluster. Light-curve morphology, frequency analysis, and spectral information suggest a mixture of variability types, including seven candidate Cygni stars, three Cephei variables, ten SPB candidates, one possible BCEP/SPB hybrid, twenty Be stars, and five additional variables. These results indicate that NGC 663 provides a valuable environment for studying variability phenomena in massive stars across a range of evolutionary stages.

1. Introduction

Variable B-type stars form a class of massive, hot, and intrinsically luminous objects whose brightness varies periodically or irregularly over time. Their photometric and spectroscopic variability provides valuable diagnostics of stellar interiors, rotation, and mass-loss processes, while also offering clues to the chemical and structural evolution of galaxies [1,2,3]. Open clusters constitute natural laboratories for investigating such stars, as their members originate from a common molecular cloud, and thus possess nearly uniform ages and chemical compositions [4,5]. Studying variables within such homogeneous stellar populations enables a more precise determination of their physical parameters and a deeper understanding of the mechanisms responsible for their variability [6,7].

Several recent investigations of open clusters have focused on identifying and characterizing variable stars, including B-type members. Li, Gang et al. [8] combined photometric, spectroscopic and asteroseismic analyzes to examine NGC 2516, revealing it as a young, rapidly rotating cluster rich in pulsating members. Wang et al. [9] conducted a comprehensive variability survey of NGC 2355 with the Nanshan One-Meter Wide-Field Telescope, integrating Gaia astrometry and LAMOST spectroscopy to identify 72 newly discovered and 16 previously known variable stars. Zhuo et al. [10] reported 28 variable stars in the young open cluster NGC 869 based on the 50BiN (see Section 2.1) survey, including several Cephei and SPB pulsators, Be stars, and eclipsing binaries. Similar efforts on clusters such as NGC 7419, NGC 7209, and NGC 884 [11,12,13] collectively advance our understanding of stellar variability in young stellar systems.

NGC 663 is an open cluster in the Perseus Arm, noted for its rich population of B-type stars and a relatively high proportion of Be stars among Galactic clusters [14]. The presence of numerous emission-line stars in this region was first reported by González and González [15], who found their abundance comparable to that in the well-known Double Cluster in Perseus. Subsequent photometric and spectroscopic surveys (e.g., [16,17,18,19]) confirmed the cluster’s richness in Be stars and revealed that many of its B-type members display distinct forms of photometric or spectroscopic variability. Yu et al. [20] conducted an Hα imaging survey with the Palomar Transient Factory and identified 34 Be stars in NGC 663, corresponding to about 3.5% of the cluster population and showing a bimodal spectral distribution at B0–B2 and B5–B7. Using AstroSat/UVIT [21] data, Nedhath, Sneha et al. [22] detected UV excesses in the majority of Be stars in NGC 663, revealing high-mass sdOB companions in about 70% of the systems and establishing binary interaction as a key channel for Be star formation. Follow-up spectroscopy by Marco et al. [23] refined cluster membership and spectral classifications, showing that while NGC 663 contains numerous Be-type and evolved B-type stars, their overall fraction is moderate. Their analysis also demonstrated that NGC 663 is a young and exceptionally massive system in the Perseus Arm, hosting blue stragglers, blue supergiants, and the Be/X-ray binary RX J0146.9+6121. These characteristics make NGC 663 an ideal environment for studying variability and evolutionary processes among massive B-type stars.

Although the properties of B-type and Be stars in NGC 663 have been extensively characterized, systematic searches for photometric variability within the cluster have remained relatively scarce. Early variability studies were conducted by Pietrzynski [24], who detected two eclipsing binaries, followed by Pietrzynski [25], who identified two additional Be stars, two pulsating variables, and one field Cephei star. The survey was later extended by Pigulski et al. [26], resulting in the discovery of 19 new variable stars. Nevertheless, these studies were constrained by the observational capabilities available at the time, and a more comprehensive time-series analysis using modern large-scale surveys can provide an improved view of stellar variability in the cluster. In this work, we combine time-series photometry from the 50BiN open cluster survey with data from the TESS mission to conduct a comprehensive search for variable stars in NGC 663, with particular attention to massive and luminous B-type variables.

2. Observations and Data Reduction

2.1. 50BiN Photometry

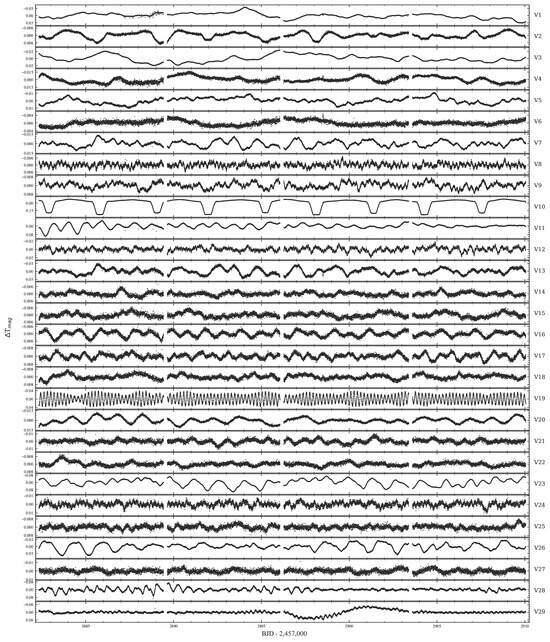

The open cluster NGC 663 was observed using the 50 cm Binocular Network (50BiN) telescope at the Qinghai Station of Purple Mountain Observatory [27,28]. The observations were carried out on 13 October and from 18 to 25 October 2014, spanning a total of nine nights. After excluding data from 21 October due to unfavorable weather conditions, eight nights of usable data were retained. Photometric observations were performed with standard Johnson–Cousins–Bessell B and V filters to obtain two-color photometry. The CCD camera, with a 2K × 2K array, provides a field of view of . A total of 3187 and 7494 frames were obtained in the B and V bands, respectively, with exposure times of 80 s and 30 s. A summary of the observations is given in Table 1. The raw images were processed using an automated reduction pipeline, which included bias subtraction, flat-field correction, astrometric calibration, and photometric extraction. To mitigate weather-induced systematics in the light curves, differential photometry was applied. Six reference stars exhibiting minimal brightness variations (standard deviation < 0.1 mag) were selected through an iterative procedure. As a result, differential light curves were derived for 881 stars. The real-time B- and V-band light curves of 20 B-type variable stars, derived from 50BiN observations, are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Observation Log of NGC 663 Obtained with the 50BiN.

Figure 1.

B-band (blue) and V-band (black) light curves of B-type variable stars obtained from the 50BiN observations. The data points have been vertically shifted by arbitrary offsets to improve the clarity of individual light-curve features. The source IDs shown on the right correspond to the ID column in Table 2.

Table 2.

Basic Parameters of B-type Variable Stars in NGC 663. Variable type codes in the VarType column are defined in Section 5.

Table 2.

Basic Parameters of B-type Variable Stars in NGC 663. Variable type codes in the VarType column are defined in Section 5.

| ID | PMP | Member | SpType | Period | Amplitude | Dataset | VarType | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (deg) | (deg) | (mag) | (mag) | (K) | (dex) | (Days) | (mag) | ||||||

| V1 | 26.520401 | 61.228274 | −0.060 | −5.893 | 0.965 | Yes | 15,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.3 ± 0.1 [1] | B4 Ib [1] | 12.9508 | 0.067 | TESS | ACYG |

| V2 | 26.542574 | 61.442571 | −0.157 | −5.874 | 0.005 | No | 10,000 ± 1000 [1] | 1.9 ± 0.1 [1] | A0 Ib [1] | 3.1180 | 0.013 | TESS | ACYG |

| V3 | 26.599082 | 61.258254 | 0.009 | −5.727 | 0.989 | Yes | 15,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.4 ± 0.1 [1] | B5 Ib [1] | 17.5039 | 0.046 | TESS | ACYG |

| V4 | 26.483806 | 61.234807 | 0.146 | −5.683 | 0.988 | Yes | 12,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.0 ± 0.3 [1] | B8 Ib [1] | 11.8396 | 0.032 | TESS | ACYG |

| V5 | 26.834027 | 61.131942 | −0.213 | −5.631 | 0.985 | Yes | 17,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.7 ± 0.1 [1] | B3 Ib [1] | 12.5217 | 0.022 | TESS | ACYG |

| V6 | 26.787126 | 61.198453 | 0.116 | −5.172 | 0.987 | Yes | 11,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.3 ± 0.1 [1] | B9 Ib [1] | 9.6328 | 0.008 | TESS | ACYG |

| V7 | 26.643889 | 61.262497 | −0.127 | −5.050 | 0.988 | Yes | 18,000 ± 1000 [1] | 2.3 ± 0.1 [1] | B2.5 Ib [1] | 2.1485 | 0.025 | TESS | ACYG |

| V8 | 26.473899 | 61.320573 | −0.642 | −4.798 | 0.906 | Yes | 33,000 ± 1300 [1] | 3.9 ± 0.2 [1] | O9.2 IV [1] | 0.2101 | 0.014 | TESS | BCEP |

| V9 | 26.690350 | 61.502570 | −0.247 | −4.744 | 0.980 | Yes | 29,000 ± 1000 [1] | 3.3 ± 0.1 [1] | B0 III [1] | 1.0981 | 0.015 | TESS | SPB |

| V10 | 26.512580 | 61.441952 | −0.645 | −4.606 | 0.946 | Yes | 17,524 ± 261 [2] | 3.20 ± 0.04 [2] | B3 [3] | 6.1638 | 0.330 | TESS | EB |

| V11 | 26.497122 | 61.212672 | −0.237 | −4.296 | 0.982 | Yes | 17,000 ± 1800 [1] | 3.1 ± 0.2 [1] | B2.5 III [1] | 0.9569 | 0.150 | TESS | BE |

| V12 | 26.750875 | 61.356573 | −0.488 | −4.070 | 0.826 | Yes | 26,000 ± 2100 [1] | 3.7 ± 0.2 [1] | B0.7 IVe [1] | 0.6653 | 0.038 | TESS | BE |

| V13 | 26.648059 | 61.263283 | −0.032 | −3.920 | 0.959 | Yes | 18,000 ± 2200 [1] | 3.4 ± 0.2 [1] | B2.5 IIIe [1] | 2.1490 | 0.060 | TESS | BE |

| V14 | 26.612753 | 61.167197 | −0.071 | −3.894 | 0.988 | Yes | 19,000 ± 1600 [1] | 3.2 ± 0.2 [1] | B2.5 III [1] | 2.2162 | 0.013 | TESS | BE |

| V15 | 26.521383 | 61.307635 | −0.181 | −3.880 | 0.987 | Yes | 17,000 ± 2600 [1] | 3.1 ± 0.3 [1] | B3 III [1] | 3.5784 | 0.014 | TESS | SPB |

| V16 | 26.325106 | 61.115687 | −0.146 | −3.876 | 0.912 | Yes | 18,802 ± 1106 [2] | 2.88 ± 0.35 [2] | B2 IIIe [1] | 1.0257 | 0.013 | TESS | BE |

| V17 | 26.615289 | 61.207066 | 0.045 | −3.852 | 0.987 | Yes | 22,000 ± 2100 [1] | 3.4 ± 0.3 [1] | B2 IIIe [1] | 1.3911 | 0.016 | TESS | BE |

| V18 | 26.529046 | 61.197529 | −0.063 | −3.772 | 0.942 | Yes | 18,000 ± 1000 [1] | 3.1 ± 0.1 [1] | B2.5 III [1] | 2.2549 | 0.017 | TESS | SPB |

| V19 | 26.662483 | 61.235014 | −0.358 | −3.720 | 0.979 | Yes | 24,000 ± 1700 [1] | 3.8 ± 0.2 [1] | B1 IV [1] | 0.1940 | 0.077 | TESS+50BiN | BCEP |

| V20 | 26.641523 | 61.150652 | −0.039 | −3.719 | 0.933 | Yes | 17,000 ± 1700 [1] | 3.0 ± 0.2 [1] | B2 III [1] | 1.3277 | 0.025 | TESS | BE |

| V21 | 26.526389 | 61.275254 | −0.300 | −3.522 | 0.988 | Yes | 17,000 ± 2000 [1] | 3.2 ± 0.3 [1] | B2 III-IV [1] | 1.0417 | 0.021 | TESS | SPB |

| V22 | 26.844777 | 61.350690 | −0.207 | −3.468 | 0.967 | Yes | 18,000 ± 1800 [1] | 3.3 ± 0.2 [1] | B2.5 III [1] | 5.6253 | 0.017 | TESS | SPB |

| V23 | 27.096096 | 61.264735 | −0.132 | −3.436 | 0.985 | Yes | 21,229 ± 877 [2] | 3.65 ± 0.31 [2] | B2Ve [4] | 1.4481 | 0.180 | TESS | BE |

| V24 | 26.672625 | 61.220875 | −0.142 | −3.366 | 0.978 | Yes | 24,000 ± 1500 [1] | 3.8 ± 0.2 [1] | B1 III [1] | 0.2025 | 0.019 | TESS | BCEP/SPB |

| V25 | 26.553045 | 61.130114 | −0.266 | −3.319 | 0.976 | Yes | 19,000 ± 2600 [1] | 3.6 ± 0.3 [1] | B2 IV [1] | 2.6640 | 0.016 | TESS | SPB |

| V26 | 26.611846 | 61.128253 | 0.199 | −3.204 | 0.986 | Yes | 26,778 ± 3295 [2] | 3.66 ± 0.85 [2] | B2 IIIe [1] | 1.4422 | 0.070 | TESS+50BiN | BE |

| V27 | 26.290020 | 61.203771 | −0.047 | −2.532 | 0.005 | No | 20,350 ± 218 [2] | 3.66 ± 0.03 [2] | B2.5 III-IV [1] | 1.5951 | 0.019 | TESS | SPB |

| V28 | 26.648359 | 61.227522 | −0.078 | −2.329 | 0.978 | Yes | 26,305 ± 853 [2] | 4.15 ± 0.31 [2] | B2.5Ve [1] | 0.5575 | 0.170 | TESS+50BiN | BE |

| V29 | 26.407582 | 61.133079 | −0.072 | −2.193 | 0.979 | Yes | 25,116 ± 530 [2] | 4.35 ± 0.24 [2] | B2Ve [1] | 35.562 | 0.130 | TESS | BE/HB |

| V30 | 26.627644 | 61.241451 | 0.053 | −2.181 | 0.982 | Yes | 26,157 ± 1046 [2] | 4.14 ± 0.42 [2] | B2Ve [1] | 8.1675 | 0.210 | 50BiN | BE |

| V31 | 26.765613 | 61.292234 | 0.056 | −2.181 | 0.986 | Yes | 29,933 ± 1723 [2] | 4.19 ± 0.40 [2] | B2.5Ve [1] | 0.7617 | 0.170 | 50BiN | BE |

| V32 | 26.439829 | 61.182104 | 0.016 | −1.853 | 0.953 | Yes | 24,000 ± 1000 [1] | 4.2 ± 0.1 [1] | B2.5Ve [1] | 0.3086 | 0.044 | 50BiN | BE |

| V33 | 26.405690 | 61.196438 | −0.104 | −1.788 | 0.980 | Yes | 20,253 ± 230 [2] | 3.81 ± 0.03 [2] | B2.5V [1] | 1.2416 | 0.058 | 50BiN | SPB |

| V34 | 26.415064 | 61.216421 | 0.050 | −1.747 | 0.988 | Yes | 22,533 ± 766 [2] | 3.65 ± 0.27 [2] | B2.5Ve [1] | 2.5648 | 0.052 | 50BiN | BE |

| V35 | 26.665727 | 61.164405 | −0.087 | −1.680 | 0.984 | Yes | 19,036 ± 184 [2] | 3.60 ± 0.02 [2] | B2.5V [1] | 0.2764 [5] | 0.065 | 50BiN | BCEP |

| V36 | 26.619252 | 61.230671 | −0.053 | −1.572 | 0.903 | Yes | 18,865 ± 235 [2] | 3.85 ± 0.04 [2] | 0.3576 | 0.075 | 50BiN | BE | |

| V37 | 26.584278 | 61.239326 | 0.154 | −1.509 | No | 17,000 ± 1000 [1] | 3.8 ± 0.1 [1] | B2.5 IV-Ve [1] | 0.8773 | 0.092 | 50BiN | BE | |

| V38 | 26.823158 | 61.350635 | −0.615 | −1.464 | 0.855 | Yes | 18,331 ± 649 [2] | 4.09 ± 0.38 [2] | 21.760 [6] | 0.280 | 50BiN | ROT | |

| V39 | 26.612125 | 61.236437 | 0.218 | −1.416 | No | 19,000 ± 2000 [1] | 3.9 ± 0.2 [1] | B3Ve [1] | 0.9530 | 0.110 | 50BiN | BE | |

| V40 | 26.664775 | 61.109835 | −0.039 | −1.102 | 0.988 | Yes | 18,799 ± 197 [2] | 3.92 ± 0.03 [2] | B3Ve [1] | 0.4927 | 0.060 | 50BiN | BE |

| V41 | 26.652408 | 61.186219 | −0.180 | −0.842 | 0.853 | Yes | 15,843 ± 210 [2] | 4.39 ± 0.05 [2] | B7V [1] | 2.5235 | 0.066 | 50BiN | SPB |

| V42 | 26.558436 | 61.228841 | 0.277 | −0.516 | No | 18,800 ± 208 [2] | 3.60 ± 0.03 [2] | B3Ve [1] | 1.1017 | 0.059 | 50BiN | BE | |

| V43 | 26.525562 | 61.139956 | −0.138 | −0.425 | 0.987 | Yes | 16,058 ± 248 [2] | 4.23 ± 0.16 [2] | 1.1412 | 0.075 | 50BiN | SPB | |

| V44 | 26.611065 | 61.284924 | −0.102 | −0.213 | 0.980 | Yes | 17,910 ± 487 [2] | 4.14 ± 0.29 [2] | 1.3066 | 0.100 | 50BiN | ELL | |

| V45 | 26.531924 | 61.133273 | 0.033 | 0.414 | 0 | No | 16,415 ± 294 [2] | 4.33 ± 0.18 [2] | 4.9027 | 0.100 | 50BiN | VAR | |

| V46 | 26.358236 | 61.180606 | 0.204 | 0.918 | 0.984 | Yes | 14,511 ± 479 [2] | 4.44 ± 0.28 [2] | 0.2610 | 0.150 | 50BiN | VAR |

References: [1] Marco et al. [23]; [2] Gaia Collaboration et al. [29]; [3] Ge et al. [30]; [4] McCuskey et al. [31]; [5] Pigulski et al. [26]; [6] Jayasinghe et al. [32].

2.2. Archival Data from TESS and Gaia DR3

The Gaia data are crucial for determining cluster membership and constructing precise Hertzsprung–Russell diagrams. In this study, adopting the central coordinates of NGC 663 as , , we retrieved 24,127 sources from the Gaia DR3 catalog [29] within a radius of . We applied quality filters to ensure data reliability. First, we excluded all sources with missing values in any of the five fundamental astrometric parameters (, , , , and parallax) or in the photometric magnitudes. Finally, only sources with positive parallaxes () were retained after applying the zero-point correction described by Lindegren, L. et al. [33].

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS; Ricker et al. [34]) provides high-precision photometric time-series data that are invaluable for studying stellar variability. Observations of the NGC 663 region were obtained in TESS Sector 58, spanning the period from 29 October 2022 to 26 November 2022, with a cadence of 2 min. Using the Gaia source catalog as the reference, we cross-matched the coordinates with the TESS Input Catalog (TIC) within a tolerance of 1 arcsecond. TIC sources with a TESS magnitude (Tmag) greater than 16 were excluded. We programmatically queried and downloaded the light-curve data products from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), which were processed by the TESS Science Processing Operations Center (SPOC) pipeline. This procedure yielded Target Light Curve files for 36 sources, among which 29 are B-type stars and the remaining 7 (T1–T7) are listed in Table 3. Notably, three sources (V19, V26, and V28) are common to both the 50BiN and TESS samples. Figure 2 shows the TESS light curves of B-type variable stars, with the mean magnitude of each star subtracted to emphasize their variability features.

Table 3.

Basic Parameters of the non–B-type variable candidates in NGC 663.

Figure 2.

TESS light curves of B-type variables, with the mean magnitude subtracted to emphasize variability features. The y-axes have different ranges depending on the variability amplitude. Target IDs on the right refer to the ID column in Table 2.

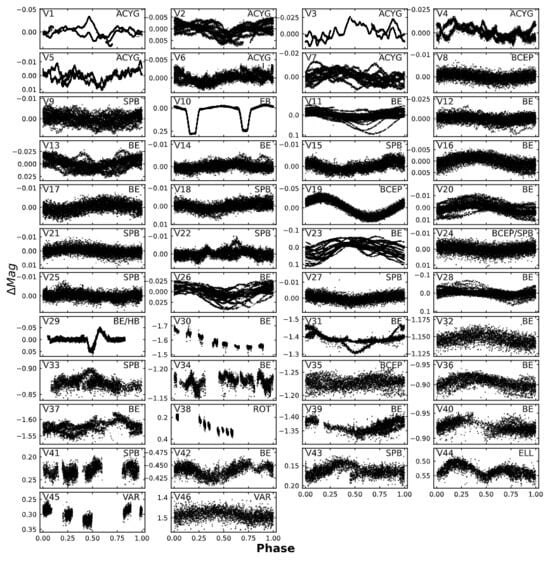

2.3. Identification of Variable Stars

Variable star candidates were identified through visual inspection of all available light curves and analysis of their Lomb–Scargle periodograms [39,40]. Using the 50BiN and TESS time-series data, we identified a total of 60 variable star candidates, comprising both B-type and non-B-type stars. To verify our results, we cross-matched the sample with the International Variable Star Index (VSX)1. The cross-match confirmed that 31 of our candidates are listed as known variable stars in VSX, whereas the remaining 29 are not included in the data base. The candidate variables were divided into two categories according to their spectral properties and effective temperatures: B-type stars and other variables. The primary focus of this study is on the 46 B-type variable stars identified in NGC 663. Fourteen additional variables of other types were also detected and are presented separately as supplementary results. The B-type variables are listed in Table 2, while the remaining sources are compiled in Table 3 and briefly described in Appendix A. Each table provides the following parameters: astrometric data from Gaia DR3; colors and magnitudes derived from Gaia multi-band photometry, corrected for extinction; proper membership probability (PMP) and membership status (Member) based on astrometric parameters (see Section 3); and effective temperature, surface gravity, and spectral type primarily adopted from Marco et al. [23] and Gaia Collaboration et al. [29]. The dominant periods adopted for classification were derived from frequency analyses performed with the Period04 software, version 1.2.9.3 [41]. Using the periods summarized in Table 2, we constructed phase-folded light curves for all 46 B-type variables, which are presented in Figure 3. We also include the variability amplitude, defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum magnitudes after applying a 3- clipping to the light curves, as well as a “Dataset” column indicating the observational source (50BiN, TESS, or both). The final column lists the adopted variability classification(VarType). A detailed discussion of the variability classification and the corresponding criteria will be described and discussed in Section 5.

Figure 3.

Phase-folded light curves of the 46 B-type variable stars identified in NGC 663, constructed using the dominant periods listed in Table 2.

3. Cluster Membership

Accurate determination of cluster membership is a fundamental prerequisite for studying variable stars in open clusters. However, this task is often complicated by contamination from foreground and background field stars located along the Galactic plane. The high-precision astrometric data provided by the Gaia mission enable reliable separation of genuine cluster members from field stars through their consistent parallaxes and proper motions [42]. In this work, we determine membership probabilities for individual stars using the ML-MOC method proposed by Agarwal et al. [43], which operates in the three-dimensional kinematic space defined by Gaia proper motions and parallax. The procedure is divided into two stages: first, the k-nearest neighbors (kNN) algorithm is employed to prepare a robust sample of sources, after which membership probabilities are calculated using a two-component Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM).

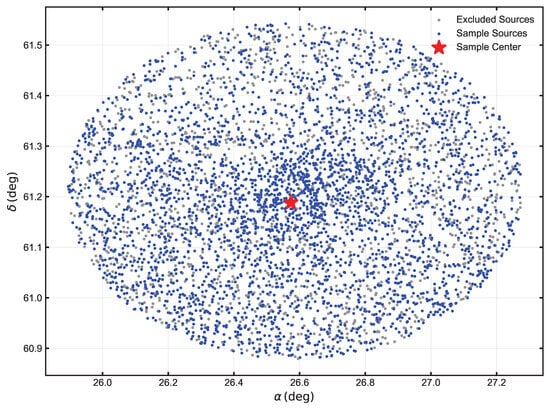

3.1. Sample Preparation via kNN Filtering

The effective application of the GMM framework requires high-quality input data, characterized not only by high precision but also by sufficient contrast in the relative densities of member and field stars [44]. To achieve this, we employed the kNN algorithm, a non-parametric machine-learning approach, to estimate the cluster’s mean astrometric parameters of the cluster. The kNN regression yielded a mean proper motion of mas and a mean parallax of mas for the cluster. Based on these values, an initial astrometric selection window of 5 mas in proper motion and mas in parallax was defined. The selection region was then refined iteratively, with its center adjusted until the mean parameters of the enclosed sources converged toward the kNN-derived estimates. This pre-processing step efficiently reduced field-star contamination, yielding a cleaned sample of 3294 sources for subsequent classification. The spatial distribution of the selected sample is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of the selected sources in NGC 663 obtained through the kNN pre-filtering process.

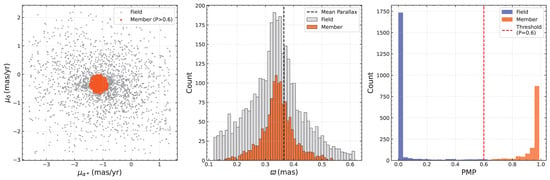

3.2. Membership Classification with a Two-Component GMM

The final membership classification was carried out using a GMM in the three-dimensional astrometric space (, , ), following the procedure of McLachlan and Peel [45]. The astrometric parameters were first standardized using the StandardScaler algorithm:

where denotes the original value of the j-th parameter for the i-th source, while and correspond to the median and standard deviation of that parameter, respectively. N represents the total number of sources, and the number of dimensions is three. The GMM was implemented using the scikit-learn library, configured with two components, full covariance matrices, and the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to maximize the likelihood function. The standardized three-dimensional vectors (, , ) for all sources were provided as input to the model. The Gaussian component exhibiting the larger mean parallax was assigned to the cluster population. Based on the membership probabilities from the model, we classified sources with probabilities exceeding 0.6 as high-probability members. This criterion yielded 1311 member stars, with the remaining sources designated as field stars. The resultant distribution is shown in the histogram in Figure 5. It should be noted that several sources, namely V37, V39, and V42 in Table 2, as well as T10, T11, T13, and T14 in Table 3, were excluded during the initial source selection process using the kNN algorithm. As a result, reliable membership probability values could not be assigned to these objects, and they are therefore most likely field stars.

Figure 5.

Membership probability distribution from the two-component GMM.

To assess the consistency of our membership classification with previous studies, we performed a cross-validation against the results of Hunt, Emily L. and Reffert, Sabine [46], who derived cluster memberships from Gaia EDR3 data using the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm. In that work, a membership probability threshold of 0.5 was adopted to define reliable members. A statistical comparison indicates that the agreement between the two membership determinations reaches 93.06%, suggesting good consistency and supporting the reliability of the classification adopted in this study.

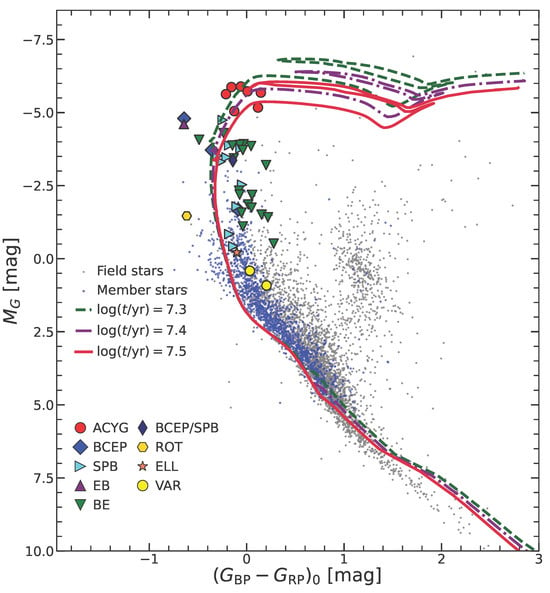

4. Color-Magnitude Diagram

The color–magnitude diagram (CMD) is a fundamental tool for probing stellar evolution and assessing the physical properties of star clusters. Previous investigations [14,47] have reported substantial and spatially variable reddening across NGC 663, indicating that stars within the cluster experience markedly different levels of extinction. To obtain a reliable intrinsic CMD, we applied extinction corrections to the Gaia DR3 photometry on a star-by-star basis. The values for all Gaia targets, including both cluster members and field stars, were derived from the Bayestar19 three-dimensional dust map [48], using the Gaia sky positions and parallax-based distance estimates as inputs. The resulting reddening values were converted into band-specific extinction in the Gaia passbands using the coefficients of Casagrande and VandenBerg [49], following

where denotes the colour excess in the Gaia passbands. The coefficients , , and are the corresponding extinction factors from Casagrande and VandenBerg [49]. The intrinsic colour and magnitude, and , are obtained from the observed quantities and after removal of the line-of-sight extinction, with representing the attenuation in the G passband. After dereddening, the corrected magnitudes were converted to absolute magnitudes using the Gaia parallaxes, enabling construction of the intrinsic color–magnitude diagram in Figure 6. High-probability members (PMP > 0.6) are shown in blue, while field stars are displayed in grey. Overplotted on the diagram are three theoretical isochrones generated with the CMD 3.82 tool [50,51] for a metallicity of dex. The green, purple, and red curves represent stellar populations with ages of , , and , respectively. The age and metallicity of NGC 663, as determined by Angelo et al. [52], Cantat-Gaudin, T. et al. [53], Dias et al. [54], and Hunt, Emily L. and Reffert, Sabine [46].

Figure 6.

Dereddened color–magnitude diagram of NGC 663 based on Gaia DR3 photometry. High-probability members (PMP > 0.6) are shown in blue, and field stars in grey. Variable stars identified in this study are highlighted using distinct symbols according to their variability types. Isochrones generated with the CMD 3.8 tool for dex are shown in green, purple, and red for ages of = 7.3, 7.4, and 7.5, respectively.

5. Classification and Properties of Massive Variable Stars

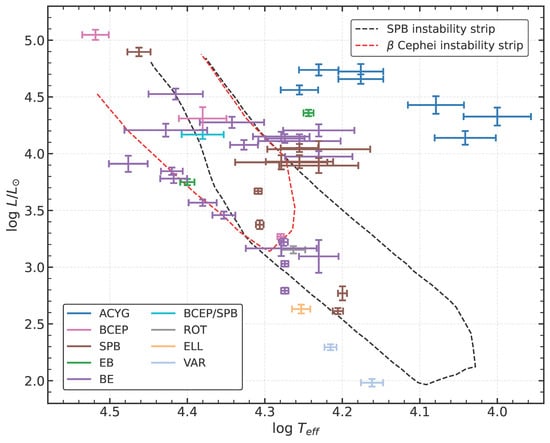

To investigate the nature of the detected massive variables, we also constructed a Hertzsprung–Russell (H–R) diagram for the 46 B-type candidates, as shown in Figure 7. The red and dark dashed curves mark the predicted instability strips for Cephei (BCEP) and slowly pulsating B (SPB) stars, respectively, based on the models of Miglio et al. [55]. By combining the morphology of the light curves, the positions of the stars in the color–magnitude diagram, and their locations relative to the theoretical instability regions, we classified the variables into distinct variability types. In addition, Appendix B (Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3) presents amplitude spectra of representative B-type variables, which are included to assist in the variability classification.

Figure 7.

Hertzsprung–Russell diagram of the 46 B-type variable candidates. The dashed red and dark curves indicate the theoretical instability strips for BCEP and SPB stars [55]. Variable types were assigned based on light-curve morphology, CMD position, and proximity to these instability regions.

5.1. ACYG

The objects V1–V7 are luminous B- and A-type supergiants [23] and are considered candidate Cyg variables (ACYG). Their effective temperatures span – K, with luminosities in the range –. Their light curves exhibit irregular, low-amplitude variability (<0.1 mag) with periods of 2.15–17.50 days, consistent with the photometric behavior commonly associated with ACYG stars. In the H-R diagram (Figure 6 and Figure 7), these stars fall within the luminous B–A supergiant regime above the main sequence. This locus falls between the instability regions of main-sequence B-type pulsators and evolved massive stars, matching the expected domain of ACYG variability.

5.2. BCEP

V8, V19, V24, and V35 are classified as candidate BCEP variables. V8 (O9,2 IV) lies near the hot and luminous boundary of the theoretical BCEP instability region, and its dominant TESS period of 0.2101 d falls within the expected range of low-order p-mode oscillations, suggesting that it may be an early-type extension of the BCEP class. V19 and V35 have spectral types (B1–B2.5, luminosity classes III–V) and positions in the H–R diagram that place them within or near the predicted BCEP instability region. Their variability properties are broadly compatible with BCEP-like pulsations. V19 and V35 were previously reported as BCEP stars [26], and the period recovered for V19 in this study (0.1940 d) matches earlier work. V24 (B1 III) displays a dominant p-mode frequency at 0.2025 d together with several low-frequency signals around 1 , and its location in the H–R diagram coincides with the region where BCEP and SPB instability boundaries overlap. These characteristics point to a mixed-mode pulsator exhibiting both pressure and gravity modes.

5.3. SPB

V9, V15, V18, V21, V22, V25, V27, V33, V41, and V43 are considered plausible SPB candidates. V9 lies near the hot, luminous boundary between the SPB and BCEP instability regions. Although its spectral type (B0 III) falls within the classical range expected for BCEP stars (B0–B2), its variability is clearly multiperiodic: the dominant period is 1.0981 d, accompanied by an additional signal at 3.5842 d. These low-frequency variations are more in line with the g-mode characteristics commonly associated with SPB stars. For the remaining objects, the detected variability is concentrated in the low-frequency domain (periods of approximately ≈ 1–5.6 days), and no convincing p-mode oscillations are present, making a BCEP classification unlikely. Their spectral types (B2–B7) and luminosity classes (III–V) are consistent with the parameter space commonly associated with SPB stars. In the H-R diagram (Figure 7), all the candidates are located on or close to the predicted SPB instability region, consistent with an SPB-like classification. With the exception of V27, all stars discussed here appear to be likely members of NGC 663.

5.4. Be

Be stars are rapidly rotating B-type objects characterized by Balmer emission lines, generally attributed to a surrounding circumstellar disk. Both rapid rotation and stellar pulsation are known to play key roles in shaping their variability [2]. In this work, we compiled a sample of 20 Be stars based on recent spectral classifications [23] and previously reported emission-line identifications from the literature (e.g., V11: Pigulski et al. [19]; V20: Schild and Romanishin [16]; V23: McCuskey et al. [31], Stephenson and Sanduleak [56], Sanduleak [17], Kohoutek and Wehmeyer [57]; V36: Mathew and Subramaniam [58]). These sources are flagged as “BE” in the VarType column of Table 2. We visually examined their light curves and performed frequency analyses using Period04 software. Our results reveal that most Be stars exhibit non-sinusoidal variability dominated by low-frequency signals (0–6 ), a pattern broadly consistent with g-mode pulsations. This behavior suggests that nearly all Be stars in our sample display photometric behavior typical of SPB stars. These findings support the scenario in which Be stars may represent a more complex extension of SPB stars, possibly at the extreme end of SPB pulsational activity accompanied by outbursts [59].

The binary properties of Be stars also deserve consideration. Using ultraviolet photometry from AstroSat/UVIT [21], Nedhath, Sneha et al. [22] modeled the spectral energy distributions of the cluster’s Be stars with both single- and binary-star scenarios, finding that a substantial fraction—on the order of ∼70%—is better explained by binary interaction and past mass transfer. Cross-matching our Be sample with their results identifies ten systems (V13, V14, V17, V26, V28, V29, V30, V34, V36, and V42) as likely Be binaries. For V30, an analysis of the detrended light curve reveals short-timescale variations in the first observing night, but no statistically significant frequency is found when considering the entire time series.

Among all the Be stars in our sample, V12 and V29 exhibit distinctive characteristics. V12 shows a significant high-frequency signal at 9.68 , which lies beyond the typical range of g-mode pulsations. This object is also the only Galactic X-ray binary associated with an open cluster, having been identified in previous studies as a high-mass X-ray binary and a bright X-ray source [60,61]. Its companion is classified as a neutron star. The light curve and phase diagram of V29 indicate that it belongs to a special class of binary systems known as Heartbeat(HB) stars. Its phased light curve morphology resembles the characteristic “heartbeat” signature, with a sharp peak near periastron resulting from a combination of tidal distortion, heating effects, and Doppler boosting [62]. This system is not only an emission-line binary but also a highly eccentric one. Since TESS Sector 58 captured only one brightening event, the true orbital period must be longer than 35.562 days. Determining its precise orbital period will require additional long-term photometric coverage.

5.5. Other B-Type Variables

In addition to the B-type variables discussed above, five objects exhibiting other forms of variability were identified: V10 (eclipsing binary), V38 (rotational variable), V44 (ellipsoidal variable), and V45 and V46, which we classify as general variable (VAR) candidates. V10 displays a clear eclipsing-binary morphology. We derive an orbital period of 6.1638 d, in good agreement with the value of 6.161 d listed in the VSX catalog. This source appears to be a likely member of NGC 663. V38, also a cluster member and with an effective temperature of 18,331 K (B-type), has been listed as a rotational variable with a 21.7 d period by Jayasinghe et al. [32]. Although the time coverage of our 50BiN data is limited, the light curve exhibits a monotonic trend that likely samples part of a longer rotational modulation cycle. After removing this long-term trend, the residual light curve does not show any significant short-timescale variability or detectable periodic signal. V44 exhibits the characteristic modulation pattern of an ellipsoidal binary (ELL), consistent with the classification proposed by Pigulski et al. [26]. Using the Phase Dispersion Minimization (PDM) method, we derive an orbital period of 1.3066 d. This result is consistent with the previously reported value of 1.3077 d.

V45 and V46 were previously reported as RS CVn-type variables [38]. However, their effective temperatures place them among early-type B stars, whereas classical RS CVn systems are typically composed of late-type (F–K) components. In addition, their light curves do not exhibit the quasi-periodic, spot-induced modulation characteristic of RS CVn binaries. Given the lack of supporting spectroscopic evidence and the limited time baseline, we therefore regard the RS CVn classification as doubtful and adopt a more generic VAR designation for both stars (with V45 being a field object and V46 a probable cluster member).

6. Conclusions

This work presents a comprehensive census of variable stars in the young open cluster NGC 663, combining ground-based photometry from 50BiN, high-precision time-series measurements from TESS, and astrometric and astrophysical parameters from Gaia DR3. The main results are summarized as follows:

- We identified 60 variable-star candidates in total, of which 46 were confirmed as B-type variables based on their effective temperatures and spectral classifications. A cross-match with the VSX catalog shows that 31 of these objects had been previously reported as variables, while the remaining 29 do not have prior cataloged variability.

- Using Gaia astrometry, we determined membership probabilities for all sources and obtained a high-confidence sample of cluster members. Forty of the 46 B-type variables are likely associated with NGC 663.

- By combining light-curve morphology, spectral information, and frequency analyses, we classified the variables into several groups: seven candidate Cygni stars, three Cephei variables, ten slowly pulsating B candidates, one possible BCEP/SPB hybrid, twenty Be stars, and five additional objects showing eclipsing, rotational, ellipsoidal, or general variability.

These results establish NGC 663 as a rich laboratory for studying massive B-type variability across a broad evolutionary range—from main-sequence p- and g-mode pulsators to evolved supergiants exhibiting irregular variability. The unusually large Be-star population further highlights the cluster’s importance for probing the interplay between rapid rotation, pulsation, and binarity in massive stars. Future high-resolution spectroscopic observations and multi-wavelength follow-up will be essential for refining the physical interpretation of these systems. As a young cluster containing diverse classes of massive variables, NGC 663 offers a valuable foundation for advancing our understanding of massive star evolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, and investigation, X.X. and K.W.; data curation, X.X., K.W. and L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, K.W. and L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12373035, 12233009) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2023FY101104).

Data Availability Statement

The TESS light curves used in this study are publicly available from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), which can be found at https://mast.stsci.edu, accessed on 24 December 2025. The Gaia data products were obtained from the ESA Gaia Archive, which can be found at https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia, accessed on 24 December 2025. The 50BiN photometric data supporting this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This paper includes data collected by the TESS mission. Funding for the TESS mission is provided by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. This research has made use of the VizieR catalogue access tool, CDS, Strasbourg, France. This work has made use of data from the ESA mission Gaia, processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Variables of Non-B Spectral Types

In addition to the B-type variables discussed in the main text, we identified 14 objects showing other forms of variability (Table 3). Among these, T1–T4, T8, T9, and T11–T14 are previously cataloged variables in the VSX, while T5–T7 and T10 appear to be newly detected by the 50BiN observations. As these objects do not contribute directly to the analysis of massive B-type variability, they are presented here for completeness.

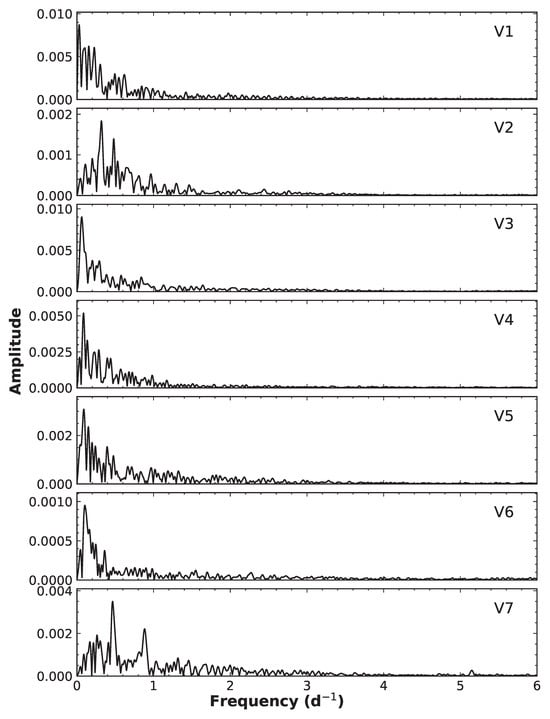

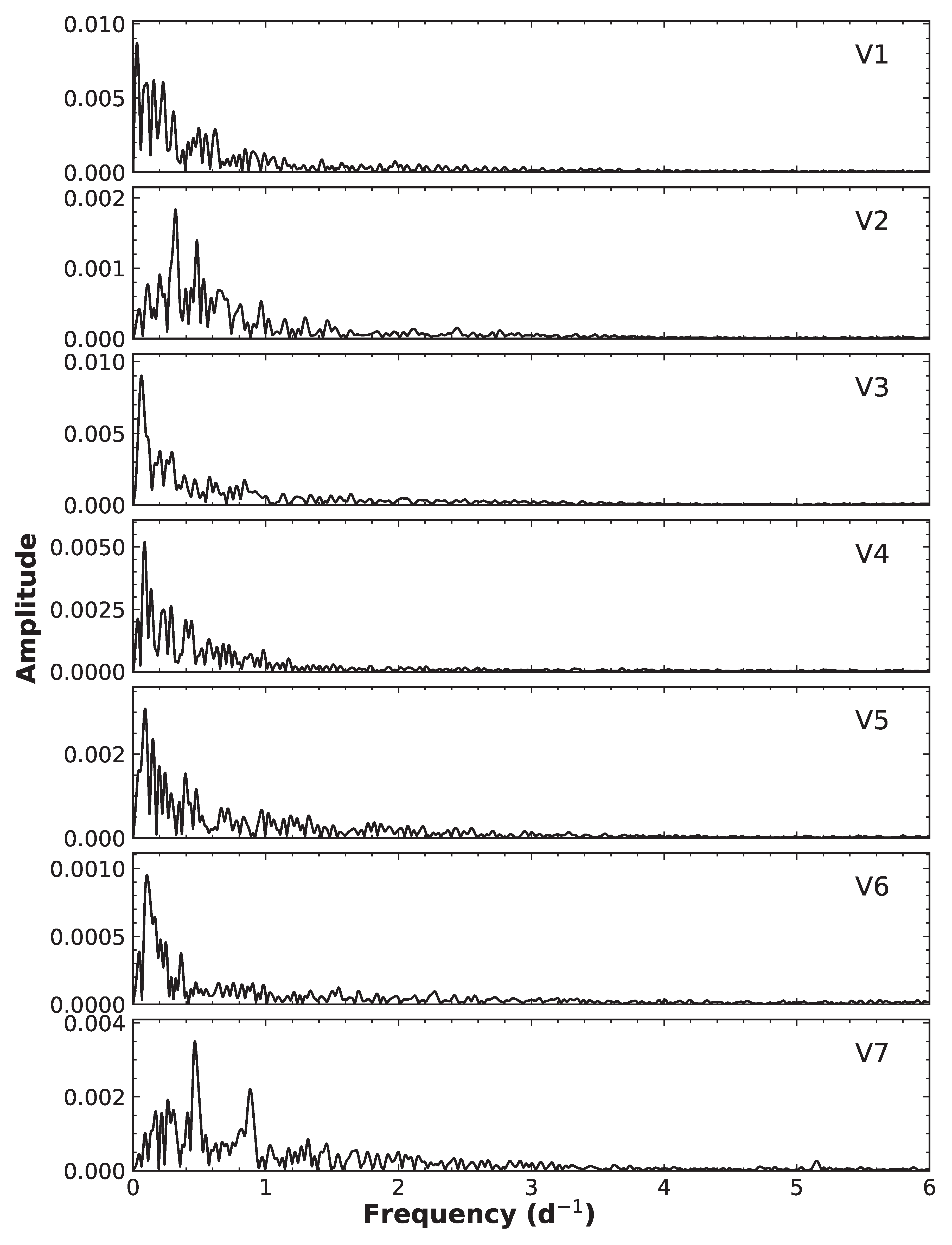

Appendix B. Amplitude Spectra of Selected B-Type Variable Stars

This appendix presents amplitude spectra of selected B-type variable stars to support the period analysis and variability classifications discussed in Section 5.

Figure A1.

Amplitude spectra of ACYG-type variable stars derived using the Period04 software.

Figure A1.

Amplitude spectra of ACYG-type variable stars derived using the Period04 software.

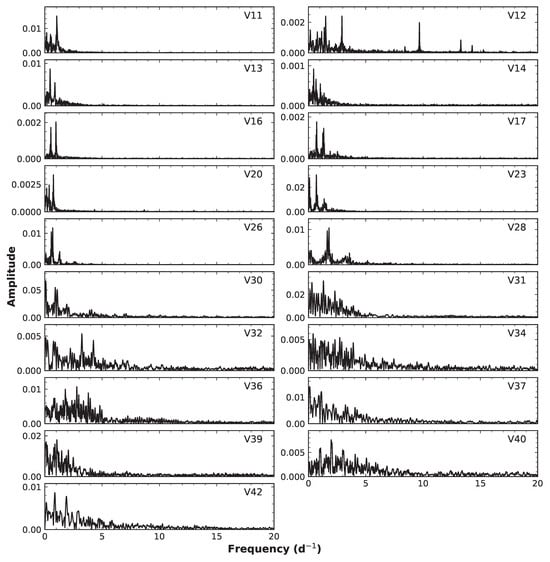

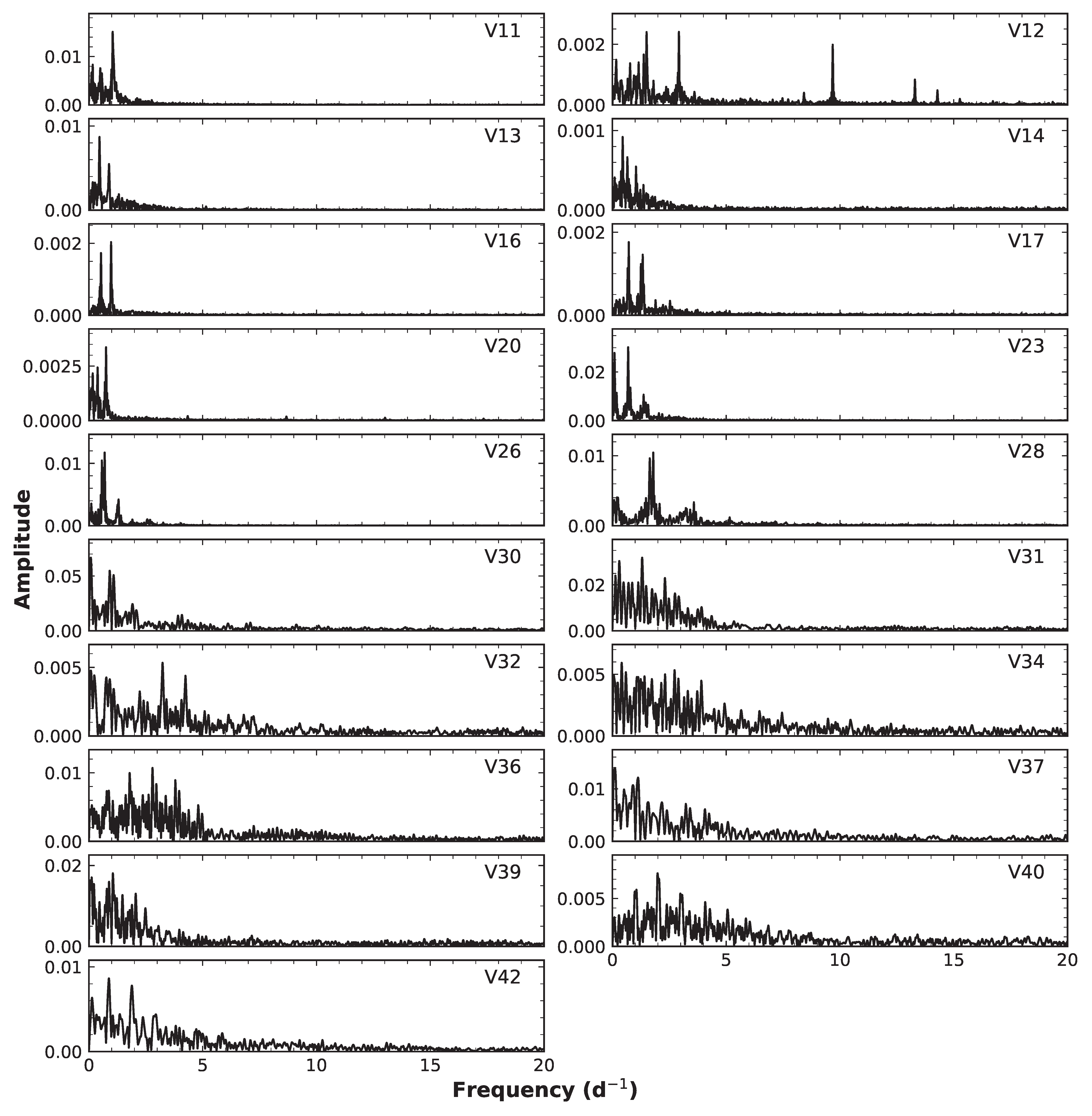

Figure A2.

Amplitude spectra of BE-type variable stars derived using Period04, excluding V29. For the 50BiN sample, the analysis is based on V-band photometry.

Figure A2.

Amplitude spectra of BE-type variable stars derived using Period04, excluding V29. For the 50BiN sample, the analysis is based on V-band photometry.

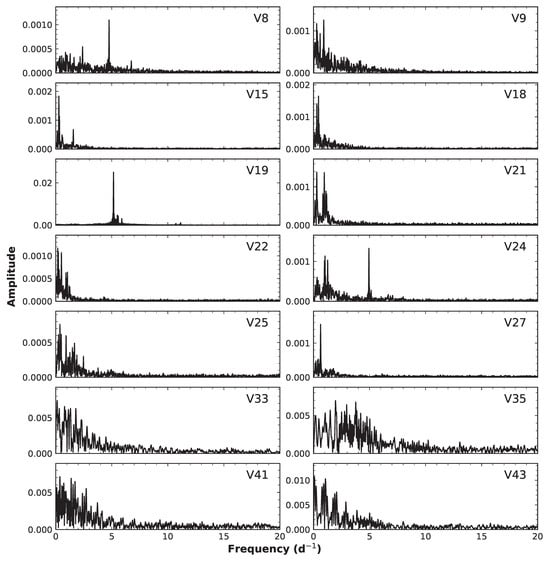

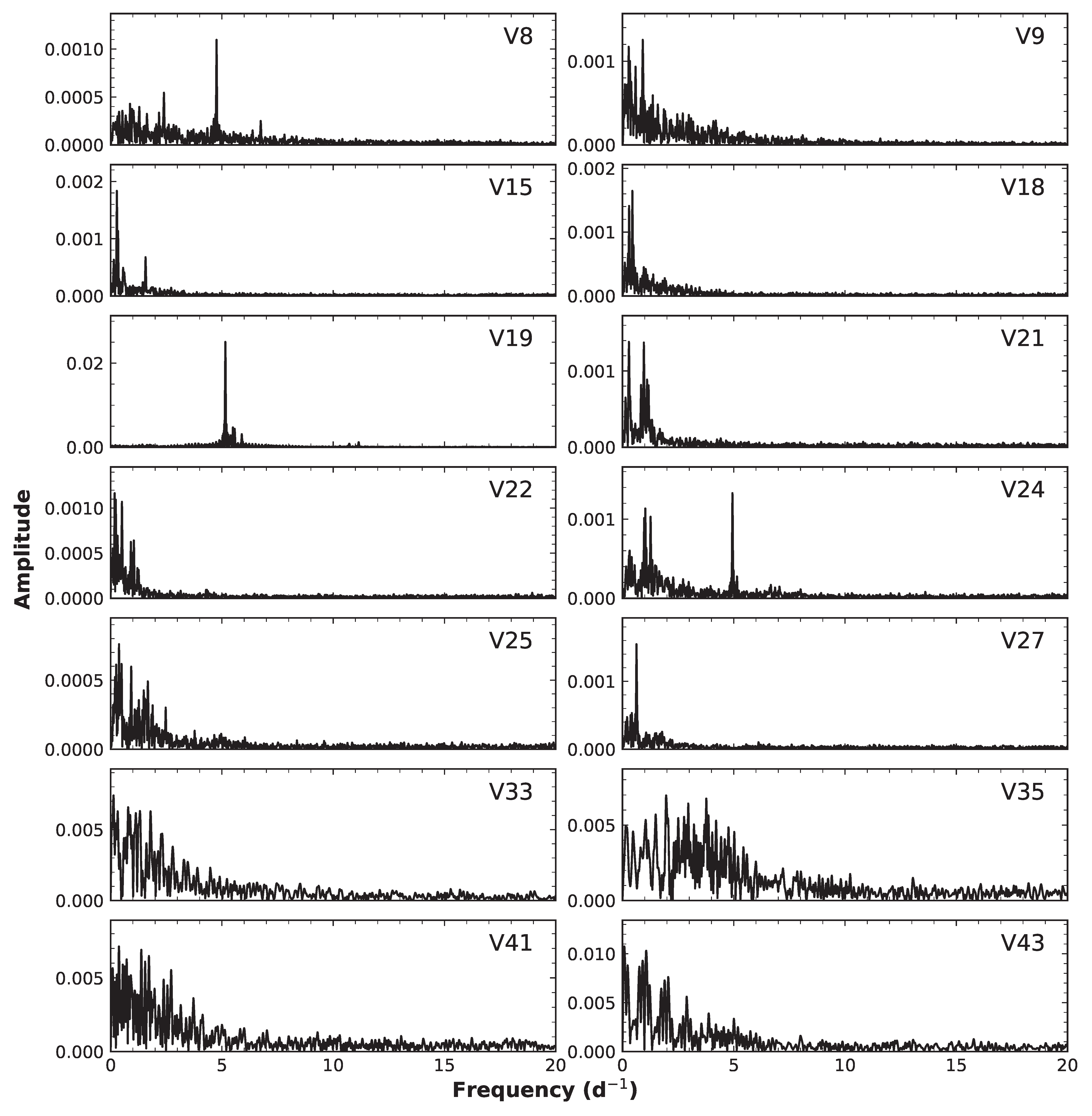

Figure A3.

Amplitude spectra of BCEP, SPB, and hybrid BCEP/SPB variable stars derived using Period04. The frequency analysis of the 50BiN sample is likewise based on V-band photometry.

Figure A3.

Amplitude spectra of BCEP, SPB, and hybrid BCEP/SPB variable stars derived using Period04. The frequency analysis of the 50BiN sample is likewise based on V-band photometry.

Notes

| 1 | https://vsx.aavso.org/, accessed on 24 December 2025 |

| 2 | http://stev.oapd.inaf.it/cmd, accessed on 24 December 2025 |

References

- Aerts, C. Probing the interior physics of stars through asteroseismology. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, D.W. Asteroseismology Across the Hertzsprung–Russell Diagram. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 60, 31–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebriakova, N.; Tkachenko, A.; Gebruers, S.; Bowman, D.M.; Van Reeth, T.; Mahy, L.; Burssens, S.; IJspeert, L.; Sana, H.; Aerts, C. The ESO UVES/FEROS Large Programs of TESS OB pulsators. I. Global stellar parameters from high-resolution spectroscopy. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 676, A85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, K. The disrupting and growing open cluster spiral arm patterns of the Milky Way. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 537, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; He, Z.; Deng, S.; Peng, L.; Li, C.; Luo, Y.; Wang, K. Census of Blue Straggler Stars in Distant Open Clusters and Maximum Fractional Mass Excess of Open Cluster Blue Straggler Stars. Astron. J. 2025, 169, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moździerski, D.; Pigulski, A.; Kołaczkowski, Z.; Michalska, G.; Kopacki, G.; Carrier, F.; Walczak, P.; Narwid, A.; Stęślicki, M.; Fu, J.N.; et al. Ensemble asteroseismology of pulsating B-type stars in NGC 6910. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 632, A95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.I.; Hunt, E.L. A bird’s eye view of stellar evolution through populations of variable stars in Galactic open clusters. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 700, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Aerts, C.; Bedding, T.R.; Fritzewski, D.J.; Murphy, S.J.; Van Reeth, T.; Montet, B.T.; Jian, M.; Mombarg, J.S.G.; Gossage, S.; et al. Asteroseismology of the young open cluster NGC 2516-I. Photometric and spectroscopic observations. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 686, A142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Hu, Q.; Liu, J.; Qin, M.; Lü, G. Searching for Variable Stars in the Open Cluster NGC 2355 and Its Surrounding Region. Astron. J. 2022, 164, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J.; Deng, L.C.; Wang, K.; Luo, C.Q.; Zhang, X.B.; Li, C.Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, X.D. Variable stars in the 50BiN open cluster survey. II. NGC 869. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Jose, J.; Carciofi, A.C. Exploring membership and variability in NGC 7419: An open cluster rich in supergiants and Be type stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 541, 1866–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanzia, D.M.; Lata, S.; Chen, W.P.; Mondal, S.; Okeng’o, G.; Buers, J.; Ghosh, S.; Dileep, A.; Jain, A.; Hojaev, A.S.; et al. Stellar Variability toward the Galactic Open Cluster NGC 7209. Astrophys. J. 2025, 985, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Nie, Q.H.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.D.; Zhang, C.G.; Deng, L.C.; Zhang, X.B.; Chen, T.L. Variable Stars in the 50BiN Open Cluster Survey. III. NGC 884. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 24, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, J.; Capilla, G. CCD uvbyβ photometry of the young open cluster NGC 663. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 358, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, G.; González, G. Estrellas Be-Ae en Casiopea y Perseo; Be and Ae Stars in Perseus and Cassiopea. Boletín Obs. Tonantzintla Tacubaya 1954, 1, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schild, R.; Romanishin, W. A study of Be stars in clusters. Astrophys. J. 1976, 204, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanduleak, N. The emission-line stars in NGC 663. Astron. J. 1979, 84, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanduleak, N. Further Observations of the Emission-Line Stars in the Open Cluster NGC 663. Astron. J. 1990, 100, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigulski, A.; Kopacki, G.; Kołaczkowski, Z. The young open cluster NGC 663 and its Be stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 376, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.C.; Lin, C.C.; Chen, W.P.; Lee, C.D.; Ip, W.H.; Ngeow, C.C.; Laher, R.; Surace, J.; Kulkarni, S.R. Searching for Be Stars in the Open Cluster NGC 663. Astron. J. 2015, 149, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, S.N.; Subramaniam, A.; Girish, V.; Postma, J.; Sankarasubramanian, K.; Sriram, S.; Stalin, C.S.; Mondal, C.; Sahu, S.; Joseph, P.; et al. In-orbit Calibrations of the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope. Astron. J. 2017, 154, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedhath, S.; Rani, S.; Subramaniam, A.; Pancino, E. AstroSat/UVIT Study of NGC 663: First detection of Be+sdOB systems in a young star cluster. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 699, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Negueruela, I.; Castro, N.; Simón-Díaz, S. NGC 663 as a laboratory for massive star evolution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 542, 703–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzynski, G. Variable Stars in the Young Open Cluster NGC 663. Acta Astron. 1996, 46, 357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzynski, G. A CCD Search for Variable Stars in Young Open Cluster NGC 663. Acta Astron. 1997, 47, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pigulski, A.; Kopacki, G.; Kolaczkowski, Z. A CCD Search for Variable Stars of Spectral Type B in the Northern Hemisphere Open Clusters. IV. NGC663. Acta Astron. 2001, 51, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Yan, Z.; Luo, Z. SONG China project—Participating in the global network. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 2012, 8, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Deng, L.; Zhang, X.; Xin, Y.; Yan, Z.; Tian, J.; Luo, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, C.; Peng, Y.; et al. Variable Stars in the 50BiN Open Cluster Survey. I. NGC 2301. Astron. J. 2015, 150, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaia Collaboration; Vallenari, A.; Brown, A.G.A.; Prusti, T.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Arenou, F.; Babusiaux, C.; Biermann, M.; Creevey, O.L.; Ducourant, C.; et al. Gaia Data Release 3—Summary of the content and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 674, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.A.; Li, J.J.; Hao, C.J.; Lin, Z.H.; Hou, L.G.; Liu, D.J.; Li, Y.J.; Bian, S.B. Evolution of the Local Spiral Structure Revealed by OB-type Stars in Gaia DR3. Astron. J. 2024, 168, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuskey, S.W.; Pesch, P.; Snyder, G.A. The space distribution and radial velocities of some early-type stars in the Perseus spiral arm. Astron. J. 1974, 79, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, T.; Kochanek, C.S.; Stanek, K.Z.; Shappee, B.J.; Holoien, T.W.S.; Thompson, T.A.; Prieto, J.L.; Dong, S.; Pawlak, M.; Shields, J.V.; et al. The ASAS-SN catalogue of variable stars I: The Serendipitous Survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2018, 477, 3145–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegren, L.; Bastian, U.; Biermann, M.; Bombrun, A.; de Torres, A.; Gerlach, E.; Geyer, R.; Hernández, J.; Hilger, T.; Hobbs, D.; et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3—Parallax bias versus magnitude, colour, and position. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 649, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, G.R.; Winn, J.N.; Vanderspek, R.; Latham, D.W.; Bakos, G.Á.; Bean, J.L.; Berta-Thompson, Z.K.; Brown, T.M.; Buchhave, L.; Butler, N.R.; et al. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. J. Astron. Telesc. Instruments Syst. 2015, 1, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatyan, A.; Anders, F.; Chiappini, C.; Queiroz, A.B.A.; Nepal, S.; dal Ponte, M.; Jordi, C.; Guiglion, G.; Valentini, M.; Torralba Elipe, G.; et al. Transferring spectroscopic stellar labels to 217 million Gaia DR3 XP stars with SHBoost. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 691, A98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laur, J.; Kolka, I.; Eenmäe, T.; Tuvikene, T.; Leedjärv, L. Variability survey of brightest stars in selected OB associations. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 598, A108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Garzón, J.; Domingo, A.; Mas-Hesse, J.M.; Giménez, A. The first INTEGRAL-OMC catalogue of optically variable sources. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 548, A79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Deng, L.; de Grijs, R.; Yang, M.; Tian, H. The Zwicky Transient Facility Catalog of Periodic Variable Stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2020, 249, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomb, N.R. Least-Squares Frequency Analysis of Unequally Spaced Data. Astrophys. Space Sci. 1976, 39, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scargle, J.D. Studies in astronomical time series analysis. II. Statistical aspects of spectral analysis of unevenly spaced data. Astrophys. J. 1982, 263, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, P.; Breger, M. Period04 User Guide. Commun. Asteroseismol. 2005, 146, 53–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, K.; Ren, A.; Peng, L.; Cui, Q.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Q. Survey for Distant Stellar Aggregates in the Galactic Disk: Detecting 2000 Star Clusters and Candidates, along with the Dwarf Galaxy IC 10. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2023, 267, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Rao, K.K.; Vaidya, K.; Bhattacharya, S. ML-MOC: Machine Learning (kNN and GMM) based Membership determination for Open Clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 502, 2582–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, D. Multiple Machine Learning as a Powerful Tool for Star Cluster Analysis. Astron. J. 2025, 170, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D. Finite Mixture Models; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.L.; Reffert, S. Improving the open cluster census—II. An all-sky cluster catalogue with Gaia DR3. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 673, A114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Upadhyay, K.; Ogura, K.; Sagar, R.; Mohan, V.; Mito, H.; Bhatt, H.C.; Bhatt, B.C. Stellar contents of two young open clusters: NGC 663 and 654. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 358, 1290–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.M.; Schlafly, E.; Zucker, C.; Speagle, J.S.; Finkbeiner, D. A 3D Dust Map Based on Gaia, Pan-STARRS 1, and 2MASS. Astrophys. J. 2019, 887, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, L.; VandenBerg, D.A. On the use of Gaia magnitudes and new tables of bolometric corrections. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2018, 479, L102–L107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, A.; Marigo, P.; Girardi, L.; Salasnich, B.; Dal Cero, C.; Rubele, S.; Nanni, A. PARSEC: Stellar tracks and isochrones with the PAdova and TRieste Stellar Evolution Code. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 427, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigo, P.; Girardi, L.; Bressan, A.; Rosenfield, P.; Aringer, B.; Chen, Y.; Dussin, M.; Nanni, A.; Pastorelli, G.; Rodrigues, T.S.; et al. A New Generation of Parsec-Colibri Stellar Isochrones Including the Tp-Agb Phase. Astrophys. J. 2017, 835, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, M.S.; Santos, J.F.C.J.; Maia, F.F.S.; Corradi, W.J.B. Investigating Galactic binary cluster candidates with Gaia EDR3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 510, 5695–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantat-Gaudin, T.; Anders, F.; Castro-Ginard, A.; Jordi, C.; Romero-Gómez, M.; Soubiran, C.; Casamiquela, L.; Tarricq, Y.; Moitinho, A.; Vallenari, A.; et al. Painting a portrait of the Galactic disc with its stellar clusters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 640, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, W.S.; Monteiro, H.; Moitinho, A.; Lépine, J.R.D.; Carraro, G.; Paunzen, E.; Alessi, B.; Villela, L. Updated parameters of 1743 open clusters based on Gaia DR2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 504, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglio, A.; Montalbán, J.; Dupret, M.A. Revised instability domains of SPB and β Cephei stars. Commun. Asteroseismol. 2007, 151, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, C.B.; Sanduleak, N. New position determinations, and other data, for 1280 known Hα-emission stars in the Milky Way. Publ. Warn. Swasey Obs. 1977, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kohoutek, L.; Wehmeyer, R. Catalogue of stars in the Northern Milky Way having H-alpha in emission. Astron. Abh. Hambg. Sternwarte 1997, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, B.; Subramaniam, A. Optical spectroscopy of Classical be stars in open clusters. Bull. Astron. Soc. India 2011, 39, 517–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, C.; Augustson, K.; Mathis, S.; Pedersen, M.G.; Mombarg, J.S.G.; Vanlaer, V.; Van Beeck, J.; Van Reeth, T. Rossby numbers and stiffness values inferred from gravity-mode asteroseismology of rotating F- and B-type dwarfs - Consequences for mixing, transport, magnetism, and convective penetration. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 656, A121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.J.; Malizia, A.; Bazzano, A.; Barlow, E.J.; Bassani, L.; Hill, A.B.; Bélanger, G.; Capitanio, F.; Clark, D.J.; Dean, A.J.; et al. The Third IBIS/ISGRI Soft Gamma-Ray Survey Catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2007, 170, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivonos, R.A.; Sazonov, S.Y.; Kuznetsova, E.A.; Lutovinov, A.A.; Mereminskiy, I.A.; Tsygankov, S.S. INTEGRAL/IBIS 17-yr hard X-ray all-sky survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 510, 4796–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shporer, A.; Fuller, J.; Isaacson, H.; Hambleton, K.; Thompson, S.E.; Prša, A.; Kurtz, D.W.; Howard, A.W.; O’Leary, R.M. Radial Velocity Monitoring of Kepler Heartbeat Stars. Astrophys. J. 2016, 829, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.