Day-Time Seeing Changes at the Huairou Solar Observing Station Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Identification of features in the vertical structure of optical turbulence above the station. Determination of the changes in image quality characteristics over the past decades;

- (2)

- Estimation of long-period changes in another important astroclimatic quantity, total cloud cover (TCC), which determines the amount of observing time at the station.

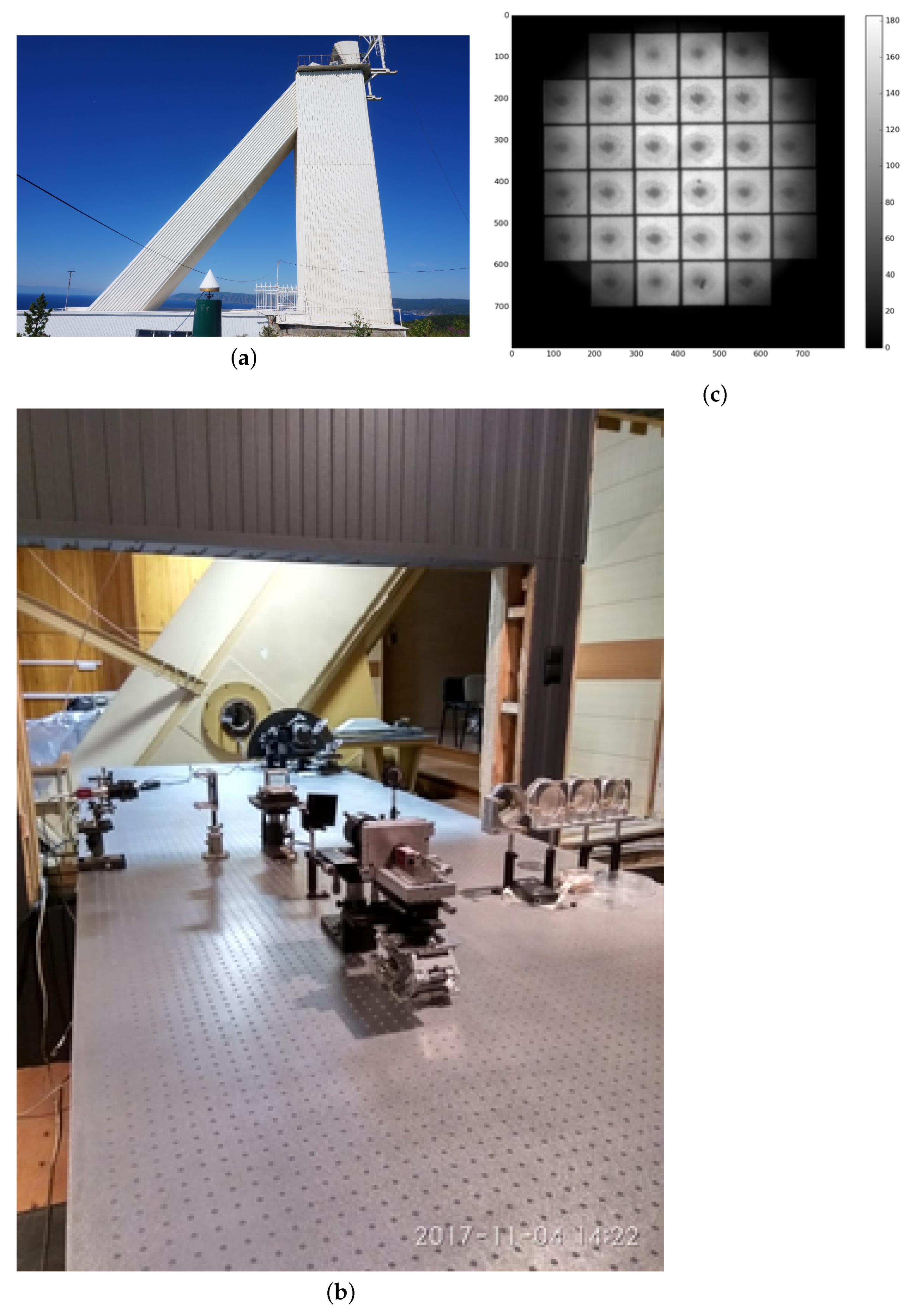

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Processing of solar photosphere hartmannograms recorded with frequencies from 80 to 300 Hz. In fact, using a large set of sub-images, differential displacements of their gravity centers are determined. The dispersion of differential displacements may be calculated using the following:where D is the telescope diameter (D = 600 mm). The coefficient K used in Formula (7) depends on the ratio of the distance between the centers of the subapertures and the subaperture diameter , as well as the direction of image motion and the type of wavefront slope. Longitudinal and transverse coefficients are as follows:

- (ii)

- The Fried parameter estimated by integration of the modeled along the height must be close to its measured value (from the differential motion of images). In othe ptical turbulence profile, the ground value of is set based on the processing of sonic measurements. The sonic measurements make it possible to refine the parameterization coefficients used in calculating the outer scale .

3. Astroclimatic Characteristics at the Site of Huairou Solar Observing Station

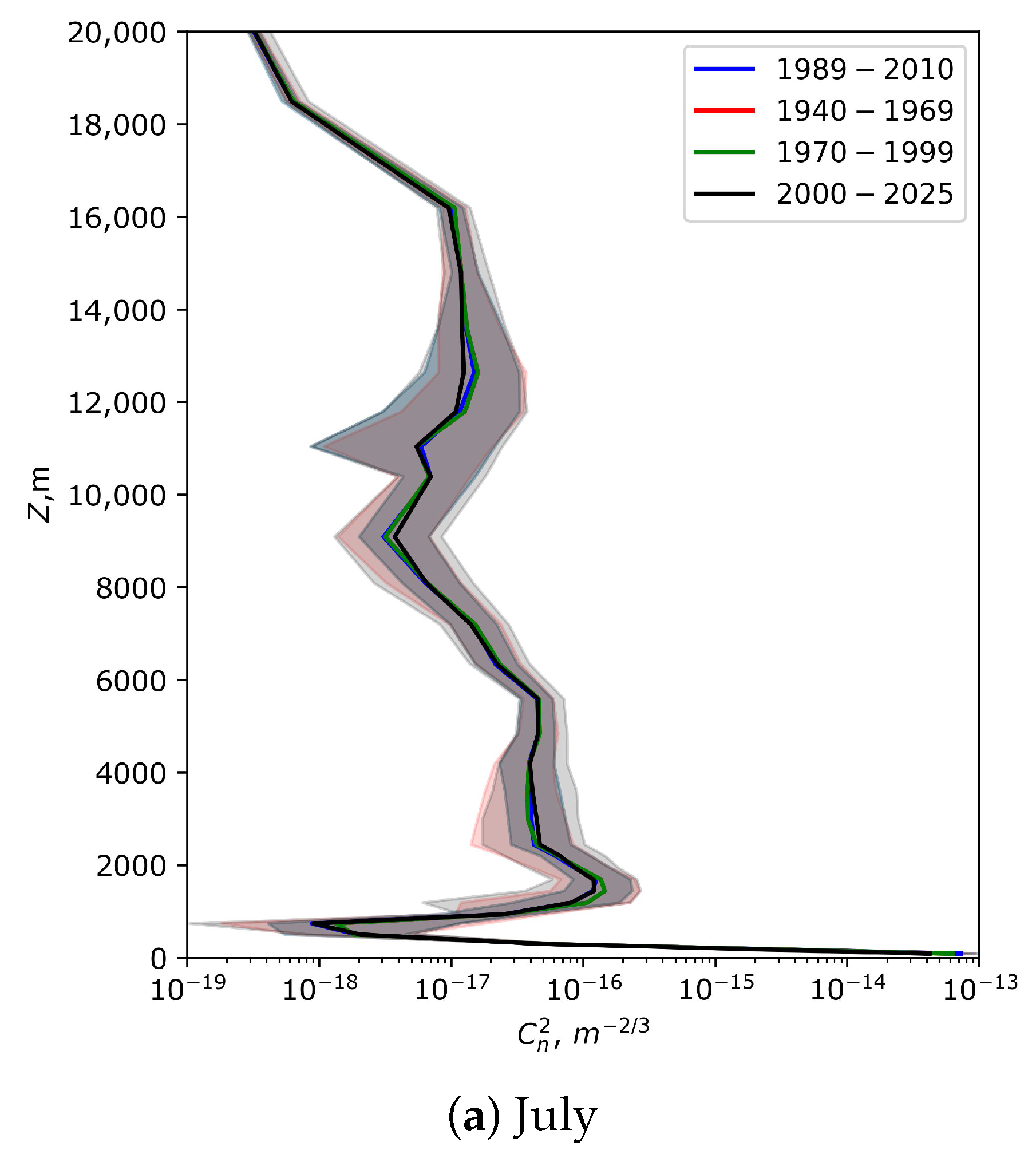

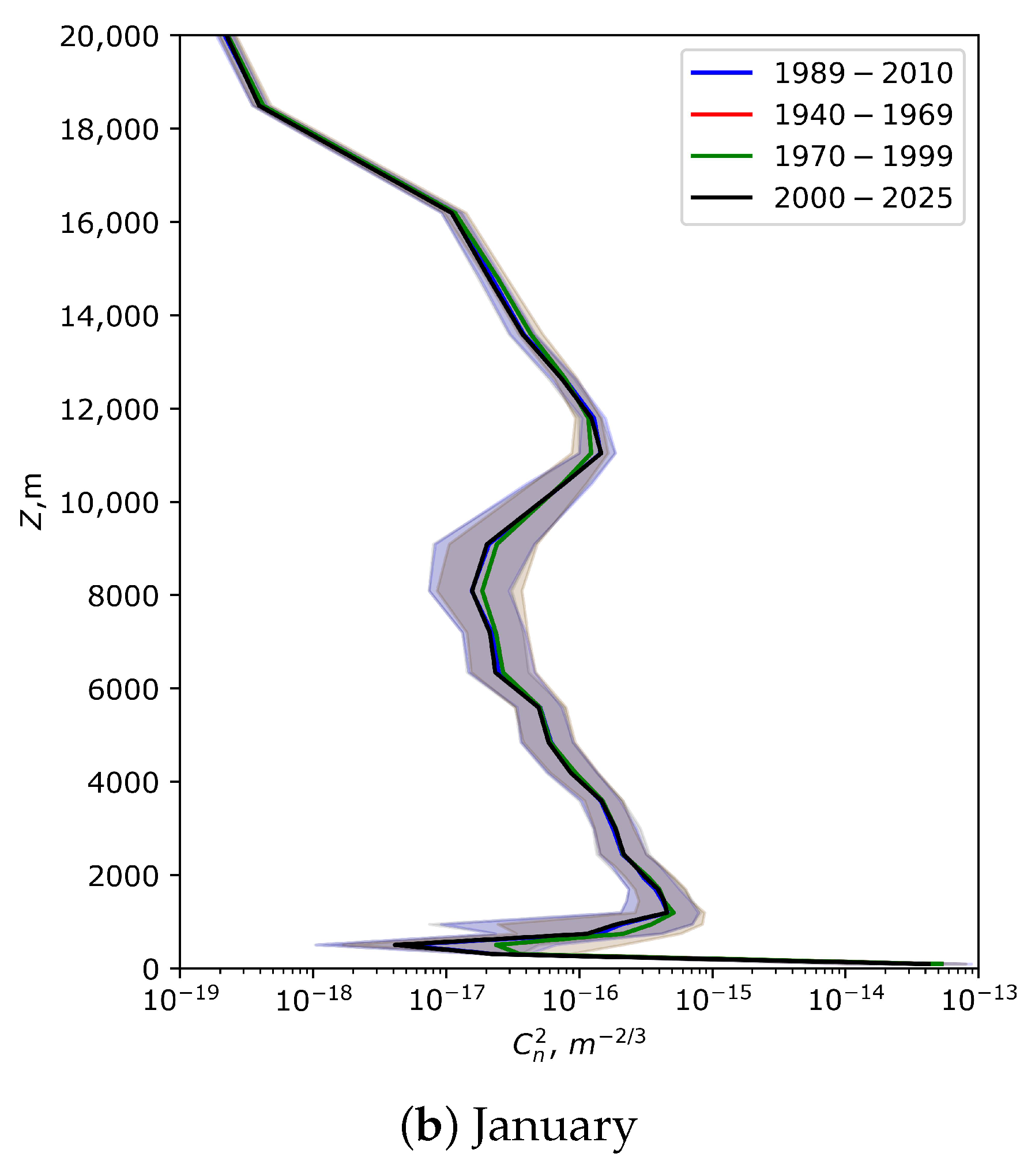

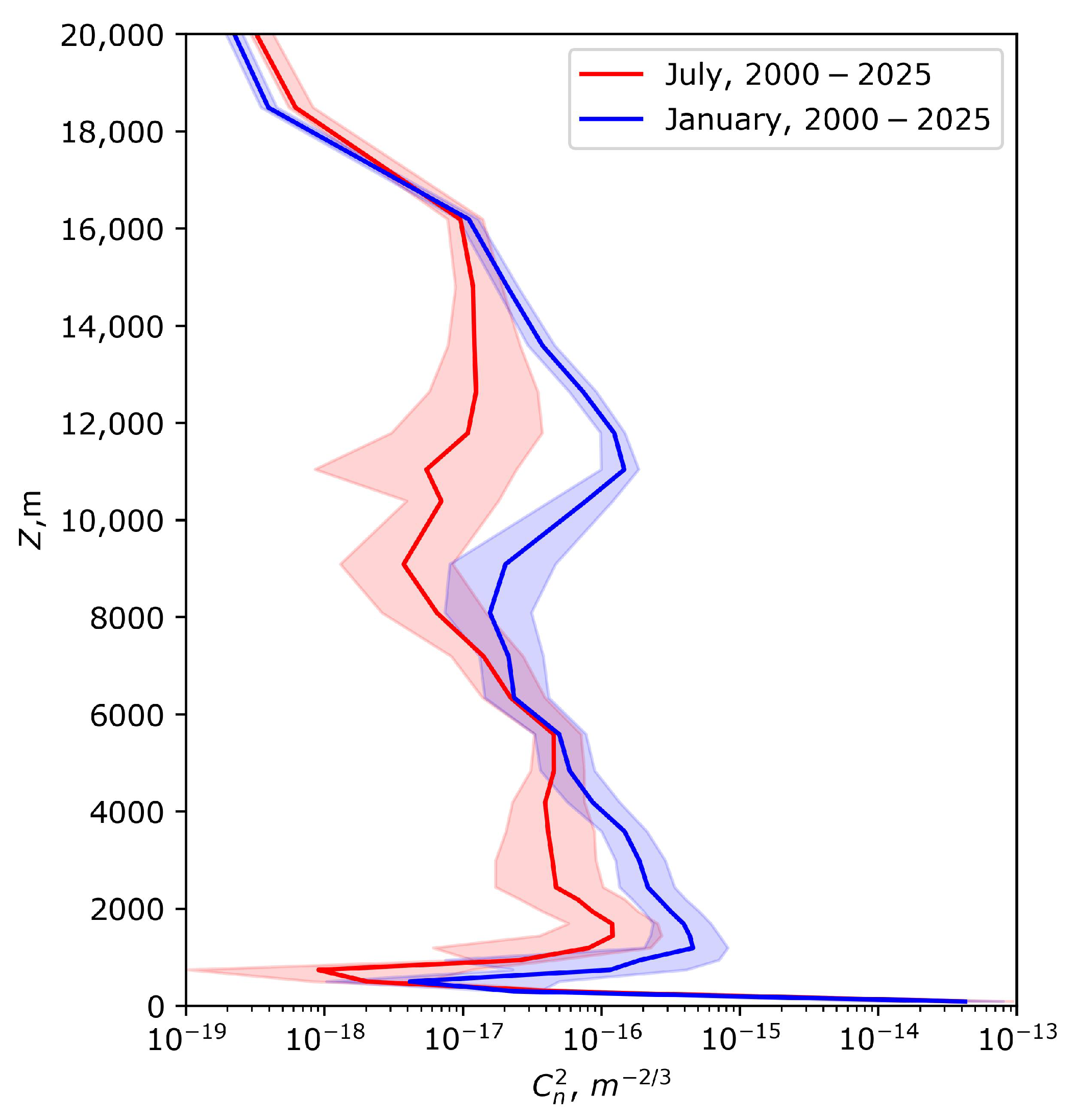

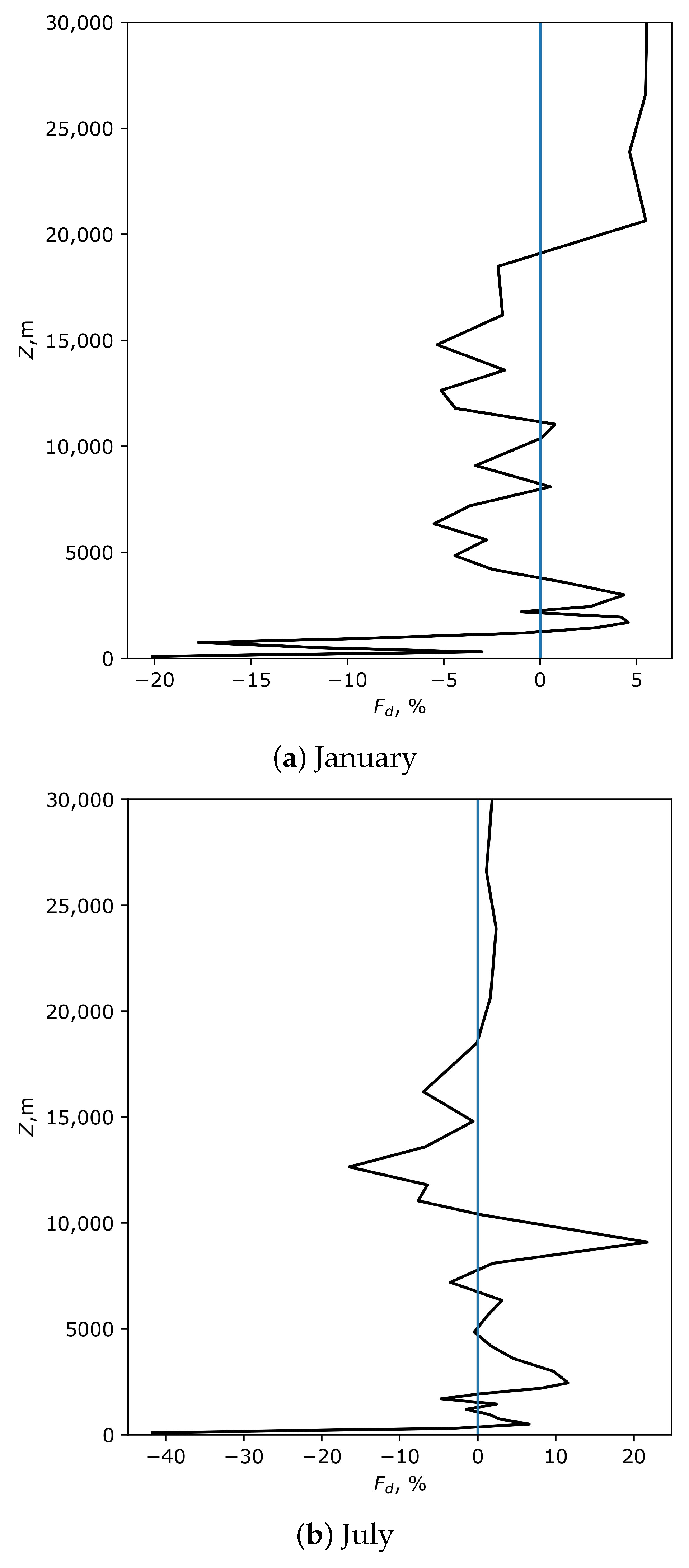

3.1. Vertical Distributions of Optical Turbulence at the Site of Huairou Solar Observing Station

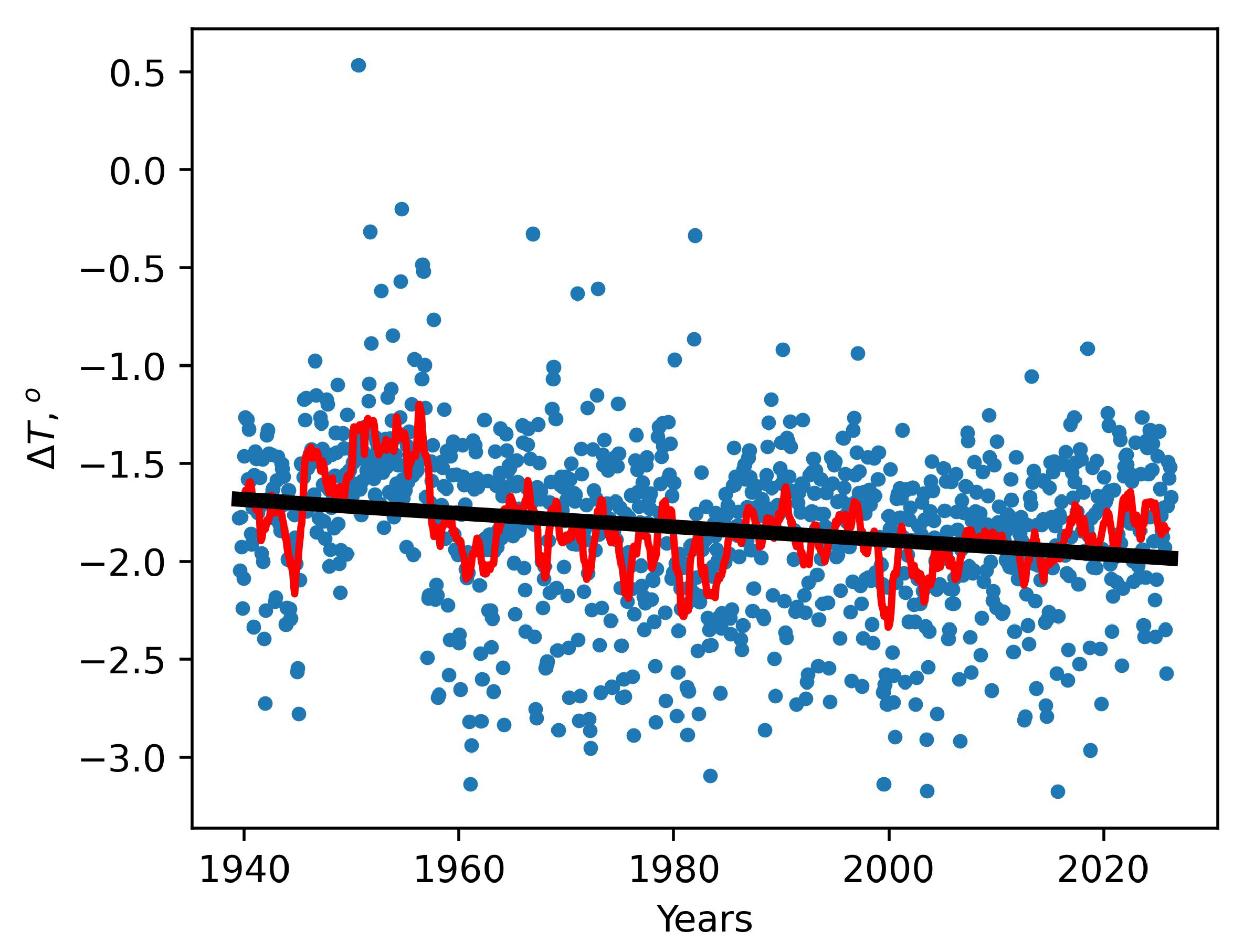

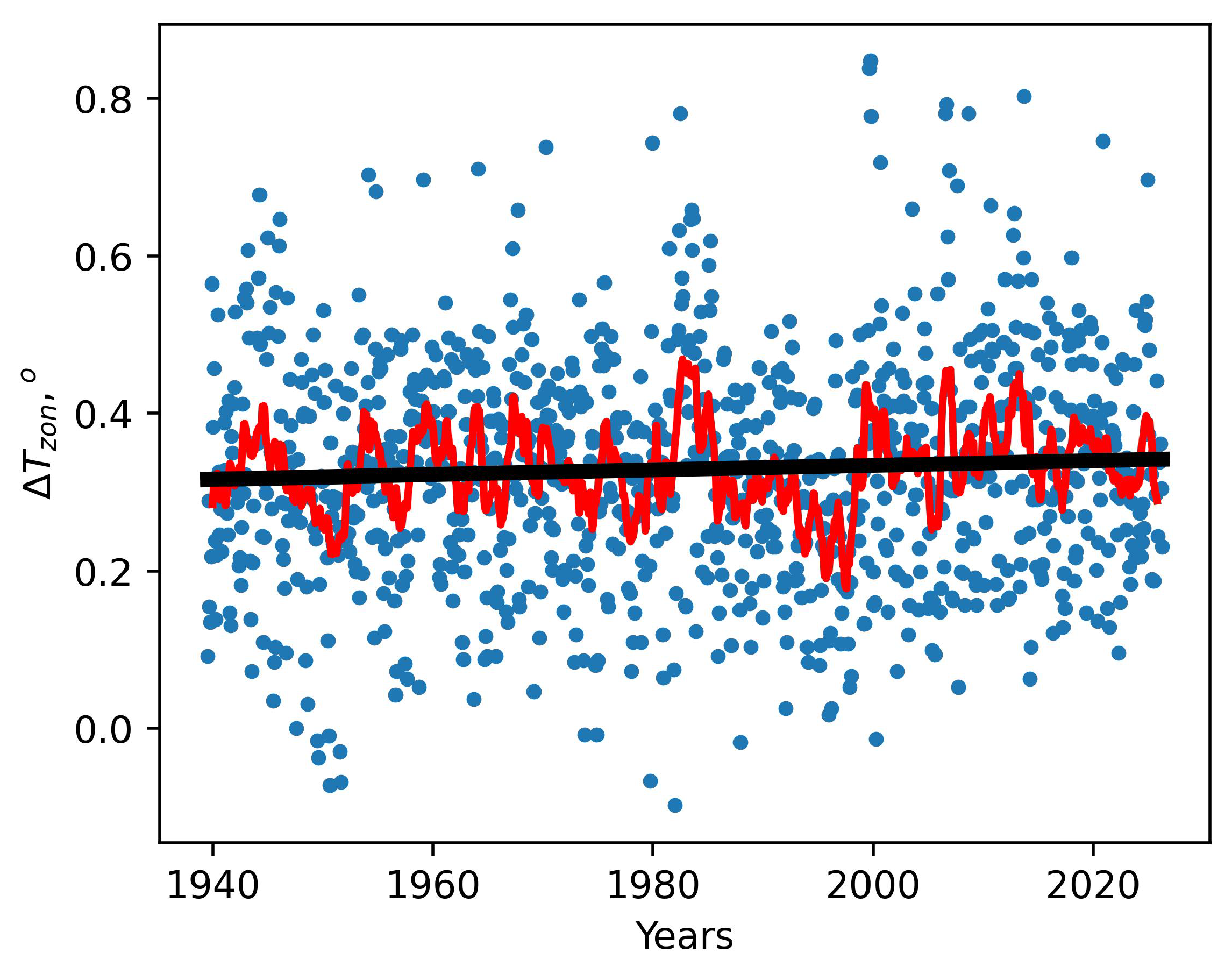

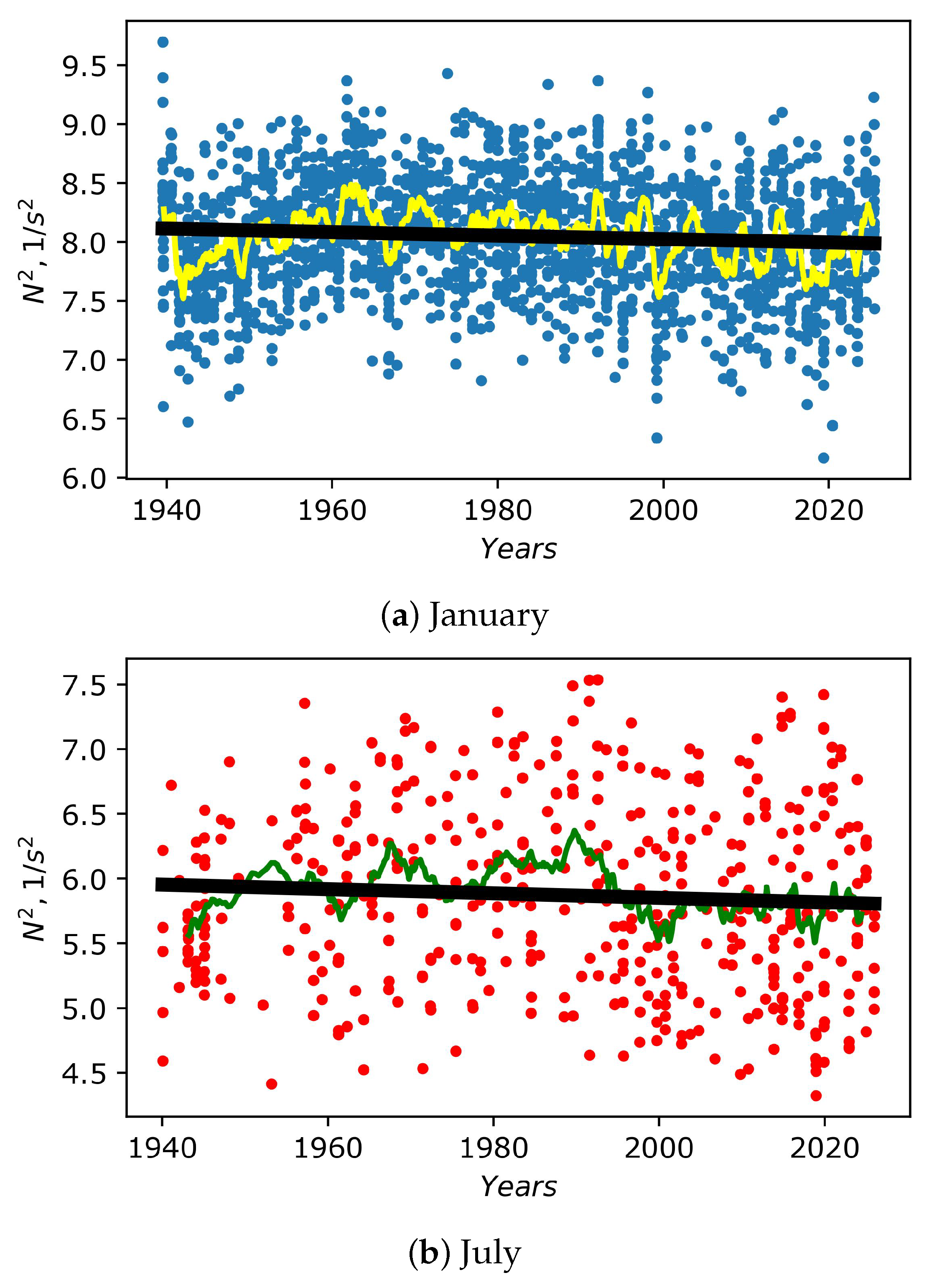

3.2. Long-Period Changes in Daytime Atmospheric Boundary Layer Heights at HSOS

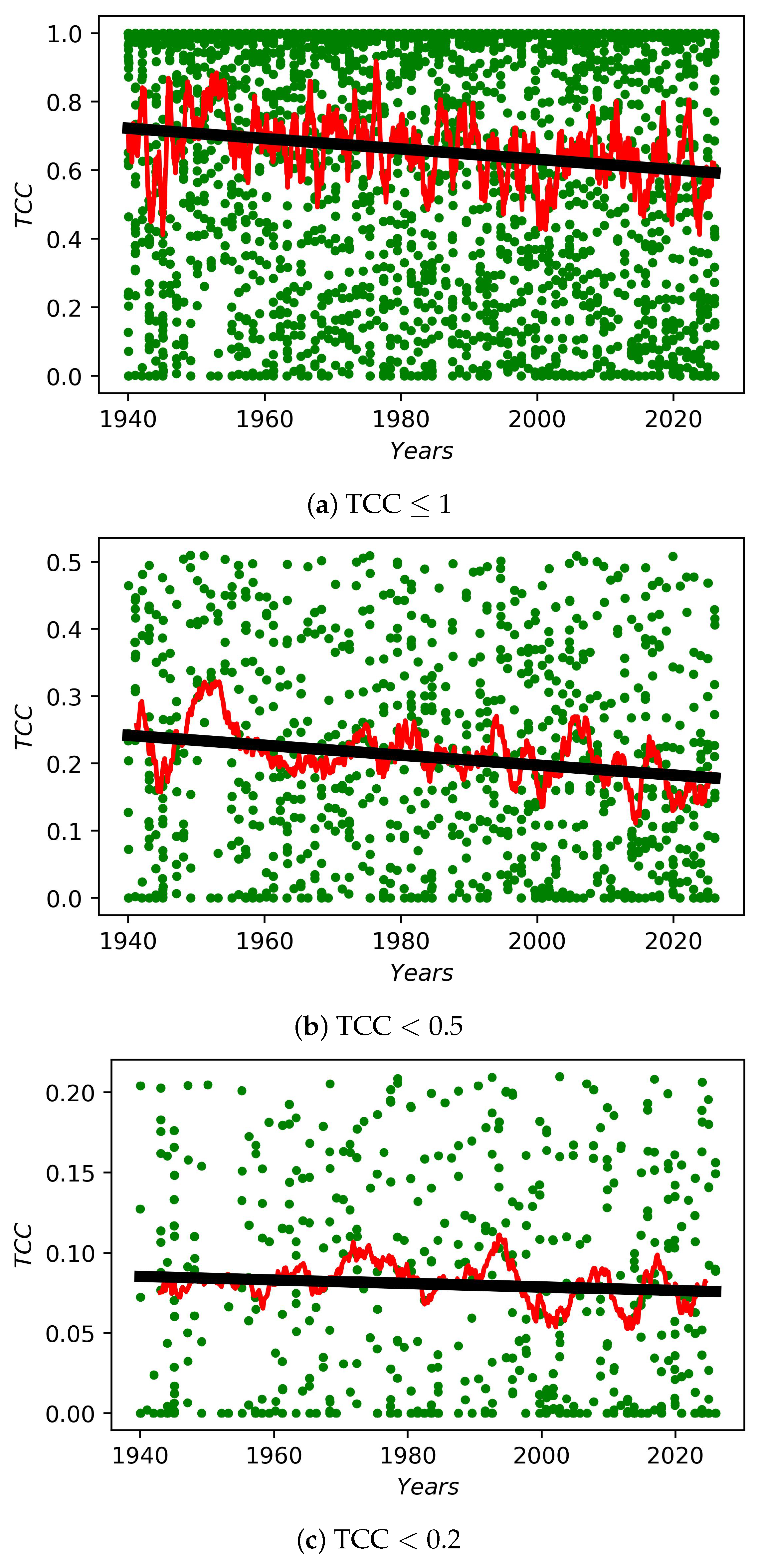

3.3. Long-Period Changes in Day-Time TCC at HSOS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haslebacher, C.; Demory, M.-E.; Demory, B.-O.; Sarazin, M.; Vidale, P.L. Impact of climate change on site characteristics of eight major astronomical observatories using high-resolution global climate projections until 2050. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 665, A149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalloube, F.; Milli, G.; Böhm, C.; Crewell, S.; Navarrete, J.; Rehfeld, K.; Sarazin, M.; Sommani, A. The impact of climate change on astronomical observations. Nat. Astron. 2020, 4, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.V.; Otarola, A.; Theron, V. On the Impact of ENSO Cycles and Climate Change on Telescope Sites in Northern Chile. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillayev, Y.; Azimov, A.; Ehgamberdiev, S.; Ilyasov, S. Astronomical Seeing and Meteorological Parameters at Maidanak Observatory. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolbasova, L.A.; Kopylov, E.A.; Mironov, A.P.; Kokhirova, G.I.; Zhukov, A.O. Variations in the Astroclimate of High-Altitude Observatories of Tajikistan. Astron. Rep. 2025, 69, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchuk, V.E.; Afanas’ev, V.L. Astroclimate of Northern Caucasus-myths and reality. Astrophys. Bull. 2011, 66, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, F.; Li, R.; Yang, F.; Deng, L. Variability in Meteorological Parameters at the Lenghu Site on the Tibetan Plateau. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulman, C.E. Fundamental and applied aspects of astronomical “seeing”. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1985, 23, 19–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, D.L. Optical Resolution Through a Randomly Inhomogeneous Medium for Very Long and Very Short Exposures. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1966, 56, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Luo, T.; Su, C.; Zhu, W. Mesoscale optical turbulence simulations above Tibetan Plateau: First attempt. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 4571–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Qing, C.; Qian, X.; Luo, T.; Zhu, W.; Weng, N. Investigation of the Global Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Astronomical Seeing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, A.Y.; Kovadlo, P.G.; Kiselev, A.V.; Eselevich, M.V.; Lukin, V.P. Application of Neural Networks to Estimation and Prediction of Seeing at the Large Solar Telescope Site. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2023, 135, 014503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Shi, L.; Huang, Y.; Fu, S. Multistep ahead atmospheric optical turbulence forecasting for free-space optical communication using empirical mode decomposition and LSTM-based sequence-to-sequence learning. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Basu, S. Using an artificial neural network approach to estimate surface-layer optical turbulence at Mauna Loa. Opt. Let. 2016, 41, 2334–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellen, C.; Oakley, M.; Nelson, C.; Burkhardt, J.; Brownell, C. Machine-learning informed macro-meteorological models for the near-maritime environment. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 2938–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Obolkin, V.A.; Khodzher, T.V.; Molozhnikova, Y.V. Variability of the Ground Concentration of Particulate Matter PM1–PM10 in the Air Basin of the Southern Baikal Region. Atmos. Ocean. Optics. 2023, 36, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovadlo, P.; Shikhovtsev, A.; Lukin, V.; Kochugova, E. Solar activity variations inducing effects of light scattering and refraction in the Earth’s atmosphere. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 2018, 179, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, S.; Song, T.; Bao, X.; Sun, W.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M. Estimation of Day-Time Seeing Changes at Huairou Solar Observing Station Based on Neural Networks from 1989 to 2010. Universe 2025, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, E.T.; Almeida, A.P.; Carlesso, F.; Pareja-Quispe, D.; Guarnieri, F.L.; Lago, A.D.; Gargaglioni, S.R.; Vieira, L.E.A. Assessment of Daytime Sky Quality and Atmospheric Refractive Index () Analysis at Pico dos Dias Observatory. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2025, 281, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.C.; Qing, C.; Qian, X.; Zhu, W.; Luo, T.; Li, X.; Cui, S.; Weng, N. Astroclimatic parameters characterization at lenghu site with ERA5 products. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 527, 4616–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, T.; Yang, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.; Shao, S.; Cui, S.; Li, X.; Weng, N. Estimation of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Turbulence Parameters over the South China Sea Based on Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, E.M.; Good, R.E.; Beland, R.; Brown, J. A Model for (Optical Turbulence) Profiles Using Radiosonde Data; Phillips Laboratory, Directorate of Geophysics, Air Force Materiel Command, Hanscom AFB: Bedford, MA, USA, 1993; Volume 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H.; Ueyama, R.; Atlas, R.; Dean-Day, J.; Bui, P.; Smith, J.B.; Podglajen, A.; Homeyer, C.R. Atmospheric Turbulence in the Upper Troposphere and Lower Stratosphere From Airborne Observations During the DCOTSS Field Campaign. JGR Atmos. 2025, 130, e2025JD044556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, A.Y. Reference optical turbulence characteristics at the Large Solar Vacuum Telescope site. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 76, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, D.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, S.Y.; Butterley, T. One-year Turbulence Profiling Campaign at Geochang Observatory Using a SLODAR. Curr. Opt. Photonics 2025, 9, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatresooz, F.; Oestges, C. Modeling for Free-Space Optical Communications: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21279–21305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, A.Y.; Potanin, S.A.; Kopylov, E.A.; Qian, X.; Bolbasova, L.A.; Panchuk, A.V.; Kovadlo, P.G. Simulating Vertical Profiles of Optical Turbulence at the Special Astrophysical Observatory Site. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.D.; Williams, P.D. Future Trends in Upper-Atmospheric Shear Instability from Climate Change. J. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 82, 2375–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yin, J.; Yalin, L. Statistics of cloud cover above the Ali Observatory, Tibet. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 529, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total aperture diameter | 760 mm |

| Entrance aperture size | 600 mm |

| Telescope focal length | 40 m |

| Light wavelength | 535 nm |

| Number of subapertures | 6 × 6, 8 × 8, 10 × 10 |

| Equivalent size of subaperture | 100 mm, 75 mm, 60 mm |

| Angular pixel size | 0.3″/pix |

| Frame frequency | 80–300 Hz |

| Typical exposure | 30 ms |

| , cm | , s | |

|---|---|---|

| ≤4 | 1.9 | 8.0 |

| >4 ≤ 6 | 1.80 | 5.40 |

| >6 ≤ 10 | 1.80 | 20.0 |

| >10 | 1.64 | 42.0 |

| Month | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value, cm | 3.0 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.9 |

| Median Value of | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cm | cm | cm | |

| Period | 1989–2010 | ||

| 2.50 | 5.13 | 1.84 | |

| Period | 1940–1969 | ||

| 2.48 | 5.21 | 1.90 | |

| Period | 1970–1999 | ||

| 2.49 | 5.33 | 1.75 | |

| Period | 2000–2025 | ||

| 2.78 | 5.40 | 1.80 |

| Median Value of | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cm | cm | cm | |

| Period | 1989–2010 | ||

| 2.39 | 5.59 | 1.85 | |

| Period | 1940–1969 | ||

| 2.42 | 5.40 | 1.89 | |

| Period | 1970–1999 | ||

| 2.50 | 5.46 | 1.97 | |

| Period | 2000–2025 | ||

| 3.13 | 5.62 | 2.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shikhovtsev, A.Y. Day-Time Seeing Changes at the Huairou Solar Observing Station Site. Universe 2026, 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010011

Shikhovtsev AY. Day-Time Seeing Changes at the Huairou Solar Observing Station Site. Universe. 2026; 12(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleShikhovtsev, Artem Y. 2026. "Day-Time Seeing Changes at the Huairou Solar Observing Station Site" Universe 12, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010011

APA StyleShikhovtsev, A. Y. (2026). Day-Time Seeing Changes at the Huairou Solar Observing Station Site. Universe, 12(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010011