Abstract

We present a numerical implementation of the proposed Source–Detector Resonance (SDR) as a conceptual analog of a Double-Slit Interference Experiment with discrete particles. Two periodic streams of particles are emitted from two point sources at random integer multiples of a fundamental period P and corresponding frequency and fly out towards a detection screen. The screen consists of a deep set of identical oscillators with eigenfrequency . In the SDR scenario, . When the particles reach the screen, they implement a periodic forcing of its oscillators at the stream’s fundamental frequency . As a result, an oscillating pattern develops along the screen. The amplitude of oscillation of each oscillator saturates at a value that is determined by the balance between the periodic particle forcing and the damping of each oscillator. This is clearly proportional to the number of particles that reach a certain oscillator per unit time times the fraction of particles that reach it at its resonant frequency. The latter fraction is equal to the ratio of the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the time series of the particles that reach the oscillator at its resonance frequency PSD() over the PSD at zero frequency PSD(0). If we further assume that each oscillator absorbs a particle and announces a detection with a probability that is proportional to the square of the ratio PSD()/PSD(0); the pattern of particle detections that develops over a thick layer of oscillators is shown to be the same as that of a Double-Slit Interference Experiment. Our result shows that when macroscopic resonant detectors interact with and detect periodic streams of discrete particles, they may create the illusion of an interference measurement, as if each discrete particle manifests a phase of its own.

1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics encompasses various interpretations, including Copenhagen, de Broglie–Bohm, von Neumann–Wigner, stochastic mechanics, and many theories from around the world [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Despite these interpretations, challenges remain with the ontological duality of elementary particles. When detected individually, these particles appear as distinct entities, but their collective detection reveals wave-like distributions, such as interference patterns (e.g., [13]). Some researchers have suggested that discrete particles carry phase information, which is gathered by specialized detectors [3,9,14,15]. These detectors exhibit wave-like characteristics after processing a significant number of particles. The authors of [14,16] concluded that interference phenomena may manifest themselves through the collective response of a macroscopic detector.

In the present work we revisit the question of whether it is possible to generate a wave interference pattern with an ensemble of classical discrete particles. As in [16], we decided to diverge from the model of [14] because we realized that classical discrete elementary particles do carry phase information. In fact, Feynman famously quoted that wave-like characteristics are ‘impossible, absolutely impossible to explain in any classical way’ (Feynman Lectures on Physics; [17]). We have already challenged this statement with our model of the Source–Detector Resonance (hereafter SDR, first described in [16]), according to which wave-like characteristics manifest themselves due to the collective response of a series of resonant oscillators to their periodic forcing by a periodic stream of discrete particles.

In the next sections, we perform a numerical double-slit experiment with two resonant streams of discrete particles that generate a particle-conserving interference pattern over a thick detector. This gives the illusion that discrete particles are carrying a phase of their own. We discuss vague analogies with quantum mechanics in the Appendix B. We emphasize that our model is presented just as a conceptual analog to wave interference that may initiate new thinking regarding these issues.

2. An Oscillator Driven by a Resonant Stream of Particles

Let us consider a classical oscillator with damping and an external periodic forcing. This is described by the equation

where y is the amplitude of oscillation, , where is the eigenperiod of the oscillator, is the damping ratio, is the frequency of the forcing, where P is the period of the periodic forcing, and f is the amplitude of the forcing, which is equal to the transfer of velocity per unit time by the driver. The above oscillator reaches an asymptotic oscillating state described by

where . When the forcing is at or close to resonance, the above expressions simplify to

where

is the asymptotic amplitude of the driven damped resonant oscillation.

Let us now consider a stream of elementary particles that reach the oscillator randomly at times equal to random integer multiples of the eigenperiod . This is equivalent to a stream of particle expressed as the time series

where is a random variable that is equal to 1 with a certain probability and 0 with probability . Let us also assume that, when the particles reach the oscillator, they change its velocity by . This means that, on average, the oscillator experiences a resonant transfer of velocity per unit time equal to

and the oscillator reaches an asymptotic amplitude of oscillation equal to

If one wants to integrate Equation (1) numerically, this may be expressed mathematically by rewriting it as the following set of equations:

where again are the random arrival times when particles reach the oscillator. We will next consider an oscillator that is driven by two independent periodic streams of particles.

3. An Oscillator Driven by Two Resonant Streams of Particles

Let us now place our classical oscillator at position and in a Cartesian system of coordinates . We will also consider two point sources of classical particles at positions and , with . The particles are emitted randomly either from the left or the right source at times equal to random integer multiples of the period P, with . Therefore, each point source emits a time series of particles equal to

where is equal to either 1 or 0 with random probability each.

For simplicity, we will also assume that particles travel with constant velocity v towards the screen with a Gaussian spread with dispersion around at . When particles reach the oscillator, they change its velocity by at random arrival times . We will assume that the particles interact with the oscillator if they approach within an interval centered around the position of the oscillator. According to the above scenario, the oscillator is driven by the following time series:

at each position and . What is important for driving the oscillator is the number of particles that reach it per period at the resonance frequency . On average, this number is equal to the total number of particles that reach it per period , multiplied by the ratio of the Probability Spectral Distribution (hereafter PSD) of at the resonance frequency over the PSD of at (the latter is proportional to the total number of particles that reach this particular position over the time t of the experiment). Putting everything together we obtain the resonant driving

With this forcing, the oscillator reaches an asymptotic amplitude of oscillation given by Equation (4), i.e.,

where the power spectrum of the time series is calculated at the position of the oscillator. It is straightforward to see that the pattern of is what would result from adding the two independent particles streams , namely

modulated by the ratio of the PSDs, as those are calculated from the total particle stream that reaches the position of the oscillator.

If the particles reach the oscillator in phase, i.e., with arrival time differences that are integer multiples of the period , the oscillator will be resonantly excited. If the particles reach the oscillator out of phase, i.e., with arrival time differences that are odd multiples of , the oscillator will be de-excited because the PSD of the particle stream will be zero at the resonance frequency (see [16]). When the oscillator is placed at the resonance positions where the differences between the two travel times are equal to integer multiples of the period , namely

the amplitudes of oscillation grow linearly with time until they reach their corresponding locally maximum asymptotic amplitudes given by Equation (4). When the oscillator is placed at the positions of destructive interference where the differences between the two travel times are equal to integer multiples of the period plus , namely

the amplitudes of oscillation remain close to zero. In summary, we assume that each resonant oscillator is able to figure out the ratio of particles that reach it at its resonant frequency over the total number of particles that reach it. This ratio is equal to PSD()/PSD(0) and is of fundamental importance in determining the saturated amplitude of oscillations. As we will see next, this ratio is also crucial in generating the interference detection pattern expected to form due to the two resonant streams of particles.

4. A Numerical Experiment with a Thick Layer of Resonant Oscillators

Instead of one damped driven resonant oscillator, we will now perform a numerical experiment in a thick (two-dimensional) screen of oscillators arranged in a square lattice of width beyond position . In our numerical code, we used the following parameters:

This array of oscillators will be excited by the same double stream of particles as before. In general, an oscillating pattern develops along the screen according to Equation (12), with local amplitude maxima along angular directions (Equation (14)) and zeroings along angular directions (Equation (15)).

What we are missing in order to reproduce the interference pattern of a double-slit experiment with elementary particles is the mechanism of detection of the particles by the oscillators. We will assume that an oscillator detects a particle with a probability

where, once again, PSD() is the PSD of the time series of particles that reach it from the two slits. We will assume that whenever a particle is detected by a particular oscillator, it will then be absorbed and will disappear from the particle series. If it is not absorbed, it will continue its path deeper inside the stack of oscillators until it is finally absorbed. The extra factor imposes a finite detection/absorption probability by the oscillator. As we will see below with our detection experiments, the value of must be sufficiently small in order to accurately reproduce the expected interference pattern. We do acknowledge of course that the probability formula that we used in Equation (17) lacks physical justification and is tuned to reproduce a pattern that is pre-determined from wave interference.

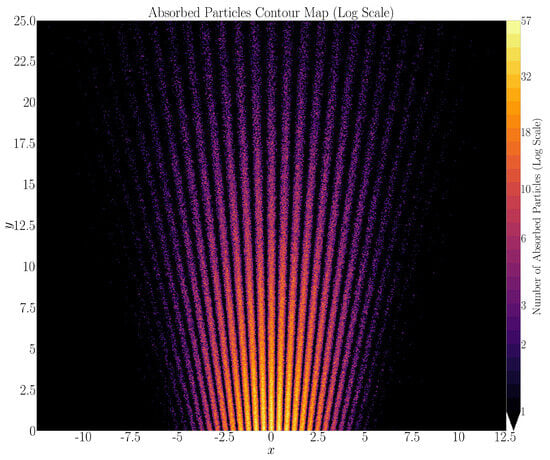

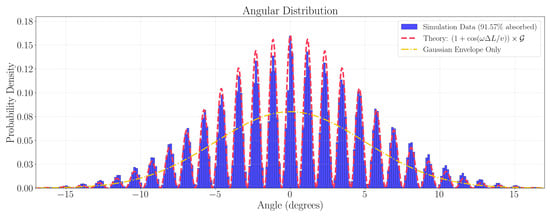

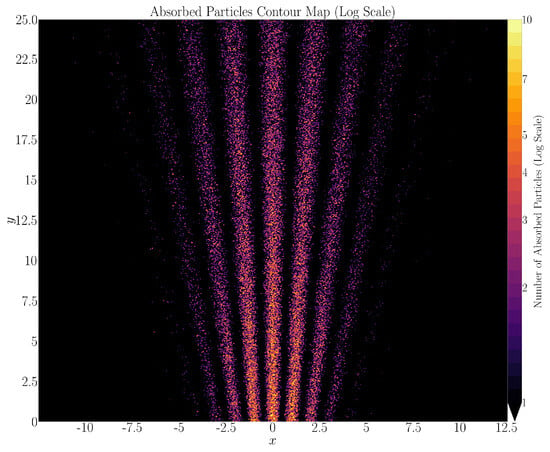

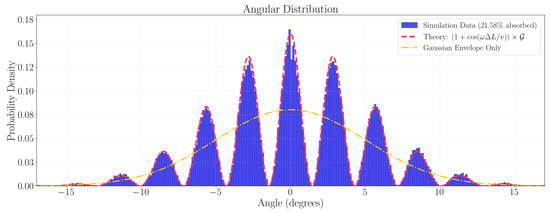

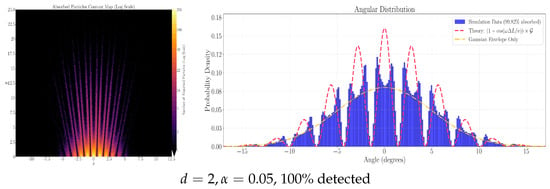

As shown in Figure 1, we perform the numerical experiment described above for and for an array of oscillators deep enough for almost all particles to be detected. Particles that pass through the first layer of resonant oscillators undetected reach the next layer of oscillators. If they again remain undetected, they reach a deeper layer of oscillators and so on and so forth until they are finally detected and removed from the experiment. The integrated distribution of particle detections across the detector thickness over angular directions centered on is shown in Figure 2 together with the angular distribution of particle injections (yellow line). The agreement with the wave interference result (red dashed line) is impressive. In particular, at the points of destructive interference, the two streams of undetected particles from the left and right slits will continue unimpeded deeper inside the detector. By doing so, both streams will move towards the two regions of constructive interference to the left and right of each region of deconstructive interference. When detected there, they will add up to a number of particles detected along the region of constructive interference that is greater than the number of particles that reach the first layer of the detector in that region. This is why the blue histogram in Figure 2 and the corresponding theoretical red dashed line lie above the Gaussian angular distribution of particles that reach the first layer of the detector (yellow line).

Figure 1.

Distribution of 400,000 particle detections after 400,000 periods P for a thick screen consisting of a orthogonal mesh of oscillators with a distance between them of in our units. The two random periodic sources of particles lie at and . in our units (Equation (16)). . In total, of the 400,000 particles that reached the screen are detected at various depths inside the detector.

Figure 2.

Distribution of particle detections integrated across the detector thickness over angular directions centered on . Yellow curve: the Gaussian angular distribution of detected particles. Particles that were not detected in the first layer were detected deeper inside the thick detector. Overall, of all particles are detected over the total thickness of the detector. Red dashed curve: the wave interference pattern distribution according to Equation (19) that corresponds to the detected particles.

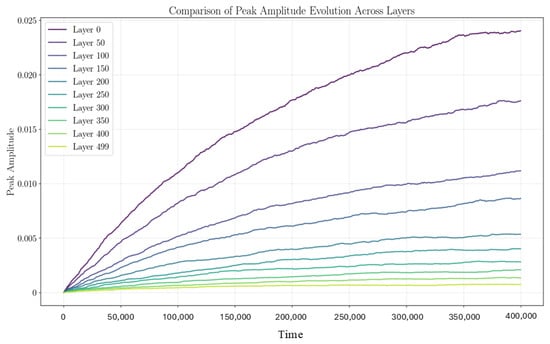

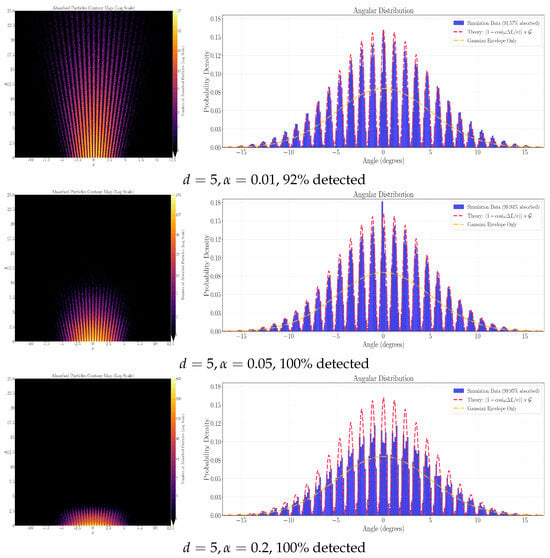

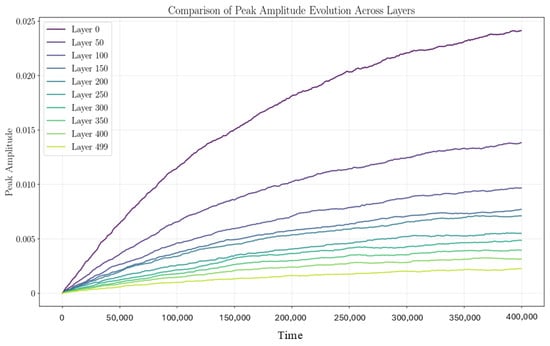

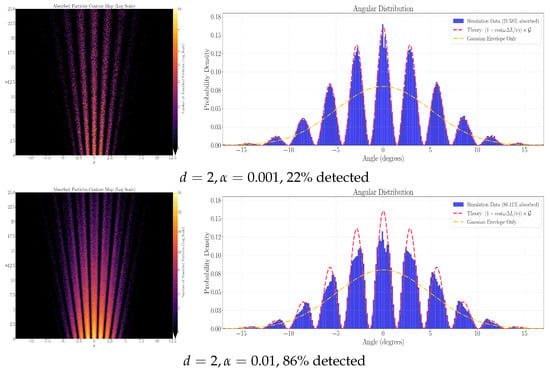

In Figure 3 we also show how the oscillation amplitudes saturate with time and depth inside the thick detector (shown only the maximum amplitudes per layer). Saturation is reached through the balance between the periodic forcing by the two particle streams and the damping of each oscillator (Equation (4)). The forcing gradually decreases as we move deeper inside the detector since the two particle streams are gradually depleted as particles are detected in the oscillator layers closer to the surface. In Figure 4 we repeat the same numerical experiment for various values of . We see that the larger the value of , the shallower and the more distorted the absorption interference pattern.

Figure 3.

Evolution with time of the maximum amplitude of oscillation per layer inside the detector. and . The deeper the layer, the fewer particles reach it per unit time and the smaller the asymptotic amplitude.

In [16] we showed that, in the case of a superposition of two intermittently periodic time series with average percentages of particles per period a and b, respectively, the probability of detection at position of the resonant detector as defined by Equation (17) is found numerically to be proportional to

since in our particular numerical experiment at all positions. Here, and are the distances of each slit from the point under consideration. It is important to understand that a finite probability of detection implies that not all particles will be detected in the first layer of the detector. Wave interference predicts the following probability distribution along the face (the first layer) of the detector at :

Here, is the difference in distance of a point of the first layer of the detector from each one of the two sources of particles at . In our numerical experiment we observe that this distribution (red dashed line in Figure 2) develops within a certain depth inside the detector, as was schematically shown in [16].

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the results of the same numerical experiment for . Once again, the positions of detection maxima and minima confirm Equations (14) and (15). Here, the best agreement with the wave interference pattern is obtained for values of . Notice that the smaller the value of the detection parameter , the deeper the final interference pattern and the better the agreement with the theoretical pattern predicted by wave interference. For larger values of closer to unity, strong detection spikes develop left and right of each detection minimum, and, although the positions of detection minima are reproduced correctly, the shape of the interference pattern diverges from the theoretical one (see Figure 4 and Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Same as Figure 1 for and .

Figure 7.

Same as Figure 3 for and .

Figure 8.

Same as Figure 4 for and (from top to bottom). Here, must be much smaller than about 0.01 for good agreement with the wave interference pattern.

5. Summary and Conclusions

In [16] we first introduced the concept of SDR (the Source–Detector Resonance) as a means to transmit some kind of `phase’ information to the detector. Such information cannot by carried by discrete elementary particles with no internal degrees of freedom, as originally proposed in [14]. However, such information can be carried collectively by a periodic stream of particles, as long as the detector becomes aware of the periodicity of the particle stream. This is possible if the detector resonates with the particle stream, or equivalently if the eigenperiod of each one of its constituents (oscillators) is close to the period P of the particle stream (). In that case, the detector identifies only the square of the fraction of particles that reach it at its resonant frequency at every position inside the detector. Obviously, this fraction is less than unity; thus a large fraction of the particles remain undetected after they reach the first layer of the detector. If the detector is deep enough, all the particles will be detected and a detection interference pattern will develop inside the detector. This is slightly different from what wave interference and quantum mechanics predicts, namely that the interference pattern will develop even if the detector is infinitely thin, and all particles are detected along its surface. According to our scenario, the exact wave interference pattern is recovered only if we are willing to integrate over the thickness of the detector the interference pattern that we obtained at all points in its interior. This prediction may be experimentally confirmed (or disproved) by constructing a detector with several layers along its thickness that will record detection events as a function of depth.

Finally, in order for the detector to calculate the fraction of the incoming stream of particles that reach it at its resonant frequency, it needs to collect a certain number of particles from which it will calculate the ratio PSD()/PSD(0). We propose to run a double-slit experiment for some time and then abruptly close one of the two slits. Obviously, the PSD of the stream of particles that the detector sees is calculated over some finite amount of time of running the experiment; thus, it contains a memory of past detection events, and therefore it will need some time to transition to the PSD of the new experimental setup. According to our proposed model, the detection pattern will require some finite amount of time to transition from an interference pattern to no interference. A finite transition time together with a deep interference pattern inside the detector would confirm our proposed model experimentally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.; Methodology, I.C.; Software, E.C.; Investigation, I.C.; Writing—original draft, I.C.; Visualization, E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with George Contopoulos and Constantinos Gontikakis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Numerics of the Particle Pusher

Instead of performing a numerical integration in time, we calculate the motion of the ith oscillator as follows:

- At , and .

- and will both stay zero until a particle reaches this particular oscillator.

- After a particle interacts for the first time with this oscillator at time , it will impart to it an extra velocity .

- Beyond time and before the next interaction at time

- In general,for i.e., between the and particle collisions.

- From the above we also deduce that the amplitude of oscillation immediately following a particle collision is equal to

In order to observe the resonance between the particle streams and the oscillators, we need very precise knowledge of the particle oscillations. These analytic expressions are more accurate and faster than a numerical integration. In practice, we generate the particle collision times for all oscillators i. We then calculate the positions and velocities right before each collision using Equation (A2). With these quantities calculated a priori, we are ready to calculate and at any time t.

Appendix B. Analogy with Quantum Mechanics

The SDR model consists of an ensemble of discrete (single) particle detections and manifests the illusion of a phase associated with each particle (hence the collective wave interference behavior of the macroscopic detector). Of course, quantum mechanics is formulated around the wave function of discrete particles without the need for resonant detectors with memory. Nevertheless, wave interference in quantum mechanics is experimentally manifested not by a single particle but by a large ensemble of particles. A potential interpretation of quantum mechanics with our model would indeed require resonant detectors with memory. Notice that our periodic particle streams are not necessarily completely filled. It is only required that discrete particles appear at random multiples of a fundamental resonant period P.

We stated above that the exact wave interference pattern that is obtained with discrete particles (e.g., [13]) is recovered only if we are willing to integrate over the thickness of the detector. This highlights a fundamental limitation of the model. In real wave interference experiments, the interference pattern appears directly on a two-dimensional detection surface, without any spatial averaging or integration through a detector volume. It is clear that our proposed Source–Detector Resonance consists of a statistical artifact of cumulative detection, not genuine wave interference with discrete particles. Nevertheless, we would like to briefly discuss below a possible analogy with quantum mechanics.

The periodicity of the particle stream may hold some fundamental information about how elementary particles are generated and accelerated in nature to some kinetic energy , as we first discussed in [14]. In order for our numerical interference experiment to correspond to the quantum mechanical experiment, the kinetic energy of the emitted particles must be directly related to the eigenperiod P of their source as

This is the only relation that connects our classical experiment to quantum mechanics. Why this is the case we do not yet understand. If the stream of particles is generated periodically in a source oscillator with mass , frequency , and damping ratio , then every period, the source oscillator loses energy , which must be equal to the kinetic energy of the emitted particle. Here, is the maximum velocity of oscillation of the source oscillator. Therefore,

This result agrees with the estimate of [14]. More investigation is necessary.

References

- Bacciagaluppi, G.; Valentini, A. Quantum Theory at the Crossroads: Reconsidering the 1927 Solvay Conference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, A.; Lochan, K.; Satin, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ulbricht, H. Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of ‘Hidden’ Variables, I and II. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, H., III. “Relative state” formulation of quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, N.; Spekkens, R.W. Einstein, incompleteness, and the epistemic view of quantum states. Found. Phys. 2010, 40, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.R. The Quantum Theory of Motion: An Account of the de Broglie-Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Maudlin, T. Foundations of Quantum Mechanics: An Exploration of the Physical Meaning of Quantum Theory. Am. J. Phys. 2018, 86, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzbacher, E. Quantum Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E. Derivation of the Schrödinger equation from Newtonian mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1966, 150, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. Quantum Fluctuations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E. Review of stochastic mechanics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 361, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styer, D.F.; Balkin, M.S.; Becker, K.M.; Burns, M.R.; Dudley, C.E.; Forth, S.T.; Gaumer, J.S.; Kramer, M.A.; Oertel, D.C.; Park, L.H.; et al. Nine formulations of quantum mechanics. Am. J. Phys. 2002, 70, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonomura, A.; Endo, J.; Matsuda, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Ezawa, H. Demonstration of single-electron buildup of an interference pattern. Am. J. Phys. 1989, 57, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contopoulos, I.; Tzemos, A.C.; Zanias, F.; Contopoulos, G. Interference with Non-Interacting Free Particles and a Special Type of Detector. Particles 2023, 6, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Yuan, S.; De Raedt, H.; Michielsen, K.; Miyashita, S. Corpuscular model of two-beam interference and double-slit experiments with single photons. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 074401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contopoulos, I. Wave-like Behavior in the Source-Detector Resonance. Particles 2025, 85, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1965; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).