Abstract

In adversarial reinforcement learning, designing dense reward functions is a traditional approach to address the sparsity of adversarial objectives. However, conventional reward design often relies on high-quality domain knowledge and may fail in practice, thereby inducing objective misalignment—a discrepancy between optimizing the designed reward and achieving the true adversarial utility. To reduce this discrepancy, a Value-Based Reward Shaping (VBRS) framework is proposed. VBRS integrates an intrinsic state-value estimate, which is a dynamic predictor of long-term utility, into the immediate reward function. As a result, exploration can be encouraged toward states predicted to be strategically advantageous, potentially avoiding some local optima in practice. Experiments demonstrate that VBRS outperforms a baseline that relies solely on the original reward function. The results confirm that the proposed method enhances adversarial performance and helps bridge the gap between designed reward guidance and the adversarial objective.

1. Introduction

Modern autonomous intelligent systems are required to make decisions in complex adversarial environments, with applications including robotics [1], autonomous driving [2], and multi-agent collaboration [3]. Adversarial decision-making represents a fundamental challenge in domains such as close-range unmanned aerial combat [4] and real-time strategy games [5]. A distinguishing characteristic of these domains is that agents must confront intelligent opponents within highly coupled interactions, while the opponent policy and the environment dynamics are unknown [6].

Traditional approaches often rely on rule-based controllers or tactical libraries designed by experts to approximate optimal behaviors [7]. Although effective in predictable scenarios, these static policies inherently fail to capture the complexity of unknown strategic objectives. Jiang et al. [8] attempted to learn opponent strategies through imitation learning and then applied dynamic programming. Nevertheless, data scarcity of trajectories in adversarial environments renders it impractical to reconstruct the environment and opponent policies [9].

Reinforcement Learning (RL) [10] provides a mechanism to optimize policies through direct interactions. Algorithms based on policy gradients [11], such as PPO [12], TRPO [13], and SAC [14], typically maximize a cumulative reward signal. In adversarial tasks, the true objective is defined by sparse goals, such as winning or losing [15,16]. Since optimizing solely on sparse signals is computationally inefficient, dense handcrafted rewards are frequently introduced to accelerate learning [17,18]. However, in adversarial settings, such task-specific rewards may deviate from the true adversarial utility and induce policy learning bias [19]. A fundamental discrepancy arises here: handcrafted reward functions are approximations that inevitably deviate from the true strategic objective [20,21].

Existing approaches, such as potential-based reward shaping (PBRS), enable reward shaping to improve the learning signal while preserving policy invariance under certain conditions. Classic extensions further relax the assumption of a fixed hand-crafted potential by allowing the potential function to change over time while maintaining PBRS-style guarantees, e.g., dynamic potential-based reward shaping [22]. Besides that, online learning of shaping rewards has been proposed to adapt shaping signals from experience, mitigating the need for expert-specified potentials [23]. Eureka leverages large language models to iteratively generate and refine executable rewards, but it still optimizes a proxy reward specification and offers no direct safeguard against misalignment with the true win/loss objective in adversarial settings [24]. Choi and Kim [25] demonstrate that incorporating a safety potential as a shaping signal can improve learning in autonomous driving. It has also been shown that PBRS can be reformulated as an equivalent initialization of action values, which has provided additional intuition on how state-dependent potentials influence learning dynamics without introducing net cyclic gains [26]. Recent bootstrapped reward shaping (BSRS) reduces reliance on expert-crafted potentials by using the agent’s current value estimate as the PBRS potential to densify sparse feedback [27], but it primarily targets exploration speed in sparse-reward settings and does not explicitly address objective misalignment in coupled adversarial interactions. Exploration-Guided Reward Shaping (EXPLORS) [28] integrates self-supervised intrinsic rewards with exploration bonuses to facilitate learning in environments with extremely sparse or noisy signals. Similarly, Automatic Intrinsic Reward Shaping (AIRS) addresses the biased-objective issue caused by auxiliary intrinsic rewards by adaptively selecting intrinsic shaping functions from a predefined set based on online return estimation [29]. More recently, the utilization of shaping rewards has been explicitly studied, where shaping signals have been adaptively leveraged while potentially unhelpful components are suppressed during training [30].

However, these approaches primarily target the scarcity of feedback by synthesizing auxiliary exploration signals or selecting from a pool of intrinsic modules. They do not explicitly address reward misalignment between artificial reward functions and the true strategic objective in adversarial settings. In such scenarios, the key challenge is not merely exploring the state space to obtain feedback, but correcting the optimization bias introduced by imperfect artificial priors that may actively mislead the agent away from the global optimum. Consequently, a critical unresolved issue remains: how can the discrepancy between handcrafted reward design and the true adversarial objective be reduced, such that optimizing rewards remains consistent with optimal adversarial goals?

To address this issue, a Value-Based Reward Shaping method (VBRS) is proposed. This method is designed to empirically mitigate the mismatch between optimizing a handcrafted reward and achieving the true adversarial objective in adversarial environments. The core mechanism integrates a value function, which serves as a dynamic estimate of long-term strategic utility, into the reward structure. By modulating the influence of handcrafted rewards based on value estimates, the gap between manually designed dense guidance and sparse adversarial outcomes is reduced. As training progresses and the value estimate improves, the bias introduced by imperfect reward engineering is partially rectified. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- A Value-Based Reward Shaping (VBRS) framework is proposed to mitigate reward misalignment. By incorporating value-function guidance into reward shaping, exploration is driven by long-term strategic value rather than biased short-term heuristics.

- A two-dimensional adversarial simulation environment is constructed. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared with other baselines, VBRS achieves superior adversarial performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 formalizes the adversarial decision-making problem. Section 3 analyzes the reward misalignment problem and describes the proposed value-based reward shaping method. Section 4 describes the experimental setup and discusses the results. Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Problem Formulation

To address the core question raised in Section 1—how can the discrepancy between artificial reward design and the true adversarial objective be reduced, such that optimizing a handcrafted reward becomes more consistent with adversarial goals in practice?—the adversarial engagement between an ego agent A and a fixed opponent B is formalized. Both agents act simultaneously in the environment, producing a joint trajectory:

At each time step t, both agents select actions and based on the current state . State transitions follow a joint dynamics model:

The opponent agent B follows a fixed policy:

2.1. Markov Decision Process

Since is fixed, the adversarial learning problem for agent A is modeled as a standard Markov Decision Process (MDP) [31]:

where

- is the state space, encompassing the status of both agents and relevant environmental information.

- is the action space of agent A.

- is the state transition probability induced by the environment dynamics and the opponent’s policy, calculated as

- is the immediate reward function for agent A.

- is the discount factor.

The behavior of agent A is defined by a policy , representing the probability of taking action in state s. Given a policy , the value function measures the expected cumulative discounted reward starting from state s:

where denotes expectation over trajectories induced by policy . The action-value function is

The optimal action-value function satisfies

where denotes the set of all policies. The optimal policy is

2.2. Policy Gradient Framework and Objective Analysis

Drawing upon theoretical results suggesting that reinforcement learning methods are fundamentally connected to policy gradient approaches [32,33,34], our algorithm is formulated in the policy gradient framework. The objective function is defined as the expected return:

is optimized via gradient ascent:

where is the advantage function. The goal is to find the optimal policy parameters .

In adversarial tasks, the true objective is typically a sparse outcome reward (e.g., win/loss), which is difficult to optimize directly. To address this, practitioners use a designed dense reward function r. Unfortunately, the reward function often suffers from misalignment.

The existence of an ideal adversarial reward function, denoted as , which perfectly captures the strategic structure of the task, is hypothesized. The corresponding ideal objective is

Let be the parameters of the ideal policy. For a generic handcrafted reward r, the resulting policy is typically suboptimal with respect to the ideal objective:

Since is unknown, the goal is to perform reward shaping on the existing reward r, such that the optimized policy approximates the performance of the ideal policy, while minimizing the required interaction samples and enabling rapid learning of effective counter-strategies.

3. Methodology

In this section, the Value-Based Reward Shaping (VBRS) framework is proposed. A value-based reward shaping mechanism aimed at overcoming the discrepancy between handcrafted reward design and the true adversarial objective is introduced, followed by an analysis of the properties of the shaped advantages. Then, an implementation using a dual-critic Actor–Critic framework integrated with Generalized Advantage Estimation and an adaptive -regularization schedule is presented. It is important to note that although we instantiate the actor update with PPO in this paper, PPO is not essential to VBRS. The main contribution of VBRS lies in the critic-side design—using intrinsic value estimates to construct a shaped reward/advantage signal that provides more informative learning guidance. Therefore, the actor component can be replaced by other compatible policy optimization schemes while retaining the same critic-driven shaping mechanism.

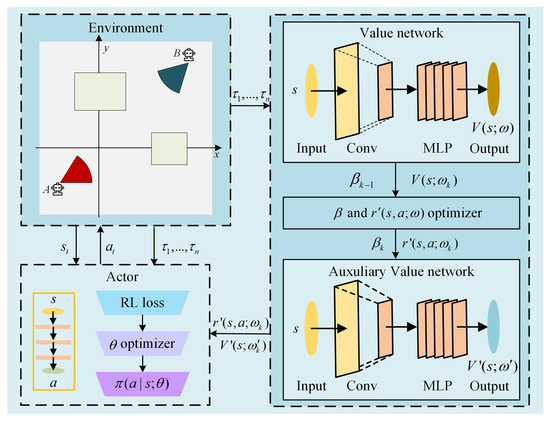

The overall architecture of the proposed VBRS framework is illustrated in Figure 1. As shown in the diagram, the framework comprises three integral components: the environment interaction module, the dual-critic evaluation mechanism consisting of the Main Value Network and the Auxiliary Value Network, and the actor policy update module. Notably, the actor update component is algorithm-agnostic and can be implemented using any value-based policy optimization method, such as traditional AC, Advantage Actor–Critic (A2C) [35], PPO, or SAC.

Figure 1.

The framework of the VBRS algorithm.

3.1. Value-Based Reward Shaping Objective

The agent is trained to maximize the expected discounted return under the designed environmental reward , as formulated in Section 2. In adversarial tasks, is often constructed by combining sparse outcome rewards with heuristic dense terms. As a result, local improvements in may not reliably correspond to progress toward the ideal adversarial objective.

To reduce this discrepancy, a shaped reward is defined by mixing the preset reward with a state-value signal that captures long-term task utility. For a fixed shaping coefficient , the shaped reward is defined as

where denotes the value function under policy with respect to the original reward scale. Since propagates delayed outcome information through Bellman recursion, the term serves as a dense signal that reflects the long-term desirability of visiting s.

The corresponding shaped objective is

Optimizing encourages both the immediate reward and the visitation of states with high long-horizon utility measured by . The strength of this encouragement is controlled by , which is required to balance the value term and the original reward. It should be noted that the shaping term has the same physical scale as a discounted return. When it is injected into every time step, the cumulative shaped objective contains an additional state-occupancy term , which generally re-weights trajectories and may be interpreted as intentionally emphasizing visits to states that are predicted to lead to long-horizon success. This design is not introduced as a policy-invariant reward transformation. Instead, the trade-off between the original reward and the value-based shaping signal is controlled explicitly by the balancing coefficient .

The shaping term changes the effective state-occupancy weighting, VBRS intentionally biases optimization toward states predicted to be strategically valuable. Accordingly, we evaluate alignment via outcome-level metrics (e.g., win rate) as evidence that proxy-induced optimization bias is reduced.

3.2. Dual-Critic Estimation and Adaptive Shaping Coefficient

The objective in Equation (10) is optimized by estimating the value terms with two critics. A Main Critic is used to estimate state values under the original reward. An Auxiliary Critic is used to estimate values under the shaped reward and to provide advantage estimates for actor optimization.

The Main Critic is trained on the original reward using the squared TD error

After the Main Critic has been updated, the shaped reward is instantiated by replacing in Equation (9) with the Main Critic output. To avoid unintended gradient coupling, the value term is treated as a detached scalar shaping signal:

where is held constant within iteration k for the trajectories collected in that iteration.

Consider a single trajectory with the terminal or truncation state . The Auxiliary Critic is trained under the shaped reward using a masked bootstrap target. Define the termination indicator , where if the episode terminates after step t, and for time-limit truncation so that bootstrapping is enabled.

Specifically, the bootstrap value is

and the Auxiliary Critic is optimized by minimizing the squared TD error:

Advantages for the actor are computed from the Auxiliary Critic using GAE. The shaped TD error is

and the shaped GAE advantage is computed as

where is the GAE parameter.

The shaping coefficient is introduced to control the magnitude of value-based shaping, since value estimates can be unreliable in early training. An adaptive schedule is constructed from the Main Critic loss. Let

denote the batch TD loss after the Main Critic update at iteration k. To reduce noise, an exponential moving average is maintained:

A confidence score is defined as

where is a fixed scale for normalization. The target shaping coefficient is set to

and the applied coefficient is updated smoothly and with a per-iteration change limit:

3.3. Actor Optimization with PPO

PPO is adopted to optimize the policy parameters . The coupling between PPO and VBRS is restricted to the advantage estimator: the PPO surrogate objective is evaluated using the shaped advantages computed under the shaped reward function. The actor optimizer can be replaced by other policy optimization schemes without modifying the critic-driven shaping mechanism, as long as the update is driven by advantage estimates.

Let denote the behavior policy and consider a single trajectory with variable length T. The shaped TD errors are computed from the Auxiliary Critic according to Equation (15), with the termination/time-limit bootstrapping rule described in Section 3.2. The shaped advantages are then obtained by GAE truncated at the end of the trajectory as in Equation (16).

Given , the PPO likelihood ratio is defined as

The clipped surrogate objective for the single trajectory is

this clipping limits the effective policy change: when , the update is capped if ; when , the update is capped if . and the entropy bonus is computed over the same trajectory:

The final PPO objective for is

and the policy parameters are updated by stochastic gradient ascent:

During the actor update, is treated as a constant with respect to , and no gradients are propagated into the critic networks through the advantage estimator.

For a batch of trajectories, the same construction is applied to each trajectory and the objectives are averaged over all collected time steps, which is equivalent to replacing the factor by . The complete process of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 PPO + VBRS:Proximal Policy Optimization with Value-Based Reward Shaping |

|

4. Experiment

4.1. Environment Setting

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, a two-dimensional adversarial simulation environment is constructed. All experiments are performed in a Cartesian plane defined over the region . Two static rectangular obstacles are placed inside the environment, whose axis-aligned bounding boxes are given by

Obstacles occlude the line-of-sight between the two agents and thus prevent successful aiming. When an agent collides with an obstacle, the velocity undergoes specular reflection with a damping effect. Specifically, let denote the mirror-reflected post-impact velocity. The actual post-collision velocity is defined as

where is a constant damping factor and we set .

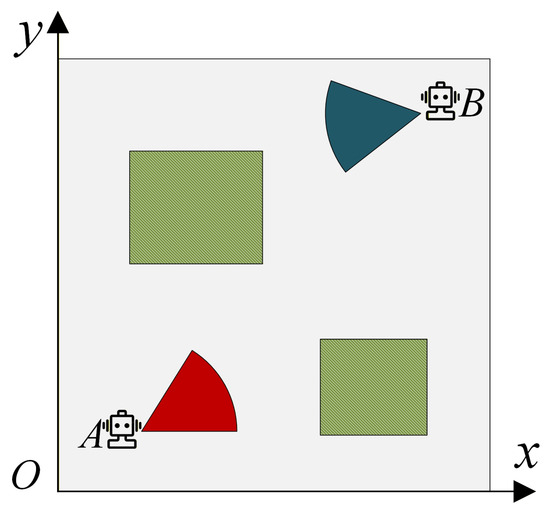

Agents A and B share the same kinematic constraints and weapon configurations. At the beginning of each episode, agent A is initialized uniformly at random within the region with zero initial velocity. Agent B is initialized within , also with zero initial velocity. A schematic illustration of the environment is provided in Figure 2. Each agent is equipped with a short-range weapon characterized by a maximum attack distance m and a maximum attack angle . From each agent’s own perspective, its attack angle is defined as the absolute angle between its heading direction and the line connecting itself to its target. Specifically, the ego agent’s attack angle is denoted by , and the opponent’s attack angle is denoted by . Each agent maintains an internal heading unit vector . At episode initialization, the agent has an initialized heading . When , the heading is aligned with the velocity direction. When , the heading is set to the last valid heading: . In particular, at , the heading equals the initialized heading . Attack angles and are computed using so that the angle is well-defined even when the velocity magnitude is zero.

Figure 2.

The adversarial environment where agent A competes against agent B.

An agent is considered to satisfy the firing condition if and only if (i) the target lies within the maximum attack angle, (ii) the line-of-sight distance does not exceed , and (iii) no obstacle blocks the ray between the two agents. Formally, the firing condition is unified as

where denotes the agent’s own attack angle (i.e., for agent A and for agent B), and indicates the presence of an obstacle between the two agents.

An episode terminates when either agent satisfies the firing condition or when the maximum episode length is reached. If both agents satisfy simultaneously or no firing event occurs before the time limit, the result is considered a draw. Otherwise, the agent satisfying first is regarded as the winner. In this paper, each episode corresponds to one trajectory .

Each agent obeys second-order point-mass dynamics with control input represented by a two-dimensional acceleration vector . The maximum allowable acceleration and velocity are constrained by and , respectively. Let the state at time t be and . The motion evolves in discrete time with step size using a semi-implicit Euler method:

We denote by the element-wise clipping operator that maps each component of to . In our implementation, the policy first samples an unconstrained raw acceleration action from the Gaussian policy, and we enforce the acceleration bound using element-wise clipping:

The environment transition uses the clipped action , while PPO log-probabilities are evaluated w.r.t. the raw sampled action (see Algorithm 1).

The complete environment state is defined as

where and are the positions of agent A and agent B, respectively. The environment encoding is a fixed vector that contains (i) obstacle positions and (ii) boundary information represented by the four corner points of the arena.

4.2. Reward Function Design

The reward function, denoted as r, consists of a terminal reward and a shaping reward [36]. This reward is implemented as the default environment reward across all methods, serving as the baseline reward for PPO, as well as the starting point for our proposed shaping mechanism. For a fair comparison, all methods employ PPO as the actor optimization algorithm. The terminal reward is defined as follows:

The heuristic shaping reward is designed to provide dense tactical feedback that encourages the ego agent to (i) reduce its own attack angle , (ii) increase the opponent’s attack angle , and (iii) maintain an appropriate engagement distance r. To obtain a bounded and numerically stable signal, a cosine-based angular term is adopted. Since in our setting and is monotonically decreasing on , a smaller angle corresponds to a larger cosine value. Accordingly, the angular shaping reward is defined as

which yields a higher reward when the ego agent achieves a smaller attack angle while forcing the opponent to a larger attack angle.

To regulate spatial engagement, we further modulate the same tactical preference by a distance-dependent window centered at the safety radius :

where specifies the preferred safety distance, and controls the width of the distance window.

The overall shaping reward is

where and are scalar coefficients that balance angular preference and distance regularization, respectively.

4.3. Opponent Policy Training

To obtain a competent opponent policy, an iterative training procedure is adopted for agent B. For both our agent A and the opponent B, the policy network and the value network are modeled as fully connected feedforward neural networks with one input layer, five hidden layers of 128 neurons each, and one output layer, using ReLU activation.

Importantly, both agents employ stochastic Gaussian policies. Specifically, the action is sampled from

where and are the state-dependent mean and standard deviation produced by the policy network. The log-standard-deviation is learned and bounded for numerical stability by clamping . At interaction time, we first sample an unconstrained raw action , and then enforce the acceleration bounds using element-wise clipping: . We store and its log-probability in the rollout buffer, while the environment transition uses the clipped action . Accordingly, the PPO likelihood ratio is computed w.r.t. the same raw action distribution, ensuring consistency between sampling and optimization.

To obtain a competent opponent, we refine agent B’s policy via an auxiliary training partner, agent C. Specifically, agent C is introduced to provide interactive training signals for agent B, enabling to become progressively more effective through self-play style refinement. Agent B interacts with agent C to refine its policy through three stages:

- Stage 1 Agent C remains stationary, allowing agent B to learn basic aiming.

- Stage 2 Agent C moves in straight lines with reflection, providing moving targets.

- Stage 3 (Self-Play): Agent C adopts a frozen copy of agent B’s current policy. This process is repeated for 15 iterations.

For all subsequent evaluations in Section 4.4, the opponent agent employs the final converged policy obtained at the end of Stage 3 and remains frozen throughout testing. To ensure reproducibility, we fix the environment random seed and the opponent-policy sampling seed for each evaluation run, and we report results aggregated over 10 independent training seeds.

4.4. Experimental Results

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed VBRS algorithm, we report two complementary metrics. (1) Win rate against the opponent. We use the win rate against the opponent policy (the best-performing fixed opponent defined in Section 4.3) as the primary metric to reflect the final adversarial effectiveness of the learned policy. (2) Estimated return under the preset handcrafted environment reward. In addition, we report an estimate of the original objective , the expected discounted cumulative return under the preset reward defined in Equations (34)–(37). This metric is reported to highlight that maximizing the handcrafted reward objective is not necessarily equivalent to maximizing adversarial performance, and a bias may exist between the two.

Every 50 episodes with the opponent, we freeze the current policy parameters and run a separate evaluation phase. The evaluation data are not used for learning updates; they are used only to compute the win rate and to estimate under the original reward. Each evaluation consists of episodes. An episode is counted as win/lose/draw according to the termination rule in Section 4, and the win rate is computed as

During the evaluation phase at iteration k, we estimate the original discounted return using Monte-Carlo rollouts collected under the frozen policy:

where is the set of evaluation trajectories and is the horizon of trajectory .

Four baselines are considered as follows:

(1) PPO with original reward. The first control group uses the preset environment reward and updates the actor using PPO.

(2) PBRS + PPO. The second control group applies potential-based reward shaping (PBRS) to the original reward and then performs PPO-based actor updates. Specifically, PBRS uses the standard shaping form

where we adopt a handcrafted state potential

Here, is the ego attack angle and is the inter-agent distance, are environment constants, and we set in our experiments.

(3) RND + PPO. The third control group augments the original reward with an intrinsic shaping signal based on Random Network Distillation (RND) [37] and updates the actor with PPO.

(4) VBRS with fixed . The fourth control group is an ablation of VBRS: while VBRS updates via an exponential moving average, this baseline fixes throughout training.

(5) VBRS. The experimental group employs the full VBRS algorithm and updates the actor using PPO.

For a fair comparison, all methods share the same network architecture, the same PPO-based update pipeline, and the same common hyperparameters (e.g., learning rates, number of updates, batch sizes, and evaluation settings), as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter settings.

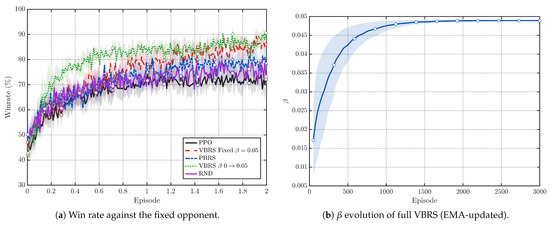

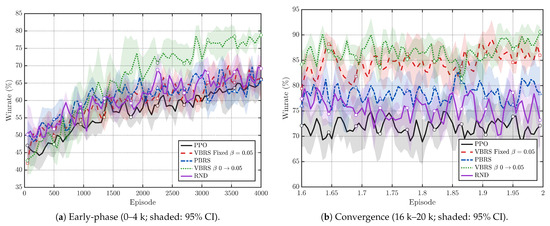

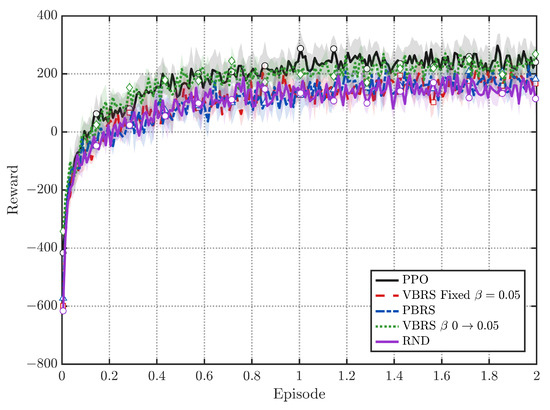

Figure 3a compares VBRS with four control baselines. Across training, VBRS consistently attains higher win rates, suggesting an empirical reduction of proxy-induced bias toward the adversarial outcome objective in our setting. In the early phase (0–4 k episodes), Figure 4a shows that VBRS achieves a faster win-rate improvement than other baselines (PPO, PBRS, and RND) during the early training phase. Figure 3b visualizes the EMA-updated in the VBRS, which gradually increases and stabilizes near the target range. Moreover, as gradually increases in Figure 3b, the performance gain becomes more pronounced, indicating that the value-based shaping signal provides effective guidance for learning and steers the policy toward strategically advantageous behaviors earlier.

Figure 3.

Overall comparison with all control groups and the evolution of the VBRS. In each plot, the curve shows the mean across seeds, and the shaded region denotes the 95% confidence interval (t-interval).

Figure 4.

Zoomed-in win-rate curves for early training and final convergence. Lines are means across seeds; shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals (t-interval).

In the final convergence window (16 k–20 k), Figure 4b shows that VBRS stabilizes at a markedly higher win rate than other baselines. Table 2 summarizes the final win rates by averaging the last 10 evaluation points per seed and then reporting mean ± 95% CI across seeds. The PPO Without VBRS achieves (95% CI: ), while the PPO with VBRS with a dynamic schedule achieves (95% CI: ), i.e., an absolute gain of in win rate. Among the shaping baselines, PBRS improves over PPO to (95% CI: ), whereas RND yields (95% CI: ), both remaining below VBRS. The fixed- ablation (VBRS with fixed) performs worse than the dynamic- variant, supporting the necessity of adapting during training.

Table 2.

Final win rate over the last 10 evaluation points. For each seed, we first average the last 10 recorded win-rate values, then report the mean across seeds with a 95% confidence interval (t-interval) and the standard deviation (SD) across seeds.

We conduct hypothesis tests on the final win rates against the PPO baseline using seed-paired runs (). For each method, we first average the last 10 evaluation points within each seed, and then apply a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test on the paired seed-level results. As summarized in Table 3, VBRS with a dynamic schedule yields a statistically significant improvement over PPO () with a large effect size (Cohen’s ). PBRS also shows a significant gain (), while RND and VBRS with are not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Overall, the tests corroborate that the performance advantage of VBRS (especially with ) is robust across random seeds.

Table 3.

Statistical tests on the final win rate against the PPO baseline. Final win rate is computed by averaging the last 10 evaluation points for each seed. Since runs are seed-paired (), we use a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Effect size is reported as Cohen’s on paired differences. Stars: ** .

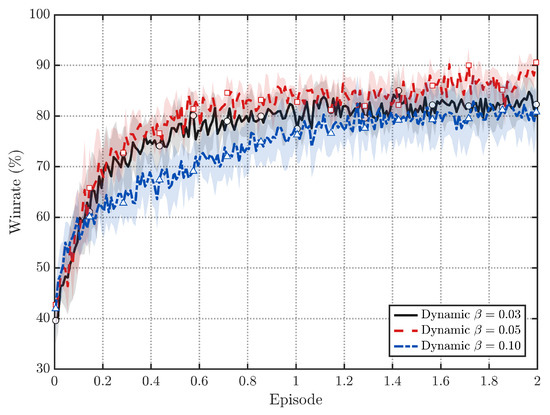

Figure 5 further studies the effect of different values. We observe that yields the best overall win-rate performance, while too small () weakens the shaping effect and too large () may introduce excessive bias, leading to inferior convergence.

Figure 5.

Effect of different in full VBRS (dynamic updated by EMA; shaded: 95% CI).

An interesting phenomenon emerges when comparing the win rate in Figure 3a, with the original objective in Figure 6. While VBRS improves the win rate, the resulting policy can attain a lower value of the original objective than the non-shaping baseline and policy-invariant shaping methods. This discrepancy empirically supports the premise in Section 3: the preset reward may be imperfectly aligned with the true adversarial goal. The PPO baseline greedily optimizes the dense heuristic components of , which yields reasonable reward scores but does not necessarily secure victories. In contrast, VBRS leverages value estimates to prioritize states with a higher winning probability, potentially sacrificing short-term heuristic points in favor of the strategic objective.

Figure 6.

Growth curve of the original objective under the preset reward .

5. Conclusions

This paper studies reward misalignment in adversarial reinforcement learning, where handcrafted dense rewards may deviate from the true task-level outcome objective and introduce optimization bias. To mitigate this issue, we proposed a Value-Based Reward Shaping (VBRS) framework that injects an intrinsic state-value estimate into the immediate reward structure. By adaptively blending the original environment reward with a learned long-horizon utility signal, VBRS encourages exploration and policy improvement toward states that are predicted to be strategically advantageous, rather than being overly driven by short-term heuristic terms. Results in a two-agent competitive simulation environment show that VBRS improves training efficiency and achieves higher final outcome performance (e.g., win rate) compared with baselines using the original reward or alternative shaping strategies, suggesting that value-based shaping can be a practical heuristic to alleviate reward-induced optimization bias in adversarial learning.

Despite these advantages, VBRS has several limitations. First, the adaptive shaping schedule introduces hyperparameters that may require tuning across tasks, and the best operating range of the shaping coefficient can be environment-dependent. Second, our evaluation focuses on learning against a fixed opponent policy; in settings with non-stationary or adaptive opponents, the learning dynamics and the stability of value-based shaping may change. Third, the current validation is conducted in a simplified low-dimensional simulation; extending to more complex observations, higher-dimensional control, or partially observable settings may require additional stabilizing techniques and systematic ablation studies.

Future work will explore several directions. First, we plan to develop more rigorous mathematical formulations to quantify the discrepancy between the shaped reward and the underlying task objective, with the goal of providing analytical or provable measures of how reward shaping affects optimality and policy bias. Second, we will extend VBRS beyond the current two-agent setting to broader multi-agent scenarios, investigating how value-based shaping interacts with non-stationarity, strategic coupling, and scalable training in competitive multi-agent benchmarks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.; methodology, G.P.; investigation, G.P.; validation, B.H. and Y.C.; formal analysis, B.H.; resources, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, B.H., G.P., and Y.C.; supervision, B.H. and Y.C.; funding acquisition, B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Program (Grant No. 62003363 and No. 62303485), the Shaanxi Province Natural Science Basic Research Program (Grant No. 2022KJXX-99), the Fundamental and Frontier Innovation Program (Grant No. 2025-QYCX-ZD-03-026), and the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (Grant No. 2025JC-YBMS-730).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Argall, B.D.; Chernova, S.; Veloso, M.; Browning, B. A survey of robot learning from demonstration. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Xu, J.; Wang, N.; Fu, B.; Ning, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Feng, C.; et al. A survey of decision-making and planning methods for self-driving vehicles. Front. Neurorobot. 2025, 19, 1451923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Jia, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, M.; Shen, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Sang, J. Mobile-agent-v2: Mobile device operation assistant with effective navigation via multi-agent collaboration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 2686–2710. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Gao, H.; Xia, Y. Distributed Pursuit–Evasion Game Decision-Making Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2025, 14, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ji, Q.; Ling, X.; Liu, Q. A comprehensive review of multi-agent reinforcement learning in video games. IEEE Trans. Games 2025, 17, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodei, D.; Olah, C.; Steinhardt, J.; Christiano, P.; Schulman, J.; Mané, D. Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.06565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R. A robust layered control system for a mobile robot. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 2003, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, H.; Ai, J. Autonomous Maneuver Decision-making Algorithm for UCAV Based on Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 164, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Song, T.; Mo, L.; Lv, M.; Lin, D. Autonomous Dogfight Decision-Making for Air Combat Based on Reinforcement Learning with Automatic Opponent Sampling. Aerospace 2025, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; McAllester, D.; Singh, S.; Mansour, Y. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 1999, 12, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Levine, S.; Abbeel, P.; Jordan, M.; Moritz, P. Trust region policy optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning PMLR, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 1889–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Hartikainen, K.; Tucker, G.; Ha, S.; Tan, J.; Kumar, V.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, A.; Abbeel, P.; et al. Soft actor-critic algorithms and applications. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05905. [Google Scholar]

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, C.; Brockman, G.; Chan, B.; Cheung, V.; Dębiak, P.; Dennison, C.; Farhi, D.; Fischer, Q.; Hashme, S.; Hesse, C.; et al. Dota 2 with large scale deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.06680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, A.P.; Ide, J.S.; Mićović, D.; Diaz, H.; Rosenbluth, D.; Ritholtz, L.; Twedt, J.C.; Walker, T.T.; Alcedo, K.; Javorsek, D. Hierarchical reinforcement learning for air-to-air combat. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 15–18 June 2021; pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, A.; Zheng, S.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. Keeping your distance: Solving sparse reward tasks using self-balancing shaped rewards. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 10376–10386. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.; Wan, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, C.X.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, D.C. Reward Models in Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.15421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.Y.; Harada, D.; Russell, S. Policy invariance under reward transformations: Theory and application to reward shaping. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–30 June 1999; Volume 99, pp. 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Laud, A.; DeJong, G. The influence of reward on the speed of reinforcement learning: An analysis of shaping. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-03), Washington, DC, USA, 21–24 August 2003; pp. 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, S.M.; Kudenko, D. Dynamic potential-based reward shaping. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS 2012), Valencia, Spain, 4–8 June 2012; pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Grześ, M.; Kudenko, D. Online learning of shaping rewards in reinforcement learning. Neural Netw. 2010, 23, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.J.; Liang, W.; Wang, G.; Huang, D.A.; Bastani, O.; Jayaraman, D.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, L.; Anandkumar, A. Eureka: Human-level reward design via coding large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.12931. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S. Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential. Electronics 2025, 14, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiewiora, E. Potential-based shaping and Q-value initialization are equivalent. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2003, 19, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, J.; Makarenko, V.; Tiomkin, S.; Kulkarni, R.V. Bootstrapped Reward Shaping. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 15302–15310. [Google Scholar]

- Devidze, R.; Kamalaruban, P.; Singla, A. Exploration-guided reward shaping for reinforcement learning under sparse rewards. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 5829–5842. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Li, B.; Jin, X.; Zeng, W. Automatic intrinsic reward shaping for exploration in deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 40531–40554. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hao, J.; Wu, F.; Fan, C. Learning to utilize shaping rewards: A new approach of reward shaping. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 15931–15941. [Google Scholar]

- Littman, M.L. Markov games as a framework for multi-agent reinforcement learning. In Machine Learning Proceedings 1994; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W. A two-stage multi-objective deep reinforcement learning framework. In ECAI 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, J.; Bartlett, P.L. Infinite-horizon policy-gradient estimation. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2001, 15, 319–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M. The definitive guide to policy gradients in deep reinforcement learning: Theory, algorithms and implementations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Badia, A.P.; Mirza, M.; Graves, A.; Lillicrap, T.; Harley, T.; Silver, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016; pp. 1928–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Han, J.; Chen, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, Z.L.; Yang, G. An air combat maneuver decision-making approach using coupled reward in deep reinforcement learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, Y.; Edwards, H.; Storkey, A.; Klimov, O. Exploration by random network distillation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.