Abstract

In line with the trend of “native intelligence”, artificial intelligence (AI) will be more deeply integrated into communication networks in the future. Quality of AI service (QoAIS) will become an important factor in measuring the performance of native AI wireless networks. Networks should reasonably allocate multi-dimensional resources to ensure QoAIS for users. Extended Reality (XR) is one of the important application scenarios for future 6G networks. To ensure both the accuracy and latency requirements of users for AI services are met, this paper proposes a resource allocation algorithm called Asynchronous Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient with Independent State and Action (A-MADDPG-ISA). The proposed algorithm supports agents to use different dimensional state spaces and action spaces; therefore, it enables agents to address different strategy issues separately and makes the algorithm design more flexible. The actions of different agents are executed asynchronously, enabling actions outputted earlier to be transmitted as additional information to other agents. The simulation results show that the proposed algorithm has a 10.41% improvement compared to MADDPG (Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient). Furthermore, to overcome the limitations of directly applying AI or manual rule-based schemes to real networks, this research establishes a digital twin network (DTN) system and designs pre-validation functionality. The DTN system contributes to better ensuring users’ QoAIS.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid commercialization of 5G, and the accelerated advancement of industrial revolution, the next generation of wireless communication technology has injected new impetus into industrial and economic development. Extended Reality (XR) is emerging as a pivotal application scenario for future mobile networks, where large-scale concurrent XR services impose stringent and heterogeneous requirements on communication, computing, and intelligence, thereby positioning DTNs as a key enablers for AI-driven, predictive, and closed-loop network optimization [1].

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) technology has rapidly developed across various industries, and intelligent applications of the Internet of Everything have deeply integrated into our lives. A series of cutting-edge application scenarios [2,3,4,5], such as smart healthcare, smart cities, smart industry, and intelligent robots, have been advancing continuously with the development of AI technology. “Native intelligence” has become one of the development visions of future networks. In order to address the various challenges that current networks struggle to resolve and to provide high-quality AI services, 6G networks should consider deep integration with AI from the outset of their architecture design [6].

Therefore, 6G native AI networks should establish an evaluation system for Quality of Artificial Intelligence Services (QoAIS) [7]. In contrast to traditional communication-oriented quality of service (QoS) standards, such as bandwidth, latency, error rate, etc., QoAIS needs to comprehensively evaluate AI service quality from multiple dimensions, including connectivity, computing power, algorithms, data, etc. The whitepaper published by 6GANA provides examples of where each type of AI service can be designed with evaluation metrics from multiple perspectives, including performance, cost, security, privacy, and autonomy [8].

Chen TJ et al. (2023) [6] mentioned that QoAIS should include at least two metrics: the accuracy of AI models and the latency of AI services. Higher-precision AI models can lead to higher accuracy, but require more resources. Therefore, it is necessary to design a reasonable resource allocation scheme to ensure QoAIS.

In recent years, the digital twin network (DTN) has emerged as a new technological trend. A DTN establishes a faithful virtual representation of a physical entity, enabling continuous mapping, iterative evolution, and bidirectional interaction between the virtual and physical domains [9]. The integration of DTNs has provided assistance for many applications, such as mobile robots [10], vehicular edge computing [11], integrated sensing and communication [12], and consumer electronics manufacturing [13]. Ref. [14] proposed generative artificial intelligence as a key enabling technology to enhance the modeling, synchronization, and slicing capabilities of digital twins. DTNs can predict future network states and pre-validate the effectiveness of intelligent strategies [15]. In cases where unreliable strategies arise, the real network can temporarily activate relatively stable manual rules to replace intelligent algorithms, mitigating the uncertainty of AI strategies.

XR technology, as one of the crucial scenarios for future 6G networks, comes with strict service requirements. Sixth-generation native AI networks need to provide specialized AI services for XR. In the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), the convergence of XR and DTNs enables innovative use cases for intelligent control systems. A representative example is the multi-tank liquid level control experiment reported in [16], where the DTN serves as a digital replica of the physical plant and is tightly integrated with an XR environment, allowing engineers to monitor system states and adjust proportional–integral controller parameters in real-time through immersive interfaces. This integration offers several notable advantages. First, XR provides an intuitive and interactive user experience; as highlighted in [17], visualization-driven interaction can significantly reduce training costs while improving operational accuracy. Second, DTNs facilitate real-time data synchronization and predictive maintenance, thereby enabling more efficient resource allocation and enhanced QoS assurance. Finally, in resource-constrained environments, the integration of edge computing and artificial intelligence can effectively reduce end-to-end latency and improve quality of experience (QoE), ultimately promoting human–machine collaboration in the context of Industry 5.0.

Deep reinforcement learning is the most widely-used AI technology in the field of resource allocation solutions. Concerning the service quality of multi-beam satellite communications, He Y et al. [18] proposed a multi-objective deep reinforcement learning-based time–frequency resource allocation algorithm. This algorithm aims to maximize both the number of users and the system throughput to the fullest extent possible. Guo Q et al. [19] consider underlay mode D2D (device-to-device)-enabled wireless networks to improve spectrum utilization. They propose a decentralized resource allocation method based on deep reinforcement learning and federated learning. This method aims to maximize total capacity and minimize overall power consumption while ensuring quality of service requirements for both cellular users and D2D users. Ref. [20] addresses the problem of communication and computing demands in the low-altitude economy and proposes a digital twin-assisted space–air–ground-integrated multi-access edge computing paradigm. Facing the challenge of wireless resource allocation in vehicle-to-UAV (V2U) communication, Li N et al. [21] propose multi-agent federated learning and dueling double deep Q-network (D3QN)-based resource allocation, to jointly optimize channel selection and power control to meet the low latency and reliability requirements.

This paper will consider an XR scenario to design a multi-dimensional resource allocation scheme. The primary objective of this paper is to address the fundamental challenge of guaranteeing the QoAIS in XR-oriented digital twin networks through intelligent resource allocation. Specifically, this study aims to achieve the following three key objectives:

- Establish a QoAIS-driven system model. This paper develops a joint optimization framework that comprehensively considers the dynamic allocation of communication, computation, and caching resources, in which AI service accuracy and inference latency are adopted as the core performance evaluation metrics.

- Construct a DTN framework with pre-validation capability. A digital twin network simulation framework is designed and implemented to enable pre-validation of AI-driven strategies, thereby reducing deployment risks in practical networks, while also providing a system-assisted human decision-making mechanism.

- Design an efficient multi-dimensional resource allocation algorithm. An enhanced multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm, referred to as A-MADDPG-ISA, is proposed to overcome the limitations of conventional methods in handling heterogeneous policy spaces and asynchronous decision-making processes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on resource allocation based on deep reinforcement learning, AI services quality enhancement, and DTNs in an XR scenario. Section 3 presents the XR-oriented system model for QoAIS assurance, including AI service modeling as well as communication and computation models. Section 4 elaborates on the resource allocation scheme based on the proposed A-MADDPG-IAC algorithm, including the optimization problem formulation and algorithm design. Section 5 evaluates the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm and system through simulation experiments. Section 6 discusses the simulation results. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Works

Current 3GPP studies on XR focus on optimizing QoS provisioning to enable effective support of XR services in 5G and future 6G systems [22]. The large-scale adoption of XR applications critically depends on the ability of future cellular systems to effectively support the stringent QoS, computational, and resource allocation requirements imposed by XR services [23]. Trinh B et al. [24] leverage the concepts of Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and Network Function Virtualization (NFV) to propose an innovative resource management scheme considering heterogeneous QoS requirements at the MEC-server level. Resource assignment is formulated by employing a DRL technique to support high-quality XR services. To accommodate the heterogeneous QoS demands of emerging applications such as XR and Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB), it is often necessary to functionally partition network capabilities according to service requirements [25]. Such service-oriented functional decomposition can be more effectively realized within a DTN, where virtualized and logically isolated network entities enable flexible management, tailored resource provisioning, and precise performance control for different service types. Z. Zhang et al. [26] combined digital twin (DT) and reliable reinforcement learning (RL) to optimize edge caching in next-generation wireless networks while ensuring system reliability. A DT-enhanced RL framework is proposed to address resource management issues in networks [27]. Wang ZC et al. [28] studied dynamic resource block (RB) allocation for real-time cloud XR video transmission and proposed two DRL-based methods. The former treats the base station as a single agent, while the latter treats all RBs as different independent agents. Chen WX et al. (2021) [29] focused on the quality of experience for VR video users during cell handovers and proposed a DRL-based approach for proactive caching, computing, and communication (3C) resource allocation to provide smooth VR video streaming for handoff users. DT and XR are considered key technologies for optimizing occupant well-being and comfort in built environments. These technologies achieve this by leveraging real-time analytics and simulations to enhance energy efficiency and minimize the carbon footprint of building operations [30,31,32]. In [33], adaptive data allocation and prioritization techniques are introduced to address heterogeneous data streams in XR-oriented digital twin systems, where transmission priorities are dynamically adjusted according to network conditions and scenario-specific requirements. Ref. [34] presents an XR-enabled remote manufacturing laboratory testbed that integrates 3D digital twin modeling with XR-based remote collaboration, leveraging 5G network slicing—such as Ultra-Reliable and Low-Latency Communications (URLLC) and eMBB—to provide ultra-reliable and low-latency communications. Demir et al. [35] propose a digital twin framework for programmable vehicular networks that utilizes deep learning-enhanced obstacle detection and ray-tracing to dynamically reconfigure base station and reconfigurable intelligent surface parameters, aiming to maintain QoS in non-line-of-sight scenarios with reduced transmit power. Mohammed et al. [36] surveyed AI-driven solutions for 6G networks and highlighted how deep reinforcement learning can be integrated with digital twins and cloud-edge computing to optimize resource allocation in space–air–ground–sea-integrated environments, addressing challenges like latency and energy efficiency.

3. System Model

This section first introduces the modeling of an XR scenario aimed at ensuring QoAIS, then provides a detailed introduction to the modeling of AI services for object detection tasks in this scenario, and finally presents the communication and computation models of the scenario. Pre-validation functionality combines historical and real-time data to predict future states, simulate scenarios, and evaluate algorithm performance (rule-based/AI-driven) against QoAIS metrics (AI service accuracy requirement and end-to-end latency requirement).

3.1. Modeling of XR Scenario

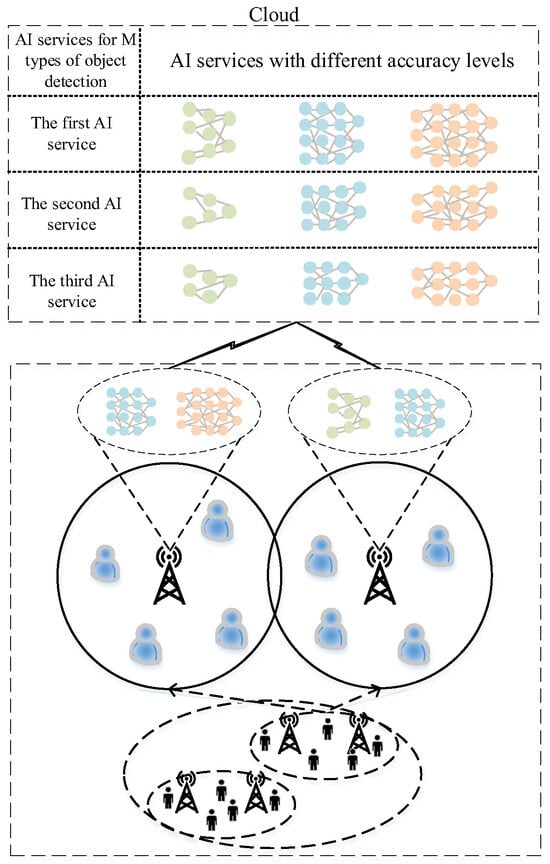

As shown in Figure 1, the scenario is modeled as a three-tier edge heterogeneous network consisting of a cloud, base stations, and users. The network comprises one cloud and groups of base stations. Assume that the users within each base station group are independent and the number of users remains constant, meaning each base station (BS) group covers users. The BS groups are represented by the set , each BS group contains two BSs, denoted as , which collaborate with each other. The users within the coverage area of each base station group can be represented as the set . The two-BS grouping represents a typical edge cooperation paradigm in future dense and collaborative wireless access networks, particularly for XR-oriented applications. Users move randomly within the coverage area of the BS group and request object detection AI services from the network.

Figure 1.

System model.

Different AI object detection tasks require different AI models, including classic AI models such as Resnet-18, VGG-19, etc. [37]. The same type of AI service has different model versions. The higher the version, the more complex the model structure and the higher the accuracy.

It is assumed that the cloud is able to cache types of AI service, represented as a set . Each AI service is equipped with varying numbers of versions, with the corresponding quantities represented as the set . Therefore, the total number of AI services is .

Different from the cloud, a BS usually has limited cache space; therefore, it is not able to cache all of the AI services. Let denote the number of AI services that can be stored in a BS; the following constraint holds:

Due to the cooperative relationship between two BSs, each BS can also provide edge AI services for users of the neighboring BS.

This paper considers the user’s selection of AI service versions to be their requirement for accuracy. In addition to this, to meet the latency sensitivity of XR services, the network needs to provide AI services with an end-to-end latency lower than the latency threshold . Therefore, the user’s QoAIS requirements are characterized by the above two metrics.

3.2. Service Model

3.2.1. Modeling of AI Services

Different from the modeling of traditional computing tasks, this paper models AI services based on the actual structure of AI models. Modern deep neural networks (DNNs) are constructed from “layers”, with each layer representing a set of similar computations [38]. An AI service is explicitly defined as a pre-trained DNN used to perform a specific AI inference task. To uniformly evaluate computational complexity, AI service inference can be formulated as the forward propagation process between layers, where the computational load depends on the parameters of each layer. Consequently, the “layer” is adopted as the minimal unit for modeling. DNNs are often composed of multiple layers, including convolutional layers, activation layers, fully connected layers, etc. This paper will consider the computation of each layer as the floating point operations per second (FLOPs), following previous work [39].

The size of the parametric quantity of the fully connected layer is , where represents the dimension of the input feature vector, represents the bias, and represents the output dimension. Therefore, the FLOPs of the fully connected layers is as follows:

The data output size of the fully connected layer is represented as (unit/bit):

where represents the bit depth, indicating the number of bits per element in the feature vector.

The parameter quantity of the convolutional layer is denoted as , where and represent the width and height of the convolution kernel, represents the bias, and represents the number of convolution kernels. Therefore, the FLOPs of the convolutional layers is

where and , respectively, represent the width and height of the feature map and represents the total number of elements in the feature map. The data output size of the convolutional layer is denoted as (unit/bit):

This work establishes a unified framework for feature selection and transmission control by abstracting AI inference into hierarchical computation and communication components. Although the current evaluation focuses on DNN-based models, the proposed layer-level abstraction is inherently architecture-agnostic. It enables seamless extension to emerging AI paradigms, including transformer-based models, reinforcement learning systems, and event-driven spiking neural networks. By treating attention blocks, policy networks, or spike-generating modules as logical layers characterized by generic metrics such as computation cost and transmission contribution, the framework can flexibly adapt its model partitioning and transmission strategies. This abstraction ensures long-term applicability amid the rapid evolution of AI architectures. In the following, the discussion focuses on AI services based on DNN models. The proposed decomposition of computational and transmission loads can be readily extended to other AI model frameworks by applying the same partitioning principle.

3.2.2. The Execution Mode of AI Services

As mentioned earlier, users request the execution of AI services within the coverage range of the BS group. Each BS can cache AI services. Therefore, based on the AI service requested by the user and the AI services cached in the BSs, the system needs to determine where the user will perform AI service inference and which AI service to allocate to the user. The following criteria are sorted by priority from high to low:

- When neither of the two BSs caches the requested type of service from the user, the cloud processes the AI service for the user and the allocated AI service for execution remains the same as the one requested by the user.

- When a BS happens to cache the AI service requested by the user, the BS processes the AI service for the user. The priority of the access BS is higher than the cooperative BS, and the allocated AI service for execution remains the same as the one requested by the user.

- When neither of the two BSs have exactly cached the AI service requested by the user, if any BS caches a higher version of the same type the BS processes the AI service for the user. The priority of the access BS is higher than the cooperative BS. After determining the user’s computing location, the allocated AI service for execution is the closest higher-version service to the requested version. This situation ensures the user’s accuracy requirements but sacrifices some latency in the above two metrics due to the more complex model structure.

- When both BSs only cache lower versions of the service, the BS processes the AI service for the user. The priority of the access BS is higher than the cooperative BS. After determining the user’s computing location, the allocated AI service for execution is the closest lower-version service to the requested version. This situation sacrifices a certain level of the accuracy requirements, but due to the simpler model structure it becomes easier to meet the latency requirements.

In conclusion, BS caching will affect both the user’s computing location and the allocation of AI services. Hence, BSs should comprehensively consider all users’ requirements for accuracy and latency when caching AI services at the network edge.

For users distributed within the same group of BSs, , represents the computing location of , where represents the AI services processed by the cloud for , represents the AI services processed by for , and represents the AI services processed by for .

The service index requested by the user is denoted as , and the service index allocated to the user for execution is denoted as , .

3.2.3. End-to-Cloud/End-to-Edge Collaborative Inference

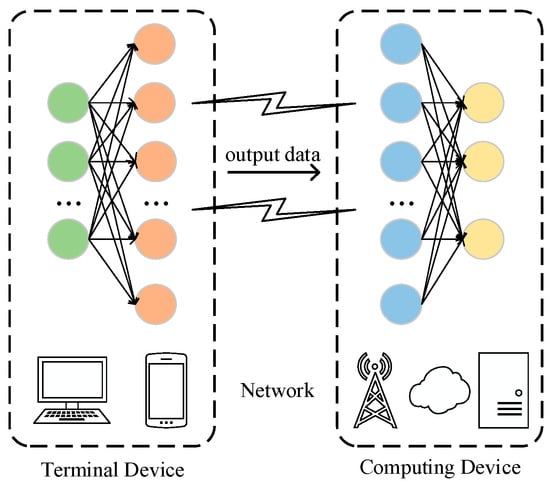

Considering that current user devices often have certain computing capabilities, after determining the computing location (BS/cloud), the user device will collaborate with the computing device to complete the AI service inference task. For the research scenario, the collaborative inference method is DNN partitioning.

DNN partitioning refers to dividing the AI model into parts at the granularity of “layers” [40], where one part of the AI model is executed on the user device. The feature data output at the partitioning layer is transmitted via the uplink channel to the computing device to perform subsequent inference tasks, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

DNN partitioning.

Due to the different partitioning points, the computational load and air interface transmission load allocated to both ends vary. Therefore, the advantage of DNN partitioning lies in its comprehensive consideration of the computational capabilities at both ends and the channel conditions, selecting the optimal partitioning point to optimize the inference latency of AI services.

Considering the principles of DNN partitioning, terminal devices often have lower computing capabilities compared to computing devices. However, due to the uncertainty of channel quality, transmission latency may become the primary factor affecting end-to-end latency. Therefore, the partitioning points can be set between the “layers” where there is a drastic drop in data output. Finally, the layers between each pair of partitioning points are bundled as “logical layers” [41]. This method significantly reduces the number of traversals and lowers the computational complexity.

After determining the partitioning points for the AI services, the local computation load for the user is represented as , the air interface transmission load is represented as , and the remaining computation load is represented as . It is worth noting that when the partitioning point is at the beginning of the model it indicates that there is no local computation, , and represents the initial size of the input image. When the partitioning point is at the end of the model, it indicates that the inference task is executed entirely locally, ; .

3.3. Communication Model

In this research scenario, based on the 3GPP standard [42], channel modeling is accomplished using Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) technology. The total bandwidth of the base station is denoted by , and communication resources are allocated to access users in terms of resource blocks (RBs), with the total number of assignable RBs denoted by . From a scheduling perspective, RBs serve as the fundamental unit for allocating air interface resources to individual users in the time–frequency domain. Considering that the output data size of AI services is very small, downlink transmission is neglected and only the uplink transmission process is discussed.

The number of RBs allocated to a user is , , therefore the bandwidth allocated to this user is

where represents the number of subcarriers contained in one RB and represents the subcarrier bandwidth.

The uplink transmission rate of a user is modeled as

where represents the channel loss between user and the access BS, is the antenna gain, represents the uplink transmission power of user , and represents the noise power spectral density.

In summary, the transmission delay during the execution of AI tasks by users can be obtained. When users collaborate with the cloud to execute inference tasks, includes the round-trip delay to the cloud. In this research scenario, this delay is assumed to be a constant value with an additional delay while the cache needs to reload after missing; when users collaborate with cooperative BSs to execute inference tasks, includes the transmission delay between the two BSs. In this research scenario, the transmission between the two BSs is assumed to be wired transmission, with a fixed delay . Therefore, the total transmission delay T for a user can be represented as the following function:

3.4. Computation Model

The computation model for the research scenario should be discussed in three steps: (1) Determination of the user’s computing location. (2) The user device executes a portion of the AI task locally, with computational load , and transmits data through the channel to the cloud or BS, with transmission load . (3) The cloud or BS executes the remaining portion of the AI task, with computational load .

The computing resources of the user device and BS are limited, represented by and , respectively (in FLOPs). Assuming the computing resources at the cloud are unlimited, the computational latency at the cloud can be ignored.

In a group of BSs, the users whose computations are processed at are represented by the set , with , denoting the number of users collaborating with for computation. The users whose computations are processed at the cloud are represented by the set , with , denoting the number of users collaborating with the cloud for computation. The variables and satisfy the following constraints:

allocates computing resources to users belonging to the set . User is allocated computing resources , by the BS.

In summary, the total computation latency for user during AI-task execution can be expressed as the following function:

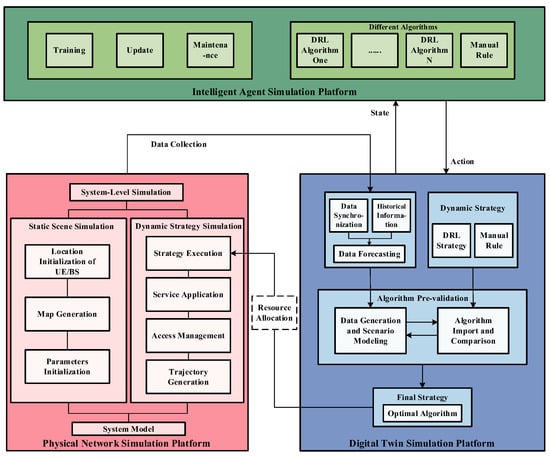

3.5. Architecture Design of the Simulation Platform

This paper will rely on a DTN architecture to build a simulation platform to validate the effectiveness of its algorithms and schemes. As shown in Figure 3, the designed simulation platform architecture consists of a physical network simulation platform, a digital twin simulation platform, and an intelligent agent simulation platform.

Figure 3.

The architecture of the DTN simulation platform.

The physical network simulation platform completes both static scenario simulation and dynamic strategy simulation. Specifically, the system-level simulation platform extracts the information features of the research scenario; initializes the simulation scenario by deploying the positions of the BSs and users, as well as generating maps; and initializes the network parameters by building channel models, AI service models, and configuring the parameters of base stations and users. Due to the highly dynamic nature of the simulation scenario, the system-level simulation platform needs to simulate the dynamics of users by managing access, mobility patterns (trajectories, speeds, etc.), and service requests. Additionally, it should support the dynamic loading and execution of strategies by designing flexible program interfaces. The physical network simulation platform combines static scenes and dynamic policies for overall system-level simulation, which is used to simulate the physical domain.

The digital twin simulation platform comprises functionalities such as data collection and synchronization, temporal state prediction, scenario simulation and construction, algorithm interaction and pre-validation, and final decision-making. The digital twin simulation platform supports periodic data collection and synchronization with the physical network simulation platform to achieve the digital replication of the physical domain. This simulation platform can store historical network data and predict the network status for the next time period. Furthermore, based on the predicted information for future time periods, the digital twin simulation platform constructs scenarios in a manner similar to the physical network simulation platform. Finally, the platform abstracts raw data into high-dimensional data and provides it to the intelligent agent simulation platform for decision-making. It also offers pre-validation functionality for different algorithms, selecting the optimal algorithm to drive the execution of strategies in the physical network simulation platform.

The intelligent agent simulation platform includes functionalities such as model training and updating, algorithm comparison, and algorithm maintenance. This platform can model optimization problems from various perspectives such as state space and action space and optimization objectives based on the high-dimensional data processed in the digital twin simulation platform. The platform will support multiple dynamic AI algorithms, train models based on the state space and optimization objectives, and compare the performance and efficiency of different AI algorithms.

4. MADRL-Based Resource Allocation Solution

Traditional multi-agent algorithms [43,44,45,46] include Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization (MAPPO), Communication Neural Net (CommNet), Bidirectionally Coordinated Network (BicNet), MADDPG, etc. These algorithms are widely used in various fields and play a similarly important role in resource allocation algorithms. MAPPO extends the proximal policy optimization framework to multi-agent settings by adopting centralized training with decentralized execution. CommNet enables agents to continuously exchange hidden-state information through a shared communication network. By employing an averaging-based communication mechanism, CommNet facilitates implicit coordination among agents. BicNet utilizes a bidirectional recurrent neural network architecture to coordinate agent behaviors, thereby enhancing cooperative decision-making. MADDPG follows a centralized training and a decentralized execution paradigm, where each agent maintains an independent actor–critic network. During training, the centralized critic has access to the observations and actions of all agents, effectively mitigating the non-stationarity issue inherent in multi-agent environments. This design makes MADDPG particularly suitable for resource allocation problems with coupled agent interactions.

This section first models the problem based on the optimization objective, subsequently constructing a Markov model for the target problem. Finally, it introduces the algorithmic structure of A-MADDPG-ISA and provides the algorithmic process.

4.1. Modeling Optimization Objectives

In XR-oriented networks, user-perceived QoAIS is jointly determined by the intelligence level of AI inference and the responsiveness of service delivery. In particular, XR applications are highly sensitive to both inference accuracy and end-to-end latency, where insufficient accuracy degrades immersive perception, while excessive latency severely disrupts real-time interaction. Therefore, guaranteeing QoAIS requires a holistic optimization framework that simultaneously accounts for these two tightly coupled performance dimensions. As mentioned earlier, this method will jointly optimize the QoAIS of XR users from two perspectives: the accuracy of AI services and the latency.

To model the optimization objective, it is necessary to quantify the QoAIS of XR users. Therefore, we define the accuracy score and the latency assurance score for user . Then, the total score of QoAIS is represented as follows:

where and represent scaling factors.

The accuracy score of user is related to the AI service version assigned to it for execution and it is defined as follows:

where when the assigned AI service version is greater than or equal to the version requested by user , ; otherwise, . represents the score when the user’s accuracy requirement is satisfied. Assigning a higher version of the AI service will increase resource demand, thus introducing to denote the penalty score for version difference, and represents the difference between the requested and assigned versions; the greater the version difference, the greater the penalty.

To capture this behavior, the accuracy score is defined based on the relationship between the requested and assigned AI service versions. When the assigned version satisfies or exceeds the user’s requirement, the user is considered accuracy-satisfied; otherwise, a penalty is imposed that increases with the version mismatch. This design ensures that assigning higher-than-required AI service versions is encouraged only when sufficient resources are available, while unnecessary over-provisioning is discouraged through increased resource consumption.

End-to-end latency is another critical QoAIS dimension in XR services, encompassing both communication delay and computation delay. According to the communication model and the computation model, the end-to-end latency for user to execute AI services can be obtained as follows:

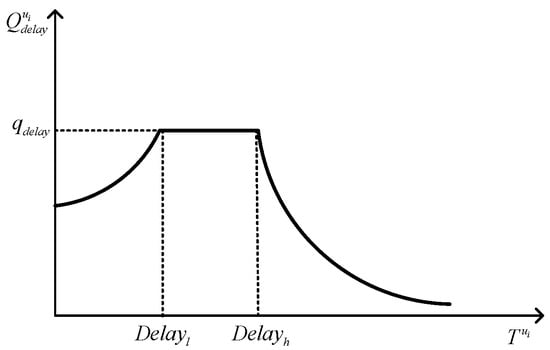

The user’s latency assurance score is related to the latency constraint , defined as follows:

where and are slope parameters, as shown in Figure 4. When , set the maximum score; when , set a score that decreases as the delay decreases, because when the user’s delay requirement is satisfied there is no need for more resources to pursue a smaller delay and resources should be left for users who need them more; when , the user’s delay requirement is not satisfied, so this method designs a score that sharply decreases as the delay increases. In addition, requiring , where the score for not meeting the delay requirement should decrease more significantly.

Figure 4.

The score curve for latency assurance.

Once a user’s latency requirement is satisfied, allocating additional resources to further reduce latency yields diminishing QoAIS gains and these should instead be prioritized for other users. Conversely, failing to meet the latency constraint has a significant negative impact on user experience and must be strongly penalized in the optimization process.

In summary, the system-level optimization objective is to maximize the aggregate QoAIS of all users served by a group of cooperative base stations, subject to constraints of communication and computation resources. For a group of BSs, the system’s optimization objectives can be expressed as follows:

where Equation (15) represents the optimization objective of maximizing the overall QoAIS of the system. and denote the allocation of RB resources to users by the BS is less than the total communication resources, while and indicate the allocation of computing resources to users by the BS is less than the total computing resources.

4.2. Markov Process Modeling

Based on the optimization objective, we establish the Markov process (MDP) [47] of the problem to model the reinforcement learning agent. The Markov process consists of four elements: the state space , the action space , the state transition probability , and the reward . This formulation allows dynamic interactions among caching, communication, and computing resources to be captured in a sequential decision-making framework.

Considering the intrinsic coupling between AI service caching decisions and communication–computing resource allocation, a centralized agent would suffer from excessively large state and action spaces. Moreover, caching strategies exhibit slower temporal dynamics compared to communication and computation resource allocation. In an independent BS group, based on the characteristics of the algorithm proposed, we set up two agents, denoted as and . is responsible for the edge caching of AI services within the system, while is responsible for the allocation of communication resources and computing resources within the system.

- (1)

- State space: In the scenario, users select an access BS based on access algorithms and randomly request AI services. The system state must reflect both the user service demands and the network conditions. Agents can directly obtain information such as service requests, access states, and channel states. Therefore, the state space is as follows:where represents the index of the access BS that user connects to, represents the index of the AI service requested by the user, represents the channel state between the user and the access BS, and represents the total number of users. For , the state is set to include global information about user access and service requests. For , the state is set to include global information about user access and channel states.

- (2)

- Action space: The two agents are used to address different issues, so the action space is as follows:where represents the index of the AI service cached by , denotes the cache quantity of a single BS, and represents the total count of AI service caches; and , respectively, represent the proportion of RB resources and computing resources allocated to user .

- (3)

- Reward function: To address the objective problem, the reward function should be strongly correlated with the optimization objective. Therefore, rewards are defined separately for the two agents as follows:

The caching strategy of the BSs affects the user’s computing location to some extent, and computing in either cloud or cooperative BS introduces additional transmission latency. Therefore, we introduce the penalty factors and , where and represent the weighting coefficients of the penalty. In addition, the penalty for repeated caching at the BS can reduce the occurrence of repeated caching strategies, thereby avoiding wastage of caching resources. represents the number of repeated caches at , and represents the weighting coefficients of the penalty. and represent scaling factors.

4.3. A-MADDPG-ISA-Based Resource Allocation Algorithm

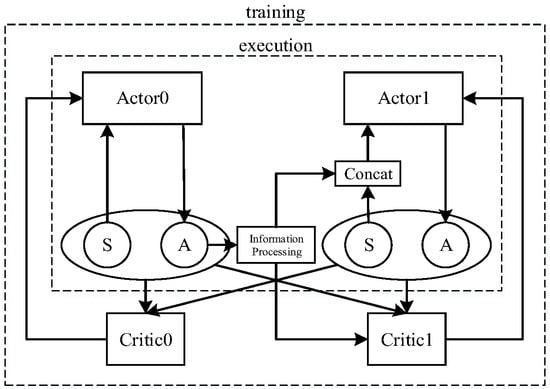

To address the correlated allocation of caching, communication, and computing resources in AI-service-driven networks, this paper proposes an enhanced algorithm termed A-MADDPG-ISA. While the standard MADDPG framework employs independent actor–critic networks for each agent, with consistent state–action dimensions and centralized critic-based information exchange, it struggles to capture the inherent dependencies among resource strategies. Specifically, caching decisions directly influence both service execution and computational offloading locations, creating indirect coupling with communication and computing allocations. Conventional MADDPG, with its homogeneous agents, yields decoupled local strategies that fail to model these inter-resource relationships. The proposed algorithm decomposes joint resource allocation into two subproblems: obtaining a global caching strategy and a unified strategy for joint communication–computing resources. Furthermore, it enhances inter-agent information transmission within the actor–critic architecture, as illustrated in Figure 5, ensuring coordinated optimization reflective of real world dependencies.

Figure 5.

The architecture of A-MADDPG-ISA.

In the proposed algorithm architecture, different agents can address completely inconsistent problems. In the scenario, one agent is responsible for caching strategy, while the other is responsible for communication and computation resource allocation strategy. Additionally, to represent the one-way influence of caching strategy on communication and computation resource strategies, an extra information transmission is introduced. Because cannot directly obtain the AI service cache information during the state observation period, it will wait until has completed action output. Then, it will synthesize the observed information along with the unilaterally transmitted cache information to jointly complete the strategy output. This ultimately results in the asynchronous execution of algorithm actions. The algorithm process is illustrated as follows (Algorithm 1):

| Algorithm 1 A-MADDPG-IAC algorithm |

| 1 Initialize actor network and critic network; 2 Initialize target network and critic network and replay buffer R 3 for episodes = 0 to E do 4 initialize system state 5 for step = 0 to T do 7 if the index of the agent is equal to 0 then 10 else if the index of the agent is equal to 1 then 13 end if in R 15 sample a random minibatch of N tuples from R 16 compute target value for each agent in each tuple 17 compute critic gradient estimation and actor gradient estimation 18 update the networks based on Adam using the above gradient estimators 19 update the target networks 20 end for 21 end for |

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

5.1. Simulation Setup

The simulation setup includes one group of BSs, eight users, and the area of the map is 1000 m × 500 m. The coordinates of the two BSs are and , respectively. Each group of users moves randomly towards the opposite BS and eventually converges at the outermost edges of the two BSs. The users move a total of 50 steps, with each step lasting 10 s. This movement pattern ensures that users move in an interleaved and random manner. Additionally, the number of users accessing the same BS will change based on the users’ movement trajectories, providing a more comprehensive simulation of real coverage scenarios. The user’s movement trajectory consists of a total of 50 steps, with the simulation divided into 50 discrete time intervals. Therefore, a complete round of simulation consists of 50 steps, representing one episode. At each discrete time step, users randomly request AI services from the network, while the BSs allocate caching, communication, and computing resources accordingly based on the system’s state. The simulation includes a total of 12 object detection AI services, namely: resnet18, resnet34, resnet50, res-net101, resnet152, vgg11, vgg13, vgg16, vgg19, densenet121, densenet169, and densenet201. Among these, resnet50, vgg16, and densenet169 are designated as hot services in the simulation scenario, meaning their probability of being requested is higher. Each BS is configured to cache three AI services.

The specific simulation parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

System model parameters.

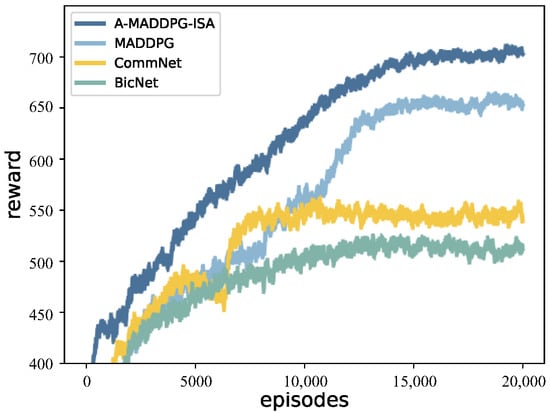

5.2. Algorithm Results Analysis

To validate the performance of the proposed algorithm, we compare it with three other multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithms, including BicNet, CommNet, and MADDPG. As shown in Figure 6, the results indicate the final convergence results: A-MADDPG-ISA > MADDPG > CommNet > BicNet. This is because unlike the CommNet and BicNet algorithms, the MADDPG algorithm architecture allows different agents to have independent actor and critic networks. This architecture makes the actions between different agents more flexible and diverse, making it easier for it to extend to highly dynamic network scenarios.

Figure 6.

Comparison of BicNet, CommNet, MADDPG and A-MADDPG-ISA.

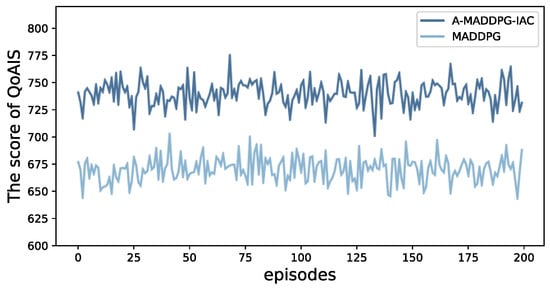

To further demonstrate the improved performance of the proposed algorithm compared to the MADDPG algorithm, as shown in Figure 7, a simulation with 200 episodes to compare the QoAIS scores of the two algorithms is conducted. Comparing the average of 200 episodes, the proposed A-MADDPG-ISA algorithm shows an improvement of about 10.41% compared to MADDPG.

Figure 7.

Comparison of QoAIS scores between A-MADDPG-ISC and MADDPG.

To reflect the system’s guarantee of user QoAIS performance, we measure the number of users simultaneously, meeting both accuracy and latency requirements as a comparative metric. The accuracy-satisfaction condition is defined as the allocation of an AI service version to a user being greater than or equal to the version requested by the user, i.e., ; the latency-satisfaction condition is defined as .

This simulation sets user trajectories as the predictive information for the DTN. A Conv-LSTM network is employed to forecast the future positions of users, with parameters set to predict 1 step based on the preceding 20 steps. Therefore, the process is as follows:

- The physical network simulation platform runs for 20 steps to accumulate historical information. These 20 steps are not used for subsequent performance comparisons.

- The digital twin simulation platform synchronizes information from the physical network simulation platform and predicts the next step of users based on historical information.

- The digital twin simulation platform constructs the scenario and simulates the services based on the predicted information.

- Based on the pre-validation functionality, the system compares the performance of different algorithms within the intelligent agent simulation platform and selects the optimal algorithm.

- The optimal algorithm is utilized to drive the physical network simulation platform to run the next step.

- The system loops through steps 2 to 5 until the physical network simulation platform completes its entire run.

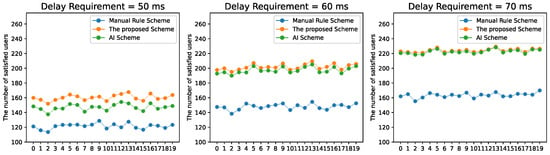

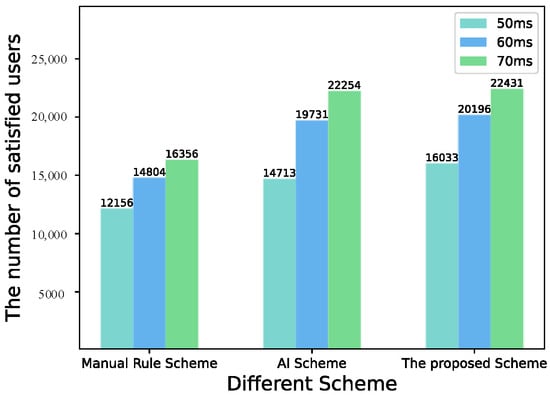

Through Figure 8, the results indicate that the performance of the system-assisted manual decision-making scheme is superior to the other two schemes. This indicates that the DTN pre-verification system designed helps to ensure users’ QoAIS. Additionally, with the relaxation of latency requirements, the number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously increased in three schemes, but the proposed scheme and the AI scheme show a more significant increase. Furthermore, the effect of the AI scheme becomes increasingly closer to the proposed scheme as the latency requirements are relaxed.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously under different latency requirements.

Figure 9 displays the total number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously within 100 episodes under different latency requirements, providing a more noticeable representation of the performance gain of the proposed scheme.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the total number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously under the three schemes.

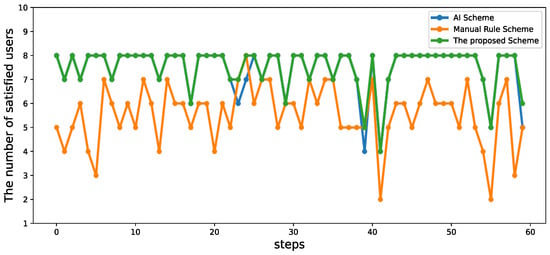

Additionally, the results indicate the data for two episodes with a latency requirement set to 70 ms (including 60 steps), comparing the number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously at different steps, as shown in Figure 10. The horizontal axis represents the steps, while the vertical axis represents the number of users.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the number of users meeting both QoAIS metrics simultaneously at different steps.

Through this comparison, the results indicate that, in most cases, the performance of the proposed scheme is superior to the manual rule scheme, while the coordinate points overlap with the AI scheme. This indicates that the AI algorithm proposed is more reliable in the vast majority of cases and the DTN system will choose this algorithm to drive the physical network. However, in a few cases, it can be observed that the coordinates of the proposed scheme overlap with those of the manual rule scheme, while also outperforming the AI scheme. This situation indicates that the pre-validation system selects the manual rules algorithm to make decisions for the current step after comparing different algorithms. The occurrence of this situation is due to the uncertainty of AI algorithm strategies. AI may not always provide optimal strategies for every network state. In such cases, the pre-validation system can anticipate this uncertainty in advance. After comparison, it chooses to drive the physical network using a relatively fixed manual rule algorithm, thereby avoiding potential network deterioration caused by erroneous AI algorithm strategies. Additionally, another representative case can be observed at the last coordinate point. This indicates that after comparison, the DTN system did not select either the algorithm proposed nor the manual rule, but chose another built-in AI algorithm, validating the system’s optimization capability. Therefore, this simulation can demonstrate the effectiveness of the DTN pre-validation system. The system-assisted manual decision-making scheme proposed contributes to better ensuring users’ QoAIS.

6. Discussion

Based on the algorithm parameters, configured as above, the proposed algorithm was trained for 20,000 episodes. To validate the effectiveness of the DTN system designed in this paper, three schemes will be set up for comparison.

- (1)

- Manual rules scheme: This scheme does not activate the DTN system. It simulates the mode wherein a fixed manual rule drives the physical network directly. In this scheme, the caching strategy is fixed to cache hot AI services, while the allocation strategy for communication and computation resources is fixed a even distribution.

- (2)

- AI scheme: This scheme does not activate the DTN system. The algorithm proposed in this paper will be directly applied to the physical network simulation platform for simulating the mode wherein AI drives the physical network directly.

- (3)

- System-assisted manual decision-making scheme: This scheme activates the DTN system, which periodically synchronizes information from the physical network and predicts future information based on historical data. Then, it simulates the scenarios for future time slots and pre-validates the performance of dynamic AI algorithms and manual rules within these simulated environments. When the physical network reaches the predicted time slot mentioned above, it will utilize the previously selected optimal algorithm by the DTN pre-validation system to provide the current strategy.

Figure 7 further confirms that A-MADDPG-ISA achieves a consistently higher QoAIS score than MADDPG over long-term training, indicating its superior capability in jointly optimizing inference accuracy and service latency. Unlike baseline algorithms that tend to favor either communication or computation efficiency, the proposed method effectively balances multi-dimensional resources, leading to more stable QoAIS performance.

We conducted 100 episodes of simulations to compare the two aforementioned schemes, while also illustrating the cases for different values of (50 ms, 60 ms, and 70 ms), as depicted in Figure 8. To ensure smoother curves, we averaged the values every 5 episodes, resulting in a total of 20 points for each curve. As shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, as the latency threshold is relaxed, all schemes benefit from increased feasibility; however, the proposed scheme consistently outperforms the manual rule and AI schemes. This highlights the importance of pre-validation in mitigating the uncertainty and performance degradation caused by directly deploying AI-driven strategies in dynamic environments.

Overall, the above simulation results demonstrate that the proposed scheme consistently outperforms the baseline manual and AI schemes under different latency constraints, effectively improving the number of users simultaneously satisfying QoAIS requirements. These observations highlight the benefit of integrating digital twin-based pre-validation with intelligent resource allocation.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, an XR-oriented system model is developed and evaluated through mathematical modeling and simulation, wherein the QoAIS is adopted as the primary optimization objective. Specifically, both AI service accuracy and end-to-end latency are jointly considered as the two fundamental performance metrics for characterizing users’ QoAIS. To effectively balance and guarantee these metrics, an advanced multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based resource allocation algorithm, termed A-MADDPG-ISA, is proposed. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm consistently outperforms representative baseline methods, including MADDPG, CommNet, and BicNet, achieving superior QoAIS optimization for XR users. As a result, the proposed framework provides a more reliable and effective approach for ensuring users’ QoAIS in dynamic XR scenarios. Future work will enhance the generality and practicality of the proposed framework. By leveraging a layer-level abstraction of computation and communication, the framework can be extended beyond DNN-based models to emerging AI architectures. Moreover, robustness in highly dynamic and realistic deployment scenarios will be improved through online and federated learning to adapt to mobility, channel variations, and environmental uncertainty. Finally, resource optimization will evolve towards a cross-layer, multi-objective formulation, jointly considering latency, energy consumption, and AI inference accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and Y.G.; methodology, J.Z.; software, J.Z., Y.L. and Z.Z.; validation, Y.G. and X.W.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, Y.G.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, Y.L. and Z.Z.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications-China Mobile Research Institute Joint Innovation Center (Grant No. A2023177).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinyao Wang was employed by the company China Mobile Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, Z.; Xiong, C.; Ni, H.; Wang, D.; Tao, Y.; Sun, T. Standard evolution of 5G-advanced and future mobile network for extended reality and metaverse. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2023, 6, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Pham, Q.-V.; Pathirana, P.N.; Ding, M.; Seneviratne, A.; Lin, Z.; Dobre, O.; Hwang, W.-J. Federated Learning for Smart Healthcare: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Somayaji, S.R.K.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Alazab, M.; Maddikunta, P.K.R. A review on deep learning for future smart cities. Internet Technol. Lett. 2022, 5, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.H.; Pilati, F.; Qu, T.; Huang, G.Q. Digital twin-enabled smart industrial systems: Recent developments and future perspectives. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 34, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Bao, Y. A review on human-computer interaction and intelligent robots. Int. J.-Form. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2020, 19, 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Deng, J.; Tang, Q.; Liu, G. Optimization of Quality of AI Service in 6G Native AI Wireless Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.J.; Chen, T.J.; Peng, C.H.; Wang, J.; Deng, J.; Tao, X.F.; Liu, G.Y.; Li, W.J.; Yang, L.; et al. Task-Oriented 6G Native-AI Network Architecture. IEEE Netw. 2023, 38, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6GANA TG1. 6G Network AI Concept and Terminology. In Proceedings of the 6G Alliance of Network AI, Online, 19 January 2022.

- Lai, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Ma, W.; Gan, L.; Xie, S.; Li, G. Deep learning based traffic prediction method for digital twin network. Cogn. Comput. 2023, 15, 1748–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X. A digital twin dynamic migration method for industrial mobile robots. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, E.; Hawbani, A.; Al-Dubai, A.Y.; Tan, Z.; Hussain, A. A digital twin-assisted intelligent partial offloading approach for vehicular edge computing. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 3386–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y. Joint vehicle connection and beamforming optimziation in digital twin assisted integrated sensing and communication vehicular networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 32923–32938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Qi, L.; Zhou, X.; Yan, H.; Xia, X.; Dou, W. Digital twin-assisted edge service caching for consumer electronics manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 3141–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; You, X. Wireless network digital twin for 6g: Generative ai as a key enabler. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2024, 31, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhtiar Al Zami, M.; Shaon, S.; Khanh Quy, V.; Nguyen, D.C. Digital twin in industries: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 47291–47336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeršov, S.; Tepljakov, A. Digital Twins in Extended Reality for Control System Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 43rd International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Milan, Italy, 7–9 July 2020; pp. 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kamdjou, H.M.; Baudry, D.; Havard, V.; Ouchani, S. Resource-Constrained EXtended Reality Operated With Digital Twin in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 928–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sheng, B.; Yin, H.; Yan, D.; Zhang, Y. Multi-objective deep reinforcement learning based time-frequency resource allocation for multi-beam satellite communications. China Commun. 2022, 19, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Tang, F.; Kato, N. Federated Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation in D2D-Enabled 6G. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sun, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, J.; Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Liu, J.; Leung, V.C.M. Digital Twin-Assisted Space-Air-Ground Integrated Multi-Access Edge Computing for Low-Altitude Economy: An Online Decentralized Optimization Approach. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Song, X.; Li, K.; Jiang, R.; Li, J. Multiagent Federated Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Enabled Resource Allocation for an Air–Ground-Integrated Internet of Vehicles Network. IEEE Internet Comput. 2023, 27, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esswie, A.A.; Repeta, M. Evolution of 3GPP Standards Towards True Extended Reality (XR) Support in 6G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom), Istanbul, Türkiye, 4–7 July 2023; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Deng, Y.; Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Aghvami, A.H. Cellular-Connected Wireless Virtual Reality: Requirements, Challenges, and Solutions. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, B.; Muntean, G.-M. A Deep Reinforcement Learning-based Resource Management Scheme for SDN-MEC-supported XR Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2022; pp. 790–795. [Google Scholar]

- Richart, M.; Baliosian, J.; Serrat, J.; Gorricho, J.-L. Resource Slicing in Virtual Wireless Networks: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2016, 13, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Chen, M.; Xu, D.; Cui, S. Digital Twin-Assisted Data-Driven Optimization for Reliable Edge Caching in Wireless Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2024, 42, 3306–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Yin, Z.; Luan, T.H.; Shen, X. Toward Enhanced Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Management via Digital Twin: Opportunities, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Netw. 2025, 39, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wu, J. QoE-based Deep Reinforcement Learning for Resource Allocation in Real Time XR Video Transmission. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC), Dalian, China, 10–12 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Song, Q.; Lin, P.; Guo, L.; Jamalipour, A. Proactive 3C Resource Allocation for Wireless Virtual Reality Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanijavid, A.; Konstantzos, I.; Liu, X. Challenges and opportunities of occupant-centric building controls in real-world implementation: A critical review. Energy Build. 2024, 308, 113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, S.; Jin, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, S. X-Space: A Tool for Extending Mixed Reality Space from Web2D Visualization Anywhere. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Singapore, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, F.B.; Al-Faiz, H.; Hasini, H.; Al-Bazi, A.; Kazem, H.A. A comprehensive review of the dynamic applications of the digital twin technology across diverse energy sectors. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoreau, M.; Simiscuka, A.A.; Muntean, G.-M. aDapT-XR: Adaptive Data Allocation and Prioritization for Synchronizing Real and Virtual Worlds in XR Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting (BMSB), Dublin, Ireland, 11–13 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, K.; Pauanne, A.; Hänninen, T.; Kela, J.; Rantakokko, T.; Piri, E.; Prokkola, J.; Marques, P.; Alves, T.; Haapola, J.; et al. Addressing 3D Digital Twin in Xr Remote Fab Lab Over Sliced 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2025 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), Poznan, Poland, 3–6 June 2025; pp. 506–511. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, U.; Pradhan, S.; Kumahia, R.; Roy, D.; Loannidis, S.; Chowdhury, K. Digital Twins for Maintaining QoS in Programmable Vehicular Networks. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Murad, S.S.; Albeyboni, H.J.; Soltani, M.D.; Ahmed, R.A.; Badeel, R.; Chen, P. Supporting Global Communications of 6G Networks Using AI, Digital Twin, Hybrid and Integrated Networks, and Cloud: Features, Challenges, and Recommendations. Telecom 2025, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Zhang, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X. Joint Optimization of Video-Based AI Inference Tasks in MEC-Assisted Augmented Reality Systems. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2023, 9, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Chen, X.; Zeng, L.; Yu, S.; Chen, L. Joint Multiuser DNN Partitioning and Computational Resource Allocation for Collaborative Edge Intelligence. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 9511–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.F.; Hu, W.B.; Huang, J.W.; Wang, J. Joint multi-user DNN partitioning and task offloading in mobile edge computing. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 144, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.P.; Hauswald, J.; Gao, C.; Rovinski, A.; Mudge, T.; Mars, J.; Tang, L. Neurosurgeon: Collaborative intelligence between the cloud and mobile edge. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2017, 45, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Sun, Y.; Wen, D.; Pan, G.; Zhang, S. End-to-End Delay Minimization based on Joint Optimization of DNN Partitioning and Resource Allocation for Cooperative Edge Inference. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, China, 10–13 October 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP. Study on Channel Model for Frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz. TR. 38.901; 3rd Generation Partnership Project: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Tang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.-C. Joint Optimization of Handover Control and Power Allocation Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13124–13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, S.; Szlam, A.; Fergus, R. Learning Multiagent Communication with Backpropagation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2016. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2016/file/55b1927fdafef39c48e5b73b5d61ea60-Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- Peng, P.; Wen, Y.; Yang, Y.D.; Yuan, Q.; Tang, Z.; Long, H.; Wang, J. Multiagent bidirectionally-coordinated nets: Emergence of human-level coordination in learning to play starcraft combat games. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.10069. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, R.; Wu, Y.; Tamar, A.; Harb, J.; Abbeel, P.; Mordatch, L. Multi-Agent Actor-Critic For Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2017. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/68a9750337a418a86fe06c1991a1d64c-Paper.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- Allen, C.; Parikh, N.; Gottesman, O.; Konidaris, G. Learning Markov State Abstractions for Deep Reinforcement Learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2021; pp. 8229–8241. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2021/file/454cecc4829279e64d624cd8a8c9ddf1-Paper.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.