1. Introduction

In recent years, with the gradual advancement of the “dual-carbon” strategy, the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) in the transportation sector has increased rapidly, demonstrating significant advantages in the energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction [

1,

2]. However, the large-scale integration of EVs not only accelerates the development of electric transportation systems but also creates a strong spatiotemporal coupling between transportation networks and distribution grids. The spatiotemporal trajectories and charging demands of EVs are tightly bound to traffic flows and energy flows, causing the operation states, resource allocation, and scheduling strategies of both networks to mutually influence one another [

3,

4,

5]. Against this backdrop, achieving collaborative optimization of energy and transportation systems while ensuring grid security and transportation efficiency has become a key research focus in integrated energy system research [

6,

7].

Traditional methods for analyzing and scheduling power–transportation systems mostly rely on single-source data and static models [

8,

9], which fail to fully mine the information contained in the heterogeneous data. In recent years, multimodal data fusion has emerged as a promising approach, combining traffic flow, charging station operation, grid states, geographic information, and weather data to describe the dynamic processes of both networks from a higher-dimensional perspective [

10,

11]. Meanwhile, incorporating physics-informed priors can effectively mitigate the uncertainties of purely data-driven approaches by embedding physical principles such as power flow equations, traffic flow conservation, and charging mechanisms into model structures, thereby enhancing interpretability and reliability of forecasting and optimization results [

12,

13].

Existing studies have made progress in collaborative optimization of transportation and power grids. For instance, some works employ bi-level optimization frameworks to coordinate road traffic flow and charging load allocation [

14], others use multi-agent reinforcement learning for distributed scheduling [

15], and still others apply graph neural networks (GNNs) to capture spatial dependencies between the two systems [

16]. However, these methods often overlook the benefits of multimodal data fusion, and some lack explicit modeling of high-order cross-domain correlations. Therefore, balancing real-time performance and global optimality while ensuring robustness under uncertain environments remains a critical challenge [

17].

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a unified modeling and response framework—as illustrated in

Figure 1—aimed at providing theoretical support and a technical pathway for the deep integration of energy and transportation systems in future smart cities. The work focuses on the collaborative optimization and scheduling of power–transportation coupled networks by integrating multi-modal data and physics-informed priors. The data perception layer extracts information through pedestrian flow detection, traffic flow collection, and user behavior analysis, constructing a comprehensive multi-modal feature input that encompasses traffic conditions, power grid states, charging behaviors, and user response probabilities. Specifically, user response probability is quantified via logistic regression incorporating sensitivity to incentive mechanisms, thereby accurately characterizing users’ willingness to participate in scheduling. The coupling modeling layer constructs a hypergraph structure that jointly represents the transportation, charging, and power systems by embedding physical laws such as power flow balance and traffic flow conservation. The coupling modeling layer explicitly encodes high-order interdependencies among system components and integrates user response features to enhance the framework’s practical applicability. The optimization decision-making layer designs a distributed multi-agent scheduling strategy that fuses the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) with federated learning. Leveraging real-time data distribution, user response feedback, and an AI-driven adaptive matching mechanism, the optimization decision-making layer dynamically adjusts model parameter update rules and optimization step sizes to ensure stable performance across diverse scenarios. The strategy not only improves prediction accuracy and computational efficiency but also guarantees data privacy and system scalability.

Finally, the validation and application layer conducts comprehensive case studies based on a modified IEEE 69-bus distribution network integrated with real-world traffic flow and EV charging data. Evaluation results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves significant overall benefits, including substantial reduction in grid peak load, lower operational costs, and enhanced system stability.

2. Spatiotemporal Modeling Based on Multimodal Data

2.1. Real-Time Crowd Flow Perception Algorithm

To meet the real-time demand for crowd flow monitoring at the charging system entrances, this section proposes a targeted crowd density detection method that integrates environment-adaptive processing and a dual-threshold dynamic statistical method—building on prior advancements in crowd dynamics analysis where the D-STGCN model enables reliable dynamic pedestrian trajectory prediction [

18] and the PTP-STGCN model effectively captures group interaction patterns in dense crowds [

19], both underscoring the value of high-precision crowd-related data for spatiotemporal demand forecasting. This proposed method can stably extract information even under complex lighting and background conditions, providing accurate pre-input for subsequent charging load prediction and scheduling optimization. First, the monitored video frames are processed using Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) [

20] to enhance their local contrast and overall performance under uneven lighting conditions.

For a pixel

x(

i,

j) (where

i and

j denote row and column indices) in a noisy image, its denoised pixel value is obtained by calculating the weighted average of all similar pixels

x(

k,

l) within the search window. The weight

w[(

i,

j),(

k,

l)] depends on the similarity between the two local neighboring blocks, as shown in Equation (1):

Among them,

d[(

i,

j),(

k,

l)] is the Gaussian-weighted Euclidean distance of the two neighboring blocks centered at (

i,

j) and (

k,

l), as shown in Equation (2):

Based on the Gaussian-weighted Euclidean distance, the similarity weight

w[(

i,

j),(

k,

l)] is further quantified by Equation (3) to highlight the weighting of similar pixels:

The key parameters involved in the algorithm are defined in

Table 1:

The obtained pedestrian flow density data can be used as an independent feature as the input of the prediction model, and can also form a multi-feature dataset together with vehicle travel data, weather and environmental information, and the operating status of the power system. In the subsequent integrated power–traffic coupling optimization, the prior pedestrian flow can not only guide the spatial-temporal distribution of charging loads, but also avoid the concentration of power loads in periods with high pedestrian flow density, thereby reducing the peak-valley difference in the entire system and improving related economic benefits.

2.2. Complex Coupling Network for Urban Traffic Flow and Charging

With the increasing proportion of a large number of Electric Vehicles (EVs) in urban traffic systems, the relationship between traffic networks and distribution networks is becoming increasingly intertwined. The movement and charging behaviors of EVs form a tight coupling relationship through changes in traffic flow distribution, charging station utilization rate, and distribution network power flow [

21,

22]. This spatiotemporal integration spans multiple time scales, thus profoundly affecting the operation statuses of both networks and their scheduling strategies.

To describe this complex relationship, this section establishes a complex coupling network model of EV traffic flow and its charging, integrating urban traffic road networks, charging infrastructure networks, and distribution networks into a multi-layer network framework:

2.2.1. Traffic Flow–Charging Demand Mapping

Suppose the traffic flow of road segment

at time

in the traffic layer is

, the proportion of EV in the traffic flow is

, and the average driving energy consumption per unit distance is

. Then, the charging demand power generated by this road segment at time

can be expressed as Equation (4):

This formula represents the basic relationship for deriving charging power demand from traffic flow data. is the simulation time step, and its reciprocal converts energy into average power. Through this mapping, traffic monitoring data can be directly used to estimate the spatial-temporal distribution of charging demand, providing input for cross-layer coupling.

2.2.2. Mapping from Charging Demand to Distribution Network Nodes

At the charging facility level, each charging station

is connected to a specific node

in the distribution network. Assuming that the total charging power of charging station

at time

is

, the charging load of this node is the sum of the powers of all charging stations connected to this node. As shown in Equation (5):

In the above formula, represents the charging stations directly connected to node . The above formula can reflect the superposition effect of multiple charging stations at the same electrical access point and provide input for subsequent power grid power flow analysis and constraints.

2.2.3. Power–Traffic Coupling State Equation

The power balance equation of the distribution grid is specifically manifested as: at time

t, the voltage amplitude

, phase angle

, injected active power

, and injected reactive power

of node i must satisfy the power flow balance condition shown in Equation (6):

where the definitions of each parameter are as follows (see

Table 2):

The above formula is the power flow balance condition of the power system. As shown in Equation (7),the active power

of the node is composed of the base load

and the charging load

:

Finally, in order to quantify the degree of dependence of traffic road segments on EV charging at a certain distribution network node, as shown in Equation (8), the traffic–power coupling coefficient

is introduced:

Among them, represents the EV power demand from road segment and charged at node . The value range of the coupling coefficient is [0, 1], and a larger value indicates a higher degree of dependence.

2.2.4. Building Thermal Energy Storage

In the context of integrated electricity-transportation networks, unforeseen emergencies may occur. In such scenarios, if the number of available electric vehicles (EVs) is insufficient for participation in dispatch, the thermal inertia of buildings can be leveraged for peak shaving and valley filling. This approach helps alleviate transportation dispatch pressure and reduces overall system costs. This subsection proposes an optimized dispatch strategy that incorporates thermal energy storage based on a thermal dynamic model of buildings, aiming to jointly minimize energy supply and transportation costs under emergency conditions.

The potential of building thermal energy storage stems from the thermal inertia of the building envelope and indoor thermal mass. The available thermal storage capacity of a building directly determines its contribution to emergency energy supply. Based on thermodynamic principles, this section establishes a dynamic model of building thermal energy storage:

where the definitions of each parameter are as follows (refer to

Table 3):

In the context of integrated electricity-transportation coupled networks, unexpected emergencies may occur that are difficult to anticipate in advance. If, at the time of such an event, the number of electric vehicles (EVs) is insufficient for participation in dispatch, the thermal inertia of buildings can be utilized for peak shaving and valley filling, thereby alleviating transportation dispatch pressure and reducing overall system costs. This subsection proposes an optimized dispatch strategy that integrates building thermal energy storage, based on a thermal characteristic model of buildings, to jointly minimize energy supply and transportation costs under emergency conditions.

The potential of building thermal energy storage arises from the thermal inertia of the building envelope and indoor thermal mass. The available thermal storage capacity of a building directly determines its contribution to emergency energy supply. Based on thermodynamic principles, a dynamic model of building thermal energy storage is established as follows:

At the onset of a disaster warning, low-cost electricity during grid off-peak periods or waste heat from industrial processes can be used to raise the indoor temperature to the upper limit of the human thermal comfort zone, thereby storing thermal energy for emergency use. During this phase, inexpensive energy sources are leveraged to “charge” the building’s thermal storage, effectively substituting high-cost electricity that would otherwise be required during emergency power supply periods. When a grid failure leads to tight emergency power availability, the stored thermal energy is discharged from the building, reducing the thermal load demand on emergency backup generators and thereby lowering reliance on costly emergency electricity generation.

3. Hypergraph Construction Based on Physical Prior Knowledge

This paper introduces a hypergraph representation method based on physics-informed prior knowledge. Based on multi-layer network modeling, it simultaneously captures the relationships among urban traffic, electric vehicle charging behavior, and distribution network operation. The hyperedge of a hypergraph can directly connect two or more nodes, which makes it possible to describe the collective interaction among multiple nodes more naturally.

Physical priors here mainly refer to structural information from operating principles and constraints, such as power flow equations, thermal limits, and so on. This kind of knowledge not only helps to improve the interpretability of the model, but also greatly reduces the search space of the model, thereby improving prediction accuracy and optimization reliability.

First, define the hypergraph node set including the following three types of nodes:

The first is traffic nodes, which represent key road segment features, including traffic flow , EV penetration rate , pedestrian density , etc.

The second is charging nodes, which represent charging station features, including charging power number of available charging piles, average charging duration, etc.

The last node is power nodes, which represent the physical node features of the distribution network, including node voltage , power injection , remaining capacity, and so on.

When constructing the hypergraph, as shown in Equation (10), the feature vector of each node at time

is expressed as:

In the above formula, F is the feature dimension, and is the -th feature component of node at time .

In an ordinary graph, an edge can only connect two nodes, while a hyperedge can connect a node set at the same time, so as to naturally represent the relationship among multiple nodes. Based on physical prior, we define three types of hyperedges: the first is the power constraint hyperedge, which comprises all power nodes connected to the same transformer or feeder; the second is the traffic–charging association hyperedge, which is a collection of multiple charging station nodes affected by the same traffic corridor; the last one is the pedestrian flow and charging coordination hyperedge, which can reflect the impact of pedestrian flow changes on charging behavior.

For each hyperedge

, as shown in Equation (11), its weight

integrates multiple physical prior-related quantities:

In the right-hand side, are weight coefficients. The first term is the proximity degree of the node set in physical topology, the second term is an index related to capacity constraints, and the last term is the correlation at time of node features representing charging power, pedestrian density, and traffic flow.

To account for the distinct characteristics of power grid nodes, charging stations, and traffic nodes, physical priors are employed to constrain the feasible ranges and temporal evolution characteristics of node features, ensuring that the feature representations adhere to real-world operational constraints:

where the definitions of each parameter are as follows (see

Table 4):

The hyperedge weight directly reflects the strength of coupling among nodes. Each hyperedge weight is derived from physical principles and operational data, as shown in Equation (13), to avoid biases introduced by random initialization:

where the definitions of each parameter are as follows (refer to

Table 5):

Global hypergraph constraints are formulated based on the core physical principles governing the power–transportation coupling, as shown in Equation (14):

The first equation represents the power balance constraint, the second enforces traffic flow conservation, and the third imposes a charging power constraint. Here, denotes the power transmission loss in the grid at time t, and represents the total regional traffic demand at time t.

4. Distributed Solution Strategy of Federated Learning Integrating Multi-Agent

In cross-regional energy transmission systems, data is often distributed across different physical nodes and is constrained by privacy, security, and limited communication bandwidth. Directly sharing raw data poses data security risks and incurs high communication costs.

To solve the above problems, this paper introduces the concept of Federated Learning (FL) and extends the training and solution process of multi-agents into a distributed and privacy-preserving collaborative optimization framework. Each agent only uses its own data locally for strategy optimization and update, without downloading raw data, and only shares local model parameters or gradient information.

First, we formalize the federated multi-agent optimization problem. Suppose there are

agents in the system, and each agent

optimizes its strategy parameter vector

on the local dataset

. As shown in Equation (15), the global objective is:

where

is the local loss function of the

-th agent, and

is the globally unified model parameter. Each agent achieves global collaboration through uniform constraints while keeping data localized.

Then, the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) is used to decompose the global objective problem into parallel local sub-problems and global uniform update steps. The augmented Lagrangian function of the ADMM algorithm is given by Equation (16):

Among them, is the Lagrangian multiplier of the -th agent, and is a penalty parameter used to balance the uniform convergence speed and numerical stability.

Finally, the iteration process of ADMM-FL-multi-agent is carried out, and the iteration process is shown in

Figure 2:

The above figure shows the ADMM-FL-multi-agent collaborative optimization process in this paper. This process initializes with global parameters as the starting point, and each intelligent agent performs independent optimization locally based on its own dataset to avoid centralized raw data transmission.

Each agent

i computes its local gradients

based on its own dataset. To reduce communication overhead, agents exchange compressed updates rather than full gradients. Specifically, each agent performs TopK gradient sparsification, retaining only the TopK elements with the largest absolute values in the local gradient vector:

The global optimization objective, previously described abstractly, is instantiated as follows (Equation (18)):

where

represents the local loss function for agent

i, and

enforces physical constraints such as power flow balance and traffic conservation laws. Here,

λ is a regularization parameter that balances the trade-off between data-driven loss and physical constraint consistency.

To ensure privacy, our federated learning framework adopts (ε, δ)-differential privacy. Gaussian noise

is added to the uploaded gradients before transmission to the server:

where

σ is calibrated to achieve ε = 2.5 under 30 rounds of communication with δ = 10

−5. Our threat model assumes a semi-honest server that follows the protocol but attempts to infer agent-specific raw data from updates. By adding sufficient noise, we prevent reconstruction of raw charging or traffic traces, ensuring robust privacy guarantees.

5. User Responsiveness

To quantitatively measure users’ enthusiasm for participating in the power–transportation coupled network collaborative scheduling, this section constructs a user response rate modeling framework, the user response probability is quantified using the logistic regression function, with the specific formula as follows (Equation (20)):

In the formula, is the feature vector of the -th user, including n-dimensional features such as identity tags, behavior tags, and energy consumption tags, is the feature weight vector, determined through historical data training; is the response improvement coefficient of the incentive measures for the corresponding user, corresponding to the personalized influence factors of the three types of measures, namely material rewards, honor rewards, and feedback incentives; is the weight vector of the incentive measures, reflecting the priority levels of different incentive types.

The structure of the user feature matrix

is as follows:

Among them, represents the number of users, and represents the number of features, including static features such as identity tags and energy consumption tags, as well as dynamic features such as real-time location residence degree, behavior tags, and recent incentive response frequency.

The incentive measure promotion coefficient matrix

is defined as:

where

represents the response promotion coefficient of the

-th user to the

-th type of incentive measure.

represents material rewards (such as coupons, electricity bill discounts);

represents honorary rewards (such as honorary titles) with public recognition;

represents real-time feedback incentives (real-time feedback on reduced energy consumption).

6. Results

6.1. Experimental Setup

The simulation experiments in this study were implemented in Python 3.8 using the PyTorch 1.13.1 framework. The computing environment was a workstation running Windows 11, equipped with an Intel Core i9-13700H processor (base clock 2.40 GHz), 16 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU, which enabled accelerated computations through the CUDA architecture.

6.1.1. Data Collection

All data used to validate the accuracy of the proposed model were collected in a central urban area. The study involved 50 public charging stations and 176 major surrounding road segments. The dataset spanned a two-month period 1 September to 31 October 2022, with a sampling frequency of 10 min intervals. It consists of two primary components: (1) charging station operation data, including charging station utilization rate, average charging duration, and total load at each station, and (2) traffic network data, including real-time speed and flow for each road segment. The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 8:1:1.

6.1.2. Power System Modeling

To simulate the complex impact of loads on the urban circulation network, an integrated simulation environment was established that combines transportation and power systems. The network topology was adopted from the standard IEEE 69-bus test system, as shown in

Figure 3. The 69 nodes were mapped to corresponding urban regions and divided into three functional zones, the numbers (0–69) correspond to the bus indices in the system; the circle dots mark the specific positions of each bus within their respective partitions:

Commercial zone (Nodes 1–27): Characterized by enterprise electricity usage patterns, with higher consumption during daytime and lower usage in the evenings and weekends.

Industrial zone (Nodes 42–56): Defined as a high-load industrial area with consistently high and stable energy consumption during working hours.

Residential zone (Remaining nodes): It exhibits household electricity usage patterns, with two charging peaks in the morning and evening, and relatively stable charging demand throughout the day.

In the proposed framework, the input to the model consists of a multi-modal feature vector for each node at time t, including traffic flow, number of electric vehicles, pedestrian density, charging power, number of charging piles, average charging duration, node voltage, base load, and features from the building thermal model. The model output is the predicted charging load at each distribution network node in the near future. These predictions are subsequently fed into a federated multi-agent optimization model coordinated via ADMM, which jointly enhances prediction accuracy and reduces operational costs while preserving data privacy.

6.2. Baseline Model Comparison

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed prediction model, we conducted comparative experiments with several mainstream spatiotemporal baseline models on the entire test set. The experimental results are presented in

Table 6, where the reported values represent the average performance metrics over all stations and all prediction time steps. The proposed model achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 4.16, which is 39.8% lower than that of STGCN. It also outperformed all other algorithms in terms of RMSE. The MAPE metric exhibited a similar trend, further confirming the stability and accuracy of the predictions.

Traditional spatiotemporal prediction models, such as ST-LSTM and STGCN-BiLSTM, fail to adequately capture sequential correlations in hypergraph structures, thereby limiting their predictive performance. Although STGCN introduces graph convolution to capture spatial dependencies, it still struggles with the complex interactions between traffic flows and load coupling. In contrast, the proposed model leverages hypergraph-based information diffusion and multi-level feature fusion mechanisms, enabling it to more effectively capture system complexity.

To further verify the applicability and reliability of the proposed model under various conditions, combined scenarios of EV penetration levels and traffic patterns were constructed. EV penetration rates were set to 10%, 30%, 50%, and 70% to simulate different adoption stages, while traffic patterns reflected real-world variations, including normal days, enhanced morning and evening peak periods, and holiday scenarios.

6.3. Optimization Results

In this section, charging load scheduling is validated based on the IEEE 69-bus topology. The procedure is as follows: the baseline power grid model is first constructed by importing the base loads and line parameters into a power flow solver according to their original node indices. Then, according to charging demand, the total charging energy is allocated across the 69 nodes in proportion to their base loads or node importance. Nodes with the highest EV penetration rates are selected for simulation.

The optimization results of the power–transportation coupled network are shown in

Figure 4. The blue solid line represents the charging load without smoothing, where charging demand is allocated solely based on instantaneous EV requirements, without considering grid peak–valley differences or overall load balancing. Consequently, significant fluctuations occur at different time periods.

Before optimization, the peak–valley difference was 4901.12 kW, which decreased to 3913.16 kW after optimization, representing a reduction of 987.96 kW, or approximately 20.16%. This substantial reduction indicates a smoother load curve and a more balanced power grid load distribution. By redistributing charging loads, the model effectively suppressed peak load growth, resulting in a smoother overall curve and ensuring the stable operation of the distribution network.

As shown in

Figure 5, the optimization measures also reduced the total operating cost of the network by approximately 25%, indicating improvements in both grid stability and economic efficiency.

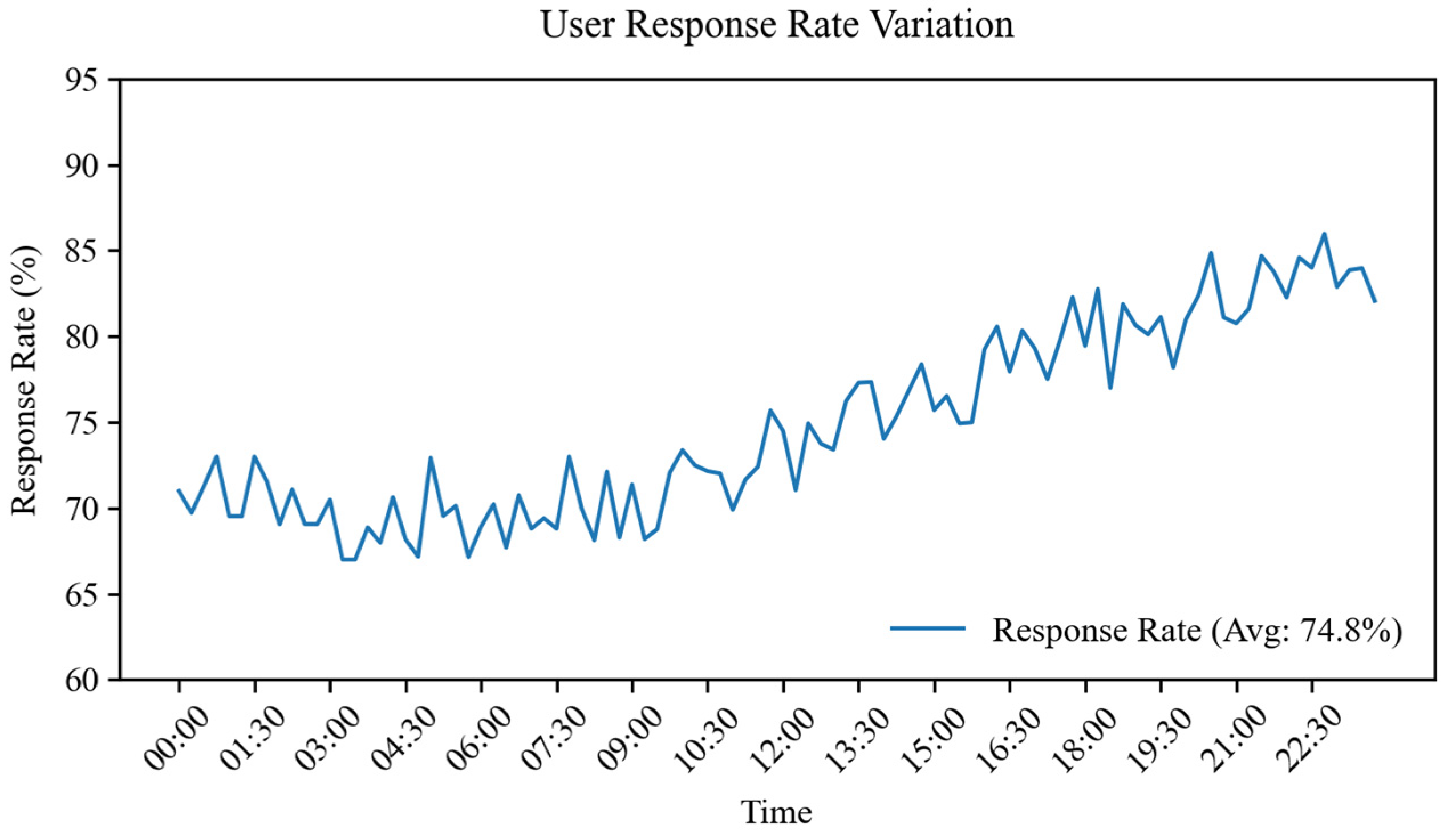

Figure 6 illustrates the temporal variation in user response rates in the proposed collaborative scheduling system. The consistently high response rate (>80%) during the daytime facilitates more predictable load shifting, allowing grid operators to optimize resource allocation, reduce peak demand, and enhance overall system efficiency.

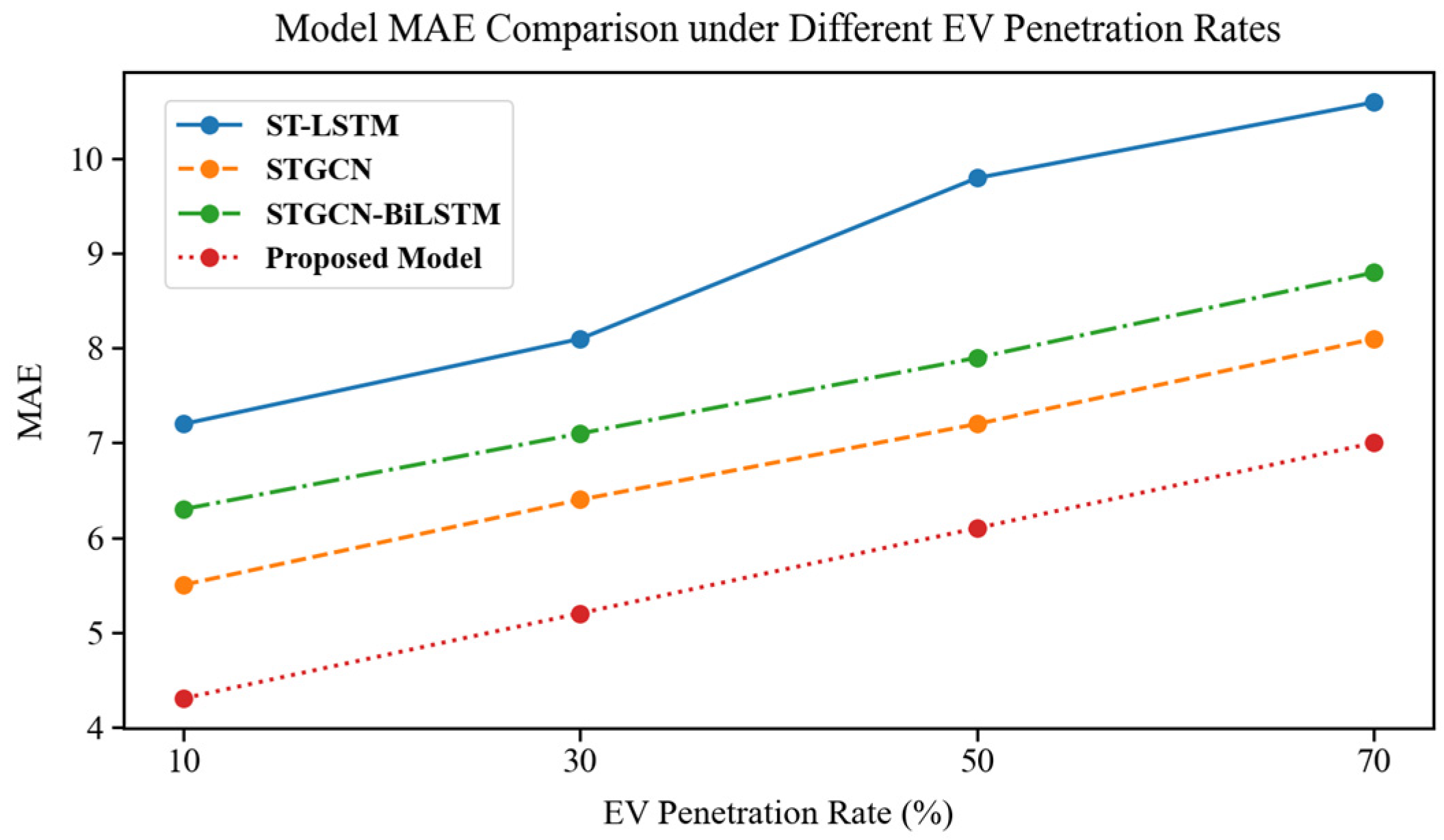

Furthermore, combined scenarios of EV penetration and traffic patterns were constructed to characterize the impact of EV adoption stages on charging demand. EV penetration rates were set to 10%, 30%, 50%, and 70%.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present comparisons of MAE and loss values under different EV penetration levels. As EV penetration increases from 10% to 70%, prediction errors for all models increase, reflecting the challenge posed by increased load demand fluctuations under higher EV adoption. However, the proposed model consistently achieved the optimal performance across all penetration levels, particularly in high-penetration scenarios, demonstrating strong robustness and adaptability.

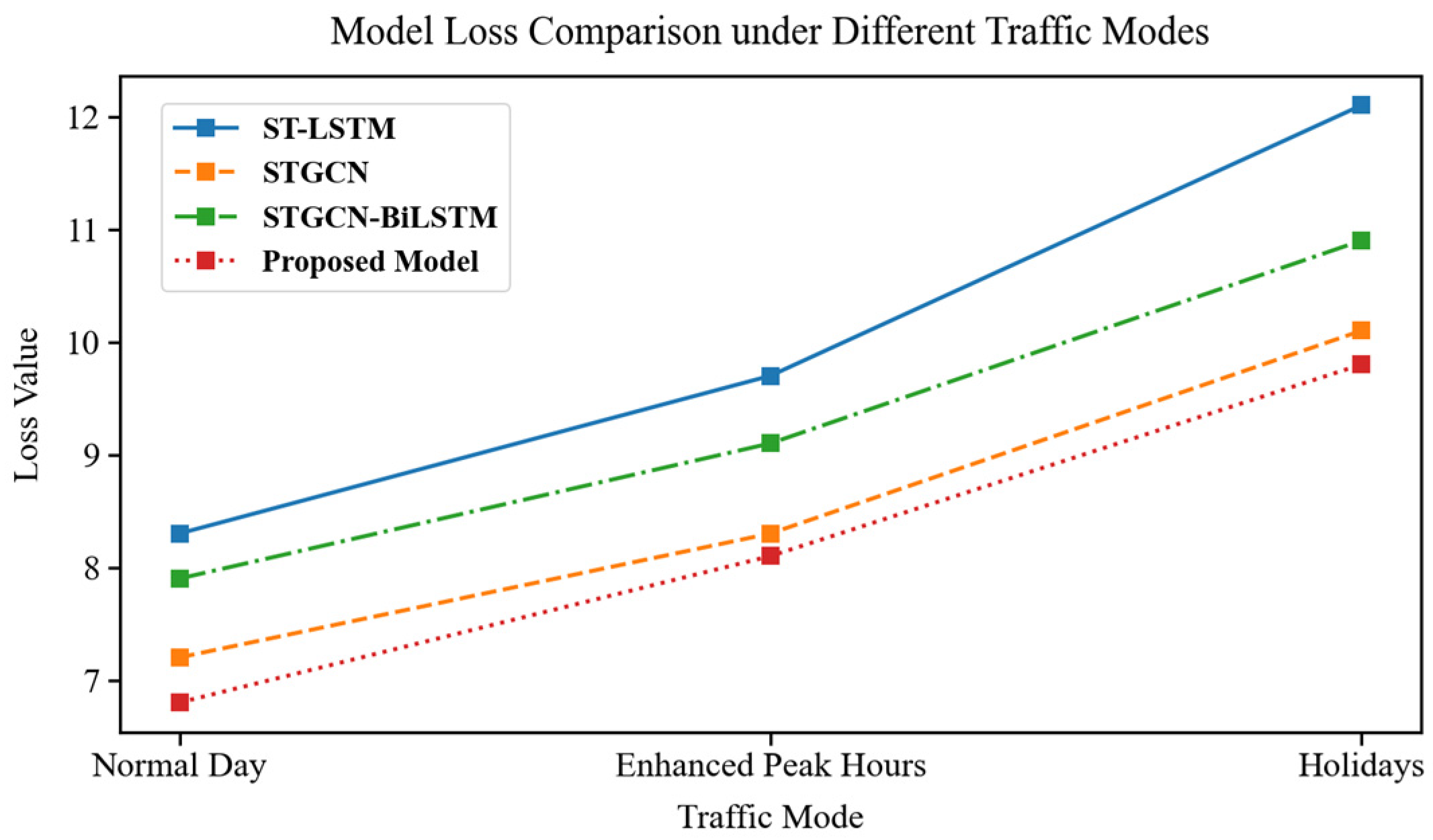

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 compare the MAE and loss values of each model under different traffic modes. It can be observed that prediction accuracy is highest under normal traffic conditions, decreases during peak-hour traffic periods, and is lowest during holiday traffic scenarios. Overall, the proposed model achieved the lowest MAE values across all three cases, further validating its adaptability and stability in addressing variations in spatiotemporal characteristics under different scenarios.

6.4. Effects of Communication Delay

To validate the robustness and practicality of the proposed ADMM-FL hierarchical multi-agent framework under real-world network communication uncertainties, this section conducts experimental analyses considering communication delays and presents the implementation details and observed results.

The system was divided into M = 10 agents, with each agent corresponding to a subset of data from several charging stations and adjacent road segments. Each agent trained its model locally and exchanged parameters and gradients with a central coordination server. The maximum number of global training rounds was set to 200, with one epoch per local training round, a batch size of 32, and a learning rate of lr = 1 × 10−3. Early stopping was applied when the validation MAE no longer decreased.

As shown in

Figure 11, communication delays were injected into the training process to simulate combined uplink and downlink delays. Three typical delay scenarios were configured: low delay (10 ms), medium delay (50 ms), and high delay (200 ms). Each round of parameter aggregation included the sum of uplink and downlink delays. To map the millisecond-level delays in simulation to the minute-level timescale of real-world energy scheduling and load forecasting processes, a conversion factor was introduced as shown in Equation (23):

Among them, is the communication delay in the simulation, is the corresponding actual equivalent scheduling time, and α is a scene-related proportional factor. The exactly same ADMM-FL algorithm is run under each delay scenario, with the local training epoch per round being 20, the batch size being 32, and the upper limit of the maximum global rounds set to 200.

Table 7 lists the comparison results of specific experimental indicators. In the communication delay sensitivity experiment, it is observed that as the one-way delay increases from 10 ms to 200 ms, the number of convergence rounds increases from 100 to 118. The reason is that each round of synchronous aggregation needs to wait for all agents to complete parameter reporting and server parameter broadcasting. The increase in delay will prolong the synchronization time of each round, resulting in a corresponding increase in the number of global rounds required to achieve convergence, which is more obvious under a strict synchronization mechanism. At the same time, the total training time increases approximately linearly with the delay. In the case of 50 ms, the total time increases by about 10%, and in the case of 200 ms, it increases by about 18%. The growth stems from both the direct time cost increase caused by the single-round delay and the indirect communication overhead caused by the increased number of convergence rounds. Therefore, the training time growth in high-delay scenarios shows a dual cumulative effect; however, the impact of delay on the final model performance is relatively small. The MAE in the 50 ms and 200 ms scenarios increases by only about 1.0% and 2.7%, respectively. This data shows that the ADMM-FL framework has good robustness to communication delays. The reason is that the ADMM-FL mechanism allows strong local updates and buffer of dual variables, and the impact of short-term parameters on the approximation of the global solution is limited. Therefore, the overall reduction in model accuracy is small.

7. Algorithm Extension and Application

As a typical scenario characterized by highly concentrated electricity–transportation–charging coupling, smart parks have a strong demand for coordinated optimization among their internal distribution networks, traffic road networks, and charging infrastructure. This requirement aligns closely with the core design of the proposed “physics-informed hypergraph + federated multi-agent” algorithm. To validate the algorithm’s capability in supporting smart park operations, this section quantifies the algorithm-park optimization matching degree and analyzes the adaptation mechanisms, thereby demonstrating the strong applicability of the proposed approach to park-level optimization and providing technical support for the refined operation of smart parks.

This study proposes an advanced AI assessment system based on a multi-layer neural network architecture. By integrating deep reinforcement learning, graph neural networks, variational autoencoders, and Bayesian neural networks, we form a comprehensive assessment framework with learning, prediction, optimization, and interpretability capabilities. At the feature level, multi-modal feature embedding vectors are defined as follows (Equation (24)):

Among them, the temporal feature

ftime is based on the Fourier transform coefficients of the 24 h load curve; the meteorological feature

fweather includes the probability distribution of solar irradiance and temperature correction factors; the geographical feature

fgeo represents the latitude and longitude optimization coefficients and shadow occlusion model; and the economic feature

feco consists of time-of-use electricity price elasticity coefficients and demand response potential. At the evaluation engine level, the park energy system is modeled as a dynamic graph structure, and the evaluation function is defined as Equation (25):

Among them,

represents node features, and

represents edge weights. A graph convolutional network with a three-layer attention mechanism is employed to output a six-dimensional evaluation vector. Based on this, six key evaluation indicators are constructed. The first indicator is the PV Synergy Index. By using a spatiotemporal graph convolutional network and combining solar trajectory, cloud prediction, and LSTM load prediction, it is modeled via a dynamic function (Equation (26)):

The second is the Storage Optimization Index. The energy storage dispatch is optimized using the Deep Q-Network (DQN). The state space is defined as

, the action space is

, and the reward function is:

The third is the Load Balance Index. The variational autoencoder (VAE) is used to realize the reconstruction of the optimal load curve, and its balance degree is expressed as:

The fourth is the Multi-Agent Synergy Index. The Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) method is employed, where each park serves as an independent agent, and the synergy score is defined as:

The fifth is the Economic Benefit Index. The investment timing is optimized using deep reinforcement learning and Monte Carlo tree search, and the value function is:

where

is the discount factor. The sixth is the Technical Feasibility Index. Bayesian neural networks are employed for uncertainty quantification, and the technical reliability and feasibility are defined as:

In terms of the overall architecture, the system is based on a Transformer fusion model and further incorporates advanced features such as adaptive learning, uncertainty quantification, causal reasoning, and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). This system is not only an evaluation tool but also a digital twin with the characteristics of an intelligent adaptive entity, capable of realizing predictive maintenance, autonomous optimization, and continuous evolution.

Figure 12 shows the AI-based intelligent identification system interface for park compatibility assessment. Empirical evaluations demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves a matching degree of over 80% with the optimization demands of smart parks. It demonstrates strong adaptability and short adaptation periods in scenarios such as charging scheduling and privacy-preserving collaborative scheduling. The algorithm not only retains its performance advantages in large-scale electricity–transportation coupled networks but also, through scenario-specific parameter tuning, effectively responds to the demands of refined park operations and enables energy optimization—demonstrating its broad applicability and flexible deployment capability.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes a unified modeling and distributed solution framework integrating multi-modal data with physics-informed priors to address the challenges of collaborative optimization in power–transportation coupled networks under the dual-carbon goals and smart city development. The main conclusions are as follows:

First, the proposed multi-modal data-driven modeling approach effectively captures intrinsic correlations among heterogeneous elements. By fusing traffic flow, pedestrian density, charging behavior, grid operating states, and building thermal energy storage characteristics, it establishes a comprehensive feature foundation for subsequent joint modeling. The real-time pedestrian flow detection algorithm further enhances data reliability in complex environments.

Second, the physics-informed hypergraph modeling significantly improves model interpretability and reliability. Embedding physical principles—such as power flow balance, traffic flow conservation, and charging power constraints—into node-level and global constraints avoids the limitations of purely data-driven approaches and accurately characterizes the interdependencies among transportation, charging, and power systems.

Third, the hierarchical multi-agent collaborative strategy combining federated learning and ADMM achieves a balanced trade-off between cost reduction, privacy preservation, and computational efficiency. The distributed architecture ensures local retention of raw data and reduces communication overhead, while gradient sparsification and differential privacy ensure robust data privacy protection. Experimental results show that this strategy reduces the peak-to-valley load gap by 20.16% and lowers system operating costs by approximately 25%, demonstrating robustness to communication delays.

Fourth, the proposed framework exhibits broad applicability and scalability. In charging load forecasting, it outperforms mainstream baselines—e.g., achieving a 39.8% lower MAE than STGCN (and slightly better than ST-LSTM)—and maintains superior performance across varying EV penetration levels (10–70%) and traffic scenarios. Moreover, its matching degree with smart park optimization requirements exceeds 80%, providing effective technical support for precise energy management in such settings.

Fifth, user responsiveness modeling enriches the framework’s practical value. Using logistic regression, we quantify users’ participation probability in scheduling by integrating user attribute features and sensitivity to incentive mechanisms, thereby establishing a data-driven basis for optimizing incentive strategies and ensuring real-world feasibility.

Overall, this study achieves a deep integration of data-driven learning and physics-based modeling, offering a viable technical pathway for the safe, efficient, and low-carbon operation of power–transportation integrated networks. In the future, the framework can be extended to incorporate hydrogen and geothermal energy systems, further enhancing system security and economic efficiency to better support China’s “dual-carbon” strategy and smart city development.