Abstract

Multi-modal entity alignment (MMEA) identifies identical real-world entities across two multi-modal knowledge graphs. Most existing methods heavily rely on costly manually labeled seed alignments; in response, self-supervised MMEA has emerged to reduce this dependency. However, current self-supervised approaches suffer from two key issues: (1) low-quality pseudo-labels (sparse and noisy) weakening self-supervised signals; and (2) inter-modal semantic inconsistencies (structure, text, vision) hindering unified entity representations. To resolve these issues, we propose OPICE, an Ontology-guided Pseudo-label Generation and Inter-modal Consistency Enhancement for self-supervised MMEA. It adopts a robust pseudo-label generation strategy to produce more initial alignments with less noise, and it uses an inter-modal consistency enhancement module to narrow inter-modal semantic gaps for unified representations. Experiments on FB–DB15K and FB–YAGO15K show that OPICE achieves state-of-the-art performance, improving Hit@1 by 6.8% on average over the strongest self-supervised baseline and being competitive with most supervised baselines under standard reported settings.

1. Introduction

In recent years, multi-modal knowledge graphs (MMKGs) such as DBpedia and YAGO [1,2] have become an indispensable resource for a wide range of intelligent applications, such as question answering [3,4], recommendation systems [5,6,7], and domain-specific applications [8,9]. Multi-modal entity alignment (MMEA) seeks to discover correspondences between entities that represent the same real-world object across MMKGs, where each entity is described through multiple modalities such as structure, relations, images, and attributes [10,11,12]. By jointly integrating these heterogeneous sources of information, MMEA plays a crucial role in enabling knowledge integration across knowledge graphs, which is essential for intelligent applications downstream. However, most existing approaches for MMEA operate under supervised settings [13,14,15]. These methods heavily rely on a large number of manually annotated aligned entity pairs, the acquisition of which is expensive, time-consuming, and domain-dependent. Such reliance severely limits their scalability and applicability in real-world scenarios where labeled alignments are scarce or unavailable.

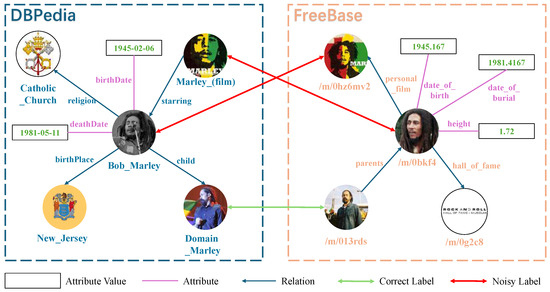

To reduce reliance on manually annotated aligned entity pairs, some prior works have explored self-supervised or unsupervised MMEA approaches, such as using pseudo-labels [16], bootstrapping [17], or contrastive learning to automatically mine alignment signals [18]. Another line of work leverages pre-trained large language models (LLMs) to compare textual descriptions of entities [19,20,21,22]. Although these methods have achieved progress in reducing human effort, they still suffer from two limitations: (i) Insufficient quantity and low quality of pseudo-labels. Current self-supervised approaches often produce a limited number of pseudo-aligned pairs, and many of them are noisy or unreliable. Indeed, the impact of noise on pseudo-labels is particularly severe, as it not only provides erroneous supervisory signals to the model but also prevents potentially alignable pairs from being correctly matched. As illustrated in Figure 1, if pseudo-label generation relies solely on images—as in the Entity Visual Alignment (EVA) approach [16], a self-supervised entity alignment method that generates pseudo-labels merely by leveraging visual vector similarity to construct initial seed dictionaries (visual pivots)—it may erroneously align entities such as “Bob_Marley” from DBPedia with the movie “/m/0hz6mv2” from FreeBase, thereby introducing noise. Simultaneously, this approach could result in the failure to align valid entity pairs such as “Bob_Marley—/m/0bkf4” and “Marley_(film)—/m/0hz6mv2”. (ii) Weak inter-modal semantic consistency. Inter-modal semantic inconsistencies occur when different modality-specific features, such as visual features and relational semantics, make it difficult to learn a unified entity representation. As shown in Figure 1, the entity “Bob_Marley” possesses the attributes “birthDate” and the relation “child”, yet its associated image does not contain visual cues overlapping with these textual or relational semantics. This weak inter-modal correlation makes it difficult to capture shared characteristics across modalities for effective cross-modal enhancement.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the two key challenges in self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment: low-quality (noisy) pseudo-labels that mislead supervision and weak inter-modal semantic consistency that limits effective multi-modal fusion.

To tackle the aforementioned challenges and design a more effective self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment (MMEA) model, we propose OPICE, a self-supervised MMEA framework for Ontology-guided Pseudo-label Generation and Inter-modal Consistency Enhancement. OPICE, which aims to improve existing self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment methods by addressing their two major limitations, integrates multi-modal knowledge through three key components: (1) a multi-modal knowledge embedding module, (2) a pseudo-label generation module, and (3) an inter-modal consistency enhancement module. Specifically, the multi-modal knowledge embedding module first encodes entities from multiple modalities—including structural, textual, and visual information—into a unified embedding space. By constructing comprehensive multi-modal embeddings, this module provides a rich feature basis for subsequent pseudo-label generation and inter-modal consistency learning. To mitigate the scarcity and noise of manually annotated alignments in self-supervised MMEA, the ontology-based pseudo-label generation module leverages ontologies—structured representations of knowledge that define entity types, their attributes, and the relationships among them. Specifically, ontology alignment is performed through attribute matching to establish correspondences between different ontologies, producing aligned subsets of entities. Then, by further evaluating visual similarity among entities within these subsets, the module generates high-confidence pseudo-aligned pairs that serve as supervision signals for subsequent training. In addition, inspired by [23], we introduce an Inter-modal Consistency Enhancement (ICE) strategy to address the weak semantic associations between modalities. Specifically, we employ a cross-attention mechanism to capture semantic associations among multiple modalities, thereby emphasizing their shared representations. To further enhance inter-modal consistency, we introduce an orthogonal loss, which is computed as the difference between the original feature and its shared counterpart extracted from cross-modal attention. Minimizing this loss effectively reduces the discrepancy among modalities and promotes the learning of unified and consistent entity representations. Addressing the above challenges is crucial for advancing self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment. Improving the quality and quantity of pseudo-labels can significantly enhance the reliability of self-supervised learning. Moreover, strengthening inter-modal semantic consistency enables more robust multi-modal fusion and facilitates scalable alignment without relying on manually labeled seed pairs. These improvements are essential for practical and large-scale KG applications. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We systematically identify the key challenges in self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment (MMEA), including the difficulty of generating high-quality pseudo-labels and the weak semantic associations across different modalities.

- We propose OPICE, a novel self-supervised MMEA framework that introduces a pseudo-label generation strategy and an inter-modal consistency enhancement mechanism to jointly improve alignment quantity, robustness, and cross-modal coherence.

- We conduct extensive experiments on two widely used multi-modal datasets, FB–DB15K and FB–YAGO15K, demonstrating that OPICE consistently outperforms existing self-supervised methods and even surpasses most supervised baselines.

2. Related Work

In this section, we categorize prior studies into two primary research directions: multi-modal entity alignment and semi-/self-supervised entity alignment.

2.1. Multi-Modal Entity Alignment

Since the introduction of the multi-modal knowledge graph task by Liu et al. [10], the incorporation of visual information into entity alignment has become an increasingly active area of research, driven by the rise of multi-modal learning. MMEA [13] independently encodes visual, relational, and numerical features of entities and subsequently combines them through a fusion mechanism. MEAformer [14] introduces a multi-modal Transformer architecture that dynamically models inter-modal correlations, enabling fine-grained entity-level modality fusion. MSNEA [15] proposes a modality interaction framework in which visual features inform both relational learning and attribute selection, complemented by a multi-modal contrastive objective that encourages the embeddings of aligned entities to converge. GSIEA [24] mitigates graph-structure heterogeneity by injecting structural keys/values as prefixes into cross-modal attention and equips the Transformer feed-forward network with a convolutional enhancement module to extract fine-grained local features, achieving robust joint embeddings under structural variations and modality-specific noise. OTMEA [25] casts multi-modal entity alignment as a Wasserstein-distance minimization problem, using optimal transport to align each modality’s distribution with the structural distribution before fusing the distributions with entity-level attention, thereby explicitly reducing heterogeneity among modalities. CDMEA [26] introduces a causal debiasing framework that estimates and subtracts the natural direct effect of the visual modality from the total effect, forcing the model to exploit the total indirect effect and thus suppressing visual shortcut bias while preserving beneficial cross-modal information. Although these methods have achieved promising results, their performance heavily relies on supervised signals, which limits their applicability in real-world scenarios with limited supervision.

2.2. Semi-Supervised and Self-Supervised Entity Alignment

In recent years, representation learning-based entity alignment methods have achieved impressive results and attracted considerable attention. However, their performance heavily relies on manually annotated data and degrades significantly under low-resource scenarios, which has motivated the development of semi-supervised and self-supervised approaches. Semi-supervised methods typically rely on a small set of seed alignments and expand them by generating pseudo-labels; for example, BootEA [17] iteratively labels potential aligned pairs, and PCMEA [18] integrates both supervised and self-supervised information through pseudo-label calibration. In contrast, self-supervised methods do not assume the availability of any pre-aligned entity pairs; instead, they construct supervision signals from the intrinsic structures or multi-modal information within KGs. For example, EVA [16] leverages visual similarity to generate pre-aligned pairs in cross-lingual settings. However, these methods still suffer from issues such as low-quality pseudo-labels, accumulated noise, and weak inter-modal consistency.

3. Methodology

In this section, we first present the problem definition of multi-modal entity alignment and provide an overview of our proposed OPICE model, which aims to align entities from two multi-modal knowledge graphs without the need for manual labels. Subsequently, we elaborate on the technical details of the three major modules within OPICE.

3.1. Problem Definition

Multi-modal Knowledge Graph (MMKG). A MMKG consists of relational, attribute, visual, and structural knowledge and is denoted as . In this notation, E, R, I, A, and V correspond to the sets of entities, relations, images, attributes, and attribute values, respectively. The set of relational triples is defined as , where h denotes the head entity, t denotes the tail entity, and r represents the relation linking them.

Self-supervised Multi-modal Knowledge Entity Alignment. Take two MMKGs, and . In this work, P does not refer to manually annotated pre-aligned entity pairs. Instead, we define as the set of pseudo-aligned entity pairs that are discovered during training, where ≡ denotes the equivalence relation inferred by the model. The goal of MMEA is to identify all aligned entity pairs , with and , corresponding to the same real-world entity . Since manually annotated alignments are typically expensive and extremely limited in real-world knowledge graphs, we conduct the alignment task in a self-supervised setting, in which no ground-truth pre-aligned entity pairs are available initially; instead, pseudo-labels in P are automatically generated and refined throughout the training process.

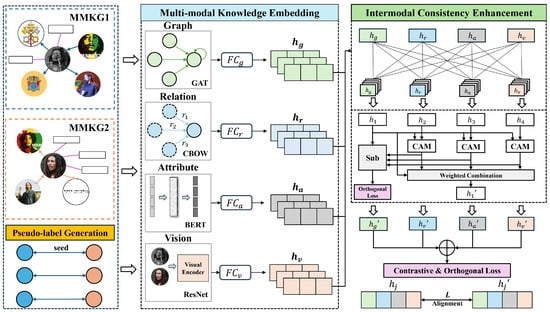

3.2. Framework Overview

To address the above challenges, we propose OPICE, whose overall architecture is shown in Figure 2. OPICE is a self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment framework composed of three sequential modules: (i) Multi-modal knowledge embedding. This module serves as the feature foundation of the framework, tasked with extracting high-quality, discriminative features from the diverse data modalities inherent in MMKGs. Specifically, it leverages modality-specific encoders to capture visual, attribute, relational, and structural features. (ii) Pseudo-label generation. This module is designed as an auxiliary component. It leverages the feature representations learned by the multi-modal knowledge embedding module to generate pseudo-labels, which are used as part of the model input to guide the training process. This module introduces the concept of ontology alignment for the first time and then performs fine-grained entity alignment based on the ontology alignment to generate reliable pseudo-labels. (iii) Inter-modal consistency enhancement. Considering that the embeddings produced by the multi-modal knowledge embedding module may exhibit weak semantic correlations among different modalities, this module enhances inter-modal consistency by introducing a cross-modal attention mechanism and an orthogonality constraint loss.

Figure 2.

Overview of the framework of OPICE. OPICE is composed of three sequential modules: multi-modal knowledge encoding, ontology-guided pseudo-label generation, and inter-modal consistency enhancement.

3.3. Multi-Modal Knowledge Embedding

In this section, we detail how the features of each entity modality are projected into low-dimensional vector spaces.

3.3.1. Graph Structure Embeddings

To model the structural similarities of G and G’, we employ a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to capture the structural information, since GAT aggregates neighbor information and focuses on the most relevant neighbors through an attention mechanism. In practice, we apply a two-layer GAT model with two attention heads to obtain the structural embeddings.

To further enhance the representation of structural embeddings, we introduce a self-attention mechanism with a lightweight adapter network (AdaptorMLP) after the GAT encoder. The self-attention mechanism is capable of modeling the global dependencies between nodes, complementing the limitations of GAT in local neighborhood modeling, and thus capturing potential alignment information between distant nodes. Adaptor-MLP further adjusts and maps the embedding space, which helps to mitigate the distributional differences between different modalities or graphs and improves the consistency and alignability of embedding representation. The processes of graph embedding, , are formulated as:

where W is a learnable parameter, denotes the input features of node i, represents the attention weight, is the learnable parameter of the attention mechanism, indicates the collection of nodes adjacent to node i, and stands for a non-linear activation function.

3.3.2. Relation Embeddings

GAT primarily models the structure of connections between entities (adjacencies) rather than the semantic information of the relationships themselves. Accordingly, we adopt the strategy of Yang et al. [27], representing entity relationships as bag-of-words features and passing them through a basic feed-forward layer to derive relation embeddings. The relation embeddings are calculated as

where and are learnable parameters.

3.3.3. Attribute Embeddings

In knowledge graphs, the attributes of corresponding entities have similar characteristics or semantics. We denominate the attribute as a sequence of words s and feed s into a pre-trained language model that understands the meaning of the word sequence. We use BERT [28] to encode the attribute names, and after a feed-forward layer, we can obtain an embedded representation of the attribute modality:

where and are learnable parameters.

3.3.4. Visual Information Embeddings

The key distinction between multi-modal and traditional knowledge graphs lies in the inclusion of visual modalities for entities. Following Figure 2, “Visual Encoder”, we adopt a pre-trained visual network (ResNet-50 [29]) to extract entity visual embeddings. The image is processed by the model, and the activation from its last layer before the logits is used as the feature vector. This vector is subsequently fed into a feed-forward network to generate the corresponding visual embedding,

where is the image of the entity , while and are learnable parameters.

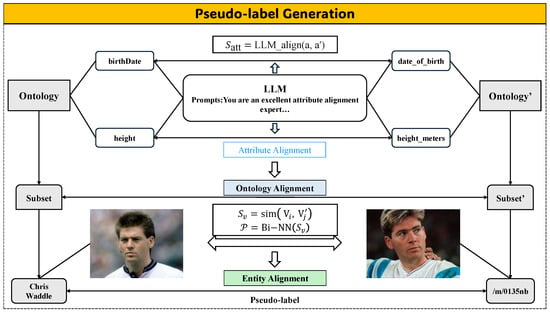

3.4. Pseudo-Label Generation

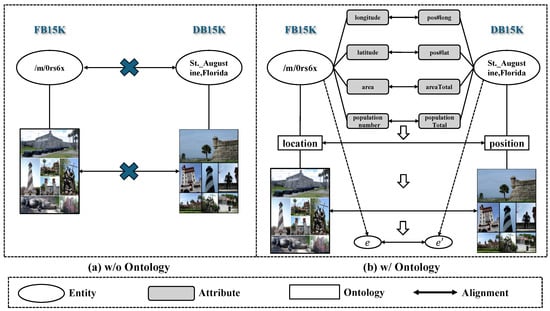

In this section, a pseudo-label generation strategy is designed for self-supervised EA. As shown in Figure 3, the pseudo-label generation mechanism consists mainly of two modules: (1) ontology alignment provides aligned ontology pairs for the pseudo-label generation phase; (2) visual-similarity-based pseudo-label generation is based on ontology alignment, which generates high-quality pre-aligned entity pairs from aligned ontology pairs using visual similarity.

Figure 3.

The framework for pseudo-label generating. The process consists of three stages: (1) Attribute alignment, where the LLM (e.g., GPT or DeepSeek) computes the attribute similarity score; (2) Ontology alignment, which integrates aligned attributes to refine the search space of potential entity pairs; and (3) Entity alignment, where visual similarity is calculated and the Bi-NN method identifies mutually optimal pairs as pseudo-labels.

3.4.1. Attribute Alignment

Recently, the powerful semantic understanding capabilities of large language models (LLMs) have been demonstrated across a wide range of tasks [30,31]. As attributes are an important form of semantic information about entities, we posit that entities having the same attributes are likely to belong to the same ontology, with this likelihood increasing the more attributes they share. To achieve cross-graph attribute alignment, we constructed a unified attribute set A, which contains all attributes of the source and target graphs. Subsequently, we designed refined few-shot prompts to stimulate deep understanding of attribute semantics in the LLM. All attribute alignment results reported in this paper were generated using GPT-4 in our implementation. As shown in Table 1, only the attribute names are provided to the model to perform one-to-one matching; no additional descriptive context or exemplar demonstrations are supplied. The aligned attribute set can be defined as

Table 1.

The prompt used in attribute alignment.

3.4.2. Ontology Alignment

Given an attribute set A, we identify subsets of entities S that share at least n alignment attributes (where ) across the source and target knowledge graphs. This criterion is adopted to enhance the structural consistency of candidate entity subsets at the ontological level. We hypothesize that a greater number of shared alignment attributes within an entity subset generally reflects a higher degree of ontological correspondence at the semantic level.

Based on what was mentioned above, the corresponding subsets of entities and are extracted from the knowledge graphs and , respectively. When the entities in and share an identical set of attributes and these common attributes can be consistently aligned based on the results from the initial attribute alignment phase, it can be further inferred that the entities in and are ontologically aligned.

To validate the accuracy of the ontology alignment results, we conducted a statistical evaluation: we randomly sampled subsets accounting for 90% of the total subset count from FB15K, DB15K, and YAGO15K, respectively. The evaluation results show that the probability that all entities in each sampled subset belong to the same ontology exceeds 99.2%. This confirms that entities within each qualified subset semantically belong to the same ontological category. Based on this observation, it becomes feasible to perform more fine-grained entity-level alignment within these subsets, grounded on the established ontology alignment.

3.4.3. Entity Alignment

By leveraging ontology alignment, we effectively narrow the search space for pre-aligned entity pairs and reduce the complexity of candidate selection. On this basis, we employ a Bidirectional Nearest Neighbor (Bi-NN) strategy to perform fine-grained alignment within the ontology-aligned entity subsets. Specifically, we first compute the visual similarity among all entities in the aligned subsets. For any entity from one graph and from another, if is the top visual match of and is the top-1 visual match of , the pair is regarded as a Bi-NN aligned pseudo-pair. The computation process is formulated as follows:

where denotes the visual similarity score matrix between entity and , and represent the visual feature embeddings of entities from the two multi-modal knowledge graphs, refers to the similarity function, and the set represents the pseudo-aligned pairs selected through the Bi-NN (Bidirectional Nearest Neighbor) strategy.

3.5. Inter-Modal Consistency Enhancement

In multi-modal tasks, semantic correlations across different modalities are typically leveraged to enable complementary and enhanced feature representations. However, when the semantic association between modalities is weak, interaction mechanisms designed to fuse modal features may introduce noise or conflicting information, potentially degrading overall performance and even leading to results inferior to those of unimodal approaches.

To address this issue, we use a cross-modal consistency enhancement mechanism based on orthogonality-constrained cross-attention, which aims to strengthen semantic consistency across modalities and facilitate a more comprehensive and accurate representation of entities. Specifically, we consider two distinct modality features, denoted as and . In the cross-modal attention mechanism, is designated as the query, while serves as both the key and value. Attentional mechanisms can highlight parts of that are semantically closer to while refining and enhancing the representation of and preserving the consistency between and . The formula for the multi-head attention mechanism is defined as follows:

where and represent the embedding of modality m and modality n, is the number of attention heads, are mapping matrices of the ith attention head, and are the projection matrix and bias.

Leveraging a cross-modal cross-attention mechanism, we extract shared semantic representations across the four modalities—structure, attribute, relation, and vision—and enhance inter-modal semantic associations accordingly:

where are learnable parameters, stands for the result of the multi-head attention mechanism, and represents the consistency-enhanced version of the embedding of modality m.

Next, given an entity e and its structural, relational, visual, and attribute feature embeddings , and , we conduct a simple weighted concatenation by integrating multi-modal features into a joint representation :

where ⨁ represents concatenation operations, , and denotes the trainable attention weight corresponding to modality m.

To enhance the extraction of common features, we additionally introduce an orthogonal constraint loss that forces the residual vector to be orthogonal to the query features. In our embedding space, vectors are approximately normalized, and so cosine similarity serves as the primary indicator of semantic relevance. When two vectors are orthogonal, their cosine similarity approaches zero, meaning that their information is not correlated. Therefore, enforcing orthogonality ensures that the residual contains only modality-specific or non-shared semantics, rather than duplicating the common semantics already represented in the query features. Specifically, denotes the refined representation of that captures the features highly relevant to . The residual, computed as , represents the components of that are not associated with . As such, this residual is expected to be orthogonal to in the semantic space. Accordingly, the orthogonal constraint loss is defined as follows:

where is the orthogonal constraint function; represents the residual between the original representations and the query representations; and is orthogonal loss, which emphasizes the commonalities to extract the correspondence between modalities.

3.6. Optimization Objective

Previous work has shown that contrastive learning is effective for entity alignment tasks. To enhance the effectiveness of representation learning, we take the Intra-modal Contrastive Loss (ICL) and Inter-modal Alignment Loss (IAL), introduced in Lin et al. [32], and incorporate then into OPICE. Specifically, under the commonly assumed one-to-one alignment setting, aligned seed pairs naturally serve as positive samples, whereas unaligned entity pairs can be treated as negative samples, thereby providing a clear supervision signal for contrastive learning objectives. Formally, let the ith entity within a minibatch B have a positive set defined as , where . The negative set is composed of two components, originating from G and , respectively, and can be expressed as and . Both and come from minibatch B. The alignment probability is defined as

where , is the encoder of modality m, while is the temperature parameter. Based on this, we can calculate the intra-modal contrastive loss:

For clarity, we emphasize that the joint-embedding contrastive loss follows the same mathematical form as Equation (18). The only distinction is that the unimodal embedding is replaced by the joint embedding vector , which fuses multi-modal information. In intra-modal contrastive learning (ICL), modeling complex interactions between different modalities remains challenging, as modality-specific embeddings are typically learned in isolation. Additionally, the pseudo-labels employed in training may contain a certain degree of noise, given their heuristic or artificial generation. To address these limitations, we introduce an inter-modal alignment loss (IAL) function to explicitly encourage cross-modal consistency, alongside a momentum-based contrastive loss function designed to enhance the robustness and stability of representation learning.

For inter-modal alignment loss (IAL), we transfer the knowledge from the joint embedding space back to the unimodal embeddings, enabling each unimodal representation to better exploit the complementary information provided by other modalities. Specifically, we minimize the bidirectional Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the output distributions of the joint and unimodal embeddings. The IAL is defined as

where and represent the output predictions of joint embedding and the unimodal embedding of modality m, respectively.

Motivated by momentum-based contrastive learning (MOCO) [33]—a framework leveraging a momentum update strategy that mitigates gradient noise, facilitates smoother optimization dynamics, and ensures more stable convergence, making it highly suitable for noisy scenarios—we update the online encoder’s parameter with the back-propagation instantly, and the target encoder’s parameter is asynchronously updated with momentum by

where the calculations of loss are similar to Equation (17) and Equation (18) but , where and are the online encoder and the momentum encoder of modality m, respectively.

The overall loss of OPICE is given below:

where denotes the ICL operated on joint embedding.

To address the limitation posed by the scarcity of training data, we propose an iterative enhancement strategy. During the iterative inference phase, entity correspondences are identified based on cosine similarity computed between their joint embeddings, and newly aligned seed pairs are generated to augment the training set. Considering that these automatically generated seed pairs may contain noise, we further incorporate an iterative cleaning mechanism. This process retains only those entity pairs whose alignment confidence exceeds a predefined threshold, while low-confidence pairs are excluded from the training set, thereby achieving dynamic data refinement and noise reduction throughout the training process. Specifically, the confidence of and is calculated as follows:

where and are the embedding similarity and neighborhood similarity, respectively; represents the cosine similarity of x and y; is the number of structural neighbors of entity e; stands for the number of matching entity pairs in the sets x and y; and and are learnable parameters where .

3.7. Computational Complexity Analysis

We analyze the computational complexity of OPICE with the total number of entities as the core variable, where d denotes the embedding dimension (a constant) and represents the number of modalities.

The overall complexity is dominated by two key modules: (1) the multi-modal knowledge embedding module, where the self-attention mechanism for graph structure encoding contributes ; and (2) the inter-modal consistency enhancement module, where cross-modal multi-head attention between m modalities leads to (since m is a constant).

Other components introduce negligible complexity: the pseudo-label generation module operates within ontology-aligned subsets (constant size), resulting in linear complexity ; momentum contrastive learning and orthogonal loss calculation are constant-level , as they are irrelevant to n.

Thus, the overall computational complexity of OPICE is , which is scalable for medium-scale multi-modal knowledge graphs (e.g., FB–DB15K and FB–YAGO15K) as validated in our experiments.

4. Experiments

4.1. Data Sets

In our experiments, we utilize two multi-modal datasets, FB–DB15K and FB–YAGO15K (see Table 2), originally introduced by [10]. These datasets are built upon FB15K, a widely adopted benchmark for link prediction. By leveraging the SameAs alignment links available in DBpedia and YAGO knowledge bases, entities corresponding to those in FB15K are extracted. These aligned entities form the basis for constructing the DB15K and YG15K datasets. To provide a clearer understanding of the datasets used in our experiments, we additionally present a raw data sample from FB15K. As shown in Table 3, each entity in the MMKG contains multiple modalities, including textual entity descriptions, attribute triples, relation triples, and links to image resources. The specific visual-modality information can be found in the entity images shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3.

Table 2.

Main data on three multi-modal knowledge graphs.

Table 3.

Raw data samples from the MMKG datasets used in our experiments.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the alignment likelihood between entities across different MMKGs, we compute the cosine similarity between their embeddings. For performance evaluation, we adopt three widely used metrics: Hits@N (H@N), Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), and Mean Rank (MR). A higher H@N and MRR indicate superior alignment accuracy, while a lower MR reflects better ranking performance.

4.3. Model Configurations

We initialize all weight matrices using the Xavier normal distribution [34] to ensure stable convergence. For the visual encoder, we employ a ResNet-50 architecture pre-trained on the ImageNet [35] dataset to leverage rich visual representations. The GAT encoder consists of two hidden layers and employs two attention heads, with structural features projected into a 300-dimensional space. Visual, attribute, and relational features are initially mapped to 2048, 768, and 1000 dimensions, respectively; subsequently, all four modality-specific embeddings are unified into a 300-dimensional joint space. All models are trained using a batch size of 1024 and a learning rate of 1 × 10−3. Training is limited to 1500 iterations, during which the first 500 iterations are conducted without iterative augmentation. In the remaining 1000 iterations, we apply an iterative learning and cleaning strategy to progressively enhance both the size and the quality of the training set.

To ensure the reproducibility of the pseudo-label generation process for attribute alignment, we provide the full configuration of the large language model used in our experiments. All pseudo-labels were generated using GPT-4 (OpenAI API, model version June-2024) rather than a locally deployed model. We adopted a few-shot prompting strategy, where several manually selected examples of aligned attribute pairs were inserted into the prompt to guide the one-to-one mapping behavior of the model. To minimize randomness, we used temperature = 0.0, top-p = 1.0, and max_tokens = 256. Each attribute-alignment result was generated in a single run without majority voting. We reran the alignment inference three times on 100 randomly sampled attribute pairs. The results were consistent in 97% of cases, demonstrating that pseudo-label generation is stable and not sensitive to stochastic effects.

4.4. Baseline Models

To validate the effectiveness of OPICE, we compare it with several representative and competitive entity alignment methods, which are broadly classified into two categories: traditional entity alignment approaches and multi-modal entity alignment approaches. Specifically, OPICE was compared with the following methods:

IPTransE [36]: A joint-embedding-based entity alignment method that maps entities and relations from different knowledge graphs into a shared semantic space using a small set of seed alignments.

GCN-Align [37]: A novel cross-lingual knowledge graph alignment framework that leverages graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to spread information on the graph.

BootEA [17]:A bootstrap-based entity alignment method that treats alignment as a classification task by iteratively labeling candidate pairs and improves training with truncated negative sampling.

MMEA [13]: A method that encodes entities from relational, visual, and numerical data, then projects these embeddings into a shared space for multi-modal fusion.

EVA [16]: A fully self-supervised entity alignment method that uses visual similarity to build an initial seed dictionary, whose entries are called visual pivots.

MCLEA [32]: A method that uses multi-modal encoders and two loss functions—intra-modal contrastive loss and inter-modal alignment loss—to learn robust embeddings and improve entity alignment.

MSNEA [15]: MA method that extracts visual, relational, and attribute features; uses visual cues to guide relation and attribute feature integration; and applies multi-modal contrastive learning to improve fusion and alignment.

MEAformer [14]: A Transformer-based model that introduces a meta-modality hybrid mechanism to dynamically fuse structural, visual, and textual features via cross-modal attention, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of entity alignment in multi-modal knowledge graphs.

PCMEA [18]: A semi-supervised multi-modal entity alignment method that improves accuracy by calibrating pseudo-labels. It combines a small quantity of labeled data with unlabeled data, generates initial pseudo-labels, and then refines them to reduce noise for more robust alignment.

OTMEA [25]: A method that recasts MMEA as a Wasserstein problem, aligning each modality’s distribution to the structural one via optimal transport, and fuses the transported embeddings with entity-level attention to mitigate heterogeneity.

GSIEA [24]: A method that alleviates graph-structure disparity by injecting structural keys/values as prefixes into cross-modal attention, while a convolution-enhanced FFN extracts fine-grained local features for robust multi-modal fusion.

CDMEA [26]: A method that formulates a causal graph; estimates the total effect of visual and graph cues; and debiases predictions by subtracting the natural direct effect of images, forcing the model to rely on the total indirect effect.

4.5. Main Results

We compare OPICE with several representative and state-of-the-art baselines from both traditional and multi-modal entity alignment tasks on the FB15K-DB15K and FB15K-YG15K datasets. We note that recent studies have leveraged large language models (LLMs) for entity alignment. However, as these approaches primarily focus on cross-lingual knowledge graphs and rely solely on textual inputs, we did not include them in our main comparison. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first self-supervised entity alignment model evaluated on these two datasets. Therefore, we report performance comparisons with supervised models as reference. Our pseudo-label generation module produces 1713 seed pairs on FB15K-DB15K (approximately 13.3%) and 688 seed pairs on FB15K-YG15K (approximately 6.2%), whereas the supervised baselines utilize 20% of entity pairs as training seeds. Table 4 presents the performance of all compared methods.

Table 4.

EA results on FB–DB15K and FB–YAGO15K. A “-” denotes that the results are not available. The best results are highlighted in bold, and the second best results are underlined.

From Table 4, we draw the following observations: First, our model achieves performance competitive with or even surpassing that of many supervised MMEA-based baselines across most metrics on both datasets under standard reported settings. Specifically, compared to the strongest existing multi-modal baseline, OPICE achieves substantial improvements of 19.5% on Hit@1 and 15.9% on MRR, demonstrating its effectiveness in a weakly supervised context. Second, multi-modal alignment methods generally outperform traditional alignment approaches, validating the hypothesis that integrating multi-modal information can better exploit the available data. Compared to the best traditional method, OPICE yields remarkable gains of 150.2% on Hit@1 and 105.9% on MRR, further highlighting the strength of multi-modal fusion. Third, despite using very few pseudo-labels for training, OPICE achieves impressive Hit@1 scores of 0.8093 and 0.6264 on the two datasets, respectively. This advantage can be attributed to the model’s capability to mitigate noise during iterative training and its effective exploitation of cross-modal semantic correlations during fusion. Additionally, a notable performance decline is observed on the FB–YG15K dataset. We hypothesize that this is primarily due to the limited attribute coverage in YAGO15K, which hampers ontology alignment and results in insufficient pseudo-labeled pairs for effective training.

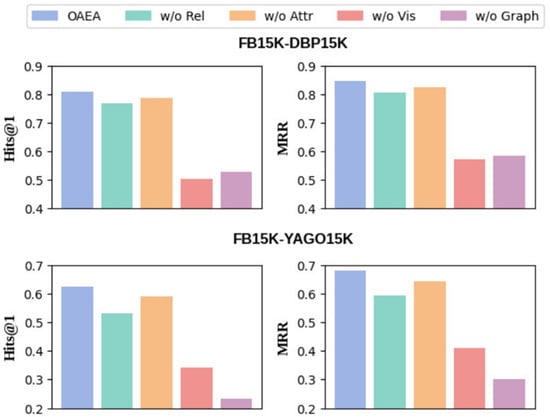

4.6. Ablation Study

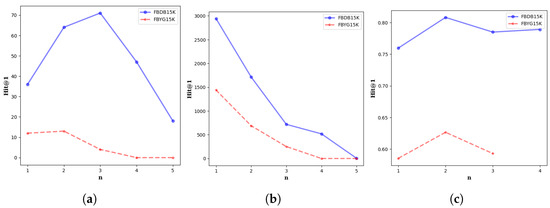

To investigate the contribution of each component in our proposed OPICE model, we conducted two groups of ablation studies: one group for modality ablation and another for component ablation. For modality ablation, we systematically removed each modality—structure (w/o G), relation (w/o R), attribute (w/o A), and visual (w/o V)—to examine their individual impact. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 4. For component ablation, we further evaluated several key components of the model. w/o IT removes both the iterative learning and iterative cleaning mechanisms. w/o clean disables only the iterative cleaning process. w/o ICL and w/o MOCO refer to the elimination of the contrastive learning module and the momentum contrastive learning mechanism. w/o orth excludes the modality consistency enhancement and the associated orthogonality loss.

Figure 4.

Results of modality ablation in OPICE.

The results of the modality ablation study clearly demonstrate that each modality contributes positively to the overall performance of OPICE across both datasets. Notably, the most influential modality varies between datasets: on FB-DB15K, the visual modality plays the dominant role, whereas on FB-YG15K, the structural modality is more critical. This discrepancy may stem from differences in dataset characteristics, such as the richness of visual or structural information. Regarding the component ablation study, all examined components are shown to be essential for optimal performance in Table 5. In particular, the absence of iterative cleaning (w/o clean) results in the accumulation of noise, which degrades alignment performance. Removing modality consistency enhancement and the associated orthogonality loss (w/o orth) severely hinders the model’s ability to capture semantic correlations across modalities, leading to a substantial drop in accuracy. The exclusion of iterative learning (w/o IT) causes a drastic performance decline, underscoring its role in enhancing model robustness through progressive refinement. The absence of contrastive learning (w/o ICL) or the momentum mechanism (w/o MOCO) significantly reduces alignment performance, as contrastive learning effectively clusters semantically similar entities while pushing dissimilar ones apart.

Table 5.

Ablation study results on FB-DB15K and FB-YAGO15K.

4.7. Case Study

To provide an intuitive understanding of the role of ontology alignment in pseudo-label generation, we conduct a qualitative case study with an entity pair sampled from different knowledge graphs, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Table 6.

Figure 5.

Case study of ontology alignment in pseudo-label generation. (a) Without ontology alignment, the entity pair fails Bi-NN matching and is excluded. (b) With ontology alignment, shared attributes place the pair in a candidate subset, enabling Bi-NN recognition and inclusion into the pseudo-label set.

Table 6.

OPICE case study result.

The analysis compares two conditions:

Without ontology alignment. In this setting, the pseudo-labeling process relies purely on visual similarity. Since the pair exhibits only weak visual resemblance, the bidirectional nearest neighbor (Bi-NN) strategy, which requires each entity to be the nearest neighbor of the other in the embedding space, cannot be satisfied. Consequently, the pair is discarded and excluded from the pseudo-label set.

With ontology alignment. In this setting, the entities are first compared at the ontology level. Several of their attributes are found to be semantically consistent (e.g., category, type, or descriptive properties), which indicates that they likely belong to the same ontology class. Based on this evidence, the pair is included in a candidate alignment subset. Within this reduced candidate pool, visual similarity assessment becomes more reliable. The Bi-NN evaluation now successfully recognizes the two entities as a match, and the pair is incorporated into the pseudo-label set.

4.8. Further Analysis

The parameter n, which defines the minimum number of shared attributes required to generate pre-aligned entity pairs through ontology alignment, plays a crucial role in determining both the scale and the quality of the generated seeds, as well as the final entity alignment performance. Its influence can be analyzed from three perspectives: (i) the number of aligned ontologies, (ii) the number of generated seed pairs, and (iii) the final Hit@1 accuracy.

Influence on the number of aligned ontologies. As shown in Figure 6a, on FB-DB15K, the number of aligned ontologies grows steadily from 36 at to 64 at , peaking at 71 when . However, a sharp decline to 47 is observed at . A similar trend occurs on FB-YG15K, where aligned attributes rise from 12 () to 13 () but drop drastically to 4 at . This pattern suggests that moderate thresholds (e.g., or ) are beneficial in activating a wider spectrum of reliable ontology correspondences by filtering out noisy or ambiguous matches. However, an overly strict threshold (e.g., ) excludes too many attribute alignments, thereby limiting the diversity of ontological signals.

Figure 6.

Further Analysis of the impact of hyper-parameter n. (a), (b) and (c) represent the effects of the value of hyperparameter n on the number of ontologies, the number of pre-aligned seeds, and the Hit@1 score, respectively.

Influence on the number of generated alignment seed. By observing Figure 6b, we can observe that the number of entity seed pairs derived from these aligned ontologies shows a monotonically decreasing trend with larger n on both FB-DB15K and FB-YG15K. This sharp reduction reflects a fundamental trade-off: lower thresholds admit more candidate pairs, increasing coverage at the expense of introducing more noise; higher thresholds enforce stricter matching, producing more reliable but far fewer seed pairs.

Influence on Hit@1 performance. The downstream performance, evaluated by Hit@1, further illustrates the balance between coverage and precision. By observing Figure 6c, we can observe that consistently achieves the best alignment accuracy. Specifically, when , the abundance of seeds introduces excessive noise, weakening supervision quality; when , the drastic reduction in seed size hampers training, despite improved precision. Thus, provides an optimal balance between noise suppression and seed sufficiency.

Notably, n is not a fixed hyperparameter and should be adapted to different datasets. Datasets with higher attribute density or cross-graph attribute overlap may benefit from larger n, while those with sparse or low-overlap attributes require smaller n. For practical application, we recommend testing n within the range [1, 5] and selecting the value that maximizes key metrics (Hit@1 and MRR) for the target dataset, following the comparative experiment design adopted in this study.

Overall, the analysis reveals that the attribute threshold n significantly influences both the scale and the reliability of ontology-derived supervision. A moderate setting () maximizes the utility of aligned attributes, yields a sufficient number of high-quality seed pairs, and consequently delivers superior alignment accuracy. Extremely low or high values of n impair this balance, either by introducing noise or by restricting supervision, leading to suboptimal performance.

4.9. Runtime and Cost Analysis

To enhance the practicality of OPICE, we provide key runtime metrics based on our experimental setup: training is conducted on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU, and LLM inference relies on official APIs for attribute alignment.

For the LLM-based attribute alignment stage, each dataset requires approximately five calls with batch processing to ensure efficiency. The total runtime for this stage is about 45 min for FB-DB15K and 38 min for FB-YAGO15K.

Regarding model training, the total number of iterations is 1500 with a batch size of 1024. The GPU training time is 2.5 GPU hours for FB-DB15K and 2.2 GPU hours for FB-YAGO15K. These metrics confirm that OPICE is computationally efficient with low resource consumption, making it suitable for real-world multi-modal entity alignment tasks.

4.10. Robustness Discussion in Realistic Scenarios

OPICE is inherently robust to common imperfections in real-world multi-modal knowledge graphs, thanks to its modular design and cross-modal complementary mechanism.

For missing images, the adaptive multi-modal fusion framework automatically downweights the absent visual modality and compensates by leveraging structural, attribute, and relational information—consistent with the model’s observed resilience to attribute sparsity in FB-YAGO15K.

When attributes are missing, the ontology-guided pseudo-label generation module avoids over-reliance on single-modality signals, instead utilizing remaining structural and visual cues to maintain semantic coherence, mitigating performance degradation as evidenced by FB-YAGO15K’s results despite limited attribute coverage.

For noisier text (e.g., typos in attribute names or inconsistent descriptions), the LLM-based attribute alignment captures core semantic equivalence beyond surface-level variations, while inter-modal consistency enhancement and orthogonal constraints further filter noise by leveraging complementary modalities (structure and vision). These inherent design features ensure that OPICE maintains reliable self-supervised alignment performance under realistic, imperfect conditions, reinforcing its practical applicability.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we propose OPICE, the first self-supervised model for multi-modal entity alignment on FB15K-DB15K and FB15K-YG15K. OPICE leverages ontology alignment to generate high-confidence pseudo-labels and incorporates an attention-based modality weighting mechanism to effectively fuse structural, visual, and attribute information into joint embeddings. Extensive experiments demonstrate that OPICE not only reduces reliance on manually labeled seed pairs but also attains performance competitive with that of many supervised baselines trained with 20% labeled data under standard reported settings. These results highlight the effectiveness and robustness of our pseudo-label generation strategy, as well as the potential of self-supervised approaches to advance multi-modal entity alignment under low-resource and noisy conditions.

Despite these promising results, OPICE still has certain limitations. When the knowledge graph contains very sparse attribute information, the quality of ontology-based alignment decreases, which may weaken the reliability of pseudo-label generation. In addition, the current model configurations and hyperparameters are manually selected, leaving room for further improvement in training stability. Moreover, although we refer to the textual modality, the current model only encodes attribute names using BERT and does not incorporate richer entity descriptions or other natural-language text, which we acknowledge as a limitation of this work and leave for future improvement.

In the future, we plan to further enhance OPICE by integrating metaheuristic hyperparameter optimization techniques, such as the Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SOA [38]), to automatically search for optimal model configurations and improve training stability. In addition, we will explore the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs [39]) to augment multi-modal data in low-resource settings, which is expected to improve the quality and reliability of pseudo-label generation under data imbalance and noise. We believe that incorporating these techniques will make self-supervised multi-modal entity alignment more robust and scalable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and X.L.; methodology, Y.W. and Z.G.; validation, Y.W., Z.G. and Y.M.; investigation, L.S.; resources, X.L.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.W., Z.G., G.M. and F.L.; supervision, Z.G. and F.L.; project administration, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project ZR2022QF085 and project ZR2024QF125 of the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on Github at https://github.com/mniepert/mmkb (accessed on 23 December 2025) reference number [10].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lehmann, J.; Isele, R.; Jakob, M.; Jentzsch, A.; Kontokostas, D.; Mendes, P.N.; Hellmann, S.; Morsey, M.; Van Kleef, P.; Auer, S.; et al. Dbpedia–a large-scale, multilingual knowledge base extracted from wikipedia. Semant. Web. 2015, 6, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanek, F.M.; Kasneci, G.; Weikum, G. Yago: A core of semantic knowledge. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web, Banff, AL, Canada, 8–12 May 2007; pp. 697–706. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Hu, Z.; Chua, T.S. Unifying knowledge graph learning and recommendation: Towards a better understanding of user preferences. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, B.; Hu, Y.; Cui, M.; Wu, Q. Mukea: Multimodal knowledge extraction and accumulation for knowledge-based visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5089–5098. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. Neural knowledge acquisition via mutual attention between knowledge graph and text. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, M.; Yu, J. Prompting large language models with answer heuristics for knowledge-based visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 14974–14983. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Shen, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Dgr: A general graph desmoothing framework for recommendation via global and local perspectives. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.04287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Cao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, K. Multi-modal knowledge graphs for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtually, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 1405–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Deng, L.; Wang, C.; Lian, J.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, N.J.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, H. Comet: Nft price prediction with wallet profiling. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 5893–5904. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Garcia-Duran, A.; Niepert, M.; Onoro-Rubio, D.; Rosenblum, D.S. MMKG: Multi-modal knowledge graphs. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Conference, Portorož, Slovenia, 2–6 June 2019; pp. 459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Xu, T.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J.; Chen, E. Relation-enhanced negative sampling for multimodal knowledge graph completion. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 3857–3866. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, J.; Xu, T.; Xia, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, E.; Dou, D. Multimodal biological knowledge graph completion via triple co-attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 3928–3941. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, E. MMEA: Entity alignment for multi-modal knowledge graph. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management, Hangzhou, China, 28–30 August 2020; pp. 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.; Fang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, Y.; Pan, J.Z.; Song, W.; et al. Meaformer: Multi-modal entity alignment transformer for meta modality hybrid. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 3317–3327. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, T.; Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, N.J.; Chen, E. Multi-modal siamese network for entity alignment. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Chen, M.; Roth, D.; Collier, N. Visual pivoting for (unsupervised) entity alignment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 4257–4266. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Bootstrapping entity alignment with knowledge graph embedding. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Qi, P.; Bao, X.; Zhou, C.; Qin, B. Pseudo-label calibration semi-supervised multi-modal entity alignment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 9116–9124. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Oh, B.; Hwang, S.w.; Li, J. HLMEA: Unsupervised Entity Alignment Based on Hybrid Language Models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 11888–11896. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Su, Y.; Trisedya, B.D.; Zhao, X.; Yang, M.; Cheng, H.; Qi, J. Autoalign: Fully automatic and effective knowledge graph alignment enabled by large language models. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 36, 2357–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, N.; Cheng, R.; Kao, B.; Ning, W.; Haldar, N.A.H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Najafi, M.M.; Li, T.; Qu, G. Zeroea: A zero-training entity alignment framework via pre-trained language model. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, T.; Wang, Z. LLM-Align: Utilizing Large Language Models for Entity Alignment in Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.04690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Y.; Wu, W.; Xiong, H. Tackling uncertain correspondences for multi-modal entity alignment. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 119386–119410. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, K.; Li, Z. Graph structure prefix injection transformer for multi-modal entity alignment. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Liang, Q.; Bao, F. OTMEA: Multi-modal Entity Alignment via Optimal Transport. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025–2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.; Sheng, J.; Ma, D.; Li, X.; Yue, J.; Song, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, T. Mitigating Modality Bias in Multi-modal Entity Alignment from a Causal Perspective. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Padua, Italy, 13–17 July 2025; pp. 1186–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.W.; Zou, Y.; Shi, P.; Lu, W.; Lin, J.; Sun, X. Aligning cross-lingual entities with multi-aspect information. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.06575. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tong, P.; Jin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ye, J.; Xiong, H. Plan-on-graph: Self-correcting adaptive planning of large language model on knowledge graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 37665–37691. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Shi, Y.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Y. Multi-modal contrastive representation learning for entity alignment. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.00891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 9729–9738. [Google Scholar]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, Sardinia, Italy, 13–15 May 2010; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Xie, R.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. Iterative Entity Alignment via Joint Knowledge Embeddings. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; Volume 17, pp. 4258–4264. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Y. Cross-lingual knowledge graph alignment via graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.K.; Veerasamy, B.D.; Alduaiji, N.; Addula, S.R.; Pandey, A.; Shukla, P.K. Fraudulent account detection in social media using hybrid deep transformer model and hyperparameter optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.