Abstract

Single-phase-to-ground faults occur frequently in distribution networks, while traditional localization methods have limitations such as insufficient feature extraction and poor topological adaptability. To address these issues, this paper proposes a two-stage localization method that integrates the Node Classification Matrix (NCM) and an Improved Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (IBPSO) algorithm. The NCM achieves rapid initial localization, and the IBPSO performs error correction. This paper employs an IEEE 33-node standard distribution network model to design simulations covering scenarios with varying fault locations, multiple fault resistances, and different numbers of node distortions for validation. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a fault location accuracy of 96%, which is 19% higher than that of the NCM alone and 2% higher than that of the IBPSO alone. Moreover, it maintains an accuracy of over 95% under scenarios of 1–3 node distortions, topological switching, and high-impedance faults, and is compatible with existing Feeder Terminal Unit (FTU) devices. This method effectively balances localization speed and robustness, providing a reliable solution for the rapid fault isolation of distribution network.

1. Introduction

Distribution networks function as critical hubs connecting transmission systems and power users, with their safe and stable operation directly impacting national economic development and residents’ quality of life. Statistics show that single-phase-to-ground faults account for approximately 70–80% of all faults in distribution networks [1]. This type of fault is characterized by low ground-fault current and transient symmetry of system voltage, and can theoretically persist for a short duration. However, overvoltage in healthy phases may induce arc discharge, accelerating the insulation aging of equipment, and even expanding into phase-to-phase short circuits [2].

However, existing fault location algorithms exhibit distinct limitations regarding feature extraction, scope of application, and topological adaptability, making it difficult to efficiently handle single-phase-to-ground faults under complex operating conditions. A sharp contradiction exists between the weak fault signatures, limited applicability, and complex topologies involving multiple nodes and sections, versus the critical need to rapidly identify and isolate faults to ensure system safety [3,4]. Consequently, developing reliable, adaptable, and accurate fault location methods is essential to guide corrective measures and minimize the impact of outages. With the increasing coverage of FTU, the fusion and utilization of massive monitoring data have become feasible [5,6,7]. Research into efficient SPG fault section location technologies suitable for diverse fault conditions and complex topologies can reduce both the scope and duration of faults in multi-section distribution networks, thereby enhancing the self-healing capability and power supply reliability [8].

Current distribution network fault location technologies can be broadly classified into four categories, each with distinct limitations that hinder their performance under complex operating scenarios:

- (1)

- Matrix-based methods utilize topology and fault information matrices derived from graph theory to rapidly match fault sections through matrix operations, offering high computational efficiency [9]. However, the accuracy of such methods relies heavily on the integrity of FTU data. As core sensing devices, FTUs collect node current and voltage measurements, forming the basis for fault feature extraction. In practical engineering, FTU data are inevitably affected by sensor inaccuracies, electromagnetic interference, and equipment aging, leading to typical errors [10,11,12]. These errors distort transient fault features and reduce location reliability.

- (2)

- Intelligent Optimization-based Methods: These methods transform the location problem into a 0–1 integer programming task. For example, the traditional Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (BPSO) algorithm searches for the optimal solution through particle iteration, offering superior robustness compared to matrix methods. However, conventional BPSO is prone to local optima, fails to leverage topological prior information, and relies on exhaustive search, often requiring over nine iterations and exceeding 200 ms for localization [13,14,15], which challenges real-time application requirements.

- (3)

- Signal Analysis-based Methods: These methods extract fault features utilizing zero-sequence current or voltage, exhibiting high specificity [16,17]. Nevertheless, their effectiveness depends heavily on measurement node density, and they require recalibration of feature thresholds upon topology changes, resulting in poor adaptability.

- (4)

- Deep Learning-based Methods: Emerging models in recent years, such as CNNs and LSTMs, improve accuracy through data-driven approaches. However, they demand large volumes of fault samples, lack interpretability, and are sensitive to output fluctuations from distributed generation. Accuracy can degrade by up to 15% under sample distribution shifts [18,19,20], posing significant challenges for practical deployment.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper analyzes the fault characteristics of distribution networks and proposes a location method fusing a CNM algorithm with an IBPSO algorithm. The proposed approach demonstrates significant superiority over traditional algorithms in terms of location speed, fault tolerance, and global optimization capability.

2. Fault Section Location Algorithm Based on NCM

2.1. Algorithm Principles

Traditional matrix-based algorithms struggle to pinpoint faults in terminal line segments. Furthermore, complex matrix calculations are required for their normal operation. This makes computations cumbersome for distribution networks with multiple nodes and complex topology. To address these issues, a fault segment localization method based on a NCM is proposed. This method constructs a network topology matrix that represents the distribution network’s structure using graph theory. It then generates a fault path matrix and a fault determination matrix. When a fault occurs, the node upstream of the faulted section is identified as the faulty node, while the downstream node is considered healthy. The section between these two nodes forms the fault path. By referencing the corresponding matrix element in the fault determination matrix for this path, the fault section can be localized quickly and accurately.

Assuming there are N nodes on the line, the line’s topological structure can be represented by an Nth-order matrix, defined as shown in Equation (1):

where D represents the network topology matrix, and di·j denotes the element in the i row and j column of D. When nodes i and j are electrically connected on a line and current flows from i to j, di·j = 1. When there is no electrical connection between nodes i and j or current flows from j to i, di·j = 0.

The NCM S is a row matrix of size 1 × N, where its elements are determined by node types. During single-phase ground faults in distribution networks, node states fall into only two categories: faulty nodes and healthy nodes. Therefore, the node classification results can be expressed using discrete integer values of 0 or 1. If calculations indicate that the i node is the fault node upstream of the fault, it is denoted as si = 1; otherwise, it is denoted as 0. The NCM S and the si formula are shown in Equations (2) and (3):

The fault path matrix B is an N × N matrix, defined by Equation (4), representing the upstream paths of fault points. It is jointly determined by the network topology matrix and node classification results. The element bi·j in B corresponds to row i and column j. If the segment between node i and node j has a topological connection and lies on the fault upstream path, bi·j = 1; otherwise, the segment is a non-fault path, denoted as bi·j = 0. The specific generation steps are as follows: Query the element si in the NCM S. When si = 0, node i is a healthy node downstream of the fault, and all connected downstream segments are non-fault paths. Therefore, set all entries in row i of the topology matrix D to 0. When si = 1, the node is a faulty node upstream of the fault. Query the elements in row i of D. If only one element di·j = 1 exists in this row, it proves that faulty node i is connected to only one segment, and the line segment between nodes i and j must be the fault path, and di·j = 1. If multiple elements in the row are 1, this indicates the node is connected to multiple segments. Compare the zero-sequence current transient energy matrices at the start of each segment; the largest value corresponds to the fault section, and di·j = 1, while the others are set to zero.

The fault diagnosis matrix G can simultaneously represent both the node classification results and the fault path matrix. The element gi·j in G, located at row i and column j, is obtained by filling the main diagonal of the fault path matrix B with values from the NCM S. The expression is shown in Equation (5):

2.2. Fault Section Identification Process

Precise fault section localization can be achieved by analyzing the state characteristics of nodes at both ends of the fault path. Specifically, for nodes i and j at the two ends of the fault section, where node i (upstream) is the faulty node and node j (downstream) is the healthy node, and the topology between nodes i and j is in a connected state and constitutes the fault path, the following fault section identification process is established based on this characteristic:

First, scan the elements along the main diagonal of the matrix to locate the first non-zero element gi·i. The node corresponding to this element, i is identified as the initial fault node. Next, check whether any other non-zero elements gj·j = 1 exist in the row containing the fault node i. If present, this confirms an active electrical connection exists between nodes i and j, forming the fault current path. Further validate node j status. If gj·j = 0, node j is healthy, confirming the fault section lies between nodes i and j. If gj·j = 1, continue searching downstream nodes.

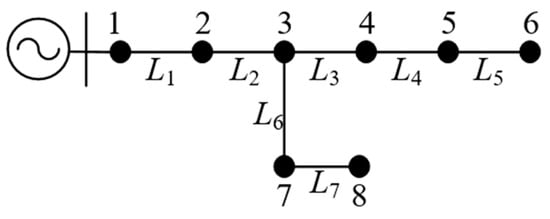

To illustrate the implementation process of the aforementioned discrimination method, we will now analyze it step by step using the system shown in Figure 1 as an example:

Figure 1.

Typical 8-Node Distribution Network Topology Diagram.

First query detected g1·1 = 1, queried g1·2 = 1. Since g2·2 = 1 was detected, search continued; second query found g2·2 = 1 and g2·3 = 1, but further detection revealed g3·3 = 1; thus, the fault was not between Node 2 and Node 3. The third query results in g3·3 = 1, g3·4 = 1, and g4·4 = 1, still unable to pinpoint the fault section. The fourth query finds g4·4 = 1, with g4·5 = 1 in the same row and g5·5 = 1, thus outputting the following result: Fault section L4.

2.3. Algorithm Fault Tolerance Analysis

The aforementioned analysis is based on the ideal assumption that node classification information remains distortion-free. In practice, however, the binary classification results of nodes may undergo distortion (e.g., 0→1 or 1→0), directly affecting the fault discrimination matrix. This impacts the localization of the NCM algorithm, causing the localization results to differ from the actual fault section. The following analysis addresses scenarios involving distorted node classification results.

Taking the system shown in Figure 1 as an example, when distortion occurs at the fault node upstream of the fault point—such as a fault in section L4—the classification information of the upstream node at fault node 2 becomes erroneous. The information at node 2 changes from 1 to 0, causing the fault determination matrix G to alter:

Performing a fault section query operation on matrix G identifies fault sections L1 and L4, which contradicts the expected results. This indicates that distortion at nodes upstream of the fault can easily lead to non-unique fault section localization, resulting in the output of pseudo-fault sections.

When the downstream healthy node experiences distortion at the fault point, the fault still occurs in segment L4. The distorted information transmitted from the six downstream healthy nodes changes Node 6 from 0 to 1, resulting in the following matrix G:

In this scenario, the fault section can still be correctly identified as L4. Therefore, when a node downstream of the fault becomes a faulty node, it does not affect the accuracy of this method.

In summary, the NCM-based fault location algorithm achieves its function by analyzing the state characteristics of nodes at both ends of the fault path. It features a clear structure, simple operation, and fast location speed, but relies heavily on the accuracy of node classification results. When the calculation results for the faulty node are distorted, multiple fault segments may be generated, inevitably expanding the power outage area. However, the location results also contain the actual fault segment. Therefore, further error correction measures need to be implemented to refine the location results and enhance their accuracy.

3. The IBPSO Algorithm for Fault Section Localization

The node classification information and distribution network topology information mentioned earlier are both represented by “1” and “0”. Therefore, the section localization problem can be viewed as an optimization problem with 0–1 discrete constraints, which can be solved using intelligent optimization algorithms with high fault tolerance. This section proposes employing the BPSO Algorithm as the base solution method. However, considering the BPSO Algorithm limited particle search range—which restricts its ability to explore broader optimal solutions and makes it prone to local optima—we introduce genetic and mutation concepts to integrate with it. This generates an IBPSO Algorithm, enhancing its global search capability and convergence speed to achieve precise positioning with high fault tolerance.

3.1. The BPSO Algorithm Principles

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) constructs a probabilistic search-based optimization framework by simulating the cooperative decision-making mechanism observed in bird flocks during foraging. In the PSO mathematical model, candidate solutions to the optimization problem are abstracted as particles in a multidimensional space. Each particle possesses two key parameters: a position vector and a velocity vector. Throughout the search process, each particle continuously records its Personal Best (Pbest) and the Global Best (Gbest) to update its motion state. The search formula is shown in Equation (8).

where Vidn represents the velocity component in the d-th dimension of the i-th particle during the n-th iteration, while Xidn denotes its corresponding position coordinate; ω1 is the dynamic inertia coefficient, used to balance the relationship between global exploration and local exploitation; c1 and c2 represent the individual and global learning factors, respectively; r1 and r2 are random numbers between [0, 1]; Pidn denotes the d-th dimension component of the individual historical optimal coordinate for particle i at iteration n; Gnd represents the d-th dimension component of the global optimal coordinate for the population at iteration n.

Most data in feeder automation systems are represented as discrete binary information in the form of 0 s and 1 s. To effectively address this binary variable-based fault detection problem, the discrete BPSO algorithm is selected. Compared to the PSO algorithm, the velocity V in the traditional BPSO algorithm represents the probability that position X is either 1 or 0. As velocity V increases, the probability that position X equals 1 also increases; conversely, the probability that position X equals 0 increases. Simultaneously considering the advantages and limitations of the traditional PSO algorithm, a sigmoid function is introduced to update particle positions. The sigmoid function is shown in Equation (9).

In Equation (9), Vidn is treated as the variable in the sigmoid function, with the particle velocity range defined as Vidn ∈ [−Vmax, Vmax]. When Vmax = 4, we can obtain:

where r is a random number between [0, 1]; S(x) is the Sigmoid function.

From Equations (10) and (11), the maximum value of the function is approximately equal to 1, and the minimum value is approximately equal to 0. Based on these functional characteristics, the particle’s position can be further determined, and selecting Vmax = 4 is appropriate.

3.2. The IBPSO Algorithm Principles

However, the traditional BPSO algorithm has difficulties in searching for optimal solutions over a large range and is highly prone to falling into local optima [21]. To address this issue, the traditional BPSO algorithm is improved by introducing a genetic mutation mechanism and a dynamic inertia weight strategy. This approach assigns particles with a certain probability to the locally optimal and globally optimal particles within the particle swarm, while mutating other particles with a specific probability. During the later stages of iteration, when particles begin to cluster locally, methods such as selective crossover are employed to enhance diversity among particles. This facilitates the search for superior solutions across a broader domain. The improved iteration process is outlined as follows:

where, Equation (12) represents the genetic component, Equation (13) represents the mutation component, and bf denotes the mutation factor during the iteration process.

Following the traditional algorithm’s method of setting inertial weights to decrease linearly, the parameters for the coefficient of variation are set as follows:

where t represents the current iteration count, T denotes the maximum iteration count, bfmax signifies the maximum mutation factor, and bfmin indicates the minimum mutation factor.

The IBPSO algorithm exhibits strong global search capabilities during the early iterations due to the larger mutation factor bf value, enabling exploration over a broader range. As iterations progress into the later stages, the mutation factor bf begins to decrease nonlinearly, shifting the particles’ search focus from global to local search. This transition allows particles to locate the global optimum within the neighborhood of the global optimal solution. The optimized algorithm demonstrates significantly enhanced search efficiency and convergence speed.

3.3. Fault Section Location Process

Let L(i) (i = 1, 2, 3,…, m) denote the status of the i section. When a section fails, set L(i) = 1; when section i is not in a fault state, set L(i) = 0. The specific constraints are shown in Equation (15):

The node classification status code N(i) is consistent with the definition of the NCM described above. If node i is a faulty node, then N(i) = 1; if node i is a healthy node, then N(i) = 0. The formula is as follows:

Next, to match the classification status of each node based on the section status code—that is, to determine the expected value for partitioning the node classification results—a target function must be further constructed. As noted above, when a single-phase ground fault occurs in a section, the node upstream of the fault is the faulty node, while the downstream node remains healthy. Based on this, the target function relationship is established as follows:

where represents the objective function for node i, Lx denotes the state of the downstream segment of node i, and ⋃ indicates the logical OR operation. For the terminal node of a line, which is necessarily downstream of a fault, the objective function is directly set to 0.

The principle of fault section localization based on the IBPSO algorithm is as follows: Compare the difference between the expected classification information of a node obtained through the objective function calculation and its actual classification information. The smaller the difference, the more reasonable the interpretation of the fault information becomes, and the better the fault section matches the actual fault section. The fitness function is shown in Equation (18):

where represents the expected classification information of node j determined by the objective function, Ij denotes the actual classification information of node j. Using absolute error prevents positive and negative errors from canceling each other out, ensuring that the discrepancy at each node is accounted for in the total error. N is the total number of nodes, M is the total number of segments, and ω2 is the penalty coefficient for function misclassification, typically set to ω2 = 0.5.

When the algorithm detects a “true fault segment”: The desired state of the upstream node corresponding to this segment perfectly matches its actual state Ij, while minimizing errors for other nodes. Concurrently, the penalty term is minimized, resulting in the minimum value for F. When the algorithm misidentifies a “false fault segment”: The false segment causes mismatches between its upstream node’s and Ij, significantly increasing the final F value. This is judged by the algorithm as a non-optimal solution. When the algorithm misses a “true fault segment”: All segments have L(i) = 0, resulting in a penalty term of 0. However, the deviation between and actual Ij becomes extremely large for numerous nodes, causing the total node error to surge dramatically. Consequently, the F value also increases, leading to rejection by the algorithm.

The steps for fault section location based on the IBPSO algorithm are as follows:

- (1)

- Initialize the particle swarm and set algorithm parameters, including population size, maximum iteration count, learning factor, inertia weight, maximum and minimum velocity thresholds, mutation factor, crossover probability, and initial mutation frequency;

- (2)

- Input distribution network node classification information. Calculate each particle’s fitness using the particle evaluation method, and promptly update the individual best (Pbest) and global best (Gbest);

- (3)

- Perform genetic and mutation operations. Select parent particles with higher fitness to cross over and generate new offspring particles, replacing those with poorer fitness. Apply mutation operations to particles according to predetermined probabilities. As the iteration process enters the late stage and particles gradually cluster in local regions, further enhance the convergence accuracy of particles;

- (4)

- Update particle velocity and position, recalculate fitness, reassign Pbest and Gbest, and continuously optimize search results;

- (5)

- Determine if the maximum iteration count is reached. If satisfied, terminate the loop and output the optimal solution; otherwise, return to step (3);

- (6)

- Output the binary encoding corresponding to the global optimal position solution, parse it into the fault segment location, and use this as the localization result.

4. Location Algorithm Based on Integration of NCM and IBPSO

The integration of the NCM and the IBPSO algorithm is not a simple combination of the two methods, but rather a collaborative framework constructed based on their complementary characteristics and the inherent patterns of distribution network fault location.The section localization method based on the NCM has the advantages of clear operations and simple implementation. However, when node classification information is distorted, this method is prone to misjudgment, resulting in the overlap between true fault sections and false fault sections. In contrast, the fault location method based on the IBPSO algorithm, despite its higher computational complexity, can effectively mitigate the impact of node classification distortion. Accurate identification of fault sections is still achievable even under such abnormal conditions.

The rapidity of the NCM compensates for the insufficiency in real-time performance of BPSO, and the robustness of BPSO addresses the matrix’s sensitivity to information distortion. The two thus form the theoretical basis for efficiency-accuracy complementarity.Therefore, this section integrates the strengths of both approaches, proposing a hybrid location algorithm combining the NCM with the IBPSO to enhance the reliability of location results. To ensure the rationality of parameter settings, algorithm switching follows a dual-criteria rule of “core logic + auxiliary thresholds,” balancing positioning accuracy, real-time performance, and topology adaptability.

The core trigger condition for algorithm switching is determined by the number of candidate fault sections identified by the NCM’s initial location output: when the number of candidate sections ≥ 2, it indicates that the NCM cannot uniquely pinpoint the fault path due to interference such as node distortion and measurement noise. In this case, the IBPSO algorithm is directly initiated for secondary location and error correction. This logic stems from the inherent characteristics of distribution network faults—single-phase ground faults typically involve only one genuine fault section. Multiple candidate sections inevitably result from interference factors. In such cases, IBPSO’s global optimization capability effectively eliminates false sections.

The extension of actual fault paths in distribution networks is constrained by inherent topological structures, with the number of branches never exceeding the maximum branch capacity of the faulted bus. If the number of candidate sections output by NCM exceeds “1 + maximum number of branches,” it inevitably includes numerous false sections with no topological association to the fault path, leading to redundant searches. The auxiliary threshold Kth is specifically designed for complex topologies (e.g., ring networks, multi-branch radial networks) to optimize IBPSO’s search efficiency without altering the core triggering logic. Its formula is:

where B represents the maximum number of branches on the busbar containing the fault point, which can be directly obtained by calculating the maximum value of non-zero elements in the row of the topology matrix D (each non-zero element corresponds to a connecting branch).

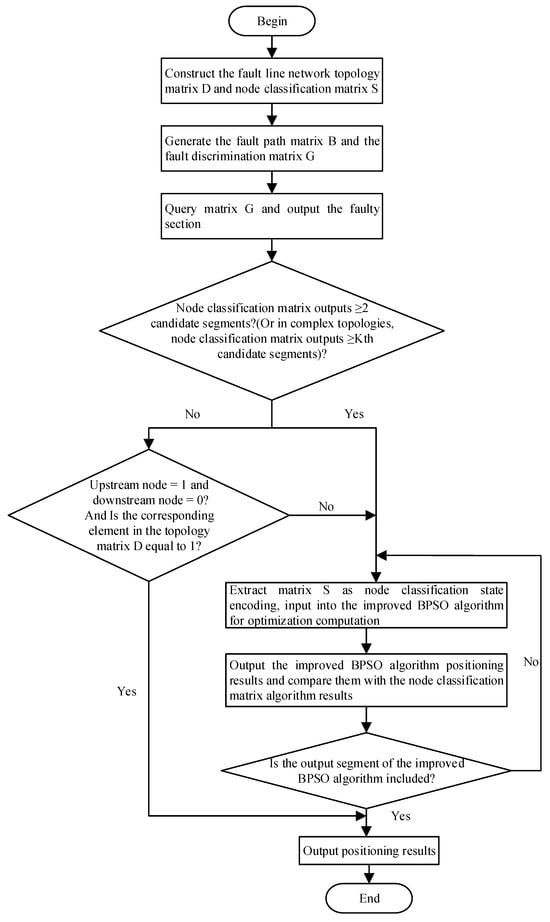

The core concept of this algorithm is as follows: First, perform rapid initial localization using the NCM algorithm. If its output indicates multiple faults, initiate the IBPSO algorithm for secondary localization and error correction. Then, verify the secondary localization results against the output of the NCM algorithm. If the fault section identified by the former is contained within the latter’s set of multiple segments, it indicates that false fault sections have been successfully eliminated. Finally, the localization results are output. To prevent misclassification when NCM outputs a single but erroneous fault segment, the algorithm framework incorporates a topology consistency verification step. This step validates the authenticity of a single candidate segment based on a dual-dimensional constraint: “the upstream node is a fault node, the downstream node is a healthy node, and electrical connections exist between the segment’s end nodes.” The algorithm’s positioning flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of fault section location method.

5. Simulation Verification and Analysis

The IEEE 33-node system aligns with the actual topology and parameter characteristics of distribution networks, fully covering core research scenarios such as high-resistance faults while effectively balancing simulation complexity and testing efficiency. Based on this, a simulation model was constructed according to the architecture shown in Figure 3 to validate the method’s performance. Nodes are numbered 1–33 and sections are labeled L1–L32. Set the particle dimension to 32, the number of particles to 20, and the maximum iteration count to 50 (convergence is permitted before iteration termination). The learning factors are c1 = c2 = 2.1, the particle dimension is d = 7, the maximum velocity is Vmax = 4, the initial inertia weight coefficient ω1 = 0.9, and the maximum mutation factor bfmax = 0.2.

Figure 3.

Distribution network of IEEE33-node system.

5.1. Effectiveness Validation

5.1.1. Fault Section Location Under Typical Conditions

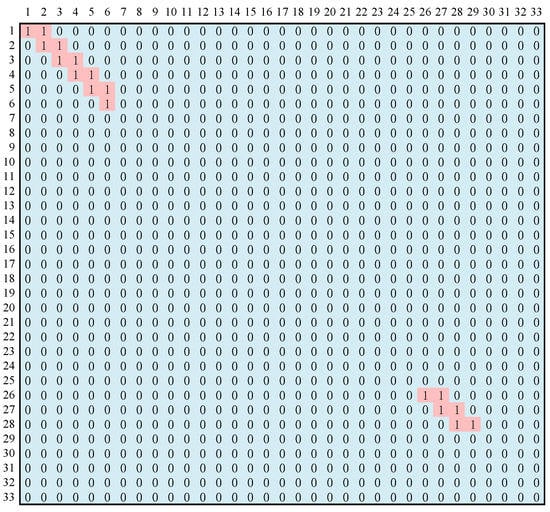

L28 was set to experience a single-phase ground fault with an initial fault angle of 90° and a transition resistance of 10 Ω. No distortion was observed in the node classification results. At this point, the NCM S is [1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0], and the fault path is segment L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, L25, L26, L27, and L28. The fault determination matrix G is presented in Figure 4. Querying reveals the fault occurred between nodes 28 and 29, thus correctly outputting the fault section as L28.

Figure 4.

Fault diagnosis matrix of L28 fault.

The simulation results with altered fault conditions and locations are shown in the table below.

As shown in Table 1, when node classification information remains unchanged, altering other conditions does not affect the correct output of the segment localization results. Furthermore, localization can be achieved solely through the first-step algorithm based on the NCM, without requiring an IBPSO algorithm supplemented by iterative operations. The results are reliable, and the localization process is simple and fast.

Table 1.

Fault section location results in multiple scenarios.

5.1.2. Fault Section Localization Under Node Classification Information Distortion

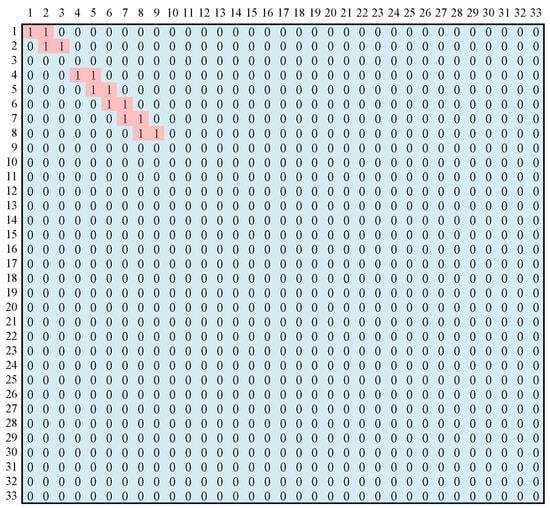

A single-phase ground fault was set in section L8 with an initial fault angle of 90° and a transition resistance of 10 Ω. Meanwhile, a single-point distortion was introduced in the node classification results: node 3 (upstream of the fault) changed from 1 to 0. At this point, the NCM S is [1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0], and the fault determination matrix G is shown in Figure 4:

Node classification distortion is a common interference factor in distribution network fault location, specifically categorized into two types: 1→0 distortion (misidentifying a fault node as a non-fault node) and 0→1 distortion (misidentifying a non-fault node as a fault node). Taking the misclassification of a fault node as a non-fault node as an example: assume a single-phase ground fault occurs in section L8 with an initial fault angle of 90° and a transition resistance of 10 Ω. The upstream node 3 experiences distortion (changing from 1 to 0). At this point, the node classification matrix S is [1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0], and the fault determination matrix G is shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

Fault diagnosis matrix of L8 fault with node 3.

Upon inquiry, the output fault sections are L2 and L8. Due to multiple fault sections being output, the enhanced BPSO algorithm is initiated. The NCM S is extracted as node classification information encoding input into the enhanced BPSO algorithm for optimization computation. The output results are: [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0], confirming fault section L8. The fitness curve evolution is shown in Figure 6. The segment output by the IBPSO algorithm matches the segment output by the NCM algorithm, confirming that segment L2 is a false fault section. The true fault section L8 is thus identified.

Figure 6.

Fitness curve of L8 fault with node 3 distortion.

Secondly, NCM-point distortion simulation verification was conducted by changing the fault section to L31. Distortion nodes were set at upstream nodes significantly affecting the location results: nodes 3, 4, and 27. All three nodes changed from 1 to 0. At this point, the S is [1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0]. Due to space constraints, the specific form of the fault determination matrix is not shown here. The matrix query results indicate the fault sections as L2, L26, L31. Secondary localization was performed using an IBPSO algorithm, with the convergence curve shown in Figure 7. The output result is [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0], confirming fault section L31. After result verification, the final correct output was segment L31.

Figure 7.

Fitness curve of L31 fault with node 3, node 4 and node 27 distortions.

Multiple simulations were conducted by altering the fault location, node distortion position, distortion type, and number of nodes. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fault section location results under various node distortions.

The simulation results demonstrate that when single-point or multi-point distortion occurs in node classification information, the NCM algorithm may initially identify multiple fault sections. However, after error correction via the IBPSO algorithm, accurate fault location can still be achieved. The method presented in this chapter exhibits excellent fault tolerance and high accuracy.

5.1.3. Fault Section Location in Distribution Networks with Topology Changes

During actual operation of distribution networks, frequent switching operations can alter the network topology. Consider the distribution network model shown in Figure 2: if the section between nodes 7 and 8 is disconnected and the section between nodes 18 and 22 is connected, simulating with these modified fault conditions and locations yields the fault location results presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fault section location results under changes in distribution network topology.

As shown in Table 3, the proposed method can still achieve accurate fault section location even when the distribution network topology changes.

5.1.4. Fault Section Location in Distribution Networks Affected by Measurement Data Errors

During actual operation of distribution networks, measurement errors inevitably occur in the current and voltage data collected by feeder terminal units (typical error range: ±0.2% to ±1%) [22]. These errors cause deviations in zero-sequence current transient energy calculations, thereby affecting the construction of node classification matrices and the accuracy of algorithmic fault location. To validate the proposed method’s robustness against measurement errors, a single-phase ground fault was induced in section L17. Random measurement errors of 0%, 0.2%, 0.5%, and 1% were introduced into the zero-sequence current data. The localization results are shown in Table 4:

Table 4.

Segment positioning results affected by measurement errors.

In summary, when measurement errors exist in the distribution network system, the proposed fusion methods can rapidly output a candidate set containing the actual fault section via the node classification matrix. Subsequently, by applying error correction through the improved BPSO algorithm to eliminate false fault sections, fault location with both high accuracy and real-time performance can still be achieved.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Fusion Algorithm Parameters

To validate the stability of the proposed method under varying parameter settings, this section employs the IEEE 33-node system. While keeping other parameters constant, only the target parameter is adjusted. Each scenario is simulated 100 times, focusing on three core metrics: candidate segment distribution, IBPSO error correction effectiveness, and final localization accuracy. This analysis examines the sensitivity of IBPSO core parameters and matrix classification thresholds.

5.2.1. IBPSO Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

The parameters of IBPSO, particularly the inertia weight (ω1) and learning factors (c1,c2), are critical for balancing global search and local convergence. Sensitivity analysis was performed by varying these parameters within standard engineering ranges [23,24,25].The result and analysis are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

IBPSO Parameter Adjustment Positioning Results.

The analysis reveals that while parameter variations influence the average iterations, but the algorithm still converged to the correct fault section in >95% of cases. This indicates that the algorithm is not overly sensitive to precise parameter tuning, simplifying field deployment.

5.2.2. Matrix Classification Threshold Sensitivity Analysis

The matrix classification threshold serves as the core basis for determining node status. The formula for the transient energy detection threshold is:

where k is the confidence coefficient, is the standard deviation of noise prior to failure, and Emin is the minimum transient detection energy.

This study employs sensitivity analysis by selecting two thresholds: the confidence coefficient and the minimum detection energy, within their commonly used ranges [26]. The localization results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Matrix Classification Threshold Adjustment Localization Results.

Increasing k from 2.0 to 4.0 strictly filters noise but results in a larger set of “uncertain” candidate sections. However, the subsequent IBPSO stage effectively resolves these uncertainties using topological constraints. Consequently, the final accuracy is decoupled from the strictness of the NCM thresholds, proving the fusion architecture’s superior fault tolerance compared to standalone matrix methods.

When the core parameters of IBPSO and the matrix classification thresholds vary within reasonable engineering ranges, the proposed method demonstrates consistent localization performance. The sensitivity analysis reveals that parameter fluctuations primarily impact computational overhead, such as the number of candidate segments generated and the iterations required for convergence, rather than the final localization accuracy. This indicates that the algorithm possesses strong robustness, as it can maintain high precision even when parameters are not optimally tuned, thereby adapting to the dynamic measurement environments encountered in practical engineering applications.

5.3. Verification of Performance Advantages of Fusion Algorithms

In the distribution network model shown in Figure 3, simulations were conducted using three algorithms: the NCM algorithm, the IBPSO algorithm, and the proposed fusion algorithm (integrating the NCM with the IBPSO). The advantages of the fusion algorithm in location accuracy and speed were then compared. Assume a fault occurs in section L12. The simulation runs 1000 times, with the fault location, number of node distortions (0–3), and transition resistance value (0.01–1000 Ω) randomly set during each simulation. The positioning performance of each algorithm is summarized in the table below:

As shown in Table 7, the NCM-based algorithm demonstrates a significant advantage in computational speed, completing fault section localization within 1.32 ms. However, it is highly prone to localization errors when node classification information is distorted, achieving only 77% localization accuracy. The IBPSO algorithm demonstrates strong fault-tolerant performance and high accuracy, but suffers from slower localization speed due to its higher iteration count, averaging 202.5 ms. The proposed fault localization model in this chapter, which integrates the NCM with the IBPSO algorithm, achieves an average processing time of 16.1 ms and a correctness rate of 96%. Crucially, even under worst-case conditions, the maximum execution time of the fusion algorithm is controlled at approximately 45.8 ms. While higher than the average, this worst-case latency is still significantly lower than that of the IBPSO algorithm and falls well within the strict operational time margins required for distribution automation. By combining the strengths of both approaches, it offers superior performance with balanced accuracy and real-time feasibility.

Table 7.

Comparison of the positioning performance of the fusion algorithm and basic algorithms.

To further validate the algorithm’s engineering adaptability under complex disturbance scenarios in actual distribution networks, robustness verification was conducted targeting common extreme disturbance scenarios (ultra-high-resistance faults, FTU measurement errors) based on the performance validation of the reference conditions in Table 7. The transition resistor was set to simulate higher-impedance faults (5000–8000 Ω), and random measurement errors (0–1%) were introduced into the zero-sequence current data. Each scenario was simulated 1000 times. The location performance of each algorithm is shown in the table below:

As shown in Table 8, while the accuracy of the traditional NCM algorithm drops significantly under interference, the proposed fusion algorithm maintains high robustness. Under these extreme conditions, the average processing time of the fusion algorithm increased to 29.3 ms due to the higher number of iterations (4.44) required to converge in a distorted search space. However, this is still significantly faster than the pure IBPSO algorithm (256.4 ms). In terms of accuracy, while the NCM algorithm’s performance deteriorated sharply to 68.5%, the fusion algorithm maintained a high accuracy of 94.2%. The slight decrease from the baseline (96%) reflects the challenge of high-impedance faults, yet the algorithm successfully mitigated most measurement errors.

Table 8.

Algorithm Performance Comparison Under Extreme Conditions.

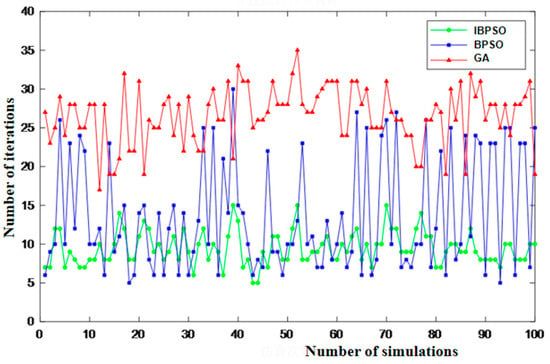

To further validate the advantages of the proposed hybrid algorithm over the IBPSO algorithm in terms of computational speed, Figure 8 presents a comparison of the minimum number of iterations achieved by each method at the conclusion of each simulation run across 100 simulations.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the number of optimization iterations of the IBPSO algorithm and the fusion algorithm.

In Figure 8, Algorithm 1 refers to the IBPSO algorithm, while Algorithm 2 refers to the fusion algorithm. As shown by the curves, the proposed fusion algorithm can complete segment localization without iterations in most cases. Its average iteration count is significantly lower than that of the single IBPSO algorithm, demonstrating a marked advantage in localization speed.

To further validate the accuracy advantages of the fusion algorithm over the single-NCM algorithm and mitigate the randomness associated with single-fault locations, simulations were conducted with fault sections set to L3, L27, and L17. Random node distortions were introduced with distortion counts of 1 and 3. Each fault condition was simulated 100 times. The positioning accuracy rates for the fusion algorithm and the single-NCM algorithm are summarized in the table below:

Analysis of Table 9 reveals that as the number of node distortions increases, the localization accuracy of the NCM algorithm decreases. In contrast, the fusion algorithm consistently maintains high accuracy under varying fault locations and node distortion counts, demonstrating superior fault tolerance performance.

Table 9.

Comparison of the positioning accuracy of node classification algorithm and fusion algorithm.

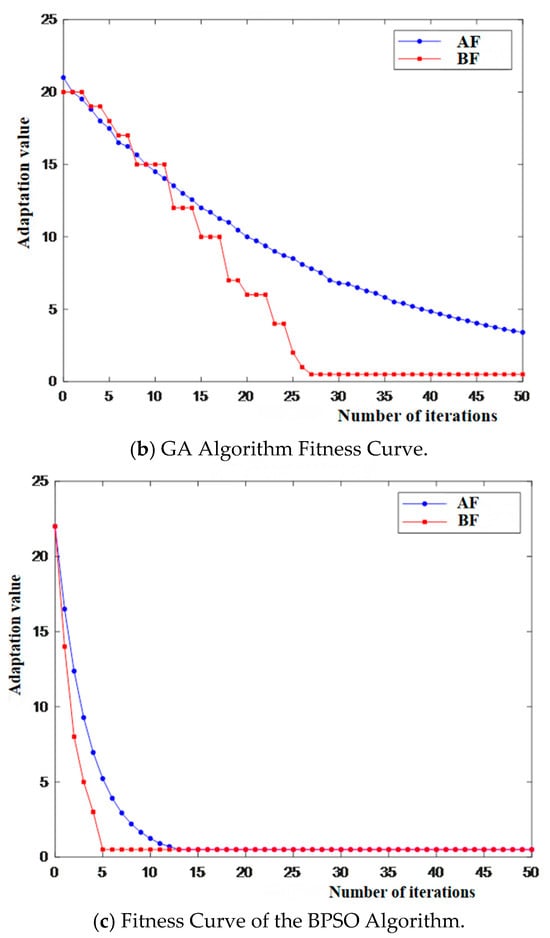

5.4. Effect Verification of the Improved Binary Particle Swarm Algorithm

To validate the effectiveness of the BPSO algorithm enhanced with genetic concepts introduced in this paper, simulations were conducted using the traditional genetic algorithm (GA) and the conventional BPSO algorithm for comparison with the IBPSO algorithm. The operational parameters are compared as shown in Table 10:

Table 10.

The operating parameters of GA, traditional BPSO and improved BPSO.

As shown in Table 10, the IBPSO algorithm demonstrates significantly superior speed compared to the GA algorithm during positioning, with performance nearly identical to the BPSO algorithm. In terms of positioning accuracy, the IBPSO algorithm achieves a higher accuracy rate than both the GA algorithm and the BPSO algorithm, reaching up to 95%.

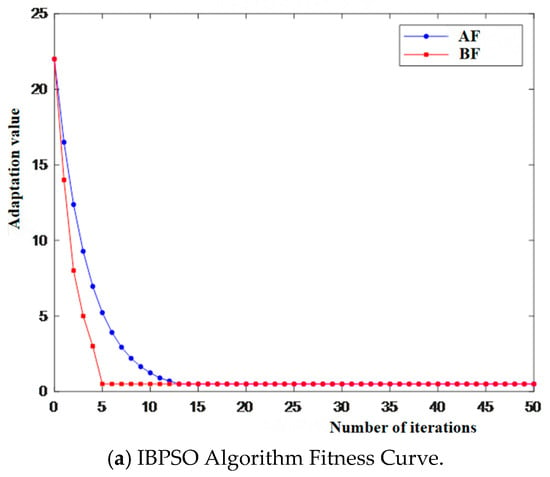

The minimum number of iterations required for each algorithm to find the optimal value is shown in Figure 9. The best fitness (BF) and average fitness (AF) achieved by each algorithm during simulation are shown in Figure 10a–c.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the number of optimization iterations of 3 algorithms.

Figure 10.

Fitness curves for 3 algorithms.

Analysis of Figure 9 reveals that the BPSO algorithm in this paper requires fewer iterations than both the GA algorithm and the BPSO algorithm in each simulation. Analysis of Figure 10 reveals that the BPSO algorithm is prone to becoming stuck in local minima throughout the fault location process, while the GA algorithm exhibits poor convergence. In contrast, the IBPSO requires fewer iterations and converges rapidly, making it more suitable for fault section location.

Overall, the IBPSO algorithm outperforms BPSO and GA algorithms in terms of iterative optimization, location efficiency, and positioning accuracy, thus demonstrating promising application prospects in fault section location.

6. Conclusions

In traditional methods of fault location for distribution network single-phase ground faults, there are several challenges such as difficulty in locating terminal sections, complex calculations in networks with intricate topologies, sensitivity to node information distortion, and the tendency to fall into local optima. To address these issues, this paper proposes a two-stage fault segment location method that integrates a node classification matrix with an IBPSO algorithm. Through theoretical derivation, simulation verification, and performance comparison, a complete solution with both innovation and engineering practicality is developed.

The node classification matrix designed in this paper is based on a dual-dimensional logic of “topological features + node status,” which breaks the limitations of traditional matrix-based algorithms that rely solely on topological information. This approach not only simplifies the calculation process under complex topologies but also significantly improves the accuracy of terminal section fault location, providing an efficient and reliable technical tool for rapid fault screening.

To address the drawback of the BPSO algorithm’s weak global search capability and its susceptibility to local optima, this paper introduces a genetic mutation mechanism and dynamic inertia weight strategy. The proposed improved IBPSO algorithm enhances particle diversity and balances exploration and exploitation capabilities. Even under scenarios with distorted node information, the algorithm can still stably converge to the optimal solution, providing strong support for error correction.

Based on the complementary characteristics of these two methods, this paper constructs a “node classification matrix for rapid initial location + IBPSO error correction” two-stage fusion architecture, successfully overcoming the traditional contradiction between “speed and robustness.” Multi-scenario simulation verification using the IEEE 33-node model shows that the fusion method maintains a fault location accuracy of over 95% in typical fault, node distortion, topology switching, and high-impedance fault scenarios, with the core scenario fault location accuracy reaching 96%, an improvement of 19% compared to the node classification matrix algorithm alone, and a 2% improvement over the IBPSO algorithm alone. Additionally, the average fault location time is only 16.1 ms, far better than the 202.5 ms of the pure IBPSO algorithm. The method does not require additional measurement devices and can directly integrate with the existing FTU system, quickly embedding into the actual distribution network dispatching platform. This reduces the time required for fault detection to isolation, accelerates system restoration, and improves the supply continuity and recovery speed of the distribution network under complex operating conditions.

Future work will focus on the following: building a high-distributed generation penetration active distribution network simulation platform to quantitatively verify the method’s impact on fault isolation time, supply restoration speed, and average outage duration; and expanding the method to handle multiple fault scenarios in active distribution networks to further enhance its engineering applicability. In summary, the proposed method provides a reliable technical solution for fault location in distribution networks. Its inherent advantages in speed, robustness, and topological adaptability lay a solid foundation for improving the fault handling performance of active distribution networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C., W.X. and Y.Y.; Methodology, K.C. and W.X.; Software, W.X. and Y.Y.; Validation, K.C., W.X. and Y.Y.; Formal analysis, K.C.; Investigation, W.X. and Y.Y.; Resources, K.C.; Data curation, W.X. and Y.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; Writing—review and editing, K.C.; Visualization, W.X. and Y.Y.; Supervision, K.C.; Project administration, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their quality reviews and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBPSO | Improved binary particle swarm optimization |

| FTU | Feeder Terminal Unit |

| BPSO | Binary Particle Swarm Optimization |

| NCM | Node Classification Matrix |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| GA | Traditional genetic algorithm |

| BF | Best fitness |

| AF | Average fitness |

References

- Pang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, F. Distribution network fault self-healing scheme based on network partition and flexible resource aggregation. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1538033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirmani, K.S.; Fernando, P.S.W.; Mahmud, A.M. Single line-to-ground fault current analysis for resonant grounded power distribution networks in bushfire prone areas. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 237, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.C.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhou, F.G.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Xiao, S.W. Fault Location Method for Active Distribution Network Based on Graph Kernels Attention Network. Mod. Electr. Power 2025, 42, 788–798. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, Q.; Yang, C.; Li, T. An Interphase Short-Circuit Fault Location Method for Distribution Networks Considering Topological Flexibility. Processes 2025, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wan, Z.; Zeng, X.; Liu, B. Real-Time Tracking of Fault Development and Faulty Feeder Identification Method for Resonant Grounding System Based on Transient Information During Arc Suppression. IET Gener. 2025, 19, e70136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, T.; He, Z.; Li, Y.; Cui, L. Topology identification of low-voltage distribution network nodes and dynamic adjustment of user nodes based on LSTM-GCN. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2026, 253, 112566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Yu, H.; Li, G.; Wu, H.; Chen, L.; Zou, S.; Ke, J.; Li, L. Fault Location Method of Distribution Network Based on FTU Information Comparison and Search. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1087, 032024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Liu, X.; Liang, R.; Tang, Z.; Ren, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Edge Computing Based Fault Sensing of the Distribution Cables Based on Time-Domain Analysis of Grounding Line Current Signals. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 4404–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, L.; Hou, S.; Ren, G.; Wang, W. A method for single-phase ground fault section location in distribution networks based on improved empirical wavelet transform and graph isomorphic networks. Information 2024, 15, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangbo, G. Fault Location Method of Distribution Network with Distributed Generation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2401, 012064. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, M.; Arabali, A.; Etezadi-Amoli, M. Fault Location in Distribution Networks by Compressive Sensing. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2015, 30, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinikia, M.; Talavat, V. Comparison of Impedance Based and Travelling Waves Based Fault Location Methods for Power Distribution Systems Tested in a Real 205-Nodes Distribution feeder. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2018, 19, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, A.; Madson, C. Fault location approach for distribution systems based on modern monitoring infrastructure. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou, G.; Biskas, P. Review and Comparison of Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization in the Optimal Power Flow Problem. Energies 2023, 16, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Qu, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, S.; Xiao, Q. A novel fault location method for the active distribution network based on dynamic quantum genetic algorithm. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 4719–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q. A novel method of fault line selection in low current grounding system using multi-criteria information integrated. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 209, 108010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Guo, W. Fault Line Selection Method for Power Distribution Network Based on Graph Transformation and ResNet50 Model. Information 2024, 15, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lu, B.; Lu, H. High-resistance grounding fault detection and line selection in resonant grounding distribution network. Electronics 2023, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. Domain Adversarial Graph Convolutional Network for Fault Diagnosis Under Variable Working Conditions. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Liu, X.; Fu, R.; He, B.; Shang, J. A Method for Fault Location in Distribution Networks Based on Graph Neural Networks and Improved Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Energy and Electrical Power Systems (ICEEPS), Guangzhou, China, 14–16 July 2024; pp. 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Fault Location Method for an Active Distribution Network Based on a Hierarchical Optimization Model and Fault Confidence Factors. Electronics 2023, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, A.O.; Sun, Y.; Gbadega, A.P. Coordination of smart inverter-enabled distributed energy resources for optimal PV-BESS integration and voltage stability in modern power distribution networks: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 10, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Qin, A.K.; Suganthan, P.N.; Baskar, S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaweera, A.; Halgamuge, S.K.; Watson, H.C. Self-organizing hierarchical particle swarm optimizer with time-varying acceleration coefficients. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2004, 8, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaiah, S.; Benidris, M.; Mitra, J. Reliability-Constrained Optimal Distribution System Reconfiguration. In Chaos Modeling and Control Systems Design; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Azar, A., Vaidyanathan, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 581. [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Quintero, J.; Orozco-Henao, C.; Bretas, A.S.; Velez, J.C.; Herrada, A.; Barranco-Carlos, A.; Percybrooks, W.S. Adaptive Fault Detection Based on Neural Networks and Multiple Sampling Points for Distribution Networks and Microgrids. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.