Abstract

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is widely used in food, pharmaceutical, and agricultural analyses but is highly susceptible to noise. To address this, we propose BiLSTM-FuseNet, a denoising framework that combines temporal modeling and explicit noise estimation. It uses stacked Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) layers for global–local spectral learning and an MLP branch to predict and subtract noise. Evaluated on the Tablet and AnHui soil datasets with various synthetic noise types, the model outperformed the conventional methods, achieving an RMSE of 0.024 and R2 of 0.68 under mixed noise. The downstream regression improved the tablet weight prediction R2 from 0.079 to 0.218. These findings demonstrate the robustness of BiLSTM-FuseNet and its clear advantages for practical downstream NIR applications.

1. Introduction

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS, 780–2500 nm) is widely applied in food, pharmaceutical, and agricultural analytics because its overtone and combination bands of O–H, C–H, and N–H functional groups provide molecular-level chemical information [1,2,3]. When combined with machine learning or deep learning algorithms, NIRS enables rapid, nondestructive prediction of fruit quality [4,5,6], tablet formulation properties [7], soil nutrients [8,9], and blood oxygen saturation [10]. However, the reliability of these applications critically depends on spectral quality, and real NIRS measurements are often contaminated by multiple noise sources.

Unlike images or standard time-series signals, NIR spectra contain long-range baseline structures, narrow absorption peaks, and weak interband correlations. Noise, therefore, acts destructively: light-source drift, detector thermal noise, sample scattering, and environmental fluctuations distort peak intensities and shift baselines, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and impairing chemical interpretability. In practical usage, even small perturbations near the absorption peaks can propagate to large errors in downstream regression or classification. Thus, spectral denoising is not merely a preprocessing step but a prerequisite for preserving chemically meaningful features and preventing cumulative degradation in subsequent models.

Classical preprocessing techniques, such as Savitzky–Golay smoothing [11], Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [12,13,14], Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) [15,16], and PCA-based denoising [17], employ fixed linear transformations and assume local smoothness or global stationarity. These assumptions hold only for mild, uniformly distributed noise. When disturbances are nonlinear, wavelength-specific, correlated, or mixed, these methods frequently oversmooth informative peak regions, distort the spectral morphology, and treat all wavelengths equally, even though chemically relevant signatures are concentrated in only a few bands.

Recent deep learning methods have improved denoising by capturing nonlinear dependencies. Autoencoders and their variants recover latent representations to reconstruct spectra [18,19,20,21], whereas convolutional autoencoders enhance local feature extraction from adjacent spectral windows [22]. Convolutional Neural Network–Long Short-Term Memory network (CNN–LSTM) hybrids further incorporate temporal modeling along the wavelength dimension to improve the robustness under structured noise [23]. Attention-based denoisers extend cross-band interactions, enabling global token communication and improved preservation of fine spectral structures [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Evidence from other sensing domains also supports this direction: graph-based neural models maintain robust gesture recognition from noisy 3D point clouds [30] and similar architectures outperform handcrafted methods in human motion modeling under uncertain sensor conditions [31]. These findings indicate that deep networks can extract noise-resilient structures from high-dimensional measurements, which is desirable for NIR spectral denoising.

However, these methods all perform denoising implicitly; noise suppression emerges only as a byproduct of minimizing the reconstruction error. This leads to two inherent limitations: (i) noise is never explicitly estimated or disentangled from the spectral signal, and (ii) reconstruction objectives penalize high-frequency deviations, causing oversmoothing of the chemically informative peaks.

In NIR analysis, peak distortion is substantially more harmful than baseline fluctuations because the peak amplitude and position encode functional group information. Implicit denoising models typically reduce MSE while degrading spectral interpretability and chemical utility. Furthermore, most supervised approaches require large corpora of paired clean–noisy spectra, which are rarely available for commercial NIR instruments. Real measurements included baseline drift, correlated noise, intensity fluctuations, and occasional wavelength failures. To avoid these issues, existing studies [8,32] commonly inject simplified Gaussian noise, which poorly approximates realistic multisource degradation patterns and fails to reflect spectral acquisition mechanisms.

To address these challenges, we constructed a controllable pseudo-supervised framework that generates paired training data by injecting synthetic noise into real spectra. We defined four representative perturbation types, constant, stripe, uniform, and correlated, each corresponding to typical degradation sources in NIRS: baseline shift, random intensity fluctuations, detector bandwise interference, and cross-band variations. Their intensities and distributions were parameterized for reproducible experiments across degradation levels. A hybrid configuration combines all four to emulate multisource contamination and serves as a stress test for model robustness.

Building on this framework, we propose BiLSTM-FuseNet, a denoising architecture tailored to the NIR spectral structure. Unlike conventional AE or LSTM architectures that indirectly suppress noise, BiLSTM-FuseNet performs explicit residual noise estimation: a lightweight MLP branch learns a nonlinear mapping from the input spectra to the noise component, which is subsequently subtracted from the original input. In parallel, a bidirectional LSTM backbone captures global wavelength continuity, whereas a convolution–Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) fusion path strengthens local spectral dependencies. This dual-path design enables the preservation of narrow functional absorption regions and the stabilization of broad baseline structures, yielding robust reconstructions even under mixed or correlated degradations. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- We introduce a multitype artificial noise-mixing strategy to simulate real-world composite noise conditions.

- We developed a spectral denoising training framework based on synthetically paired spectra that enables strong generalization to unseen noise types.

- We systematically evaluated the model performance under varying noise types and intensities and compared them with both traditional and deep learning-based baselines.

- The experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves a superior reconstruction performance in high-noise environments, thereby exhibiting strong practical applicability and research value.

2. Method

2.1. Synthetic Noise Framework

In real NIR acquisition, noise arises from distinct physical mechanisms rather than from a single Gaussian perturbation. To simulate realistic degradation, we designed a controllable synthetic noise framework that includes four representative types: constant, uniform, stripe, and correlated noise. These perturbations correspond to the baseline drift, random fluctuations, detector band interference, and cross-band variations, respectively, which occur widely in commercial NIR spectrometers.

Let denote the clean spectrum containing B wavelength bands.

2.1.1. Constant Noise

Constant noise is the addition of a fixed offset across the entire spectral range to simulate a uniform upward or downward shift in the full spectrum due to instrument bias, voltage drift, or dark-current drift.

where x represents the original clean spectrum, y represents the noise-added spectrum, denotes the noise-intensity uniformity across the spectrum, and is the independent Gaussian perturbation for each band of the spectrum.

2.1.2. Stripes Noise

Stripe noise simulates the phenomenon of periodic perturbations in the spectrum on a band-by-band basis, often found in scanning detectors or some CCD or CMOS sensors, and manifests itself as a perturbation that alternates in strength between odd and even bands.

where denotes the underlying Gaussian perturbation and denotes the imposed stripe noise vector, which has values only in some of the bands and 0 otherwise. denotes the set of selected stripe bands, and denotes the stripe noise term, which obeys a uniform distribution with an interval of .

2.1.3. Uniform Noise

Uniform noise represents the addition of independent uniformly distributed random perturbations to each band within a given interval, simulating, for example, near-uniformly distributed disturbances such as quantization errors, device jitter, and background light fluctuations.

where denotes the uniform noise spectrum on each band j, denotes the original clean spectrum on each band j, denotes the independent noise intensity on each band j, and denotes the Gaussian perturbation on each band j.

2.1.4. Correlated Noise

Correlation noise refers to the continuity or smoothness of the perturbation between several neighboring bands, usually caused by the thermal drift of the optical system, sample movement, optical path interference, background fluctuations, etc., with “crosstalk” characteristics.

The noise intensity in the above equation can be expressed as follows:

This indicates that the noise reaches the maximum value at band j = 0.5B, and then gradually attenuates to both sides. Where represents the control of the maximum noise disturbance, and represents the control of the distribution of noise in the spectral band; the smaller the value, the more noise is concentrated in the center near the band. A larger value indicates a wider noise distribution, which affects a larger number of spectral bands. denotes an element-by-element multiplication.

2.2. Low Dimensional Reconstruction Representation (LDR)

In near-infrared spectral data, spectral lines are typically highly redundant and strongly correlated, and noise is mostly high-frequency perturbations or local anomalies. Therefore, mapping the original spectral lines into a low-dimensional space for feature extraction and reconstruction can effectively compress invalid information and smoothen the noise interference. This concept has been widely used in spectral denoising modeling. Suppose that the input noise spectrum is , and contains B spectral bands.

2.2.1. PCA Denoiser

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a linear dimensionality reduction method that projects a high-dimensional spectrum into a low-dimensional subspace by finding the direction of maximum variance, keeping only the first k principal components for reconstruction.

where is a projection matrix consisting of the first k principal components.

2.2.2. Autoencoder

An autoencoder is a typical encoding–decoding network structure in which the original spectrum is first mapped into a low-dimensional space by encoding to achieve noise suppression, and then the clean spectrum is reconstructed by a decoder. The autoencoder can be represented as

where denotes a fully connected feedforward neural network that acts as an encoder structure. denotes a decoder that uses a fully connected feedforward neural network that compresses the representation to reconstruct the original spectrum.

2.2.3. CNN Denoiser

Convolutional neural network (CNN) extracts spectral pattern information within a local window by stacking locally aware convolutional kernels. It automatically captures spectral band continuity and is suitable for local noise suppression and efficient modeling of spectra. The CNN denoiser is similar to an autoencoder and contains an encoder and a decoder.

where denotes a one-dimensional convolution that is used as an encoder to downscale and extract the local features. denotes the decoder that compresses the representation to reconstruct the original spectrum.

2.2.4. BiLSTM Denoiser

Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) [33] captures long-range nonlinear correlations by modeling the sequence dependence of spectral lines in both forward and backward directions. BiLSTM is particularly suitable for processing continuous spectra and is more robust to sequence anomalies, such as systematic noise and streak interference.

In the denoising task, the BiLSTM Denoiser also uses an encoding–decoding structure.

where denotes the bidirectional long- and short-term memory network, which is used as an encoder to downscale and capture global correlations between the spectral bands. denotes the decoder that compresses the representation to reconstruct the original spectrum.

2.3. Proposed Method

2.3.1. Architecture Overview

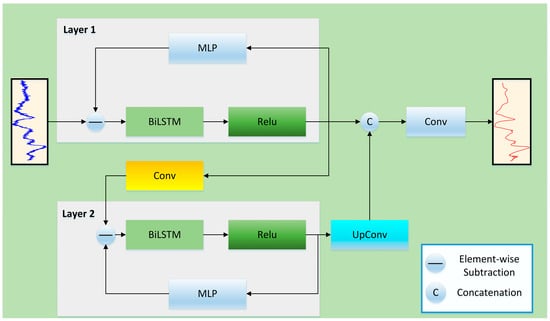

We propose a novel network architecture called BiLSTM-FuseNet, which is illustrated in Figure 1. BiLSTM-FuseNet consists of three parallel branches: a global context modeling branch, residual noise estimation branch, and local feature extraction branch.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet for spectral denoising, consisting of a global context branch, a residual noise-estimation branch, and a local feature-extraction branch.

The global context modeling branch employs a BiLSTM encoder to capture long-range dependencies across the spectral dimensions. Unlike CNN-based encoders, which model only local neighbors, BiLSTM processes the spectral sequence bidirectionally, enabling the network to aggregate information from both the preceding and succeeding wavelength bands. Furthermore, ReLU activation acts as an implicit sparsification mechanism that suppresses weak or noisy activations and retains only salient spectral responses. This selective activation reduces redundancy and facilitates noise filtering at the representational level.

The residual noise estimation branch (MLP module) learns the underlying noise distribution, thereby reducing the burden of the reconstruction module.

The local feature extraction branch focuses on the fine-grained spectral structures. First, a convolutional downsampling module (stride = 2) was used to reduce the feature resolution, which effectively captured high-frequency variations while suppressing trivial local fluctuations. Through the subsequent upsampling process, the branch reconstructs the low-frequency components and merges them with the preserved high-frequency features, enabling the model to recover subtle peak–valley patterns in the spectra. Finally, a lightweight convolutional decoder was applied to refine the local details while preserving the original spectral resolution.

2.3.2. Global Context Branch

We assume that the noisy input spectrum is an . To normalize the spectral values, we first apply min–max normalization as follows:

where represents the minimum value of the input spectrum across all spectral bands and denotes its maximum value.

The normalized spectrum was then fed into a bidirectional LSTM to model the global contextual dependencies across the spectral bands, resulting in the following feature representation:

where N denotes the batch size, B the number of spectral bands, and H the hidden size of each unidirectional LSTM.

The initial features are then obtained by applying ReLU activation, as follows:

2.3.3. Residual Noise Estimation Branch

To further enhance the model’s ability to capture noise patterns, we introduce a residual iterative mechanism based on MLP and LSTM. In each iteration, the current feature is first passed through an MLP network to generate a new noise estimation, which is then fed into a BiLSTM to obtain the corresponding dynamic compensation term :

We updated the feature representation using the residual formulation, as follows:

This process was repeated for K iterations to produce the final feature , which served as the output of the first stage. This representation retains the original global contextual information, while incorporating a certain degree of noise suppression.

2.3.4. Local Feature Extraction Branch

To further capture the local structural information between adjacent spectral bands, we applied a downsampling operation to the output of the first stage. The second layer shares a similar structure to the first but is additionally equipped with a downsampling convolution and an upsampling transposed convolution module based on BiLSTM.

First, we downsampled the output feature using a 1D convolution.

After the BiLSTM and residual iterations, we upsampled the resulting feature using a 1D transposed convolution:

where denotes the output feature from the BiLSTM in the downsampling branch and H represents the hidden size of each unidirectional LSTM.

2.3.5. Feature Fusion and Decoding

The global features from the first layer and local features from the second layer were concatenated along the channel dimension to achieve multi-scale feature fusion. A convolutional decoder was then applied to integrate this information and reconstruct the denoised spectral signal. The fused features are expressed as follows:

Then, we applied a two-layer 1D convolutional decoding operation as follows:

The first convolution uses a 3 × 1 kernel (with padding = 1) to reduce the number of channels from 3H to H; denotes the activation function, and the second convolution uses a 1 × 1 kernel to further compress the channels from H to 1 to produce the final reconstructed spectrum.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Settings

3.1.1. Dataset

Pharmaceutical tablet dataset [34]: This study utilized the tablet dataset, which consists of 654 pharmaceutical tablets. This dataset was excellent for chemometric training and algorithm testing. The measured spectral wavelength range was 600–1898 nm and the resolution was 2 nm. Each sample was labeled according to its weight, hardness, and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). This dataset is available at https://eigenvector.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/nir_shootout_2002.mat_.zip (accessed on 26 May 2025).

Anhui-NIR-Soil Dataset [8]: The soil spectral dataset used in this study was the Anhui-NIR-Soil Dataset, which was mainly collected from Huangshan and Shitai counties in southern Anhui Province, China. The dataset was designed to support urban soil environmental quality monitoring and provide basic data on soil functionality and environmental conditions for sustainable development in the Anhui Province. Soil samples were collected using the “five-point diagonal sampling method,” where each sample point was taken from a depth of 0–20 cm, and five points were combined into one composite sample. A total of 188 composite samples were collected from this dataset, each weighing approximately 1.5 kg. The collected soil samples were air-dried, pulverized, and screened through a 20-mesh screen in the laboratory to obtain the required particle size. Each sample was then subjected to near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopic scanning and a series of chemical property measurements to form a structured dataset. The near-infrared (NIR) spectral range for each sample in this dataset was 901.57 nm–1701.18 nm, totaling 228 bands. The nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content of each sample was measured.

3.1.2. Implementation Details

The training configuration and the detailed synthetic noise models used in the experiments are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. We used a 4-fold cross-validation method to partition the pharmaceutical tablet and Anhi-NIR-Soil datasets. The batch size was 32, the training period was 1000, the optimizer was AdamW, the initial learning rate was 0.001, and learning rate scheduling was performed using CosineAnnealing. All experiments were implemented in PyTorch running on Python 3.10.

Table 1.

Training configuration for all experiments, including batch setup, optimization strategy, learning-rate scheduling, and loss function used during model learning.

Table 2.

Synthetic noise configurations used in the denoising experiments, listing the parameterization and descriptions of constant, uniform, stripe, correlated, and mixed noise types.

For synthetic noise generation, σ was used to control the intensity of the constant and uniform noise. Stripe noise was injected into 33% of the spectral bands, and 5–15% of the samples were corrupted with stripe artifacts. The stripe amplitude followed a fixed uniform distribution, , whereas the other stripe-related parameters were kept constant. σ only controls the standard deviation of the additive Gaussian noise applied to the contaminated spectral bands. For correlated noise, σ is defined as the absolute value of parameters β and η. We fixed η at 0.15 and varied β to adjust the correlated noise strength. Mixed noise simultaneously included all four types, and σ represents the global mixed-noise level. For example, when σ = 0.1, the spectra contained constant noise with intensity 0.1, uniform noise sampled from , stripe noise with amplitude 0.1, and correlated noise with β = 0.1. The effective perturbation is approximately four times the magnitude of the single-noise setting.

It should also be noted that the clean spectra used in training and evaluation are not strictly noise-free in a physical sense but represent the closest available approximations to noise-reduced ground truth.

3.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

The average MSE is used as the loss during the training process. SNR, RMSE, R, and were used as the denoising model evaluation metrics. The SNR was used to measure the signal-to-noise ratio between the model outputs and reference spectra, with larger values indicating better noise suppression and spectral line reduction. The RMSE was used to evaluate the average reconstruction error between the reconstructed and real spectra, with smaller values indicating better spectral line reduction. The RMSE is used to evaluate the average reconstruction error between the reconstructed spectrum and the real spectrum; the smaller the value, the better is the spectral line restoration. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the linear correlation between the reconstructed spectrum and the real spectrum; the closer it was to 1, the better the spectral line restoration effect. The coefficient of determination indicates the extent to which the model output explains the variations in the real spectrum. A value of zero or negative indicated that the reconstructed spectrum failed completely. Positive values and values closer to 1 indicate a better spectral line reduction.

The formulas for calculating the MSE loss and the assessment indicators are as follows:

where denotes the true spectral intensity value of the ith sample in the jth band, denotes the reconstructed spectral value of the ith sample in the jth band, denotes the true spectral value of all samples in the jth band, denotes the predicted spectral value of all samples in the jth band, denotes the mean of the true spectra in all bands, denotes the mean of the predicted spectra, N denotes the number of samples, and B denotes the number of spectral bands. In the correlation coefficient R, represents the covariance between the reconstructed and true spectra, and denote their variances.

To validate the effectiveness of the spectral lines after denoising, we used a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to predict the target attributes in the downstream task. Regression performance was evaluated using RMSE, R, and . The formula for calculating the downstream evaluation metrics is as follows:

where N denotes the total number of test samples, denotes the true label value of the ith sample, denotes the model-predicted value of the ith sample, and denotes the average value of all the true labels. In the correlation coefficient R, represents the covariance between the predicted and true values, whereas and denote their variances.

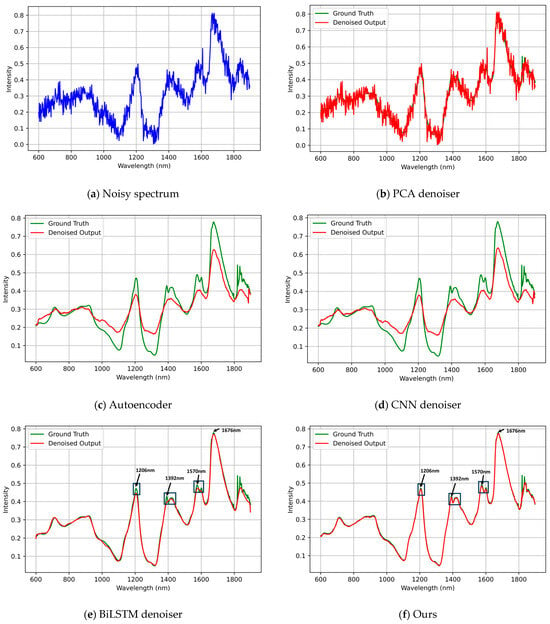

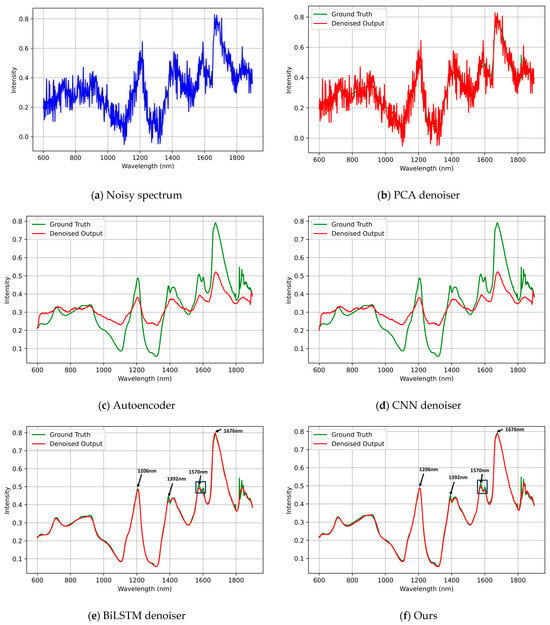

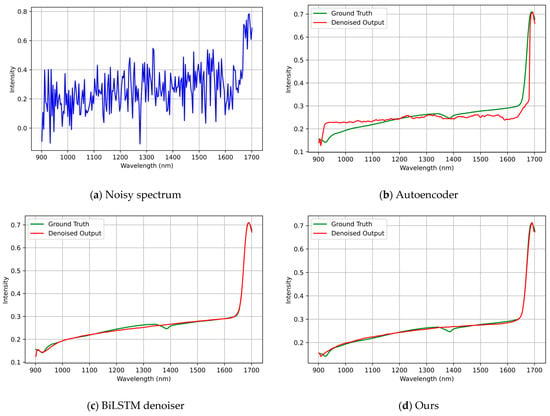

3.2. Visualization of Denoising Results Under Synthetic Noise

To visually evaluate the denoising capability of the different methods, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the reconstructed spectra under three representative scenarios: constant noise, mixed synthetic noise, and mixed noise from the Anhui-NIR-Soil dataset. In Figure 2 and Figure 3, five denoising approaches are included—PCA denoiser, Autoencoder, CNN denoiser, BiLSTM denoiser, and the proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet—allowing a comprehensive comparison across different noise conditions. In contrast, Figure 4 displays only three representative models (Autoencoder, BiLSTM denoiser, and BiLSTM-FuseNet), as additional methods yield visually redundant spectral curves and do not provide meaningful insight for comparative analysis.

Figure 2.

Visual comparison of reconstructed spectra under constant noise (σ = 0.5) using the Pharmaceutical Tablet dataset. Subplots show (a) noisy input spectrum; (b) PCA-based denoiser; (c) autoencoder; (d) CNN denoiser; (e) BiLSTM denoiser; and (f) our BiLSTM-FuseNet. Ground-truth spectra are plotted in green and denoised results in red. This figure provides a qualitative comparison of spectral reconstruction, while quantitative performance differences (including statistical significance) are reported in Table 3. The proposed model better preserves peak–valley structures and local absorption features (e.g., around 1206 nm, 1392 nm, and 1570 nm), while other methods tend to oversmooth or distort these regions.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of reconstructed spectra under mixed noise (σ = 0.5) using the Pharmaceutical Tablet dataset. Subplots show (a) noisy input spectrum; (b) PCA-based denoiser; (c) autoencoder; (d) CNN denoiser; (e) BiLSTM baseline; and (f) our BiLSTM-FuseNet. Ground-truth spectra are plotted in green and denoised results in red. This figure provides a qualitative comparison of spectral reconstruction. Compared to conventional methods that exhibit peak distortion or oversmoothing, the proposed model preserves sharp absorption peaks (around 1570 nm) and maintains global spectral trends.

Figure 4.

Visual comparison of reconstructed spectra under mixed noise (σ = 0.5) using the Anhui-NIR Soil dataset. (a) noisy spectrum; (b) autoencoder; (c) BiLSTM denoiser; (d) our BiLSTM-FuseNet. Ground-truth spectra are plotted in green and denoised results in red. This figure provides a qualitative comparison of spectral reconstruction. The proposed model provides the closest reconstruction to the ground truth, better preserving the global spectral trend while suppressing large fluctuations introduced by mixed noise.

From Figure 2, it can be observed that PCA denoising fails to reconstruct the spectral profile and leaves a considerable amount of residual noise. Autoencoder- and CNN-based denoisers suppress large fluctuations but oversmooth the signal, causing the loss of the characteristic absorption peaks. The BiLSTM denoiser captures most of the peak structures; however, compared with our proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet, it exhibits weaker reconstruction fidelity in chemically meaningful regions, particularly at approximately 1206, 1392, 1570, and 1676 nm. These wavelength regions are closely associated with fundamental physicochemical absorptions in the NIR domain: 1200–1400 nm corresponds to the overtone absorption of C–H and N–H bonds; 1400–1600 nm corresponds to the second overtone of O–H stretching; and 900–1100 nm is influenced by polysaccharide-related scattering and matrix effects. In contrast, BiLSTM-FuseNet preserves both the global spectral trend and fine peak–valley structures in these chemically relevant regions, indicating that global temporal modeling combined with local feature extraction enables the network to recover physically meaningful spectral information rather than merely smoothing noise.

As shown in Figure 3, the mixed-noise setting introduced both amplitude perturbations and structured distortions, making the reconstruction task more challenging. Principal component analysis (PCA) and convolutional neural network (CNN)-based denoisers primarily suppress low-frequency fluctuations and fail to recover the chemically relevant peaks. The BiLSTM denoiser restores the overall spectral trend but attenuates feature bands within 1400–1600 nm (second overtone of O–H stretching), which are crucial for characterizing excipient composition and hydration. In contrast, BiLSTM-FuseNet preserved both the peak height and valley curvature in these regions, indicating superior retention of O–H molecular signatures and other physicochemical structures. This suggests that combining global bidirectional modeling with local feature extraction enables the network to retain chemically meaningful spectral responses, rather than smoothing them as noise.

For the Anhui-NIR-Soil dataset in Figure 4, the spectra contained very few sharp peaks and primarily exhibited smooth broadband variations. In this case, the autoencoder tends to oversmooth the curve and deviates noticeably from the reference. By contrast, both the BiLSTM denoiser and BiLSTM-FuseNet maintained the overall spectral shape well. Overall, BiLSTM-FuseNet provides the closest match to the ground truth, reflecting a better preservation of the global spectral trend.

In conclusion, BiLSTM-FuseNet is the most consistent with the ground truth, as shown in the next step, which can infer better retention of the global spectral trend of the region to a greater extent. Collectively, these visual results support that the proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet not only suppresses noise but also preserves chemically informative spectral structures and is superior to the other methods that smooth or approximate the spectral curve.

Table 3.

Reconstruction performance comparison of different denoising methods under various noise types (Tablet dataset; values reported as mean ± standard deviation).

Table 3.

Reconstruction performance comparison of different denoising methods under various noise types (Tablet dataset; values reported as mean ± standard deviation).

| Noise | Input SNR | Method | RMSE ↓ | Output SNR ↑ | Pearson R ↑ | R2 ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant (σ = 0.5) | 0.65 ± 0.01 | PCA | 0.180 ± 0.001 ‡ | 1.92 ± 0.02 ‡ | 0.661 ± 0.003 ‡ | – |

| AutoEncoder [20] | 0.097 ± 0.000 ‡ | 3.44 ± 0.05 ‡ | 0.787 ± 0.003 ‡ | – | ||

| BiLSTM [23] | 0.031 ± 0.002 † | 14.79 ± 1.34 † | 0.987 ± 0.002 † | 0.44 ± 0.14 | ||

| Ours | 0.026 ± 0.001 | 18.44 ± 0.56 | 0.992 ± 0.000 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | ||

| Stripes (σ = 0.5) | 0.64 ± 0.01 | PCA | 0.181 ± 0.001 ‡ | 1.92 ± 0.03 ‡ | 0.656 ± 0.004 ‡ | – |

| AutoEncoder | 0.097 ± 0.001 ‡ | 3.41 ± 0.07 ‡ | 0.782 ± 0.005 ‡ | – | ||

| BiLSTM | 0.030 ± 0.002 † | 15.04 ± 1.14 † | 0.988 ± 0.003 | 0.49 ± 0.11 | ||

| Ours | 0.025 ± 0.001 | 18.44 ± 0.23 | 0.992 ± 0.000 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | ||

| Uniform (σ = [0, 0.5]) | 1.12 ± 0.02 | PCA | 0.104 ± 0.001 ‡ | 3.37 ± 0.06 ‡ | 0.834 ± 0.002 ‡ | – |

| AutoEncoder | 0.053 ± 0.001 ‡ | 6.20 ± 0.13 ‡ | 0.940 ± 0.001 ‡ | – | ||

| BiLSTM | 0.023 ± 0.002 ‡ | 18.65 ± 0.84 ‡ | 0.993 ± 0.001 † | 0.71 ± 0.03 † | ||

| Ours | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 22.22 ± 0.43 | 0.995 ± 0.000 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | ||

| Correlated (β = 0.5, η = 0.15) | 1.05 ± 0.02 | PCA | 0.124 ± 0.001 ‡ | 2.80 ± 0.05 ‡ | 0.785 ± 0.002 ‡ | – |

| AutoEncoder | 0.062 ± 0.001 ‡ | 5.38 ± 0.10 ‡ | 0.918 ± 0.001 ‡ | – | ||

| BiLSTM | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 23.08 ± 2.60 | 0.995 ± 0.001 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | ||

| Ours | 0.015 ± 0.000 | 27.14 ± 0.86 | 0.997 ± 0.000 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | ||

| Mix (σ = 0.5) | 0.39 ± 0.01 | PCA | 0.299 ± 0.001 ‡ | 1.16 ± 0.02 ‡ | 0.473 ± 0.004 ‡ | – |

| AutoEncoder | 0.123 ± 0.001 ‡ | 2.70 ± 0.03 ‡ | 0.618 ± 0.006 ‡ | – | ||

| BiLSTM | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 15.60 ± 0.44 † | 0.989 ± 0.001 † | 0.41 ± 0.04 | ||

| Ours | 0.033 ± 0.002 | 16.24 ± 0.67 | 0.990 ± 0.001 | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

Note: ↑ indicates that higher values represent better performance, and ↓ indicates that lower values represent better performance. † and ‡ indicate statistically worse performance than that of the proposed method (Ours/BiLSTM-FuseNet) under the same conditions (paired Student’s t-test; † p < 0.05, ‡ p < 0.01). Bold values indicate the best mean performance under each noise condition.

3.3. Robustness Evaluation Under Different Noise Types and Intensities

The visual observations in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 indicate that BiLSTM-FuseNet better preserves chemically meaningful peak–valley structures, especially under mixed and correlated noise. To statistically validate these observations, we conducted a comprehensive quantitative comparison across different noise types and intensities, as summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. In our proposed model, the number of residual iterations K was set to 12 for the Pharmaceutical Tablet Dataset and 6 for the Anhi-NIR-Soil Dataset.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of denoising methods under different mixed noise levels on the Tablet dataset (all metric values shown by mean ± standard deviation).

Table 5.

Performance comparison of denoising models under different mixed noise levels on the Anhui-NIR-Soil dataset (all metric values shown by mean ± standard deviation).

Table 3 reports reconstruction performance on the Tablet dataset across five noise types. Overall, our BiLSTM-FuseNet achieved the lowest RMSE and the highest SNR and R2 in all settings, significantly outperforming PCA and AutoEncoder (paired Student’s t-test p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). Under constant and stripe noise, PCA fails to reconstruct meaningful spectral profiles, whereas BiLSTM-FuseNet maintains RMSE around 0.025–0.026 and SNR around 18.4 dB, indicating strong resistance to baseline shift and localized perturbations. For correlated noise (β = 0.5), the advantage becomes more pronounced: SNR = 27.14 for Ours vs. 23.08 for BiLSTM and 5.38 for AutoEncoder, demonstrating superior modeling of cross-band dependencies. In the mixed-noise condition, PCA and AutoEncoder collapse (negative R2), whereas BiLSTM and BiLSTM-FuseNet remain stable. Notably, only BiLSTM-FuseNet retains positive R2, with a Pearson correlation of approximately 0.64, indicating that its reconstructed spectra remain chemically consistent rather than being merely smoothed waveforms.

Table 4 compares the denoising performances of the different methods with increasing mixed noise intensity. BiLSTM-FuseNet consistently outperformed PCA and AutoEncoder across all noise levels, with statistically significant improvements in RMSE, SNR, and R2 (paired Student’s t-test, p < 0.05). Compared with the BiLSTM baseline, the advantage of the BiLSTM-FuseNet is noise-dependent. At low noise levels (σ = 0.1–0.25), both models achieved comparable performance, and no statistically significant difference was observed. As the noise intensity increases (σ ≥ 0.5), BiLSTM-FuseNet demonstrates a significantly lower RMSE and higher SNR/R2 (p < 0.05), while the BiLSTM baseline begins to deteriorate, particularly at σ = 1.0, (R2 = 0.07). These results indicate that the proposed dual-path architecture not only suppresses random noise but also retains chemically meaningful spectral structures under challenging noise conditions, where recurrent reconstruction alone becomes unstable.

To evaluate the cross-dataset generalization, mixed-noise experiments with varying intensities were performed on the Anhui NIR-Soil dataset (Table 5). Under mild noise (σ = 0.1), all models achieved comparable performance, and the differences between AutoEncoder, CNN, BiLSTM, and BiLSTM-FuseNet were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating that low-level perturbations can be handled by standard reconstruction models. As the noise increases (σ = 0.25–0.50), the PCA-derived and convolutional baselines begin to degrade rapidly: the R2 of AutoEncoder drops from 0.73 to 0.15, and CNN from 0.73 to 0.15, implying that latent compression alone fails to preserve the spectral structure. In contrast, the BiLSTM baseline remained stable in this range, and BiLSTM-FuseNet achieved the best reconstruction with statistically significant improvements in SNR and R2 over both AutoEncoder and CNN (p < 0.05). When noise becomes severe (σ ≥ 0.75), shallow methods collapse completely: CNN and AutoEncoder produce negative R2 values and a very low output SNR (<4 dB), indicating structural reconstruction failure. The BiLSTM baseline maintained partial recovery capability, but its performance deteriorated at σ = 1.0 (RMSE = 0.064, R2 = 0.27). In comparison, BiLSTM-FuseNet achieved the lowest RMSE and highest SNR/R2 across all noise intensities and remained effective even at σ = 1.0 (R2 = 0.29), where all other models failed. This result demonstrates that explicit residual noise modeling and hierarchical feature fusion substantially improve the denoising robustness under strong spectral degradation.

Overall, BiLSTM-FuseNet demonstrated noise-dependent superiority: performance differences were negligible under mild noise but became statistically significant at medium and high noise levels, indicating that the proposed dual-path architecture is particularly effective in heavily degraded spectral conditions.

3.4. Ablation Studies

3.4.1. Study on Encoder Replacement in BiLSTM-FuseNet

However, to understand how BiLSTM-FuseNet outperforms the baseline denoisers with respect to reconstruction accuracy and statistical robustness, we performed an ablation study involving systematic variation in the encoder design. We replaced the BiLSTM encoder with different backbone networks, while keeping all the training and optimization settings the same. The performance differences are listed in Table 6. Under constant noise (σ = 0.5), GRU and BiLSTM achieve the lowest reconstruction error (RMSE = 0.025), while BiLSTM obtains the highest output SNR (19.09 dB vs. 19.03 dB for GRU), indicating that bidirectional sequence modeling offers a slight but consistent advantage in preserving local spectral transitions. The superiority was not statistically significant at this noise level (p > 0.05), suggesting that simple recurrent units can handle uniform perturbations when the noise structure remains homogeneous.

Table 6.

Ablation study of different encoder backbones under constant and mixed noise conditions (Tablet dataset; values reported as mean ± standard deviation).

When the noise became more heterogeneous (Mix, σ = 0.5), the differences across encoders became statistically meaningful (p < 0.05). BiLSTM achieved the best reconstruction across all metrics (RMSE = 0.034, SNR = 16.32 dB, R2 = 0.39), outperforming unidirectional recurrent models and transformer-based encoders. These results suggest that bidirectional dependency modeling is more tolerant to structured noise because it retains cross-band relationships that are degraded in unidirectional recurrent or attention-based encoders.

Although the encoder comparison clarifies the performance advantage of BiLSTM in complex noise scenarios, it is also necessary to consider whether such benefits incur computational or deployment costs. From Table 7, we observe that lightweight baseline models such as AutoEncoder and CNN denoiser have extremely small parameter sizes (6.0 K and 31.0 K) and sub-millisecond latency, indicating their suitability for resource-limited environments. However, their limited capacity limits their ability to recover complex spectral structures. In contrast, recurrent architectures provide stronger temporal dependency modeling, yet their sequential computation causes a noticeable increase in latency (e.g., BiLSTM denoiser: 134.0 K parameters and 46.31 ms). FuseNet-based variants further increase complexity because of multi-branch feature fusion. Although Transformer-FuseNet achieves a favorable balance between the model size (116.6 K) and inference speed (18.21 ms), recurrent versions, particularly BiLSTM-FuseNet, exhibit the highest computational cost (204.0 K parameters and 474.12 ms), as bidirectional recurrence cannot be efficiently parallelized. Nevertheless, this complexity correlates with a consistently superior denoising performance across all noise conditions, reflecting the benefit of enhanced spectral dependency modeling. All latency measurements were performed on an Intel Core i7-12700K CPU with a batch size of 1, representing simplified real-time inference rather than an optimized GPU execution. If practical deployment requires a trade-off between denoising accuracy and throughput, Transformer-FuseNet provides a reasonable compromise.

Table 7.

Comparison of parameter size and inference latency among baseline denoisers and FuseNet-based variants. Latency was evaluated on an Intel Core i7-12700K CPU with batch size = 1.

3.4.2. Comparison of K Values Across Iterations

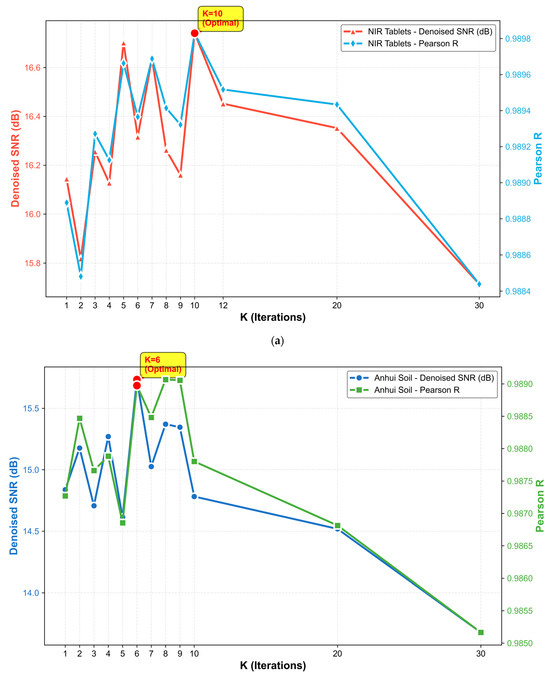

Beyond the encoder choice, the denoising behavior of BiLSTM-FuseNet is also affected by the refinement depth of the residual module, which is controlled by the iteration number K. To study this effect, we conducted experiments on two representative NIR datasets with different intrinsic spectral characteristics. Although the same mixed-noise configuration was applied, the model responses varied substantially across datasets. As shown in Figure 5, the model shows only minor improvement at small iteration counts, whereas both SNR and Pearson R increase steadily as K increases, indicating that multistage refinement progressively suppresses stochastic perturbations and restores the spectral structure.

Figure 5.

Influence of iteration number K on denoising performance, evaluated by the cross-validation mean of SNR and Pearson’s R (four folds). (a) Pharmaceutical Tablet dataset; (b) Anhui-NIR Soil dataset.

For the Tablet dataset, the model achieves optimal performance at K = 10, where the denoised SNR reaches its maximum and the Pearson R is also near its peak. Beyond this point, an increase in the number of iterations led to degradation. This suggests that moderate refinement helps recover the local spectral features of pharmaceutical samples (e.g., water-related or functional group absorption peaks), whereas excessive iterations introduce oversmoothing, thereby attenuating subtle yet meaningful spectral structures.

By contrast, the Anhui soil dataset attained its optimal iteration count at approximately K = 6. Soil spectra primarily exhibit slowly varying broadband patterns with fewer sharp absorption peaks; therefore, fewer iterations are required to restore the dominant structures. Additional iterations tend to oversmooth the spectra and diminish informative details.

Overall, the denoising iteration number exhibited a clear “overfitting” effect: moderate iterations removed noise and reinforced key spectral features, whereas excessive refinement destroyed local absorption structures, causing simultaneous declines in both SNR and Pearson R. Hence, the optimal value of K is closely tied to the intrinsic spectral characteristics of the dataset and should be adaptively determined for different tasks.

3.5. Comparison of Denoising Performance Under Synthetic and Real Noise

The ablation studies presented in Section 3.4 show that denoising behavior in BiLSTM-FuseNet relies on architectural design, refinement depth, and encoder selection. However, all prior evaluations were performed under controllable synthetic noise, where the degradation was analytically defined and followed idealized assumptions. We then evaluated the model using real acquisition noise from repeated spectra obtained from two commercial NIR spectrometers to assess the applicability of these advantages under real measurements.

Specifically, the Pharmaceutical Tablet dataset was acquired using two NIR spectrometers manufactured by Foss (USA) [34]. We extracted the real measurement noise from the differences between the measurements of the same samples obtained by the two instruments. The extraction process consisted of (i) normalizing both datasets to the same range, (ii) computing the measurement differences of identical samples across the two spectrometers, (iii) removing systematic inter-instrument bias by subtracting the mean difference at each wavelength, and (iv) treating the remaining residuals as real acquisition noise.

To ensure a fair comparison, we first injected synthetic noise (five types) into the clean spectra and treated it as the reference degradation level.

Then, the amplitude of the real instrument noise extracted from repeated measurements was scaled by a factor α so that the resulting noisy spectra reached the same SNR level as the synthetic noise:

where was iteratively adjusted until

This procedure guarantees that the two noise sources are evaluated under matched noise severity while preserving the statistical structure of real noise (non-Gaussianity, wavelength correlation, spectral drift, etc.).

From Table 8, we observe that, under a matched noisy SNR, the model generally achieves a higher denoised SNR and R2 under synthetic noise. In contrast, the performance under real noise is relatively low, which indicates that the mismatch between the synthetic noise distribution and real instrument noise leads to a more challenging denoising problem. Nevertheless, the model consistently improved the SNR under all real-noise settings, confirming that BiLSTM-FuseNet remains effective for practical acquisition noise and provides tangible engineering value in real deployment scenarios.

Table 8.

Denoising performance under different noise types using SNR-aligned synthetic noise and scaled real noise (Tablet dataset; values reported as mean ± standard deviation).

3.6. Model Sensitivity to Spectral Peaks and Characteristic Bands

Real instrument noise is inherently more complex than synthetic perturbations, and BiLSTM-FuseNet can restore meaningful spectral structures under such conditions. However, the denoising performance in spectroscopy cannot be fully assessed using global metrics alone, because RMSE, SNR, and R2 evaluate the overall fidelity but do not reveal whether the model preserves chemically informative features. In near-infrared spectra, functional information is concentrated in absorption peaks that correspond to molecular vibrations, whereas most non-peak intervals reflect the baseline drift or matrix background. A denoising model can achieve high global accuracy while unintentionally smoothing peak amplitudes, shifting peak positions, or degrading narrow absorption bands.

To examine whether BiLSTM-FuseNet captures chemically relevant regions rather than uniformly smoothing noise, we analyzed its spectral sensitivity from two complementary perspectives: (1) the relative attention allocation between peak and non-peak spectral regions and (2) the internal feature sampling behavior of the convolutional extraction branch.

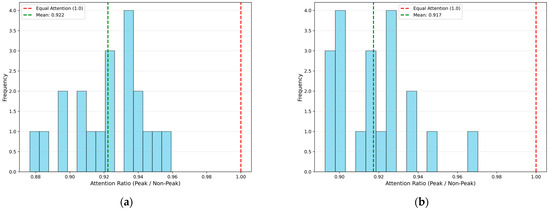

3.6.1. Comparative Response Analysis Between Peak and Non-Peak Regions

The peak regions contain chemically informative spectral signatures, and the BiLSTM naturally exhibits an implicit attention-like mechanism that can be trained to process such features. We first trained a BiLSTM-FuseNet model on mixed-noise spectra with an SNR of 0.39 (σ = 0.5) without applying any weighting between the peak and non-peak regions. The peak-to-non-peak attention ratio was then evaluated for the 20 samples, as shown in Figure 6a. Under the same conditions, we further trained another BiLSTM-FuseNet model, in which the loss of peak regions was weighted three times higher than that of non-peak regions. The peak-to-nonpeak attention ratio was evaluated for the same 20 samples, and the results are shown in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Peak-to-non-peak attention ratio distribution of BiLSTM-FuseNet. (a) Without peak weighting; (b) peak regions weighted × 3. The ratios for most spectral bands cluster close to 1.0 in both cases, indicating that attention remains nearly uniform across peak and non-peak regions even when peak-region loss is explicitly emphasized.

For both models, the attention ratio was less than and approached 1, indicating that the model devoted slightly more attention to non-peak regions, although the difference was small. During the denoising training process, the supervision targets are clean spectra; therefore, the model focuses on reconstructing a globally consistent spectrum rather than prioritizing any specific peak band, as is necessary in downstream prediction tasks. In pure denoising, the model emphasizes the global spectral characteristics. Even when the peak regions are explicitly up-weighted, the learned attention ratio converges toward a uniform distribution.

These results clearly demonstrate that without task-specific supervision, the model gravitates toward uniform attention, thereby confirming the necessity of downstream guidance to extract discriminative peak-related spectral information.

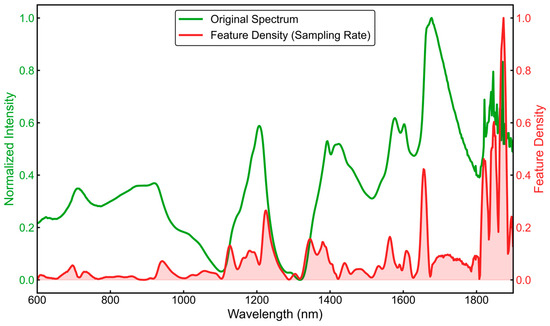

3.6.2. Analysis and Discussion of Spectral Feature Sampling

Although our model adopts a fixed downsampling stride of two, the convolutional layers with ReLU activation still provide an inherent feature selection mechanism. Convolution kernels produce high-magnitude responses that pass through the ReLU layer and are preserved, thereby retaining rich high-frequency details and effectively acting at a high sampling rate. In contrast, weak or negative responses are suppressed or set to zero by the ReLU, which corresponds to a lower sampling rate that filters out redundant information. Thus, the model can dynamically allocate information within the spectral features according to the local characteristics of the input signal.

As shown in Figure 7, we visualized the feature activation intensity of the local extraction branch (convolutional layers) and compared it with the averaged input spectrum. The results indicated that the feature sampling density was strongly correlated with the amplitudes of the spectral peaks. This suggests that the model automatically “focused” on peak-dense regions, thereby achieving an implicit form of adaptive spectral processing.

Figure 7.

Relationship between spectral intensity and the learned feature-sampling density. The original spectrum (green) is shown together with the activation-derived feature density (red), which reflects how frequently local features are preserved after convolution and ReLU. Higher feature density appears around strong absorption peaks, indicating that the model allocates more sampling effort to informative spectral regions during denoising. (Qualitative observation only).

3.7. Comparison Experiments on Downstream Regression Tasks

The experiments outlined in Section 3.6 suggest that BiLSTM-FuseNet reconstructs spectra in a way that focuses on high-level consistency and does not directly promote local peak features, which is consistent with the overall reconstruction of spectra. However, internal behavior does not directly reflect practical utility. To assess whether the denoising performance changes into usable analytical performance, we also performed downstream regression experiments on tablet quality attributes.

Three tablet properties—weight, hardness, and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) content—were predicted using Support Vector Regression (SVR). The inputs included the original noisy spectra, BiLSTM denoised spectra, denoised spectra, and clean reference spectra, and the evaluation metrics were the RMSE, R2, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R).

As shown in Table 9, the tablet weight prediction under mixed noise (σ = 0.25) performed poorly when SVR was trained on the original noisy spectra (R2 = 0.079; R = 0.291). When using the spectra denoised by the BiLSTM baseline, R2 improved to 0.209. BiLSTM-FuseNet further boosted the performance to R2 = 0.218, representing a statistically significant improvement over the noisy baseline (p < 0.01) and provided the closest prediction to the clean–spectra benchmark (R2 = 0.393). These results indicate that denoising effectively restores the spectral characteristics relevant to tablet mass estimation.

Table 9.

Regression Results for Tablet Weight, Hardness, and API under Mixed Noise and Clean Inputs (all metric values shown by mean ± standard deviation).

For the hardness prediction, the original noisy spectra yielded a very weak predictive power (R2 = 0.029). BiLSTM-denoised inputs improved the performance to R2 = 0.135, whereas BiLSTM-FuseNet achieved R2 = 0.119, performing slightly below BiLSTM but still markedly above the noisy baseline (p < 0.05). The clean reference spectra achieved the best performance (R2 = 0.397), suggesting that the hardness is moderately robust to noise but remains sensitive to residual distortions. The gap between denoised and clean performance implies that hardness-related spectral variations likely reside in confined regions, where even subtle errors may be amplified.

Prediction of API content proved to be the most challenging. Using noisy spectra, the SVR exhibited R2 = 0.033 and R = 0.247, indicating almost no predictive utility. The denoising approaches produced small but statistically significant gains (R2 = 0.070 for BiLSTM; R2 = 0.074 for BiLSTM-FuseNet, both p < 0.05). Nonetheless, the performance remained well below that of the clean spectra model (R2 = 0.585). This behavior implies that the estimation of API is sensitive to subtle, fine-grained, spectral features, which are extremely susceptible to interference and difficult to recover without fully restoring peak-related information.

Overall, these results confirm that spectral denoising substantially enhances downstream regression performance, particularly for global quantity indicators, such as tablet weight. Although improvements in hardness and API content are modest, denoised inputs consistently outperform their noisy counterparts, demonstrating the practical transferability and applied value of the proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet in real analytical workflows.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we propose a spectral denoising method based on artificial noise addition and weakly supervised learning which enables high-quality spectral restoration without the need for real labels or clean noise-containing paired data. By simulating different types and intensities of noise pollution, we constructed a unified self-supervised training framework to reconstruct the mapping relations of the original spectral lines from noise-containing spectra, using autoencoder structure learning.

The experimental results indicate that the proposed approach is robust and generalized in the presence of different noise types and SNR levels. In particular, with mixed noise at σ = 0.5 (Input SNR = 0.39), the proposed BiLSTM-FuseNet achieves 88.9% reconstruction error reduction compared to PCA (0.033 vs. 0.299 RMSE) and has a slightly higher value of Pearson correlation than the vanilla BiLSTM baseline (+0.001). Moreover, the coefficient of determination increased from 0.411 to 0.430, reflecting a 4.6% improvement in predictive consistency.

Despite its excellent denoising performance, the proposed method has several limitations. First, BiLSTM-FuseNet relies on the numerical fidelity of the reference spectra; in downstream pill hardness prediction, we observed performance degradation when the “clean” reference still contained weak noise or non-ideal artifacts. This indicates that an excessively faithful reconstruction of suboptimal reference signals may propagate undesirable spectral details to the subsequent models. Second, the model implicitly captures global spectral consistency rather than emphasizing the characteristic peak bands, which limits interpretability and reduces discriminative ability when spectral peaks are subtle or sparsely distributed.

Future studies should explore stronger regularization strategies to alleviate these challenges. Contrastive learning can be incorporated to decouple key structural features from weak background signals, thereby reducing the reliance on ideal labels. Furthermore, hybrid attention or spectral prior-guided mechanisms may help bias the feature extraction towards chemically meaningful bands. Finally, extending this method to cross-instrument adaptation, real production spectra, and larger datasets will further validate its practical value in industrial spectral analytics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and S.-H.K.; methodology, J.X.; software, J.X.; validation, J.X., S.-H.K. and X.C.; formal analysis, J.X., S.-H.K. and X.C.; data curation, J.X. and S.-H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.K. and X.C.; visualization, J.X.; supervision, S.-H.K. and X.C.; project administration, S.-H.K.; funding acquisition, S.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (IITP-2023-RS-2023-00256629) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) and the Information Technology Research Center (ITRC) support program (IITP-2025-RS-2024-00437718) supervised by IITP.

Data Availability Statement

The Pharmaceutical Tablet dataset is available at [34], and the Anhui-NIR-Soil dataset is available at [8], No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- He, C.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, J. Raman optical identification of renal cell carcinoma via machine learning. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 252, 119520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, M.; Fahmideh, S.; Mosaddeghi, M.R. Rapid assessment of soil water repellency indices using Vis–NIR spectroscopy and pedo-transfer functions. Geoderma 2022, 406, 115486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Mircoli, A.; Potena, D.; Diamantini, C.; Duca, D.; Toscano, G. Prediction of pellet quality through machine learning techniques and near-infrared spectroscopy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 147, 106566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.T.; Walsh, K.B. The evolution of chemometrics coupled with near infrared spectroscopy for fruit quality evaluation. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2022, 30, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Nikzad-Langerodi, R. Partial least square regression versus domain invariant partial least square regression with application to near-infrared spectroscopy of fresh fruit. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2020, 111, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Marini, F.; Brouwer, B.; Roger, J.-M.; Biancolillo, A.; Woltering, E.; Hogeveen-van Echtelt, E. Sequential fusion of information from two portable spectrometers for improved prediction of moisture and soluble solids content in pear fruit. Talanta 2021, 223, 121733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Nordon, A.; Roger, J.-M. Improved prediction of tablet properties with near-infrared spectroscopy by a fusion of scatter correction techniques. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 192, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Yan, T.; Xu, G.; Liu, A.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Jin, X. MAE-NIR: A masked autoencoder that enhances near-infrared spectral data to predict soil properties. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Han, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Li, R.; Li, S. Visible and near-infrared spectroscopy with chemometrics are able to predict soil physical and chemical properties. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2749–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Zou, C.; Li, J.; Han, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Fan, Y. Identification of moyamoya disease based on cerebral oxygen saturation signals using machine learning methods. J. Biophotonics 2022, 15, e202100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Q.; Tang, G.; Feng, Q.; Lin, L. The combined optimization of Savitzky–Golay smoothing and multiplicative scatter correction for FT–NIR PLS models. ISRN Spectrosc. 2013, 2013, 642190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechram, S.; Ayu, I.W.; Farni, Y. Pretreatment method standard normal variate (SNV) and baseline shift correction (BSC) on the NIRS-based soil spectrum for rapid prediction of soil nitrogen content. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1290, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Guo, G.; Li, Y.; Via, B.K.; Pei, Z. Spectral pre-processing and multivariate calibration methods for the prediction of wood density in Chinese white poplar by visible and near infrared spectroscopy. Forests 2022, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.K.; Moura-Bueno, J.M.; Ramon, R.; Almeida, T.F.; Naibo, G.; Martins, A.P.; Santos, L.S.; Gianello, C.; Tiecher, T. Combining different pre-processing and multivariate methods for prediction of soil organic matter by near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in Southern Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 29, e00530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, J.-M.; Mallet, A.; Marini, F. Preprocessing NIR spectra for aquaphotomics. Molecules 2022, 27, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Guan, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y. A quality detection method of corn based on spectral technology and deep learning model. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 305, 123472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chu, K.; Smith, Z.J. Hybrid principal component analysis denoising enables rapid, label-free morpho-chemical quantification of individual nanoliposomes. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 14232–14241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Chen, Z.; Luan, X.; Liu, F. Denoising stacked autoencoders–based near-infrared quality monitoring method via robust samples evaluation. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 2693–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyanon, S.; Deepaisarn, S.; Chokphantavee, S.; Prathipasen, P.; Laitrakun, S.; Opaprakasit, P.; Viriyavit, W.; Jaikaew, N.; Jindakaew, J.; Rakpongsiri, P.; et al. Denoising Raman Spectra Using Autoencoder for Improved Analysis of Contamination in HDD. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113661–113676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Yuan, L.; Shi, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. Using one-class autoencoder for adulteration detection of milk powder by infrared spectrum. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrito, T.; Zouaoui, A.; Chanussot, J.; Mairal, J. A Trainable Spectral–Spatial Sparse Coding Model for Hyperspectral Image Restoration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 5430–5442. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, H.; Yu, J.; Luo, J.; Paliwal, J.; Sun, D.-W. Terahertz spectra reconstructed using convolutional denoising autoencoder for identification of rice grains infested with Sitophilus oryzae at different growth stages. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 311, 124015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liang, W.; Jia, J. Structural Vibration Signal Denoising Using Stacking Ensemble of Hybrid CNN-RNN. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y. Dual residual attention network for image denoising. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 149, 110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Yan, C.; Fu, Y. Hybrid spectral denoising transformer with guided attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 13065–13075. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Sahana, B.C. A deep-learning-based auto encoder–decoder model for denoising electrocardiogram signals. IETE J. Res. 2025, 71, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ke, C.; Li, K. Hybrid Spatial–Spectral Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Denoising. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Mangalam, K.; Huang, P.-Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Xie, C.; Yuille, A.; Feichtenhofer, C. Diffusion models as masked autoencoders. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 16284–16294. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.; Ma, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Guo, X.; Chen, S. Towards Visual Interaction: Hand Segmentation by Combining 3D Graph Deep Learning and Laser Point Cloud for Intelligent Rehabilitation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Meng, Z.; Zheng, G.; Yang, L.; Guo, X.; Tan, L.; Jiang, Y. Human–computer interactive rehabilitation: A 3D graph deep learning method for non-contact gesture recognition in post-epidemic and aging societies. Measurement 2025, 257, 118794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ng, M.K.; Michalski, J.; Peyré, G.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.; Wei, L. A Self-Supervised Deep Denoiser for Hyperspectral and Multispectral Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Luo, Z. Multivariety and multimanufacturer drug identification based on near-infrared spectroscopy and recurrent neural network. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 2022, 15, 2250022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenvector Research. NIR Spectra of Pharmaceutical Tablets from “Shootout”. Available online: https://eigenvector.com/resources/data-sets/nir-spectra-of-pharmaceutical-tablets-from-shootout/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Sim, J.; Dixit, Y.; McGoverin, C.; Martens, J.; Du Plessis, M.; Manley, M. Support Vector Regression for Prediction of Stable Isotopes and Trace Elements Using Hyperspectral Imaging on Coffee for Origin Verification. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.