Abstract

Weak-signal fluorescence channels (e.g., 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)) often fail to provide reliable structural details due to low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and insufficient high-frequency information, limiting the ability of single-channel super-resolution methods to restore edge continuity and texture. This study proposes a multi-channel guided super-resolution method based on SwinIR, utilizing the high-SNR fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) channel as a structural reference. Dual-channel adaptation is implemented at the model input layer, enabling the window attention mechanism to fuse cross-channel correlation information and enhance the structural recovery capability of weak-signal channels. To address the loss of high-frequency information in weak-signal imaging, we introduce a frequency-domain consistency loss: this mechanism constrains spectral consistency between the predicted and true images in the Fourier domain, improving the clarity of fine-structure reconstruction. Experimental results on the DAPI channel demonstrate significant improvements: PSNR increases from 27.05 dB to 44.98 dB, and SSIM rises from 0.763 to 0.960. Visual analysis indicates that this method restores more continuous nuclear edges and weak textural details while suppressing background noise; frequency-domain results reduce the minimum resolvable feature size from approximately 1.5 μm to 0.8 μm. In summary, multi-channel structural information provides an effective and physically interpretable deep learning approach for super-resolution reconstruction of weak-signal fluorescence images.

1. Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy is widely used in life science and medical research to observe subcellular details such as the cell nucleus, organelles, and membrane structures [1,2]. Different fluorescent dyes (such as 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)) can provide multi-channel images in the same field of view, allowing researchers to acquire information from different structures simultaneously. However, due to differences in the optical properties, excitation wavelengths, and detection sensitivities of the dyes, multi-channel images often exhibit significant inconsistencies in signal-to-noise ratio, brightness, and resolution, posing challenges to subsequent visualization and quantitative analysis [3].

Among these channels, the blue-excited DAPI channel is typically limited by physical constraints such as weak short-wavelength penetration, high background noise, and insufficient high-frequency detail, resulting in blurred structures, lost texture, and discontinuous edges [4,5]. In contrast, the green channel obtained with dyes such as FITC usually exhibits a higher signal-to-noise ratio and clearer structural boundaries [6]. This significant cross-channel quality difference not only affects the accuracy of identifying weak signal structures (such as cell nuclei) but also weakens the overall interpretability and stability of multi-channel micrographs.

While structured illumination microscopy (SIM) can improve nominal resolution through frequency mixing [7], its imaging quality remains susceptible to fringe drift, insufficient excitation energy, and weak signal noise amplification, resulting in inconsistent structural representations across different channels [8]. Deep learning super-resolution methods offer effective tools for improving the quality of microscopic images, but traditional single-channel models often struggle to recover high-frequency information that is absent or extremely weak in the original signal due to a lack of reliable structural priors in weak signal channels [9,10,11].

Specifically, when faced with the inherently low signal-to-noise ratio and strong shot noise interference of the DAPI channel, existing single-channel super-resolution networks often fall into the predicament of solving an ill-conditioned inverse problem: the model struggles to accurately locate real biological structures against a complex noisy background, thus easily generating two typical defects. On the one hand, the model may mistakenly identify random noise in the background as high-frequency features, thereby ‘constructing’ non-existent false textures or ringing artifacts in the image; on the other hand, in order to suppress strong noise interference, the model tends to over-smooth the image, causing the removal of crucial chromatin heterogeneity details inside the cell nucleus. This dilemma between ‘artifact generation’ and ‘detail loss’ makes the reconstruction results relying solely on single-modal information often lack biological fidelity and fail to meet the needs of high-precision quantitative analysis. Therefore, a reconstruction method specifically designed to enhance weak signal fluorescence channels and effectively fuse complementary structural information from multiple channels is still lacking [12].

In recent years, transformer-based image restoration and super-resolution have achieved substantial progress by leveraging long-range dependency modeling and hierarchical attention mechanisms, improving the recovery of fine structures beyond conventional CNN-based approaches. Representative works such as SwinIR introduced window-based self-attention into image restoration and demonstrated strong performance across classical SR and related restoration tasks [13], while subsequent variants (e.g., Swin2SR) further improved training stability and restoration quality under compressed or degraded inputs [14]. Beyond low-level vision, transformer attentions and cross-layer interaction designs have also been widely adopted in other domains such as remote sensing scene understanding (e.g., FCIHMRT), indicating that attention-based feature interaction is a general mechanism for enhancing structure-aware representation learning across tasks [15]. In parallel, blind/real-world SR has been actively investigated to handle unknown degradations, where Real-ESRGAN provides a practical pipeline for general image restoration under complex real degradations [16]. More recently, advanced transformer restorers with hybrid attention designs have shown further improvements in quantitative performance and visual fidelity in super-resolution and broader restoration settings [17]. Despite these advances, most existing methods still predominantly operate in a single-modality/single-channel manner, which limits robustness when the target channel is dominated by weak signals and noise. This motivates exploring cross-channel structural redundancy as an explicit prior, especially in multi-channel fluorescence microscopy, where auxiliary channels often contain clearer boundaries and more reliable morphology.

To address the aforementioned issues, this study proposes a physically aware multi-channel SwinIR super-resolution reconstruction framework. Unlike traditional single-channel models that rely solely on the information inherent in the weak signal, we utilize the high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) FITC channel as a strong structural reference, transforming the reconstruction task of the DAPI channel into an inverse problem under physical constraints. In terms of model architecture, we design an “Early Fusion” strategy combined with a window attention mechanism. By directly concatenating dual-channel tensors at the network input layer, the model can fully leverage cross-channel spatial correlation, overcoming the information bottleneck of weak signals from the initial stage of feature extraction, thereby significantly improving the reconstruction capability of subtle high-frequency details.

Furthermore, to explicitly address the high-frequency information loss caused by the denoising process, we introduce a hybrid optimization objective that includes frequency-domain consistency loss. This physically aware constraint forces the network to align with the real image not only in terms of spatial pixels but also in terms of spectral distribution, effectively restoring sharp edges and subtle textures within cell nuclei that are typically suppressed by pixel-level loss functions. Experimental results demonstrate that this method achieves substantial breakthroughs in both quantitative metrics and visual quality: it significantly improves the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) of the DAPI channel to 44.98 dB and reduces its minimum resolvable structure size from 1.5 μm to 0.8 μm. This result strongly demonstrates the effectiveness of using multi-channel structural redundancy to compensate for the physical limitations of short-wavelength imaging and showcases the enormous potential of this method in the field of weak-signal fluorescence image enhancement.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a cross-modality guided super-resolution framework for weak-signal fluorescence imaging, in which a high-SNR auxiliary channel provides a structural prior to improve the reconstruction of the target weak-signal channel.

- (2)

- We adapt SwinIR to a dual-channel early-fusion input setting and analyze the role of window-based attention in enabling cross-channel feature interaction for structure-aware restoration.

- (3)

- We design a hybrid objective by combining pixel-, structure-, and frequency-domain consistency constraints, and validate the proposed method against bicubic interpolation, Real-ESRGAN, and single-channel SwinIR using both quantitative metrics and ROI-based qualitative comparisons.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Formulation: Physics-Guided Image Restoration

In wide-field fluorescence or structured illumination microscopy (SIM), the imaging quality of weak signal channels (such as DAPI-labeled cell nuclei) is often limited by the photon budget and the system’s transfer function. We model the observed low-quality DAPI images as a result of potential high-resolution real signals undergoing physical degradation. This degradation process can be expressed as follows:

Here, k denotes the Point Spread Function (PSF) of the optical system, represents the convolution operation, is the downsampling operator (which simulates limited optical resolution or digital sampling), and n follows a Poisson–Gaussian distribution. It represents the mixed superposition of photon shot noise and readout noise [18].

Due to the short wavelength and limited excitation intensity of DAPI channels, the interference of the noise term n often leads to the inverse problem solving (i.e., recovery from to ) to become seriously ill-posed. Deep learning methods have been shown to have significant advantages in solving such inverse problems [11]. However, the traditional single-channel super-resolution method attempts to learn this mapping directly, but under very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, the loss of information in a single modality very easily leads to texture smoothing or artifact generation [19].

To mitigate this pathology, this study introduces a high signal-to-noise ratio green fluorescence channel (FITC) as the reference image . Although and label different biological structures (cell membrane vs. nucleus), both are imaged through the same optical system and share similar PSF characteristics k and spatial topological constraints [20]. Therefore, we transform the reconstruction task into a problem of maximizing the conditional probability:

In Equation (2), denotes the weak-signal target-channel input to be enhanced (i.e., the low-resolution DAPI image), and denotes the high-SNR reference-channel input acquired from the same field of view (i.e., the low-resolution FITC image). represents the predicted high-resolution reconstruction of the target channel (i.e., the network output super-resolved DAPI image). denotes the proposed multi-channel mapping function that takes as input and outputs the reconstructed target-channel image, while denotes the set of learnable parameters of the deep neural network. The term gives a maximum a posteriori (MAP) formulation, where denotes all possible candidate high-resolution solutions for the target channel, and denotes the conditional probability distribution parameterized by given the target-channel observation and the reference-channel guidance. Note that is an operator; it returns the candidate that maximizes the conditional probability. This formulation indicates that the network leverages the structural information provided by to constrain the solution space, thereby suppressing background noise while improving the recovery of high-frequency details in the weak-signal target channel.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Imaging and 16-Bit High Dynamic Range Processing

The experimental data were acquired using a structured illumination microscope (SIM) system, which can break the diffraction limit and provide higher resolution than conventional wide-field microscopes [7]. The raw data consisted of multiple time-lapse and depth (Z-stack) scan images. To preserve the subtle grayscale changes in weak signal regions and prevent overexposure of bright nucleolar regions, all raw czi format data were separated into independent DAPI (blue) and FITC (green) channels using the Bio-Formats plugin [21] and exported as 16-bit lossless TIFF format. Compared to conventional 8-bit images, 16-bit depth can provide a grayscale range of 0–65,535, which is crucial for capturing the large dynamic range of DAPI channels from extremely dark backgrounds to bright chromatin.

2.2.2. Cross-Modality Alignment and Dataset Construction

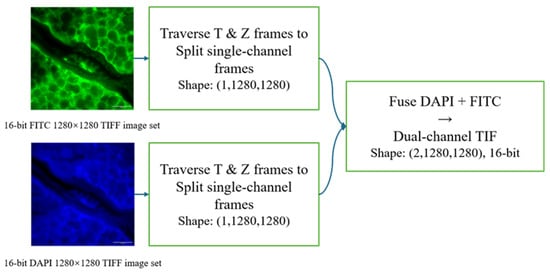

In the preprocessing pipeline (Figure 1), the DAPI and FITC channels were acquired almost synchronously within the same field of view, and thus were treated as naturally aligned at the pixel level. Each SIM-reconstructed sequence was first decomposed into single-channel frames by traversing the time axis (T) and focal depth (Z-stack), yielding paired DAPI and FITC frames with the same (FOV, t, z) index. To preserve dynamic range while ensuring numerical stability, we performed intensity normalization on the original 16-bit images at the 16-bit level before forming training pairs. For each paired sample, the high-resolution ground truth (GT) was the original SIM output of size 1280 × 1280, and the corresponding low-resolution input (LR) was generated by 4 × bicubic downsampling of GT to 320 × 320. The two LR frames were then concatenated along the channel dimension to form a dual-channel input tensor (channel order: [DAPI, FITC]), while the supervision target was the DAPI GT frame. During training, we randomly cropped aligned patches of size 64 × 64 from the LR tensors (and the corresponding GT regions) to construct mini-batches.

Figure 1.

Data preprocessing pipeline demonstrating channel separation, high dynamic range retention, and dual-channel tensor construction.

In this study, ground truth (GT) is defined as the high-resolution image directly derived from the SIM reconstruction result, i.e., the original output version without any downsampling processing. The corresponding low-resolution input (LR) is generated by downsampling the GT using 4× bicubic interpolation, and is used to construct paired training data under a controlled degradation model [14]. Bicubic downsampling was chosen instead of more complex or stochastic degradation models because it is a widely adopted and highly reproducible protocol in super-resolution benchmarks. This deterministic setting provides a controlled LR generation rule, enabling fair comparisons across methods and clearer attribution of performance gains. Based on the above pairing and construction process, we finally obtained 741 pairs of dual-channel sample pairs (each pair contains corresponding DAPI and FITC images). At the sample level, we randomly divided them into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio, with 518 pairs in the training set, 149 pairs in the validation set, and 74 pairs in the test set. In addition, necessary manual quality control was performed before constructing the training samples, including manual cropping of the main region of the cell nucleus to reduce the interference of large areas of black background without information on the training, and manual removal of out-of-focus or obviously blurred frames to improve the clarity of the sample structure boundaries and the stability of the signal-to-noise ratio, thereby ensuring that the data used for modeling has good structural integrity and representativeness.

2.3. Network Architecture: Multi-Channel Guided SwinIR

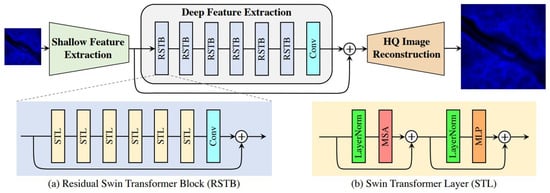

To effectively integrate cross-channel information and model long-range dependencies, we adopted SwinIR [13], a Swin Transformer-based image restoration backbone, as the core architecture of our framework. SwinIR combines convolutional inductive priors for local feature extraction with hierarchical window-based self-attention for non-local feature interaction, and has demonstrated strong performance on super-resolution and general image restoration tasks [22]. As illustrated in Figure 2, the backbone consists of three main modules: (i) shallow feature extraction, (ii) deep feature extraction using stacked Residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTB), and (iii) high-quality image reconstruction. In our multi-channel setting, the cross-modality guidance was introduced at the network input via the early-fusion strategy (Section 2.3.1), where the LR DAPI and LR FITC images were concatenated channel-wise before being fed into the same SwinIR backbone.

Figure 2.

Simplified schematic of the SwinIR model architecture.

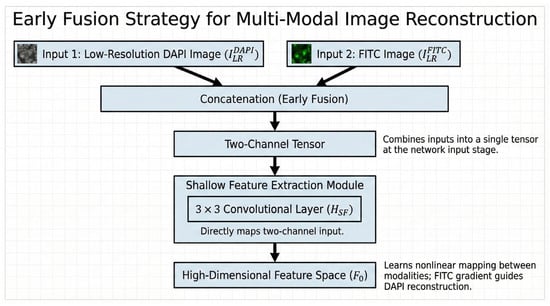

2.3.1. Early Fusion Strategy

Unlike traditional single-channel input, we designed an “Early Fusion” strategy. At the network input, we concatenated the low-resolution DAPI image and the FITC image into a two-channel tensor. The shallow feature extraction module contains a convolutional layer , which directly maps this two-channel input to the high-dimensional feature space :

By fusing the first layer of convolution, the network can learn the nonlinear mapping relationship between the two modalities from the bottom pixel space [23] and transform the high signal-to-noise ratio gradient information of the FITC channel into a feature map that guides the reconstruction of the DAPI channel. The flowchart of the early fusion strategy is shown in Figure 3. The overall procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Overall training and inference pipeline. |

| Input: Paired HR images (); scale factor s = 4; loss weights , ; Adam (, ); total iterations T. Output: Trained parameters ; predicted SR image . Dataset preparation For each paired HR sample (): ← BicubicDownsample (, s) ← BicubicDownsample (, s) Randomly split samples into training/validation/test sets with a ratio of 7:2:1 (test set: 74 pairs). Training Initialize model parameters θ. For t = 1 to T do: Sample a mini-batch of paired patches {(, , )} from the training set. Early fusion: ← [, ] (channel-wise concatenation). Forward: ← . Joint loss: Update: ← AdamUpdate(, ). Validation (periodically): evaluate PSNR/SSIM on the validation set and save the best checkpoint. End for Inference/Testing Load the best checkpoint . For each test sample (, ): ← [, ] ← . Report average PSNR/SSIM on the test set (74 pairs). |

Figure 3.

The block diagram of the early fusion strategy.

2.3.2. Deep Feature Extraction with RSTB

The deep feature extraction module consists of K residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTB). Each RSTB contains multiple Swin Transformer Layers (STLs). The core of STL is the window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA) mechanism [10], and its calculation process is as follows:

In the context of multi-channel input, the Query () vector in the fused features is mainly driven by the DAPI signal to be recovered, looking for structural edges, while the Key () and Value () vectors obtain references from high-resolution FITC features, providing strong prior information about “where the edges should be”.

2.3.3. Image Reconstruction

After deep feature extraction, the feature maps are processed through convolutional layers and a Pixel Shuffle upsampling module, which increases the spatial resolution by a factor of 4. This ultimately generates a high-resolution DAPI reconstructed image .

2.4. Loss Function Formulation

To comprehensively address the characteristics of fluorescence microscopy images—extremely dark backgrounds, bright foregrounds, and blurred edges—we designed a hybrid loss function to guide network optimization. Unlike traditional methods that rely solely on spatial domain constraints, we incorporated pixel, structural, and frequency consistency terms:

where and are hyperparameters balancing the contribution of different loss components. In our implementation, we set for the SSIM term and for the frequency-domain consistency term. These values were selected to achieve a stable trade-off between pixel fidelity, structural preservation, and high-frequency detail recovery and were further verified by a small-scale sweep on the validation set.

2.4.1. Charbonnier Loss

To improve the model’s robustness to outliers and handle non-Gaussian noise, we used Charbonnier Loss (a smooth L1 loss) as the main pixel-level constraint [24]:

where and represent the reconstructed image and the true high-resolution image, respectively, and is set to .

2.4.2. SSIM Loss

To enhance the recovery of cell nucleus morphology and internal texture, we introduced structural similarity (SSIM) loss [25]. SSIM can effectively constrain the topological integrity of the cell nucleus edge:

2.4.3. Frequency-Domain Consistency Loss

In weak signal imaging, spatial domain-based loss functions (such as and ) often fail to adequately recover high-frequency details obscured by noise, easily leading to over-smoothed reconstruction results. To overcome this physical limitation, we introduced a frequency-domain consistency loss to explicitly supervise spectral consistency. Specifically, leveraging the property that high-frequency components in the Fourier domain correspond to image edges and subtle textures, we used Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to map the reconstructed image and the true high-resolution image to the frequency domain, and constrain the difference between their amplitude spectra:

where represents the Fast Fourier Transform operation, and represents the norm. This loss term forces the network to approximate the true value not only in spatial location but also in frequency distribution, thereby effectively sharpening edges and restoring key details of chromatin heterogeneity.

In practice, the proposed frequency-domain consistency term is optimized jointly with the spatial-domain losses. For each training iteration, we compute the pixel-wise Charbonnier loss , the structural loss , and the frequency loss between the reconstructed DAPI image and the corresponding ground truth , and combine them as a weighted sum . The FFT operation is differentiable; thus, the gradients from can be backpropagated to update the network parameters, together with the gradients from and . This joint optimization encourages both spatial fidelity/structure preservation and spectral (high-frequency) alignment, reducing over-smoothing while avoiding noise-induced artifacts.

2.5. Implementation Details and Evaluation Metrics

2.5.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were implemented using the PyTorch 1.10 framework and equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Input images were randomly cropped to 64 × 64 patches. The model was trained for 500,000 iterations using the Adam optimizer (9, ) with an initial learning rate of .

2.5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance in weak signal reconstruction tasks, this study uses two metrics, peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), to measure the pixel accuracy and structural consistency of the reconstructed image, respectively.

PSNR measures the difference between the reconstructed image and the real image based on pixel error, and is defined as follows:

Here, represents the maximum value of the image pixel; and are the i-th pixel values of the real image and the model-reconstructed image, respectively; and n is the total number of pixels in the image. The higher the PSNR, the better the reconstruction accuracy.

Here, x and y represent the reference image and the reconstructed image, respectively; and represent the mean of the image; and represent the variance of the image; is the covariance; and are stability constants used to avoid a zero denominator. The closer SSIM is to 1, the better the reconstruction maintains structural consistency.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Evaluation

To evaluate the reconstruction quality, we performed a quantitative comparison against standard Bicubic interpolation and state-of-the-art single-channel super-resolution methods, including the GAN-based Real-ESRGAN and the baseline single-channel SwinIR. Table 1 presents the average peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity (SSIM) on the test set.

Table 1.

Comparison of single-channel and multi-channel SwinIR performance on the DAPI channel (mean on the 74-pair test set).

As shown in Table 1, the single-channel deep learning methods face significant challenges under weak-signal conditions. Real-ESRGAN yields the lowest structural consistency with an SSIM of 0.742, and the single-channel SwinIR achieves only 27.05 dB in PSNR. While bicubic interpolation shows a relatively higher PSNR (30.79 dB) due to background smoothing, its structural fidelity remains limited (SSIM 0.799).

In contrast, the proposed multi-channel SwinIR, by introducing the FITC channel as a reference, achieves substantial improvements across all metrics. Specifically, it increases the PSNR to 44.98 dB and the SSIM to 0.960, significantly outperforming both the interpolation-based and single-channel learning-based methods. This result quantitatively confirms that fusing cross-modal information effectively restores high-fidelity structural details that are unrecoverable by single-channel approaches.

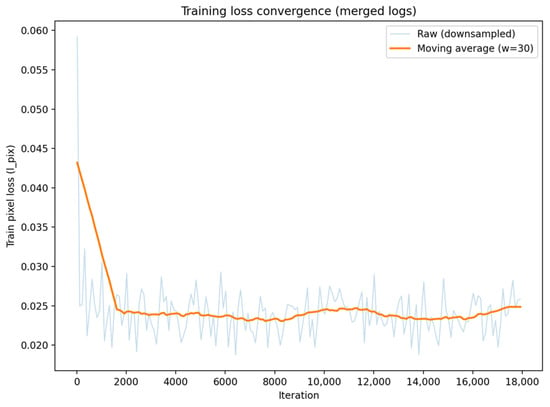

Figure 4 shows the convergence of the training loss (pixel-wise loss ) of the proposed dual-channel SwinIR throughout the entire training process. The light-colored curves represent the original mini-batch loss (downsampled for visualization purposes), while the solid curves denote the moving average trend (with a window size ). The loss decreases rapidly in the early stage and then stabilizes in a steady plateau, which indicates that the model converges reliably without divergence.

Figure 4.

Training loss convergence of the proposed multi-channel SwinIR (merged logs).

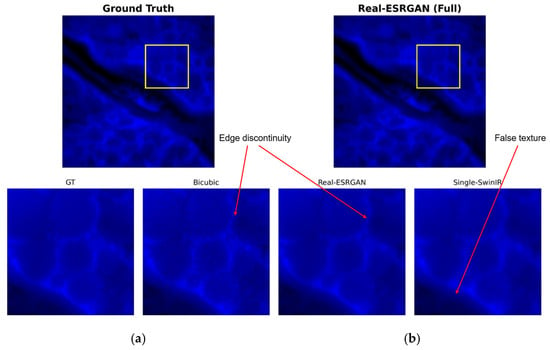

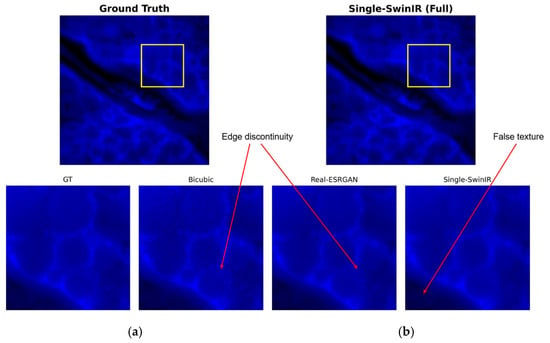

3.2. Analysis of Single-Channel Reconstruction Defects

To comprehensively evaluate the limitations of super-resolution reconstruction relying solely on single-modality DAPI input, this study compared two representative deep learning methods: the generative adversarial network-based Real-ESRGAN model and the SwinIR model using only single-channel input. While deep learning models show potential in overall image enhancement, experimental results indicate that single-channel methods exhibit significant structural deficiencies in weak signal and dense cell imaging scenarios. To visually illustrate these problems, we conducted detailed visual and quantitative analyses of typical failure regions in the test set.

Figure 5 shows the reconstruction results of the Real-ESRGAN model across the entire field of view and a magnified view of the region of interest (ROI), indicated by the yellow square. Although this method demonstrates a certain ability to improve image contrast and sharpness, the generated results are accompanied by severe visual artifacts. Observation of the reconstructed image reveals that Real-ESRGAN tends to over-amplify high-frequency noise in the background, resulting in a large number of messy granular noises and unnatural color patches in areas that should be pure black. This over-amplification of noise reduces the signal-to-noise ratio, indicating that without additional structural information guidance, the single-channel method based on GANs struggles to accurately distinguish weak fluorescence signals from background noise, thus generating pathologically unnatural textures.

Figure 5.

Visual assessment of Real-ESRGAN reconstruction: (a) ground truth (GT); (b) single-channel Real-ESRGAN reconstruction result. The yellow square indicates the region of interest (ROI) for the zoom-in comparison.

Figure 6 shows the reconstruction performance of the single-channel SwinIR model. While this model is superior to Real-ESRGAN in suppressing high-frequency noise, it comes at the cost of sacrificing high-frequency image details, resulting in significant over-smoothing. Specifically, in low-signal background regions, the single-channel SwinIR produces non-physical, filamentous, or mesh-like false texture structures that are not present in the ground truth (GT) image. This also causes the cell nuclei to appear as uniform blocks, losing internal texture information crucial for biological analysis.

Figure 6.

Visual assessment of single-channel SwinIR reconstruction: (a) ground truth (GT); (b) single-channel SwinIR reconstruction result. The yellow square indicates the region of interest (ROI) for the zoom-in comparison.

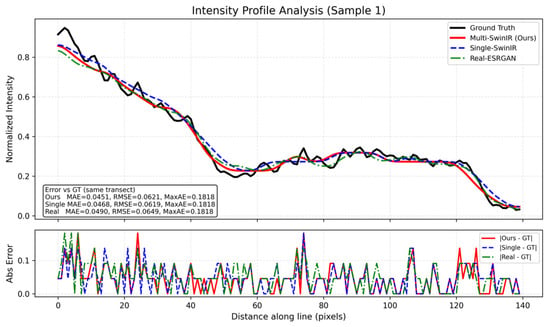

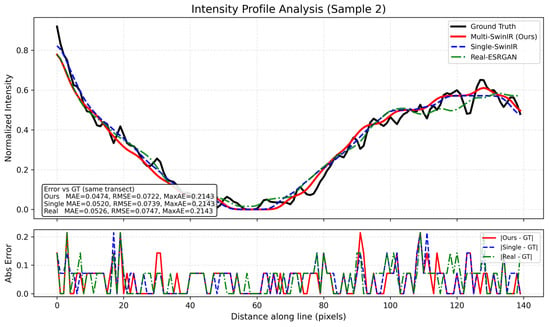

To further quantify the behavior of different methods in a dense nucleus region, we performed an intensity profile analysis along a fixed transect across two adjacent cell nuclei, as shown in Figure 7. In the ground truth profile, a pronounced “U”-shaped trough is observed between two higher-intensity regions, where the normalized intensity drops to a low level (below approximately 0.2), reflecting a clear separation along the sampled line. The top panel overlays the normalized intensity profiles of all methods along the same transect. In addition, Figure 7 reports error measures around the plot: the inset box summarizes MAE/RMSE/MaxAE computed with respect to the ground truth along this transect, and the bottom panel visualizes the absolute error profiles over the same pixel distance. Here, MAE denotes the mean absolute error, RMSE denotes the root mean squared error, and MaxAE denotes the maximum absolute error along the transect. For a profile of length , , , and , where and are the normalized intensities of the method output and the Ground Truth at position , respectively. For this transect, Multi-SwinIR (ours) achieves MAE = 0.0451 and RMSE = 0.0621 (MaxAE = 0.1818), compared with Single-SwinIR (MAE = 0.0468, RMSE = 0.0619, MaxAE = 0.1818) and Real-ESRGAN (MAE = 0.0490, RMSE = 0.0649, MaxAE = 0.1818).

Figure 7.

Intensity profile analysis of dense nuclei separation.

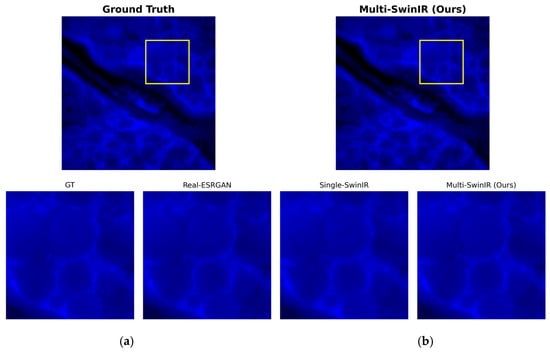

3.3. Dual-Channel Reconstruction Performance in Challenging Scenarios

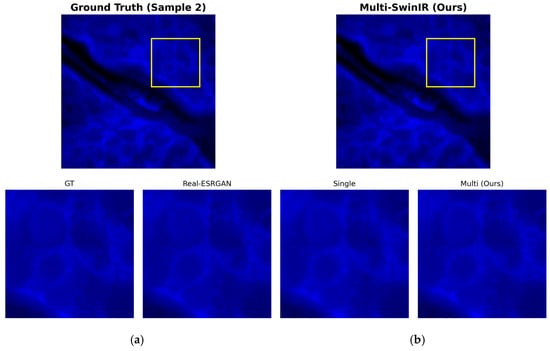

To verify the ability of multi-channel SwinIR to repair single-channel defects, we evaluated the reconstruction performance of the method on the same test samples, focusing on the fidelity of the overall structure and the detail restoration effect in specific challenging scenarios (such as weak backgrounds and dense regions). Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 cover the complete evaluation process, from full-field visual comparison to pixel-level quantitative analysis.

Figure 8.

Overall visual assessment of multi-channel reconstruction: (a) ground truth (GT); (b) multi-channel SwinIR reconstruction result. The yellow square indicates the region of interest (ROI) for the zoom-in comparison.

Figure 9.

Detailed restoration comparison in the background region (Sample 2). (a) ground truth (GT); (b) multi-channel SwinIR reconstruction result. The yellow square indicates the region of interest (ROI) for the zoom-in comparison.

Figure 10.

Generalization analysis of structural recovery on Sample 2.

Figure 8 shows a full-field visual comparison between the multi-channel SwinIR model and the high-resolution reference image (ground truth, GT). From an overall perspective, the introduction of the FITC channel as a structural guide significantly improved the image reconstruction quality. The dual-channel reconstruction results maintained a high degree of consistency with the GT in terms of brightness distribution, dynamic range, image contrast, and cell nucleus morphology. Compared with the single-channel results described earlier, the image on the right side of Figure 7 is overall clear and sharp, and the edge blurring and structural distortion observed in the single-channel reconstruction were completely corrected, demonstrating the advantages of the multimodal fusion strategy in maintaining overall structural consistency.

For background noise suppression and detail restoration in weak signal regions, Figure 9 shows a magnified local comparison of test sample 2 in a low-signal background region. Unlike the single-channel model, which easily generates false filamentous textures in blank areas, the dual-channel reconstruction result on the right side of Figure 8 shows a uniform and pure black background. The experimental results show that the random noise and artifacts that easily appear under weak signal conditions are effectively suppressed here, and the background purity is completely consistent with the GT image on the left. At the same time, the cell edges maintain sharp transitions without excessive smoothing.

To evaluate the profile behavior on a different dense region, we applied the same line-based intensity profile analysis to Sample 2, as presented in Figure 10. This transect includes a deep valley segment in the ground truth profile, where the normalized intensity approaches the minimum level, followed by a clear rising trend along the sampled distance. The top panel shows the normalized intensity profiles of all methods along the same transect for direct comparison of these variations. Similar to Figure 7, Figure 10 also includes quantitative error measures: the inset box reports MAE/RMSE/MaxAE values computed along the plotted transect, and the bottom panel shows the absolute error profiles along the same line. On this transect, Multi-SwinIR (ours) reports MAE = 0.0474 and RMSE = 0.0722 (MaxAE = 0.2143), while Single-SwinIR yields MAE = 0.0520 and RMSE = 0.0739 (MaxAE = 0.2143), and Real-ESRGAN yields MAE = 0.0526 and RMSE = 0.0747 (MaxAE = 0.2143).

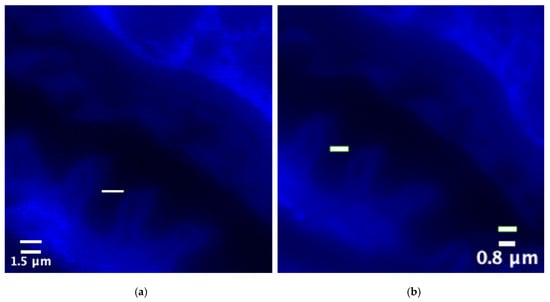

3.4. Improvement in Minimum Resolvable Structure Size

To visually quantify the improvement in spatial resolution, we selected minute structural features in the image for physical size measurement. As shown in Figure 9, we marked the smallest identifiable structural width within the corresponding region of interest (ROI).

In the original low-resolution input image (Figure 11, left), due to optical blurring and pixel undersampling, adjacent structures are clustered together, and their smallest resolvable feature size is approximately 1.5 μm. However, in the image processed by Multi-channel SwinIR (Figure 11, right), these blurred structures are clearly separated, and their smallest resolvable size is reduced to approximately 0.8 μm. This indicates that the reconstructed image has higher resolution in terms of spatial geometric details.

Figure 11.

Spatial resolution scale comparison of blue fluorescence channel images (unit: μm): (a) ground truth (GT) size; (b) multi-channel SwinIR reconstruction size.

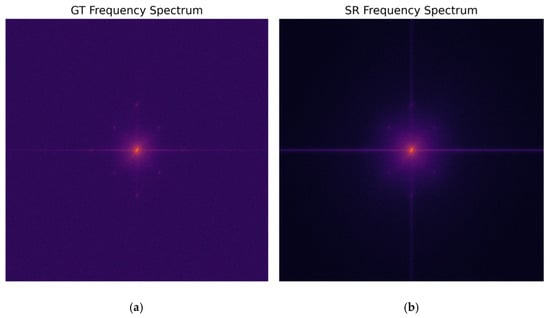

3.5. Validation of Frequency-Domain Consistency

To further enhance the performance of multi-channel methods in the frequency domain, this study performed a Fourier Transform on the multi-channel super-resolution results of the blue fluorescence channel and the corresponding high-resolution original image. The spectrogram visually displays the energy distribution in the low- and high-frequency regions of the image, allowing for observation of the performance of multi-channel reconstruction in recovering high-frequency details. Figure 12 shows a frequency-domain comparison of the super-resolution result and the high-resolution reference image.

Figure 12.

Spectral comparison of the multi-channel blue fluorescence channel super-resolution result and the high-resolution original image: (a) ground truth (GT); (b) multi-channel SwinIR reconstruction.

Observing the spectrogram, the spectral energy of the true HR value naturally extends from the central low frequency to the surrounding high-frequency region. The reconstructed spectrum of the multi-channel SwinIR is highly similar in shape to the true HR value, especially in the high frequency region along the diagonal direction, where the energy distribution shows a significant extension without an obvious cutoff. This indicates that the reconstructed image not only restores the structure in the spatial domain but also effectively fills in the missing high-frequency components in the frequency domain. This high degree of fit in the frequency domain corresponds to the frequency-domain loss term () we introduced in our methodology, indicating that the reconstructed image performs well in preserving high-frequency details and effectively avoids the common problem of oversmoothing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism: Cross-Channel Information Compensation via Structural Priors

The core finding of this study is that introducing a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) FITC channel as a structural reference can fundamentally solve the “structure loss” problem in DAPI channel reconstruction. As shown in Results 3.1, the reconstruction performance of single-channel SwinIR (27.05 dB) is limited by the sparse feature distribution and severe background noise of the DAPI image, leading to network convergence difficulties and blurred edges.

In contrast, the success of the multi-channel strategy (PSNR improved to 44.98 dB) is attributed to an explicit structural supervision mechanism. Although FITC (cell membrane) and DAPI (nucleus) label different biological structures, they have strict topological correlation in space; that is, the nucleus must be located within the region defined by the cell membrane. In the attention computation of dual-channel SwinIR, the clear FITC texture acts as a high-confidence “guide map,” helping the network to locate the correct edge positions in noisy DAPI signals. This mechanism effectively “migrates” the rich high-frequency information in the FITC channel to the DAPI channel, filling the information gaps in the weak signal area, thereby achieving visual edge sharpening and texture restoration.

4.2. Physics: Overcoming the Ill-Posed Nature of Short-Wavelength Imaging

From a physical imaging perspective, DAPI channel reconstruction is essentially an ill-posed inverse problem. Due to the short wavelength, weak penetrating power, and severe scattering of blue light, coupled with the limitation of excitation intensity to protect the sample, DAPI images often exhibit extremely high dynamic range and extremely low signal-to-noise ratio. Under these conditions, single-channel networks cannot distinguish between genuine, weak biological signals and random photon noise, tending to output a smoothed average value to minimize loss, leading to the permanent loss of high-frequency details.

Our multi-channel method introduces a strong physical constraint. Since the blue and green channels are imaged through the same optical system, they share similar point spread function (PSF) and aberration characteristics. Introducing the FITC channel effectively reduces the solution space of the inverse problem, forcing the network-generated solution to conform to the geometric rules of biological structures. Furthermore, the results of frequency-domain analysis (Figure 12) further reveal the physical mechanism of the hybrid loss function. In traditional pixel-distance-based optimization (such as L1/L2), the network tends to output the average of all possible solutions to minimize the error, which manifests as the loss of high-frequency components (low-pass filtering effect) in the frequency domain. However, the explicit frequency-domain constraint we introduce () changes the shape of the optimization surface, giving equal or even greater attention to the error of high-frequency coefficients as to low-frequency coefficients. This mechanism forces the network to seek solutions that not only coincide spatially but are also complete in frequency components, thus mathematically breaking the smoothing tendency caused by noise. This is the fundamental reason why our method can advance the resolvable structure size to 0.8 μm without introducing artifacts.

4.3. Improving Effective Resolution Under Low-SNR Conditions

Another significant contribution of this study is overcoming the resolution limitations under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. In Section 3.4, we observed that the minimum resolvable size was reduced from 1.5 μm in the original image to 0.8 μm. This result demonstrates that, through cross-modal learning, the algorithm effectively mitigates the partial volume effect caused by optical diffraction and undersampling. For weak signal channels like DAPI, traditional methods typically require increasing exposure time or excitation power to achieve sufficient SNR to resolve fine structures, but this introduces risks of photobleaching and phototoxicity. Our method demonstrates that by utilizing the structural redundancy of long-wavelength (green light) channels, sub-micron-level structural details can be “recovered” computationally without altering physical imaging conditions (such as maintaining low-dose excitation). This provides a highly promising engineering solution for high-throughput, low-phototoxicity live-cell microscopy.

4.4. Limitations and Future Scope

Despite the significant improvements achieved by the multi-channel SwinIR over various metrics, this study still has certain limitations. First, the current training data are based on simulated degradation images generated by digital downsampling (bicubic interpolation). While this method is widely used in super-resolution research, it fails to fully reproduce the complex physical degradation mechanisms in real microscopic imaging. Specifically, real low-resolution images are constrained by the diffraction limit and system transfer function of the optical system (leading to high-frequency cutoff), accompanied by spatially varying point spread function (PSF), nonlinear aberrations, and complex sensor noise (such as dark current and readout noise), which simple digital interpolation cannot capture. This difference between simulated data and real physical imaging scenarios may limit the model’s generalization ability under extremely complex experimental conditions.

Future work will focus primarily on two aspects to bridge this gap. First, we will construct degradation models that better conform to physical laws. For example, we will use a process of “Gaussian low-pass filtering (simulating the diffraction limit) + noise injection + pixel binning” to replace simple digital downsampling or directly construct a training dataset based on real-world “wide-field-SIM” pairings to improve the model’s adaptability to real optical aberrations. Second, we will explore more general cross-modal super-resolution models to verify whether this method is applicable to other organelle combinations (such as mitochondria and microtubules), thereby developing a general multicolor super-resolution imaging framework.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the image quality degradation caused by photon budget constraints in weak signal channels (such as DAPI) during fluorescence microscopy. A multi-channel collaborative super-resolution reconstruction framework based on SwinIR was constructed and validated. Unlike traditional single-channel methods, this study proposes a cross-modal structural prior strategy. By fusing the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) blue DNA channel with the high SNR, structurally clear green FITC channel, cross-channel feature extraction and information compensation were achieved using the attention mechanism of SwinIR. Essentially, this method transforms the image restoration task from a single pixel-level regression into solving a physical inverse problem based on structural constraints, effectively overcoming the ill-conditioned nature of weak signal imaging.

Experimental results demonstrate that this multi-channel strategy achieves significant breakthroughs in both quantification metrics and visual quality. In the reconstruction of the DAPI channel, compared to the single-channel baseline model, the multi-channel SwinIR significantly improves the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) from 27.05 dB to 44.98 dB and the structural similarity (SSIM) from 0.763 to 0.960. Visual and frequency-domain analyses show that this method not only effectively suppresses random noise in the background region, but, more importantly, it successfully recovers high-frequency edge information that is submerged by noise, without introducing common ringing effects or structural artifacts.

Furthermore, this study validated the algorithm’s effectiveness in overcoming resolution limitations through physical-scale measurements. Multi-channel reconstruction reduced the minimum resolvable structural size of the image from approximately 1.5 μm to 0.8 μm, achieving sub-micron level detail resolution. This demonstrates the feasibility of using structural redundancy in long-wavelength channels to compensate for physical diffraction blur in short-wavelength channels. This “detail enhancement,” rather than simple “pixel magnification,” represents a substantial advancement in super-resolution technology within the field of microscopic imaging.

In summary, this study not only established a complete multi-channel microscopic image super-resolution modelling workflow but also provided a highly promising engineering solution for biomedical imaging. This method allows for high-quality nuclear imaging through computational means while maintaining low-dose excitation and reducing phototoxicity, which has significant application value for long-term live-cell observation and high-throughput drug screening. Future work will further expand to more complex real-world degradation models and more diverse organelle combinations to promote the application of this technology in general-purpose multi-color super-resolution imaging.

Author Contributions

For this work, H.H. took charge of methodology development, software design and implementation, method validation, formal analysis of experimental data, research direction investigation, data curation, preparation of the manuscript’s original draft, visualization of results, as well as review and editing of the manuscript. H.A. was responsible for the conceptualization of the study, provision of relevant resources, supervision of the overall research process, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The microscopy dataset used in this study was accessed through the University of Glasgow data infrastructure and is subject to institutional data governance and access restrictions. Therefore, the full dataset cannot be made publicly available by the authors. To support reproducibility, the authors can provide (i) preprocessing and training scripts, (ii) the trained model weights, and (iii) a limited subset of anonymized sample pairs for benchmarking upon reasonable request, subject to institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the teaching and research team of the University of Glasgow for their academic guidance during the research process. Thanks are also extended to the technical support staff who provided assistance in the experimental process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GT | Ground Truth |

| HR | High Resolution |

| LR | Low Resolution |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| Q/K/V | Query/Key/Value |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| RSTB | Residual Swin Transformer Block |

| SIM | Structured Illumination Microscopy |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SR | Super-Resolution |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| STL | Swin Transformer Layer |

| W-MSA | Window-Based Multi-head Self-Attention |

References

- Lichtman, J.W.; Conchello, J.A. Fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, D.J.; Allan, V.J. Light microscopy techniques for live cell imaging. Science 2003, 300, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, J.C. Accuracy and precision in quantitative fluorescence microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monici, M. Cell and tissue autofluorescence research and diagnostic applications. Biotech. Histochem. 2005, 80, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, M.; Gabel, D. Fluorescence properties of DAPI strongly depend on intracellular environment. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2002, 117, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, I. Fluorescent probes for living cells. In Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M.G.L. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Microsc. 2000, 198, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demmerle, J.; Innocent, C.; North, A.J.; Ball, G.; Müller, M.; Miron, E.; Matsuda, A.; Dobbie, I.M.; Markaki, Y.; Schermelleh, L. Strategic and practical guidelines for successful structured illumination microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 988–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, Z.H.; Müller, M.; Hübner, W.; Wang, T.C.; Telman, D.; Huser, T.; Schenck, W. Evaluation of Swin Transformer and knowledge transfer for denoising of super-resolution structured illumination microscopy data. GigaScience 2024, 13, giad109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Yao, Y.; He, Y.; Huang, Z.; Luo, F.; Zhang, C.; Qi, D.; Jia, T.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; et al. Surpassing the resolution limitation of structured illumination microscopy by an untrained neural network. Biomed. Opt. Express 2023, 14, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Song, Q.; Zhang, P. A Visual Enhancement Network with Feature Fusion for Image Aesthetic Assessment. Electronics 2023, 12, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Geng, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, J.; Meng, Q.; Qiao, H.; Dai, Q. A neural network for long-term super-resolution imaging of live cells with reliable confidence quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image restoration using swin transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, M.V.; Choi, U.J.; Burchi, M.; Timofte, R. Swin2sr: Swinv2 transformer for compressed image super-resolution and restoration. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 669–687. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.; Gang, S.; Guan, C. FCIHMRT: Feature cross-layer interaction hybrid method based on Res2Net and transformer for remote sensing scene classification. Electronics 2023, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-esrgan: Training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H.M.; Tseng, W.M.; Lin, J.W.; Tan, G.L.; Chu, H.T. Enhancing Image Super-Resolution Models with Shift Operations and Hybrid Attention Mechanisms. Electronics 2025, 14, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, R.F.; Jacquemet, G.; Krull, A. Imaging in focus: An introduction to deep learning for microscopists. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 139, 106050. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Dragotti, P.L. Deep coupled feedback network for joint exposure fusion and image super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 30, 1450–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkert, M.; Rueden, C.T.; Allan, C.; Burel, J.M.; Moore, W.; Patterson, A.; Loranger, B.; Moore, J.; Neves, C.; Macdonald, D.; et al. Metadata matters: Access to image data in the real world. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandram, D.; Taylor, G.W. Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.S.; Huang, J.B.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, M.H. Deep laplacian pyramid networks for fast and accurate super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 624–632. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep CNN for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.