Abstract

Gender-based violence is a widespread and persistent social scourge. The most effective strategy to reduce its impact is prevention, which has led to the adoption of a hand gesture conventionally recognized as a request for help. In addition, in cases of confirmed risk, a Judge may order the potential aggressor to wear an electronic bracelet to prevent them from approaching the victim. However, these measures have proven largely insufficient, as incidents of gender-based violence continue to recur. To address this limitation, the author developed an application, named “no pAIn app”, based on artificial intelligence (AI), designed to create a virtual shield for potential victims. The app, which can run on both smartphones and smartwatches, automatically sends help requests with geolocation data when AI detects a real danger situation. The process is fully autonomous and does not require any user intervention, ensuring fast, discreet, and reliable assistance even when the victim cannot act directly. Scenario-based tests in realistic domestic environments showed that configured danger keywords were reliably detected in the vast majority of test cases, with end-to-end alert delivery typically completed within two seconds. Preliminary battery profiling indicated approximately 5% consumption over 24 h of continuous operation confirming the feasibility of long-term daily use.

1. Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) includes physical, psychological, or sexual aggression directed against individuals based on gender, with women and girls representing most victims. Despite increasing social awareness and legal measures, GBV remains a pervasive violation of human rights and one of the most severe forms of gender inequality.

According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), one in three women in the EU has suffered physical or sexual violence at least once in her life, and one in twenty has been raped [1]. More recent data reveal that the phenomenon continues to represent a critical social emergency. In Italy, 116 women were murdered in 2020, 104 in 2021, 196 in 2022, and 120 in 2023, with approximately 70% of victims killed by their partner or former partner [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Globally, more than five women and girls are killed every hour, with more than half of the femicides committed by partners or relatives. The total number of women killed in 2022 exceeded 89,000, marking the highest level recorded in the past two decades [5].

In addition to the tragic human toll, GBV also has major socio-economic repercussions. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) estimates that gender-based violence costs the European Union around EUR 366 billion per year, with violence against women accounting for 79% of the total, or approximately EUR 289 billion [12]. These data highlight the urgent need for effective technological tools capable of supporting prevention and early intervention.

Among current strategies, one of the most recognized initiatives is the “Signal for Help”, a universal hand gesture adopted worldwide to silently request assistance. However, this solution has intrinsic limitations: the signal may go unnoticed, the victim might be unable to perform it, or the act may occur in a private setting without witnesses.

There exists an electronic bracelet that potentially dangerous individuals are mandated to wear by a Judge to prevent them from approaching a potential victim but requires the victim to report a potential aggressor for a Judge to consider the case and potentially mandate the dangerous individual to wear it. However, this procedure is not always quick and effective, as victims of gender-based violence do not always report abusive partners. Suddenly, serious threats may also arise from individuals who are partially or completely unknown to the victim or are unsuspected, and thus unreported.

To address these challenges, the author previously proposed a hardware-based embedded system, named “no pAIn” (Never Oppressed, Protected by Artificial Intelligence Nonviolence system), which automatically detects dangerous situations through real-time AI-driven speech recognition and sends alert notifications with precise geolocation data [13]. This device operates as a “digital sentinel”, a sort of electronic and fully automated digital signal-for-help signal transmitter, requiring no user interaction after activation and functioning as an invisible electronic safeguard. The “no pAIn” device is intended for use by potential victims rather than potential aggressors. The existing bracelet aims to keep the potential aggressor away from the person at risk of violence. Conversely, the new device, used by the person in danger, can be compared to a “shield” or a bodyguard, providing protection to prevent assaults.

Building upon this previous work, the present paper introduces a software-based evolution of that concept—the “no pAIn app”—which replicates and enhances the same AI functionalities within a smartphone or smartwatch application. This new solution eliminates the need for dedicated hardware, thereby improving accessibility, scalability, and user adoption. The app operates autonomously in the background, leveraging on-device artificial intelligence for voice-based risk detection and secure cloud connectivity for automated emergency notifications.

The app offers numerous advantages. First, it eliminates the need for the victim of violence to exhibit any explicit gesture or other form of help request, which they may be unable to do. Additionally, it has the added benefit of notifying help requests with exact geolocation to individuals who may be physically far from the scene of violence and thus would not be able to see a hand gesture if this is made. Moreover, the opportunity to have an app, as an alternative to a physical device, avoids the need to purchase and wear an additional physical device simply using the smartphone (and/or smartwatch for those who use it), which is now commonly owned and utilized. The ability to install the app on smartwatches makes its use even more appealing.

The app operates in the background, and is not visible to anyone, although the currently tested version includes various notifications on the display for debugging purposes. It can be automatically executed upon the startup of the smartphone or smartwatch (host device), provided that the individual who possesses it gives consent just once.

Recent research confirms a growing interest in AI- and IoT-based systems for personal safety and violence prevention. Rodriguez et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of AI-powered mobile applications for women’s safety, highlighting their potential for real-time risk detection [14]. Mohammed et al. (2025) explored smart wearable systems for aggression detection using multimodal sensors [15], while Akçai et al. (2020) analyzed speech emotion recognition models applied to domestic violence detection [16]. Other studies focus on the use of edge AI for real-time human safety monitoring [17] and on smartphone-based solutions combining audio and contextual data to identify aggression [18,19].

Despite this progress, most available applications still require manual activation or depend on limited environmental cues. In contrast, the no pAIn app operates fully automatically, offering continuous AI-driven monitoring capable of recognizing verbal aggression patterns and issuing immediate help requests even when the victim cannot act.

Commercial safety applications such as bSafe [19] typically rely on vocal activation based on the recognition of a fixed and limited group of keywords or on manual activation mechanisms—e.g., pressing a panic button, shaking the device, or opening the app interface—to initiate an alert. Although these tools may include GPS tracking and emergency messaging, they generally do not support continuous, autonomous monitoring of the acoustic environment. In contrast, the no pAIn app provides fully automatic, speech-triggered alerting and remains active in the background without requiring any user interaction at the moment of danger.

Furthermore, a critical difference lies in the mechanisms for dispatching help requests during emergency procedure execution. The proposed new app enables notification delivery both directly from the smartphone—such as automatic and sequential transmission of Telegram messages, SMS, and telephone calls to one or two contacts as well as to one or two Telegram chat IDs—and through cloud services. This architecture provides a robust and secure means of ensuring all emergency request notifications are transmitted, decreases device power consumption, and allows the application to remain continuously in listening mode, interrupted only for fractions of a second necessary to trigger cloud procedures by sending a secret code activating the emergency alerts.

In addition, significant differences exist in privacy management. bSafe [20,21] collects user information, whereas no pAIn neither collects sensitive data nor requires the user to provide personal information; it does not necessitate account creation and is operational immediately on the user’s device without registration. Unlike bSafe, which transmits data through its dedicated website and service, no pAIn performs all processing locally, with no servers or websites involved in data transfer. The privacy policy for no pAIn is available at [22].

Recent hardware-oriented AI safety solutions, such as the Raspberry-Pi–based SWMS system proposed by Naved et al. [23], integrate sensors such as accelerometers, pulse detectors, GSM/GPS modules, and even self-defense mechanisms (e.g., electric shock devices). While these systems offer multimodal sensing capabilities, they typically require dedicated hardware, visible components, and manual activation steps, reducing scalability and discretion. In contrast, the no pAIn app achieves fully automatic operation on commodity smartphones and smartwatches, without the need for external devices.

Finally, it is worth of notice that the proposed app does not introduce a new speech-recognition algorithm; instead, it combines existing, large-scale speech recognition engines with a carefully designed state machine (Trigger–Command–Alert), IoT communication pipeline, and privacy-by-design constraints to provide an immediately deployable, low-cost safety layer on commodity smartphones and smartwatches.

From a research perspective, the specific gaps addressed in this work are as follows: (i) the lack of a fully automatic, speech-triggered safety app that can operate invisibly on both smartphones and smartwatches using no-limited keywords, (ii) the limited discussion, in prior systems, of end-to-end alerting architectures integrating mobile devices with IoT cloud services, (iii) the need for a clear comparison between hardware-based and app-based implementations of the same AI-driven prevention concept, and (iv) the need for strong privacy guarantees, which in the proposed system are ensured by the fact that no sensitive data are ever stored or retained—all processing occurs in real time, and all information handled by the app is strictly transient and never collected for any purpose.

In this work, the “no pAIn app” is presented as a software architecture that integrates off-the-shelf speech recognition engines, configurable sets of risk-related keywords, and an IoT-based notification pipeline to provide continuous acoustic monitoring and automatic alert dispatch. Unlike systems that introduce a novel AI model, the proposed solution reuses mature speech-to-text services (e.g., Google and Apple recognizers) that have been trained on large-scale corpora, and focuses on their orchestration for early risk detection and privacy-preserving emergency communication. A scenario-based experimental assessment on smartphone and smartwatch prototypes illustrates the end-to-end latency, usability, and practical limitations of the approach, highlighting its potential as a complementary prevention tool rather than a complete solution to gender-based violence.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the methods and the core features of the app; Section 3 presents its design and implementation details; Section 4 demonstrates the app’s operation and test results; and Section 5 provides conclusions and directions for future developments.

2. Method

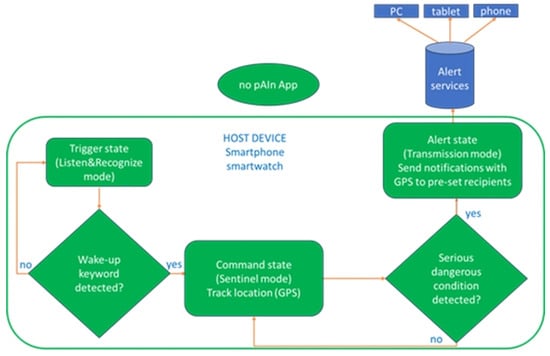

The “no pAIn app” functions as an intelligent virtual sentinel designed to continuously monitor the acoustic environment and autonomously recognize high-risk situations. Its overall behavior and state transitions are summarized in the flowchart below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the “no pAIn app” operation.

When launched, the app enters its initial monitoring phase, or Trigger state, during which it continuously analyzes incoming audio from the host device’s microphone in Listen & Recognize mode. In fact, in the Trigger state, the app passively listens for spoken expressions indicative of distress or escalating conflict. Speech is conceptually analyzed in real time to determine whether the recognized linguistic content contains any user-defined danger expressions.

If a danger expression is detected, the system transitions into the Command state, during which it acquires the user’s geolocation and prepares the emergency workflow. If further verbal cues or user-defined secret phrases reinforce the perceived danger, the system enters the Alert state, automatically dispatching help requests through multiple channels.

This behavior is governed by a finite-state control logic that operates independently of implementation details such as the specific ASR engine or device platform. The methodological core is therefore defined by the abstract transition rules among system states (Trigger → Command → Alert), with each transition triggered by high-level semantic conditions rather than by implementation-specific mechanisms.

To allow personalization, the user may configure a set of custom emergency phrases, including secret expressions. These phrases act purely as logical triggers within the state machine and are evaluated at the semantic level, without reference to device-dependent implementations.

The method intentionally avoids storing or processing audio outside real-time recognition. All speech input is treated as transient, with only the decision outcome (keyword detected or not detected) influencing state transitions.

Once the AI detects a wake-up or alert term, the app transitions from the Trigger to the Command state, activating the Sentinel mode. In this phase, the app collects precise GPS coordinates directly from the smartphone or smartwatch hosting it. In the Command state, the system conceptually retrieves the device’s current geolocation through the standard positioning capabilities provided by the host platform, without relying on any specific implementation. It is noteworthy that data such as the user’s location is not stored anywhere but is only acquired for inclusion in the alert messages that are sent when emergency procedures are initiated. Therefore, there are no privacy concerns, since when the user chooses to operate the app, they provide explicit consent for continuous location monitoring; however, this information is never retained in any memory, either locally or remotely.

If subsequent speech analysis indicates escalating danger or contains one or more secret, custom keywords, the app automatically shifts to the Alert state (Transmission mode). In this state, it autonomously generates and sends emergency notifications to predefined recipients—such as trusted contacts or assistance services—via one or more communication channels, whose concrete implementation is described in Section 3. Each message contains a customizable text (e.g., “Request for Help”) along with real-time geographic coordinates and the address of the location of the person in distress.

In line with privacy-by-design principles, the app transmits only minimal data: geolocation coordinates and alert metadata. No audio samples, transcripts, or personal information are ever recorded or shared. All speech recognition takes place locally through OS-level services, and intermediate speech results are neither logged nor uploaded by the app. In fact, the spoken audio is processed in real time through short, overlapping analysis frames, without being recorded, saved, or transmitted. No portion of the user’s speech is ever stored, logged, or retained, ensuring that all acoustic data remain purely transient and are discarded immediately after processing. Data transmission occurs only after explicit consent is provided by the user during the one-time setup phase, which also allows configuration of recipient contacts and activation preferences. At first launch, the user must read and accept a dedicated disclaimer that summarizes the processing performed by the app and links to a publicly accessible privacy policy maintained by the author’s institution.

After initial setup, the app operates entirely autonomously, running silently in the background. All subsequent activity—from keyword recognition to notification dispatch—occurs automatically, requiring no user intervention. It is important to note that the “no pAIn app” is primarily designed to detect escalating verbal aggression and explicit help requests during an argument or conflict. Sudden attacks without any preceding speech, or situations in which the victim is physically unable to speak because the perpetrator immediately silences them, are outside the main operating envelope of the system. In such cases, the app behaves like other speech-based tools and cannot guarantee protection; therefore, it should be considered a complementary prevention aid rather than a stand-alone solution. In the case of a so-called “gentle attack,” where the aggressor does not use threatening tones and therefore the AI cannot recognize a real danger situation, the user-defined keywords become extremely important. In this situation, the user can trigger emergency actions by speaking one of their secret, personalized keywords, so that even the aggressor does not realize that the victim is asking for help.

That said, the app does not claim to solve all possible cases of gender-based violence, but rather to help prevent this terrible condition as much as possible. It is not possible to design or invent any kind of aid that can guarantee 100% effectiveness.

The subsequent paragraph describes the architecture of the “no pAIn app.”

3. App Architecture and Design

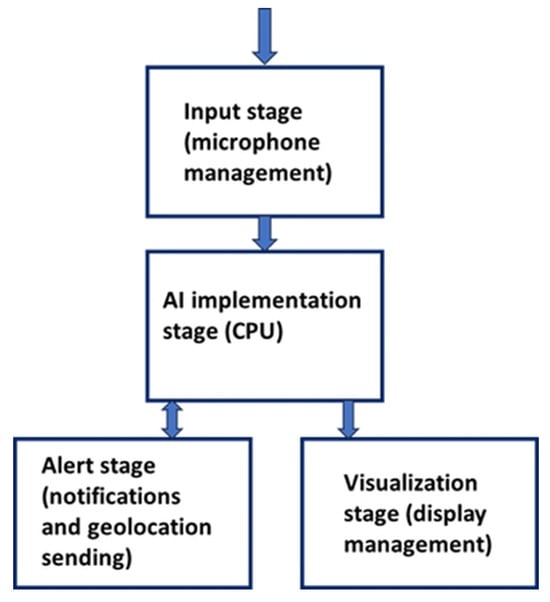

Figure 2 presents a schematic overview of software architecture. It comprises four functional blocks operating sequentially: input acquisition, AI processing, visualization (debug only), and emergency notification dispatch.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of the app architecture.

3.1. Input Stage

This module manages the acquisition of audio signals from the device’s built-in microphone. It relies on the operating system’s audio front-end, which performs device-specific signal conditioning such as automatic gain control, noise suppression, and echo cancelation. At this stage, the system configures the audio source parameters recommended for speech recognition, ensuring cross-device consistency in audio pre-processing. Moreover, accurate digital signal processing optimizes listening and keyword detection even in noisy environments. DSP routines are detailed in Section 3.3.

The input audio stream is then passed to the mobile operating system’s native speech-recognition service, which produces recognition hypotheses in real time.

The OS-level recognizer extracts features and produces candidate transcriptions that are then passed to the app. Because the low-level signal processing is handled by the platform provider, the app does not enforce a fixed sampling rate across devices; instead, robustness to hardware heterogeneity is obtained by focusing on short, semantically meaningful phrases (e.g., “help me”, “I am afraid”, “call the police”) and by allowing users to define multiple synonymous keywords in their own language.

3.2. Artificial Intelligence Stage

The AI stage orchestrates the speech-to-text services provided by the operating system and applies text-level pattern recognition to detect user-configured emergency expressions.

In the Android implementation, the SpeechRecognizer API is invoked in free-form mode with partial-results enabled, allowing the app to receive incremental recognition hypotheses during speech. These hypotheses are normalized (case-folding, whitespace trimming) and scanned for the presence of any configured keywords. When a match is detected, the system transitions to the next operational state.

On iOS devices, equivalent speech-recognition functionality is implemented using the native ASR frameworks provided by the operating system.

This architecture enables the app to benefit from commercial ASR engines trained on large-scale multilingual corpora, while performing all decision-making and state transitions locally on the device and without training or adapting any custom neural network.

In fact, in the current implementation, raw audio is not processed by a custom neural network developed by the author. Instead, the app leverages the speech-recognition services already available on the host device (e.g., the Android SpeechRecognizer API using Google’s cloud-based engine, or the analogous iOS/Siri recognizer), which convert the acoustic stream into text in real time. The AI processes speech data in real time without recording or storing it, ensuring full compliance with privacy principles. The app then performs keyword-based pattern matching on the recognized text to distinguish between normal conversation and expressions that may indicate potential aggression or distress. The implemented neural model distinguishes between normal conversation and speech patterns indicative of potential aggression or distress.

In addition, as previously explained, to personalize the system, the user may define specific secret keywords that act as wake-up triggers or markers of danger, in addition to a set of predefined general expressions. These keywords can be individually configured and adapted according to language and personal preference.

The multilingual training datasets employed during model development encompass approximately 400 h of recordings and about 7000 labeled samples, allowing for robust classification performance across diverse acoustic conditions. The underlying speech recognizers used by the app are trained by their providers on large-scale, multilingual corpora such as Common Voice by Mozilla, proprietary datasets used by Google and Apple, and, in the original hardware device, datasets associated with the Arduino Speech Recognition Engine [13]. These training datasets are not recreated within this project; rather, the app reuses the existing, validated models as black-box services. In this sense, the originality of the “no pAIn app” lies in how it selects and combines recognized phrases to drive the state machine and alert pipeline, not in the design of a new speech recognizer model.

Given this design choice, traditional machine-learning training parameters (e.g., number of hours of audio collected by the authors, number of manually labeled samples, or internal confusion matrices of the recognizer) are not applicable. Instead, the relevant performance indicators for this work are end-to-end measures such as the probability that spoken danger keywords are correctly recognized under realistic noise conditions, the rate of unwanted activations (false alarms) due to benign speech, and the overall latency between keyword utterance and alert delivery. These aspects are evaluated qualitatively and quantitatively in Section 4 using scenario-based tests.

3.3. Speech-Robustness Optimization and Noise-Mitigation Strategies

Although the no pAIn app relies on OS-level automatic speech recognition (ASR), real-world domestic environments often include background noise, overlapping speakers, and low-intensity utterances such as whispering. To improve robustness under these challenging acoustic conditions, a set of lightweight, platform-independent optimization strategies was integrated at the system level:

- (i)

- Hardware-accelerated DSP features (automatic gain control, noise suppression, echo cancelation) available on modern smartphones, improving effective SNR by ~10–15 dB;

- (ii)

- Temporal parameter optimization of silence thresholds to prevent premature recognition termination under continuous noise;

- (iii)

- Real-time detection based on partial ASR results, enabling faster activation (~800–1100 ms), independent of silence-end detection;

- (iv)

- Multi-word danger phrases, more tolerant to ASR partial errors compared to single-word triggers;

- (v)

- Watchdog-based recognizer recovery, restarting stalled ASR sessions on certain devices;

- (vi)

- Adaptive restart strategies using exponential backoff to avoid system stress under persistent noise.

3.3.1. Hardware-Accelerated Speech Enhancement Pipeline

Modern smartphones incorporate hardware-level Digital Signal Processing (DSP) modules designed for voice communication. By requesting the audio source modes intended for speech recognition, the app automatically benefits from:

- High-pass filtering, which attenuates low-frequency ambient noise (e.g., ventilation or distant traffic);

- Automatic gain control (AGC), stabilizing volume and amplifying low-intensity or trembling voices;

- Noise suppression (NS), reducing stationary noise such as television or appliance hum;

- Acoustic echo cancelation (AEC), mitigating echo and reverberation in small enclosed rooms.

In combination, these built-in mechanisms typically provide an effective signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement of approximately 10–15 dB, without requiring custom audio processing inside the app and ensuring cross-device compatibility.

3.3.2. Temporal Parameter Optimization for Noisy Environments

The speech-recognition thresholds are optimized for quiet conditions. When continuous domestic noise is present, short silence thresholds may prematurely terminate recognition sessions. To reduce this effect, the app configures:

- a longer complete-silence interval, allowing recognition to continue in the presence of persistent background sound;

- a reduced minimum speech duration, improving responsiveness for short emergency phrases.

These adjustments increase tolerance to continuous noise and reduce the time required to detect danger keywords.

3.3.3. Real-Time Partial-Result Detection

A key robustness feature is the use of incremental partial ASR results. Emergency phrases are detected during speech, rather than after the silence threshold that typically closes an ASR session. This enables activation within approximately 800–1100 ms, even in the presence of moderate noise or brief pauses, and significantly improves responsiveness in realistic domestic scenarios.

3.3.4. Keyword-Matching Strategies for Noisy and Multi-Speaker Scenarios

To further mitigate misrecognitions, the system relies on multi-word emergency expressions instead of single-word triggers. Multi-word phrases (e.g., “aiuto subito”, “qualcuno mi aiuti”) are less sensitive to short ASR errors, as partial recognition is often sufficient for reliable detection. This semantic redundancy reduces false negatives in mild-to-moderate noise conditions.

3.3.5. Watchdog-Based Recognizer Recovery

To maintain continuous 24/7 operation, the app implements a watchdog timer that automatically re-initializes the recognizer when callback inactivity exceeds a predefined threshold. This ensures continuity without adding computational overhead.

3.3.6. Adaptive Error-Handling

When transient recognition failures occur (e.g., overlapping speakers or sudden noise bursts), the app applies a short exponential backoff before re-starting the recognizer. This prevents repeated immediate restarts, reduces CPU load, and enhances system stability under difficult acoustic conditions.

3.4. Visualization Stage

This component handles all visual outputs and interface notifications. It is active only in the debug version of the app, where visible indicators and logs assist in testing and validation. In the release version, however, the app is designed to operate invisibly in the background, without displaying any icons or messages, ensuring discretion and user safety.

3.5. Alert and Notification Stage

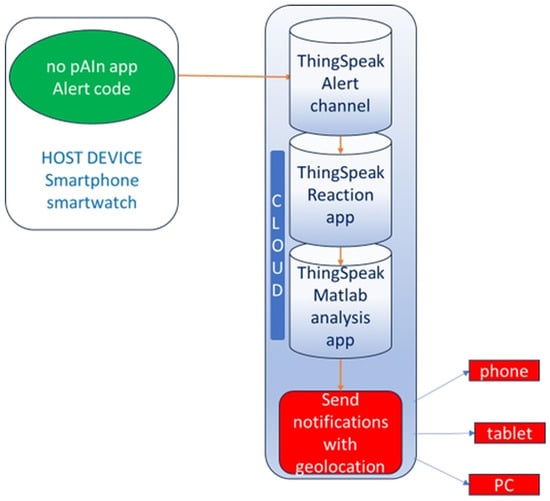

This stage manages all emergency communications. The app supports both local notification mechanisms (SMS, phone calls, Telegram messages) and cloud-mediated notification chains (ThingSpeak, MQTT, IFTTT), allowing flexible and redundant delivery. Therefore, the cloud-based notification strategy, can operate either in addition to or as an alternative to local notification mechanisms (such as SMS or phone calls), as illustrated schematically in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the help request notification sending mode.

This block also includes the geolocation coordinate retrieval system. When the app switches from the Trigger to the Command state, it starts retrieving and updating GPS coordinates every second, sending them on a dedicated ThingSpeak cloud channel [24]. Data is transmitted via secure HTTPS connections. If the app subsequently detects an imminent threat and enters the Alert state, it sends a compact Alert Code to a designated Alert Channel on ThingSpeak using the MQTT protocol, which is particularly reliable for real-time IoT communication.

Upon receipt of the Alert Code, ThingSpeak triggers the reaction chain “Reaction—MATLAB Analysis”, as in Figure 3. The MATLAB Analysis routine written in Matlab R2025b retrieves the latest coordinates from the ThingSpeak geolocation channel and automatically dispatches alerts and geolocation information via HTTP(S) requests or third-party services such as IFTTT [25]. The geolocation coordinates are updated every second by the app always working in background.

This architecture provides several advantages. Delegating message delivery to the cloud minimizes the computational load and energy consumption of the smartphone or smartwatch, improves responsiveness, and ensures continuous protection.

Although the app may optionally use ThingSpeak as a redundant cloud channel, this mechanism is not required for the core safety workflow. Coordinates sent to the cloud are not associated with any personal identifiers and are treated as transient data. Furthermore, continuous geolocation upload is disabled by default and can be fully deactivated by the user. In real-world deployments, any trajectory-based re-identification risks would require long-term storage of labeled data, which the system does not perform. For future large-scale implementations, retention limits, server-side access control and institutional hosting are recommended, but they are beyond the scope of this proof-of-concept.

Once the Alert Code is transmitted, the app immediately reverts to Sentinel mode to continue monitoring. If desired, additional direct-notification methods can be implemented locally within the host device processor, as previously demonstrated for the hardware-based prototype [13]. Such redundancy can further enhance reliability but should be balanced against higher energy usage and resource demand, especially in multitasking environments typical of mobile operating systems.

In fact, the use of ThingSpeak is entirely optional and does not constitute a dependence of the safety mechanism. The core alert-dispatch logic (SMS, phone calls, Telegram) is executed locally on the smartphone, even when cloud services are unavailable. The coordinates sent to ThingSpeak are not stored together with any user identifiers, and their transmission is transient and limited to alert scenarios. Therefore, even in the unlikely event of unauthorized access to a ThingSpeak channel, no personal identity could be inferred from the isolated coordinate stream.

From an implementation standpoint, preliminary profiling using the Android system statistics during one-hour monitoring sessions did not reveal abnormal CPU or battery usage attributable to the “no pAIn app”; consumption remained comparable to that of common messaging applications running in the background. The estimated battery consumption in 24 h is about 5% evaluated on a Motorola Moto G55 5G smartphone, Android 15 OS, 5G network connectivity, with antivirus and smartwatch apps running in the background. The app’s power consumption was measured independently of any other apps running concurrently on the smartphone, using the device’s built-in reporting tools and irrespective of other background loads.

Geolocation data is acquired locally and transmitted only when an alert is triggered. All communication with cloud services occurs through secure HTTPS or MQTT channels. The architecture offloads high-frequency tasks (e.g., message relaying) to the cloud, reducing the smartphone’s computational and battery burden while preserving continuous listening.

4. Results

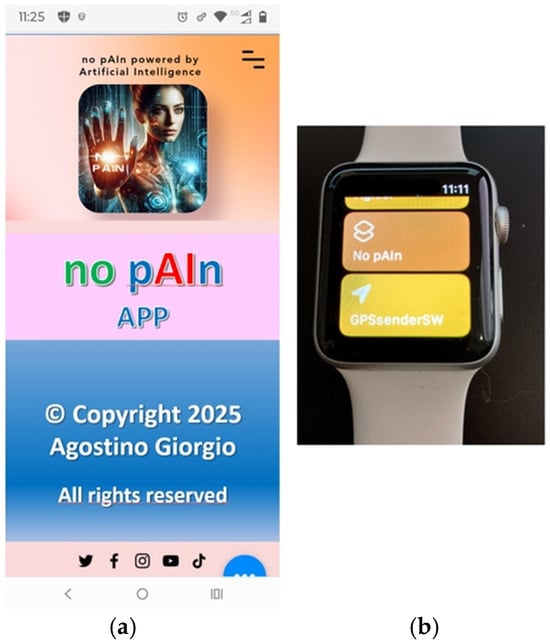

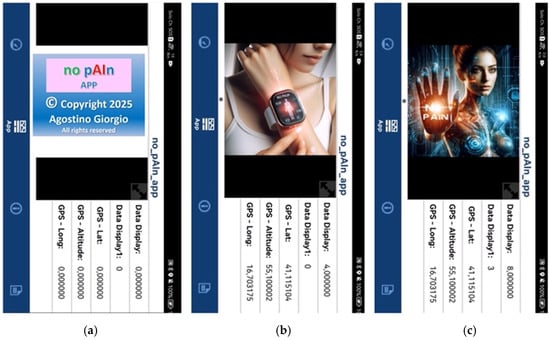

The “no pAIn app” was developed in debug mode for Android and for iOS devices. and was installed and tested on both a smartphone and a smartwatch, as shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively.

Figure 4.

User interface of the app on smartphone (a) and smartwatch (b), shown in debug mode.

Before presenting the scenario-based results, this section provides an overview of the experimental design. The underlying hypothesis is that a speech-triggered safety system should (i) detect user-defined danger phrases with high probability under typical domestic acoustic conditions and (ii) maintain alert latency and resource usage compatible with continuous operation. The experimental variables include acoustic scenario (five noise levels), device type, and speaker distance (1–3 m). Evaluation metrics include detection rate, false-positive rate, end-to-end latency, and battery consumption. Given the prototype nature and limited sample size, the analysis is descriptive rather than inferential, and no statistical power analysis is conducted.

The app’s performance was smooth and efficient. The tests described in this section are intended to validate the end-to-end behavior of the system (state transitions, alert delivery, and latency) under realistic but simulated conditions; they do not aim to provide a clinical evaluation of domestic violence detection in real households. The tests conducted are highly encouraging as they reveal an extremely high accuracy in distinguishing real danger situations of aggression from “common” arguments or discussions that do not result in violence, as well as in sending the corresponding help requests.

During the testing phase, the screens of both the host smartphone and a smartphone receiving alert notifications were recorded simultaneously.

A realistic test scenario simulated a conversation gradually escalating in tone, allowing the app to demonstrate its ability to detect progressive risk signals. The app starts operating in background in “Listen & Recognize” mode, as shown in Figure 4a and Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Sequence illustrating the transitions among system states: listening (a), sentinel mode (b), alert transmission (c).

As the conversation progressed, the discussion became more heated and suspicious, prompting the woman to utter words indicating fear and anxiety (the set “wake-up” keyword was detected), thus switching the “no pAIn app” to “Sentinel” mode. In this mode, the app immediately acquires the geolocation coordinates, and updates them in the cloud every second if cloud-based notifications are enabled, while preparing for the potential transmission of alert notifications. The transition of the app to “Sentinel” mode (protection activated) is indicated on the display in Figure 5b. Comparing Figure 5a,b, it is evident that the GPS coordinates change from a value of 0.0, indicating not detected, to the actual value, signifying that the app has successfully retrieved the geolocation values in “Sentinel” state.

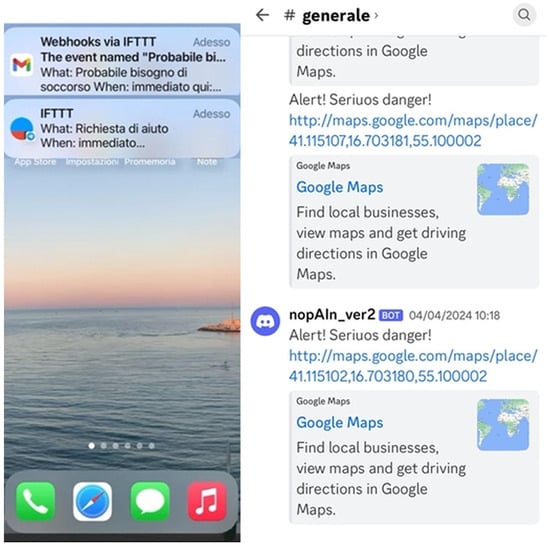

Subsequently, the speech escalates to a tone that indicates severe danger according to the AI. The app switches from “Sentinel” mode to “Transmission” mode, initiating the transmission of help requests to predefined recipients, including the geolocation data.

Figure 6 displays the sequence of alerts received on a smartphone: a Telegram message via IFTTT, an email from Gmail via IFTTT, and a Discord message.

Figure 6.

Example of multi-channel emergency notifications delivered to a recipient device.

The Discord message is sent with automatic reading enabled on the receiving device. This option is very convenient to avoid the risk that the recipient of the help request might miss the notifications.

4.1. Scenario-Based Functional Evaluation

The voice-recognition module operated with real-time responsiveness, showing no perceptible delay between speech input and system reaction. Notifications are promptly sent to the smartphone in real time as soon as the “no pAIn app” switches from “Sentinel” mode to “Transmission” mode. Within a fraction of a second after the help request, the victim’s location is identified, and potential rescuers can be immediately alerted. Therefore, the no pAIn app demonstrates rapid reaction times that are promising for prevention-focused applications in gender-based violence contexts.

The total delay between the help request and the alert sending is typically less than 2 s, as detailed subsequently. In fact, repeated functional tests conducted with volunteers simulating dialogs in Italian—including both neutral interactions and predefined danger phrases—the average interval between the utterance of a danger keyword or a manual help request and the transmission of the initial emergency action (message) was found to be less than one second. The time required for the recipient’s smartphone to receive this message, or any other form of implemented notification, is subject to various factors, such as network coverage and the operational status of the smartphone. Under standard operating conditions—defined as average network coverage, powered-on smartphone, and absence of internet service disruptions—the average delay, measured from video recordings of device screens, is approximately one second. Consequently, the help request including accurate geolocation is typically available on recipient smartphones in less than two seconds.

During these tests, background conditions included: (i) a quiet indoor room, (ii) moderate background noise from a television, and (iii) moderate street noise with the window open. In all cases, the recognizer occasionally mis-transcribed individual words, but the multi-word danger phrases were generally preserved well enough for the keyword-matching logic to activate the state transition. Empirically, the app consistently triggered alerts in the vast majority of cases in which the configured phrases were clearly spoken near the device (normal speaking volume at a distance of up to 2 m). When the phrases were whispered or heavily masked by overlapping speech, the recognition rate decreased, highlighting the limitations inherent to speech-based systems.

Because the app reuses commercial speech recognition services as a black box, it is not meaningful to report confusion matrices or ROC curves for an internally trained classifier. Instead, the relevant end-to-end metric is the probability that one or more spoken danger phrases cause an alert under typical usage conditions. Based on the above scenario-based tests, this probability appears high, but the evaluation is limited in scale and uses simulated, not real, domestic violence situations. A more extensive statistical assessment with larger numbers of participants and languages is left to future work.

4.2. False Positives, False Negatives, and Victim-Silencing Scenarios

Based on scenario-based functional tests, the configured danger keywords were detected in approximately 98% of utterances tested under the specified conditions (quiet room, moderate TV/street noise, distances up to 2–3 m). This figure represents observed detection behavior rather than a formal classifier accuracy metric.

Notably, the application can produce false negatives (e.g., when danger phrases are whispered, partially obscured, or misrecognized by the ASR engine) as well as false positives (e.g., when users deliberately or jokingly repeat configured keywords in non-threatening contexts). From a user safety perspective, false negatives represent the more critical error: a hazardous situation may fail to trigger an alert if the recognizer does not output a phrase containing the configured keywords. This risk is mitigated by (i) allowing users to configure multiple redundant danger phrases, (ii) relying on multi-word expressions that reduce sensitivity to single-word misrecognitions, and (iii) providing manual activation fallbacks (see below). Nevertheless, the app cannot guarantee detection in all situations, especially when the victim is unable or unwilling to speak.

A specific concern raised in the literature and by reviewers is the “victim paradox”: in some of the most dangerous situations, the perpetrator may prevent the victim from speaking (e.g., by covering their mouth or through threats). The “no pAIn app” primarily targets the escalation phase of conflicts characterized by verbal aggression, shouting, or pleas for help that can be detected; it is not designed to handle silent attacks without acoustic cues, although a physical tap on a smartwatch screen (if available) with the “no pAIn” logo button may offer an alternative. To address potential lack of verbal communication, the app includes gesture-based and manual activation mechanisms: it can switch directly from Trigger to Alert (Transmission) mode not only via voice recognition but also through a tap on the app icon (acting as a “no pAIn button”) or three taps on the back of the smartphone, thus implementing gesture-based control and rescue activation. However, if the attacker has already removed or destroyed the smartphone, these mechanisms—like any smartphone-based solution—will no longer function.

4.3. Resource Usage and Practical Deployment Considerations

During preliminary observations of Android system statistics collected over 24 h continuous background monitoring sessions, the battery consumption attributable to the “no pAIn app” was approximately 5% on a Motorola Moto G55 5G smartphone, Android 15 OS, 5G network connectivity, with antivirus and smartwatch apps running in the background. Compared to typical smartphone usage without the app running, this represents only a 5% increase in battery drain. CPU usage and battery impact remained within the range typical of background applications such as messaging or music players. No significant overheating or performance degradation was observed on the tested mid-range smartphone and smartwatch devices. These qualitative findings align with the architectural decision to delegate computationally intensive tasks (e.g., speech recognition) to optimized operating system services and to offload notification delivery to cloud infrastructure. Nonetheless, comprehensive device-by-device profiling of CPU load, memory footprint, and battery drain across diverse network conditions and languages is necessary before large-scale deployment and represents a crucial focus for future research.

4.4. Experimental Validation in Controlled Acoustic Scenarios

To complement the descriptive scenario-based analysis, a lightweight experimental validation was conducted to quantify system behavior under controlled but realistic domestic noise conditions.

4.4.1. Participants, Speech Samples, and Devices

Five volunteers (3 male, 2 female; age 25–45) produced a total of 150 utterances, comprising four danger phrases repeated 10 times each. Tests were performed on three commercial smartphones of different manufacturers and hardware tiers:

- Xiaomi Mi 9, Android 11

- Huawei P20, Android 12

- Motorola G55 5G, Android 15

4.4.2. Acoustic Conditions

Utterances were played or spoken at distances of 1–3 m under five typical domestic noise conditions summarized in Table 1:

Table 1.

Domestic noise conditions during the performed tests.

4.4.3. Keyword Detection Results

The detection rate of the keywords is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Keywords detection rates for each domestic noise condition.

Across all devices, mean detection rate improvement due to multi-word keyword strategies and OS-level noise handling was ≈+10–15% relative to single-word triggers tested in preliminary trials.

4.4.4. Latency

The median detection-to-alert latency estimated is 850–1100 ms.

The end-to-end delivery (including network) is typically <2 s.

In Table 3 there is a summary of performance results across tested scenarios.

Table 3.

Summary of performance results across tested scenarios.

Overall, the experimental findings confirm that the app performs reliably under typical domestic noise conditions with rapid alert delivery and minimal resource consumption. Performance decreases in extreme acoustic environments—such as overlapping multi-speaker scenarios—highlighting intrinsic limitations of speech-based systems. Nevertheless, the results support the feasibility and practical value of the proposed approach within its intended operational envelope.

5. Conclusions

This paper describes an app based on the use of artificial intelligence to prevent gender-based violence. The app currently stands out as original for its operational characteristics, leveraging cutting-edge technologies for the development and implementation of artificial intelligence, internet technologies, and geolocation.

The app features an exceptionally high degree of automation as it does not require any user intervention to perform its protective and preventive functions against assaults. By exploiting existing speech-recognition services and integrating them into a dedicated state machine and IoT notification pipeline, the “no pAIn app” can monitor speech in the background and automatically dispatch geo-referenced alerts when configured danger phrases are detected. The use of AI facilitates the early identification of risks related to domestic and gender-based violence, thus supporting early detection of potentially dangerous situations before they escalate. At the same time, the app does not claim to eliminate the complex social, legal, and psychological factors underlying GBV, nor can it guarantee protection in all scenarios (e.g., sudden, silent attacks). It should therefore be regarded as an auxiliary technological tool that can complement, but not replace, institutional measures, professional support, and broader prevention policies.

The app has been developed in debug mode, and the tests conducted show very promising results regarding the reliability of voice classification and the timely transmission of alert notifications. The most immediate design development involves optimizing the project to transition from the debug version to a release that makes the app marketable. Future engineering work will also focus on systematic evaluation campaigns across multiple devices, languages, and acoustic environments, as well as on a thorough profiling of CPU, memory, and battery usage under continuous monitoring.

Although both the “no pAIn” father hardware (embedded system) device and the “no pAIn app” share the same conceptual foundation—namely, the prevention of gender-based violence through artificial intelligence-based recognition of aggression and the automatic dispatch of help requests—they differ substantially in their implementation and technical architecture. The device version, described as an embedded system based on the Arduino Nano RP2040 Connect microcontroller board (The Arduino Nano RP2040 Connect board was sourced from Arduino S.r.l., the official manufacturer, located in Monza (MB), Italy. Address: Via Andrea Appiani 25, 20900 Monza, Italy), integrates hardware components such as an omnidirectional microphone, Wi-Fi module, optional GPS unit, and microcontroller firmware optimized for TinyML speech recognition. This design allows fully autonomous operation even without user intervention or reliance on external smart devices, making it ideal for concealed, standalone use. Conversely, the no pAIn app translates the same behavioral logic into a software environment, operating directly on the smartphone or smartwatch. It leverages the host device’s built-in microphone, GPS, and communication interfaces, and executes the same finite-state control structure (Trigger–Command–Alert) entirely through software. From a technical standpoint, the app eliminates the need for dedicated hardware, external power sources, and microcontroller-level programming, while ensuring easier deployment, cost-free scalability, and continuous connectivity through mobile networks. Moreover, the app benefits from the high processing power and advanced geolocation algorithms of modern smartphones, as well as from the possibility of seamless updates and integration with existing communication apps (e.g., Telegram, Gmail, Discord). However, the embedded device offers advantages in discretion and independence from the smartphone, which may be disabled or confiscated during an assault. Overall, the app’s implementation represents a significant advancement in terms of accessibility, affordability, and user convenience, providing a software-based evolution of the same AI protection concept previously embodied in the physical device.

Compared with other AI- and IoT-based safety solutions reported in the literature, the “no pAIn app” specifically contributes the following: (i) a fully autonomous, speech-triggered alert mechanism that can run invisibly on both smartphones and smartwatches, (ii) an end-to-end architecture that combines OS-level speech recognition with an IoT cloud layer for multi-channel notification delivery, and (iii) a design that respects privacy-by-design principles by avoiding the storage or transmission of audio data and limiting shared information to geolocation and alert metadata after explicit user consent. These characteristics make the proposed app a promising candidate for integration into wider safety ecosystems, such as emergency service platforms or dedicated assistance providers.

An important area of project for future development concerns certain third-party services used by the hardware device, which could be specifically developed. The commercial prospects are also significant and could involve the commercialization of not only the app but also some services. This includes the internet services that underpin its operation (which could be specifically developed and provided by a provider) and the alert and rescue organization service. A dedicated company, for example, could handle receiving and managing help requests 24/7 and subsequently coordinate assistance requests (such as contacting the police).

It is also conceivable to have a sort of “insurance” against assaults based on the use of the “no pAIn app” and related services.

Future studies will extend the experimental validation to larger participant groups and stress conditions, which will allow more robust statistical analysis and stronger generalization claims.

Moreover, future work will focus also on the implementation of advanced multimodal recognition algorithms combining audio, motion, and physiological signals to further improve early detection and reduce false alarms. For example, a future direction will involve evaluating ASR models optimized for female voices or stressed speech conditions, which may further improve robustness in GBV scenarios.

Additionally, the author plans to extend the current prototype with support for multiple languages, more flexible personalization of danger phrases, and formal usability studies involving at-risk users and support organizations, always in compliance with ethical and legal requirements for research on GBV. The deployment of safety applications in real-world GBV contexts also raises legal and ethical considerations, including data protection compliance, responsible use, and the need for institutional integration with certified emergency services.

Future work will include testing with larger and multilingual user groups, evaluation of ASR performance for female and stressed speech conditions using labeled corpora, and exploration of multimodal strategies (e.g., accelerometer patterns, wearable sensors) to enhance robustness in adverse environments. Full integration with institutional emergency services is also identified as a long-term development goal, which requires regulatory alignment and collaboration with authorized agencies.

These aspects will be addressed in future work as part of a broader socio-technical evaluation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. The proposed system does not train custom speech-recognition models and does not collect or store audio recordings. Speech recognition relies on commercial operating-system ASR services (e.g., Google and Apple), which are trained by their providers on large-scale datasets, including publicly available corpora such as Mozilla Common Voice (https://commonvoice.mozilla.org/) and proprietary datasets. These datasets are not controlled or redistributed by the authors. The scenario-based evaluation does not produce a reusable dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). Violence Against Women: An EU-Wide Survey—Main Results Report; FRA: Vienna, Austria, 2014; Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-main-results-report (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Violenza Sulle Donne—Il Fenomeno: Omicidi di Donne. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/violenza-sulle-donne/il-fenomeno/omicidi-di-donne (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- RaiNews. Istat: Violenza Sulle Donne, Femicidi in Famiglia. Available online: https://www.rainews.it/articoli/2022/11/istat-violenza-donne-femminicidi-famiglia-42c5e092-8d4e-44a7-85a2-b0f52801ff98.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Internazionale. Dati e Grafici Sulla Violenza di Genere. Available online: https://www.internazionale.it/bloc-notes/giulia-testa/2019/11/25/dati-grafici-violenza-genere (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- ANSA. Record di Femminicidi nel Mondo nel 2022: Quasi 89.000 Donne Uccise. Available online: https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/mondo/europa/2023/11/25/record-femminicidi-nel-mondo-nel-2022-quasi-89.000-donne-uccise_b3349caf-4aed-40d8-9438-01ae34fe53a0.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Sky TG24. Femminicidi in Italia: Tutti i Dati. Available online: https://tg24.sky.it/stories/cronaca/femminicidi-italia/index.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Elle Italia. Dati Ufficiali sui Femminicidi 2023. Available online: https://www.elle.com/it/magazine/women-in-society/a46517044/dati-femminicidi-2023-ufficiali/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- ONU Italia. Violenza di Genere: Dati 2023. Available online: https://www.onuitalia.com/2023/11/24/donne-14/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Tag24. Femminicidi in Italia: Dati ISTAT 2023. Available online: https://www.tag24.it/946219-femminicidi-dati-istat-2023-120-donne-uccise-meta-dai-partner/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Today.it. Femminicidi: Quanti in Italia nel 2023. Available online: https://www.today.it/attualita/femminicidi-dati-italia-quanti-2023.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Money.it. Quanti Femminicidi in Italia nel 2023: Numeri, Europa e Mondo. Available online: https://www.money.it/quanti-femminicidi-italia-2023-numeri-europa-mondo (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Rossitto, S. La Violenza di Genere Costa all’Europa 366 Miliardi di Euro all’Anno. Il Sole 24 Ore, 7 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio, A. No Pain Device: Empowering Personal Safety with an Artificial Intelligence-Based Nonviolence Embedded System. Electronics 2024, 13, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.A.; Díaz-Ramírez, A.; Miranda-Vega, J.E.; Trujillo, L.; Mejía-Alvarez, P. A Systematic Review of Computer Science Solutions for Addressing Violence Against Women and Children. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 114622–114654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Swapnil, A.L.; Peris, M.D.; Hasan, I.; Khan, R.; Matin, M.A. Multimodal Deep Learning for Violence Detection: VGGish and MobileViT Integration with Knowledge Distillation on Jetson Nano. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 2907–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, M.B.; Oğuz, K. Speech Emotion Recognition: Emotional Models, Databases, Features, Preprocessing Methods, Supporting Modalities, and Classifiers. Speech Commun. 2020, 116, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godase, V.V. Edge AI for Smart Surveillance: Real-Time Human Activity Recognition on Low-Power Devices. Int. J. AI Mach. Learn. Innov. Electron. Commun. Technol. 2025, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athira, K.; Sriharsha, R.; Rajkumar, N. Women’s Safety in Cities Using Android. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), Erode, India, 18–20 October 2023; pp. 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bSafe—Never Walk Alone. Official Website. Available online: https://www.getbsafe.com/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Privacy & Security Policy. Available online: https://www.getbsafe.com/privacy-policy (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Terms of Use. Available online: https://www.getbsafe.com/terms-and-cookies (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Informativa Sulla Privacy. Available online: https://poliba.wixsite.com/no_pain_privacy (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Naved, M.; Fakih, A.H.; Venkatesh, A.N.; Vani, A.; Vijayakumar, P.; Kshirsagar, P.R. Artificial Intelligence Based Women Security and Safety Measure System. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2393, 020072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThingSpeak Cloud Platform. Available online: https://www.thingspeak.com (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- IFTTT Cloud Automation Platform. Available online: https://www.ifttt.com (accessed on 24 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.