Abstract

Graphs are widely used to represent vertices and their relationships, with the subgraph counting problem being a crucial challenge in network analysis. Originating from subgraph matching, this problem aims to efficiently determine the number of subgraphs in a data graph that are isomorphic to a given query graph. Since this task is NP-hard, existing approaches are typically divided into exact and approximate methods. Exact methods compute the precise number of isomorphic subgraphs but incur prohibitive computational costs on large graphs. Approximate methods, often based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), estimate the subgraph count more efficiently but tend to suffer when there is a large size discrepancy between the data graph and the query graph, leading to inaccurate vertex matching. To address these limitations, we propose a domination-based subgraph counting method (DSCM), which improves vertex matching by using a vertex dominance embedding method. This approach, combined with an attention mechanism, accurately computes subgraph counts. Experimental results show that DSCM outperforms existing methods, providing an efficient solution for subgraph counting in large graphs.

1. Introduction

Graphs are a fundamental data structure for modeling entities and the relationships among them, and they are extensively applied in real-world scenarios. Subgraph isomorphism matching focuses on identifying all occurrences in a data graph that are structurally equivalent to a given query graph . This problem is a core task in a wide range of applications, such as information retrieval [1], computer vision [2,3,4], natural language processing [5], chemical informatics [6], and bioinformatics [7,8].

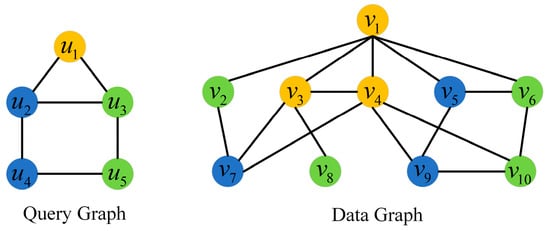

An example of subgraph matching is shown in Figure 1. The color of each node indicates its label. The matching subgraphs of query graph on the data graph are {} and {}.

Figure 1.

Example of subgraph matching.

Existing subgraph counting techniques are generally categorized into exact and approximate methods [9]. Exact approaches aim to compute the precise number of subgraphs that are isomorphic to a given query. These methods can be further classified into enumeration-based techniques [10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and analysis-based techniques [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Enumeration-based algorithms explicitly traverse all candidate subgraph instances in the data graph that match the query structure to derive an exact count. While such approaches ensure full accuracy, they often suffer from prohibitive computational overhead due to the exponential growth of the search space. As a result, enumeration-based methods are typically practical only for graphs of limited size or with relatively simple structures.

Analysis-based exact subgraph matching algorithms determine the number of matches by exploiting theoretical insights and structural properties of both the query graph and the data graph. Rather than explicitly enumerating all candidates, these approaches rely on graph-theoretic analysis to infer the exact count of isomorphic subgraphs. Although they are generally more applicable to large-scale or structurally complex graphs than enumeration-based techniques, they still involve substantial computational overhead to achieve precise results.

Approximate subgraph counting aims to efficiently estimate the number of subgraphs in a data graph that are isomorphic to a given query graph. This approach is especially valuable for large-scale or highly complex graphs, where exact counting becomes computationally prohibitive. By trading a small loss in precision for significant gains in efficiency, approximate methods can deliver near-accurate estimates within acceptable time and resource constraints. Existing approximate counting techniques are commonly classified into five categories: random enumeration [27,28], generalized enumeration [29,30,31,32,33], path-based sampling [34,35], random walk-based methods [36,37,38,39] and color-coding approaches [40]. Despite their efficiency advantages, many of these methods suffer from limited accuracy and poor scalability when applied to large graphs.

With the rapid progress of graph neural networks in recent years, a number of deep learning-based methods have been introduced for approximate subgraph counting [41,42,43,44,45]. Most of these approaches treat subgraph counting as a regression problem, where graph neural networks are used to derive representations of the query graph and the data graph, and the final count is inferred from these embeddings. However, the extracted representations primarily reflect local or intrinsic structural characteristics of individual vertices, while the explicit correspondence between the query and data graphs is insufficiently modeled. To address this limitation, we present a subgraph counting framework that incorporates vertex dominance and substructure dominance, enabling direct modeling of matching relationships between the query and data graphs. By explicitly embedding these relationships into the feature extraction process, the proposed method achieves notably improved counting accuracy.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We propose a dominance-based subgraph counting model, which consists of the vertex dominance embedding network and the subgraph counting prediction network.

- To accurately capture the matching relationships between vertices in the data graph and the query graph, we design a dedicated vertex dominance embedding network capable of precisely modeling these relationships. This network is trained independently to ensure high-quality feature extraction.

- To enhance the accuracy of subgraph count prediction, we generate multiple substructures from the vertices of the query graph. By modeling the matching relationships between these substructures and the data graph, referred to as substructure dominance relationships, our method produces more reliable subgraph count results.

- We conduct extensive experiments across a wide range of real-world datasets, and the results demonstrate that our method significantly outperforms existing state-of-the-art approaches.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we first introduce the fundamental concepts of subgraph matching and subgraph counting, and then we discuss existing subgraph counting methods. Finally, we explain the basic principles of graph neural networks.

2.1. Problem Statement

In this work, we use labeled undirected graphs as a running example to introduce the proposed subgraph counting method. Extending the method to unlabeled or directed graphs only requires minor adjustments to the model inputs.

Definition 1

(Graph). A graph is represented by , where is a set of vertices, is a set of edges between, and L is a label function that associates each vertex with a set of labels.

Definition 2

(Subgraph). A subgraph of G is a graph , where and .

Definition 3

(Subgraph Isomorphism). Given a query graph and a data graph , is subgraph isomorphism to if and only if there is an injective mapping f:

such that:

- , we have where .

- .

Definition 4

(Subgraph Counting). Given a query graph q and a data graph G, the subgraph counting is to calculate the number of subgraph in G that are isomorphic to q, denoted by .

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Subgraph Counting Methods

Existing deep learning-based approaches to subgraph counting typically employ neural models—most notably graph neural networks—to derive representations of the query graph and the data graph, and then estimate the number of isomorphic subgraphs by learning from the similarity between these representations.

NSIC [41] proposes DIAMNet, which incorporates an intermediate caching mechanism based on a recurrent neural network; however, this design does not explicitly encode graph structural information. LSS [42] addresses subgraph counting by decomposing the query graph into a collection of substructures, assigning importance weights to them via self-attention, and aggregating the weighted representations to produce the final estimate. An active learning scheme is further employed to improve generalization. Nevertheless, LSS does not consider the structural properties of the data graph, requiring retraining whenever the underlying data graph is modified.

NeuroSC [43] builds upon LSS by utilizing the GraphQL algorithm to incorporate structural information from the data graph. It identifies candidate vertex sets through structural queries and constructs multiple candidate subgraphs for matching against the query graph. Despite this improvement, the data-graph pruning strategy is not jointly optimized within the neural training process. COUNT-GNN [44] focuses on propagating and aggregating features centered on edges during representation learning, whereas RGIN-GP [45] integrates meta-learning techniques with subgraph counting to enhance prediction accuracy, particularly in scenarios with limited training samples.

In summary, existing deep learning-based subgraph counting methods primarily extract features from the structural properties of individual vertices, and they process the data graph and query graph independently. As a result, they fail to explicitly model the vertex-wise matching relationships between the query graph and the data graph. To address this limitation, we propose a vertex-dominance embedding network that directly captures these matching relationships and thus enables more accurate subgraph counting.

2.3. Graph Neural Network

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) constitute a family of deep learning models tailored for graph-structured data, including social networks, molecular graphs, and transportation systems. In contrast to conventional neural networks, GNNs perform computation directly on graph topologies, enabling effective representation of both vertices and their relational dependencies. Among the various GNN variants, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are among the most commonly adopted architectures.

The GCN model uses the structure of the graph to aggregate the neighbor vertex information, and then updates the vertex representation through a non-linear activation function. Its core operation, the spatial graph convolution layer, is denoted as follows:

where . ( is the number of vertices) is a normalized adjacency matrix, is vertex-level embedding of -th GCN layer (, is vertices feature matrix), is a learnable weights of l-th GCN layer, and f is a non-linear activation function.

3. Method

In this section, we first conduct an overview of our proposed model, then provide a detailed introduction to the details of the model, and finally introduce the training method of this model.

3.1. Model Overview

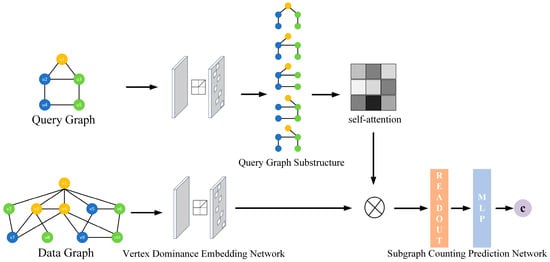

The overall architecture of the proposed DSCM model is shown in Figure 2. DSCM consists of two main components: a vertex dominance embedding network and a subgraph counting prediction network.

Figure 2.

Structure of DSCM model.

The vertex dominance embedding network captures both the structural information of the graph and the matching relationships between vertices, and encodes them into embedding representations for the data graph and the query graph. The subgraph counting prediction network then decomposes the query graph into multiple substructures, enabling a more fine-grained characterization of how the query structure influences the subgraph count, thereby more accurately predicting subgraph counts.

3.2. Vertex Dominance Embedding Network

The purpose of the vertex dominance embedding network is to obtain the embedding representation of each vertex in both the query graph and the data graph, and these embeddings should effectively reflect the matching relationships between the vertices.

To capture this matching relationship, we refer to the idea in [46], where if there is a matching relationship between vertex in the query graph q and vertex in the data graph , the embedding of vertex is dominated by the embedding of vertex . We define this as vertex domination.

Definition 5

(Vector Dominance). Given two vectors and , if A is said to be dominated by B, it must satisfy:

Based on the definition of vector dominance, we provide the definition of vertex dominance.

Definition 6

(Vertex Dominance). Given a data In the two-dimensional G and a query graph q, if a vertex in the data graph G matches with a vertex in the query graph q, the vertices and represent the embeddings of vertices and obtained through the vertex dominance embedding network, the vertex must dominate the vertex .

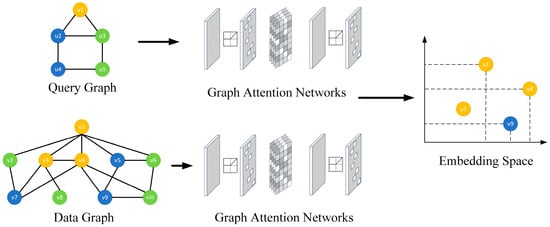

An example of vertex dominance embedding is shown in Figure 3, where the vertex in the query graph matches with vertices and in the data graph . In the two-dimensional embedding space, the embedding of (denoted as ) is located at the bottom-left corner of the embeddings of (denoted as ) and (denoted as ), meaning the embedding of vertex is dominated by the embedding of vertex and . On the contrary, there is no matching relationship between vertex and vertex , so there is no dominant relationship between their embedding and vertex .

Figure 3.

Example of vertex dominance embedding.

The vertex dominance embedding network obtains the features of each vertex in the query graph and data graph through the graph attention network. The representation of the -th layer of vertex is as follows:

where represents the representation of vertex in -th layer. represents the neighboring vertices of vertex , represents the importance weight of vertex to vertex , represents the weight of the -th layer.

We use the max margin loss function to train the vertex dominance embedding network. The loss function is as follows:

where is the embedding of vertex , is the embedding of vertex , and is the -norm.

Using the vertex dominance embedding network, we compute embeddings for individual vertices in both the data graph and the query graph, which together form their respective graph-level representations.

Notably, when applied to large or structurally complex graphs, the proposed model does not require an increase in embedding dimensionality with graph scale. This is because the method captures potential vertex correspondences through dominance relationships, rather than relying on high-dimensional embeddings to encode complete structural information.

3.3. Subgraph Counting Prediction Network

The vertex dominance embedding network produces feature representations for both the data graph and the query graph that implicitly encode vertex-level correspondence information. Building upon these representations, we further investigate the matching relationships between substructures in the query graph and those in the data graph, a concept referred to as substructure dominance.

Definition 7

(Substructure Dominance). If there is a matching relationship between vertices , , in the data graph G and vertices , , in the query graph q, respectively, then the embeddings of the substructure composed of , , in the data graph must dominate the embeddings of the substructure composed of , , in the query graph.

For example, in Figure 3, since the embedding of vertices , , and are dominated by the embedding of vertices , , and , respectively, the embedding of the substructure composed of vertices , , and is necessarily dominated by the embedding of the substructure composed of vertices , , and .

Therefore, we decompose the query graph into substructures, thereby further exploring the matching relationships that exist between the query graph and the data graph.

Within the subgraph counting prediction network, we begin by performing a breadth-first search from each vertex in the query graph to extract its corresponding substructures. A self-attention mechanism is then employed to quantify the contribution of each substructure to the final count estimation. The query graph representation is subsequently obtained by aggregating the substructure embeddings through a weighted summation.

We use the mean square error to train the subgraph counting prediction network. The loss function is as follows:

where represents the number of query graphs. represents the true values of subgraph counts, represents the predicted subgraph counts by the DSCM model.

3.4. Model Training

To further enhance the accuracy of subgraph counting, we adopt a joint training approach for the DSCM model. We first train the vertex dominance embedding network until the model converges. The purpose of this step is to capture the matching relationship features of vertices in the query graph and data graph, providing a foundation for subsequent subgraph counting networks. Afterwards, we fix the parameters of the vertex dominated embedding network and train the subgraph counting prediction network until it converges. The purpose of this step is to accurately predict the number of isomorphic subgraphs by utilizing the embedding information of vertices. Finally, we conduct joint training on the parameters of both the vertex dominance embedding network and the subgraph counting prediction network. At this stage, the parameters of both networks are adjusted simultaneously to further improve the overall model’s performance and accuracy. Joint training ensures the collaborative operation of the two networks, thereby enabling more accurate subgraph counting.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

Environment. The models in this paper are implemented using Python 3.11 language. The computer used for the experiments is configured with an Intel Core i7-12700KF CPU, an NVIDIA RTX4080 graphics card, and 16 GB of RAM.

Datasets. In this paper, we employ four public datasets in the field of subgraph matching. The information of the datasets and the statistics of the query graphs are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. For each dataset, query graphs are generated by randomly sampling connected induced subgraphs of sizes 4, 8, 16, and 24. Multiple queries are extracted for each size to ensure structural diversity. A connectedness constraint is enforced during sampling so that all query graphs represent valid and meaningful local patterns of the original data graph.

Table 1.

Data graph statistics.

Table 2.

Query graph statistics.

Baselines. We compare the algorithm proposed in this paper with the state-of-the-art algorithms NeurSC, LSS, and COUNT-GNN, as well as the algorithm that performs subgraph counting using only GNNs.

Experimental parameters. We used the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The training was conducted for 200 epochs with a batch size of 32. The embedding dimensions of all GNN layers were set within the range of 64–256, and ReLU was used as the activation function for all network components.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

4.2.1. Effectiveness of Subgraph Counting

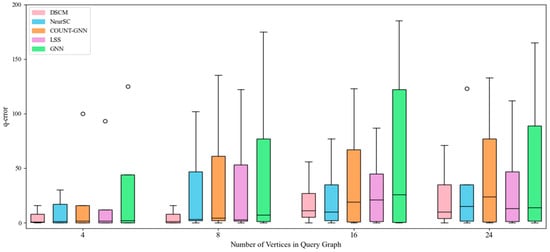

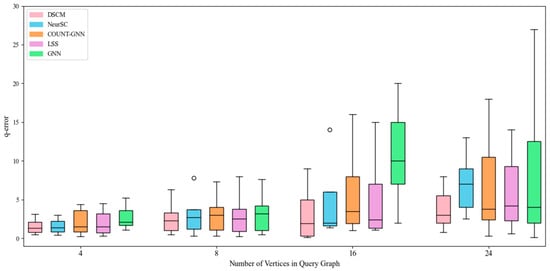

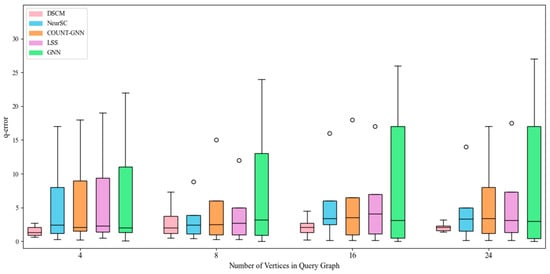

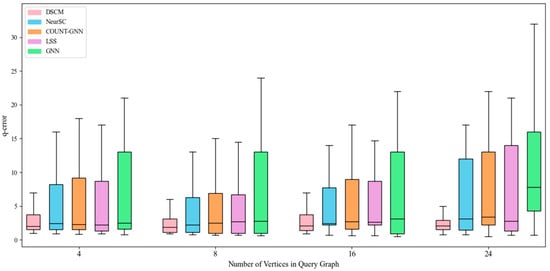

With the increase in the number of query graph vertices, the experimental results of subgraph counting on different datasets are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. In particular, circles denote outliers in figures.

Figure 4.

Counting effect of yeast dataset.

Figure 5.

Counting effect of human dataset.

Figure 6.

Counting effect of hprd dataset.

Figure 7.

Counting effect of dblp dataset.

As shown in Figure 4, on the yeast dataset, the proposed DSCM model consistently maintains good stability as the number of query graph vertices increases, whereas the GCN model exhibits the largest fluctuations and NeurSC shows minor fluctuations. In comparison, COUNT-GNN presents noticeably higher variance with increasing query sizes, while LSS demonstrates moderate fluctuations but still performs less stably than DSCM.

As shown in Figure 5, the DSCM model and the NeurSC model exhibit similar performance. This is because, compared with the yeast dataset, the human dataset has a denser structure, enabling these two complex models to more effectively extract structural information from the data graph. In comparison, COUNT-GNN shows higher error values and larger variance, while LSS achieves moderate but less stable performance, both of which indicate weaker structural modeling capability on the human dataset.

As shown in Figure 6, on the hprd dataset, the DSCM model consistently maintains good stability and low error values. In contrast, the NeurSC model performs poorly when the query graph contains four vertices but achieves performance comparable to DSCM on larger query graphs. Meanwhile, COUNT-GNN exhibits noticeably larger fluctuations, and LSS performs more stably but remains less accurate, suggesting limited generalization ability for both models on this challenging dataset.

As shown in Figure 7, the above conclusion is further confirmed. However, since the dblp dataset is relatively large, when the query graph contains 24 vertices, the error of the NeurSC model increases significantly compared with that on the 16-vertex query graph. On the dblp dataset, the DSCM model maintains its error within a small fluctuation range as the query graph size increases. In contrast, due to the large scale of the hprd and dblp datasets, the performance of the GCN model is far inferior to that of the NeurSC and DSCM models. Meanwhile, COUNT-GNN exhibits consistently higher error values across all query sizes, and LSS shows moderate but unstable performance, both of which indicate limited robustness on large-scale datasets such as dblp.

4.2.2. Ablation Experiments

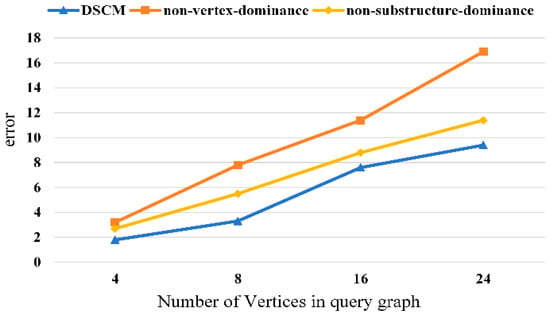

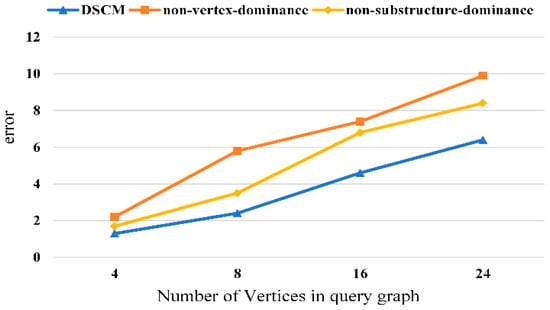

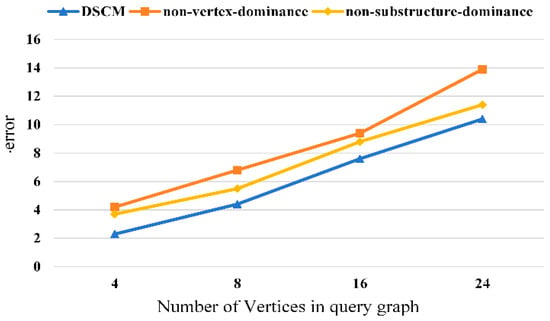

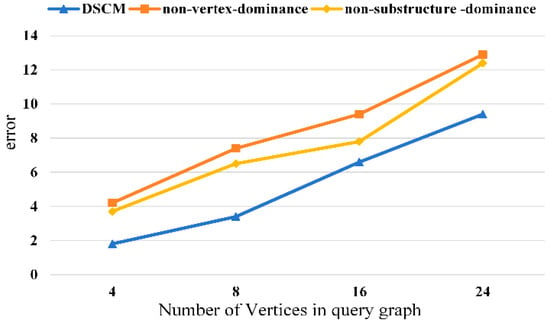

We conduct ablation studies to verify the effectiveness of each component of the proposed method. The experimental results are shown in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. It can be observed that removing the vertex-dominant embedding and the structure-dominant embedding leads to a significant increase in the subgraph counting mean error, with the impact of the vertex-dominant embedding being more pronounced.

Figure 8.

Ablation experiment of yeast dataset.

Figure 9.

Ablation experiment of human dataset.

Figure 10.

Ablation experiment of hprd dataset.

Figure 11.

Ablation experiment of human dataset.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we study an NP-complete problem, subgraph isomorphism counting, by DL techniques. To more accurately extract the feature representations of the data graph and the query graph, we proposed a domination-based subgraph counting model, referred to as DSCM. In the process of computing embeddings for vertices in data and query graphs, we introduced the concept of vertex dominance to precisely calculate the matching relationships between vertices. Subsequently, in computing subgraph counts, we combined subgraph dominance and attention mechanisms to accurately determine the number of subgraphs. Finally, we compared DSCM model with the most advanced subgraph counting methods on multiple real datasets from various aspects. Extensive experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of our method.

Author Contributions

H.Y. made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and to the development and implementation of the proposed methodology. J.L. (Ji Li) was responsible for the design and implementation of the model and the comparative experimental evaluation. J.L. (Jiaquan Li) contributed to figure design and the drafting of the manuscript. C.L. provided overall supervision of the research, offered critical revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be made publicly available after the completion of the ongoing follow-up research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hong, L.; Zou, L.; Lian, X.; Philip, S.Y. Subgraph matching with set similarity in a large graph database. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 27, 2507–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llados, J.; Marti, E.; Villanueva, J.J. Symbol recognition by error-tolerant subgraph matching between region adjacency graphs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2001, 23, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, D.; Foggia, P.; Sansone, C.; Vento, M. Thirty years of graph matching in pattern recognition. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2004, 18, 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento, M.; Foggia, P. Graph matching techniques for computer vision. In Image Processing: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 381–421. [Google Scholar]

- Nastase, V.; Mihalcea, R.; Radev, D.R. A survey of graphs in natural language processing. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2015, 21, 665–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, C.W.; Rogers, L.; Green, W.H.; Jensen, K.F. Computer-assisted retrosynthesis based on molecular similarity. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Yang, J. GADDI: Distance index based subgraph matching in biological networks. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Extending Database Technology, Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 24–26 March 2009; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Carletti, V.; Foggia, P.; Vento, M. Performance comparison of five exact graph matching algorithms on biological databases. In International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, P.; Paredes, P.; Silva, M.E.P.; Aparicio, D.; Silva, F. A survey on subgraph counting: Concepts, algorithms, and applications to network motifs and graphlets. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernicke, S. A faster algorithm for detecting network motifs. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics (WABI’05), Mallorca, Spain, 3–6 October 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Wernicke, S.; Rasche, F. FANMOD: A tool for fast network motif detection. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1152–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhack, R.; Mogilevski, Y.; Louzoun, Y. An optimal algorithm for counting network motifs. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2007, 381, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochow, J.A.; Kellis, M. Network motif discovery using subgraph enumeration and symmetry-breaking. In Research in Computational Molecular Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kashani, Z.R.M.; Ahrabian, H.; Elahi, E.; Nowzari-Dalini, A.; Ansari, E.S.; Asadi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Schreiber, F.; Masoudi-Nejad, A. Kavosh: A new algorithm for finding network motifs. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeyer, S.; Michoel, T.; Fostier, J.; Audenaert, P.; Pickavet, M.; Demeester, P. The index-based subgraph matching algorithm (ISMA): Fast subgraph enumeration in large networks. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houbraken, M.; Demeyer, S.; Michoel, T.; Audenaert, P.; Colle, D.; Pickavet, M. ISMAGS: Exploiting symmetry for faster subgraph enumeration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D.; Shavitt, Y. Efficient counting of network motifs. In Proceedings of the IEEE 30th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops, Genoa, Italy, 21–25 June 2010; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, D.; Shavitt, Y. Rage: A rapid graphlet enumerator for large networks. Comput. Netw. 2012, 56, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, T.; Demšar, J. A combinatorial approach to graphlet counting. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, T.; Demšar, J. Combinatorial algorithm for counting small induced graphs and orbits. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira, L.A.A.; Maximo, V.R.; Fazenda, A.L.; Conceicao, A.F. Accelerated motif detection using combinatorial techniques. In Proceedings of the 2012 Eighth International Conference on Signal Image Technology and Internet Based Systems, Sorrento, Italy, 25–29 November 2012; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 744–753. [Google Scholar]

- Meira, L.A.A.; Máximo, V.R.; Fazenda, A.L.; Da Conceição, A.F. Acc-Motif: Accelerated network motif detection. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2014, 11, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, M.; Brandes, U. Quad census computation: Simple, efficient, and orbit-aware. In Advances in Network Science. NetSci-X 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann, M.; Brandes, U. Efficient orbit-aware triad and quad census in directed and undirected graphs. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2017, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melckenbeeck, I.; Audenaert, P.; Colle, D.; Pickavet, M. Efficiently counting all orbits of graphlets using autogenerated equations. Bioinformatics 2017, 34, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melckenbeeck, I.; Audenaert, P.; Van Parys, T.; Van De Peer, Y.; Colle, D.; Pickavet, M. Optimising orbit counting by equation selection. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, P.; Silva, F. Efficient subgraph frequency estimation with g-tries. In Proceedings of the WABI 2010, Liverpool, UK, 6–8 September 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 238–249. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, P.; Ribeiro, P. Rand-FaSE: Fast approximate subgraph census. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2015, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pržulj, N.; Corneil, D.G.; Jurisica, I. Efficient estimation of graphlet frequency distributions. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Hasan, M.A. Graft: An efficient graphlet counting method. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2014, 26, 2466–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, F.-X.; Pan, Y. Symmetry compression method. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2012, 9, 1776–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elenberg, E.R.; Shanmugam, K.; Borokhovich, M.; Dimakis, A.G. Beyond triangles: Distributed estimation of 3-profiles. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, Australia, 10–13 August 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Elenberg, E.R.; Shanmugam, K.; Borokhovich, M.; Dimakis, A.G. Distributed estimation of graph 4-profiles. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–15 April 2016; International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, M.; Seshadhri, C.; Pinar, A. Path sampling: Fast estimation of 4-vertex subgraphs. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web, Florence, Italy, 18–22 May 2015; pp. 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Seshadhri, C.; Pinar, A.; Kolda, T.G. Triadic measures on graphs: Wedge sampling. In Proceedings of the 2013 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Austin, TX, USA, 2–4 May 2013; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahman, M.; Hasan, M.A. Guise: Uniform sampling of graphlets. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Data Mining, Brussels, Belgium, 10–13 December 2012; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Lui, J.; Ribeiro, B.; Towsley, D.; Zhao, J.; Guan, X. Efficiently estimating motif statistics of large networks. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2014, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.K.; Hasan, M.A. Finding network motifs using MCMC sampling. In CompleNet; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Lyu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, Y. SSRW: Random-walk-based graphlet estimation. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Gold Coast, Australia, 21–24 May 2018; pp. 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, M.; Chierichetti, F.; Kumar, R.; Leucci, S.; Panconesi, A. Motif counting beyond five nodes. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2018, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pan, H.; He, M.; Song, Y.; Jiang, X.; Shang, L. Neural Subgraph Isomorphism Counting. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1959–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Yu, J.X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Rong, Y. A Learned Sketch for Subgraph Counting. In Proceedings of the 48th ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Boston, MA, USA, 20–25 June 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2142–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J. Neural Subgraph Counting with Wasserstein Estimator. In Proceedings of the 49th ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 12–17 June 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X. Count-GNN: Graph Neural Networks for Subgraph Isomorphism Counting. In Proceedings of the 37th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA, 7–14 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; He, Z.; Yu, J.X.; Rong, Y. Learning with small data: Subgraph counting queries. Data Sci. Eng. 2023, 8, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; You, J.; Wen, C.; Canedo, A.; Jure Leskovec, J. Neural subgraph matching. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.03092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.