Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are widely utilized for environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, infrastructure inspection, and various defense missions, including reconnaissance and surveillance. Their cybersecurity is essential because any compromise of communication, navigation, or control systems can cause mission failure and introduce significant safety and security risks. Therefore, this paper examines the existing literature on UAV cybersecurity and highlights that most previous surveys focus on listing different types of attacks or communication weaknesses, rather than evaluating the problem from a control systems perspective. Considering control systems is important because the safety and performance of a UAV depend on how cyberattacks affect its sensing, decision-making, and actuation loops; modeling these attacks and their impact on system behavior provides a clearer foundation for designing secure, resilient, and stable control strategies. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, it presents a mathematical framework for characterizing common cyberattacks on UAV communication and sensing layers, including time-delay switch, false data injection, denial of service, and replay attacks. To demonstrate the impacts of these attacks on UAV control systems, a simulation of a two-UAV leader-follower multi-agent system is conducted in MATLAB. Defense algorithms from the existing literature are then organized into a hierarchical framework of prevention, detection, and mitigation, with detection and mitigation further categorized into model-based, learning-based, and hybrid approaches that combine both. The paper concludes by summarizing key findings and highlighting challenges with current defense strategies, including those insufficiently addressed in existing research.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have seen a surge in popularity because of their versatility and many advantages over traditional aircraft. Such advantages include low maintenance cost and reduction in the size and load requirements of the aircraft. In safety critical applications such as warfare, firefighting, and power line inspection, a UAV is favorable because it eliminates the risk of harm to the operator [1,2,3,4,5]. Other well-known applications in which UAVs excel include agriculture, delivery services, and photography [6,7]. UAVs have also been shown to be useful in providing temporary wireless communication networks through Flying Ad Hoc Networks (FANETs) to rescue operations and victims of natural disasters after their existing network infrastructure has been destroyed [8].

UAV control is classified into two main categories: centralized and decentralized. In centralized control, a UAV’s flight control and motion planning is computed remotely, whether autonomously or through a human operator. In decentralized control, the UAV is more independent in that it is able to interpret its environment and make motion planning decisions with its own computational resources or by cooperating with other nearby UAVs [9,10]. The disadvantage of centralized control is that strong, uninterrupted wireless communication between the Ground Control Station (GCS) and UAV is far more significant than in a decentralized control scheme. Typical wireless communication protocols for UAVs include Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, ZigBee, and LTE, which are vulnerable to attacks without proper countermeasures [11,12]. On the other hand, common sensing equipment aboard a UAV includes inertial measurement units (IMU), GPS, LiDAR, and optical and thermal cameras [13]. These instruments are integral to the UAV’s control system and, therefore, are potential cyberattack targets.

From a control system perspective, a cyberattack on a UAV has two potential targets: the communication network layer and the sensing layer. In a centralized UAV control scheme, both elements are crucial, while in decentralized control, the role of communication between the GCS and UAV is less significant. However, in both control schemes, the sensing of its environment is necessary for the control system to operate safely. Common threats that would compromise a UAV’s control system include Time Delay Switch, False Data Injection, Denial of Service, and Replay attacks. A TDS attack occurs when an attacker injects time-varying delays into transmitted data or feedback loops, possibly compromising stability [14,15,16]. A FDI attack occurs when an attacker feeds faulty data to a UAV’s communication and sensing layers to cause instability in the control system [17,18]. A DoS attack is when a hacker overwhelms the UAV’s communication channels or sensing layer with fraudulent traffic to exhaust its computational resources, and therefore, disrupts communication and/or the control system [19]. A Replay attack is when an attacker intercepts communication between a UAV and GCS and replays it at some later time to negatively influence UAV control [20]. The attacks mentioned above are significant threats to UAV control; therefore, robust defense strategies are required.

The hierarchical structure of UAV cyberattack defense algorithms consists of prevention, detection, and mitigation. Prevention algorithms aim to secure wireless communication and sensing layers through sophisticated encryption and authentication methods [21,22]. An exceptionally effective communication security countermeasure applicable to groups of UAVs such as FANETs is Blockchain, which is highly dependent on encryption strategies [23]. The issue with these defense methods is that they are not always robust and are almost always limited by the power and computational resources available on board the aircraft [22,24,25]. The goal of a detection algorithm is to recognize suspicious wireless communication activity or sensor data and then deploy mitigation techniques and/or alert the GCS that an attack may be present. Detection algorithms are commonly based on the implementation of complex algorithms, statistical analysis, and artificial intelligence to detect suspicious wireless communication activity [26,27,28,29,30]. Mitigation algorithms consist of designing resilient UAV controllers to attenuate undesirable control system behavior during an attack [1,31]. Researchers have effectively used model-based algorithms such as state observers or estimators and learning-based algorithms such as neural networks (NN) and machine learning (ML) to develop resilient controllers [32,33]. Further research in this field is motivated by the need to overcome computational resource limitations and develop robust, secure networks and control systems for UAVs.

Existing survey papers on UAV cybersecurity primarily focus on detailing attacks and their defense mechanisms from a communications perspective, rather than from a control-theoretic perspective. These works often overlook the direct threats that cyberattacks pose to the controller itself, as well as how robust control algorithms can mitigate such threats. The algorithms investigated are primarily categorized as prevention and detection methods, while mitigation strategies are largely neglected. For example, in [6], UAV cybersecurity was discussed from a communication network perspective, only mentioning prevention and detection techniques such as cryptography and intrusion detection schemes, while neglecting mitigation. In [23], the survey focused on securing wireless UAV communication through machine learning and encryption techniques such as blockchain and watermarking. In [34], UAV cybersecurity was surveyed by classifying threats and their respective defenses into software, machine learning, and network categories. In [24], attacks and defenses were organized similar to [34], but included payload attacks as a fourth category. In [22], attacks were categorized from the perspective of UAV system architecture, placing them into eight categories: spoofing, replay, jamming, DoS, eavesdropping, side channel, manipulation, and system intrusion. The weaknesses of existing countermeasures and new security threats were also discussed. In [30], cyberattack defenses were classified into three categories: prevention, detection, and resilience based on reputation and trust. Resiliency was defined as the system’s capacity to supply services consistently during an attack, bug, or system failure. The discussion of resiliency strategies was limited to network security attacks and neglected control algorithms. In [35], a survey was conducted on the physical layer security of UAVs in which prevention and detection methods were detailed extensively. Mathematical modeling of secrecy performance metric was included but FDI, TDS, DoS, and replay attacks were not mentioned explicitly.

This survey follows a structured but narrative-driven literature review methodology inspired by established systematic review practices (e.g., PRISMA), with the goal of achieving broad coverage rather than exhaustive enumeration. Relevant studies were identified primarily through iterative searches on Google Scholar using combinations of keywords related to UAVs, cybersecurity, networked control systems, and specific attack and defense mechanisms (e.g., false data injection, denial-of-service, replay attacks, resilient control, and secure estimation). Additional papers were identified through backward and forward citation tracking of key survey and foundational works, as well as targeted searches to fill gaps in specific prevention, detection, and mitigation categories. Studies were included based on relevance to UAV or closely related cyber-physical systems and their explicit connection to control, communication, or sensing security, while purely theoretical works without system-level implications were generally excluded.

Beyond categorizing existing prevention, detection, and mitigation techniques, the control-theoretic framing adopted in this paper provides several new insights that are largely absent from prior UAV cybersecurity surveys. First, by modeling cyberattacks as structured perturbations to signals, dynamics, and communication channels, diverse attacks such as TDS, FDI, DoS, and replay can be analyzed within a unified mathematical framework, enabling direct comparison of their effects on stability, tracking performance, and robustness margins. Second, this perspective highlights fundamental trade-offs between security mechanisms and closed-loop control performance, revealing how delays, packet losses, and corrupted measurements propagate through feedback loops rather than remaining confined to the communication layer. Finally, the control-oriented analysis exposes open problems that are obscured in communication-centric surveys, including the co-design of lightweight security mechanisms with control laws, resilience guarantees for multi-agent coordination under attack, and stability-preserving integration of learning-based defenses in safety-critical UAV systems.

In summary, existing surveys on UAV cybersecurity largely emphasize communication-centered attack classifications and corresponding prevention or detection techniques, while giving limited attention to how cyberattacks directly disrupt guidance, estimation, and control loops. The proposed paper contributes by addressing this gap through a control-theoretic perspective that explicitly analyzes how attacks influence system dynamics and how resilient control algorithms can mitigate their effects. Unlike prior work, which rarely examines mitigation beyond communication safeguards, this paper systematically integrates attack modeling, control-level vulnerabilities, and control-oriented defense strategies to provide a more comprehensive foundation for secure and resilient UAV operation.

The outline of this paper is as follows. Section 2 introduces a generalized attack model based on the existing literature to build a framework for describing cyberattacks on UAVs. Section 3 examines the effects of attacks through a review of existing literature and a simulation of a leader-follower multi-agent UAV network conducted in MATLAB. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 investigate the existing literature on prevention, detection, and mitigation algorithms, respectively. Please note that some referenced papers are not specifically targeted towards UAVs, but their methods are generally applicable to any networked control system (NCS). Finally, Section 7 summarizes our findings, and Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Generalized Attack Model

A general mathematical formulation of cyberattacks offers a clearer understanding of their impact on UAV control systems. Such frameworks are commonly used in studies that propose model-based detection and mitigation algorithms. The generalized attack model adopted in this section is built upon well-established NCS formulations used to study cyber-physical attacks in industrial and cyber-physical systems. The framework presented in this paper is primarily based on [1,15,18,31,36,37,38], in which the dynamics of a UAV under cyberattack are described as follows. A general model representing the dynamics of UAV agent i is modeled as

where is the state vector with n state variables, is the control input with p inputs, and is the output with q outputs, and may describe linear or nonlinear dynamics while models the output. The control input is modeled by

where denotes the agent’s controller behavior and is the reference signal. In the absence of cyberattack, represents the plant output signal perceived by the controller after wireless communication delays and noise, which is defined as

where models the communication channels. Under cyberattack, the model parameters become

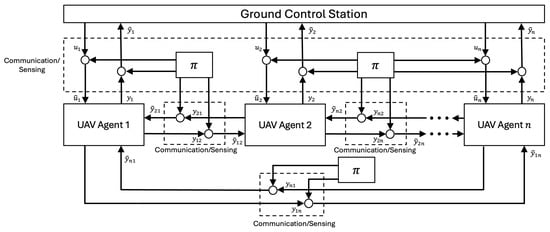

where a tilde denotes a parameter corrupted by a cyberattack, the effects of which are modeled by the attack function . This is illustrated more clearly in Figure 1, which shows a general communication architecture for a multi-agent system (MAS) of UAVs under cyberattack. In the following sections, a signal such as , , or will be represented by general signal, , where the corrupted signal is denoted by . The nature of the attack function depends on the type of attack. The following subsections define time-delay switch, denial of service, false data injection, and replay attacks within the aforementioned mathematical framework.

Figure 1.

A General Communication Architecture for a Multi-Agent System of UAVs.

2.1. Time-Delay Switch Attack

A UAV control system relies on accurate and timely sensor and reference data to generate appropriate control inputs. While wireless communication channels or sensors can naturally introduce some delay in the control loop, a cyberattacker can intentionally cause unsafe delays through a Time-Delay Switch (TDS) attack by manipulating or delaying data packets. Such delays may degrade control performance, reduce efficiency, or even cause system instability [14,37,39]. The generic control system signal corrupted by a TDS attack is modeled as

where denotes an unknown, random, and time-varying delay introduced by a TDS attacker. Physically, this model states that the control loop’s perceived states lag behind the true, uncorrupted signal by a delay, . If TDS attack can also be injected to control or reference signals causing instability and unsafe behavior for UAVs. More information on TDS attacks can be found in the following references [15,16,37,38,40].

2.2. Denial of Service Attack

A Denial of Service (DoS) attack occurs when an adversary completely overwhelms a UAV’s communication or sensing layers with illegitimate traffic, thereby obstructing the transmission of valid data. This scenario can be regarded as the limiting case of a TDS attack, in which the time delay , preventing the control system from receiving timely updates. It is important to note that the complete denial of new information packets does not happen instantaneously; rather, increases gradually until is held constant via a zero-order hold. Mathematically, the attack function for a DoS attack can be represented as follows

where

Here, is the communication availability indicator, with indicating that communication is available but delayed, and indicating that a DoS attack has caused complete communication loss at time . This implies that, during a DoS attack, the control loop receives no new information about the system states, potentially leading to instability.

2.3. False Data Injection Attack

The goal of a False Data Injection (FDI) attack is to mislead the UAV’s feedback control system by substituting its current measured states with false data. A more sophisticated FDI attacker may leverage knowledge of the UAV’s control system to perform a more effective attack [31]. A FDI attack can be represented by

where represents a bounded, unknown, continuous time-varying FDI attack. In most FDI attacks, access to communication channels is required. One type of FDI attack where this is not applicable is a GPS spoofing attack. Since civilian GPS signals are not encrypted, an adversary can easily transmit a GPS signal stronger than the true signal to mislead the UAV [41].

2.4. Replay Attack

A replay attack on a UAV control system occurs when an adversary records a legitimate signal, , during normal operation and later replays this previously recorded signal to the system, with the goal of degrading performance or inducing instability [20]. The received signal under a replay attack is modeled as

where is a binary indicator of attack presence, defined as

When , the signal corresponds to a previously recorded measurement, and denotes the replay delay between the time the signal was recorded and the time it is re-injected into the system.

3. Effects of Attacks

3.1. Existing Literature

Numerous studies proposing novel prevention, detection, and mitigation algorithms present simulations in which their proposed algorithms are subjected to cyberattacks. These studies frequently include comparisons with existing algorithms also designed to defend against such threats. However, they often omit baseline simulations that illustrate the effects of cyberattacks on control systems without countermeasures. The studies highlighted below address this gap by demonstrating the impact of cyberattacks on basic control systems. In [15], the effects of a TDS attack on a two-UAV leader-follower formation were investigated. The RMSE tracking errors of a traditional dynamic inversion controller were 1.81, 0.18, and 4.24 for the pitch, yaw, and roll rates, respectively. For the novel controller proposed in the paper, the RMSE values were decreased to 1.78, and 0.16, 3.86 respectively. In [42], a FDI attack was simulated on five UAVs operating under a formation control scheme. The simulation showed that injecting false data into the sensing layers of the UAV multi-agent network led to inaccurate control execution, resulting in significant increases in the position and velocity state residuals of the UAVs under attack. Similarly, in [43], a simulation performed on a formation of five UAVs showed that FDI attacks negatively influence the overall state of health of the formation as attack time increases. In [44], a replay attack was simulated on a Linear Quadratic Gaussian (LQG) controller where the attack caused a 91% performance degrade with respect to the optimal LQG cost. In [45], it was shown that a DoS attack on a formation of six UAVs can degrade stability and negatively influence trajectory. Recent work in autonomous driving has demonstrated highly stealthy physical attacks on vision systems—for example, Omni-Angle Assault demonstrates robust multi-angle physical illumination attacks on face recognition, and FIGhost and ITPatch demonstrate fluorescent-ink triggered backdoor/patch attacks against traffic-sign recognition—underscoring that physical-world sensing attacks are a realistic threat to UAV perception as well [46,47,48].

3.2. Attack Simulations

The following simulation is intended as a simple illustrative example to motivate the control-theoretic impact of cyberattacks on UAVs. Consider a multi-agent network of UAVs composed of one leader and one follower node, which communicate through a time-invariant, connected, directed graph. The x-direction dynamics for the leader node of this system are described by

where is the velocity commanded for node 1 to follow and is a design parameter. Similarly, the x-direction dynamics for the follower node are designed as

where is the desired distance that node 2 must maintain between itself and node 1 and and are design parameters. The dynamics for the y- and z-directions are analogous. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will only consider the x-direction dynamics.

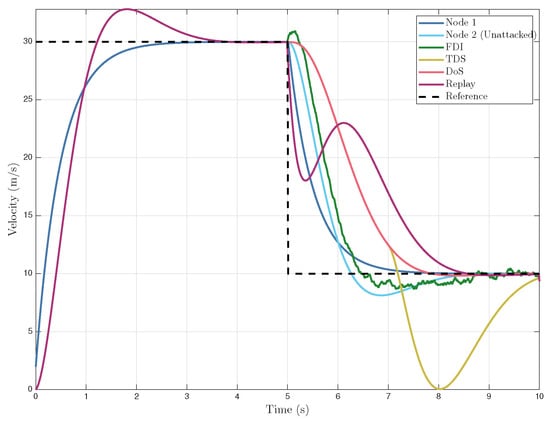

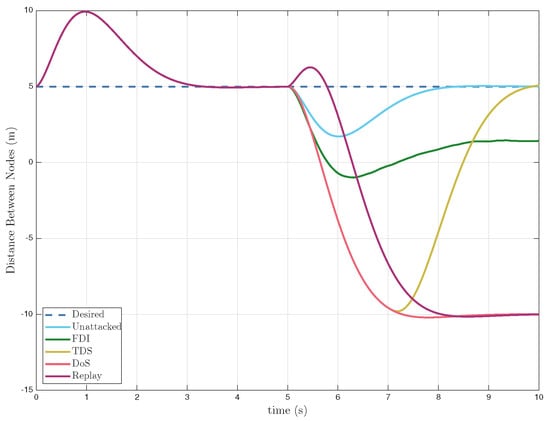

In the following simulation, each attack occured at s and lasted until the end of the simulation at s. Initial conditions were arbitrarily chosen as , , , . The design parameters , , and were chosen as 2, 4, and 3, respectively. In each attack, only the output sent by node 1 to the node 2 becomes corrupted (i.e., ).

The TDS attack was simulated by sending the last known value for s and then allowing the signal to resume with a time delay. Similarly, for the DoS attack, when the attack begins, is held constant for the duration of the attack. A FDI attack was simulated by superimposing a random time-varying signal, onto . The signal was randomly generated such that it exhibited a normal distribution with a non-zero median value because if a FDI signal has a median value of zero, it is essentially Gaussian noise and would have far less of an impact on UAV trajectory. A Replay attack was simulated by capturing the time history of from to s and replaying that data once the attack began. The simulation results are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, which illustrate that each cyberattack led to a loss of coordination between the nodes, causing collisions and preventing node 2 from maintaining its desired velocity and spacing. Table 1 summarizes the corresponding increase in root-mean-square error (RMSE) for each attacked case relative to the unattacked baseline. From a control-theoretic perspective, these results illustrate that different attack classes induce qualitatively distinct closed-loop behaviors, with delay-based attacks primarily degrading stability margins, while FDI and replay attacks bias state estimates and corrupt feedback signals. Such distinctions are critical for designing targeted detection and mitigation strategies, as robustness to one class of attack does not necessarily imply resilience to others.

Figure 2.

Unattacked and Attacked Leader and Follower Velocity vs. Time.

Figure 3.

Unattacked and Attacked Distance Between Leader and Follower vs. Time.

Table 1.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for each Response.

4. Prevention Algorithms

The goal of a prevention algorithm is to prevent an adversary from gaining access to the communication and sensing layers of a UAV. The prevention algorithms discussed in this paper include encryption, blockchain, authentication, channel hopping/allocation, and redundancy. It should be noted that, although prevention algorithms are effective in enhancing the security of communication and sensing layers, some of these algorithms may introduce delays or noise that can impair the stability of the control loop.

4.1. Encryption

Encryption is the process of scrambling data using a complex cipher prior to transmission [49]. At the receiver node, a key is required to decrypt the information. The two primary types of encryption methods are symmetric and asymmetric [50]. Symmetric encryption uses a private key shared between two nodes in a network to encrypt and decrypt data. In [51,52,53], symmetric encryption schemes are successful in securing UAV communication. Alternatively, asymmetric encryption uses a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption, which is generally more secure but less efficient.

The most significant challenge with cryptographic techniques is that they are computationally intensive, introduce communication latencies, and can be limited by the computational resources aboard the UAV [24]. This may not be a significant constraint for a NCS such as a chemical processing plant. For example, in [54], a Paillier cryptographic scheme is used to secure Lyapunov-based model predictive control of a chemical process, where the sampling rate is low enough to absorb the latencies introduced by encryption and decryption. However, UAVs require low-latency wireless communication, which has motivated recent research in developing lightweight encryption techniques. For example, in [52,53], lightweight and energy-efficient private key encryption algorithms for UAVs are presented. Similarly, in [55], communication latencies introduced by encryption algorithms are compensated for by modeling delays in the control design of a general NCS. In [56], Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) is shown to be a strong secure communication encryption strategy in a NCS in which the latencies introduced into the system are handled by a Kalman filter. Although QKD is currently mostly experimental, it shows promise for securing NCS communication in the near future. For more papers on lightweight encryption algorithms for UAVs, see [57,58,59]. Similar computational constraints have been extensively studied in related domains such as Internet of Things (IoT), mobile devices, and edge computing, where secure communication must be achieved under strict energy, latency, and processing limitations [60]. These fields have motivated the development of lightweight cryptographic primitives, hardware-assisted security, and computation offloading strategies, which are directly applicable to resource-constrained UAV platforms. Adapting such secure and efficient computing techniques to UAV networks strengthens the case for lightweight encryption schemes that preserve control performance while maintaining security guarantees.

4.2. Blockchain

One of the most effective prevention algorithms available is blockchain. Blockchain is a decentralized digital ledger system that records and stores information in an expanding list of records linked together by cryptography [23,61]. In a blockchain, each record contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block, a timestamp, and the transmitted data. Each node possesses a copy of the history of records, and adding new information requires the consensus of all nodes. If an adversary wanted to alter the information in the blockchain, 51% of the nodes within the blockchain would have to modify their records for the blockchain to reach consensus. Blockchain offers strong security for UAV control by using a decentralized, immutable, and tamper-resistant ledger, eliminating the vulnerability of a single point of failure inherent in centralized systems. Consequently, it has been useful in securing multi-agent systems such as UAV swarms performing disaster recovery in [62]. For example, in [63], the communication channels of a UAV swarm tasked with crowd monitoring are successfully secured using blockchain. Similarly, in [64], the authors propose blockchain as a reliable and secure communication system capable of controlling UAVs operating in both a formation and a leader-follower control scheme. However, a significant limitation of blockchain is its high computational overhead, which introduces latency into communication channels [25]. Notably, the computational efficiency of these blockchain-based communication schemes depends on factors such as network size and complexity, interaction frequency between nodes, and the volume of transmitted data. Similar challenges have been identified in blockchain-enabled IoT and edge computing systems, where limited computation and strict latency requirements have driven research toward lightweight consensus mechanisms, hierarchical blockchains, and edge-assisted validation [65]. These approaches reduce on-board computational burden by delegating intensive processing to edge nodes or selectively limiting participation in consensus, while preserving security properties. Incorporating such secure and efficient computing concepts into UAV blockchain architectures further supports the feasibility of blockchain-based prevention methods in resource-constrained aerial networks. Despite these limitations, blockchain remains attractive for multi-agent UAV systems due to its ability to provide distributed trust, secure coordination, and resilient consensus without relying on centralized control. In UAV swarms, blockchain can enhance cooperation by ensuring the integrity of task assignments, shared state information, and inter-agent communication, which is critical in military applications. However, practical deployment in real-time UAV applications often requires lightweight consensus mechanisms or hybrid architectures to balance security with latency and resource constraints.

4.3. Authentication

Authentication is the verification of the identity of a device or user with a password before allowing access to a wireless network [66]. Authentication ensures that only trusted entities communicate with UAVs or the GCS, which helps prevent adversaries from impersonating legitimate nodes. While authentication can prevent an adversary from injecting false data or replaying data, it is ineffective against DoS, TDS, and GPS spoofing attacks.

4.4. Channel Hopping

Channel hopping is another prevention algorithm in which wireless communication frequently switches between different frequency channels [67]. A channel hopping scheme is robust unless the attacker understands the pattern of frequency hopping. In [68], an effective channel hopping scheme is devised where frequency selection is governed by chaotic mapping. Chaotic mapping refers to a deterministic mathematical process that generates complex, pseudo-random sequences highly sensitive to initial conditions. This sensitivity ensures unpredictability in the frequency hopping pattern, making it difficult for adversaries to predict or jam the communication channels. In [69], a prevention algorithm is introduced that combines encryption and channel hopping techniques to address the issue of computational resource restrictions in UAVs. An algorithm was designed in which the UAV and GCS communicate through a primary unencrypted channel, but, in the event of a cyberattack, communication switches to a secondary, redundant encrypted channel.

4.5. Adaptive Channel Allocation

Another method similar to channel hopping is adaptive channel allocation (ACA). Unlike channel hopping, which continuously switches channels based on a chaotic algorithm, ACA responds to real-time factors such as resource constraints or a cyberattack [70]. For example, in [71], wireless resources for a generalized NCS are allocated based on a deep reinforcement learning algorithm.

4.6. Redundancy

Redundancy is a prevention technique in which redundant sensors or communication channels are integrated into the UAV-GCS communication and sensing architecture [72]. For example, in [73], a UAV platform is designed with three redundant sensors and four redundant communication channels that are used in the event of a DoS attack. In [74], redundant sensors are simulated in a NCS under FDI attack. While redundant sensors may be feasible for most NCSs, a UAV may not be able to accept additional sensors due to weight constraints.

5. Detection Algorithms

The purpose of a detection algorithm is to identify suspicious communication and sensing through analysis of signals perceived by the UAV. The detection algorithms discussed in this section are organized into model-based, learning-based, and hybrid approaches that combine both model-based and learning-based elements. For a comprehensive list of the cyberattack detection-focused papers discussed in the following section, please refer to Table 2.

Table 2.

UAV Cyberattack Detection Algorithms.

5.1. Model-Based Detection

A model-based detection algorithm relies on the mathematical model that describes the kinematics of the UAV to detect suspicious sensing or communication data. Examples of this method include state observers and filtering. A state observer is a mathematical algorithm that uses past inputs and output measurements to estimate the present states of a dynamic system that may not be directly measurable [89]. Since an observer predicts how a system’s states should behave, it can detect cyberattacks by comparing the estimated states against the sensors’ measured states. Examples of state observers include Unknown Input Observers (UIO), Kalman filters, sliding-mode observers, and Luenberger observers. These methods are limited in that attacks that fall outside the predefined residual threshold may go undetected, and selecting an optimal threshold value can be challenging. In this section, model-based detection algorithms are organized by the cyberattacks they are designed to identify.

5.1.1. TDS Attacks

Since the mathematical model that describes the dynamics of the UAV is known, its expected behavior can be predicted and used to identify time delays in the system. For example, in [15], a state observer is used to detect TDS attacks in NCSs by comparing the estimated states with the actual measurements. Another paper incorporating state estimation techniques to detect TDS attacks is [39], in which TDS attacks in a power grid are detected by comparing estimated delays against a threshold. Similarly, in [76], an adaptive observer is used to estimate the states of a NCS and detect TDS attacks based on these measurements. In addition to state estimation algorithms, other model-based algorithms, such as reference governors, are also effective. A reference governor is a model-based algorithm designed to filter or adjust a control system’s reference signal to ensure that system constraints such as actuator limits are not violated. Since the expected behavior of the reference governor is known, abnormal behavior can be an indicator of a TDS attack. For example, in [75], a reference governor based on the dynamic model of a UAV is used to detect TDS attacks. When communication delays increase due to a TDS attack, the governor limits or rejects reference updates more frequently than expected, revealing abnormal timing behavior in the networked control system.

5.1.2. FDI Attacks

Model-based algorithms, such as state estimators and observers, can also be used to detect FDI attacks. A key challenge in this context is distinguishing false data from normal system disturbances, such as sensor noise. To address this, ref. [77] proposes the use of an unknown input observer for UAVs, which is capable of detecting FDI attacks while accounting for convergence conditions in trajectory and state tracking error. Similarly, in [78], the authors approach this challenge by implementing a Kalman filter that is capable of detecting GPS spoofing attacks in UAVs while filtering out 99.73% of false positives. The proposed algorithm monitors the residual, the difference between the GPS signal measured by sensors and the signal estimated by the filter, and alerts the GCS when it exceeds a certain threshold. Residual monitoring is also employed in [79], where a sliding-mode observer is used to detect FDI attacks in electrical power grids by analyzing the system’s residuals.

5.1.3. DoS Attacks

One example of model-based detection of DoS attacks is [80], in which an adaptive observer detects DoS attacks in a cooperative adaptive cruise control system for an autonomous vehicle. Similarly, in [81], the residuals of a Kalman filter are monitored to detect DoS attacks in generalized NCSs.

5.1.4. Replay Attacks

In [82], a Kalman filter is used to successfully detect replay attacks in UAV control systems.

5.2. Learning-Based Detection

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence in which algorithms are trained on data to eventually make autonomous decisions [90]. During the training phase, ML algorithms are presented with numerous datasets containing known cyberattacks. If the algorithm is told where the attacks occur, then it will eventually recognize the attacks independently. A major advantage of many ML algorithms is that the learning agent does not require explicit knowledge of the UAV’s dynamic model, instead learning directly from data. As with prevention algorithms such as encryption, a significant concern when developing detection algorithms is the computational resources on board the UAV, which is especially true for ML-based detection algorithms [91]. Another challenge is that training and collecting sufficient real-world data may be difficult or time-consuming.

In [83], a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network is used to detect TDS attacks on a power plant control system. Similarly, ref. [84] applied logistic regression and a random forest ML algorithms to detect GPS spoofing in UAVs, achieving 98.58% accuracy. In the context of DoS attacks, ref. [85] introduced an experience-based deep learning algorithm which recognizes UAV communication behavior that is indicative of a DoS attack. Similarly, in [84], the authors propose a logistic regression and random forest ML algorithm to detect DoS attacks in UAVs.

5.3. Hybrid-Based Detection

A cyberattack detection algorithm may incorporate both model-based and learning-based elements. For example, an algorithm would qualify as hybrid if it incorporates a model-based method such as an observer that provides state estimates to a learning-based method such as a Neural Network.

An example of a hybrid detection algorithm is shown in [86], where an adaptive Kalman filter is paired with a convolutional neural network to detect FDI attacks in a power grid NCS. Similarly, in [88], model-based state estimation methods are combined with a LSTM-based deep learning model to detect FDI attacks in the NCS of a power grid. In [87], the estimated states of a NCS model are analyzed to detect FDI attacks, while a Reinforcement Learning (RL) agent adaptively updates detection parameters such as the residual threshold and observation window length. Although computational efficiency is a concern in hybrid-based detection methods, optimization algorithms combined with hybrid deep learning frameworks (e.g., Bi-GRU enhanced by metaheuristic algorithms [92]) have been applied in other domains to improve computational efficiency. Similar strategies could be explored for UAV cyberattack detection.

6. Mitigation Algorithms

Resilient mitigation algorithms are capable of diminishing the effects of a cyberattack. Common approaches to achieving this goal include model-based, learning-based, and hybrid approaches that combine both. For a comprehensive list of the cyberattack mitigation-focused papers discussed in the following section, please refer to Table 3.

Table 3.

UAV Cyberattack Mitigation Algorithms.

6.1. Model-Based Mitigation

Model-based mitigation is similar to model-based prevention in that it relies on the mathematical model that describes the kinematics of the UAV to develop a robust controller. These controllers typically have flexible dynamic models and control laws or use observers and filters to estimate system states once an attack is detected [93].

6.1.1. TDS Attacks

One model-based mitigation algorithm suited for TDS attacks is a reference governor. A Reference Governor is an auxiliary control scheme in which model-based predictions regulate the applied reference signal, ensuring that all constraints of the system are satisfied without altering the design of the main controller [107]. In [75], a reference governor is used to mitigate TDS attacks., a reference governor uses delay estimates of a UAV’s dynamic model to update its reference signal, thus maintaining stability in the presence of a TDS attack.

6.1.2. FDI Attacks

Researchers often employ robust control techniques to mitigate FDI attacks. For example, in [93], a Lyapunov-based Sliding Mode Controller for electrical power grids is proposed that is shown to be resilient to FDI attacks. Similarly, in [94], a disturbance observer for UAVs is proposed to mitigate the effects of a FDI attack and ensure stability.

6.1.3. DoS Attacks

Robust control tecniques can also carry over to mitigate DoS attacks. For example, in [95], a Lyapunov-based event-triggered adaptive output feedback control scheme for UAVs is introduced that effectively alleviates DoS attacks. In [96], the interactions between a UAV agent and an attacker are modeled using a game-theoretic approach and optimal adaptive communication protocol strategies are achieved. Another example is [97], in which an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average model and a disturbance observer are designed to mitigate DoS attacks in a MAS.

6.1.4. Replay Attacks

In [98], Lyapunov theory and linear matrix inequalities are used to design a state feedback control scheme for general cyber-physical systems to guarantee stability in the event of a replay attack. In [99], a distributed model predictive control scheme for a MAS is introduced to predict the agent’s states in the event of a replay attack.

6.2. Learning-Based Mitigation

Similar to how a ML algorithm can be trained to detect a cyberattack, it can also learn to mitigate its effects. In model-free, learning-based mitigation, the agent does not require knowledge of the system’s dynamic model. Instead, the agent is trained through repeated interaction with a simulated environment. To train a ML algorithm to mitigate an attack, simulations of the attack are carried out in which a reward is given for successfully mitigating some aspect of the attack and a penalty is given otherwise.

6.2.1. TDS Attacks

A ML agent can be trained to estimate delays in a NCS. For example, in [83], a LSTM neural network is used to estimate delays in a TDS attack on a power plant control system and modify data accordingly to ensure stability.

6.2.2. FDI Attacks

ML agents can also mitigate FDI attacks in NCSs. For example, in [100], a secure control scheme is formulated as a Markov Decision Process, which is solved by proposing a soft actor-critic deep RL algorithm. Stability of the proposed control scheme in the presence of a FDI attack is verified through simulation on a satellite and robot arm control system.

6.2.3. DoS Attacks

In the event of a DoS attack, communication between UAVs in a MAS can be dynamically rerouted. For example, in [101], communication delays between unattacked nodes are minimized through this dynamic communication routing scheme. In this case, the RL agent continuously observes the state of the network, is rewarded for maintaining reliable communication through routing adjustments, and is penalized for failure.

6.2.4. Replay Attacks

In [102], a RL agent optimizes UAV control actions during a replay attack through optimization learning.

6.3. Hybrid Hybrid-Based Mitigation

6.3.1. TDS Attacks

One example of a hybrid algorithm for mitigating TDS attacks is shown in [15], in which a Lyapunov-based controller and a neural network-based observer mitigate TDS attacks. The effectiveness of the controller is demonstrated on a leader-follower formation of UAVs. Another example is [103], in which a model-based adaptive control law is paired with a RL algorithm trained to update control gains under a TDS attack. Convergence and asymptotic stability are shown through simulation on a mass-spring-damper system under TDS attack.

6.3.2. FDI Attacks

Some examples of hybrid-based mitigation of FDI attacks are as follows. In [18], a Lyapunov-based control strategy is introduced for generalized NCSs that uses a model-based observer to estimate system states and a feed-forward neural network to mitigate FDI attacks. Similarly, in [33], an adaptive observer based on an extended Kalman filter and a neural network are used to estimate the states of an unmanned helicopter under a FDI attack. The proposed control strategy maintains trajectory tracking by modifying the control law to compensate for the detected FDI attack. Additionally, in [88], a model-based weighted least squares method is paired with a LSTN deep learning neural network to estimate the states of an electrical power grid corrupted by a FDI attack with a 91.74% success rate.

6.3.3. DoS Attacks

One example of hybrid-based mitigation of DoS attacks is in [104], in which a control scheme is introduced with a resilient control law achieved through RL policy iteration. The proposed strategy is shown to be effective through the simulation of a DoS attack on an inverted pendulum on a cart.

6.3.4. Replay Attacks

In [105], safe and efficient UAV navigation in the presence of a replay attack is ensured by a hybrid Hybrid-based mitigation algorithm. The proposed algorithm uses Lyapunov-based control methods, an observer to estimate system states, and a deep RL policy trained to generate an optimal tracking signal capable of minimizing the impact of the attack. In [106], a model-based UAV swarm control strategy is paired with a multi-task RL algorithm to develop resilient navigation and communication strategies under replay attack.

7. Summary of Findings

Based on the literature reviewed, a hierarchical classification of UAV cyberattack defense algorithms was developed, organizing them into the categories of prevention, detection, and mitigation. Robust prevention algorithms can defend against a broad range of attacks, but they are often computationally intensive and introduce latencies into a control system. In this paper, detection and mitigation algorithms were classified as model-based, learning-based, or hybrid between the two. Model-based algorithms are typically more computationally efficient; however, their effectiveness is limited by the difficulty in obtaining an accurate model describing the dynamics of the system. This challenging task becomes increasingly more difficult with increasing levels of system complexity. Learning-based algorithms are favorable because they can operate without knowledge of the system’s model but require large, representative datasets for training.

While the surveyed works differ in their assumptions and evaluation setups, several recurring trends can be observed. Many approaches assume accurate system models and full or partial state measurements, which may not hold under sensor degradation or adversarial interference. In addition, a large portion of the literature validates proposed methods primarily through simulation, with fewer studies considering HiL, ViL, or real-world experiments. These assumptions and evaluation choices significantly influence the reported resilience and highlight the need for future work that systematically examines NCS cybersecurity methods under more realistic conditions.

There is sufficient literature for the prevention, detection and mitigation of TDS, FDI, DoS, and replay attacks in control systems for power grids, chemical processing plants, and general applications; however, papers specifically discussing UAVs are less abundant. In the literature for the detection and mitigation of cyberattacks on UAV control systems, TDS and replay attacks are much less documented than FDI and DoS. Additionally, there are few papers addressing coordination attacks, where an adversary targets multiple UAVs within a MAS.

Various prevention, detection, and mitigation algorithms in the literature have often been tested in purely simulated environments, Hardware in the Loop (HiL), Vehicle in the Loop (ViL), or real-world experiments. Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages in terms of cost, feasibility, legal constraints, and legitimacy of the results. Testing a proposed algorithm’s response to an attack purely through simulation is quick, safe, and inexpensive. The drawbacks are that in a simulated environment, the full physics of the simulation may be inaccurately represented. HiL combines simulated environments with real-life hardware such as sensors, actuators, and controllers. This method remains cost-effective while obtaining a higher degree of accuracy as the complex dynamics of the hardware does not need to be modeled explicitly. ViL is when vehicle control systems such as autonomous driving are tested in real life but with some sensor data simulated. For example, the autonomous capabilities of a UAV can be tested in which its sensors are perceiving simulated pedestrians to eliminate the risk of harm to humans. Real-world testing can be expensive and may even be limited by legal constraints. For example, performing GPS spoofing or a DoS attack is illegal in the United States, even if it is for academic research [108]. The simulation type carried out for each prevention, detection, and mitigation algorithm referenced in this paper is summarized in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Summary of Prevention Techniques.

Table 5.

Summary of Detection Techniques.

Table 6.

Summary of Mitigation Techniques.

8. Conclusions

This literature review has provided an overview of the existing research on cyberattacks in UAVs. Cyberattacks discussed in this paper included time-delay switch, false data injection, denial of service, and replay attacks. Defense strategies against these threats were organized into a hierarchy consisting of prevention, detection, and mitigation. Within the detection and mitigation categories, algorithms were further classified based on whether they were model-based, learning-based, or hybrid approaches that combined both. Significant challenges with these defense methods include constraints on computational resources and wireless communication latencies. In the existing literature, most of the novel defense algorithms introduced are tested in purely simulated environments, as opposed to HiL, ViL, and real-world simulation. Although simulated environments are cost-effective and simple to produce, researchers would benefit from the higher degree of accuracy achieved by testing in HiL, ViL, and real-world environments. Future work should focus on developing robust, adaptive, and comprehensive defense strategies and building realistic simulation environments for testing and validation.

Author Contributions

Original draft preparation: B.G.; project administration and supervision: A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The U.S. National Science Foundation under grant number ECCS-EPCN-2241718.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Emre Yildirim for his time reviewing this paper and providing valuable comments. Partial support of this research was provided by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. ECCS-EPCN-2241718. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsoring agency.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sargolzaei, A.; Abbaspour, A.; Crane, C.D. Control of cooperative unmanned aerial vehicles: Review of applications, challenges, and algorithms. In Optimization, Learning, and Control for Interdependent Complex Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H.; Cui, J.Q.; Li, J.; Bi, Y.; Lan, M.; Shan, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, K.; Lin, F.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Design and implementation of an unmanned aerial vehicle for autonomous firefighting missions. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA), Kathmandu, Nepal, 1–3 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, D. A review of UAV power line inspection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Guidance, Navigation and Control: Proceedings of 2020 International Conference on Guidance, Navigation and Control, ICGNC 2020, Tianjin, China, 23–25 October 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 3147–3159. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, E.; Peng, J.; Liang, Z. A review on state-of-the-art power line inspection techniques. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 9350–9365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.L. The silent force multiplier: The history and role of UAVs in warfare. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shafique, A.; Mehmood, A.; Elhadef, M. Survey of security protocols and vulnerabilities in unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46927–46948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, H. Analysis of amazon prime air uav delivery service. J. Knowl. Inf. Technol. Syst. 2017, 12, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Xing, C.; Xie, S.; Ni, B. Construction of FANETs for user coverage and information transmission in disaster rescue scenarios. Comput. Commun. 2023, 207, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmokadem, T.; Savkin, A.V. Towards fully autonomous UAVs: A survey. Sensors 2021, 21, 6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Paranjape, A.A.; Dames, P.; Shen, S.; Kumar, V. A survey on aerial swarm robotics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, G. A survey on UAV-assisted wireless communications: Recent advances and future trends. Comput. Commun. 2023, 208, 44–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vanjani, P.; Paliwal, N.; Basnayaka, C.M.W.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Wang, H.C.; Muthuchidambaranathan, P. Communication and networking technologies for UAVs: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 168, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, E.; Daponte, P.; De Vito, L.; Picariello, F.; Tudosa, I. Sensors and measurements for UAV safety: An overview. Sensors 2021, 21, 8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Yen, K.; Abdelghani, M.; Abbaspour, A.; Sargolzaei, S. Generalized attack model for networked control systems, evaluation of control methods. Intell. Control Autom. 2017, 8, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Zegers, F.M.; Abbaspour, A.; Crane, C.D.; Dixon, W.E. Secure control design for networked control systems with nonlinear dynamics under time-delay-switch attacks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasspour, A.; Sargolzaei, A.; Victorio, M.; Khoshavi, N. A neural network-based approach for detection of time delay switch attack on networked control systems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 168, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, A.; Sargolzaei, A.; Yen, K. Detection of false data injection attack on load frequency control in distributed power systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Morgantown, WV, USA, 17–19 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sargolzaei, A. A secure control design for networked control system with nonlinear dynamics under false-data-injection attacks. In Proceedings of the 2021 American Control Conference (ACC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–28 May 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2693–2699. [Google Scholar]

- Rabah, M.A.O.; Drid, H.; Medjadba, Y.; Rahouti, M. Detection and Mitigation of Distributed Denial of Service Attacks Using Ensemble Learning and Honeypots in a Novel SDN-UAV Network Architecture. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 128929–128940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, H.S.; Rotondo, D.; Vidal, M.L.; Quevedo, J. Frequency-based detection of replay attacks: Application to a quadrotor UAV. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Systems and Control (ICSC), Marrakesh, Morocco, 23–25 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.A.; Jhanjhi, N.; Brohi, S.N.; Almazroi, A.A.; Almazroi, A.A. A secure communication protocol for unmanned aerial vehicles. Cmc-Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 601–618. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Ma, J.; Sun, C. A Survey on Security of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems: Attacks and Countermeasures. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 34826–34847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, F.; Gupta, S.K.; Hamood Alsamhi, S.; Rashid, M.; Liu, X. A survey on recent optimal techniques for securing unmanned aerial vehicles applications. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Pan, Q. A survey on cybersecurity attacks and defenses for unmanned aerial systems. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 138, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alladi, T.; Chamola, V.; Sahu, N.; Guizani, M. Applications of blockchain in unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. Veh. Commun. 2020, 23, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Omidkar, A.; Roudi, S.A.; Abbas, R.; Kim, S. Machine-learning-enabled intrusion detection system for cellular connected UAV networks. Electronics 2021, 10, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, J.; Almehmadi, A.; El-Khatib, K. Artificial intelligence for intrusion detection systems in unmanned aerial vehicles. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 99, 107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, G.; Sharma, V.; You, I.; Yim, K.; Chen, R.; Cho, J.H. Intrusion detection systems for networked unmanned aerial vehicles: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Limassol, Cyprus, 25–29 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 560–565. [Google Scholar]

- Gudla, C.; Rana, M.S.; Sung, A.H. Defense techniques against cyber attacks on unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Embedded Systems, Cyber-Physical Systems, and Applications (ESCS); The Steering Committee of The World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering and Applied Computing (WorldComp), 2018; pp. 110–116. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/b9f06d22a92d31ddb9a4d4cb4e434b34/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1976354 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Owoputi, R.; Ray, S. Security of multi-agent cyber-physical systems: A survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 121465–121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Yazdani, K.; Abbaspour, A.; Crane, C.D., III; Dixon, W.E. Detection and mitigation of false data injection attacks in networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 4281–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Arya, V.; Chui, K.T. Machine Learning-Based DDoS Mitigation Framework for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) Environment Using Software-Defined Networks (SDN). In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2023-2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–12 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2178–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari, S.; Abbaspour, A.; Yen, K.K.; Sargolzaei, A. Neural network-based active fault-tolerant control design for unmanned helicopter with additive faults. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, D.; Song, H.H.; Li, Z. Cybersecurity of unmanned aerial vehicles: A survey. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2023, 39, 182–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.K.; Gurjar, D.S.; Nguyen, H.H.; Yadav, S. Security threats and mitigation techniques in UAV communications: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 112858–112897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A. Control of Multi-Agent Systems Under Cyberattack. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Victorio, M.; Sargolzaei, A.; Khalghani, M.R. A secure control design for networked control systems with linear dynamics under a time-delay switch attack. Electronics 2021, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Yen, K.K.; Abdelghani, M.N.; Sargolzaei, S.; Carbunar, B. Resilient design of networked control systems under time delay switch attacks, application in smart grid. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 15901–15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A. Time-Delay Switch Attack on Networked Control Systems, Effects and Countermeasures. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Yen, K.K.; Abdelghani, M.N. Preventing time-delay switch attack on load frequency control in distributed power systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 7, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, V.; Pudi, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Elovici, Y. Security vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles and countermeasures: An experimental study. In Proceedings of the 2018 31st International Conference on VLSI Design and 2018 17th International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), Pune, India, 8–10 January 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Detection and defense of time-varying formation for unmanned aerial vehicles against false data injection attacks and external disturbance. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2024, 34, 1714–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Xi, Z. Health Assessment of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Formation Systems under False Data Injection Attack. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Guangzhou, China, 28–30 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 701–707. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.; Sinopoli, B. Secure control against replay attacks. In Proceedings of the 2009 47th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), Monticello, IL, USA, 30 September–2 October 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 911–918. [Google Scholar]

- Elkhider, S.M.; El-Ferik, S.; Saif, A.W.A. Denial of service attack of QoS-based control of multi-agent systems. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Cao, H.; Jiang, W.; Ni, T.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, G. Omni-Angle Assault: An Invisible and Powerful Physical Adversarial Attack on Face Recognition. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Qian, X.; Jiang, W.; Cao, H.; Zhao, Q. FIGhost: Fluorescent Ink-based Stealthy and Flexible Backdoor Attacks on Physical Traffic Sign Recognition. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Jiang, W.; Ni, T.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, Y. Itpatch: An invisible and triggered physical adversarial patch against traffic sign recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12394. [Google Scholar]

- Alenezi, M.N.; Alabdulrazzaq, H.; Mohammad, N.Q. Symmetric encryption algorithms: Review and evaluation study. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Inf. Secur. 2020, 12, 256–272. [Google Scholar]

- Aissaoui, R.; Deneuville, J.C.; Guerber, C.; Pirovano, A. A survey on cryptographic methods to secure communications for UAV traffic management. Veh. Commun. 2023, 44, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangaresi, V.O.; Jasim, H.M.; Mutlaq, K.A.A.; Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Ma, J.; Abduljaleel, I.Q.; Honi, D.G. A symmetric key and elliptic curve cryptography-based protocol for message encryption in unmanned aerial vehicles. Electronics 2023, 12, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Obaidat, M.S.; Lin, C.; Lin, Y.; Shen, Y.; Ma, J. Energy-efficient and secure communication toward UAV networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 10061–10076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ma, J.; Ma, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, H.; Ma, C.; Yu, J.; Lu, D.; Zhang, J. Lightweight secure communication mechanism towards UAV networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Big Island, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kadakia, Y.A.; Suryavanshi, A.; Alnajdi, A.; Abdullah, F.; Christofides, P.D. Encrypted model predictive control of a nonlinear chemical process network. Processes 2023, 11, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Varadharajan, V. Control of Large-Scale Networked Cyberphysical Systems Using Cryptographic Techniques. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.03470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.J.; Wu, R.B.; Zhao, Q.C. Networked Control Systems Secured by Quantum Key Distribution. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.09015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Kaushik, A.R.; Jutla, C.; Ratha, N. Enhancing privacy and security of autonomous uav navigation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Singapore, 25–27 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani, M.Y.; Khan, N.A.; Georgieva, L.; Bamahdi, A.M.; Abdulkader, O.A.; Alahmadi, A.H. Protecting attacks on unmanned aerial vehicles using homomorphic encryption. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2023, 11, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.R.; Jutla, C.; Ratha, N. Towards Building Secure UAV Navigation with FHE-Aware Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Porto, Portugal, 23–25 February 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Suryateja, P.S.; Rao, K.V. A Survey on Lightweight Cryptographic Algorithms in IoT. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2024, 24, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshavi, N.; Tristani, G.; Sargolzaei, A. Blockchain applications to improve operation and security of transportation systems: A survey. Electronics 2021, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló Ferrer, E. The blockchain: A new framework for robotic swarm systems. In Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–14 November 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 1037–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Li, M.; Alzahrani, B.; Alotaibi, R.; Barnawi, A.; Ai, Q. A blockchain-based secure crowd monitoring system using UAV swarm. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulianos, A.; Litke, A. Blockchain technology for secure communication and formation control in smart drone swarms. Future Internet 2023, 15, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.U.; Shah, A.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, S.S.; Alroobaea, R.; Hussain, S. A scalable blockchain based framework for efficient IoT data management using lightweight consensus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Amaro, J.; Osório, F.S.; RLJC, B.K. Authentication methods for UAV communication. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Barcelona, Spain, 29 June–3 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1210–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, R.; Xiao, Y.; Shao, J.; Qin, J. An analysis on optimal attack schedule based on channel hopping scheme in cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 51, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atheeq, C.; Gulzar, Z.; Al Reshan, M.S.; Alshahrani, H.; Sulaiman, A.; Shaikh, A. Securing uav networks: A lightweight chaotic-frequency hopping approach to counter jamming attacks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 38685–38699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.; Park, D.; Yim, Y.; Kim, K.; Yang, S.K.; Robinson, M. Security authentication system using encrypted channel on UAV network. In Proceedings of the 2017 First IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC), Taichung, Taiwan, 10–12 April 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sargolzaei, A.; Abbaspour, A.; Al Faruque, M.A.; Salah Eddin, A.; Yen, K. Security challenges of networked control systems. In Sustainable Interdependent Networks: From Theory to Application; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Liu, W.; Lim, T.J. Wireless Resource Allocation with Collaborative Distributed and Centralized DRL under Control Channel Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.; Steup, C. The vulnerability of UAVs to cyber attacks-An approach to the risk assessment. In Proceedings of the 2013 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CYCON 2013), Tallinn, Estonia, 4–7 June 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Puchaty, E.M.; DeLaurentis, D.A. A performance study of UAV-based sensor networks under cyber attack. In Proceedings of the 2011 6th International Conference on System of Systems Engineering, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 27–30 June 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Mitra, U. Security against false data-injection attack in cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2019, 7, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, O.; Codrean, A. Networked Control of a Small Drone Resilient to Cyber Attacks. Drones 2024, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Sahoo, A.; Bhowmick, C.; Jagannathan, S. An optimal hybrid learning approach for attack detection in linear networked control systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 6, 1404–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Yang, F.; Lyu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Pan, Q. Observer based attack detection and security control for UAVs against attacks on desired trajectory. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liao, Y.; Ni, S.; Zhang, A.; Cheng, L. Research on UAV sensor attack detection based on Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP), Nanjing, China, 22–24 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1228–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Adeli, M.; Hajatipour, M.; Yazdanpanah, M.J.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H.; Shafieirad, M. Optimized cyber-attack detection method of power systems using sliding mode observer. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 205, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, H.; Jia, Z.; Cui, C.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, Y. An adaptive observer design for denial-of-service attack detection in platoon. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2023, 44, 2148–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.O. Detection and Characterization of Actuator Attacks Using Kalman Filter Estimation. Master’s Thesis, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adeli, M.; Hajatipour, M.; Yazdanpanah, M.J.; Shafieirad, M.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H. Distributed trust-based unscented Kalman filter for non-linear state estimation under cyber-attacks: The application of manoeuvring target tracking over wireless sensor networks. IET Control Theory Appl. 2021, 15, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, P.; Lou, X.; Chen, Y.; Tan, R.; Yau, D.K.; Chen, D.; Winslett, M. Learning-based simultaneous detection and characterization of time delay attack in cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3581–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaej, A.; Ahanger, T.A.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Ullah, I.; Yousufudin, M. Smart cybersecurity framework for IoT-empowered drones: Machine learning perspective. Sensors 2022, 22, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Abdollahi, A.; Khan, M.A.; Uddin, M.I.; Ullah, I. Securing Against DoS/DDoS Attacks in Internet of Flying Things using Experience-based Deep Learning Algorithm. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Bo, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kan, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power CPS false data injection attacks with improved AKF and GRU-CNN. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 1490–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, I.; Adhikary, S.; Dey, S. An RL-based adaptive detection strategy to secure cyber-physical systems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.02872. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Konstantinou, C.; Jin, Y. Chimera: A hybrid estimation approach to limit the effects of false data injection attacks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Aachen, Germany, 25–28 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, G.; Bishop, G. An Introduction to the Kalman Filter. 1995. Available online: http://www.ceri.memphis.edu/people/rsmalley/ESCI7355/welch%20and%20bishop%20-%20kalman.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Baig, Z.; Syed, N.; Mohammad, N. Securing the smart city airspace: Drone cyber attack detection through machine learning. Future Internet 2022, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Chen, R. Adaptive intrusion detection of malicious unmanned air vehicles using behavior rule specifications. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2013, 44, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, G.S.; Meesala, M.K.; Addula, S.R.; Ravipati, P. Optimizing Retail Supply Chain Sales Forecasting with a Mayfly Algorithm-Enhanced Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, A.; Sargolzaei, A.; Forouzannezhad, P.; Yen, K.K.; Sarwat, A.I. Resilient control design for load frequency control system under false data injection attacks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 7951–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Yu, X.; Guo, K.; Qiao, J.; Guo, L. Detection, estimation, and compensation of false data injection attack for UAVs. Inf. Sci. 2021, 546, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Yi, C.; Chen, L.; Su, Y. Event-triggered adaptive output feedback control of unmanned aerial vehicles under hybrid attacks. IET Control Theory Appl. 2024, 18, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairaj, A.; Javaid, A.Y. Game theoretic solution for an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle network host under DDoS attack. Comput. Netw. 2022, 211, 108962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Event-triggered resilient consensus control of multiple unmanned systems against periodic DoS attacks based on state predictor. Secur. Saf. 2023, 2, 2023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.F.; Lacerda, M.J. State-Feedback Control for Cyber-Physical Discrete-Time Systems under Replay Attacks: An LMI Approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7946710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzè, G.; Tedesco, F.; Famularo, D. Resilience against replay attacks: A distributed model predictive control scheme for networked multi-agent systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2020, 8, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yao, W.; Sun, G.; Wu, L.; Wu, C.; Yao, W.; Sun, G.; Wu, L. Deep Reinforcement Learning Control Approach to Mitigating Attacks. In Security of Cyber-Physical Systems: State Estimation and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Jia, Z.; Dong, C.; Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q. Routing recovery for UAV networks with deliberate attacks: A reinforcement learning based approach. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2023-2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–8 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 952–957. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Ding, W.; Zhou, J. Reinforcement learning solution for cyber-physical systems security against replay attacks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Chen, B.; Yu, L.; Liu, S. Adaptive output regulation for cyber-physical systems under time-delay attacks. Control Theory Technol. 2022, 20, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Gao, W.; Vamvoudakis, K.G.; Jiang, Z.P. Resilient Learning-Based Control Under Denial-of-Service Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07766. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Mitsopoulos, K.; Romagnoli, R. Reinforcement learning-based optimal control and software rejuvenation for safe and efficient uav navigation. In Proceedings of the 2023 62nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Singapore, 13–15 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 7527–7532. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C. End-to-end multi-task reinforcement learning-based UAV swarm communication attack detection and area coverage. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 316, 113390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Reference Governors for MIMO Systems and Preview Control: Theory, Algorithms, and Practical Applications; The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College: Burlington, VT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Institute, S.R. SwRI Develops System to Legally Test GPS Spoofing Vulnerabilities in Automated Vehicles. 2019. Available online: https://www.autonomousvehicleinternational.com/news/safety/swri-develops-system-to-legally-test-gps-spoofing-vulnerabilities-in-avs.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.