Research on Scale Factor Synthesis Modeling Methods for 8/20 μs Impulse Waveforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

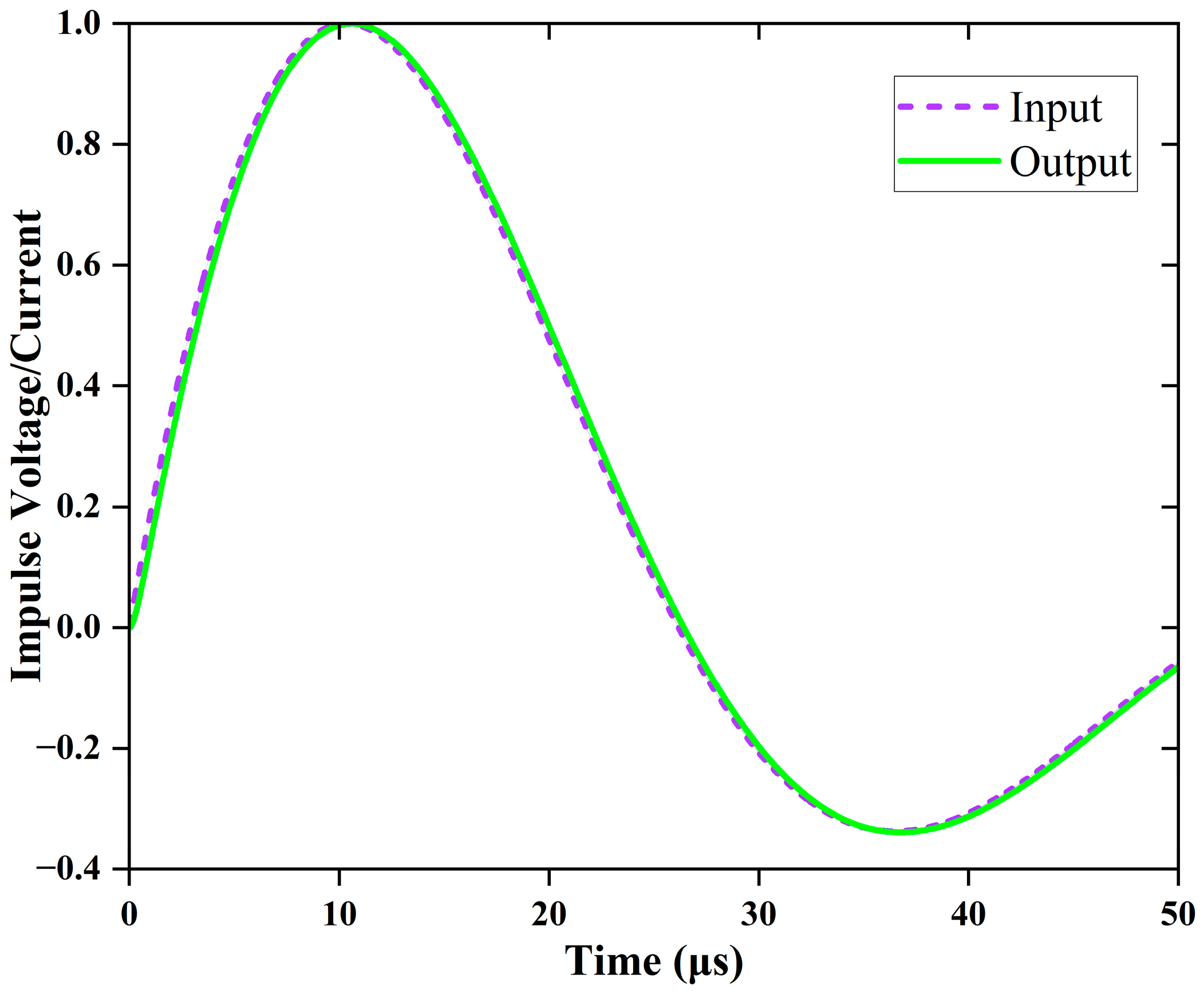

- A tailored synthetic model for 8/20 μs waveforms: Systematic derivation and establishment of a synthetic impulse scale factor model specifically designed for the exponentially damped sinusoidal 8/20 μs impulse current waveform, addressing a critical gap in the traceability of non-double-exponential impulses.

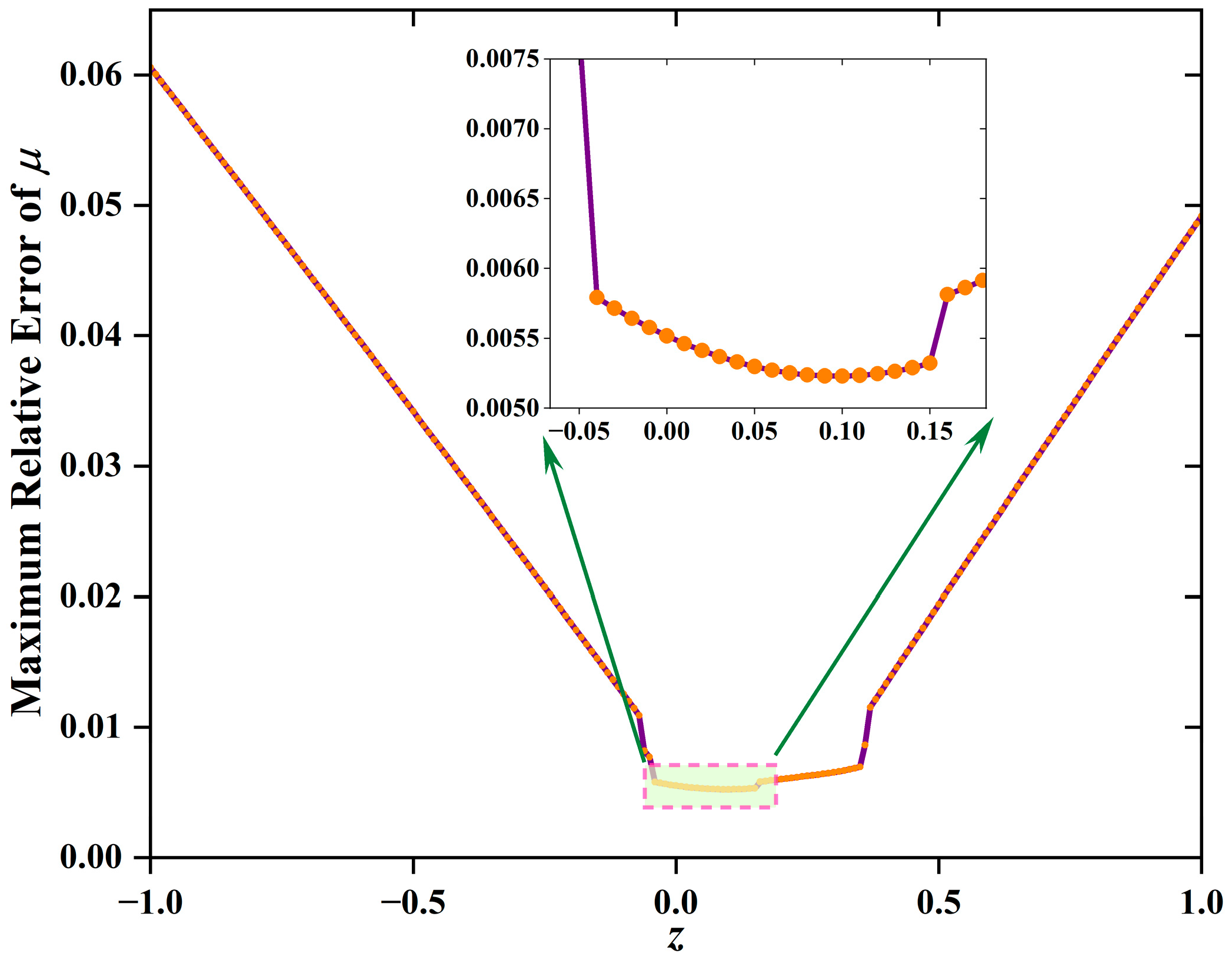

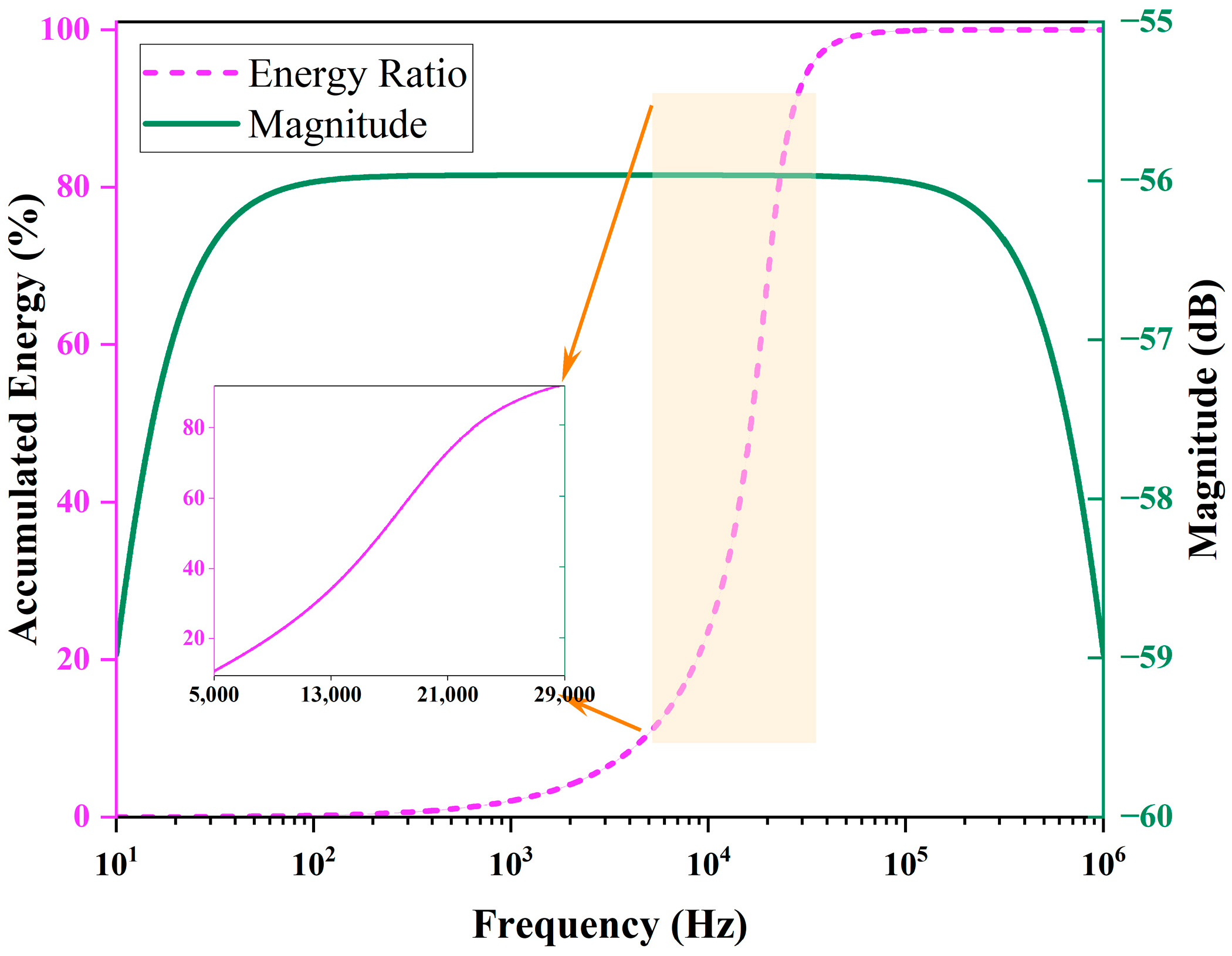

- Fractional-order optimization for error suppression: Introduction of a novel bilevel optimization framework to determine the optimal fractional-order parameter z, effectively suppressing the model’s inherent nonlinear error by an order of magnitude compared to conventional approaches.

- An efficient frequency band division strategy: Development of an optimized frequency band division strategy that reduces the required calibration frequency points by approximately 39% while maintaining synthesis accuracy, significantly enhancing practical measurement efficiency.

2. Synthetic Model of Impulse Scale Factor

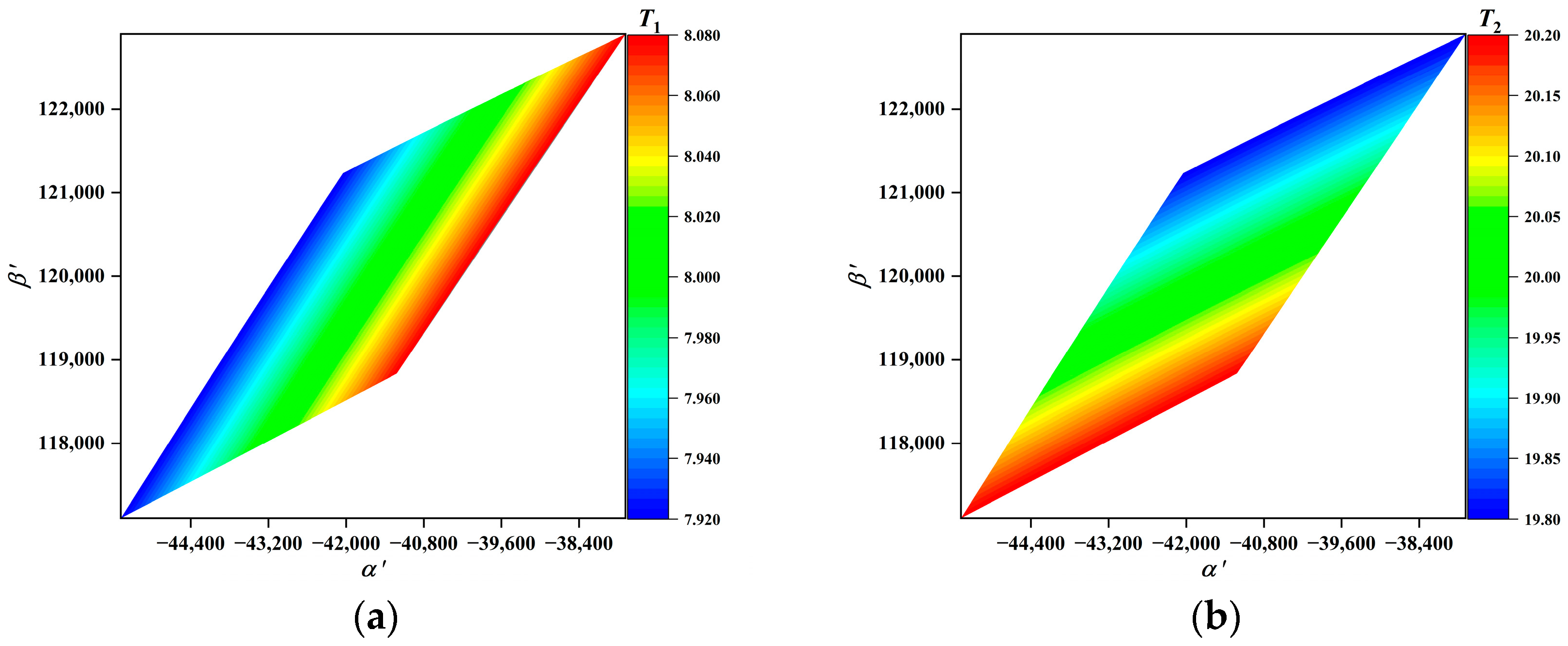

3. Determination of z

4. Frequency Band Division Strategy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

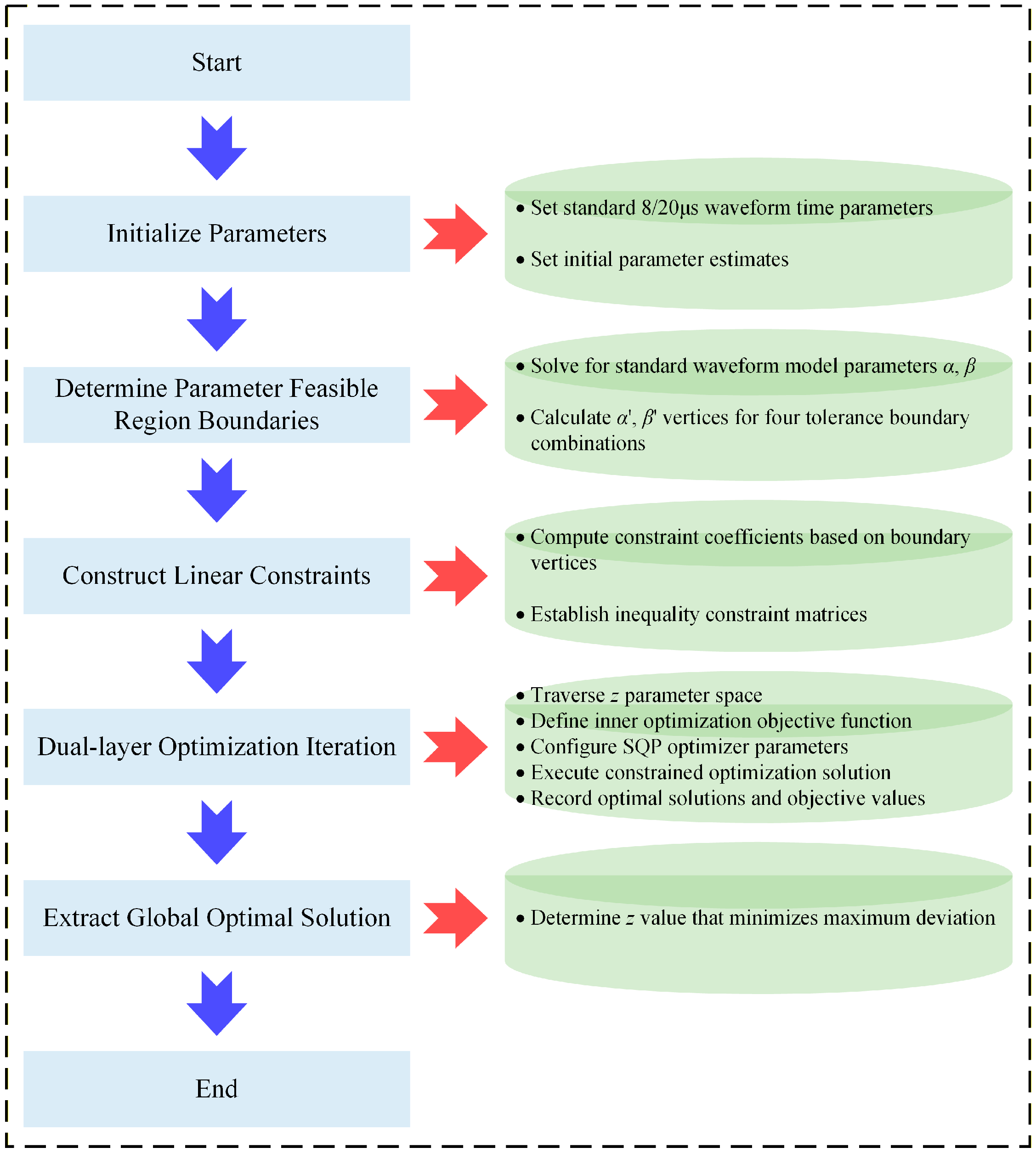

| Algorithm A1. Optimization procedure for the optimal fractional-order z. |

| Input: Standard waveform: T1 = 8 μs, T2 = 20 μs, initial guess: x0 = [41,875, 120,000], z search range: [−1, 1] with step 0.01 Output: Optimal z value, corresponding maximum deviation |

| 1: Define objective function root2d(x) that matches waveform time parameters T1 and T2; 2: Solve α, β = fsolve(root2d, x0) |

| // Step 1: Solve for standard waveform parameters |

| 3: For four combinations of T1 ± 1% and T2 ± 1%: 4: Solve α′_vertex, β′_vertex = fsolve(root2d, x0) 5: Store vertices in vertex_set |

| // Step 2: Calculate feasible region boundary vertices |

| 6: For each edge between consecutive vertices: 7: Calculate line equation coefficients 8: Add linear inequality constraint to matrix A and vector b |

| // Step 3: Establish linear constraints from boundary vertices |

| 9: Initialize results container, for each z in search range: 10: Define objective function: f(α′, β′) = |μ(α, β, α′, β′, z) − 1| 11: Configure optimizer with SQP algorithm and tight tolerances 12: Solve [α′_opt, β′_opt] = fmincon(−f, [α, β], A, b, options) 13: Store z and deviation = −f(α′_opt, β′_opt) |

| // Step 4: Optimization over z parameter space |

| 14: Find z_optimal that minimizes the maximum deviation 15: Return z_optimal and corresponding parameters |

| // Step 5: Extract optimal solution |

References

- Huang, L.; Xiang, Z.; Deng, B.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Mao, Q.; Cui, Y.; Xie, M.; Meng, J. A compact gigawatt pulsed power generator for high-power microwave application. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2023, 70, 3885–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Dong, Z.; Ren, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, K.; Zhang, C. Application Research on Fiber-Optic Current Sensor in Large Pulse Current Measurement. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1507, 072015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, Y. The application of high voltage pulses in the mineral processing industry—A review. Powder Technol. 2021, 393, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, W.; He, L.; Gao, R.; Jia, Y. On the mechanism of high-voltage pulsed fragmentation from electrical breakdown process. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 4593–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Su, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Qiu, W. A novel dual-element catheter for improving non-uniform rotational distortion in intravascular ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 70, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Su, M.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Yu, Y.; Qiu, W. A novel coded excitation imaging platform for ultra-high frequency (>100 mhz) ultrasound applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 72, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yutthagowith, P. Rogowski coil with a non-inverting integrator used for impulse current measurement in high-voltage tests. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2016, 139, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Jiao, H.; Huo, F.; Shen, Z. Lightning current measurement method using rogowski coil based on integral circuit with low-frequency attenuation feedback. Sensors 2024, 24, 4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzaretti, A.E.; Santos, S.L.F.; Küster, K.K.; Toledo, L.F.R.B.; Ravaglio, M.A.; Piantini, A.; da Silva Pinto, C.L. An integrated monitoring system and automatic data analysis to correlate lightning activity and faults on distribution networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 153, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaglio, M.A.; Küster, K.K.; Santos, S.L.F.; Toledo, L.F.R.B.; Piantini, A.; Lazzaretti, A.E.; de Mello, L.G.; da Silva Pinto, C.L.D. Evaluation of lightning-related faults that lead to distribution network outages: An experimental case study. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 174, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.M.; Yin, Y.B.; Wang, W. Lightning current measurement form and arrangement scheme of transmission line based on point-type optical current transducer. Sensors 2023, 23, 7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Yu, W.B.; Han, Y.; Duan, F.W. Study on the application of optical current sensor for lightning current measurement of transmission line. Sensors 2019, 19, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Long, Z.; Li, W.; Xie, S.; Hu, K.; Ma, Q. Research on standard wave source for impulse current. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 8th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Changsha, China, 16–18 May 2025; pp. 3104–3108. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Lin, F.; Zhou, F.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Fan, J.; Hu, K.; Li, F.; Xie, S. Development and traceability method of a 100 kA reference impulse current measuring system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 59, 2246–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakimoto, T.; Shimizu, H.; Ishii, M. Performance evaluation of national standard class measurement system for lightning impulse voltage. IEEJ Trans. Power Energy 2007, 127, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate, D.; Blanc, I.; Fortuné, D. Development of a measurement setup for high impulse currents. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2013, 62, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havunen, J.; Hällström, J. Reference switching impulse voltage measuring system based on correcting the voltage divider response with software. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Liu, Y.; Lin, M.; Li, L.; Lin, F.; Long, Z.; Diao, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, J. Traceability method of measuring system for arbitrary high-voltage and high-current impulses. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 21725–21733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Zhou, F.; Fan, J.; Diao, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Hu, K.; Lin, F. Evaluation method of impulse voltage scale factor based on energy spectral density. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Musaed, A.-S.; Yousof, M.F.M. Generation of impulse current using microcircuit: Based on IEC standard. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy (PECon), Melaka, Malaysia, 28–29 November 2016; pp. 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, H.; Katsuki, S.; Redondo, L.; Akiyama, M.; Pemen, A.J.M.; Huiskamp, T.; Beckers, F.J.C.M.; van Heesch, E.J.M.; Winands, G.J.J.; Voeten, S.J.; et al. Pulsed power technology. In Bioelectrics; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 41–107. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Representative Works | Core Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Source/Component-Based | [13,14,15,16] | Constructs a measurement system using a standard impulse current source or independently calibrated components (e.g., shunts, digitizers), achieving traceability via direct comparison or the product of component scale factors. | Intuitive concept and relatively straightforward implementation. Capable of providing standard waveforms with high repeatability [13]. | Developing high-amplitude standard sources is costly and results in complex systems [14]. Often assumes the impulse scale factor equals the DC/low-frequency scale factor, failing to fully consider the spectral characteristics of the waveform [15]. Traceability accuracy is limited by the inherent accuracy of the standard source/components, making further improvement difficult [16]. |

| Single-Frequency Method | [17] | Assumes the measuring system has an ideally flat frequency response, equating the impulse scale factor to the AC scale factor at a single frequency (e.g., power frequency). | Simple to implement. | Neglects the system’s non-ideal frequency response and the broad spectrum of the impulse waveform, potentially leading to significant deviations [17]. |

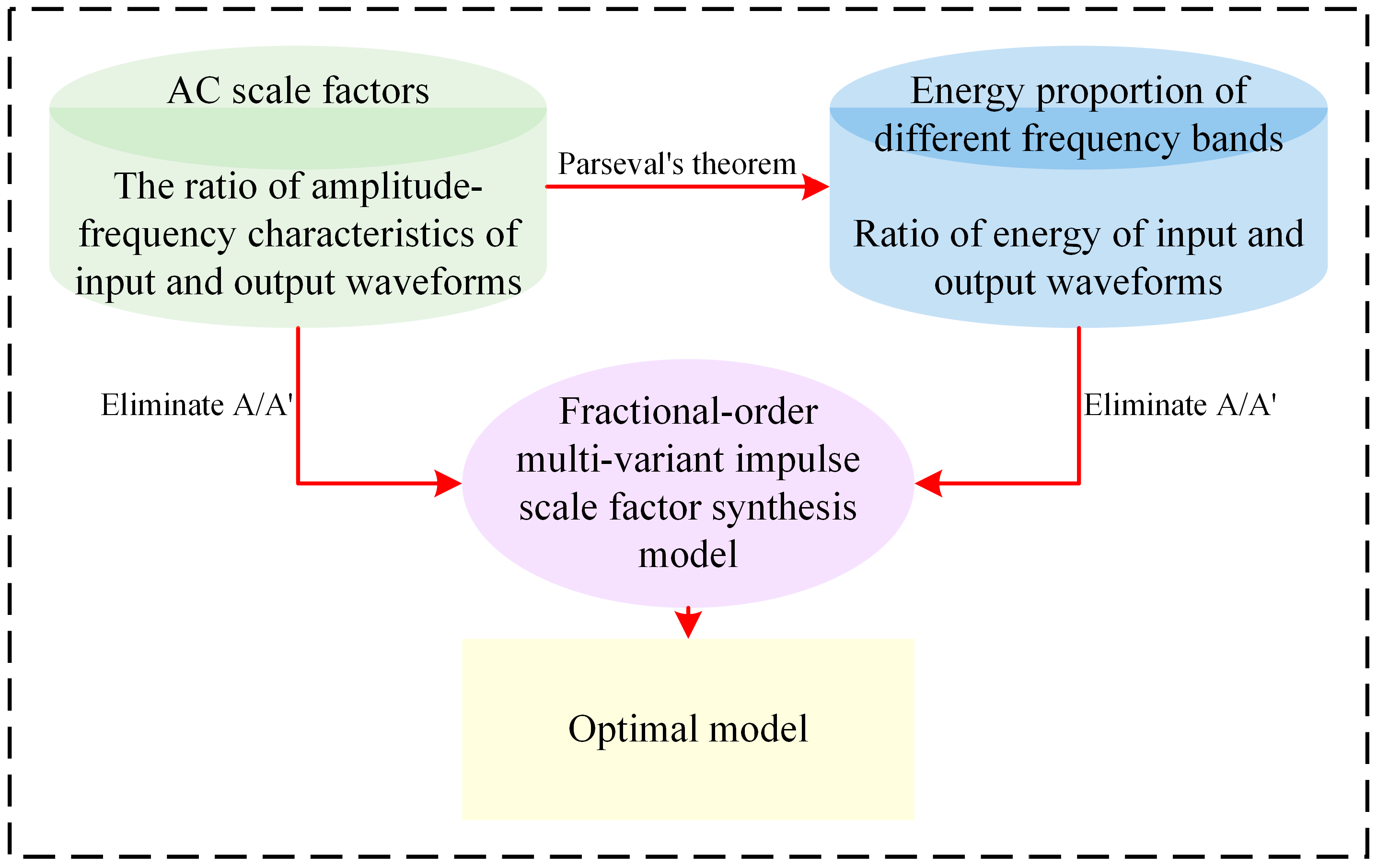

| Multi-Frequency Synthesis Method | [18,19] | Models the impulse scale factor as a weighted synthesis of AC scale factors at multiple frequencies based on Parseval’s theorem and energy spectral density. | Theoretically more rigorous, significantly improving traceability accuracy [18,19]. Establishes a direct link between impulse scale factor and AC standards through frequency domain analysis. | Existing research primarily focuses on standard lightning impulse voltages (e.g., 1.2/50 μs), with insufficient systematic study and model optimization tailored for the parameter sensitivity of the 8/20 μs impulse current waveform [18,19]. |

| Wl (Hz) | wu (MHz) | λ | Actual Impulse Scale Factor | Relative Error of Model Before Optimization (%) [19] | Relative Error of Optimized Model (Conventional Band Division) | Relative Error of Optimized Model (Proposed Band Division) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.2 | 2000 | 370.8542 | −3.4939 | 0.2047 | 0.1004 |

| 100 | 0.5 | 5000 | 366.1378 | −5.3509 | 0.0929 | 0.0287 |

| 100 | 1 | 10,000 | 365.577 | −5.6626 | 0.0483 | −0.0176 |

| 10 | 0.2 | 2000 | 368.9269 | 2.3409 | 0.1367 | 0.1019 |

| 10 | 0.5 | 5000 | 363.9232 | 0.3636 | 0.0159 | 0.0185 |

| 10 | 1 | 10,000 | 363.2452 | 0.0291 | −0.0296 | −0.0291 |

| 1 | 0.2 | 2000 | 368.7338 | 2.4267 | 0.1805 | 0.1469 |

| 1 | 0.5 | 5000 | 363.7013 | 0.4483 | 0.0587 | 0.0623 |

| 1 | 1 | 10,000 | 363.0117 | 0.1136 | 0.0131 | 0.0146 |

| wl (Hz) | wu (MHz) | λ | Actual Impulse Scale Factor | Relative Error of Model Before Optimization (%) [19] | Relative Error of Optimized Model (Conventional Band Division) | Relative Error of Optimized Model (Proposed Band Division) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.2 | 3500 | 360.9538 | 0.9033 | 0.1124 | 0.1140 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 8750 | 359.3379 | 0.1595 | 0.0260 | 0.0279 |

| 0 | 1 | 17,500 | 359.1132 | 0.0415 | 0.0074 | 0.0079 |

| Performance | Existing Model [19] | Proposed Model |

|---|---|---|

| Fractional-Order Characteristics | Unoptimized (default z = −1) | Optimization (adaptive determination of z-value based on time parameters of input and output waveforms) |

| Accuracy | Fair or poor | Higher |

| Applicable Waveforms | Only applicable to double-exponential waves (1.2/50 μs) | Suitable for double-exponential waves (1.2/50 μs) and exponentially damped sinusoidal oscillations waves (8/20 μs) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, S.; Lin, M.; Wang, L.; Cai, S.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yang, N.; Long, Z.; Li, W. Research on Scale Factor Synthesis Modeling Methods for 8/20 μs Impulse Waveforms. Electronics 2026, 15, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010164

Xie S, Lin M, Wang L, Cai S, Zeng Y, Ma Q, Yang N, Long Z, Li W. Research on Scale Factor Synthesis Modeling Methods for 8/20 μs Impulse Waveforms. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010164

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Shijun, Mingxing Lin, Liang Wang, Shiping Cai, Yi Zeng, Qixiao Ma, Ning Yang, Zhaozhi Long, and Wenting Li. 2026. "Research on Scale Factor Synthesis Modeling Methods for 8/20 μs Impulse Waveforms" Electronics 15, no. 1: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010164

APA StyleXie, S., Lin, M., Wang, L., Cai, S., Zeng, Y., Ma, Q., Yang, N., Long, Z., & Li, W. (2026). Research on Scale Factor Synthesis Modeling Methods for 8/20 μs Impulse Waveforms. Electronics, 15(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010164