Abstract

Financial institutions face data quality (DQ) challenges in regulatory reporting due to complex architectures where data flows through multiple systems. Data consumers struggle to assess quality because traditional DQ tools operate on data snapshots without capturing temporal event sequences and business contexts that determine whether anomalies represent genuine issues or valid behavior. Existing approaches address either semantic representation (ontologies for static knowledge) or temporal pattern detection (event processing without semantics), but not their integration. This paper presents CEDAR (Contextual Events and Domain-driven Associative Representation), integrating financial ontologies with event-driven processing for context-aware DQ assessment. Novel contributions include (1) ontology-driven rule derivation that automatically translates OWL business constraints into executable detection logic; (2) temporal ontological reasoning extending static quality assessment with event stream processing; (3) explainable assessment tracing anomalies through causal chains to violated constraints; and (4) standards-based design using W3C technologies with FIBO extensions. Following the Design Science Research Methodology, we document the first, early-stage iteration focused on design novelty and technical feasibility. We present conceptual models, a working prototype, controlled validation with synthetic equity derivative data, and comparative analysis against existing approaches. The prototype successfully detects context-dependent quality issues and enables ontological root cause exploration. Contributions: A novel integration of ontologies and event processing for financial DQ management with validated technical feasibility, demonstrating how semantic web technologies address operational challenges in event-driven architectures.

1. Introduction

The 2007–2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was a turning point for the financial sector. Poor data and risk management led to the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers. The international Basel Committee on Banking Supervision raised concerns regarding banks’ abilities to accurately and timely define their risk exposures across processes.

Financial institutions (FIs) are regulated domestically to maintain financial market stability and submit standardized reports to regulators, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key regulatory reports.

Current challenges in regulatory reporting stem from the fact that the data are sourced from multiple legacy systems, requires complex transformation requirements, and reporting adheres to strict accuracy requirements and short submission deadlines, with heavy penalities for errors. Post-GFC, regulators have focused on operational risk as a key driver in the accuracy of regulatory reports required. These regulatory reports are derived using enterprise-level data processes, driving FIs towards a data-driven mindset. Regulators are evermore data-centric, adding explicit data risk requirements and overseeing operational reviews. A key aspect of data management is ensuring Data Quality (DQ), i.e., data fit for purpose, throughout data processes. Modern financial markets and FIs create, use and distribute Big Data (highly heterogeneous, quickly generating, large size), complicating the DQ management process.

Data consumers, defined as those receiving data to be used to create the regulatory reports, are at the end of the data process. By this point, several business and technical transformations have been applied to the source data, making it difficult for data consumers to understand the data received and therefore assess its quality. Globally, tech debt-driven issues around complex data architecture, low interoperability and a mixed IT infrastructure led to difficulties in implementing cost effective, efficient and effective DQ management practices.

This challenge is exacerbated by growing technical debt in financial institutions that has led to complex and fragmented data architectures, with limited system interoperability and a mixed technology infrastructure. These factors make it difficult to implement cost-effective, efficient and standardized data quality management practices.

As FIs have evolved into data-driven enterprises, there is an opportunity to uplift DQ processes. Current research has focused on using machine learning methods as part of automated, enterprise DQ management tools. In parallel, FIs, regulators and researchers are currently developing financial ontologies to standardise definitions and taxonomies in the sector. This need has risen as financial markets and instruments have become much more complicated and aggregated sector risk has started to become a key focus for regulators. However, there is a gap as to how these two approaches can be utilised together.

The main contribution of this paper is to present a novel framework underpinned by event-based abstractions to bridge the gap between the use of DQ methods and ontologies in financial data processes. The focus is on data consumers needing to understand what data represents (i.e., its context) before its use. Therefore, the use case of the framework for this paper will be to support data contextualisation as a key process in the DQ management activities of data consumers producing regulatory reports.

The specific problem this paper addresses is the challenge faced by data consumers who receive processed data at the end of complex financial data pipelines. These consumers, typically business users creating regulatory reports, must undertake the following: (1) Understand what the received data represents within their business context. (2) Assess if there are data quality issues before using it for regulatory purposes. (3) Do this assessment efficiently despite limited visibility into upstream transformations. (4) Handle increasing data volumes and complexity while maintaining accuracy.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature on FI architectures, discusses the opportunities and shortcomings of current DQ management methods, and identifies research gaps; Section 3 describes the methodology and design of the proposed framework; Section 4 details the architecture and operation of the framework; Section 5 covers the implementation for the iteration; Section 6 discusses the results of the implementation and evaluates it against discussed criteria; and Section 7 presents future work and closing remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Academic Review

FIs are creating and using big data [1], which is defined as large volumes of heterogeneous data that grow rapidly and is characterised by the ‘V’s of Big Data’ (volume, variety, velocity and veracity) [2]. In this paper, we will focus primarily on veracity, as a indicator of data quality (DQ). DQ is data that are fit for use, and generally assessed from the perspective of the data user [3]. DQ is assessed in accordance with defined dimensions (e.g., accuracy, completeness, consistency) and associated metrics [4]. In academic and industrial literature, many DQ frameworks have been proposed, ranging from generic high-level to industry-specific ones that can be applied throughout different steps of the DQ management process and data lineage [5]. While these frameworks define a DQ management method, their application is limited because of the context of the application of specific dimensions and metrics is generally dataflow dependent and relies on structured data. These frameworks tend to focus on specific points of the data lifecycle as opposed to holistic DQ management [2]. DQ assessment methods also tend to use profiling and data sampling to reduce processing requirements [6]. Automated assessment processes have been designed for enterprise use but are more effective at detecting context independent DQ issues than context-dependent ones [7]. DQ detection techniques, seen in many enterprise tooling [8], have also used models such as machine learning models for pattern detection or rule-based models. However, these methods alone may not be efficient or accurate enough when applied to Big Data due to the curse of dimensionality, difficulty in detecting relevant data attributes, and the speed at which data are created [9].

FIs may experience DQ issues across the enterprise, ranging from untimely reporting to inaccurate or incomplete data capture. These issues are further exasperated through tech debt that has risen from ongoing technological adoption. A key limitation of DQ management for FIs is the data architecture resulting from complex and everchanging business processes creating data and the resulting data lineage [10]. Generally, FIs will have a bow-tie architecture, with many diverse inputs from data producers being standardised via a data processing teams, and then shared with data consumers producing diverse range of outputs (regulatory or otherwise) [11]. This leads to high data heterogeneity and a need to orchestrate and manage metadata as processes that involve different teams and data roles. FIs typically lean towards a centralised enterprise data management process to support Big Data DQ management [1]. As a result, a data consumer producing a regulatory report may not be able to assess the quality of the data received and may therefore be unable to determine what is unusual data, and what the data represents.

With the increase in big data, taxonomies and business knowledge stored via ontologies have become valuable additions to the DQ management toolkit [12]. In parallel, the finance sector is developing open-source ontologies to standardise definitions and processes across institutions and enable regulators to aggregate risk at a sector level [13].

Financial Domain Ontologies. Several ontologies have been developed to formalize financial concepts and support regulatory compliance. The Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO) [14] provides machine-readable definitions of financial instruments, organizations, and contractual relationships using OWL-DL, enabling semantic consistency across financial systems. For regulatory reporting, specialised ontologies have been developed for Basel III capital requirements [15], defining concepts such as risk-weighted assets and capital buffers with logical axioms that capture regulatory constraints.

Data Quality Ontologies. Complementing domain-specific ontologies, several frameworks address data quality assessment across domains. The Data Quality Ontology (DQO) [16] models quality dimensions (accuracy, completeness, timeliness) and their relationships, providing a vocabulary for expressing quality metadata. The Data Quality Assessment Methodology (DQAM) [17] builds on this foundation by incorporating semantic reasoning to automatically detect quality issues based on ontological constraints. Similarly, the Total Data Quality Management (TDQM) framework [18] has been formalized as an ontology to support systematic quality improvement processes.

Integration for Financial Data Quality. The relationship between these two categories is synergistic: domain-specific financial ontologies define what concepts mean and their business constraints, while general DQ ontologies provide how to assess quality of those concepts. For instance, FIBO defines that a “derivative contract” must reference an underlying asset, while DQAM provides the framework to check whether this referential integrity constraint is satisfied in actual data. This integration enables automated validation where domain semantics inform quality rules. Modern triple stores such as Stardog [19] support this integration by combining ontology reasoning (validating that data conforms to FIBO definitions) with constraint validation (checking SHACL rules derived from quality requirements), allowing both semantic consistency and data quality checks within a unified infrastructure.

These ontology-based approaches enable the following:

- Formal, machine-readable definitions of quality dimensions;

- Domain-specific constraint capture through logical axioms;

- Automated validation via semantic reasoning;

- Cross-institutional semantic interoperability.

The rise of financial ontologies has been primarily driven by the Bank of International Settlements’ future vision for a globally standard data infrastructure that operates in real-time with a higher granularity [20]. Many domestic regulators are also signalling future regulation to focus on standardisation, interoperability and data lineage as key pillars of data risk [21]. This gives rise to the potential of ontologies being used to address the challenges posed by the research gaps.

To address these gaps, the focus of this paper is on the following research questions:

- How can contextual information be represented in datasets used by data consumers producing regulatory reports in a way that helps identifying DQ issues?

- How can ontologies be leveraged in data processes and align with modern data quality methods in existing FI architectures?

2.2. EvaluationCriteria

The business problem that arises is that it is difficult to have a complete understanding of the transformations occurring in a big data process used for financial regulatory reporting and use this to inform the DQ issues expected throughout the data process. Data consumers will make data observations but lack the tools to contextualise these observations easily. While data architecture in banking focuses on transparent, streamlined data processes, there is a lack of focus on data architecture to support big DQ detection process. It is challenging for business teams who use data (i.e., non-technical data consumers) to understand, control, modify and maintain DQ detection processes used for financial regulatory reporting. This is further exacerbated in the context of big data. Therefore, three evaluation criteria will be used in this paper:

- Context representation;

- Scalability and maintainability;

- Transparency to business users.

Based on academic and industry research, the evaluation criteria can be compared against several approaches an FI can take to alleviate these challenges, as summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation criteria.

3. Framework Design

3.1. Methodology

This research follows the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) framework [22], which is appropriate when research questions can be addressed through the creation and evaluation of innovative artifacts. DSRM proceeds through six activities: (1) problem identification and motivation, (2) definition of objectives, (3) design and development, (4) demonstration, (5) evaluation, and (6) communication. Importantly, DSRM is inherently iterative—each cycle involves design, demonstration, and evaluation, with findings informing subsequent refinements [23].

Iterative DSRM Process. This paper documents the first design iteration of CEDAR. Following established practices in design science [24,25], early iterations focus on the following:

- Design novelty: Does the artifact represent a novel solution approach?

- Technical feasibility: Can the proposed design be implemented with existing technologies?

- Proof-of-concept: Does the artifact work for simplified scenarios?

Later iterations address:

- Scalability: Does the artifact perform at realistic scales?

- Comparative effectiveness: Does it outperform alternative approaches?

- User utility: Does it provide value in real-world use?

- Organizational impact: Does deployment improve outcomes?

This staged approach is methodologically sound—attempting comprehensive evaluation before establishing feasibility risks wasting resources on fundamentally flawed designs. As Hevner notes: “The rigor and completeness of design evaluation should be appropriate for the maturity and importance of the artifact” [26].

3.1.1. Methodology Application

The proposed artifact is in the form of a framework named CEDAR, which stands for Contextual Events and Domain-driven Associative Representation. CEDAR relies on different models (see Section 3.2) to contextualise temporal data and an ontology to represent the knowledge across the framework (see Section 3.3). The framework needs to be agile as it is intended to be applicable across any area within this architecture, and adaptable to the data quality requirements of the data processes in scope.

The motivating example used to design and explain the framework’s models will be based on trading an equity-based derivative, a financial instrument where trading patterns can be linked to an underlying equity (such as a stock).

3.1.2. Evaluation Approach

Given that this paper follows DSRM, it is important to contextualize evaluation approaches in related work to appropriately scope our validation strategy.

Evaluation in Ontology-Based Systems. Ontology evaluation typically proceeds through multiple stages [27]: (1) verification of technical correctness (syntax, consistency), (2) validation against competency questions, (3) application-based evaluation with real data, and (4) user studies assessing utility. Early-stage ontology research often focuses on stages 1–2, with stages 3–4 following in subsequent publications. For example, FIBO’s initial publications [14] focused on conceptual design and competency question validation before later work evaluated adoption and impact [28].

Evaluation in Data Quality Frameworks. DQ framework evaluation varies widely in rigor. Batini and Scannapieco [18] distinguish between (1) theoretical frameworks providing conceptual models without implementation, (2) prototypes demonstrating feasibility with small datasets, (3) validated systems with empirical testing on real data, and (4) deployed solutions with longitudinal case studies. The academic literature often presents stages 1–2, while commercial tools report stages 3–4 (though with limited methodological transparency). For instance, Luzzu [16] followed a progression: initial design paper (conceptual framework), implementation paper (prototype with 19 datasets), and adoption study (deployment case studies).

Design Science Evaluation Strategies. Venable et al.’s FEDS framework [25] recommends different evaluation strategies based on artifact maturity and risk. For novel technical designs with high technical risk, artificial evaluation (controlled experiments, synthetic data) should precede naturalistic evaluation (field deployment, real users). For early-stage artifacts, formative evaluation (identifying design improvements) is more appropriate than summative evaluation (proving effectiveness). This staged approach balances scientific rigor with practical constraints—comprehensive evaluation requires access to production systems, user populations, and time that may not be available for initial design publications.

Implications for CEDAR Evaluation. Following these precedents, our evaluation strategy adopts a staged approach: This paper (DSRM Iteration 1) focuses on conceptual design, technical feasibility demonstration, and competency question validation using synthetic data—consistent with early-stage ontology and DQ framework research. Subsequent iterations will progress to large-scale empirical validation, baseline comparisons, and user studies, following the evaluation progression documented in successful ontology-based systems.

Activity 2: Objectives of a Solution (Section 2.2)

- Integrate ontological domain knowledge with event stream processing;

- Enable detection of temporal and context-dependent quality issues;

- Provide business-meaningful explanations for detected anomalies;

- Maintain interoperability through standards-based design.

Activity 3: Design and Development (Section 3.2 and Section 3.3)

- Conceptual framework: Four integrated models (contextualization, event, trend detection, domain);

- Ontological design: Extension of FIBO with event and quality concepts;

- Architecture: Integration of semantic web technologies with big data platforms.

- Motivating example: Equity derivative trading scenario;

- Worked example: Detection of unusual price jump with causal tracing;

- Competency questions: Demonstration of ontological query capabilities.

Activity 5: Evaluation (Section 6)

- Current iteration: Proof-of-concept implementation, controlled validation with synthetic data, competency question testing;

- Future iterations: Large-scale empirical evaluation, baseline comparisons, user studies, deployment case studies (detailed roadmap in Section 2.2).

Activity 6: Communication

- This paper: Design contribution for academic audience;

- Planned: Practitioner-oriented publications, open-source prototype release, workshop presentations.

3.2. Models for Contextualising Temporal Data

3.2.1. Overview

These models are the key component of the framework, where a model represents a repeatable, systematic method that is applied to a dataset to carry out some processing task. An instance of a model type will exist for a specific application. There are four types of models required in the framework:

- A domain model (DM)—the overarching model to represent the business knowledge and semantics used across the framework;

- The trend detection model (TDM)—a model to detect trends (i.e., patterns of interest) for an input dataset guided by the domain model. The TDM is a repository of functions that applies to set of attributes to detect which trends have occurred;

- The event pattern model (EPM)—a model to detect event patterns (i.e., combinations of events that, when related, reflect business semantics). For example, an observed change in an attribute for a data source is a pattern;

- The contextualisation model (CM)—a model to provide business actions based on the derived context of the event pattern model.

These are described in the rest of this section. We will use as an example an application for analysing trading data for equity-based derivatives.

3.2.2. Domain Model

An essential requirement for heterogenous data quality management is defining the taxonomy and business information concepts. The domain model is used to define entities in a specific domain and capture the relationships between these entities, either within a dataset or across datasets, i.e., it defines the semantics of the datasets. The domain model is represented via an ontology that achieves the following:

- Captures known entities, relationships, roles and resources across data sources within a defined scope;

- Uses a standardised, defined taxonomy of entities and their relationships represented as classes and relations;

- Provides axioms to define constraints, dependencies or logical relationships between entities.

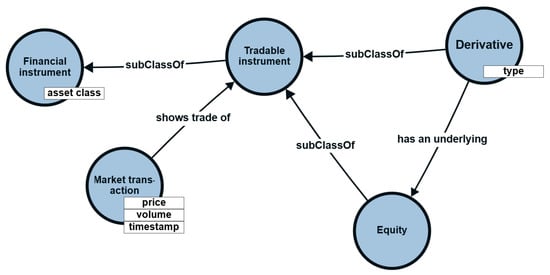

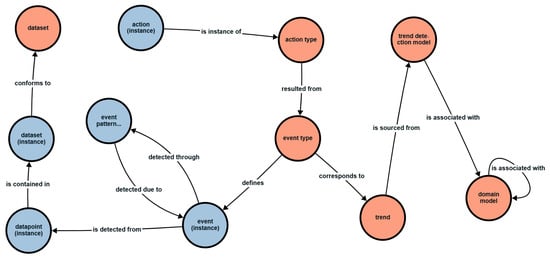

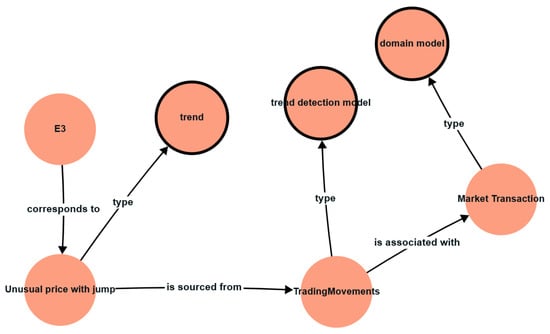

In our example, a domain model would contain known entities and defined relationships between attributes (price and volume) of market transactions for equity-based derivatives and the underlying equities. These attributes would reflect trends in these financial instruments, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example domain model.

3.2.3. Trend Detection Model

The trend detection model is used to detect data of interest using statistical learning methods (e.g., analytics, mathematical/computation models, machine learning). The trend detection model is represented by a series of predicate functions given the specified domain model, where, when applied, may return additional information (e.g., a tag) that can be associated with the data point. Using the running example, a domain expert may have the following expectations:

- Derivatives should only be priced below a defined threshold.

- Derivatives should only see a price difference between two consecutive trading periods within a defined threshold.

A domain expert may then be expected to raise a potential DQ issue if any or both these expectations are not met. Therefore, two trend detection models can be applied to the attributes of the market transactions, detecting unusual/interesting changes in price for equities and derivatives. Example of trends and their functions are shown in Table 3. The last row represents when both conditions are met.

Table 3.

Example trends and their representation; where mt represents a market transaction.

3.2.4. Event Pattern Model

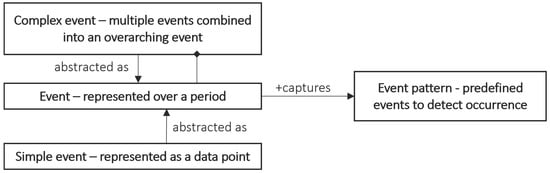

The event pattern model is the primary contribution of this paper as it is the central component that connects the different models in the framework. An event is defined when ‘the action has taken place’. It describes an occurrence that has been captured and integrated into the system, carrying information about the action. In this framework, we adopt an event meta-model that is depicted in Figure 2 [29]. A simple event represents the occurrence of a single action and may be instantaneous or have a duration. A complex event represents a combination of events that, when related, reflect business semantics and are defined by an event pattern.

Figure 2.

Generic event model.

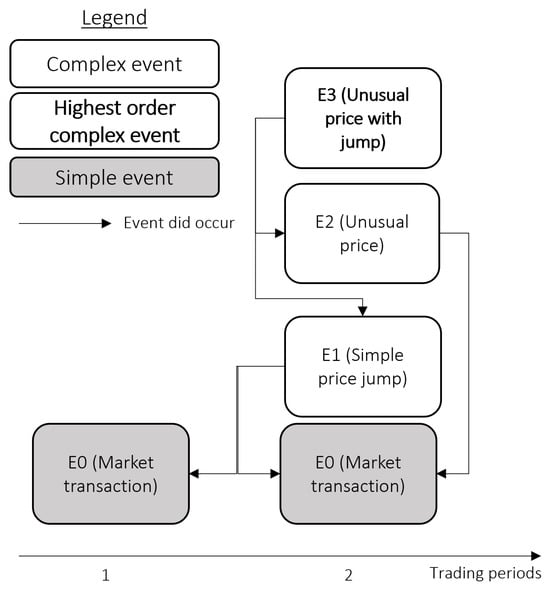

The framework considers the input data as simple events and uses event patterns to define hierarchies of more complex events. Let us continue with the previous example. Trading data, by nature, has a temporal component, and trading patterns in one domain may impact the trading pattern of another. This can be generically defined as an event-based pattern (where one action that has occurred can be linked to another action that has also occurred or is expected to occur). A simple event is the market transaction from the original data source, and a complex event may be a simple price jump, indicated by the occurrence of the respective event pattern. The resulting EPM can be detailed as per Table 4.

Table 4.

Event and event pattern types.

The highest order in the event pattern hierarchy would signify when the event model output is ready for business interpretation. In our example, a user wants to observe event-based patterns across related financial trades. Deviations from typical trading patterns can be detected and potentially described by the existence (or lack) of related changes. As a domain expert, the user has an expectation of the usual price/volume, data movements between transaction periods and understands the impact the relationship between equities and derivatives will have on trading volumes/prices. Based on checking for several trends, the domain expert can specify two types of events for derivative transactions:

- The observed trading price of the derivative is not within expected thresholds. Therefore, the domain expert would label this event as unusual price.

- The observed trading price jump across consecutive trading periods of the derivative is unusual and moves outside expectation. Therefore, the domain expert would label this context as a ‘simple price jump’.

Figure 3.

Event hierarchy.

The events (both simple and complex) are defined by the roles and properties of entities and their attributes from the domain model and overlayed with appropriate thresholds determined by subject matter experts in the trend detection model.

3.2.5. Contextualisation Model

The contextualisation model is the overarching model to determine the actions required by a business user. The CM takes on defined complex events based on the event hierarchy that would require business intervention. The business context is then represented as an action associated with the dataset, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

CM example.

In our example, the business user may consider a dataset to require further action when unusual trading has been detected. Using the event hierarchy, this is represented by E3 which is defined as a business outcome in the CM. Therefore, action A1, or raise a DQ, from the CM would need to be taken by the business user.

3.2.6. Sample Application

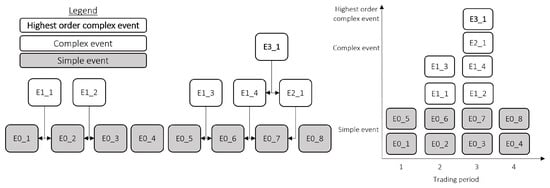

In this section, the running example will be expanded to demonstrate the application of the models. Consider the trading ledger shown in Table 6, showing aggregated volumes and price per unit for trades for fictious equity ‘ABC’ at 30 min intervals as well as its equity-based derivative. Each row is a data point, representing the occurrence of an action, and can therefore be categorised as simple event of event type market transaction (E0 in the event model).

Table 6.

Trading log.

Using the event model specified in Table 4 and the event hierarchy in Figure 3, several complex events can be detected based on the event pattern occurrence as show in Table 7 and visualised in Figure 4. The resulting context, based on the CM (from Table 5) leads to an instance of A1; that is, a business user should raise a DQ issue for the specified trading log.

Table 7.

Sample of events detected and the related event pattern occurrences.

Figure 4.

Example of EPM application; Left: hierarchy of events detected; Right: events detected per time period.

3.3. Knowledge Base Design

A second component of the framework to support the application of the models from Section 3.2 is the knowledge base. The terminology and its application used are derived from the RM-ODP standard [30] and extended into the context of event patterns via concepts presented in [31,32]. Other use cases include big data frameworks pertaining to DQ management and semantic models [33,34,35,36,37].

The key purpose of the knowledge base is to provide visibility and transparency to end-users as to how context was derived by the framework. These objectives are supported through the development of an ontology to be used in the knowledge base. The objectives are as follows:

- Allowing users to track an instance through the framework’s application and investigate how the framework was applied and relate model outputs to their inputs;

- Allowing users to understand the framework’s models and how information is related across the models.

The ontology was developed using the methodology outlined in [38]. The specified approach was a bottom-up approach to address a series of defined competency questions to meet the knowledge base objectives. Utilising the bottom- up approach, the ontology should be able to answer the example competency questions in Table 8 for the example in Section 3.2.6, and more generally, the generic competency questions that can be extrapolated.

Table 8.

Example competency questions.

3.3.1. Defining the Key Classes

To draw out the required classes and attributes of the ontology, the example competency questions in Table 8 can be abstracted as per Table 9.

Table 9.

Generic competency questions: where entities/attributes are shown in brackets.

As a result, the entities of the ontology are defined in Table 10. From the competency questions, two parent classes can be defined:

Table 10.

Knowledge base classes.

- Reference–representing generalised information that defines expected behaviour and attributes of instances;

- Instance–representing specific realisations of a reference entity.

3.3.2. The Ontology Framework and Logical Relationships

The CEDAR ontology is built on the following key logical predicates and relationships in Table 11. This presents the logical content and semantic justification for each relationship axiom in our ontology. These axioms establish the foundational constraints and dependencies that govern how concepts interact within the framework. Each relationship represents not merely a structural connection but a logical assertion about the necessary dependencies and semantic meanings that underpin visual analysis of software engineering data.

Table 11.

Logical content and semantic meaning of relationship axioms.

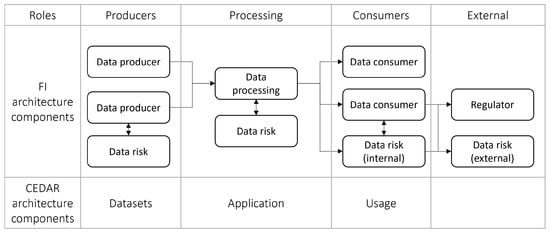

The resulting ontology is shown in Figure 5. The central component is the event type entity, linking the actions, trends and events in the datasets. The event type entity is used to define instances of the event (i.e., the event (instance) entity). Instances are detected through event pattern occurrence (instance), which, in turn, uses event instance(s) and datapoint instance(s) to determine if an event pattern has occurred. Datapoints are contained within a dataset (instance), conforming to the types of datasets defined in the dataset entity.

Figure 5.

CEDAR framework ontology; parent class = reference in orange, parent class = instance in blue.

An event type is also used to link to an action type, where the action type entity includes the event type that would trigger the action. Instances of the action types are captured in the action (instance) entity. An event type is defined as per a trend, which is sourced from the trend detection model. The TDM is associated with the domain model entity, which also has a reflexive relationship defined to capture related domains.

This design integrates the subcomponents of the knowledge base to allow the framework to be applied to the dataset in question. The user can understand the derived context and resulting action through the ontology and how the framework and its models have been applied.

3.3.3. Transforming Raw Data for the Ontology

CEDAR’s data transformation pipeline converts operational data into queryable Resource Description Framework (RDF) through five stages. Extraction captures heterogeneous data (logs, feeds, reference data) from source systems. Transformation performs semantic enrichment by computing contextual attributes that enable quality assessment—price changes relative to historical values, time intervals between events, and derived metrics representing business patterns. Semantic mapping applies formal specifications defining correspondences between source data and ontology concepts: determining RDF class instantiation (e.g., mapping instrument type to cedar:DerivativeTradeEvent) and property assertions (e.g., trade id to cedar:hasTradeID). This mapping embodies domain expertise validated by experts to ensure accurate conceptual alignment. Serialization generates RDF triples expressing type assertions, data properties, object relationships, and provenance metadata. Loading and reasoning ingests triples where ontological inference derives implicit knowledge through transitive relationships and class hierarchies—transforming data points into semantically interconnected knowledge where business rules can be evaluated.

This design ensures scalability through separation of concerns (data-intensive transformations separated from semantic reasoning), timeliness through incremental processing enabling near-real-time assessment, and accuracy through formal mapping specifications that codify domain knowledge explicitly and maintain provenance tracking. The bidirectional pipeline is noteworthy: operational data populates ontology instances while ontological constraints derive quality rules, creating a feedback loop where encoded business knowledge governs how data are interpreted for quality assessment.

4. CEDAR System Architecture

This section details how the CEDAR framework will be integrated into an existing FI architecture and be used by data consumers to contextualise data.

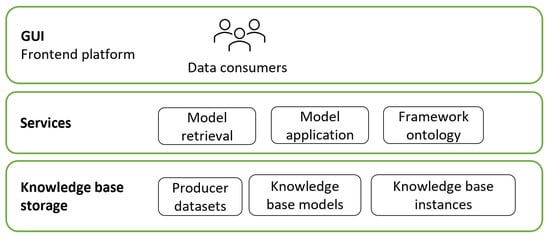

4.1. CEDAR System Boundaries and Context

Based on Section 2, we assume an FI data architecture that follows up a bow-tie mechanism, from data production, to processing to consumption. The target users of the framework include data consumers and data roles aligned with the use of data within the enterprise, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Framework architecture combined with typical FI architecture. Arrows represent the flow of data.

There are three key use cases of CEDAR. They are as follows:

- UC1—Implementing the framework’s components (models) and defining their interactions (in the knowledge base): this role is assumed by a knowledge engineer persona;

- UC2—Executing the framework on an ongoing basis: this role is assumed by a data operations persona;

- UC3—Analysing the outcome of the framework: this role is assumed by a data consumer persona.

4.2. CEDAR Architectural Layers

The CEDAR application architecture will have three layers, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

CEDAR application architecture.

Each layer is defined as follows:

- Graphical user interface (GUI) layer: this layer allows consumers (data consumers and data risk personnel) to understand context that has been added to their data before usage and explore the framework and instances of its application.

- Services: This layer is responsible for retrieving and applying the appropriate models. It also populates the ontology used to support framework transparency and user exploration. The ontology is populated from two different key sources: reference entities by domain experts, and instance entities by the datasets from the framework application.

- Knowledge base components: this layer contains the datasets and models used by the framework, as well as instances of the framework application.

This architecture is designed to facilitate the CEDAR framework’s application in different FI environments. The three core services required in CEDAR are as follows:

- Model Retrieval—which acts as the access layer to the Knowledge Base;

- Model Application—which orchestrates the execution of models on datasets;

- Framework Ontology Management—which maintains the structural organization of framework components.

The knowledge base itself comprises three components:

- Producer Datasets—which represent the input data sources;

- Knowledge Base Models—which contain the reusable structured artifacts that define processing logic;

- Knowledge Base Instances—which store the outputs generated from applying models to datasets.

4.3. Use Cases and Sequence Diagrams

We will now explore how the use cases defined in Section 4.1 are implemented by the framework’s architecture. For these use cases, each service’s contribution to the workflows is defined in Table 12, and each knowledge base component’s contribution is defined in Table 13.

Table 12.

Service definitions.

Table 13.

Knowledge base components.

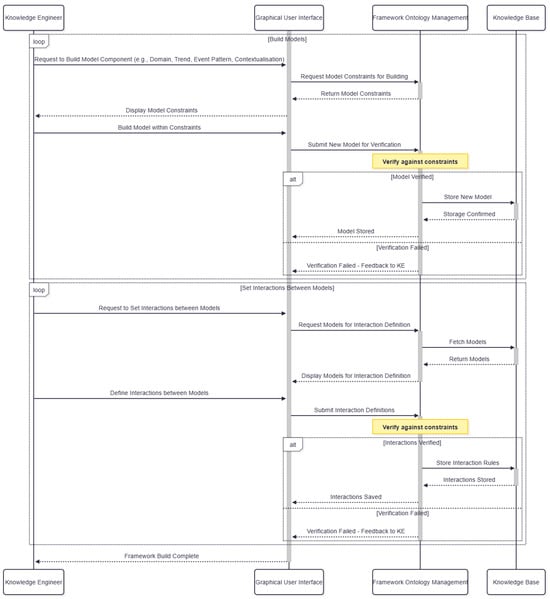

4.3.1. UC1—Implementing the Framework

Use case 1 focuses on how the framework in implemented initially within an FI’s architecture. This is shown in Figure 8. The knowledge engineer would start with using the GUI to build a model component of the framework. This would query the framework ontology management service return the model constraints that the knowledge engineer would then build within. For example, the knowledge engineer starts with wanting to define the domain model. The framework ontology management service would return the format for the knowledge engineer to define the domain model in, which would be the form of entities and relationships with defined attributes. If the knowledge engineer builds outside these constrains, the framework ontology management service would fail the verification and provide feedback to the knowledge engineer to resolve. If the model has been built within the defined constraints, it will be stored in the knowledge base. The knowledge engineer can then loop through this process to build more models for the framework, moving from the domain model to the trend detection model to the event pattern model to the contextualisation model. The knowledge engineer also needs to define the interactions between models, specifying how which models can be used together to ensure compatibility.

Figure 8.

CEDAR framework sequence diagram for implementing the framework in an FI’s architecture.

When defining the trend detection model, the knowledge engineer would convert business context into trends for the trend detection model and set which domain model is linked to which trend model. This will then be verified by the framework ontology management service and provide feedback to the engineer. The knowledge engineer would then abstract the trends into events to create the event pattern model, and set interactions between trends and event types. As part of the event pattern model, the event hierarchy would also be defined. The events (both simple and complex) would be defined by the roles and properties of entities and their attributes from the domain model, and overlaid with appropriate thresholds through the trend detection model, and informed by business experts. The final model for the knowledge engineer to configure would be the contextualisation model. Using the event hierarchy, the knowledge engineer would set the interactions between the event pattern model and event hierarchy to the contextualisation model.

Each of these models, once configured, would be stored in the knowledge base and their interactions defined in the framework ontology management service for use in the next use case.

4.3.2. UC2—Executing the Framework

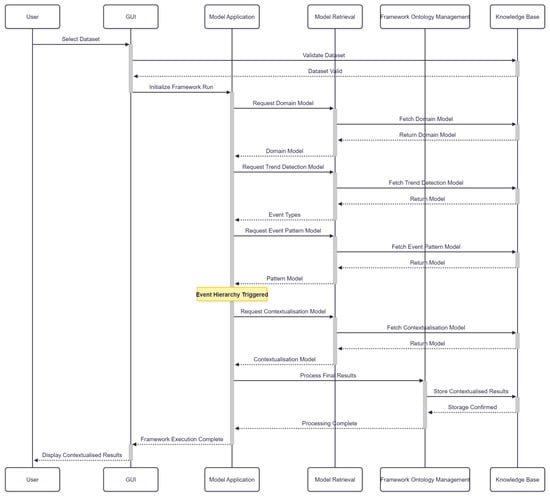

Use case 2 focuses on how the framework is executed. This is shown in Figure 9. The data operations persona is required to execute the framework against a chosen dataset. The dataset will be validated and added to the knowledge base, before initialising a run of the framework. As defined by the knowledge engineer’s implementation in use case 1, the framework will look to apply the domain model first, and therefore retrieve the domain model pertaining to this dataset from the knowledge base. This will then be returned to the model retrieval service and sent back to the model application service. Based on this, and replicating the same sequence, the domain model will lead to the application of the trend detection model, which in turn will lead to the the application of the event pattern model. The event pattern model will be applied until the event hierarchy is triggered.

Figure 9.

CEDAR framework sequence diagram for executing the framework on producer dataset.

If the highest order complex event in the event hierarchy is found, the final model to be applied is the contextualisation model. This is requested by the model application service, and retrieved from the knowledge base by the model retrieval service. The model is then applied and the final result (i.e., context based on the CM) is taken from the defined model from the knowledge engineer. This final results are processed to comply based on framework ontology management service and stored in the knowledge base. Once stored, framework execution has completed. The data operations persona then sees the contextualised results on the GUI and is ready to share with the data consumer persona for use case 3.

4.3.3. UC3—Analysing the Framework Outcomes

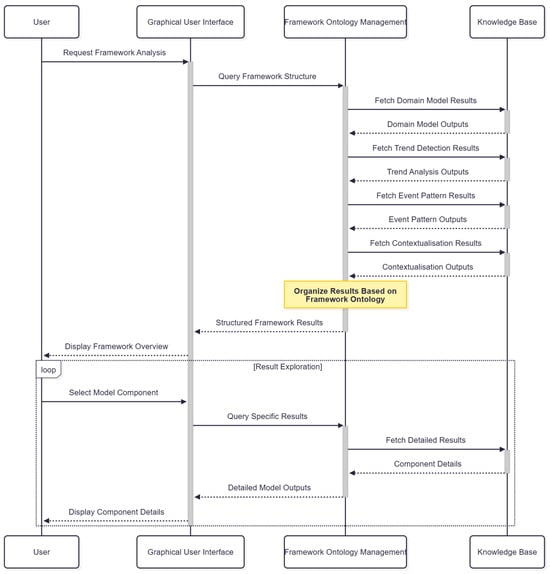

Use case 3 focuses on how the framework outcomes are analysed. This is shown in Figure 10. The data consumer persona is interested in understanding the context provided and how the context was derived, as per Table 9. The user, via the GUI, requests to analysis an execution of the framework for the specific dataset. This leads to a query of the framework structure to the framework ontology management service. This fetches the output for each of the applied models from the knowledge base and organises the results based on the framework ontology. The structured framework results are returned to the user on the GUI.

Figure 10.

CEDAR framework sequence diagram for analysing the outcome of the framework application.

The data consumer persona can now explore the results by selected components via the GUI. This will query the framework ontology management service to fetch detailed results from the knowledge base and return the output to the user. This will allow the data consumer to explore across the framework’s execution for the producer dataset and analyse the outcome.

5. Implementation

5.1. Prototype

The current prototype to implement the framework has utilised broker trading data sourced from the Securities Industry Research Centre of Asia-Pacific (SIRCA) and the Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO), and follows the example used in Section 3.2.6. As the initial prototype, the implementation has focused on the model development and application time-based data across related datasets.

We will focus on two scenarios defined in use case 3 as the key indicator of successful implementation. The following stack is used to demonstrate the case study:

- CEDAR GUI—Stardog.

- CEDAR Knowledge Base storage:

- −

- Producer datasets—Stardog;

- −

- Knowledge base models—Python 3.14;

- −

- Knowledge base instances—Stardog.

- CEDAR services:

- −

- Model retrieval—Python;

- −

- Model application—Python;

- −

- Framework Ontology Management—Stardog.

5.2. Scenario 1: Anomaly Detection Knowledge Building

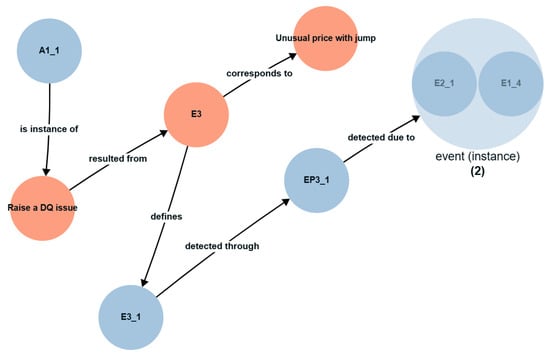

The first scenario evaluated is the detection of anomalous data, representing a potential DQ issue for a business user to raise. In this implementation, an unusual price with jump would represent such an anomaly. The CEDAR framework is applied to the derivatives dataset. Using the Stardog Explore interface, the application of the contextualisation model and event model are shown via Figure 11 or as a series of tuples via Table 14. Similarly, the application of the event model, trend detection model and domain model are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Contextualisation and event model. Parent class = reference in orange, parent class = instance in blue.

Table 14.

Contextualisation and event model output.

Figure 12.

Event, trend detection and domain model application.

5.3. Scenario 2: Anomaly Exploration

The second scenario evaluated is the framework users ability to self-service their use of the framework. To evaluate the prototype in the persona of a business user, the Stardog Explore GUI will be used to demonstrate outputs of the models and understand the framework application. As the framework ontology is the basis for business users to understand the framework, evaluation will focus on this ontology against the competency questions in Table 9, using the output data produced by the implementation in Section 5.1.

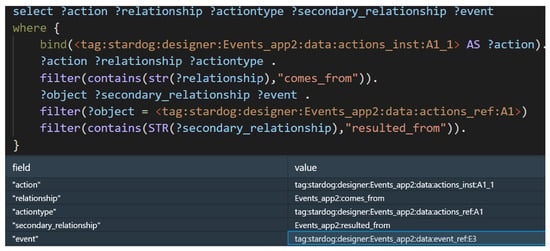

For example, competency question 1 stated the following: Why does a business user need to complete an [action instance]? Using the knowledge base instance and the framework ontology, we can start by querying which action instances were found (A1_1), what the reference action would be (A1), and then which event needs to occur for this action to be required (E3). This query, and output can be shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Evaluation of competency question 1.

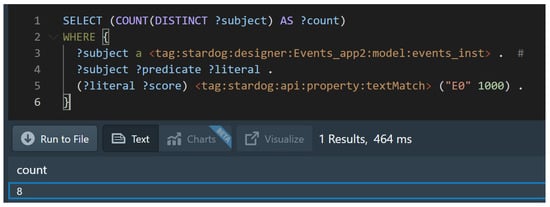

Similarly, we can evaluate another competency question: How many times [event instance] occured? Using market transaction (E0) as an example, we can count how many event instances of E0 occurred. This query, and the output can be show in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Evaluation of competency question 6.

6. Discussion

This section interprets the validation findings, explores their significance and implications, positions results within the broader literature, and acknowledges limitations that contextualize the contribution’s scope.

6.1. Interpretation of Findings

This DSRM iteration focused on establishing technical feasibility for addressing the research questions: Can contextual information from event streams be integrated with ontological knowledge to identify context-dependent DQ issues (RQ1), and can ontology-based DQ assessment be operationalized in event-driven FI architectures (RQ2)?

Following the evaluation framework established in Section 2.2, we assess CEDAR against three key criteria from Table 2:

6.1.1. Criterion 1: Identification and Representation of Context-Dependent DQ Issues

Finding: The prototype successfully detected the unusual price jump anomaly by integrating temporal context with domain knowledge. This demonstrates advancement over traditional DQ methods and commercial tools that show “minimal” capability for context-dependent issues [7].

Significance: Unlike rule-based systems that detect violations of isolated constraints (e.g., “price is negative”), CEDAR identified an anomaly whose validity depends on temporal and domain context. The contextualization model enabled assessment of the derivative price change relative to the underlying equity’s behavior, addressing the challenge identified by Wang and Strong [3] that data quality is inherently context-dependent and user-specific.

Comparison to Alternatives: Supervised anomaly detection methods (Solution 2 in Table 2) require continuous human labeling and struggle with evolving contexts [9]. Unsupervised methods (Solution 3) lack interpretability—a limitation Nedelkoski et al. [39] quantified at 43% false positives in financial services due to missing domain context. CEDAR’s ontology-grounded approach provides both contextual awareness and interpretability, though at the cost of requiring explicit rule definition.

Relation to Literature: This finding extends Schneider’s [12] observation that ontologies are valuable additions to DQ management toolkits by demonstrating how ontologies can operationalize contextual assessment. While Debattista et al.’s Luzzu framework [40] applies ontologies to assess knowledge graph quality, CEDAR extends this to operational event streams—addressing Färber et al.’s [41] finding that 37% of quality issues in financial knowledge graphs are temporal and missed by static assessment.

6.1.2. Criterion 2: Scalability and Maintainability (Preliminary Assessment)

Finding: The prototype processed synthetic transactions with query response times under 200 ms. Rule addition requires ontology updates (estimated less than 1 day per new rule based on implementation experience) rather than coding in multiple systems.

Preliminary Interpretation: This suggests potential advantages over traditional methods where Loshin [42] documented 60–70% of effort spent maintaining rules across systems. However, with only minimal transactions, scalability claims are premature. The use of standards-based technologies (OWL, SPARQL, Spark) provides a foundation for scale, but performance at production volumes (millions of events) requires validation in DSRM Iteration 2.

Comparison to Alternatives: Commercial tools (Solution 4 in Table 2) offer proven scalability but with “high cost and low flexibility” due to vendor lock-in. CEDAR’s open standards approach trades proven performance for flexibility and interoperability—a trade-off that requires empirical validation to determine if the flexibility benefits outweigh potential performance costs.

Architectural Implications: CEDAR’s design aligns with FI trends toward centralized data management [1] while supporting the bow-tie architecture pattern [11] through semantic integration. The separation of computational models from semantic models enables independent scaling, though integration overhead needs measurement.

6.1.3. Criterion 3: Transparency to Data Consumers

Finding: Competency question validation demonstrated that the ontology enables querying from action (“Why must I raise this issue?”) to root cause (“Which market event triggered this?”) through semantic relationships. All competency questions were answerable via SPARQL or visual graph exploration.

Significance: This addresses a key limitation in existing approaches. Traditional DQ tools provide technical error codes; ML-based anomaly detection offers statistical scores; both lack business-meaningful explanations. CEDAR’s causal tracing capability—linking detected anomalies through event chains to violated business constraints—provides the “transparency to data consumers” that Munar et al. [10] identified as critical in complex FI architectures where data consumers lack visibility into upstream processing.

Important Caveat: Technical capability to answer questions does not validate actual usability for business users. Our validation used competency questions defined by researchers and executed by technical users. Whether data quality analysts and compliance officers can effectively use Stardog Explorer or formulate SPARQL queries requires user studies. The gap between technical capability and user utility is well-documented in ontology research [27].

Comparison to Alternatives: Solutions 2 and 3 (supervised/unsupervised anomaly detection) are “limited due to technical nature of implementation” [9]. CEDAR aims to bridge technical detection with business interpretation through ontological representation, but this bridge’s effectiveness for non-technical users remains unvalidated.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.2.1. For Data Quality Management Theory

CEDAR extends DQ management theory in three ways. First, it operationalizes the concept of semantic data quality—assessing quality not just against structural constraints but against rich domain knowledge encoded in ontologies. This addresses Wang and Strong’s [3] foundational observation that quality is fitness-for-use and context-dependent, providing a technical mechanism for representing and reasoning about context.

Second, it bridges the gap between static DQ frameworks [5,18] and dynamic event-driven environments. Existing frameworks assess quality at specific lifecycle points; CEDAR assesses quality across temporal event sequences, addressing Elouataoui et al.’s [2] critique that frameworks focus on specific lifecycle points rather than holistic management.

Third, it demonstrates that ontology-based approaches can address the context-dependency limitations that Zhang et al. [7] identified in automated DQ assessment—though our validation is too limited to claim this definitively.

6.2.2. For Ontology Application Research

This work contributes to ontology engineering practice by demonstrating how ontologies can move beyond static knowledge representation to drive operational processes. The bidirectional enrichment pattern—events populating the ontology, ontology enriching events—provides a model for integrating ontologies into dynamic systems, addressing a gap in ontology application literature that primarily focuses on static knowledge bases.

The extension of FIBO with event and quality concepts provides a reference model for operational financial ontology applications, complementing existing work on FIBO’s use for semantic consistency [14] and regulatory compliance [15].

6.2.3. For Financial Technology Research

CEDAR demonstrates practical application of semantic web standards in financial institutions—an industry traditionally resistant to academic technologies due to regulatory, security, and performance constraints. The successful integration with enterprise technologies (Databricks, Stardog) provides evidence that W3C standards can coexist with commercial platforms in regulated environments, addressing a barrier to semantic web adoption in finance.

6.3. Practical Implications

6.3.1. For Data Quality Practitioners

If validated at scale, CEDAR could offer several benefits:

Reduced Manual Effort: Ontological rule abstraction could reduce the 60–70% of time Loshin [42] found organizations spend maintaining rules. Rules defined once in the ontology automatically apply to related instruments through class inheritance.

Improved Root Cause Analysis: Automated causal tracing could reduce the 2–5 days domain experts in our partner institutions reported spending investigating cross-system DQ issues. However, these potential benefits require validation through user studies and deployment.

Enhanced Regulatory Alignment: Explicit constraint documentation in ontologies provides audit trails linking quality checks to regulatory requirements (e.g., MiFID II, Basel III)—addressing supervisor demands for data lineage transparency [21].

Adoption Barriers: Realizing these benefits requires: (1) skilled ontology engineers to create and maintain OWL ontologies, (2) organizational commitment to semantic approaches, (3) integration with existing DQ toolchains, and (4) training for business users. These barriers may limit adoption to larger FIs with mature data governance programs.

6.3.2. For Financial Institutions

CEDAR aligns with regulatory trends toward standardization and interoperability. The Bank for International Settlements’ vision for globally standardized data infrastructure [20] and domestic regulators’ focus on data lineage [21] suggest ontology-based approaches may become necessary rather than optional. Early adoption could provide competitive advantages in regulatory reporting efficiency and data risk management.

However, production deployment requires addressing: (1) performance at scale (billions of daily transactions), (2) integration with legacy systems, (3) governance of ontology evolution, and (4) cybersecurity for semantic technologies—all identified as future work requiring substantial investment.

6.3.3. For Technology Vendors

CEDAR’s standards-based design provides a blueprint for next-generation DQ tools. Commercial vendors could adopt the ontology-event integration pattern while leveraging their existing optimization, UI, and support capabilities. The framework is intentionally complementary to existing tools (e.g., consuming Informatica alerts and adding semantic interpretation) rather than a complete replacement, suggesting partnership opportunities.

6.4. Limitations

6.4.1. Validation Scope Limitations

Scale: Validation used only synthetic transactions—smaller than production FI environments processing millions of daily transactions. The perfect detection accuracy (precision = recall = 1.0) likely reflects the simplicity of the test case rather than real-world robustness.

Data Characteristics: Synthetic data with known ground truth eliminates confounding factors but does not represent real-world complexity: missing values, inconsistent formats, network latency, concurrent transactions, system errors. Real data will introduce edge cases and noise that may reveal design flaws not apparent in controlled tests.

Anomaly Diversity: Testing a single anomaly type (price jumps) does not validate generalization to the diverse quality issues FIs encounter: completeness violations, consistency errors, referential integrity failures, temporal sequence violations, regulatory constraint breaches. Each may require different detection approaches and ontological modeling patterns.

Domain Scope: The equity derivative scenario does not validate applicability to other financial instruments (fixed income, foreign exchange, commodities) or processes (risk aggregation, collateral management, regulatory reporting). While the models are designed generically, actual generalization requires empirical validation.

6.4.2. Evaluation Methodology Limitations

User Validation: Competency question validation demonstrates technical capability but not actual usability. We do not know if data quality analysts can effectively use Stardog Explorer, understand ontological representations, or trust system recommendations. User utility—the ultimate measure of success for a tool targeting business users—remains will be required in future work.

Longitudinal Assessment: Short-term technical validation does not reveal issues that emerge over time: rule maintenance burden as business logic evolves, ontology drift as concepts change, performance degradation as data accumulates, user adoption patterns. This also requires user validation.

Organizational Context: Laboratory validation ignores organizational factors critical to adoption: integration with existing workflows, training requirements, change management, political dynamics, budget constraints. This also requires user validation.

6.4.3. Technical Design Limitations

Ontology Maintenance Complexity: Creating and maintaining OWL ontologies requires specialized expertise that may not be available in all FIs. While we documented less than 1 day per new rule based on implementation experience, this assumes skilled ontology engineers—actual effort for typical data quality teams may be higher.

Rule-Based Detection Limitations: This iteration did not cover anomaly detection without ontology updates, unlike ML approaches that adapt automatically. Future iterations will focus on this, to reduce dependency on domain experts to anticipate and encode all relevant quality patterns—potentially missing emergent issues.

6.4.4. Threats to Validity Summary

Following Runeson and Höst’s [43] case study methodology taxonomy, the following can be determined:

Internal Validity: Synthetic data and controlled environment eliminate confounding factors but may not represent real-world causal relationships. Single anomaly type tested limits ability to infer general detection capability.

External Validity: Results from synthetic transactions in one scenario cannot be generalized to production environments, diverse instruments, or other FIs without replication studies.

Construct Validity: Measuring technical capability (competency question answerability) does not validate the construct of interest (user utility). This must be validated by a future user study.

Reliability: Detailed documentation of models, implementation, and validation procedures supports replication. However, dependencies on specific technologies and expert knowledge may limit reproducibility by other researchers.

6.5. Future Research Directions

The limitations above inform a structured research agenda across three DSRM iterations:

Iteration 2 (Technical Validation): Address scale, diversity, and comparison limitations through: 100,000+ real SIRCA transactions, 15–20 diverse anomaly types, statistical validation with significance testing, and performance profiling to identify bottlenecks.

Iteration 3 (User Validation): Address usability and utility limitations through: recruitment of FI practitioners (data quality analysts, compliance officers, data stewards), task-based usability studies measuring completion time and accuracy, system usability measurement, and qualitative interviews exploring perceived usefulness and adoption barriers.

Beyond CEDAR-specific validation, this work opens broader research questions: How should ontologies be governed in large organizations? What makes a “good” explanation for DQ issues? How to build appropriate user trust in ontology-driven systems? These questions extend to semantic systems and explainable AI generally.

6.6. Positioning Within Design Science Research

This paper represents an early-stage DSRM contribution focused on establishing design novelty and technical feasibility before comprehensive evaluation. This positioning is methodologically appropriate: attempting large-scale evaluation or user studies before confirming basic technical viability risks wasting resources on fundamentally flawed designs.

Following March and Smith’s [44] taxonomy, we have delivered a “construct” and “model” contribution (conceptual framework) with “instantiation” (working prototype) at the “proof-of-concept” stage. This is distinct from “proof-of-value” that requires comprehensive empirical evaluation demonstrating superiority over alternatives—the target of future iterations.

As Hevner [26] notes: “The rigor and completeness of design evaluation should be appropriate for the maturity and importance of the artifact.” For an initial design iteration, controlled artificial evaluation is appropriate; for production deployment decisions, naturalistic summative evaluation would be required.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents CEDAR, a novel framework integrating ontological domain knowledge with event-driven data quality management for financial institutions. Following Design Science Research Methodology’s first iteration, we establish CEDAR’s design novelty and technical feasibility. CEDAR advances the state of the art through four innovations: (1) ontology-driven rule derivation automating constraint translation into detection logic, (2) temporal ontological reasoning extending static quality assessment with event dynamics, (3) explainable assessment through causal tracing, and (4) standards-based architecture using W3C technologies with FIBO. Comparative analysis demonstrates CEDAR addresses gaps at the intersection of rule-based DQ tools, log-based anomaly detection, knowledge graph quality frameworks, and CEP systems.

Controlled validation with synthetic equity derivative data confirms that CEDAR’s integrated models successfully detect context-dependent anomalies, trace causal chains, and support ontological exploration, answering both research questions on integrating contextual events with ontological knowledge and operationalizing ontology-based DQ assessment in event-driven architectures. While an early-stage prototype, it provides direction for future iterations that cover more complex models and integration, that can be comprehensively evaluated. This work demonstrates how semantic web technologies address operational DQ challenges in financial institutions, contributing to both theory and practice. As regulators demand standardization and data lineage transparency, ontology-based approaches like CEDAR may become essential infrastructure for modern financial data management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and F.R.; methodology, A.T. and F.R.; software, A.T. and F.R.; validation, A.T. and F.R.; formal analysis, A.T. and F.R.; investigation, A.T. and F.R.; resources, A.T. and F.R.; data curation, A.T. and F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T. and F.R.; writing—review and editing, A.T. and F.R.; visualization, A.T. and F.R.; supervision, F.R.; project administration, A.T. and F.R.; funding acquisition, F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this research can be made available by the corresponding author following a justified request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GFC | Global Financial Crisis |

| CEDAR | Contextual Events and Domain-driven Associative Representation |

| DQ | Data Quality |

| FI | Financial institution |

| FIs | Financial institutions |

| FIBO | Financial Industry Business Ontology |

| DQO | Data Quality Ontology |

| DQAM | Data QUality Assessment Methodology |

| TDWM | Total Data Quality Management |

| DM | Domain Model |

| TDM | Trend Detection Model |

| EPM | Event Pattern Model |

| CM | Contextualisation Model |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

References

- Cao, S.; Iansiti, M. Organizational Barriers to Transforming Large Finance Corporations: Cloud Adoption and the Importance of Technological Architecture; Working Paper 10142; CESifo: Munich, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elouataoui, W.; Alaoui, I.E.; Gahi, Y. Data Quality in the Era of Big Data: A Global Review. In Big Data: A Game Changer for Insurance Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Strong, D.M. Beyond Accuracy: What Data Quality Means to Data Consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1996, 12, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arolfo, F.; Vaisman, A. Data Quality in a Big Data Context. In Big Data: Concepts, Warehousing, and Analytics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichy, C.; Rass, S. An overview of data quality frameworks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 24634–24648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Singh, A. Improving Data Quality using Big Data Framework: A Proposed Approach. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1022, 012092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xiong, F.; Gao, J.; Wang, J. Data quality in big data processing: Issues, solutions and open problems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computed, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–8 August 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collibra. Collibra Data Quality & Observability. 2023. Available online: https://www.collibra.com/us/en/products/data-quality-and-observability (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Thudumu, S.; Branch, P.; Jin, J.; Singh, J.J. A comprehensive survey of anomaly detection techniques for high dimensional big data. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.; Chiner, E.; Sales, I. A Big Data Financial Information Management Architecture for Global Banking. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud, Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 August 2014; pp. 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, K.; Bundi, N.; Heitz, J.; Breymann, W. Scalable architecture for Big Data financial analytics: User-defined functions vs. SQL. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Šimkus, M. Ontologies and Data Management: A Brief Survey. KI–Künstl. Intell. 2020, 34, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FINOS. FINOS, Fintech Open Source Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://www.finos.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Bennett, M. The financial industry business ontology: Best practice for big data. J. Bank. Regul. 2013, 14, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman-Tubb, N.F.; Krause, P. An ontology for Basel III capital requirements. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS), Funchal, Portugal, 21–24 March 2018; SCITEPRESS: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018; pp. 556–563. [Google Scholar]

- Debattista, J.; Auer, S.; Lange, C. daQ, an ontology for dataset quality information. In Proceedings of the LDOW@ WWW, Montreal, QC, Canada, 12 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zaveri, A.; Rula, A.; Maurino, A.; Pietrobon, R.; Lehmann, J.; Auer, S. Quality assessment for linked data: A survey. Semant. Web 2016, 7, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Scannapieco, M. Data and Information Quality: Dimensions, Principles and Techniques; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stardog Union. Stardog: The Enterprise Knowledge Graph Platform. 2023. Available online: https://www.stardog.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Colangelo, A.; Israël, J.M. How Integrated Reporting by Banks May Foster Sustainable Finance? Technical Report; European Central Bank: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, A.; Broadbent, B.; Woods, S. Transforming Data Collection from the UK Financial Sector; Technical Report; Bank of England: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vom Brocke, J.; Winter, R.; Hevner, A.; Maedche, A. Design principles. In Design Science Research. Cases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hevner, A.R.; March, S.T.; Park, J.; Ram, S. Design science in information systems research. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, J.; Pries-Heje, J.; Baskerville, R. FEDS: A framework for evaluation in design science research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.R. A three cycle view of design science research. Scand. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 19, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brank, J.; Grobelnik, M.; Mladenić, D. A survey of ontology evaluation techniques. In Proceedings of the Conference on Data Mining and Data Warehouses (SiKDD 2005), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 17 October 2005; pp. 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.; Cray, S.; Hale, E.; Kendall, E. FIBO ontology: Adoption and application in the financial industry. In Proceedings of the ISWC (Posters/Demos/Industry), Online, 1–6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic, Z.; Berry, A.; Chen, W.; Rabhi, F.A. An Event-Based Model to Support Distributed Real-Time Analytics: Finance Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 19th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 21–25 September 2015; pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-T Rec. X.902|ISO/IEC 10746-2; Information Technology–Open Distributed Processing–Reference Model: Foundations. Recommendation X.902. International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Etzion, O.; Niblett, P. Event Processing in Action; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luckham, D. The power of events: An introduction to complex event processing in distributed enterprise systems. In Rule Representation, Interchange and Reasoning on the Web, Proceedings of the International Symposium, RuleML 2008, Orlando, FL, USA, 30–31 October 2008; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5321, p. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-González, C.; Caballero, I.; Varela-Vaca, Á.J.; Cruz-Lemus, J.A.; Gómez-López, M.T.; Navas-Delgado, I. BIGOWL4DQ: Ontology-driven approach for Big Data quality meta-modelling, selection and reasoning. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2024, 167, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Hidalgo, A.; Barba-González, C.; García-Nieto, J.; Gutiérrez-Moncayo, P.; Paneque, M.; Nebro, A.J.; Roldán-García, M.d.M.; Aldana-Montes, J.F.; Navas-Delgado, I. TITAN: A knowledge-based platform for Big Data workflow management. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 232, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; He, H.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, H. Scene-based big data quality management framework. In Data Science, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Pioneering Computer Scientists, Engineers and Educators, ICPCSEE 2018, Zhengzhou, China, 21–23 September 2018; Communications in Computer and Information Science. Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 901, pp. 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Qi, Y.; Wu, T.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Yuan, C.; Huang, Y. SparkDQ: Efficient generic big data quality management on distributed data-parallel computation. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2021, 156, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneque, M.; Roldán-García, M.d.M.; Blanco, C.; Maté, A.; Rosado, D.G.; Trujillo, J. An ontology-based secure design framework for graph-based databases. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2024, 88, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, N.F.; McGuinness, D.L. Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology; Technical Report KSL-01-05; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelkoski, S.; Bogatinovski, J.; Acker, A.; Cardoso, J.; Kao, O. Anomaly detection from system tracing data using multimodal deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 13th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), Milan, Italy, 8–13 July 2020; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Debattista, J.; Lange, C.; Auer, S. Luzzu—A methodology and framework for linked data quality assessment. J. Data Semant. 2016, 8, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färber, M.; Bartscherer, F.; Menne, C.; Rettinger, A. Linked data quality of DBpedia, Freebase, OpenCyc, Wikidata, and YAGO. Semant. Web 2018, 9, 77–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshin, D. Master Data Management; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Runeson, P.; Höst, M. Guidelines for conducting and reporting case study research in software engineering. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2009, 14, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.T.; Smith, G.F. Design and natural science research on information technology. Decis. Support Syst. 1995, 15, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.