Abstract

PaxosStore is a high-availability storage system developed to support the comprehensive business of WeChat. With the widespread application of WeChat, it is particularly important to verify the safety of PaxosStore. This work proposes a formal model for the storage system PaxosStore using the process algebra Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP) to clearly reflect the interactions of the components in PaxosStore. More importantly, we utilize the model checker Process Analysis Toolkit (PAT) to simulate and verify the constructed CSP model. We specifically verify the validity of six properties: deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, robustness, consistency, nontriviality and liveness. Through the verification results, we demonstrate that our formalization model successfully satisfies these properties, confirming the correctness and effectiveness of the framework in ensuring secure interactions among the PaxosStore storage system components.

1. Introduction

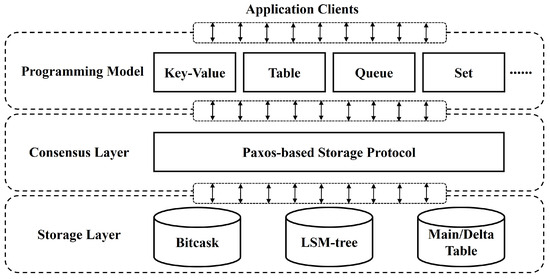

PaxosStore is a high-availability storage system developed to support the comprehensive business of WeChat [1]. The overall architecture of PaxosStore comprises three layers, including the programming model, the consensus layer, and the storage layer, which is illustrated in Figure 1. For the programming model, it provides a variety of data structures exposed to the application clients. The consensus layer implements the Paxos-based storage protocol [2,3]. In order to fulfill diverse performance requirements, the storage layer offers multiple storage engines implemented based on different storage models (Bitcask, LSM-tree, and Main/Delta Table).

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of PaxosStore.

With the widespread application of WeChat, it is particularly important to verify the safety of PaxosStore. The theory and tools of formal methods have become increasingly mature and have gained widespread recognition and application in industry. Since formal methods can help software developers identify errors that are difficult to detect using other approaches, the use of formal verification techniques to enhance the safety and reliability of safety-critical systems has been incorporated into safety standards across various fields in recent years. However, to the best of our knowledge, existing verification efforts on PaxosStore primarily focus on the safety verification of the Paxos protocol in the consensus layer, with limited attention given to the safety verification of the overall storage system.

Goel et al. proved the safety of Paxos by leveraging three structural features in its specification: spatial regularity, temporal regularity, and hierarchical composition [4]. They demonstrated an automatically-inferred inductive invariant for Lamport’s Paxos algorithm. Wang et al. presented a formal colored Petri net model to automatically generate a suite of test cases for the Paxos distributed consensus protocol [5]. The paper [6] provided a formal specification and verification of Lamport’s Multi-Paxos algorithm for the distributed consensus. In their work, the formal specification was written in TLA+ [7], and the proof was written and checked using TLAPS (a proof system for TLA+). Delzanna et al. presented a formal model of Paxos in the executable specification language Promela, extended with a new type of guards, called counting guards [8]. They applied the model checker Spin [9] to automatically validate finite instances of the model and extract preconditions on the size of quorums used in the election phases of the protocol. Paper [10] provided experience feedback on the use of animation and debugging tools to build, improve, and verify a UML model of the Paxos consensus algorithm. From the above research, it is evident that existing verification efforts focus primarily on validating the safety of the PaxosStore’s consensus protocol, while lacking safety verification of the PaxosStore’s storage layer and the interaction between the consensus and storage layers.

Process Algebra is a class of formal methods used to describe and analyze the behaviors of individual processes and their interactions in concurrent systems. It provides a mathematical framework for concurrent computation, enabling the systematic analysis of synchronization, communication, mutual exclusion, and other behaviors between concurrent processes. Process algebra can be used to model the concurrency of a system, describing how multiple processes coordinate their work through synchronization and communication, and analyzing properties such as safety and liveness. It emphasizes modeling the interactions between processes rather than the internal state changes of individual processes. CSP (Communicating Sequential Processes) is a process algebra introduced by Tony Hoare [11], which emphasizes describing communication between processes through event synchronization. In CSP, processes are used to represent each participant in the system, and processes interact with each other through events. Events can be either synchronous (where two processes proceed simultaneously) or asynchronous (where one process does not depend on the actions of another process). In this work, we want to verify the safety of the consensus layer and the storage layer of PaxosStore, as well as the safety of the interaction process between the layers. Through the above analysis, it can be seen that CSP focuses on how processes in the system interact with each other, making it better suited for precisely describing the interaction behavior between processes. Therefore, this paper chooses the process algebra CSP to construct the formal model for PaxosStore.

PAT (Process Analysis Toolkit) [12,13] is a self-contained framework for supporting the composing, simulating, and reasoning of concurrent, real-time systems and other possible domains. It comes with user-friendly interfaces, a featured model editor, and an animated simulator. Most importantly, PAT implements various model-checking techniques catering to different properties such as deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, reachability, LTL properties with fairness assumptions, refinement checking, and probabilistic model checking. Therefore, this paper selects PAT as the supporting tool for model checking.

These observations motivate us to propose the formalization and verification of PaxosStore from a process algebra perspective. In this work, our main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We construct a formal model for the storage system PaxosStore based on the process algebra CSP, particularly concerning the PaxosStore’s consensus layer and storage layer, as well as the interactions between these layers;

- We implement the constructed model based on the model checking tool PAT, and verify the validity of six properties: deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, robustness, consistency, nontriviality and liveness;

- Through the verification results, we demonstrate that our formalization model successfully satisfies these properties, confirming the correctness and effectiveness of the framework in ensuring secure interactions among the storage system components.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the relevant background knowledge. Section 3 presents the formal model of PaxosStore based on CSP. Section 4 implements the constructed model using PAT. Section 5 provides detailed descriptions of six properties along with their verification results. Section 6 reviews related work on process algebra and model checkers for storage systems. Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses potential directions for future work.

2. Background

In this section, we first provide a brief introduction to the Paxos procedure in the consensus layer and the Bitcask model in the storage layer in PaxosStore. Then, we introduce the relevant concepts of process algebra and model checking. After that, we introduce the process algebra CSP and the model checker PAT.

2.1. Paxos and Bitcask

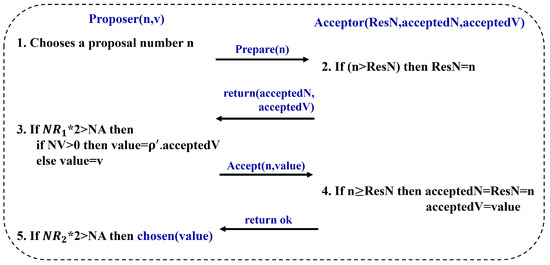

In the consensus layer, the Paxos procedure includes the prepare phase and the accept phase. The prepare phase is for making a preliminary agreement, and the accept phase is for reaching the eventual consensus. The Paxos procedure in PaxosStore uses message passing, illustrated in Figure 2. A proposal is defined as , where n is the proposal number and v is the proposal value. is the number of acceptors. and represent the number of responses from acceptors in the prepare phase and accept phase, respectively. is the number of returned from acceptors.

Figure 2.

The Paxos procedure.

- Proposer chooses a proposal number n and sends it to all acceptors.

- Acceptor receives a proposal number n and compares n and its (the proposal number promised by the acceptor to accept). If n is greater than , then n is assigned to . Acceptor returns and that it has accepted.

- If is greater than , the proposer checks the value returned from the acceptor. If is greater than 0, then the proposer selects as the value where is the one with the highest proposal the number is among the accepted proposals and sends to all acceptors. Otherwise, the proposer chooses a value and sends to all acceptors.

- Acceptor receives a proposal from the proposer. If n is greater than or equal to , then n is assigned to and while is assigned to . Acceptor returns .

- If is greater than , is chosen.

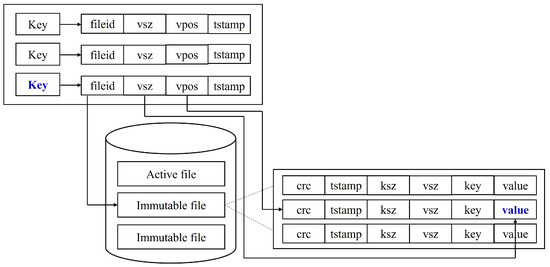

For the storage layer, we focus on the storage model Bitcask. In Bitcask, there is only one active file for writing by the server. When this active file meets a size threshold, it will be closed and a new active file will be created. Once a file is closed, it is considered immutable and will never be opened for writing again. With each write, a new entry is appended to the active file. The format of each key–value entry includes crc, time stamp, the key size, the value size, the key, and the value. When an append completes, a hash table in the memory is updated. A hash table maps every key to a fixed-size structure, giving the file, the value size, the value, position, and the time stamp.

Figure 3 shows the process of reading a value. For reading a value, we first look up the key in the hash table and obtain the information of the value, which includes the ID of the file, the size of the value, the position of the value, and the time stamp. Then, we can read the value according to the information returned from the hash table.

Figure 3.

Reading a value.

2.2. Process Algebra and Model Checking

Formal methods are techniques based on a rigorous mathematical foundation for describing, developing, and verifying computer hardware and software systems. Their mathematical foundation is built upon a formal logical system that integrates formal languages, semantics, and deductive reasoning. Process algebra is a collection of formal languages used for modeling and analyzing concurrent systems, providing a concrete approach to describing interactions, communication, and synchronization among multiple processes. The study of process algebra began in the 1980s, associated with Robin Milner’s pioneering work on CCS and Tony Hoare’s work on CSP. Since its inception, process algebra has proven to be a very important formal language for modeling and analyzing concurrent properties, including mobility, interactivity, safety, and more.

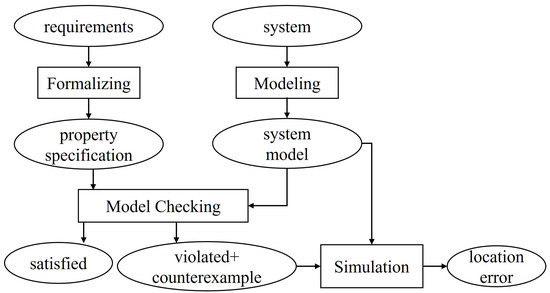

Model Checking is an automated verification technique commonly used to verify the properties of hardware or software systems, particularly in the verification of concurrent systems. Its main goal is to ensure that the system satisfies certain specified properties by systematically checking all possible states of the system. The basic process of model checking is shown in Figure 4. The verification process in this paper is shown as follows.

Figure 4.

Basic process of the model checking approach.

- The characteristics and behaviors of the PaxosStore system are described based on CSP, and a system model is constructed.

- The properties to be verified, such as robustness, data consistency, and others, are abstracted from the requirement specifications and defined as formal specifications.

- The system model and formal specifications are implemented using the model checking tool PAT for automated verification. If the described properties are satisfied, the verification result is returned; if the properties are not satisfied, a counterexample is returned, and the error point is identified through a simulation of the system model.

Table 1 provides a brief description of the relevant concepts. For more terminology descriptions, please refer to the Appendix A.

Table 1.

Descriptions of technical terms.

2.3. CSP and PAT

CSP was proposed by Turing Award recipient Tony Hoare and was mainly designed to model and analyze the behavior of concurrent systems. CSP emphasizes communication between processes, modeling the system by defining the behavior and interactions of the processes. This modeling language has been widely used in various domains, which include the protocols, memory model, NDN-based IoV, SDN under multi-controller architectures and OpenStack swift, OSEK/VDX operating system and Aeolus-based file system, nondeterministic communication in the wireless sensor networks, and more. The syntax of a subset of the CSP language is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notations and meanings of CSP.

- describes an object which first engages in the event a and then behaves exactly as described by process P.

- If P and Q are processes with the same alphabet, then the notation denotes the process that behaves like the system composed of processes P and Q interacting in lock-step synchronization.

- If P and Q are processes, then the notation denotes a process which behaves either like P or like Q.

- denotes that two processes run concurrently without barrier synchronization. Both P and Q may perform their local actions without synchronizing with each other.

- If P and Q are sequential processes with the same alphabet, their sequential composition is a process which first behaves like P, but when P terminates successfully, continues by behaving as Q. If P never terminates successfully, neither does .

The system analysis in PAT is facilitated through two primary methods: simulation and model checking. The visualized simulator enables users to interactively explore their models by selecting one enabled action at a time, allowing the computer to generate system traces randomly, or even constructing the complete state graph. On the other hand, the embedded model checkers in PAT leverage advanced model-checking techniques for systematic analysis. Users can specify assertions in various forms, and with a single click, PAT evaluates their validity. If an assertion is false, a counterexample is generated. Here, we list some definitions and assertions in PAT.

- It defines a global constant N with the initial value 0.

- This statement defines an array named . The size of the array is N.

- This statement declares that c is the channel name and 1 is the buffer size. The channel buffer size must be greater than or equal to 0. Notice that a channel with buffer size 0 sends/receives messages synchronously.

- Given as a process, this assertion asks whether is deadlock-free or not.

- Given as a process, this assertion asks whether is divergence-free or not.

- Given as a process, this assertion asks whether can reach a state at which some given condition is satisfied.

- PAT supports the full set of LTL syntax. This assertion asks whether satisfies the LTL formula F, where the syntax of F is defined as the following rules:where e is an event, is a pre-defined proposition, reads as “always”, reads as “eventually”, X reads as “next”, U reads as “until”, and R reads as “release”.

3. Modeling PaxosStore

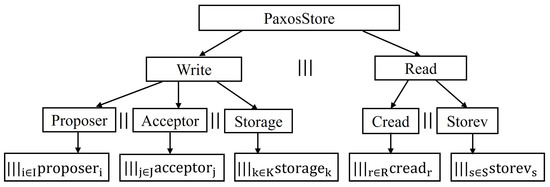

In this section, we propose the CSP model of PaxosStore. The formalization is proceeded based on the introduction to PaxosStore in Section 2. Figure 5 illustrates the interaction and communication framework among all processes in the PaxosStore model.

Figure 5.

The framework of the PaxosStore model.

The entire system is modeled as the interleaving of two CSP processes, and , where represents the process of writing a value, and represents the process of reading a value. Equation (1) provides the formal definition of the entire system.

For the writing process, there are three crucial processes running in parallel, which are abstracted as the processes , , and . Equation (2) describes the formal definition of the writing process.

Next, we provide the formal definitions of the three processes , , and , respectively.

3.1. Proposer

In the proposer operations, each proposer is assigned a unique ID, denoted as i, and corresponds to a process called . Therefore, the process can be formalized as in Equation (3). Here, I represents the set of all proposer IDs associated with the proposer tasks.

The process describes the details of proposer operations. We first define the channels and messages used in the process.

The channels in the process are as follows.

- : channel between and .

- : channel between and .

The messages in the process are as follows, where # is just a separator.

- is sent from to , which includes the proposal number promised by the acceptor to accept and for the proposal to be accepted.

- is sent from to , which includes the proposal number and the proposal value.

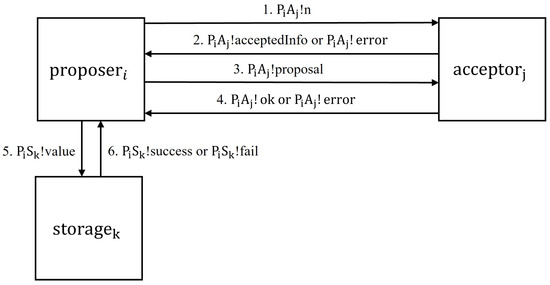

Figure 6 illustrates the message communication between the three processes , , and .

Figure 6.

The message communication.

We formalize the process as in Equation (4). Equations (5) to (10) represent the formal definitions of subprocesses to , respectively.

In the process , it first sends a proposal number n via channel to the process . Then, either receives a message that the acceptor has already accepted, or receives an error message. If receives the message , then the value of increases by 1. If is greater than , then checks the message returned from the acceptor. If is not null, then the value of increases by 1. If is greater than 0, then selects a value , as the value where is the one with the highest proposal number among the accepted proposals and sends to all acceptors. Otherwise, chooses a value and sends to all acceptors. After that, the process either receives a message or receives an error message. If it receives a message, then the value of increases by 1. If is greater than , then the is chosen. sends to via channel . Then, either receives a message or receives a message from the process .

3.2. Acceptor

In the acceptor operations, each acceptor is assigned a unique ID, denoted j, which corresponds to a process called . Therefore, the process can be formalized as in Equation (11). Here, J represents the set of all acceptor IDs associated with the acceptor tasks.

The process describes the details of the acceptor operations. We formalize the process as in Equation (12). Equation (13) represents the formal definition of subprocess .

In the process , it receives a proposal number n from the proposer. If n is greater than the proposal number that the acceptor promises to accept, then n is assigned to . After that, sends to the proposer and receives a proposal from the proposer. If is greater than or equal to , then the acceptor accepts this proposal and sends the message to the proposer. Otherwise, it sends the message to the proposer.

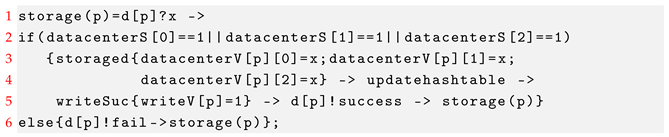

3.3. Storage

In the storage operations, each storage is assigned a unique ID, denoted as k, and corresponds to a process called . Therefore, the process can be formalized as Equation (14). Here, K represents the set of all storage IDs associated with the storage tasks in the writing process.

The process describes the details of the storage operations in the writing process. We formalize the process as in Equation (15).

For the process , it first receives a value from a proposer. Then, it verifies whether these datacenters, which are used to store the value are available or not. If these datacenters are available, then the value is stored successfully. After that, updates the hash table and sends the message to via channel . Otherwise, it sends the message to .

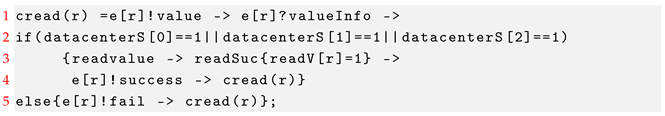

3.4. Read

For the reading process, there are two crucial processes running in parallel, which are abstracted as the processes , . Equation (16) describes the formal definition of the reading process.

In the reading operations, each reader is assigned a unique ID, denoted as r, and corresponds to a process called . Therefore, the process can be formalized as Equation (17). Here, R represents the set of all reader IDs associated with the reading tasks.

The process describes the details of the reading operations. We first define the channels and messages used in the process.

The channels in the process are as follows.

- : channel between and .

The messages in the process are as follows, where # is just a separator.

- is sent from to , indicating a request to initiate a data read.

- is sent from to , which includes the ID of the file, the size of the value, the position of the value, and the time stamp.

We formalize the process as Equation (18).

requests to read a value. Then, it receives the information of this value. After that, it can read this value according to this information.

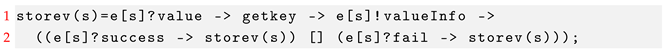

The process models the behaviors of the storage system in the reading operations. Each task is assigned a unique ID, denoted as s, and corresponds to a process called . Therefore, the process can be formalized as in Equation (19). Here, S represents the set of all task IDs associated with the storage data node in the reading operations.

The process describes the details of the storage data ceter in the reading operations. We formalize the process as in Equation (20).

receives a reading request from the client, then it looks up the offset of the key in the memory index (hash table). After that, it reads the key’s data structure based on the offset and sends it to the client.

3.5. Example of the Model

To better understand the execution process of the write model, we provide an example here. We only demonstrate the simplest communication scenario: the interaction among a proposer, an acceptor, and a storage node. Before the proposal begins, we make the following assumptions: the proposal number is 2, the proposal value is 3, the number of responses returned from the acceptors is 0, and the acceptor has not received any other proposals. According to the construction process of the write model, the first round of interactions among these three nodes is as follows.

We also provide an example to illustrate the execution process of the read model. We only demonstrate the simplest communication scenario: the interaction between a reading node and a storage node. Before the reading begins, we make the following assumptions: the key exists in the memory index with an offset of 4096. According to the construction process of the read model, the first round of the interaction between the two nodes is as follows.

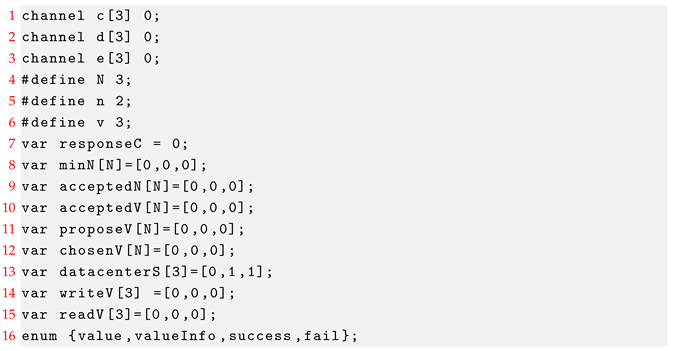

4. Implementing the CSP Model in PAT

In this section, we implement the PaxosStore model based on the model checker PAT. We first provide some representative global definitions used in the process definitions. Then, we provide some process definitions as examples.

4.1. Global Definitions

For defining the processes, various parameters are configured for reading and writing values. Here, we provide some global constants and variables as examples.

In the model checker PAT, the process proposer(i) and process acceptor(j) communicate through message passing on channel c. The process proposer(i) and process storage(p) communicate with each other via channel d. The processes cread(r) and storev(s) communicate with each other via channel e. The constant N is the number of proposers and acceptors. n is the initial proposal number and v is the initial proposal value. responseC is the number of responses from acceptors, and its initial value is 0.

The array minN records the least proposal number that the acceptor is willing to accept. The arrays acceptedN and acceptedV store the proposal number and proposal value that the acceptor has accepted, respectively. The array proposeV holds the values that the proposer has proposed. The array chosenV stores the value that has been chosen. The array datacenterS represents the state of each datacenter, where 0 indicates that the datacenter is unavailable, and 1 indicates that the datacenter is available. Initially, the states of the three datacenters are set to 0, 1, and 1. The array writeV tracks whether the writer has successfully written the value: 0 indicates a failure, and 1 indicates success. Similarly, the array readV records whether the reader has successfully read the value. The last statement defines four communication messages.

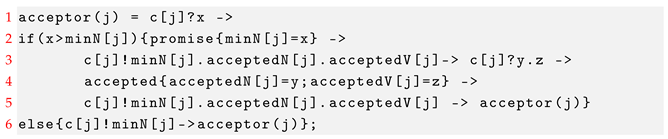

4.2. Process Definitions

Here, we illustrate some representative process definitions as examples.

For the process acceptor(j), it first receives a proposal number from the proposer. If the proposal number received is greater than the least proposal number that acceptor j promises to accept, then the proposal number received is assigned to minN[j]. Acceptor j returns minN[j] and the proposal that it has accepted to the proposer. Otherwise, it returns minN[j]. For the first case, acceptor j prepares to receive a new proposal. When it receives a new proposal from the proposer, it compares the proposal number with minN[j]. If the proposal number is greater than or equal to minN[j], then it accepts this new proposal and returns the accepted result to the proposer.

For storage(p), it first receives the value chosen from the proposer. If at least one of the three datacenters is available, then the value is stored successfully. After that, it updates the hash table and sends the message success to the proposer. Otherwise, it sends the message fail to the proposer.

For the process cread(r), it first sends a request for reading a value to the process storev(s) via the channel e. Then, it will receive the information valueInfo about this value from the process storev(s). If at least one of the three datacenters is available, then it can read this value according to the information successfully.

For storev(s), it first receives a reading request. Then, it looks up the key in the hash table and returns the information of the value.

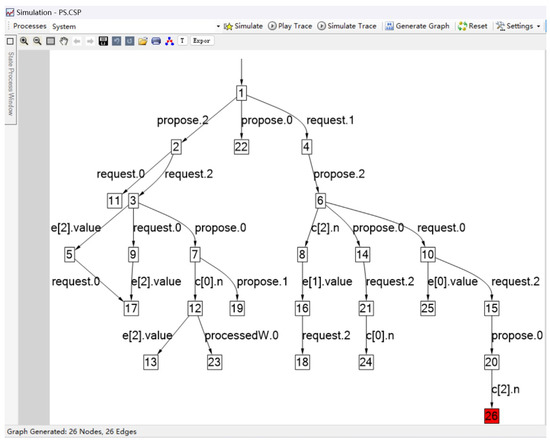

Figure 7 shows a simulation of the CSP model we constructed, highlighting the enabled events and event traces within the model.

Figure 7.

A simulation for PaxosStore.

5. Verification

In this section, we verify the validity of six properties: deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, robustness, consistency, nontriviality and liveness. Through the verification results, we demonstrate that our formalization model successfully satisfies these properties, confirming the correctness and effectiveness of the framework in ensuring secure interactions among the PaxosStore storage system components.

5.1. The Properties

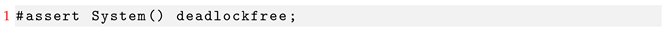

We first provide a description of deadlock-freeness.

- Property 1: Deadlock-freeness

In PaxosStore, we should avoid the situation in which some clients are waiting for the resources that have been occupied by other clients infinitely. In the model checker PAT, there is a primitive to describe this situation:

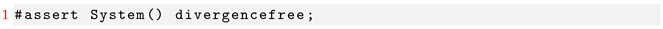

- Property 2: Divergence-freeness

A divergent system is usually undesirable. In the model checker PAT, there is a primitive to describe this situation:

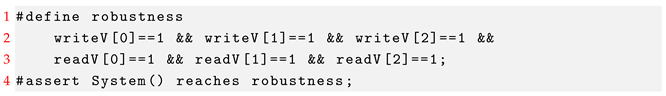

- Property 3: Robustness

The primary objective of PaxosStore is to store the data reliably even in the presence of failures. In WeChat production, hardware failure and network outages are the two main sources of failure. Here, we focus on the datacenter failures. We verify that readers can read the value and writers can write the value successfully when some of the datacenters break down. Due to the limitations of the state space, we have only constructed three datacenters in the model, but this does not affect the verification of the model’s properties. We have tested that when the three datacenters have the states [1,1,1], [1,1,0], [1,0,1], [0,1,1], [1,0,0], [0,1,0], [0,0,1], where 0 means that the datacenter breaks down and 1 means that the datacenter is available, and property 3 is satisfied. This assertion about this property is described as below:

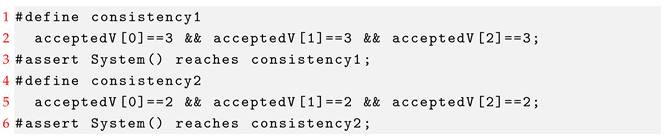

- Property 4: Consistency

PaxosStore is designed as a multi-homed system that runs actively on multiple datacenters around the clock, and meanwhile, employs the Paxos protocol for value consensus. The Paxos consensus algorithm must satisfy the consistency property, that is, only a single value may be chosen. This property can use two assertions to describe in PAT, which is shown below:

When only one of the two assertions is valid, the consistency property is satisfied, i.e., if consistency1 is valid and consistency2 is not valid, then the PaxosStore model satisfies the consistency property.

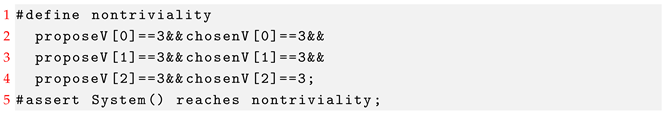

- Property 5: Nontriviality

In addition to the above properties, a Paxos algorithm used in PaxosStore also needs to satisfy the property nontriviality; that is, only a value that has been proposed may be chosen. This assertion is described as below:

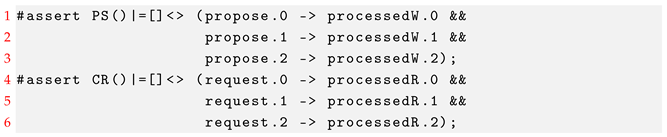

- Property 6: Liveness

Liveness properties describe the infinite behavior of the model [14], ensuring that desirable events will eventually occur. In this model, every proposal and every file read request will be processed infinitely often, ensuring fair handling. This property can use two assertions to describe in PAT, which is shown below:

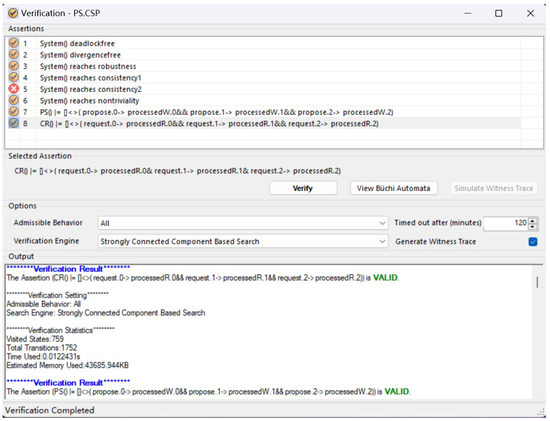

5.2. Evaluation Results

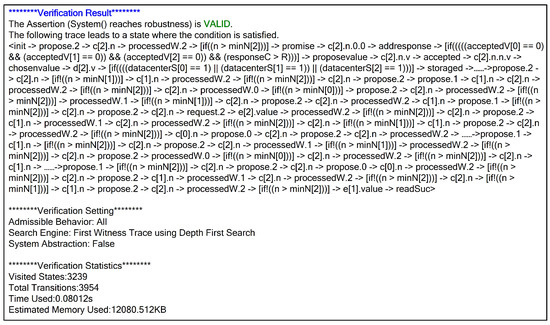

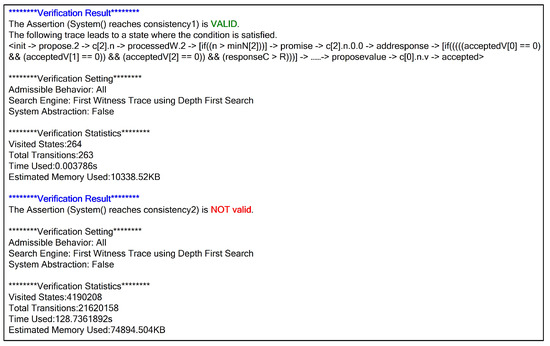

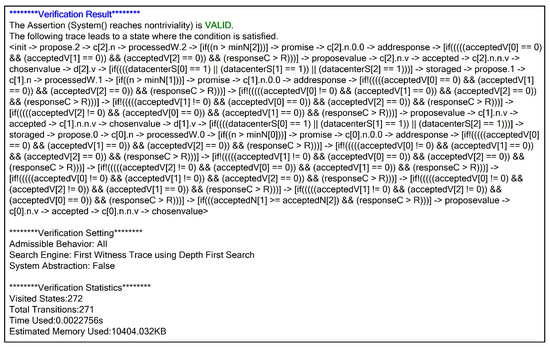

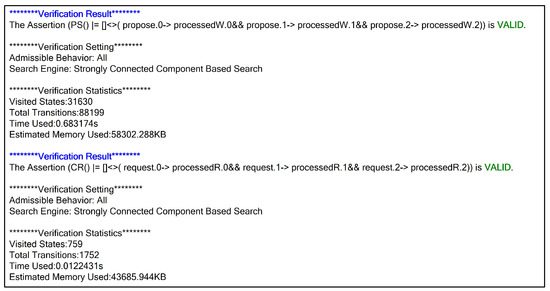

The verification results are shown in Figure 8. From Figure 8, we find that the properties deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, robustness, consistency, nontriviality, and liveness are all valid, indicating that the constructed model satisfies the PaxosStore requirements, and these properties confirm the correctness and effectiveness of the framework in ensuring secure interactions among the PaxosStore storage system components. We provide a detailed analysis and evaluation for each assertion.

Figure 8.

Verification results for PaxosStore.

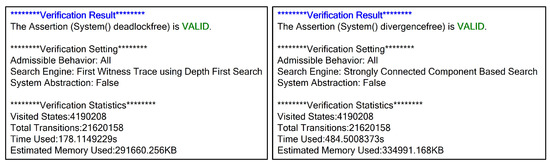

Table 3 provides a verification statistics table showing runtime, memory consumption, visited states, and total transitions for each assertion. From the statistical table, it can be seen that the verification process of the three assertions—deadlock-free, divergence-free, and consistency2—performs a depth-first search of all possible states of the system. These states do not lead to deadlock or divergence, nor do they satisfy consistency2. At the same time, it can also be seen that these three assertions are the most time and memory-consuming. Therefore, in the subsequent model extension work, a better abstraction of the model will be considered.

Table 3.

Verification statistics.

We also provide the detailed verification results of the assertions. Figure 9 shows the detailed verification results of deadlock-freeness and divergence-freeness. Deadlock-freeness is valid, which means that the CSP model will not enter a deadlock state. Divergence-freeness is valid, which demonstrates that the system model is well defined. The verification assertions for the two properties are applicable to all storage systems, meaning that any storage system can adopt the verification method presented in this paper to validate the two properties.

Figure 9.

Detailed verification results of deadlock-freeness and divergence-freeness.

Figure 10 shows the detailed verification results of robustness.

Figure 10.

Detailed verification result of robustness.

From Figure 10, it can be seen that this assertion is valid. The result indicates that the system successfully stores data even when storage nodes experience failures. The verification method is applicable to all storage systems that use replication mechanisms to store data, including HDFS, Ceph, GFS, OpenStack swift, and others.

Figure 11 shows the detailed verification results of consistency. From Figure 11, it can be seen that the first assertion is valid, while the second assertion is invalid. The result indicates that only a single value may be chosen, in other words, only one value ultimately reaches consensus. The verification method can not only verify the consistency of the Paxos algorithm, but also be used for the consistency verification of other consensus algorithms, such as Raft, PBFT, HotStuff, and others.

Figure 11.

Detailed verification result of consistency.

Figure 12 shows the detailed verification results of nontriviality. From Figure 12, it can be seen that this assertion is valid. The result indicates that only a value that has been proposed may be chosen. Similar to consistency verification assertions, this verification assertion can also be used for property verification of more consensus algorithms.

Figure 12.

Detailed verification result of nontriviality.

Figure 13 shows the detailed verification results of liveness. From Figure 13, it can be seen that the two assertions are valid. The verification results show that every proposal and every read request will be processed infinitely often. The descriptions of the two verification assertions apply to the liveness verification of most storage systems that use consensus protocols.

Figure 13.

Detailed verification result of liveness.

6. Related Work

In recent years, significant efforts have been made to explore the formal modeling and verification of storage systems. Existing process algebra systems provide a rigorous methodological foundation for modeling and analyzing the behavior and characteristics of concurrent systems. CSP [11], CCS [15], and ACP [16] have been introduced to model the communication among processes in reactive systems. Sun et al. proposed CSP# to specify concurrent systems by integrating CSP-like compositional operators with sequential programs that update shared variables [17]. Reed et al. extended CSP into timed CSP by incorporating a real-time model [18]. Since we focus more on the interaction behavior of components and the safety of the system, we choose CSP to construct the system model. Notably, CSP has been widely adopted across various domains. Chen et al. modeled and verified Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) based on CSP [19]. Xu et al. used CSP to model and verify kafka messaging mechanism [20]. Fei et al. presented a formal model for AKA protocols using CSP [21]. Liu et al. presented a CSP model for AMQP [22]. Xiao et al. used CSP to model PSO and verified four properties based on PAT [23]. Chen et al. used CSP to formalize NDN-based IoV [24]. In their paper, they mainly focused on the data access mechanism. Huang et al. proposed a formal model of the OSEK OS at the code level based on CSP and verified three significant properties of the OSEK-based system [25]. The paper [26] presented a model for wireless sensor networks (WSNs) to be used for the formal verification of communication reliability in mesh networks based on CSP.

A variety of model checkers have been developed to support the simulation and verification of models. UPPAAL [27], based on the theory of timed automata [28], is designed for the modeling, validation, and verification of real-time systems. Chen et al. used the model checker UPPAAL to implement the CaIT model and verified six temporal properties of the model [29]. Fei et al. modeled and verified some fundamental properties of the NLSR protocol using the model checker UPPAAL [30]. UPPAAL is only suitable for time-related systems. Meseguer initially proposed the theory of rewriting logic [31], which later led to the introduction of the rewriting engine Maude by Meseguer and colleagues. Currently, Maude has been widely applied across various fields, including equivalence checking of quantum circuits based on dirac notation [32], raft log replication [33], and so on. Maude is complex to use, requires a strong theoretical background, and lacks a user-friendly graphical interface. SPIN is an efficient verification system for the models of distributed software systems [34], and it has been used to model and analyze the IoT protocols [35], predicate transition nets [36], and more. SPIN does not support the verification of temporal properties and cannot handle time-related issues. Rossi proposed a logic-based technique for verifying both security and correctness properties of multilevel service compositions [37]. With the aid of the NCSU Concurrency Workbench model checker, both non-interference and compliance can be verified. However, this verification technique lacks a user-friendly graphical interface. PAT [12,13] is a comprehensive framework for composing, simulating, and reasoning about concurrent and real-time systems, as well as other domains. It integrates multiple verification techniques, such as LTL verification, temporal verification, and probabilistic model checking. Additionally, it offers a graphical interface and a flexible plugin architecture. PAT has been widely used in verification tasks across various fields, such as smart contracts [38], autonomous systems [39], and more. Due to PAT’s versatility and user-friendly graphical interface, this paper selects PAT for model implementation and property verification.

7. Conclusions

This work presents a formal model of the PaxosStore storage system using CSP to clearly capture the interactions between its components. More importantly, we employ PAT to simulate and verify the constructed CSP model. Specifically, we verify the validity of six properties: deadlock-freeness, divergence-freeness, robustness, consistency, nontriviality, and liveness. The verification results demonstrate that our formalized model successfully satisfies these properties, confirming the correctness and effectiveness of the framework in ensuring secure interactions among the components of the PaxosStore storage system.

The current PaxosStore model’s scale in this paper has not led to a state explosion issue during the verification process. The storage layer in PaxosStore provides multiple storage models, including Bitcask, LSM-tree, and Main/Delta Table. In this work, the modeling and verification of the storage layer are primarily centered around the Bitcask model. Since the focus during model construction is on storage process communication and the correct storage and retrieval of data, rather than the differences in storage interfaces, the other two storage interfaces do not affect the property verification of the model.

Data integrity refers to the characteristic of data remaining accurate, complete, and unaltered during storage, transmission, and querying processes. In this paper, we have verified the robustness and data consistency within the storage system. In the future, we will incorporate the verification of query integrity to ensure that data are not tampered with.

To comprehensively model system behavior and conduct more analyses, the model will be expanded in the future. The potential expansion directions include the following:

- Incorporating the other two storage interfaces LSM-tree and Main/Delta Table into the model.

- Incorporating more analytical work, including read/write latency, the verification of query integrity to ensure that data are not tampered with.

As the model expands, the verification process may encounter the state explosion problem. We will consider using the following methods to address the potential state explosion problem.

- Theorem proving may provide a solution to the possible state space explosion problem. The commonly used tools for theorem proving include Coq [40] and Isabelle [41].

- Symbolic model checking [42] utilizes symbolic methods, such as Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs) or SAT solvers [43], to efficiently represent and explore the system’s state space, thereby overcoming the state explosion problem. NuSMV [44] is a tool that supports both symbolic and explicit state space exploration. Some existing research works have provided valuable research ideas, especially those related to the property verification [45,46], process algebra [47,48], and state–space exploration [49].

- Abstraction techniques [50] are a method for simplifying system models, primarily used to mitigate the state explosion problem and enhance the scalability of formal verification. Some existing research works have also provided valuable ideas for future studies, especially those related to state–space exploration [51].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, W.X.; software, W.X.; validation, W.X., Y.Y. and C.Z.; formal analysis, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, W.X., Y.Y. and C.Z.; supervision, W.X. and C.Z.; funding acquisition, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Open Project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Trustworthy Computing (No. OP202004).

Data Availability Statement

All the data mentioned in this paper are available through the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Glossary of Technical Terms

Table A1 provides a glossary of technical terms used in this paper.

Table A1.

Glossary of technical terms.

Table A1.

Glossary of technical terms.

| Terms | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Formal Methods | Techniques based on mathematics and logical reasoning, used to describe, develop, and verify computer systems, ensuring the correctness, safety, and reliability of the systems. |

| Process Algebra | A formal framework for modeling and analyzing concurrent systems using algebraic operations. |

| CSP | A process algebra developed by Tony Hoare for modeling interactions among processes using message-passing. |

| Model Checking | An automated technique that systematically explores all possible states of a system to verify correctness properties. |

| PAT | A model checking tool that supports visual simulation and validation of the CSP models. |

| PaxosStore | A high-availability storage system developed to support the comprehensive business of WeChat. |

| Deadlock-freeness | There is always at least one action that can be executed. |

| Divergence-freeness | A system or process that, along any execution path, will not enter an infinite internal loop. |

| Theorem Proving | A mathematical proof method based on logical reasoning. |

| Symbolic Model Checking | An automated formal verification technique that compresses the state space using symbolic methods, effectively mitigating the state explosion problem. |

| Abstraction Techniques | A method for simplifying system models, primarily used to reduce the state space and enhance the scalability of formal verification. |

References

- Zheng, J.; Lin, Q.; Xu, J.; Wei, C.; Zeng, C.; Yang, P.; Zhang, Y. PaxosStore: High-availability Storage Made Practical in WeChat. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2017, 10, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport, L. Fast Paxos. Distrib. Comput. 2006, 19, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, J.Z.; Wojciechowski, P.T.; Santos, N.; Zurkowski, T.; Schiper, A. Recovery Algorithms for Paxos-Based State Machine Replication. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 18, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Sakallah, K.A. Towards an Automatic Proof of Lamport’s Paxos. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference on Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design—FMCAD 2021, New Haven, CT, USA, 19–22 October 2021; pp. 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Kristensen, L.M.; Meling, H.; Stolz, V. Automated test case generation for the Paxos single-decree protocol using a Coloured Petri Net model. J. Log. Algebr. Methods Program. 2019, 104, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Liu, Y.A.; Stoller, S.D. Formal Verification of Multi-Paxos for Distributed Consensus. In Proceedings of the FM 2016: Formal Methods—21st International Symposium, Limassol, Cyprus, 9–11 November 2016; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, D.; Doligez, D.; Lamport, L.; Merz, S.; Ricketts, D.; Vanzetto, H. TLA + Proofs. In Proceedings of the FM 2012: Formal Methods—18th International Symposium, Paris, France, 27–31 August 2012; pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Delzanno, G.; Tatarek, M.; Traverso, R. Model Checking Paxos in Spin. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Games, Automata, Logics and Formal Verification, Verona, Italy, 10–12 September 2014; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari, M. Principles of the Spin Model Checker; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier, M.; Teodorov, C.; Jouault, F.; Brun, M.; Lagadec, L. Debugging Paxos in the UML Multiverse. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems, Västerås, Sweden, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 811–820. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, C.A.R. Process Algebra: A Unifying Approach. In Proceedings of the Communicating Sequential Processes: The First 25 Years, Symposium on the Occasion of 25 Years of CSP, London, UK, 7–8 July 2004; pp. 36–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Dong, J.S. Developing Model Checkers Using PAT. In Proceedings of the Automated Technology for Verification and Analysis—8th International Symposium, ATVA 2010, Singapore, 21–24 September 2010; pp. 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.S.; Pang, J. PAT: Towards Flexible Verification under Fairness. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Verification, 21st International Conference, CAV 2009, Grenoble, France, 26 June–2 July 2009; pp. 709–714. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Butler, M.J.; Cîrstea, C.; Hoang, T.S. A fairness-based refinement strategy to transform liveness properties in Event-B models. Sci. Comput. Program. 2023, 225, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R. A Calculus of Communicating Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.A.; Klop, J.W. Process Algebra for Synchronous Communication. Inf. Control. 1984, 60, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.S.; Chen, C. Integrating Specification and Programs for System Modeling and Verification. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Software Engineering, TASE 2009, Tianjin, China, 29–31 July 2009; pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G.M.; Roscoe, A.W. A Timed Model for Communicating Sequential Processes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1988, 58, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, R.; Zhu, H. Formalization and Verification of Enhanced Group Communication CoAP. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2024, 34, 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yin, J.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, L. Formalization and verification of Kafka messaging mechanism using CSP. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2023, 20, 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yin, J. FVF-AKA: A Formal Verification Framework of AKA Protocols for Multi-server IoT. Form. Asp. Comput. 2023, 35, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dong, W.; Zhu, H.; Su, Z. Formal Verification and Security Analysis of AMQP. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference, COMPSAC 2024, Osaka, Japan, 2–4 July 2024; pp. 2177–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Q.; Vinh, P.C. Modeling and Verifying PSO Memory Model Using CSP. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2022, 27, 2068–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhu, H.; Yin, J.; Fei, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, M. Modeling and verifying NDN-based IoV using CSP. J. Softw. Evol. Process. 2022, 34, e2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pang, H.; Shi, J. Modeling and Verification of A Timing Protection Mechanism in the OSEK/VDX OS using CSP. Form. Asp. Comput. 2020, 32, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.N.; Engmark, A.E.; Hendseth, S.; Mathisen, G. Formalising Nondeterministic Communication in Wireless Sensor Networks Using CSP. In Proceedings of the 10th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing, MECO 2021, Budva, Montenegro, 7–10 June 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann, G.; David, A.; Larsen, K.G. A Tutorial on Uppaal. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods for the Design of Real-Time Systems, International School on Formal Methods for the Design of Computer, Communication and Software Systems, SFM-RT 2004, Bertinoro, Italy, 13–18 September 2004; pp. 200–236. [Google Scholar]

- Alur, R.; Dill, D.L. A Theory of Timed Automata. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1994, 126, 183–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhu, H. IoT Modeling and Verification: From the CaIT Calculus to UPPAAL. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2023, 106, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yin, J. Modeling and verifying NLSR protocol of NDN for CPS using UPPAAL. J. Softw. Evol. Process. 2023, 35, e2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, J. Conditioned Rewriting Logic as a United Model of Concurrency. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1992, 96, 73–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.M.; Ogata, K. Equivalence Checking of Quantum Circuits Based on Dirac Notation in Maude. In Proceedings of the Rewriting Logic and Its Applications—15th International Workshop, WRLA 2024, Luxembourg, 6–7 April 2024; pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi, T.; Ogata, K. Formal Specification and Model Checking of Raft Log Replication in Maude. In Proceedings of the 29th International DMS Conference on Visualization and Visual Languages, DMSVIVA 2023, KSIR Virtual Conference Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 29 June–3 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Holzmann, G.J. The Model Checker SPIN. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1997, 23, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Kumar, G.S. Abstracting IoT protocols using timed process algebra and SPIN model checker. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 1611–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, D.M.M.; He, X. A Method to Analyze Predicate Transition Nets Using SPIN Model Checker. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2017, 27, 1455–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S. Model Checking Adaptive Multilevel Service Compositions. In Proceedings of the Formal Aspects of Component Software—7th International Workshop, FACS 2010, Guimarães, Portugal, 14–16 October 2010; pp. 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, N.; Hou, Z.; Dong, J.S. Model Checking Concurrency in Smart Contracts with a Case Study of Safe Remote Purchase. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods and Software Engineering—25th International Conference on Formal Engineering Methods, ICFEM 2024, Hiroshima, Japan, 2–6 December 2024; pp. 391–407. [Google Scholar]

- Bride, H.; Dong, J.S.; Green, R.; Hóu, Z.; Mahony, B.P.; Oxenham, M. GRAVITAS: A model checking based planning and goal reasoning framework for autonomous systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 97, 104091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertot, Y.; Castéran, P. Interactive Theorem Proving and Program Development—Coq’Art: The Calculus of Inductive Constructions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nipkow, T.; Paulson, L.C.; Wenzel, M. Isabelle/HOL—A Proof Assistant for Higher-Order Logic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Burch, J.R.; Clarke, E.M.; McMillan, K.L.; Dill, D.L.; Hwang, L.J. Symbolic Model Checking: 10^20 States and Beyond. Inf. Comput. 1992, 98, 142–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Park, I. SAT-based unbounded symbolic model checking. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2005, 24, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, A.; Clarke, E.M.; Giunchiglia, E.; Giunchiglia, F.; Pistore, M.; Marco Roveri, M.; Sebastiani, R.; Tacchella, A. NuSMV 2: An OpenSource Tool for Symbolic Model Checking. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Verification, 14th International Conference, CAV 2002, Copenhagen, Denmark, 27–31 July 2002; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Meulen, J.V.; Pecheur, C. Combining Partial-Order Reduction and Symbolic Model Checking to Verify LTL Properties. In Proceedings of the NASA Formal Methods—Third International Symposium, NFM 2011, Pasadena, CA, USA, 18–20 April 2011; pp. 406–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardelli, A.; Cimatti, A.; Tonetta, S.; Zamboni, M. Symbolic Model Checking of Relative Safety LTL Properties. In Proceedings of the iFM 2023—18th International Conference, iFM 2023, Leiden, The Netherlands, 13–15 November 2023; pp. 302–320. [Google Scholar]

- Meulen, J.V.; Pecheur, C. Efficient Symbolic Model Checking for Process Algebras. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods for Industrial Critical Systems, 13th International Workshop, FMICS 2008, L’Aquila, Italy, 15–16 September 2008; pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.K.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.S. Symbolic Model-Checking of Stateful Timed CSP Using BDD and Digitization. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods and Software Engineering—14th International Conference on Formal Engineering Methods, ICFEM 2012, Kyoto, Japan, 12–16 November 2012; pp. 398–413. [Google Scholar]

- Niehage, M.; Remke, A. Symbolic state-space exploration meets statistical model checking. Perform. Eval. 2025, 167, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moundanos, D.; Abraham, J.A.; Hoskote, Y.V. Abstraction Techniques for Validation Coverage Analysis and Test Generation. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1998, 47, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.M.; Grumberg, O.; Jha, S.; Lu, Y.; Veith, H. Counterexample-guided abstraction refinement for symbolic model checking. J. ACM 2003, 50, 752–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).