Abstract

To aid in the selection of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) chatbots, this paper introduces a fuzzy multi-attribute decision-making framework based on their key features and performance. The proposed framework includes a new modification of the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), adapted for an interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy (IVHFF) environment. This TOPSIS extension addresses the limitations of classical TOPSIS in handling complex and uncertain data capturing detailed membership degrees and representing hesitation more precisely. The framework is applicable for both static and dynamic evaluations of GAI chatbots in crisp or fuzzy assessments. Results from a practical example demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach for comparing and ranking GAI chatbots. Finally, recommendations are provided for selecting and implementing these conversational agents in various applications.

1. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) chatbots, also known as conversational agents, are becoming an increasingly prevalent type of chatbot worldwide for several reasons. Advancements in AI and natural language processing have significantly enhanced their capabilities [1]. These intelligent chatbots leverage large language models (LLMs) to generate human-like responses in natural language, enabling more dynamic and contextually appropriate interactions compared to their traditional rule-based predecessors [2,3].

Additionally, the rise of digital communication platforms and the growing demand for instant customer service have driven businesses to adopt GAI chatbots. These systems provide a cost-effective way to deliver customer support, answer queries, and even facilitate transactions.

The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the adoption of remote work and virtual communication, increasing the demand for AI chatbots [4]. They have proven instrumental in managing the surge of online interactions, such as handling customer inquiries, scheduling appointments, and disseminating information.

The flexibility and scalability of GAI chatbots make them suitable for diverse industries, including construction [5], healthcare [6], finance [7], and e-commerce [8], but each industry may face unique regulatory, operational, or technological constraints. By tailoring chatbots to the specific requirements and integrating them into existing systems, organizations in many sectors can potentially enhance productivity and user experiences [9].

Market research predictions confirm a growing adoption of AI chatbots in the coming years. According to a Statista forecast [10], the global chatbot market is projected to reach approximately USD 1.25 billion by 2025—a nearly fivefold increase from USD 190.8 million in 2016. Meanwhile, Gartner estimated that over 80% of enterprises will leverage GAI APIs or applications by 2026 [11], highlighting the rapid and widespread adoption of advanced AI technologies for enhancing business efficiency, innovation, and customer experiences. However, this growth also presents challenges in areas such as data privacy, ethics, and addressing skill gaps.

Despite their growing popularity, GAI chatbots face several challenges to widespread adoption. Key obstacles include the following:

- Lack of trust: Users may hesitate to fully trust AI-powered chatbots, especially when dealing with sensitive information or complex interactions. Building trust in the accuracy, security, and reliability of these systems is critical for their broader acceptance;

- Limited understanding and awareness: Many users are unfamiliar with the capabilities and benefits that GAI chatbots can provide. This lack of knowledge or understanding about how they function and what they offer may hinder adoption;

- User experience and satisfaction: Poorly designed chatbots can lead to unsatisfactory user experiences. Frustrating interactions or failure to resolve queries effectively may discourage continued use;

- Cost and ROI: Developing and maintaining GAI chatbots can be expensive for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Organizations must carefully assess the return on investment (ROI) and weigh costs against potential benefits;

- Ethical and bias concerns: GAI chatbots are only as reliable and fair as the data they are trained on, which can sometimes perpetuate biases or unfair practices. Ensuring chatbots are ethical, unbiased, and inclusive is important for their acceptance and broader implementation.

Overcoming these barriers will require advancements in technology, increased transparency, education, and a focus on user-centric design. To address the first three challenges, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods can be employed. These techniques enable organizations to compare a finite set of decision alternatives across various criteria, helping them select the most feasible option. MCDM methods have been successfully applied in several GAI-related fields, such as technology selection [12] and cloud system prioritization [13].

While conventional MCDM methods are reliable, they often struggle to address the complexities associated with imprecise and ambiguous evaluations. In contrast, fuzzy-based methods are specifically designed to manage such uncertainties, making them more effective in identifying the most suitable alternatives.

Various MCDM techniques have been enhanced through the integration of fuzzy sets and their advanced extensions [14]. By incorporating fuzzy assessments, these methods provide a more accurate representation of real-world conditions, thereby improving the reliability of rankings in scenarios characterized by subjectivity and evaluation uncertainties.

The key advantage of fuzzy multi-criteria algorithms lies in their ability to produce more realistic and dependable rankings, enhancing the overall decision-making process.

Key contributions of this paper include the following:

- Analysis and categorization of existing multi-criteria approaches for AI chatbot selection, classified by the techniques used and the types of estimates employed (numeric, interval, linguistic values, as well as fuzzy numbers). These approaches are then grouped into three main categories based on complexity (number of multi-criteria techniques), flexibility (type of fuzziness), and iterativeness (single or repeated data processing);

- Development of a theoretical framework for ranking GAI chatbots using both single and hybrid methods with crisp and fuzzy estimates. Single methods rely on one weight determination or ranking technique, while hybrid methods integrate several. The framework also incorporates complementary capabilities, including evaluations using crisp or fuzzy numbers, statistical analyses, and ranking interpretation, to enhance the decision-making process. Additionally, it introduces a newly developed 3D distance metric to enhance the effectiveness of the Fermatean fuzzy group TOPSIS method in case of hesitant interval assessments for more precise and effective multi-criteria comparisons of chatbot features;

- Creation of static and dynamic rankings of an AI chatbot dataset via single or repeated multi-criteria decision analysis. In static rankings, experts’ opinions serve as inputs for the decision matrices, whereas dynamic rankings measure user attitudes based on behavior or survey data. Comparative analyses with other multi-criteria baselines underscore both the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed methods.

The paper begins with a literature review in Section 2, discussing the motivation behind exploring fuzzy ranking for GAI chatbots. Next, Section 3 details the proposed theoretical decision-making framework for GAI chatbot selection, emphasizing the role of interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy numbers (IVHFFNs) and a modified TOPSIS method tailored for the IVHFF environment. Practical examples and result analysis are provided in Section 4, showcasing the application of the framework. The final section concludes the research by summarizing the key findings, offering insights, and proposing directions for future studies.

2. Related Work

2.1. Literature Review on MCDM Methods for GAI Chatbot Evaluation

GAI chatbots, despite being a relatively recent development, have garnered significant attention in both academic research and practical applications. Approaches to their study vary widely: Some researchers focus on technical aspects, offering descriptive or general analyses that often emphasize feature comparisons while omitting advanced computational methods. Conversely, other studies adopt modern model-driven techniques, such as machine learning, optimization, and MCDM methods.

MCDM methods present distinct advantages in the evaluation and selection of AI chatbots. One key benefit is that they do not rely on extensive datasets or computationally intensive procedures, making them accessible and efficient. These methods simplify the decision-making process by facilitating comprehensive evaluations across multiple criteria, ensuring objectivity through a systematic analysis of both the criteria and stakeholder preferences.

Additionally, MCDM approaches are well-suited for diverse decision-making scenarios and can manage the complexities inherent in chatbot evaluations. By incorporating stakeholder preferences, these methods enable informed decision making and improve the likelihood of selecting the most appropriate chatbot for a given context.

Drawing on data from previous studies, interviews, questionnaires, and surveys, Chakrabortty et al. [15] constructed a comparison matrix with eight alternatives and nine criteria: empathy, engagement, tangibility, assurance, reliability, satisfaction, responsiveness, speed, and security. These criteria were derived from established service quality models alongside AI- and chatbot-specific considerations. A survey was conducted to gather expert opinions and the single-valued neutrosophic (SVN) analytic hierarchy process (AHP) was employed to determine their relative weights. The combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) method was then used within the SVN environment to rank the options, ultimately identifying the optimal chatbot.

Santa Barletta et al. [16] proposed a novel clinical chatbot selection model using the AHP technique, assessing chatbot assistants based on the “Quality in Use” concept from the ISO/IEC 25010 standard [17]. Two healthcare-oriented chatbots were evaluated against five criteria groups: effectiveness, efficacy, satisfaction, freedom from risk, and context coverage across three dimensions—providing information, prescriptions, and process management.

Singh et al. [18] identified twelve acceptance factors for conversational digital assistants (CDAs) through a literature review and expert input. These factors were analyzed for their cause-and-effect relationships using the grey-DEcision-MAking Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) method. The study highlighted key causal factors, including humanness, social influence, social presence, social capability, and ease of use, which significantly impact CDA adoption and provide insights for managerial and policy decisions in online shopping contexts.

Pandey et al. [19] addressed concerns about the impact of GAI tools, particularly ChatGPT, by examining twelve challenges related to its adoption. These challenges were analyzed using the intuitionistic fuzzy DEMATEL approach, which proved more effective than classical and fuzzy DEMATEL methods in terms of mean absolute error (MAE). By categorizing challenges into cause-and-effect relationships, the study provides valuable guidance for experts and project managers in identifying areas for improvement.

Pathak and Bansal [20] mapped twenty factors to the Technology–Organization–Environment–Individual (T-O-E-I) framework, derived from the Technology–Organization–Environment (T-O-E) and Human–Organization–Technology fit (H-O-T fit) frameworks. After ranking these factors, the global ranking was computed using the rough stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis method (R-SWARA). The top seven factors included perceived benefits of AI, AI system capabilities, organizational data ecosystem, perceived compatibility of AI systems, ease of use, IT infrastructure, and top management support. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of these rankings.

Wiangkham and Vongvit [21] applied both MCDM and artificial neural network (ANN) methods to prioritize factors influencing ChatGPT adoption in higher education. Fourteen criteria were grouped into usage-, agent-, technical- and trust-related categories. Using a Likert-scale questionnaire, criteria importance was assessed, and weighted sum model (WSM) and ANN methods were applied, alongside SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME). The study systematically prioritized factors affecting ChatGPT adoption.

Ojo et al. [22] employed a fuzzy TOPSIS-based method to evaluate six AI alternatives for mental health treatment planning: rule-based systems, logistic regression, neural networks, evolutionary algorithms, hybrid models, and benchmark algorithms. The evaluation considered criteria such as privacy protection, treatment effectiveness, explainability, healthcare costs, regulatory compliance, and ethical implications. Rule-based systems and benchmark algorithms emerged as the preferred approaches.

The key characteristics of the methodologies used to investigate factors influencing the selection and ranking of conversational digital assistants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing studies on chatbots evaluation and ranking.

After analysis of previous studies on GAI chatbot selection, we categorize them based on their distinctive features. According to the specificity of input data, the utilized models can be divided into two groups: crisp and fuzzy estimates. The crisp group, exemplified by Santa Barleta et al. [16] and Wiangkham and Vongvit [21], is designed for arithmetic calculations and distance metrics using precise input values. In contrast, the fuzzy group includes multi-criteria methods operating in various fuzzy environments, as demonstrated by Chakrabortty et al. [15], Singh et al. [18], Pandey et al. [19], Pathak and Bansal [20], and Ojo et al. [22].

In terms of complexity, existing models can be classified into single and hybrid multi-criteria techniques. Single methods, used by Singh et al. [18], Pandey et al. [19], Pathak and Bansal [20], Wiangkham and Vongvit [21], and Ojo et al. [22], apply only one MCDM method. Hybrid approaches, employed by Chakrabortty et al. [15] and Santa Barleta et al. [16], combine two methods: one for determining relative criteria weights and another for ranking alternatives.

The literature review reveals the absence of a universal approach for addressing the GAI chatbot selection problem. While previous studies offer valuable insights into comparing conversational chatbots, they exhibit several shortcomings:

- Lack of holistic multi-criteria solutions: Many proposed solutions focus on specific aspects, such as determining the relative importance of features within the criteria system [18,19,20,21] or generating chatbot rankings using a single multi-criteria method [15,22];

- Limited handling of inaccurate attribute estimates: Few studies, such as those by Chakrabortty et al. [15], Pandey et al. [19], and Ojo et al. [22], effectively address imprecise attribute estimates. Since AI chatbot evaluations often depend on subjective factors, assessments should involve expert groups utilizing classic fuzzy numbers or their advanced variants;

- Non-iterative fuzzy solutions: Existing fuzzy methodologies typically implement only one or two MCDM methods in a single, non-iterative procedure.

Evaluation should adopt a holistic process that considers various factors, including technological, economic, and organizational parameters, which are often expressed through imprecise, unclear, and uncertain estimates. To address these drawbacks, we propose a new fuzzy methodology for GAI chatbot selection.

Selecting a specific chatbot assistant aligned with organizational strategies or individual preferences is a complex process influenced by numerous factors. At the organizational level, the preferred intelligent chatbot depends on considerations such as data security requirements, regulatory compliance, subscription costs, and seamless integration with existing systems. At the individual level, preferences may be shaped by use cases, ease of use, domain-specific capabilities, or community recommendations and reviews. The optimal solution is the GAI chatbot that best meets the requirements of the organization or the preferences of the individual user.

2.2. Chatbot Evaluation Criteria

Despite the availability of practical tools and platforms for chatbot benchmarking and user testing—such as those offered by Hugging Face, Chatbot Arena (formerly LMSYS) [23], and Artificial Analysis [24]—these solutions often lack the flexibility needed to accommodate specific study goals and use cases. Evaluating GAI chatbots requires a systematic approach that integrates diverse attributes to address their multifaceted roles and applications.

In this subsection, we review the criteria proposed in prior studies to identify relevant attributes for developing a multi-attribute evaluation system specifically tailored to GAI chatbots.

The literature review reveals that previous studies on developing multi-criteria systems for evaluating GAI chatbots have primarily adopted a combined approach, integrating multiple criteria, indices, and metrics derived from various theoretical models and software quality standards.

For example, Chakrabortty et al. proposed a system based on nine criteria: security, speed, responsiveness, satisfaction, reliability, assurance, tangibility, engagement, and empathy. These criteria were drawn from SERVQUAL [25] (responsiveness, reliability, assurance, tangibility, and empathy), ISO/IEC 25010 [17] (security and speed), the technology acceptance model (TAM) [26] (engagement), and customer experience theory [27] (satisfaction) [15].

Santa Barleta et al. focused on five criteria groups: effectiveness, efficacy, satisfaction, freedom from risk, and context coverage. These were derived from ISO/IEC 25010 [17] and applied across three functional dimensions [16].

Singh et al. [18] developed a system incorporating 12 criteria, including social influence, enjoyment, performance, ease of use, usefulness, trust, and privacy risk, based on TAM [26] and UTAUT [28].

Pandey et al. [19] introduced 12 evaluation criteria emphasizing ChatGPT-related issues such as hallucination, bias, proprietary LLMs, ethical implications, and broader AI-related problems.

Pathak and Bansal [20] utilized the T-O-E-I framework [29,30], organizing criteria into four groups: technology (seven criteria), organization (six), environment (three), and individual (four).

Wiangkham and Vongvit [21] adopted a system comprising usage (four criteria), agent (three), technical (four), and trust-related (three) categories, primarily based on TAM and UTAUT.

Ojo et al. [22] focused on six criteria: privacy protection, treatment effectiveness, explainability, costs, regulatory compliance, and ethical implications. These criteria, designed for evaluating medical chatbots, stem from healthcare technology frameworks, ISO standards, AI ethics, and health economics models. Their system ensures that medical chatbots are safe, effective, transparent, and legally compliant while addressing critical aspects such as patient data security, cost effectiveness, and ethical concerns.

The compared evaluation systems for GAI chatbot selection emphasize a multi-criteria approach, integrating elements from SERVQUAL framework, ISO standards, TAM, UTAUT, and AI ethics models. These assessment indices are designed to address specific contexts, including functionality, user experience, and ethical considerations, enabling effective comparisons by evaluating both technical capabilities and societal impacts.

However, existing evaluation systems have limitations, including their domain-specific focus, insufficient attention to rapidly evolving GAI challenges, and reliance on subjective criteria weighting. To address these gaps, we developed a GAI chatbot evaluation system, ensuring a comprehensive and holistic evaluation approach.

The proposed system includes four key criteria: conversational ability, user experience, integration capability, and price:

- Conversational ability evaluates the chatbot’s capacity to understand and generate natural language responses, ensuring context-aware, coherent, and human-like interactions;

- User experience measures ease of use, intuitiveness, and satisfaction, focusing on design, accessibility, and the chatbot’s ability to meet user needs effectively;

- Integration capability assesses how seamlessly the chatbot integrates with existing tools, platforms, or workflows, enhancing usability and productivity;

- Price considers the affordability of the chatbot, evaluating its cost relative to its features, functionality, and overall value.

Our evaluation system aligns with the TAM [26] and UTAUT [28] models. Conversational ability corresponds to perceived ease of use in TAM and performance expectancy in UTAUT, reflecting user expectations for accurate, natural communication. User experience relates to perceived usefulness and effort expectancy, where intuitive and enjoyable interactions drive adoption. Integration capability aligns with facilitating conditions in UTAUT and external variables in TAM, as compatibility with existing systems enhances utility. The price criterion captures the cost–value relationship, where users weigh the chatbot’s cost against its utility and benefits.

TAM- and UTAUT-based indicators have been preferred because they effectively capture user perceptions and behavioral intentions towards adopting GAI chatbots across diverse contexts. Their theoretical foundations and empirical validation make them more reliable measures than those from other existing approaches.

The new chatbot evaluation system adopts a combined approach by integrating factors from two widely used theoretical models. This multidimensional system provides a complex assessment that addresses functional, experiential, technical, and economic dimensions. By tailoring it to the specific requirements of corporate and individual users, our approach ensures an effective evaluation of chatbots across varied use cases and priorities.

2.3. State-of-the-Art of the Most Widely Used GAI Chatbots

In this subsection, we present a comparative overview of the most popular GAI chatbots recognized by the global AI community for their transformative role in enhancing human–machine interaction: ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude, and Perplexity AI.

OpenAI ChatGPT (https://chatgpt.com, accessed on 29 January 2025) is a state-of-the-art GAI chatbot renowned for its advanced conversational capabilities. Powered by generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) models, it excels in understanding users’ requests and generating human-like responses, making it suitable for a wide range of applications, from casual conversations to professional tasks. The chatbot’s intuitive interface and versatility have made it widely adopted. It offers features like text summarization, content generation, and creative writing. Available in free and premium versions, ChatGPT is accessible to individuals, educators, and businesses alike [31]. Recent enhancements include the launch of ChatGPT Pro, which provides unlimited access to advanced models such as GPT-o1 and GPT-4o, along with features like Advanced Voice Mode. OpenAI has also expanded ChatGPT’s functionality to include web-based search capabilities for up-to-date information. Additional updates include the introduction of the Projects tool, which simplifies managing multiple chats and group files, and Canvas, an interface for collaborative writing and coding.

Microsoft Copilot is a GAI-powered assistant integrated into the Microsoft 365 ecosystem, designed to enhance productivity across office tools. Built on OpenAI’s LLM models, it provides contextual suggestions, automates repetitive tasks, and supports content generation tailored to user needs [32]. Recent updates include general availability for Microsoft 365 Copilot, the introduction of Windows Copilot with OS integration, enhancements to GitHub Copilot (Copilot Chat), and ongoing improvements in Microsoft products like Dynamics 365 and the Power Platform. These updates offer intuitive assistance with writing code, analyzing data, generating content, and automating routine tasks.

Google Gemini (https://gemini.google.com, accessed on 29 January 2025), formerly Bard, is a GAI chatbot that combines conversational AI with the capability of using Google’s search engine. It delivers accurate, contextually relevant answers and supports tasks such as brainstorming, drafting, and question answering. Integrated into Google’s ecosystem, Gemini works with tools like Google Workspace, making it a reliable assistant for personal and professional use [33]. Recent advancements include access to experimental models like Gemini Exp-1206, designed for complex tasks such as coding, solving mathematics problems, reasoning, and instruction following. The Gemini 2.0 Flash model improves academic benchmarks and speed, while Gemini Deep Research offers a personal research assistant capable of generating comprehensive reports. Additionally, new Gems for Google Workspace enhance workflow efficiency, and the Gemini app now provides enterprise-grade data protection for business and education customers.

Anthropic Claude (https://claude.ai, accessed on 29 January 2025) is an AI chatbot designed to deliver safe, ethical, and contextually aware conversations. Claude handles complex queries and supports tasks like content creation and data analysis for personal and professional use. Its user friendliness and accessibility have made it popular, especially in educational and research settings [34]. In 2024, Anthropic introduced the upgraded Claude 3.5 Sonnet model, enhancing capabilities in coding, reasoning, and instruction following. The Claude 3.5 Haiku model offers state-of-the-art performance with improved speed and affordability. Additionally, a new “computer use” feature enables Claude to interact with computer interfaces, automating tasks by simulating human actions like moving a cursor, clicking UI buttons and typing text.

Perplexity AI (https://www.perplexity.ai/, accessed on 29 January 2025) is a search-driven chatbot that combines GAI with real-time information retrieval to generate concise and accurate answers. Known for its minimalistic interface and focus on transparency, Perplexity is relatively inexpensive, making it appealing to individuals and small organizations. Although it lacks deep integration capabilities, it emphasizes precision and real-time information [35]. Recent updates include Internal Knowledge Search, allowing Pro and Enterprise Pro users to search public web content and internal knowledge bases simultaneously, and Spaces, an AI-powered collaboration hub for organizing research, connecting internal files, and customizing AI assistants for specific tasks, enhancing teamwork and productivity.

These five chatbots demonstrate the diverse capabilities of GAI technology, excelling in areas such as professional productivity, ethical AI, real-time information, and integration. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the utilized LLMs, functionality, applicability, integration capability, real-time access, and pricing for these leading GAI chatbots.

Table 2.

Comparison of the most widely used GAI chatbots.

According to the collected data (Table 2), the five GAI chatbots demonstrate unique strengths and capabilities tailored to diverse user needs.

ChatGPT offers a context window of up to 128 K tokens, making it suitable for tasks requiring extended interactions. Its features include web browsing, code execution, image generation, and the ability to create custom GPTs for tailored applications. This makes ChatGPT particularly suited for content creation, coding assistance, and data analysis within flexible and interactive use cases.

Copilot, integrated within Microsoft’s ecosystem, shares similar context window capabilities with ChatGPT due to its foundation on the same model. Its strengths lie in coding assistance, task automation, and seamless integration with Microsoft Office applications. This tight integration makes it a powerful productivity tool for users working within Microsoft’s suite of tools, offering efficiency for enterprise and professional workflows.

Gemini excels in processing multimodal data and handling extensive context, with the ability to manage up to 1 million tokens. This capability positions it as a leader for tasks involving large datasets, advanced reasoning, and integration with Google services. Its rapid processing and support for multimodal data, combined with Google Workspace integration, make it particularly strong in professional and research-oriented environments.

Claude, with a context window of approximately 200 K tokens, is ideal for tasks requiring extensive document processing and in-depth analyses. Its emphasis on safety, ethical considerations, and privacy measures positions it as a preferred choice for applications where ethical AI use and robust security are critical, particularly in education, research, and data-sensitive industries.

Perplexity, with a context window of around 131 K tokens, is designed for quick information retrieval and concise answers. Its focus on real-time web search capabilities and user-friendly interfaces makes it highly effective as an AI-powered search assistant, catering to users who prioritize fast, precise, and up-to-date information.

In summary, while all five chatbots are effective tools for various AI-driven tasks, their features and strengths vary depending on the specific application. Copilot and Gemini are well suited for tasks that require integration within specific ecosystems, such as Microsoft Office and Google Workspace. Claude is best suited for applications requiring extensive context windows, with a strong emphasis on safety, ethics, and privacy. Perplexity excels in quick information retrieval and concise, accurate responses. ChatGPT and Copilot offer greater versatility with features like image generation and internet access, making them valuable for diverse use cases. On the other hand, Gemini, Claude, and Perplexity provide larger context windows and more affordable API access, catering to users with specific technical or budgetary requirements.

Given the rapidly evolving nature of the GAI chatbot field and the continuous emergence of new players, our review represents only a snapshot of the current landscape.

3. Methodological Framework for GAI Chatbot Selection

This section outlines the theoretical foundations of interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy numbers (IVHFFNs), introduces a modified TOPSIS approach utilizing IVHFFNs, and proposes a conceptual framework for decision analysis of GAI chatbot data.

To address the challenge of GAI chatbot selection, we employed the classic Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [36], complemented by recently developed fuzzy sets modification. As a distance-based multi-criteria decision-making method, TOPSIS determines the relative closeness of each alternative to the ideal solution (best outcome) and the anti-ideal solution (worst outcome) for each criterion. The alternative with the highest coefficient of relative proximity to the ideal solution is selected as the most suitable.

3.1. Interval-Valued Hesitant Fermatean Fuzzy Numbers: Some Basic Definitions and Operations

To enhance the TOPSIS methodology, we integrate interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy sets (IVHFFSs) [14]. This subsection provides an overview of the key concepts and arithmetic operations associated with IVHFFNs, which are essential for implementing this modification.

IVHFFSs extend earlier models such as interval-valued fuzzy sets (IVFSs) (1975) [37], hesitant fuzzy sets (HFSs) (2010) [38] and Fermatean fuzzy sets (FFSs) (2020) [39]. Represented in a three-dimensional space, IVHFFSs use interval values within the range [0, 1] to describe the belongingness degree (BD), non-belongingness degree (NBD), and indeterminacy degree. A notable feature of IVHFFSs is the use of interval values for BD and NBD, with the constraint that the cube of the upper bounds for these intervals must not exceed 1. Compared to FFSs, IVHFFSs provide a more complex representation of uncertainty.

When crisp BD and NBD values are challenging to obtain—due to imprecise or uncertain data—IVHFFNs, with their interval-valued flexibility and the ability to accommodate multiple intervals, offer a practical solution for decision makers and researchers. This flexibility ensures more accurate assessments of alternatives in situations where precise evaluations are unattainable.

In this section, some basic concepts of IVHFFSs are described.

Definition 1

([14]). The IVHFFS in a universe is defined by the following:

The pair ( is called an interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy number (IVHFFN), denoted by .

Definition 2

([14]). Suppose that is an IVHFFN. Then, the score function s for can be defined as follows:

The larger the score value , the greater the IVHFFN .

Since , an improved score function for an IVHFFN in described in the following definition:

Definition 3

([14]). Assume is an IVHFFN. Then, an improved score function is defined by the following:

In case of different numbers of intervals in BD and NBD of an IVHFFN, a preprocessing step should be added. We assume to add the mean value of BD or the NBD for given object.

The arithmetic operations on IVHFFNs are given by the next definition.

Definition 4

([14]). Let and

be two IVHFFNs. Then, we have the following:

Definition 5.

(Based on [14]) Let and be two IVHFFNs. Then, the distance between and is defined as follows:

Definition 6

([14]). Let (i = 1, 2, …, m) be a collection of IVHFFNs and such that ; then, an interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy weighted average (IVHFFWA) operator is used to map :

Specifically, if

, then the IVHFFWA operator is converted into the following formula:

In summary, the space of interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy numbers (IVHFFNs) is broader than that of interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy numbers (IVFFNs). With a less restrictive constraint, IVHFFSs provide greater precision in addressing complex and uncertain MCDM problems compared to IVFFSs.

3.2. TOPSIS in IVHFFNs Environment

TOPSIS evaluates alternatives by measuring their closeness to an ideal solution and their distance from a negative-ideal solution. To adapt this method for IVHFFNs, we propose calculating the distances between alternatives using Equation (5). The pseudocode for the modified TOPSIS approach within the IVHFFN framework is presented in Algorithm 1.

Let represent the given set of alternatives, denote the set of identified criteria for A evaluation, and be the set of relative weights of criteria C.

| Algorithm 1. IVHFFNs TOPSIS. |

| Step 1. Gather the linguistic evaluations provided by expert k in the decision matrix |

| , |

| where K is the number of experts. Convert the X matrices into values represented by IVHFFNs values. |

| Step 2. Compute the aggregated matrix for all experts according to Equation (9). Assume equal weighting for all experts (1/K) and apply the averaging formula provided: |

| . |

| Step 3, while the remaining criteria are categorized as benefit criteria and denoted by 𝔹. |

| Step 4 using its score function as described in Equation (3): |

| Step 5. Derive the weighted values of assessments for each criterion: |

| according to Equation (6). |

| solutions for each criterion: |

| ). |

| Step 7. Measure the distances from each alternative to the ideal and negative ideal solutions using Equation (8): |

| Step 8. Calculate the coefficients of relative closeness of each alternative to the ideal solution: |

| . |

Order the alternatives in descending order based on their coefficients of relative closeness to the ideal solution and select the alternative with the highest coefficient as the optimal choice.

The proposed modification of TOPSIS integrates a new flexible IVHFFNs distance metric from Equation (8). Unlike standard Fermatean fuzzy numbers, which operate within a three-dimensional (3D) space, or IVFFNs, which utilize three 3D intervals to define the membership, non-membership, and hesitancy degrees, IVHFFNs introduce an even more complex structure. Specifically, they allow for different numbers of intervals to define the belongingness and the non-belongingness degrees. The increased flexibility in representing uncertainty results in a more accurate evaluation of alternatives.

However, the proposed new TOPSIS extension in IVHFF environment has a higher time complexity compared to its counterparts using crisp, classical, or other fuzzy models, including IVFFNs. This increased complexity arises from more intricate arithmetic operations, computationally intensive distance metric calculations, and the evaluation of multiple interval-based values in the score function.

Nevertheless, the tradeoff between more accurate representation and increased time complexity is justified, as these advanced 3D fuzzy numbers enable a more precise depiction of uncertainty in alternative evaluations.

3.3. Theoretical Framework for GAI Chatbot Selection

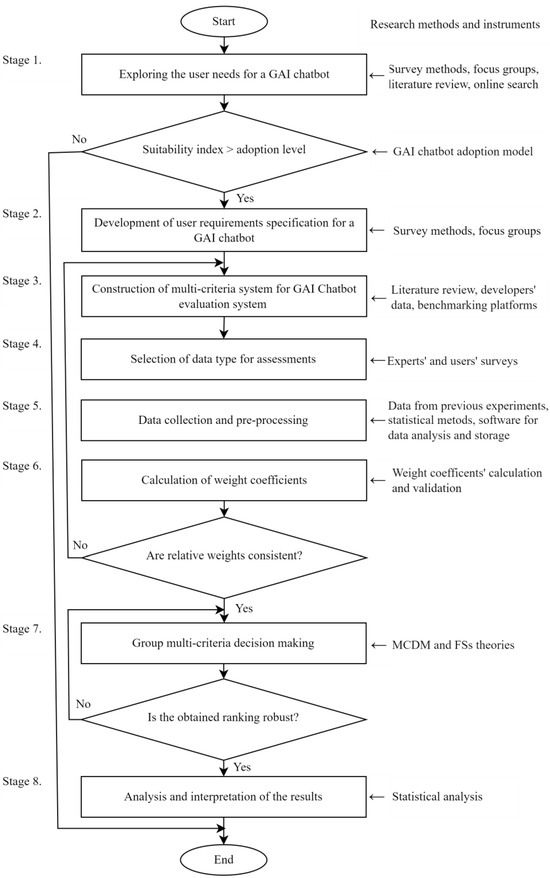

Selecting an appropriate generative AI (GAI) chatbot involves a structured, multi-stage decision-making process to ensure alignment with organizational needs and user expectations. The new framework for unified decision analysis of GAI chatbot data consists of eight stages (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flowchart of proposed framework for decision analysis of GAI chatbots.

- Stage 1: Needs Assessment

The decision-making process begins with clearly identifying the specific requirements and expectations for a GAI chatbot. This involves collecting data on available chatbots and understanding the current state of chatbot technology. Relevant information can be gathered from industry reports, user reviews, and technical specifications. The goal is to determine which chatbots are available, their capabilities, and how well they align with the organization’s needs. If the assessment confirms a need for a GAI chatbot, the process advances to the next stage.

- Stage 2: User Requirements Specification

In this stage, surveys or interviews are conducted to collect feedback from potential users about their expectations and preferences. This input helps define the desired features and functionalities of the chatbot, such as natural language understanding, integration capabilities, and user interface design.

- Stage 3: Development of Evaluation Criteria

A multi-criteria evaluation system is created to facilitate a systematic comparison of chatbots. This system is based on user requirements and the organizational importance of specific chatbot features. Key criteria may include technological specifications, ease of integration, user friendliness, scalability, and cost.

- Stage 4. Selection of data types

The choice of data types and decision-making methods depends on the resources available and the data collected in Stage 3. If resources are limited, decision makers may select traditional data types and algorithms with lower computational complexity, respectively. For more precise results, advanced data types and MCDM methods can be employed, though they may require greater resources. Data collection methods may include expert evaluations, user testing, and market analysis.

- Stage 5. Data reprocessing and storage

The collected data are processed and stored appropriately for further analysis. This step includes coding qualitative assessments into numerical forms, identifying and resolving duplicates or errors, addressing missing values, and ensuring overall data integrity. Once processed, the data are stored in a database or dataset for subsequent stages.

- Stage 6. Determination of criteria weights

Based on the evaluation criteria and collected data, weight coefficients are assigned to each criterion to reflect their relative importance. These weights can either be predetermined or calculated using methods such as AHP or other weighting techniques.

- Stage 7. Multi-criteria analysis

In this stage, the MCDM algorithm is applied to rank chatbot alternatives according to the weighted criteria. Using multiple MCDM methods or hybrid combinations can yield a more robust and comprehensive analysis.

- Stage 8. Results analysis and interpretation

Decision makers analyze the rankings to identify the top chatbot alternatives. If the highest-ranked option satisfies organizational requirements, it is selected. If not, additional data may be collected and the process iterated from Stage 4. The final selection should align with long-term organizational goals and user expectations.

This structured approach ensures a comprehensive and objective selection process for GAI chatbots, customized to meet specific organizational needs.

4. A Case Study of Quality-Based Evaluation of GAI Chatbots

Let S be an organization faced with a GAI chatbot selection problem. The benefits of implementation of a GAI chatbot in the workflow of Organization S are numerous. The problem is how to find the best GAI chatbot for the organizational specifics.

The execution of Stage 1 of the proposed framework shows that there are several available GAI chatbots, and the process of chatbot selection can start. In this illustrative example, we utilize our own chatbot dataset, collected from benchmarking websites such as [23]. The dataset consists of four assessment criteria, namely (Section 2.2), and five GAI chatbots, namely (Section 2.3). The criteria are related to the following aspects of GAI chatbot features: —conversational ability, —user experience, —integration capability, and —price. The GAI chatbots are as follows: —ChatGPT, —Copilot, —Gemini, —Claude, and —Perplexity.

In Stage 2, experts from Organization S fill in the questionnaire about their GAI chatbot requirements. Respondents evaluate the chatbot features via a five-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely important” (corresponding to 5) to “unimportant” (corresponding to 1).

In the next stage, experts from Organization S complete a questionnaire outlining their requirements for generative AI (GAI) chatbots. Participants assess the chatbot features using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “unimportant” (1) to “extremely important” (5).

In Stage 3, a multi-attribute criteria index is developed, consisting of variables:

In the next stage, decision makers decide that the data type is IVHFFNs and employ the proposed new IVHFFNs TOPSIS modification. The values of the decision matrix are converted into five-point Likert scale (Table 3). For transforming every linguistic variable into its corresponding IVHFFNs, the conversion table (Table 4) is applied.

Table 3.

Input decision matrix for GAI chatbots selection.

Table 4.

Linguistic variables and their corresponding IVHFFNs.

In Stage 5, we decide that the data type is IVHFFNs and implement the proposed IVHFFNs TOPSIS modification. The decision matrix values are converted into linguistic variables as shown in Table 3. Each linguistic variable is then transformed into its corresponding IVHFFN using the conversion rules provided in Table 4.

The weight coefficients for the criteria are equal, such that .

The overall scores and rankings of given GAI chatbots obtained by using IVHFFNs and crisp TOPSIS method are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Scores and their corresponding rankings: TOPSIS method in IVHFFNs.

The problem was also solved using several other MCDM methods (Table 6)—weighted sum method (WSM), triangular fuzzy numbers’ (TFNs) WSM, evaluation based on distance from average solution (EDAS), and TOPSIS. In order to show that the IVHFF TOPSIS solution is feasible, we compare the obtained ranking with those obtained with crisp and triangular fuzzy estimates.

Table 6.

Overall scores and their corresponding ranking.

The final rankings are as follows:

WSM (Benchmarking method): A1A2A3A4A5.

TFNs WSM: A1A3A2A4A5, .

EDAS: A1A3A2A5A4, .

TOPSIS: A1A2A3A4A5, .

IVFFNs TOPSIS: A1A2A3A4A4, .

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the agreement between the benchmark ranking (WSM) and the rankings produced by other four MCDM methods. The analysis demonstrated high reliability of the alternative methods, with TFNs WSM and TOPSIS both achieving a Spearman’s ρ of 95% and EDAS reaching a ρ of 85%. These substantial correlation coefficients of the proposed IVHFFNs TOPSIS () confirm that the proposed method aligns closely with the benchmark and alternative methods, ensuring dependable and consistent ranking outcome.

Analysis of the obtained rankings categorizes the GAI chatbots into two primary groups.

Group 1 (leading GAI chatbots) includes the leading GAI chatbots: ChatGPT (A1), Copilot (A2), and Gemini (A3). ChatGPT consistently secures the top position across all methods, highlighting its superior conversational ability (C1) and robust user experience (C2). Copilot and Gemini follow closely, demonstrating strong performance in integration capability (C3) and competitive price (C4). While Gemini maintains a comparable standing in most methods, Copilot showcases enhanced strengths in specific criteria, particularly in integration capability.

Group 2 (lower-ranked GAI chatbots), with Claude (A4) and Perplexity (A5), consistently occupy the lower ranks across all methods. Claude exhibits moderate performance but lags in conversational ability (C1), user experience (C2), and integration capability (C3), whereas Perplexity AI falls behind primarily due to its less competitive integration capability (C3).

The ranking analysis across multiple MCDM methods consistently identifies ChatGPT as the leading AI chatbot, followed by Copilot and Gemini. Claude and Perplexity are positioned in the lower tier, highlighting the need for further enhancements to improve their performance in areas such as conversational ability, user experience, and integration capability. The high correlation coefficient shows the robustness of the proposed TOPSIS modification, ensuring that the ranking reflects the underlying performance metrics.

Based on the real-life characteristics of the compared GAI chatbots, the final ranking is adequate. ChatGPT (A1) stands out with its strong conversational abilities, high user satisfaction, and versatile integration options, which is further supported by its extensive real-world adoption and positive user feedback. Copilot (A2) also offers robust capabilities, particularly in development-oriented tasks, while retaining reasonable usability and pricing. Gemini (A3), although relatively new and not widely available, is expected to provide advanced conversational features in line with its strong technological backing, albeit with moderate integration and a lower price point than ChatGPT (A1) or Copilot (A2). Claude (A4), known for producing safer, more controlled outputs, and Perplexity (A5), valued for its quick question-answering style, both serve specific niches; their medium-to-lower scores in conversational ability and integration reflect these narrower focuses compared to ChatGPT (A1) and Copilot (A2). Consequently, the observed ordering is consistent with the advantages, target markets, and limitations of these chatbots.

It can be concluded that the proposed framework is reliable and properly reflects the requirements of organization S.

Selecting the appropriate chatbot is crucial for enhancing user engagement and operational efficiency. To streamline this selection process, a comprehensive approach is essential. This methodology enables experts to evaluate various technological, integration, and performance characteristics; establish specific requirements; utilize fuzzy assessments; and objectively identify the most suitable chatbot for a particular organization. Decision makers can further refine the evaluation system by incorporating factors such as anticipated interaction volumes, scalability, maintenance and support, error handling and recovery, and customization capabilities.

The proposed methodology offers benefits to both end users and organizational decision makers. For end users, aligning chatbot functionalities with user preferences and requirements enhances satisfaction and engagement. A chatbot selected through this process delivers precise and efficient assistance, thereby elevating the overall user experience. For organizational decision makers, the new MCDM approach provides a clear and unbiased framework for evaluating chatbots against the organization’s strategic goals and operational needs. This leads to informed investment choices and the smooth integration of AI technologies into business processes.

5. Conclusions

The rapid advancement of LLMs has significantly increased the prominence of GAI chatbots in various sectors. Many organizations are integrating these conversational assistants into their workflows to enhance workflow efficiency and user engagement. However, there is currently no unified algorithmic approach for selecting suitable intelligent assistants.

In response to this challenge, we developed an integrated framework for GAI chatbot selection. This framework introduces an extension of TOPSIS within an IVHFFNs environment, enabling objective evaluation of generative chatbots. The fuzzy nature of this method effectively addresses uncertainty and vagueness in expert assessments. Moreover, the framework is versatile, accommodating both single and repeated data processing for chatbot selection.

The key advantages of the IVHFF TOPSIS include the following:

- Incorporation of several interval-valued membership and non-membership grades, along with interval-valued hesitancy degrees in the evaluation process;

- Integration of Minkowski distance-based family of metrics, enabling flexible and accurate distance calculations tailored to various data types;

- Consideration of the lengths of belongingness, non-belongingness, and hesitancy intervals in distance calculations, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of each criterion’s impact.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of this new framework, we applied it to a practical scenario involving the selection of five GAI chatbots: ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini (formerly Bard), Claude, and Perplexity. To capture the performance of the chatbots, we selected four critical criteria that align with user needs and technological capabilities. The analysis of the results indicates that the new methodology reliably reflects the features of the chatbots in the final rankings.

This evaluation process can be conducted periodically to account for the rapid advancements in GAI technologies and the evolving needs of organizations. Implementing an iterative procedure allows for continuous refinement of the selection criteria and adaptation to new developments, ensuring that the chosen chatbot solutions remain optimal over time.

In future work, we aim to enhance this conceptual framework by integrating recently developed multi-criteria decision-making methods. Additionally, we intend to develop a new hybrid method for chatbot evaluation that combines innovative weight determination algorithms with advanced multi-criteria decision-making techniques. We also plan to expand the ranking mechanism to address uncertainties using various classic and interval fuzzy sets, including interval type-3 and T-spherical fuzzy numbers. Furthermore, we acknowledge the limitation of assuming equal-weighted coefficients in the current study and plan to refine this aspect by incorporating adaptive weighting mechanisms in our future research.

Funding

This research was partially funded the Ministry of Education and Science and by the National Science Fund, co-founded by the European Regional Development Fund, Grant No. BG05M2OP001-1.002-0002 and BG16RFPR002-1.014-0013-M001 “Digitization of the Economy in Big Data Environment”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the academic editor and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Impact of artificial intelligence in travel, tourism, and hospitality. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1943–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Obaid, A.J.; Bhushan, B.; Rajest, S.S. (Eds.) Advanced Applications of Generative AI and Natural Language Processing Models; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amin, M.; Ali, M.S.; Salam, A.; Khan, A.; Ali, A.; Ullah, A.; Alam, M.N.; Chowdhury, S.K. History of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) Chatbots: Past, Present, and Future Development. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.05122. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.05122 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Yenduri, G.; Srivastava, G.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Jhaveri, R.H.; Wang, W.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Gadekallu, T.R. Generative pre-trained transformer: A comprehensive review on enabling technologies, potential applications, emerging challenges, and future directions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, A.; Taiwo, R.; Saka, N.; Salami, B.A.; Ajayi, S.; Akande, K.; Kazemi, H. GPT models in construction industry: Opportunities, limitations, and a use case validation. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 17, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Pandey, N.; Currie, W.; Micu, A. Leveraging ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications in the hospitality and tourism industry: Practices, challenges and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, R. From fiction to fact: The growing role of generative AI in business and finance. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2023, 21, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.; Yousefimehr, B.; Ghatee, M. Generative-AI in E-Commerce: Use-Cases and Implementations. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th CSI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP), Babol, Iran, 21–22 February 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Al Naqbi, H.; Bahroun, Z.; Ahmed, V. Enhancing Work Productivity through Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Chatbot Market Worldwide 2016–2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/656596/worldwide-chatbot-market/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Gartner. Gartner Says More Than 80% of Enterprises Will Have Used Generative AI APIs or Deployed Generative AI-Enabled Applications by 2026. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2023-10-11-gartner-says-more-than-80-percent-of-enterprises-will-have-used-generative-ai-apis-or-deployed-generative-ai-enabled-applications-by-2026 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Wang, K.; Ying, Z.; Goswami, S.S.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, Y. Investigating the role of artificial intelligence technologies in the construction industry using a Delphi-ANP-TOPSIS hybrid MCDM concept under a fuzzy environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, R.; Yenugula, M.; Algethami, H.; Alharbi, F.; Goswami, S.S.; Naveed, Q.N.; Zahmatkesh, S. Establishing the fuzzy integrated hybrid MCDM framework to identify the key barriers to implementing artificial intelligence-enabled sustainable cloud system in an IT industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.R.; Liu, P.; Rani, P. COPRAS method based on interval-valued hesitant Fermatean fuzzy sets and its application in selecting desalination technology. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 119, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabortty, R.K.; Abdel-Basset, M.; Ali, A.M. A multi-criteria decision analysis model for selecting an optimum customer service chatbot under uncertainty. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Barletta, V.; Caivano, D.; Colizzi, L.; Dimauro, G.; Piattini, M. Clinical-chatbot AHP evaluation based on “quality in use” of ISO/IEC 25010. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 170, 104951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/IEC. Systems and Software Engineering—Systems and Software Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE)—Product Quality Model; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/78176.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Singh, C.; Dash, M.K.; Sahu, R.; Singh, G. Evaluating Critical Success Factors for Acceptance of Digital Assistants for Online Shopping Using Grey–DEMATEL. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 8674–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Litoriya, R.; Pandey, P. Indicators of AI in Automation: An Evaluation Using Intuitionistic Fuzzy DEMATEL Method with Special Reference to Chat GPT. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 134, 445–465. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11277-024-10917-7 (accessed on 30 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Bansal, V. Factors Influencing the Readiness for Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Indian Insurance Organizations. In Transfer, Diffusion and Adoption of Next-Generation Digital Technologies; Sharma, S.K., Dwivedi, Y.K., Metri, B., Lal, B., Elbanna, A., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 698, pp. 384–397. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-50192-0_5 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wiangkham, A.; Vongvit, R. Comparative Analysis of MCDM Methods for Prioritizing Influential Factors of Chatgpt Adoption in Higher Education. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5040810 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Ojo, Y.; Davids, V.; Oni, O.; Odoemene, M.; Idowu-Collin, P.; Eyeregba, U. A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating the Use of AI for Matching Patients to Optimal Mental Health Treatment Plans. Read. Time 2024, 193, 201–222. Available online: https://worldscientificnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/WSN-1932-2024-201-222.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Chatbot Arena. Available online: https://lmarena.ai (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Artificial Analysis. Available online: https://artificialanalysis.ai/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, M.M.; Kuljis, J.; Papazafeiropoulou, A.; Stergioulas, L.K. An Evaluation Framework for Health Information Systems: Human, Organization and Technology-Fit Factors (HOT-Fit). Int. J. Med. Inform. 2008, 77, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Banerjee, J.S.; De, D.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Bhattacharyya, S. ChatGPT: A OpenAI platform for society 5.0. In Proceedings of the Doctoral Symposium on Human Centered Computing, Singapore, 25 February 2023; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 384–397. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J. An Introduction to Microsoft Copilot. In Copilot for Microsoft 365: Harness the Power of Generative AI in the Microsoft Apps You Use Every Day; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Saeidnia, H.R. Welcome to the Gemini era: Google DeepMind and the information industry. Library Hi Tech News, 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanshu, A.; Maurya, Y.; Hong, Z. AI Governance and Accountability: An Analysis of Anthropic’s Claude. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.01557. [Google Scholar]

- Deike, M. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT and Perplexity AI in Business Reference. J. Bus. Financ. Librariansh. 2024, 29, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications A State-of-the-Art Survey; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; Volume 186. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning—I. Inf. Sci. 1975, 8, 199–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torra, V. Hesitant fuzzy sets. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2010, 25, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Fermatean fuzzy sets. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).