Abstract

In recent years, intelligent driving has attracted more and more attention due to its potential to revolutionize transportation safety and efficiency, emerging as a disruptive technology that reshapes the future landscape of transportation. Environmental perception serves as the primary and fundamental cornerstone of intelligent driving systems. To address the intrinsic blind spots in environmental perception, this paper presents a vehicle collaborative perception approach based on Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) semantic communication. Specifically, a Transformer-based semantic segmentation technique is proposed for application to images acquired from surrounding vehicles and ground-based cameras. Subsequently, the generated semantic segmentation maps are transmitted via V2V/V2I communication. In the receiver, a semantic-guided image reconstruction technique based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) is developed to generate images with high realism. The generated Image images can be further fused with locally perceived data, facilitating intelligent collaborative perception. This method achieves effective elimination of blind spots. Furthermore, as only semantic segmentation maps—with a data size significantly smaller than that of raw images—are transmitted instead of the latter, it exhibits excellent adaptability to the dynamically time-varying characteristics of V2V/V2I channels. Even in poor channel condition, the proposed method maintains high reliability and real-time performance.

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of urbanization and the number of motor vehicles, road traffic safety has attracted more and more attention in recent years. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were an estimated 1.19 million road deaths in 2021, which is the leading cause of death for children and young people aged 5–29 years. And the global macroeconomic cost as high as 1.8 trillion US dollar, roughly equivalent to 10–12% of global gross domestic product (GDP).

Intelligent driving technology can significantly reduce traffic accidents and improve road safety through real-time perception and intelligent decision-making. Furthermore, it optimizes driving patterns, enhances traffic efficiency, and reduces vehicle energy consumption, representing a profound transformation in the transportation.

Nevertheless, developing reliable intelligent driving systems is still a significant technical challenge. The key constraint lies in that vehicles, as autonomous intelligent agents, are required to sequentially perform perception, prediction, decision-making, planning, and action execution in real-world operating conditions, with particular complexity arising in complex and dynamic urban road environments [1,2,3,4].

Among aforementioned challenges, the perception of the surrounding environment with high accuracy, robustness, and real-time performance is one of the most critical issues that need to be addressed in intelligent driving.

By leveraging computer vision and machine learning technologies, intelligent analysis is performed on images, videos, radar maps, and other data acquired by sensors in vehicles. This enables the perception and understanding of the surrounding environment, including the detection and recognition of vehicles, lanes, pedestrians, traffic signals, and road signs [5,6,7].

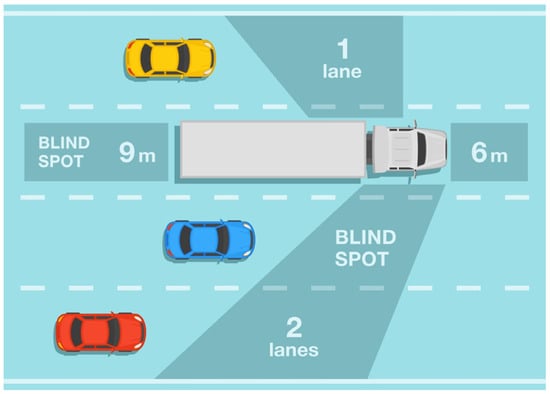

However, in real-world traffic scenarios, visual blind spots are inherently induced by the vehicle itself, surrounding vehicles, buildings, and other environmental elements—with a typical case being the blind spots of large vehicles illustrated in Figure 1. When vehicles, pedestrians, bicycles are located within these blind spots or suddenly emerge from them, the intelligent driving system may exhibit inadequate real-time responsiveness, thereby posing a significant risk of traffic accidents.

Figure 1.

The blind spot.

To enhance perception performance and overcome blind spots, current automotive manufacturers primarily eliminate blind spots by equipping vehicles with more cameras, radars, and other sensors. For instance, Tesla’s Autopilot—an advanced driving assistance system (ADAS)—employs eight cameras, while the Xiaomi SU7 is equipped with up to 27 perception sensors, including 11 high-definition cameras, 1 Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), 3 mm-wave radars, and 12 ultrasonic radars. By fusing information from multiple sensors, is improved. Fusing information from multiple sensors enables the exploitation of their complementary characteristics, mitigates the inherent limitations of individual sensors and improves the perception performance of the vehicles.

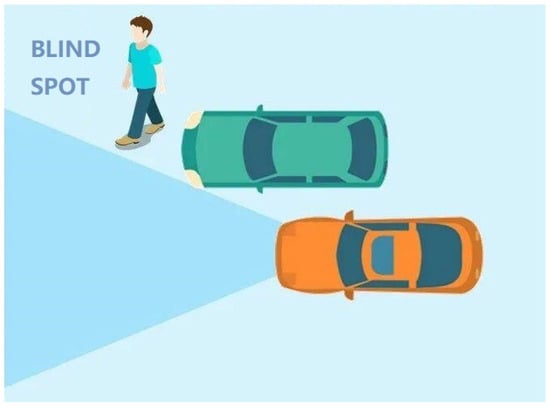

Nevertheless, this approach is only capable of mitigating the intrinsic blind spots caused by the vehicle itself at most, and fails to address those caused by adjacent vehicles and roadside infrastructure (e.g., buildings), shown as Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The blind spot caused by adjacent vehicles.

Alternatively, based on highly reliable, highly robust, and high-real-time Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) communication, a vehicle can receive images captured by cameras mounted on surrounding vehicles and ground infrastructure. By fusing these received images with those captured by its on-board cameras, the vehicle achieves collaborative environmental perception [8]. The collaborative perception approach can effectively eliminate perceptual blind spots in complex traffic environments, accurately perceive more occluded objects, and thereby further enhance driving safety while improving traffic operation efficiency.

Guiyang Luo et al. proposed a novel edge-assisted multi-vehicle perception system, EdgeCooper to enhance vehicles’ awareness over surrounding environments [9]. In EdgeCooper, vehicles share raw sensor data with an edge server using multi-hop cooperative 5G V2X communications, and merges vehicles’ individual views to form a holistic view with a higher resolution, thus enhances perception robustness and enlarging perception range.

Eduardo Arnold et al. proposed two schemes for cooperative 3D object detection, the early fusion scheme and the late fusion scheme [10]. Specifically, the early fusion scheme fuses point clouds acquired from multiple spatially distributed sensing perspectives prior to the 3D object detection process. In contrast, the late fusion scheme integrates the independently detected and generated bounding boxes from multiple spatially distributed sensors. Evaluation results demonstrate that the early fusion approach outperforms the late fusion approach by a significant margin, albeit at the expense of higher communication bandwidth.

Li, A. et al. developed a multiagent trajectory prediction model, named Multi-agent Trajectory Vector Transformer (MaTVT) based on Transformer architecture [11]. The test results demonstrated that MaTVT exhibit prominent prediction performance, revealing its superb accuracy, efficiency, and robustness.

However, this method requires extensive data interaction. According to statistics, the total data rate of multi-modal data collected by the sensors (e.g., cameras, LiDAR, and millimeter-wave radars) in a single autonomous vehicle exceeds 750 MB/s. Nevertheless, due to factors such as the blockage of Line-of-Sight (LoS), multipath propagation, and Doppler shift, the V2V/V2I channels exhibit significant dynamic characteristics. Thus, channel conditions may deteriorate severely.

Obviously, it is not feasible to directly transmit multi-modal data through V2V/V2I communication systems for interaction. To address this issue, this paper further proposes vehicle collaborative environmental perception technology based on semantic communication [12].

Unlike traditional communication (also known as syntactic communication), which focuses on efficiently and reliably symbol transmission, in the proposed method, the transmitter extracts semantic information from images via semantic segmentation technology and transmits it to surrounding vehicles through V2V/V2I communication. In the receiver, environmental perception can be directly conducted based on the received semantic information; alternatively, the original image can be realistically reconstructed with image generation technology based on the received semantic information. This approach accomplishes the task of vehicle collaborative perception with a substantially reduced number of transmitted symbols, rendering it particularly suitable for V2V/V2I scenarios—where communication bandwidth is limited, radio propagation conditions are complex, and channel characteristics exhibit dynamic variability.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows.

(1) This paper proposes a novel vehicle collaborative perception architecture based on semantic communication, which addresses the limitation of single-vehicle perception and further enhances driving safety.

(2) This paper constructs a Transformer-based semantic segmentation model for traffic scene images, which achieves high performance semantic segmentations.

(3) This paper proposes a traffic scene semantic image reconstruction model based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which achieves high-precision reconstruction of semantic images.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the system architecture of vehicle collaborative perception based on semantic communication, as well as the related work of semantic segmentation and image reconstruction. Section 3 presents the semantic segmentation technology for traffic scene images based on Transformer. Section 4 describes the semantics-based image reconstruction technology for traffic scenes using the GAN model. The datasets and experiment results are reported in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. System Architecture and Related Work

2.1. System Architecture

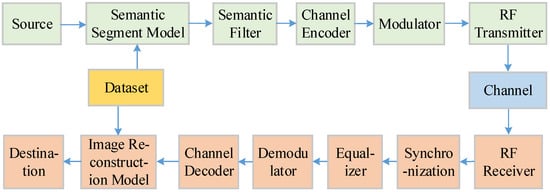

The system architecture of vehicle collaborative perception based on semantic communication is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The system architecture.

A series of images captured by on-vehicle or ground-based cameras.

The semantic segmentation model trained on the dataset is used to perform semantic segmentation on the image, resulting in the semantic segmentation mask.

The semantic filter is goal-oriented. By analyzing the semantic segmentation results of images, it only transmits images containing useful semantic information, thus avoiding the transmission of unnecessary information. For instance, the semantic segmentation mask of an image is transmitted only when the image includes key classes such as vehicles, pedestrians, bicycles, motorcycles, and traffic signs, etc.

Channel encoder and Modulator: The filtered semantic segmentation mask is encoded by an appropriate channel coding scheme, such as Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) codes, to enhance transmission reliability in complex channel environments. The encoded data is then modulated and RF transmitted by the antenna.

In the receiver, the signal received by the antenna. And synchronization, equalization, demodulation, and channel decoding are performed to recover the transmitted semantic segmentation results. These semantic segmentation results can be directly used for intelligent vehicle driving, or be used to complete image reconstruction in an image reconstructor.

To ensure the performance of image reconstruction, the image reconstructor in the receiver and the semantic segmentation model in the transmitter usually share the same dataset for model training.

2.2. Related Work

2.2.1. Semantic Segmentation

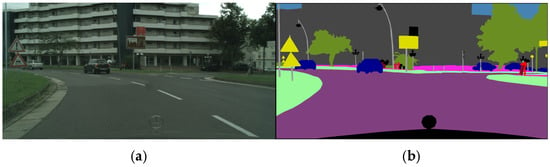

Semantic segmentation is an important research direction in computer vision. By learning image features and inter-class relationships, Semantic segmentation exploits the semantic information inherent in input images to partition them into multiple regions, with each region mapping to a specific semantic category (e.g., buildings, roads, vehicles, pedestrians, and trees) [13]. Specifically, semantic segmentation involves classifying individual pixels in an image into distinct categorical labels. Beyond mere object detection, it further models the contextual dependencies between objects, laying a groundwork for subsequent image analysis and high-level visual understanding, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Semantic segmentation. (a) Original image; (b) semantic segmentation image.

Semantic segmentation has demonstrated significant advantages across various fields, including autonomous driving (e.g., traffic scene perception) and medical image analysis (e.g., lesion region localization). With the rapid progression of deep learning techniques, numerous deep learning-based semantic segmentation models have been proposed sequentially in recent years [14,15].

A Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) based on Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) has been proposed [16]. This approach extended the basic convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture and has since evolved into one of the most extensively adopted semantic segmentation techniques.

However, the multiple alternating convolutional and pooling layers in FCN downsample feature maps, which consequently leads to low-resolution prediction outputs and the loss of local and/or global information. To address this issue, various optimized architectures have been proposed.

He, K. et al. introduced the Deep Residual Network (ResNet), a feature encoding-based semantic segmentation framework [17]. Employing pre-activated residual block variants, this network addressed critical challenges—specifically performance saturation and gradient vanishing—caused by excessive network depth, while concurrently mitigating backpropagation bottlenecks.

Additionally, many other distinct semantic segmentation models have emerged, such as VGG-16 [18], DenseNet [19], AlexNet [20], and HANet [21].

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. were the first to introduce the Transformer architecture to the visual domain, proposing an image classification framework. This framework partitions images into fixed-size non-overlapping patches and feeds these patches into a canonical Transformer encoder [22].

Zheng, S. et al. proposed the SETR model, which for the first time adopted a purely Transformer-driven architecture for semantic segmentation tasks [23]. This finding verified that Transformers are capable of effectively model long-range contextual dependencies and remarkably enhancing the accuracy of semantic segmentation.

Liu, Z. et al. developed the Shifted Window (Swin) Transformer model, which introduced a hierarchical Transformer architecture [24]. Through the integration of local window-based self-attention and a cross-window shifting mechanism, this model achieves a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and global information modeling capability.

Xie, E. et al. developed the SegFormer model, which incorporates a lightweight hierarchical Transformer encoder coupled with a position-encoding-free design [25]. This model yields efficient yet accurate semantic segmentation across multiple datasets.

Additional semantic segmentation models include Mask2Former [26], Swin-UNet [27], and OneFormer [28], etc.

2.2.2. Image Reconstruction

Image generation/reconstruction technologies have been one of the core research directions in computer vision, exhibiting extensive application potential in autonomous driving, intelligent transportation, virtual reality, and other relevant domains.

GAN proposed by Goodfellow et al. [29], pioneered novel paradigms in the field of image generation. This framework reformulates the generation task as a two-player minimax game: the generator is empowered to generate samples approximating the true data distribution, whereas the discriminator is trained to discriminate between real data samples and generated counterparts.

Building on the foundational framework of GAN, conditional image generation technologies have further facilitated the reconstruction of visual images from semantic representations. The Pix2Pix model, proposed by Isola et al. [30], pioneered the application of conditional GAN (cGAN) to image-to-image translation tasks, realizing a spectrum of image transformation tasks via training on paired image datasets. This method adopts a U-Net-based generator architecture and a PatchGAN discriminator, yielding remarkable performance in the conversion of semantic labels to photo-realistic images.

To address the demand for high-resolution image generation, Wang et al. proposed the Pix2PixHD model [31]. This model employs a multi-scale architecture integrating generators and discriminators, facilitating the progressive generation of high-resolution images via a coarse-to-fine strategy. This architectural framework ensures that the generator sustains both a coherent global structure and realistic local details.

Building upon this foundation, the SPADE method was proposed by Park et al. [32]. Its core innovation resides in a spatially adaptive normalization mechanism that dynamically generates normalization parameters from the input semantic map, enabling semantic information to exert precise spatial modulation at each network layer. Experiments conducted on benchmark datasets including Cityscapes [33] and ADE20K [34] have demonstrated that SPADE outperforms previous state-of-the-art methods significantly, with generated images achieving both superior visual realism and enhanced preservation of semantic structure integrity.

Building upon the SPADE framework, the OASIS method, proposed by Schönfeld et al. [35], introduced substantial improvements to the discriminator’s architecture. Its core innovation resides in reconfiguring the discriminator as a dedicated semantic segmentation network, with the provided semantic label maps directly adopted as ground truth for training. Leveraging only adversarial loss, OASIS enables the generation of high-fidelity images with robust alignment to input semantic label maps—achieved by delivering enhanced spatial and semantic awareness in feedback signals to both the discriminator and generator. On the ADE20K and Cityscapes benchmark datasets, OASIS attained an average improvement of 6 points in FID [36] and 5 points in Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) relative to prior state-of-the-art methods.

From a comprehensive perspective, current semantic image generation technology has evolved into a coherent development paradigm, progressing from basic conditional generation, through spatially adaptive normalization, to discriminator architecture optimization. The GAN framework exhibits inherent advantages including fast inference speed and compatibility with real-time applications. Specifically, SPADE effectively retains semantic fidelity via its spatially adaptive normalization mechanism, whereas OASIS further enhances generation quality and semantic alignment performance by optimizing the discriminator architecture. In the paper, the SPADE-GAN based technical framework has been selected, primarily due to its balanced performance in semantic fidelity preservation and inference efficiency—attributes that better align with the dual requirements of real-time responsiveness and precision in intelligent transportation systems.

3. Semantic Segmentation for Traffic Scene Image

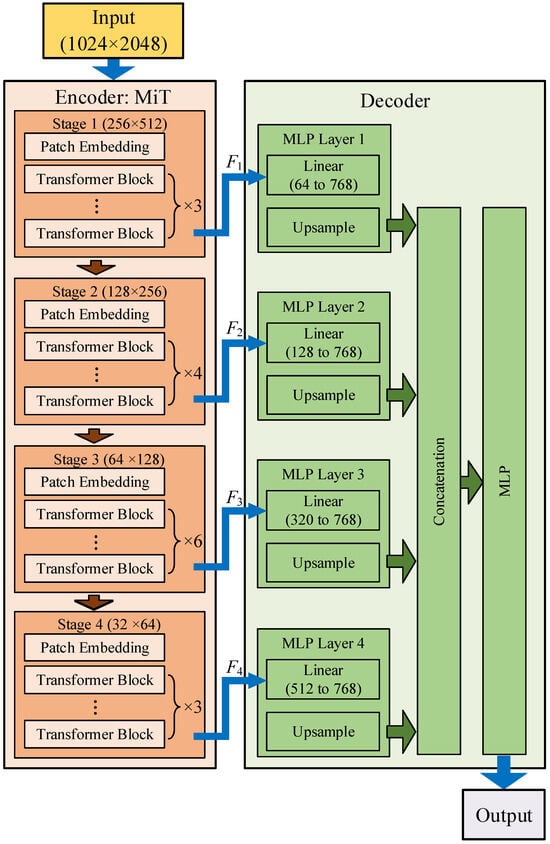

This paper uses a Transformer-based semantic segmentation model, which is divided into two parts: an encoder and a decoder, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the semantic segmentation model.

The encoder is composed of multi-level Mixed Transformers (MiT) and is responsible for multi-scale feature extraction. And the decoder consists of modules lightweight Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), upsampling, concatenation layers, which effectively fuse features of different scales to generate the final segmentation result.

3.1. Encoder

As shown in Figure 5, the MiT encoder adopts hierarchical design, consisting of four Stages (Stage 1~Stage 4). Through this hierarchical structure, the encoder gradually reduces the spatial resolution of the feature map (i.e., generates feature maps of different scales), while increasing the number of channels, thereby building a multi-feature representation to adapt to the representation needs of different classes in the segmentation task. Each Stage consists of an overlapping Patch Embedding and multiple repeatedly stacked Transformer Blocks.

3.1.1. Patch Embedding

In Vision Transformer (ViT), Patch merging combines non-overlapping image features into feature vectors, but this non-overlapping merging will break the local continuity around pixels. To address this issue, the Patch Embedding used in this model is essentially an overlapping merging. By defining the (K, S, P) triplet, there is overlap between pixels, thereby preserving the continuity of local features. Here, K is the Patch size, S is the stride between adjacent Patches, and P is the padding size. Two parameter configurations (i.e., (7, 4, 3) and (3, 2, 1)) are employed for overlapping merging, with the former utilized for Stage 1 and the latter for Stages 2 to 4.

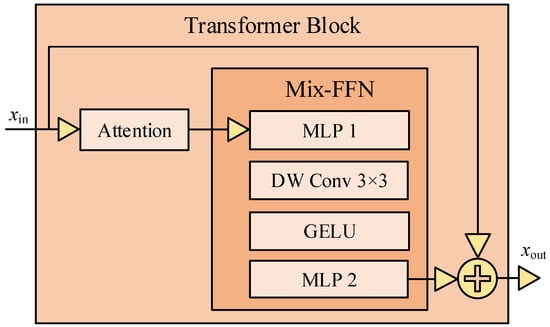

3.1.2. Transformer Block

Transformer Block is composed of Attention module, Mix-FFN module and residual connection, illustrated as Figure 6. In Transformer Block, instead of using traditional position coding, position information is implicitly captured using the Deep Separable Convolution (DWConv) operation in Mix-FFN, simplifying model design.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the Transformer Block.

The modules within Transformer blocks are described as follows.

- Attention module

The traditional multi-head self-attention mechanism formula is:

where Q, K, V are query, key and value, respectively, N = H × W, H and W are height and width of the image, C is number of the channel, dhead is the dimension of the key vectors.

In the proposed model, the multi-head self-attention module adopts the sequence reduction (SR) process introduced in [37], and can be expressed as

where K is the reduced sequence, and R is the reduction ratio, refers to reshaping K of dimension N × C into of dimension N/R × CR.

Through the reduction, the complexity of the self-attention mechanism is reduced from to . In the proposed model, R is set to be 64, 16, 4, and 1 in Stage 1 to Stage 4, respectively.

- 2.

- Mix-FFN module

The overall calculation formula of the Mix-FFN module is as follows:

where is the output feature of the self-attention module, MLP denotes Multi-Layer Perceptron, Conv3×3 denotes 3 × 3 Depthwise Convolution (DWConv), and denotes Gaussian Error Linear Unit.

FFN is a classic feed-forward neural network and performs nonlinear transformation on the features of each position to enhance the expressive ability.

First, MLP 1 enhances feature expression by expanding the number of channels. Then, a 3 × 3 DWConv is added. DWConv uses a 3 × 3 convolution kernel to slide and process feature maps, convolving each channel individually, implicitly capturing spatial position information, and is used to replace traditional FFN and positional encoding.

Then, it undergoes activation by the GELU to introduce nonlinear transformation; the number of channels is compressed in MLP 2.

Finally, a residual connection is performed to obtain the result of the Transformer Block.

Each of the 4 Stages stacks multiple Transformer Blocks, and finally outputs semantic information features F1~F4 with different dimensions, from low-level to high-level, to the decoder, respectively.

3.2. Decoder

In semantic segmentation task, CNN often needs to expand the effective receptive field (ERF) via context module, thus increasing the computational burden of the model. In this paper, the multi-level Transformer Block can generate both highly localized and non-localized features simultaneously. By fusing these two kinds of attention through MLP, the decoder can obtain larger ERF without introducing complex structure with only a few new parameters.

At first, the encoder output F1~F4 are fed into the MLP Layer 1 to MLP Layer 4, respectively, and projects them to the same dimension via the linear layer. This operation maintains the spatial resolution while only changing the number of channels, facilitating subsequent fusion. The formula is

where Co denotes the output dimension of the linear layer. In the paper, C1 = 64, C2 = 128, C3 = 320, C4 = 512, and Co = 768.

Then, is upsampled to a resolution of within the upsampling module, expressed as

Next, the features of MLP 1~4 layers are concatenated. For the concatenated feature with 4Co channels, it is fused into a feature F with C channels through a linear layer, can be expressed as

where Concat denotes concatenation operation.

Finally, the fused feature F is mapped to the segmentation mask M through MLP, can be expressed as

where is the number of classes of segmentation.

3.3. Summary of Section 3

In this section, a Transformer-based semantic segmention model is proposed, with the following innovations:

(1) During model training, the conventional AdamW optimizer tends to converge to “sharp minima” in the loss landscape, which readily induces overfitting when handling variations in lighting conditions or road textures. In contrast, Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) adopted in the paper demonstrates a propensity to converge to “flat minima”, thereby exhibiting superior robustness in capturing the structural features of lanes and vehicles rather than task-irrelevant background noise.

(2) To address gradient instability during the early training stages of Transformer model, a learning rate strategy combining step-wise updates and linear warmup is employed.

First, the learning rate is updated in a step-wise fashion rather than being updated per epoch. This design strategy yields a smoother learning rate trajectory and enhances sensitivity to subtle gradient variations, thereby enabling more precise convergence regulation.

Second, a linear warmup mechanism is incorporated. During the initial warm-up phase, the learning rate exhibits a linear increase from a near-zero initial value of lrbase/STEPwarmup to the base learning rate (lrbase), as detailed below:

where STEPwarmup denotes a step count threshold, which is typically configured as 5% of the total training steps. Upon completion of the warm-up phase (i.e., when ), a cosine annealing strategy is applied to achieve a smooth decay of the learning rate.

This enables the model to stably explore optimal directions in the parameter space, effectively enhancing convergence efficiency and final performance in complex segmentation tasks (e.g., urban traffic scene segmentation).

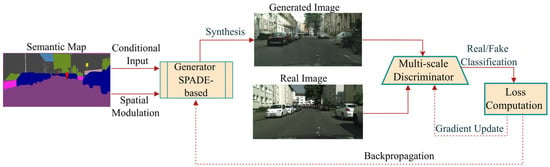

4. GAN-Based Semantic Image Reconstruction Model

Given a semantic map , where C denotes channel, i.e., the number of semantic classes. The objective of image reconstruction is to learn a generative mapping , such that the generated image not only accurately reflects the scene structure and object layout in the input semantic segmentation map, but also appears visually realistic. Therefore, the core challenge of image reconstruction lies in effectively utilizing semantic information to guide the image generation process while maintaining visual consistency and realism across different semantic regions.

Traditional cGAN-based approaches typically integrate conditional information via simple feature concatenation, which exhibits limited performance in processing complex spatial images. In this paper, through the integration of a spatial-adaptive normalization mechanism into the GAN architecture, semantic information is enabled to exert precise spatial modulation at each network layer. This design effectively preserves the semantic structure while facilitating the generation of high-fidelity visual details.

4.1. Overall Framework of Image Reconstruction Model

The overall framework of the proposed GAN-based image reconstruction model is illustrated in Figure 7. The model consists two core networks: a generator G and multi-scale discriminators D, which are trained in parallel to optimize the joint performance of both components. The generator synthesizes a scene image from the input semantic segmentation map. Meanwhile, the discriminator contrasts the synthesized scene image with the corresponding real image, and attempts to classify them as fake and real, respectively.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the GAN-Based semantic image reconstruction model.

In contrast to the conventional GAN architecture, the generator proposed adopts a residual block-based framework integrated with Spatially Adaptive Normalization (SPADE)—a critical design element for realizing high-fidelity semantic image synthesis.

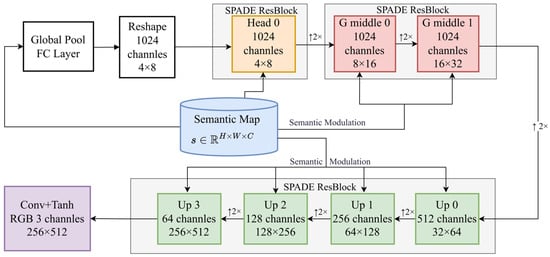

4.2. Generator

The generator follows an encoder–decoder paradigm, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the generator.

Initially, the global average pooling features of the semantic map are mapped to a high-dimensional feature space through a fully connected layer, and this initial feature is subsequently reshaped into a low-resolution (4 × 8) feature map.

Subsequently, the core component of the generator—seven SPADE residual blocks, which are distributed across different feature resolution levels. Through six bilinear 2× upsampling operations, expressed as ↑2×, the feature map resolution is progressively increased from 4 × 8 to 256 × 512. Meanwhile, a channel reduction strategy is employed: the first three residual blocks (Head 0, G middle 0, G middle 1) maintain 1024 channels to fully extract high-level semantic features, followed by four residual blocks (Up 0 to Up 3) that progressively reduce the channels to 512, 256, 128, and 64.

Ultimately, a 3 × 3 convolutional layer and Tanh activation function are applied to output a 3-channel RGB image.

This coarse-to-fine and progressive channel reduction design empowers the network to tackle the image synthesis task across varying levels of abstraction—ranging from high-level scene layout to low-level texture details—where each layer fully leverages semantic information to implement precise spatial modulation.

The SPADE residual block acts as a core component of the generator, with the SPADE normalization layer serving as the core module within SPADE residual block. Both modules are elaborated upon in the subsequent sections.

4.2.1. SPADE Residual Block

The architecture of the SPADE residual block comprises two parallel paths: a main path and a skip connection path.

The main path first employs SPADE normalization on the input feature map x and semantic map s, followed by a LeakyReLU activation function, and subsequently a 3 × 3 convolutional layer incorporating spectral normalization. This sequence of operations is repeated twice, thus constituting a dual-convolution configuration.

When the input and output channel counts are inconsistent, the skip connection path first employs SPADE normalization, followed by channel count adjustment via a 1 × 1 convolutional layer with spectral normalization. When the channel counts are consistent, the skip connection enables direct propagation of the input features.

The final output of the SPADE residual block feature map h is obtained by summing the features from the two paths, which is formulated as

Spectral normalization (SN) is applied to all convolutional layers to constrain the maximum singular value of the weight matrices, thereby mitigating gradient explosion. The residual design facilitates smooth backward gradient propagation, enabling the effective training of deep networks. The generator adopts a progressive upsampling strategy, which gradually refines image details across multiple scales to ensure high fidelity in both the global structure and local textures of the synthesized images.

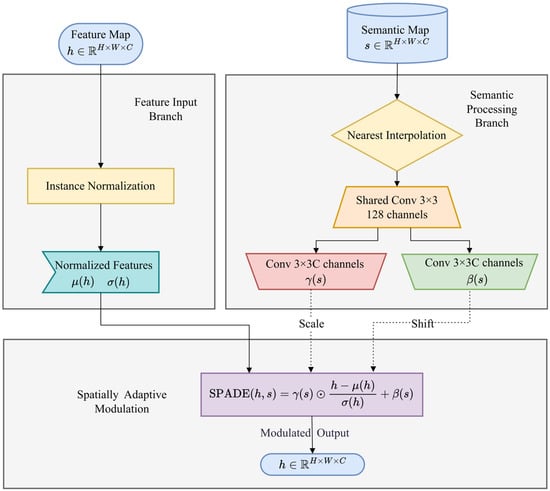

4.2.2. SPADE Layer

The SPADE layer is the core module in the SPADE residual block.

Traditional instance normalization computes the mean and standard deviation of each feature channel across spatial dimensions, and subsequently employs these global statistics to normalize the features. Although this approach enhances training stability, it inevitably erodes the spatial variation patterns inherent in the feature maps—a critical factor for preserving the semantic structure.

The SPADE layer retains the feature normalization step to ensure training stability, but its modulation parameters are no longer fixed, globally learned scalars. Instead, these parameters take the form of spatially varying parameter maps dynamically derived from the input semantic map. This design remedies the core limitation of conventional normalization methods—namely, the erasure of spatial structural information, which is critical for semantic image generation.

As illustrated in Figure 9, the SPADE layer comprises two parallel processing branches.

Figure 9.

Diagram of the SPADE Layer.

Feature input branch: The input feature map is first normalized via Instance Normalization, yielding normalized features:

where μ(h) and σ(h) denote the mean and standard deviation of feature map h over the spatial dimensions.

Semantic processing branch: The input semantic map is first resized via nearest-neighbor interpolation to match the spatial resolution of the current feature map h. The resized semantic map is fed into a shared 3 × 3 convolutional layer to generate intermediate activations, followed by two separate 3 × 3 convolutional branches that produce the scaling parameter γ(s) and offset parameter β(s) of semantic map s. Both parameter sets share the same spatial dimensions and channel count.

The outputs of the two branches are subjected to an element-wise affine transformation via semantically guided, and the spatially adaptive modulation output is

where denotes element-wise multiplication.

The core advantage of this design lies in that features at distinct spatial locations undergo differentiated normalization treatments based on their corresponding semantic classes. For instance, building-corresponding regions may require preservation of more structural information, whereas sky-corresponding regions demand smoother feature representations. By enabling the semantic map to directly govern the normalization parameters, SPADE empowers the network to adaptively process features across distinct semantic regions, thus preserving the integrity of semantic information throughout the image generation process.

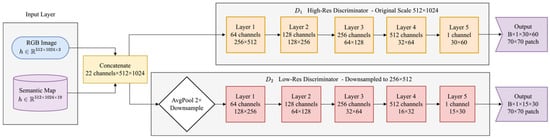

4.3. Multi-Scale Discriminator

The multi-scale discriminator architecture proposed in the paper is illustrated in Figure 10, comprising two discriminators with identical structures but operating at distinct image scales. The first discriminator D1 performs discrimination directly on the original high-resolution image, while the second discriminator D2 conducts discrimination on the downsampled low-resolution image.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the multi-scale discriminator.

This multi-scale architecture enables discriminators to assess realism across multiple image scales. Specifically, the high-resolution discriminator focuses on the fidelity of local details and textures, while the low-resolution discriminator emphasizes the reasonableness of the global structure and large-scale objects. By integrating discrimination outputs from both scales, the generator can simultaneously optimize the global consistency and local detail quality of the synthesized images.

Both discriminators employ the PatchGAN architecture. The core principle of this architecture lies in discriminating the authenticity of local image regions (i.e., patches) instead of the entire image. The discriminator outputs an H × W feature map, where the value at each spatial position denotes the realism score of the corresponding receptive field region. This design delivers fine-grained local feedback signals, allowing the generator to independently optimize distinct regions of the synthesized image.

Both discriminators comprise 22-channel features. This conditional input design ensures that the discriminators not only assess image realism but also implicitly evaluate the consistency between the synthesized image and the semantic map. Both discriminators incorporate five identical 4 × 4 convolutional layers, and the computational process is as follows:

where LeakyReLU denotes Leaky Rectified Linear Unit, IN denotes Instance Normalization, and SN denotes Spectral Normalization, Conv4×4 denotes 4 × 4 convolutional layer, and denotes the output of the l-th layer in the k-th discriminator.

The spatial resolution of the feature maps progressively decreases, with channel dimensions sequentially set to {64, 128, 256, 512, 1}. With this setup, the network gradually reduces spatial resolution while expanding feature channel dimensions, ultimately outputting a single-channel discriminative feature map.

Each position in the discriminator’s output feature map corresponds to a 70 × 70 pixel patch in the input image. This ERF size is sufficient to capture local texture structures while preserving robust spatial discriminative capability. Given the input resolution configuration adopted in this work, the two discriminators output discriminative feature maps with dimensions B × 1 × 30 × 60 and B × 1 × 15 × 30, respectively, where B denotes the batch size.

The discriminator designed in the paper offers several key advantages: First, the spatial output feature map provides fine-grained local feedback, facilitating targeted refinement of different image regions by the generator. Second, in contrast to fully connected output layers, PatchGAN achieves a substantial reduction in parameter count as it eliminates the need for fully connected layers to aggregate global information. Finally, the convolutional architecture renders the discriminator applicable to images of arbitrary sizes, thereby enhancing the model’s flexibility and generalization performance.

4.4. Loss Functions

During training, the discriminator and generator optimize their respective independent loss functions and conduct adversarial training via alternating parameter updates. This adversarial framework drives the generator to iteratively enhance generation quality to deceive the discriminator, ultimately realizing the objective of synthesizing high-quality images.

4.4.1. Loss Functions in Discriminator

The discriminator is trained with the Hinge loss. This loss function encourages the discriminator to output scores greater than 1 for real image x-semantic map s pairs and scores less than 1 for generated image G(s)-semantic map s pairs , and is defined as:

where denotes the output of the discriminator given inputs x and s, and denotes expected value over x and s, and denotes expected value over s.

For the multi-scale discriminator, the total discriminator loss is the average of the losses from all scale-specific discriminators, and can be express as

where K denotes the number of scale-specific discriminators (i.e., K = 2 in the paper).

Relative to the conventional Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) loss, the Hinge loss delivers enhanced training stability and helps alleviate mode collapse.

4.4.2. Loss Functions in Generator

Unlike the discriminator’s singular optimization objective, the generator must simultaneously satisfy multiple constraints: it needs to deceive the discriminator to boost realism (adversarial objective) while maintaining alignment with real images in terms of perceptual quality, semantic consistency, and pixel accuracy (reconstruction objective). Thus, the generator’s training objective is to minimize a weighted multi-objective composite loss, defined as:

where denotes the adversarial loss, denotes the VGG perceptual loss, denotes the feature matching loss, and is the L1 pixel loss. The weight coefficients regulate the relative importance of each loss term.

(1) Adversarial Loss

The adversarial loss quantifies the generator’s capability to deceive the discriminator, which is defined as

The generator seeks to maximize , prompting the discriminator to assign high scores to generated images. For the multi-scale discriminator setup, the average of the outputs across all scales is computed. As the core of GAN training, the adversarial loss directly governs the realism and distribution alignment of synthesized images.

(2) VGG Perceptual Loss

This loss employs features extracted from multiple layers of a pretrained VGG19 network to quantify the distance between generated and real images in the perceptual space. Specifically, four convolutional layers from the pretrained VGG19 network are selected in the paper for feature extraction, and the VGG perceptual loss is defined as

where denotes the feature extraction function of the i-th layer in the VGG19 network, Ni denotes the total number of elements in that i-th layer’s features, and ‖ ‖1 denotes L1 norm. This weighted aggregation of multi-layer features ensures the generated image maintains consistency with the real image across different perceptual abstraction levels.

(3) Feature Matching Loss

By aligning the feature representations of real and generated images across the intermediate layers of the discriminator, this loss delivers supplementary supervisory signals to the generator:

where K denotes the number of discriminator scales, T represents the number of layers in each discriminator, and stands for the feature output of the i-th layer of the k-th discriminator. This loss term aids in stabilizing the training process; moreover, as the discriminator’s features contain rich semantic information, aligning these features helps the generator maintain structural consistency with the input semantic map.

(4) L1 Pixel Loss

This imposes the most straightforward pixel-level reconstruction constraint, and is defined as

L1 Pixel Loss delivers stable gradient signals in the early training stages, enabling the generator to rapidly acquire fundamental color and brightness mapping relationships, thereby facilitating enhanced semantic consistency.

4.5. Summary of Section 4

In this section, a GAN-Based semantic image reconstruction model is proposed for semantic image generation, with the following innovations:

(1) A multi-objective weighted loss function was designed oriented evaluation objectives, balancing visual realism, semantic consistency, and perceptual quality. Via simulation experiments, the loss configuration was optimized to obtain tradeoff between visual fidelity and semantic alignment in urban traffic scenarios.

(2) A multi-scale discriminator architecture was employed, in which the high-resolution discriminator guarantees the precision of fine-grained details (e.g., vehicle contours and pedestrian appearances), while the low-resolution discriminator upholds the correctness of spatial layout and road structure. This multi-scale mechanism enables the generated images to simultaneously meet the requirements for both local semantic accuracy and global structural consistency within cooperative perception scenarios.

5. Experiments Results

In this section, experiments are conducted to evaluate the performance of the semantic segmentation model and image reconstruction model proposed in the paper, based on the Cityscapes dataset.

5.1. Dataset

In the paper, the popular Cityscapes dataset is employed, which provides 5000 images with high-quality dense annotations and 20,000 additional images with coarse labels obtained using a novel crowdsourcing platform, and is the most relevant to the autonomous driving scenario. The Cityscapes dataset has 19 classes, including ‘road’, ‘sidewalk’, ‘building’, ‘wall’, ‘fence’, ‘pole’, ‘traffic light’, ‘traffic sign’, ‘vegetation’, ‘terrain’, ‘sky’, ‘person’, ‘rider’, ‘car’, ‘truck’, ‘bus’, ‘train’, ‘motorcycle’, ‘bicycle’.

5.2. Platform

The experiments were performed on the workstation, whose configuration parameters are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Configuration parameters of the workstation.

5.3. Experiments of Semantic Segmentation Performance

5.3.1. Performance Comparison with Traditional Semantic Segmentation Models

In this subsection, the semantic segmentation performance of the proposed SegFormer-based model is compared with that of the ISSAFE model. The models parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model parameters.

Table 3 presents the mean mIoU and overall accuracy of the two models on the Cityscape dataset, while Table 3 provides the semantic segmentation performance for several key classes.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of various model.

As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, the SegFormer model achieves an mIoU of 73.760% and overall accuracy of 93.828%, both significantly outperforming the ISSAFE model with 40.800% (mIoU) and 89.660% (overall accuracy), respectively. These two metrics collectively confirm that the SegFormer model exhibits superior predictive accuracy.

Table 4.

Semantic segmentation performance for several key classes.

Across major classes, the SegFormer model sustains high semantic segmentation accuracy. For key scene components such as buildings, vegetation, sky, and vehicles, the IoU values exceed 90%. Even for fine-grained classes such as fences and poles, the IoU reaches 51.94% and 62.38%, respectively—which are substantially higher than the ISSAFE model’s 26.54% (for fences) and 32.75% (for poles). The results demonstrate the SegFormer model’s stronger capacity in handling small-scale or fine-grained objects. Compared with the ISSAFE model, the SegFormer model also achieves more balanced performance across all classes, while the ISSAFE model exhibits distinct weaknesses in certain classes. This consistent performance highlights the SegFormer model’s superior generalization ability and stability.

5.3.2. Model Performance Evaluation

(1) Hyperparameters

Within this subsection, the learning rate (LR), weight decay (WD), training epochs, and batch size are optimized to improve performance. The hyperparameter settings and corresponding segmentation results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hyperparameter optimization.

The results of experiments 1–4 indicate that the model exhibits low sensitivity to variations in the learning rate and weight decay, with the deviation in mIoU values within 1.5%. For individual object classes, the model exhibits prominent performance on critical traffic classes, such as car (IoU: 93%), Person (IoU: 80%), Rider (IoU: 60%), truck (IoU: 60%), and bus (IoU: 85%). In particular, for the critical category car, the model achieves a mIoU of 93%. The relatively lower IoU performance of the rider and truck classes is primarily attributed to their limited sample in the training dataset, which constrains the model’s learning efficiency for these two classes. Future performance enhancements can be realized by incorporating more samples of these underrepresented classes into the training dataset.

Experiments 5–7 were conducted to investigate the impact of training duration on model performance. The results show that the model achieved a mIoU of 73.837% at 100 epochs; extending the training duration to 300 epochs resulted in only a marginal improvement of 0.625%, which demonstrates diminishing returns for prolonged training. Furthermore, convergence rates exhibited significant variations across semantic classes: simpler classes reached optimal performance rapidly, while challenging classes (e.g., Walls) demanded extended training durations. To mitigate these challenges, an early stopping mechanism was implemented to terminate training once model performance stabilized to reduce computational overhead and mitigate overfitting.

Experiments 6–8 were conducted to evaluate the impact of batch size. Specifically, the results indicate that mIoU variations across most object classes remained within 1% in magnitude.

These experimental results illustrate the model’s robust performance under varying hyperparameter configurations, thereby supporting its practical deployment and real-world application.

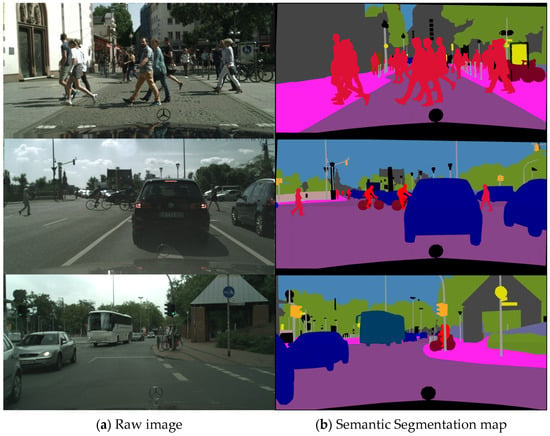

(2) Performance in Key Scenario

The previous subsection assessed the performance of the proposed semantic segmentation model on the entire Cityscapes dataset. However, semantic significance exhibits substantial variations across images and object classes. This subsection focuses on assessing the performance of the proposed semantic segmentation model in challenging traffic scenarios with high accident potential.

Figure 11 illustrates the semantic segmentation results for representative images from complex traffic scenarios. The results reveal that the proposed model achieves precise segmentation with clear boundary delineation for critical traffic elements, such as moving pedestrians and cyclists crossing roadways, vehicles in both the same-direction and opposing lanes, and roadside traffic signals and signage.

Figure 11.

Segmentation performance in key scenario.

(3) Data Compression Rate

Standard RGB images demand 24 bits per pixel (8 bits × 3 channels) for color encoding. In contrast, semantic segmentation generates mask images in which each pixel requires only 4–8 bits to encode its semantic category, thereby achieving a substantial reduction in data requirements. Notably, semantic segmentation also produces data structures that are inherently more compatible with efficient image compression algorithms.

For instance, the Portable Network Graphics (PNG), as a lossless compression format, achieves superior efficiency for image data compression via two fundamental mechanisms: First, predictive filtering exploits spatial pixel correlations to compute differential sequences, thereby generating extensive zero-value patterns; Second, the Deflate algorithm combines LZ77 dictionary compression and Huffman coding algorithm to attain near-optimal compression ratios for these zero-rich sequences.

The difference sequences of semantic segmentation mask exhibit a high proportion of zero values and possess significant spatial redundancy, which can notably enhance the compression ratio of the Deflate algorithm.

Table 6 presents the size and data compression rate after applying semantic segmentation and the PNG format to the entire Cityscapes dataset. As shown in the table, the combination of semantic segmentation and the PNG format significantly reduces the image data size.

Table 6.

Mean size and compression rate.

Assuming that the frame rate of the vehicle-mounted camera is 25 frames per second (fps) and the resolution of each image is 1024 × 2048, a single image will be 2.17 megabytes (MB) with PNG format. Correspondingly, the data rate generated by a single camera would reach 25 × 2.17 MB = 54.25 MB/s. In contrast, with the method proposed in this paper, the data rate of the semantic segmentation is only 25 × 23.2 kB = 580 kB.

5.4. Experiments of Image Reconstruction Model Performance

This work utilizes three complementary evaluation metrics—Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS), and mIoU—to provide a comprehensive evaluation of generated image quality. Specifically, FID quantifies the realism of generated images, LPIPS assesses perceptual similarity to real-world counterparts, and mIoU measures semantic consistency with ground-truth annotations.

The proposed image reconstruction model employs the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.00015, β1 = 0, β2 = 0.999, and a batch size of 14. Training was conducted for 200 epochs, where the learning rate was linearly decayed to 0 starting from epoch 100. To mitigate gradient explosion, gradient clipping was implemented with a maximum norm of 5.0. All convolutional layers incorporate spectral normalization to enhance the stability of training.

5.4.1. Weight Configuration Parameter Optimization

This work integrates a suite of complementary loss functions into the GAN framework to improve generation performance. This subsection investigates the weight configurations of distinct loss functions and derives optimal weight settings via systematic simulations. Table 7 provides a performance comparison between the baseline and optimized weight configurations.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of different weight configurations.

Table 7 demonstrates that the optimized weight configuration significantly outperforms the baseline across all three evaluation metrics, FID, LPIPS, and mIoU. Thus confirming the efficacy of the proposed weight optimization strategy. Specifically, FID decreased by 12.2% from 81.48 to 71.5, marking a substantial improvement in the realism and data distribution alignment of generated images. LPIPS reduced by 6.4% from 0.468 to 0.438, indicating that the generated images exhibit greater perceptual similarity to real-world counterparts. mIoU increased from 0.284 to 0.367 (a 29.2% improvement), reflecting an enhanced ability of the model to retain structural information from the input semantic map.

Overall, the mechanism underlying the synergistic optimization of the three performance metrics is summarized as follows: FID optimization is primarily accomplished by increasing the adversarial training weight (↑λGAN) and enhancing feature detail preservation (↑λfeat); LPIPS optimization is realized via strengthening perceptual alignment (↑λVGG); mIoU optimization is achieved through multi-faceted synergy, including structural preservation (↑λfeat), pixel-wise constraint enforcement (↑λL1), and boundary sharpening (↑λGAN). Experimental findings confirm that this strategy achieves the synergistic enhancement of all three objectives while ensuring training stability.

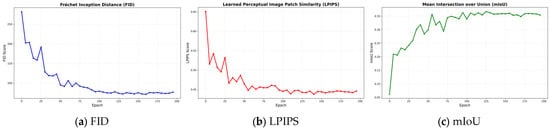

5.4.2. Training Performance

This subsection compares the performance of the proposed model under the optimized weight configuration across various training epochs.

As presented in Figure 12, during training, all three evaluation metrics—FID, LPIPS, and mIoU—exhibit consistent improvement, approaching their respective optimal values around epoch 150, thus confirming that the model has essentially achieved convergence to a stable operational state. The smoothness and monotonicity of the training curves validate that the optimized weight configuration not only achieves synergistic optimization of the three objectives but also maintains training stability, without the common oscillation or collapse phenomena.

Figure 12.

Training Curves.

5.4.3. Model Performance Comparison

To validate the performance of the proposed model, comparative evaluations are conducted against two state-of-the-art image generation benchmark models—pix2pixHD [31] and SPADE [32]—as presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of image reconstruction models.

In terms of realism, the FID of the proposed method is 31.7% lower than that of pix2pixHD, and comparable to that of SPADE (71.5 vs. 71.8), indicating that the distribution alignment of generated images with real data has attained a state-of-the-art level. This work is the first to incorporate LPIPS (0.438) as a complementary metric for perceptual quality assessment. Via a mechanism-driven weight optimization strategy, the proposed method realizes balanced multi-objective optimization across realism (FID), and perceptual quality (LPIPS), thus offering novel evaluation perspectives and optimization paradigms for semantic image synthesis.

5.4.4. Image Reconstruction Results for Key Scenarios

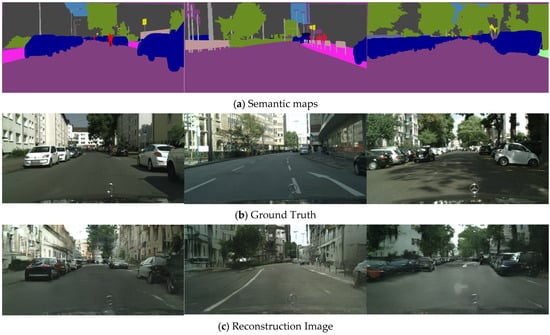

Figure 13 presents the image reconstruction results and their corresponding input semantic maps and ground truth in complex scenes.

Figure 13.

Image reconstruction results.

As presented in Figure 13, the reconstruction results demonstrate the following key characteristics: (1) a precise semantic structure, featuring distinct regional boundaries and no category ambiguity; (2) highly realistic texture details; (3) natural and consistent lighting and shadow effects; (4) seamless and natural regional transitions. These characteristics confirms that the proposed image reconstruction model achieves a favorable balance between semantic precision and visual realism.

5.5. Summary of Section 5

In this section, experiments are conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed semantic segmentation model and image reconstruction model, based on the Cityscapes dataset, and the following conclusions are drawn:

1. The proposed semantic segmentation model achieves a mIoU of 73.760% and overall accuracy of 93.828% on the Cityscape dataset, both outperforming the ISSAFE model. Furthermore, semantic segmentation images encoded by the PNG encoder can achieve a significantly reduction in the transmitted data volume.

2. To validate the performance of the proposed GAN-based image reconstruction model, comparative evaluations are conducted against two state-of-the-art image generation benchmark models, namely pix2pixHD and SPADE. The FID of the proposed method is 31.7% lower than that of pix2pixHD and comparable to that of SPADE. Moreover, the reconstruction results exhibit precise semantic structures, highly realistic texture details, natural and consistent lighting-shadow effects, and seamless regional transitions.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

To address the visual blind spots caused by the vehicle itself, surrounding vehicles, and buildings in real-world traffic scenarios, this paper proposes a novel vehicle collaborative environmental perception technology based on V2V/V2I semantic communication. In the proposed technology, a Transformer-based semantic segmentation model is constructed. Within the model, SGD optimizer is employed as the optimizer instead of the conventional AdamW optimizer, and a linear warmup mechanism is integrated. These strategies enhance convergence efficiency and the final performance in complex road scene segmentation tasks. And an image reconstruction model based on GANs is further proposed. Within the model, a multi-objective weighted loss function and a multi-scale discriminator architecture are employed to achieve high-precision reconstruction of semantic images.

Future research may focus on below directions.

1. The semantic segmentation model and image reconstruction model established are designed for 2D images acquired by optical cameras. In future research, 4D point cloud panoptic segmentation can be further investigated to provide more effective support for multi-modal sensor in autonomous driving systems.

2. In the proposed collaborative perception framework, the semantic segmentation model at the transmitter and the image reconstruction model at the receiver are trained independently. In future research, end-to-end training can be considered to construct a unified model that directly completes the entire task from input to output.

3. Now, the semantic segmentation model and image reconstruction model are trained and evaluated based on the Cityscapes dataset. However, the Cityscapes dataset has limitations in category coverage—for example, the “animal” category is not included. In future research, the dataset will be expanded by incorporating additional categories (e.g., animal), and the validation of the collaborative perception technology will be conducted in V2V/V2I communication systems under complex real-world traffic scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and H.W.; methodology, C.L.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L. and Q.J.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, C.L. and H.L.; resources, L.X.; data curation, L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., H.L. and Q.J.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and L.X.; visualization, Q.J.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.: 2025JBMC021), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: U21A20445 and 62001135), the State Key Laboratory of Advanced Rail Autonomous Operation (Grant No.: RAO2023ZZ004).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| ADAS | advanced driving assistance system |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LoS | Line-of-Sight |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure |

| 6G | Sixth Generation |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| LDPC | Low-Density Parity-Check |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| DCNNs | Deep Convolutional Neural Networks |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| mIoU | Mean Intersection over Union |

| MiT | Mixed Transformers |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| DWConv | Deep Separable Convolution |

| GELU | Gaussian Error Linear Unit |

| ERF | effective receptive field |

| SPADE | Spatially Adaptive Normalization |

| SN | Spectral normalization |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| PNG | Portable Network Graphics |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| LPIPS | Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity |

References

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, B.; Xing, Y.; Tian, D.; Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Na, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Milestones in Autonomous Driving and Intelligent Vehicles: Survey of Surveys. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Wang, C.; Hou, Y.; Liu, C. MPC-Based Integrated Control of Trajectory Tracking and Handling Stability for Intelligent Driving Vehicle Driven by Four Hub Motor. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 2668–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, S.W. Cooperative automated vehicles: A review of opportunities and challenges in socially intelligent vehicles beyond networking. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 4, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, I.; Khan, L.U.; Kazmi, S.M.A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, N.; Hong, C.S. Autonomous driving cars in smart cities: Recent advances, requirements, and challenges. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, P. A review of lane detection methods based on deep learning. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 111, 37−48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruyer, D.; Magnier, V.; Hamdi, K.; Claussmann, L.; Orfila, O.; Rakotonirainy, A. Perception, information processing and modeling: Critical stages for autonomous driving applications. Annu. Rev. Control. 2017, 44, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhenawy, M.; Ashqar, H.I.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Alhadidi, T.I.; Jaber, A.; Tami, M.A. Vision-Language Models for Autonomous Driving: CLIP-Based Dynamic Scene Understanding. Electronics 2025, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Xiang, H.; Xia, X.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Opv2v: An open benchmark dataset and fusion pipeline for perception with vehicle-tovehicle communication. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intenational Conference Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2583–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Shao, C.; Cheng, N.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J. EdgeCooper: Network-Aware Cooperative LiDAR Perception for Enhanced Vehicular Awareness. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2024, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.; Dianati, M.; de Temple, R.; Fallah, S. Cooperative Perception for 3D Object Detection in Driving Scenarios Using Infrastructure Sensors. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 1852–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Bi, H.; Gao, B.; Li, K.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y. MaTVT: A Transformer Based Approach for Multi Agent Prediction in Complex Traffic Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Jin, Y. A Semantic Segmentation Method for Road Sensing Images Based on an Improved PIDNet Model. Electronics 2025, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondi, P.E.; Baghshah, M.S. Semantic Segmentation With Multiple Contradictory Annotations Using a Dynamic Score Function. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 64544–64558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, C. PP-LiteSeg: A Superior Real-Time Semantic Segmentation Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, T.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Deep Hierarchical Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegou, S.; Drozdzal, M.; Vazquez, D.; Romero, A.; Bengio, Y. The One Hundred Layers Tiramisu: Fully Convolutional DenseNets for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-F.; Lin, K.-M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Kang, J.-C. Intelligent Mango Fruit Grade Classification Using AlexNet-SPP With Mask R-CNN-Based Segmentation Algorithm. IEEE Trans. AgriFood Electron. 2023, 1, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.T.; Choo, J. Cars Can’t Fly up in the Sky: Improving Urban-Scene Segmentation via Height-Driven Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 9373–9383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.S.; et al. Rethinking Semantic Segmentation from a Sequence-to-Sequence Perspective with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Animageravan, A.; Tu, Z.; Shen, C. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12165–12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Singapore, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; Li, J.; Chiu, M.; Hassani, A.; Orlov, N.; Shi, H. OneFormer: One Transformer to Rule Universal Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 11658–11668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the 2014 Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-C.; Liu, M.-Y.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Tao, A.; Kautz, J.; Catanzaro, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis and Semantic Manipulation with Conditional Gans. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, T.C.; Zhu, J.Y. Semantic Image Synthesis with Spatially-Adaptive Normalization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, CA, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, H.; Puig, X.; Fidler, S.; Barriuso, A.; Torralba, A. Scene Parsing through ADE20K Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, V.; Schönfeld, E.; Zhang, D.; Gall, J.; Schiele, B.; Khoreva, A. You Only Need Adversarial Supervision for Semantic Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, V.; Schönfeld, E.; Zhang, D.; Gall, J.; Schiele, B.; Khoreva, A. OASIS: Only Adversarial Supervision for Semantic Image Synthesis. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2903–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: Aversatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).