Abstract

With rapid developments of wireless communication and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, an increasing number of devices and sensors are interconnected, generating massive amounts of data in real time. Among the underlying protocols, Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) has become a widely adopted lightweight publish–subscribe standard due to its simplicity, minimal overhead, and scalability. Then, understanding such protocols is essential for students and engineers engaging in IoT application system designs. However, teaching and learning MQTT remains challenging for them. Its asynchronous architecture, hierarchical topic structure, and constituting concepts such as retained messages, Quality of Service (QoS) levels, and wildcard subscriptions are often difficult for beginners. Moreover, traditional learning resources emphasize theory and provide limited hands-on guidance, leading to a steep learning curve. To address these challenges, we propose an AI-assisted, exercise-based learning platform for MQTT. This platform provides interactive exercises with intelligent feedback to bridge the gap between theory and practice. To lower the barrier for learners, all code examples for executing MQTT communication are implemented in Python for readability, and Docker is used to ensure portable deployments of the MQTT broker and AI assistant. For evaluations, we conducted a usability study using two groups. The first group, who has no prior experience, focused on fundamental concepts with AI-guided exercises. The second group, who has relevant background, engaged in advanced projects to apply and reinforce their knowledge. The results show that the proposed platform supports learners at different levels, reduces frustrations, and improves both engagement and efficiency.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of wireless communication and IoT technologies, an increasing number of devices are now interconnected, generating massive amounts of data in real time. As these interconnected systems continue to expand, IoT technologies have been widely adopted across various domains, including smart homes, industrial automation, and environmental monitoring. Understanding the communication protocols behind these systems is essential for both students and engineers, as they enable reliable and efficient data exchange. Among these protocols, MQTT [1] is a lightweight publish–subscribe protocol commonly used in resource-limited environments. Its simple design and flexible quality-of-service options make it suitable for a broad range of IoT applications.

Although MQTT is widely used, teaching and learning this protocol remain challenging. Its asynchronous publish–subscribe architecture and hierarchical topic structure can be confusing for beginners, especially when debugging message flows in real time. Students often struggle with concepts such as retained messages, QoS levels, and wildcard subscriptions, which are essential for efficient and reliable message routing. Traditional educational resources, such as textbooks and online tutorials, tend to be highly theoretical and provide limited hands-on guidance. As a result, learners frequently face a steep learning curve and may experience frustration when attempting to apply MQTT concepts in practical scenarios.

In this paper, we propose a fully implemented AI-assisted, exercise-based learning platform designed to support the teaching and learning of MQTT communication protocols. The platform enables students to engage in interactive exercises with intelligent feedback, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Python [2] is adopted as the primary programming language for its readability and widespread use in educational contexts. Docker [3] is employed to package and run all system components locally on student devices. The sensor hardware mainly consists of Raspberry Pi units [4], chosen for their simplicity and ease of use. This configuration enables students to engage in hands-on learning without the need for complex infrastructure, while also allowing the system to be easily scaled for classroom or self-study scenarios. In advanced modules, our system also incorporates the previously developed SEMAR (Smart Environmental Monitoring and Analytical in Real-Time) platform [5] as part of the teaching materials.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed system, we conducted a usability study involving two groups of learners with different backgrounds. The first group consisted of participants with little or no prior experience in IoT and MQTT, who focused on fundamental concepts through AI-guided exercises and step-by-step tutorials. The second group included learners with relevant prior knowledge, who engaged in more advanced projects designed to apply and reinforce their understanding in practical contexts. By comparing the learning outcomes and engagement levels between these two groups, we aimed to assess whether the platform could effectively support learners at different levels. Preliminary findings indicate that the platform not only alleviates the difficulties and frustrations but also enhances learner engagement and overall efficiency, suggesting its potential for both introductory and advanced educational settings.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces related works in the literature. Section 3 reviews preliminary works leading to this paper. Section 4 presents the implementation of our work. Section 5 shows the evaluation results and analysis of our work. Finally, Section 6 concludes this paper with a discussion of limitations and future work.

2. Related Works

2.1. Educational Theories for Teaching Computer Networking and Programming

Three educational ideas guide the design of our platform: Constructivism, CLT (Cognitive Load Theory), and Active Learning. Here we briefly explain how each idea directly supports the learning experience in our MQTT system.

Constructivism highlights that learners understand concepts better when they actively work with them. This idea supports our use of hands-on exercises, where students test MQTT behavior and observe message flow directly [6,7].

CLT (Cognitive Load Theory) reminds us that beginners learn more effectively when information is divided into smaller parts. This motivates our step-by-step structure, where each exercise focuses on one MQTT feature to reduce unnecessary mental load [8].

Active Learning emphasizes participation and immediate feedback. This aligns with our interactive design: students run code, see results, and receive AI hints that guide them without giving full solutions [9,10].

Together, these ideas shaped the platform’s design by supporting gradual learning, reducing confusion, and encouraging active exploration of protocol behavior.

2.2. Application of AI in Computer Networking and Programming Education

AI is increasingly applied across the full pedagogical process in programming education, including course design, automated feedback, and performance monitoring, demonstrating a growing impact on teaching and learning [11]. Studies on AI-assisted pair programming indicate that it can significantly enhance student motivation, reduce anxiety, and improve performance compared to individual learning [12].

However, a critical challenge identified in this literature is the risk of student over-reliance on AI. One study found that while a GPT-based assistant significantly improved exam scores, an overwhelming 92% of students copied incorrect answers generated by the AI [13]. This highlights that while AI tools can boost learning, careful design is essential to prevent students from uncritically accepting misinformation.

Collectively, these studies informed our platform’s design. We use a conversational AI tutor to improve engagement and reduce anxiety, aligning with the benefits shown by [12]. To mitigate the over-reliance risk identified by [13], our system integrates mechanisms to detect misconceptions and avoid providing direct solutions. In this way, we position AI as a complementary aid that fosters exploration and reflective learning, rather than as a replacement for instruction.

2.3. Popular Learning Platforms for Computer Networking and Programming Education

Popular learning and coding platforms increasingly integrate AI to provide real-time, interactive support. Tools like Coding Rooms [14] offer AI-driven feedback and automated assessment in a live exercise environment. Virtual tutors, such as Khan Academy’s Khanmigo [15,16], use LLMs (Large Language Models) to provide personalized guidance and Socratic debugging support. Furthermore, AI-assisted “pair programmers” like GitHub Copilot [17] integrate directly into the coding workflow, offering context-aware suggestions and auto-completions.

Collectively, these platforms demonstrate how AI-enhanced interactivity can make programming education more engaging and adaptive. Their designs emphasize real-time interaction, personalized guidance, and intelligent code assessment. However, most focus on general-purpose programming and lack features tailored to domain-specific areas such as computer networking and IoT communication. Building on their pedagogical and technical strengths, our system extends these concepts to a specialized context by integrating AI-assisted learning with hands-on experimentation using the MQTT protocol. This approach bridges the gap between abstract programming concepts and practical network communication, providing students with a more authentic and context-rich learning experience.

2.4. Challenges and Existing Strategies in Teaching MQTT and IoT Communication Protocols

Teaching MQTT and other IoT communication protocols present several challenges. Prior studies show that students often struggle with the abstract, event-driven nature of publish–subscribe communication, the heterogeneity of devices, and the complexities of configuring brokers, QoS levels, and network constraints [18]. Educators also face limitations in providing sufficient hands-on resources, as physical hardware and stable network environments are necessary for meaningful experiential learning [19]. Furthermore, research on MQTT implementations highlights persistent issues related to performance, security, and interoperability, which can further increase cognitive load for beginners [20]. These findings collectively indicate that effective instruction must reduce technical overhead while preserving opportunities for direct experimentation.

To address these challenges, several platforms and instructional strategies have been proposed. A line of work develops low-cost or remote-access learning environments built on ESP32, Raspberry Pi, and Node-RED, allowing students to observe real MQTT message flows without requiring complex setup [21,22]. Remote laboratories—some designed specifically for MQTT-based experimentation—provide scalable access for large classes and support asynchronous learning [23]. Systematic reviews of IoT education further emphasize that platforms integrating visual programming, live dashboards, and structured experimentation can significantly improve comprehension of distributed communication patterns [24]. These approaches demonstrate that reducing environmental complexity and providing guided, observable experimentation are key to effective IoT protocol learning.

Drawing on these insights, our platform extends prior approaches by combining hands-on MQTT exercises with AI-supported guidance. Similar to remote IoT laboratories, the system reduces hardware and setup requirements, and like Node-RED-based instructional tools, it supports step-by-step exploration of protocol functions. In addition, our platform provides automated analysis and AI-generated hints to help learners understand key concepts without adding unnecessary cognitive load. Overall, this work refines and integrates ideas from earlier studies to offer a practical and beginner-friendly environment for learning MQTT communication concepts.

3. Preliminary

3.1. MQTT Protocol Overview

MQTT is a lightweight, publish/subscribe protocol. It is designed for resource-constrained environments, especially low-bandwidth and unreliable networks common in IoT applications. Unlike the traditional request–response model, MQTT decouples message publishers from subscribers through a central broker, enabling asynchronous communication.

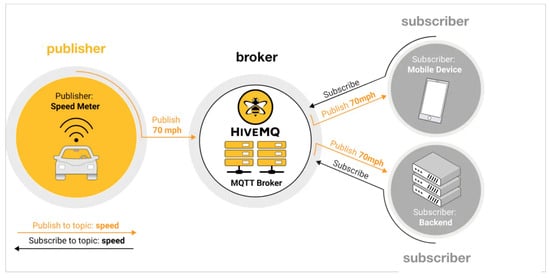

The MQTT architecture consists of three main components:

- Broker: Acts as the central server that receives messages from publishers and routes them to the appropriate subscribers.

- Client: Any device or application that connects to the broker. Clients can either publish messages or subscribe to receive them.

- Topic: A hierarchical UTF-8 string (e.g., home/livingroom/temperature) used by the broker to categorize and route messages.

Clients publish messages to specific topics, and the broker delivers these messages to all clients currently subscribed to those topics. This decoupled Pub/Sub model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

MQTT publish–subscribe model.

3.2. Challenges in Learning MQTT

While MQTT’s design is simple, its core mechanisms present significant challenges for beginners. These learning obstacles directly motivate the need for our platform.

3.2.1. The “Invisibility” of Asynchronous Communication

The asynchronous and decoupled nature of the Pub/Sub model poses a significant conceptual challenge. In a synchronous request–response model, a client receives immediate confirmation of success or failure. In MQTT, however, a publisher sends a message to the broker and “forgets” about it, with no direct indication of whether any subscribers received the message.

Although some tools can visualize message traffic, beginners still struggle because the model itself provides no built-in feedback. When a message fails to arrive, the underlying cause may be in the publisher’s logic, the broker’s configuration, or the subscriber’s topic string. Unlike synchronous programming, there is no immediate error message or stack trace to guide them.

This lack of direct feedback makes debugging extremely difficult for novices, necessitating a learning environment where this “invisible” message flow can be safely examined. Our platform addresses this by providing isolated exercises and an AI assistant that can diagnose these elusive asynchronous errors.

3.2.2. Abstract State Management Concepts

MQTT’s reliability features rely on abstract state-management concepts that are not intuitive for beginners.

- QoS: The behavioral differences among Level 0 (At most once), Level 1 (At least once), and Level 2 (Exactly once) are not obvious to beginners. The underlying handshakes and delivery guarantees are difficult to observe without dedicated debugging tools such as message inspectors or packet analyzers.

- Retained Messages: The idea that the broker stores and re-delivers the last valid message on a topic represents a form of broker-side state that is useful but not obvious to beginners.

- Last Will and Testament (LWT): If a client disconnects unexpectedly, the broker will send a preset message for it. This indirect behavior is hard for beginners to test and understand.

Learning these concepts requires repeated, controlled experimentation. Our platform’s use of disposable Docker containers for each exercise is a direct response to this challenge. It provides an isolated sandbox where learners can test one abstract concept at a time, free from the interference of “stale” states from a previous exercise.

3.2.3. Complexity of Topic and Session Configuration

MQTT’s flexibility in topic matching and session management creates common pitfalls.

- Wildcards: Mistakes with the single-level (+) or multi-level (#) wildcards are common. A small misuse can lead to subscribing to the wrong topics.

- Session State: Learners also struggle to predict the effects of Clean Sessions and Persistent Sessions. Whether a client starts fresh or receives queued messages depends on settings that are not immediately visible.

These configuration errors often cause MQTT programs to fail silently. This is exactly where our AI tutor adds value. The AI assistant can inspect a student’s configuration and code, detect these issues, and provide precise, context-aware hints that traditional materials cannot.

3.3. The SEMAR Platform as a Learning Context

The SEMAR platform [5] is an integrated IoT server system developed at Okayama University, designed for the unified management of large-scale IoT applications. It provides a flexible, modular architecture that connects diverse sensor networks using standardized protocols, including MQTT and RESTful APIs [25]. The platform supports real-time data acquisition, aggregation, and visualization, which has been successfully applied in real-world scenarios such as air and water quality monitoring.

In this study, the SEMAR platform serves as a key piece of pedagogical material for our advanced learning modules. While the full SEMAR system involves complex data analytics and multi-sensor integration, our system adopts a simplified version of its architecture to facilitate experiential learning. This adaptation retains the core mechanism of message publishing and subscription through an MQTT broker, allowing students to observe real-time data exchange in the context of a practical application. By examining SEMAR’s design, students can bridge the gap from theory to practice, exploring how MQTT enables data aggregation and system interoperability in a real-world IoT system.

4. Implementation

In this section, we present the implementation of the MQTT learning platform.

4.1. MQTT Learning Content

Traditional pedagogy for communication protocols like MQTT often presents two significant challenges for learners. First, there is a substantial gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, leaving students unable to effectively utilize their knowledge. Second, the learning curve is often uneven, with a steep increase in difficulty when introducing abstract core concepts. This sudden difficulty spike can lead to frustration and a loss of student engagement.

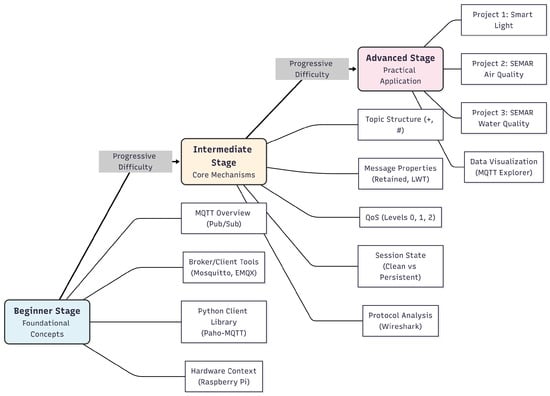

To address these challenges, our platform implements a progressive, three-stage educational framework. This framework is designed to smooth the learning curve by systematically scaffolding knowledge and integrating theory with hands-on practice. We divide the MQTT learning process into three stages, with each stage further broken down into multiple topics, as detailed below.

4.1.1. Beginner Stage: Foundational Concepts and Tools

This stage introduces the basic terminology, components, and the MQTT software ecosystem. Exercises consist of conceptual multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions. The AI assistant acts as a foundational knowledge tutor, answering questions and clarifying basic misconceptions about the setup.

- MQTT Overview: The Pub/Sub model and core architecture.

- Broker and Client Tools: Introduction to Mosquitto [26] and EMQX [27] as broker solutions, and using their client interfaces.

- Python Client Library: Setting up and using the Paho-MQTT [28] library for basic “connect”, “publish”, and “subscribe” operations.

- Hardware Context: Understanding the role of Raspberry Pi as a typical IoT client device for sensor data simulation.

4.1.2. Intermediate Stage: Core Protocol Mechanisms and Analysis

This stage dives into the abstract mechanisms that ensure reliable communication. Exercises transition to guided code-completion and micro-debugging. The AI assistant helps explain these abstract concepts and tracks student errors for targeted review. We designed this stage to end with network analysis. This allows students to use tools like Wireshark [29] to visually confirm how the abstract concepts actually work on a real network.

- Topic Structure: Topic matching using single-level (+) and multi-level (#) wildcards.

- Message Properties: Configuring Retained Messages and LWT.

- QoS: In-depth study of Level 0 (At most once), Level 1 (At least once), and Level 2 (Exactly once).

- Session State: Understanding the difference between Clean Sessions and Persistent Sessions, and their respective impact on subscriptions and message queuing.

- Protocol Analysis: Introduction to the MQTT Control Packet Format and using Wireshark for basic packet inspection to observe QoS handshakes or LWT triggers in action.

4.1.3. Advanced Stage: Practical Application and System Integration

This stage focuses on synthesizing all learned concepts into real-world projects. Exercises involve building complete applications from scaffolded code. The AI assistant evolves into a context-aware project mentor, providing debugging hints.

- Project 1: Smart Light Experiment: A simple control project where students publish commands to a topic to control a smart light bulb.

- Project 2: SEMAR Air Quality Monitoring: An integration project where students publish and subscribe to indoor air quality sensor data from a SEMAR module.

- Project 3: SEMAR Water Quality Monitoring: An integration project focused on publishing and monitoring water quality parameters from a SEMAR module.

- Data Visualization: Using MQTT Dashboards (MQTT Explorer [30]) to monitor live data streams.

This three-stage design directly addresses the pedagogical challenges. The intermediate stage acts as a bridge between simple definitions and complex projects. By introducing guided code-completion and micro-debugging, the platform smooths the learning curve. This approach allows students to practice configuring QoS or debugging Topics in a controlled, low-stakes environment before tackling a full project.

Furthermore, the role of the AI assistant evolves with the learner, transitioning from a foundational knowledge provider to a context-aware mentor. The AI provides this context by analyzing the learner’s submitted code and error output. This analysis allows it to provide specific, actionable hints rather than generic answers. The advanced projects then provide a comprehensive experience, allowing students to apply their knowledge in the context of the SEMAR platform, thus bridging the gap from theory to practice.

Figure 2 shows the overall learning content of the platform.

Figure 2.

Overall Learning Content.

4.2. MQTT Learning Platform

4.2.1. System Architecture

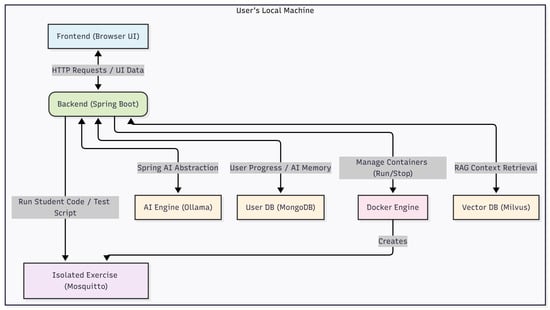

The architecture of the AI-assisted MQTT learning platform is designed around two foundational principles:

- Local-first, offline-capable operation to guarantee user privacy and accessibility without network dependency

- A modular, containerized backend capable of providing sandboxed learning environments and delivering intelligent, context-aware feedback.

The overall system topology is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Overall System Topology.

Table 1 summarizes the major software components used in the proposed learning platform. The table highlights each component’s role within the system architecture, illustrating how the backend, AI engine, vector store, and containerized execution environment collectively support reliable offline operation and pedagogically grounded feedback generation.

Table 1.

Software packages adopted in the proposed system and their primary functionalities.

4.2.2. Backend Foundation and AI Abstraction (Spring & Spring AI)

We selected Spring Boot [31] as it provides a stable foundation for the local application. Its primary role is to manage the interactions between the user interface and the backend services, including the AI engine and the Docker container lifecycle. We utilized the Spring AI [32] framework because it offers a clear abstraction layer for AI operations. This design simplifies development by decoupling the main application logic from the specific AI tools. This approach also supports future extensibility, allowing the AI engine or the vector store to be updated or replaced with minimal changes to the core code.

4.2.3. Local AI Engine (Ollama)

Our system uses Ollama [33] as the local AI engine for running lightweight LLMs. Compared with cloud-based APIs, Ollama is simple to deploy, requires relatively low hardware resources, and provides stable performance. Running models locally also avoids external API dependencies, reduces operational overhead, and keeps user data within the local environment, which is beneficial for system management and classroom deployment.

4.2.4. AI Knowledge Base (Milvus & RAG)

General-purpose LLMs often lack the specific knowledge required for a specialized domain, leading to potential hallucinations. To ensure pedagogical accuracy, we implemented a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [34] pipeline utilizing Milvus [35] as the vector database. We pre-process and vectorize our entire educational content, including detailed MQTT protocol documentation, SEMAR project specifications, and common troubleshooting solutions. When a student asks a question, the backend first retrieves relevant context from Milvus and injects it into the prompt for Ollama, ensuring the AI’s feedback is pedagogically accurate in our curriculum.

4.2.5. Isolated Exercise Environment (Docker & Mosquitto)

To deliver hands-on practice, we utilize Mosquitto [26], a widely-adopted open-source MQTT broker. The backend can manage Mosquitto broker instances via Docker images for each exercise session. This container-based deployment serves a specific pedagogical purpose: it addresses the common challenge of environment configuration and creates an isolated “sandbox”. This setup allows students to safely experiment with stateful concepts, ensuring that state from one exercise does not interfere with the next.

4.2.6. Primary Data Persistence (MongoDB)

For primary data persistence, we employ MongoDB [36]. User profiles, learning progress, and optionally saved exercises are stored in a MongoDB instance. Its flexible, document-based structure is ideally suited for managing the varied and evolving data schemas of an educational platform.

4.2.7. User Privacy Protection

The architectural decisions described above define the system’s data handling and privacy model. All components are packaged with Docker and run on the user’s local machine. As a result, the system operates fully offline. This local-first design improves privacy because no student data, code, or queries are sent to external servers.

To support personalization and the adaptive learning goals, the system includes an optional data-collection feature. Students can choose through the interface whether their learning data should be saved. When consent is given, the backend stores information such as submitted code, errors, and AI interactions in the user’s MongoDB instance. The system can then use this history in the RAG pipeline to provide more targeted feedback. This approach enables personalization while keeping all collected data on the local machine.

4.2.8. Tool Selection Rationale

In choosing the software components for the platform, we prioritized three criteria: local deployability, lightweight operation suitable for student laptops, and smooth integration with our Docker-based architecture. While alternative tools exist for each module, the selected ones best match our system constraints and team expertise. For example, vector databases such as FAISS or Chroma are also suitable, but we adopted Milvus due to its stable containerized deployment and consistent performance when handling larger embedding sets. Similarly, other local LLM runtimes (e.g., LM Studio, GPT4All) can serve comparable roles; however, Ollama offers the simplest cross-platform installation and model management for student use.

For the backend framework, both FastAPI and Node.js could have been used; nevertheless, we are more experienced with the Java ecosystem. Therefore, adopting Spring Boot and Spring AI allowed us to streamline development without compromising functionality, as these alternatives would have provided similar capabilities. Finally, MongoDB was selected over relational databases such as MySQL or PostgreSQL because its flexible document model better accommodates learning logs, user code, and other dynamically evolving data structures.

4.3. AI-Assisted Tutoring Mechanism

The AI assistant is a central pedagogical component of our platform, designed not as a simple “answer machine” but as an integrated tutor. Its implementation is centered on three key aspects: an intelligent tutoring strategy, a RAG pipeline for factual accuracy, and an AI memory for personalization. This design directly addresses the pedagogical risks of AI over-reliance discussed in Section 2.

4.3.1. Socratic Tutoring and Prompt Organization

Our primary Intelligent Tutoring Strategy is achieved through Prompt Engineering [37]. The AI is assigned the persona of a “Socratic Tutor” and operates based on a structured prompt template consisting of a system-level instruction, retrieved context from the RAG pipeline, and the student query. The system prompt defines the tutoring rules: the model must guide the learner through step-by-step questioning, avoid giving full solutions unless the student has already attempted the task, and always relate follow-up questions to the student’s submitted code or error message.

The Socratic behavior is implemented through explicit logic inside the system prompt. For example, if the query lacks evidence of student effort, the model is instructed to request the student’s code and ask them to identify the part they believe may be incorrect. When the student has already provided an attempt, the model analyzes their code and generates a sequence of scaffolding questions. This organized prompt structure produces consistent pedagogical behavior without requiring separate model fine-tuning.

4.3.2. AI Memory for Personalization

In addition to basic response accuracy, the platform offers personalized tutoring through a memory-based module. When a student provides consent, their interaction history, including submitted code, observed errors, and queries to the AI, is stored in the local MongoDB database. This history forms an individualized learning record. When the student later requests assistance, the AI can reference this record to detect recurring error patterns. This enables the system to generate more targeted follow-up exercises.

4.3.3. RAG for Factual Accuracy

To ensure the pedagogical accuracy of the AI’s responses and reduce the likelihood of hallucinated outputs, we implemented a RAG pipeline that functions as the system’s persistent knowledge source. All curriculum documents are first segmented into smaller chunks and converted into vector representations by the embedding models before being stored in the Milvus vector database. When a student submits a query, the Spring AI backend retrieves the most relevant context segments through similarity search, and these segments are then combined with the student’s original question to form a grounded prompt. This augmented prompt is forwarded to the local Ollama model, enabling the system to generate explanations that accurate and aligned with the course materials.

The RAG workflow is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

RAG Workflow.

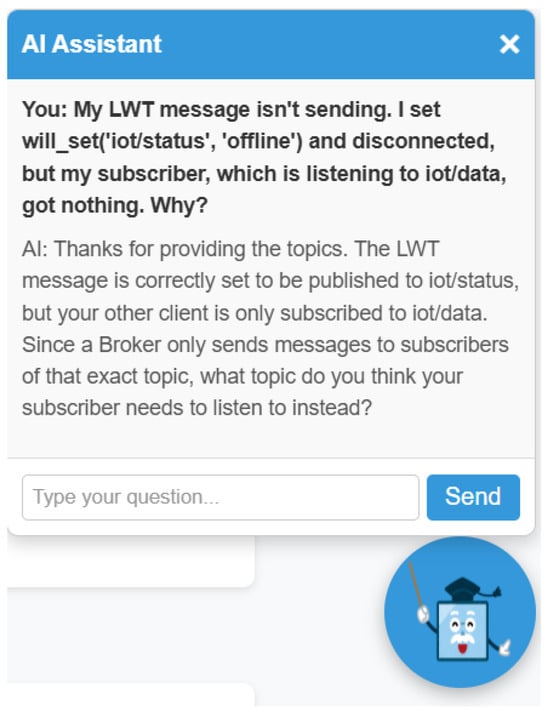

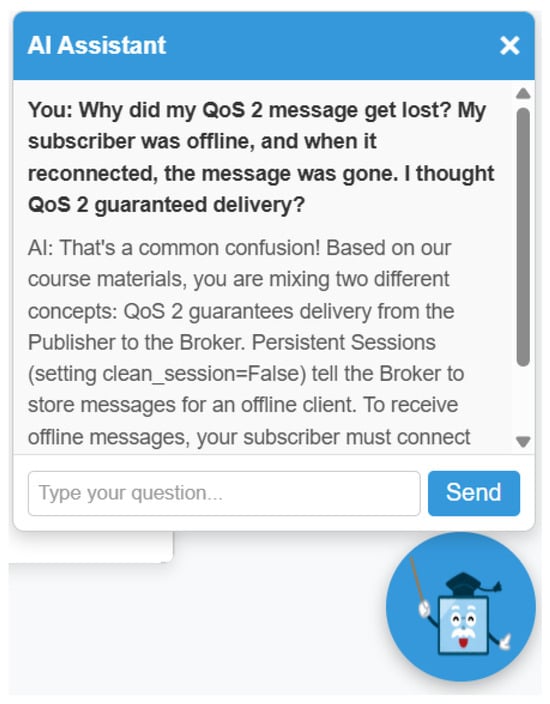

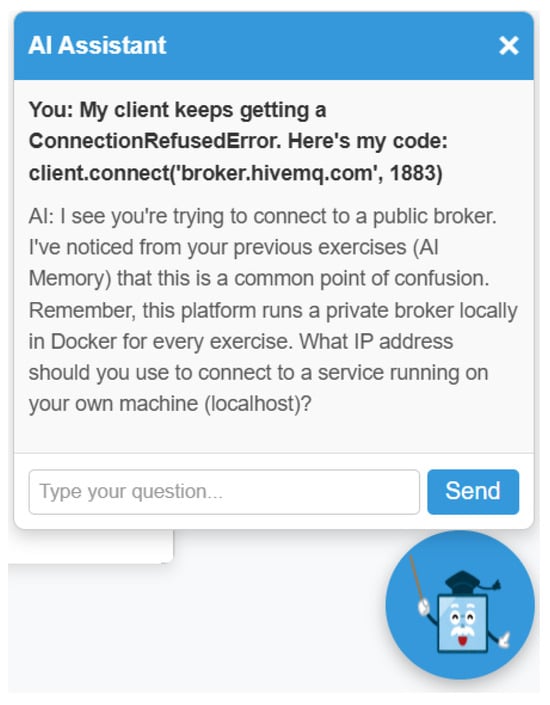

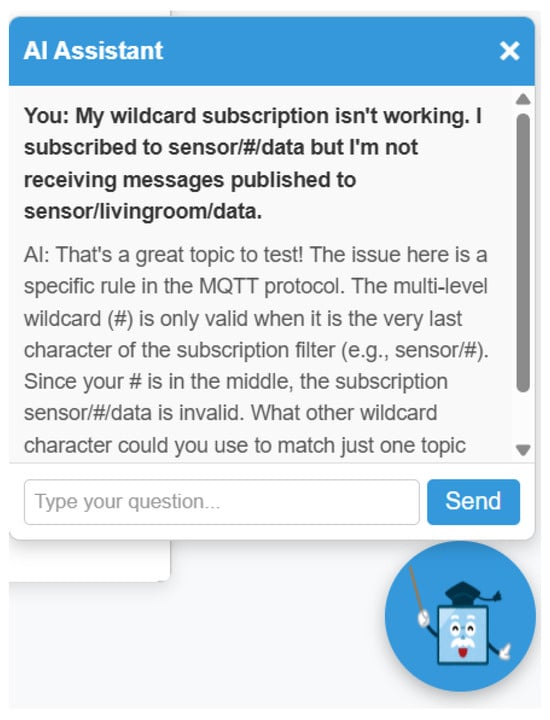

To visually demonstrate these mechanisms, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present typical conversation examples. Figure 7 illustrates the RAG-driven heuristic guidance, where the AI uses technical context from Milvus to help a student debug an “LWT” configuration. Figure 8 shows the filtering mechanism in action, where the AI refuses an off-topic request and then uses the AI Memory to provide personalized feedback on a repeated error.

Figure 5.

AI Conversation Example 1.

Figure 6.

AI Conversation Example 2.

Figure 7.

AI Conversation Example 3.

Figure 8.

AI Conversation Example 4.

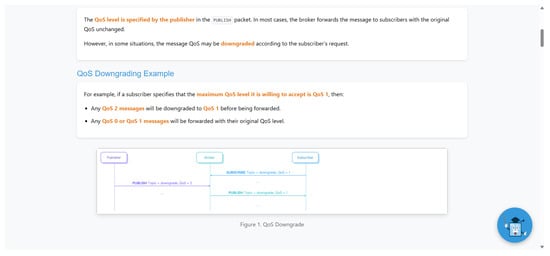

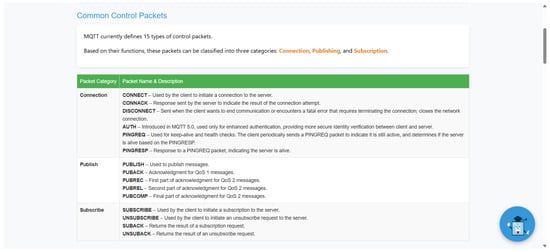

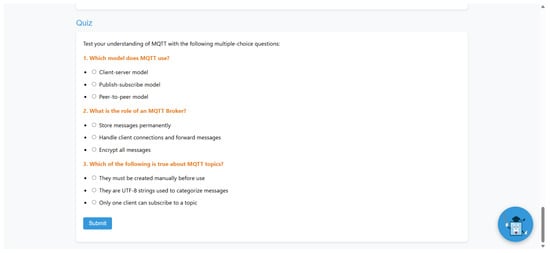

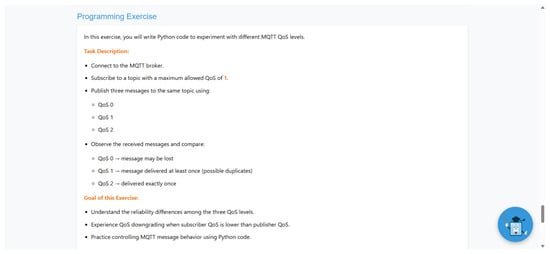

To illustrate how students interact with the platform, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 present representative screenshots from the user interface. Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the learning-content view. Figure 11 and Figure 12 display the practice-and-reinforcement interface, where students complete exercises and write code to conduct hands-on experimentation for reinforcement.

Figure 9.

System Usage Example 1.

Figure 10.

System Usage Example 2.

Figure 11.

System Usage Example 3.

Figure 12.

System Usage Example 4.

4.4. Docker-Based Deployment

4.4.1. The Need for Pedagogical Isolation

A key technical challenge in teaching networking protocols is ensuring a clean, reproducible, and isolated environment for every student and every exercise. Our platform addresses this challenge through a stand-alone containerization strategy using Docker. The deployment architecture is divided into two categories:

- Platform Image: This image contains all core components of the learning system, including the Spring Boot backend, the Ollama engine, the Milvus vector database, and the MongoDB user store. It is configured for local deployment which allows the student to launch the entire platform with a single command.

- Exercise Images: These images serve as isolated instructional environments that the platform manages dynamically. Each image provides a clean, self-contained sandbox for a specific exercise, ensuring that no residual state from previous tasks affects subsequent learning activities.

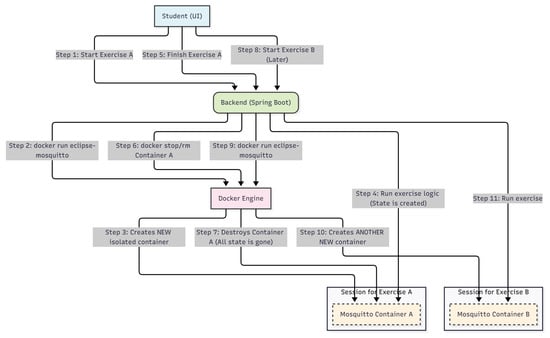

4.4.2. Dynamic Container Management

The primary reason for using Docker is to ensure pedagogical isolation and to prevent residual state from affecting subsequent exercises. The MQTT protocol maintains state by design. For example, a retained message published in one exercise persists in the broker. If the same broker instance were reused, this stale message could be delivered unexpectedly and could disrupt the intended learning objective. Similarly, queued messages from a persistent session may interfere with an exercise on clean sessions. The use of isolated Docker containers prevents these issues.

This isolation is implemented through dynamic container management handled by the Spring Boot backend. When a student begins a new hands-on task, the backend invokes a “docker run” command to start a clean “eclipse-mosquitto” container for that session. The container exists only for the duration of the exercise. After the student finishes the task or moves to a new module, the backend executes “docker stop” and “docker rm” to remove the container and all associated state. This short-term environment ensures that each exercise begins with a clean broker, which is essential for effective learning.

The dynamic container management workflow is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Dynamic Container Management.

4.5. Core Operational Logic

This section explains the step-by-step operational flow that a student experiences while using the platform, including both standard exercises and AI-assisted tutoring.

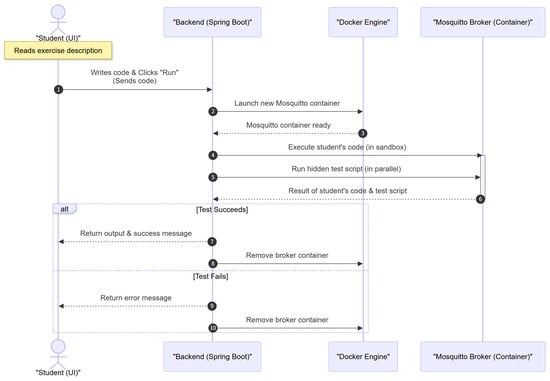

4.5.1. Standard Exercise Flow

This flow describes how a student completes an exercise without AI assistance. Each step is executed in a controlled and isolated environment to ensure reproducibility.

- The student reads the exercise description in the frontend interface.

- The student writes their Python code in the browser-based editor and clicks “Run”.

- The frontend sends the submitted code to the Spring Boot backend.

- The backend launches a clean Mosquitto container through Docker, creating a fresh broker instance for this exercise.

- The backend executes the student’s code in a sandbox and injects the connection parameters of the newly created broker.

- A hidden test script runs in parallel to verify whether the expected MQTT behavior occurred.

- If the test succeeds, the backend returns the program output and a success message to the UI. The broker container is then removed.

The exercise execution process is illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Standard Exercise Flow.

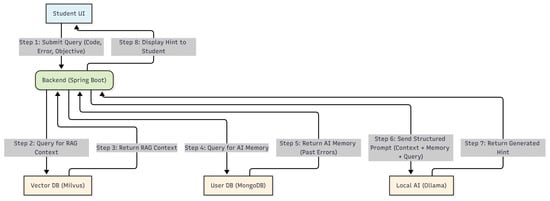

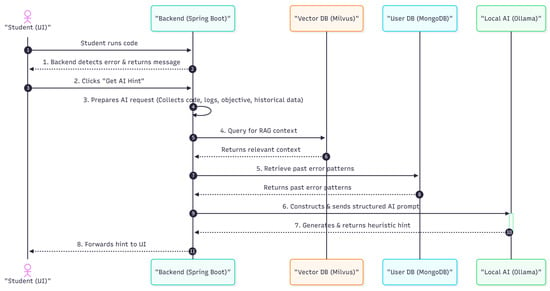

4.5.2. AI-Assisted Tutoring Flow

This flow is activated when the student encounters an error or explicitly requests help. It illustrates how the AI components support step-by-step debugging.

- The student runs their code, but the backend detects an error through the test script.

- The error message is returned to the UI, and the student clicks the “Get AI Hint” button.

- The backend prepares the AI request. It collects the student’s code, the error logs, the current learning objective, and any available historical data from MongoDB.

- The backend queries Milvus to retrieve relevant context for the RAG process.

- It then retrieves the student’s past error patterns from MongoDB.

- Using this information, the backend constructs a structured AI prompt and sends it to the local Ollama model.

- The model generates a heuristic hint that guides the student without providing the full solution.

- The backend forwards this hint to the UI, helping the student understand and correct the problem.

The AI-assisted tutoring workflow is illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

AI-Assisted Tutoring Flow.

5. Evaluation

To assess the effectiveness and usability of the proposed MQTT learning system, we designed an evaluation targeting two distinct user groups (beginners and advanced learners).

We collected both subjective usability data and objective learning-outcome data.

- Subjective data was gathered using the System Usability Scale (SUS) [38] and a post-task Likert questionnaire [39].

- Objective data was measured using task completion rates, time on task, and performance on practical application tasks.

Finally, we also evaluated the system’s technical performance for local deployment.

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

We defined two categories of metrics to evaluate the platform.

5.1.1. Subjective Usability Metrics

- System Usability Scale (SUS): We used the standard 10-item SUS questionnaire to measure perceived usability. The 10 items are:

- 1.

- I think that I would like to use this system frequently.

- 2.

- I found the system unnecessarily complex.

- 3.

- I thought the system was easy to use.

- 4.

- I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this system.

- 5.

- I found the various functions in this system were well integrated.

- 6.

- I thought there was too much inconsistency in this system.

- 7.

- I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly.

- 8.

- I found the system very cumbersome to use.

- 9.

- I felt very confident using the system.

- 10.

- I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system.

- Post-Task Survey (Likert): We also used a 5-point Likert scale survey to measure perceived learnability, confidence, and the utility of the AI assistant.

- Qualitative Feedback (Free Description): Open-ended questions asking participants for their opinions on the system’s strengths and weaknesses.

5.1.2. Objective Learning-Outcome Metrics

- Task Completion Rate (TCR): The percentage of participants in each group who successfully completed all assigned learning tasks.

- Time on Task (ToT): The average time required for participants to complete the full set of modules.

- Application Ability Score: Participants applied the knowledge they learned to build a small application. Performance was evaluated using a simple scoring system (Pass/Fail and 0–10) based on clear grading criteria.

5.2. Evaluation with Beginner-Level Participants

To evaluate the suitability of the system for introductory learning, we invited ten students who had previously completed a Python programming course but had no prior experience with MQTT. The participants completed the beginner learning modules, including basic publish/subscribe operations and simple topic-based messaging experiments.

After completing the exercises, participants were asked to complete the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire and a short post-task survey (5-point Likert) covering Ease of Use, Learnability, Confidence, and the perceived utility of the AI assistant. Table 2 summarizes the aggregated results. For each metric we report the sample mean and the 95% confidence interval (CI) computed with Student’s t-distribution (degrees of freedom = 9).

Table 2.

SUS and questionnaire results for beginner-level participants (). 95% CIs are shown in brackets.

Furthermore, objective learning outcomes were measured to assess actual effectiveness. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Objective learning outcomes for beginner-level participants ().

9 out of 10 participants successfully completed all beginner tasks. The average time to complete the modules was 45.2 min. In the final application challenge, 7 out of 10 participants were able to successfully apply the concepts.

Qualitative feedback from free-text descriptions was positive. One user noted, “The isolated Docker environments were the best part. I could experiment without fear of breaking anything or getting confused by old data.” while another suggested “I sometimes wished the AI could be more direct. When I was really stuck on a connection error, the Socratic hints were a bit slow, and I just wanted to know the line of code I got wrong.”

The results indicate that the system provided a clear and accessible learning experience for beginners. Most participants were able to complete the beginner-level exercises successfully and reported improved understanding of basic MQTT concepts and message flow after the session. Furthermore, qualitative feedback regarding the AI assistant was positive.

5.3. Evaluation with Intermediate/Advanced-Level Participants

To examine the system’s suitability for learners with prior networking or MQTT experience, we invited ten participants who had prior exposure to network programming or MQTT. These participants completed the intermediate and advanced modules, which included multi-topic subscriptions, QoS configuration, retained messages, and reconnection strategies.

As with the beginner group, participants completed the SUS questionnaire and a short survey (5-point Likert) tailored to advanced usage (Ease of Use, Support for Understanding Concepts, and Usefulness for Practical MQTT Operation). Table 4 shows the aggregated results with 95% CIs.

Table 4.

SUS and questionnaire results for intermediate/advanced participants (). 95% CIs are shown in brackets.

Furthermore, objective learning outcomes were measured to assess actual effectiveness. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Objective learning outcomes for advanced-level participants ().

7 out of 10 participants successfully completed all advanced tasks. The average time to complete the modules was 93.6 min. In the final application challenge, 6 out of 10 participants were able to successfully apply the concepts.

Qualitative feedback from free-text descriptions was positive. One user noted, “The AI assistant was accurate. When debugging the SEMAR project, it correctly referenced the protocol’s mechanism.” while another suggested “I would like to see more advanced modules. The SEMAR projects were a great start, but I’d also want to see exercises on MQTT 5.0 features.”

Qualitative feedback collected during brief post-session interviews indicated that experienced participants particularly valued the AI’s RAG-based, context-aware feedback and the hands-on scenario exercises. The SUS and survey scores suggest that the system is perceived as usable and helpful for consolidating practical MQTT skills.

5.4. System Performance Testing

Given the system’s stand-alone, local-first architecture, performance testing focused on the viability of running the entire platform on a typical student’s machine. We measured key performance metrics related to local AI responsiveness, container orchestration, and resource consumption.

Tests were executed on a PC equipped with an Intel i5-11400H CPU and 16 GB RAM, which is representative of a modern student laptop. The full platform (Spring Boot, Ollama with a 1-billion parameter LLM (llama3.2:1b) and a 0.3-billion parameter embedding model (embeddinggemma:300m), Milvus, MongoDB) was deployed locally.

Table 6 shows local system performance benchmarks. The results were obtained by taking the average of results over 20 test runs.

Table 6.

Local system performance benchmarks.

The performance results confirm that the system is viable for its intended local deployment. An AI response time of approximately 4.8 s is acceptable for a non-real-time tutoring context, providing a detailed, heuristic hint. The Docker container startup time of 5.2 s is sufficiently fast for seamless transitions between exercises. The primary performance consideration is the system’s RAM footprint (≈5.8 GB idle), which is significant due to the locally loaded LLM and vector database, but manageable for most modern student laptops.

5.5. Summary of Evaluation

The three-part evaluation collectively demonstrates that the proposed MQTT learning system is:

- Usable and accessible for learners with little or no prior MQTT experience (beginner group SUS ≈ 78);

- Supportive for learners with intermediate/advanced backgrounds (advanced group SUS ≈ 82), with quantitative and qualitative feedback from both groups confirming the value of the RAG-based AI feedback for debugging and learning.

- Effective for Learning: The system demonstrated strong learning outcomes, with high task completion rates and measurable success in the final application tasks for both groups.

- Performant for Local Deployment, with acceptable AI response times (≈4.8 s) and container startup times (≈5.2 s) on standard student hardware. The main trade-off for its local-first, privacy-preserving design is a notable (but manageable) system memory requirement.

Overall, the evaluation results indicate that the system effectively supports learners across skill levels and operates reliably for interactive, real-time pedagogy.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented an AI-assisted, exercise-based learning platform designed to address common challenges in teaching the MQTT protocol. These challenges include the steep learning curve and the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Our primary contribution is a stand-alone and local-first system that protects student privacy and removes external dependencies.

The platform’s design combines two main features:

- It uses a local-first AI engine (Ollama) with a RAG pipeline (Milvus) to provide guided feedback. The RAG pipeline helps the AI provide correct answers based on the course materials, which reduces the risk of LLM hallucination.

- It uses Docker to provide new, separate Mosquitto broker instances for each exercise. This approach is important for creating an isolated learning environment. It prevents leftover data from one exercise from interfering with the next. This makes each exercise a clean and predictable sandbox.

As shown in our evaluation (Section 5), the results from our usability study confirmed that this approach helps reduce learner frustration and increase engagement. Overall, this work demonstrates a practical method for overcoming common MQTT teaching challenges and provides a framework that can be adapted to other technical subjects requiring safe, repeatable, and concept-focused hands-on practice.

Scalability and Future Extensions

While the evaluation results are positive, the platform’s modular design allows for several future improvements. At the same time, it is important to clarify the current scope and design assumptions of the system.

First, the educational content (Section 4.1) can be expanded. The current platform focuses on core MQTT concepts, such as the publish–subscribe model, topic hierarchies, QoS levels, retained messages, and basic session behavior, while deliberately abstracting away broker-level configurations and advanced protocol concerns. These include scalability, high-concurrency deployment, and production-level security mechanisms, which are beyond the scope of the present educational system. In future work, we plan to add more learning modules to cover a wider range of IoT protocols, such as CoAP [40] or AMQP [41], providing a broader IoT communication curriculum. We also plan to introduce advanced modules covering MQTT 5.0 features and secure communication practices.

Second, the system’s AI integration was designed for flexibility. Our use of the Spring AI framework (Section 4.2.1) as an abstraction layer decouples the backend logic from any single LLM. This design enables the platform to be updated with newer AI models as they become available, without requiring substantial changes to the system architecture.

Third, improved exception handling is necessary to further enhance system robustness. Future work will focus on improving how the backend manages the Docker container lifecycle, such as handling port conflicts, resource contention, or image-pull failures. In addition, we plan to strengthen the secure sandbox used for executing student code, which would enable the collection of more precise runtime and diagnostic information to better support AI-assisted feedback.

Finally, while the current system adopts a local-first, single-user, and offline architecture that is well suited for privacy-preserving self-study, this deployment model also introduces inherent limitations. A cloud-based version of the platform could better support classroom or laboratory settings, where instructors may wish to monitor student progress or manage learning activities across multiple users. Such a deployment would require significant architectural changes, including multi-user session management, user authentication, access control, secure data handling, and scalable orchestration of broker instances, for example through container orchestration frameworks such as Kubernetes. Although these extensions are beyond the scope of this work, they indicate how the proposed system can be extended to more complex deployment scenarios while preserving its educational focus.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.Z., I.N.D.K., A.A.S.P., A.A.R. and N.; Software, Z.Z.; Investigation, Z.Z., I.N.D.K., A.A.S.P., A.A.R. and N.; Data curation, Z.Z., I.N.D.K., A.A.S.P., A.A.R. and N.; Writing—original draft, Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Z.Z. and N.F.; Supervision, N.F. and H.H.S.K.; Project administration, N.F. and H.H.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MQTT: The Standard for IoT Messaging. Available online: https://mqtt.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Python Software Foundation. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Docker Official Website. Available online: https://www.docker.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- RaspberryPi.org. Raspberry Pi: The Official Website. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Panduman, Y.Y.F.; Funabiki, N.; Puspitaningayu, P.; Kuribayashi, M.; Sukaridhoto, S.; Kao, W.-C. Design and Implementation of SEMAR IoT Server Platform with Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ari, M. Constructivism in Computer Science Education. J. Comput. Math. Sci. Teach. 2001, 20, 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. A constructivist approach to teaching: Implications in teaching computer networking. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2003, 21, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory and computer science education. In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Science Education, Memphis, TN, USA, 2–5 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pirker, J.; Riffnaller-Schiefer, M.; Gütl, C. Motivational active learning: Engaging university students in computer science education. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Innovation & Technology in Computer Science Education, Uppsala, Sweden, 23–25 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roig, P.J.; Alcaraz, S.; Gilly, K.; Bernad, C.; Juiz, C. An Active Learning Approach to Evaluate Networking Basics. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manorat, P.; Tuarob, S.; Pongpaichet, S. Artificial intelligence in computer programming education: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Liu, D.; Zhang, R.; Pan, L. The impact of AI-assisted pair programming on student motivation, programming anxiety, collaborative learning, and programming performance: A comparative study with traditional pair programming and individual approaches. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2025, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçapınar, G.; Sidan, E. AI chatbots in programming education: Guiding success or encouraging plagiarism. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coding Rooms. Coding Rooms: Developer Training & Enablement Platform. Available online: https://www.codingrooms.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Khan Academy. Khan Academy: For Every Student, Every Classroom. Real Results. Available online: https://www.khanacademy.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Khanmigo. Khanmigo: An AI-powered Tutor and Teaching Assistant. Available online: https://www.khanmigo.ai/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- GitHub Copilot. GitHub Copilot: Your AI Pair Programmer. Available online: https://github.com/features/copilot (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.-Q. Research on Teaching IoT Courses in the New Engineering Education Framework for Postgraduate Students. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, Haikou, China, 18–20 October 2025; pp. 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Fitria, T.; Simbolon, N.; Afdaleni. Internet of Things (IoT) in Education: Opportunities and Challenges. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377063523_Internet_of_Things_IoT_in_Education_Opportunities_and_Challenges (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- PS, A.; Dilip Kumar, S.M.; KR, V. MQTT Implementations, Open Issues, and Challenges: A Detailed Comparison and Survey. Int. J. Sens. Wirel. Commun. Control 2022, 12, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrada Tivani, A.E.; Murdocca, R.M.; Sosa Paez, C.F.; Dondo Gazzano, J.D. Didactic Prototype for Teaching the MQTT Protocol Based on Free Hardware Boards and Node-RED. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2020, 18, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhelo, J.; Robles, A.; Martin, S. Internet of Things Remote Laboratory for MQTT Remote Experimentation. In International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Ambient Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, M.; González-Herbón, R.; Rodríguez-Ossorio, J.R.; Fuertes, J.J.; Prada, M.A.; Morán, A. Development of a Remote Industrial Laboratory for Automatic Control Based on Node-RED. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 17210–17215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksmi, I.C.; Hatta, P.; Wihidayat, E.S. A Systematic Review of IoT Platforms in Educational Processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Istanbul, Turkey, 7–10 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- RESTfulAPI.net. REST API Tutorial: What is REST? Available online: https://restfulapi.net/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Eclipse Mosquitto: An Open Source MQTT Broker. Available online: https://mosquitto.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EMQX: The World’s Most Scalable MQTT Broker. Available online: https://www.emqx.io/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Eclipse Paho: MQTT and MQTT-SN Client Implementations. Available online: https://eclipse.dev/paho/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wireshark: The World’s Foremost Network Protocol Analyzer. Available online: https://www.wireshark.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- MQTT Explorer: An MQTT Client for Visualization and Debugging. Available online: https://mqtt-explorer.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Spring Boot: Takes an Opinionated View of Building Spring Applications. Available online: https://spring.io/projects/spring-boot (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Spring AI: AI Engineering for Spring Developers. Available online: https://spring.io/projects/spring-ai (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ollama: Run Large Language Models Locally. Available online: https://ollama.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (Neurips) 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Milvus: An Open-Source Vector Database for AI Applications. Available online: https://milvus.io/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- MongoDB: The Developer Data Platform. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Sahoo, P.; Singh, A.K.; Saha, S.; Jain, V.; Mondal, S.; Chadha, A. A Systematic Survey of Prompt Engineering in Large Language Models: Techniques and Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2402.07927. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A ’quick and dirty’ usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Weerdmeester, B.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jebb, A.T.; Ng, V.; Tay, L. A review of key Likert scale development advances: 1995–2019. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 637547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CoAP: Constrained Application Protocol. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc7252/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- AMQP: Advanced Message Queuing Protocol. Available online: https://www.amqp.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).