Abstract

In this article, we present a tool for matching resumes to job posts and vice versa (job post to resumes). With minor modifications, it may also be adapted to other domains where text matching is necessary. This tool may help organizations save time during the hiring process, as well as assist applicants by allowing them to match their resumes to job posts they have selected. To achieve text matching without any model training (zero-shot matching), we constructed dynamic structured prompts that consisted of unstructured and semi-structured job posts and resumes based on specific criteria, and we utilized the Chain of Thought (CoT) technique on the Mistral model (open-mistral-7b). In response, the model generated structured (segmented) job posts and resumes. Then, the job posts and resumes were cleaned and preprocessed. We utilized state-of-the-art sentence similarity models hosted on Hugging face (nomic-embed-text-v1-5 and google-embedding-gemma-300m) through inference endpoints to create sentence embeddings for each resume and job post segment. We used the cosine similarity metric to determine the optimal matching, and the matching operation was applied to eleven different occupations. The results we achieved reached up to 87% accuracy for some of the occupations and underscore the potential of zero-shot techniques in text matching utilizing LLMs. The dataset we used was from indeed.com, and the Spring AI framework was used for the implementation of the tool.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving recruitment landscape, organizations must navigate a vast number of resumes to identify the most suitable candidates, making the need for automated solutions increasingly critical. Conversely, job seekers increasingly require intelligent tools to structure their resumes and match them effectively with relevant job postings. Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) have markedly improved the precision and efficiency of information extraction from both resumes and job posts. This process entails parsing these documents to identify essential components—such as work experience, education, skills, and other attributes. Once extracted, the information can be organized according to predefined criteria, facilitating not only a more streamlined and accelerated recruitment process but also more accurate bidirectional matching between resumes and job posts. This article introduces a specialized zero shot text-matching tool designed to match resumes with job posts—and conversely—to assist both employers and job seekers in identifying the most suitable matches. The proposed tool is highly adaptable and can be configured for use in other domains requiring document or paragraph similarity assessment.

Recent developments in LLMs have demonstrated their capacity to generate structured outputs from natural language input when guided by carefully structured prompts [1,2]. Leveraging this capability, we applied the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting technique [3,4,5,6] with the Mistral chat model (open-mistral-7b) [7] to extract and organize information from unstructured and semi-structured text, specifically from resumes and job posts. The unstructured text refers to natural language data that lacks a predefined organizational format or schema, making it difficult to process using conventional techniques.

This approach enabled the segmentation of each document into predefined schema components, such as title, description, responsibilities, education, experience, skills, and additional information. For the generated schema of resumes and job posts, we leveraged the zero-shot technique, wherein the models interpreted instructions or prompts to perform the task directly, without any additional training or fine-tuning. This method was selected to exploit the pretrained models’ generalization capabilities, allowing semantic understanding across diverse textual content and reducing the need for domain-specific labeled data, thereby improving both the adaptability and scalability of the matching tool.

The dataset used in this study comprised real-world data collected from Indeed.com, covering eleven distinct occupations—five utilized for job post-to-resume matching and six for resume-to-job post matching experiments.

Following data segmentation, we employed two state-of-the-art sentence similarity models—Google’s embedding-gemma-300m [8] and Nomic’s nomic-embed-text-v1.5 [9]—via Hugging face inference endpoints to generate vector embeddings for each segment of the resumes and job posts. These embeddings were temporarily stored in the system cache to enable efficient and scalable similarity computations during the matching phase. The cosine similarity metric was used to measure the accuracy of the proposed matches.

Our research’s primary objective aimed to develop a versatile text-matching tool primarily optimized for matching resumes with job posts and vice versa, with the potential for adaptation to other domains through minimal modifications. To achieve our goal, a novel algorithmic approach was developed utilizing structured prompts, CoT, and state-of-the-art embedding models, which also bypasses model training costs by utilizing the pre-trained model’s knowledge. The tool is designed to support both organizational use and individual users, allowing effortless and controlled matching.

The matching procedure is fully end-to-end supervised and user-guided, mitigating the risk of model hallucinations and ensuring that outputs remain interpretable and reliable. This approach combines flexibility, domain-agnostic applicability, and user oversight to enhance both the practical utility and trustworthiness of automated applications utilizing the zero-shot technique [10,11,12,13].

To the best of our knowledge, there are not many research papers on tools/applications for resume–job post matching leveraging LLMs. Despite rapid technological progress in this domain, existing academic literature remains limited, reflecting the field’s emerging and fast-evolving nature.

The article begins by reviewing related work in the field of tools for job post to resumes matching, especially those that leverage LLMs. We then proceed to outline the methodology we adopted for the matching problem. An overall description is given of the datasets we used for evaluation. This is followed by a discussion, in parts, of the architecture we chose for our experiments. Afterward, we present and analyze the results from our experiments. The article concludes with insights and suggestions for potential future research in this area.

2. Previous Work

Bevara R.V.K. et al. [14] introduced an innovative transformer-based framework, Resume2Vec, which uses intelligent resume embeddings leveraging models such as BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, GPT-4.0, Gemini, and Llama, which convert both resumes and job postings into embeddings; these embeddings are then computed to capture nuanced relationships between resumes and job descriptions. Dr. Pritesh Patil et al. introduced JobMatchr [15], a web-based artificial-intelligence-powered system that automatizes recruitment by analyzing resumes using job descriptions. Although the application leverages LLMs, it does not utilize their NLP capabilities for structured output and dynamic text segmentation. Prasad Dhobale et al. created ResuMatcher [16], an AI-powered resume-ranking system that also leverages LLMs for semantic understanding. It performs context evaluation for terms and their meaning in resumes and job descriptions. The system uses the BERT model and transformer-based architectures. Jingran Sun [17] developed a resume–job intelligent matching system specifically designed for the hotel industry based on LLM technology and conducted an in-depth analysis of its adaptability performance across different position types within the industry. The experiments employed LoRA fine-tuning techniques for domain adaptation of the BERT model and designed a multi-dimensional matching algorithm integrating skills, experience, and soft-skills evaluation.

G. Vagale et al. utilized Google’s Gemini Pro Vision LLM and NLP techniques to analyze and compare resumes or CVs with job descriptions [18]. Gemini processes a resume as a Base64-encoded string and cleans up the job description using NLP. It then generates a personalized report with insights, including a compatibility score, skills analysis, improvement suggestions, and resource recommendations. F. Haneef et al. [19] created a platform that leverages LLMs to extract key information, such as skills, education, and work experience, from both resumes and job descriptions. They fine-tuned the model through prompt engineering, and to further enhance matching accuracy, they employed Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques.

Archana V. Ugale et al. [20] in their research utilize machine learning algorithms and NLP techniques to achieve optimal matching between job posts and resumes. The resumes are clustered into groups based on their qualifications and experience. Each cluster contains resumes that are similar in terms of key skills, education, or career experience. Once the resumes are grouped, the job description is matched only against the most relevant clusters. After the job descriptions are matched with the resumes in the selected clusters, each resume receives a ranking based on its similarity score.

Spandana Anilkumar Kamkar et al. [21], leveraging NLP techniques, SpaCy, and machine learning models, extracted relevant skills, experience, and qualifications by parsing resumes and job descriptions. They analyzed textual data and applied advanced algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM). Their system learns to match candidates with job postings based on keyword relevance and contextual understanding.

Lo, F.P.-W et al., in their paper, propose a multi-agent framework for automated resume screening, utilizing LLMs enhanced with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [22]. They utilized four agents to perform resume information extraction, evaluation, summarization, and score formation. Zhi Zheng et al. presented the Generative Job Recommendation based on Large Language Models-GIRL [23]. They initially employed a Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) strategy to instruct the LLM-based generator in crafting suitable Job Descriptions (JDs) based on the Curriculum Vitae (CV) of a job seeker. They trained a model that can evaluate the matching degree between CVs and JDs as a reward model, and used a Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)-based Reinforcement Learning (RL) method to further fine-tune the generator. GIRL serves as a job seeker-centric generative model, providing job suggestions without the need for a candidate set.

3. Methodology

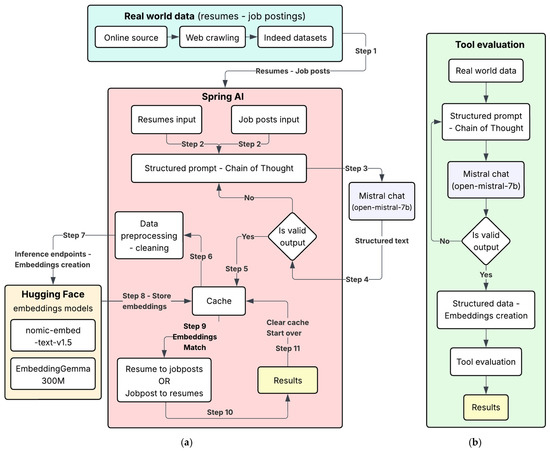

Our methodology for matching a resume to job posts and vice versa (job post to resumes) comprised several steps, as illustrated in Figure 1. The initial step involved collecting a diverse dataset of both unstructured and semi-structured resumes and job posts from https://www.indeed.com/. Depending on the match operation (resume to job posts OR job post to resumes), the dataset was fed to the Spring AI endpoints (Step 1). For each request, concerning a resume or a job post, a structured prompt was generated utilizing the CoT technique for text segmentation per topic of resume–job post, e.g., title, skills, education, etc., utilizing the NLP capabilities of the model (Step 2). The constructed request was fed as input to Mistral chat model (Step 3).

Figure 1.

(a) Overall tool design, (b) the tool’s evaluation flow.

The tool evaluated Mistral’s response; another structured request would be sent if, and only if, the generated text in the previous response was not constructed according to the given schema specifications (Step 4). The generated text, according to schema specifications, was temporarily stored in the tool’s cache for further calculations (Step 5). The textual content of the segments was cleaned of any superfluous special characters and numerical figures (Step 6) and then fed through Hugging face inference endpoints to two embedding models, Google’s embedding-gemma-300M and Nomic’s nomic-embed-text-v1.5, to create embeddings for each segment (Step 7). The responses from the endpoints were stored in the tool’s cache (Step 8) for each model.

We selected the match operation and the tool performed the requested action (Step 9) calculating the best match applying the cosine similarity metric for each generated embeddings from the two models. The tool created a file in xlsx format and presented gemma’s and nomic’s results ranking (Step 10) in descending order according to Google’s model, as it is the current state of the art, for both actions. At (Step 11), we evicted the data in the cache and started a new matching operation with new resumes–job posts.

For the evaluation of the tool, we followed a slightly different flow. A file in xlsx format (for job posts or resumes) was created which was fed to the tool and evaluated presenting the results in descending ranking according to Google’s model.

4. Materials and Methods

This section presents the approach underlying the construction of the datasets, examines the design of the structured prompts fed to the Mistral chat model, specifies the configuration of the embedding models employed, and outlines the architectural framework of the proposed tool.

4.1. Data Collection—Manipulation

In our study, we selected a comprehensive list of job posts and resumes that span a diverse range of professions and specialties. This selection enabled a thorough evaluation of the tool’s efficiency across various distinct job posts and resumes. To ensure clarity and brevity in the presented graphs in Appendix A, we assign an ID number to each job post and resume file name. The Indeed datasets utilized for the evaluation and testing of the tool are a subset of the datasets used in our previous research work for multiclass classification of job posts [24].

The datasets were sourced using a systematic approach facilitated by web crawlers. Queries were strategically crafted and fed into a resume–job post search engine, which subsequently produced a list of search results. The content from these results was diligently cataloged within a database, each paired with its corresponding occupation label. This iterative process continued until an ample volume of data was gathered.

It is important to highlight that the search results were algorithmically generated, emphasizing the most relevant outcomes. These results were carefully arranged to prioritize relevance, influenced by factors such as textual content matching the exact terms of the search queries and the temporal attributes of the resumes. The latter took into account when a resume or a job post was first uploaded and its last modification date, serving as indicators of changes in the individual’s professional trajectory.

To guarantee data quality and uniformity, the dataset underwent an extensive cleansing process. This involved eliminating invalid characters, non-word entities, and discarding resumes or job posts that might be unsuitable due to the occasional retrieval of incorrect or unrelated data by web crawlers during the collection phase. The job posts and resumes span a diverse range of professions and specialties such as Lawyers, Automotive Technicians, Web Developers, Civil Engineers, Dental Assistants, Bankers, Software Engineers, Chef, Marketing Managers, etc.

4.2. Structured Prompts—CoT

A structured prompt constitutes a systematically organized input that directs the LLM’s reasoning trajectory by explicitly defining task instructions, contextual parameters, and expected outputs. When combined with a chain-of-thought (CoT) approach, the prompt guides the generated response but also elicits intermediate reasoning steps, enhancing transparency and interpretability in model outputs. This integration facilitates more robust logical sequencing and mitigates the model’s tendency toward superficial or heuristic responses. With the zero-shot technique—where the model receives no prior examples or fine-tuning—the structured prompt serves as the primary mechanism for task specification, compensating for the absence of explicit training data. The interaction among these components enables improved generalization and reasoning consistency.

Chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning combined with zero-shot prompting involves guiding a language model to produce structured, multi-step explanations without providing task-specific examples. In this approach, the model is prompted to articulate intermediate reasoning steps directly from an instruction alone, enabling it to decompose complex problems, apply implicit knowledge, and arrive at more accurate conclusions. Zero-shot CoT methods therefore leverage the model’s pretrained reasoning capabilities while maintaining minimal prompt overhead, making them effective for tasks requiring interpretability and systematic multi-step inference across diverse domains.

Our study presents an automated prompt-engineering approach that integrates structured prompts with chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning in the Mistral language model under a zero-shot configuration. Structured prompts were generated through the Spring AI framework, where Message objects—embodying a predefined schema and its CoT paradigm—were encapsulated within a Prompt object and fed as model input. Iterative re-prompting ensured adherence to the schema until valid output was produced. The zero-shot approach enhanced generalization, reduced dependence on labeled data, and improved adaptability across heterogeneous inputs.

A unified schema, comprising title, description, responsibilities, education, skills, experience, and additional information, was applied to both job postings and resumes to maintain structural consistency and optimize semantic processing.

This design transformed unstructured or semi-structured text into a coherent, schema-aligned format, enabling uniform representation across diverse inputs. By leveraging the NLP capabilities of the Mistral model, this unification formed a foundational step for reliable embedding generation and accurate semantic matching of the tool.

4.3. Models

We utilized SmolLM2-1.7B [25], Qwen3-1.7B [26], and Mistral-7B as chat models to generate a unified structured schema for job postings and resumes. Each model produced structured outputs; we validated and selected the most accurate schema. During testing, SmolLM2-1.7B and Qwen3-1.7B achieved less than 10% valid task completion, frequently exhibiting hallucinations, whereas Mistral-7B successfully completed 90% of tasks. When combined with iterative structured prompting, Mistral-7B achieved full (100%) schema compliance. The model was configured with a temperature of 0.7, Top-p (Nucleus Sampling): 1.0 (default) and unrestricted token generation. Mistral-7B was accessed through the Spring AI framework at no cost, while Qwen3-1.7B and SmolLM2-1.7B were utilized via Hugging face inference endpoints at a rate of USD 0.80 per hour. Table 1 summarizes the results.

Table 1.

Model comparison.

In our study, we employed three state-of-the-art embedding models—Mistral Embeddings, Google’s embedding-gemma-300M (Gemma), and Nomic’s nomic-embed-text-v1-5 (Nomic)—to convert the structured schemas of resumes and job postings into vector representations. The Mistral embedding model generated 1024-dimensional vectors, while Gemma and Nomic produced 768-dimensional vectors. During testing, the Mistral embedding model exhibited high latency and frequent quota-exceeding errors despite moderate payload sizes, whereas Gemma and Nomic demonstrated excellent stability and very efficient performance.

We conducted embedding requests to the Mistral model via the Spring AI framework, which provided plug-and-play templates through Maven dependencies and enabled direct communication with the mistral.ai infrastructure. In contrast, Gemma and Nomic models were accessed through Hugging face inference endpoints which offer a unified API enabling model selection via domain prefix configuration. Although the Mistral embedding model was freely available, it was ultimately excluded from use due to excessive latency and frequent quota-exceeding errors. The operational costs for the remaining models were USD 0.12 per hour for Gemma and USD 0.268 per hour for Nomic, respectively. The median response time for Nomic’s model was 0.187 s per request (approximately 1000 requests were sent), whereas Gemma was 0.92 s (approximately 600), respectively. Table 2 summarizes the overall processing time and cost per request. As an example, ranking 10 resumes to a job post or vice versa would take approximately 3 to 4.5 min.

Table 2.

Overall costs and processing time per request. A request is considered a resume or job post.

4.4. Tool Architecture—Functionality

In order to implement the matching tool, we utilized Spring AI which is a new application framework for AI engineering. Its main purpose is to apply to the AI domain Spring ecosystem design principles such as portability and modular design and promote using POJOs as the building blocks of an application in the AI domain. Spring Boot and Spring AI help integrate artificial intelligence models into enterprise contexts, using established patterns and ensuring the management of multiple providers without invasive changes to the code or technology stack. Table 3 presents the configuration of the tool.

Table 3.

Spring AI tool configuration properties.

The tool’s design integrates Spring AI’s native functionalities with seamless connectivity to both Mistral infrastructure and Hugging face inference endpoints, supported by a cache (temporary memory) mechanism. This architecture enables a robust and adaptable foundation for text matching, allowing effortless model interchangeability through simple modification of endpoints URLs.

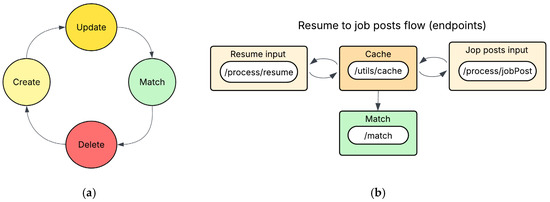

It incorporates functionality for generating xlsx files that present matched pair results ranked in descending order according to the Gemma embeddings model. This ranking is also returned as the tool’s response in json schema. Also, it integrates a cache utility to manage core data operations—creation, update, match, deletion—thereby enabling iterative and efficient text-matching processes within a continuous lifecycle as shown in Figure 2a. Figure 2b presents the matching flow for a resume to job posts.

Figure 2.

(a) Lifecycle of data in cache (temp memory). (b) Endpoint flow for matching operation.

The tool employs a structured cache-driven workflow in which the create operation initializes cache entries (Figure 1—Step 5, 8), the update operation populates these entries with additional data of the same type, and the match operation executes targeted comparisons between stored resume–job posts or job post–resumes. Following result presentation, the cache is cleared, enabling initiation of a new text-matching cycle (Figure 1, Step 11). The complete operations of the tool are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Implemented endpoints of the tool.

The tool is designed as a dynamic, configurable system intended for broad applicability, enabling both individual users and HR professionals to streamline processes and reduce time and effort in managing text-matching in recruitment-related tasks.

Section disclosure: this study did not use generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

5. Results

Our experimental findings demonstrate that combining structured prompts with chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning enables effective zero-shot matching without the need for model training or fine-tuning, relying solely on the natural language processing capabilities of Mistral. The implemented system achieved up to 87% matching accuracy for certain occupations, indicating robust performance across diverse resume–job post domains. We further evaluated Gemma 300M and Nomic v1.5 for embedding generation and observed that Gemma produced superior semantic representations, resulting in consistently higher benchmark scores.

Moreover, a stable pattern was identified in the relative ranking of models, suggesting consistent semantic differentiation across tasks. For the matching process, each resume–job post pair was segmented into topic-based components, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

The segments produced by Mistral for resumes and job posts.

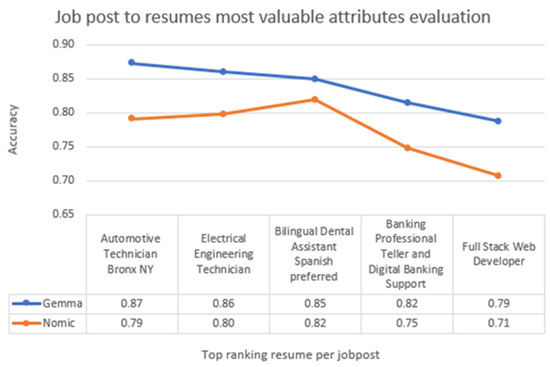

Following the generation of embeddings by Gemma and Nomic, each job post segment was systematically matched to the corresponding resume segment. Cosine similarity was employed to quantify the semantic proximity between segments, producing an individual similarity score for each pair. Once all resumes were processed, an aggregate matching score was computed for each job post–resume pair and ranked in descending order based on Gemma’s overall scores. The same procedure was applied inversely for resume-to-job posts matching. The results are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Job post-to-resumes match most valuable attribute evaluation.

Each job post was ranked according to its highest-matching resume, with, for example, the Automotive Technician position achieving a top match of 0.87 similarity. This ranking procedure was consistently applied across all job posts. For the evaluation at experiment in Figure 3, the most influential attributes (segments) contributing to accurate job post–resume matching was identified as title, responsibilities, experience, and skills. In contrast, the description and education segments demonstrated lower relevance, as job descriptions tend to be generic and educational details—such as university names—often lack direct correspondence with specific job requirements.

The additional information attribute was excluded from average matching score for all experiments due to the contextual divergence between job post and resume content. Nonetheless, it was preserved as an attribute to maintain the user’s input data integrity and to facilitate potential qualitative analyses by HR professionals or individual users.

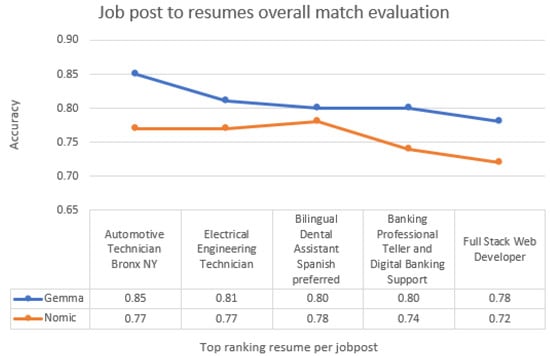

For completeness, an additional experiment was conducted in which the description and education attributes were included in the best-match calculation and ranking process. The results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Job post-to-resumes match with description–education attributes included to evaluation.

The inclusion of the description and education attributes slightly reduced overall matching performance, although the top-ranked job post–resume pairs remained unchanged. This decline is expected, as job post descriptions often focus, e.g., on company-specific information, whereas resumes emphasize individual responsibilities and traits. Similarly, the education attribute can be difficult to match semantically, since job posts may specify a particular degree while candidates may possess additional or differing qualifications. Effective semantic matching of these attributes likely requires specialized approaches.

Across both use cases (Figure 3 and Figure 4), job post-to-resume matching accuracy ranged from 0.87 to 0.79 (Gemma) and 0.79 to 0.71 (Nomic) in the first case, and 0.85 to 0.78 (Gemma) and 0.77 to 0.72 (Nomic) in the second, reflecting good performance across different occupation–resume pairs.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 also reveal a performance pattern between the embedding models: Gemma demonstrates greater sensitivity and captures semantic representations in finer detail, whereas Nomic produces more consistent and stable results.

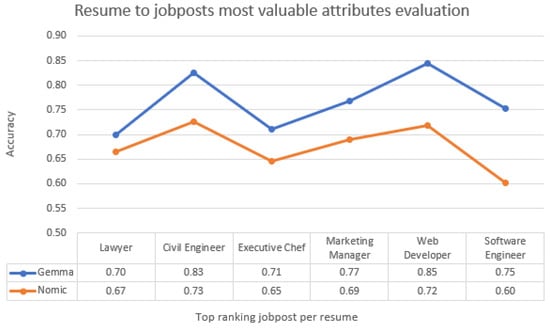

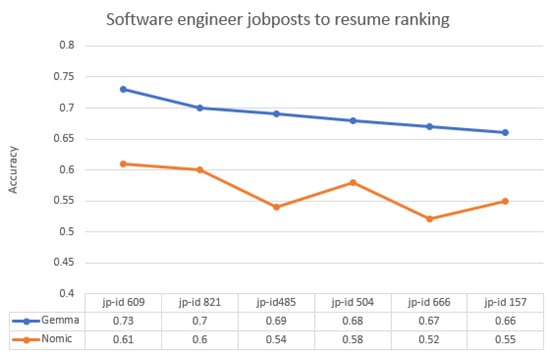

The same methodology was applied to resume-to-job post matching across different resume–occupation pairs, with each resume segment aligned to the corresponding job post segment. For the use case of most valuable attribute evaluation, the results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Resume-to-job posts match most valuable attribute evaluation.

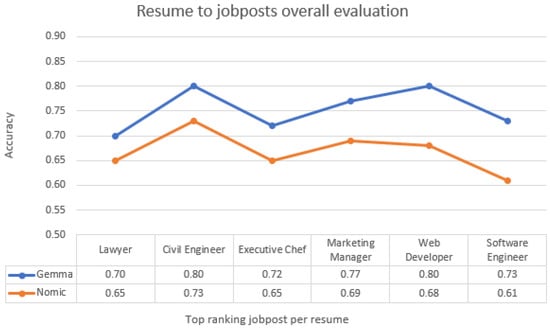

For the use case of the inclusion of description and education attributes, the results are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Resume-to-job posts match with description–education attributes included to evaluation.

Across both use cases (Figure 5 and Figure 6), the accuracy of resume-to-job post matching ranged from 0.85 to 0.70 for Gemma and 0.73 to 0.60 for Nomic in the first case, and from 0.80 to 0.70 for Gemma and 0.73 to 0.61 for Nomic in the second. These results indicate robust performance across diverse occupation–resume pairs. As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, both embedding models exhibit consistent and stable behavior; however, Gemma demonstrates greater sensitivity and a finer capacity for capturing detailed semantic representations.

The matching methodology for job post to resumes and vice versa relies on cosine similarity, a symmetric measure in which reversing the order of the compared vectors (or sentences, in NLP applications) does not affect the similarity value.

At the segment-level, domain-consistent matching—such as comparing education or skills sections of resumes and job postings in either direction—cosine similarity reflects shared domain-relevant information. Our empirical tests [27] demonstrate that missing or unshared content in any segment reduces similarity. In addition, syntactic or phrasing differences between semantically equivalent segments can introduce further, though typically smaller, reductions in cosine similarity, as embedding models are not fully invariant to linguistic variation. Consequently, reductions in cosine similarity in segment-level resume-to-job posts or job post-to-resume matching reflect both missing domain-relevant information and minor variation due to syntactic or phrasing differences.

The literature [28,29,30] commonly reports empirically supported similarity ranges that are widely accepted in semantic analysis; the corresponding threshold values are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cosine similarity scale.

Using the defined similarity scale, Table 7 summarizes the outcomes of both matching operations (job posts to resumes and vice versa) with the Gemma model, which represents the current state of the art for the use cases of the most critical attributes, as discussed above in Figure 3 and Figure 5. The results are presented from job post-to-resumes matching.

Table 7.

Overall success ranking.

The results indicate that only the Chef and Lawyer matches achieved moderate-to-high similarity, suggesting that the corresponding job posts or resumes contained limited and general information, which hindered the capture of nuanced semantic representations. The ranking graphs of the matchings are provided in Appendix A.

The cumulative results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed method for bidirectional matching between job posts and resumes in unstructured and semi-structured text, showing that greater informational content in either document yields higher accuracy and stronger match quality. The tool, its source code, and associated datasets and results are available in the GitHub repository (URLs may be found in the Data Availability Statement section).

6. Discussion

In conclusion, the integration of structured prompts with chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning enables effective zero-shot matching without model training or fine-tuning, leveraging the natural language processing capabilities of Open Mistral 7B. The state-of-the-art embedding model Gemma captured nuanced semantic representations, supporting the system in achieving up to 87% matching accuracy for specific occupations and demonstrating robust performance across diverse resume–job post domains. The proposed tool provides an end-to-end matching pipeline, incorporating mechanisms to mitigate errors associated with LLM use, and facilitates the e-recruitment process for both recruiters and job seekers.

Future iterations of this methodology may enhance the refinement of extracted attributes (segments) for both job posts and resumes. Incorporating named entity recognition (NER) for education, description, and potentially skill attributes is expected to improve overall matching accuracy. Furthermore, expanding the dataset to include multilingual resumes and job posts could broaden the tool’s comprehensiveness and global reach.

Furthermore, integrating other state-of-the-art LLMs alongside Open Mistral 7B, potentially with superior NLP capabilities, offers a promising strategy to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of bidirectional job post–resume matching in e-recruitment processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S.; methodology, P.S.; software, P.S.; validation, P.S. and P.Z.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, P.S.; resources, P.S.; data curation, P.S. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, P.S. and P.Z.; visualization, P.S.; supervision, P.Z. and G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The full data, results, tool’s source code presented in this study are available online: https://github.com/Panagiotis-Skondras/jrmatch (source code—accessed on 6 November 2025); https://github.com/Panagiotis-Skondras/results (results files—accessed on 6 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

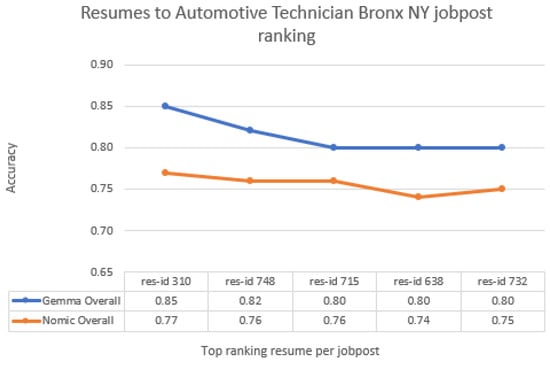

This appendix provides ranking graphs for all job post-to-resume (and vice versa) matching operations. All attributes were included in the calculations, excluding only the additional info attribute as discussed. Figure A1 displays the ranking results for resumes corresponding to the Automotive Technician job post.

Figure A1.

Resumes ranking for Automotive Technician job post.

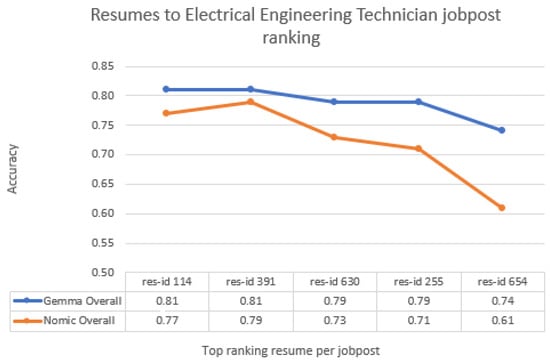

Figure A2 displays the ranking results for resumes corresponding to the Electrical Engineering Technician job post.

Figure A2.

Resumes ranking for Electrical Engineering Technician job post.

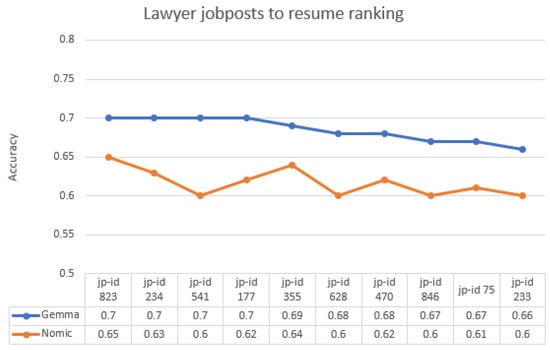

Figure A3 displays the ranking results for resumes corresponding to the Dental Assistant job post.

Figure A3.

Resumes ranking for Dental Assistant job post.

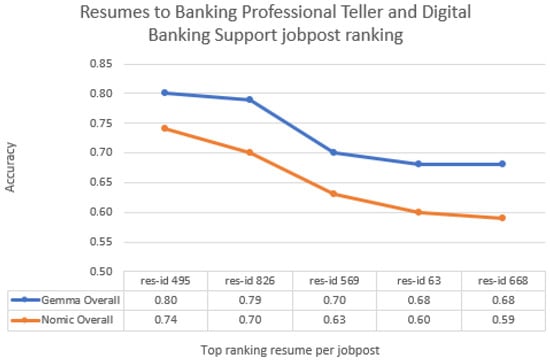

Figure A4 displays the ranking results for resumes corresponding to the Banker/Teller job post.

Figure A4.

Resumes ranking for Banker/Teller job post.

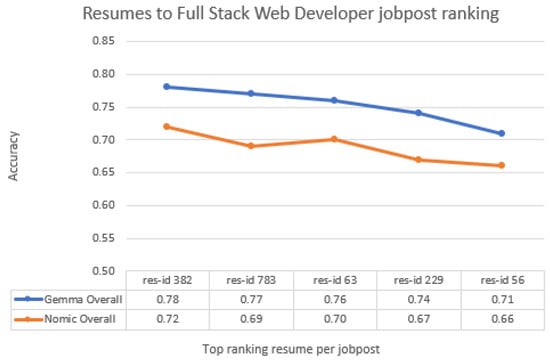

Figure A5 displays the ranking results for resumes corresponding to the Full Stack Web Developer job post.

Figure A5.

Resumes ranking for Full Stack Web Developer job post.

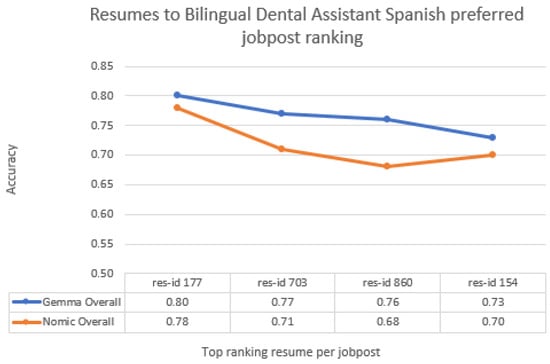

Figure A6 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Lawyer resume.

Figure A6.

Job posts ranking for Lawyer resume.

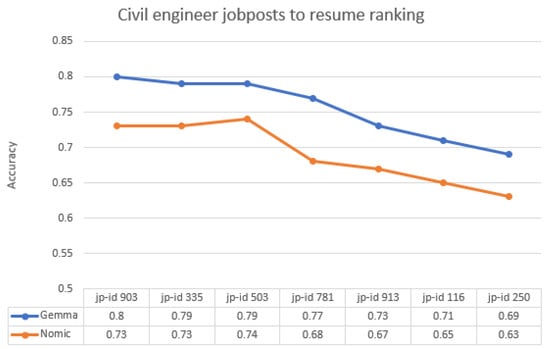

Figure A7 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Civil Engineer resume.

Figure A7.

Job posts ranking for Civil Engineer resume.

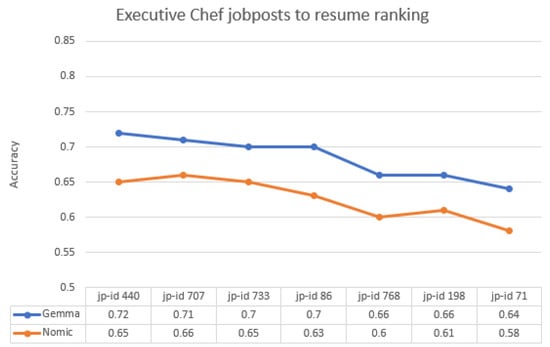

Figure A8 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Executive Chef resume.

Figure A8.

Job posts ranking for Executive Chef resume.

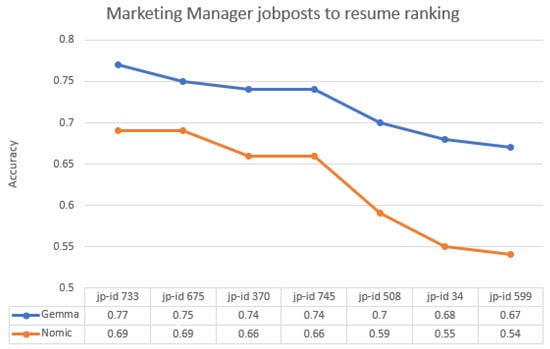

Figure A9 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Marketing Manager resume.

Figure A9.

Job posts ranking for Marketing Manager resume.

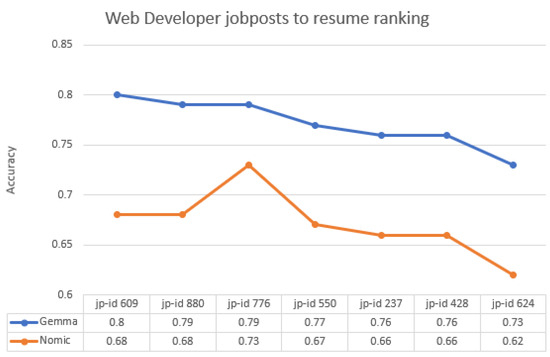

Figure A10 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Web Developer resume.

Figure A10.

Job posts ranking for Web Developer resume.

Figure A11 displays the ranking results for job posts corresponding to the Software Engineer resume.

Figure A11.

Job posts ranking for Software Engineer resume.

References

- Klem, S.; Al Moubayed, N. Prompt Engineering and the Effectiveness of Large Language Models in Enhancing Human Productivity. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.18638. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.18638 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Klem, S.; Al Moubayed, N. LLMs for LLMs: A Structured Prompting Methodology for Long Legal Documents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.02241. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.02241 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11903. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tutunov, R.; Grosnit, A.; Ziomek, J.; Wang, J.; Bou-Ammar, H. Why Can Large Language Models Generate Correct Chain-of-Thoughts? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13571. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.13571 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wang, L.; Xu, W.; Lan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Lan, Y.; Lee, R.K.-W.; Lim, E.-P. Plan-and-Solve Prompting: Improving Zero-Shot Chain-of-Thought Reasoning by Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04091. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.04091 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Chen, Q.; Qin, L.; Liu, J.; Peng, D.; Guan, J.; Wang, P.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, T.; Che, W. Towards Reasoning Era: A Survey of Long Chain-of-Thought for Reasoning Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.09567. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.09567 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06825 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Vera, H.S.; Dua, S.; Zhang, B.; Salz, D.M.; Mullins, R.; Panyam, S.R.; Smoot, S.; Naim, I.; Zou, J.; Chen, F.; et al. EmbeddingGemma: Powerful and Lightweight Text Representations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.20354. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.20354 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Nussbaum, Z.; Morris, J.X.; Duderstadt, B.; Mulyar, A. Nomic Embed: Training a Reproducible Long Context Text Embedder. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01613. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01613 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Shojaee, P.; Mirzadeh, I.; Alizadeh-Vahid, K.; Horton, M.; Bengio, S.; Farajtabar, M. The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06941. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.06941 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Zhao, C.; Tan, Z.; Ma, P.; Li, D.; Jiang, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H. Is Chain-of-Thought Reasoning of LLMs a Mirage? A Data Distribution Lens. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.01191. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.01191 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Turpin, M.; Michael, J.; Perez, E.; Bowman, S. Language Models Don’t Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04388. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.04388 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Duan, J. A Review of Large Language Models: Fundamental Architectures, Key Technological Evolutions, Interdisciplinary Technologies Integration, Optimization and Compression Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. Electronics 2024, 13, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevara, R.V.K.; Mannuru, N.R.; Karedla, S.P.; Lund, B.; Xiao, T.; Pasem, H.; Dronavalli, S.C.; Rupeshkumar, S. Resume2Vec: Transforming Applicant Tracking Systems with Intelligent Resume Embeddings for Precise Candidate Matching. Electronics 2025, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Kharde, A.; Deochake, S.; Kharat, V. Application of RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) in AI-Driven Resume Analysis and Job Matching. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2025, 5, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhobale, P.; Bhoir, V.; Vyavhare, A.; Yelkar, P.; Dharmadhikari, P.A. ResuMatcher: An Intelligent Resume Ranking System. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), Bengaluru, India, 5–7 February 2025; pp. 1778–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Large Language Model-based Resume-Job Intelligent Matching Algorithm and Its Adaptability Case Study Across Different Positions in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Appl. 2025, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagale, G.; Bhat, S.Y.; Dharishini, P.P.P.; GK, P. ProspectCV: LLM-Based Advanced CV-JD Evaluation Platform. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Students Conference on Engineering and Systems (SCES), Prayagraj, India, 21–23 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, F.; Varalakshmi, M.; P U, P.M. Leveraging RAG for Effective Prompt Engineering in Job Portals. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Networking (CICTN), Ghaziabad, India, 6–7 February 2025; pp. 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugale, A.V.; Gayatri, S.; Rutik, G.; Amit, G.; Shreyas, A. Resume Clustering and Job Description Matching. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 2881–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkar, S.A.; Sanjay, S.; P S, V.; M, C. Resume Parser and Job Description Matcher. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computational System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS), Bengaluru, India, 7–9 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, F.P.-W.; Qiu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lo, B. AI Hiring with LLMs: A Context-Aware and Explainable Multi-Agent Framework for Resume Screening. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 4184–4193. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H. Generative Job Recommendations with Large Language Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.02157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skondras, P.; Zervas, P.; Tzimas, G. Generating Synthetic Resume Data with Large Language Models for Enhanced Job Description Classification. Future Internet 2023, 15, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Allal, L.; Lozhkov, A.; Bakouch, E.; Martín Blázquez, G.; Penedo, G.; Tunstall, L.; Marafioti, A.; Kydlíček, H.; Piqueres Lajarín, A.; Srivastav, V.; et al. SmolLM2: When Smol Goes Big—Data-Centric Training of a Small Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.02737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.09388 (accessed on 6 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- The Results Files. Available online: https://github.com/Panagiotis-Skondras/results (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1908.10084 (accessed on 6 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Martes, D.; Gunderson, E.; Neuman, C.; Kachouie, N.N. Transformer Models for Paraphrase Detection: A Comprehensive Semantic Similarity Study. Computers 2025, 14, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bhavsar, N.; Singh, M.; Motlicek, P. An Empirical Comparison of Semantic Similarity Methods for Analyzing down-streaming Automatic Minuting task. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (PACLIC), Virtual, 20–22 October 2022; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2022.paclic-1.63.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).