Abstract

Vehicle trajectory prediction is a pivotal technology in intelligent transportation systems. Existing methods encounter challenges in effectively modeling lane topology and dynamic interaction relationships in complex traffic scenarios, limiting prediction accuracy and reliability. This paper presents Lane Interaction Transformer (LITransformer), a lane-informed trajectory prediction framework that builds on spatio–temporal graph attention networks and Transformer-based global aggregation. Rather than introducing entirely new network primitives, LITransformer focuses on two design aspects: (i) a lane topology encoder that fuses geometric and semantic lane features via direction-sensitive, multi-scale dilated graph convolutions, converting vectorized lane data into rich topology-aware representations; and (ii) an Interaction-Aware Graph Attention mechanism (IAGAT) that explicitly models four types of interactions between vehicles and lane infrastructure (V2V, V2N, N2V, N2N), with gating-based fusion of structured road constraints and dynamic spatio–temporal features. The overall architecture employs a Transformer module to aggregate global scene context and a multi-modal decoding head to generate diverse trajectory hypotheses with confidence estimation. Extensive experiments on the Argoverse dataset show that LITransformer achieves a minADE of 0.76 and a minFDE of 1.20, and significantly outperforms representative baselines such as LaneGCN and HiVT. These results demonstrate that explicitly incorporating lane topology and interaction-aware spatio-temporal modeling can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of vehicle trajectory prediction in complex real-world traffic scenarios.

1. Introduction

Vehicle trajectory prediction constitutes a fundamental element of intelligent transportation systems and autonomous driving technology. This technology utilizes historical motion trajectories and traffic environment information to predict a vehicle’s future position and motion state [1,2]. Accurate trajectory prediction is of great significance for enhancing traffic safety, optimizing path planning, and reducing accident risks. It has been widely applied in autonomous vehicle decision-making, traffic flow management, intelligent navigation, and other fields [3,4]. In the context of escalating urban traffic congestion, the field of vehicle trajectory prediction has emerged as a pivotal area of research in the disciplines of computer vision and intelligent transportation systems.

Existing vehicle trajectory prediction methods can be broadly categorized into two main types: those based on traditional machine learning and those based on deep learning [5,6]. Traditional methods, such as Kalman filtering and constant velocity models, rely on simplified motion assumptions and struggle to handle complex dynamic interaction scenarios [7,8]. Deep learning-based methods have significantly improved prediction accuracy, with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) widely applied in temporal modeling [9,10]. Currently, data-driven methodologies have evolved into a core paradigm for solving complex non-linear problems in engineering systems. Unlike traditional physics-based models that rely on explicit kinematic assumptions, modern data-driven approaches leverage massive datasets to learn latent representations of system dynamics. For instance, Zhao et al. demonstrated the efficacy of integrating visual data with vehicle dynamics for adaptive estimation in complex driving environments [11]. These advancements confirm that utilizing data-driven architectures, particularly those capable of processing spatio-temporal dependencies, is essential for accurate motion forecasting in intelligent transportation systems. In recent years, graph neural networks (GNNs) have garnered attention due to their advantages in modeling vehicle-to-vehicle interaction relationships, while the Transformer architecture has been introduced into trajectory prediction tasks due to its strong long-sequence modeling capabilities [12].

However, existing methods still have significant limitations in complex traffic scenarios. First, most methods adopt a separate modeling strategy, treating temporal and spatial features independently, thereby ignoring the spatio-temporal coupling characteristics of vehicle motion. Second, the utilization of road topology structures is insufficient, failing to effectively integrate lane geometric information and semantic constraints. For example, while LaneGCN [13] considers lane information, it still has limitations in modeling dynamic interactions. VectorNet [14] focuses on vectorized representations but lacks precise characterization of complex interaction patterns. Spatio-temporal point process methods such as DeepSTPP [15] can model spatio-temporal distributions but are constrained by specific parameterization assumptions and structural constraints. Vehicle trajectory prediction faces the following two fundamental challenges:

- Complex spatio-temporal coupling: The behavior of vehicles is influenced by both temporal and spatial factors, and interaction patterns vary significantly across different time points. For instance, Gao et al. [16] demonstrated that integrating spatial and temporal features with graph attention networks can improve vehicle trajectory prediction in urban traffic scenes. However, their design still relies on a relatively fixed way of combining spatial relationships and temporal evolution, which makes it difficult to fully capture highly dynamic and fine-grained spatio-temporal coupling patterns in dense traffic. Existing independent modeling methods face challenges in effectively capturing the spatio-temporal coupling, resulting in inconsistent prediction outcomes.

- Effective fusion of multi-level interaction information: Real-world traffic scenarios involve various interaction modes, such as vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-lane interactions, and the importance of these interactions dynamically changes across different scenarios. For instance, Xie et al. [17] demonstrated that modeling traffic agents on a spatial–temporal topology graph can effectively exploit multi-agent interaction information for trajectory prediction. Nevertheless, their fusion of different interaction levels is largely determined by the predefined graph structure, which makes it difficult to flexibly adapt to diverse and rapidly changing interaction patterns in heterogeneous traffic. How to adaptively model and fuse these multi-level interaction patterns while avoiding the structural parameter assumptions of traditional methods remains an open problem.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we develop a lane-informed vehicle trajectory prediction framework, called LITransformer (Lane Interaction Transformer). LITransformer builds upon established components such as spatio–temporal graph attention networks and Transformer-based sequence modeling, and focuses on integrating lane topology information with multi-level interaction reasoning in a unified architecture. Concretely, a spatio–temporal graph attention network (ST-GAN) is employed as a trajectory encoder to jointly model spatial interactions and temporal dynamics, leveraging graph convolutional networks (GCNs) for global structural awareness, graph attention networks (GATs) for local interaction refinement, and temporal convolutional layers for efficient temporal modeling.

On top of this trajectory encoder, we introduce a dedicated lane topology information extraction module and an interaction-aware graph attention mechanism (IAGAT), which together enable end-to-end fusion of road structure constraints and dynamic vehicle–lane interactions within the LITransformer framework.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Lane-informed spatio-temporal architecture: We design an encoder–decoder framework that integrates a spatio-temporal graph attention network (ST-GAN) with lane topology perception for vehicle trajectory prediction. ST-GAN uses GCNs for global traffic situation awareness and GATs for local dynamic interaction refinement, while temporal convolutions capture temporal dependencies.

- Lane topology encoding and IAGAT-based fusion: We design a lane topology encoder that integrates geometric and semantic lane attributes through direction-sensitive, multi-scale dilated graph convolutions, transforming vectorized lane centerlines into rich topology-aware representations. On this basis, we introduce an interaction-aware graph attention mechanism (IAGAT) that explicitly models four types of interactions between vehicles and lanes (V2V, V2N, N2V, N2N) and employs gating mechanisms to adaptively fuse structured road information with dynamic spatio-temporal features. These modules are specifically tailored to support the lane-informed interaction fusion in LITransformer.

- Experimental validation and analysis: Experiments on the Argoverse motion forecasting dataset show that LITransformer outperforms representative baselines in prediction accuracy. Ablation studies further verify the effectiveness of the main components and the practicality of the overall model in complex traffic scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews and analyzes the related work on vehicle trajectory prediction. Section 3 describes the LiTransformer model architecture and methodology. Section 4 presents the experiment results and analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Works

The primary objective of vehicle trajectory prediction is to formulate a model of future movement paths based on an analysis of historical movement trajectories and environmental information. Depending on the prediction paradigm, existing methods can be broadly divided into two categories: classification-based control models and deep learning-based perception models.

Classification-based control models focus on identifying vehicle control behavior by treating it as a classification problem and utilizing specific vehicle characteristics. These models typically consist of two main modules: one for control recognition and another for trajectory prediction tailored to specific control behaviors. Classifiers that have been applied include heuristic methods [18], Bayesian networks [19], hidden Markov models [20], random forest classifiers [21], and Gaussian process models [22]. These classifiers utilize pattern recognition and data analysis techniques based on historical trajectory data to discern the vehicle’s movement behavior patterns and thereby infer the vehicle’s control intent. However, traditional traffic flow prediction models are typically built on simplified scenario assumptions and employ modeling approaches based on fixed rules or traditional machine learning algorithms. When encountering highly dynamic, uncertain, and complex traffic environments with diverse traffic elements, such models may exhibit significant degradation in performance regarding accuracy, generalization capability, and real-time performance. Traditional methods rely on manually defined features, which require adaptation based on different traffic conditions. Additionally, their accuracy significantly decreases with increasing long-term trajectory prediction. This is because long-term predictions require consideration of more uncertainties and dynamic changes, making modeling more challenging. Therefore, traditional methods may fail to provide satisfactory performance for complex traffic environments and long-term trajectory prediction tasks.

In deep learning-based vehicle perception, vehicle trajectory prediction is typically treated as a sequence classification or sequence generation task [23]. Sequence classification maps trajectories to predefined labels, while sequence generation predicts future trajectories based on input data. In studies focusing on modeling temporal dependencies, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [24], Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [25], and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [26,27] have demonstrated high applicability to sequence data. In Choi et al.’s study [28], an LSTM-based trajectory prediction model processes vehicle coordinate data using independent LSTM units to extract contextual information for each grid. The integrated LSTM network then uses this contextual information to calculate the occupancy probability for each grid, thereby predicting future vehicle trajectories. Ma et al. [29] proposed a real-time traffic prediction algorithm based on LSTM. This algorithm learns the motion states of instances and their interactions through instance layers, aiming to accurately capture the dynamic changes in various elements in traffic flow over time. Additionally, Zhu et al. [30] improved the traditional encoder–decoder LSTM structure by introducing deep neural networks into a star topology for trajectory prediction. Traditional methods perform well in extracting environmental interaction features but have limitations in multi-objective prediction and modeling non-Euclidean spatial relationships. Considering the complexity of spatial relationships between vehicles and their non-Euclidean characteristics, graph neural networks (GNNs) emerge as an effective tool for addressing such problems. GNNs are inherently well-suited for modeling vehicle interactions, effectively capturing complex dependency relationships [31]. GNNs can refine structural information in data and convert it into low-dimensional node representations. Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) extend the scope of convolutional operations from traditional CNNs to graph data, enabling nodes to propagate information through their neighbors and aggregate features [32,33], thereby enhancing the effectiveness of feature extraction and representation learning [34]. Li et al. [35] utilized undirected graphs to represent vehicles and their interactions, combining GCNs with spatially relevant graph operations to effectively extract interaction context and identify dynamic vehicle-to-vehicle interactions.

3. LiTransformer Model Architecture and Methodology

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Attention Network

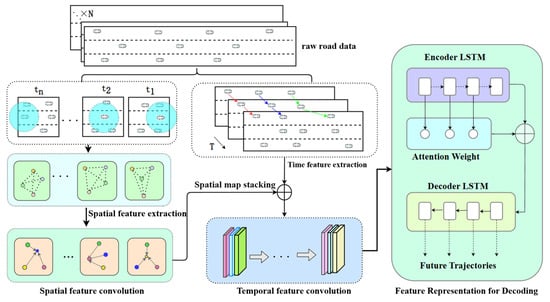

The accuracy of vehicle trajectory prediction highly depends on the precise modeling of spatio-temporal coupled features. Given the intricacy of spatio-temporal modeling for vehicle trajectory prediction and the challenges in effectively capturing both global traffic patterns and local vehicle interactions, this subsection proposes a Spatio-Temporal Graph Attention Network (ST-GAN) (its architecture is detailed in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Architecture of ST-GAN for vehicle interaction modeling.

Employing a hierarchical framework, this network aims to address the limitation of separate spatio-temporal feature modeling in existing methods. Its core design motivation is to synergistically leverage the global structure perception capability of Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) and the local dynamic interaction modeling advantage of Graph Attention Networks (GAT), thereby achieving a comprehensive understanding of traffic scenes from macro trends to micro behaviors. Within the overall LITransformer framework, this ST-GAN functions as the spatio-temporal encoder component.

This module (ST-GAN) functions as a feature extractor, with its output being joint spatio-temporal features. Within the complete LITransformer architecture, this module is labeled “Trajectory Encoder” by function: its output joint spatio-temporal features, together with the lane topology features extracted by the Map Encoder module, will be fed into the IAGAT module for deep fusion of the two feature types.

The network adopts a spatial feature convolution-temporal evolution modeling-trajectory prediction generation architecture, achieving precise vehicle trajectory prediction through multi-level feature fusion. Specifically, in the spatial feature convolution module, global perception and local refinement feature extraction methods are combined. The global graph GCN automatically captures the interaction strength between vehicles at different distances through a distance inverse weighting mechanism, overcoming the limitation of traditional fixed adjacency matrices that cannot dynamically reflect changes in vehicle interaction relationships; The local graph GAT uses learnable attention coefficients to adaptively adjust the interaction weights between adjacent vehicles, further enhancing the modeling capability for micro-behavioral patterns such as emergency lane changes and tailgating risks. In the temporal feature extraction module, a temporal convolutional network (TCN) is used for temporal relationship modeling. Through the expansion, convolution and causal convolution mechanisms of the TCN, short-term behavioral patterns and long-term movement trends are captured, respectively.

(1) Vehicle Space Feature Modeling and Extraction: We use an undirected graph to represent the interaction relationships between vehicles. Assume that there are vehicles in the traffic scene at time . The constructed graph consists of two parts: , where represents the set of vehicle nodes, and each node represents the -th vehicle at time . is the edge set, representing the spatial relationships between vehicles, i.e., their relative positions. The features of each vehicle node may include information such as its position and velocity. To characterize the spatial relationships between vehicles, an adjacency matrix is used to model the connection strengths between vehicles.

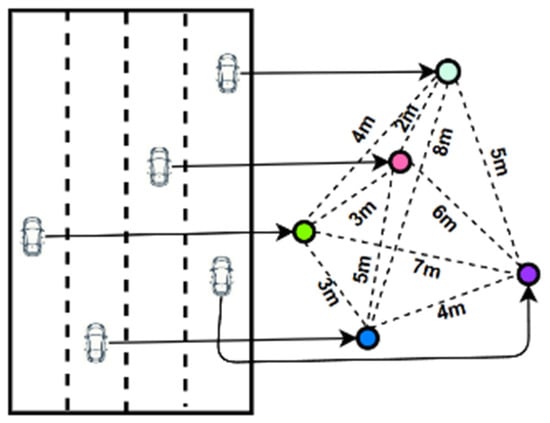

Generally speaking, the influence between vehicles is constrained by distance. For example, the sudden deceleration of one vehicle may cause other vehicles to decelerate or change lanes, but this influence varies with distance. Therefore, in order to distinguish the interaction intensity between two vehicles, this model assigns different weights to each edge in graph and introduces a weighted adjacency matrix , as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Weighted adjacency matrix diagram.

The weights in the weighted adjacency matrix are determined by the distance between vehicles. Specifically, the closer the distance between vehicles, the greater the connection weight. The weights are calculated using the reciprocal of the distance:

In this context, represents the Euclidean distance between vehicle and vehicle at time , where and denote the position coordinates of vehicle and vehicle , respectively, and is a small constant used to prevent division-by-zero errors. Additionally, to ensure that each vehicle node can not only interact with other nodes but also provide self-feedback, the identity matrix is added to the adjacency matrix . Thus, the model can model the self-influence of each node’s historical state and retain the node’s self-information during subsequent graph propagation, resulting in the updated adjacency matrix .

In transportation networks, vehicles located at intersections or specific locations often form strong connections with multiple other vehicles and have high degrees. These highly connected nodes may have an excessive impact on the graph computation process, thereby affecting the stability and accuracy of the model. To address this issue, the model normalizes the adjacency matrix. By adjusting the adjacency weights of each node, normalization balances the influence between nodes and ensures the stability of information transmission in the graph structure. The normalized adjacency matrix is:

where D is the degree matrix, and is symmetrical normalized . Since vehicle positions change dynamically over time, the adjacency matrix needs to be recalculated at each time step based on the latest relative distance . This dynamic update mechanism ensures that the graph convolutional network can adapt to changes in the traffic environment in real time and accurately capture the constantly evolving spatial relationships between vehicles.

(2) Feature extraction based on two-stage spatial attention: After completing the extraction of vehicle spatial features using the above model, including key operations such as graph structure construction, unit matrix addition, and adjacency matrix normalization, the model can effectively represent the spatial relationships between vehicles and ensure that each node retains its own dynamic features while considering the influence of neighboring vehicles. Based on this foundation, global graph convolutional layers (GCN) and local graph attention layers (GAT) are further applied to process spatial features, enabling precise extraction of vehicle spatial features through information propagation and feature learning.

In spatial dimension analysis, a vehicle’s future trajectory is highly correlated with the motion states of its neighboring vehicles. As shown in Figure 3, GCN can directly act on graph vertices, updating node features based on the relationships between nodes and their neighboring nodes. Specifically, each node feature is updated by weighting and fusing its neighboring node features, and the fusion results are then passed to the next network layer for further processing.

Figure 3.

Graph convolution operation.

In GCN, node feature updates can be expressed by the following formula:

where is the node feature matrix of layer , with and are the number of nodes and feature dimensions in the graph, respectively. is the weighted adjacency matrix of the graph. is the weight matrix of layer . is the activation function.

Although GCN can effectively capture the global spatial structure of a graph, vehicle interactions in complex traffic scenarios often exhibit nonlinear characteristics. Especially in densely populated areas, the influence of different vehicles varies significantly. To address this issue, Graph Attention Networks (GAT) dynamically calculate attention weights and adaptively adjust the influence distribution among neighboring nodes, thereby accurately modeling complex spatio-temporal relationships. Therefore, in the model design, the GCN layer is primarily used to capture the global structure of the graph, while GAT further processes local interactions between nodes, assigning each vehicle node an adaptive weight based on the features of its neighboring nodes.

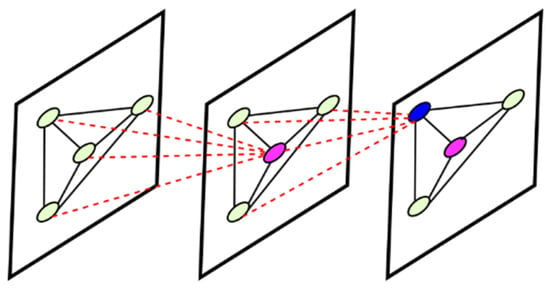

As shown in Figure 4, the multi-layer GCN and GAT structures gradually extract hierarchical features from local to global levels, with the attention weights at each layer capturing more refined and complex interaction relationships. This multi-level learning mechanism enables the model to learn spatial features at different scales simultaneously, enhancing its adaptability to dynamic traffic environments.

Figure 4.

Graph Attention Convolution Block.

The stacked GCN-GAT structure we adopt is a well-considered design. First, the GCN layer serves as the base layer for global structure perception: it efficiently aggregates global neighbor information using a predefined normalized adjacency matrix, enabling effective capture of the global structure and coarse-grained dependencies of the entire traffic scene. Subsequently, the GAT layer acts as the enhancement layer for local interaction refinement: building on the global outline provided by GCN, it dynamically adjusts the interaction weights between nodes and their neighbors via its learnable attention mechanism, further capturing patterns of vehicles’ micro-behaviors (such as emergency lane changes and rear-end collision risks).

Additionally, the attention computation introduced in GAT (e.g., the LeakyReLU activation function) adds nonlinear transformation capabilities to the model. Stacking GCN and GAT introduces more complex function transformations into the model, greatly enhancing the overall expressive power and fitting capability of the model. This “global-first, then local” hierarchical processing allows the model to learn spatial features from coarse to fine, and the nonlinear attention computation of GAT also significantly strengthens the model’s ability to represent complex interaction patterns. While alternative schemes like parallel fusion exist, the current stacked design has been verified to effectively synergize the advantages of the two networks.

(3) Time feature extraction based on time convolution networks: Vehicle trajectory prediction involves both spatial and temporal dependencies. TCNs are employed to extract temporal features, as they model long-term dependencies more efficiently than LSTMs through parallel and dilated convolutions.

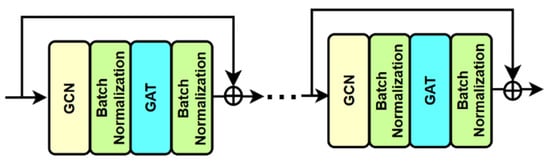

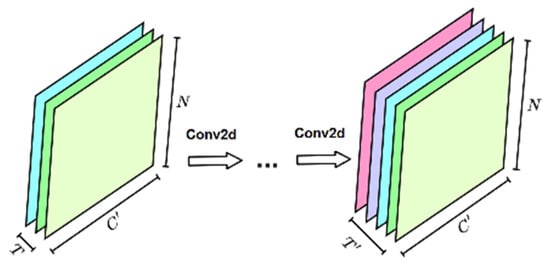

During the spatial feature extraction process, each time step corresponds to a two-dimensional feature map containing all vehicle spatial features. After aggregation through graph convolution operations, a three-dimensional feature map is output, as shown in Figure 5. The core of this module is to use TCN to perform convolution operations on the time dimension to capture time dependencies.

Figure 5.

Temporal feature extractor.

In TCN, the convolution kernel slides along the time dimension. Let the feature at the current time step be , i.e., the cth feature channel, the -th time step, and the -th node. In TCN, the convolution operation uses the features from the past time steps to update the feature at the current time step. The convolution is as follows:

where is the weight of the convolution kernel at time step . is the value of the -th feature and the -th node at time step . After time convolution processing, the final output feature map is still a three-dimensional tensor with the shape:

where is the number of time steps after convolution, typically , while and remain unchanged. This three-dimensional feature map will be used as input for the subsequent model prediction module to predict the future trajectory of the vehicle.

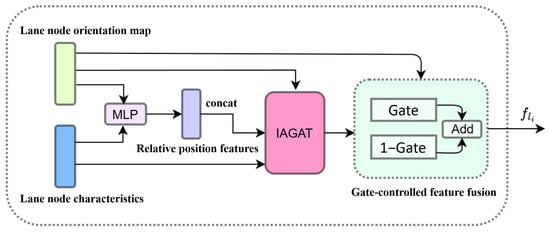

3.2. Lane-Informed Spatio-Temporal Transformer

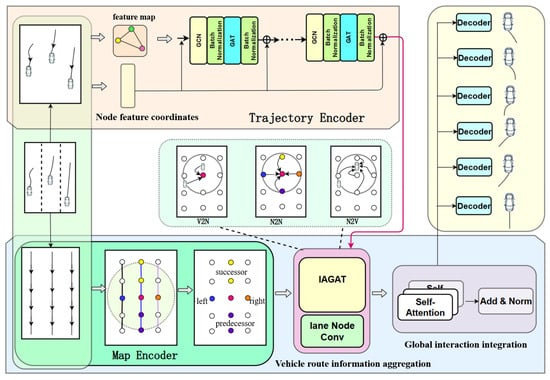

In order to enhance the integration of road information as auxiliary input for vehicle prediction, a lane-informed spatio-temporal Transformer framework is proposed. This framework not only inherits the advantages of Transformer in processing long-sequence data but also introduces multi-scale graph convolutional networks to capture complex relationships between lane nodes. Additionally, we design an Interaction-Aware Graph Attention mechanism (IAGAT) to model the interactions between different vehicles and lanes.

As demonstrated in Figure 6, the LITransformer network architecture comprises three fundamental modules: First, a graph convolution-based lane topology encoding module (referred to as “Map Encoder”) is employed to transform vectorized lane data into topology feature representations. This module integrates geometric and semantic information through multi-scale dilated convolutions and direction-sensitive adjacency matrices. As a result, lane continuity, turning constraints, and long-range dependencies are precisely characterized. Second, a vehicle-road information fusion module with interaction-aware design that employs decoupled attention weight mechanisms to dynamically model four types of interactions between vehicles and lanes (V2N, N2V, V2V, N2N), where V2V represents spatio-temporal feature interaction modeling through spatio-temporal graph convolution. This module employs gating mechanisms to achieve adaptive fusion of local interaction features and global topology information. Third, a Transformer-based global context aggregation and multi-modal decoding module that utilizes multi-head self-attention mechanisms to integrate scene-wide spatio-temporal features and employs parallel decoders to generate multiple candidate trajectories with confidence scores, addressing the uncertainty and diversity of traffic scenarios.

Figure 6.

LITransformer network architecture.

3.2.1. Lane Topology Information Extraction

The extraction of lane information is achieved through the following sequence of steps:

(1) Map Information and Processing: To mitigate potential model instability caused by varying coordinate value ranges, we employ a coordinate transformation method that converts absolute position coordinates to a relative coordinate system. This approach transforms the global coordinates of all traffic participants into a local ego-centric coordinate system centered on the target vehicle.

Let the target vehicle’s position in the global coordinate system be with heading angle . For any traffic participant at position , the transformed coordinates are calculated as follows:

where the rotation matrix is defined as:

This transformation centers the coordinate system at the target vehicle’s position and aligns the coordinate axes with the vehicle’s heading direction , effectively normalizing positional representations and enhancing the model’s capacity to capture relative spatial relationships.

Given the inherent coupling between vehicle dynamics and road structure, we apply the same coordinate transformation to map information to ensure consistent spatial representation. Following the Argoverse dataset’s lane parameterization, each lane centerline consists of a sequence of continuous coordinate points. With the target vehicle positioned at and oriented at , any point on a lane centerline undergoes the same transformation. We discretize the continuous lane centerlines into lane segments, where each segment is represented as:

where and are the start and end points of the lane segment after coordinate transformation, and is the lane attribute feature vector, including semantic information such as turning constraints and lane type.

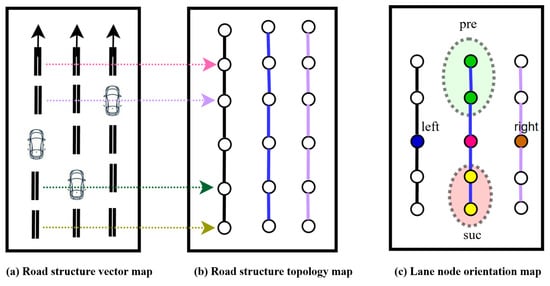

(2) Construction of lane topology node map: Based on the preprocessed map information, we extract and construct lane topology graphs from real-world road data. As illustrated in Figure 7, the original road network is transformed into a vectorized representation where lane centerlines are depicted as dual boundary lines with directional indicators showing prescribed traffic flow directions. To precisely capture local topological relationships, we segment extended lanes into interconnected lane segments.

Figure 7.

Lane vectorization map.

We establish a lane-centric coordinate system around the target vehicle’s current lane segment and classify surrounding segments according to four topological relationships: predecessor (pre), successor (suc), left-adjacent (left), and right-adjacent (right). Predecessor and successor segments represent directly accessible adjacent segments that maintain lane continuity, while left-adjacent and right-adjacent segments denote spatially neighboring segments that comply with traffic regulations. This classification effectively preserves both topological and spatial structural information of the road network.

The resulting lane topology can be formalized as a graph structure , where V represents the node set and denotes the edge set. Each node is defined as follows:

where denotes the total number of lane nodes, and denotes the position coordinates of the -th lane.

To formally encode the connectivity patterns between lane nodes, we construct four distinct adjacency matrices corresponding to predecessor, successor, left-adjacent, and right-adjacent relationships. For instance, the predecessor adjacency matrix captures the connectivity between each lane node and its preceding segments, defined as:

where the values of the matrix elements are either 0 or 1. If , it indicates that node is the predecessor node of node , meaning that a vehicle can travel directly from to . Conversely, if is 0, it indicates that there is no direct connection between the two nodes.

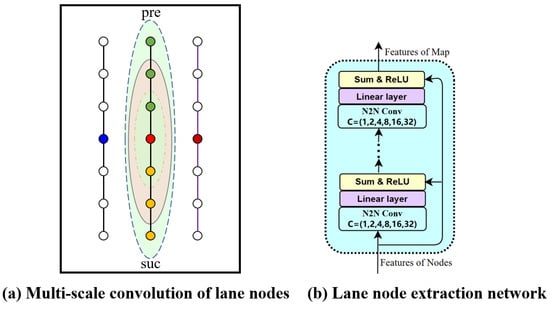

(3) Lane information extraction based on graph convolution: For effective lane topology representation, we encode each lane node using a combination of geometric and spatial features. Specifically, each lane node represents a discretized segment of the lane centerline and is characterized by its geometric properties and spatial configuration.

To address the limitations of conventional lane graph convolution—namely inadequate node representations, lack of directional awareness, and insufficient long-range dependency modeling—we introduce direction-sensitive adjacency matrices coupled with multi-scale convolution mechanisms to enhance topological representation capabilities. Lane node connectivity defines distinct information propagation pathways through four adjacency matrices: , , and , corresponding to predecessor, successor, left-adjacent, and right-adjacent relationships. By leveraging different adjacency matrix combinations, we explicitly differentiate between longitudinal and lateral information flow patterns, effectively encoding geometric connectivity structures.

For long-horizon trajectory prediction in highway scenarios, we employ sparse matrix operations to aggregate multi-hop neighborhood information along lane directions, expanding the receptive field to capture long-range dependencies while preserving computational efficiency. Lateral adjacency relationships (left-adjacent and right-adjacent) utilize single-scale convolution due to their inherently local interaction properties. The formulation is given by:

where remains unchanged in size with , is the expansion scale, and and represent the power of the adjacency matrix. As shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Multi-scale lane information aggregation and node feature extraction module.

3.2.2. Interactive Graph Attention for Vehicle-Road Fusion

To establish comprehensive vehicle-infrastructure feature representations with interactive perception capabilities, we propose the Interaction-Aware Graph Attention Network (IAGAT). The IAGAT model builds upon conventional graph convolutional architectures. It introduces a decoupled attention learning framework that dynamically allocates interaction intensity weights among vehicle nodes. This enables explicit modeling of heterogeneous interaction patterns in traffic scenarios.

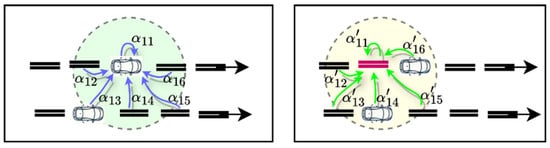

The core principle of IAGAT centers on leveraging attention mechanisms to compute attention weights that quantify each neighbor node’s influence on the central node, as illustrated in Figure 9. Specifically, given node feature for the -th node and neighbor feature , we encode the relative positional information between nodes as , where and denote the spatial coordinates of nodes and , respectively.

Figure 9.

IAGAT Vehicle Road Information Fusion.

IAGAT first calculates the attention coefficient by concatenating the central node features, relative position information, and neighbor node features.

where is the learnable attention parameter vector, and represents the concatenation operation of attention. The attention coefficients are normalized by the function to obtain the weights :

This weight reflects the relative importance of neighbor node to central node . Finally, the updated feature of the central node is obtained by weighted aggregation of neighbor node information.

To comprehensively model complex vehicle–lane interactions, we design four interaction modules that capture different information flow patterns:

Vehicle-to-Node (V2N): This module leverages IAGAT to transmit real-time traffic conditions (e.g., congestion levels, occupancy rates) from vehicles to lane nodes, enabling dynamic map updates based on current traffic states.

Node-to-Vehicle (N2V): Through IAGAT, this module integrates updated lane features with real-time traffic information into vehicle representations, providing vehicles with enhanced contextual awareness.

Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V): This module employs spatio-temporal graph attention to model inter-vehicle interactions and capture cooperative behaviors in traffic scenarios.

Node-to-Node (N2N): Utilizing the graph convolution-based lane information extraction method, this module propagates traffic information across the lane network to update topological features.

The synergistic operation of these four interaction mechanisms enables IAGAT to capture comprehensive vehicle–lane dynamics effectively. We illustrate the V2N interaction mechanism in detail. For each lane node , we define a spatial proximity threshold to identify the neighboring vehicle set that influences node ’s traffic state. As shown in Figure 10, the V2N aggregation follows the IAGAT framework.

Figure 10.

Aggregation of information from vehicles to lane nodes.

First, we compute attention coefficients , using Equation (14), then normalize these coefficients via Equation (15) to obtain influence weights quantifying each vehicle’s impact on the lane node. Subsequently, we perform a weighted aggregation of vehicle features to update lane node representations . Finally, we employ a gating mechanism to integrate the lane node’s intrinsic features with the aggregated vehicle information:

where is the merged lane node feature, denotes feature concatenation, denotes element-wise multiplication, and is the activation function.

The IAGAT-based V2N module offers several key advantages: adaptive attention weighting, decoupled feature-attention computation, and efficient information propagation. These capabilities enable the module to provide enriched contextual representations for downstream N2N and N2V processing stages. Operationally, the V2N module first employs IAGAT to compute attention weights and aggregate vehicle information, then utilizes a gating mechanism to integrate lane node features with the aggregated vehicle representations. The module outputs enhanced lane node features that encapsulate real-time traffic dynamics, serving as refined inputs for subsequent interaction modules.

The V2V and N2V modules follow analogous architectural principles to V2N, collectively establishing comprehensive vehicle–lane interaction dynamics. This multi-modal interaction framework generates rich feature representations that significantly enhance trajectory prediction capabilities by capturing both spatial relationships and temporal traffic patterns.

3.2.3. Global Interaction Fusion and Decoder Multimodal Trajectory Prediction

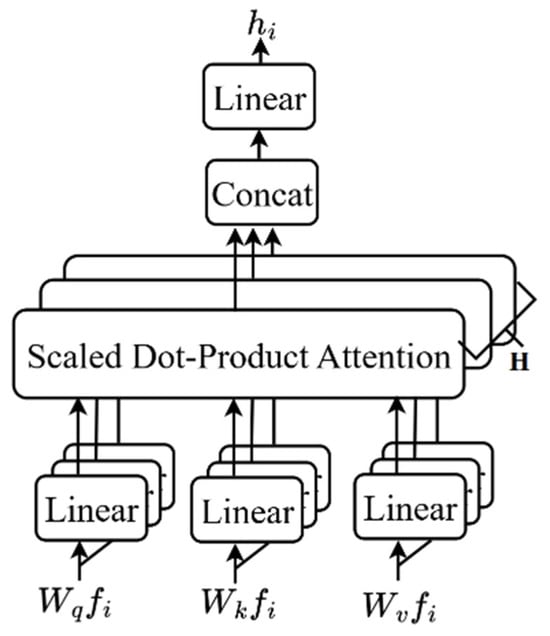

Following the feature encoding stage, we obtain joint feature representations for all vehicles and lane nodes, organized as a feature matrix , where denotes the total number of agents and represents the feature dimensionality. This matrix encapsulates both geometric attributes and multimodal interaction information derived from the four interaction modules. However, since local interaction features may not adequately capture global traffic dynamics, we introduce a global interaction fusion module that aggregates all agent features into a comprehensive scene representation from the ego vehicle’s perspective.

The module employs a self-attention mechanism to model global scene dependencies. Given agents in the scene, each with a feature vector , the self-attention mechanism generates query, key, and value representations through linear projections: , , and , where , are learnable transformation matrices. The attention weights are subsequently computed via scaled dot-product attention and normalized using the function.

To enhance representational capabilities, a multi-head self-attention mechanism is introduced, utilizing independent attention heads. The global feature is ultimately obtained through concatenation and projection, with the computational process illustrated in Figure 11. This design enables the model to capture diverse interaction patterns across different feature subspaces.

Figure 11.

Multi-head attention feature fusion.

In terms of decoder design, considering the multimodal nature of trajectory prediction, the goal is to generate future trajectories, where is a tunable parameter. To this end, the trajectory prediction module employs six identical multi-layer perceptron (MLP) decoders, each generating an independent trajectory. The -th predicted trajectory for the agent is represented as:

where is the -th decoder, is its weight matrix, and is the global feature vector. Each decoder maps to a 2-dimensional vector through a fully connected layer, representing the two-dimensional coordinates of the next time steps. During the training phase, the parameters of these decoders are subject to variation, a process that is intended to ensure trajectory diversity.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

We conduct experiments using the Argoverse Motion Forecasting Dataset, an open-source benchmark developed by Argo AI that has become a standard evaluation platform for autonomous driving trajectory prediction. The dataset integrates high-definition (HD) maps with multimodal sensor data to facilitate vehicle motion forecasting in complex urban environments.

Dataset Characteristics: Argoverse encompasses diverse driving scenarios collected from metropolitan areas, including Miami and Pittsburgh, capturing naturalistic driving behaviors across varying traffic densities, temporal conditions, and weather patterns. This comprehensive data collection provides a robust evaluation framework for multi-agent trajectory prediction algorithms, enabling thorough assessment of model performance under realistic driving conditions.

Dataset Architecture: The motion prediction subset comprises 324,000 complex interaction scenarios extracted through rigorous filtering criteria from the raw data corpus. Each scenario captures 5 s of continuous vehicle dynamics at 0.1 s temporal resolution, providing high-fidelity motion trajectories for analysis.

Scenario Composition: The dataset strategically emphasizes challenging scenarios with inherent behavioral ambiguity, including multi-agent interactions at intersections, lane-change conflicts, and turning maneuvers with path overlaps. These safety-critical scenarios constitute 86.7% of the dataset, ensuring robust model training on edge cases that are crucial for real-world deployment.

Data Split Configuration: The dataset follows a standard three-way partition: the training set contains 208,272 samples, the validation set includes 40,127 samples, and the test set comprises 79,391 samples. Both training and validation sets provide complete 5 s trajectory sequences, while the test set reveals only the initial 2 s observations to establish a standardized prediction evaluation protocol.

Each scenario instance contains multi-layered semantic information: vehicle kinematic states (X/Y coordinates), timestamps, trajectory IDs (TRACK_ID), agent types (OBJECT_TYPE), and city names (CITY_NAME), as shown in Table 1. Argoverse scenarios capture dense multi-agent interactions, providing complex social driving patterns for trajectory prediction model training.

Table 1.

Main fields of the Argoverse dataset.

Training parameters include: 64 epochs, batch size 128, Adam optimizer, learning rate warm-up (0.0005→0.005 over first 10 epochs, then 80% decay every 10 epochs), feature dimension d = 128, and K = 6 trajectory modes.

In our experiments, three common metrics: Average Displacement Error (ADE), Final Displacement Error (FDE), and Miss Rate (MR) are used to evaluate the models, and are defined as follows:

where is the sample size, and is the number of time steps within the prediction time range. and represent the model prediction trajectory and the actual vehicle trajectory, respectively. The Miss Rate (MR) metric evaluates the failure rate of multimodal trajectory prediction by measuring the proportion of scenarios where none of the predicted trajectory modes adequately approximates the ground truth.

4.2. Comparative Experimental Analysis

The baseline models include: LaneGCN, a lane graph-based motion prediction model that constructs sparse lane connectivity and employs extended graph convolution to capture topological relationships and long-range dependencies for actor–lane interaction and multimodal trajectory prediction; CRAT-Pred [36], which models social vehicle interactions through non-rasterized approaches using crystal graph convolution and multi-head self-attention mechanisms; mmTransformer [37], a stacked Transformer architecture for multimodal motion prediction that employs fixed independent feature-level modeling combined with region-based training strategies for precise interaction-aware prediction; and HiVT [38], a hierarchical vector Transformer that decomposes multi-agent motion prediction into local context modeling and global dependency capture phases through vectorized representations and hierarchical interaction mechanisms.

To explicitly clarify the methodological advancements of our proposed approach compared to existing mainstream frameworks, we present a structural comparison in Table 2.

Table 2.

Structural comparison between LITransformer and state-of-the-art methods.

As shown in Table 2, unlike LaneGCN, which utilizes static adjacency matrices, LITransformer introduces the IAGAT mechanism to dynamically modulate interaction weights based on real-time traffic states. Furthermore, compared to HiVT, our method explicitly decouples geometric lane constraints from social interactions before fusing them via a gated mechanism.

Table 3 demonstrates that LITransformer achieves superior performance on key multimodal prediction metrics (K = 6), with minADE of 0.76 and minFDE of 1.20, significantly outperforming all baseline methods.

Table 3.

Experimental results on a test set of different mainstream methods.

Compared to LaneGCN, LITransformer reduces minADE by 12.6% and minFDE by 11.8%. While LaneGCN effectively leverages lane graph representations, it exhibits limitations in dynamic interaction modeling. Our LITransformer addresses this limitation through the IAGAT mechanism, substantially enhancing multimodal prediction accuracy.

Against HiVT, LITransformer achieves improvements of 2.6% and 4.0% in minADE and minFDE, respectively. Although HiVT employs a hierarchical Transformer architecture that excels in multi-agent prediction, it inadequately incorporates lane topology information.

CRAT-Pred adopts a map-agnostic approach that foregoes map information extraction, resulting in constrained performance in complex scenarios. In contrast, LITransformer significantly enhances prediction accuracy through comprehensive map information fusion, particularly excelling in multimodal scenarios.

Compared to mmTransformer, which relies on stacked Transformer architectures, our LITransformer demonstrates superior trajectory prediction capabilities through its comprehensive integration of lane topology and interaction modeling.

Furthermore, LITransformer achieves a miss rate (MR) of 0.08, substantially lower than the 0.14–0.17 range of competing methods, indicating enhanced prediction reliability.

4.3. Ablation Study

The LITransformer model comprises four key components: the lane node graph information extraction module, the vehicle–lane information interaction module, IAGAT (Interaction-Aware Graph Attention mechanism), and the global interaction fusion module. We conduct ablation studies by systematically adding or removing these components to examine their individual contributions to trajectory prediction performance, evaluated using minADE and minFDE metrics at K = 1 and K = 6.

The results in Table 4 and Table 5 are reported as mean ± standard deviation over 5 independent trials to ensure statistical significance. The following sections provide a detailed analysis of each module’s contribution to the overall model performance.

Table 4.

Ablation study of different modules in the model (K = 1). √ indicates the module is included; × indicates the module is excluded.

Table 5.

Ablation study of different modules in the model (K = 6). √ indicates the module is included; × indicates the module is excluded.

In the ablation study of LITransformer, the baseline configuration using only the lane node graph information extraction module exhibits the poorest performance, achieving minADE/minFDE of 1.78/3.92 at K = 1 and 0.92/1.54 at K = 6. These results demonstrate that relying solely on static vehicle and lane node information is insufficient for capturing dynamic interaction relationships in traffic scenarios, resulting in suboptimal prediction accuracy.

The incorporation of the vehicle–lane information interaction module yields substantial performance improvements: 10.9% and 12.3% improvements in minADE and minFDE, respectively, at K = 6, and 2.8% improvements for both metrics at K = 1. This validates the critical importance of vehicle–lane interaction modeling, including vehicle dependency on lane constraints, lane-imposed vehicle restrictions, and inter-vehicle influences, for enhancing the model’s capability to represent traffic dynamics.

It is worth noting the performance discrepancy between K = 1 and K = 6. The Global Fusion Module yields a marginal improvement of 1.2% for K = 1 (deterministic prediction) but a significant 3.2% gain for K = 6 (multi-modal prediction). This aligns with the physical nature of driving: the “most likely” trajectory (K = 1) is often dominated by local kinematics, while the global context provided by the fusion module is crucial for capturing low-probability but high-risk possibilities covered in the multi-modal output (K = 6).

Further integration of the IAGAT module produces additional gains: 6.1% and 8.1% improvements in minADE and minFDE at K = 6, and 1.7% and 3.4% improvements at K = 1. The IAGAT mechanism enhances complex relationship modeling between vehicles and lanes through its interaction-aware graph attention architecture, demonstrating particularly significant benefits in multimodal prediction scenarios (K = 6).

The global interaction fusion module contributes more modest but meaningful improvements. When added without IAGAT, it achieves 3.7% and 3.0% improvements in minADE and minFDE at K = 6. In the complete configuration with all modules enabled, the global fusion component contributes 1.3% and 3.2% improvements at K = 6, and 1.2% and 0.8% improvements at K = 1. While these gains are relatively smaller, they enhance prediction robustness and accuracy through comprehensive global information integration.

The complete LITransformer model achieves optimal performance across all metrics. Compared to the baseline configuration, the full model demonstrates substantial improvements of 17.4% in minADE and 22.1% in minFDE at K = 6, highlighting the synergistic effects of all components working in concert.

4.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

The computational efficiency of trajectory prediction models is critical for real-time deployment. The complexity of LITransformer is primarily dominated by the IAGAT module and the Transformer decoder.

A standard graph attention mechanism typically scales quadratically O(N2) with the number of nodes N. However, to mitigate this bottleneck in dense traffic, we implement a spatial proximity mask that restricts interactions to the K-nearest neighbors (K ≪ N). Consequently, the complexity of the V2V and V2N modules is reduced to O(N · K), ensuring linear scalability relative to the number of agents.

We evaluated the inference speed on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. For a standard scene containing 50 agents, the average inference latency is approximately. 12 ms per frame. This performance satisfies the real-time requirements (10 Hz) of autonomous driving systems, balancing prediction accuracy with computational cost.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose LITransformer, a novel vehicle trajectory prediction approach that effectively integrates lane topology structures with dynamic interaction modeling to address limitations in complex traffic scenarios. By exploiting spatio-temporal graph attention networks and lane topology perception, the proposed method achieves comprehensive scene understanding through hierarchical feature learning that combines global traffic situation awareness with local dynamic interactions. Moreover, the Interactive Perception Graph Attention Mechanism (IAGAT) is introduced to dynamically model multi-class interaction patterns between vehicles and lane infrastructure, while multi-modal decoders enable diverse trajectory generation with confidence estimation. Extensive experiments on the Argoverse dataset demonstrate that LITransformer attains competitive or superior prediction performance compared with strong baselines while maintaining practical inference efficiency for real-time deployment.

While the present approach demonstrates significant advances in trajectory prediction, it still exhibits limitations in certain extreme driving scenarios, such as rare but safety-critical maneuvers (e.g., emergency braking or abrupt evasive lane changes in highly congested traffic) and situations with unusual or rapidly changing road semantics (e.g., construction zones or temporary lane closures), where the current IAGAT design, which mainly relies on geometric lane topology and local spatial proximity, may struggle to fully capture long-range intent and complex social interactions. Moreover, the dynamic adjacency matrix construction and temporal modeling module are not exhaustively explored: in this work, we do not systematically investigate more advanced sparse neighborhood approximations for interaction graphs, nor do we conduct a dedicated comparison between the adopted TCN-based temporal encoder and alternative recurrent architectures such as LSTMs or GRUs. Future work should therefore focus on enhancing model generalization capabilities for extreme scenarios by incorporating richer semantic and intent cues into IAGAT, designing and evaluating more sophisticated sparse interaction mechanisms, and performing a comprehensive ablation study on temporal encoders (e.g., TCNs vs. LSTMs/GRUs), as well as exploring large-scale pre-training frameworks to achieve universal trajectory representations across diverse urban environments.

Furthermore, the current experimental evaluation is restricted to the Argoverse dataset, which mainly reflects North American urban driving patterns and road layouts. As a result, the cross-dataset and cross-region generalizability of LITransformer to different geographical areas with diverse traffic rules, driving behaviors, and road structures remains to be systematically validated. Future work will include extending our evaluation to additional benchmarks such as nuScenes and Waymo Open Motion, and exploring domain adaptation strategies to improve robustness under diverse regional conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.G. (Zhiming Gui) and Z.G. (Zhenji Gao); Formal analysis, Z.G. (Zhiming Gui) and Y.Z.; Investigation, Z.G. (Zhiming Gui) and Y.Z.; Methodology, Z.G. (Zhiming Gui) and Y.Z.; Resources, Z.G. (Zhenji Gao); Software, Y.Z.; Supervision, Z.G. (Zhenji Gao); Validation, Y.Z.; Visualization, Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Z.G. (Zhiming Gui), X.W. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project titled “Mineral Resources Prospecting Prediction System Construction Based on Big Data and Artificial Intelligence” (Grant No. DD20240206202).

Data Availability Statement

The Argoverse dataset used in this study is openly available for download from the official website at https://www.argoverse.org/av1.html (accessed on 5 December 2025). The dataset API and tools are available on GitHub at https://github.com/argoverse/argoverse-api (accessed on 5 December 2025). Detailed download instructions can be found in the Argoverse User Guide at https://argoverse.org (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IAGAT | Interactive Perception Graph Attention Mechanism |

| GCN | Graph Convolution Network |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

References

- Feng, X.; Cen, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Using Intention-Based Conditional Variational Autoencoder. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 3514–3519. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H. A Survey on Trajectory-Prediction Methods for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 7, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Meng, M.Q.-H. A Survey on Deep-Learning Approaches for Vehicle Trajectory Prediction in Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Sanya, China, 27–31 December 2021; pp. 978–985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Gong, S.; Zhao, D.; Liu, F.; Sze, N.N.; Quddus, M.; Huang, H.; Zhao, X. Impacts of Information Quantity and Display Formats on Driving Behaviors in a Connected Vehicle Environment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 203, 107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiao, H.; Yang, Z. Ship Trajectory Prediction Based on Machine Learning and Deep Learning: A Systematic Review and Methods Analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Li, J.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X. A Physics-Informed Transformer Model for Vehicle Trajectory Prediction on Highways. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 154, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fu, J.; Feng, W.; Xu, T.; Yang, K. Surrounding Vehicle Trajectory Prediction under Mixed Traffic Flow Based on Graph Attention Network. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2024, 639, 129643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, X. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Method Based on “Current” Statistical Model and Cubature Kalman Filter. Electronics 2023, 12, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Kang, L.-W.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wang, I.-S.; Hong, C.-H.; Chang, C.-Y. Deep Learning-Based Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Based on Generative Adversarial Network for Autonomous Driving Applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 10763–10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Li, H. LSTM-Based Graph Attention Network for Vehicle Trajectory Prediction. Comput. Netw. 2024, 248, 110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; He, C.; Han, J. Tire-Road Friction Coefficients Adaptive Estimation through Image and Vehicle Dynamics Integration. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliari, F.; Hasan, I.; Cristani, M.; Galasso, F. Transformer Networks for Trajectory Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 10335–10342. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Yang, B.; Hu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liao, R.; Feng, S.; Urtasun, R. Learning Lane Graph Representations for Motion Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 541–556. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H.; Shen, Y.; Anguelov, D.; Li, C.; Schmid, C. VectorNet: Encoding HD Maps and Agent Dynamics from Vectorized Representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11525–11533. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Rossi, R.; Zhao, H.; Yu, R. Neural Point Process for Learning Spatiotemporal Event Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Learning for Dynamics and Control Conference, Stanford, CA, USA, 23–24 June 2022; pp. 777–789. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, K.; Yue, Y.; Wu, Y. A Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Model that Integrates Spatial Interaction and Multiscale Temporal Features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Li, S.; Liu, C. Traffic Agents Trajectory Prediction Based on Spatial–Temporal Interaction Attention. Sensors 2023, 23, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, G.; Shen, N. Research on Obstacle Avoidance Optimization and Path Planning of Autonomous Vehicles Based on Attention Mechanism Combined with Multimodal Information Decision-Making Thoughts of Robots. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1269447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Deng, M.; Lyu, N.; Wang, Y. A Review of Road Safety Evaluation Methods Based on Driving Behavior. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. Engl. Ed. 2023, 10, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akai, N.; Hirayama, T.; Morales, L.Y.; Akagi, Y.; Liu, H.; Murase, H. Driving Behavior Modeling Based on Hidden Markov Models with Driver’s Eye-Gaze Measurement and Ego-Vehicle Localization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Paris, France, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 949–956. [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu, Y.; Schröder, D.; Wodajo, B.T.; Alemayehu, E. Machine Learning for Predictions of Road Traffic Accidents and Spatial Network Analysis for Safe Routing on Accident and Congestion-Prone Road Networks. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, S.A.; Far, B.H.; Fapojuwo, A.O. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction with Gaussian Process Regression in Connected Vehicle Environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, I.P.; Wolf, D.F. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning Techniques for Interaction-Aware Trajectory Prediction in Urban Autonomous Driving. Neurocomputing 2025, 651, 131014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoud, K.; Yahiaoui, I.; Verroust-Blondet, A.; Nashashibi, F. Relational Recurrent Neural Networks for Vehicle Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1813–1818. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Recurrent Neural Networks: LSTM Cells and Network Architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Ren, N.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H. Checkpoint Data-Driven GCN-GRU Vehicle Trajectory and Traffic Flow Prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xing, W.; Jiao, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y. Deep Bi-Directional Information-Empowered Ship Trajectory Prediction for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 181, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, B.; Kang, C.M.; Chung, C.C.; Choi, J.W. Sequence-to-Sequence Prediction of Vehicle Trajectory via LSTM Encoder-Decoder Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 1672–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, W.; Manocha, D. TrafficPredict: Trajectory Prediction for Heterogeneous Traffic-Agents. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 6120–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, D.; Ren, D.; Xia, H. StarNet: Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction Using Deep Neural Network in Star Topology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 4–8 November 2019; pp. 8075–8080. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, E.; Sunwoo, M.; Lee, M. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Using Hierarchical Graph Neural Network for Considering Interaction among Multimodal Maneuvers. Sensors 2021, 21, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, W.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. stat 2018, 1050, 10-48550. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Ying, X.; Chuah, M.C. GRIP: Graph-Based Interaction-Aware Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 3960–3966. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.; Jordan, J.; Gritschneder, F.; Dietmayer, K. CRAT-Pred: Vehicle Trajectory Prediction with Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks and Multi-Head Self-Attention. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 7799–7805. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, B. Multimodal Motion Prediction With Stacked Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7577–7586. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Ye, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, K.; Lu, K. HiVT: Hierarchical Vector Transformer for Multi-Agent Motion Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8823–8833. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).