Abstract

Taking a large single-phase generator transformer product as the research object, this paper applied the finite element simulation method to analyze the vibration characteristics of its core. Firstly, through the analysis of vibration theory, the vibration laws and characteristics of the core are clarified, and a three-dimensional equivalent model of the transformer is constructed. The B-H curve of the silicon steel sheet is measured through experiments and used for the assignment of the core material when calculating the electromagnetic field later. Then, based on the simulation calculation of multi-physical field coupling, the no-load current on the primary side, the distribution and variation characteristics of the magnetic field inside the core are solved and analyzed. On this basis, the sequential coupling method was adopted to solve the displacement distribution of the core vibration and the displacement changes at different position points and conduct a comparative analysis. Subsequently, the accuracy of the simulation calculation method was verified through the test of a small prototype. Finally, based on the comparison of the dry and wet modal simulation results, the impact of transformer oil on the vibration characteristics of the core was evaluated and analyzed. It can be seen from the analysis that the core vibration is generally more intense at the upper part and corners; the impact of the internal oil flow on the vibration of the body of large transformers is relatively complex and thus cannot be ignored.

1. Introduction

As the core equipment of the power system, power transformers inevitably generate vibration and noise problems during operation [1,2]. When the vibration intensifies and the fastening degree of the transformer body is insufficient, it may cause insulation damage between the silicon steel sheets of the core, increasing the loss. At the same time, due to the resonance phenomenon, the core may suffer from loose faults. The noise problem caused by vibration not only seriously pollutes the surrounding ecological environment but also endangers the health of nearby residents [3]. Therefore, the research on the vibration and noise problems of transformers cannot be ignored.

The vibration and noise of the transformer core mainly originate from the magnetostrictive effect caused by the core being in an alternating magnetic field, thus generating vibration and noise. The joints where the core laminations are lapped can also produce vibration and noise due to magnetic leakage [4]. Mauricio et al. conducted finite element simulation calculations on transformer cores with different lamination forms, taking into account the effects of single-stage lamination, multi-stage lamination forms, and lamination distances [5]. Mae et al. adopted the method based on the equivalent magnetization curve. Considering the joint area, they replaced the complex joint structure with an equivalent core structure [6]. Yeong-Hwa Chang et al. conducted research on the lapped joints of amorphous alloy transformer cores and found that the new lapping form was superior to the traditional one in terms of core loss and noise [7]. Reference [8] proposed a three-dimensional finite element analysis method of electromagnetic–mechanical–acoustic coupling for oil-immersed transformers; Reference [9] adopted the finite element method to explore the influence of electromagnetic force on vibration noise, and conducted simulation comparative analysis for two structures: integral core and laminated core, effectively improving the accuracy of the simulation results. Scholars such as Tom Hilgert studied and conducted a comparative analysis of two different magnetostriction models. The results showed that the hysteresis phenomenon included in the magnetostriction model had a significant impact on the calculation results of transformer core [10]. Takahashi et al. measured the magnetic properties of the cores of two types of amorphous alloy distribution transformers and concluded that a new type of amorphous alloy had good magnetization effect and low noise [11]. In 2016, Japanese scholars such as Masato Mizokami studied the vibration and noise characteristics of cores with different lapping methods and found that the core with a trapezoidal lapping structure had lower noise [12]. In 2017, scholars such as French scientists K. Bouayed and L. Mebarek used the finite element method to study the contribution of electromagnetic forces to the vibration and noise of transformers. They also investigated the simulation methods for two types of core structures: the integral core and the laminated core, thereby improving the accuracy of the simulation results [13]. References [14,15] analyzed the vibration characteristics of a three-phase transformer core model using a laser vibrometer. They found that the core column had the maximum vibration and was perpendicular to the core surface. Due to the fastening of the clamping parts, the vibration at the joints was not obvious. Additionally, they found that the harmonic components of the vibration on the side of the core column were relatively large. To analyze the influence of harmonics on the vibration and noise of converter transformers, Yadav S evaluated the influence of harmonics of different orders on the vibration and noise of the core by combining finite element calculation with neural networks [16,17]. Yao D conducted vibration and noise simulations of common core faults through finite element simulation and demonstrated the correlation between vibration signals and noise under fault conditions through experiments [18]. Reference [19], based on the magnetostrictive effect of grain-oriented silicon steel sheets, deeply analyzed the vibration characteristic modes and conducted noise measurement verification on a 110 kV transformer.

This paper takes a single-phase power transformer as the research object and applied the finite element method to conduct multi-field simulation calculations of the transformer. Firstly, through field-circuit coupling simulation, the magnitude of the no-load current on the primary side and the magnetic flux density distribution of the core were obtained. Based on the results of the magnetic field, the magnetostrictive force of the core was solved and imported into the structural field for solution and calculation, thereby obtaining the vibration situation of the transformer core. Then, the simulation method was verified through the experiment of a small prototype. To study the influence of transformer oil on the vibration of the core, this paper conducted simulation calculations and result analysis of the wet mode of the core to evaluate the influence of oil on the vibration of the transformer.

2. Theoretical Analysis of Core Vibration

The vibration sources of power transformers during operation mainly come from the non-linear superposition of the vibration of the transformer body and the cooling device. Among them, the vibration of the transformer body originates from the vibration of the winding and the core. The vibration of the winding is caused by the periodic change of the Lorentz force generated by the interaction between the current flowing through the wire turns and the leakage magnetic field. The vibration of the core is mainly caused by the magnetostrictive effect of the silicon steel sheets. At present, the lamination process of the core can make the silicon steel sheets closely connected. The Maxwell force caused by magnetic leakage between the lamination seams of the core is very small, so it is generally not considered.

2.1. Modal Analysis of the Core

When a power transformer is operating, if the excitation frequency of the core is close to its natural frequency, resonance will occur, leading to an increase in the degree of vibration. For long-term operated iron cores, interlaminar loosening may occur, jeopardizing the normal operation of the transformer. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a modal analysis and evaluation of the core to effectively avoid resonance.

The vibration equation of the core is as follows:

where M is the mass matrix; C is the damping matrix; K is the stiffness matrix.

Based on the above formula, the modal frequency can be derived as:

where k is the stiffness; m is the quality.

It can be seen that the natural frequency of the structure is related to the stiffness and mass of the material, which is closely related to the Young’s modulus and density parameters in the mechanical parameters.

2.2. Vibration Analysis of the Core

The magnetic flux density in the transformer core is expressed as:

where φ is the magnetic flux of the core; Um is the amplitude of the terminal voltage; S is the cross-sectional area of the core column; N is the number of turns on the primary side of the winding; Bm is the maximum value of the magnetic flux density.

The relationship between magnetic flux density and magnetic field intensity is:

where Bs is the saturation magnetic induction intensity; Ht is the coercive force; μ is the magnetic permeability.

The tiny deformation of the transformer silicon-steel laminations caused by magnetostriction under the influence of a magnetic field satisfies the following relationship:

where λ is the magnetostriction ratio of the silicon steel sheet; λs is saturation magnetostriction ratio; ΔL is the maximum amount of expansion and contraction; L is the original size.

The vibration acceleration of the core can be expressed by Equation (6):

Substituting Equations (3)–(5) into Equation (6), the specific relationship of the vibration acceleration of the core can be obtained:

where Us is the phase voltage of the winding.

It can be seen that the vibration acceleration of the core is related to the square of the applied terminal voltage. At the same time, it can be obtained that the fundamental frequency of vibration is twice the frequency of the alternating current, that is, 100 Hz. Generally, the current waveform under no-load conditions is not a standard sine wave. Therefore, in the vibration spectrum, the actual vibration acceleration mainly consists of the 100 Hz component and its harmonic frequency components.

2.3. The Principle of Acoustic–Structure Coupling

For structures in contact with liquids, wet modes are generally required to accurately characterize their dynamic characteristics. Wet modes are solved based on the acoustic–structure coupling algorithm. Therefore, for oil-immersed transformers, the fluid surrounding the transformer body needs to be regarded as an acoustic medium. Then, the normal acceleration of the vibration on the surface of the transformer body is related to the sound pressure radiation. The formula based on the correlation between the two is as follows:

where n is the direction vector; ρ is the air density; qd is the acceleration change of the monopole source in a certain direction; pt is the transient sound pressure; a0 is the surface normal acceleration.

3. Model Calculation and Experimental Comparison and Analysis

In this paper, a 375 MVA single-phase main transformer was taken as the research model. The specific parameters of this transformer are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Important parameters of transformer.

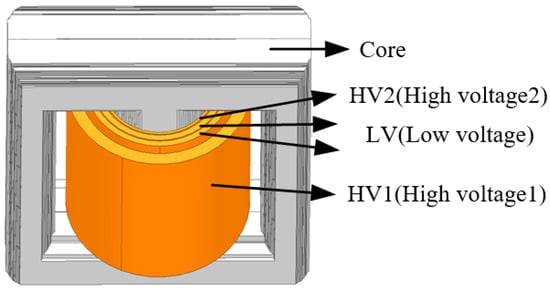

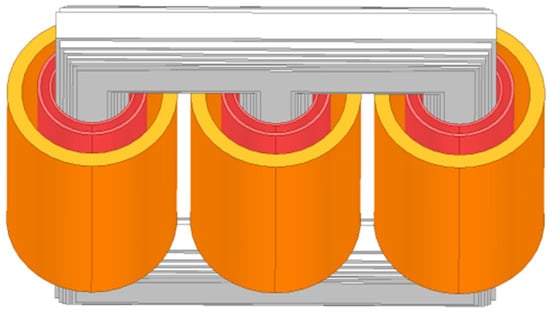

Since the actual transformer is too complex, it is necessary to simplify and equivalent transformer model during modeling, as shown in Figure 1. Under the premise of meeting engineering accuracy requirements, the simplifications were as follows:

Figure 1.

Transformer simulation model.

(1) The silicon steel sheets are very thin and have an insulating coating. It is considered that the core has good insulation performance. Therefore, the influence of eddy currents inside the core was not taken into account.

(2) To simplify the calculation, the core was modeled as a homogeneous and isotropic solid while retaining its external stepped profile.

(3) This paper mainly focused on the research of the core components. Therefore, the windings were simplified into a cylindrical shape. Meanwhile, structural components such as clamping parts were ignored and were equivalent with corresponding constraint conditions.

3.1. Electromagnetic Field Simulation Calculation and Analysis

When the transformer is on no-load, the electromagnetic force generated by the exciting current in the transformer winding and the induced leakage magnetic field is very small. Compared with the vibration of the core, the vibration of the winding can be ignored. The vibration signal under no-load can basically reflect the vibration situation of the core. As this paper mainly focused on the vibration problem of the core, the electromagnetic analysis of the transformer under no-load condition was mainly carried out.

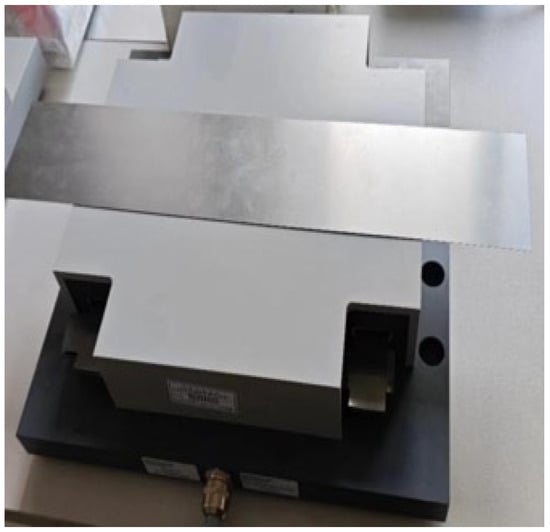

The core is mainly made of silicon steel sheets. During simulation calculations, the B–H curve of B27R085 silicon steel was used as the constitutive relationship. To accurately simulate the behavior of the core in the magnetic field, it is crucial to obtain the magnetic characteristic parameters of the silicon steel sheets. The B–H curve was obtained through experiments with an Epstein square coil, as shown specifically in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Epstein frame.

The main measurement principle is to apply excitation to the primary coil of the test square coil while keeping the secondary coil open-circuited. Then, the exciting current of the primary coil and induced voltage of secondary coil are obtained. The corresponding magnetic field intensity and magnetic flux density are calculated through Ampere’s circuital law and Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction.

where N1 is the number of turns of the primary coil; I is the exciting current; and Leq is the equivalent magnetic circuit.

where U2 is the induced voltage of the secondary coil; N2 is the number of turns on the secondary side; and S is the effective cross-sectional area of the test sample.

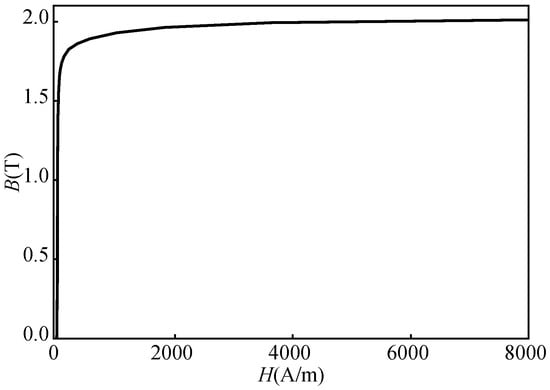

The B–H curve of this silicon steel sheet obtained through experiments is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

B–H curve.

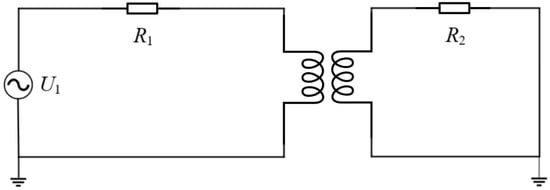

The field-circuit coupling method was employed to determine the electromagnetic parameters of the transformer under no-load conditions. A AC voltage source with a rated voltage of 24 kV was applied to the low-voltage side circuit in the external circuit, while an infinite resistance was added to the high-voltage side circuit to simulate the open-circuit condition. The specific circuit settings are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

No-load circuit diagram.

When transformer is on no-load, the no-load current on the primary side is used to build the magnetic field inside the core. Magnetostriction is precisely the result of the silicon steel sheets under the action of the magnetic field. Therefore, it is necessary to study the electromagnetic characteristics under no-load conditions.

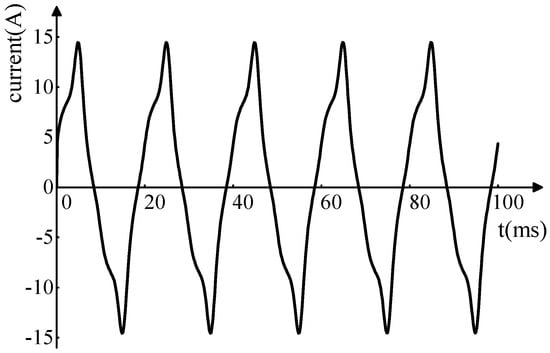

When the core is saturated, the magnetic flux density falls into the non-linear section of the B–H curve. At this time, the no-load current no longer maintains a sinusoidal waveform but turns into a peaked waveform. Besides the 50 Hz component, the current also contains odd harmonic components such as the 3rd, 5th, and 7th harmonics. As shown in Figure 5, through simulation calculations, the no-load current on the low-voltage side of transformer was approximately 15 A, with a no-load current percentage of 0.1%, which is consistent with the analytical calculation results.

Figure 5.

No-load current waveform.

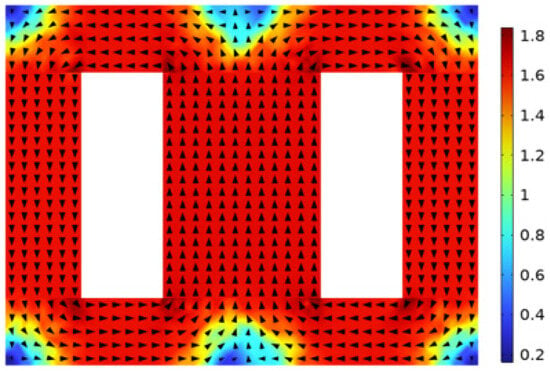

The flux density distribution of the core obtained from the field-circuit coupling calculation of the transformer is shown in Figure 6. The three core legs, from left to right, are the auxiliary limb, the core limb, and the other auxiliary limb. After the magnetic field lines flow out from the central core, they split and flow to the two auxiliary limbs. Then, they converge back to the core limb through the two auxiliary limbs, forming a complete closed magnetic circuit. At this time, the maximum flux density in the core magnetic circuit is mainly concentrated on the core limb and the inner corners of the core window.

Figure 6.

Magnetic flux density cloud map.

The peak value of the working magnetic flux density of the transformer core limb is:

where f is the power frequency of 50 Hz; N is the number of turns of the primary winding; S is the effective cross-sectional area of the core limb, with the unit of m2.

The peak value of the magnetic flux density calculated by Formula (11) is 1.72 T. The average magnetic flux density of the central core obtained from the simulation calculation is about 1.65 T, which is basically within the linear section of the B–H curve, indicating the accuracy of the calculation results of the simulation model.

3.2. Simulation Calculation and Analysis of Core Vibration

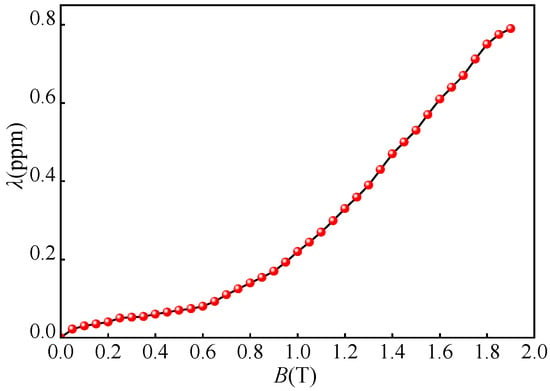

Under no-load conditions, the vibration of the transformer’s core mainly comes from the magnetostrictive effect of the silicon steel sheets. Therefore, this paper conducted a simulation analysis of the vibration under no-load conditions. A sequential coupling calculation method is adopted, that is, the electromagnetic field simulation results are transferred to the structural field. The magneto–mechanical coupling is achieved through the magnetostriction curve. In the structural field, the core is loaded in the form of strain. The magnetostriction curve is shown in Figure 7. At the same time, a fixed constraint is applied to the bottom of the core to simulate the actual state.

Figure 7.

Magnetostrictive coefficient.

The mechanical material parameters of the silicon steel sheets are as follows: the density is 7650 kg/m3, the Poisson’s ratio is 0.3, and the Young’s modulus is 2.01 GPa. The lamination factor of the core is 0.965, and the corrected density of the core is 7382.25 kg/m3. The material parameters are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Transformer structural parameters.

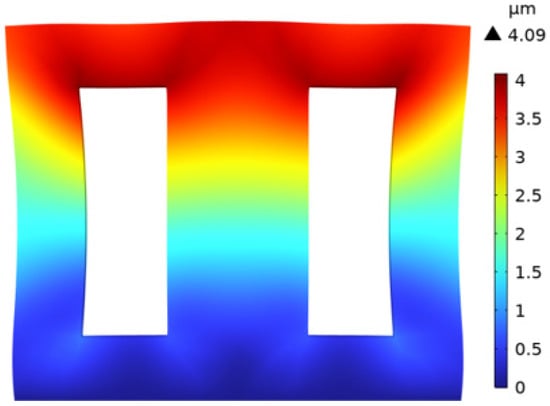

As can be seen from Figure 8, the vibration amplitude of the upper part of the core is relatively large. Due to the application of the fixed constraint boundary condition at the bottom, the vibration amplitude of the bottom of the core is relatively small. The vibration displacement caused by the magnetostrictive effect of the silicon steel sheets is at the micron level. The areas with the largest displacement are distributed at the inner corners and the intersections of the core columns and the upper yokes.

Figure 8.

Core vibration deformation.

Suppose that the X-axis direction is along the width of the core window, the Y-axis direction is along the direction of the core laminations, and the Z-axis direction is along the height of the core window. According to the principle of equal volume of the linear magnetostriction of the silicon steel sheets, when the core elongates along the rolling direction under the magnetostrictive effect, it will contract in the direction perpendicular to the rolling direction. The yoke shows stretching along the X-axis and contraction along the Z-axis, while the core column shows stretching along the Z-axis and compression along the X-axis.

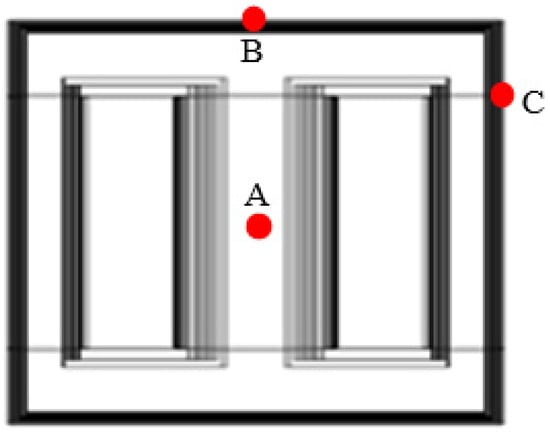

To further analyze the vibration of the core, this paper selected three representative measuring points A, B, and C on the core for research. Point A is located at the center of the outer surface of the core column, point B is located at the center of the upper surface of the upper yoke, and point C is located on the outer surface of the side yoke, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Location of Transformer Measurement Points.

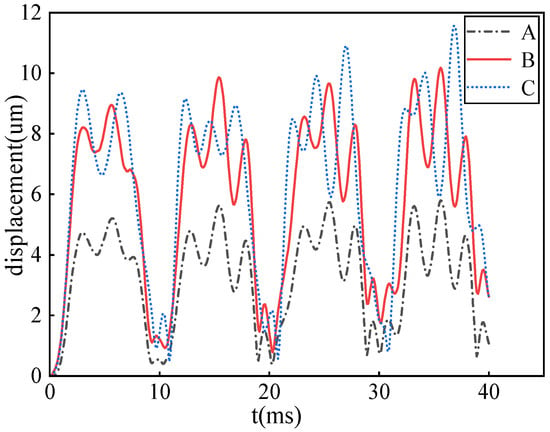

As can be seen from Figure 10, the vibration displacement variation waveform of the core caused by the magnetostrictive effect is obviously periodic, which is consistent with the theoretical formula mentioned above. The vibration of the core varies at different positions. The displacement amplitude of point A is significantly smaller than that of the other two points, and the waveforms at positions A and B basically only differ in magnitude. This is because the magnetic field directions at these two points are the same, resulting in similar magnetostrictive displacement waveforms. However, point A is closer to the fixed position at the bottom, so the vibration amplitude is smaller. Compared with point B, the waveform of point C fluctuates more. This may be because there is local saturation distortion of the magnetic flux density at the corner position, which increases the magnetostrictive effect of the core and further intensifies the vibration at the local position.

Figure 10.

Displacement of the measuring point of core.

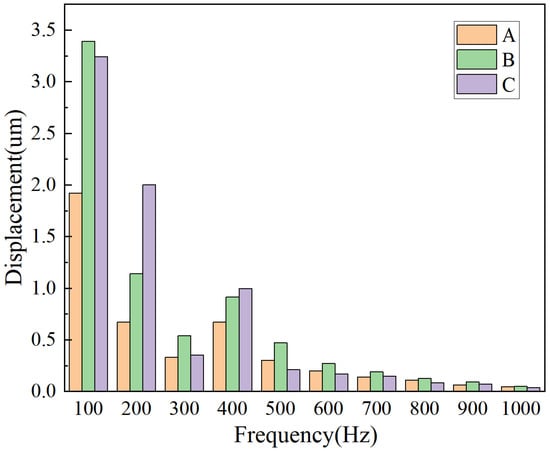

As can be analyzed from Figure 11, the vibration components after FFT decomposition are mainly the 100 Hz component and its harmonic frequency components within the range of 500 Hz. The changes of points A and B in the frequency domain are also basically the same, with only differences in amplitude. Compared with point B, the component of point C at 100 Hz is slightly smaller, while the harmonic components at 200 Hz and 400 Hz are significantly larger than those of point B. This verifies to some extent the statement mentioned above that the magnetic field distortion leads to local intensification of vibration.

Figure 11.

Displacement of the measuring point in the frequency domain.

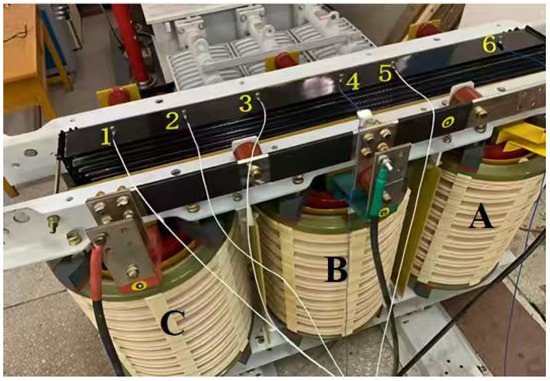

3.3. Prototype Vibration Test

Limited by the current conditions for full-scale machine tests, this paper conducted no-load test measurements on an 800 kVA transformer model prototype in the laboratory to verify the accuracy of the simulation method.

As can be seen from Figure 8, the vibration at the upper end of the core was the most intense, and its vibration characteristics were more prominent than those at other positions. To ensure the quality of the vibration signals obtained from the test, the surface of the upper end of the core was tested. The specific layout of the acceleration sensors is shown in Figure 12 below.

Figure 12.

The test site of no-load test.

The equivalent model is established as shown in Figure 13. The same simulation methodology described above was employed to perform magneto–mechanical coupling analysis on the prototype core.

Figure 13.

Equivalent model of the 800 kVA prototype.

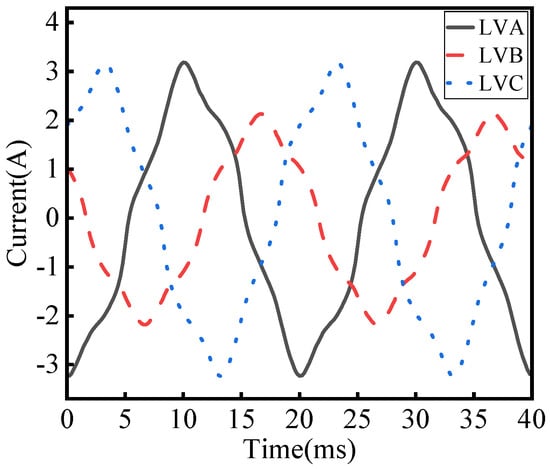

As can be seen from Figure 14, the no-load current of the transformer was not completely symmetrical, which is caused by the asymmetry of the magnetic circuit of the core-type core. Since the magnetic circuit of the middle core column is short, the no-load current of the middle phase is relatively small. The simulation results are consistent with the fundamental principles of magnetic circuit behavior.

Figure 14.

No-load current waveform.

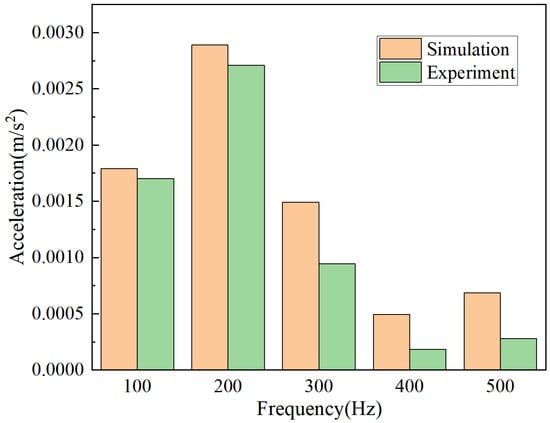

This paper only shows the comparison chart of the simulated values and experimental data at position 1, as shown in Figure 15. The vibration characteristics of both showed good agreement. However, deviations between simulated and experimental results are inevitable due to the direct mechanical coupling between the core and other components in the actual system, which was not accounted for in the simulation model. The simulated values exhibited an overestimation tendency.

Figure 15.

Comparison between simulation and experimental results.

4. The Influence of Transformer Oil on the Vibration of the Core

Modal analysis can effectively predict the excitation response of a structure. According to the analysis of relevant literature, fluid has two aspects of influence on the inherent characteristics of the structure: on the one hand, due to gravity, the fluid itself exerts pressure on the fluid–solid coupling surface; on the other hand, the fluid has a mass addition effect on the structure. In the past, when studying the modal characteristics of transformers, only dry modal simulation analysis was generally carried out. However, for oil-immersed transformers, the core is immersed in transformer oil. At this point, the influence of oil flow can be considered through the wet modal module based on the acoustic–solid coupling algorithm.

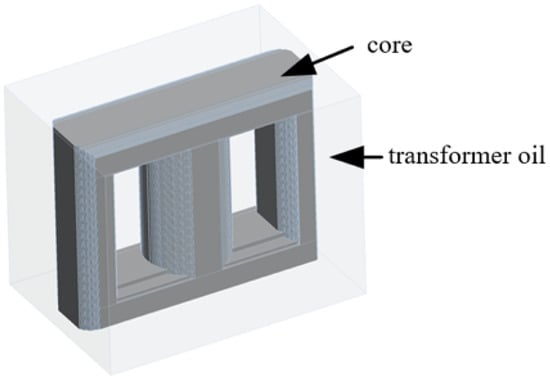

The surrounding oil was configured according to the tank size, as illustrated in Figure 16. The physical parameters of the external oil are as follows: density is 900 kg/m3, sound speed in the oil is 1400 m/s, viscosity is 0.001 Pa·s, and gravitational acceleration was set to 9.81 m/s2. During the simulation, a fixed constraint was applied to the bottom of the core to simulate the fixed state of the bottom. After completing the settings of materials and boundaries, we conducted the simulation calculation. The comparison results of the dry and wet modal simulations of the core are shown in Table 3. Due to the limited length of the article, only the comparison results of the first six orders are presented.

Figure 16.

Wet modal computational model of the iron core.

Table 3.

Comparison of simulation results.

The rate of change in the above table is defined by the following formula:

It can be seen from the analysis of the data in the above table that the results of each order of the wet mode were smaller than those of the dry mode. This is because the mass loading effect of the fluid surrounding the structure hinders the vibration of the structure. As the order of the mode increases, the rate of change between the dry and wet modes generally increases. When the transformer is filled with transformer oil, the natural frequency of the core assembly will decrease to some extent. This may lead to a phenomenon where, although the natural frequency in the dry mode is clearly far from exciting frequency, resonance still occurs. Therefore, for oil-immersed transformers, the influence of transformer oil on the structural vibration should be taken into account. It is more accurate to use the calculation results of the wet mode to evaluate the vibration response of the structure under different forces. At the same time, if the vibration of the core needs to be calculated accurately, the influence of the oil on the vibration of the core should be considered.

5. Conclusions

This paper used finite element simulation software to evaluate and analyze the vibration characteristics of core of a large oil-immersed power transformer, including aspects such as electromagnetics, solid mechanics, and modal analysis. A model prototype was used for simulation verification. The results were analyzed as follows:

(1) The current and magnetic flux density distributions under no-load conditions were calculated through the field-circuit coupling method. It was found that the no-load current is very small, and the waveform is a peaked waveform rather than a sinusoidal waveform due to the magnetic flux density entering the saturation section.

(2) Based on the electromagnetic–structural coupling principle, magnetostrictive phenomenon of the core under no-load conditions was simulated. The simulation results provide an intuitive display of the magnetostrictive deformation. The vibration of the upper part of the core was more intense, especially at the corners. The vibration signal of the core mainly consisted of the 100 Hz component and its harmonic frequency components, and were basically concentrated within the range of the first 500 Hz.

(3) The influence of oil on the vibration of the core assembly is relatively complex. On the one hand, due to the viscous effect of the transformer oil, the vibration of the core needs to overcome the resistance it brings, which reduces the vibration of the core. On the other hand, the mass loading effect of the transformer oil reduces the natural frequency of the core, which will affect the overall vibration characteristics of the transformer and may trigger resonance phenomena, thereby amplifying the vibration.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.L.; Formal analysis, Z.Y.; Resources, Z.T.; Writing—original draft, S.Y.; Project administration, Z.Z., C.L., G.L. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by China Yangtze Power Co., Ltd. under Grant Z152302032. Joint Funds of National Natural Science Foundation of China: U2166213.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhuoyan Zhong, Zhengyang Tang, Chengxiang Liu, Guang Li and Yexing Wang were employed by the company China Yangtze Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Du, Y.; Qiao, C.; Zhao, L.; Niu, Y. Study on Vibration Noise of Power Transformers Based on Multi-physical Field Simulation and Experiment. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Power and Energy Technology (ICPET), Beijing, China, 12–15 July 2024; pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Chen, X.; Dong, J. Study on Vibration and Noise Characteristics of Epoxy Resin Dry-type Transformer Core under No-load Condition. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Forum on Electrical Engineering and Automation (IFEEA), Nanjing, China, 3–5 November 2023; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Lee, S.-L.; Lin, C.-C.; Liu, C.-S.; Chang, S.-Y.; Hsieh, M.-F. Reduction of Vibration and Sound-Level for a Single-Phase Power Transformer with Large Capacity. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8403204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, B.; Pfutzner, H. Relevance of magnetostriction and forces for generation of audible noise of transformer cores. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 3759–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Luz Mauricio, V.F.; Dular, P.; Leite, J.V.; Kuo-Peng, P. Modeling of Transformer Core Joints via a Subproblem FEM and a Homogenization Technique. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mae, A.; Harada, K.; Ishihara, Y.; Todaka, T. A study of characteristic analysis of the three-phase transformer with step-lap wound-core. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2002, 38, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Tseng, C.P. Magnetic Properties Improvement of Amorphous Cores Using Newly Developed Step-Lap Joints. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, W.; Witczak, P. Vibration analysis of small power transformer. COMPEL Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr.-Al Electron. Eng. 2010, 29, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, Z. Numerical analysis and experimental research of vibration and noise characteristics of oil-immersed power transformers. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 106, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi, A. Noise and vibration of a power transformer under an electrical excitation. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 128, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Azuma, D.; Hasegawa, R. Acoustic and Soft Magnetic Properties in Amorphous Alloy-Based Distribution Transformer Cores. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 4001–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masato, M.; Yousuke, K. Variation of noise and magnetostriction associated with Joint types of transformer core. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2016, 194, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bouayed, K.; Mebarek, L.; Lanfranchi, V.; Chazot, J.-D.; Marechal, R.; Hamdi, M.-A. Noise and vibration of a power transformer under an electrical excitation. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 128, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami, M.; Yabumoto, M.; Okazaki, Y. Vibration analysis of a 3-phase model transformer core. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2015, 119, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilyashki, G.; Pfützner, H.; Hamberger, P.; Aigner, M.; Kenov, A.; Matkovic, I. Spatial distributions of magnetostriction, displacements and noise generation of model transformer cores. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2016, 118, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehta, R.K. Investigation on magnetostrictive behaviour of a converter transformer influenced by dominant harmonics: A FEM and ANN based approach. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, e12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehta, R.K. Modelling of magnetostrictive vibration and acoustics in converter transformer. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2021, 15, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D.; Chen, D. The vibroacoustic characteristics analysis of transformer core faults based on multi-physical field coupling. Symmetry 2022, 14, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Study of Transformer Core Vibration and Noise Generation Mechanism Induced by Magnetostriction of Grain-Oriented Silicon Steel Sheet. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 8850780. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).