Abstract

A promising approach to alleviate the emerging capacity limitations in backbone optical networks is to employ the Super C+L-band, which provides an available spectrum of roughly 12 THz. Network throughput is a key metric for analyzing the performance of such networks; however, evaluating this metric is a complex task due to the interplay between physical and network layer aspects. Physical modeling, which accounts for signal impairments, is particularly complex in these scenarios due to the presence of Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS), which transfers energy from the C to the L band. On the other hand, network layer modeling is also challenging due to the influence of numerous factors, including physical topology, routing, and traffic characteristics. For the networks considered here, we propose a machine learning approach to predict both the network throughput and the average channel capacity for the Shannon and real cases, and to investigate how these metrics depend on various physical topology parameters. The approach relies on an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model, whose predictions are interpreted using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method to identify the importance of various topological parameters. Furthermore, the ANN is trained using data obtained from a previously developed simulator that takes into account both physical and network aspects. The analysis provides valuable insights for designing future ultra-high-capacity optical backbone networks.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the unprecedented growth of data traffic has imposed stringent requirements on the backbone infrastructures of network operators, including telecommunication providers and internet companies, where traffic flows between their nodes are expected to reach tens of terabits per second (Tb/s) in the medium-term, and potentially scale to hundreds of Tb/s in the long-term [1]. Such projections pose major challenges for the development of next-generation optical infrastructures, especially at the backbone level.

A well-established technology in modern optical networks is Wavelength Division Multiplexing (WDM). WDM operates by combining multiple optical signals, also referred to as optical channels, onto the same fiber, allowing them to be transmitted simultaneously, with each channel being characterized by its own wavelength. Most currently deployed WDM systems operate in the extended C-band on standard single-mode fibers. This band occupies a bandwidth of about 4.8 THz, which limits the maximum WDM transmission capacity—defined as the product of the number of channels and the bit rate per channel—to well below 100 Tb/s over long distances [2]. To face the enormous increase in bandwidth demand, it is necessary to significantly expand the number of available channels, which can be achieved by relying on Band Division Multiplexing (BDM) techniques [3]. Also known as multiband transmission, BDM theoretically allows the full utilization of the low-loss spectrum of optical fibers, which includes the O, E, S, C, L, and U bands. However, a major barrier to fully exploiting all optical transmission bands is the lack of maturity of enabling technologies, particularly optical amplifiers. As a result, their deployment across the entire spectrum is not yet feasible. The notable exception is the C and L bands, where Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (EDFAs) are commercially available, enabling the practical use of the C+L solution. A particularly attractive option is to rely on the Super C+L-band which, by offering a bandwidth of approximately 12 THz, can increase the transmission capacity by about two and a half times compared with C-band solutions. In fact, in a recent field trial [4], real-time WDM transmission of 96 Tb/s (80 × 1.2 Tb/s) was demonstrated over a 305 km fiber link using a 12 THz optical band, compared with a capacity of 39.6 Tb/s (33 × 1.2 Tb/s) reported for an experiment over 172 km using a fully loaded 4.8 THz-wide C-band [5].

The performance of networks operating in the electrical domains is primarily determined by network-layer metrics such as throughput, latency, blocking probability, robustness, etc. However, in optical networks, signal quality at the physical layer also plays a critical role, as impairments in the optical domain directly affect the performance of upper layers. Therefore, metrics such as the Optical-Signal-to-Noise Ratio (OSNR) must also be accounted for. In this work, the performance analysis is carried out using the network throughput metric, in the presence of both network-layer constraints and physical impairments.

Network throughput is a key performance metric used to characterize and design optical networks, and in the absence of traffic blocking it coincides with the network capacity. This capacity represents the maximum amount of data that the entire network can support per unit of time and can be estimated using Shannon’s information theory [6]. The Shannon capacity assumes Gaussian-distributed input signals and therefore represents an upper bound on the real or achievable capacity. In practice, this capacity is determined by considering the modulation formats deployed in optical networks (e.g., QPSK, M-QAM).

Assessing the capacity of an optical network is a difficult task because it is influenced by both physical-layer effects in the fiber and network-level factors, including the physical topology, traffic matrix, routing strategy, wavelength assignment, and modulation format selection. This challenge becomes even greater in C+L-band systems, where the analysis must consider not only the usual C-band impairments (see [7]) but also the impact of SRS, which causes a power transfer from higher-frequency components (C-band) to lower-frequency ones (L-band) within a WDM signal [7,8].

A central point in the estimation is to understand the relationship between topological network parameters and overall network throughput, as well as identifying the main patterns that characterize this relationship. This subject has received attention in multiple recent works. Reference [9] shows that network throughput depends strongly on the physical topology, but it does not address the impact of individual parameters. In [10], this impact is analyzed by considering both physical and logical aspects, showing that network throughput decreases with the average link distance and depends only weakly on the normalized network diameter, also known as network ellipticity. Although not accounting for signal propagation aspects, the study in [11] goes further by extending the analysis to various spectral and non-spectral parameters using Pearson correlation, showing that parameters such as algebraic connectivity, average number of hops, and network diameter are strongly correlated with network throughput. Furthermore, as a novel contribution, this analysis enables a quantitative comparison of the different parameters.

In network design, identifying the most influential network parameters is often crucial as it can help to optimize network performance. To the best of our knowledge, this problem has only been explicitly addressed in [11]. In this paper, besides considering a larger number of network parameters than in [11], we also propose a different methodology to compare and identify the relevance of these parameters. The approach involves using SHAP in conjunction with a trained ANN as a way to interpret the ANN’s predictions. In addition, we apply this methodology to throughput studies in the context of Super C+L-band optical networks, considering both Shannon and real throughputs.

To create the extensive synthetic datasets required for training and testing the model, we relied on a simulation framework developed by the authors in an earlier work [7]. This tool generates random network topologies that resemble real optical networks and performs routing, band, and wavelength assignment using heuristics specifically developed for this purpose.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses key aspects of network modeling. Section 3 describes, in a simplified way, the approach used to calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and network throughput. Section 4 focuses on the neural network structure and introduces some SHAP-related aspects. Section 5 describes the methodologies used to generate synthetic datasets and discusses the computed numerical results. Finally, Section 6 presents the main conclusions of the study.

2. Network Aspects

2.1. Network Modeling and Topological Parameters

In this paper, we consider transparent optical backbone networks, meaning that the node structures are based on Reconfigurable Optical Add-Drop Multiplexers (ROADMs), which are interconnected through optical links. These links are constituted by bidirectional fiber connections and in-line amplifiers placed at appropriate intervals to offset propagation losses. In C+L-band systems, the in-line amplification stage must include a Demultiplexer (DEMUX) and Multiplexer (MUX) to split and later recombine the two spectral bands, together with two separate EDFAs operating in parallel—one for the C-band and another for the L-band. It is further assumed that each amplifier has a bandwidth of 6 THz (super-band operation), leading to a total transmission bandwidth of 12 THz per optical fiber.

The physical topology of an optical network can be represented as an undirected weighted graph G(V, E), with } representing a set of optical nodes and } representing a set of optical links. In this model, N = |V| corresponds to the number of nodes and L = |E| to the number of links. Each optical link is implemented using a pair of optical fibers as previously mentioned. A link is characterized by two attributes: (i) the physical distance (in kilometers) between nodes and ; (ii) , the link capacity expressed as the number of wavelength channels, denoted by . This number is determined by dividing the total transmission bandwidth by the channel frequency spacing , which in this work is assumed to be equal to the symbol rate , since the physical layer modeling is based on the Nyquist limit assumption [12].

In addition to and , other topological properties of the graph play an important role. These include the node degree , the network diameter , and the algebraic connectivity where defines how many links are incident to a given node, corresponds to the length of the longest shortest path between any pair of nodes, and is the second smallest eigenvalue of the graph’s Laplacian matrix, given as [13]:

where denotes the degree of node . It is worth noting that algebraic connectivity offers important insights about network connectivity and is closely related to the network’s capacity [11].

2.2. Routing, Band, and Wavelength Assignment Modeling and Topological Parameters

Network capacity is influenced by several parameters. These include the physical topology, represented by the graph , and the logical topology, which specifies how traffic is exchanged between node pairs. The logical topology can be characterized by the demand matrix ], an matrix where each element indicates the number of traffic requests between a source node and a destination , with .

For every traffic request , our modeling framework needs to determine a corresponding lightpath within the physical topology, select a transmission band (C- or L-band), and assign an appropriate wavelength. As a result, the classical routing and wavelength-assignment (RWA) task is extended here to also include a band-selection step.

Because several candidate routes may exist between any node pair, we compute the -shortest paths using a heuristic such as Yen’s algorithm. In this context, the shortest path is the one that minimizes the sum of the link lengths along the route, . This strategy provides multiple candidate paths for each traffic demand when the main path is unavailable, thereby reducing the blocking probability.

For what concerns band selection, the C-band is used preferentially, and the L-band is employed only once the C-band is fully occupied, following the optimized strategy reported in [14]. Moreover, to satisfy the continuity and distinct-wavelengths constrains, the same wavelength must be assigned to all the links of a lightpath, while no two lightpaths share the same wavelength on a given link.

Each lightpath corresponds to an optical channel with wavelength and capacity , where . Here, , with representing the set of channels required to implement a logical full mesh topology. To compute the capacity , it is necessary to evaluate the total SNR () of the optical signal transported by the optical channel at its termination.

3. Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Throughput Evaluation

3.1. Signal-to-Noise Ratio Evaluation

In a transparent optical backbone network, an optical channel usually propagates across multiple nodes and fiber links. As referred, each optical link consists of a bidirectional fiber pair for bidirectional transmission, along with optical in-line amplifiers installed at regular intervals. These intervals, known as spans, fully compensate for the signal losses accumulated over each fiber span. For a link of total length comprising identical spans, the length of each span is , and the attenuation per span is , where α represents the fiber attenuation coefficient in dB/km. In addition, each optical channel is characterized by the occupied bandwidth denoted as . The minimum bandwidth required to ensure signal transmission over the channel without inter-symbol interference is defined by the Nyquist criterion and is equal to the symbol rate [11].

Optical amplifiers, in addition to amplifying the signal, also introduce Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) noise, which degrades the quality of the received signal. Additional sources of impairment originating within optical fibers include Non-Linear Interference (NLI) caused by the Kerr effect (see [7]) and the SRS effect. Incorporating SRS into the analysis is challenging, as it requires solving a set of coupled Raman equations. To deal with these problems, complex models such as the well-established Generalized Gaussian Noise (GGN) model have been proposed. However, this model requires numerical integrations, which limits its utilization in the context of optical networking due to the large computational effort required. Fortunately, closed-form models such as Inter-channel SRS Gaussian Noise (ISRS-GN) [15] have also been proposed, which are much faster while still providing high accuracy [16].

A standard metric for quantifying the quality of a received optical signal is the SNR. It is commonly assumed that the received signal can be modeled as having a Gaussian distribution, which is a reasonable approximation for coherent detection over dispersion-uncompensated links. To analyze the impact of SRS on the SNR in a simplified way, we followed the procedure described in [8,15]. In addition, the gain of optical amplifiers is defined not only to compensate for the fiber losses but also for the losses of the MUX/DEMUX devices which are used to combine/separate the Super C- and Super L-bands. In this case, after coherent detection at the receiver side followed by electronic dispersion compensation, the SNR for the optical channel , after propagating over spans, is given as:

where denotes the launched average optical power of channel , is the accumulated ASE and is the accumulated NLI coefficient, which is computed using Equation (5) of [15]. In the other hand, , with being the power spectral density of the ASE noise, which is given by:

where is the Planck’s constant (in joule-second), is the channel frequency, is the noise figure (, with in dB), and is the uniform amplifier gain given by , where , with and denoting the MUX and DEMUX losses, respectively. It is worth noting that, although we have assumed a uniform gain in (3) to simplify the description, in reality the gain is frequency-dependent due to the contribution of SRS.

Typically, in a point-to-point optical transmission system, all optical channels are transmitted over the entire lightpath. However, in optical networks this is no longer the case, since in ROADMs the channels are added and dropped at different nodes according to the logical topology; i.e., the traffic demands and the routing, band, and wavelength assignment strategies. In this way, to evaluate the of channel at the receiver side, we must consider that this channel traverses multiple intermediate ROADMs and optical links. Let and denote the number of ROADMs and links traversed, respectively. For simplicity, each ROADM is modeled with a pass-through loss of 18 dB and add/drop losses of 15 dB, independent of the channel frequency. Therefore, post-optical amplifiers are required at each node to compensate for these losses; however, they introduce additional ASE noise, which must be included in the overall calculation.

In this work, we consider that in-line optical amplifiers, besides compensating for the passive losses (e.g., fibers and MUX devices), also compensate for the additional losses or gains due to SRS effects. As a result, all optical channels are assumed to have identical received power; i.e., . In this case, the for channel at the receiving side is given by [7]:

where is the SNR at the optical link, given by (2), with denoting the powers of the ASE noise generated at the add, intermediate, and drop ROADMs, respectively. Note that the SNR is evaluated using the fiber and system parameters given in Table 1 of [7].

3.2. Channel Capacity and Throughput Evaluation

The knowledge of makes it possible to determine the capacity of optical channel . Two capacity models are considered: (1) Shannon capacity, representing the theoretical maximum assuming Gaussian-modulated signals; and (2) real capacity, which accounts for practical modulation formats such as QPSK and M-QAM. The Shannon capacity is computed using the well-known Shannon formula; that is [7],

Here, the factor of 2 comes from the use of two orthogonal polarizations in fiber transmission, and is the net payload symbol rate, defined as , where represents the Forward Error Correction (FEC) and mapping overhead within the transponders. In the context of this work, we consider an overhead of 28% together with a symbol rate of 64 Gbaud, leading to The real capacity of each optical channel is then defined as the maximum net bit rate achievable by selecting the most efficient modulation format. Accordingly, it can be expressed as:

where denotes the constellation size of the modulation used on channel . A modulation format is considered feasible only when the estimated exceeds the minimum threshold () required to obtain a bit-error rate measured at the FEC input. Table 1 presents the corresponding thresholds along with the achievable bit rates.

Table 1.

Values of (@.

Taking into account the 12 THz of total bandwidth available per link in the Super C+L-band and considering a symbol rate of 64 Gbaud, the maximum number of wavelength channels per link is limited to , as previously discussed. Since each optical channel along a given lightpath traverses multiple links, this limitation can lead to traffic-demand blocking whenever at least one link on the path does not have available wavelength channels. Additionally, SNR blocking can occur when no optical channels with sufficient signal quality are available to support the requested traffic demand.

To evaluate the network performance, we used a previously proposed constraint routing algorithm [17] along with a first-fit wavelength assignment strategy. For each traffic demand the algorithm is adapted by employing Yen’s algorithm with to determine up to three candidate paths between nodes and [7]. Each candidate path, denoted as , can potentially be implemented via the optical channel . For every candidate , the algorithm evaluates the wavelength availability , starting from the C-band and the respective value of If both parameters satisfy the feasibility criteria, channel is established to serve the demand , and the residual capacities of all the links traversed by this channel are updated. Otherwise, if either is not available and value is not satisfactory in any of the three paths, the corresponding demand is blocked. By applying the referred strategy, we arrive at the matrix of established paths, , and the matrix of blocked demands , where

Considering that a full-mesh logical topology requires a total of unidirectional channels (one for each traffic demand), the average blocking ratio can be obtained by:

As previously discussed, network capacity corresponds to the highest aggregate data rate that the network can transport across all optical channels at the same time. It can therefore be obtained by summing the capacities of every optical channel in the set S, yielding:

Another metric relevant to this work is the network throughput, which reflects the effective data rate when the network operates under realistic conditions, including the presence of blocking. Let denote the set of optical channels that were successfully established by the RWA procedure (that is, all channels for which ). Consequently, network throughput is defined as:

A further metric used in the analysis is the average channel capacity of the network [12]. Assuming an expected utilization ratio equal to 1 for each channel, a full-mesh logical topology, and that only established channels contribute to the transported traffic, the average channel capacity is obtained as:

where = for the Shannon model and = for the real model.

4. Neural Network Design and SHAP

4.1. Artificial Neural Network Structure

An ANN consists of interconnected processing units, or neurons, arranged in multiple layers: an input layer, a set of one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [18,19]. This work proposes two models: one for the Shannon throughput and another for the real throughput. Both models consist of an input layer with 12 inputs (features), two hidden layers with 25 neurons each, and an output layer with two outputs (labels). Mathematically, the input features are represented by the array , and the labels by the array . Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions are applied in the hidden layers, while the output layer employs a linear activation function.

A detailed explanation of the steps required to build our ANN is provided in Reference [20]. Based on these guidelines, the hidden layers configuration is chosen to minimize the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of the loss function, considering the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer. Hyperparameter tuning takes place using the score and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) metrics [21], resulting in a learning rate of 0.01, a batch size of 64, no dropout, and early stopping after 960 epochs for the Shannon throughput model and 923 for the real throughput model.

The feature set includes topological attributes, such as the number of nodes, number of links, network diameter, algebraic connectivity, and statistical descriptors (maximum, minimum, average, and variance) of both link lengths and node degrees (see Table 2). Furthermore, the corresponding labels include the network throughput given by (10), and average channel capacity , given by (11).

Table 2.

Statistics of generated dataset features.

During model training, each dataset is divided into three parts: a training set, which is used to learn the model parameters; a validation set, which monitors the performance of the model during training; and a test set, which provides an independent evaluation after training is finished. Prior to this splitting, the data is pre-processed and randomly shuffled. Pre-processing adapts the raw data to make it more suitable for the training process, while shuffling ensures that the sets fairly represent the overall data distribution. In simple terms, pre-processing typically includes normalizing the input features, which may have different scales, so that they have zero mean and unit variance. Shuffling, on the other hand, randomizes the order of the samples to ensure that the training, validation, and test sets are representative of the entire dataset.

An essential component of training an ANN is the selection and optimization of its hyperparameters. These parameters define the learning behavior of the model and includes factors such as the number of hidden layers, the number of units in each hidden layer, the learning rate, the batch size, and dropout regularization. Different hyperparameter configurations are evaluated during training in order to obtain the best performance on the validation set. This iterative process is called hyperparameter tuning.

4.2. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

Understanding the impact of input features on model predictions and being able to compare them is essential for the interpretability and validation of machine learning models. In this context, Shapley values, a concept that comes from game theory, quantify each feature’s contribution to a prediction. In this work, feature importance is assessed using SHAP, a widely adopted method for explaining model predictions [22].

For inputs obtained from the dataset and processed by the ANN, SHAP evaluates the contribution of each feature by systematically perturbing the inputs and measuring the resulting change in the network’s output.

5. Simulation, Results and Discussion

5.1. Synthetic Topology Dataset Generation

This work relies on neural networks. There are different classical neural network models that could be employed, such as ANN, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) [23]. We have chosen the ANN because it is specifically designed to process tabular or structured data, which corresponds to our dataset. In contrast, CNNs are primarily used for grid-like data such as images or videos, while RNNs are appropriate for sequential data with temporal dependencies.

To train the ANN models, a dataset of 15,390 random networks was used. These networks were generated using the -neighbors model described in [7]. They span a wide range of physical and logical characteristics, simulating environments from small-scale to large-scale continental networks. Specifically, the networks were generated in a 2D space with side lengths ranging from 500 km to 1000 km in increments of 250 km, and from 1000 km to 5000 km in increments of 1000 km to account for both environments. In addition, the node count varied between 7 and 60, and the average node degree ranged from 2 to 4.8. The -neighbors model had the following parameters: and , and the minimum link distance was equal to 40 km. Using this model, one can generate multiple network instances, from which the various input parameters can be obtained. Their statistics are presented in Table 2, showing considerable variability. In practice, however, the actual inputs of the simulation tool described in [7] are the adjacency matrices corresponding to weighted graphs, allowing the computation of the two output labels under two physical layer assumptions: idealized Gaussian modulation and practical modulation formats. In both cases, the routing algorithm considers alternative shortest paths per demand, using a shortest-path-first ordering and a first-fit wavelength assignment policy as referred in Section 3.2.

The training set comprises 80% of the total dataset, while the validation and the test sets each include 10%. The training, validation and test datasets are used for fitting the model, tuning hyperparameters, and evaluating the model’s performance, respectively.

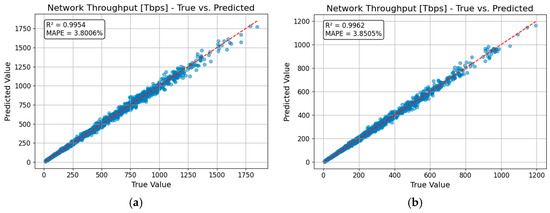

For testing purposes, Figure 1 presents scatterplots of the predicted values for the network throughput for both the Gaussian (a) and practical (b) modulation schemes. The red diagonal line in each plot represents the ideal case in which . Both models display excellent predictive accuracy, with slightly higher dispersion observed in the practical modulation case due to the added complexity of discrete modulation constraints. For the Gaussian model, the score on the test set is 0.9954, and for the practical modulation model, it is 0.9962. Note that the score ranges from 0 and 1, with 1 representing a perfect match between the model and the data, and 0 indicating that the model fails to explain the data. As mentioned before, another relevant performance metric is the MAPE, with lower values indicating that the predictions are close to the actual values. In this case, the Gaussian model achieved a MAPE of 3.8006%, while the practical modulation model achieved 3.8505%. Although the results for the average channel capacity are not presented, the model still presents a very good fit.

Figure 1.

Predicted versus true values for network throughput. (a) Gaussian modulation; (b) Practical modulation.

Although the ANN model has been trained only on synthetic random networks, it is important to understand its generalization capabilities for real-world networks. For this purpose, we use the relative error () metric, given by:

where and are the true and estimated values for label , respectively.

The results for network throughput are presented in Table 3 for Gaussian modulation (G) and practical modulation (P), considering different real-world networks, whose main characteristics are detailed in [24]. From the results presented, one can see that both models can provide quite accurate predictions on real-world topologies. In the case of Gaussian modulation, the throughput results are consistently below 10% with an average value of 6.09%. The model trained under practical modulation assumptions shows slightly lower accuracy. However, most of the prediction results still remain within a 10% error margin with an average relative error of 6.38%.

Table 3.

Accuracy of the ANN predictions for throughput of real-world networks.

A key advantage of both ANN models is their computational efficiency. For example, for the largest real-world network evaluated (CONUS60), the simulator’s runtime was 28.27 s under Gaussian modulation and 163.28 s under practical modulation. In contrast, the ANN’s inference time for the same network was only around 0.07 s, resulting in a speedup of approximately 400 times (Gaussian) and over 2300 times (practical).

5.2. SHAP Analysis

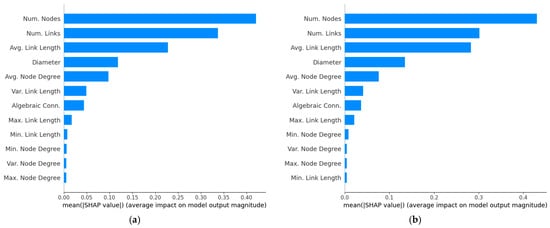

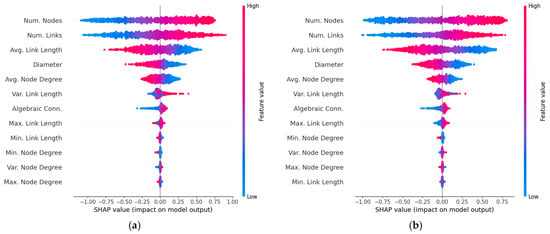

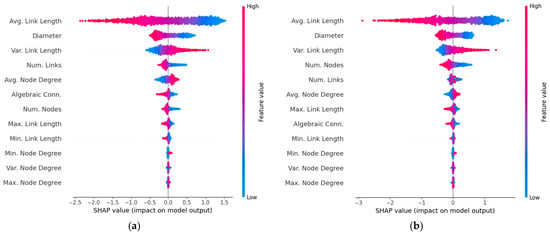

On the other hand, the SHAP analysis is performed on the test set of 1539 samples, for both Shannon and real throughput metrics. The results are presented in Figure 2 as a SHAP bar plot, which shows the mean absolute SHAP values across all test samples, providing a global ranking of feature importance, and in Figure 3 as a SHAP beeswarm plot, which illustrates the influence of feature values (high or low) on prediction outcomes at the instance level.

Figure 2.

SHAP bar plot based on mean absolute SHAP values (a) Shannon network throughput; (b) Real network throughput.

Figure 3.

SHAP beeswarm plot showing how varying feature values impact prediction. (a) Shannon network throughput (b) Real network throughput.

The SHAP bar plot in Figure 2a reveals that the seven most influential features for predicting network throughput are: number of nodes (N), number of links (L), average link length , network diameter (), average node degree , variance of the link length , and algebraic connectivity . On the other hand, the beeswarm plot, in Figure 3a, further shows that throughput increases with larger values of N, L, and , while the opposite trend is observed for , and ; that is, throughput decreases as these features increase. Notably, the trends reported for N, L and are consistent with the findings in [7], [9] and [11], respectively, while the trend for agrees with the results in [10]. The trends for and are also consistent with the results reported in [11].

Figure 2b and Figure 3b show the bar plots and the beeswarm plots for the scenarios corresponding to the real throughputs. In general, the same trends are kept. However, when compared with the figures of the Shannon throughput, some discrepancies can be observed in the real case: the impact of L is reduced in comparison with N, while the impact of and seems to increase. This outcome mainly results from the difference in how the SNR is evaluated in the two scenarios.

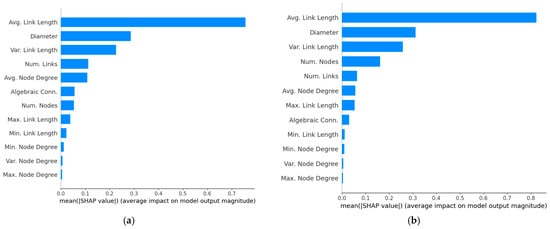

Figure 4 and Figure 5 provide equivalent results for the average channel capacity given by (11). The most evident difference compared to the throughput results is the change in the order of importance of various topological parameters. For example, the number of nodes, which is the most impactful parameter for throughput, moves to the seventh position for the average channel capacity in the Gaussian modulation case and to the fourth position in the case of practical modulation. In contrast, the average link length moves from the third position in Figure 2 and Figure 3 to become the most impactful parameter. This trend shift is expected, since throughput primarily depends on network-level aspects such as node density and blocking, whereas the average channel capacity is mainly affected by physical-layer aspects, particularly link distances, which has an adverse impact on signal quality degradation. Interestingly, Figure 5 shows exactly the same behavior for the impact of average link length. It is also worth understanding why the Gaussian modulation case is less sensitive to the number of nodes than the practical modulation case. As seen from (4), the SNR decreases as the number of nodes increases, which, as expected, is also confirmed by the beeswarm plots of Figure 5. However, this variation leads to a smoother reduction in capacity for the Gaussian case, whereas the practical modulations may experience larger drops in capacity when links are forced to switch to lower-order modulation schemes (see (6)), making them consequently more dependent on node density.

Figure 4.

SHAP bar plot based on mean absolute SHAP for average channel capacity. (a) Gaussian modulation; (b) Practical modulation.

Figure 5.

SHAP beeswarm plot showing how varying feature values impact prediction of average channel capacity. (a) Gaussian modulation; (b) Practical modulations.

5.3. Limitation of the Study

The primary goal of this study is to identify the relative influence of various topological parameters on network throughput and average channel capacity in a C+L-band optical backbone, using data obtained from an ANN model. One limitation is that the ANN model was trained under simplified scenarios, such as assuming a full-mesh logical topology, a number of network nodes ranging from 7 to 60, and a highly approximated modeling of physical impairments. Although more realistic scenarios, such as incorporating actual traffic matrices, could yield different results, we believe that the general trends identified in this study are preserved, as happens, for example, when comparing our results for the Shannon and real cases. Nevertheless, a more detailed analysis of this problem is worthwhile and will be the focus of future work.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, an approach was proposed to study the impacts of different topological parameters on the throughput and average channel capacity of optical networks based on Super C+L-band transmission. The approach employed two ANN models to predict the Shannon and real throughputs, each with an input layer of 12 features (topological parameters), two hidden layers of 25 neurons each, and an output layer with two labels, one of which corresponds to the throughput and the other to the average channel capacity. The models were trained on synthetic datasets generated using a previously developed simulation tool that incorporates detailed physical layer modeling, which includes ASE noise and non-linear effects in optical fibers, such as Kerr and SRS effects. The ANNs showed excellent predictive accuracy, with scores of 0.9954 and 0.9962, and MAPE values of 3.8006% and 3.8505% for Shannon and real throughputs, respectively. Furthermore, to interpret the ANN model predictions, we applied the SHAP method, which allowed us to identify the relative importance of different topological parameters. The results demonstrate that the order of importance of topological parameters changes significantly when moving from the throughput to the average channel capacity. For the first metric, the parameters that have the most critical effect are number of nodes and links, average link length, network diameter, average node degree and, to a lesser extent, algebraic connectivity. For the second metric, the six most relevant parameters are average link length, diameter, variance of the link length, number of nodes, number of links, and average node degree. These results indicate that network planning must account for these factors to fully leverage the potential of Super C+L-band optical networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M. and J.P.; methodology, T.M. and J.P.; software, T.M.; validation, T.M.; formal analysis, T.M.; investigation, T.M. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and J.P.; visualization, T.M.; supervision, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., and, when eligible, co-funded by EU Funds under project/support UID/50008/2025—Instituto de Telecomunicações.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

João Pires acknowledges the Instituto de Telecomunicações and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) for their support for his research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruiz, M.; Hernandez, J.A.; Quagliotti, M.; Salas, E.H.; Riccardi, E.; Rafel, A. Network traffic analysis under emerging beyond-5G scenarios for multi-band optical technology adoption. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, F36–F47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P.J. The future of communications is massively parallel. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Virgillito, E.; Curri, V. Band-division vs. space-division multiplexing: A network performance statistical assessment. J. Lightw. Technol. 2020, 38, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, D.; Zou, H.; Liu, D.; Yan, B.; Yan, B.; Shi, H.; Li, H. First field demonstration of real-time sub-100-Tb/s transmission with net 1.2-Tb/s channels over 12-THz-wide Super C+L band along 305-km G.652.D fiber. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communications Conference, San Franciso, CA, USA, 30 March–3 April 2025. Paper Th3C.1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, S.; Pfau, T.; Awadalla, A.; Aydinlik, M.; Geyer, J. Real-time 1.2 Tb/s large capacity DCI transmission. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communications Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 24–28 March 2024. Paper W3H.3. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, T.; Pires, J.A. Throughput analysis of C+L-band optical networks: A comparison between the use of band-dedicated and single-wideband amplification. Electronics 2025, 14, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, D.; Killey, R.; Bayvel, P. Achievable rate degradation of ultra-wideband coherent fiber communication systems due to stimulated Raman scattering. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 13024–13034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessinari, R.S.; Paiva, M.H.M.; Monteiro, M.E.; Segatto, M.E.V.; Garcia, A.S.; Kanellos, G.T.; Nejabati, R.; Simeonidou, D. On the impact of the physical topology on the optical network performance. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE British and Irish Conerence on Optics and Photonics, London, UK, 12–14 December 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, D.; Durrani, S.; Zervas, G.; Killey, R.I.; Bayvel, P. On the relationship between network topology and throughput in mesh optical networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.06708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashimori, K.; Tanaka, T.; Inuzuka, F.; Ohara, T.; Inoue, T. Key physical topology features for optical backbone networks via a multilayer correlation. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, B23–B32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essiambre, R.-J.; Tkach, R.W. Capacity Trends and Limits of Optical Communication Networks. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Châtelain, B.; Bélanger, M.P.; Tremblay, C.; Gagnon, F.; Plant, D.V. Topological wavelength usage estimation in transparent wide area networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2009, 15, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Sadeghi, R.; Correia, B.; Costa, N.; Napoli, A.; Curri, A.; Pedro, J.; Pires, J. Optimal pay-as-you-grow deployment on S+C+L multi-band systems. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communications Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 March 2022. W3F.4. [Google Scholar]

- Semrau, D.; Killey, R.I.; Bayvel, P.A. Closed-form approximation of the Gaussian noise model in the presence of inter-channel stimulated Raman scattering. J. Lightw. Technol. 2019, 37, 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiolini, P.; Jiang, Y. Recent advances in the modeling of the impact of nonlinear fiber propagation effects on uncompensated coherent transmission systems. J. Lightw. Technol. 2017, 35, 458–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A. Designing Ultra-High Bandwidth Optical Networks Using Machine Learning Techniques. Master’s Thesis, Electrical and Computer Engineering, IST, University of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci, F.; Rottondi, C.; Nag, A.; Macaluso, I.; Zibar, D.; Ruffini, M.; Tornatore, M. An overview on application of machine learning techniques in optical networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 1383–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Gulistan, A.; Rahman, B. Machine learning regression approach to the nanophotonic waveguide analyses. J. Lightw. Technol. 2019, 37, 6080–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.; Pires, J. Using Artificial Neural Networks to Evaluate the Capacity and Cost of Multi-Fiber Optical Backbone Networks. Photonics 2024, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Cordova-Esparza, D.M.; Ramirez-Pedraza, A.; Chavez-Urbiola, E.A.; Romero-Gonzalez, J.A. Loss functions and metrics in deep learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2307.02694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Amudha, P.; Sivakumari, S. Deep learning techniques: An overview. In Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications, Proceedings of AMLTA 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, F. Planning of Survivable Ultra-High Bandwidth Optical Networks Using Deep Learning Techniques. Master’s Thesis, Electrical and Computer Engineering, IST, University of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, October 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).