Abstract

In autonomous driving scenarios, the presence of dynamic objects can significantly degrade the precision and recall of loop-closure detection. To further improve robustness, this paper proposes a loop-closure detection framework with dynamic-object suppression. The framework jointly exploits camera and LiDAR sensors to obtain rich environmental information. More importantly, we introduce a probabilistic dynamic suppression mechanism at the local-descriptor level. Based on cross-path consistency between the image and bird’s eye view (BEV) branches and the temporal persistence of BEV grid-cell activations, we construct two complementary pieces of evidence for detecting anomalous, potentially dynamic content. These two cues are then fused in probability space using a Bayesian formulation to produce interpretable dynamic posterior probabilities for each local feature. The resulting probabilities are converted into soft suppression weights that reweight the local descriptors before NetVLAD aggregation, yielding cleaner local descriptors for loop-closure retrieval. Compared with the baseline, the proposed method improves not only average precision but also Recall@100 and F1-score. On the public KITTI-360 dataset, our approach achieves significant performance gains. In particular, on the challenging KITTI-360-00 sequence, average precision (AP) increases from 0.895 to 0.945, and similar improvements are observed on other sequences, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed framework.

1. Introduction

As mobile robotics and autonomous driving technologies advance rapidly, environmental perception and autonomous localization have become critical for high-precision navigation and safe travel. In unknown environments, the primary objective of mobile intelligent platforms, such as service robots and autonomous vehicles, is to build a map and estimate their own pose—a challenge widely known as Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) [1,2]. Loop-closure detection, a key component of SLAM, seeks to mitigate accumulated drift, enhance localization accuracy, and enable more efficient obstacle-aware navigation. However, dynamic elements in real-world road scenes disrupt candidate retrieval and geometric verification, leading to increased mismatches and false closures. Improving robustness under dynamic conditions remains a central and challenging research focus.

From a pipeline perspective, loop-closure detection [3] typically consists of candidate retrieval followed by geometric verification. The first stage generates a candidate set using global or local descriptors, while the second stage filters these candidates through geometric consistency checks. Classical visual methods rely on handcrafted features, such as scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) and speeded up robust features (SURF [4,5,6,7]), which provide scale and rotation invariance for robust matching. Global descriptors like gist descriptor (GIST) and histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) offer strong real-time performance. SeqSLAM [8] utilizes temporal consistency to handle severe illumination and seasonal variation, although it is sensitive to speed drift. With the advent of deep learning and computer vision, many learned feature extraction and matching frameworks have emerged. SuperPoint [9] learns keypoints and descriptors in a self-supervised manner, and SuperGlue [10] aggregates contextual information to enhance geometric verification. To reduce latency in architectures with high computational demands, lightweight matchers like LightGlue [11] and Alike [12] minimize inference delays while maintaining loop-closure accuracy, making them suitable for online operation. Recent advancements also integrate large-scale pretrained models with strong semantic understanding into loop-closure detection, delivering promising results in scenes with repetitive textures and complex structures.

Significant progress has also been made in the LiDAR domain. Scan Context [13] encodes a single-frame point cloud into a polar grid and performs rotational alignment along the ring direction for efficient retrieval. Multiview 2D Projection (M2DP [14]) uses multi-view projection followed by singular value decomposition to generate a compact global descriptor. MinkLoc3D [15] employs sparse voxel convolutions to extract global features, achieving a favorable balance between efficiency and cross-scene generalization. Overlap Transformer [16] projects point clouds to a range image and utilizes attention mechanisms to enhance robustness to viewpoint changes and occlusion. Overall, while vision and LiDAR methods now span a wide spectrum—from handcrafted to learned, from local to global, and from single-frame to temporal—there remains significant potential for improvement in real-world road environments characterized by strong dynamics and rapid changes.

In complex environments, using a single sensor for loop-closure detection has inherent limitations. LiDAR is insensitive to changes in illumination and provides high-accuracy distance measurements, offering stable, near-scale-invariant geometric structures, particularly advantageous under strong lighting variations or adverse weather conditions. However, in environments such as corridors, tunnels, and other scenes with repetitive structures or constrained viewpoints, local geometry can become ambiguous, and high-density point clouds introduce challenges related to real-time processing and storage. In contrast, cameras offer advantages in terms of low cost, high resolution, and rich texture, making them strong in appearance-based recognition. However, cameras degrade under low light, strong dynamics, and rapid motion, and are more sensitive to motion models and image quality. Therefore, despite the individual limitations of both sensors, their complementary characteristics provide a new approach for improving loop-closure detection performance in complex environments.

Research on handling dynamic objects broadly falls into two categories: explicit removal and background restoration, and implicit multimodal fusion [17,18]. Explicit methods typically rely on semantic segmentation, optical-flow analysis, or motion-consistency estimation to detect and filter dynamic regions, thereby recovering a stable static scene. Representative approaches include DynaSLAM2 [19], which updates dynamic masks by combining semantic and geometric constraints; DynaTM-SLAM [20], which repairs dynamic areas in dense maps using semantic cues and module matching; and DP-SLAM [21], which suppresses dynamics through joint depth estimation and semantic detection. A primary limitation of these semantics-driven pipelines is they often require additional segmentation or detection networks, leading to considerable computational costs. Moreover, they usually produce hard, binary masks and treat all masked regions equally, which may over-suppress semi-static structures near moving-object boundaries and remove potentially useful features, thus negatively impacting recall.

Implicit fusion methods enhance overall reliability by exploiting the complementary strengths of multiple sensors. While effective, most of these methods focus on robust data integration or generating fused global descriptors, often lacking a fine-grained, probabilistic mechanism to quantify and suppress dynamic interference at the local feature level. TS-LCD [22] adopts a two-stage visual-LiDAR loop-closure strategy to improve the localization accuracy. MSF-SLAM [23] further integrates inertial measurement unit (IMU) data with multi-source sensing from LiDAR and cameras to enhance system consistency and reliability. MULLS [24] designs a multimodal local descriptor that matches joint image and point-cloud features for dynamic scenes. LVIO-FUSION [25] tightly couples LiDAR, stereo cameras, IMU, and Global Positioning System (GPS), employing an actor-critic reinforcement learning scheme [26] to adapt sensor weights. BEVPlace [27] constructs fused descriptors from point clouds and image features to improve localization in complex environments. AdaFusion [28,29] introduces confidence-aware feature weighting to adjust the respective contributions of LiDAR and images without the need for external labels.

Beyond the aforementioned work, several recent multimodal SLAM and localization methods further validate the trend toward adaptive fusion. Lin et al. proposed AWF-SLAM [30], a graph-based adaptive weighted fusion framework that integrates LiDAR, IMU, and camera data by dynamically adjusting weights based on sensor consistency. However, their method focuses on achieving robust pose estimation in perception-degraded and GNSS-denied environments, and does not address dynamic object suppression at the feature level or the robustness of loop-closure descriptors. Separately, Chghaf et al. presented the extended Multi-Modal Loop-Closure framework [31], which fuses camera and LiDAR place recognition modalities via a similarity-guided particle filter built on ORB-SLAM2. While their fusion scheme operates at the loop closure score level, it does not explicitly model dynamic object uncertainty probabilistically at the local descriptor level.

Their fusion operates at the level of modality-specific loop-closure scores, whereas our method performs descriptor-level probabilistic dynamic suppression before global aggregation, yielding cleaner descriptors that can be plugged into existing LCD pipelines.

Building on the above analysis, this paper proposes an interpretable loop-closure detection framework tailored to dynamic environments, whose novelty lies not in simply combining LiDAR and camera data but in introducing a lightweight, probabilistic dynamic-suppression mechanism in a shared local feature space. Without modifying the standard NetVLAD-based retrieval and geometric verification backbone, the method extracts two complementary pieces of evidence of anomalous behavior: cross-path descriptor consistency between the image and BEV branches to capture instantaneous discrepancies, and BEV grid-cell hit persistence to characterize temporal stability. These cues are fused within a Beta-Bernoulli prior-posterior formulation to produce physically meaningful per-feature dynamic probabilities. Unlike methods like DynaSLAM that rely on semantic segmentation to generate binary masks, our framework applies the generated probabilities as soft weights to local descriptors before global aggregation, thereby continuously mitigating the impact of dynamic information. This significantly improves the robustness of geometric verification and localization accuracy in highly dynamic scenes while maintaining high recall.

To validate effectiveness, we conduct systematic experiments on the KITTI-360 dataset. The results show that the method consistently improves in both accuracy and F1 score across multiple sequences and dynamic intensity ranges, demonstrating its effectiveness in complex road environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pipeline Overview

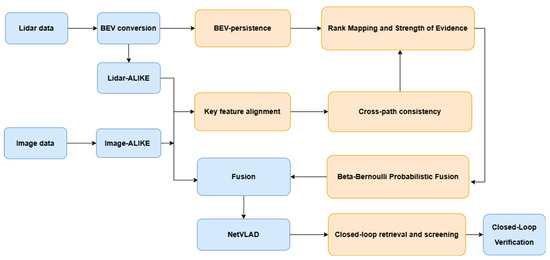

This paper introduces the identification and removal of anomalous information into the FUSIONLCD [32] framework and incorporates temporal consistency filtering during the retrieval and verification stages to enhance overall robustness. The complete process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Complete process of loop-closure detection framework.

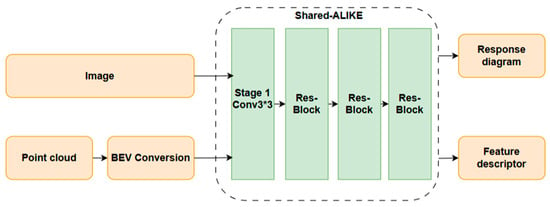

Specifically, we use the acquired raw image and point cloud data as inputs. First, the point cloud data is projected using the BEV method and aligned with the 2D image, ensuring that 3D information is uniformly represented on the 2D plane. This alignment enables the subsequent operations to be performed using the same feature extraction network. Figure 2 illustrates the feature extraction process of the Alike network.

Figure 2.

Alike-based unified feature extraction.

When using global descriptors for retrieval and verification, the presence of dynamic information often skews the similarity measurement, increasing the likelihood of false matches. To address this, we propose using two complementary pieces of information—cross-path consistency and the persistence of BEV raster features—as the basis for detecting dynamic anomalies. Cross-path consistency asserts that the same physical surface should exhibit similar feature directions in both the image path and the BEV path. Errors caused by dynamic information or cross-modal alignment can disrupt this consistency, allowing for the identification of anomalous feature information. Additionally, since the observed information is instantaneous, we introduce BEV raster feature persistence as a supplementary measure to mitigate errors due to misjudgments based on a single piece of data. Raster information persistence evaluates anomalies by examining the stability of feature hits over time. Static structures are observed and hit repeatedly within the same raster, while dynamic objects typically produce intermittent hits within corresponding intervals.

Considering that the results obtained above may differ in scale and numerical range, we apply rank mapping to normalize the two sets of results with arbitrary distributions, bringing them onto a comparable probability scale. This step helps mitigate numerical biases caused by different sensor paths and viewpoints. When fusing the normalized results, direct weighted accumulation could introduce errors due to the inaccuracy of certain information. To address this, we introduce an information strength indicator to assess the reliability of each piece of data. In the probability space, we adopt a Bayesian fusion method, treating the calibrated probability information and information strength as pseudo-counts. This allows for a bounded, monotonic posterior update of the probability of a feature point being dynamic, yielding a dynamic probability at the keypoint level. This approach ensures that reliable information predominates while reducing the influence of unreliable data. Finally, the dynamic posterior probabilities are applied to local descriptors, resulting in purer descriptor information.

The refined local descriptors are aggregated by NetVLAD to form global descriptors. During loop-closure retrieval and candidate selection, we impose geometric and temporal consistency constraints to suppress isolated false positives, producing a more reliable candidate set. A subsequent stringent verification step yields robust loop-closure decisions.

2.2. Dynamic Identification and Suppression

At the same physical location, local descriptors from the image branch and the bird’s-eye-view (BEV) branch are expected to be consistent. Static structures exhibit strong directional alignment, whereas dynamic effects disrupt this alignment. We detect such disruptions by quantifying cross-path consistency.

Let and denote the local descriptors at the i-th BEV grid cell and its aligned image location, respectively. We first perform L2-normalization to eliminate scale effects:

In Equation (1), denotes the Euclidean norm, and c > 0 is a small constant used to avoid division by zero for near-zero vectors. We set in our implementation. The normalized descriptors and are then used to compute the cosine similarity:

In Equation (2), U measures the directional agreement between the two branches. It lies in [−1, 1]. We further map U to [0, 1] by . When U is close to 1, the two descriptors are strongly aligned, and S1 is close to 0, including a high likelihood that the feature belongs to static structure. Conversely, as U departs from 1, the feature becomes increasingly suspect of being dynamic.

However, using cross-path consistency alone tends to produce false alarms under strong illumination changes or shadows, and the resulting decision is instantaneous. To improve accuracy, we add temporal BEV feature persistence as a complementary cue. The idea is to judge the stability of a grid cell by the hit frequency of its features in recent history. We ask a simple question: has this feature been consistently hit over the recent time window? If yes, it is more likely static, since the surface of a static object is repeatedly observed and continues to hit the same grid as the vehicle passes. If no, it is suspected to be dynamic, because dynamic content exhibits low-frequency, intermittent hits. As shown in Equation (3), we define a binary hit indicator to denote whether the BEV grid cell g is hit at time t. We obtain a confidence response from the Alike BEV head.

Subsequently, we maintain and update the hit count Ht and the exposure count Mt over time, which provide evidence for distinguishing static from dynamic features.

In Equation (4), is a forgetting factor which controls the weighted influence of historical observations on the current statistics. As approaches 1, the effective temporal window lengthens, resulting in smoother estimates; a smaller places a greater emphasis on recent observations. In this experiment, the value of was determined to be 0.9 through tuning on the validation set, achieving a necessary compromise between estimation stability and responsiveness to dynamic changes. Ht and Mt denote, respectively, the accumulated statistics for the hit count and the exposure count up to time t. To prevent zero denominators during the initial phase and to introduce a prior that is unbiased toward either static or dynamic states, we initialize both Ht and Mt to 0.5. Subsequently, at each time step t, the values stored at the previous time step, Ht−1 and Mt−1, are first read to compute the current persistent hit rate . Then, the values for the next step, Ht and Mt, are updated according to Equation (4), and the updated results are written back for use in the subsequent observation:

In Equation (5), is the probability that the grid cell has been persistently hit; it can also be interpreted as the static confidence of that grid cell within the recent time windows. To facilitate correspondence with the other source of anomaly information, we perform a transformation using to obtain the dynamic confidence result while maintaining the value range of [0, 1]. When approaches 1, the value of S2 approaches 0. This indicates that the feature within the grid cell has been consistently hit, suggesting a higher likelihood of representing static information. Conversely, a larger indicates a greater possibility that the information is dynamic. Figure 3 shows the abnormal information identified by the method in the image and point cloud data.

Figure 3.

Effects of recognition methods on images and point clouds.

2.3. Fusion of Verification Evidence

The two verification cues above have different numerical ranges and exhibit distinct distributions. Directly applying weighted fusion can therefore yield unreliable decisions. To obtain more dependable dynamic estimates, we map the raw scores onto a common probability scale using the empirical cumulative distribution function. Concretely, within each frame, we perform rank-based mapping over all candidate features. Let {} denote the raw cross-path consistency scores in the frame, and {} denote the BEV persistence scores. Each set is mapped to a unified scale by its ranks. With N valid samples and rank indicating the ascending order index, the calibrated values are obtained according to Equation (6):

In Equation (6), rank() returns the ascending-order index within the corresponding set. Thus, and can be interpreted as calibrated probabilities that encode the relative position of each feature within the empirical distribution of the two cues. This mitigates scale bias across scenes, making the two cues comparable. Because rank-based scaling with limited samples can exhibit short-term, frame-to-frame jitter, we apply an exponential moving average over time to the calibrated scores, yielding smoothed yet responsive series and :

where y is a smoothing factor applied to the rank-calibrates scores. Equation (7) can be viewed as a first-order low-pass filter that suppresses frame-to-frame noise introduced by finite-sample ranking while still allowing for slow changes in scene dynamics to be reflected in the scores. Larger values of y assign more weight to the past and produce smoother trajectories, whereas smaller values make the scores react more quickly to new evidence but may reintroduce jitter. In this paper, we set y = 0.9, which corresponds to averaging information over roughly the last ten frames and matches the typical temporal correlation of neighboring frames in our datasets. The initialization of the smoothed scores and is also bashed on the principle of not introducing a prior bias towards either static or dynamic information. Consequently, we initialize both smoothed sequences to 0.5. This value represents a neutral state before any information has been accumulated.

Furthermore, to account for scene-dependent reliability of the two cues, we introduce an information-strength term. Because the cues need not contribute equally and one may be unreliable in some cases, the information strength is adjusted dynamically according to each cue’s effective sampling ratio and historical stability. The information strength for the cross-path consistency () depends on the proportion of valid image samples, while the information strength of raster persistence () depends on the proportion of historical frames, in which the raster containing the feature has been observed. We treat the acquired proportions as pseudo sample sizes within a Beta-Bernoulli conjugate model for performing a Bayesian update. Ultimately, the posterior mean of this model is then used as the fused dynamic probability, q, at that location.

In Equations (8) and (9), both and are greater than zero and together control the bias of the prior distribution on the static or dynamic state. We select a weakly informative symmetric prior by setting . This choice ensures that the posterior mean is initialized to 0.5 and progressively becomes data-driven as evidence accumulates.

We also set in Equation (10), which is a very small constant, to avoid division by zero. Finally, we convert the dynamic probability into a soft suppression weight w = 1 − q, and reweight each local descriptor as before aggregation. Here, represents the original local descriptor, and denotes the dynamically suppressed local descriptor. This method down-weights features with high dynamic probability, thereby effectively attenuating dynamic interference and yielding cleaner local descriptors for subsequent NetVLAD aggregation.

2.4. Retrieval and Verification

After dynamic suppression, local descriptors are aggregated by NetVLAD [15] to form more robust global descriptors. For retrieval, we compute cosine similarity between the query and database global descriptors to obtain a candidate set and discard frames that fall within a short temporal window of the query to avoid trivial self-matches. For each remaining pair (i, j), we estimate a 2D rigid transformation in pixel coordinates using random sample consensus (RANSAC); the geometric score is the Euclidean norm of the recovered translation vector, with smaller values indicating a higher likelihood that the pair depicts the same place.

To further reduce false positives, we enforce temporal consistency. Among geometrically verified pairs, we compute the time difference and take its mode as the reference for the query. We retain only candidates satisfying and reject the rest as temporally inconsistent. The tolerance is set from a dispersion estimate based on the median absolute deviation. Among the temporally consistent candidates, we adopt a time-consistency-first, geometry-dominated ranking policy, which further improves both precision and recall.

3. Results

3.1. Datasets and Experiment Settings

All experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an AMD Ryzen 9 7950X (16 cores), an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU, 128 GB of RAM, and a 2 TB hard drive. We evaluate loop-closure detection on the KITTI [33] and KITTI-360 [34] datasets. Training is performed on KITTI sequences 00, 05, 06, 07, and 09. Table 1 summarizes the scale and loop-closure density of the training sequences. Sequences 00 and 05 exhibit high loop-closure frequency and strong dynamic activity, whereas sequences 07 and 09 contain fewer closures and comparatively sparser environments.

Table 1.

KITTI training-set sequence characteristics.

We further evaluate on KITTI-360 sequences 00, 04, 05, 06, and 09. These sequences balance scene diversity and coverage, spanning urban blocks, residential areas, and highways, and they contain abundant loop closures and dynamic activity. Figure 4 presents representative images from several KITTI-360 sequences.

Figure 4.

KITTI-360 dataset images.

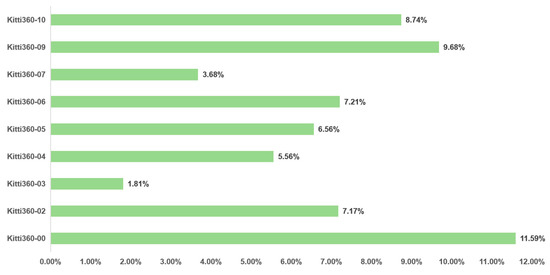

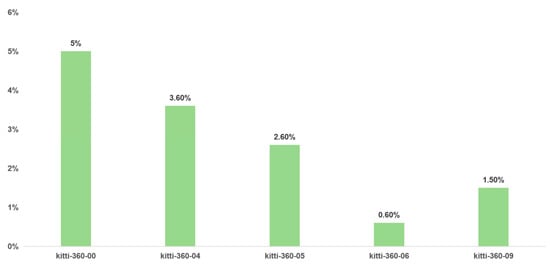

Sequence statistics are computed from the pixel-level semantic annotations released by the KITTI-360 benchmark. For each frame, we tally the dynamic categories—pedestrian, rider, and car—to obtain the proportion of dynamic content per sequence. Because some sequences contain few loop closures and are therefore unsuitable for evaluation, we ultimately select KITTI-360 sequences 00, 09, 06, 05, and 04 to assess the gains from the proposed dynamic-suppression framework. Although sequence 10 exhibits a relatively high dynamic ratio, it contains too few closures for the effect to be clearly observed. Figure 5 illustrates the proportion of dynamic information in each sequence of the dataset.

Figure 5.

The proportion of dynamic information contained in the KITTI-360 sequence.

The goal of our experiments is to quantify the framework’s impact on loop-closure detection. We report three metrics: AP, recall at 100 (R@100), and F1-score. AP summarizes the area under the precision–recall curve. R@100 measures the fraction of ground-truth closures retrieved within the top 100 candidates. F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing an overall assessment. To ensure a fair comparison, all baselines and ablation variants are evaluated with identical parameters and evaluation settings.

3.2. Loop-Closure Detection

To assess the performance gains of the proposed framework, we compare it with M2DP [14], Scan Context [13], Overlap Transformer [16], and FUSIONLCD [32] on the KITTI-360 dataset. The Table 2 strongly corroborate the effectiveness of our approach.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of loop-closure detection methods on the KITTI-360 dataset.

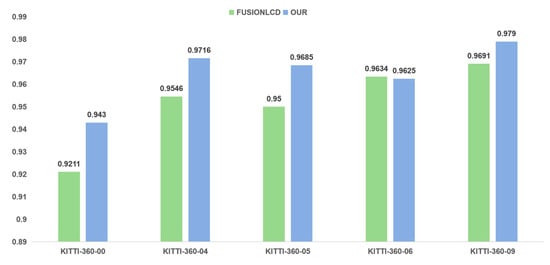

The results show that traditional methods, such as M2DP and Scan Context, degrade in dynamic scenes and under repetitive structures. In contrast, the deep learning baseline FUSIONLCD exhibits clear robustness gains, and our proposed framework achieves further improvements on KITTI-360, delivering the best overall AP, R@100, and F1-score. Because it balances precision and recall, it highlights the net benefit of our dynamic suppression. The gains are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

F1-score improvement effect.

To evaluate the effectiveness of suppression under different dynamic intensities, we partition KITTI-360 into high-dynamic sequences (00, 09) and low-dynamic sequences (04, 05, 06) based on the benchmark metadata. Experimental results are shown in Figure 7. On the high-dynamic sequence 00, our method achieves a clear improvement; in general, stronger dynamics yield larger gains, consistent with the design objective of mitigating dynamic interference. Improvements are observed across all sequences. Although sequence 09 is labeled high-dynamic, its gain is smaller than that of sequences 04 and 05.

Figure 7.

Accuracy improvement of dynamic suppression method across sequences with different dynamic intensities.

This is a headroom effect rather than a limitation of the method: the baseline precision is already 96.8%, leaving only 3.2% possible improvement. Within this margin, our framework still delivers a 1.5% absolute increase—nearly half of the remaining headroom. By contrast, low-dynamic sequences start from lower baselines and thus admit larger absolute gains.

3.3. Ablation Study

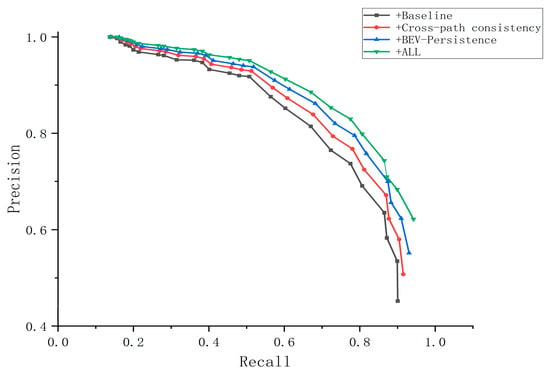

To assess the individual contributions of the two dynamic-judging cues and their synergy, we conduct an ablation on the high-dynamic KITTI-360-00 sequence. Aside from the cue combinations, all other settings and hyperparameters are kept identical across control groups. We consider four variants: the baseline without any suppression, cross-path consistency only, BEV grid-cell persistence only, and the fusion of both cues. Results are shown in Figure 8 and Table 3.

Figure 8.

Precision–recall curve under ablation experiment.

Table 3.

Ablation experiment results on KITTI-360-00.

Compared with the baseline, introducing either single cue increases localization precision but sacrifices part of the loop-closure recall, indicating mild over-suppression when used alone. In contrast, fusing the two cues yields a suppression effect that both significantly improves precision and confines the recall drop to an acceptable range. The tabulated results align with the precision–recall curves: single-cue variants dip on the high-recall end, whereas the fused curve remains overall steadier in the mid-to-high recall regime. This suggests complementary error correction: cross-path consistency better captures instantaneous anomalies, while BEV persistence is stronger on temporal irregularities. Used together, they suppress false positives and residual dynamics, delivering higher loop-closure precision without a noticeable loss in recall.

4. Discussion

Based on the preceding experimental validation, the proposed multimodal dynamic suppression framework demonstrates a significant improvement in loop-closure detection robustness in dynamic environments. The following discussion delves into the underlying mechanisms of this performance gain and outlines future research directions.

The fundamental reason for the performance improvement lies in how the two detection cues characterize the nature of dynamic interference from different dimensions. The Cross-Path Consistency cue acts as a high-frequency anomaly detector. It leverages the inherent geometric alignment between the camera and LiDAR, performing a spatially aware, instantaneous check. The presence of dynamic objects disrupts this alignment, causing directional inconsistency between image and BEV feature descriptors. This is precisely why our method responds rapidly to moving objects. However, ablation studies reveal that using this cue alone results in a recall drop, exposing its inherent weakness: sensitivity to appearance changes caused by non-dynamic factors like severe illumination variations.

To address this limitation, the BEV Grid Cell Persistence cue introduces crucial temporal context. It moves beyond instantaneous observations by evaluating the persistence of feature points over time. By analyzing historical observation data to identify consistently present structures, it effectively filters out dynamic objects that may appear static momentarily but are transient over the observation history.

Therefore, the core advantage of our framework lies in its synergistic error-correction capability. The Bayesian fusion model is not a simple weighted average but a dynamic process of complementary information integration. For instance, for a newly appearing static object, even if its BEV grid persistence is initially low, strong cross-path consistency evidence can dominate the fusion process. Conversely, a static object whose cross-path consistency is temporarily reduced due to specific lighting can be “pardoned” due to its high persistence score. This complementarity is the intrinsic reason why our fused approach achieves both high precision and high recall in the ablation studies.

Compared to baseline methods like FUSIONLCD that also employ multimodal fusion, our innovation lies not in the fusion itself, but in what information we fuse. Our “suppression-first, matching-later” paradigm enables subsequent similarity calculations to operate on purified descriptor information, reducing the contamination of global descriptors by dynamic content. This directly explains the more substantial AP improvement on the highly dynamic KITTI-360-00 sequence.

Despite the accuracy improvements achieved by the proposed method, several limitations remain. First, compared with a baseline loop-closure detection pipeline that relies solely on NetVLAD, our framework introduces additional modules to compute cross-path consistency, maintain BEV occupancy statistics, and perform Bayesian fusion. These components incur non-negligible computational overhead, so the current implementation is more suitable for offline evaluation or platforms with moderate computational resources and has not yet been fully optimized for strict real-time operation. As future work, we plan to reduce this overhead while preserving most of the accuracy gains, for example, by accelerating descriptor retrieval and matching (such as LightGlue) to further improve the overall runtime efficiency.

In addition, our experiments are conducted mainly on daytime urban driving sequences from KITTI and KITTI-360, where both LiDAR and camera signals are of relatively good quality. We have not yet systematically evaluated the method under nighttime, low-visibility, extremely high-dynamic or severely low-texture conditions. In such scenarios, the statistical behavior of the two pieces of evidence we rely on—cross-path descriptor consistency and BEV occupancy persistence—may change, potentially reducing the discriminative power of the inferred dynamic probabilities. As part of future work, we plan to perform more comprehensive evaluations on datasets that cover nighttime and adverse-weather conditions, and to incorporate a lightweight semantic segmentation network into the proposed Bayesian fusion framework as a source of semantic prior, so as to better distinguish static and dynamic regions and further improve generalization across diverse environments.

5. Conclusions

In the fields of autonomous driving and mobile robotics, accurate and reliable loop-closure detection is crucial for maintaining long-term localization accuracy and constructing consistent maps. However, the widespread presence of dynamic objects on roads can adversely affect the global descriptors used in loop-closure retrieval, thereby compromising the precision and robustness of loop-closure detection. To address this issue, this paper proposes a multimodal loop-closure detection framework with dynamic suppression, which primarily leverages two complementary cues and a probability-driven approach to enhance loop-closure performance. We first utilize the instantaneous geometric discrepancy between image features and BEV features. Subsequently, we identify dynamic entities lacking stability from a temporal statistical perspective using BEV grid cell persistence. Meanwhile, we adopt a Beta-Bernoulli conjugate model to perform weighted fusion of these two complementary cues, ensuring that more reliable information dominates the fusion process while less reliable information is attenuated, thereby achieving highly robust dynamic probability estimation. The resulting dynamic posterior probability is ultimately converted into soft suppression weights, effectively mitigating the interference of dynamic information while maximally preserving the static valid information in the descriptors.

Comprehensive experimental analysis on the public KITTI-360 dataset validates the superiority of the proposed framework. The results demonstrate that our method significantly improves loop-closure detection accuracy in dynamic scenes, particularly on the highly dynamic KITTI-360-00 sequence. The average precision (AP) is markedly increased from the baseline of 0.895 to 0.945, while the recall rate is maintained within an acceptable range. This performance improvement strongly confirms the effectiveness of our dynamic suppression method based on complementary cues.

In summary, this study provides an effective paradigm for feature enhancement and denoising in dynamic environments for loop-closure detection. The performance improvement achieved through this interpretable probabilistic fusion mechanism lays a solid foundation for enhancing the long-term consistency and reliability of SLAM systems in real-world dynamic scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and S.J.; methodology, S.J.; software, S.J.; validation, S.J.; formal analysis, S.J.; investigation, S.J.; resources, S.L.; data curation, S.J.; visualization, S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and S.J.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meixiang, Q.; Songhao, P.; Guo, L.I. An overview of visual SLAM. CAAI Trans. Intell. Syst. 2016, 11, 768–776. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dang, F.; Li, N.; Ma, K. Embodied navigation. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 141101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsintotas, K.A.; Bampis, L.; Gasteratos, A. The revisiting problem in simultaneous localization and mapping: A survey on visual loop closure detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 19929–19953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, M. 2D object recognition: A comparative analysis of SIFT, SURF and ORB feature descriptors. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 18839–18857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, S.A.K.; Raza, R.H. Potential of SIFT, SURF, KAZE, AKAZE, ORB, BRISK, AGAST, and 7 More Algorithms for Matching Extremely Variant Image Pairs. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan, 17–18 March 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shaharom, M.F.M.; Tahar, K.N. Multispectral image matching using SIFT and SURF algorithm: A review. Int. J. Geoinform. 2023, 19, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dujaili, M.J.; Ahily, H.J.S.; Fatlawi, A. Hybrid approach for optimizing the face recognition based on SIFT, SURF and HOG features. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2977, p. 020091. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Chen, K.; Lu, J. An in-depth examination of SLAM methods: Challenges, advancements, and applications in complex scenes for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 11066–11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T. Rabinovich Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelovic, R.; Gronat, P.; Torii, A.; Pajdla, T.; Sivic, J. NetVLAD: CNN architecture for weakly supervised place recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 5297–5307. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger, P.; Sarlin, P.E.; Pollefeys, M. Lightglue: Local feature matching at light speed. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 17627–17638. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Miao, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, P.C.Y.; Li, Z. Alike: Accurate and lightweight keypoint detection and descriptor extraction. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, A. Scan context: Egocentric spatial descriptor for place recognition within 3d point cloud map. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 4802–4809. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. M2DP: A novel 3D point cloud descriptor and its application in loop closure detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, J. Minkloc3d: Point cloud based large-scale place recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 1790–1799. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Ai, R.; Gu, W.; Chen, X. OverlapTransformer: An efficient and yaw-angle-invariant transformer network for LiDAR-based place recognition. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 6958–6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Liu, S.; Qiao, R.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y. Camera, LiDAR, and IMU Spatiotemporal Calibration: Methodological Review and Research Perspectives. Sensors 2025, 25, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Shang, G.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Hu, K. SLAM overview: From single sensor to heterogeneous fusion. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescos, B.; Campos, C.; Tardós, J.D.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM II: Tightly-coupled multi-object tracking and SLAM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5191–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Hong, C.; Jia, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z. DynaTM-SLAM: Fast filtering of dynamic feature points and object-based localization in dynamic indoor environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 174, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, Z. DP-SLAM: A visual SLAM with moving probability towards dynamic environments. Inf. Sci. 2021, 556, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, W.; You, H.; Jiang, S.; Meng, X.; Kim, J.; Wang, S. TS-LCD: Two-stage loop-closure detection based on heterogeneous data fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; He, Z.; Yang, Y.; Nie, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, M. Msf-slam: Multi-sensor-fusion-based simultaneous localization and mapping for complex dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19699–19713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xiao, P.; He, Y.; Shao, Z.; Li, Z. MULLS: Versatile LiDAR SLAM via multi-metric linear least square. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 11633–11640. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Du, L.; Bao, S.; Yuan, J.; Ma, S. LVIO-fusion: Tightly-coupled LiDAR-visual-inertial odometry and mapping in degenerate environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 3783–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Song, Y.; Scaramuzza, D. Actor-critic model predictive control. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 14777–14784. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yu, B.; Cao, S.-Y.; Li, J.; Shen, H.-L. BEVPlace: Learning LiDAR-based place recognition using bird’s eye view images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 8700–8709. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Yin, P.; Scherer, S. Adafusion: Visual-lidar fusion with adaptive weights for place recognition. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 12038–12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, T.; Fu, H.; Rittscher, J.; Yang, K. AdaFusion: Prompt-Guided Inference with Adaptive Fusion of Pathology Foundation Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05084. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Yang, X.; Yao, W.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Ma, B. Graph-based adaptive weighted fusion SLAM using multimodal data in complex underground spaces. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 217, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chghaf, M.; Rodríguez Flórez, S.; El Ouardi, A. Extended Study of a Multi-Modal Loop Closure Detection Framework for SLAM Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Cao, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, W. Cross fusion of point cloud and learned image for loop closure detection. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2965–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The kitti dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xie, J.; Geiger, A. Kitti-360: A novel dataset and benchmarks for urban scene understanding in 2d and 3d. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 3292–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).