Abstract

To improve power system risk prediction under complex and extreme operating conditions, a hybrid N-BEATS-based framework is proposed for equipment assessment and loss of load expectation (LOLE) forecasting. The method integrates thermal circuit modeling, online thermal parameter identification via physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), Arrhenius–Weibull temperature–failure mapping, Monte Carlo system risk evaluation, and a hybrid spatiotemporal predictor combining N-BEATS and graph neural networks. Case studies on distribution transformers demonstrate improved thermal parameter identification and reduced LOLE forecasting error compared with benchmark methods. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Firstly, it presents thermal modeling and PINN identification; Secondly, it introduces the aging-failure and reliability evaluation; Thirdly, it describes the hybrid forecasting framework; Fourthly, it reports case studies; and finally, it concludes.

1. Introduction

Under the background of global climate warming, extreme heat events have become increasingly frequent, long-lasting, and widespread, posing severe threats to the reliability of power distribution systems [1,2]. Prolonged high-temperature stress can accelerate equipment deterioration and trigger cascading failures. Recent statistics indicate that transformer insulation failures and overheated overhead line joints caused by heat waves accounted for more than 60% of temperature-induced outages in 2024 [3]. Therefore, precise risk assessment of distribution networks under extreme heat requires not only accurate estimation of equipment failure probabilities but also quantification of load loss and impact propagation [4].

Current research on equipment state assessment exhibits several key deficiencies. Firstly, most studies assume static thermal parameters disconnected from actual dynamic thermal aging characteristics. For instance, Ref. [5] employed a residual-based attention physics-informed neural network (PINN) to predict transformer aging under variable loading but still relied on constant manufacturer-rated thermal resistance and capacitance. Ref. [6] conducted a detailed 2D/3D finite element thermal analysis of oil-immersed power transformers under various operating and cooling conditions, revealing that the assumption of constant thermal parameters may lead to deviations between simulated and actual temperature distributions. In addition, Ref. [7] developed and experimentally validated a high-thermal-conductivity paper insulation to enhance the heat dissipation capability of oil-immersed transformers; however, this study still assumed constant heat transfer coefficients and ignored insulation degradation over time. Secondly, coupling between aging state and failure probability remains weak [8]. Ref. [9] applied a Bayesian model to correlated dissolved gas concentrations with transformer failure probability, yet the amplification effect of aging on thermal stress sensitivity was not captured, as even moderate temperature rises can induce failure once polymerization degradation exceeds critical thresholds.

Building on the above analysis of equipment aging, risk assessment at the equipment level must also account for the compounded effects of extreme heat and load growth. Prolonged heat waves significantly increase in power demand, even under restriction measures, as the surge in cooling loads intensifies system stress [10]. Under sustained high temperatures, cumulative thermal effects further amplify demand fluctuations and aggravate equipment loading [11]. Both the increased load and the extreme heat itself contribute to a higher incidence of equipment failures, especially within distribution networks. Refs. [12,13] showed that switches, transformers, conductors, and power electronic devices experience a markedly elevated failure risk when subjected to prolonged high temperatures and overload operation. However, conventional reliability models mainly focus on failure probabilities while oversimplifying post-failure impacts, such as load loss and cascading consequences within distribution networks.

Traditional reliability assessment methods, such as Markov models and probabilistic production simulations, depend heavily on pre-defined component failure rates and simplified load assumptions. While these approaches offer interpretability and low computational complexity, they often struggle to capture nonlinear dependencies, time-varying uncertainties, and spatial correlations that dominate modern power systems [14,15]. Deep learning methods, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, have improved the ability to capture temporal dependencies, but issues include vanishing gradients, overfitting, and generalization under nonstationary conditions [16]. In contrast, the N-BEATS architecture [17] addresses several of these shortcomings by explicitly decomposing trend and seasonal components, thereby providing interpretable outputs and state-of-the-art accuracy across diverse domains. Specifically, N-BEATS employs fully connected blocks arranged in doubly residual stacks and supports both generic and interpretable configurations, and this decomposition is particularly suitable for LOLE prediction because separating slow-evolving trends from short-term fluctuations improves the quantification of time-varying system risk under extreme conditions. However, N-BEATS is primarily designed for univariate series and therefore cannot directly capture the spatial dependencies among interconnected grid assets. To overcome this limitation, hybrid spatio-temporal architectures, such as spatio-temporal graph neural networks (ST-GNNs), have been proposed, which integrate time-series forecasting with graph-based representation of network topology and node/edge inter-relations [18,19,20,21]. Integrating N-BEATS-based temporal modeling with graph-based spatial representation thus provides a promising solution for joint prediction of component failure probability and system-level LOLE under complex, spatially correlated stressors.

In summary, prior research has developed key components for heat-driven reliability assessment, including transformer thermal modeling, parameter estimation techniques, aging laws, Monte Carlo reliability analysis, and temporal and graph-based forecasting methods. However, three limitations impede end-to-end risk quantification under extreme heat: thermal characterizations are often static or derived from offline tests and therefore do not track nonstationary loading or drifting thermal properties; the quantitative linkage from evolving equipment degradation to time-varying failure probabilities and their contribution to LOLE is typically absent; and forecasting approaches remain fragmented in space and time, with temporal models neglecting network topology and spatial models omitting decomposition-aware trends. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a coupled equipment state and failure consequence risk assessment method for distribution networks under extreme heat, integrating online thermal parameter identification, temperature-driven failure modeling, Monte Carlo-based reliability evaluation, and spatiotemporal LOLE forecasting. Building upon these components, the main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A unified end-to-end assessment framework that links transformer thermal behavior, physics-informed online parameter identification, Arrhenius–Weibull failure probability modeling, and system-level LOLE evaluation, thereby overcoming the fragmentation commonly observed between equipment degradation modeling and probabilistic reliability assessment.

- (2)

- A PINN-based equivalent thermal circuit model capable of identifying time-varying transformer thermal parameters under real operating conditions, improving robustness against non-stationary load patterns and measurement noise.

- (3)

- A temperature-driven failure probability mechanism integrated with Monte Carlo risk simulation, enabling dynamic evaluation of equipment failure likelihood and its contribution to time-varying LOLE under extreme heat scenarios.

- (4)

- A hybrid N-BEATS–STGNN spatiotemporal forecasting model, which incorporates decomposition-based trend learning, convolutional enhancement, and graph-structured spatial propagation to deliver stable medium- and long-term LOLE predictions.

The proposed approach is validated on an improved transmission distribution integrated test system, showing superior performance in state assessment accuracy, risk evaluation precision, and computational efficiency compared with traditional models.

2. Impact of Temperature Variation on Distribution Equipment

The temperature rise and heating of electrical equipment are influenced by various factors such as ambient temperature at the installation location and the magnitude of the load current. When other conditions remain constant, an increase in ambient temperature leads to a corresponding increase in the operating temperature of distribution equipment. Particularly during extreme high-temperature weather, the probability of operational failures in distribution equipment increases significantly.

2.1. Impact of Temperature Variation on Distribution Transformers

The hazards of temperature variation on distribution transformers primarily focus on three aspects: degradation of insulating material performance, rise in transformer oil temperature, and increased operational losses.

The impact of temperature change is first reflected in the performance degradation of insulating materials. The solid insulating materials inside transformers are extremely sensitive to temperature. High temperatures irreversibly accelerate the thermal decomposition of cellulose molecules, leading to a decrease in polymerization degree and loss of mechanical strength, making them prone to fracture under electromagnetic forces, resulting in insulation aging and failure. Simultaneously, the thermal aging process produces moisture and acidic substances. Moisture further reduces the electrical strength of the insulation and accelerates aging, while acidic substances corrode the materials, forming a vicious cycle of temperature increase, accelerated aging, and performance degradation, severely shortening the transformer’s lifespan.

Secondly, temperature variation directly determines the state and performance of transformer oil. In the initial stage of oil temperature rise, the viscosity of the oil decreases, enhancing its flowability and heat dissipation capability [22]. However, if the temperature remains excessively high, it will sharply accelerate the oxidative aging process of the transformer oil, reacting with oxygen and metal catalysts to generate acidic substances and sludge. Acids corrode internal transformer components and reduce the oil’s insulation strength; sludge deposits can clog oil channels, severely deteriorating heat dissipation conditions, leading to a further surge in winding hotspot temperature, which in turn exacerbates the aging of insulating materials, posing a serious threat to transformer safety [23].

From the perspective of operational losses, temperature changes disrupt the thermal equilibrium state of the transformer. The load loss of the transformer, particularly copper loss, increases significantly with rising temperature. This is because the winding resistance has a positive temperature coefficient; under the same load current, higher temperatures lead to greater resistance and thus greater generated losses. This increased loss is, in turn, converted into heat, causing a further temperature rise, forming a potentially dangerous positive feedback loop. If not controlled, thermal runaway may occur. Although the no-load loss (iron loss) is less affected by temperature, overall, continuously rising temperatures cause heat generation to exceed heat dissipation, ultimately disrupting the designed thermal balance and endangering transformer safety. Therefore, rigorous temperature monitoring is key to ensuring its stable operation.

2.2. Impact of Temperature Variation on Lines

Distribution lines mainly include overhead lines and cable lines. These two types differ in structure and operating environment, but both can experience failures due to heating during operation [24].

Under high-temperature conditions, metal connectors such as strain clamps and parallel groove clamps in distribution overhead lines are prone to overheating, thereby increasing the probability of failure. Furthermore, due to the thermal expansion and contraction effect, increased air temperature causes greater conductor sag, reducing the safety clearance to the ground or trees, which can lead to operational risks like tree contact discharge [16].

For distribution cables, high ambient temperatures hinder their normal heat dissipation, causing the cable insulation layer to expand due to heat. This increases the mechanical pressure on cable joints and may also lead to the appearance of “bamboo-shaped” deformation, further increasing the possibility of joint failure [25].

2.3. Impact of Extreme Temperatures on Load

High-temperature weather significantly leads to an increase in cooling load. Based on the analysis of actual operational data from a city’s power grid, when the daily average temperature is in the range of 24–29 °C, a 1 °C increase in temperature can lead to a growth rate of approximately 10% in the daily maximum load; when the average temperature rises to the 29–33 °C range, the load growth rate resulting from a further temperature increase gradually slows down. Overall, under extreme high-temperature conditions, the total distribution network load may climb to 1.4 to 1.8 times the conventional level.

When distribution transformers are in an overload state, the temperature of their windings, clamps, and insulation components will rise significantly, potentially causing the generation of a large number of bubbles in the transformer oil. As the load increases, the aging process of oil paper insulation materials accelerates, and the decomposed furfural compounds weaken the insulating performance of the transformer oil and enhance its conductivity, thereby shortening the practical service life of the transformer.

The distribution switchgear is prone to internal heating faults under heavy load operation, especially at the connection joints of switching equipment. A sustained high current can cause joint overheating or even damage.

For distribution overhead lines, increased load leads to higher line resistance and dielectric losses, generating more heat and causing a rise in conductor temperature. Once the maximum allowable operating temperature is exceeded, the probability of line failure increases sharply. Distribution cables, when overloaded, also experience temperature rise due to heating, accelerating the aging of insulation materials and reducing their dielectric strength, which in severe cases may cause joint breakdown. Furthermore, it is difficult to completely avoid impurities or protrusions in cable joint craftsmanship. Sustained high temperatures further accelerate overall aging, increasing the risk of insulation breakdown. On the other hand, since cables are often laid underground with poor ventilation conditions, long-term overload operation can easily lead to fire accidents [26].

3. Parameter Identification and Hotspot Temperature of Transformers

This paper is based on the full-process framework of “Equipment Temperature Rise Model: Key Thermal Parameter Identification: Arrhenius–Weibull Failure Probability Modeling: Monte Carlo System Risk Assessment: Hybrid N-BEATS Time-Series LOLE Prediction”. The modules are deeply coupled, and data flows in a closed loop, as detailed below.

3.1. Transformer Temperature Rise Model

The operating state of a transformer directly affects its key thermal parameters (, , ), leading to significant changes in its temperature rise characteristics and heat dissipation effectiveness. To accurately assess the current health state of the equipment and predict its safe overload capacity, it is essential to first obtain these parameters precisely.

Here, the thermal resistance between the winding and oil is denoted as (unit K/W), the thermal resistance between oil and ambient as (unit K/W), and the thermal capacitance of the winding as (unit J/K) and of the oil as (unit J/K). State variables include winding temperature (t) (K) and top oil temperature (K), while ambient temperature (K) and wind speed (m/s) are inputs. The corresponding energy balance equations are:

Winding Temperature Equation: The heat generated by the winding (W) equals the heat dissipated from the winding to the oil, i.e.,

where is the winding thermal capacitance (J/K), is the time-varying winding loss (W), and is the heat flow from winding to oil (W).

Oil Temperature Equation: The heat absorbed by the oil from the winding equals the heat dissipated to the environment, i.e.,

where is the oil thermal capacitance (J/K), is the heat flow from winding to oil (W), and is the heat dissipation from oil to ambient (W). Note that the thermal resistance (v) can be considered a function of wind speed v: higher wind speed increases the convective heat transfer coefficient h(v); thus, = 1/(h(v)A) decreases, where A is the heat dissipation area. Specifically, the convective heat transfer coefficient can be approximated as h(v) = + v; therefore, the unit of (v) is K/W, characterizing the variation in heat exchange performance between oil temperature and ambient temperature [7].

The above system of differential equations can be written as follows:

where all physical quantities must have clear units. The difference between K and °C is consistent, but K is more suitable for thermodynamic formulas; hence, , , and are in K; is in W; and are in K/W; and and are in J/K. The meaning of each symbol is noted in the text upon its first appearance. The above model originates from the energy conservation principle of transformer thermal dynamics. Winding loss is converted into heat energy, transferred through thermal resistance to the oil, and the oil then exchanges heat with the environment through thermal resistance . No intermediate steps are omitted in the derivation, and the physical meaning and symbols of each term are clearly defined.

In practical applications, the load current I(t) is related to the loss . Ambient temperature Ta(t) and wind speed v(t) can be measured by sensors or provided by weather models as external excitation inputs. It is noteworthy that this model is a continuous time description; for use in digital computation, its residual can be solved via automatic differentiation or finite difference methods.

3.2. Health State Identification of Transmission and Transformation Equipment

The transformer temperature rise model constructed earlier describes its thermodynamic behavior. However, the key parameters in the model (, , ) change significantly with factors reflecting the health state of the transformer, such as operating years, load history, and maintenance condition. Using factory parameters or fixed parameters cannot accurately assess the actual temperature rise situation and safety margin of the current equipment. Therefore, this project reflects changes in equipment health state through changes in these key thermal parameters. Using a physics-informed neural network (PINN), the aforementioned differential equations are embedded as physical constraints into the network training to identify the actual thermal parameters under the current state from the equipment’s actual operational data (,v,). These identified parameters are an important basis for quantifying the current health status of the equipment [27].

Based on the above differential equations, we construct a multi-input multi-output physics-informed neural network. The network input vector includes time (), ambient temperature (), wind speed v(t), and load loss , etc.; the output is the network’s predicted values for the state variables, i.e., (t) and . For example: the input dimension is four, corresponding to (t, ,v,); the output dimension is two, corresponding to (). Inputs can be added or reduced based on actual conditions, such as wind speed, which must be considered for forced air cooling.

The PINN uses a fully connected feed-forward neural network. As an example, we employ an architecture with a four-node input layer, three hidden layers of 50 neurons each (expandable if required), and a two-node linear output layer. The output layer uses linear activation to predict temperature values. The hyperbolic tangent function (tanh) is chosen as the activation function due to its smoothness and non-zero higher-order derivatives, making it suitable for training networks with physical constraints.

Research shows that using smooth activations (like tanh) in PINNs is superior to piecewise linear activations like ReLU, as the latter have zero higher-order derivatives and cannot effectively penalize differential equation residual terms. The linear transformations of each network layer are defined by weight matrices W and biases b. The neural network function can be represented as , where θ is the set of network parameters (weights and biases), and x is the input vector.

The network output is the predicted value of oil temperature and winding temperature. Simultaneously, we treat the physical parameters to be identified, , as learnable parameters during training, updated together with the network weights. This approach allows the network to invert the physical parameters while fitting the temperature time series. In summary, the PINN model integrates inputs, outputs, and system physical parameters, ensuring the expressive capability for temperature rise dynamics and the differentiability of the differential equation residual through the deep network structure and tanh activation.

In the PINN, the total loss function L consists of two parts: one is the data error term , and the other is the physical constraint residual term Specifically, for network predictions , and the corresponding measured data at time points, the data term can be defined as the mean squared error:

where is the time sequence of training samples, and N is the number of samples. If only oil temperature or winding temperature is measured, only the corresponding term can be included. If initial conditions (,) are known, they can be included as weighted error terms in or listed separately as a condition term to ensure the network satisfies the initial values.

The physical constraint term utilizes the differential equation residual: automatic differentiation is used to compute the time derivatives of the network outputs , which are substituted into the model equations to obtain the residual functions. The residuals are defined as:

Ideally, the above residuals and should be zero. Thus, the physics loss term is defined as their mean square sum:

where is the set of points used to compute the residual (which can coincide with the data points or include additional arbitrary time points within the domain, with a total number M). The PINN loss function includes the physical conservation term and initial/boundary condition terms , etc., optionally adding an additional observation data term . This section combines the above two parts to construct a joint loss:

where λ is a weighting coefficient used to balance the influence of data fitting and physical consistency, adjustable through cross-validation or physical priors. During training, optimization algorithms like gradient descent are used to minimize L simultaneously, and automatic differentiation ensures accurate derivative calculation. This designed loss function both drives the network to fit the actually measured temperature curves and forces the network solution to satisfy the given differential equation constraints [28].

The PINN training for transformer thermal parameter identification follows a workflow consistent with the original framework: First, data are derived from the transformer’s actual operational data, with 10,000 time-series samples covering 30 operating days. These samples are cleaned and normalized to the range [0, 1] using min-max scaling to eliminate scale differences between heterogeneous channels. Next, network initialization adopts a fully connected feed-forward structure as specified; weights of fully connected layers are initialized via He initialization, biases set to 0, initial values of thermal parameters ϕ based on the transformer’s factory-rated parameters, and sinusoidal positional encoding added to the time input to introduce temporal order information, with the hyperbolic tangent function used as the hidden layer activation. A two-stage training strategy is implemented: Stage 1 sets the weighting coefficient λ of the physical constraint term to 0.1, prioritizing fitting the measured temperature data, and Stage 2 linearly increases λ to 1.0 to strengthen enforcement of the thermal dynamic differential equations. Training stops when two conditions are met: the validation loss does not decrease by more than for 20 consecutive epochs, and the relative change in ϕ between consecutive epochs is less than 0.1%.

3.3. Calculation of Hotspot Temperature

Given the identified parameters , , and , the state equation for the average winding temperature of the transformer at time period t is as follows:

where is the equivalent thermal capacitance composed of the internal insulating oil, windings, tank, etc.; is the equivalent thermal resistance on the insulating oil side, calculated as , where is the thermal resistance corresponding to the mixing of insulating oil at different temperatures under conventional forced oil circulation methods; and under forced oil circulation directed cooling, cold oil at the pump outlet is sent into the oil ducts of coils, discs, and the core under certain pressure, making the internal oil temperature distribution more uniform, and thus is approximately considered 0. is the no-load loss, is the load coefficient at time period t, and is the short-circuit loss.

After simplification, the calculation formula for the average winding temperature is obtained:

where the calculation formula for D is:

where is the equivalent thermal capacitance composed of the internal insulating oil, windings, tank, etc.; is the equivalent thermal resistance on the insulating oil side, calculated as , where is the thermal resistance corresponding to the mixing of insulating oil at different temperatures under conventional forced oil circulation methods; and under forced oil circulation-directed cooling, is approximately considered 0. is the no-load loss, is the load coefficient at time period t, and is the short-circuit loss.

The winding hotspot temperature of the transformer at time period t can be represented by an approximate formula composed of the transformer average winding temperature , the transformer tank top-oil temperature , and the transformer tank bottom-oil temperature :

where H is the temperature coefficient for the winding hotspot temperature, taken as 1.3.

4. Loss of Load Expectation Budget

4.1. Failure Probability Modeling Based on Arrhenius–Weibull

The transformer winding hotspot temperature can be calculated using the above formulas. The aging process of transformers is commonly described using the Weibull distribution. By incorporating temperature effects into this distribution, the Arrhenius–Weibull model for long-term transformer failure is derived. Its failure rate is expressed as follows [29]:

where is the transformer failure rate; is the transformer reference temperature (for 220 kV transformers, the winding heat resistance class is mostly Class B, taken as 130 °C); is an empirical parameter, taken as 15,000; and parameters and β are estimated using the least squares method or maximum likelihood estimation. The increase in winding hotspot temperature and load rate leads to an increased failure probability of the distribution transformer.

The transformer aging failure model calculates the probability of failure occurring within the subsequent time interval ∆t after the transformer has served for time T. Introducing the concept of “equivalent operating time”, and based on the definition of conditional probability, the probability of aging failure occurring within the subsequent time interval ∆t after the transformer has served for T events is derived as follows:

where FT(t) is the transformer failure probability, and is the equivalent operating time of the transformer at the reference temperature, as shown in the following.

where is the actual operating time interval, and is the transformer hotspot temperature during the corresponding time.

is the equivalent operating time of the subsequent operating time converted to the reference temperature, also calculated according to Equation (14).

We fit the probability density of distribution line operating temperatures using a kernel density estimator. Assuming that during extreme high-temperature full-load operation there is a 5% probability (a conservative value greater than 0.2%) that the conductor temperature exceeds the normal operating temperature limit, the distribution line failure rate is given as follows [30]:

where is the distribution line failure rate; is the allowable operating temperature limit for the distribution line; and C is the failure rate when the distribution line operating temperature is below the allowable limit, taken as 0.01%.

4.2. Distribution Network Risk Assessment

Monte Carlo simulation typically uses hours as the time step. For each time step, the procedure is as follows.

Based on the previous failure model, first calculate the instantaneous failure rate (t) for various types of equipment at that moment, thereby obtaining the failure probability within that period. Then, generate a uniformly distributed random number ξ for each equipment. The judgment method is as follows:

where is the fault state of the distribution equipment at time t. When Fp(t) is greater than the random number ξ, the equipment is considered to be in a fault state; otherwise, it is in a normal state.

In a sampled scenario where a piece of equipment fails, the system operating state is adjusted as follows.

If a line or transformer is out of service, the system topology changes accordingly. Considering load transfer within the system, under the new topology, power flow calculation is performed again to determine the voltage and power distribution at each node. Then, constraint checking is performed: check if all node voltages are within limits; if limits are exceeded, the load at that point needs to be shed. Simultaneously, check if the power flow on each branch is less than the thermal stability limit; if limits are exceeded, gradually shed the load according to a set priority until the power flow returns to a safe range. Finally, check if the transformer power exceeds the rated capacity. If exceeded, adjust by reducing the load on the connected busbars.

Finally, the simulation computes the energy not served (ENS) for the scenario. If a node is fully disconnected, its demand is counted as ENS; partial shedding due to constraint violations is accumulated accordingly. Summing ENS across time steps yields the scenario’s total unserved energy.

Within one complete simulation cycle, the loss-of-supply curve for each time step is obtained. After N independent samples, the loss of load expectation curve is statistically obtained. The LOLE at each time point is as follows:

where LOLE is the loss of load expectation, and L(s) is the loss of load amount in the sth sample.

The risk assessment process consists of the following sequential steps:

Step 1: Initialization.

The procedure begins with the initialization of model inputs, including system topology, load profiles, N–1 contingency conditions, and the initial simulation time step.

Step 2: Computation of Equipment Failure Probability.

For each simulation time step, the failure probability of each component is evaluated based on the prescribed thermal model and associated operating conditions.

Step 3: Equipment State Sampling and Power Flow Evaluation.

Component states are sampled according to their respective failure probabilities, and a corresponding power flow calculation is performed to determine the system operating state under the sampled configuration.

Step 4: Assessment of Fault Occurrence.

If a component failure is identified, the simulation enters the fault-handling subroutine, which models the repair or removal process. If no failure is detected, the system proceeds directly to the normal operation assessment.

Step 5: Operational State Update.

For both faulted and non-faulted scenarios, the system power flow is recalculated to determine the resulting load supply capability. The simulation time step is then advanced by one increment.

Step 6: Iteration Over Simulation Horizon.

Steps 2–5 are repeated until all time steps in the simulation horizon have been evaluated.

Step 7: Risk Quantification.

Upon completion of all iterations, LOLE are computed based on the accumulated results.

Step 8: Termination.

The procedure concludes when all risk metrics have been obtained.

4.3. Hybrid N-BEATS Time-Series LOLE Prediction

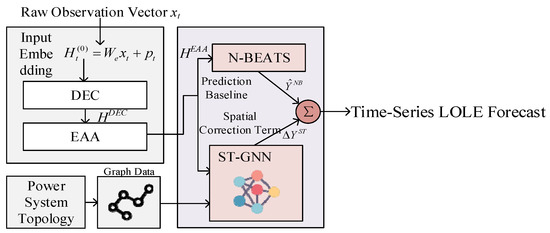

The module is constructed following a design philosophy of “from local to global, from temporal to spatial”, comprising five main parts: input embedding, Detail-Enhanced Convolution (DEC), Efficient Additive Attention (EAA), N-BEATS component decomposition backbone, and spatio-temporal graph neural network (ST-GNN). The model begins with a unified embedding that serves as the common representation for subsequent modules. DEC extracts multi-scale local features and delivers them to EAA for dynamic weighting; the weighted output of EAA serves both as high-quality temporal input for N-BEATS to build the weekly-scale prediction skeleton, and can be supplied to ST-GNN at the node level. ST-GNN then generates a spatial correction term based on the grid adjacency relationships, and finally, the fusion layer integrates them into point estimates and quantile forecasts.

For precise formulation, let the original observation vector at time t be (containing ambient temperature, total load, oil temperature, winding temperature, load rate, line temperature, etc.). The model first maps heterogeneous channels to a latent representation space via linear projection and positional encoding, as shown in Equation (18). This embedding eliminates channel-scale differences and provides a consistent feature base for subsequent modules; the embedding output serves as the input to DEC and is also projected as node features for ST-GNN when necessary to preserve spatial semantics.

where is the input embedding matrix, used to project original features to the latent space dimension dh; is the positional encoding vector, used to introduce temporal order information; and is the input embedded representation, serving as the unified feature base for subsequent modules.

The DEC module is designed to capture high-resolution details of short-term non-stationary events (e.g., instantaneous overloads, sudden temperature spikes). To this end, DEC uses parallel multi-scale 1D dilated convolutions to obtain local responses with different receptive fields and integrates the multi-scale outputs with learnable scale fusion weights, thus forming a local representation rich in details in the time domain, as shown in Equation (19). The output HDEC of DEC plays a dual role in the information flow: on one hand, it serves as the key/value for EAA, used for time-variable level attention weighting; on the other hand, it can be mapped as node-level input for ST-GNN, allowing the spatial propagation path of local impacts to be explicitly encoded into the spatio-temporal module.

where is the 1D dilated convolution operator with kernel size and dilation rate ; is the output of the ℓ-th convolution branch, capturing local temporal features at the corresponding scale; is the nonlinear activation function (ReLU is used in this paper); is the learnable scale fusion weight, satisfying ; and is the fused output of the DEC module, containing multi-scale short-term detail features.

Building on DEC, the EAA module employs an additive attention form to perform multi-level weighting on local temporal features, dynamically identifying the time windows and input channels most relevant to future LOLE changes. Additive attention is more numerically stable under low-rank mapping and facilitates the introduction of lightweight learnable projections, thereby improving importance discrimination ability while ensuring computational efficiency. The EAA output increases the input signal-to-noise ratio for N-BEATS, which facilitates robust decomposition of medium- and weekly-scale components and simultaneously produces weighted node features that serve as inputs to the ST-GNN, as shown in Equation (20). Through this design, the temporal importance of local details is effectively amplified and transmitted to downstream prediction modules.

where are the hidden vector representations from the DEC module at times u, t; are projection matrices used to map inputs to the attention space; is the bias term; is the attention score vector; is the unnormalized attention energy, characterizing the correlation between u and t; and is the normalized attention weight, representing the contribution degree of time t to time u. denotes the output vector at time t, and . γ is the residual coefficient used to retain the original local features in the output.

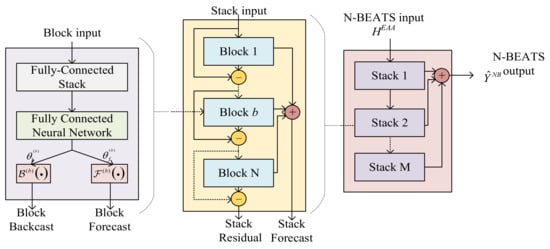

N-BEATS is used as the temporal prediction backbone of the model. Its advantage lies in explicitly fitting components such as trend and seasonality through serialized blocks to obtain a highly interpretable medium-term baseline forecast. Each block of N-BEATS produces a backcast and a forecast, iteratively approximating the residual, thereby decomposing the weighted representation provided by EAA into several interpretable components and summing them into the final baseline forecast . The structure of N-BEATS is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

N-BEATS structure.

In the model proposed in this paper, the N-BEATS output not only serves as part of the final prediction, but its residual information can also guide ST-GNN to focus on nodes and links in the spatial dimension that may cause prediction deviations, as shown in the following.

where , are the outputs of the fully connected neural network in each N-BEATS block; is the backcast function of the b-th N-BEATS block, used to fit and remove the residual; and is the residual component of the b-th block. is the forecast function of the b-th block, used to generate the component forecast; is the forecast component (trend/seasonal, etc.) of the b-th block; and is the aggregated prediction result of N-BEATS.

ST-GNN takes the grid’s adjacency matrix A as a structural prior, aggregates direct and indirect influences between nodes through graph convolution, and is supplemented by a temporal update unit to capture the time-varying propagation process. The node-level output of ST-GNN is aggregated as a spatial correction term and fed back to the fusion layer to correct the baseline prediction of N-BEATS, thereby achieving spatio-temporal synergy, as shown in Equation (22). In practice, the adjacency matrix can be based on physical connectivity or learned from historical correlations to adapt to data-driven scenarios.

The proposed DEC-EAA-NBEATS-STGNN hybrid time-series prediction model architecture is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Proposed hybrid prediction model framework.

The final fusion module synthesizes the baseline forecast and the spatial correction term in an element-wise manner through a learnable fusion layer, generating a unified deterministic estimate of the system reliability index. The model training objective is to minimize the mean squared error between the predicted and actual values, ensuring stable convergence and accurate representation of temporal–spatial reliability patterns. The corresponding loss function is defined in Equations (25) and (26). In summary, the DEC component enhances the extraction of short-term temporal details, the EAA module achieves adaptive weighting across multi-scale temporal features, the N-BEATS backbone constructs an interpretable medium-term trend representation, and the ST-GNN branch provides fine-grained spatial corrections based on network topology. These components are jointly optimized through coherent information flow, effectively balancing prediction accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency for practical deployment.

where denotes the true target value at time ; represents the model’s deterministic forecast; is the prediction horizon; is the mean squared error over the horizon; and denotes the total loss function used for training, computed as the expectation of across all samples and prediction intervals.

5. Case Study

5.1. Validation of Proposed PINN-Based Transformer Thermal Parameter Identification Method

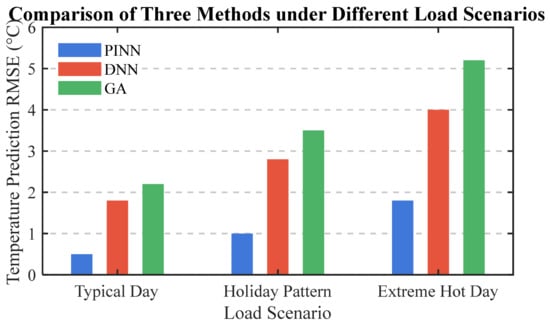

Now, we validate the proposed PINN-based transformer thermal parameter identification method. Two benchmark algorithms, namely the Deep Neural Network (DNN) and Genetic Algorithm (GA), are introduced for comparison. The proposed method and the benchmark models are evaluated under three load scenarios: Typical Day, Holiday Pattern, and Extreme Hot Day. The test results are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of temperature prediction RMSE among PINN, DNN, and GA methods under three representative power load scenarios.

As shown in Figure 4, the proposed PINN method achieves the lowest RMSE across all three representative operating conditions, demonstrating superior temperature prediction accuracy and generalization capability. In contrast, the DNN exhibits moderate accuracy with noticeable error growth under stress conditions such as the Extreme Hot Day scenario. The meta-heuristic GA-based approach shows the poorest performance, particularly when the system undergoes significant thermal or load fluctuations, reflecting its limited adaptability to nonlinear spatiotemporal dynamics.

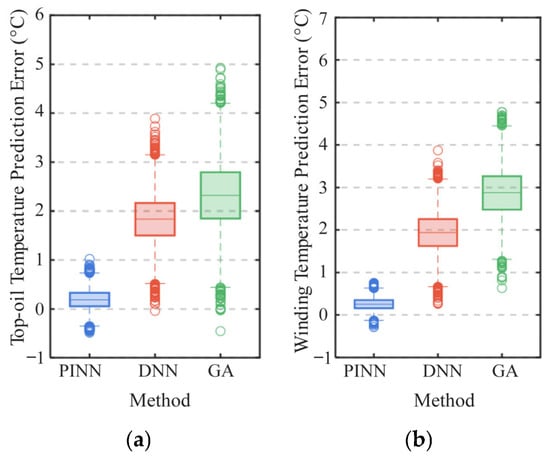

Figure 4.

Distribution of temperature prediction errors for different methods in online operation: (a) top-oil temperature and (b) winding temperature.

These results highlight that incorporating physical constraints into neural network structures (as in the PINN) effectively mitigates overfitting and enhances model robustness when extrapolating to unseen operating regimes. The increasing RMSE trend from the Typical Day to Extreme Hot Day scenarios further indicates that temperature prediction becomes more challenging under high thermal stress, where system losses, environmental uncertainties, and nonlinear coupling effects intensify. Overall, the experimental findings validate the effectiveness of PINN-based approaches for accurate and stable temperature field prediction in power industry applications.

Figure 4 shown the comparative distributions of temperature prediction errors obtained in the online stage for both (a) top-oil temperature and (b) winding temperature. Three representative algorithms are evaluated under the same 48-step online update scenario.

As shown in Figure 4a, the PINN exhibits a remarkably compact error distribution, with most samples concentrated within ±0.5 °C and a mean bias below 0.3 °C, demonstrating its superior generalization ability and effective incorporation of thermodynamic constraints. In contrast, the DNN yields a broader distribution with a higher median error (~1.8 °C), while the GA-based model presents the largest dispersion and mean deviation exceeding 2.5 °C, indicating limited adaptability to real-time variations. A consistent pattern is observed in the winding temperature results (Figure 4b), where the PINN maintains the lowest variance and bias. This stability highlights its robustness to parameter drift and measurement noise, owing to the embedded physical priors that guide model updates within feasible thermal boundaries. Overall, the PINN achieves the most accurate and stable temperature predictions during online learning, outperforming purely data-driven and heuristic models by a significant margin.

5.2. Validation of Proposed Hybrid N-BEATS-Based LOLE Predict Model

Based on the parameter identification in the previous section, a two-layer distribution network topology system conforming to the actual operation characteristics of urban power grids is constructed. Four 220 kV substations are connected in a ring network, and each substation is equipped with two differentiated main transformers with a capacity of 180 MVA each to highlight the difference in equipment age. Each 220 kV substation radiates three 110 kV substations. The transformer and transmission line failure probabilities are calculated through the models described in Section 3 and Section 4, and then the expected LOLE is calculated to provide verification data for the overall example.

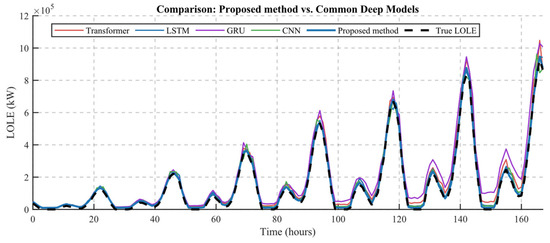

Now we validate the proposed hybrid forecasting framework, DEC–EAA–N-BEATS–STGNN, on a representative LOLE forecasting task. The model is trained on 5000 synthetic cases and evaluated on a held-out test set of 500 cases (training/test = 1:9). Evaluation employs four standard metrics: MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE. Visual inspection uses single-sample fits to illustrate temporal alignment and transient response; quantitative claims are based on averages across the 500 test cases.

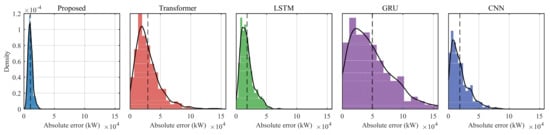

First, we include four baseline algorithms for comparison with the proposed method. The baseline models are configured following widely used settings in time-series forecasting, where the Transformer employs a four-layer encoder with eight-head self-attention and a model dimension of 256, the LSTM consists of two stacked recurrent layers with 128 hidden units followed by a fully connected projection layer, the GRU adopts the same two-layer recurrent structure with 128 hidden units, and the CNN is implemented as a temporal convolutional network comprising four sequential 1-D convolutional blocks with kernel sizes of three, five, seven, and nine and 128 feature channels in each block. Figure 5 presents side-by-side absolute error distributions for the proposed method, Transformer, LSTM, GRU, and CNN constructed from 500 independent test realizations. The proposed method yields the most concentrated distribution with the lowest mean absolute error and the shortest tail, indicating reduced bias and variance in both routine and high-volatility intervals. Transformer and CNN exhibit moderate dispersion, while LSTM attains intermediate performance; GRU shows a pronounced heavy tail and the largest variance, which is consistent with its higher RMSE. These distributional results corroborate the aggregated numerical comparisons and emphasize the proposed method’s improved robustness against extreme prediction deviations.

Figure 5.

Absolute-error distributions of the proposed method and four baseline models (Transformer, LSTM, GRU, CNN) computed over 500 held-out test cases.

The comparison results for Scenario 1 are shown in Figure 6. Table 1 reports averaged metrics over the 500 test cases. The proposed method achieves the lowest bias and dispersion (MAE = 10,617 MW, RMSE = 11,284 MW, MAPE = 1.23%). Against the best baseline (Transformer, RMSE = 35,658 MW), the proposed method reduces RMSE by 68.4%, demonstrating substantially lower cumulative error and drift. Compared with LSTM and CNN, the proposed method reduces RMSE by 46.2% and 53.0%, respectively. GRU exhibits the largest residual errors (RMSE = 61,920 MW), indicating weaker stability for this task. These averaged results indicate that the multi-module coupling, combining decomposition, event-aware attention, a powerful temporal backbone, and spatial graph learning, yields systematic improvements in both absolute error and error variability.

Figure 6.

Comparison with conventional deep learning models.

Table 1.

Comparison with common deep models (averaged over 500 test cases).

The proposed method demonstrates superior robustness in high-volatility segments and maintains lower variance across the 500 realizations. The proposed method consistently outperforms standard sequence and convolutional baselines in both absolute and relative terms; the observed RMSE reductions (≈68% vs. Transformer, ≈46% vs. LSTM, ≈53% vs. CNN) indicate substantial practical gains for LOLE forecasting under the examined data regime.

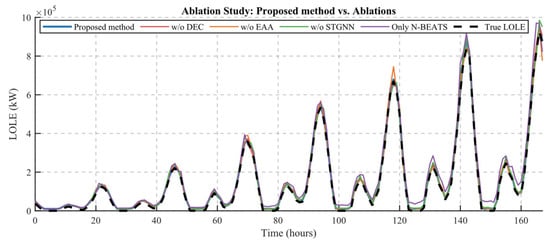

Subsequently, to verify the effectiveness of each component in the proposed prediction model, an ablation study was conducted. We sequentially removed individual components from the model and performed corresponding tests. Figure 7 presents the prediction results of different models under Scenario 1 in the ablation study, while Table 2 summarizes the evaluation metrics across 500 test samples.

Figure 7.

Ablation study.

Table 2.

Ablation study (averaged over 500 test cases).

As shown in Table 2, removing DEC yields a measurable performance loss (MAE increases from 10,617 MW to 12,227 MW; RMSE increases by 17.2%), indicating that the decoupled embedding calibration improves short-term fluctuation capture. Excluding EAA leads to larger degradation (MAE = 13,908 MW; RMSE increase ≈ 36.6%), showing that adaptive, event-aware attention mitigates phase and bias errors during transient ramps. Omitting STGNN produces a further accuracy drop (MAE = 16,170 MW; RMSE increase ≈ 43.9%), which demonstrates the necessity of spatiotemporal graph modeling to represent error propagation across regions. When the architecture reduces to the temporal-only backbone (Only N-BEATS), both bias and dispersion increase substantially (MAE = 29,511 MW; RMSE = 36,365 MW; MAPE = 3.42%), confirming that the integrated spatial and attention modules are essential for stable LOLE forecasting.

The observed increases in MAE and RMSE quantify each module’s contribution: DEC refines short-term dynamics, EAA mitigates transient misalignment, and ST-GNN enforces spatial consistency. The large error increase for the temporal-only N-BEATS baseline indicates that decomposition, event awareness, and spatial coupling are critical for reliable LOLE forecasting. The ablation results confirm that the full DEC-EAA-N-BEATS-STGNN coupling yields synergistic gains; each module supplies distinct, complementary capabilities that together secure lower bias and variance.

Across qualitative (single-sample fits) and quantitative (averaged metrics over 500 test cases) evaluations, the proposed hybrid architecture delivers marked improvements in LOLE forecasting accuracy and stability. The training regime (5000 training cases, 500 test cases) and consistent metric reporting (MAE, MAPE_eps, MSE, RMSE) substantiate that the observed gains are systematic and reproducible. For reporting, emphasize RMSE and MAE for absolute-performance claims and use the epsilon-stabilized MAPE only as a supplementary percentage metric due to LOLE’s near-zero intervals. If required by reviewers, include a short appendix documenting the MAPE epsilon choice and provide distributional statistics of the LOLE series.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a hybrid N-BEATS-based integrated framework for equipment assessment and system risk prediction in urban power grids under extreme heat. The framework exhibits significant advantages in both equipment-level and system-level tasks: for transformer thermal parameter identification, the PINN embedded with thermodynamic constraints outperforms DNN and GA benchmarks—as shown in Figure 3, it achieves the lowest RMSE in temperature prediction; Figure 4 further verifies its online operational stability, with a top-oil temperature prediction bias of less than 0.3 °C and a more concentrated error distribution than DNN and GA, confirming that integrating physical priors can effectively mitigate over-fitting and enhance generalization. For system-level LOLE prediction, the hybrid N-BEATS-based method demonstrates significantly higher accuracy than traditional deep learning models—Table 1 shows it has the lowest MAPE, which is 1.23%. Ablation experiments (Figure 7 and Table 2) further confirm the synergy of each module, verifying the necessity of spatial correlation modeling for power grid risk prediction. In addition, unlike traditional methods that separate equipment aging analysis from system risk assessment, this framework unifies temperature rise modeling, Arrhenius–Weibull failure probability mapping, Monte Carlo risk simulation, and hybrid time-series forecasting, establishing a direct link between equipment health status and system load loss to improve the interpretability of risk prediction results.

Despite these advantages, the framework still has limitations in practical application; for example, the current ST-GNN has high computational complexity, making it difficult to efficiently handle large-scale urban power grids with hundreds of nodes. The failure probability model only incorporates temperature, ignoring other extreme environmental factors that affect equipment aging. Future research will optimize the ST-GNN with lightweight graph structures and distributed computing to improve adaptability to large-scale grids; extend the Arrhenius–Weibull model to include humidity and solar radiation to build a multi-dimensional environmental stress index; and integrate the coupling of electric vehicles and energy storage systems to analyze the impact of multi-energy load fluctuations on equipment aging, thereby updating the LOLE calculation model to enhance practical value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F. and G.C.; methodology, C.F.; software, P.S.; validation, C.F., G.C. and P.S.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, J.B. and S.L.; resources, B.C.; data curation, W.W. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C., W.W. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.G. and Y.S.; visualization, C.F. and P.S.; supervision, C.F.; project administration, C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China (52199723992U).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Chengwei Fan, Gang Chen, Peng Shi, Shudi Liu, Jiayu Bai, Baorui Chen, Wanlin Wang and Yan Li were employed by the company State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| the thermal resistance between the winding and oil | |

| the thermal resistance between oil and ambient | |

| the thermal capacitance of the winding | |

| the thermal capacitance of the oil | |

| the winding temperature | |

| top-oil temperature | |

| ambient temperature | |

| ambient temperature | |

| wind speed | |

| winding loss | |

| h(v) | higher wind speed increases the convective heat transfer coefficient |

| time | |

| top-oil temperature in prediction | |

| winding temperature in prediction | |

| time sequence of training samples | |

| N | number of samples |

| equivalent thermal resistance on the insulating oil side | |

| the thermal resistance corresponding to the mixing of insulating oil | |

| no-load loss | |

| the load coefficient at time period t | |

| the short-circuit loss | |

| the equivalent thermal capacitance composed of the internal insulating oil, windings, tank, etc. | |

| the winding hotspot temperature | |

| the transformer tank bottom-oil temperature | |

| the temperature coefficient for the winding hotspot temperature | |

| the transformer failure rate | |

| the transformer reference temperature | |

| the transformer failure probability | |

| the equivalent operating time of the transformer at the reference temperature | |

| the distribution line failure rate | |

| the allowable operating temperature limit for the distribution line | |

| the failure rate when the distribution line operating temperature is below the allowable limit | |

| instantaneous failure rate | |

| the loss of load amount in the sth sample | |

| the fault state of the distribution equipment at time t | |

| the learnable scale fusion weight | |

| the fused output of the DEC module | |

| , the hidden vector representation from the DEC module at time u | |

| , the hidden vector representation from the DEC module at time t | |

| , the attention score vector | |

| the unnormalized attention energy | |

| the output vector at time t, and | |

| the final baseline forecast | |

| the output of the fully connected neural network in each N-BEATS block | |

| the output of the fully connected neural network in each N-BEATS block | |

| the residual component of the b-th block | |

| the forecast component (trend/seasonal, etc.) of the b-th block | |

| the aggregated prediction result of N-BEATS | |

| the embedding of node at the forecasting step | |

| the model’s deterministic forecast | |

| the total loss function used for training |

References

- Lee, S.H.; Kang, J.E.; Park, C.S.; Yoon, D.K.; Yoon, S. Multi-risk assessment of heat waves under intensifying climate change using Bayesian networks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilyaz, S.; Bhati, A.; Hamalian, M.; Maynor, K.; Soori, T.; Gattozzi, A.; Bahadur, V. Modeling the impact of high thermal conductivity paper on the performance and life of power transformers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, A.; Chicco, G.; Borges, C.L.T. Investigation on the Impact of Heat Waves on Distribution System Failures. In Proceedings of the 2024 22nd Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON), Porto, Portugal, 25–27 June 2024; pp. 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tari, A.N.; Sepasian, M.S.; Kenari, M.T. Resilience assessment improvement of distribution networks against extreme weather events. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 125, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, I.; Pino, J.; Pardo, D.; Sanz, M.; Del Río, L.; Ortiz, A.; Aizpurua, J.I. Residual-based attention in physics-informed neural networks for spatio-temporal ageing assessment of transformers operated in renewable power plants. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddik, M.S.; Shazly, J.; Eteiba, M.B. Thermal analysis of power transformer using 2D and 3D finite element method. Energies 2024, 17, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.F.; Medeiros, L.H.; Oliveira, M.M.; Nogueira, G.C.; Bender, V.C.; Marchesan, T.B.; Marin, M.A. Evaluation of power transformer thermal performance and optical sensor positioning using CFD simulations and temperature rise test. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 7002511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Xue, Z.; Quan, J.; Mao, W.; Xu, L. Distribution Network Resilience Assessment Considering the Orderly Power Consumption Scheme Under Extreme Heat Wave Weather. In Proceedings of the 2023 Panda Forum on Power and Energy (PandaFPE), Chengdu, China, 27–29 October 2023; pp. 2119–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Dong, M.; Wu, Z. Fault diagnosis of power transformers based on comprehensive machine learning of dissolved gas analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 20th International Conference on Dielectric Liquids (ICDL), Roma, Italy, 23–27 June 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Guo, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; He, S. Power supply challenges and prospects in new power system from Sichuan electricity curtailment events caused by high-temperature drought weather. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 4517–4538. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, Z.; Jiangang, Y.; Wei, L. Analysis model and processing approach for thermal cumulative effect of temperature in load forecasting. Power Syst. Technol. 2008, 32, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, J.; Yu, J.; Long, X.; Diao, Y.; Wang, J. Adaptive overload protection method considering the dynamic thermal characteristics of a transmission line. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2022, 50, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. Transformer Overload Capacity Optimization and Operation Risk Assessment Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Shi, K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, X. A novel temporal-spatial graph neural network for wind power forecasting considering blockage effects. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjie, W.; Qiang, L. Self-supervised dynamic stochastic graph network for spatio-temporal wind speed forecasting. Energy 2024, 304, 132056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, P.; Djurović, I.; Ćalasan, M.; Kovačević, S.; Pavlović, K. Electrical energy load forecasting using a hybrid N-BEATS-CNN approach: Case study Montenegro. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 247, 111749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Xu, F.; Wang, F.; Mi, Z. Spatio-temporal graph neural network and pattern prediction based ultra-short-term power forecasting of wind farm cluster. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ni, R. Power system transient stability assessment based on spatio-temporal broad learning system. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 10343–10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Shen, B.; Wang, T.; Cheng, M. Transient stability assessment in power systems: A spatiotemporal graph convolutional network approach with graph simplification. Energies 2024, 17, 5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, S.; Zheng, J. DEST-GNN: A double-explored spatio-temporal graph neural network for multi-site intra-hour PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, S.; Jiang, T.; Li, M.; Xu, Q. Localization of dummy data injection attacks in power systems considering incomplete topological information: A spatio-temporal graph wavelet convolutional neural network approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusner, P.; Schwaiger, E.; Potthast, A.; Rosenau, T. Thermal stability of cellulose insulation in electrical power transformers–A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Sun, W.; Gao, S.; Hao, J. Thermal aging test for transformer oil–paper insulation under over-load condition temperature. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 2846–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Keji, C.; Jian, Z.; Jiajun, S. Calculation and Analysis of Transmission Line Sag Based on Theoretical Mechanics. In Proceedings of the 2024 Asia-Pacific Conference on Software Engineering, Social Network Analysis and Intelligent Computing, New Delhi, India, 10–12 January 2024; pp. 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Rehman, S.U.; Ali, R.; Raza, S.A. Advancement and challenges: A review of power cable aging monitoring and diagnostic techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 222, 115970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhang, L.; Ren, G.; Zhang, R. Impacts of UHI on variations in cooling loads in buildings during heatwaves: A case study of Beijing and Tianjin, China. Energy 2023, 273, 127189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, S.J.; Toscano, J.D.; Stergiopulos, N.; Karniadakis, G.E. Residual-based attention in physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 421, 116805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Risk assessment methods for distribution networks in extremely hot weather. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 51, 5042–5052. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.; He, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Research on resilient distribution network reconstruction based on robust optimization. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2024, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).