Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention of Complex Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Generalized Petri Nets

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Multisets

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ;

- .

Example of Applications

1.2. Aim of the Paper

1.3. Structure of the Article

2. Basics of Petri Nets

3. Siphon Controllability Conditions and Constraints

3.1. Systems of Simple Sequential Processes with Resources (PRs)

- 1.

- is called the process idle place of . Places from sets and are called operation and resource places, respectively.

- 2.

- (a) ;(b) ;(c) The two following statements are verified: (i) and (ii) ;(d) .

- 3.

- .

- 4.

- is a strongly connected state machine, where is the resultant net after the places in and related arcs are removed from .

- 5.

- Every circuit of contains place .

- 6.

- Any two s are composed when they are composables. Every shared place must be a resource.

3.1.1. Controllability of Elementary Siphons

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- If S is never empty, then .

- 4.

- .

- and are the supports of P-invariants of the PR;

- Let be a strict minimal siphon in N, where . Then, and ;

- Given a strict minimal siphon S in N, is the support of a P-invariant of N.

3.1.2. Controllability for Strongly Dependent Siphons

3.1.3. Controllability for Weakly Dependent Siphons

3.2. Controllability of Siphons in GPN Models of AMSs

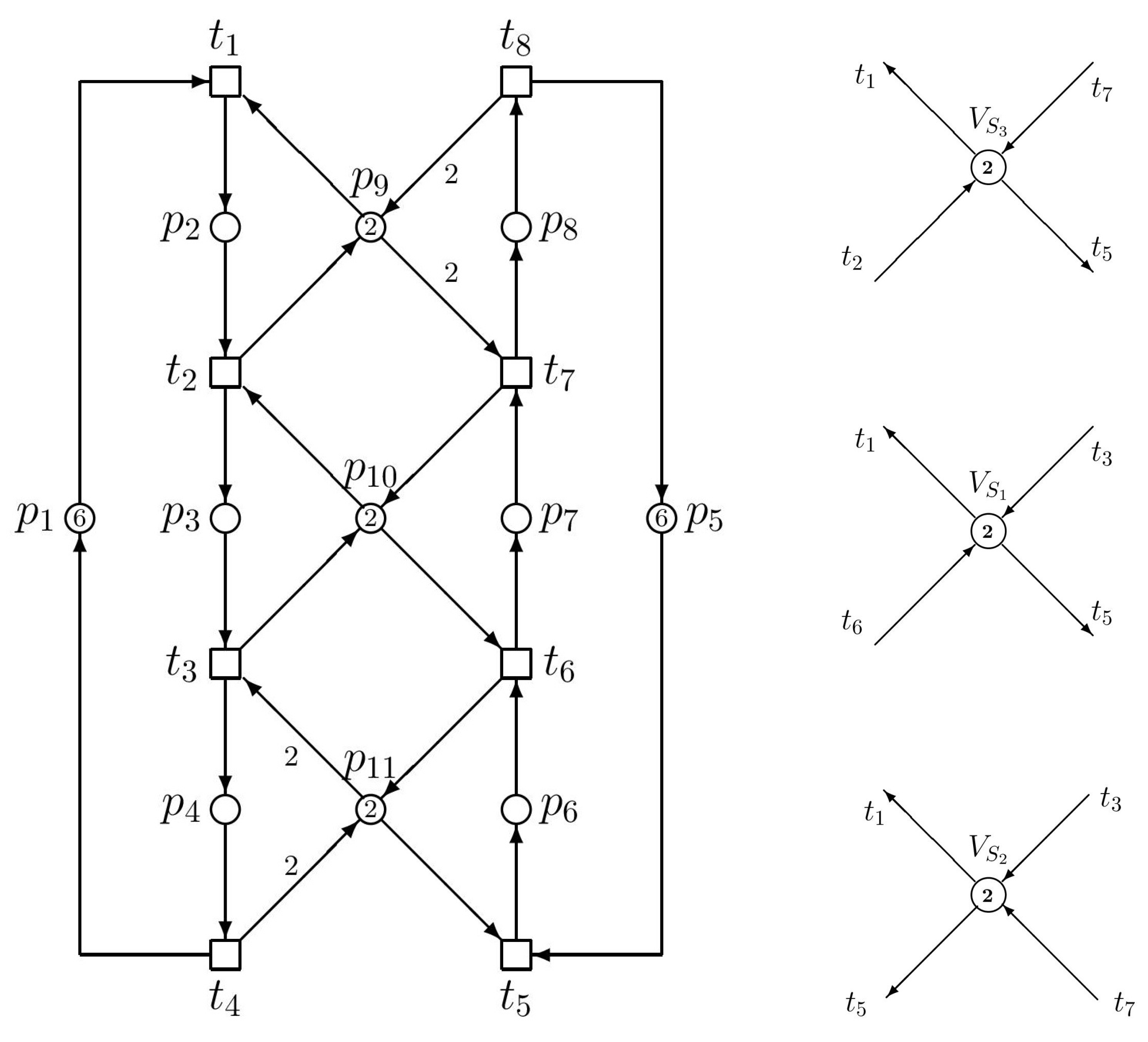

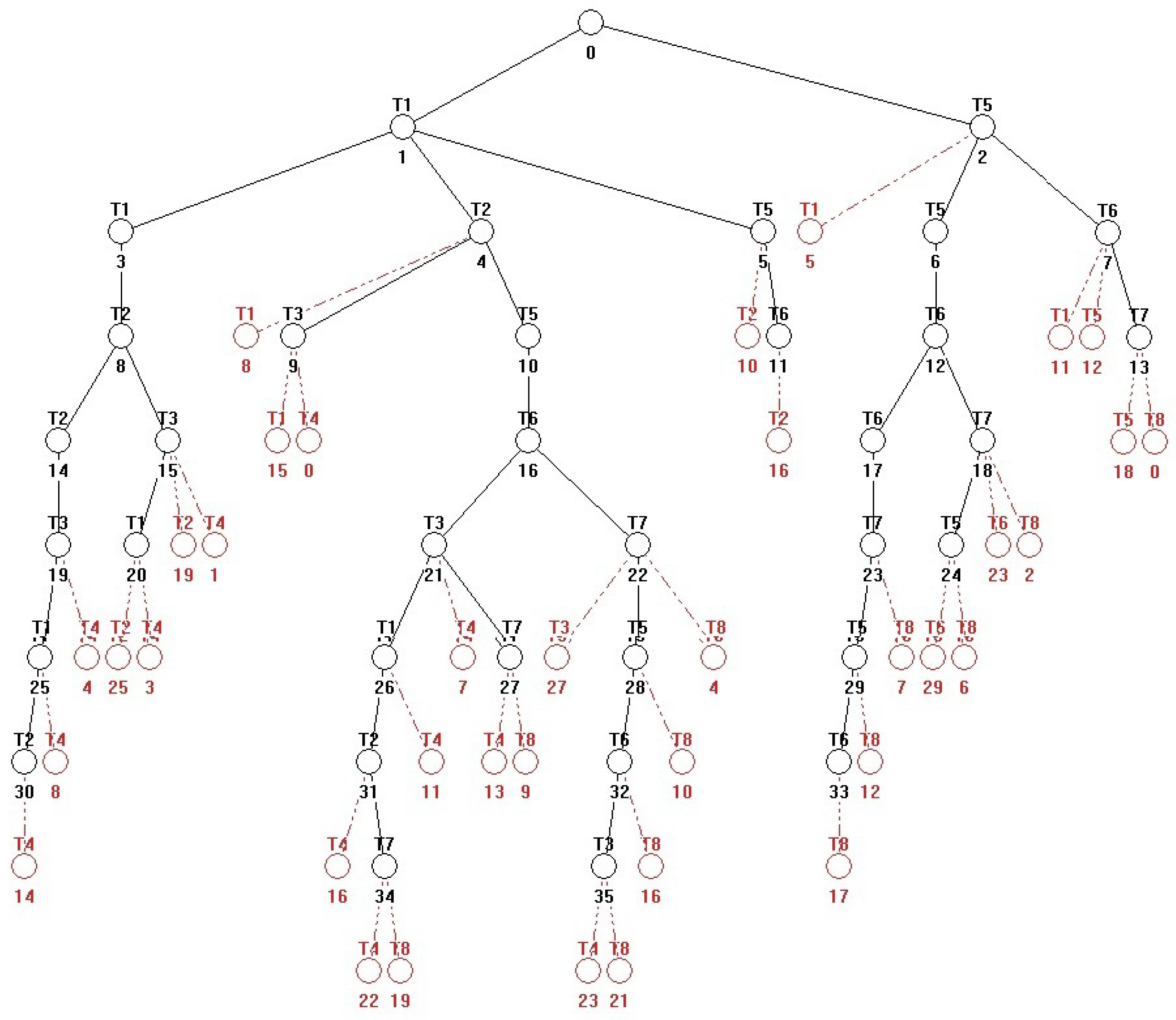

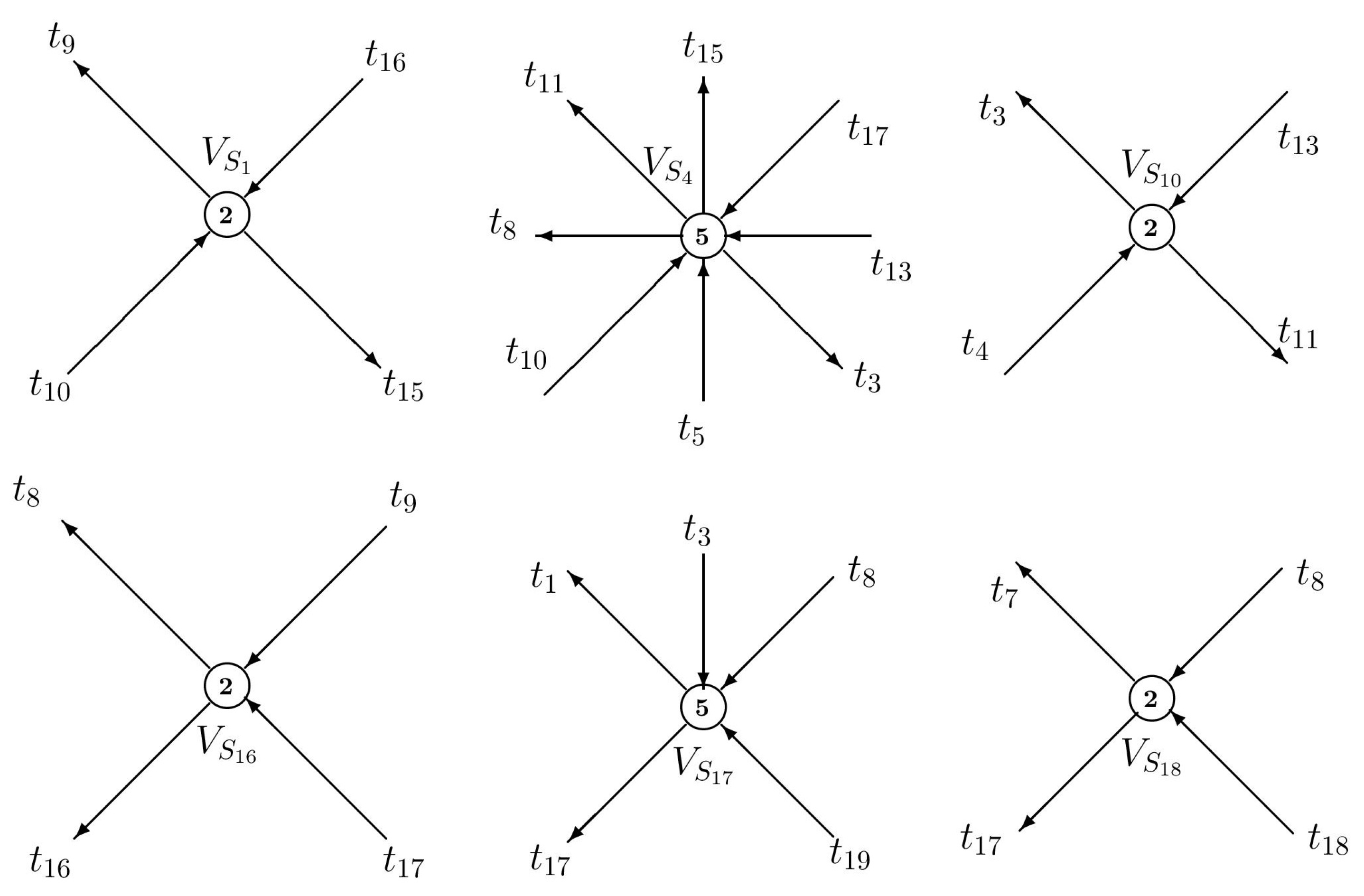

4. Examples of PN Models with a Simpler Structure

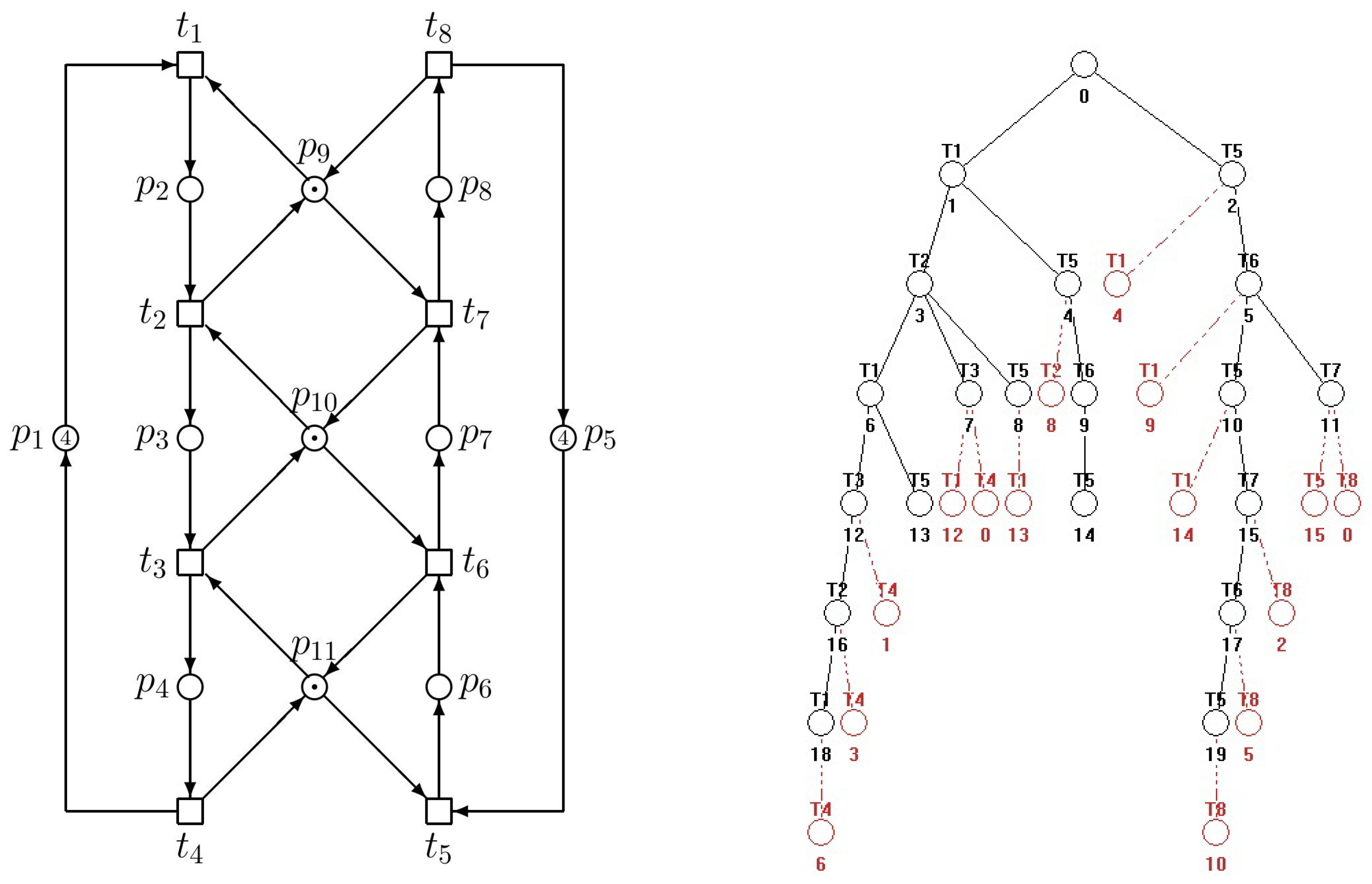

4.1. Example 1

Nonstandard Synthesis of a Monitor to Control the Strongly Dependent Siphon

4.2. Another Approach Using a Complementary Set of SMSs

- ;

- ;

- and (t is enabled at M).

Example 2

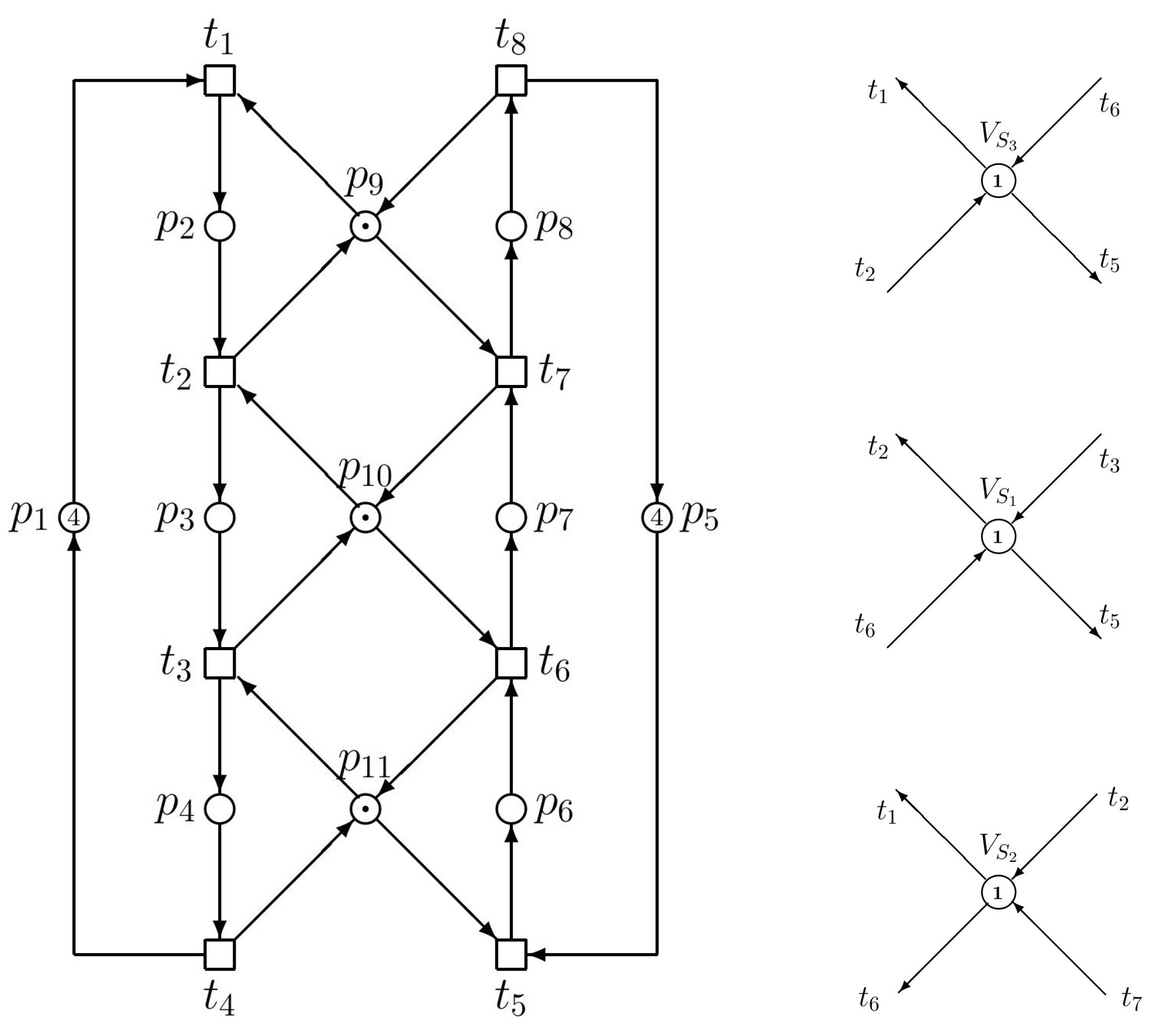

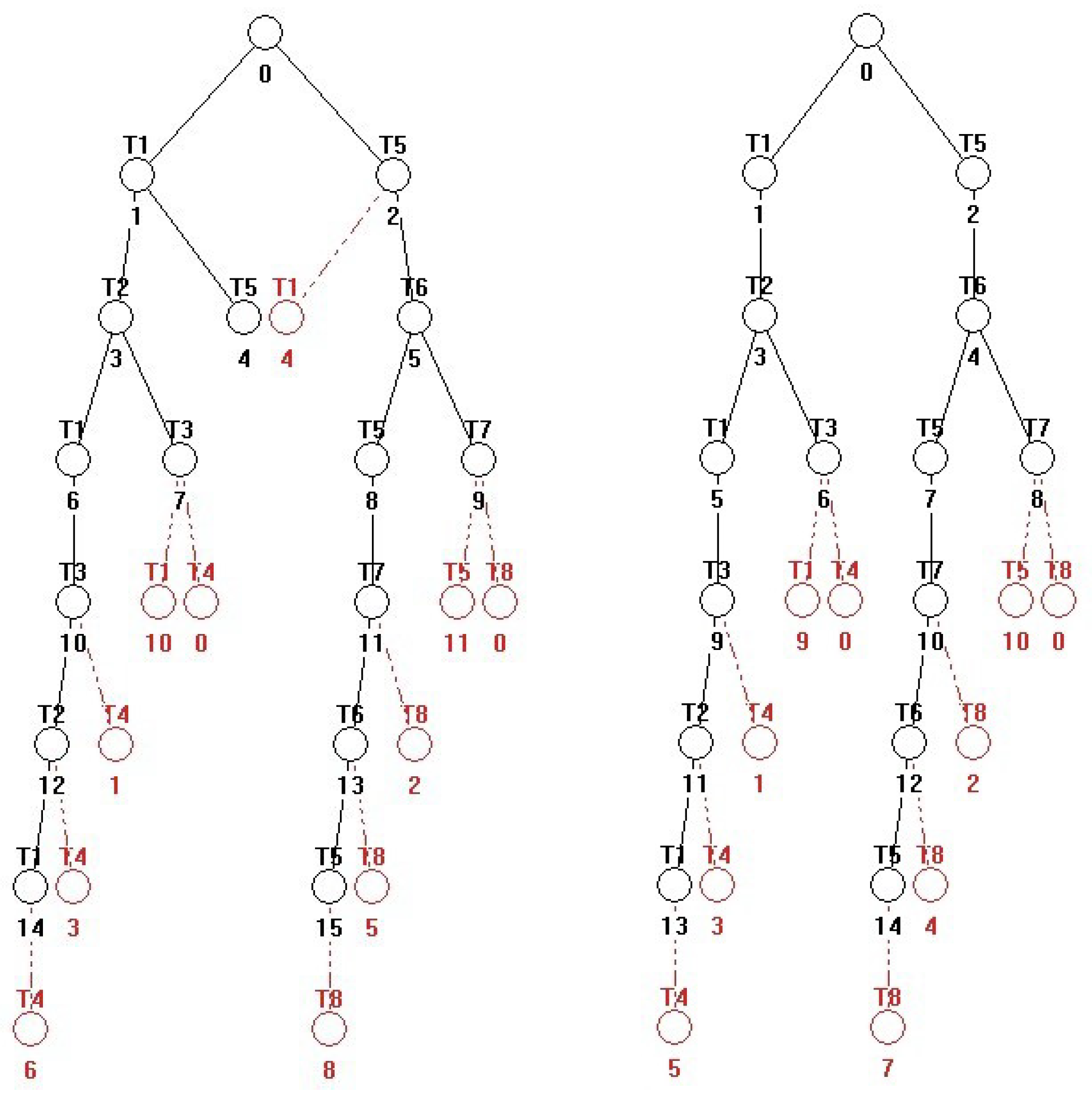

4.3. Simpler AMS with GPN Models

- 1.

- is a P-invariant of N, , and ;

- 2.

- .

- 1.

- is extended by adding n monitors such that are max-controlled, respectively;

- 2.

- , where.

- 1.

- is extended by adding n monitors such that are max-controlled, respectively, due to Proposition 3 (below);

- 2.

- , where

Example 3

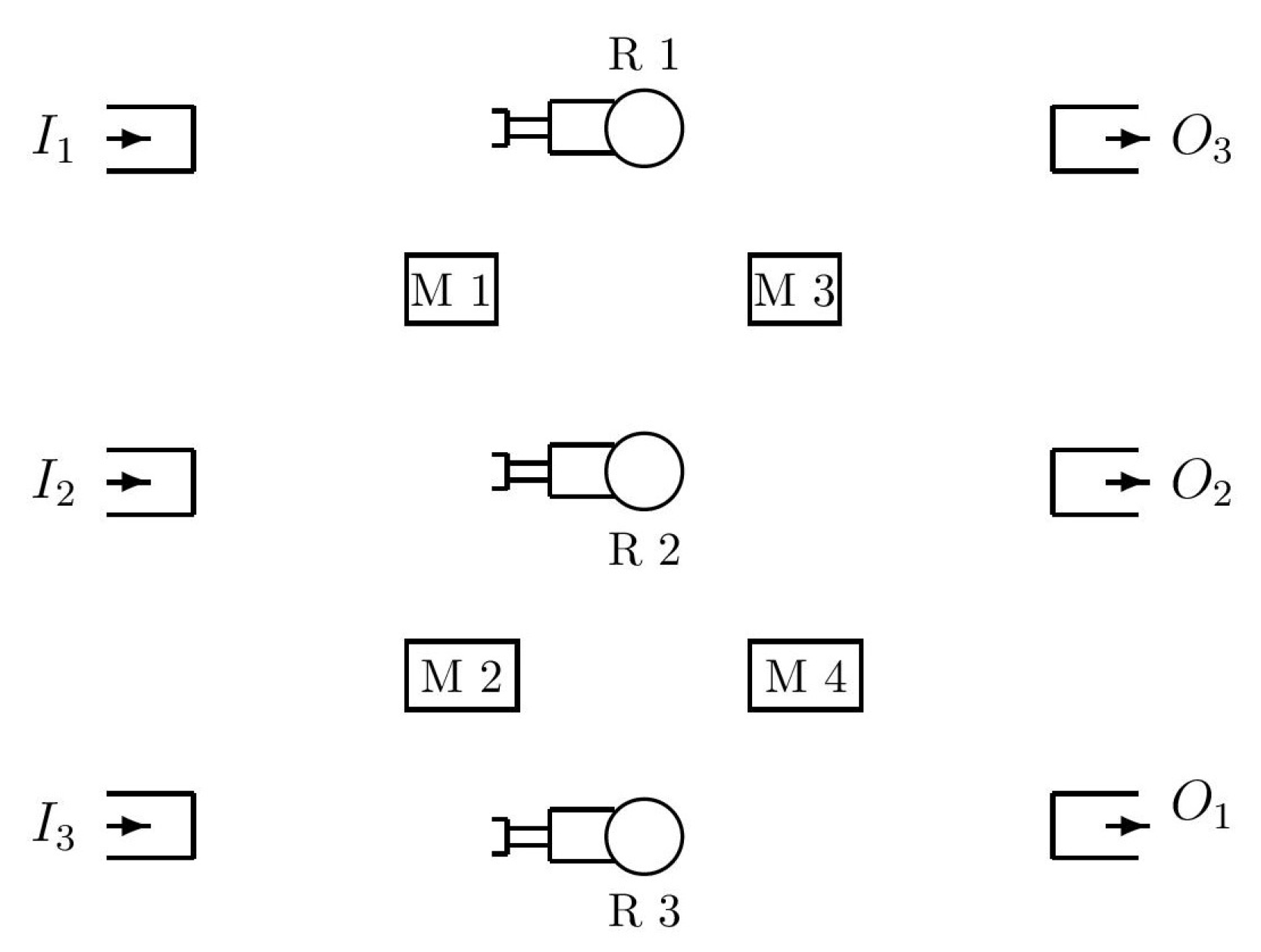

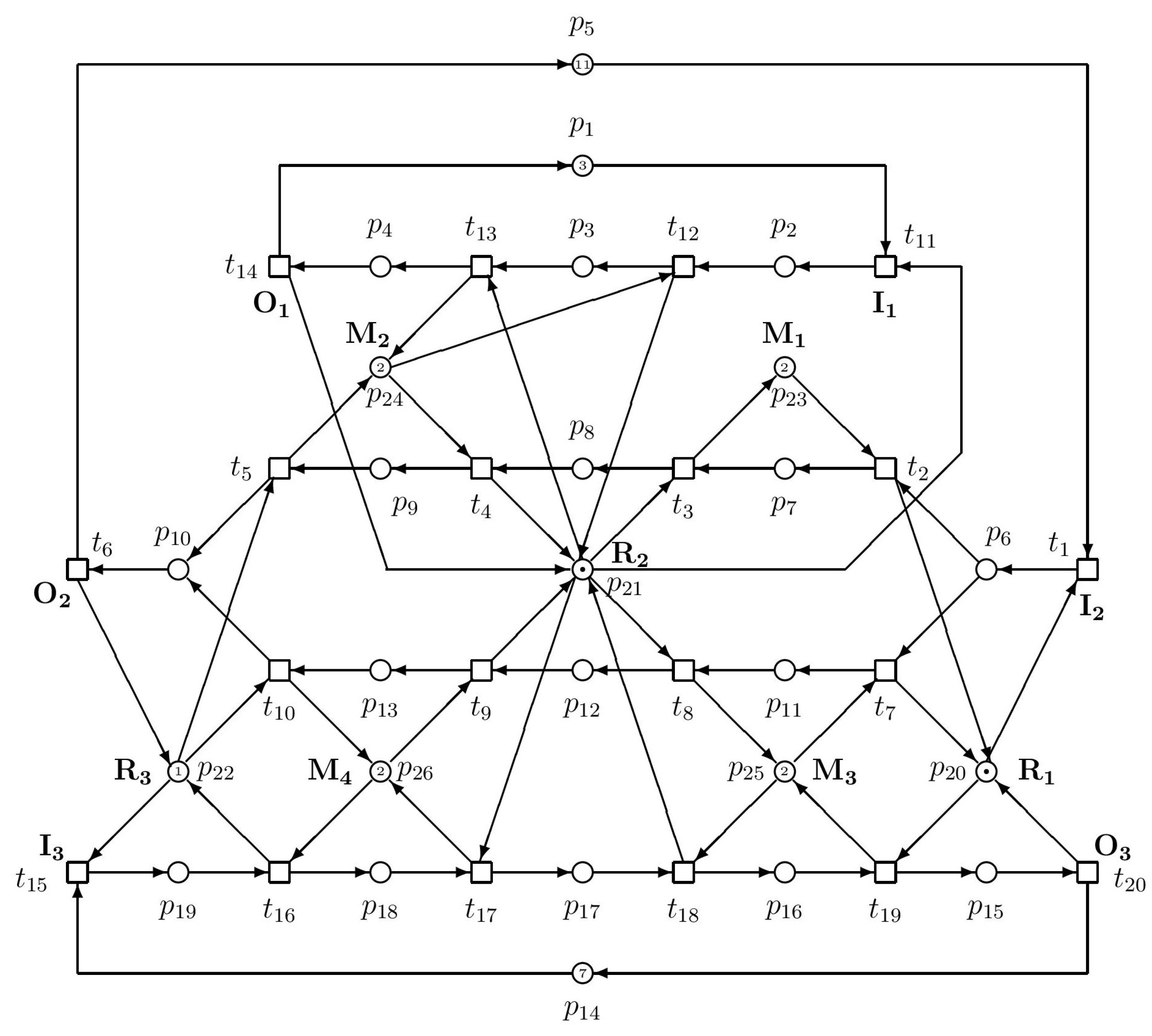

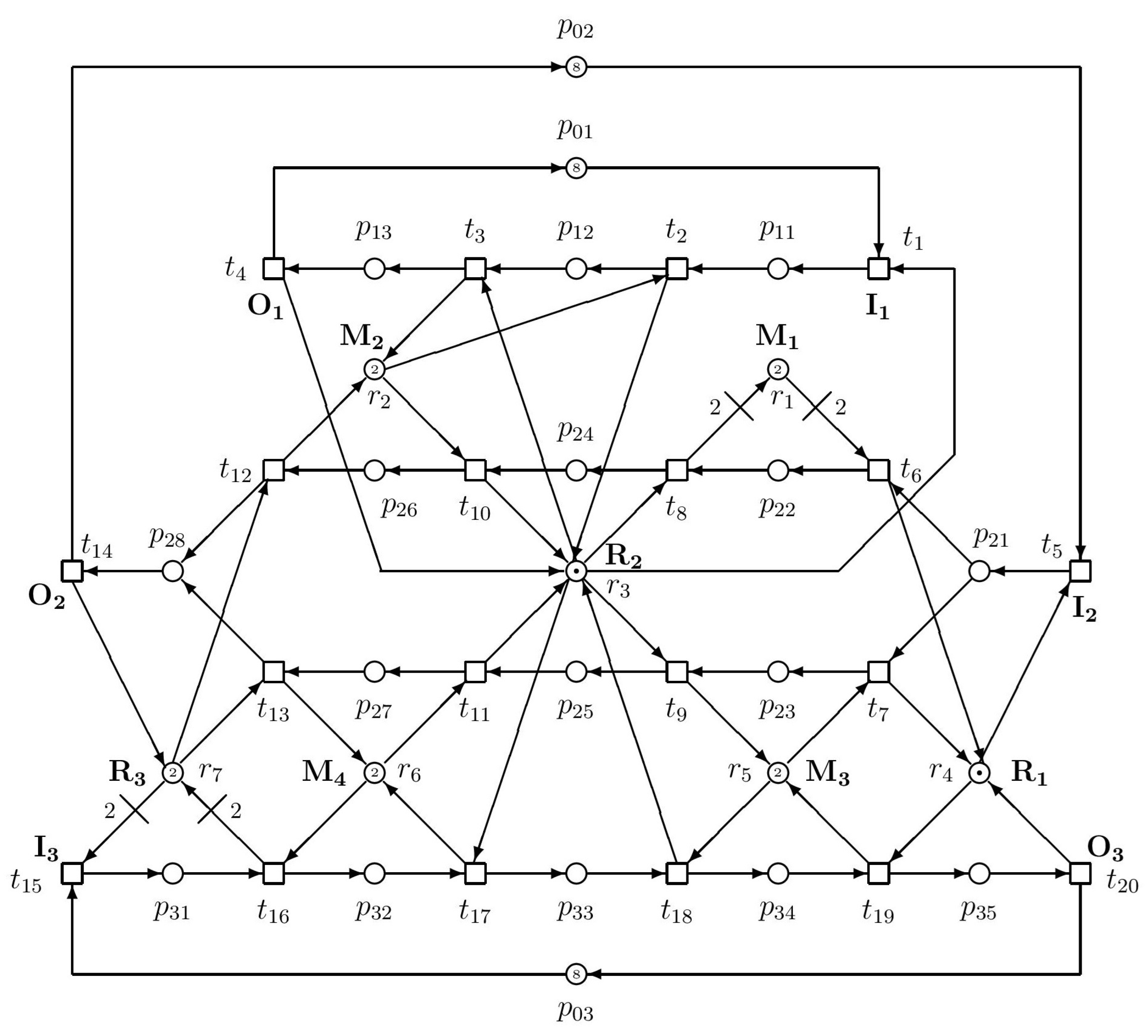

4.4. More Complex AMS with OPN Model

Example 4

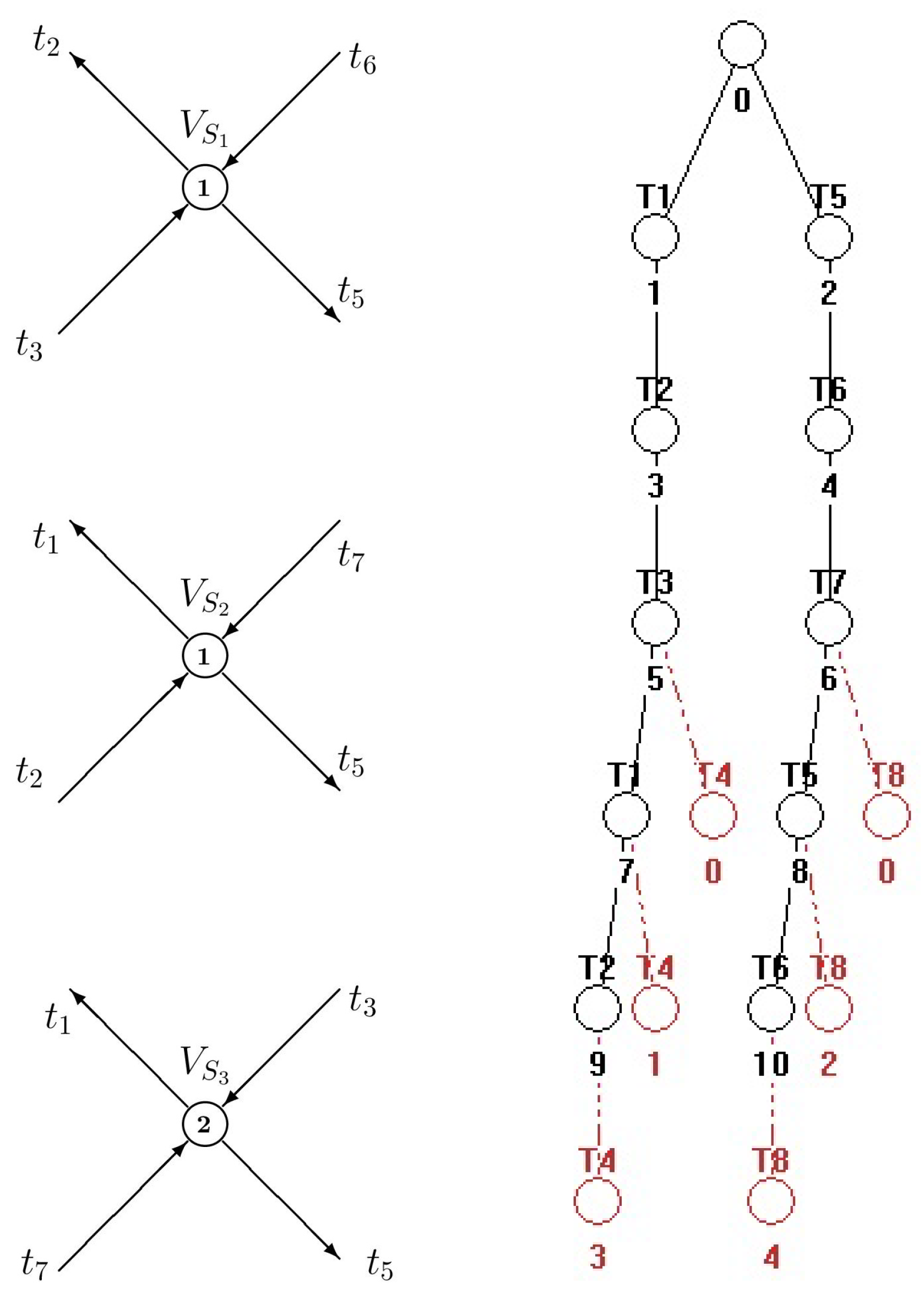

5. More Complex GPN Models of AMSs

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- is a partition such that (i) is called the set of operation places, where and ; (ii) is called the set of idle places; (iii) is called the set of resource places.

- 3.

- is called the set of transitions, where and .

- 4.

- , the subnet generated by , is a strongly connected state machine such that every circuit of the state machine contains idle place .

- 5.

- , there exists a unique minimal P-semiflow such that , and .

- 6.

- .

- 1.

- is a partition such that the following apply:

- , where for each , and for each , .

- .

- .

- 2.

- , where for each , and for each .

- 3.

- For each , the subnet is a strongly connected state machine such that every cycle contains .

- 4.

- For each , there exists a unique minimal P-invariant such that , and .

- 5.

- .

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- ; and

- 3.

- .

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- .

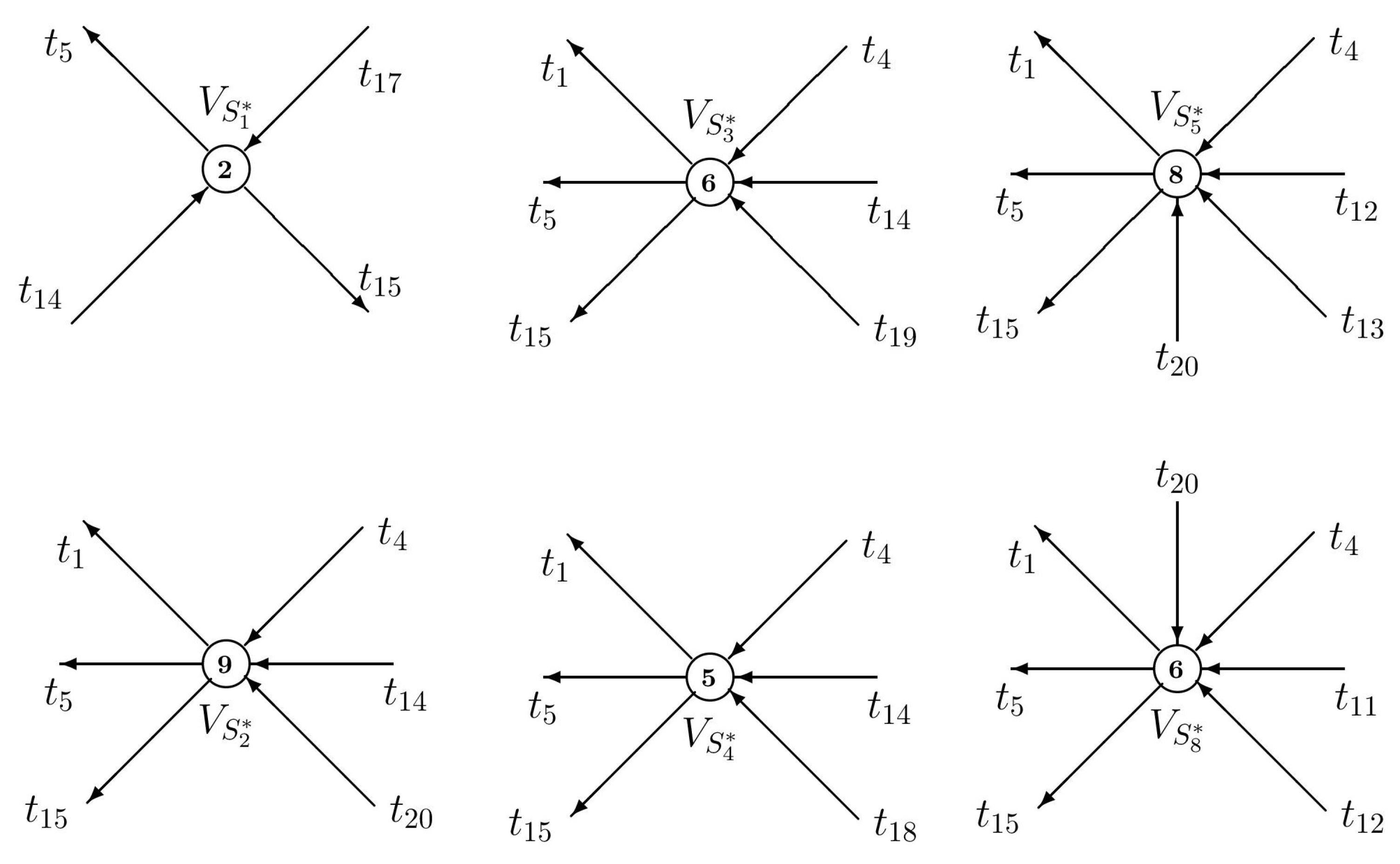

5.1. Properties of Siphons in PR Nets

- 1.

- is extended by adding n monitors such that are max-controlled, respectively, due to Proposition 7;

- 2.

- ,where ;

- 3.

- .

- 1.

- is extended by adding n monitors such that are max-controlled, respectively, due to Proposition 7;

- 2.

- ,where ;

- 3.

- .

- Step 1 ;

- Step 2 , where ;

- Step 3 , let be such a place that , , . We assume that there are m such places, . Certainly, we have . , let be such a place that . ;

- Step 4 , where , and s.t. .

5.2. Example 5

6. Results

6.1. Deadlock Prevention in Simpler OPN Models of AMSs

6.2. Deadlock Prevention in Simpler GPN Models of AMS

6.3. Deadlock Prevention in More Complex OPN Models of AMS

6.4. Deadlock Prevention in More Complex GPN Models of AMSs

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMSs | Automated Manufacturing Systems |

| DESs | Discrete-Event Systems |

| FMSs | Flexible Manufacturing Systems |

| PNs | Petri Nets |

| RASs | Resource Allocation Systems |

| OPNs | Ordinary PNs |

| GPNs | Generalized PNs |

| SMSs | Strict Minimal Siphons |

| PRs | Systems of Simple Sequential Processes with Resources |

| PR | Extended PR |

| PR | Generalized PR |

| s | Systems of Simple Sequential Processes with General Resources Requirement |

| PR | Generalized Linear System of Simple Sequential Processes with Resources |

| Rs | Systems of Sequential Systems with Shared Resources |

| PRs | Simple Systems of Simple Sequential Processes with Resources |

References

- Iordache, M.V.; Antsaklis, P.J. Supervisory Control of Concurrent Systems: A Petri Net Structural Approach; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarjan, R. Depth-First Search and Linear Graph Algorithms. SIAM J. Comput. 1972, 1, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Barkaoui, K. A survey of siphons in Petri nets. Inf. Sci. 2016, 363, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Zhou, M. A Siphon-based Deadlock Prevention Policy for a Class of Petri Nets-S3PMR. In Proceedings of the 17th World Congress of the International Federation of Automatic Control, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–11 July 2008; pp. 14467–14472. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Y.C. Computation of Elementary Siphons in Petri Nets For Deadlock Control. Comput. J. 2006, 49, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, Z.W. Liveness Enforcing Supervision in Video Streaming Systems Using Siphons. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2009, 25, 1863–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.Y. Max*-controlled siphons for liveness of S3PGR2. IET Control Theory Appl. 2007, 1, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.Y.; Chen, J.-T.; Yu, F. A novel liveness condition for S3PGR2. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2012, 35, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.F.; Li, Z.W.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; El-Tamimi, A.-Z.M.; Nasr, E.A. Extended Elementary Siphons and Their Application to Liveness-Enforcement of Generalized Petri Nets. Asian J. Control 2014, 16, 1789–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricas, F.; García-Vallés, F.; Colom, J.M.; Ezpeleta, J. An Iterative Method for Deadlock Prevention in FMS. In Discrete Event Systems; The Springer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science; Boel, R., Stremersch, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 569. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Reveliotis, S.A. Deadlock avoidance in sequential resource allocation systems with multiple resource acquisitions and flexible routings. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2001, 46, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricas, F.; Colom, J.M.; Ezpeleta, J. A solution to the problem of deadlocks in concurrent systems using Petri nets and integer linear programming. In Proceedings of the 11th Europe Simulation Symposium (ESS’99), Erlangen, Germany, 26–28 October 1999; pp. 542–546, ISBN 1-56555-177-X. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Zhao, M.; Liu, D.; Hong, L. An Efficient Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention Policy for a Class of Generalized Petri Nets. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016, 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.W.; Zhou, M.C. A parameterized liveness and ratio-enforcing supervisor for a class of generalized Petri nets. Automatica 2013, 49, 3167–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Zhou, M.C. Elementary Siphons of Petri Nets and Their Application to Deadlock Prevention in Flexible Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2004, 34, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, J.; Colom, J.M.; Martinez, J. A Petri net based deadlock prevention policy for flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1995, 11, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Zhou, M.C. Deadlock Resolution in Automated Manufacturing Systems: A Novel Petri Net Approach; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricas, F.; Garcia-Valles, F.; Colom, J.M.; Ezpeleta, J. A Petri net structure-based deadlock prevention solution for sequential resource allocation systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, ICRA 2005, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Dai, W.; Wang, S.G.; Ning, F. Deadlock Prevention Policy for S4PR Nets Based on Siphon. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 50648–50658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, D. Extended elementary siphon-based deadlock prevention policy for a class of generalised Petri nets. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2014, 27, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, Z.; Barkaoui, K. Monitor Design for Siphon Control in S4R Nets: From Structure Analysis Points of View. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2011, 7, 6677–6690. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, E.E.; Rovetto, C.A.; Colom, J.M. An algorithm to compute the minimal siphons in S4PR nets. Discret. Event Dyn. Syst. 2012, 22, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; You, D.; Zhou, M.C. A necessary and sufficient condition for a resource subset to generate a strict minimal siphon in S4PR. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 4173–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, H. A Strict Minimal Siphon-Based Necessary and Sufficient Condition for Liveness Verification in General Petri Nets. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 53517–53530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M. Liveness-Enforcing Supervisor Design for a Class of Generalized Petri Net Models of Flexible Manufacturing Systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2007, 1, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hussin, M.H.; Banaszak, Z.A. Siphon-based deadlock prevention for a class of S4PR generalized Petri nets. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Control, Automation and Information Sciences (ICCAIS), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 October–1 November 2017; IEEE Xplore, Electronic: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-L.; Tseng, C.-Y.; Chen, J.-C. Enhancement of Computational Efficiency for Deadlock Recovery of Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Improved Generating and Comparing Aiding Matrix Algorithms. Processes 2023, 11, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, T.K.; Chang, W.; Cho, H.; Wysk, R.A. A structured approach to deadlock detection, avoidance and resolution in flexible manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1994, 32, 2361–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor, V.D.; Shattuck, S.H. On deadlock detection in distributed systems. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1980, 6, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysk, R.A.; Yang, N.-S.; Joshi, S. Resolution of deadlocks in flexible manufacturing systems: Avoidance and recovery approaches. J. Manuf. Syst. 1994, 13, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebraeel, N.Z.; Lawley, M.A. Deadlock detection, prevention, and avoidance for automated tool sharing systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2001, 17, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, I.; Karatkevich, A. A Deadlock Recovery Policy for Flexible Manufacturing Systems with Minimized Traversing within Reachability Graph. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 16–18 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Liu, G.Y.; Hanisch, H.-M.; Zhou, M.C. Deadlock Prevention Based on Structure Reuse of Petri Net Supervisors for Flexible Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2012, 42, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapkovič, F. Sustainability of Automated Manufacturing Systems with Resources by Means of Their Deadlock Prevention. Electronics 2024, 13, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zhong, C.; Wang, X.; Rehman, A.U.; Umer, U.; Wu, A.N. A Deadlock Prevention Policy for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Modeled With Petri Nets Using Structural Analysis. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 49362–49376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, I.B.; ElMaraghy, H.A. Deadlock prevention and avoidance in FMS: A Petri net based approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 1998, 14, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Zhou, M.C.; Wu, N.Q. A Survey and Comparison of Petri Net-Based Deadlock Prevention Policies for Flexible Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part C Appl. Rev. 2008, 38, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.S. Design of deadlock prevention supervisors using Petri nets. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 35, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkaoui, K.; Abdallah, I.B. A Deadlock Prevention Method for a Class of FMS. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–25 October 1995; pp. 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shpitalni, M. Smart deadlock prevention policy for flexible manufacturing systems using Petri nets. IET Control Theory Appl. 2009, 3, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, S.S.; Bhatwadekar, S.D. Analysis of Flexible Manufacturing System using Petri Nets to design a Deadlock Prevention Policy. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2016, 5, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R. A deadlock prevention approach for flexible manufacturing systems with uncontrollable transitions in their Petri net models. Asian J. Control 2011, 14, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, Z. A deadlock prevention approach for flexible manufacturing systems without complete siphon enumeration of their Petri net models. Eng. Comput. 2009, 25, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; Wu, W.H.; Yang, J. Deadlock prevention policy for a class of petri nets based on complementary places and elementary siphons. J. Intell. Manuf. 2015, 26, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Cordone, R.; Fumagalli, I. Selective siphon control for deadlock prevention in Petri nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part A 2008, 38, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzam, M. An Optimal Deadlock Prevention Policy for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Petri Net Models with Resources and the Theory of Regions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2002, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chao, D.; Uzam, M. Maximally permissive deadlock prevention via an invariant controlled method. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 4431–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, K.; Zhou, M.C.; Liu, H.; Tian, F. Optimal Petri-Net-Based Polynomial-Complexity Deadlock-Avoidance Policies for Automated Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2009, 39, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricas, F. Deadlock Analysis, Prevention and Avoidance in Sequential Resource Allocation Systems. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.-L. One Computational Innovation Transition-Based Recovery Policy for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Petri Nets. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.F.; Barkaoui, K. Deadlock analysis and control based on Petri nets: A siphon approach review. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenbach, K.; Ridder, H. Liveness in bounded Petri nets which are covered by T-invariants. In Applications and Theory of Petri Nets, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Valette, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1994; Volume 815, pp. 358–375. [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbach, K. Linear algebraic calculation of deadlocks and traps. In Concurrency and Nets; Voss, K., Genrich, H.J., Rozenberg, G., Eds.; Advances in Petri Nets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, E.; Delfmann, P.; Thimm, M. Quantitative Deadlock Analysis in Petri Nets using Inconsistency Measures. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Bolzano, Italy, 1–3 September 2021; 10p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, M. On the evaluation of inconsistency measures. In Measuring Inconsistency in Information; Series Studies in Logic; Grant, J., Martinez, M.V., Eds.; College Publications: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Volume 73, ISBN 9781848902442. [Google Scholar]

- Desel, J.; Kilinc, G. Observable Liveness. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Petri Nets and Software Engineering, PNSE’14, a Satellite Event of Petri Nets 2014, Tunis, Tunisia, 23–24 June 2014; CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 1160. Moldt, D., Rölke, H., Eds.; Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2014; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.; He, W.; Li, Z.; Wu, N.; Qu, T. Deadlock analysis and control using Petri net decomposition techniques. Inf. Sci. 2019, 482, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, I.; Karatkevich, A. Deadlock detection in Petri nets: One trace for one deadlock? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI), Lisbon, Portugal, 16–18 June 2014; 5p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J. Efficient Deadlock Detection in FMS Based on the Transitive Matrix of Resource Share Places. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Technical Conference on Circuits/Systems, Computers and Communications (ITC-CSCC 2008), Shimonoseki City, Japan, 6–9 July 2008; pp. 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Deadlock Analysis of Petri Nets Based on the Resource Share Places Relationship. Stud. Inform. Control 2007, 16, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Zhou, J.; Muhammad, B.B. Optimal Supervisory Control for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Model with Petri Nets: A Place-Transition Control. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 58566–58578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamalidou, K.; Moody, J.; Lemmon, M.; Antsaklis, P. Feedback control of Petri nets based on place invariants. Automatica 1996, 32, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Guang, W.S.; Zhou, M.C. Computation of strict minimal siphons in a class of Petri nets based on problem decomposition. Inf. Sci. 2017, 409–410, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Xie, X.-L. Deadlock Analysis of Petri Nets Using Siphons and Mathematical Programming. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1997, 13, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.D. Revised dependent siphon. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 43, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Uzam, M.; Zhou, M.C. Comments on “Deadlock Prevention Policy based on Petri Nets and Siphons”. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2004, 42, 5253–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, L. Supervisor Simplification in FMSs: Comparative Studies and New Results Using Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xing, K.; Luo, J.; Feng, Y. Robust deadlock control for automated manufacturing systems with an unreliable resource. Inf. Sci. 2016, 346, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Li, Z.; Uzam, M.; Wu, N.; Al-Ahmari, A. On structural reduction of liveness-enforcing Petri net supervisors for flexible manufacturing systems: An algebraic approach. IMA J. Math. Control Inf. 2018, 35, 1217–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Wang, A.; Chen, Y.; Wu, N.; Qu, T.; Khalgui, M.; Li, Z. Most permissive liveness-enforcing Petri net supervisors for discrete event systems via linear monitors. ISA Trans. 2019, 92, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.W.; Hu, H.S.; Wang, A.R. Design of Liveness-Enforcing Supervisors for Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man-Cybern.-Part C Appl. Rev. 2007, 37, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhou, M.C.; Li, Z.W. A Method to Compute Strict Minimal Siphons in a Class of Petri Nets Based on Loop Resource Subsets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Mans Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2012, 42, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Optimal Supervisory Control of Flexible Manufacturing Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Computer Science, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers–CNAM, École Doctorale Informatique, Télécommunications et Electronique de Paris, Paris, France, 2015. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-01288919 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Liu, G. Supervisor Synthesis for Automated Manufacturing Systems Based on Structure Theory of Petri Net. Ph.D. Thesis, Automatic Control Engineering, Conservatoire National Des Arts et Metiers—CNAM, École Doctorale Informatique, Télécommunications et Electronique de Paris, Paris, France, 2014. (In English). [Google Scholar]

- Chao, D.Y. Improved Controllability Test for Dependent Siphons in S3PR Based on Elementary Siphons. Asian J. Control 2010, 12, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzam, M.; Li, Z.W.; Abukubar, U.S. A General Approach for the Computation of a Liveness Enforcing Supervisor for the Petri Net Model of an FMS. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Petri Nets for Adaptive Discrete-Event Control Systems—ADECS 2014 (Co-Located with 35th International Conference on Application and Theory of Petri Nets and Concurrency (Petri Nets 2014), Tunis, Tunisia, 24 June 2014; Uzam, M., Li, Z.W., Abubakar, U.S., Eds.; University of Carthage: Carthage, Tunisia, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, E.A.; Tamimi, A.M.; Al-Ahmari, S.; Kaid, H. Comparison and Evaluation of Deadlock Prevention Methods for Different Size Automated Manufacturing Systems. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 537893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.R.; Li, Z.W.; Jia, J.Y. A Petri nets based deadlock avoidance policy for flexible manufacturing systems. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, IECON 2004, Chicago, IL, USA, 2–6 November 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Zhou, M.C. Clarifications on the Definitions of Elementary Siphons in Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2006, 36, 1227–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Li, Z. A Fast Algorithm to Find a Set of Elementary Siphons for a Class of Petri Nets. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, Shanghai, China, 7–10 October 2006; pp. 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.Y.; Wu, K.-C.; Chen, J.-T.; Lee, M.Y.J. Controllability of Strongly and Weakly Dependent Siphons under Disturbanceless Control. Intell. Control Autom. 2011, 2, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaid, H.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Li, Z.; Davidrajuh, R. Single Controller-Based Colored Petri Nets for Deadlock Control in Automated Manufacturing Systems. Processes 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkaoui, K.; Pradat-Peyre, J.F. On Liveness and Controlled Siphons in Petri Nets. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Applications and Theory of Petri Nets, Osaka, Japan, 24–28 June 1996; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 1091, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidrajuh, R. Modeling Discrete-Event Systems with GPenSIM: An Introduction; Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; 155p, ISBN 978-3-319-73102-5. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-73102-5 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Chao, D.Y.; Pan, Y.-L.; Liao, W.-H. Structure Based Derived Uniform Formula for Siphon, Its Complementary Set and T-characteristic Vectors. In Proceedings of the 7th IFAC Conference on Manufacturing Modelling, Management, and Control, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 19–21 June 2013; pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.-Y.; Chao, D.Y. Sequence of Control in S3PMR. Comput. J. 2009, 53, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Li, Z.W.; Al-Ahmari, A. Liveness Analysis of Petri Nets Using Siphons and Mathematical Programming. In Proceedings of the 12th IFAC/IEEE Workshop on Discrete Event Systems, Cachan, France, 14–16 May 2014; pp. 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Chang, L.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Wu, N.Q. Robust deadlock control for automated manufacturing systems based on elementary siphon theory. Inf. Sci. 2020, 510, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Barkaoui, K. Necessary and sufficient liveness condition of GS3PR Petri nets. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2015, 46, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Uzam, M.; Zhou, M.C. Deadlock control of concurrent manufacturing processes sharing finite resources. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 38, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkaoui, L.; Couvreur, J.-M.; Klai, K. On the Equivalence Between Liveness and Deadlock-Freeness in Petri Nets. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference, Applications and Theory of Petri Nets, ICATPN 2005, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Ciardo, G., Darondeau, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3536, pp. 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z. Liveness and deadlock-freeness verification and enforcement in bounded Petri nets using basis reachability graphs. Automatica 2024, 164, 111625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duo, W.; Guo, X.; Jiang, X.; You, D.; Barkaoui, K.; Zhou, M.C. Computation of an Emptiable Minimal Siphon in a Subclass of Petri Nets Using Mixed-Integer Programming. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Siphons | Traps |

|---|---|

| Siphon(s) | , | , | |||

| Transition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čapkovič, F. Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention of Complex Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Generalized Petri Nets. Electronics 2025, 14, 4889. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244889

Čapkovič F. Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention of Complex Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Generalized Petri Nets. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4889. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244889

Chicago/Turabian StyleČapkovič, František. 2025. "Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention of Complex Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Generalized Petri Nets" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4889. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244889

APA StyleČapkovič, F. (2025). Siphon-Based Deadlock Prevention of Complex Automated Manufacturing Systems Using Generalized Petri Nets. Electronics, 14(24), 4889. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244889