Abstract

Digital Twins are becoming central enablers of Europe’s digital and green transitions, yet their data-intensive and autonomous nature exposes them to one of the most complex regulatory environments in the world. This article presents a comprehensive scoping review of how six principal European digital laws—the General Data Protection Regulation, Data Governance Act, Data Act, Artificial Intelligence Act, NIS2 Directive, and Cyber Resilience Act—jointly govern the design, deployment, and operation of Digital Twin systems. Building on the PRISMA-ScR methodology, the study constructs a Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF) that consolidates overlapping obligations across data governance, privacy, cybersecurity, transparency, interoperability, and ethical responsibility. The framework is operationalised through a Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM) that enables qualitative assessment of compliance maturity in research and innovation projects. Applying these tools to representative European cases in Smart Cities, Industrial Manufacturing, Transportation, and Energy Systems reveals strong convergence in data governance, security, and interoperability, but also persistent gaps in the transparency, explainability, and accountability of AI-driven components. The findings demonstrate that European digital legislation forms a coherent yet fragmented ecosystem that increasingly requires integration through compliance-by-design methodologies. The article concludes that Digital Twins can act not only as regulated technologies but also as compliance infrastructures themselves, embedding legal, ethical, and technical safeguards that reinforce Europe’s vision for trustworthy, resilient, and human-centric digital transformation.

1. Introduction

The Digital Twin has emerged as one of the most transformative concepts in the digitalisation of physical systems. Originally formulated within product lifecycle management and aerospace engineering, it was conceived as a virtual representation of a physical asset that remains continuously synchronised through data exchange [1]. Early articulations defined the twin as a high-fidelity virtual counterpart capable of mirroring a product or system throughout its lifecycle, assimilating sensor data and simulation models to support monitoring, diagnostics, and predictive decision-making [2]. This concept evolved into a general paradigm for the integration of cyber-physical systems, combining virtual models, real-time data, and control mechanisms to enable intelligent management of complex infrastructures [3].

In this paradigm, a Digital Twin is understood as a persistent, data-driven virtual counterpart of a physical entity, process, or system. It maintains a bidirectional connection with its physical counterpart through sensing, communication, and control. The twin ingests data from the physical world, updates internal models, and generates predictions and decisions that can be enacted in the physical system [4]. This continuous feedback loop allows the twin to support design optimisation, operational efficiency, maintenance forecasting, and end-of-life management. Digital twins integrate hybrid modelling techniques that combine physics-based and machine-learning approaches, semantic data layers that ensure interoperability across domains, and uncertainty quantification that provides confidence in predictions and automated decisions [5]. The resulting systems span multiple levels of complexity, from product and process twins to large-scale system twins representing factories [6], transportation networks [7], power grids [8], and cities [9].

The technological architecture of a Digital Twin typically comprises five interrelated layers: the physical asset instrumented with sensors and actuators; a communication layer that enables secure and reliable data exchange; a virtual layer containing physics-based and data-driven models; a synchronisation layer that maintains alignment between physical and virtual states in time and context; and a service layer providing analytics, visualisation, and control functionalities [4]. Through this architecture, Digital Twins transform raw data into actionable knowledge, enabling real-time decision support, optimisation, and increasingly autonomous operation. As their fidelity and autonomy increase, they evolve from descriptive models to predictive and prescriptive systems that interact directly with the physical world.

These characteristics make Digital Twins powerful enablers of digital transformation across all major sectors of the European economy. In smart cities, they enable planners to simulate urban planning [10], integrate renewable energy [11], and improve mobility systems [12]. In industry, they support production-line optimisation [13], predictive maintenance [14], and supply-chain resilience [15]. In mobility and transportation, they underpin connected and autonomous vehicles that continuously exchange data with cloud-based models [16]. In energy systems, they facilitate integration of renewable resources [17], real-time grid balancing [18], and distributed energy management [19]. The convergence of these capabilities creates a foundational infrastructure for Europe’s data-driven, sustainable, and resilient economy.

However, the same data-intensive and autonomous features that define Digital Twins also make them exceptionally sensitive to the European Union’s comprehensive framework of digital legislation [20]. Each component of a Digital Twin corresponds to specific legal domains that regulate how data and intelligent systems are designed and operated. The General Data Protection Regulation [21] governs personal data collected through sensors, logs, and user interactions, establishing principles of lawful processing, transparency, and individual control. The Data Governance Act [22] and the Data Act [23] define how industrial and public data can be shared, reused, and exchanged under fair and transparent conditions. The Artificial Intelligence Act [24] introduces obligations for trustworthy and human-centric AI systems that underpin learning-enabled twins. The NIS2 Directive [25] establishes cybersecurity and resilience requirements for networked infrastructures, while the Cyber Resilience Act [26] mandates security-by-design principles for software and hardware components. Together, these instruments form an integrated yet fragmented legal environment that profoundly shapes the design, deployment, and operation of Digital Twin systems within the European Union.

The interaction between technical architectures and legal frameworks gives rise to a multidimensional compliance challenge. A single Digital Twin may simultaneously be subject to multiple regulatory obligations depending on its data sources, modelling methods, and connectivity patterns. Managing these overlapping requirements demands a unified approach that links the technical, organisational, and legal dimensions of system development. Compliance-by-design becomes not only a regulatory necessity but also a technical discipline that ensures accountability, interoperability, and trustworthiness throughout the lifecycle of the Digital Twin.

Against this background, this article provides a comprehensive review of how European digital regulations affect the development and deployment of Digital Twins across four key domains: smart cities, industry, mobility, and energy systems. It analyses how each legal instrument addresses specific challenges such as pervasive data collection, algorithmic decision-making, data sharing, and cybersecurity. Real-world examples illustrate both the benefits of Digital Twin technology and the compliance measures required for lawful and ethical operation. The article further proposes a unified compliance framework that aligns the requirements of the main EU legal acts with the technical architecture of Digital Twins, offering a structured pathway towards trustworthy and regulation-aligned innovation. By clarifying how Digital Twins intersect with the European legal order, the discussion contributes to advancing their responsible adoption as central enablers of Europe’s digital and green transitions. While previous studies typically analyse EU digital regulations in isolation, no existing work integrates the GDPR, DGA, Data Act, AI Act, NIS2, and CRA into a unified compliance model capable of guiding Digital Twin system design across domains. This article addresses this gap by proposing the first cross-sector, article-level legal-to-technical synthesis that links EU regulatory obligations directly to Digital Twin architecture, lifecycle governance, and evaluation criteria. To demonstrate the framework’s empirical validity, the study applies and evaluates it across four strategic sectors, Smart Cities, Industrial Manufacturing, Mobility and Transportation, and Energy Systems, thereby providing a cross-domain analysis of how compliance maturity manifests within the European Digital Single Market. Throughout this demonstration, the term ‘Digital Twin’ is generally used in its established technical meaning as a virtual counterpart continuously synchronised with a physical system through bidirectional data exchange, without any further distinction between different variants such as digital models, digital shadows, or digital threads.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the research design and methodological framework employed in the study. Section 3 examines the European Union’s principal digital laws and their implications for Digital Twin systems. Section 4 introduces the integrated compliance framework and its evaluation matrix, which together form the conceptual foundation of the analysis. Section 5, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 apply these tools across the selected sectors, while Section 9 discusses cross-sectoral insights. Finally, Section 10 concludes the article with key findings and directions for future research and policy development.

2. Methodology

This study employs a multi-phase methodological design that integrates legal scoping analysis, framework development, and cross-sectoral evaluation. The approach combines the systematic mapping principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) with design-science reasoning. The objective was to construct and validate a unified compliance framework that consolidates obligations from six principal European digital laws and operationalises them as actionable principles for Digital Twin design and governance. The methodology comprises three interdependent phases: (1) legal scoping and knowledge synthesis, (2) framework development, and (3) framework validation through case application.

2.1. Research Design and Objectives

The methodological architecture was designed to capture both the legal and technical dimensions of Digital Twin compliance under European law. The first phase systematically mapped the Union’s legislative corpus governing data protection, artificial intelligence, data sharing, and cybersecurity.

The second phase synthesised these findings into a conceptual and operational framework defining the principal compliance domains for Digital Twin systems. The third phase applied and evaluated this framework across representative European cases to test its interpretive robustness and cross-sectoral relevance. The study was guided by four research questions:

- 1.

- Which European legal instruments collectively regulate Digital Twin systems within and across the selected sectors?

- 2.

- How do the provisions of these instruments interact to create cumulative or overlapping compliance obligations?

- 3.

- What unified framework can support lawful, secure, and interoperable Digital Twin implementation within the European Digital Single Market?

- 4.

- How can the proposed framework be validated through cross-sectoral case application to assess its interpretive robustness and practical effectiveness?

This design positions the study not only as a scoping review of European digital regulation but also as an integrated research and development process culminating in the construction and empirical validation of the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF).

2.2. Phase 1: Legal Scoping and Knowledge Synthesis

The first research phase applied a structured scoping-review methodology based on the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Its purpose was to map and synthesise the European Union’s digital legislative corpus that regulates the design, deployment, and operation of Digital Twin systems. The analysis identified, classified, and interpreted legal instruments that collectively define the normative, technical, and organisational foundations for lawful and trustworthy Digital Twin innovation within the European Digital Single Market.

2.2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Conceptual Boundaries

Eligibility criteria ensured inclusion of legally binding and technologically relevant instruments. The review considered EU regulations, directives, and legislative proposals adopted, published, or under final negotiation between 2016 and 2025, the period in which Europe’s digital-governance architecture consolidated after adoption of the GDPR. Documents were included if they

- Regulated or substantively influenced the collection, sharing, processing, or protection of digital data and intelligent systems.

- Contained provisions affecting cross-sectoral data governance, artificial-intelligence oversight, or cybersecurity of digital infrastructures.

- Were published in consolidated form on EUR-Lex or in official repositories of the European Commission or ENISA.

- Were applicable across multiple sectors, including smart cities, industry, mobility, and energy systems.

Excluded were repealed legislation, national measures, non-binding communications, soft-law instruments, or technical standards lacking direct regulatory authority. The temporal and thematic boundaries ensured comprehensive coverage of the six flagship legislative acts defining the EU’s digital legal order.

2.2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Primary legal texts were retrieved from the following authoritative sources:

- EUR-Lex: for consolidated EU regulations, directives, and legislative proposals.

- ENISA (European Union Agency for Cybersecurity): for cybersecurity-related directives and technical guidelines.

- CORDIS and the Publication Office of the European Union: for interpretative reports, policy evaluations, and impact assessments complementing legal texts.

The search strategy combined controlled and free-text terms to capture all relevant instruments. Search expressions used Boolean combinations such as “data protection regulation” OR “GDPR” AND “Digital Twin”, “data governance act” OR “data act”, “artificial intelligence act” OR “AIA”, “network and information security directive” OR “NIS2”, and “cyber resilience act”. To ensure comprehensive coverage, each query was further refined with contextual keywords (“smart city”, “industry”, “mobility”, “energy system”) and executed in English and official EU languages. Searches were performed between January and July 2025 and limited to official EU documents to ensure authenticity and legal validity. The study included legal texts from EUR-Lex and ENISA alongside academic literature to ensure the scoping review captured both regulatory substance and interpretive scholarship.

2.2.3. Source Selection and Screening Procedure

Source selection followed the PRISMA-ScR four-stage workflow: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion.

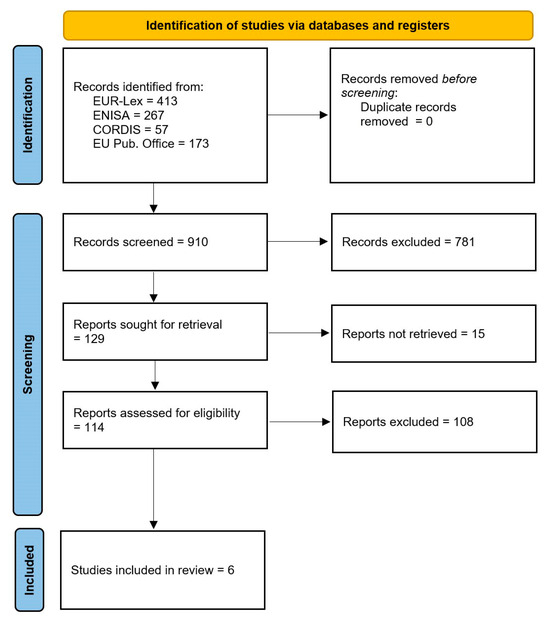

- Identification: An initial pool of 910 records was retrieved from the databases listed above.

- Screening: Titles and abstracts were reviewed for thematic relevance to Digital Twin governance and EU digital-law domains, reducing the corpus to 114 documents.

- Eligibility: Full-text analysis assessed legal status, scope, and relevance to cross-sectoral data, AI, or cybersecurity governance. Documents failing to meet these criteria (e.g., national implementations or purely technical standards) were excluded.

- Inclusion: Six principal instruments met all criteria and constitute the analytical core of this study:

- ○

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679)

- ○

- Data Governance Act (DGA, Regulation (EU) 2022/868)

- ○

- Data Act (DA, Regulation (EU) 2023/2854)

- ○

- Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA, Regulation (EU) 2024/1689)

- ○

- NIS2 Directive (Directive (EU) 2022/2555)

- ○

- Cyber Resilience Act (CRA, Regulation (EU) 2024/XXXX)

The selection process is summarised in Figure 1, which presents the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram adapted for legal-document reviews. The diagram details the number of records identified, screened, excluded, and retained for qualitative synthesis, thereby ensuring transparency and reproducibility of the review process. The following counts reflect document flow through each stage: 910 records identified; 910 screened after duplicates removed; 129 reports sought for retrieval; 114 assessed for eligibility; 6 primary legal instruments analysed and included.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram for EU regulations related to Digital Twins.

2.2.4. Analytical Coding and Synthesis

Each included instrument was examined using a structured coding and charting scheme. Articles, recitals, and annexes were coded according to objectives, obligations, and implications for seven thematic dimensions: data governance, privacy, cybersecurity, accountability, interoperability, transparency, and ethics. Coded data were recorded in a comparative matrix noting article number, legal objective, compliance obligation, and technical implication. Thematic synthesis identified overlaps, complementarities, and inter-dependencies among the six acts. This cross-law synthesis generated a comprehensive matrix of obligations that served as the empirical foundation for developing the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF) described in Phase 2.

2.2.5. Literature Scoping for Methodological Novelty

In parallel with the legal mapping, a targeted literature scoping established whether comparable methodological frameworks had been proposed in peer-reviewed articles. This complementary search ensured that the UDTCF developed here represents a novel contribution rather than a reformulation of existing approaches. The literature scoping followed the same procedural discipline as the legal review but focused exclusively on academic sources addressing compliance or governance methodologies for Digital Twin systems under EU law.

Searches covered Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink, spanning 2018–2025 to capture the period when Digital Twin research matured alongside the evolution of EU digital legislation. Combined search terms included “Digital Twin”, “compliance framework”, “data governance”, “AI Act”, “GDPR”, “Data Act”, and “EU regulation”.

Results were screened by title, abstract, and keywords to identify studies proposing conceptual or operational frameworks for regulatory compliance in Digital Twins or related cyber-physical systems. Exclusions covered papers confined to technical architectures or sector-specific use without regulatory analysis. The final corpus comprised 9 publications showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Related literature covering comparable methodological frameworks.

The analysis of the article in Table 1 showed that existing studies treat individual legal instruments in isolation, most often the GDPR or Data Act, without integrating the six major EU laws into a single, cross-sectoral compliance model. Hence, existing frameworks address individual domains and lack a comprehensive legal–technical synthesis applicable across sectors. This confirmed the methodological novelty of both the UDTCF and its companion instrument, the Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM), establishing the study’s unique contribution to legal scholarship and Digital Twin research.

2.3. Phase 2: Framework Development

Building on the regulatory corpus identified through the PRISMA-ScR process, the second phase developed a unified framework translating complex and overlapping EU obligations into an integrated compliance model for Digital Twin systems. This phase applied a design-science logic, combining deductive legal synthesis with inductive conceptual modelling to derive a normative, technical, and organisational framework relevant across multiple domains of deployment.

2.3.1. Conceptual Modelling Process

The framework development process began with a comparative analysis of the six legal instruments identified in Phase 1: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Governance Act (DGA), the Data Act (DA), the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA), the NIS2 Directive, and the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA). Each act was decomposed in phase 1 into coded provisions corresponding to specific legal obligations and governance principles. Cross-law analysis then identified convergent themes and dependencies, such as data-access governance, privacy-by-design, risk management, cybersecurity resilience, and transparency of artificial intelligence systems. Through iterative synthesis, these recurring themes were abstracted into seven meta-categories representing the fundamental compliance domains for Digital Twin systems:

- Data Governance and Access Control

- Data Protection and Privacy

- Cybersecurity and Resilience

- Accountability and Risk Management

- Transparency and Trust

- Interoperability and Standardisation

- Ethical and Social Responsibility

Together, these meta-categories form the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF), which establishes a consolidated structure linking legal requirements to the architectural, procedural, and ethical dimensions of Digital Twin design and operation.

2.3.2. Framework Structuring and Operationalisation

Once the seven meta-categories were defined, their constituent legal and technical obligations were mapped against the functional architecture of Digital Twin systems, data acquisition, modelling, communication, synchronisation, and service layers, to establish direct correspondence between regulatory provisions and system components. This mapping ensured that each compliance domain could be operationalised through measurable technical and organisational mechanisms.

To facilitate systematic evaluation, the UDTCF was translated into a structured analytical instrument, the Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM). The DTCEM converts each meta-category into a set of qualitative indicators and defines a four-level compliance scale: Non-Compliant, Partially Compliant, Compliant, and Fully Compliant, enabling assessment of compliance maturity in research and innovation projects. This operationalisation bridges normative legal interpretation and practical engineering implementation, creating a replicable framework for assessing lawful and trustworthy Digital Twin design.

2.4. Phase 3: Framework Validation Through Case Application

The interpretive validity and practical relevance of the UDTCF and DTCEM were tested on representative European Digital Twin initiatives across four sectors: Smart Cities, Industrial Manufacturing, Mobility and Transportation, and Energy Systems. Case identification followed a transparent, multi-source procedure drawing from the CORDIS database, the Smart Cities Marketplace, and institutional or industrial repositories. Supplementary searches covered national and regional innovation portals such as the European Energy Research Alliance and the Digital Europe Programme directory. A total of 45 candidates were identified and screened against four inclusion criteria:

- A clearly defined Digital Twin concept with public documentation;

- Association with one of the four target sectors;

- Availability of sufficient legal, organisational, and technical evidence for DTCEM assessment;

- Explicit alignment with EU digital-policy objectives.

Twelve cases, three per sector, fulfilled all criteria and together represent a balanced cross-section of European Digital Twin practice. Each case was evaluated against the seven meta-categories of the DTCEM using the four-level scale. Evidence derived from project deliverables, institutional reports, and policy frameworks. To ensure analytical consistency, all assessments were independently reviewed by both authors, providing cross-validation of interpretation and reducing subjectivity in qualitative scoring. This validation procedure confirmed that the UDTCF offers a coherent structure for integrating overlapping EU requirements into the technical and organisational lifecycle of Digital Twins. The results of this evaluation are presented in Section 5, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8, which detail sector-specific compliance assessments.

2.5. Rationale for the Multi-Phase Approach

The three-phase methodology: legal scoping, framework development, and empirical evaluation, captures the multidisciplinary nature of Digital Twin research at the intersection of law, governance, and cyber-physical engineering. The scoping phase establishes a verifiable regulatory corpus through the PRISMA-ScR procedure, ensuring transparency, completeness, and traceability. The framework-development phase transforms this corpus into a structured compliance model bridging legal norms and technical design, thereby advancing the field of compliance-by-design. The evaluation phase verifies the framework’s empirical relevance by applying it to real-world cases across Europe’s strategic digital and green-transition sectors. Together, these phases form a continuous methodological cycle linking normative governance with practical engineering. The approach extends beyond conventional legal analysis by providing a reproducible pathway for designing, testing, and validating compliance frameworks within the European digital ecosystem.

3. EU Laws and Digital Twins

In the European Union, a robust and evolving framework of laws governs data protection, artificial intelligence, data sharing, and cybersecurity, all of which directly impact the design and operation of digital twin systems. The multidimensional architecture of Digital Twins—spanning data acquisition, model-based analytics, connectivity, and actuation—means that each functional layer intersects with a specific area of legal oversight. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) safeguards personal data and privacy, while the Data Governance Act and the Data Act define conditions for secure, fair, and interoperable data sharing across organisations and sectors. The Artificial Intelligence Act introduces obligations for transparency, risk management, and accountability of AI-driven components. The NIS2 Directive and the Cyber Resilience Act impose requirements for cybersecurity, system integrity, and secure product design. Together, these instruments create an interdependent compliance landscape that digital twin developers and adopters must navigate. European regulators aim to ensure transparency, privacy, safety, and security in these emerging technologies, yet organisations often face uncertainty in interpreting how general legal principles apply to the novel context of digital twins, from questions of data ownership and consent to liability for algorithmic decisions. The following sections examine these six legal instruments in detail, outlining how their provisions collectively shape the lawful and trustworthy deployment of digital twin systems within the European Union.

3.1. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) establishes the legal framework for the protection of personal data and the free movement of such data within the European Union. It replaces Directive 95/46/EC and constitutes a binding legal instrument directly applicable in all Member States. The Regulation aims to ensure a consistent and high level of protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data while safeguarding the fundamental rights and freedoms enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. It further seeks to harmonise the conditions for lawful data processing across the Union and to strengthen the principles of accountability, transparency, and individual control over personal information.

The Regulation is structured into eleven chapters that set out the principles, rights, and obligations governing the processing of personal data. Its provisions define the responsibilities of controllers and processors, specify the legal bases for processing, and establish mechanisms for supervisory oversight and enforcement. The Regulation also outlines the rights of data subjects, including access, rectification, erasure, and portability, and introduces safeguards for automated decision-making and data transfers beyond the Union.

Although the General Data Protection Regulation contains ninety-nine articles in total, certain provisions constitute its essential core. These define the scope, fundamental principles, and lawful grounds for processing, as well as the mechanisms ensuring compliance, accountability, and protection of data subjects’ rights. The most important articles can be grouped according to their regulatory function: general provisions defining the scope and applicability of the Regulation; substantive provisions articulating the principles and conditions of lawful processing; procedural provisions detailing data subject rights and controller obligations; and enforcement provisions establishing governance, remedies, and penalties.

Table 2 presents a structured overview of these key articles, outlining their titles, central obligations, and relevance within the overall regulatory framework. To enhance the practical applicability of this overview, a third column summarises the implications for compliance in research and innovation projects that involve complex data processing environments, such as those applying Digital Twins, artificial intelligence, or advanced information systems. This integrated presentation links the legal principles of the Regulation with the operational and technical considerations essential for ensuring conformity in data-driven research and innovation activities.

Table 2.

Overview of the most important articles of the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and their implications for compliance in research and innovation projects.

The synthesis presented in Table 2 illustrates how the General Data Protection Regulation forms an integrated legal and operational framework for data governance, connecting principles of lawfulness, transparency, and accountability to technical and procedural practices. To further support the implementation of these principles in digital and data-driven research contexts, Table 3 extends this overview by summarising the technical compliance requirements that are particularly relevant to system architecture, data interfaces, interoperability, and cloud portability. This complementary table translates the legal provisions into actionable design and deployment criteria for developing and maintaining compliant data processing environments.

Table 3.

Key regulatory requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and their implications for Digital Twin system design.

The combination of Table 2 and Table 3 provides a coherent view of the General Data Protection Regulation from both legal and technical perspectives. It links the normative foundations of data protection law to concrete architectural, procedural, and governance requirements, supporting a systematic approach to compliance-by-design in complex, data-intensive research and innovation environments.

3.2. Data Governance Act (DGA)

The Data Governance Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/868) constitutes one of the principal legal instruments of the European Union’s data strategy, establishing a harmonised framework for the secure, fair, and transparent exchange and re-use of data across Member States. The Regulation aims to increase trust in data sharing mechanisms, enhance the availability of data for economic, scientific, and public interest purposes, and strengthen the Union’s capacity to build a competitive and human-centric data economy. By setting common rules for data intermediation, data altruism, and the re-use of protected public sector data, the Act introduces a governance architecture that ensures lawful, ethical, and traceable data flows within the internal market while safeguarding fundamental rights and data protection.

The Regulation does not create new obligations to share data but provides a consistent governance framework to facilitate voluntary and responsible data exchange. It complements the General Data Protection Regulation and the Data Act by operationalising the principles of transparency, neutrality, accountability, and interoperability in data use. The Act’s provisions ensure that both personal and non-personal data are shared in a trustworthy environment, mediated through neutral intermediaries and safeguarded by strong institutional oversight.

The core provisions of the Data Governance Act can be grouped according to their objectives and relevance for data governance and compliance. These include the re-use of protected public sector data (Articles 3–9), the regulation of data intermediation services (Articles 10–15), the framework for data altruism (Articles 16–25), the designation of competent authorities (Articles 26–28), the establishment of the European Data Innovation Board (Articles 29–30), and the safeguards for international data transfers (Article 31). Collectively, these provisions form a structured and enforceable foundation for transparent data governance across the Union, promoting interoperability and trust in cross-border data transactions.

Table 4 provides a structured summary of the most important Articles of the Data Governance Act. It outlines the title, key obligations, and relevance of each Article while including an additional column that summarises their implications for compliance in research and innovation projects such as those involving digital twins, artificial intelligence, or smart data ecosystems.

Table 4.

Summary of the most important Articles of the Data Governance Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/868) and their implications for compliance in research and innovation projects.

While Table 4 presents the structural and legal interpretation of the Regulation, Table 5 translates these legal requirements into a set of technical compliance measures relevant for data-intensive system architectures. It highlights the specific technical dimensions of compliance such as interoperability, secure data interfaces, cloud portability, and auditability that must be incorporated into digital infrastructures to ensure conformity with the Act.

Table 5.

Technical compliance requirements derived from the Data Governance Act and their implications for Digital Twin system design.

Together, these tables provide an integrated overview of the Data Governance Act’s legal and technical dimensions. They illustrate how the Regulation establishes not only a governance framework for lawful data exchange but also a set of architectural and procedural benchmarks for trustworthy, transparent, and interoperable data systems within the European digital ecosystem.

3.3. Data Act (DA)

The Data Act (Regulation (EU) 2023/2854) establishes a comprehensive legal framework for ensuring fairness, transparency, and accountability in the access to and use of data within the European Union. Adopted in December 2023, it complements the existing EU digital regulatory architecture by introducing harmonised rules that define rights and obligations related to data sharing, interoperability, and the protection of lawful access. The Regulation seeks to promote a balanced data economy in which data generated by connected products and related services can be accessed and reused under fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory conditions, thereby enhancing innovation while safeguarding legitimate interests such as data protection, trade secrets, and cybersecurity.

The Regulation applies horizontally across sectors and covers both personal and non-personal data. It defines the roles of users, data holders, and data recipients, establishes mechanisms for public sector access to privately held data in cases of exceptional need, and sets principles for switching between data processing services. Furthermore, it provides technical and organisational requirements to guarantee interoperability between systems, ensure lawful international data transfers, and introduce safeguards against unfair contractual practices in data-related agreements.

The most significant provisions of the Data Act can be grouped according to their thematic focus and regulatory intent. The general provisions (Articles 1–2) define the scope of application and establish key terminology that underpins the legal interpretation of the Regulation. The data access and sharing provisions (Articles 3–7) introduce the principle of data accessibility by design and outline the rights of users to access, use, and share data generated by connected products and services. The business-to-business fairness rules (Articles 8–13) require that data be shared on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory terms and prohibit the imposition of unfair contractual conditions. The public-interest data access provisions (Articles 14–21) permit the use of privately held data by public authorities and EU institutions under specific and proportionate conditions in situations of exceptional need.

The rules on data processing and cloud switching (Articles 23–31) establish obligations for providers of data processing services to remove technical and contractual barriers to data portability and to ensure functional equivalence following service migration. The interoperability and international access provisions (Articles 32–36) introduce safeguards against unlawful access to non-personal data by third countries, define interoperability requirements for data exchange and common data spaces, and prescribe essential conditions for smart contracts used in automated data sharing. Finally, the implementation and enforcement framework (Articles 37–50) mandates Member States to designate competent authorities, defines cooperation mechanisms, introduces proportionate penalties for non-compliance, and sets timelines for the gradual application of the Regulation from September 2025 onward.

Together, these provisions form the foundation of the European Union’s data governance regime by delineating clear responsibilities among data actors, ensuring interoperability of digital infrastructures, and fostering trust in the lawful and equitable use of data.

The following Table 6 provides an overview of the most important articles, grouped according to their legal function and relevance for compliance. It highlights the regulatory purpose of each provision and identifies its implications for research and innovation projects relying on data-driven technologies such as digital twins and artificial intelligence.

Table 6.

Key Articles of the EU Data Act and Implications for Compliance in Research and Innovation Projects.

While Table 6 defines the legal and governance framework of the Data Act, effective compliance depends on its translation into technical system design and operational processes. Table 7 summarises the technical compliance requirements that arise from the Regulation’s provisions, focusing on data accessibility, interoperability, portability, and lawful use within digital infrastructures. It identifies the system-level mechanisms, architectural decisions, and procedural controls necessary to operationalise the Regulation’s principles within research and innovation environments that rely on distributed data and computational resources.

Table 7.

Technical Compliance Requirements for Digital Twin Systems under the EU Data Act.

3.4. Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA)

The Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) establishes a harmonised legal framework governing the development, placement on the market, and use of artificial intelligence within the European Union. The Act represents the first comprehensive regulatory instrument addressing the opportunities and risks associated with artificial intelligence, ensuring that its deployment is consistent with the Union’s fundamental values, human rights, and principles of transparency, accountability, and safety. Its objective is to create the conditions for trustworthy and human-centric artificial intelligence that fosters innovation while safeguarding public interests and the integrity of the internal market.

The structure of the regulation follows a risk-based approach that differentiates obligations according to the level of potential harm associated with an artificial intelligence system. It defines the categories of unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal risk and establishes specific requirements for each. The most significant provisions concern the identification of high-risk artificial intelligence systems, the establishment of technical and organisational safeguards, and the introduction of transparency and oversight obligations to ensure responsible design, development, and deployment.

Core obligations under the Act encompass the establishment of comprehensive risk management frameworks, the implementation of data governance and documentation requirements, and the enforcement of standards for transparency, accuracy, robustness, and human oversight. The regulation further defines the responsibilities of all actors in the artificial intelligence value chain, including providers, importers, distributors, and deployers, and sets out conformity assessment procedures to verify compliance before systems are placed on the market. It also introduces governance structures at both national and Union levels through the creation of the European Artificial Intelligence Board and the AI Office, which coordinate oversight, guidance, and enforcement.

In addition, the Act introduces specific provisions for general-purpose artificial intelligence models, mandates the establishment of regulatory sandboxes to support innovation under supervision, and defines a consistent penalty regime proportionate to the severity of non-compliance. Collectively, these elements form the legal foundation for the trustworthy and responsible integration of artificial intelligence across applications and contexts within the European Union.

To clarify the structure of the regulation and its key obligations, Table 8 presents a detailed overview of the most important articles of the Artificial Intelligence Act. The table groups the articles according to their objectives and relevance for compliance, governance, and risk management, while the final column identifies the implications for compliance in research and innovation projects involving artificial intelligence, digital twins, or other advanced system architectures. This extended interpretation allows for a deeper understanding of how the regulation informs the design and documentation of intelligent digital systems developed within research and innovation frameworks.

Table 8.

Summary of Core Articles of the Artificial Intelligence Act and Implications for Research and Innovation Compliance.

To further support digital twin developers in interpreting and operationalising the Artificial Intelligence Act, Table 9 reformulates the same key provisions into a condensed format that emphasises compliance awareness and practical implementation. The table is designed to guide development teams, research consortia, and system architects in understanding how each article translates into procedural and technical responsibilities during the design, testing, and deployment of digital twin systems that incorporate artificial intelligence components. It thereby serves as a pedagogical and organisational tool for integrating regulatory compliance into the full lifecycle of digital twin development and innovation.

Table 9.

Regulatory Requirements of the Artificial Intelligence Act and Their Implications for Digital Twin Design.

Together, these tables provide a structured foundation for understanding the Artificial Intelligence Act. They collectively bridge the regulatory text and its operational interpretation, offering both analytical depth for researchers and practical guidance for educators and compliance practitioners.

3.5. NIS 2 Directive (Network and Information Systems Security Directive)

The Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council, known as the NIS 2 Directive, establishes a comprehensive framework for achieving a high common level of cybersecurity across the European Union. It replaces the original NIS Directive (EU) 2016/1148 and introduces a harmonised and more stringent regulatory regime designed to strengthen the resilience of network and information systems that underpin essential and important services within the internal market. The Directive defines the legal and organisational foundations for national cybersecurity governance, extends its scope to a broader range of entities, and reinforces supervisory and enforcement mechanisms to ensure consistent implementation among Member States.

The NIS 2 Directive is structured around several fundamental objectives that collectively ensure a unified and risk-based approach to cybersecurity management. It first establishes the general provisions, scope, and definitions that determine its applicability, classification of entities, and relationship with other Union legal instruments. It then defines the national and Union-level governance architecture, requiring Member States to adopt cybersecurity strategies, designate competent authorities, and establish computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) to coordinate preparedness and response activities. Furthermore, it sets out harmonised cybersecurity risk-management measures and detailed incident-reporting obligations, providing a consistent procedural and technical framework for compliance. At the Union level, it enhances cooperation through structured mechanisms such as the Cooperation Group, the CSIRTs network, and the European Cyber Crisis Liaison Organisation Network (EU-CyCLONe). Finally, it reinforces supervision, enforcement, and sanctioning powers, ensuring accountability and uniform application of cybersecurity requirements across the Union.

Table 10 summarises the most important Articles of the NIS 2 Directive, grouped by their objectives and regulatory significance. Each Article is accompanied by its title, key obligation, relevance, and implications for compliance in research and innovation contexts such as digital twin platforms, artificial intelligence systems, and smart building infrastructures. The table provides a concise reference for understanding how the Directive’s legal requirements translate into compliance obligations for organisations engaged in the design, development, and deployment of digital technologies.

Table 10.

Summary of Key Articles in the NIS 2 Directive and their Relevance for Digital Twin Research and Innovation.

Table 10 provides a regulatory overview that links each Article of the NIS 2 Directive to its operational significance for research and innovation environments. While the table emphasises Digital Twin development as a representative domain, its implications extend to any complex digital system architecture subject to the Directive’s provisions.

Building on this, Table 11 translates the legal and organisational provisions of the NIS 2 Directive into specific technical compliance requirements relevant to system architecture, data exchange, interoperability, and cloud portability. It serves as a practical mapping between the Directive’s legal obligations and the technical design principles that ensure conformity within distributed and data-driven digital infrastructures.

Table 11.

Technical Compliance Requirements of the NIS 2 Directive Relevant to Digital Twin System Architecture.

Together, Table 10 and Table 11 provide a structured understanding of the NIS 2 Directive as both a legal and a technical instrument for cybersecurity governance. They demonstrate how regulatory provisions are operationalised within digital infrastructures, supporting the systematic alignment of organisational processes, data governance, and system design with the Directive’s overarching objective of ensuring a common and resilient cybersecurity posture across the European Union.

3.6. Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)

The Cyber Resilience Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/XXXX) constitutes a cornerstone of the European Union’s cybersecurity legislation, aiming to ensure a uniformly high level of cyber resilience across all products with digital elements made available on the Union market. It introduces harmonised requirements that apply to both hardware and software throughout their entire lifecycle, from design and development to production, maintenance, and end-of-life. By establishing common obligations for manufacturers, importers, and distributors, the Regulation seeks to safeguard the internal market against systemic digital vulnerabilities and to enhance the overall trustworthiness of the digital ecosystem.

The Regulation applies to a broad spectrum of products with digital elements and defines mandatory cybersecurity requirements based on the principles of security-by-design and security-by-default. These principles ensure that security considerations are integrated from the earliest stages of product conception and continuously maintained through vulnerability management and post-market monitoring. The Cyber Resilience Act introduces a structured governance model that defines responsibilities for all economic operators in the supply chain. Manufacturers are required to conduct risk assessments, implement secure development processes, and ensure conformity before products are placed on the market. Importers and distributors must verify compliance and cooperate with supervisory authorities.

To ensure proportionality and coherence, the Act differentiates between products according to their risk level and establishes corresponding conformity assessment procedures. This tiered approach balances the need for high security assurance with the importance of promoting innovation and reducing administrative burdens. National authorities are empowered to conduct audits, enforce corrective measures, and impose sanctions in cases of non-compliance, while the European Commission and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) coordinate the implementation of technical standards and regulatory updates. Through this structure, the Act combines preventive security design with enforceable oversight mechanisms to strengthen cyber resilience across the Union.

The most significant provisions of the Cyber Resilience Act can be grouped according to their regulatory objectives and implementation focus. Table 12 presents an overview of the Regulation’s most important articles, highlighting their main obligations, relevance, and specific implications for compliance in research and innovation projects involving digital technologies such as digital twins, artificial intelligence, or intelligent systems.

Table 12.

Summary of the Most Important Articles of the Cyber Resilience Act.

Beyond the legal and procedural aspects, the Cyber Resilience Act also establishes technical compliance requirements that define how cybersecurity must be implemented in complex digital architectures. These requirements are particularly relevant to systems that integrate interconnected components, distributed data infrastructures, and cloud-based environments. They cover interoperability, data integrity, secure communication, cloud portability, and resilience across system interfaces. Table 13 presents a structured synthesis of the Act’s technical compliance dimensions, linking specific articles to the architectural and engineering considerations that underpin cybersecurity-by-design in advanced digital systems.

Table 13.

Technical Compliance Requirements under the Cyber Resilience Act Relevant to Digital Twin System Architecture.

Together, these two tables illustrate how the Cyber Resilience Act provides both a regulatory foundation and a technical framework for ensuring the cybersecurity of digital systems. The Regulation establishes legal obligations for conformity, accountability, and enforcement, while simultaneously defining precise technical expectations for secure interoperability and resilience. It therefore forms a comprehensive framework for guiding compliance in the design, operation, and governance of interconnected digital environments within the European Union.

4. Towards a Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework

4.1. Rationale for Integration of EU Digital Regulations

The preceding sections have demonstrated that the European regulatory environment governing Digital Twin systems is both comprehensive and multifaceted. Each of the six legal instruments—the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Governance Act (DGA), the Data Act, the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), the NIS2 Directive, and the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)—introduces distinct objectives, terminologies, and compliance mechanisms. While together they form the foundation for trustworthy and secure data-driven innovation within the European Union, their concurrent application creates an intricate compliance landscape that is difficult for technology developers to operationalise in practice. The overlapping scopes of these laws mean that a single Digital Twin may simultaneously be classified as a data controller, an AI provider, a data holder, and an operator of an essential digital service. Consequently, even small design decisions, such as which data to collect, how to share it, or how to manage security updates, can trigger multiple legal obligations across different regulatory domains.

This fragmentation leaves developers and research organisations with the challenge of navigating six sets of requirements that must be satisfied concurrently during the design, development, deployment, and operation of a Digital Twin. Without a structured compliance framework, it becomes nearly impossible to maintain traceability between legal obligations and their corresponding technical implementations. The risk is not only non-compliance but also reduced innovation capacity, as excessive legal uncertainty discourages experimentation and cross-sectoral data use. This underscores the need for an integrated approach that aligns the requirements of EU data, AI, and cybersecurity legislation into a coherent methodology that developers can follow systematically throughout the Digital Twin lifecycle.

4.2. Conceptual Basis of the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF)

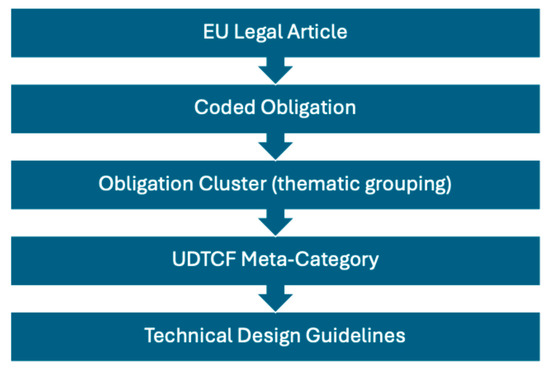

To address this challenge, a unified digital twin compliance framework (UDTCF) is proposed. The framework consolidates the principal obligations derived from the six EU legal acts into a single, harmonised matrix of meta-categories that groups requirements according to shared compliance domains. This approach enables developers to assess, implement, and document compliance-by-design measures holistically rather than separately for each regulation. The framework serves as both a conceptual map for legal alignment and a practical design tool for developers working on Digital Twins intended for the European market. The creation of the UDTCF followed a structured legal-to-technical mapping process, shown in Figure 2, where each article of each regulation was first coded for objective, obligation type, and technical implication (Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6). Then these coded obligations were thematically grouped through an inductive process into the seven meta-categories. For example, GDPR Article 22 prohibits solely automated decision-making that produces legal or significant effects on individuals. The coding process identifies obligations related to human oversight, transparency, and explainability. These were assigned to three meta-categories of the UDTCF: Data Protection and Privacy, Accountability and Risk Management, and Transparency, Explainability and Trust. Technical implications include implementing human-in-the-loop review mechanisms, explainable-model interfaces, and decision-logging capabilities within the Digital Twin workflow.

Figure 2.

Deriving Meta-Categories from EU Regulatory Obligations.

Table 14 provides the synthesis of the key compliance requirements of the GDPR, DGA, Data Act, AI Act, NIS2 Directive, and CRA into the seven meta-categories: Data Governance and Access Control, Data Protection and Privacy, Cybersecurity and System Resilience, Accountability and Risk Management, Transparency and Trust, Interoperability and Standardisation, and Ethical and Social Responsibility. Together, these meta-categories capture the cumulative compliance logic of EU law as it applies to Digital Twin systems, establishing a unified compliance model that links legal provisions to the technical and organisational layers of system design.

Table 14.

Integrated EU Compliance Framework for Digital Twin Systems under EU Law.

4.3. Technical Implementation Guidelines for Compliance-by-Design

While Table 14 provides a consolidated mapping of obligations across EU legislation, its utility for practitioners increases when complemented with explicit design guidance. Table 15 therefore operationalises the seven meta-categories of the UDTCF by linking them to concrete design and deployment measures that Digital Twin developers can apply directly. It converts the legal and ethical requirements of EU law into actionable technical principles that govern data governance, security, transparency, and interoperability throughout the Digital Twin lifecycle. In this way, the framework bridges the conceptual layer of legal interpretation with the engineering layer of compliance implementation.

Table 15.

Technical Compliance Implications for Digital Twin Systems under EU Law.

This unified framework transforms the complexity of European digital regulation into a structured methodology for lawful, secure, and interoperable Digital Twin development. It allows developers to identify compliance dependencies early, document regulatory evidence consistently, and integrate technical safeguards systematically across all system layers. By embedding these principles into the engineering process, Digital Twin developers can align innovation with European legal and ethical standards, thereby ensuring that Digital Twin solutions are market-ready, trustworthy, and compliant within the evolving European data and AI ecosystem.

4.4. The Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM)

While the UDTCF provides a structured synthesis of legal and technical obligations under the six major EU laws, practical assessment of compliance in real-world Digital Twin projects remains a significant challenge. Many Digital Twins are documented in scientific articles, research deliverables, or technical reports, but their degree of legal and ethical compliance is rarely assessed systematically. The complexity of the European regulatory environment, combined with the multidisciplinary nature of Digital Twin systems, makes it difficult to determine whether a specific implementation conforms to the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Governance Act (DGA), the Data Act, the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), the NIS2 Directive, and the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA).

To address this challenge, a Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM) is proposed, as shown in Table 16. The DTCEM extends the compliance framework and technical implications presented in Table 14 and Table 15 by translating each compliance domain into a set of measurable evaluation indicators that can be applied to existing Digital Twin projects. It provides a structured instrument for assessing how well a Digital Twin system aligns with EU legal requirements across the seven meta-categories defined in the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF).

Table 16.

Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM).

Unlike quantitative assessment tools, this matrix uses qualitative compliance levels that capture the degree to which the Digital Twin demonstrates conformity with lawful obligations and best practices. Each meta-category is evaluated using a four-level qualitative scale as listed in Table 17.

Table 17.

Four-level qualitative evaluation scale.

These four qualitative levels provide clear interpretability for compliance audits while allowing flexibility for research-oriented evaluations that involve systems still under development.

The DTCEM bridges the gap between regulatory theory and engineering practice by transforming the complex legal environment into measurable, evidence-based compliance indicators. When used together with the unified framework, it enables Digital Twin developers and researchers to demonstrate conformity with EU law systematically, fostering trustworthy and lawful innovation within the European Digital Single Market.

4.5. Evaluation Procedure and Application Contexts

The DTCEM provides a practical methodology for evaluating Digital Twin systems in both research and industrial settings. Its application follows a structured five-step process designed to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and comparability across projects.

- Step 1—Definition of Evaluation Scope: The evaluator begins by clearly defining the scope and boundaries of the Digital Twin to be assessed. This includes identifying the system’s purpose, operational environment, and interfaces with external data or control systems. For complex projects, such as multi-domain or federated Digital Twins, the scope should be decomposed into logical subsystems (for instance, data acquisition, analytics, or control layers) to enable targeted evaluation within each compliance domain.

- Step 2—Evidence Collection: For each meta-category of the DTCEM, relevant evidence must be gathered to substantiate the compliance assessment. Acceptable evidence includes technical documentation, organisational policies, legal artefacts, and operational records such as incident logs or audit trails. This ensures traceability and transparency in compliance evaluation.

- Step 3—Qualitative Assessment: Each meta-category is evaluated qualitatively using the four compliance levels: Non-Compliant (NC), Partially Compliant (PC), Compliant (C), or Fully Compliant (FC). The evaluator assigns a rating based on the strength and completeness of the supporting evidence and the extent to which the system meets the lawful requirements listed in the UDTCF. The process is deliberative rather than mechanical, encouraging expert judgement from both legal and technical perspectives.

- Step 4—Documentation and Review: All assessments and evaluator notes must be documented to support internal review and external verification. Documentation includes the rationale for each compliance level, references to supporting evidence, identified compliance gaps, and recommended corrective actions. The resulting dossier can serve in project reporting, certification alignment, or ethics board submissions.

- Step 5—Synthesis and Reporting: After completing the evaluation, the findings are synthesised into a compliance summary that highlights both strengths and deficiencies across meta-categories. Instead of numerical aggregation, the synthesis relies on interpretive reasoning. Systems may, for instance, be classified as

- ○

- Legally Critical—containing one or more Non-Compliant (NC) domains that require immediate remediation.

- ○

- Conditionally Acceptable—mostly Partially Compliant (PC), suitable for research pilots but not for operational deployment.

- ○

- Legally Robust—predominantly Compliant (C) or Fully Compliant (FC), suitable for deployment within the EU regulatory framework.

This qualitative synthesis enables decision-makers to prioritise compliance improvements and communicate the project’s legal readiness level transparently. The evaluation process can be applied manually by a legal–technical expert panel or semi-automatically through natural language analysis of Digital Twin documentation. It supports comparative studies, benchmarking of Digital Twin projects across sectors, and alignment of research outputs with EU policy objectives. Moreover, it provides a transparent and reproducible method for identifying gaps in privacy, security, and interoperability before deployment or certification.

The DTCEM thereby bridges the gap between regulatory theory and engineering practice by transforming the complex legal environment into measurable, evidence-based compliance indicators. When used together with the unified framework (Table 14 and Table 15), it enables Digital Twin developers and researchers to demonstrate conformity with EU law systematically, fostering trustworthy and lawful innovation within the European Digital Single Market.

The subsequent sections apply the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF) and the Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM) to four strategic sectors: Smart Cities, Industrial Manufacturing, Mobility and Transportation, and Energy Systems. Each sectoral analysis evaluates representative European initiatives across the seven meta-categories defined in the UDTCF, using the four-level qualitative compliance scale described in Table 17. This consistent methodological approach ensures comparability among the twelve cases examined and enables cross-sectoral synthesis of compliance maturity presented in Section 9.

5. Digital Twins in Smart Cities

5.1. Sector Overview

Digital Twins have become foundational instruments in the digital transformation of European cities. Urban Digital Twins integrate data from infrastructure, transport, environment, and citizen services into a virtual representation of the urban fabric that supports real-time analysis, simulation, and policy evaluation. By interlinking geographic information systems, IoT sensor networks, and AI-driven analytics, these platforms enable planners and operators to monitor and optimise the functioning of complex urban systems. Their functions range from dynamic traffic management and energy-efficient building operations to climate adaptation modelling and participatory urban design.

At the municipal level, Digital Twins are deployed as decision-support tools that facilitate cross-departmental coordination and transparency in urban governance. The European Commission’s initiatives on Local Digital Twins, the Living-in. EU movement [37], and the Mission on Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities [38] have further encouraged cities to adopt these technologies to achieve the objectives of the European Green Deal [39] and Digital Decade Policy Programme [40]. Consequently, Smart City Digital Twins constitute not only a technological evolution but also a governance innovation, embodying the integration of real-time data, citizen engagement, and predictive policy analysis within a shared digital infrastructure.

5.2. Regulatory Relevance

The governance of Smart City Digital Twins intersects with nearly all major EU digital laws identified in this review. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is central because urban Digital Twins continuously process location, environmental, and behavioural data that may qualify as personal or indirectly identifiable information. Ensuring data minimisation, lawful basis for processing, and transparency in citizen data use is therefore essential.

The Data Governance Act (DGA) and the Data Act are equally critical since municipal Digital Twins rely on data sharing among public authorities, utilities, private companies, and citizens. These laws define how public-sector data may be reused, how data intermediation services must operate, and how interoperability and contractual fairness are guaranteed.

The Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) applies to the AI models embedded within Digital Twins that generate predictions, perform anomaly detection, or support decision-making in areas such as traffic control and energy distribution. Depending on their function, such systems may be classified as high-risk AI under the AIA, triggering obligations related to transparency, documentation, and human oversight.

The NIS2 Directive and Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) establish cybersecurity and resilience obligations for the infrastructures underpinning Smart City Digital Twins. These instruments require secure-by-design system architecture, vulnerability management, and incident reporting, ensuring that critical city operations remain protected against cyber threats.

Within the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF), Smart City applications primarily activate the following meta-categories: Data Governance and Access Control, Data Protection and Privacy, Cybersecurity and Resilience, and Transparency, Explainability, and Trust. These domains define the legal and technical conditions for trustworthy operation of urban Digital Twins.

5.3. Sectoral Compliance Evaluation

To assess the compliance maturity of Smart City Digital Twins, the Digital Twin Compliance Evaluation Matrix (DTCEM) can be applied to representative European initiatives. Three prominent examples illustrate different governance and technical models: Virtual Helsinki, Smart Dublin, and Rotterdam Urban Twin. Each represents an operational Digital Twin integrating heterogeneous data sources for urban management and citizen services.

Virtual Helsinki [41] demonstrates a strong alignment with GDPR principles through transparent data governance and explicit consent mechanisms in citizen engagement modules [42]. Its privacy-by-design approach and open-access policies indicate clear alignment with the Data Governance Act and the Data Act through licensed open datasets and interoperable APIs [43]. However, full traceability and explainability of AI models in line with the AI Act appear to be still developing in the public documentation, which emphasises datasets and use cases rather than model documentation [44]. The project can be rated as Fully Compliant (FC) for data protection, Compliant (C) for data governance, and Partially Compliant (PC) for AI transparency and documentation.

Smart Dublin [45] employs a distributed data-sharing model connecting city councils, utilities, and research institutions. Its adherence to the Data Governance Act principles of data altruism and neutrality is well established through its open-data portal and governance participation in the Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, which commits to transparent and privacy-by-design data use [46]. However, interoperability of datasets across departments and cloud platforms remains constrained, both of which note that Dublin’s councils operate heterogeneous systems without uniform schemas [47]. Accordingly, Smart Dublin demonstrates Compliant (C) levels for Data Governance, Partially Compliant (PC) for Interoperability and Standardisation, and Compliant (C) for Ethical and Social Responsibility due to its well-documented citizen-participation and open-innovation framework [48,49].

The Rotterdam Urban Twin [50] integrates environmental monitoring and climate resilience functions through city-scale digital infrastructure and AI-enabled analytical models [51,52]. Developed within the city’s Open Urban Platform, it facilitates data exchange across municipal departments and supports predictive simulations for urban sustainability and flood-risk management. The platform’s design aligns with the European NIS2 Directive and Cybersecurity Act through integrated risk-management procedures and adoption of security-by-design principles promoted by ENISA’s cybersecurity frameworks, indicating a high level of operational resilience. Governance and accountability are strengthened through the Centre for Bold Cities, which applies multidisciplinary ethical review and risk analysis in the use of municipal and citizen data [53]. However, ongoing experimentation with machine-learning-based prediction for climate adaptation and mobility scenarios still lacks full explainability documentation, leaving transparency obligations under the Artificial Intelligence Act partially met. Accordingly, the Rotterdam Urban Twin can be assessed as Fully Compliant (FC) for Cybersecurity and Resilience, Compliant (C) for Accountability and Risk Management, and Partially Compliant (PC) for Transparency and Explainability.

A comparative synthesis of these evaluations is shown in Table 18.

Table 18.

Compliance Evaluation of Representative Smart City Digital Twins.

This analysis shows that most European Smart City Digital Twins reach at least Compliant (C) levels across data protection, governance, and cybersecurity dimensions, while Transparency and Explainability remain areas of partial compliance. The trend indicates that although technical and organisational safeguards are increasingly mature, the interpretability and documentation of AI-based urban simulations still require further alignment with the transparency obligations of the Artificial Intelligence Act.

Table 19 provides structured evidence linking each compliance rating in Table 18 to publicly verifiable documentary sources, ensuring methodological transparency in the scoping review process. Each entry lists the relevant documentation and corresponding legal provisions under the six EU acts covered by the Unified Digital Twin Compliance Framework (UDTCF). Together, Table 18 and Table 19 enable cross-validation of compliance assessments and strengthen the evidential basis for sectoral findings discussed in Section 9.

Table 19.

Evidence Alignment between Compliance Evaluation and Documentary Sources.

5.4. Sector-Specific Challenges and Lessons

The application of EU law to Smart City Digital Twins reveals several recurring challenges. First, data protection and anonymisation remain complex because urban data often combine personal and non-personal elements, making complete anonymisation technically difficult without undermining analytical value. Second, interoperability and standardisation continue to be fragmented due to the diversity of municipal data infrastructures and vendor-specific implementations. Third, accountability and human oversight of AI-driven decision systems, such as adaptive traffic control or urban planning simulations, require clearer governance frameworks to comply with the AI Act’s requirements for transparency and oversight.

Nevertheless, European initiatives show growing maturity in integrating compliance-by-design methodologies. The use of federated data spaces allows municipalities to retain data sovereignty while enabling cross-domain analysis in line with the Data Governance Act. Regulatory sandboxes established under the AI Act are emerging as valuable instruments for testing high-risk AI components in controlled environments. Similarly, alignment with European cybersecurity certification schemes under the NIS2 Directive and Cyber Resilience Act enhances trust and resilience in municipal infrastructures.

Overall, Smart City Digital Twins exemplify the convergence of technical innovation and legal responsibility within the European digital ecosystem. Their progressive alignment with EU data, AI, and cybersecurity laws demonstrates a strong trajectory toward lawful, ethical, and interoperable digital governance. However, sustained investment in transparency mechanisms, open standards, and cross-sector collaboration remains essential to achieve full compliance maturity across the European Smart City landscape.

6. Digital Twins in Industrial Manufacturing

6.1. Sector Overview

Digital Twins have become a cornerstone of the digital transformation in industrial manufacturing, underpinning the transition towards smart factories, cyber-physical production systems, and Industry 5.0 [68,69]. Within this context, Digital Twins represent a fusion of operational technology and information technology that enables continuous synchronisation between virtual models and physical assets such as machines, robots, and production lines. They are deployed across the full manufacturing lifecycle: product design, process optimisation, predictive maintenance, and supply-chain coordination. By combining IoT sensor data, physics-based simulations, and AI-driven analytics, they facilitate real-time monitoring, predictive decision-making, and self-adaptive control of production environments.

European manufacturing is a leading domain for Digital Twin innovation, strongly supported by programmes such as Made in Europe [70] and Factories of the Future [71]. Industrial Digital Twins are increasingly embedded in data-driven ecosystems that connect equipment manufacturers, suppliers, and customers through secure and interoperable platforms. Their contribution to resource efficiency, resilience, and circular manufacturing aligns with the European Green Deal [39], the Data Strategy [72], and the Digital Single Market objectives [73].

6.2. Regulatory Relevance

Industrial Digital Twins operate at the intersection of multiple European digital regulations. The Data Act and Data Governance Act are particularly influential because manufacturing data, especially that generated by connected industrial machinery, forms the basis for value creation and innovation. These laws define access rights, interoperability, and fairness in business-to-business data sharing, ensuring that machine-generated data can be reused under transparent and non-discriminatory conditions.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) applies where Digital Twins process human-related data such as operator performance metrics or workplace safety monitoring. The Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) becomes relevant when machine-learning components are used for autonomous optimisation, quality control, or predictive maintenance. Such systems may fall under the high-risk category if they affect human safety or product conformity.