Abstract

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generators (PMSGs) have become increasingly important in industrial applications such as wind turbine systems due to their high efficiency and power density. However, their operational reliability can be affected by asymmetries such as static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB), which exhibit similar spectral features and are therefore difficult to differentiate using conventional techniques such as Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA). Stray flux analysis provides an alternative diagnostic approach, yet single-point measurements often lack the sensitivity required for accurate fault discrimination. This study introduces a diagnostic methodology based on the Space Vector Stray Flux (SVSF) for identifying static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB) faults in PMSG-based systems. The SVSF is derived from three external stray flux sensors placed 120° electrical degrees apart and analyzed through symmetrical component decomposition, focusing on the +5fs positive-sequence harmonic. Two-dimensional Finite Element Analysis (FEA) conducted on a 36-slot/12-pole PMSG model shows that the amplitude of the +5fs harmonic increases markedly under static eccentricity, while it remains nearly unchanged under load current unbalance. To validate the simulation findings, comprehensive experiments have been conducted on a dedicated test rig equipped with high-sensitivity fluxgate sensors. The experimental results confirm the robustness of the proposed SVSF method against practical constraints such as sensor placement asymmetry, 3D axial flux effects, and electromagnetic interference (EMI). The identified harmonic thus serves as a distinct and reliable indicator for differentiating static eccentricity from load current unbalance faults. The proposed SVSF-based approach significantly enhances the accuracy and robustness of fault detection and provides a practical tool for condition monitoring in PMSG.

1. Introduction

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generators (PMSGs) are increasingly utilized in modern electrical power generation owing to their high efficiency and power density relative to traditional induction machines. High torque density and efficient operation across a wide speed range are key factors driving the expanding adaptation of PMSGs [1,2,3]. Developments in permanent magnet materials have expanded the use of PMSGs in safety-critical sectors such as wind turbines, aerospace, and electric vehicles, where high operational reliability is required. Despite these advantages, PMSGs are susceptible to various electrical and mechanical faults. These faults degrade performance, compromise system reliability, and potentially lead to expensive operational failures [4,5]. Therefore, establishing robust condition monitoring and early fault detection methodologies is crucial for ensuring the operational safety, longevity, and sustainability of PMSG-based systems [6].

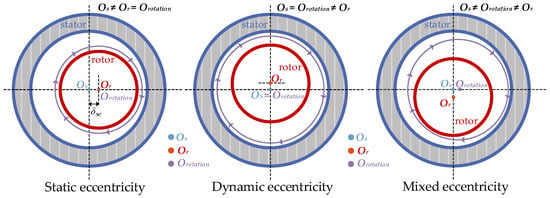

Operational reliability in PMSGs is significantly threatened by mechanical faults, with rotor eccentricity being a particularly prevalent and critical failure mode [7,8]. Eccentricity denotes the misalignment between the rotor’s rotational axis and the stator’s geometric center. This condition typically arises from manufacturing tolerances, assembly errors, or bearing wear. Eccentricity occurs in three main types. In static eccentricity (SE), the rotor’s rotational axis (Orotation) is fixed but displaced from the stator’s geometric center (Os). This condition results in a stationary, non-uniform air gap. For dynamic eccentricity (DE), the rotor’s geometric center (Or) is offset from its axis of rotation (Orotation). This causes the position of the minimum air gap to rotate along with the rotor. Mixed eccentricity (ME) involves a combination of both SE and DE and is the form commonly encountered [9]. Figure 1 illustrates these geometric configurations. Persistent air-gap asymmetry from eccentricity disrupts the magnetic field distribution, generating an unbalanced magnetic pull (UMP). The UMP induces excessive mechanical stress within the machine. This stress consequently causes increased vibration, acoustic noise, and accelerated bearing wear [10,11].

Figure 1.

The structure of static (SE), dynamic (DE), and mixed eccentricity (ME) faults.

Beyond mechanical issues, load current unbalance significantly affects the generator’s dynamic behavior. This operational condition originates from asymmetries in load impedances or anomalies within the power converter [12]. Unbalanced loads induce additional harmonic components in the stator currents, disrupting the generator’s inherent electrical, mechanical, and magnetic symmetries [13]. A critical diagnostic challenge arises because the spectral signatures of these load-induced harmonics can overlap with signatures generated by mechanical faults, particularly static eccentricity [14,15]. This spectral overlap introduces significant diagnostic ambiguity. Consequently, reliably distinguishing between a mechanical fault and an electrical load unbalance becomes difficult using conventional spectral analysis.

To address these diagnostic challenges, various condition monitoring techniques analyzing vibration, stator current, and magnetic flux have been extensively explored in the literature. Among these, Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) is widely adopted due to its non-invasive nature and cost-effectiveness, utilizing existing current sensors for remote monitoring [16]. However, MCSA’s diagnostic reliability is often limited. Fault signatures can be masked by noise, suppressed by the generator’s control strategy, or diminished during non-stationary operations. While advanced signal processing techniques, such as wavelet transforms or higher-order spectra, enhance time-frequency resolution, they remain constrained by the scalar nature of the stator current signal [17]. Since static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB) induce overlapping spectral signatures at identical frequencies, conventional and even advanced current-based methods fail to discriminate between these faults without auxiliary data.

Although vibration analysis offers effective detection of mechanical anomalies, it entails increased hardware complexity and cost due to the requirement for external sensors, which are also susceptible to ambient mechanical noise. More recently, data-driven methods utilizing machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have shown high classification accuracy [18,19]. However, these models have significant drawbacks. Although they can potentially resolve diagnostic ambiguities, they require large, labeled datasets for training, which are rarely available for specific fault scenarios in industrial settings [18,19,20]. Furthermore, they often lack interpretability and face challenges in generalizing across different machine types or unseen operating conditions. Consequently, a deterministic, physics-based indicator that physically decouples these faults is required.

Stray flux monitoring provides a reliable diagnostic alternative by offering direct insight into the machine’s magnetic symmetry and revealing fault-induced anomalies [21]. Magnetic flux can be measured internally within the air gap or externally as stray flux. Internal air-gap flux measurements using embedded search coils or Hall-effect sensors yield precise data but are generally invasive and impractical [22]. Sensor installation faces challenges due to severe spatial constraints. Moreover, sensor presence can interfere with normal operation and raises long-term reliability concerns [23]. However, monitoring external stray flux offers a more practical, non-invasive, and robust strategy [24]. Fault-induced asymmetries in the main air-gap flux directly modulate the external stray flux signal. This makes the external flux a valuable source of diagnostic information. Advanced analysis of multi-sensor stray flux data has proven effective for fault identification. Such techniques often utilize symmetrical components or Park’s vectors to detect faults like inter-turn short circuits and various forms of eccentricity [25,26,27,28,29].

However, stray flux analysis faces significant diagnostic challenges. It is often difficult to clearly distinguish fault signatures from spectral patterns caused by operating conditions. For instance, stray flux analysis relying on a single sensor can yield misleading results since these faults may produce overlapping spectral signatures. Such spectral overlaps hinder the accurate isolation of the true source of an anomaly. The spectral similarity between static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB) provides a critical example of this diagnostic ambiguity. This overlap creates significant diagnostic uncertainty and can lead to incorrect maintenance decisions [30].

Although prior studies have addressed related issues, such as discriminating inter-turn short circuits from the load unbalance using electrical signals [31], the discrimination of SE and UnB effects specifically through stray flux analysis represents an unaddressed research gap. Therefore, a robust methodology to overcome this diagnostic challenge in PMSGs is essential.

This paper introduces a robust methodology based on stray flux analysis to identify and differentiate static eccentricity and load current unbalance in PMSG. The approach analyzes the space vector spectrum derived from external stray flux measurements. A space vector is synthesized using signals from three sensors arranged with a 120° electrical phase shift around the PMSG frame. The comprehensive 2D finite element (FE) simulations evaluate the proposed technique under both SE and UnB fault. Results indicate that the +5fs harmonic component within the positive sequence of the stray flux space vector spectrum functions as a unique and reliable indicator for detecting static eccentricity faults. Furthermore, the practical applicability of the proposed method is experimentally validated on a laboratory test bench. The experimental study demonstrates the method’s immunity to practical industrial challenges, including sensor positioning errors and environmental noise. This specific feature permits the clear discrimination of static eccentricity from electrical load current unbalance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling PMSG and Analyzing Static Eccentricity and Load Current Unbalance

A 2D finite element (FE) model of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator (PMSG) in Ansys®Maxwell 2D (Version 2025 R2) software is utilized for the analysis of faults. A time-stepping transient solver computed key electromagnetic and mechanical variables. These variables include magnetic flux distributions, phase currents, and electromagnetic torque.

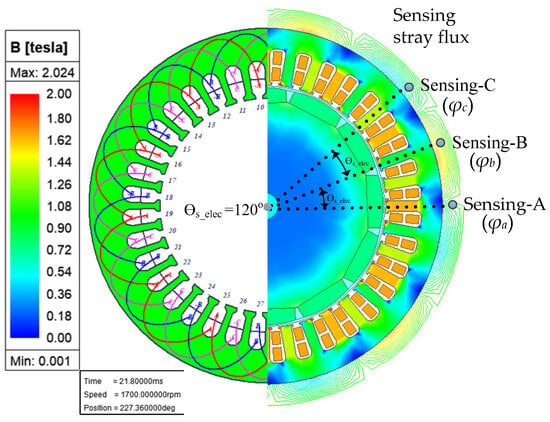

The FE model incorporates the exact geometry of the 36-slot stator and 12-pole rotor, including the precise dimensions of the ferromagnetic cores and permanent magnets. Furthermore, the nonlinear magnetic properties of the core materials have been included in the model by using their specific B–H curves. The key parameters of the simulated generator are detailed in Table A1 (See Appendix A). Figure 2 illustrates the 2D cross-section of the generator model and indicates the sensor positions to track stray flux around the stator surface. The objective is to capture three flux signals with a relative phase shift of 120 electrical degrees (θelec). Achieving the target electrical angle (θs_elec) requires setting the correct mechanical angle (θmech) between the sensors. This angle depends on the fundamental relationship θelec = (P/2)θmech, where P is the number of the pole, and slot angle (θs_elec) can be calculated as shown in Equation (1), where Ns is the total number of stator slots.

Figure 2.

The model of PMSGs with sensor locations and winding distribution.

For the PMSG used in this study, the electrical angle per slot pitch (θs_elec) is 60°. Therefore, the sensors (Sensor A, Sensor B, and Sensor C) are positioned with a spatial separation corresponding to two stator slot pitches to achieve the required 120° electrical phase shift between each consecutive flux sensors. Notably, the radial distance of the sensors from the generator frame influences the amplitude of the measured stray flux signal. However, it does not alter the signal’s fundamental harmonic content. The static eccentricity (SE) fault has been implemented by shifting the rotor’s rotational axis relative to the stator’s geometric center along the horizontal axis. The severity of the fault has been varied from 5% to 40% of the nominal air-gap length. This range has been selected to cover the full spectrum of potential fault conditions, from incipient to severe levels.

The 5% lower bound is chosen to evaluate the method’s sensitivity to incipient faults. Notably, eccentricity levels up to 10% may fall within acceptable manufacturing tolerances in many industrial machines [32]. Therefore, its signature can be masked by the machine’s baseline asymmetries. The 40% upper bound represents a severe fault condition. This level served to test the robustness of the diagnostic indicators under significant magnetic field distortion.

Load current unbalance has been simulated by coupling the generator’s FE model with an external circuit. This approach facilitates a realistic implementation of variable and asymmetrical load conditions. The unbalance itself has been introduced by asymmetrically modifying the values of the resistive loads for each phase within this external circuit. A 5% current unbalance level has been selected for this study which represents a common industrial threshold defined by standards such as NEMA MG-1 and ANSI C84.1 [33,34]. The average phase current (iph_avg) and the resulting current unbalance percentage (iunb) can be calculated as shown in Equation (2).

In Equation (2), (iph_avg) is the average of the magnitudes of the phase currents. (iph_max) is the magnitude of the phase current with the maximum deviation from this average value. (iph_i) represents the individual phase currents (e.g., iph_a, iph_b, iph_c), and Nph is the total number of phases.

A healthy PMSG maintains a symmetrical air-gap magnetic field. The presence of a static eccentricity (SE) fault introduces a non-uniform air-gap length. This non-uniformity directly distorts the magnetic field. The mathematical expression for this non-uniform, position-dependent air-gap length (g(θ)) is provided in Equation (3).

where g(θ) is the air-gap length as a function of the stator spatial angle θ. g0 represents the healthy air-gap length, and δse is the per-unit static eccentricity degree.

Air-gap permeance (Ƥ(θ)) is directly proportional to the inverse of the air-gap length. Therefore, an SE fault causes the air-gap permeance to become variable and position-dependent. A Taylor series expansion is applied to this expression to derive a simplified analytical model. This simplification is valid when the eccentricity degree (δse) is very small compared to the nominal air gap (g0). Neglecting the third and higher-order terms of this series yields the approximate permeance expression shown in Equation (4).

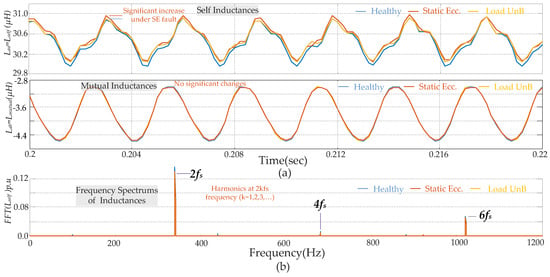

This position-dependent air-gap permeance directly influences the machine’s inductance parameters. Figure 3 shows the variation in the self-inductance (Lself) and mutual inductance (Lm) under healthy, static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB) faults. The asymmetrical air-gap causes these inductances to fluctuate by introducing harmonic components in back-electromotive force and armature currents. The self-inductance of phase-A (Laa) exhibits significant fluctuations under the SE fault condition compared to that of load current unbalance, as seen Figure 3a. This fluctuation directly results from the non-uniform air gap described by Equations (3) and (4). It is also seen that the peak value of the self-inductance can increase depending on the static eccentricity fault severity. On the other hand, the self-inductance remains unchanged under the load current unbalance condition since load current unbalance does not change the physical air-gap length and its permanence. The mutual inductance between phase-A and phase-B (Lab), as seen in Figure 3a, shows less variation under different operational conditions.

Figure 3.

The inductance variations for healthy, static eccentricity, and load current unbalance (a) self-inductance (Laa) and mutual inductance (Lab). (b) Frequency spectrum of self-inductance (FFT of (Laa)).

These inductance variations are fundamental to understanding the dynamic behavior of each fault signature. The phase inductance matrix (Ls) is basically dependent on the rotor position (θr), and total flux linkage (λm, m ∈ (a, b, c)) is the summation of the flux linkage of Lmm(θr)*im and the flux linkage produced by permanent magnets λPM (θr), as seen in Equation (5).

According to the permanent magnet machine model, even-order harmonics are dominant in the phase inductances (as seen in Figure 3b). Therefore, the corresponding inductances can be expressed, as shown in Equation (6).

where L0 is the mean value of the phase inductance, h represents the harmonic number. θe is the electrical degree which is equal to (θe = ωet).

Assuming that the armature currents contain only the fundamental harmonic component, the total flux linkage (of which stray flux is a function) can be obtained as the product of fundamental cosine components, as given in Equation (7).

where ∅ represents the electrical phase angle of corresponding parameters. As seen in the equation, odd harmonics with frequencies of (2h ± 1), such as the 1st, 3rd, and 5th, appear in the total flux linkage depending on Equation (7). In the case of any fault affecting the phase inductances, such as a static eccentricity (SE) fault, the amplitudes of these harmonics can be increased depending on the fault severity.

According to Faraday’s law, the derivative of the total flux linkage induces a back-EMF voltage. This back-EMF generates currents to flow in the armature windings, and these currents will contain the same harmonic components observed in the back-EMF (i.e., in the total flux linkage). Similarly, when additional harmonics appear in the armature currents, extra sideband harmonics can be observed in the total flux linkage due to the cosine product of inductances and currents. The frequencies of fault related sidebands (fsb) [34] are defined by their relationship with the fundamental supply frequency (fe) and the rotor rotational frequency (fr), as shown in Equation (8).

where k is an integer (1, 2, 3,…), and p is the number of pole pairs. Critically, the existence and amplitude of fault-related sideband harmonics in stator currents depend heavily on the machine’s topology, particularly the winding configuration and slot/pole combination [35,36]. This configuration acts as a spatial filter. In fractional-slot/pole machines (e.g., 9-slot/8-pole), these harmonics (fsb) are typically prominent in the current and flux spectra. The generator used in this study has an integer slot/pole ratio (36 slots/12 poles). For this topology, the characteristic sidebands, defined in Equation (8), are known to be significantly suppressed or canceled in the back-EMF as well as in the stator current.

The load current unbalance also produces sideband harmonics that can appear at similar frequencies. This spectral overlap makes it difficult to understand the true source of the harmonics and leads to the diagnostic challenges. This diagnostic lack arises because load current unbalance and static eccentricity (SE) can produce similar harmonic signatures. When the generator operates under load current unbalance, the stator phase currents become unequal in magnitude. This condition creates an asymmetric magneto motive force (MMF) distribution. The air-gap magnetic field then contains additional harmonic components, particularly those associated with the negative-sequence current.

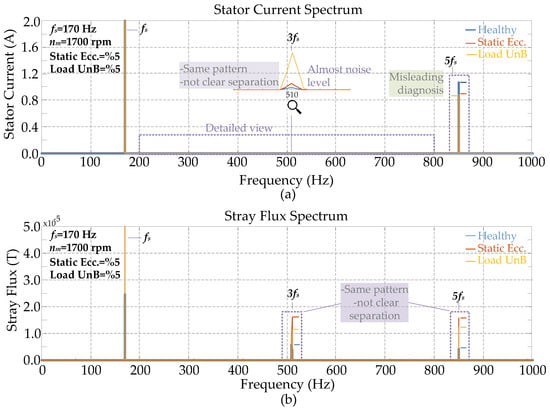

Figure 4 presents comparative results illustrating this diagnostic difficulty. The analysis includes the healthy condition, a 5% static eccentricity (SE) fault, and a 5% load current unbalance (UnB). Figure 4a specifically shows the stator current spectrum. The current spectrum lacks clear diagnostic indicators for either the SE or UnB condition. No significant fault-related harmonic components appear in the stator current for SE or UnB compared to the healthy case. Although the 3fs harmonic is detectable, its amplitude remains close to the noise level. This low amplitude prevents its use as a reliable fault indicator. Figure 4b shows the stray flux spectrum where the stray flux is tracked from one single point (see Sensing-A in Figure 2). This analysis method also proves insufficient for reliable diagnosis. As seen, both the SE fault and the load unbalance condition produce identical spectral patterns. Specifically, the 3fs and 5fs harmonics exhibit similar patterns under both anomalies. This similarity prevents a clear separation between the SE fault and the UnB condition using single-point stray flux analysis. These results confirm the theoretical limitations of conventional analyses including stator current and single-point stray flux analysis. This failure necessitates a more advanced signal processing approach.

Figure 4.

The spectrums of (a) stator current, (b) stray flux under static eccentricity (5%), and load current unbalance (5%).

2.2. Symmetrical Components and Space Vector Stray Flux (SVSF) Approach

The analysis in Section 2.1 demonstrated that monitoring a single point of stray flux is insufficient for identifying static eccentricity and load current unbalance due to similar patterns at corresponding spectrums. Therefore, this study employs a more robust method based on the space vector stray flux (SVSF). The SVSF can be obtained using three-phase information from the three stray flux sensors placed at the vicinity of the stator frame.

This vector-based approach is designed to increase the efficacy of the fault detection process by capturing the spatial distribution of the magnetic field. The proposed method analyzes the stray flux space vector utilizing the theory of symmetrical components. It mathematically decomposes any unbalanced three-phase set of signals (such as currents or fluxes) into three independent, balanced signal sets. These sets are the positive-sequence, negative-sequence, and zero-sequence components. Each component has a distinct physical interpretation. The positive-sequence component represents the balanced, primary energy-producing field rotating in the intended direction. In a perfectly healthy and balanced system, only the positive-sequence component exists. The negative-sequence component represents a balanced field rotating in the reverse direction, while the zero-sequence component consists of three signals in phase with each other. The presence of negative- or zero-sequence components directly indicates an unsymmetrical condition within the system. Conditions such as static eccentricity and load current unbalance introduce these components. Typically, the magnitude of these sequence components correlates with the severity of the fault or the level of unbalance.

Asymmetries within the PMSG system, such as static eccentricity (SE) or load current unbalance (UnB), inherently distort the ideal sinusoidal flux waveforms expected under a healthy condition. These distortions fundamentally produce as deviations in both the amplitude and the phase angle of the individual harmonic components comprising the measured stray flux signals.

Accordingly, a rigorous per-harmonic mathematical characterization of amplitude and phase variability is required for accurate generator condition diagnosis and for discriminating among asymmetry classes whose spectral signatures are masked by simpler analyses.

The methodology begins by defining the baseline model for the h-th harmonic component of the stray flux signal (ϕm(h)(t)), for each phase sensor m ∈ {a, b, c} under healthy condition, as given in Equation (9).

where k = 0 (for phase-a), 1 (for phase-b), and 2 (for phase-c) indicates the phase index. The distortions are characterized by deviations in both the amplitude and the phase angle of the individual harmonic components. To model these non-ideal conditions, a per-phase amplitude factor (αm) and per-phase angle deviation (εm) are introduced. For a concise analysis using complex phasors, the h-th harmonic component of the flux in phase m ∈ (a, b, c) under faulty conditions φm(h) is expressed, as shown in Equation (10).

This complex phasor representation of the individual phase fluxes allows for the direct calculation of the h-th harmonic stray flux space vector (SVSF). The SVSF is defined by the relationship between its complex phasor representation including each harmonic components in Equation (10), as below:

This space vector representation is crucial as it consolidates the amplitude (αm) and phase (εm) distortions from all three flux into a single complex quantity.

Theoretically, the specific selection of the +5fs harmonic is determined by the modulation of the air-gap permeance. Static eccentricity (SE) introduces a non-uniform, stationary air-gap distribution that modifies the permeance function. This distortion typically introduces specific spatial harmonics, most notably the 6th order spatial harmonic due to the interaction with the machine’s geometry. When the fundamental stator MMF interacts with this 6th spatial permeance harmonic, it induces flux components at frequencies of (1 ± k) fs. Consequently, a distinct positive-sequence harmonic appears at +5fs (i.e., ).

Conversely, load current unbalance (UnB) primarily generates a negative-sequence component at the fundamental frequency without modifying the air-gap geometry. Unlike static eccentricity, UnB preserves the uniform permeance distribution, failing to excite the higher-order spatial harmonics associated with geometric faults. This fundamental difference establishes the +5fs positive-sequence harmonic as a robust and selective indicator for distinguishing SE from load current unbalance.

In a balanced system, represents only the positive sequence component. As demonstrated, the introduction of any faults (αm ≠ 1 or εm ≠ 0) breaks this symmetry, causing a single harmonic order h to generate components in both positive and negative sequences simultaneously. This general framework is now applied specifically to the 5fs harmonic (h = 5), which is fundamental to the diagnostic indicator proposed in this study.

To analyze the impact of asymmetries, the general SVSF definition (Equation (11)) is applied for h = 5, incorporating the fault parameters from Equation (10).

Equation (10) forms the theoretical basis for the diagnostic method. The distinct impacts of load current unbalance (UnB) and static eccentricity (SE) on this specific harmonic component can be clearly demonstrated by analyzing Equation (11) under their respective fault conditions.

In load current unbalance (UnB), the asymmetry is characterized by unequal amplitude factors (αm ≠ 1) while the ideal phase shifted is maintained (εm = 0). When these parameters are applied to Equation (11) considering 5th harmonic, the αm terms directly modify the magnitude of the three flux phasors being summed, but the fundamental vector orientation (defined by and ) is preserved.

Static eccentricity (SE) is fundamentally characterized by the introduction of both amplitude factor (αm ≠ 1) and phase angle deviations (εm ≠ 0) for 5fs harmonic. When these non-zero phase shifts are substituted into Equation (10) and Equation (11), they disrupt the precise 120° phase relationships required for sequence purity. This phase and amplitude distortion mathematically disrupt the symmetry resulting in 5fs harmonic, generating both its original negative-sequence component (due to the inherent h = 5 structure) and, critically, a new positive-sequence component (induced by the αm and εm fault terms).

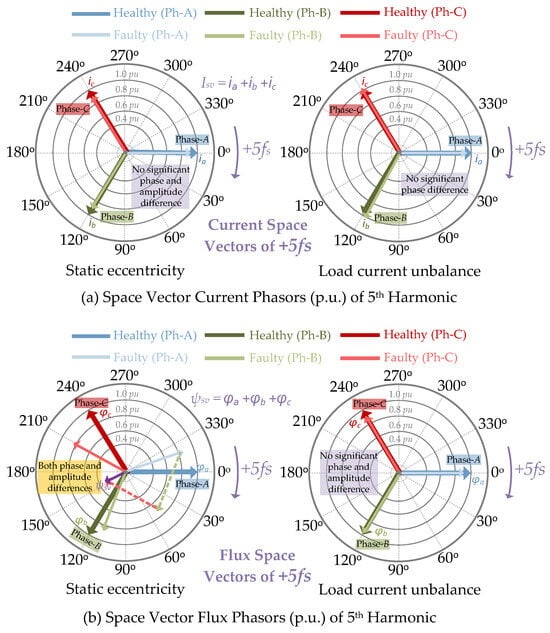

This mathematical derivation reveals the core diagnostic principle: in a system where the 5th harmonic should be purely negative-sequence, the emergence of a positive-sequence component at the 5th harmonic frequency (which corresponds to +5fs in the spectrum) serves as a unique and robust indicator of static eccentricity, allowing it to be distinguished from load current unbalance. This theoretical distinction is visually validated by the phasor diagrams in Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5a, the 5th harmonic components in the armature current exhibit only minor magnitude and phase variations across all three operational conditions. Consequently, the resulting current space vector fails to provide significant differentiation, confirming the limitations of current analysis for fault identification. However, the stray flux phasors in Figure 5b offer clear diagnostic information for the theoretical derivation. Under the load current unbalance (UnB) condition, the flux phasors exhibit less amplitude asymmetry but maintain their close to 120° phase difference, consistent with the εm = 0.

Figure 5.

Comparative space vector phasor diagrams of the 5th (+5fₛ) harmonic components for healthy, static eccentricity, and load current unbalance conditions. (a) Current, (b) stray flux.

This results in a resultant space vector with minimal deviation from the healthy case. Conversely, the static eccentricity (SE) condition introduces significant phase angle deviations with less amplitude changes. This observation aligns with the εm≠ 0 terms in Equations (10) and (11).

A resultant space vector shift can originate from asymmetries in both phasor amplitude and phase. The analysis in Figure 5b confirms the SE fault primarily introduces significant phase distortion. This phase distortion is the dominant mechanism causing the resultant vector’s phase shift, rather than the minor changes in amplitude. This comparison reveals that the asymmetric magnetic impact of the SE fault induces primarily as a phase distortion. This uniquely distorts the 5th harmonic stray flux space vector, whereas load unbalance does not produce this effect.

To provide quantitative validation for the phasor analysis representation, the PMSG model has been simulated in Ansys® Maxwell under full-load operation. The simulation contrasted three distinct operational states: healthy, 5% static eccentricity (SE), and 5% load current unbalance (UnB). Table 1 summarizes the resulting 5th harmonic phasor data, presenting the specific magnitudes and phase angles extracted from both the stator currents and the three-phase stray flux signals for each condition. Consistent with Table 1, static eccentricity (SE) produces only slight deviations in per-phase stray-flux amplitudes, while the 5th-order harmonic shows a distinct phase displacement.

Table 1.

Comparison of 5th harmonic phasor components for current and stray flux.

The signal processing framework utilized in this study employs the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to extract the harmonic amplitude and phase from the computed SVSF signal. While advanced decomposition techniques are advantageous for analyzing non-stationary signals or resolving severe spectral overlap, the leakage flux signals in this study exhibit stationary and narrowband characteristics acquired under steady-state conditions. Furthermore, the diagnostic +5fs indicator occupies a spectrally distinct position, well-separated from the fundamental component and other dominant harmonics. These physical conditions allow standard FFT-based spectral analysis to provide accurate and unbiased phase estimation without the mode mixing issues often associated with adaptive algorithms. Consequently, the FFT is selected as the optimal tool, offering precise phase identification for this stationary application with superior computational efficiency compared to complex instantaneous phase extraction methods.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Simulation Results

This section validates the proposed diagnostic methodology using the simulation data. The PMSG model has been operated at 1700 rpm under rated load, as detailed in Section 2. The analysis contrasts the healthy case against multiple fault scenarios. These scenarios include static eccentricity (SE) severities ranging from 5% to 40% and a 5% load current unbalance (UnB) case.

The stray flux and stator current signals have been collected for 5 s at a 2.5 kHz sampling frequency. This raw three-phase data is subsequently used to compute the stray flux space vector for spectral analysis.

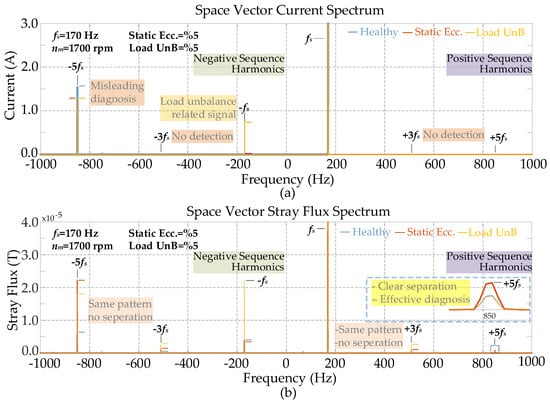

Figure 6 directly compares the diagnostic performance of the SV–FFT analysis applied to both stator current and stray flux. The analysis utilizes simulation data for the healthy case, a 5% static eccentricity (SE) fault, and a 5% electrical load unbalance (UnB) condition, all obtained at 1700 rpm under rated load. Figure 6a presents the stator current SV spectrum. This spectrum highlights the limitations of using current signals, even with SV analysis. Only the fundamental components at (±fs) are prominent. Crucially, no distinct spectral signature indicates the presence of the SE fault. This result confirms that the current SV spectrum cannot reliably differentiate the healthy case from the SE fault, nor can it separate SE from the UnB condition.

Figure 6.

The spectrums of space vector (SV), (a) stator current, (b) stray flux under static eccentricity (5%), and load current unbalance (5%).

Figure 6b displays the stray flux SV spectrum. Harmonics at ±fs, ±3fs, and ±5fs are clearly visible and exhibit significant changes under fault conditions. The crucial diagnostic information resides within the 5fs components.

The -5fs harmonic (negative-sequence) increases significantly under both the SE fault and the UnB condition, serving as a general indicator of system asymmetry. However, the +5fs harmonic (positive-sequence) shows a distinct increase only during the SE fault. Its amplitude remains negligible during the healthy case and under the UnB condition. These results directly validate the hypothesis proposed in Section 2. The +5fs component emerges as a unique and robust feature enabling reliable discrimination of static eccentricity. While electrical load unbalance primarily generates negative-sequence components, static eccentricity uniquely generates the +5fs positive-sequence component in the SVF spectrum. This fundamental difference allows clear separation between the two conditions using the stray flux space vector spectrum. Further simulations have been conducted to evaluate the sensitivity of the +5fs harmonic component under varying operational conditions.

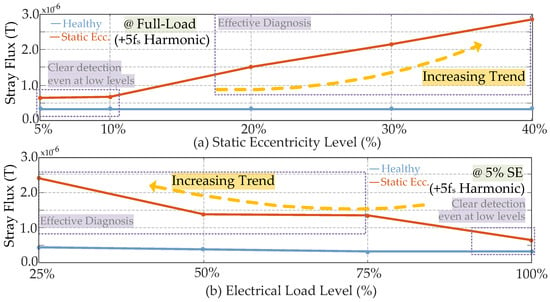

The analysis focuses on two key parameters, namely the fault severity and the electrical load level, as shown in Figure 7. First, the relationship between the +5fs component amplitude and the SE fault severity has been investigated, as illustrated in Figure 7a. With the generator operating at full load, the SE severity has been varied from 5% to 40%. The results demonstrate a clear and monotonic correlation between the 5fs component amplitude and the SE percentage level. The amplitude of the 5fs component increases proportionally as the SE percentage rises. This trend confirms that the +5fs harmonic is a direct and sensitive indicator of the SE fault’s severity, showing clear detection even at low (5–10%) levels. Second, the diagnostic efficacy of the +5fs component has been evaluated across the full operational load range of the generator, as shown in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

Characteristics variations on +5fs harmonic in SFSV spectrum with (a) different static eccentricity levels and (b) different electrical load levels.

For this test, the SE fault level has been held constant at 5% while the electrical load has been varied from 25% to 100%. The results confirm that the +5fs component remains a clear and effective diagnostic indicator across the entire load level.

As seen in Figure 7b, at full load the amplitude of the +5fₛ component is at least twice that of the healthy baseline. Moreover, it increases as the load level decreases, indicating that effective diagnostic discrimination is achievable even under low load and fault severity.

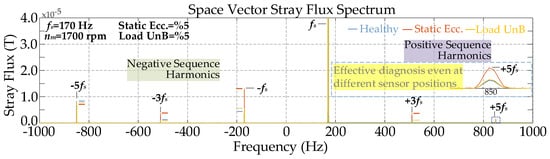

In the proposed methodology, achieving an exact 120° phase displacement between the sensors is a demanding and precision-dependent task in practical applications. In certain cases, the sensors may not be placed with an ideal 120° phase separation. To assess the influence of such angular deviations, alternative sensor configurations such as 0°, 102°, and 228° (electrical) has been employed and the modeled PMSG have been operated under healthy, static eccentricity, and load current unbalance conditions by examining the corresponding SVSF spectra. As shown in Figure 8, the amplitude of the +5fs harmonic in the SVSF spectrum appears clearly under the static eccentricity condition while it remains nearly identical to that of the healthy state under load current unbalance. This is mainly because both the magnitudes of the three flux vectors and the angles between each other change in the static eccentricity whereas the flux vectors exhibit negligible deviations in the load current unbalance. As a result, it can be clearly seen that the proposed method provides an effective diagnosis even in the presence of sensor position errors that may occur due to practical difficulties. To investigate the effects of static eccentricity (SE) occurring along different directions, the simulation study has been expanded. The fault displacement has been applied specifically along both the horizontal (x) and vertical (y) axes to compare the spectral responses.

Figure 8.

The space vector stray flux spectrum under static eccentricity (5%) and load current unbalance (5%) for different sensor positions (0°, 102°, and 228° electrical).

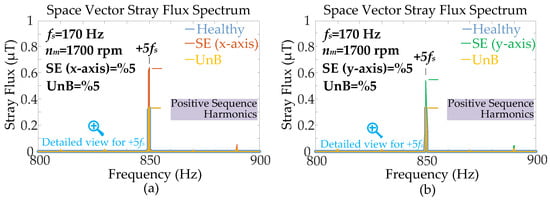

Figure 9 presents the space vector stray flux spectrum obtained for these two cases within the 800–900 Hz range. The results indicate that the diagnostic +5fs harmonic remains detectable regardless of whether the eccentricity occurs on the x-axis or the y-axis. Although slight variations in signal amplitude have been observed, the characteristic spectral pattern remained consistent. Consequently, the proposed method is verified to be independent of the fault direction, ensuring reliable detection irrespective of the relative position between the sensors and the fault axis.

Figure 9.

The space vector stray flux spectrum under static eccentricity (5%) and load current unbalance (5%) for different SE fault orientations on the (a) SE x-axis and (b) SE y-axis.

These findings demonstrate that the +5fs component is a robust indicator for detecting the presence of SE. Furthermore, it provides a reliable measure of fault severity, provided that the electrical load level and practical deviations in sensing locations are known or compensated for during the diagnosis.

3.2. Experimental Setup and Results

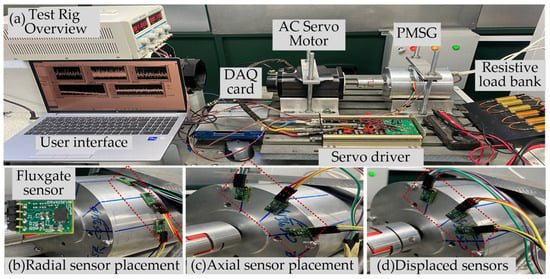

To validate the proposed diagnostic methodology and verify the simulation results under practical operating conditions, a dedicated experimental test rig has been constructed. Figure 10a illustrates the experimental test rig, which comprises a 2.5 kW, 36-slots 8-poles PMSG mechanically coupled to an AC servo motor prime mover to ensure it moves at rated speed. The generator is connected to a configurable resistive load bank to simulate various load conditions, including balanced and unbalanced conditions. Three high-sensitivity fluxgate sensors (TI DRV-425N) are mounted on the external frame of the generator to capture the leakage flux. The sensors are positioned 120 electrical degrees apart. The TI DRV-425N sensors have been selected for their high bandwidth and sensitivity (up to 47 kHz and 600 µT range), making them suitable for capturing low-magnitude stray flux harmonics even through the stator casing. The sensor signals are acquired using a National Instruments Data Acquisition (NI DAQ) card with a sampling frequency of 5 kHz. Figure 10 displays the custom LabVIEW interface developed for real-time data monitoring, recording, and FFT analysis. Adjusting the load resistance in a single phase induces the load current unbalance condition.

Figure 10.

(a) Experimental test rig showing PMSG, servo motor prime mover, and custom LabVIEW interface for data acquisition, (b) radial sensor placement, (c) axial sensor placement, and (d) displaced sensors.

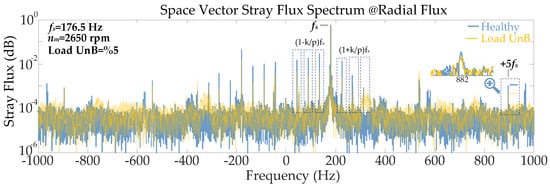

To verify the simulation results, the PMSG has been tested under healthy and 5% load current unbalance (UnB) conditions. As shown in the experimental spectra in Figure 11, although signal amplitudes are attenuated by the stator frame, the spectral pattern remains consistent. Notably, intrinsic sidebands characteristic of the fractional slot topology is observed. Despite these inherent spectral components, the diagnostic +5fs harmonic exhibits a magnitude that remains at residual levels characteristic of the healthy case. This confirms that the load unbalance does not excite the specific spatial permeance harmonic associated with static eccentricity (SE).

Figure 11.

Experimental space vector stray flux (SVSF) spectra comparing healthy and load unbalance conditions.

This experimental evidence validates that the diagnostic signature identified in the 2D simulations is robust against practical factors such as casing attenuation, assembly gaps, and 3D flux paths.

The experimental validation in this study employs an off-grid generator topology connected directly to a passive resistive load bank, ensuring sinusoidal stator currents devoid of inverter-induced switching harmonics. Regarding industrial applicability, where inverter-fed drives typically introduce harmonic distortions of 2–5%, the robustness of the proposed method relies on the predominance of the rotor permanent magnets as the primary source of external leakage flux. Due to this dominant rotor field contribution, minor stator current distortions impose negligible influence on the leakage flux pattern compared to the geometric modulation induced by eccentricity. Furthermore, the space vector analysis inherently distinguishes the diagnostic +5fs signature from low-order time harmonics based on their symmetrical sequence and spatial origin, effectively augmenting the high-frequency noise rejection provided by standard low-pass filtering (LPF).

To validate the method’s robustness against practical implementation constraints, systematic experimental tests evaluating positional deviations of sensors, 3D flux effects, and environmental noise are conducted. Specifically, regarding sensor installation, industrial motor frames often impose geometrical constraints due to cooling fins and mechanical supports, preventing precise symmetrical mounting.

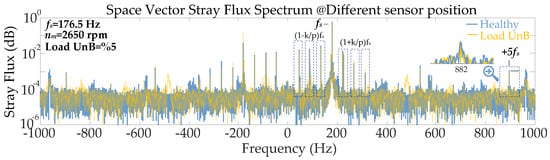

Consequently, the sensitivity to such positional deviations has been evaluated by intentionally displacing the sensors to electrical angles of 40°, 120°, and 240°, representing significant asymmetry relative to the ideal 120° spacing. Figure 12 presents the experimental space vector stray flux (SVSF) spectrum obtained under these non-ideal conditions.

Figure 12.

Experimental SVSF spectrum under static eccentricity (5%) and load current unbalance (5%) for different sensor positions (40°, 120°, and 240° electrical).

Crucially, the amplitude of the diagnostic +5fs harmonic remained at residual levels characteristic of the healthy case, confirming that asymmetric sensor placement does not induce false positive indicators, even in the presence of load current unbalance (UnB). This demonstrates that the diagnostic reliability relies on the spectral existence of specific sequence components rather than perfect geometric sensor symmetry.

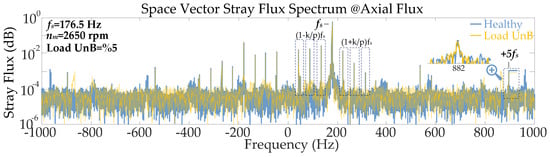

2D FEA models inherently neglect complex 3D leakage flux paths and end-winding effects. To account for these inherent non-idealities, supplementary experiments have been conducted by capturing the axial leakage flux component (Figure 10). The SVSF spectrum under load current unbalance (Figure 13) shows that the diagnostic +5fs harmonic remains at residual levels characteristic of the healthy case. This result confirms the preservation of the spectral pattern despite the signal magnitude differences resulting from the axial sensor placement. Consequently, the proposed method demonstrates immunity to false positives, as complex 3D flux variations do not artificially excite the static eccentricity indicator.

Figure 13.

Evaluation of 3D effects: experimental SVSF spectrum of axial stray flux.

Also, the impact of electromagnetic interference (EMI) has been evaluated by positioning an active motor drive inverter in close proximity to the sensors (Figure 10). Although the stray flux signals exhibited high-frequency switching noise, the spectral pattern remained stable. This observation confirms the method’s robustness against environmental noise. Additionally, the consistency between simulated and experimental patterns validates that the finite sensing volume of the TI DRV-425N fluxgate sensors does not mask the required spatial harmonic content.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes and validates a robust diagnostic methodology for detecting static eccentricity (SE) and load current unbalance (UnB) faults in PMSGs systems. The proposed approach overcomes a key limitation of conventional Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) and single-point stray flux methods, as these techniques often struggle to differentiate between static eccentricity and load current unbalance faults due to the similarity of their spectral patterns.

The proposed method employs space vector stray flux (SVSF) signals derived from three external sensors placed 120 electrical degrees apart, followed by symmetrical component analysis of the resulting spectrum. Two-dimensional Finite Element Analysis (FEA) results demonstrate that both the magnitude and phase angle of the +5fs harmonic space vectors vary significantly under static eccentricity whereas only minor variations are seen under load current unbalance. These numerical findings are validated by experimental validation using a 2.5 kW PMSG test rig. The experimental results confirm that the diagnostic +5fs harmonic remains a distinct indicator even under practical non-ideal conditions, such as casing attenuation and electromagnetic interference. Consequently, the amplitude of +5fs harmonic exhibits a clear increase in static eccentricity but remains nearly unchanged for load current unbalance in SVSF spectrum. Moreover, experimental sensitivity analyses regarding sensor displacement and 3D flux paths verified that the proposed method does not generate false positives, providing a robust solution for industrial condition monitoring.

The diagnostic capability of the defined +5fs flux harmonic has been verified under various fault severities and electrical load levels, confirming the robustness of the method. Additional tests with different sensor positions (deviating from 120 electrical degrees further) validated that the +5fs harmonic shows consistent and reliable diagnostic performance. Overall, the proposed SVSF-based technique offers an accurate and reliable solution for fault detection in PMSG based systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G., I.A. and M.A.; methodology, T.G., I.A. and M.A.; software, I.A., T.G. and M.A.; validation, I.A., T.G., M.A. and B.Y.; investigation, I.A., T.G., M.A. and B.Y.; resources, I.A., T.G., M.A. and B.Y.; data curation, I.A., T.G., M.A. and B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A. and T.G.; writing—review and editing, I.A., T.G., M.A. and B.Y.; visualization, I.A., T.G. and M.A.; supervision, T.G. and M.A.; funding acquisition, I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) under Grant No. 1059B142100619. The authors gratefully acknowledge TÜBİTAK for its support. The authors paid the article processing charge (APC).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The parameters of permanent magnet synchronous generator is given in Table A1.

Table A1.

The tested generator parameters.

Table A1.

The tested generator parameters.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of poles | 12 |

| Number of stator slots | 36 |

| Outer stator diameter, mm | 133.8 |

| Inner stator diameters, mm | 91.3 |

| Outer rotor diameter, mm | 89.3 |

| Rated power, kW | 0.4 |

References

- Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Li, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, C. Faults and diagnosis methods of permanent magnet synchronous motors: A review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, N.M.A.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Fault Detection and Condition Monitoring of PMSGs in Offshore Wind Turbines. Machines 2021, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeik, M.; dos Santos, E.C. High-Torque Electric Machines: State of the Art and Comparison. Machines 2022, 10, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, B.; Kim, M.; Park, H.-P. AC Series Arc Fault Detection for Wind Power Systems Based on Phase Lock Loop With Time and Frequency Domain Analyses. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 12446–12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Stone, G.C.; Antonino-Daviu, J.; Gyftakis, K.N.; Strangas, E.G.; Maussion, P.; Platero, C.A. Condition Monitoring of Industrial Electric Machines: State of the Art and Future Challenges. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2020, 14, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; He, S.; Huang, J. A Review of Modeling and Diagnostic Techniques for Eccentricity Fault in Electric Machines. Energies 2021, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Ebrahimi, B.M.; Akin, B.; Toliyat, H.A. Comprehensive Eccentricity Fault Diagnosis in Induction Motors Using Finite Element Method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 1764–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.M.; Faiz, J.; Roshtkhari, M.J. Static-, Dynamic-, and Mixed-Eccentricity Fault Diagnoses in Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 4727–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri-Tehrani, E.; Faiz, J. Airgap and stray magnetic flux monitoring techniques for fault diagnosis of electrical machines: An overview. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2022, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Bu, F.; Yang, Z. Open-circuit radial stray magnetic flux density based noninvasive diagnosis for mixed eccentricity parameters of interior permanent magnet synchronous motors in electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.M.; Faiz, J. Magnetic field and vibration monitoring in permanent magnet synchronous motors under eccentricity fault. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2012, 6, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, V.; Capolino, G.-A.; Akin, B.; Henao, H.; Romary, R.; Pusca, R. Recent Trends in Magnetic Sensors and Flux-Based Condition Monitoring of Electromagnetic Devices. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 4668–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusca, R.; Lefevre, E.; Mercier, D.; Romary, R.; Irhoumah, M. Diagnosis of electrical machines by external field measurement. In Electrical Systems 2: From Diagnosis to Prognosis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Yang, C.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, D.-M.; Fernandez, D.; Reigosa, D.; Briz, F. Online Detection and Classification of Rotor and Load Defects in PMSMs Based on Hall Sensor Measurements. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 3803–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergakis, A.; Salinas, M.; Gkiolekas, N.; Gyftakis, K.N. A Review of Condition Monitoring of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: Techniques, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, T.; Zafarani, M.; Akin, B. Discernment of Broken Magnet and Static Eccentricity Faults in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2016, 31, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaq, M.S.; Lee, H.-J.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.B.; Zapico, M.O.; Fernandez, D.; Reigosa, D.; Briz, F. Airgap Search Coil Based Identification of PM Synchronous Motor Defects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6551–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, I.-H.; Wang, W.-J.; Lai, Y.-H.; Perng, J.-W. Analysis of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fault Diagnosis Based on Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Diagnosis of Interturn Short-Circuit Faults in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors Based on Few-Shot Learning under a Federated Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 8495–8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, H.; Qu, R. A Novel Data Generation and Quantitative Characterization Method of Motor Static Eccentricity with Adversarial Network. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 8027–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio-Ramirez, I.; Osornio-Rios, R.A.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A.; Razik, H.; Romero-Troncoso, R.d.J. Magnetic Flux Analysis for the Condition Monitoring of Electric Machines: A Review. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2895–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, S.B.; Yun, J.; Sasic, M.; Stone, G.C. Air gap flux-based detection and classification of damper bar and field winding faults in salient pole synchronous motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.F.; Kim, H.-j.; Lee, S.B.; Lim, C. Online Airgap Flux Based Diagnosis of Rotor Eccentricity and Field Winding Turn Insulation Faults in Synchronous Generators. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio-Ramirez, I.; Saucedo-Dorantes, J.J.; Antonino-Daviu, J.; Osornio-Rios, R.A.; Dunai, L. Detection of uniform gearbox wear in induction motors based on the analysis of stray flux signals through statistical time-domain features and dimensionality reduction techniques. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 4648–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftakis, K.N.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Reliable Detection of Stator Interturn Faults of Very Low Severity Level in Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 3475–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yuan, S.; Liu, X.; Pong, P.W.T.; Liu, C. Online Detection and Location of Eccentricity Fault in PMSG With External Magnetic Sensing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 9749–9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femia, A.; Ruiz-Sarrio, J.E.; Sala, G.; Antonino-Daviu, J.; Zarri, L. Eccentricity Fault Diagnosis in Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motors Using the Stray Flux Vector. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Workshop on Electrical Machines Design, Control and Diagnosis (WEMDCD), Valletta, Malta, 9–10 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftakis, K.N.; Panagiotou, P.A.; Palomeno, E.; Lee, S.B. Introduction of the Zero-Sequence Stray Flux as a Reliable Diagnostic Method of Rotor Electrical Faults in Induction Motors. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 6016–6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftakis, K.N. Detection of Early Inter-Turn Stator Faults in Induction Motors via Symmetrical Components—Current vs Stray Flux Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Detroit, MI, USA, 11–15 October 2020; pp. 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, T.; Arkan, M. Reliable Detection of Broken Bar Fault through Negative Sequence of Stray Flux in Induction Motors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–18 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, I.; Bouzid, M.B.K.; Khil, S.K.E.; Champenois, G. Robust Novel Indicator To Distinguish between an Inter-Turn Short Circuit Fault and Load Unbalance in PMSG. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaq, M.S.; Shaikh, M.F.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.B. Reliable Airgap Search Coil Based Detection of Induction Motor Rotor Faults Under False Negative Motor Current Signature Analysis Indications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 3276–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Voltage Unbalance: Power Quality Issues, Related Standards and Mitigation Techniques: Effect of Unbalanced Voltage on End Use Equipment Performance, Final Report, Report No. 1000092; EPRI: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aladag, I.; Goktas, T.; Arkan, M. Discernment of Static Eccentricity and Electrical Load Unbalance Currents through Space Vector Stray Flux in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator based Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ELECO), Bursa, Turkiye, 30 November–2 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, T.; Zafarani, M.; Lee, K.W.; Akin, B.; Sculley, T. Comprehensive Analysis of Magnet Defect Fault Monitoring Through Leakage Flux. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 53, 8201010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarani, M.; Goktas, T.; Akin, B.; Fedigan, S.E. An Investigation of Motor Topology Impacts on Magnet Defect Fault Signatures. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).