Abstract

Industrial visual inspection demands high-precision anomaly detection amid scarce annotations and unseen defects. This paper introduces a zero-shot framework leveraging multimodal feature fusion and stabilized attention pooling. CLIP’s global semantic embeddings are hierarchically aligned with DINOv2’s multi-scale structural features via a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, enabling effective cross-modal knowledge transfer for capturing macro- and micro-anomalies. A Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module adaptively aggregates discriminative representations using self-generated anomaly heatmaps, enhancing localization accuracy and mitigating feature dilution. Trained solely in auxiliary datasets with multi-task segmentation and contrastive losses, the approach requires no target-domain samples. Extensive evaluation across seven benchmarks (MVTec AD, VisA, BTAD, MPDD, KSDD, DAGM, DTD-Synthetic) demonstrates state-of-the-art performance, achieving 93.4% image-level AUROC, 94.3% AP, 96.9% pixel-level AUROC, and 92.4% AUPRO on average. Ablation studies confirm the efficacy of DMA and SAP, while qualitative results highlight superior boundary precision and noise suppression. The framework offers a scalable, annotation-efficient solution for real-world industrial anomaly detection.

1. Introduction

A core challenge in automating smart manufacturing is the failure of conventional inspection methods to reliably detect novel or rare defect types. The rise of deep learning has shifted the mainstream approaches toward supervised learning [1,2,3] or unsupervised learning based on modeling normal samples [4,5,6]. Although these supervised methods have achieved remarkable performance, their effectiveness inherently relies on extensive annotated samples for each target category. In real-world industrial scenarios, the heavy dependence on large amounts of labeled data poses a significant bottleneck, making it economically prohibitive and often impractical, especially for rare or novel defect types. It is noteworthy that such challenges of ‘class imbalance’ and ‘domain shift’ are pervasive across industrial diagnostics. For instance, in vibration-based fault diagnosis, the Joint Collaborative Adaptation Network (JCAN) [7] effectively tackled these issues for rolling bearings through multi-source domain adaptation. Our work addresses these analogous challenges (generalizing to unseen classes (extreme domain shift) and detecting rare anomalies (class imbalance), but specifically within the visual inspection domain under a zero-shot learning paradigm. The proposed zero-shot framework is designed specifically to overcome this limitation by eliminating the need for any target-domain annotated samples. This is particularly true for rare or novel defect types, where acquiring sufficient high-quality annotations is often costly, time-consuming, or even impractical. More critically, models trained in a conventional manner can only recognize predefined defect categories and remain incapable of identifying new types of anomalies that may emerge during production, greatly limiting the adaptability and scalability of intelligent defect detection systems.

To overcome these fundamental limitations, zero-shot anomaly detection (ZSAD) [8] has emerged as a promising new paradigm. The core idea of ZSAD is to enable models to recognize previously unseen object categories without relying on any annotated samples during training. This is achieved by introducing auxiliary information in a shared semantic space, which helps characterize both known and unknown categories, thereby facilitating knowledge transfer from known to unknown classes. Current ZSAD methods often leverage pre-trained vision-language models (VLMs) due to their strong generalization capabilities. Pioneering approaches such as WinCLIP [8] directly utilize pre-trained VLMs with hand-crafted text prompts to identify anomalies. AnomalyCLIP [9] addresses ZSAD by fine-tuning VLMs on an auxiliary anomaly detection dataset containing annotated anomalies. Crane [10] modifies the CLIP visual encoder through context-guided prompt learning and attention refinement to improve ZSAD performance. Despite these advances, significant challenges remain when dealing with complex industrial defects, which often exhibit both micro- and macro-scale characteristics that are difficult to capture effectively with existing methods. Further analysis reveals three major challenges in current ZSAD approaches: First, the lack of effective multi-scale feature fusion hinders the simultaneous capture of macro and micro anomalies. Second, although large-scale models like CLIP possess powerful global representation capabilities, they are inherently ill-suited for dense prediction tasks such as segmentation, which limits their ability to capture fine-grained features and leads to degraded performance in detailed recognition. Third, achieving effective cross-modal alignment remains difficult due to the representational gap between visual and textual features. These issues significantly constrain the practical performance of ZSAD in real industrial applications. To address these issues and pave the way for a more practical and scalable inspection system, this paper develops an integrated zero-shot anomaly detection framework based on multimodal feature fusion and stabilized attention pooling. The main contributions of this framework are threefold:

- The study proposes hierarchical multimodal feature refinement network architecture. By introducing a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, our approach achieves deep integration of CLIP’s global semantic representations and DINOv2’s multi-scale local structural features, thereby effectively overcoming the fundamental challenge of simultaneously capturing both macroscopic structural anomalies and microscopic textural deviations that have plagued existing methods.

- We design a Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module, which uses anomaly heatmaps as prior guidance for feature aggregation. Combined with a lightweight attention mechanism, the SAP module effectively refines contextual information and substantially enhances the representational capacity of anomalous regions, thereby mitigating the feature blurring issue commonly associated with standard pooling operations in anomaly detection.

- Extensive experiments on seven industrial anomaly detection benchmarks demonstrate that our method achieves remarkable performance improvements. It attains an average AUROC of 93.4% and an average AP of 94.3% in image-level detection tasks, along with an average AUROC of 96.9% and an average AUPRO of 92.4% in pixel-level segmentation tasks. These results comprehensively outperform existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, setting a new benchmark in the field of zero-shot anomaly detection.

2. Related Work

Supervised Anomaly Detection Methods: Supervised anomaly detection methods [11,12] leverage labeled normal and abnormal samples to learn a decision boundary that clearly distinguishes between different categories. By incorporating known anomaly information, these methods can construct a tighter and more accurate description boundary for normal samples, thereby enhancing the ability to identify anomalous states. Compared to unsupervised approaches, the supervised paradigm typically achieves superior detection performance. However, its effectiveness heavily depends on annotation quality and imposes stricter requirements on the completeness and accuracy of the training data. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Methods: These methods learn solely from normal samples of the target category. By exploiting the intrinsic structure and distribution of the data, they automatically identify “outliers” that deviate from the dominant patterns. Commonly used techniques include: distribution-based methods [13,14], which model standard statistical distributions through network training to facilitate anomaly detection; knowledge distillation algorithms based on the teacher–student framework [15,16,17], which have demonstrated excellent performance in anomaly detection tasks; and feature memory bank-based anomaly detection algorithms [18,19,20], which primarily rely on the model’s memorization of normal sample features during training to detect and localize anomalies. Although both supervised and unsupervised anomaly detection methods have shown promising performance in various scenarios, they often exhibit limitations when normal samples are scarce during the training phase. In contrast, this study aims to develop a general-purpose zero-shot anomaly detection model capable of directly identifying anomalies in unseen categories without requiring any training samples. Zero-Shot Anomaly Detection: With the development of numerous vision-language models (VLMs), promising zero-shot capabilities to have been demonstrated. Among these, the CLIP model [21] aligns images and text through contrastive learning, enabling image retrieval and classification from textual prompts. This class of methods has excelled in zero-shot and few-shot classification tasks. However, CLIP exhibits weaknesses in patch-level alignment and insufficient sensitivity to domain-specific features, limiting its performance in fine-grained anomaly detection tasks. To address this, early studies primarily relied on designing hand-crafted prompt templates [22,23,24]. Nevertheless, such approaches heavily depend on domain expertise, and the quality of prompts is difficult to guarantee. In recent years, an increasing number of works have adopted prompt learning techniques [25,26,27] to automatically optimize prompt embeddings in few-shot settings. For example, APRIL-GAN [22] and CLIP-AD [28] utilized annotated auxiliary anomaly data to enhance CLIP’s performance in zero-shot anomaly detection (ZSAD) by optimizing additional projection layers. Building on this, AnomalyCLIP [9] further explored prompt learning mechanisms by introducing learnable text prompts to better adapt VLMs to ZSAD tasks. To mitigate patch misalignment issues, current strategies include fine-tuning the visual encoder [29,30,31], keeping the visual encoder frozen while refining its attention modules [9,32], or applying deep token tuning in both textual and visual encoders [33]. AdaCLIP [33] jointly optimizes the visual and text encoders by incorporating k-means clustering on dense visual features and adding a learnable linear projection head on top of the visual encoder to improve multimodal feature alignment. Crane [10] focused on modifying the visual encoder architecture, integrating context-guided prompt learning and attention mechanism refinement to further advance zero-shot anomaly detection performance.

3. Proposed Method

A zero-shot anomaly detection framework hierarchically fuses CLIP semantic features with DINOv2 multi-scale structural representations. The Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism aligns modalities via DINOv2 self-similarity and CLIP-guided context. A Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module adaptively aggregates features using self-generated anomaly heatmaps. Multi-task optimization with segmentation and contrastive losses enables precise image- and pixel-level detection without target-domain samples.

3.1. Problem Definition

Let be a pre-trained vision-language model with fixed parameters and let be a source anomaly detection dataset from certain domains. Each image in is provided with an image-level label (y = 1 denotes anomalous and y = 0 denotes normal) and pixel-level annotations (with anomalous regions labeled as 1). Given an input image X and a text description T, the model outputs an image-level anomaly score ŷ (indicating whether the image is anomalous) and a pixel-level anomaly heatmap Ŝ (used for localizing anomalous regions).

3.2. Overall Architecture

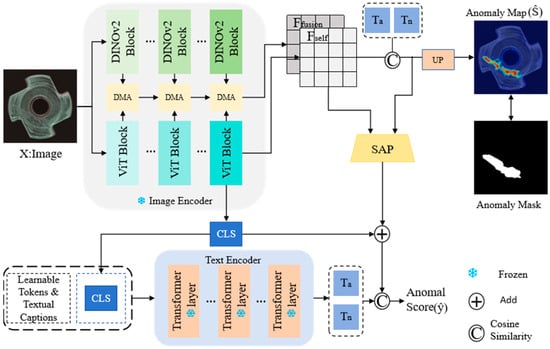

To address the challenges of insufficient multimodal feature utilization and difficult cross-modal alignment in zero-shot anomaly detection (ZSAD), we propose a dual-modality fusion detection mechanism based on an enhanced CLIP architecture. Conventional methods often suffer from limited generalization capability due to the restricted expressive power of unimodal features in the absence of target-domain training samples, while semantic discrepancies between visual and textual modalities further compromise anomaly localization accuracy. To overcome these limitations, the proposed framework (illustrated in Figure 1) builds upon CLIP by hierarchically integrating multi-level visual features extracted from the image encoder with general-purpose visual representations provided by DINOv2. Specifically, we design a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism that facilitates cross-modal interaction through a multi-level weight fusion strategy. Additionally, a Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module is introduced to adaptively aggregate visual features under the guidance of anomaly scores, thereby enhancing the representational capacity of critical regions. The overall pipeline operates as follows: input images and text descriptions are processed through their respective encoders. Images pass through DINOv2 Blocks and ViT Blocks to extract multi-scale features, while text is encoded via Transformer layers to capture semantic information. Features from both modalities interact through the DMA module, producing a refined and discriminative fused representation. The visual features are further enhanced by the SAP module to emphasize potential anomalous regions. Finally, an anomaly heatmap is generated through upsampling, and the interaction between textual and visual features produces classification scores. This integrated approach enables high-precision anomaly detection and localization under zero-shot conditions.

Figure 1.

Overall Network Architecture.

This Figure illustrates the overall structure of the multimodal zero-shot anomaly detection framework based on CLIP and DINOv2. The input image and text description are processed separately through a dual-path image encoder (DINOv2 and ViT) and a text encoder. Features are fused via a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, then enhanced by a Stabilized Attention Pooling (SAP) module to improve the representation of anomalous regions. The framework ultimately outputs an image-level classification score and a pixel-level anomaly heatmap.

3.3. Image Encoder

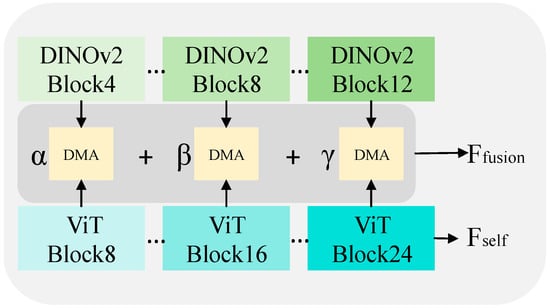

The image encoder in our model adopts dual-backbone architecture for feature extraction (as illustrated in Figure 2), comprising a DINOv2 model, a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) module, and a Vision Transformer (ViT) module, forming a hierarchical feature extraction network. Both the DINOv2 and ViT models extract multi-scale features from shallow, middle, and deep layers, which are subsequently fused through the DMA module. Given an input image, the encoder outputs a global embedding [CLS] for classification, along with local embeddings and for segmentation. The global representation, derived from the [CLS] (Classification) token, corresponds to the [CLS] token from the forward pass of the CLIP visual transformer, capturing image-level features aligned with textual semantics. The local embeddings are derived from the fusion of multi-level features extracted from DINOv2 and ViT, while represents the self-attention features obtained during the forward propagation of the CLIP visual transformer. Specifically, the DINOv2 model (with 12 blocks) yields shallow, middle, and deep features from its 4th, 8th, and 12th layers, respectively. The ViT-L model (with 24 blocks) provides multi-scale features from the 8th, 16th, and 24th layers. Corresponding hierarchical features from both models are integrated via the DMA module. The fusion process is governed by three learnable parameters—α, β, and γ—which adaptively weight the contributions of shallow, middle, and deep features, respectively, to form the final fused representation . After training on the dataset, the model’s weight parameters converge to: α = 0.5, β = 0.5, γ = 1.0. These results indicate that deep features are assigned the highest weight in the fusion process, highlighting their dominant role in semantic-level anomaly discrimination.

Figure 2.

Detailed view of the image encoder.

In contrast, shallow and mid-level features contribute equally to the fusion, jointly providing essential structural and textural details. This weight distribution aligns with the original intention of multi-scale feature fusion, demonstrating the model’s ability to adaptively integrate visual representations from different levels. Such integration enhances the cooperative perception of both macro-defects and micro-anomalies, thereby improving detection generalization under zero-shot settings.

3.3.1. Dual-Modality Attention Mechanism (DMA)

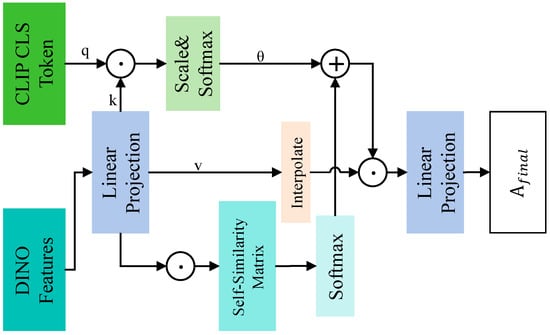

A core challenge in zero-shot anomaly detection is bridging the representational gap across different modalities to achieve effective alignment. Specifically, the semantically rich but spatially abstract features from CLIP, the fine-grained structural features from DINOv2, and the discrete textual embeddings from prompts originate from distinct representation spaces, making direct fusion suboptimal. Existing methods that simply concatenate or add these features overlook this inherent discrepancy. To address this, the paper proposes a Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, which facilitates semantic-guided cross-modal interaction to adaptively integrate structural features and semantic concepts, thereby enhancing the model’s representational capacity for complex anomalies. As illustrated in Figure 3, the DMA mechanism consists of three main steps: computation of DINO self-similarity weights, computation of CLIP global guidance weights and adaptive feature fusion and reconstruction. First, the local features from DINOv2 are projected into the same dimension as the Transformer module via a linear projection layer (dino_proj). Then, we compute a spatial self-similarity matrix (where N = H × W) from the projected DINO features, which captures intrinsic contextual relationships within the image:

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of DMA structure.

Here, δ is a scaling factor and ε is a biasing hyperparameter. μ is defined as the mean value of the pre-scaled similarity matrix (). The term ε∙μ acts as a global bias that centers the similarity scores, preventing the Softmax function from saturating and thus facilitating stable gradient flow during training. The values for δ and ε were determined empirically through initial pilot studies on a validation set. In our experiments, we set δ = 3.0 and ε = 1.2. It is worth noting that the model’s final performance was found to be robust to small variations (±20%) around these chosen values, indicating that the DMA mechanism is not overly sensitive to these specific hyperparameters. Simultaneously, we leverage the global category embedding output by the CLIP text encoder as a query, and compute its similarity with the projected DINO features to generate a CLIP-guided attention map:

where reflects which local regions are most relevant to the global semantic context. The two attention weights are then fused using a learnable scaling factor to produce the final attention map :

This fused attention weight is upsampled to the original spatial size via bilinear interpolation and applied to the Value vectors for feature aggregation.

Finally, the aggregated features are passed through a standard projection layer (proj) to produce the output. Through this process, the DMA module dynamically balances self-similarity based on internal structure and global guidance based on external semantics, enabling more precise and robust feature fusion.

3.3.2. Text Encoder

The text encoder in our framework serves to provide a more discriminative foundation of semantic concepts for the model. By constructing text representations for both “normal” and “anomalous” states, this module offers critical support for subsequent visual-text cross-modal alignment. To enhance the model’s generalization capability to unseen categories and improve parameter efficiency, our framework departs from the conventional approach of manually designing text templates for each specific object category. Instead, we adopt a category-agnostic learnable prompt mechanism. This approach guides the model to learn generic visual-semantic patterns of anomalies, thereby significantly improving its adaptability in cross-category and cross-domain scenarios. Furthermore, our method defines only two sets of globally learnable prompt tokens, corresponding to the “normal” () and “anomalous” () states, rather than learning independent prompt vectors for each category. This strategy substantially reduces the number of parameters requiring training, decreases reliance on large-scale annotated data, effectively mitigates overfitting, and enables the model to focus more on extracting essential characteristics of anomalies. In practice, these learnable prompt tokens are concatenated with fixed descriptive text (such as “object” and “damaged object”) to form the input sequence, which is then fed into the text encoder. This approach, combined with the generic visual representations provided by DINOv2 in the visual encoder, constitutes a fundamental basis for the zero-shot generalization capability of our method. For the text feature input given the concatenated input sequence, it is processed by a Transformer-based text encoder. The [EOS](End-Of-Sequence) token embedding from the final layer is taken as the global text feature vector:

The resulting feature vectors serve as semantic anchors for similarity comparison with the global image features extracted by the visual encoder. The entire model is trained by optimizing an image–text contrastive loss based on these comparisons.

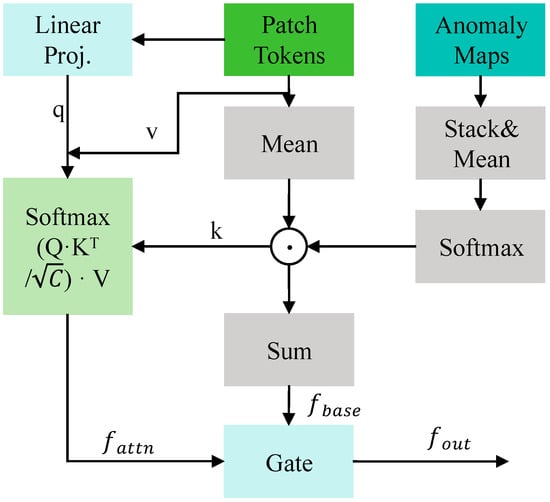

3.3.3. Stabilized Attention-Based Pooling Module (SAP)

Accurately focusing on anomalous regions within complex backgrounds and generating robust image-level representations are critical for classification performance in anomaly detection tasks. Traditional global pooling operations, such as average pooling or max pooling, often treat all image regions equally, which can dilute anomalous responses with abundant normal background features, thereby reducing the discriminative power of the overall representation. Although attention mechanisms can partially alleviate this issue, in a zero-shot setting, the lack of training supervision may lead to unstable and unreliable attention weights, making it difficult to consistently highlight true anomalous regions. To address this, we propose a Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module (as shown in Figure 4). The core idea is to leverage the anomaly heatmap generated by the model itself as prior guidance to explicitly address the issue where features from extensive normal backgrounds can dilute the often weaker and more localized discriminative signals from anomalous regions, which is a common challenge in anomaly detection. Through a gated fusion mechanism, the module adaptively integrates base features with refined contextual features, producing a stable and highly discriminative image-level representation that emphasizes anomalies while retaining global context. Given a sequence of patch tokens extracted by the visual encoder and their corresponding multi-scale anomaly heatmaps , the module first fuses and normalizes the anomaly maps, converting them into spatial attention weights :

where reflects the probability of each spatial location belonging to an anomalous region.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of SAP structure.

The image-level feature is then generated through two pathways: Base Feature Pathway: A weighted sum of patch tokens using the anomaly weights yields a base feature representation:

ensuring that visual information from anomalous regions is emphasized and preserved. Attention Refinement Pathway: A learnable query vector is produced via linear projection of the weighted average of patch tokens. A lightweight attention mechanism further refines the context information most relevant to anomalies:

capturing long-range dependencies and integrating global context. Finally, a learnable gating parameter , constrained to [0, 1] via a Sigmoid function, adaptively fuses the outputs of the two pathways to produce the stabilized image-level representation:

This enables the model to dynamically balance the contributions of the direct weighting and attention refinement pathways based on the input sample, ultimately outputting a robust feature vector that incorporates both salient anomaly information and global context for subsequent anomaly scoring.

3.3.4. Loss Function

The study objective is to simultaneously achieve pixel-level anomaly region segmentation and image-level anomaly classification. To this end, we design a two-stage loss function that combines segmentation loss and classification loss through a weighted sum, thereby optimizing the training of both the prompt learner and the stabilized pooling module. The total loss is defined as follows:

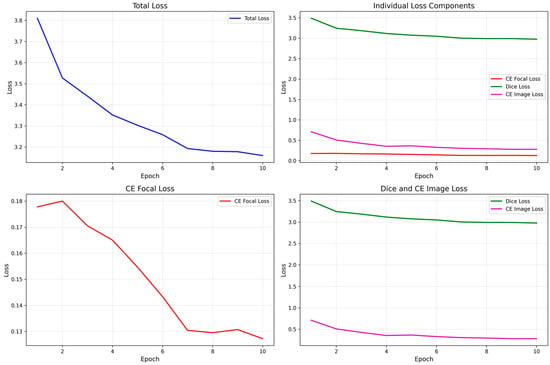

where is a hyperparameter that balances the importance of the two loss terms, set to 0.2 in our experiments. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-task loss function and the stability of the training process, we plot the loss curves during training, as shown in Figure 5. The total loss decreases rapidly and converges gradually with training epochs, indicating a stable and effective optimization process. Among the two core components, the segmentation loss (composed of Focal Loss and Dice Loss) decreases sharply in the early stages and then stabilizes, reflecting the rapid improvement in pixel-level localization capability. The classification loss (image-level contrastive loss) also shows a steady declining trend, demonstrating successful alignment between image-level semantic representations and textual prompts. The coordinated decrease in all loss terms confirms the rationality of the overall framework and the synergy of the multi-task learning strategy.

Figure 5.

Training loss curve.

It shows the changes in total loss (Total Loss), the components of segmentation loss (Focal Loss, Dice Loss), and classification loss (CE Image Loss) with respect to the number of training epochs.

3.3.5. Segmentation Loss

The segmentation loss is designed to optimize the anomaly heatmap generated by the model, ensuring pixel-level alignment with the ground-truth anomaly mask. It consists of two complementary loss functions that jointly improve region matching and boundary accuracy:

To address the extreme foreground-background class imbalance between anomalous and normal pixels, we employ Focal Loss [34]. Built upon standard cross-entropy, this loss introduces adjustable focusing parameters that reduce the weight of easily classified samples, thereby forcing the model to focus on hard-to-classify anomalous pixels. To enhance the model’s ability to capture the morphological structure of anomalous regions (particularly improving the overlap between predicted regions and ground-truth masks) we further incorporate Dice Loss [35]. This loss is based on the Dice coefficient and directly optimizes the intersection-over-union (IoU) between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth, proving especially effective for segmenting small anomalous regions.

3.3.6. Classification Loss

The classification loss optimizes the global image representation to align with the correct text prompts (“normal” or “anomalous”) in a shared semantic space. The paper adopts a standard image–text contrastive loss formulated as cross-entropy:

denotes the global image feature enhanced by the stabilized attention pooling module, and represents the text feature generated by the text encoder. This loss encourages the embedding of a normal image to be closer to the “normal” prompt embedding, and that of an anomalous image to the “anomalous” prompt, thereby achieving image-level anomaly classification. By jointly optimizing the segmentation loss and the classification loss, our model learns both fine-grained pixel-level anomaly localization and accurate image-level anomaly discrimination.

4. Experiments

The framework is evaluated on seven industrial anomaly detection benchmarks, including MVTec AD and VisA, under a zero-shot protocol. Image-level metrics (AUROC, AP, F1-max) and pixel-level metrics (AUROC, AUPRO, F1-max) assess classification and segmentation performance. Comparisons with state-of-the-art methods demonstrate superior results. Ablation studies and qualitative visualizations validate the contributions of the DMA and SAP modules.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To comprehensively evaluate the zero-shot anomaly detection and segmentation performance of the proposed method, we conducted experiments on multiple public industrial anomaly detection benchmark datasets. These datasets cover a variety of industrial scenarios and defect types, offering diversity and representativeness.

4.1.1. Datasets

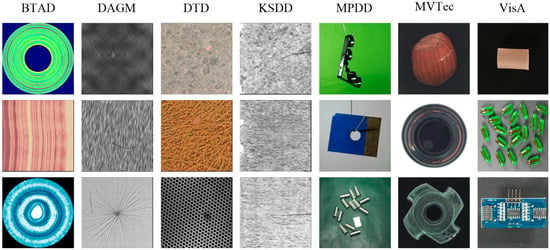

This study used the following seven widely recognized industrial anomaly detection datasets: MVTec AD [36]: A standard benchmark in industrial anomaly detection, comprising 15 categories (5 textures and 10 objects) with high-resolution images and pixel-level annotations. It includes various typical industrial anomalies such as structural deformations and surface contaminations and is widely used for algorithm performance validation. VisA [37]: A large-scale industrial anomaly detection dataset containing 12 categories and over 10,000 images, known for its complex object structures and diverse defect types. With balanced positive and negative samples and high detection difficulty, it is particularly suitable for evaluating model robustness in complex multi-object scenarios. BTAD [38]: Focused on three types of products in real industrial inspection scenarios, with defects typically being small and low-contrast. It emphasizes the model’s ability to perceive subtle anomalies and generalize in real-world environments. MPDD [39]: A metal part defect dataset containing six categories of surface defects. Acquired under challenging imaging conditions with specular reflections and low-contrast interference, it is mainly used to evaluate model performance in difficult optical environments. KSDD [40]: Specialized in detecting linear defects such as scratches on steel surfaces. The defects are slender and faint, requiring high fine-grained perception and edge localization accuracy. DAGM [41]: A synthetically generated texture defect dataset with 10 categories. Despite being computer-generated, it features complex background textures and low-contrast defects, making it widely used for validating anomaly detection and anti-interference capabilities in textured backgrounds. DTD-Synthetic [42]: A synthetic anomaly dataset based on the Describable Texture Dataset (DTD), primarily used to test model generalization to unseen texture types and adaptability to non-target domain features. To more intuitively demonstrate the sample characteristics and challenges of each dataset, Figure 6 provides example images from different categories across the seven datasets. These examples cover various scenarios including object and texture defects, real and synthetic data, and macro/micro defects, providing a solid foundation for validating method generalization.

Figure 6.

Examples of samples from different categories in each dataset.

Following the established zero-shot learning paradigm (Crane), our evaluation employs a strict leave-one-dataset-out protocol to assess generalization to unseen industrial domains. This involves two complementary experimental settings:

Main Zero-shot Evaluation: To comprehensively evaluate generalization, the model is trained on the MVTec AD dataset and then tested on all other six target datasets (VisA, BTAD, MPDD, KSDD, DAGM, DTD-Synthetic) without any fine-tuning. All results for these six datasets in Table 1 and Table 2 are obtained under this setting.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of image-level anomaly detection (Image-AUROC).

Table 2.

Performance comparison of image-level anomaly detection (Image-AP).

Symmetric Evaluation for Fair Comparison on MVTec AD: To provide results on the common MVTec AD benchmark for a direct and fair comparison with state-of-the-art methods (which also report zero-shot performance on MVTec AD), a symmetric experiment is conducted. Here, the model is trained on the VisA dataset and evaluated on the MVTec AD dataset. All comparative results for MVTec AD presented in this paper are obtained under this symmetric setting.

This protocol ensures that the model is never trained on data from the target test domain, fulfilling the core requirement of zero-shot evaluation.

It is important to distinguish between the requirements for rigorous academic evaluation and those for practical deployment. The use of multiple datasets herein is to comprehensively validate the zero-shot generalization ability of our framework. In a real-world industrial application, only a single instance of the pre-trained model (e.g., the one trained on MVTec AD) is required as a ready-to-use solution for inspecting various unseen products, eliminating the need for end-users to gather multiple auxiliary datasets.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

The paper adopted widely recognized metrics to quantitatively evaluate model performance from both image-level and pixel-level perspectives. Image-Level Evaluation (for anomaly classification, determining whether an entire image contains anomalies): Image-Level AUROC: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve computed from anomaly classification scores. It measures the overall ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous images. Values closer to 1 indicate better performance. Image-Level AP: Area Under the Precision-Recall curve. This metric is more sensitive to class imbalance between positive and negative samples. Image-Level F1-Score (Image-F1): Harmonic mean of precision and recall, calculated at the optimal threshold. It reflects the balance between classification, accuracy and completeness. Pixel-Level Evaluation (for anomaly segmentation, localizing anomalous regions within an image): Pixel-Level AUROC: AUROC computed based on anomaly scores of all pixels. It is the most used metric for evaluating anomaly segmentation performance. Pixel-Level AUPRO: Area Under the PRO (Per-Region Overlap) curve, which emphasizes the importance of connected regions. This metric offers a more balanced evaluation across defects of varying sizes compared to pixel-level AUROC and is a key indicator in anomaly segmentation. Pixel-Level F1-Score: The F1-score calculated at the pixel level under the optimal threshold. It directly reflects the overlap quality between predicted anomalous regions and ground-truth masks. Through comprehensive evaluation using these metrics, we provide an objective and in-depth analysis of the proposed method’s performance.

4.1.3. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted on a Linux system using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU for computation in Chufei, Shanghai, China.. The software environment was configured with Python 3.9 and CUDA 12.1. The proposed architecture was implemented within the PyTorch 2.3.0 framework. The core backbone utilizes the pre-trained CLIP ViT-L/14@336px model as the base for both visual and text encoders. Model training employed the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 8, and a total of 10 training epochs. Computational Efficiency Analysis. To assess the practical deployment potential of the proposed framework, we provide a comprehensive computational analysis. The dual-backbone architecture (CLIP ViT-L/14 + DINOv2 ViT-L) contains approximately 436 million parameters in total. On an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU, the framework processes a 336 × 336 input image in 43.4 ± 18.3 ms on average, achieving a throughput of 23 frames per second. While this overhead is higher than single-model baselines, it enables the robust zero-shot generalization capability demonstrated in our experiments. The visual encoder constitutes the majority of parameters (312.7 M, 71.7%), followed by the transformer (85.1 M, 19.5%) and embedding layers (37.9 M, 8.7%).

4.2. Comparative Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted comprehensive comparisons with state-of-the-art zero-shot anomaly detection approaches across multiple datasets. The compared methods include those based on pre-trained vision-language models, such as WinCLIP [8], AnoVL [23], AnomalyCLIP [9], AdaCLIP [33], and Crane [10]. WinCLIP, as a pioneering work, directly utilizes the pre-trained CLIP model with hand-crafted text prompts for zero-shot anomaly detection and segmentation. AnoVL introduces learnable prompt tokens and performs lightweight fine-tuning of the visual encoder to enhance cross-modal alignment. AnomalyCLIP adapts CLIP on an auxiliary anomaly dataset and employs learnable prompts to improve sensitivity to anomalous semantics.

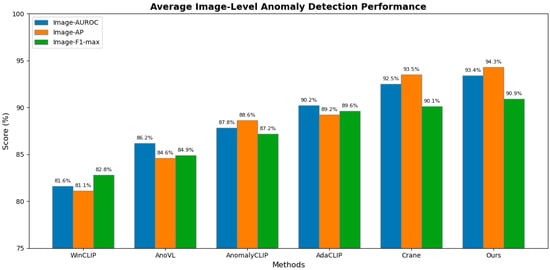

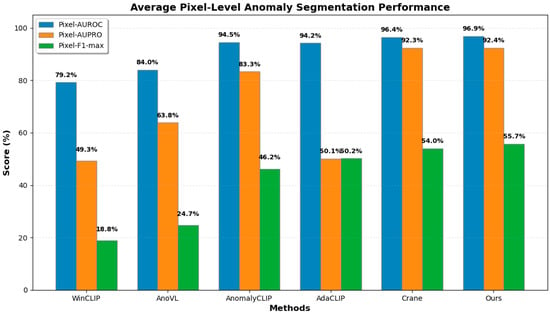

AdaCLIP uses k-means clustering on visual features and jointly optimizes text and visual projection heads for finer cross-modal feature adaptation. Crane further enhances feature discriminability in anomaly detection by incorporating context-guided prompt learning and attention mechanism refinement. The study strictly followed the zero-shot evaluation protocol: none of the compared methods used any training samples from the target datasets. Quantitative results are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 (image-level) and Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 (pixel-level), with the best results for each metric within a specific dataset highlighted in bold. To provide an intuitive and holistic overview of comparative performance, we visualize the average results across all seven benchmarks in Figure 7 (image-level) and Figure 8 (pixel-level). These grouped bar charts clearly demonstrate that our method consistently achieves superior or highly competitive performance across all three key metrics at both the image and pixel levels.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of image-level anomaly detection (Image-F1-max).

Table 4.

Pixel-level anomaly segmentation performance comparison (Pixel-AUROC).

Table 5.

Pixel-level anomaly segmentation performance comparison (Pixel-AUPRO).

Table 6.

Pixel-level anomaly segmentation performance comparison (Pixel-F1-max).

Figure 7.

Comparison of average image-level anomaly detection performance.

Figure 8.

Comparison of average pixel-level anomaly segmentation performance.

The quantitative comparison results demonstrate the comprehensive performance of the proposed method in multi-dataset zero-shot anomaly detection tasks. Overall, our method achieves the most outstanding performance across the board. As shown in the last rows of Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, it ranks first in the average values of all evaluation metrics at both the image level and pixel level.

The grouped bars represent the mean Image-AUROC, Image-AP, and Image-F1-max scores across seven benchmark datasets (MVTec AD, VisA, BTAD, MPDD, KSDD, DAGM, DTD-Synthetic). Our method achieves the highest scores in both AUROC (93.4%), AP (94.3%) and F1-max (90.9%), demonstrating superior classification performance under the zero-shot setting.

The grouped bars show the mean Pixel-AUROC, Pixel-AUPRO, and Pixel-F1-max scores across all datasets. Our method attains the best overall performance, particularly excelling in Pixel-AUROC (96.9%) and maintaining competitive Pixel-AUPRO (92.4%), which reflects its precise localization capability for anomalous regions. Specifically, it reaches 93.4% in image-level AUROC, 94.3% in image-level AP, and 90.9% in image-level F1-max, while the corresponding pixel-level metrics reach 96.9%, 92.4%, and 55.7%, respectively. These results indicate that the proposed multimodal fusion framework and stabilized pooling strategy work synergistically to enhance the model’s overall performance in both classification and segmentation tasks.

The paper method exhibits strong generalization capabilities when confronted with diverse challenges. It achieves significant performance improvements on both the MPDD dataset, which contains complex specular reflections, and the BTAD dataset, which features extremely subtle defects. For instance, it attains an image-level AUROC of 84.1% on the MPDD dataset, significantly outperforming all other methods compared. This validates the effectiveness of the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism in integrating fine-grained structural information from DINOv2 and global semantic information from CLIP, enabling adaptation to a variety of complex industrial scenarios. More importantly, the performance improvement is not only evident in image-level classification tasks but also significant in the more challenging pixel-level segmentation task, achieving synergistic enhancement in both classification and segmentation performance. For instance, the pixel-level F1-max score increased from 54.0% (achieved by the current state-of-the-art method Crane) to 55.7%. This result confirms that the stabilized attention pooling module enhances the discriminative power of image-level representations through anomaly-weighted feature aggregation, while the multi-scale features involved in the process also support the generation of high-precision pixel-level anomaly heatmaps. Our method demonstrates a clear advantage over the similarly complex Crane model. It consistently outperforms Crane across the vast majority of datasets and evaluation metrics. This improvement is primarily attributed to the incorporation of additional DINOv2 multi-scale visual representations and a dual-modality attention fusion mechanism in the model architecture, which provides richer and more robust visual features compared to relying solely on CLIP. In the image-level anomaly detection task on the MPDD dataset, our method achieved an AUROC of 84.1%, representing an absolute improvement of 3.1 percentage points and a relative gain of 3.8% over the previous best method (Crane, 81.0%). This marks one of the most substantial performance breakthroughs observed in all experiments. The MPDD dataset is characterized by challenging imaging conditions, featuring various metal surface defects alongside pervasive specular reflections and low-contrast interference, which place high demands on the robustness and discriminative capability of models. The outstanding performance of the proposed multimodal fusion framework in such an environment fully validates the effectiveness of the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism in complex visual scenes. By integrating CLIP’s semantic abstraction capacity and DINOv2’s multi-scale structural features, the DMA significantly enhances the perception and identification of subtle anomalies against noisy backgrounds, effectively mitigating false detections and missed inspections caused by reflective interference in metal surface inspection. Compared to previous methods relying on a single modality, our approach demonstrates superior generalization and practical value. These results not only highlight the technical advantages of the method in challenging industrial scenarios but also provide strong support for its application in real-world defect detection. Systematic comparative experiments demonstrate that the proposed method establishes a new performance benchmark in zero-shot anomaly detection and segmentation tasks, with its effectiveness, generalization capability, and robustness thoroughly validated.

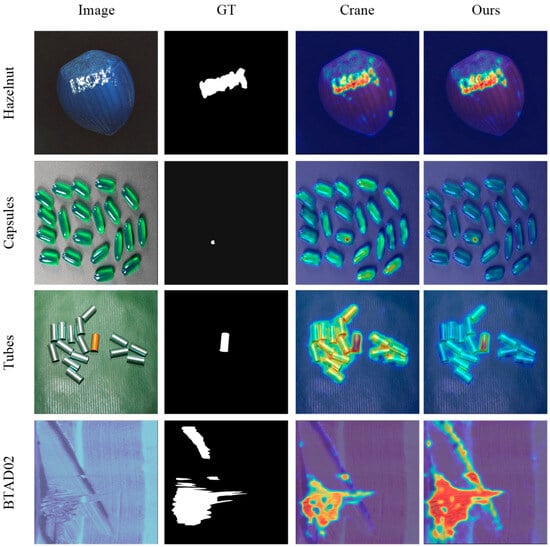

4.3. Qualitative Analysis

To more intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this section provides a qualitative comparison with the current state-of-the-art approach, Crane. Representative samples were selected from multiple categories (including Hazelnut, Capsules, Tubes, and BTAD02) for visualization. These samples cover a variety of challenging industrial scenarios such as local structural damage, fine contamination, color anomalies, and missing structures. The comparative results are illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Qualitative results display, compared with the segmentation results of Crane.

As shown in the first row, for the local structural damage on the top of the hazelnut, although the Crane method can roughly detect the anomalous region, its generated heatmap is diffused with unclear boundaries and exhibits some false activation in the bottom normal area. In contrast, our method produces a more compact and concentrated anomalous region that aligns more closely with the ground truth (GT). The heatmap accurately focuses on the damaged edges while effectively suppressing background responses, validating the effectiveness of the Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module in aggregating critical features and suppressing background noise. The second row presents a case of minor contamination at the bottom-left corner of a capsule. The heatmap generated by the Crane method covers the entire capsule area without precisely localizing the anomaly, potentially leading to missed detection. Our method, however, demonstrates high sensitivity to this subtle anomaly, producing a clear and high-confidence peak in the heatmap that accurately indicates the defect location. This result confirms that the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, by integrating fine-grained visual features from DINOv2, significantly enhances the model’s ability to detect minute anomalies. The third row displays a tube with color variation anomalies. Although the Crane method can identify the anomalous tube, its heatmap covers an excessively large area without accurately delineating the anomaly and exhibits low-intensity responses in normal regions. Our method not only correctly identifies the anomalous tube but also clearly outlines the anomaly’s contour, demonstrating superior shape representation and significantly reducing false detections. This highlights the synergistic effect of the hierarchical feature fusion strategy and the DMA module: through multi-scale feature integration and semantic guidance, the model achieves enhanced robustness in complex backgrounds. The fourth row shows a scratch defect on a part surface. The anomalous region predicted by the Crane method is partially incomplete and deviates noticeably from the ground truth. In comparison, the anomalous region output by our method closely matches the GT in both shape and spatial extent, providing strong evidence that our overall framework achieves high precision in segmenting complex structural defects. These visualization results are consistent with the quantitative analysis in Section 4.2, collectively demonstrating the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed multimodal hierarchical fusion framework, the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism, and the Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module in industrial anomaly detection and segmentation tasks.

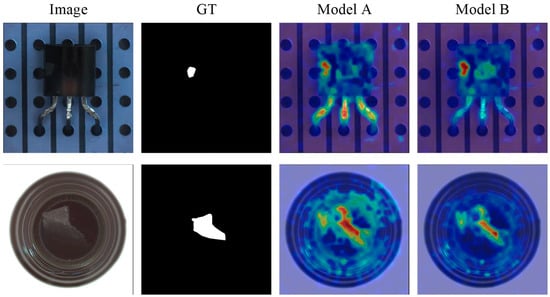

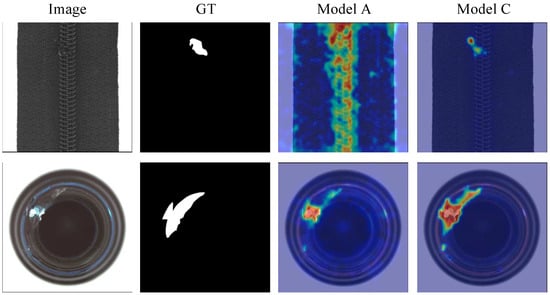

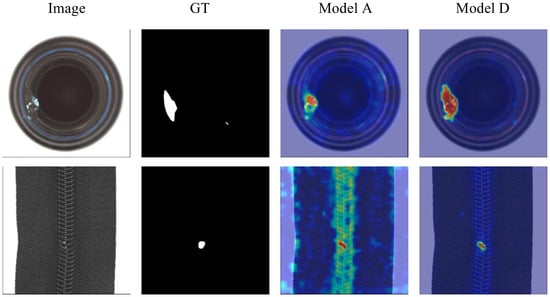

4.4. Ablation Study

To thoroughly validate the effectiveness and contribution of each core component in the proposed method, we conducted a systematic ablation study. All experiments were performed under the same zero-shot setting on the MVTec AD and BTAD datasets, with image-level AUROC and AP serving as the primary evaluation metrics. To establish a strong baseline for comparison, Model A implements a straightforward feature fusion strategy by directly summing the deep features of CLIP and DINOv2, alongside incorporating prompt learning. This summation-based fusion serves as a representative baseline to benchmark against more sophisticated fusion mechanisms. Subsequent variants incrementally incorporate the proposed components: first, hierarchical fusion of CLIP and DINO (B); then the addition of the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) module (C); and finally, the Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module (D). The experimental results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Ablation Study Results.

The significant performance improvement from Model A (summation baseline) to Model B (hierarchical fusion) and further to Model C (with DMA) unequivocally demonstrates that the proposed hierarchical and attention-driven fusion strategies are substantially more effective than simple, linear feature combinations. This validates the core premise that overcoming the representational gap between modalities requires a more nuanced, guided approach like DMA, rather than naive fusion.

As shown in Model B, compared to the simple summation of deep features (Baseline A), the hierarchical fusion strategy for CLIP and DINOv2 yields a significant performance improvement, with average image-level AUROC and AP increasing by 1.0% and 1.1%, respectively. This result indicates that merely introducing multimodal features without an effective fusion mechanism is suboptimal. The proposed hierarchical fusion strategy better preserves and synergistically leverages CLIP’s semantic abstraction and DINOv2’s fine-grained structural information, establishing a higher-quality feature foundation for subsequent processing. The improvement is particularly pronounced on the MVTec AD dataset (AUROC +2.0%), demonstrating the effectiveness of this strategy in handling complex industrial objects. Introducing the Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism on top of hierarchical fusion (Model C) leads to a consistent further improvement, with average AUROC and AP reaching 95.3% and 97.5%, respectively. This validates the core value of the DMA module: it dynamically computes cross-modal feature correlations and utilizes CLIP’s global contextual information to guide and refine DINOv2’s local feature representations, thereby achieving more precise cross-modal feature alignment and enhancement. Finally, with the incorporation of the Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module, our full model (Model D) achieves the best performance, with average metrics of 95.6% AUROC and 97.9% AP. The SAP module adaptively fuses base features and attention-refined features through a learnable gating mechanism, producing a more discriminative image-level global representation. The gain on the BTAD dataset (AP +0.7%) indicates that this module plays a critical role in enhancing classification confidence for subtle defects. In summary, the ablation study fully demonstrates the necessity and effectiveness of each component in the proposed multimodal fusion framework. To provide an intuitive understanding of the impact of each module, we present visual comparisons from the ablation study. Figure 10 illustrates the difference in anomaly localization capability between the baseline model (A) and the model with hierarchical fusion (B). It can be observed that Model B produces more concentrated heatmaps with reduced false detections, validating the role of the hierarchical fusion strategy in improving feature quality.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison between Model A and Model B.

Figure 11 compares the segmentation results of Model A and Model C (with the DMA module). The addition of the DMA module results in clearer boundaries and more accurate responses in anomalous regions, particularly for structurally complex defects, further confirming the effectiveness of cross-modal attention in refining feature alignment.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison between Model A and Model C.

Figure 12 presents a comparison of anomaly segmentation results between the baseline model (A) and the complete model (D) incorporating the Stabilized Attention Pooling (SAP) module, using the same sample set. It can be observed that the heatmaps generated by the complete model (D) significantly outperform those of the baseline model (A) in terms of anomaly region integrity, boundary clarity, and alignment with the ground truth (GT) annotations. The baseline model (A) often exhibits weak responses in anomalous regions, blurred boundaries, or partial omissions, particularly in defects with complex structures or low contrast.

Figure 12.

Visual comparison between Model A and Model D.

In contrast, the complete model (D), enhanced by the SAP module, demonstrates an improved ability to focus precisely on anomalous areas, suppress background noise, and produce more compact and confident anomaly heatmaps. This leads to a notable improvement in the accuracy and robustness of pixel-level anomaly localization. These visual results further confirm the critical role of the SAP module in enhancing the representation of anomalous regions and boosting the overall performance of the model.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel zero-shot anomaly detection framework tailored for industrial visual inspection, effectively addressing the critical challenges of limited annotated data and the emergence of unknown defect types. By integrating the global semantic representations of CLIP with the multi-scale structural features of DINOv2 through hierarchical architecture, the proposed method achieves robust cross-modal alignment and enhanced feature discriminability. The Dual-Modality Attention (DMA) mechanism dynamically fuses modality-specific cues by leveraging DINOv2 self-similarity and CLIP-guided semantic context, enabling simultaneous capture of macro-scale structural anomalies and micro-scale textural deviations. Complementing this, the Stabilized Attention-based Pooling (SAP) module utilizes self-generated anomaly heatmaps as prior guidance to adaptively aggregate discriminative features, significantly mitigating the dilution effect of normal background regions and improving both image-level classification and pixel-level accuracy. Trained under a multi-task paradigm combining pixel-wise segmentation loss (Focal + Dice) and image–text contrastive loss, the framework operates without any target-domain samples, relying solely on auxiliary anomaly datasets for generalization. Comprehensive experiments across seven challenging industrial benchmarks (MVTec AD, VisA, BTAD, MPDD, KSDD, DAGM, and DTD-Synthetic) demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, achieving average image-level AUROC of 93.4%, AP of 94.3%, and pixel-level AUROC of 96.9% with AUPRO of 92.4%. These results consistently surpass prior zero-shot methods, including WinCLIP, AnomalyCLIP, AdaCLIP, and Crane. Ablation studies validate the incremental contributions of hierarchical fusion, DMA, and SAP, while qualitative visualizations reveal superior boundary delineation and reduce false activations in complex scenarios. Despite its demonstrated robustness and generalization ability, the performance of the proposed framework is inherently coupled with the capabilities and biases of its pre-trained foundation models (CLIP and DINOv2). This dependency implies that its effectiveness may be challenged in three primary types of scenarios: (1) highly domain-specific textures not well represented in the upstream training data; (2) significant illumination variations or extreme lighting conditions that alter the visual appearance beyond the models’ learned invariance; and (3) the detection of extremely small-scale anomalies, where the limited discriminative signal approaches the information-theoretic limit and becomes indistinguishable from image noise. These represent challenging yet important frontiers for industrial visual inspection. Future work will therefore focus on mitigating these limitations through strategies such as domain-invariant prompt optimization, lightweight visual encoder adaptation, and the exploration of high-resolution architectures to enhance robustness across a wider and more demanding spectrum of industrial environments.

Author Contributions

J.J.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. Z.H.: Methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. A.W.: Conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing—review & editing. K.A.-B.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision (corresponding author). K.W.: Software, validation, data curation, visualization. P.Z.: Resources, validation, writing—review & editing. X.C.: Funding acquisition, resources, project administration, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52372420), the Joint Fund of Zhejiang BaiMa Lake Laboratory (Grant No. LBMHZ25F030002), the Scientific Research Foundation of Hangzhou City University (Grant No. X-202404), the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2024C01039), the Leading Goose R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2025C02242), and the Ningbo Science and Technology Innovation 2035 Key Technology Breakthrough Program (Grant No. 2024Z177).

Data Availability Statement

The complete datasets analyzed in this paper can be downloaded via the following links (all links were accessed on 20 November 2025): https://drive.google.com/file/d/12IukAqxOj497J4F0Mel-FvaONM030qwP/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U0MZVro5yGgaHNQ8kWb3U1a0Qlz4HiHI/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cLkZs8pN8onQzfyNskeU_836JLjrtJz1/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/19Kd8jJLxZExwiTc9__6_r_jPqkmTXt4h/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/13UidsM1taqEAVV_JJTBiCV1D3KUBpmpj/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/1f4sm8hpWQRzZMpvM-j7Q3xPG2vtdwvTy/view?usp=drive_link; https://drive.google.com/file/d/1em51XXz5_aBNRJlJxxv3-Ed1dO9H3QgS/view?usp=drive_link.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, S.Z.; Fu, T.T.; Song, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Qi, M.H.; Hua, C.C.; Sun, J. A lightweight semi-supervised distillation framework for hard-to-detect surface defects in the steel industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 297, 129489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; He, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, G.; Wan, A.; Cheng, X. Enhancing multi-scale learning with dual-path adaptive feature fusion for mixed supervised-industrial defect detection. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, F.Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, L.J.; Yin, J.J. Semi-supervised semantic segmentation with confidence-driven consistency learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 128965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xu, K.; Zhao, D.L.; Li, H.J.; Jin, L.; Liu, C.N.; Xu, P.J. PNG: An adaptive local-global hybrid framework for unsupervised material surface defect detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 293, 128711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Pan, Y.F.; Gao, R.X.; Guo, Z.C.; Zhang, C.Q.; Zhao, P. DAE-SWnet: Unsupervised internal defect segmentation through infrared thermography with scarce samples. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 766–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.R.; Chen, S.Y.; Peng, L.F.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ou, Y.C.; Peng, J.W. Contrastive self-supervised subspace clustering via KAN-based multi-view fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 128995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, T. A joint collaborative adaptation network for fault diagnosis of rolling bearing under class imbalance and variable operating conditions. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 69 Pt B, 103931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Zou, Y.; Kim, T.; Zhang, D.; Ravichandran, A.; Dabeer, O. WinCLIP: Zero-/Few-Shot Anomaly Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Pang, G.; Tian, Y.; He, S.; Chen, J. Anomalyclip: Object-agnostic prompt learning for zero-shot anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7 May 2024; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=buC4E91xZE (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Salehi, A.; Salehi, M.; Hosseini, R.; Snoek, C.G.M.; Yamada, M.; Sabokrpu, M. Crane: Context-Guided Prompt Learning and Attention Refinement for Zero-Shot Anomaly Detections. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Wu, X.J.; Wang, M.Y. Semi-Patchcore: A Novel Two-Staged Method for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection and Localization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3506012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.G.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.L.; Zuo, M.J. Self-Supervised Defect Representation Learning for Label-Limited Rail Surface Defect Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 29235–29246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailanian, M.; Pardo, Á.; Musé, P. U-Flow: A U-Shaped Normalizing Flow for Anomaly Detection with Unsupervised Threshold. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2024, 66, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, G.; Shun, I.; Kazuki, K. CFLOW-AD: Real-Time Unsupervised Anomaly Detection with Localization via Conditional Normalizing Flows. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Li, X. Anomaly Detection via Reverse Distillation from One-Class Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzner, K.; Heckler, L.; König, R. EfficientAD: Accurate Visual Anomaly Detection at Millisecond-Level Latencies. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Sadjadi, N.; Baselizadeh, S.; Rohban, M.H.; Rabiee, H.R. Multiresolution Knowledge Distillation for Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Guan, H.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Spratling, M.; Wang, Y.F. Registration Based Few-Shot Anomaly Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Gao, L.; Li, X.; Wen, L. Industrial Image Anomaly Localization Based on Gaussian Clustering of Pretrained Feature. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6182–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Song, B.C. CFA: Coupled-Hypersphere-Based Feature Adaptation for Target-Oriented Anomaly Localization. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 78446–78454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/radford21a.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Chen, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J. A Zero-/Few-Shot Anomaly Classification and Segmentation Method for CVPR 2023 VAND Workshop Challenge Tracks 1&2: 1st Place on Zero-shot AD and 4th Place on Few-shot AD. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, J.; Li, X. AnoVL: Adapting Vision-Language Models for Unified Zero-shot Anomaly Localization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.15939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, C.; Cheng, Y.; Du, Z.; Gao, L.; Shen, W. Segment Any Anomaly without Training via Hybrid Prompt Regularization. arXiv-CS-Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, M.M.; Sanchez, E.; Bulat, A.; Da Costa, V.G.T.; Snoek, C.G.M.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Martinez, B. Bayesian Prompt Learning for Image-Language Model Generalization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Learning to Prompt for Vision-Language Models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Etemad, A. Consistency-guided Prompt Learning for Vision-Language Models. arXiv-CS-Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01195. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Tian, G.; He, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. CLIP-AD: A Language-Guided Staged Dual-Path Model for Zero-Shot Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–9 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Cao, J.; Ye, P.; Ding, Y.; Tu, C.; Chen, T. ClipSAM: CLIP and SAM collaboration for zero-shot anomaly segmentation. Neurocomputing 2025, 618, 129122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Tao, X.; Prasad, M.; Shen, F.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, X.; Ding, G. VCP-CLIP: A Visual Context Prompting Model for Zero-Shot Anomaly Segmentation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Pang, G. Toward Generalist Anomaly Detection via In-Context Residual Learning with Few-Shot Sample Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, X.; Chen, C.; Qu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ma, L. PromptAD: Learning Prompts with only Normal Samples for Few-Shot Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Frittoli, L.; Cheng, Y.; Shen, W.; Boracchi, G. AdaCLIP: Adapting CLIP with Hybrid Learnable Prompts for Zero-Shot Anomaly Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Li, W.; Vercauteren, T.; Ourselin, S.; Jorge Cardoso, M. Generalised Dice Overlap as a Deep Learning Loss Function for Highly Unbalanced Segmentations. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Proceedings of the DLMIA ML-CDS 2017, Québec City, QC, Canada, 14 September 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, P.; Fauser, M.; Sattlegger, D.; Steger, C. MVTec AD—A Comprehensive Real-World Dataset for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Jeong, J.; Pemula, L.; Zhang, D.; Dabeer, O. SPot-the-Difference Self-supervised Pre-training for Anomaly Detection and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Verk, R.; Fornasier, D.; Piciarelli, C.; Foresti, G.L. VT-ADL: A Vision Transformer Network for Image Anomaly Detection and Localization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 30th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Kyoto, Japan, 20–23 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezek, S.; Jonak, M.; Burget, R.; Dvorak, P.; Skotak, M. Deep learning-based defect detection of metal parts: Evaluating current methods in complex conditions. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems and Workshops (ICUMT), Brno, Czech Republic, 25–27 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernik, D.; Sela, S.; Skvarc, J.; Skočaj, D. Segmentation-based deep-learning approach for surface-defect detection. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 31, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, W.; Tobias, H. Weakly supervised learning for industrial optical inspection. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium of the German Association for Pattern Recognition (DAGM 2007), Heidelberg, Germany, 12–14 September 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aota, T.; Tong, L.T.T.; Okatani, T. Zero-shot versus Many-shot: Unsupervised Texture Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).