Abstract

Texture recognition is a fundamental task in computer vision, with diverse applications in material sciences, medicine, and agriculture. The ability to analyze complex patterns in images has been greatly enhanced by advancements in Deep Neural Networks and Vision Transformers. To address the challenging nature of texture recognition, this paper investigates the performance of several pre-trained vision architectures for texture recognition, including both CNN- and transformer-based models. For each architecture, multi-level features are extracted from early, intermediate, and final layers, concatenated, and fed into a trainable Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) classifier. The architecture is thoroughly evaluated using five publicly available texture datasets, KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, DTD, and Soil, with MLP hyperparameters determined through an exhaustive grid search on one of the datasets to ensure optimal performance. Extensive experiments highlight the comparative performance of each architecture and demonstrate that aggregating features from different hierarchical levels improves texture recognition in most cases, outperforming even architectures that require substantially higher computational resources. The study also shows the particular effectiveness of transformer-based models, such as BEiTv2, in achieving state-of-the-art results on four of the five examined datasets.

1. Introduction

Texture is ubiquitous in natural images and serves as a crucial visual cue for various image analysis tasks, such as image segmentation, retrieval, and shape analysis from texture. In computer vision and image processing, texture classification is a fundamental problem, playing an essential role across a wide range of applications. These include medical image analysis [1], where texture recognition helps in the retrieval of medical images for accurate diagnosis. In remote sensing [2], texture analysis can be used to classify land types and detect environmental changes in satellite or aerial imagery. In agriculture [3], texture recognition aids in predicting soil texture, which plays a key role in crop management and land use planning. Object recognition [4] relies on texture to distinguish between objects, improving detection and classification in complex environments. As textures are integral to these applications, their accurate recognition significantly enhances the performance of automated systems in fields such as healthcare, environmental monitoring, and industrial applications.

Architectures based on traditional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been widely employed in image recognition tasks, significantly improving the analysis of material and object appearance through transfer learning on pre-trained models across large datasets [5,6,7]. These methods offer computational efficiency during inference, yet retraining the backbone remains computationally demanding. Techniques like Global Average Pooling (GAP) have been employed to aggregate features, providing robust representations resistant to spatial transformations [6,8]. However, these approaches often rely on large datasets for effective end-to-end training with deep CNN architectures. At the same time, CNNs may struggle with complex material patterns due to inherent spatial biases, lacking robustness to translation, rotation, and scale variations. Nevertheless, recent advancements in convolutional network design continue to push the boundaries of CNN-based models. Modern architectures such as ConvNeXt [9] demonstrate that carefully rethinking convolutional building blocks—inspired by insights from Transformer-based models—can substantially enhance representational capacity and scalability without abandoning the efficiency advantages of convolution. These next-generation CNNs narrow the performance gap with vision transformers while retaining strong inductive biases, efficient inference, and compatibility with established transfer learning workflows for material and object recognition tasks.

Vision Transformer (ViT) architectures offer a promising alternative to CNNs by effectively capturing global context in images. ViTs have begun to dominate the computer vision literature, challenging traditional CNNs, particularly in image classification tasks [10,11]. However, their lack of spatial inductive biases, which are crucial for capturing fine-grained local patterns typical in textures, limits their effectiveness. Despite these limitations, ViT-based models remain highly promising candidates for texture recognition tasks due to their strong capacity for modeling long-range dependencies and contextual relationships. Their ability to capture complex global structures suggests significant potential in scenarios where texture information is distributed across spatial regions. However, further investigation is needed to adapt and optimize transformer architectures for texture-focused applications, particularly in integrating local detail sensitivity with their global feature modeling strengths

The motivation of this work is to investigate the potential of modern deep learning-based vision architectures for the challenging task of texture recognition. By leveraging their hierarchical feature extraction capabilities and integrating a trainable MLP classifier, this study explores a lightweight and transferable multi-layer feature aggregation strategy specifically tailored to texture analysis. The proposed method aims to harness the complementary representations captured at different depths of these architectures—from early low-level features to mid-level structural patterns and high-level semantic abstractions. By aggregating and combining these multi-level features through GAP and feature concatenation, the model enhances its discriminative capacity and adapts the representational power of both CNN- and transformer-based backbones to the unique complexities of texture recognition.

The main contributions of the presented work are as follows:

- This work investigates various pre-trained vision architectures specifically for texture recognition tasks. By adding and training a MLP for classification, a comprehensive comparison of their performance is presented across five widely utilized datasets: KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, DTD, and Soil. This comparative analysis highlights the strengths of different architectures and informs future choices in model selection for texture recognition.

- An architecture for texture recognition is proposed, effectively aggregating data representations from the extracted feature maps of various pre-trained vision models without the need for fine-tuning. In particular, we use features from the early layers of the vision architectures where the information is rich in visual cues (i.e., pixel-like), from the mid layer where geometric cues are more present, and from the output where the features are the most semantic rich. Such combination of different layer features can boost the need for more dedicated texture-related features. The proposed architecture also incorporates a trainable MLP as the classification head, with optimal hyperparameters determined through an exhaustive grid search on one of the selected datasets.

- The proposed architecture demonstrates the highest accuracy across four texture benchmarks, outperforming all state-of-the-art methods built on CNN backbones. The superiority holds not only against models with substantially fewer parameters, such as ResNet18 (12 M) and ResNet50 (26 M), but also against models with comparable computational complexity to ours (197 M), such as ConvNeXt-L (198 M), as well as more resource-intensive models like ConvNeXt-L-22k (198 M) and ConvNeXt-XL-22k (350 M). Additionally, insights into the model’s behavior are provided through confusion matrices, along with an ablation study examining the impact of different architectural components, further clarifying the advantages of the proposed method in texture recognition.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 offers an overview of related works in the field of texture recognition. Section 3 outlines the proposed architecture and its implementation. In Section 4, the utilized datasets, experimental protocols, and the model selection process are discussed, along with comparisons to state-of-the-art methods. This section also presents confusion matrices and an ablation study on different architectural components. It also addresses the limitations of the proposed work. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and contributions of the paper.

2. Related Works

Traditional methods for texture recognition have predominantly relied on manually crafted features designed to maintain invariance to various factors, such as scale, illumination, and translation. Among the earliest and most influential approaches is the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) [12], which captures second-order statistical dependencies between pixel intensities to describe texture contrast, homogeneity, and entropy. Several prominent techniques for texture analysis include the Rotation Invariant Feature Transform (RIFT) [13], which utilizes histograms of gradient orientations, and the Bag-of-Visual-Words (BoVW) framework [13], which aggregates local texture patches into visual words. The Vector of Locally Aggregated Descriptors (VLAD) [14] and the Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [15] are also widely used, with SIFT focusing on detecting local extrema in scale-space. Another classical family of methods employs Gabor Filter Banks (GFB) [16], which model the human visual system’s response to texture by analyzing images at multiple scales and orientations through band-pass filtering. Other notable methods include Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [17], which ensure invariance to grayscale and rotation.

Recently, there has been a significant increase in the adoption of CNNs for texture feature extraction, based on their success in computer vision. This trend reflects the wider shift toward deep learning techniques in texture analysis. Notable algorithms include the Locality-Sensitive Coding Network (LSCNet) [18], the Deep Encoding Pooling Network (DEPNet) [19], and the Deep Texture Encoding Network (DeepTEN) [20]. These approaches have enhanced texture recognition by incorporating learned encodings into CNN architectures, resulting in improved performance across diverse datasets. Zhai et al. [6] developed MAPNet, a model for learning visual attributes in texture recognition that employs a multi-branch architecture for iterative attribute learning and spatially-adaptive GAP for feature aggregation. In their follow-up study [5], they introduced DSRNet, which includes a dependency learning module to identify spatial relationships among texture primitives and extract structural details. Peeples et al. [21] introduced HistRes, a texture classification network that combines traditional histogram features with deep learning techniques. By substituting the GAP layer, HistRes improves accuracy by directly extracting histogram information from the output feature map. Xu et al. [22] developed FENet, which employs hierarchical fractal analysis to identify the fractal characteristics of spatial arrangements found in CNN feature maps. Mao et al. [23] utilized the deep Residual Pooling Network (RPNet) for texture recognition, combining a residual encoding module that preserves spatial details with an aggregation module to generate orderless features. Chen et al. [7] introduced CLASSNet, a CNN module that employs Cross-Layer Aggregation to capture statistical self-similarity in texture images. This is achieved through a unique feature aggregation method using a differential box-counting pooling layer. Zhai et al. [24] introduced the Multiple Primitives and Attributes Perception (MPAP) network, which extracts features by combining bottom-up structural information with top-down attribute relationships in a cohesive multi-branch framework. Chen et al. [25] developed the Deep Tracing Pattern encoding Network (DTPNet), which analyzes feature maps from various backbone layers. This network encodes local patches using binary codes and combines them into a histogram-based global feature representation. Scabini et al. [26] developed Random encoding of Aggregated Deep Activation Maps (RADAM), a texture recognition method that uses a Randomized Autoencoder (RAE) to encode outputs from various depths of a pre-trained backbone. This approach generates a feature representation for a linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) without requiring backbone fine-tuning. Florindo et al. [27] proposed a fractal-based pooling method to enhance CNNs for texture recognition using differential box-counting fractal dimension at the last convolutional layer instead of traditional average pooling.

Despite the superior robustness of ViT architectures compared to CNNs, especially in the presence of noise or image augmentation [28], their use in texture recognition remains limited. A comparative study on various Vision Transformers for feature extraction in texture analysis is detailed in [29]. This study evaluates the effectiveness of pretrained transformer architectures, using k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and SVM for classification, achieving promising results. However, it does not address the utilization of intermediate feature maps extracted from the transformers or the possibility of using a MLP as a classification head, indicating a gap in the existing research. In the comparison of various backbones on ImageNet-1K classification presented in [30], the Swin Transformer achieved higher accuracy than the ViT.

Building on these insights, the current work aims to explore various vision architectures for texture recognition, identify the most effective ones, and propose a method for combining features from different feature maps to effectively encode them for training a standard MLP as the classification head. Although various strategies for multi-layer feature fusion have been proposed in the literature (e.g., [31,32]), we show that even this simple approach of concatenating features from selected layers and training a standard MLP achieves competitive or superior performance.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Method

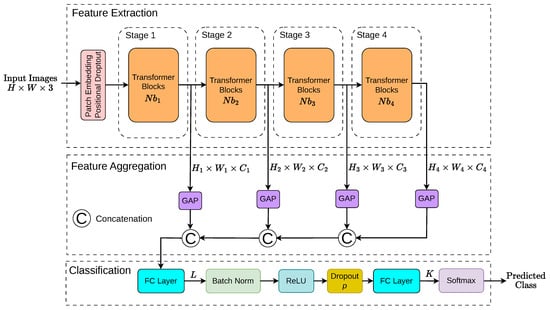

A block diagram illustrating the proposed method is shown in Figure 1. The core idea of the approach is to extract features from four intermediate layers corresponding to different stages of a transformer architecture. This allows the model to leverage multi-level contextual information, capturing both early-stage low-level features and deeper high-level representations. Incorporating features with varying contextual richness introduces diversity, enabling even the less semantically rich early features to contribute meaningful information.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the block diagram of the proposed architecture. Feature extraction is carried out using a pre-trained vision backbone, from which representations are collected at early, intermediate, and final stages. GAP is then applied to each feature map, and the resulting representations are concatenated into a single feature vector, which is subsequently fed into the classifier. The final Classification step includes a MLP layer with L hidden units, Batch Normalization, ReLU activation, and Dropout at a rate of p. The parameters L and p are set to 64 and 0.2, respectively, as determined by a grid search detailed in Section 4.4.

Each extracted feature undergoes GAP to reduce channel dimensionality and generate compact descriptors. These pooled features, which summarize information at different levels of abstraction, are then concatenated into a unified feature vector. To emphasize the discriminative power of the multi-stage representations themselves, the concatenated feature vector is passed through a lightweight MLP classifier. The MLP is intentionally chosen for its simplicity, ensuring that improvements in recognition performance are attributed to the proposed feature pooling and fusion strategy, rather than to additional complexity in the classifier.

This design enables the model to exploit complementary information across transformer layers, resulting in superior performance for texture recognition tasks while preserving architectural clarity and interpretability.

It generalizes across various transformer-based as well as non-transformer based architectures. Many of the evaluated transformer models (e.g., Swin Transformer, MaxViT) are organized into four stages, which motivates the selection of four feature extraction points as depicted on the figure.

Each stage (Stage 1 to Stage 4) contains a specific number of transformer blocks, denoted as , which varies depending on the chosen architecture. The application of GAP is also architecture-dependent, as some intermediate features are 2D spatial maps, while others are flattened sequences, requiring different pooling strategies. Description of each selected vision architectures and its adaptation to the proposed architecture follows in the next sections.

3.2. Swin Transformer

In our experiments, we evaluate the proposed architecture (Section 3.1) on the Swin Transformer [30]. Swin is a hierarchical vision transformer with four stages of windowed self-attention and progressively reduced spatial resolution via Patch Partition (stage 1) and Patch Merging (stages 2–4). Given an RGB input of size , stage-wise feature maps have the canonical shapes:

where for Swin-T/S/B/L, respectively.

Each stage contains multiple Swin Transformer blocks, where each block consists of Layer Normalization (LN), Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention (W-MSA), Shifted Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention (SW-MSA), a MLP, and residual connections [30]. The first stage uses a linear embedding after patch partition, while stages 2–4 downsample via patch merging [30].

In our implementation, we tap the outputs at the end of each stage (i.e., after stages 1–4). These tensors are denoted by and have shapes given above. GAP is applied channel-wise to each , producing pooled vectors with , , , and . Concatenating these vectors yields:

which is fed into the MLP classifier described in Section 3.1. In the conducted experiments we use the Swin-L model with .

3.3. Swin V2 Transformer

SwinV2 [33] retains the four-stage hierarchical structure of Swin but replaces dot-product attention with Windowed Scaled Cosine Attention (W-SCA) and its variant Shifted Windowed Scaled Cosine Attention (SW-SCA), and further introduces log-spaced continuous relative position bias and post-normalization. These modifications improve training stability and scalability to larger model sizes. Each stage consists of repeated SwinV2 blocks (LN–W-SCA/SW-SCA–MLP with residual connections); stage 1 begins with a linear embedding after patch partition, and stages 2–4 downsample via patch merging.

For feature aggregation we apply the same pooling and concatenation strategy described in Section 3.2, i.e., global average pooling of all stage outputs followed by concatenation into a -dimensional vector. In our experiments we use the SwinV2-B model with , which yields a concatenated feature dimension of 1920.

3.4. ConvNeXt

ConvNeXt [9] is a modernized CNN that mirrors the hierarchical four-stage design of Swin-like transformers while remaining purely convolutional. Each stage stacks ConvNeXt blocks composed of depthwise convolutions, Layer Normalization (channel-last), a pointwise convolutional feed-forward with GELU activations, and residual connections. Architectural choices such as larger depthwise kernels, LayerNorm in place of BatchNorm, and reduced nonlinearity budget align ConvNeXt with transformer-era design while preserving CNN efficiency.

We apply the same pooling-and-concatenation strategy as in Equation (1): global average pooling is applied to the outputs of all four stages, and the pooled vectors are concatenated into a -dimensional descriptor fed to the MLP head. In the conducted experiments we use ConvNeXt-Base (), resulting in a concatenated feature of dimension .

3.5. MaxViT

MaxViT [34] introduces a unified hierarchical architecture that integrates multi-axis attention with depthwise convolution in a stage-based design. An input image is first tokenized by a convolutional stem into non-overlapping patches, which form the input to the first stage. Subsequent stages progressively downsample the spatial resolution by a factor of 2 while expanding the channel dimension. Each stage consists of multiple MaxViT blocks, which combine Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution (MBConv) with block-wise and grid-wise Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA), enabling both local and global context modeling.

As with the previous backbones, we apply global average ppoling to the outputs of all four stages and concatenate the resulting vectors as in Equation (1). In our experiments we use MaxViT-Base with , yielding a concatenated feature vector of size , which is fed to the proposed classification head.

3.6. MambaOut

MambaOut [35] is a hierarchical vision model composed of four stages. Except for the first, all stages apply downsampling together with channel expansion, followed by variable number of gated CNN blocks. Unlike the original Mamba [36], which integrates a State-Space Model (SSM) as a token mixer within the blocks, MambaOut discards SSMs and relies entirely on the gated CNNs, motivated by their strong performance on image classification. Specifically, each gated CNN block expands channels to split the feature map into a signal and a gate branch, applies a depthwise convolution to the signal, and recombines them through gated modulation.

For feature aggregation, we follow the same GAP-based strategy as with the other backbones: global average pooling is applied to intermediate feature maps at three progressively deeper points in the network, yielding pooled vectors of size . Concatenation produces a descriptor of total dimension which serves as input to the MLP classifier.

3.7. DeiT3

DeiT3 [11] is a ViT-style encoder: images are divided into patches, each linearly projected to width C, with a learnable class token prepended. The sequence is processed by L Transformer blocks (LN–MHSA–MLP with residuals), augmented by stability refinements such as post-norm, LayerScale, and stochastic depth.

For feature aggregation, we tap four increasingly deeper blocks, apply global average pooling over the patch tokens (excluding the class token), and obtain vectors (). The selection of four blocks was made to provide approximately uniform coverage across the network depth, capturing features from early, intermediate, and deep layers. This design choice maintains consistency with hierarchical architectures such as Swin, which naturally comprise four stages, and enables a fair comparison across different backbone types. A broader discussion on layer-selection strategies for non-hierarchical ViT-based models is provided in Section 4.5. Concatenation forms which is passed to the MLP head. With DeiT3-Base (, ), this results in -dimensional descriptors.

3.8. BEiTv2

BEiTv2 [37] adopts the same ViT backbone design: an input is patch-embedded into a sequence of N tokens of width C, a class token is prepended, and the sequence is processed by L Transformer blocks (LN–MHSA–MLP with residuals). Unlike hierarchical backbones, the token resolution is fixed throughout.

As with DeiT3, we extract outputs from four layers, pool over the token dimension to obtain , and concatenate them into . The choice of four layers balances the need to capture low-, mid-, and high-level features for discriminative texture recognition while avoiding unnecessary computational overhead. Using fewer than four layers was found insufficient to encode the full spectrum of relevant information, whereas using more layers yielded only marginal improvements. The rationale behind this layer-count choice and a systematic evaluation of alternative layer combinations are discussed in Section 4.5. Using the BEiTv2-Base configuration (, ), the aggregated feature has dimension .

4. Experiments

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed method for texture recognition. We begin by describing the implementation details, including benchmark datasets used for evaluation (Section 4.1) and training setup (Section 4.2). Next, we detail the model size selection procedure for hierarchical architectures such as Swin (Section 4.3), followed by the determination of optimal MLP hyperparameters through grid search (Section 4.4), which are considered representative for all models. For non-hierarchical transformer models, a systematic analysis of layer selection is conducted to identify the most effective combination of features for aggregation (Section 4.5). Subsequently, the performance of the proposed method, including feature aggregation and MLP, is compared against baseline models (i.e., using only the backbone with its final-layer features fed into a classification layer) (Section 4.6). Finally, the model considered most effective is evaluated with the proposed architecture against state-of-the-art approaches (Section 4.7).

4.1. Datasets

Evaluation is conducted on five benchmark datasets that capture different forms of textural information. Three of them, KTH TIPS2 b, the Flickr Material Dataset (FMD), and GTOS Mobile, represent material or object centered images that nevertheless exhibit distinctive texture patterns. The remaining two datasets, the Describable Textures Dataset (DTD) and the Soil dataset, contain attribute level texture categories. For the first four datasets, we follow the evaluation protocols described in [26] to ensure full comparability with previous works, while for the Soil dataset we apply the protocol specified in [38]. Below is a brief description of each dataset together with the corresponding training protocol.

- KTH-TIPS2-b [39]: Comprises 4752 images from 11 material categories, including ‘aluminium_foil’, ‘brown_bread’, ‘corduroy’, ‘wool’, etc. Evaluation follows a 4-fold cross-validation protocol with fixed splits, as in [24].

- FMD [40]: Contains 1000 images distributed across 10 categories such as ‘fabric’, ‘glass’, ‘leather’, and ‘wood’. Performance is evaluated using 10 repetitions of 10-fold cross-validation.

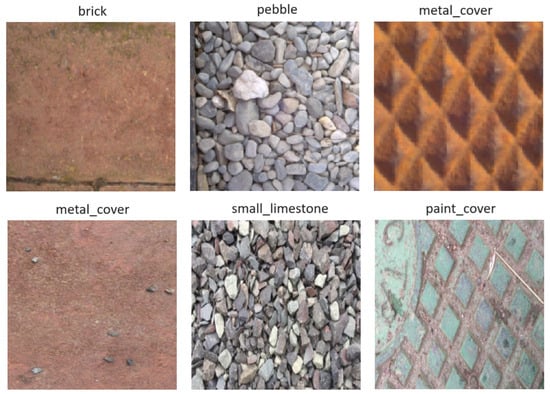

- GTOS-Mobile [19]: Includes 100,011 mobile phone images of 31 outdoor ground material categories such as ‘asphalt’, ‘grass’, ‘pebble’, and ‘sand’. The dataset provides a predefined single train/test split, consistent with prior work [5,6,7,25,41].

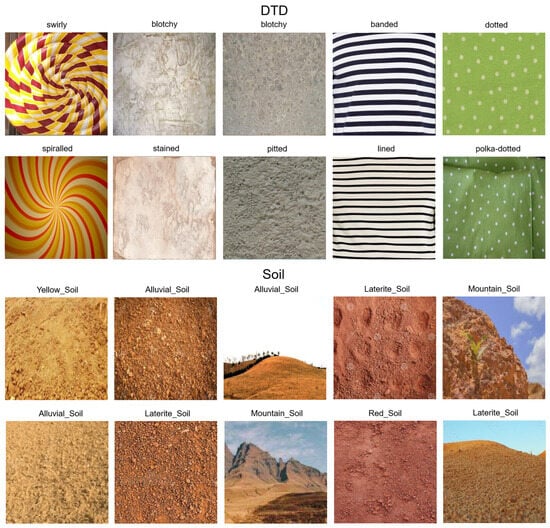

- DTD [42]: Comprises 5640 images labeled with 47 describable texture attributes (e.g., ‘bumpy’, ‘striped’, ’dotted’). Following [26], evaluation is performed using the standard protocol of 10 random train/validation/test splits, and results are averaged over these runs.

- Augmented Soil (Soil) [38]: This dataset originally contains 829 soil images grouped into seven classes (for example ‘Alluvial Soil’, ‘Black Soil’, ‘Laterite Soil’ and others). The dataset is partitioned into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing subsets. Following [38], the training set is augmented and expanded to 3316 images, while the validation and test sets remain at 182 and 178 images respectively. This corresponds to the augmented version of the Soil dataset introduced in [38]. For brevity, in the remainder of the manuscript we refer to this augmented variant simply as “Soil”. This dataset serves as an application-oriented benchmark and is used in the development of an AI-based tool that supports farmers in soil identification and crop selection by incorporating geological and environmental information.

Figure 2 illustrates challenging cases from GTOS-Mobile, where similar categories such as ’brick’ and ’metal_cover’ may be confused due to visual overlap [43]. The selection of the Swin Transformer variant (Section 4.3) and the hyper-parameters for the MLP (L, p) determined on KTH-TIPS2-b (Section 4.4) are reused for FMD, GTOS-Mobile, DTD, and Soil.

Figure 2.

Example images from GTOS-Mobile.

4.2. Implementation Details

The proposed algorithm is implemented using PyTorch-GPU (v2.5.1) [44] on a system equipped with an Intel Xeon E5-2640 v3 CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA; 2.60 GHz, 8 cores), 32 GB of RAM (Kingston, NY, USA), and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Backbone architectures are initialized with pre-trained weights from the PyTorch Image Models library “timm” (v1.0.15) [45]. A batch size of 32 is used throughout training. The architecture is trained for 100 epochs using Adaptive Moment Estimation (ADAM) with momentum and weight decay , optimizing the cross-entropy loss. The learning rate is set to .

To ensure deterministic and fully reproducible experiments, all runs were executed using a fixed global random seed of 42, which serves as the base seed and is applied consistently across Python (v3.10.16), NumPy (v2.0.1), and PyTorch (v2.5.1) CPU and GPU operations. CUDA deterministic execution was enabled, benchmark mode was disabled, and deterministic algorithms were enforced. These settings guarantee that model initialization, data loading order, and all stochastic operations (e.g., shuffling and augmentation) remain fully reproducible.

Regarding the dataset splits and the preparation of training, validation, and test sets, the following procedures were applied to ensure full reproducibility across all experiments:

- KTH-TIPS2-b [39], GTOS-Mobile [19], and DTD [42]: As mentioned in Section 4.1, the dataset splits for training, validation, and testing are used as provided by the original sources, with no additional random partitioning or fold generation applied.

- FMD [40]: Following the widely adopted protocol in [26], performance is evaluated using 10 repetitions of 10-fold cross-validation. For each repetition, a new deterministic seed is derived from the base seed by multiplying it with the repetition index. This seed is then used to initialize all random number generators, including Python (v3.10.16), NumPy (v2.0.1), PyTorch (v2.5.1) CPU and GPU before generating the fold assignment. This procedure ensures that each repetition has a unique fold configuration while maintaining full reproducibility.

- Soil [38]: As mentioned in Section 4.1, we use the augmented version of the Soil dataset provided by the authors [38], in which the training set is expanded via standard augmentation techniques while the validation and test sets remain fixed. The code used for splitting the data and performing the training set augmentation is available in the authors’ repository [46].

All preprocessing steps are applied consistently across datasets. For four of the datasets (KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, and DTD), each input image is resized to pixels. For the Soil dataset, each training image is randomly cropped and resized to the same resolution, following the official preprocessing procedure provided by the dataset authors [46]. Finally, for all datasets, images are normalized using channel-wise mean values of (0.485, 0.456, 0.406) and standard deviations of (0.229, 0.224, 0.225).

Regarding the backbone specification used in our experiments, we provide a detailed description of the pretrained checkpoints and the exact intermediate layers from which features are extracted. The following pretrained models from [45] are employed: Swin (‘swin_large_patch4_window7_224’), SwinV2 (‘swinv2_base_window12_192.ms_in22k’), ConvNeXt (‘convnext_base_in22ft1k’), MaxViT (‘maxvit_large_tf_224.in1k’), MambaOut (‘mambaout_base_wide_rw’), DeiT3 (‘deit3_base_patch16_224.fb_in22k_ft_in1k’), and BEiTv2 (‘beitv2_base_patch16_224.in1k_ft_in22k_in1k’).

For hierarchical architectures (Swin, SwinV2, ConvNeXt, MaxViT, MambaOut), the four intermediate layers available for these backbones are used, while for the remaining backbones (DeiT3 and BEiTv2), features are extracted from layers 2, 5, 8, and 11 according to the layer selection analysis presented in Section 4.5.

4.3. Model Size Selection

Model size selection is considered a preliminary step with the goal of selecting the size of the model that performs the best. From all architectures considered in this work, we select the Swin Transformer as the backbone for model size evaluation in texture classification tasks. Unlike DeiT3 and BEiTv2, Swin employs a hierarchical architecture with shifted-window self-attention. This design provides an effective trade-off between local feature modeling and global context aggregation, and it has demonstrated strong performance across various vision benchmarks while maintaining computational efficiency and scalability. It is also the earliest vision architecture compared to the remaining considered in this work. The configuration for model size evaluation is a Swin transformer for feature extraction, without its classification head. The classification layer is replaced with a set of units corresponding to the dataset’s classes, which are randomly initialized and fully trained for 150 epochs. The other training parameters are the same as those described in Section 4.2. For this analysis, only the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset is considered.

Four primary Swin transformer architectures are commonly recognized for model selection: Swin-T, Swin-S, Swin-B, and Swin-L. Six variants from timm (v1.0.15) [45] were examined: Swin-T, Swin-S (pretrained on ImageNet-1k), Swin-B, Swin-L (pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k), as well as Swin-B-22k and Swin-L-22k (both pretrained on ImageNet-22k). The accuracy results, along with the number of parameters and Giga Multiply-Accumulate Operations (GMACs) for each backbone in this investigation, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance in terms of accuracy (%) of all Swin Transformer variants tested independently (with only the classification layer of the head replaced) on the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset. The best-performing backbone, along with its number of parameters, GMACs, and accuracy are highlighted in bold.

The highest accuracy of 93.4% is achieved by the Swin-L model pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k, making it the preferred choice for the proposed architecture.

The sizes of the remaining backbones were chosen to be comparable to that of the Swin model. The complete list of parameter counts and GMACs is as follows:

- Swin: 195 M parameters, 34.5 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k.

- SwinV2: 228.8 M parameters, 26.2 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-22k.

- ConvNeXt: 197.8 M parameters, 34.4 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k.

- MaxViT: 211.8 M parameters, 43.7 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-21k.

- MambaOut: 94.4 M parameters, 17.8 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-1k.

- DeiT3: 86.6 M parameters, 17.6 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k.

- BEiTv2: 86.5 M parameters, 17.6 GMACs, pretrained on ImageNet-22k and fine-tuned on ImageNet-1k.

It should be noted that MambaOut, DeiT3, and BEiTv2 are approximately half the size of Swin. This choice was intentional: we included smaller models to reduce the risk of overestimating performance and instead provide a more conservative estimate. Moreover, for certain architectures, the implementations available in the timm library [45] do not offer variants with parameter counts closely matching the 195 M scale of Swin.

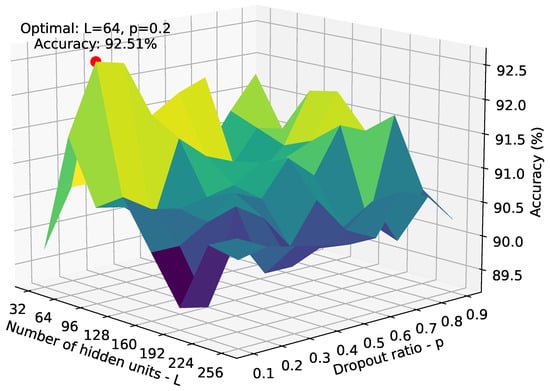

4.4. Grid Search for MLP Parameters

Using the selected Swin transformer model size, a grid search is conducted on the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset (fold 2) to determine the optimal number of hidden units L and dropout ratio p for the classification step of the proposed architecture. The search explores values of L from 32 to 256 in increments of 32, and p from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.1. The resulting plot is shown in Figure 3, showing that the highest accuracy of 92.51% is achieved with and . Therefore, these values for the classification head are used for all backbones.

Figure 3.

3D plot illustrating the grid search for optimal MLP hyper-parameters.

4.5. Analysis of Layer Selection for Non-Hierarchical Models

Non-hierarchical transformer backbones, such as DeiT3 and BEiTv2, contain substantially more than four internal blocks, which makes the choice of layer sampling strategy non-trivial. To determine a principled configuration for extracting multi-level representations, we perform a dedicated analysis using BEiTv2 as a representative ViT-style architecture with a uniform depth structure. Several candidate layer sets were evaluated, each designed to reflect different assumptions about where texture-relevant information may reside within the transformer stack.

The tested configurations include: Equidistant ([3, 6, 9, 12]), Shifted ([2, 5, 8, 11]), Early-heavy ([1, 2, 3, 4]), Late-heavy ([9, 10, 11, 12]), Middle ([4, 5, 6, 7]), Distributed ([1, 4, 7, 10]), and Center+end ([3, 6, 10, 12]). For each set, features from the selected blocks were pooled over the token dimension, concatenated, and used to train the MLP classifier following the parameters described in Section 4.4. The resulting performance for each candidate set on the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset is reported in Table 2, enabling a direct comparison of the effectiveness of the different layer combinations.

Table 2.

Best classification accuracy (%) on KTH-TIPS2-b for different layer selection strategies in non-hierarchical transformers. The best result is highlighted in bold.

The analysis also revealed that sampling fewer than four blocks resulted in insufficient coverage of both local and global patterns, whereas using more than four blocks introduced additional computational overhead with only marginal accuracy gains. Among the tested configurations (see Table 2), the Shifted set consistently yielded the strongest performance, providing a balanced representation of low-, mid-, and high-level texture cues. Based on this empirical evaluation, the Shifted set ([2, 5, 8, 11]) was selected as the default extraction configuration for the non-hierarchical transformer architectures.

4.6. Results Against Baseline

The proposed architecture was evaluated for each backbone using the datasets described in Section 4.1 and following the RADAM protocol [26]. To assess its effectiveness, we compare the proposed method against baseline models that use the same backbone but rely solely on the features extracted from the final output layer. The results are reported in Table 3, where performance is assessed in terms of average classification accuracy (%) and standard deviation.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the proposed architecture using five datasets against baseline. The baseline using only final layer features is noted as No Aggr., while the proposed method using multi-layer aggregation is noted as Aggr. Accuracy (in %) is reported for all experiments. The better result, comparing No Aggr. with Aggr. for each experiment, is given in bold.

For clarity, the table includes both configurations (i) using only the final-layer features of each backbone (denoted No Aggr., or baseline) and (ii) using the proposed feature aggregation from intermediate and final layers (denoted Aggr.). This allows us to directly evaluate the contribution of the aggregation strategy.

The analysis of the results reveals that the benefits of feature aggregation are not uniform across backbones and datasets. In particular, the DeiT3 backbone consistently achieves better performance when using only the final-layer features, suggesting that its most descriptive representations for texture recognition are already concentrated at the output stage. In contrast, other backbones exhibit weaker final-layer representations, and thus benefit from the additional information captured in intermediate layers. Nevertheless, the performance of DeiT3 remains lower than that of most other backbones, indicating that although its most descriptive features are concentrated in the final output layer, this representation alone is insufficient compared to the richer feature sets provided by the alternative architectures.

This behavior can be attributed to the non-hierarchical structure of DeiT3, which differs fundamentally from the hierarchical organization of architectures such as Swin or ConvNeXt. In DeiT3, most discriminative information is concentrated in the final transformer layers, whereas earlier layers primarily capture low-level patch embeddings with limited semantic value. Consequently, concatenating early and late representations may introduce redundancy or noise, slightly degrading performance. This observation suggests that future research should explore specialized aggregation schemes tailored for non-hierarchical architectures.

A further trend can be observed on the GTOS-Mobile dataset, where most backbones perform better without aggregation. This may be attributed to the large size of the dataset combined with high variation and complexity.

To draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the proposed method (Aggr.) compared to the baseline (No Aggr.), we employ a paired design [47]. Examination of the paired differences reveals the presence of clear outliers-most notably for DeiT3, where the Aggr. configuration consistently underperforms-casting doubt on the assumption of normality. Consequently, we predefine the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (one-sided, : Feat. Aggr. > baseline) as our primary statistical analysis, given its robustness to both non-normal distributions and the influence of outliers [48]. For transparency, we also report a paired t-test on the mean difference and a sign test on the direction of change. The results are summarized as follows:

- Wilcoxon signed-rank: The median improvement is +1.0 percentage point (pp), rank-biserial correlation (moderate). One-sided (<0.05) meaning that Aggregation improvement is unlikely due to chance.

- Signed test: 25 out of 35 positives, one-sided p=0.0052 (significant).

- Paired t-test (mean effect): mean pp, , one-sided (not significant). The negative mean is driven by the large, consistent drops for DeiT3 across all five datasets.

Using the paired, robust Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the feature aggregation shows a statistically significant typical-case improvement over the baseline across backbones and datasets (median pp, ). However, the mean improvement is not significant because DeiT3 exhibits large performance decrements with aggregation. Practically, aggregation can be expected to help in most backbone–dataset combinations, but DeiT3 is a notable exception that warrants configuration checks or exclusion.

4.7. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

Table 4 presents the classification accuracy (%) and standard deviation of the proposed architecture compared to several state-of-the-art methods for four of the datasets (KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, and DTD).

Table 4.

Comparison of the proposed architecture’s performance in terms of accuracy (%) and standard deviation (±) against state-of-the-art methods. The backbones are organized into row blocks based on their computational capacity, with their corresponding number of parameters and GMACs. The highest results for each dataset within each block are highlighted in bold, while the overall best results, regardless of the backbone, are underlined. References in square brackets next to each method indicate the original source of the results, and if a second reference is listed, it denotes that the results were taken from the subsequent source.

The evaluation protocols used for four of the datasets (KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, and DTD) align with those adopted in RADAM [26] and several other studies. For the Soil dataset, the protocol from [38] was followed (see the setup and dataset descriptions in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2). The methods in Table 4 are grouped by backbone models and organized based on their computational capacity, indicated by the number of parameters and GMACs.

The proposed method, using the BEiTv2 backbone, delivers the highest accuracy across four datasets: 96.8% on KTH-TIPS2-b, 96.7% on FMD, 91.8% on GTOS-Mobile, and 94.5% on Soil. However, on the DTD dataset, the accuracy of 82.0% is slightly lower than that of the RADAM ConvNeXt-L-22k (84.0%) and RADAM ConvNeXt-XL-22k (83.7%) models.

For the Augmented Soil dataset, to the best of our knowledge, only one article [38] reports several evaluated methods based on fine-tuning. Among these, we compare only with the ViT-B/16 model, which achieved the highest reported accuracy of 91.0% [38]. Our BEiTv2-based method reaches 94.5%, representing a 3.5% improvement. It is also worth noting that the computational characteristics of our model, in terms of GMACs and number of parameters, are very close to those of ViT-B/16, making the comparison balanced and directly relevant.

Regarding the other four datasets, it is worth emphasizing that the proposed BEiTv2-based model is considerably more compact, containing 86.5 million parameters and requiring 17.6 GMACs, compared to 229.8 million parameters and 34 GMACs for ConvNeXt-L-22k and 392.9 million parameters and 61 GMACs for ConvNeXt-XL-22k. Despite having roughly two to three times fewer parameters and computational cost, the proposed approach achieves comparable performance on DTD and surpasses all larger models on the other three benchmarks. This demonstrates the efficiency and competitiveness of the proposed feature aggregation strategy, showing that strong texture recognition performance can be achieved using pre-trained architectures, inter-layer feature aggregation, and a lightweight MLP classifier.

In comparison, models based on smaller backbones such as ResNet18 and ResNet50 offer reasonable accuracy with significantly lower complexity. For instance, ResNet18-based methods like Fractal Pooling achieve 88.3% on KTH-TIPS2-b, while DTPNet reaches 85.7% on FMD and 87.0% on GTOS-Mobile. On DTD, the best-performing ResNet18 method (MPAP) attains 72.4%, using only 11.7 million parameters and 1.8 GMACs. Similarly, ResNet50-based approaches such as Fractal Pooling and MPAP achieve accuracies between 78.0% and 90.7% across datasets, with 25.6 million parameters and 4.1 GMACs, demonstrating a balance between accuracy and efficiency but still lagging behind the proposed method.

While larger RADAM ConvNeXt models show competitive performance, they require substantially more computational resources. For example, RADAM ConvNeXt-L (197.8 M parameters, 34.4 GMACs) achieves 89.3% on KTH-TIPS2-b and FMD, 85.8% on GTOS-Mobile, and 77.4% on DTD, which are lower than the BEiTv2-based results across all datasets. RADAM ConvNeXt-L-22k reaches 91.3%, 95.2%, 87.3%, and 84.0% respectively, outperforming the proposed model only on DTD. Likewise, RADAM ConvNeXt-XL-22k, with 392.9 M parameters and 61 GMACs, attains 94.4%, 95.2%, and 90.2% on KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, and GTOS-Mobile, while achieving 83.7% on DTD, again higher on this dataset but lower elsewhere.

Overall, this comparison highlights that the proposed BEiTv2-based model achieves the best balance between accuracy and efficiency, outperforming all compared methods on four out of five datasets while using significantly fewer parameters and computational cost, although for the Soil dataset the parameter count and computational cost are comparable.

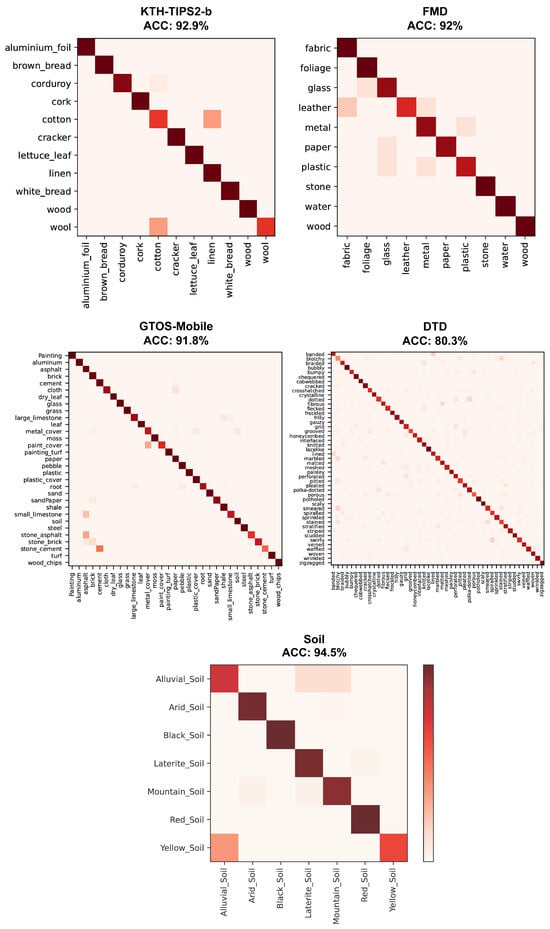

4.8. Detailed Results

Confusion matrices: The effectiveness of the proposed architecture is further evaluated by using the best-performing backbone, i.e., BEiTv2, analyzing the confusion matrices and corresponding accuracies for the worst-case folds of KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, and DTD, while GTOS-Mobile and Soil, both having a single test fold, are examined separately (see Figure 4). In general, the confusion matrices show a strong diagonal pattern, reflecting the algorithm’s strong classification performance.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices and accuracies obtained using the proposed architecture with the BEiTv2 backbone for each dataset. For KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, and DTD, the results correspond to the lowest-accuracy folds, while for GTOS-Mobile and Soil, results are shown from its single available fold. Darker red indicates higher proportion of predictions in a cell.

For the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset, the most frequent confusions are ‘wool’ or ‘corduroy’ predicted as ‘cotton’ and ‘cotton’ misclassified as ‘linen’.

In the FMD dataset, misclassifications include ‘leather’ predicted as ‘fabric’ or ‘metal’, ‘glass’ as ‘foliage’, ‘paper’ as ‘glass’, ‘plastic’ as ‘glass’ or ‘metal’, ‘leather’ as ‘metal’, ‘metal’ as ‘plastic’, and ‘metal’ as ‘plastic’. These mistakes are largely due to similar visual appearances among the classes.

In the GTOS-Mobile dataset the most noticeable misclassifications are ‘stone_cement’ predicted as ‘cement’, ‘stone_brick’ as ‘brick’, ‘small_limestone’, ‘stone_asphalt’, and ‘stone_brick’ confused with ‘asphalt’, and ‘paint_cover’ misclassified as ‘metal_cover’. As with the other datasets, most of these errors involve classes with similar characteristics.

For the DTD dataset, the most prominent misclassification occurs for the blotchy class, which appears as the lightest (i.e., lowest-accuracy) square along the diagonal of the DTD confusion matrix. Representative errors include, but are not limited to, predicting ‘blotchy’ as ‘stained’ or ‘pitted’, ‘banded’ as ‘lined’, ‘dotted’ as ‘polka-dotted’, and ‘swirly’ as ‘spiralled’.

Regarding the Soil dataset, the most notable confusion cases include ‘Yellow Soil’ predicted as ‘Alluvial Soil’, as well as Alluvial Soil as ‘Laterite Soil’ or ‘Montian Soil’.

Confusion cases: Figure 5 presents several confusing cases encountered by the proposed architecture on the KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, and GTOS-Mobile datasets, illustrating typical misclassifications and their visually similar predicted counterparts. Figure 6 provides additional examples of analogous confusion patterns observed in the DTD and Soil datasets, following the same presentation structure and highlighting similar challenges in distinguishing between visually related categories. Most of these pairs of images, which reflect the incorrect classifications, correspond to the highlighted cells in the confusion matrices of the respective datasets previously shown in Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Examples of confusing material categories from the KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, and GTOS-Mobile datasets using the proposed architecture with BEiTv2 backbone. The top section displays misclassified samples with their true labels, whereas the bottom section illustrates their incorrect predictions alongside visually similar samples from the predicted class.

Figure 6.

Examples of confusing material categories from the DTD and Soil datasets using the proposed architecture with a BEiTv2 backbone. The structure and interpretation of the figure follow the same convention as in Figure 5, where the upper section shows misclassified samples with their ground-truth labels, and the lower section presents the corresponding incorrect predictions along with visually similar samples from the predicted classes.

Regarding the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset (see the top pairs of images in Figure 5), the most frequent confusions occur between visually similar categories such as ‘wool’–‘cotton’, ‘cotton’–‘linen’, ‘corduroy’–‘cotton’, ‘brown_bread’–‘white_bread’, and ‘cracker’–’cork’. These pairs share overlapping local texture patterns, including uniform weaves, coarse fiber structures, or porous surfaces, which make their appearance highly similar in isolated patches. As a result, the model often relies on subtle surface cues that are difficult to distinguish even for human observers. Near-duplicate textures across material types further increase ambiguity. For instance, ’linen’ and ’cotton’ exhibit overlapping weave patterns that become almost indistinguishable under uniform lighting and medium-scale zoom. Similarly, irregular porous structures make brown and white bread, as well as cracker and cork, difficult to differentiate.

For the FMD dataset (see the image pairs in the middle of Figure 5), the most frequent misclassifications occur between material pairs that share strong visual overlap in global appearance rather than fine-grained texture cues, such as ‘leather’–‘fabric’, ‘metal’–‘plastic’, ‘paper’–‘glass’, ‘leather’–‘metal’, and ‘glass’–‘cork’. Across these cases, the classifier appears to rely primarily on object-centric shape regularities and specular highlights instead of discriminative micro-texture detail. For example, smooth folds make ‘leather’ visually comparable to ‘fabric’, while polished reflection patterns cause ‘metal’ to closely resemble ‘plastic’ under strong illumination. Similarly, the ‘paper’ lantern is mistakenly associated with a ‘glass’ marble due to their shared rounded shape, despite being structurally different as materials. The reflective golden surface of ‘metal’ and its resemblance in contour to the ‘leather’ sample further encourages confusion. In the rightmost examples, both images depict leaf-shaped objects, even though one is glass and the other is cork. The model fails to separate them because the similarity in overall form dominates over material-specific cues. These findings suggest that the ImageNet-pretrained backbone used in our model is biased toward global shape and object-level features rather than texture-specific representations, which considerably contributes to the observed misclassification patterns. Future work that involves training or fine-tuning the backbone on large-scale texture- or material-oriented datasets could potentially enhance its sensitivity to fine-grained surface cues, ultimately leading to more reliable recognition performance and fewer shape-driven classification errors.

Regarding the GTOS-Mobile dataset, the image pairs shown at the bottom of Figure 5 often exhibit highly similar visual characteristics, making it difficult for the model to distinguish between them accurately.

The subtle variations in local texture and fine-grained patterns pose a significant challenge for correct classification. Specifically, pairs such as ‘stone_cement’–‘cement’, ‘stone_asphalt’–‘asphalt’, and ‘smile_limestone’–‘asphalt’ share almost identical color tones and surface appearance, making them particularly difficult to differentiate. In contrast, pairs like ‘paint_cover’–‘metal_cover’ and ‘sandPaper’–‘brick’ exhibit similarity primarily in their texture and structural patterns rather than color, which also leads to misclassification. Addressing such confusing cases may require improving the model’s sensitivity to subtle differences in both texture geometry and material reflectance, representing a promising direction for future research to further improve robustness and classification accuracy.

For the DTD dataset (see the top pairs of images in Figure 6), the most frequent misclassifications occur between texture categories that share highly similar global structure: ‘swirly’–‘spiralled’, ‘blotchy’–‘stained’, ‘blotchy’–‘pitted’, ‘banded’–‘lined’, and ‘dotted’–‘polka-dotted’. In all cases, the classifier appears to rely predominantly on overall pattern layout, which often overwhelms the finer distinctions that define the official category labels. The ‘swirly’–‘spiralled’ confusion stems from their almost identical rotational geometry: both depict concentric, radiating curves with comparable frequency and curvature, making the subtle differences in pattern uniformity difficult for the model to separate. In the ‘blotchy’–‘stained’–‘pitted’ examples, the surfaces display irregular, uneven textures with overlapping patch-like structures; the lack of distinctive boundaries between tonal blotches, stain marks, and shallow surface pits leads to strong cross-class similarity. The ‘banded’–‘lined’ pair highlights how challenging it is to discriminate between wide-band and narrow-line patterns when both present horizontal black–white striping. Because their global appearance is dominated by parallel high-contrast stripes, the classifier fails to capture the difference in stripe thickness that defines the two categories. Finally, ‘dotted’ samples are often misidentified as ‘polka-dotted’ due to the presence of similarly shaped circular elements; despite the more regular spatial arrangement characteristic of ‘polka-dotted’, the approximate dot distribution in both images makes them visually difficult for the model to separate. Overall, these findings indicate that misclassifications in DTD primarily arise from subtle geometric distinctions within pattern families, where global repetition cues dominate over fine-scale texture characteristics.

For the Soil dataset (see the bottom pairs of images in Figure 6), the misclassified examples mainly involve the pairs ‘Yellow_Soil’–‘Alluvial_Soil’, ‘Alluvial_Soil’–‘Laterite_Soil’, ‘Alluvial_Soil’–‘Mountain_Soil’, ‘Laterite_Soil’–‘Red_Soil’, and ‘Mountain_Soil’–‘Laterite_Soil’. These errors arise from a combination of textural similarity and shape-related cues that appear in the images. The first two pairs, ‘Yellow_Soil’–‘Alluvial_Soil’ and ‘Alluvial_Soil’–‘Laterite_Soil’, show soil surfaces with very similar particle distribution and overall appearance. Their fine-grained textures and close color ranges make them difficult to distinguish even visually, which naturally leads the model to mix these categories. In the ‘Alluvial_Soil’–‘Mountain_Soil’ example, the ‘Alluvial_Soil’ sample resembles a small hillside due to its smooth curved profile, encouraging the model to interpret it as a landscape rather than pure soil texture. A related effect appears in the ‘Mountain_Soil’–‘Laterite_Soil’ pair, where the ‘Laterite_Soil’ image presents a mound-like form that mimics a mountain silhouette despite representing a different soil type. The ‘Laterite_Soil’–‘Red_Soil’ pair illustrates a case dominated by texture and color similarity: both samples share reddish tones and medium-grain roughness, making the boundary between these classes visually subtle. Overall, these results show that misclassifications in the Soil dataset stem from a mixture of textural resemblance and global shape cues within the images. This further indicates that the ImageNet-pretrained backbone tends to emphasize scene-like structures over fine soil-surface characteristics, limiting its ability to resolve closely related soil types.

4.9. Ablation Study

The ablation study of the proposed approach was performed using the Swin backbone on the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset, fold 2, with MLP hyperparameters optimized as described in Section 4.4. This configuration is considered sufficiently representative of the remaining backbones. The study examines partial aggregation of features from different intermediate layers, as well as the effect of removing individual classifier components such as dropout and batch normalization. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Examining the impact of individual components on accuracy (%) within the proposed method using the Swin backbone on KTH-TIPS2-b dataset, fold 2 (the best result is highlighted in bold). A checkmark indicates the presence of the corresponding operation/component, while an ‘✗’ indicates its absence.

When partial aggregation is applied, excluding features from stage f1, the accuracy decreases to 91.16% for stages f2, f3, and f4, and 91.50% when only stages f3 and f4 are aggregated (drops of 1.35% and 1.01%, respectively). Both cases demonstrate the importance of including features from earlier stages, as they provide complementary information that enhances classification performance.

The exclusion of batch normalization has the most drastic effect, reducing accuracy to 56.57% (a drop of near 36%). This underscores its critical role in stabilizing training, preventing exploding or vanishing gradients, and improving generalization. Batch normalization absence causes instability in the training process, leading to significant performance degradation.

Removing ReLU activation results in a smaller decrease in accuracy to 90.40% (a drop of more than 2%). This suggests that although the Swin Transformer’s feature extraction remains effective, the lack of ReLU impairs the model’s ability to learn complex features, leading to a significant reduction in accuracy. However, this drop is less dramatic than the performance drop observed when batch normalization is excluded.

Similarly, excluding dropout leads to an accuracy of 89.82% (a drop of nearly 2.7%). Dropout is a regularization technique that helps prevent overfitting by randomly dropping units during training. Without it, the model becomes more prone to memorizing the training data, which explains the observed performance decline.

Finally, simplifying the classification head by using a single Fully Connected (FC) layer instead of a two-layer MLP results in an accuracy of 91.84%, a drop of nearly 0.7%. This highlights the impact of the MLP structure in optimizing feature utilization and enhancing classification performance. While the simplified FC structure reduces computational cost, it comes at the expense of classification accuracy, highlighting the importance of the two-layer MLP architecture in the proposed method.

4.10. Limitations of the Presented Work

We indicate the following limitations of the proposed work:

- High Computational Resource Requirements: The method achieves superior results across four investigated datasets (KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, and Soil), utilizing the BEiTv2 transformer, which is notably computationally intensive, compared to the older models such as ResNet-50. This high resource demand may restrict the method’s applicability in environments with limited computational capabilities. Future research could explore model compression techniques or the development of lightweight variants to enhance accessibility.

- Simple feature aggregation: While the proposed method relies on a straightforward feature aggregation strategy based on global average pooling and concatenation, such a simplistic design may significantly limit the model’s ability to fully exploit the rich, complementary information present across different feature hierarchies. More advanced integration strategies, e.g., gating mechanisms or cross-attention, could provide more effective means of selectively emphasizing informative features and modeling their interactions. Additionally, the absence of dedicated projection heads may hinder the proper alignment of heterogeneous representations within a shared feature space, further constraining the model’s discriminative potential.

- Suboptimal MLP Hyperparameters for Diverse Datasets: While the feature extraction component does not require training, the effective training of the MLP relies on carefully selected hyperparameters. The current approach identifies optimal hyperparameters for the KTH-TIPS2-b dataset, which are then applied to the other three datasets. However, these parameters may not be ideal for all datasets. Further research could involve conducting separate hyperparameter optimization for each dataset using grid search or advanced optimization algorithms, potentially leading to improved performance across varied texture classes.

In summary, addressing these limitations through targeted research efforts could enhance the applicability and effectiveness of the proposed texture recognition method, ensuring its relevance in diverse practical scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented an effective architecture for texture recognition that aggregates multi-level representations extracted from pre-trained vision backbones. By combining features from early, mid, and late layers and feeding the resulting vector into a lightweight MLP classifier, the approach demonstrates the strong value of multi-level features, particularly from BEiTv2, for texture analysis and outperforms state-of-the-art approaches on four benchmark datasets: KTH-TIPS2-b, FMD, GTOS-Mobile, and Soil.

A key finding of this study is that final-layer features of ImageNet-22k-pretrained models are not sufficient for fine-grained texture discrimination. The ablation analysis shows that all evaluated backbones benefit from incorporating earlier hierarchical stages, which provide the fine local cues missing when relying solely on the final layer. The only exception is DeiT-3, where the baseline performs slightly better, although the overall evidence indicates that single-layer representations remain inadequate for robust texture analysis.

The work introduces several contributions, including a unified comparison of pre-trained backbones on five texture datasets, an efficient architecture that exploits multi-level representations without fine-tuning, and new empirical evidence on how hierarchical features contribute to texture discrimination. The approach also has limitations: its strongest configuration relies on computationally demanding transformers such as BEiTv2, the feature aggregation mechanism is intentionally simple, and the MLP hyperparameters tuned on KTH-TIPS2-b may not generalize optimally. Qualitative analysis further indicates a persistent bias of ImageNet-22k-pretrained models toward global shape or object-level cues.

These observations suggest several directions for future work. Efficient or compressed variants of the architecture could broaden its applicability in resource-limited settings. Advanced integration mechanisms, such as cross-attention, learned projection heads, or gated feature fusion, may improve alignment and interaction across layers, and an analysis of state-of-the-art intelligent fusion methods could further guide the development of effective feature aggregation strategies. Fine-tuning or pre-training on larger texture-oriented datasets could reduce the observed shape bias and enhance discrimination for challenging texture classes. Finally, incorporating process-aware datasets or controlled subsets with explicit intra-class variation would support more comprehensive robustness evaluations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and K.T.; methodology, N.N. and K.T.; software, N.N., K.T. and I.B.; validation, R.P., I.B. and N.N.; formal analysis, N.N., K.T. and I.B.; investigation, A.M., K.T., R.P. and N.N.; resources, N.N.; data curation, N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., K.T. and N.N.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and K.T.; visualization, N.N., I.B. and R.P.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is financed by the European Union-Next Generation EU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0005: “Improving the research capacity and quality to achieve international recognition and resilience of TU-Sofia” (IDEAS).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADAM | Adaptive Moment Estimation |

| BoVW | Bag-of-Visual-Words |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DEPNet | Deep Encoding Pooling Network |

| DeepTEN | Deep Texture Encoding Network |

| DTPNet | Deep Tracing Pattern encoding Network |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| GFB | Gabor Filter Banks |

| GLCM | Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| GMACs | Giga Multiply-Accumulate Operations |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LN | Layer Normalization |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LBP | Local Binary Patterns |

| LSCNet | Locality-Sensitive Coding Network |

| MBConv | Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution |

| MHSA | Multi-Head Self-Attention |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MPAP | Multiple Primitives and Attributes Perception |

| RADAM | Random Encoding of Aggregated Deep Activation Maps |

| RAE | Randomized Autoencoder |

| RPNet | Residual Pooling Network |

| RIFT | Rotation Invariant Feature Transform |

| SIFT | Scale Invariant Feature Transform |

| SW-MSA | Shifted Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention |

| SW-SCA | Shifted Windowed Scaled Cosine Attention |

| SSM | State-Space Model |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VLAD | Vector of Locally Aggregated Descriptors |

| ViTs | Vision Transformers |

| W-MSA | Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention |

| W-SCA | Windowed Scaled Cosine Attention |

References

- Agarwal, M.; Singhal, A.; Lall, B. 3D local ternary co-occurrence patterns for natural, texture, face and bio medical image retrieval. Neurocomputing 2018, 313, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiva, P.; Purri, M.; Leotta, M. Self-supervised material and texture representation learning for remote sensing tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8203–8215. [Google Scholar]

- Swetha, R.; Bende, P.; Singh, K.; Gorthi, S.; Biswas, A.; Li, B.; Weindorf, D.C.; Chakraborty, S. Predicting soil texture from smartphone-captured digital images and an application. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Fieguth, P.; Zhao, G.; Chellappa, R.; Pietikäinen, M. From BoW to CNN: Two decades of texture representation for texture classification. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2019, 127, 74–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Cao, Y.; Zha, Z.J.; Xie, H.; Wu, F. Deep structure-revealed network for texture recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11010–11019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zha, Z.J. Deep multiple-attribute-perceived network for real-world texture recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3613–3622. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, F.; Quan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ji, H. Deep texture recognition via exploiting cross-layer statistical self-similarity. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 5231–5240. [Google Scholar]

- Fujieda, S.; Takayama, K.; Hachisuka, T. Wavelet convolutional neural networks for texture classification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.07394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Jégou, H. Deit iii: Revenge of the vit. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 516–533. [Google Scholar]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I.H. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2007, SMC-3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazebnik, S.; Schmid, C.; Ponce, J. A sparse texture representation using local affine regions. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jégou, H.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C.; Pérez, P. Aggregating local descriptors into a compact image representation. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 3304–3311. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, D. Theory of communication. Part 1: The analysis of information. J. Inst. Electr. Eng. Part III Radio Commun. Eng. 1946, 93, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikainen, M.; Maenpaa, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Jia, Y. Deep convolutional network with locality and sparsity constraints for texture classification. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 91, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhang, H.; Dana, K. Deep texture manifold for ground terrain recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 558–567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, J.; Dana, K. Deep ten: Texture encoding network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 708–717. [Google Scholar]

- Peeples, J.; Xu, W.; Zare, A. Histogram layers for texture analysis. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Chen, Z.; Liang, J.; Quan, Y. Encoding spatial distribution of convolutional features for texture representation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021), Online, 14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 22732–22744. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, S.; Rajan, D.; Chia, L.T. Deep residual pooling network for texture recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 112, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Tao, D.; Zha, Z.J. On exploring multiplicity of primitives and attributes for texture recognition in the wild. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Quan, Y.; Xu, R.; Jin, L.; Xu, Y. Enhancing texture representation with deep tracing pattern encoding. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 146, 109959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scabini, L.; Zielinski, K.M.; Ribas, L.C.; Gonçalves, W.N.; De Baets, B.; Bruno, O.M. RADAM: Texture recognition through randomized aggregated encoding of deep activation maps. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, J.B. Fractal pooling: A new strategy for texture recognition using convolutional neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurício, J.; Domingues, I.; Bernardino, J. Comparing vision transformers and convolutional neural networks for image classification: A literature review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scabini, L.; Sacilotti, A.; Zielinski, K.M.; Ribas, L.C.; De Baets, B.; Bruno, O.M. A Comparative Survey of Vision Transformers for Feature Extraction in Texture Analysis. J. Imaging 2024, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; Shen, H.; Zhang, G.; Deng, X.; Xiong, J.; Feng, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, S. A multi-layer feature fusion model based on convolution and attention mechanisms for text classification. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; He, S.; Tang, J. Divide-and-conquer: Confluent triple-flow network for RGB-T salient object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 47, 1958–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ning, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, L.; et al. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12009–12019. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 459–479. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Wang, X. Mambaout: Do we really need mamba for vision? In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 4484–4496. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Dong, L.; Bao, H.; Ye, Q.; Wei, F. Beit v2: Masked image modeling with vector-quantized visual tokenizers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.06366. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, F.; Mathur, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Chaurasia, S. An advanced artificial intelligence framework integrating ensembled convolutional neural networks and Vision Transformers for precise soil classification with adaptive fuzzy logic-based crop recommendations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, B.; Hayman, E.; Mallikarjuna, P. Class-specific material categorisation. In Proceedings of the Tenth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05), Volume 1, Beijing, China, 17–20 October 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1597–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, L.; Rosenholtz, R.; Adelson, E. Material perception: What can you see in a brief glance? J. Vis. 2009, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yang, H.; Yin, Z. Multi-scale boosting feature encoding network for texture recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 4269–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpoi, M.; Maji, S.; Kokkinos, I.; Mohamed, S.; Vedaldi, A. Describing Textures in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 3606–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshov, N.; Tonchev, K.; Manolova, A. LBCNIN: Local Binary Convolution Network with Intra-Class Normalization for Texture Recognition with Applications in Tactile Internet. Electronics 2024, 13, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- pytorch.org, Instalation of Pytorch v1.12.1. Available online: https://pytorch.org/get-started/previous-versions/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Wightman, R. Pytorch Image Models (timm). Available online: https://github.com/rwightman/pytorch-image-models (accessed on 28 November 2025).